Canine Ticks, Tick-Borne Pathogens and Associated Risk Factors in Nigeria

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Approval, Questionnaire Design/Consent Form and Sample/Demographic Data Collection

2.2. IDEXX® Antigen Kit Testing on Canine Blood

2.3. DNA Extraction and Polymerase Chain Reaction, Gel Electrophoresis and Sanger Sequencing

2.4. Hard 16S rRNA Gene PCR

2.5. Babesia, Ehrlichia, Borrelia, and Dirofilaria PCR Detection

2.6. Agarose Gel Electrophoresis and Sanger Sequencing and Analysis

2.7. Descriptive Statistics and Multivariate Modelling

3. Results

3.1. Canine Tick Morphology and Molecular Barcoding

3.2. Characteristics of the Canine Population Assessed for TBPs Using POC and PCR

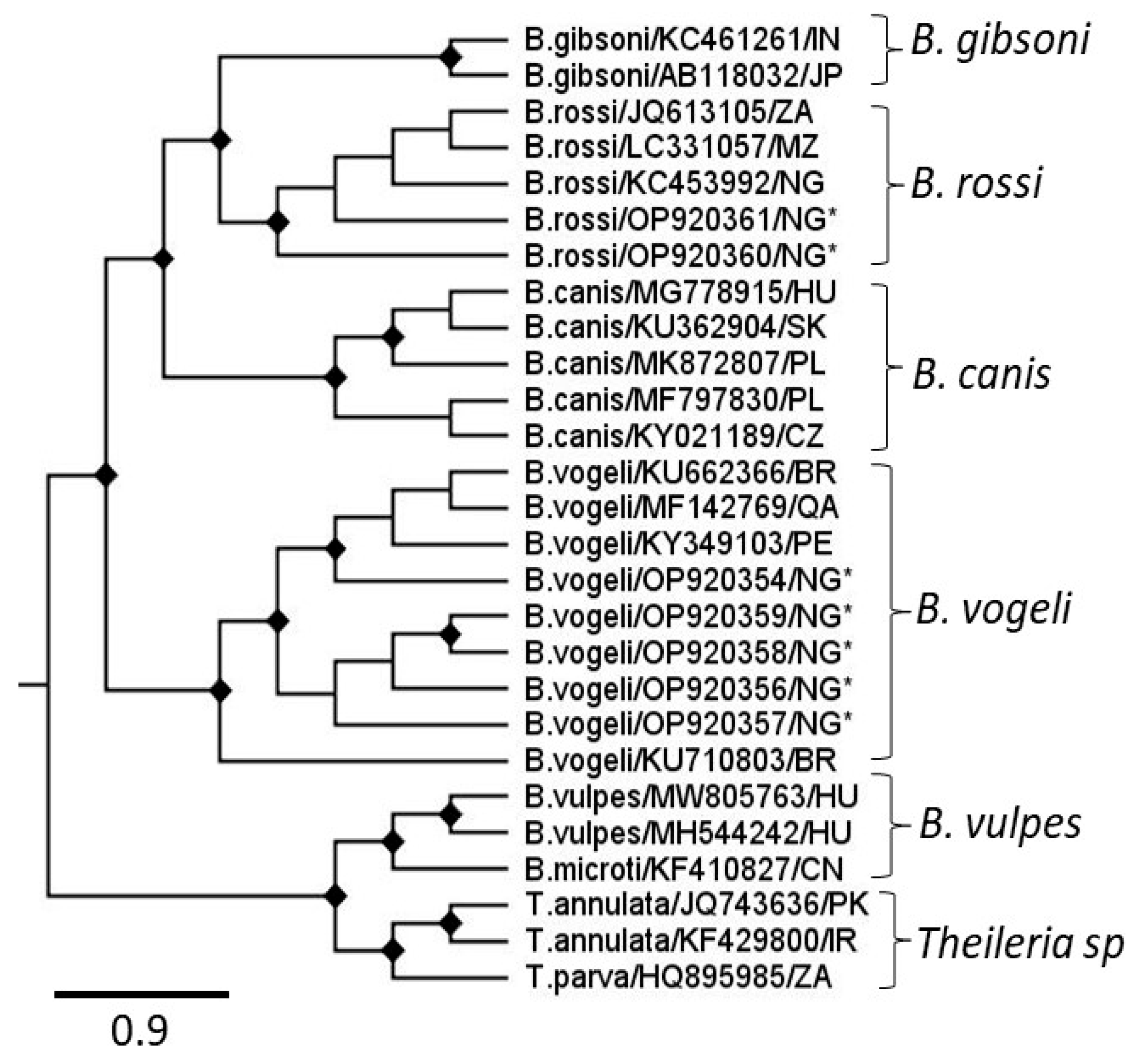

3.3. Prevalence of TBPs Based on PCR

3.4. Risk Factors Associated with Canine TBPs Based on PCR Detection

4. Discussion

4.1. Tick Species Infesting Nigerian Dogs

4.2. Detection of Babesia, Ehrlichia sp. and Anaplasma sp. in Nigerian Dogs Using POC and PCR Tests

4.3. Low Prevalence of Dirofilaria sp. and the Absence of B. burgdorferi (s.l) Using POC and PCR Tests

4.4. Risk Factors Associated with Canine Tick Infestation and Tick-Borne Pathogens in Nigeria

5. Limitation and Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Balling, A.; Beer, M.; Gniel, D.; Pfeffer, M. Prevalence of antibodies against Tick-Borne Encephalitis virus in dogs from Saxony, Germany. Berl. Munch. Tierarztl. Wochenschr. 2015, 128, 297–303. Available online: http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/26281442 (accessed on 9 February 2023). [PubMed]

- de Marco, M.D.F.; Hernandez-Triana, L.M.; Phipps, L.P.; Hansford, K.; Mitchell, E.S.; Cull, B.; Swainsbury, C.S.; Fooks, A.R.; Medlock, J.M.; Johnson, N. Emergence of Babesia canis in southern England. Parasites Vectors 2017, 10, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogo, N.I.; de Mera, I.G.F.; Galindo, R.C.; Okubanjo, O.O.; Inuwa, H.M.; Agbede, R.I.S.; Torina, A.; Alongi, A.; Vicente, J.; Gortázar, C.; et al. Molecular identification of tick-borne pathogens in Nigerian ticks. Vet. Parasitol. 2012, 187, 572–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnarelli, L.A. Global importance of ticks and associated infectious disease agents. Clin. Microbiol. Newsl. 2009, 31, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jongejan, F.; Uilenberg, G. The global importance of ticks. Parasitology 2004, 129, S3–S14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eppleston, K.R.; Kelman, M.; Ward, M.P. Distribution, seasonality and risk factors for tick paralysis in Australian dogs and cats. Vet. Parasitol. 2013, 196, 460–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kryda, K.; Mahabir, S.P.; Chapin, S.; Holzmer, S.J.; Bowersock, L.; Everett, W.R.; Riner, J.; Carter, L.; Young, D. Efficacy of a novel orally administered combination product containing sarolaner, moxidectin and pyrantel (Simparica Trio) against induced infestations of five common tick species infesting dogs in the USA. Parasites Vectors 2020, 13, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, P.J. It shouldn’t happen to a dog… or a veterinarian: Clinical paradigms for canine vector-borne diseases. Trends Parasitol. 2014, 30, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otranto, D.; Dantas-Torres, F.; Breitschwerdt, E.B. Managing canine vector-borne diseases of zoonotic concern: Part one. Trends Parasitol. 2009, 25, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attipa, C.; Hicks, C.A.; Barker, E.N.; Christodoulou, V.; Neofytou, K.; Mylonakis, M.E.; Siarkou, V.I.; Vingopoulou, E.I.; Soutter, F.; Chochlakis, D.; et al. Canine tick-borne pathogens in Cyprus and a unique canine case of multiple co-infections. Ticks Ticks Borne Dis. 2017, 8, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Springer, A.; Glass, A.; Topp, A.K.; Strube, C. Zoonotic Tick-Borne Pathogens in Temperate and Cold Regions of Europe-A Review on the Prevalence in Domestic Animals. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 604910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkishe, A.A.; Peterson, A.T.; Samy, A.M. Climate change influences on the potential geographic distribution of the disease vector tick Ixodes ricinus. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0189092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olwoch, J.M.; Van Jaarsveld, A.S.; Scholtz, C.H.; Horak, I.G. Climate change and the genus Rhipicephalus (Acari: Ixodidae) in Africa. Onderstepoort J. Vet. Res. 2007, 74, 45–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Hohman, A.E.; Hsu, W.H. Current review of isoxazoline ectoparasiticides used in veterinary medicine. J. Vet. Pharmacol. Ther. 2022, 45, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Fuente, J.; Merino, O. Vaccinomics, the new road to tick vaccines. Vaccine 2013, 31, 5923–5929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otranto, D.; Wall, R. New strategies for the control of arthropod vectors of disease in dogs and cats. Med. Vet. Entomol. 2008, 22, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofukwu, R.; Ogbaje, C.; Akwuobu, C. Preliminary study of the epidemiology of ectoparasite infestation of goats and sheep in Makurdi, north central Nigeria. Sokoto J. Vet. Sci. 2008, 7, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorusso, V.; Picozzi, K.; de Bronsvoort, B.M.; Majekodunmi, A.; Dongkum, C.; Balak, G.; Igweh, A.; Welburn, S.C. Ixodid ticks of traditionally managed cattle in central Nigeria: Where Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) microplus does not dare (yet?). Parasites Vectors 2013, 6, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamani, J.; Apanaskevich, D.; Gutiérrez, R.; Nachum-Biala, Y.; Baneth, G.; Harrus, S. Morphological and molecular identification of Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) microplus in Nigeria, West Africa: A threat to livestock health. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 2017, 73, 283–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daramola, O.O.; Takeet, M.I.; Oyewusi, I.K.; Oyekunle, M.A.; Talabi, A.O. Detection and molecular characterisation of Ehrlichia canis in naturally infected dogs in South West Nigeria. Acta Vet. Hung. 2018, 66, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamu, M.; Troskie, M.; Oshadu, D.O.; Malatji, D.P.; Penzhorn, B.L.; Matjila, P.T. Occurrence of tick-transmitted pathogens in dogs in Jos, Plateau State, Nigeria. Parasites Vectors 2014, 7, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Happi, A.N.; Toepp, A.J.; Ugwu, C.; Petersen, C.A.; Sykes, J.E. Detection and identification of blood-borne infections in dogs in Nigeria using light microscopy and the polymerase chain reaction. Vet. Parasitol. Reg. Stud. Rep. 2018, 11, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, A.R. Ticks of Domestic Animals in Africa: A Guide to Identification of Species; Bioscience Reports: Edinburgh, UK, 2003; pp. 3–210. [Google Scholar]

- Stillman, B.A.; Monn, M.; Liu, J.; Thatcher, B.; Foster, P.; Andrews, B.; Little, S.; Eberts, M.; Breitschwerdt, E.B.; Beall, M.J.; et al. Performance of a commercially available in-clinic ELISA for detection of antibodies against Anaplasma phagocytophilum, Anaplasma platys, Borrelia burgdorferi, Ehrlichia canis, and Ehrlichia ewingii and Dirofilaria immitis antigen in dogs. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2014, 245, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pantchev, N.; Pluta, S.; Huisinga, E.; Nather, S.; Scheufelen, M.; Vrhovec, M.G.; Schweinitz, A.; Hampel, H.; Straubinger, R.K. Tick-borne Diseases (borreliosis, anaplasmosis, babesiosis) in German and Austrian dogs: Status quo and review of distribution, transmission, clinical findings, diagnostics and prophylaxis. Parasitol. Res. 2015, 114 (Suppl. S1), S19–S54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, S.; Saleh, M.; Wohltjen, M.; Nagamori, Y. Prime detection of Dirofilaria immitis: Understanding the influence of blocked antigen on heartworm test performance. Parasites Vectors 2018, 11, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aroch, I.; Rojas, A.; Slon, P.; Lavy, E.; Segev, G.; Baneth, G. Serological cross-reactivity of three commercial in-house immunoassays for detection of Dirofilaria immitis antigens with Spirocerca lupi in dogs with benign esophageal spirocercosis. Vet. Parasitol. 2015, 211, 303–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, W.C.; Piesman, J. Phylogeny of hard-and soft-tick taxa (Acari: Ixodida) based on mitochondrial 16S rDNA sequences. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1994, 91, 10034–10038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, P.M.; Katavolos, P.; Caporale, D.A.; Smith, R.P.; Spielman, A.; Telford 3rd, S. Diversity of Babesia infecting deer ticks (Ixodes dammini). Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1998, 58, 739–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breitschwerdt, E.B.; Hegarty, B.C.; Hancock, S.I. Sequential evaluation of dogs naturally infected with Ehrlichia canis, Ehrlichia chaffeensis, Ehrlichia equi, Ehrlichia ewingii, or Bartonella vinsonii. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1998, 36, 2645–2651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionita, M.; Mitrea, I.L.; Pfister, K.; Hamel, D.; Silaghi, C. Molecular evidence for bacterial and protozoan pathogens in hard ticks from Romania. Vet. Parasitol. 2013, 196, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parola, P.; Diatta, G.; Socolovschi, C.; Mediannikov, O.; Tall, A.; Bassene, H.; Trape, J.F.; Raoult, D. Tick-borne relapsing fever borreliosis, rural Senegal. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2011, 17, 883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronefeld, M.; Kampen, H.; Sassnau, R.; Werner, D. Molecular detection of Dirofilaria immitis, Dirofilaria repens and Setaria tundra in mosquitoes from Germany. Parasites Vectors 2014, 7, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarlinton, R.E.; Barfoot, H.K.; Allen, C.E.; Brown, K.; Gifford, R.J.; Emes, R.D. Characterisation of a group of endogenous gammaretroviruses in the canine genome. Vet. J. 2013, 196, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearse, M.; Moir, R.; Wilson, A.; Stones-Havas, S.; Cheung, M.; Sturrock, S.; Buxton, S.; Cooper, A.; Markowitz, S.; Duran, C.; et al. Geneious basic: An integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 1647–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altschul, S.F.; Gish, W.; Miller, W.; Myers, E.W.; Lipman, D.J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990, 215, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gray, J.; Dantas-Torres, F.; Estrada-Peña, A.; Levin, M. Systematics and ecology of the brown dog tick, Rhipicephalus sanguineus. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2013, 4, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barker, S.C.; Murrell, A. Systematics and evolution of ticks with a list of valid genus and species names. Parasitology 2004, 129 (Suppl. S1), S15–S36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamani, J. Molecular identification and genetic analysis of Rhipicephalus sanguineus sensu lato of dogs in Nigeria, West Africa. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 2021, 85, 277–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, A.T.; Dominguez, K.; Cleveland, C.A.; Dergousoff, S.J.; Doi, K.; Falco, R.C.; Greay, T.; Irwin, P.; Lindsay, L.R.; Liu, J.; et al. Molecular characterization of Haemaphysalis species and a molecular genetic key for the identification of Haemaphysalis of North America. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lack, J.B.; Reichard, M.V.; Van Den Bussche, R.A. Phylogeny and evolution of the Piroplasmida as inferred from 18S rRNA sequences. Int. J. Parasitol. 2012, 42, 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyaanamoorthy, S.; Minh, B.Q.; Wong, T.K.F.; von Haeseler, A.; Jermiin, L.S. ModelFinder: Fast model selection for accurate phylogenetic estimates. Nat. Methods 2017, 14, 587–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K. Estimation of the number of nucleotide substitutions when there are strong transition-transversion and G+C-content biases. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1992, 9, 678–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jukes, T.H.; Cantor, C.R. Chapter 24—Evolution of Protein Molecules. In Mammalian Protein Metabolism; Munro, H.N., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1969; pp. 21–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkwood, B.R.; Sterne, J.A. Essential Medical Statistics; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; pp. 3–450. [Google Scholar]

- Kamani, J.; Baneth, G.; Mumcuoglu, K.Y.; Waziri, N.E.; Eyal, O.; Guthmann, Y.; Harrus, S. Molecular detection and characterization of tick-borne pathogens in dogs and ticks from Nigeria. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2013, 7, e2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adang, K.; Ayuba, J.; Yoriyo, K. Ectoparasites of sheep (Ovis aries, L.) and Goats (Capra hirus, L.) in Gombe, Gombe State, Nigeria. Pak. J. Biol. Sci. 2015, 18, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opara, M.N.; Adewumi, T.S.; Mohammed, B.R.; Obeta, S.S.; Simon, M.K.; Jegede, O.C.; Agbede, R. Investigations on the haemoprotozoan parasites of Nigerian local breed of dogs in Gwagwalada Federal Capital Territory (FCT) Nigeria. Res. J. Parasitol. 2017, 12, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmanuel, O.I.; Anyebe, A.A.; Agbo, O.E.; Odeh, U.P.; Love, O.; Agogo, I.M. A Preliminary survey of ectoparasites and their predilection sites on some livestock sold in Wadata market, Makurdi, Nigeria. Am. J. Entomol. 2017, 1, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamani, J. Molecular evidence indicts Haemaphysalis leachi (Acari: Ixodidae) as the vector of Babesia rossi in dogs in Nigeria, West Africa. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2021, 12, 101717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruenberger, I.; Liebich, A.-V.; Ajibade, T.O.; Obebe, O.O.; Ogbonna, N.F.; Wortha, L.N.; Unterköfler, M.S.; Fuehrer, H.-P.; Ayinmode, A.B. Vector-borne pathogens in guard dogs in Ibadan, Nigeria. Pathogens 2023, 12, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamani, J.; Lee, C.-C.; Haruna, A.M.; Chung, P.-J.; Weka, P.R.; Chung, Y.-T. First detection and molecular characterization of Ehrlichia canis from dogs in Nigeria. Res. Vet. Sci. 2013, 94, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamani, J.; Baneth, G.; Harrus, S. An annotated checklist of tick-borne pathogens of dogs in Nigeria. Vet. Parasitol. Reg. Stud. Rep. 2019, 15, 100255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breitschwerdt, E.B.; Maggi, R.G. A confusing case of canine vector-borne disease: Clinical signs and progression in a dog co-infected with Ehrlichia canis and Bartonella vinsonii ssp. berkhoffii. Parasites Vectors 2009, 2 (Suppl. S1), S3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyers, A.C.; Auckland, L.; Meyers, H.F.; Rodriguez, C.A.; Kontowicz, E.; Petersen, C.A.; Travi, B.L.; Sanders, J.P.; Hamer, S.A. Epidemiology of Vector-Borne Pathogens Among, U.S. Government Working Dogs. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2021, 21, 358–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogbaje, C.I.; Danjuma, A. Prevalence and risk factors associated with Dirofilaria immitis infection in dogs in Makurdi, Benue State, Nigeria. J. Adv. Vet. Anim. Res. 2016, 3, 338–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.; Feng, X.; Rong, H.; Pan, Z.; Inaba, Y.; Qiu, L.; Zheng, W.; Lin, S.; Wang, R.; Wang, Z.; et al. The antiparasitic drug ivermectin is a novel FXR ligand that regulates metabolism. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKellar, Q.A.; Gokbulut, C. Pharmacokinetic features of the antiparasitic macrocyclic lactones. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2012, 13, 888–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolstenholme, A.J.; Maclean, M.J.; Coates, R.; McCoy, C.J.; Reaves, B.J. How do the macrocyclic lactones kill filarial nematode larvae? Invertebr. Neurosci. 2016, 16, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selim, A.; Alanazi, A.D.; Sazmand, A.; Otranto, D. Seroprevalence and associated risk factors for vector-borne pathogens in dogs from Egypt. Parasites Vectors 2021, 14, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzag, N.; Petit, E.; Gandoin, C.; Bouillin, C.; Ghalmi, F.; Haddad, N.; Boulouis, H.-J. Prevalence of select vector-borne pathogens in stray and client-owned dogs from Algiers. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2015, 38, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krupka, I.; Straubinger, R.K. Lyme borreliosis in dogs and cats: Background, diagnosis, treatment and prevention of infections with Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Small Anim. Pract. 2010, 40, 1103–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudenko, N.; Golovchenko, M.; Grubhoffer, L.; Oliver, J.H. Updates on Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato complex with respect to public health. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2011, 2, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.-J.; Sun, H.-J.; Wu, Y.-C.; Huang, H.-P. Prevalence and risk factors of canine ticks and tick-borne diseases in Taipei, Taiwan. J. Vet. Clin. Sci. 2009, 2, 75–78. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:90724482 (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Rivera Villar, J.; Aquino Escalante, I.; Chuchón Martínez, S.; Gastelú Quispe, R.; Huamán de la Cruz, R.; Sandoval Juarez, A.; Mendoza Mujica, G.; Rojas Palomino, N. Seroprevalence and Risk Factor for Canine Tick-Borne Disease in Urban-Rural Area in Ayacucho, Peru. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2025, 10, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dürr, S.; Dhand, N.; Bombara, C.; Molloy, S.; Ward, M. What influences the home range size of free-roaming domestic dogs? Epidemiol. Infect. 2017, 145, 1339–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuk, M.; McKean, K.A. Sex differences in parasite infections: Patterns and processes. Int. J. Parasitol. 1996, 26, 1009–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latre de Late, P.; Cook, E.A.J.; Wragg, D.; Poole, E.J.; Ndambuki, G.; Miyunga, A.A.; Chepkwony, M.C.; Mwaura, S.; Ndiwa, N.; Prettejohn, G.; et al. Inherited tolerance in cattle to the apicomplexan protozoan Theileria parva is associated with decreased proliferation of parasite-infected lymphocytes. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 751671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wragg, D.; Cook, E.A.J.; Latre de Late, P.; Sitt, T.; Hemmink, J.D.; Chepkwony, M.C.; Njeru, R.; Poole, E.J.; Powell, J.; Paxton, E.A.; et al. A locus conferring tolerance to Theileria infection in African cattle. PLoS Genet. 2022, 18, e1010099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioia, G.; Lecová, L.; Genchi, M.; Ferri, E.; Genchi, C.; Mortarino, M. Highly sensitive multiplex PCR for simultaneous detection and discrimination of Dirofilaria immitis and Dirofilaria repens in canine peripheral blood. Vet. Parasitol. 2010, 172, 160–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borthakur, S.K.; Deka, D.K.; Islam, S.; Sarma, D.K.; Sarmah, P.C. Prevalence and molecular epidemiological data on Dirofilaria immitis in dogs from Northeastern States of India. Sci. World J. 2015, 2015, 265385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trancoso, T.A.L.; Lima, N.C.; Barbosa, A.S.; Leles, D.; Fonseca, A.B.M.; Labarthe, N.V.; Bastos, O.M.P.; Uchôa, C.M.A. Detection of Dirofilaria immitis using microscopic, serological and molecular techniques among dogs in Cabo Frio, RJ, Brazil. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 2020, 29, e017219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vada, R.; Zanet, S.; Trisciuoglio, A.; Varzandi, A.R.; Calcagno, A.; Ferroglio, E. A one-health approach to surveillance of tick-borne pathogens across different host groups. BMC Vet. Res. 2025, 21, 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| (A). Prevalence of Pathogens Detected by POC Test | |||

| Pathogen | POC Positive (n) | Prevalence (%) | 95% CI |

| Single pathogen | |||

| Ehrlichia sp. | 77/259 | 29.7 | 24.3–35.5 |

| Anaplasma sp. | 28/259 | 10.8 | 6.9–14.7 |

| Dirofilaria sp. | 1/259 | 0.4 | 0.0–1.2 |

| Total | 106/259 | 40.9 | |

| Mixed infection | |||

| Ehrlichia sp. + Anaplasma sp. | 20/259 | 7.7 | |

| Dirofilaria + Ehrlichia sp. | 1/259 | 0.4 | |

| Total | 21/259 | 8.1 | |

| (B). Prevalence TBPs Detected by qPCR | |||

| Pathogen | qPCR-Positive (n) | Prevalence (%) | 95% CI |

| Single infection | |||

| Babesia sp. | 45/259 | 17.4 | 12.7–22.4 |

| Ehrlichia canis | 105/259 | 40.5 | 34.7–46.7 |

| Anaplasma platys | 2/259 | 0.8 | 0.00–0.02 |

| Total | 152/259 | 58.7 | |

| Mixed infection | |||

| Babesia sp. + Ehrlichia sp. | 19/259 | 7.3 | |

| Ehrlichia sp. + Anaplasma sp. | 2/259 | 0.8 | |

| Total | 21 | 8.1 | |

| A | Variable | Adjusted OR | 95% CI | p value |

| Age | ||||

| Young–adult | Reference | |||

| Puppy | 0.3 | 0.15–0.64 | 0.002 * | |

| Ectoparasites (ticks) | ||||

| Yes | Reference | |||

| No | 1.7 | 0.99–3.03 | 0.054 * | |

| B | Variable | Adjusted OR | 95% CI | p value |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | Reference | |||

| Female | 1.7 | 1.02–2.86 | 0.041 * |

| Variable | Adjusted OR | 95% CI | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Breed | |||

| Exotic | Reference | ||

| Indigenous | 0.5 | 0.27–0.82 | 0.008 * |

| Season | |||

| Rainy (April–October) | Reference | ||

| Dry (November–March) | 0.5 | 0.28–0.86 | 0.013 * |

| Pathogen Species | POC Test: % (n) | PCR-Based Test: % (n) | p Value (KCI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | Positive | PCR +ve from POC−ve | ||

| Ehrlichia canis | 29.7 (77) | 70.3 (182) | 40.5 (105) | 28.6 (74) | 0.9 (−0.04–0.06) |

| Anaplasma | 10.8 (28) | 89.2 (231) | 0.8 (2) | 0.4 (1) | 0.7 (0.53–0.59) |

| Dirofilaria | 0.4 (1) | 99.6 (258) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | Np |

| Babesia | Np | Np | 17.4 (45) | Np | Np |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Apaa, T.T.; Oke, P.O.; Shima, F.K.; Fidelis, G.A.; Dunham, S.; Tarlinton, R. Canine Ticks, Tick-Borne Pathogens and Associated Risk Factors in Nigeria. Pathogens 2025, 14, 1271. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121271

Apaa TT, Oke PO, Shima FK, Fidelis GA, Dunham S, Tarlinton R. Canine Ticks, Tick-Borne Pathogens and Associated Risk Factors in Nigeria. Pathogens. 2025; 14(12):1271. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121271

Chicago/Turabian StyleApaa, Ternenge Thaddaeus, Philip Oladele Oke, Felix Kundu Shima, Gberindyer Aondover Fidelis, Stephen Dunham, and Rachael Tarlinton. 2025. "Canine Ticks, Tick-Borne Pathogens and Associated Risk Factors in Nigeria" Pathogens 14, no. 12: 1271. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121271

APA StyleApaa, T. T., Oke, P. O., Shima, F. K., Fidelis, G. A., Dunham, S., & Tarlinton, R. (2025). Canine Ticks, Tick-Borne Pathogens and Associated Risk Factors in Nigeria. Pathogens, 14(12), 1271. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121271