Unveiling Equine Abortion Pathogens: A One Health Perspective on Prevalence and Resistance in Northwest China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

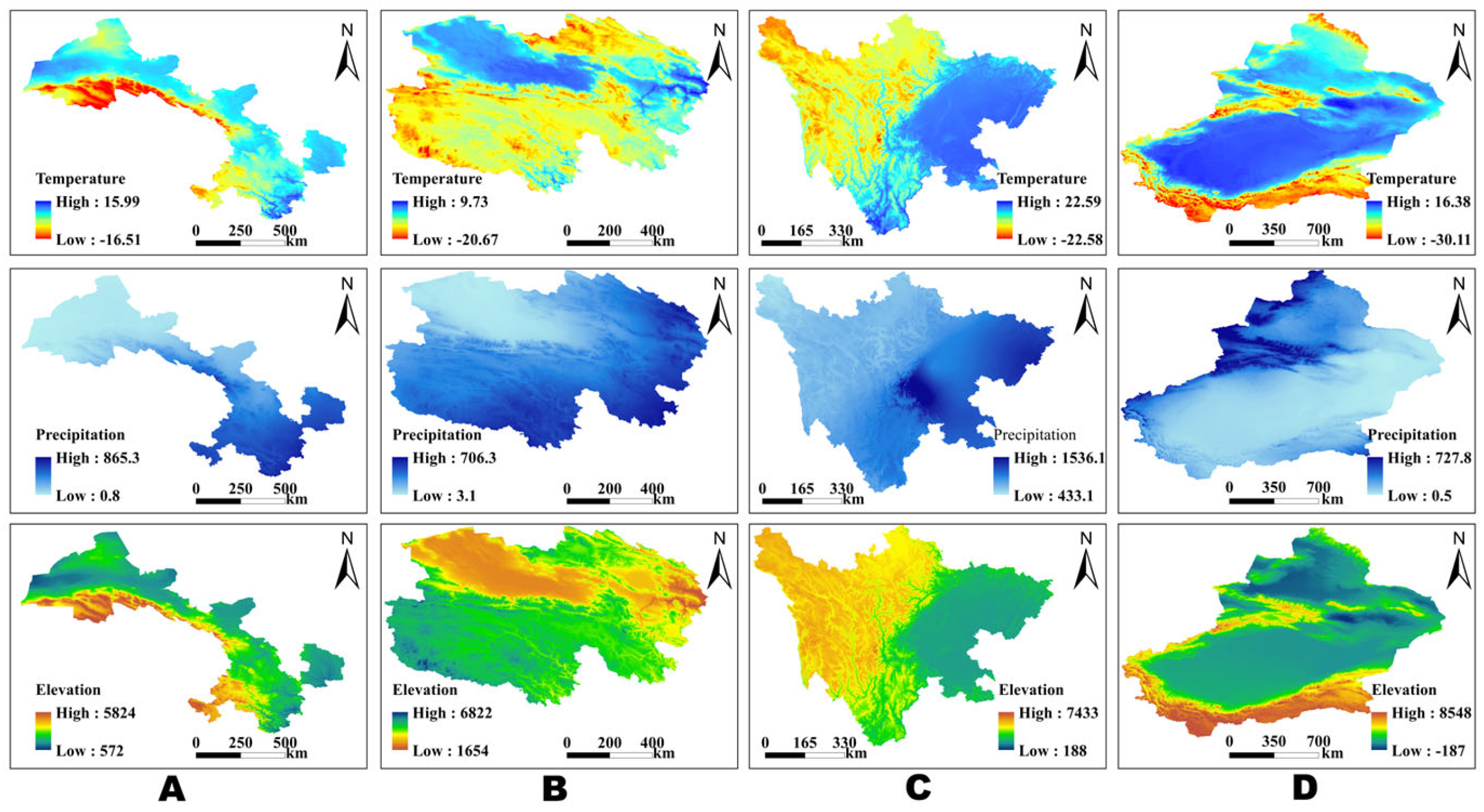

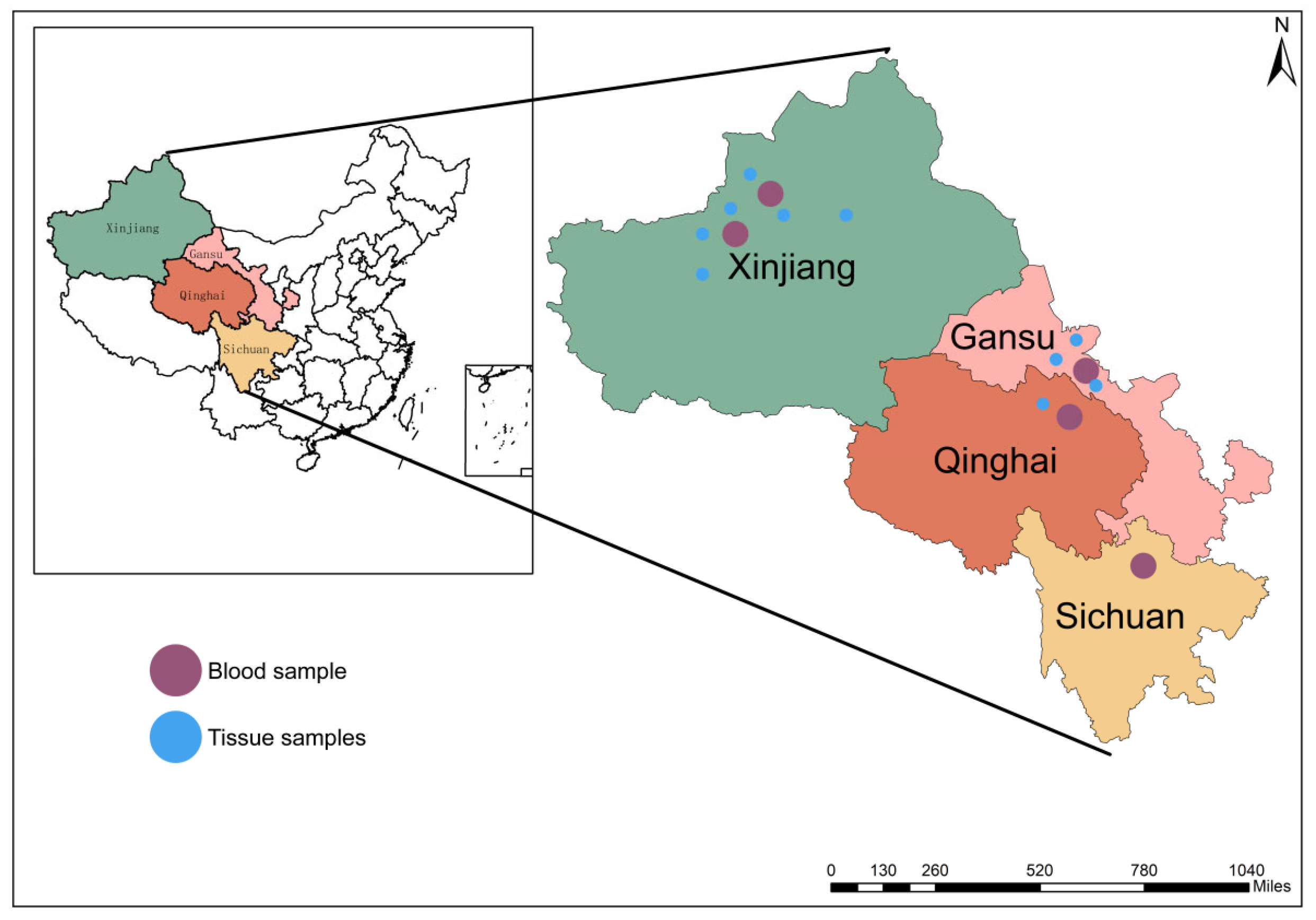

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Sample Size

2.3. Herd Selection and Sample Collection

2.4. Sampling

2.5. Serological Diagnosis

2.6. DNA Extraction and Real-Time PCR Detection

2.7. The Methods for Detecting Antibiotic Resistance Genes

2.8. Ethics

3. Results

3.1. The Detection Results of Chlamydia spp.

3.2. The Detection Results of C. burnetii

3.3. The Detection Results of Brucella spp.

3.4. The Detection Results of S. abortus equi

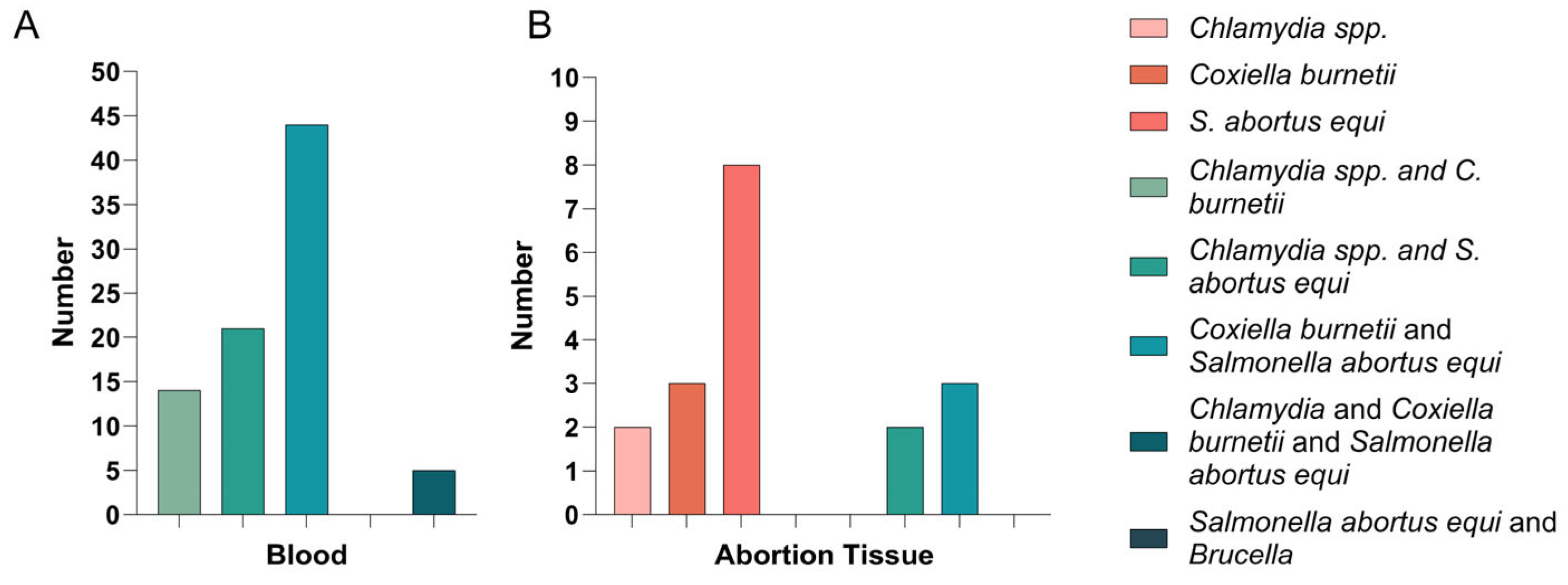

3.5. Detection Results of Abortion Tissue Samples and Mixed Infections

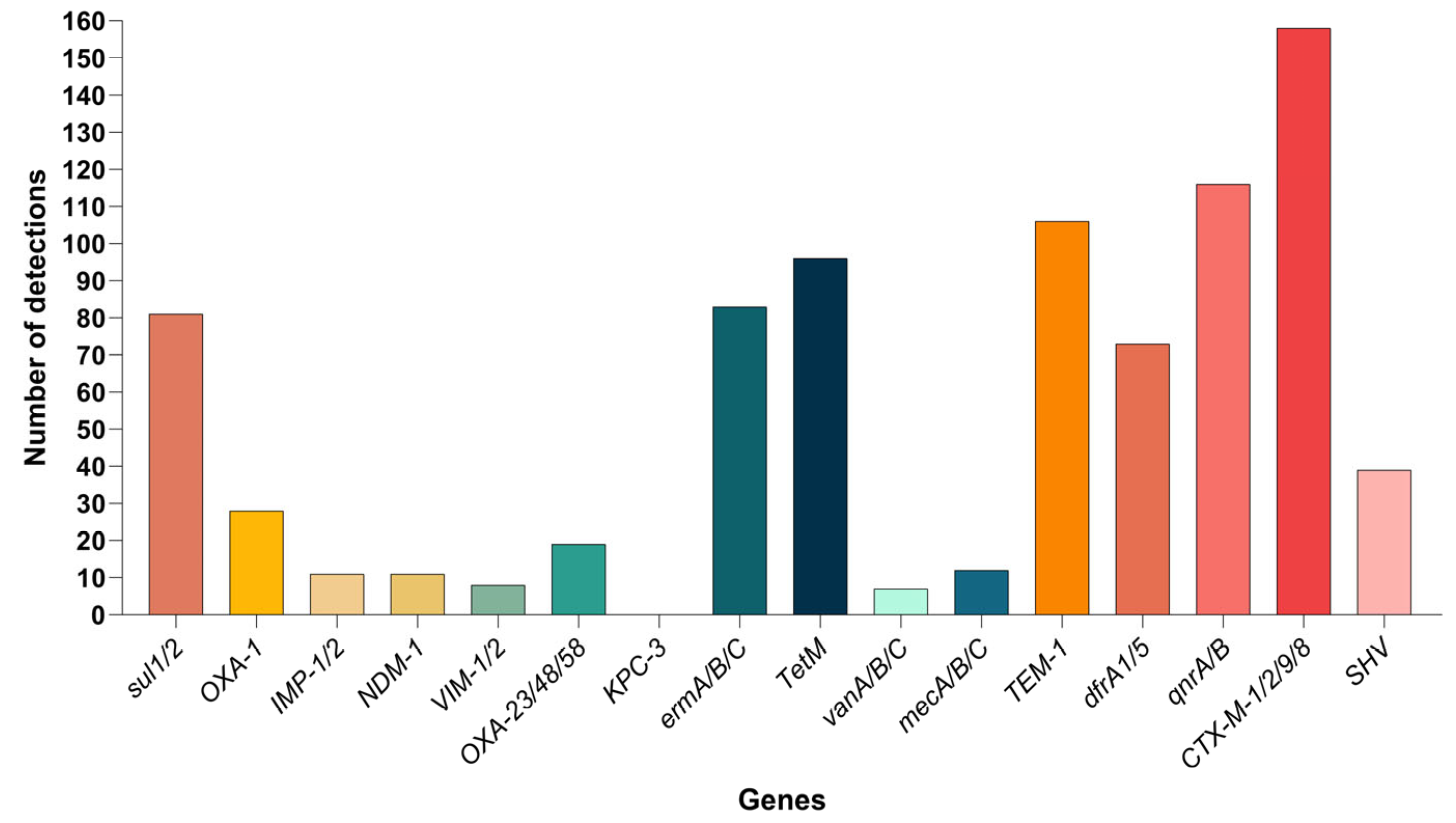

3.6. Detection of Antibiotic Resistance Genes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Location | Sex | Species | Age | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | Donkey | Horse | ≤5 | 5.1–10 Years | >10 Years | Blood | Aborted Tissue | |

| GanSu | 134 | 10 | 25 | 119 | 27 | 63 | 54 | 144 | 5 |

| QingHai | 108 | 8 | 6 | 110 | 11 | 66 | 39 | 116 | 1 |

| XinJiang | 180 | 20 | 10 | 190 | 22 | 138 | 40 | 200 | 18 |

| SiChuan | 48 | 0 | 5 | 43 | 3 | 26 | 19 | 48 | 0 |

| Primers | Sequence | |

|---|---|---|

| Chlamydia spp. | Chla-F | GCAACTGACACTAAGTCGGCTACA |

| Chla-R | ACAAGCATGTTCAATCGATAAGAGA | |

| Chla-P | FAM-TAAATACCAACGAATGGCAAGTTGGTTTAGCG-TAMRA | |

| C. burnetii | ISlllla-F | TGGGCTGCGTGGTGATG |

| ISlllla-R | TGACGTGCTGCGGACTGAT | |

| ISlllla-P | 5-FAM-CGTGTGGAGGAGCGAACCATTGGTAT-TAMRA | |

| S. abortus equi | Fljb-F | CATTAGGCAACCCGACAGTA |

| Fljb-R | GGTAGCACCGAATGATACAGC | |

| Fljb-P | 6-FAM-ACTGTAAGTGGTTATACCGATGC-MGB | |

| Brucella spp. | bcsp31-F | GCTCGGTTGCCAATATCAATGC |

| bcsp31-R | GGGTAAAGCGTCGCCAGAAG | |

| bcsp31-P | 6-FAM-AAATCTTCCACCTTGCCCTTGCCATCA-BHQ1 |

| Target Pathogen | Reaction Volume (μL) | Mix Components (per Reaction) | Thermal Program |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chlamydia spp. | 20 | Upstream primer 0.4 μL; Downstream primer 0.4 μL; Probe 0.2 μL; Enzyme 10 μL; DNA template 5 μL; ddH2O to 20 μL | Pre-denaturation: 95 °C, 5 min; PCR cycling (×45): 95 °C 10 s, 60 °C 30 s |

| C. burnetii | 20 | Upstream primer 0.4 μL; Downstream primer 0.4 μL; Probe 0.2 μL; Enzyme 10 μL; DNA template 5 μL; ddH2O to 20 μL | Pre-denaturation: 95 °C, 5 min; PCR cycling (×45): 95 °C 10 s, 60 °C 30 s |

| S. abortus equi | 20 | Upstream primer 0.4 μL; Downstream primer 0.4 μL; Probe 0.2 μL; Enzyme 10 μL; DNA template 5 μL; ddH2O to 20 μL | Pre-denaturation: 95 °C, 5 min; PCR cycling (×45): 95 °C 10 s, 60 °C 30 s |

| Brucella spp. | 20 | Upstream primer 0.4 μL; Downstream primer 0.4 μL; Probe 0.2 μL; Enzyme 10 μL; DNA template 5 μL; ddH2O to 20 μL | Pre-denaturation: 95 °C, 5 min; PCR cycling (×45): 95 °C 10 s, 60 °C 30 s |

| Antibiotic | Sulfonamides | Trimethoprim | Fluoroquinolones | ESBL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genes | sul1, sul2 | dfrA1, dfrA5 | qnrA, qnrB | SHV, CTX-M-1/2/9/8 |

| Antibiotic | Penicillin | Carbapenems | Macrolide/Lincosamide/Streptogramin | Tetracyclines |

| Genes | TEM-1, OXA-1 | IMP-1/2, NDM-1, VIM-1/2, OXA-23/48/58, KPC-3 | ermA/B/C | TetM |

| Antibiotic | Vancomycin | Methicillin/Penicillin | ||

| Genes | vanA/B/C | mecA/B/C |

References

- Sabine, M.; Feilen, C.; Herbert, L.; Jones, R.F.; Lomas, S.W.; Love, D.N.; Wild, J. Equine herpesvirus abortion in Australia 1977 to 1982. Equine Vet. J. 1983, 15, 366–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laval, K.; Poelaert, K.C.K.; Van Cleemput, J.; Zhao, J.; Vandekerckhove, A.P.; Gryspeerdt, A.C.; Garré, B.; van der Meulen, K.; Baghi, H.B.; Dubale, H.N.; et al. The Pathogenesis and Immune Evasive Mechanisms of Equine Herpesvirus Type 1. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 662686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, P.; Duan, R.; Palidan, N.; Deng, H.; Duan, L.; Ren, M.; Song, X.; Jia, C.; Tian, S.; Yang, E.; et al. Outbreak of neuropathogenic equid herpesvirus 1 causing abortions in Yili horses of Zhaosu, North Xinjiang, China. BMC Vet. Res. 2022, 18, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carossino, M.; Loynachan, A.T.; James MacLachlan, N.; Drew, C.; Shuck, K.M.; Timoney, P.J.; Del Piero, F.; Balasuriya, U.B. Detection of equine arteritis virus by two chromogenic RNA in situ hybridization assays (conventional and RNAscope®) and assessment of their performance in tissues from aborted equine fetuses. Arch. Virol. 2016, 161, 3125–3136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büscher, P.; Gonzatti, M.I.; Hébert, L.; Inoue, N.; Pascucci, I.; Schnaufer, A.; Suganuma, K.; Touratier, L.; Van Reet, N. Equine trypanosomosis: Enigmas and diagnostic challenges. Parasit. Vectors 2019, 12, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Guo, K.; Li, S.; Liu, D.; Chu, X.; Wang, Y.; Guo, W.; Du, C.; Wang, X.; Hu, Z. Development and Application of Real-Time PCR Assay for Detection of Salmonella Abortusequi. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2023, 61, e0137522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Hage, C.; Legione, A.; Devlin, J.; Hughes, K.; Jenkins, C.; Gilkerson, J. Equine Psittacosis and the Emergence of Chlamydia psittaci as an Equine Abortigenic Pathogen in Southeastern Australia: A Retrospective Data Analysis. Animals 2023, 13, 2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, R.; Stent, A.W.; Sansom, F.M.; Gilkerson, J.R.; Burden, C.; Devlin, J.M.; Legione, A.R.; El-Hage, C.M. Chlamydia psittaci: A suspected cause of reproductive loss in three Victorian horses. Aust. Vet. J. 2020, 98, 570–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, R.; Sansom, F.M.; El-Hage, C.M.; Gilkerson, J.R.; Legione, A.R.; Devlin, J.M. A 25-year retrospective study of Chlamydia psittaci in association with equine reproductive loss in Australia. J. Med. Microbiol. 2021, 70, 001284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricard, R.M.; Burton, J.; Chow-Lockerbie, B.; Wobeser, B. Detection of Chlamydia abortus in aborted chorioallantoises of horses from Western Canada. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 2023, 35, 359–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, M.G.; Lee, S.H.; Ouh, I.O.; Lee, G.H.; Goo, Y.K.; Kim, S.; Kwon, O.D.; Kwak, D. Molecular Detection and Genotyping of Coxiella-Like Endosymbionts in Ticks that Infest Horses in South Korea. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0165784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaferi, M.; Mozaffari, A.; Jajarmi, M.; Imani, M.; Khalili, M. Serologic and molecular survey of horses to Coxiella burnetii in East of Iran a highly endemic area. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2021, 76, 101647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, A.; Jamil, T.; Tareen, A.M.; Melzer, F.; Hussain, M.H.; Khan, I.; Saqib, M.; Zohaib, A.; Hussain, R.; Ahmad, W.; et al. Serological and Molecular Investigation of Brucellosis in Breeding Equids in Pakistani Punjab. Pathogens 2020, 9, 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tijjani, A.O.; Junaidu, A.U.; Salihu, M.D.; Farouq, A.A.; Faleke, O.O.; Adamu, S.G.; Musa, H.I.; Hambali, I.U. Serological survey for Brucella antibodies in donkeys of north-eastern Nigeria. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2017, 49, 1211–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Callaghan, D. Human brucellosis: Recent advances and future challenges. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2020, 9, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawood, A.S.; Elrashedy, A.; Nayel, M.; Salama, A.; Guo, A.; Zhao, G.; Algharib, S.A.; Zaghawa, A.; Zubair, M.; Elsify, A.; et al. Brucellae as resilient intracellular pathogens: Epidemiology, host-pathogen interaction, recent genomics and proteomics approaches, and future perspectives. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1255239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Li, S.; Ma, H.; Akhtar, M.F.; Tan, Y.; Wang, T.; Liu, W.; Khan, A.; Khan, M.Z.; Wang, C. An Overview of Infectious and Non-Infectious Causes of Pregnancy Losses in Equine. Animals 2024, 14, 1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, B.A. Salmonella in Horses. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Equine Pr. 2023, 39, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żychska, M.; Rzewuska, M.; Kizerwetter-Świda, M.; Chrobak-Chmiel, D.; Stefańska, I.; Kwiecień, E.; Witkowski, L. Antimicrobial resistance in bacteria isolated from diseased horses in Poland, 2010-2022. Pol. J. Vet. Sci. 2025, 28, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Y.; Li, W.; Jin, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhou, J.; Tong, D. Seroprevalence of Chlamydia abortus and Brucella spp. and risk factors for Chlamydia abortus in pigs from China. Acta Trop. 2023, 248, 107050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, W.; Black, C.; Smith, A.C. Clinical Implications of Polymicrobial Synergism Effects on Antimicrobial Susceptibility. Pathogens 2021, 10, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, W.H.; Chong, K.K.; Kline, K.A. Polymicrobial-Host Interactions during Infection. J. Mol. Biol. 2016, 428, 3355–3371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, Z.; Fu, H.; Miao, R.; Lu, C.; Zhang, X.; Yuan, Z.; Ji, P.; Hua, Y.; Wang, C.; Ma, Y.; et al. Serological investigation and isolation of Salmonella abortus equi in horses in Xinjiang. BMC Vet. Res. 2024, 20, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Li, Y.; Moumouni, P.F.A.; Lee, S.H.; Galon, E.M.; Tumwebaze, M.A.; Yang, H.; Huercha; Liu, M.; Guo, H.; et al. First description of Coxiella burnetii and Rickettsia spp. infection and molecular detection of piroplasma co-infecting horses in Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, China. Parasitol. Int. 2020, 76, 102028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muroni, G.; Serra, E.; Biggio, G.P.; Sanna, D.; Cherchi, R.; Taras, A.; Appino, S.; Foxi, C.; Masala, G.; Loi, F.; et al. Detection of Chlamydia psittaci in the Genital Tract of Horses and in Environmental Samples: A Pilot Study in Sardinia. Pathogens 2024, 13, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Pérez, A.L.; Zendoia, I.I.; Ferrer, D.; Barandika, J.F.; Ramos, C.; Vera, R.; Martí, T.; Pujol, A.; Cevidanes, A.; Hurtado, A. Combination of serology and PCR analysis of environmental samples to assess Coxiella burnetii infection status in small ruminant farms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2025, 91, e0093125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kithuka, J.M.; Wachira, T.M.; Onono, J.O.; Ngetich, W. The burden of brucellosis in donkeys and its implications for public health and animal welfare: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Vet. World 2025, 18, 367–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Liu, W.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, W.; Qi, P.; Yang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, C.; Wang, W. Characterization of Salmonella isolated from donkeys during an abortion storm in China. Microb. Pathog. 2021, 161, 105080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahrouki, S.; Bourouis, A.; Chihi, H.; Ouertani, R.; Ferjani, M.; Moussa, M.B.; Barguellil, F.; Belhadj, O. First characterisation of plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance-qnrS1 co-expressed bla CTX-M-15 and bla DHA-1 genes in clinical strain of Morganella morganii recovered from a Tunisian Intensive Care Unit. Indian. J. Med. Microbiol. 2012, 30, 437–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Category | Pos./Tested | Prev.% | 95%Cl | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | GanSu | 11/144 | 7.64 | (3.65, 11.63) | X2 = 28.719 p < 0.01 |

| QingHai | 15/116 | 12.93 | (7.01, 18.85) | ||

| XinJiang | 56/200 | 21.79 | (21.79, 34.21) | ||

| SiChuan | 14/48 | 29.17 | (16.38, 41.96) | ||

| Species | Donkey | 13/46 | 28.26 | (15.35, 41.17) | X2 = 2.893 p = 0.089 |

| Horse | 83/462 | 17.97 | (14.50, 21.44) | ||

| Age | ≤5 | 13/63 | 20.63 | (10.75, 30.51) | X2 = 0.599 p = 0.741 |

| 5.1–10 years | 52/293 | 17.75 | (13.38, 22.12) | ||

| >10 years | 31/152 | 20.39 | (14.03, 26.75) | ||

| Sex | Female | 89/470 | 18.94 | (15.37, 22.51) | X2 = 0.006 p = 0.938 |

| Male | 7/38 | 18.42 | (6.30, 30.54) | ||

| Total | 96/508 | 18.90 | (15.48, 22.67) | ||

| Variable | Category | Pos./Tested | Prev.% | 95%Cl | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | GanSu | 9/144 | 6.25 | (0.03, 0.12) | X2 = 18.99 p < 0.01 |

| QingHai | 15/116 | 12.93 | (0.07, 0.20) | ||

| XinJiang | 44/200 | 22.00 | (0.16, 0.28) | ||

| SiChuan | 4/48 | 8.33 | (0.02, 0.17) | ||

| Species | Donkey | 10/46 | 21.73 | (0.11, 0.36) | X2 = 1.75 p = 0.186 |

| Horse | 62/462 | 13.41 | (0.10, 0.17) | ||

| Age | ≤5 | 8/63 | 12.69 | (0.06, 0.23) | X2 = 0.94 p = 0.626 |

| 5.1–10 years | 39/293 | 13.31 | (0.10, 0.18) | ||

| >10 years | 25/152 | 16.67 | (0.11, 0.23) | ||

| Sex | Female | 67/470 | 14.25 | (0.11, 0.18) | X2 = 0.0264 p = 0.871 |

| Male | 5/38 | 13.16 | (0.04, 0.24) | ||

| Total | 72/508 | 14.17 | (0.11, 0.18) | ||

| Variable | Category | Pos./Tested | Prev.% | 95%Cl | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | GanSu | 31/144 | 21.53 | (15.29, 28.94) | X2 = 8.368 p = 0.039 |

| QingHai | 30/116 | 25.86 | (18.36, 34.56) | ||

| XinJiang | 69/200 | 34.50 | (27.90, 41.57) | ||

| SiChuan | 17/48 | 35.42 | (22.38, 50.20) | ||

| Species | Donkey | 15/46 | 32.61 | (19.83, 47.54) | X2 = 0.332 p = 0.565 |

| Horse | 132/462 | 28.57 | (24.54, 32.87) | ||

| Age | ≤5 | 17/63 | 26.98 | (16.80, 39.35) | X2 = 11.664 p < 0.01 |

| 5.1–10 years | 101/293 | 34.47 | (29.12, 40.09) | ||

| >10 years | 29/152 | 19.08 | (13.19, 26.17) | ||

| Sex | Female | 136/470 | 28.94 | (24.91, 33.19) | X2 = 0.000 p = 0.999 |

| Male | 11/38 | 28.95 | (15.77, 45.33) | ||

| Total | 147/508 | 28.94 | (24.89, 33.19) | ||

| Variable | Category | Pos./Tested | Prev.% | 95%Cl | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | GanSu | 19/144 | 13.19 | (0.08, 0.19) | X2 = 2.18 p = 0.536 |

| QingHai | 15/116 | 12.93 | (0.07, 0.19) | ||

| XinJiang | 36/200 | 18.00 | (0.13, 0.24) | ||

| SiChuan | 8/48 | 16.67 | (0.06, 0.27) | ||

| Species | Donkey | 6/46 | 13.04 | (0.43, 0.23) | X2 = 0.06 p = 0.809 |

| Horse | 72/462 | 15.58 | (0.12, 0.19) | ||

| Age | ≤5 | 17/63 | 26.98 | (0.16, 0.38) | X2 = 10.10 p < 0.01 |

| 5.1–10 years | 46/293 | 15.70 | (0.12, 0.20) | ||

| >10 years | 15/152 | 9.87 | (0.05, 0.15) | ||

| Sex | Female | 70/470 | 8.09 | (0.06, 0.11) | X2 = 0.61 p = 0.436 |

| Male | 8/38 | 21.05 | (0.08, 0.34) | ||

| Total | 78/508 | 15.35 | (0.12, 0.18) | ||

| Variable | Category | Pos./Tested | Prev.% | 95%Cl | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | GanSu | 4/144 | 2.08 | (0.43, 6.00) | X2 = 10.19 p = 0.017 |

| QingHai | 0/116 | 0.00 | (0.00, 3.16) | ||

| XinJiang | 0/200 | 0.00 | (0.00, 7.40) | ||

| SiChuan | 0/48 | 0.00 | (0.00, 7.40) | ||

| Species | donkey | 0/46 | 0.00 | (0.00, 7.70) | X2 = 0.401 p = 0.526 |

| horse | 4/462 | 0.87 | (0.24, 2.21) | ||

| Age | ≤5 | 1/63 | 1.59 | (0.04, 8.51) | X2 = 1.932 p = 0.381 |

| 5.1–10 years | 3/293 | 1.02 | (0.21, 2.97) | ||

| >10 years | 0/152 | 0.00 | (0.00, 2.41) | ||

| Sex | Female | 4/470 | 0.85 | (0.23, 2.17) | X2 = 0.326 p = 0.568 |

| Male | 0/38 | 0.00 | (0.00, 9.26) | ||

| Total | 4/508 | 0.78 | (0.21, 1.99) | ||

| Variable | Category | Pos./Tested | Prev.% | 95%Cl | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | GanSu | 41/144 | 28.47 | (21.42, 36.35) | X2 = 14.195 p = 0.003 |

| QingHai | 37/116 | 31.90 | (23.69, 41.04) | ||

| XinJiang | 89/200 | 44.50 | (37.45, 51.72) | ||

| SiChuan | 11/48 | 22.92 | (12.26, 37.03) | ||

| Species | Donkey | 41/46 | 89.13 | (76.43, 96.43) | X2 = 65.017 p < 0.01 |

| Horse | 137/462 | 29.65 | (25.56, 33.98) | ||

| Age | ≤5 | 14/63 | 22.22 | (12.97, 34.21) | X2 = 6.761 p = 0.034 |

| 5.1–10 years | 102/293 | 34.81 | (29.41, 40.52) | ||

| >10 years | 62/152 | 40.79 | (33.03, 48.92) | ||

| Sex | Female | 172/470 | 36.60 | (32.18, 41.19) | X2 = 6.687 p = 0.010 |

| Male | 6/38 | 15.79 | (6.05, 31.34) | ||

| Total | 178/508 | 35.03 | (30.83, 39.39) | ||

| Variable | Category | Pos./Tested | Prev.% | 95%Cl | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | GanSu | 33/144 | 22.92 | (0.16, 0.30) | X2 = 1.93 p = 0.587 |

| QingHai | 25/116 | 21.55 | (0.15, 0.29) | ||

| XinJiang | 51/200 | 25.5 | (0.20, 0.32) | ||

| SiChuan | 8/48 | 16.67 | (0.06, 0.27) | ||

| Species | Donkey | 35/46 | 76.09 | (0.63, 0.87) | X2 = 77.06 p < 0.001 |

| Horse | 82/462 | 17.75 | (0.14, 0.21) | ||

| Age | ≤5 | 6/63 | 9.52 | (0.03, 0.17) | X2 = 7.40 p = 0.025 |

| 5.1–10 years | 73/293 | 24.91 | (0.20, 0.30) | ||

| >10 years | 38/152 | 25.00 | (0.18, 0.32) | ||

| Sex | Female | 106/470 | 22.55 | (0.19, 0.26) | X2 = 0.49 p = 0.484 |

| Male | 11/38 | 28.95 | (0.16, 0.45) | ||

| Total | 117/508 | 23.03 | (0.19, 0.26) | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gao, W.; Liu, M.; Nurdaly, K.; Caidan, D.; Sun, Y.; Duan, J.; Zhao, J.; Gong, X.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Unveiling Equine Abortion Pathogens: A One Health Perspective on Prevalence and Resistance in Northwest China. Pathogens 2025, 14, 1275. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121275

Gao W, Liu M, Nurdaly K, Caidan D, Sun Y, Duan J, Zhao J, Gong X, Zhou J, Zhang Y, et al. Unveiling Equine Abortion Pathogens: A One Health Perspective on Prevalence and Resistance in Northwest China. Pathogens. 2025; 14(12):1275. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121275

Chicago/Turabian StyleGao, Wei, Mengyao Liu, Kastai Nurdaly, Duojie Caidan, Yunlong Sun, Jingang Duan, Jiangshan Zhao, Xiaowei Gong, Jizhang Zhou, Yong Zhang, and et al. 2025. "Unveiling Equine Abortion Pathogens: A One Health Perspective on Prevalence and Resistance in Northwest China" Pathogens 14, no. 12: 1275. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121275

APA StyleGao, W., Liu, M., Nurdaly, K., Caidan, D., Sun, Y., Duan, J., Zhao, J., Gong, X., Zhou, J., Zhang, Y., & Chen, Q. (2025). Unveiling Equine Abortion Pathogens: A One Health Perspective on Prevalence and Resistance in Northwest China. Pathogens, 14(12), 1275. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121275