Prevalence and Intensity of Perkinsus sp. Infection in Mizuhopecten yessoensis and Its Impact on the Immune Status of Bivalves

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

2.2. Hemolymph Collection and Processing

2.3. Assessment of the Degree of Contamination of Mollusks

2.4. Evaluation of Immune Parameters of Hemolymph

2.5. Data Analysis

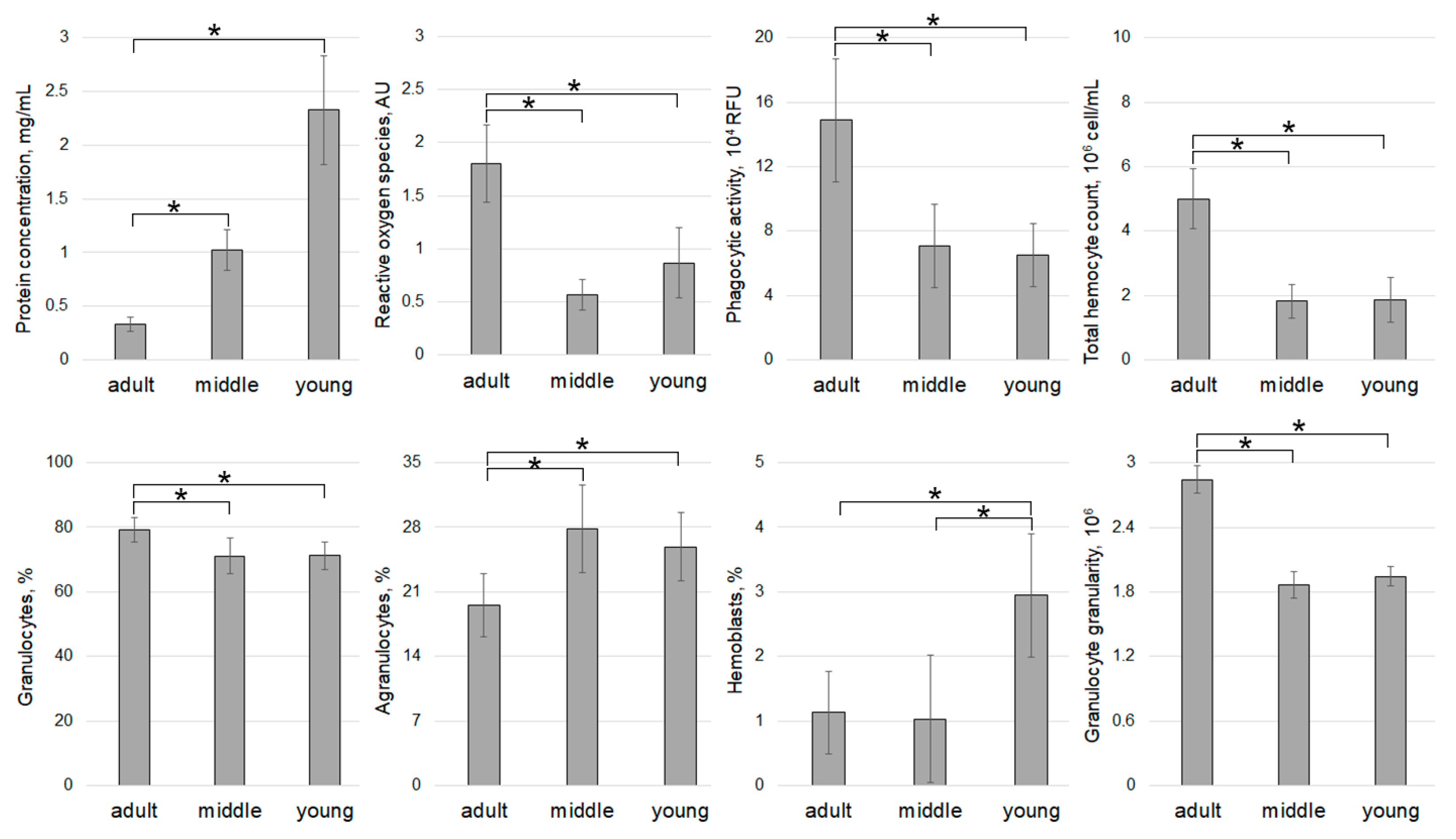

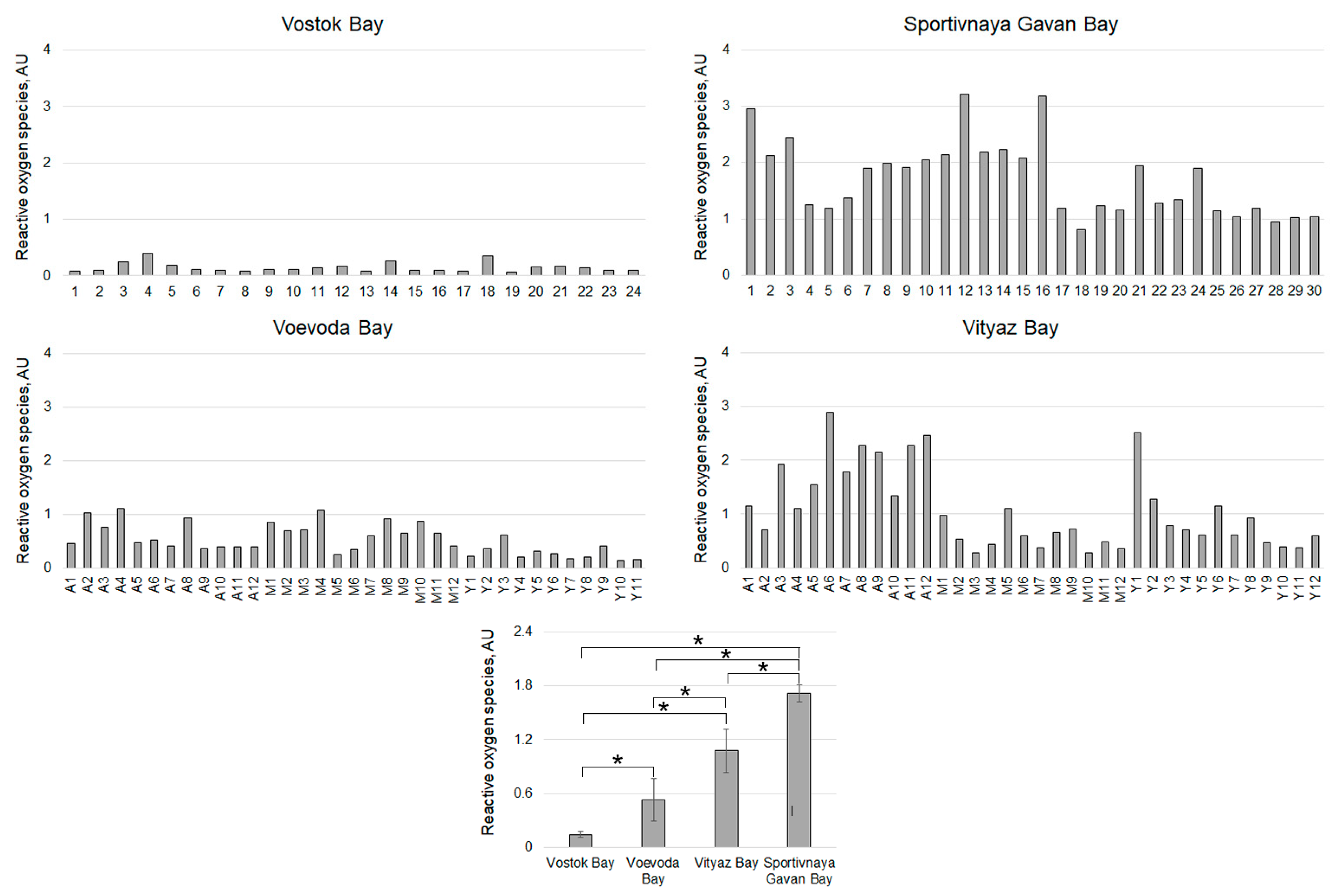

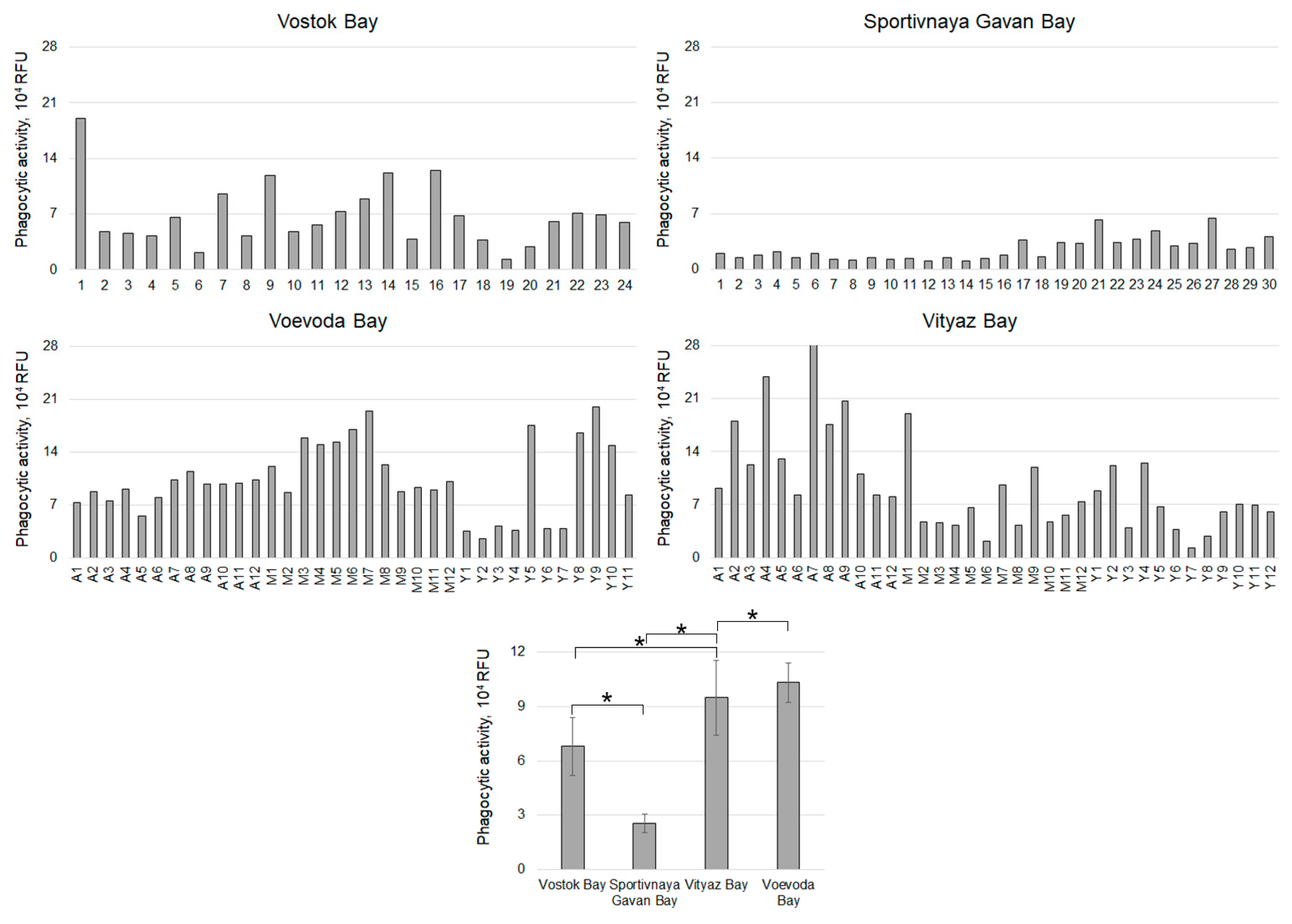

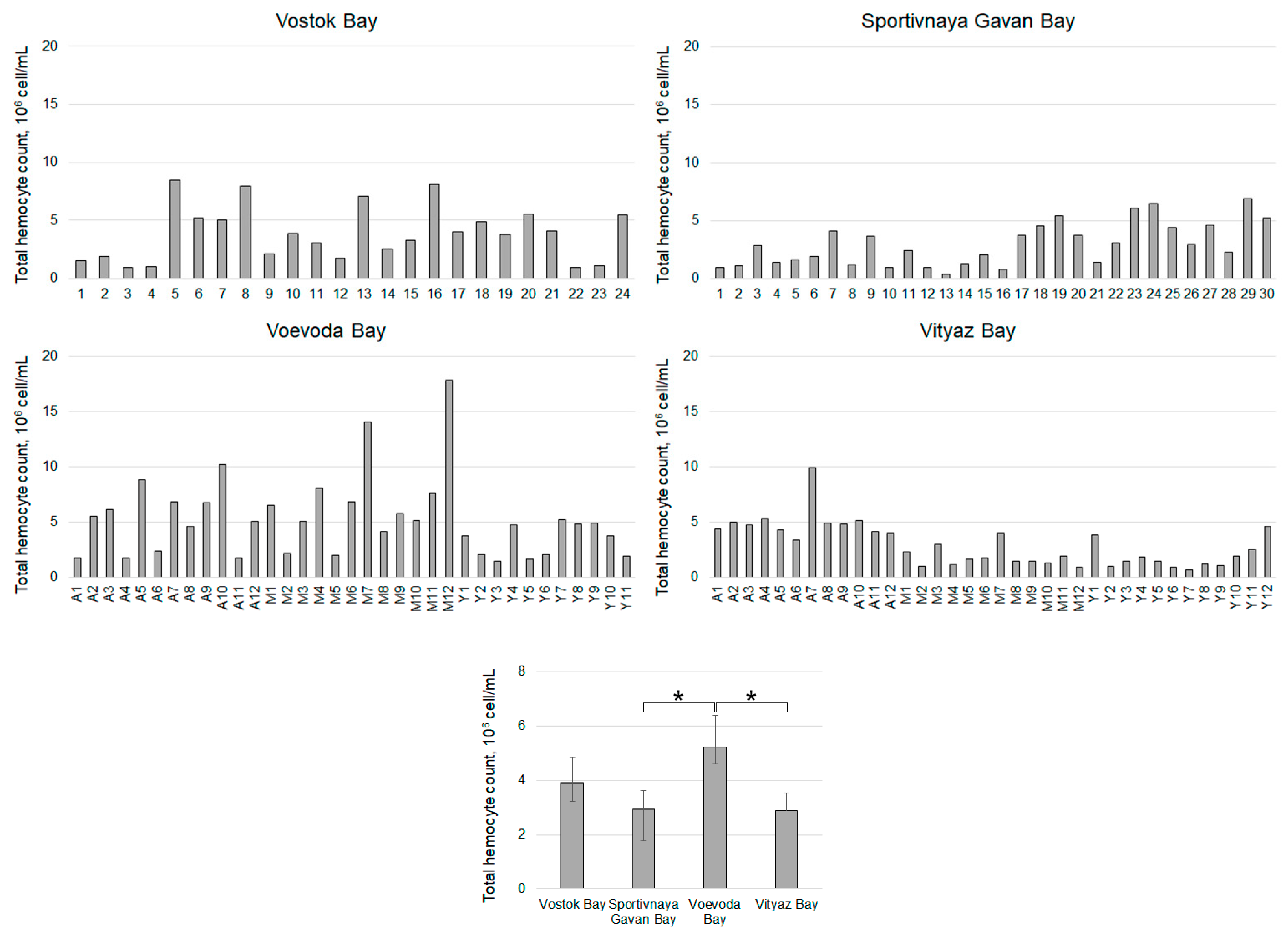

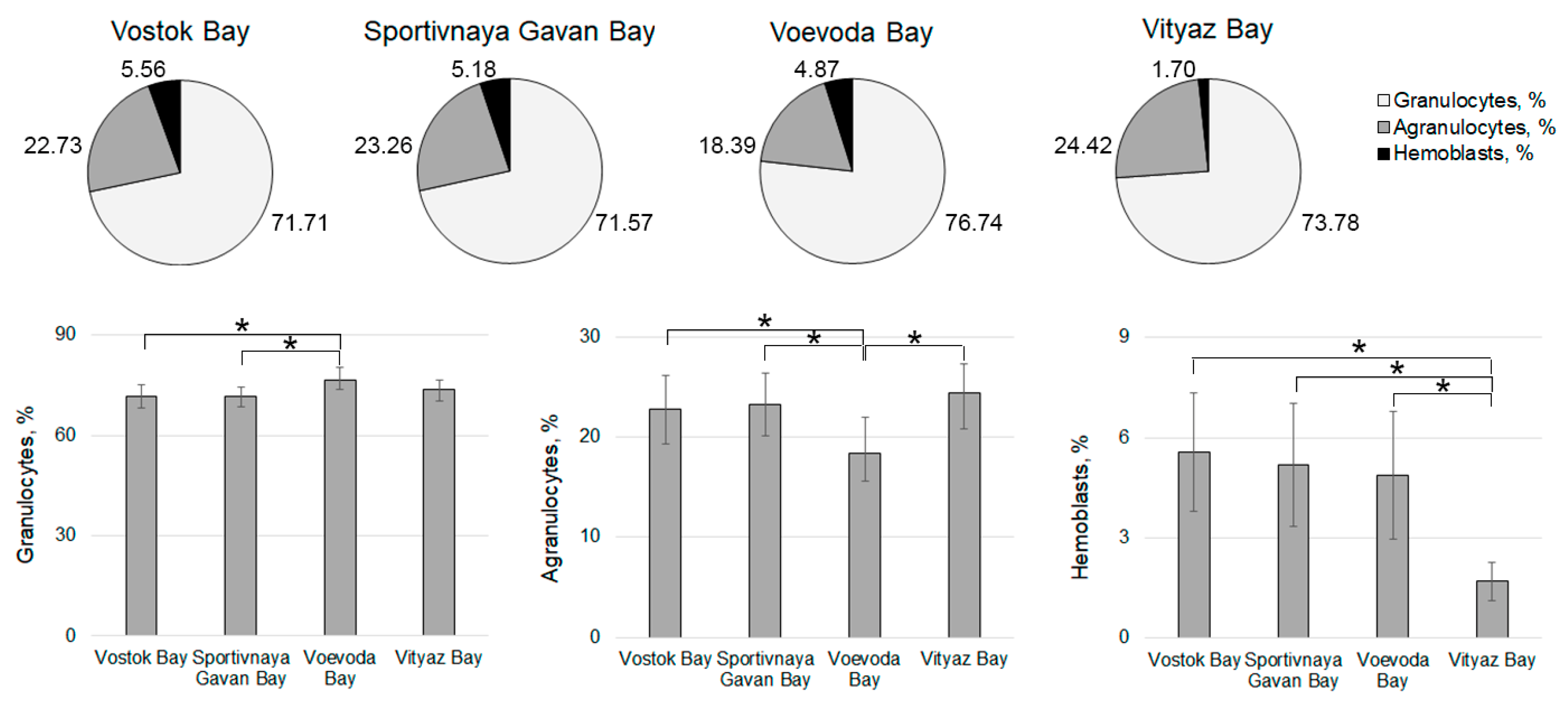

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abollo, E.; Casas, S.M.; Ceschia, G.; Villalba, A. Differential Diagnosis of Perkinsus Species by Polymerase Chain Reaction-Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism Assay. Mol. Cell. Probes 2006, 20, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umeda, K.; Yang, X.; Waki, T.; Yoshinaga, T.; Itoh, N. The Effects of Environmental and Nutritional Conditions on the Development of Perkinsus olseni Prezoosporangia. Exp. Parasitol. 2020, 209, 107827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Queiroga, F.R.; Marques-Santos, L.F.; Hégaret, H.; Soudant, P.; Farias, N.D.; Schlindwein, A.D.; Mirella da Silva, P. Immunological Responses of the Mangrove Oysters Crassostrea gasar Naturally Infected by Perkinsus Sp. in the Mamanguape Estuary, Paraíba State (Northeastern, Brazil). Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2013, 35, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalba, A.; Reece, K.S.; Camino Ordás, M.; Casas, S.M.; Figueras, A. Perkinsosis in Molluscs: A Review. Aquat. Living Resour. 2004, 17, 411–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Choi, M.; Park, K.; Park, S. Effects of Anoxia on Immune Functions in the Surf Clam Mactra veneriformis. Zool. Stud. 2010, 49, 94–101. [Google Scholar]

- Waki, T.; Lee, H.-J.; Park, S.-R.; Park, J.; Kwun, H.-J.; Choi, K.-S. First Report of the Microgastropod Ammonicera japonica (Omalogyridae Habe, 1972) in Korea. J. Asia-Pac. Biodivers. 2016, 9, 180–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández Robledo, J.A.; Caler, E.; Matsuzaki, M.; Keeling, P.J.; Shanmugam, D.; Roos, D.S.; Vasta, G.R. The Search for the Missing Link: A Relic Plastid in Perkinsus? Int. J. Parasitol. 2011, 41, 1217–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tasumi, S.; Vasta, G.R. A Galectin of Unique Domain Organization from Hemocytes of the Eastern Oyster (Crassostrea virginica) Is a Receptor for the Protistan Parasite Perkinsus marinus. J. Immunol. 2007, 179, 3086–3098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, K.S.; Wilson, E.A.; Lewis, D.H. The Energetic Cost of Perkinsus marinus Parasitism in Oyster: Quantification of the Thioglycollate Method. J. Shellfish. Res. 1989, 8, 125–136. [Google Scholar]

- Itoh, N.; Meyer, G.R.; Tabata, A.; Lowe, G.; Abbott, C.L.; Johnson, S.C. Rediscovery of the Yesso Scallop Pathogen Perkinsus qugwadi in Canada, and Development of PCR Tests. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 2013, 104, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavrilova, G.S.; Motora, Z.I.; Pozdnyakov, S.E. Results of Examination the State of Yesso Scallop (Mizuhopecten yessoensis) on Plantations of Aquaculture in Primorye. Izv. TINRO 2021, 201, 895–909. [Google Scholar]

- Lysenko, V.N.; Zharikov, V.; Lebedev, A.M.; Sokolenko, D. Distribution of the Yesso Scallop, Mizuhopecten yessoensis (Jay, 1857) (Bivalvia: Pectinidae) in the Southern Part of the Far Eastern Marine Reserve. Russ. J. Mar. Biol. 2017, 43, 302–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bower, S.M.; McGladdery, S.E. Synopsis of Infectious Diseases and Parasites of Commercially Exploited Shellfish. Annu. Rev. Fish. Dis. 1994, 4, 1–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butorina, T.E.; Degteva, E.D. Disease of the Primorye Scallop Mizuhopecten yessoensis (Jay, 1857) in the Primorye Mariculture Farms Caused by Protozoa of the Genus Perkinsus Levine, 1978. Russ. J. Mar. Biol. 2023, 49, 353–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brovkina, E.P.; Kostina, E.A. The Presence of Epidemiologically Significant Invasions in the Scallop When Grown on Farms Mariculture. Actual Probl. Dev. Biol. Resour. World Ocean. Mater. VI Int. Sci. Tech. Conf. Vladivostok 2020, 1, 9–13. [Google Scholar]

- Bovina, E.P.; Kostina, E.A. The Nature of the Couts of Epizooties during Cage Rearing of Scallops in Primorye. Perkinsus Is the Likely Cause of These Diseases. Sci. Work. FESTFU 2020, 53, 41–52. [Google Scholar]

- Dulenina, P.A.; Dulenin, A.A. The Distribution, Size and Age Compositions, and Growth of the Scallop Mizuhopecten yessoensis (Bivalvia: Pectinidae) in the Northwestern Tatar Strait. Russ. J. Mar. Biol. 2012, 38, 310–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khristoforova, N.K.; Naumov, Y.A.; Arzamastsev, I.S. Heavy Metals in Bottom Sediments of Vostok Bay (Japan Sea). Izv. TINRO 2004, 136, 278–289. [Google Scholar]

- Khristoforova, N.K.; Lazaryuk, A.Y.; Zhuravel, E.V.; Boychenko, T.V.; Emelyanov, A.A. Vostok Bay: Interseasonal Changes in Hydrological, Hydrochemical and Microbiological Properties. Izv. TINRO 2023, 203, 906–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khristoforova, N.K.; Boychenko, T.V.; Kobzar, A.D. Hydrochemical and Microbiological Assessment of the Current State of the Vostok Bay. Vestn. FEB RAS 2020, 210, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuravel, E.V.; Podgurskaya, O.V. Early Development of Sand Dollar Scaphechinus Mirabilis in the Water from Different Areas of Peter the Great Bay (Japan Sea). Izv. TINRO 2014, 178, 206–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vashchenko, M.A.; Zhadan, P.M.; Almyashova, T.N.; Kovalyova, A.L.; Slinko, E.N. Assessment of the Contamination Level of Bottom Sediments of Amursky Bay (Sea of Japan) and Their Potential Toxicity. Russ. J. Mar. Biol. 2010, 36, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigmatulina, L.V. Assessment of Anthropogenic Load of Coastal Sources on the Amursky Bay (Sea of Japan). Vestn. FEB RAS 2007, 1, 73–77. [Google Scholar]

- Chernyaev, A.P.; Nigmatulina, L.V. Quality Monitoring of Coastal Waters in Peter the Great Bay (Japan Sea). Izv. TINRO 2013, 173, 230–238. [Google Scholar]

- Khristoforova, N.K.; Kobzar, A.D. Assessment of Ecological State of the Posyet Bay (the Sea of Japan) by Heavy Metals Content in Brown Algae. Samara J. Sci. 2017, 6, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugaets, A.N.; Katrasov, S.V.; Zharikov, V.V. Probabilistic Assessment of Mariculture Potential Productivity from the Example of Voevoda Bay, South of Primorskii Krai. Dokl. Earth Sci. 2022, 503, 104–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barabanshchikov, Y.A.; Tishchenko, P.Y.; Semkin, P.Y.; Volkova, T.I.; Zvalinsky, V.I.; Mikhailik, T.A.; Sagalaev, S.G.; Sergeev, A.F.; Tishchenko, P.P.; Shvetsova, M.G.; et al. Seasonal Hydrological and Hydrochemical Surveys in the Voevoda Bay (Amur Bay, Japan Sea). Izv. TINRO 2015, 180, 161–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soudant, P.; Chu, F.L.E.; Volety, A. Host-Parasite Interactions: Marine Bivalve Molluscs and Protozoan Parasites, Perkinsus Species. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2013, 114, 196–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scardua, M.P.; Vianna, R.T.; Duarte, S.S.; Farias, N.D.; Correia, M.L.D.; Santos, H.T.A.D.; Silva, P.M.D. Growth, Mortality and Susceptibility of Oyster Crassostrea Spp. to Perkinsus Spp. Infection during on Growing in Northeast Brazil. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 2017, 26, 401–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villalba, A.; Casas, S.M.; López, C.; Boncler, M. Study of Perkinsosis in the Carpet Shell Clam Tapes decussatus in Galicia (NW Spain). II. Temporal Pattern of Disease Dynamics and Association with Clam Mortality. Dis. Aquat. Org. 2005, 65, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.-I.; Choi, K.-S. Spatial Distribution of the Protozoan Parasite Perkinsus Sp. Found in the Manila Clams, Ruditapes philippinarum, in Korea. Aquaculture 2001, 203, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.-S.; Park, K.-I. Report on Occurrence of Perkinsus Sp. in the Manila Clam, Ruditapes philippinarum, in Korea. Korean J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 1997, 10, 227–237. [Google Scholar]

- Hamaguchi, M.; Suzuki, N.; Usuki, H.; Ishioka, H. Perkinsus Protozoan Infection in Short-Necked Clam Tapes (Ruditapes) Philippinarum. Fish. Sci. 1998, 64, 864–868. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, C.C.; Bacha, L.; Paz, P.; Oliveira, M. Collapse of Scallop Nodipecten Nodosus Production in the Tropical Southeast Brazil as a Possible Consequence of Global Warming and Water Pollution. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 904, 166873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Getchell, R.; Smolowitz, R.; McGladdery, S.E.; Bower, S.M. Diseases and Parasites of Scallops. Dev. Aquacult. Fish. Sci. 2016, 40, 425–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bower, S.M.; Blackbourn, J.; Meyer, G.R.; Nishimura, D.J.H. Diseases of Cultured Scallops (Patinopecten yessoensis) in British Columbia, Canada. Aquaculture 1992, 107, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bower, S.M.; Blackbourn, J.; Meyer, G.R. Distribution, Prevalence, and Pathogenicity of the Protozoan Perkinsus qugwadi in Japanese Scallops, Patinopecten yessoensis, Cultured in British Columbia, Canada. Can. J. Zool. 1998, 76, 954–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bower, S.M.; Blackbourn, J.; Meyer, G.R.; Welch, D.W. Effect of Perkinsus qugwadi on Various Species and Strains of Scallops. Dis. Aquat. Org. 1999, 36, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajamange, D.; Kim, S.-H.; Choi, K.-S.; Azevedo, C.; Park, K.-I. Scanning Electron Microscopic Observation of the in Vitro Cultured Protozoan, Perkinsus olseni, Isolated from the Manila Clam, Ruditapes philippinarum. BMC Microbiol. 2020, 20, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casas, S.M.; La Peyre, J.F.; Reece, K.S.; Azevedo, C.; Villalba, A. Continuous in Vitro Culture of the Carpet Shell Clam Tapes Decussatus Protozoan Parasite Perkinsus atlanticus. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 2002, 52, 217–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunila, I.; Hamilton, R.M.; Duncan, C.F. Ultrastructural Characteristics of the In Vitro Cell Cycle of the Protozoan Pathogen of Oysters, Perkinsus marinus. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 2001, 48, 348–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burreson, E.M.; Reece, K.S.; Dungan, C.F. Molecular, Morphological, and Experimental Evidence Support the Synonymy of Perkinsus chesapeaki and Perkinsus andrewsi. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 2005, 52, 258–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, J.A.; Xiao, J.; Dungan, C.F.; Reece, K.S. Description of Perkinsus Beihaiensis n. Sp., a New Perkinsus Sp. Parasite in Oysters of Southern China. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 2008, 55, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Yang, X.; Zhai, J.; Qi, P.; Ren, Z.; Zhu, D.; Fu, P. Survey on Perkinsus Species in Two Economic Mussels (Mytilus coruscus and M. galloprovincialis) along the Coast of the East China Sea and the Yellow Sea. Parasitol. Res. 2024, 123, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhai, J.; Qi, P.; Yang, X.; Ren, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Gao, J.; Zhu, D.; Fu, P. First Record of Perkinsus beihaiensis in Cultured Mussels Mytilus coruscus in the East China Sea. Parasitology 2024, 151, 1104–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Góngora-Gómez, A.M.; Villanueva-Fonseca, L.C.; Sotelo-Gonzalez, M.I.; Sepúlveda, C.H.; Hernández-Sepúlveda, J.A.; García-Ulloa, M. Detecting Perkinsus-like Organisms and Perkinsus marinus (Myzozoa: Perkinsidae) within New Bivalve Hosts in the Southeastern Gulf of California. Parasitol. Res. 2024, 123, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butorina, T.E.; Tvorogova, E.V. Infection of Mollusks with Dinoflagellates of the Genus Perkinsus: Etiology, Symptoms, Distribution, Diagnosis. Actual Probl. Dev. Biol. Resour. World Ocean. Mater. IV Int. Sci. Tech. Conf. Vladivostok 2016, 1, 49–53. [Google Scholar]

- Dvoretsky, A.G.; Dvoretsky, V.G. Biological Aspects, Fisheries, and Aquaculture of Yesso Scallops in Russian Waters of the Sea of Japan. Diversity 2022, 14, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, F.L.E.; Peyre, J.F.L. Effect of Environmental Factors and Parasitism on Hemolymph Lysozyme and Protein of American Oysters (Crassostrea virginica). J. Invertebr. Pathol. 1989, 54, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umeda, K.; Shimokawa, J.; Yoshinaga, T. Effects of Temperature and Salinity on the in Vitro Proliferation of Trophozoites and the Development of Zoosporangia in Perkinsus olseni and P. honshuensis, Both Infecting Manila Clam. Fish. Pathol. 2013, 48, 13–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolowitz, R. A Review of Current State of Knowledge Concerning Perkinsus marinus Effects on Crassostrea virginica (Gmelin) (the Eastern Oyster). Vet. Pathol. 2013, 50, 404–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goggin, C.L.; Lester, R.J.G. Perkinsus, a Protistan Parasite of Abalone in Australia: A Review. Mar. Freshw. Res. 1995, 46, 639–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casas, S.M.; Grau, A.; Reece, K.S.; Apakupakul, K.; Azevedo, C.; Villalba, A. Perkinsus mediterraneus n. Sp., a Protistan Parasite of the European Flat Oyster Ostrea edulis from the Balearic Islands, Mediterranean Sea. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 2004, 58, 231–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dungan, C.F.; Hamilton, R.M.; Hudson, K.L.; McCollough, C.B.; Reece, K.S. Two Epizootic Diseases in Chesapeake Bay Commercial Clams, Mya arenaria and Tagelus plebeius. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 2002, 50, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zheng, Y.-D.; Yuan, T.; Liu, C.-F.; Huang, B.W.; Xin, L.-S.; Wang, C.; Bai, C.-M. Occurrence and Seasonal Variation of Perkinsus Sp. Infection in Wild Mollusk Populations from Coastal Waters of Qingdao, Northern China. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2024, 202, 108044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casas, S.M.; Villalba, A.; Reece, K.S. Study of Perkinsosis in the Carpet Shell Clam Tapes Decussatus in Galicia (NW Spain). I. Identification of the Aetiological Agent and in Vitro Modulation of Zoosporulation by Temperature and Salinity. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 2002, 50, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, E.P.; Winnicki, S.; Allam, B. Early Host—Pathogen Interactions in a Marine Bivalve: Crassostrea virginica Pallial Mucus Modulates Perkinsus marinus Growth and Virulence. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 2014, 104, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, Y.T.; Gambino, L.; Santos, B.; Pales Espinosa, E.; Allam, B. Transepithelial Migration of Mucosal Hemocytes in Crassostrea virginica and Potential Role in Perkinsus marinus Pathogenesis. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2018, 153, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zannella, C.; Mosca, F.; Mariani, F.; Franci, G.; Folliero, V.; Galdiero, M.; Tiscar, P.G.; Galdiero, M. Microbial Diseases of Bivalve Mollusks: Infections, Immunology and Antimicrobial Defense. Mar. Drugs 2017, 15, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cáceres-Martínez, J.; Vásquez-Yeomans, R.; Padilla-Lardizábal, G.; Del Río Portilla, M.A. Perkinsus marinus in Pleasure Oyster Crassostrea corteziensis from the Pacific Coast of Mexico. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2008, 99, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carnegie, R.B.; Burreson, E.M. Perkinsus Marinus and Haplosporidium Nelsoni. In Fish Parasites: Pathobiology and Protection; Woo, P.T.K., Buchmann, K., Eds.; CAB International: London, UK, 2012; pp. 92–108. [Google Scholar]

- Luz Cunha, A.C.; Pontinha, V.D.A.; de Castro, M.A.M.; Sühnel, S.; Medeiros, S.C.; Moura da Luz, Â.M.; Harakava, R.; Tachibana, L.; Mello, D.F.; Danielli, N.M.; et al. Two Epizootic Perkinsus Spp. Events in Commercial Oyster Farms at Santa Catarina, Brazil. J. Fish Dis. 2019, 42, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackin, J.G. Histopathology of Infection of Crassostrea virginica (Gmelin) by Dermocystidium marinum Mackin, Owen, and Collier. Bull. Mar. Sci. 1951, 1, 72–87. [Google Scholar]

- Song, L.; Wang, L.; Zhang, H.; Wang, M. The Immune System and Its Modulation Mechanism in Scallop. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2015, 46, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolnikova, Y.; Mokrina, M.; Magarlamov, T.; Grinchenko, A.; Kumeiko, V. Specification of Hemocyte Subpopulations Based on Immune-Related Activities and the Production of the Agglutinin MkC1qDC in the Bivalve Modiolus kurilensis. Heliyon 2023, 9, e15577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreyeva, A.Y.; Kladchenko, E.S.; Gostyukhina, O.L. Effect of Hypoxia on Immune System of Bivalve Molluscs. MBJ 2022, 7, 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Andreyeva, A.Y.; Efremova, E.S.; Kukhareva, T.A. Morphological and Functional Characterization of Hemocytes in Cultivated Mussel (Mytilus galloprovincialis) and Effect of Hypoxia on Hemocyte Parameters. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2019, 89, 361–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripp, M.R. Phagocytosis by Hemocytes of the Hard Clam, Mercenaria mercenaria. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 1992, 59, 222–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, F.L.E.; Lapeyre, J.F.; Burreson, C.S. Perkinsus marinus Infection and Potential Defense-Related Activities in Eastern Oysters Crassostrea virginica. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 1993, 62, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochennec-Laureau, N.; Auffret, M.; Renault, T.; Langlade, A. Changes in Circulating and Tissue-Infiltrating Hemocyte Parameters of European Flat Oysters, Ostrea Edulis, Naturally Infected with Bonamia ostreae. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2003, 81, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dang, C.; Lambert, C.; Soudant, P.; Delamare-Deboutteville, J.; Zhang, M.M.; Chan, J.; Green, T.J.; Goïc, N.L.; Barnes, A.C. Immune Parameters of QX-Resistant and Wild Caught Saccostrea Glomerata Hemocytes in Relation to Marteilia sydneyi Infection. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2011, 31, 1034–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Peyre, J.F.; Chu, F.L.E.; Meyers, J.M. Haemocytic and Humoral Activities of Eastern and Pacific Oysters Following Challenge by the Protozoan Perkinsus marinus. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 1995, 5, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordás, M.C.; Ordás, A.; Beloso, C.; Figueras, A. Immune Parameters in Carpet Shell Clams Naturally Infected with Perkinsus atlanticus. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2000, 10, 597–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R.S.; Paynter, K.T.; Burreson, E.M. Increased Reactive Oxygen Intermediate Production by Hemocytes Withdrawn from Crassostrea virginica Infected with Perkinsus marinus. Biol. Bull. 1992, 183, 476–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R.S. Interactions of Perkinsus marinus with Humoral Factors and Hemocytes of Crassostrea virginica. J. Shellfish Res. 1996, 15, 127–134. [Google Scholar]

- Garreis, K.A.; Peyre, J.F.L.; Faisal, M. The Effects of Perkinsus marinus Extracellular Products and Purified Proteases on Oyster Defence Parameters in Vitro. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 1996, 6, 581–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, C.; Carballal, M.J.; Azevedo, C.; Villalba, A. Differential Phagocytic Ability of the Circulating Haemocyte Types of the Carpet Shell Clam Ruditapes decussatus (Mollusca: Bivalvia). Dis. Aquat. Org. 1997, 3, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, S.E.; Oliver, L.M.; Fisher, W.S. Perkinsus marinus Tissue Distribution and Seasonal Variation in Infection Intensity in Eastern Oysters Crassostrea virginica. Dis. Aquat. Org. 1998, 34, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Kim, H.J.; Bathige, S.D.N.K.; Kim, S.; Park, K.I. Strain-Specific Virulence of Perkinsus marinus and Related Species in Eastern Oysters: A Comprehensive Analysis of Immune Responses and Mortality. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2025, 157, 110112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witkop, E.M.; Wikfors, G.H.; Proestou, D.A.; Lundgren, K.M.; Sullivan, M.; Gomez-Chiarri, M. Perkinsus marinus Suppresses in Vitro Eastern Oyster Apoptosis via IAP-Dependent and Caspase-Independent Pathways Involving TNFR, NF-kB, and Oxidative Pathway Crosstalk. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2022, 129, 104339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, F.M.; Foster, B.; Grewal, S.; Sokolova, I.M. Apoptosis as a Host Defense Mechanism in Crassostrea virginica and Its Modulation by Perkinsus marinus. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2010, 29, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gestal, C.; Roch, P.; Renault, T.; Pallavicini, A.; Paillard, C.; Novoa, B.; Oubella, R.; Venier, P.; Figueras, A. Study of Diseases and the Immune System of Bivalves Using Molecular Biology and Genomics. Rev. Fish. Sci. 2008, 16, 131–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olafsen, J.A.; Fletcher, T.C.; Grant, P.T. Agglutinin Activity in Pacific Oyster (Crassostrea gigas) Hemolymph Following in Vivo Vibrio anguillarum Challenge. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 1992, 16, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leite, R.B.; Milan, M.; Coppe, A.; Bortoluzzi, S.; Dos Anjos, A.; Reinhardt, R.; Saavedra, C.; Patarnello, T.; Cancela, M.; Bargelloni, L. MRNA-Seq and Microarray Development for the Grooved Carpet Shell Clam, Ruditapes decussatus: A Functional Approach to Unravel Host-Parasite Interaction. BMC Genom. 2013, 14, 741–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sampling Stations (Time, Temperature, Salinity) | Age of Individuals | Number of Individuals | Contamination (Hypnospores/mL)/Percentage of Infected | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hemolymph | Mantle | Gills | Digestive Gland | Shell | |||

| Vostok Bay (05/2024, 8 °C, 28‰) | all | 24 | 926 ± 579/26% | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Sportivnaya Gavan Bay (05/2024, 8 °C, 32‰) | all | 30 | 3667 ± 1470/47% | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Vityaz Bay (02/2025, 0 °C, 34‰) | all | 60 | 4963 ± 2201/43% | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Vityaz Bay (05/2024, 9 °C, 34‰) | all | 36 | 9630 ± 6034/69% | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| adults | 12 | 10,741 ± 10,712/67% | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | |

| middle-aged | 12 | 2963 ± 1643/58% | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | |

| young | 12 | 15,185 ± 14,536/83% | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | |

| Voevoda Bay (05/2024, 9 °C, 33‰) | all | 35 | 882,349 ± 189,697/89% | 1157 ± 470/80% | 4367 ± 1223/89% | 334 ± 221/40% | 1825 ± 536/91% |

| adults | 12 | 1,017,963 ± 329,092/100% | 604 ± 355/67% | 3691 ± 1956/92% | 25 ± 41/8% | 2457 ± 1331/83% | |

| middle-aged | 12 | 763,889 ± 358,247/83% | 767 ± 322/83% | 4735 ± 2383/75% | 150 ± 96/50% | 2242 ± 578/100% | |

| young | 11 | 863,636 ± 309,287/82% | 2188 ± 1301/100% | 4714 ± 2138/100% | 873 ± 631/64% | 682 ± 235/94% | |

| Vostok Bay | Protein Concentration, mg/mL | Reactive Oxygen Species, AU | Phagocytic Activity, RFU | Total Hemocyte Count, Cells/mL | Granulocytes, % | Agranulocytes, % | Hemoblasts, % | Granulocyte Granularity | Agranulocyte Granularity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Hemocyte Count, cells/mL | 0.50 | −0.23 | −0.10 | ||||||

| Agranulocytes, % | −0.08 | −0.29 | 0.19 | −0.14 | −0.83 | ||||

| Hemoblasts, % | −0.12 | 0.10 | −0.15 | 0.01 | −0.53 | 0.02 | |||

| Granulocyte granularity | 0.25 | −0.28 | 0.30 | 0.06 | 0.13 | 0.00 | −0.31 | ||

| Agranulocyte granularity | 0.05 | −0.26 | 0.25 | −0.14 | 0.11 | −0.01 | −0.20 | 0.55 | |

| Hypnospores, number/mL | −0.08 | −0.16 | −0.15 | 0.00 | 0.11 | −0.21 | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.23 |

| Sportivnaya Gavan Bay | Protein Concentration, mg/mL | Reactive Oxygen Species, AU | Phagocytic Activity, RFU | Total Hemocyte Count, Cells/mL | Granulocytes, % | Agranulocytes, % | Hemoblasts, % | Granulocyte Granularity | Agranulocyte Granularity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phagocytic activity, RFU | −0.30 | −0.54 | |||||||

| Total Hemocyte Count, cells/mL | −0.03 | −0.68 | 0.62 | ||||||

| Granulocytes, % | −0.20 | −0.20 | 0.14 | 0.29 | |||||

| Agranulocytes, % | 0.22 | 0.31 | −0.21 | −0.31 | −0.87 | ||||

| Hypnospores, number/mL | −0.07 | −0.12 | 0.07 | −0.07 | 0.03 | −0.06 | 0.01 | −0.03 | 0.08 |

| Voevoda Bay | Protein Concentration, mg/mL | Reactive Oxygen Species, AU | Phagocytic Activity, RFU | Total Hemocyte Count, Cells/mL | Granulocytes, % | Agranulocytes, % | Hemoblasts, % | Granulocyte Granularity | Agranulocyte Granularity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reactive Oxygen Species, AU | −0.38 | ||||||||

| Phagocytic activity, RFU | −0.31 | 0.11 | |||||||

| Total Hemocyte Count, cells/mL | −0.13 | 0.21 | 0.23 | ||||||

| Granulocytes, % | −0.14 | 0.40 | −0.09 | −0.08 | |||||

| Agranulocytes, % | 0.11 | −0.38 | 0.19 | 0.13 | −0.94 | ||||

| Hemoblasts, % | 0.19 | −0.41 | −0.15 | −0.08 | −0.81 | 0.59 | |||

| Granulocyte granularity | 0.05 | 0.38 | 0.21 | −0.02 | 0.09 | −0.02 | −0.22 | ||

| Agranulocyte granularity | −0.20 | 0.41 | 0.11 | 0.17 | 0.25 | −0.17 | −0.32 | 0.50 | |

| Hypnospores, number/mL | 0.33 | 0.03 | 0.11 | 0.02 | −0.15 | 0.20 | 0.10 | 0.09 | −0.14 |

| Vityaz Bay | Protein Concentration, mg/mL | Reactive Oxygen Species, AU | Phagocytic Activity, RFU | Total Hemocyte Count, Cells/mL | Granulocytes, % | Agranulocytes, % | Hemoblasts, % | Granulocyte Granularity | Agranulocyte Granularity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reactive Oxygen Species, AU | −0.51 | ||||||||

| Phagocytic activity, RFU | −0.58 | 0.49 | |||||||

| Total Hemocyte Count, cells/mL | −0.79 | 0.46 | 0.70 | ||||||

| Granulocytes, % | −0.44 | 0.35 | 0.30 | 0.61 | |||||

| Agranulocytes, % | 0.42 | −0.37 | −0.31 | −0.62 | −0.98 | ||||

| Hemoblasts, % | 0.34 | −0.08 | −0.11 | −0.21 | −0.58 | 0.46 | |||

| Granulocyte granularity | −0.60 | 0.62 | 0.48 | 0.61 | 0.54 | −0.54 | −0.15 | ||

| Agranulocyte granularity | −0.58 | 0.30 | 0.39 | 0.68 | 0.62 | −0.61 | −0.27 | 0.57 | |

| Hypnospores, number/mL | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.13 | −0.06 | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.00 | −0.12 | −0.20 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tsoy, E.; Tumas, A.; Mokrina, M.; Grinchenko, A.; Kumeiko, V.; Lanskikh, D.; Sokolnikova, Y. Prevalence and Intensity of Perkinsus sp. Infection in Mizuhopecten yessoensis and Its Impact on the Immune Status of Bivalves. Pathogens 2025, 14, 1303. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121303

Tsoy E, Tumas A, Mokrina M, Grinchenko A, Kumeiko V, Lanskikh D, Sokolnikova Y. Prevalence and Intensity of Perkinsus sp. Infection in Mizuhopecten yessoensis and Its Impact on the Immune Status of Bivalves. Pathogens. 2025; 14(12):1303. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121303

Chicago/Turabian StyleTsoy, Elizaveta, Ayna Tumas, Mariia Mokrina, Andrei Grinchenko, Vadim Kumeiko, Daria Lanskikh, and Yulia Sokolnikova. 2025. "Prevalence and Intensity of Perkinsus sp. Infection in Mizuhopecten yessoensis and Its Impact on the Immune Status of Bivalves" Pathogens 14, no. 12: 1303. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121303

APA StyleTsoy, E., Tumas, A., Mokrina, M., Grinchenko, A., Kumeiko, V., Lanskikh, D., & Sokolnikova, Y. (2025). Prevalence and Intensity of Perkinsus sp. Infection in Mizuhopecten yessoensis and Its Impact on the Immune Status of Bivalves. Pathogens, 14(12), 1303. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121303