Genome Mining of Cronobacter sakazakii in Bangladesh Reveals the Occurrence of High-Risk ST83 and Rare ST789 Lineages

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Isolation and Identification of the C. sakazakii Isolates

2.2. DNA Extraction and Whole Genome Sequencing

2.3. Genome Sequence Assembly, Identification, and Annotation

2.4. Phylogenetic and Pan-Genome Analysis

2.5. Detection of Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) and Virulence Genes, Mobile Genetic Elements, and Other Characterization

3. Results

3.1. General Features of the Isolated C. sakazakii Strains

3.2. Identification and Genome Annotation

3.3. Phylogenetic and Pan-Genome Analysis

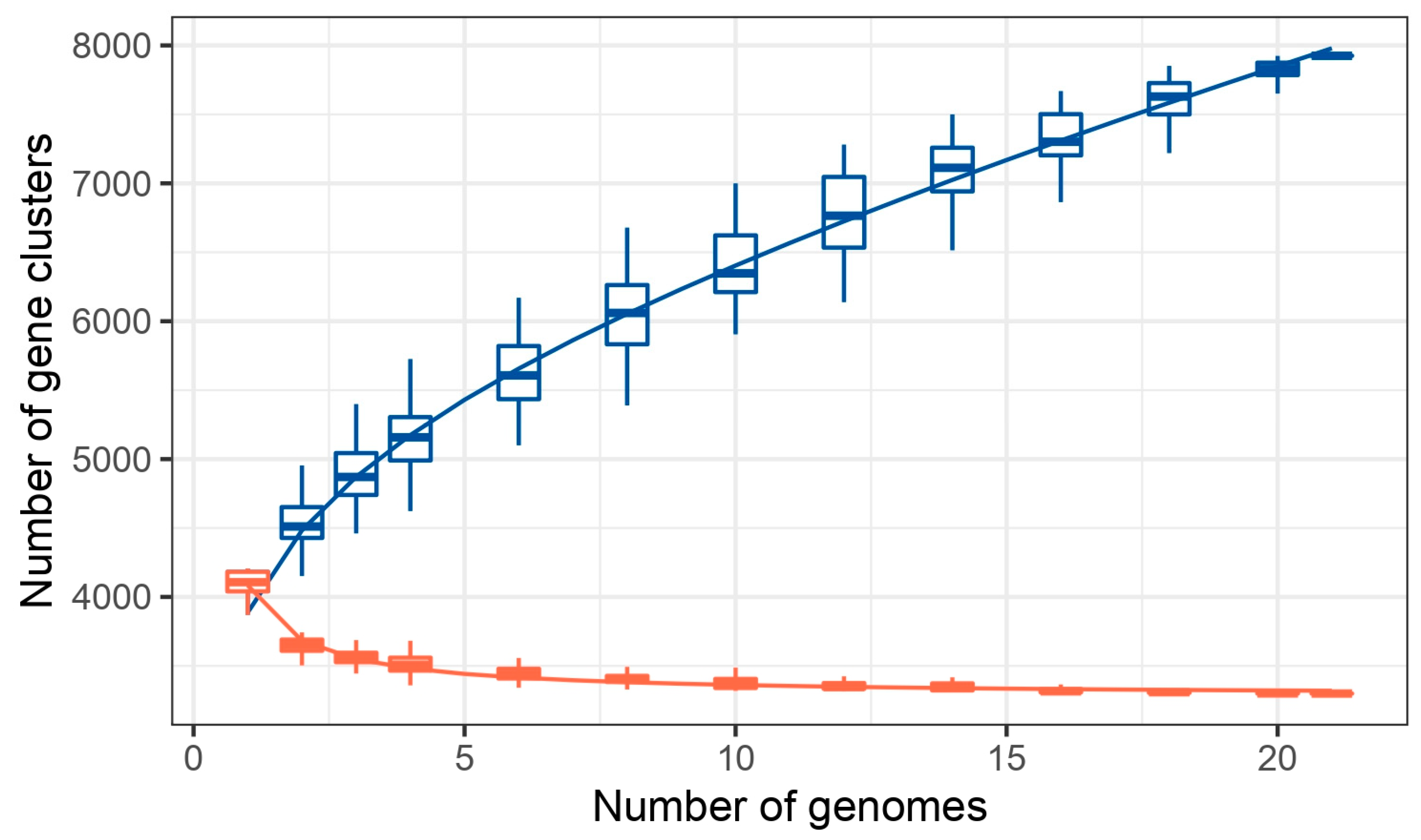

3.4. Antimicrobial Resistance Genes

3.5. Virulence Factors

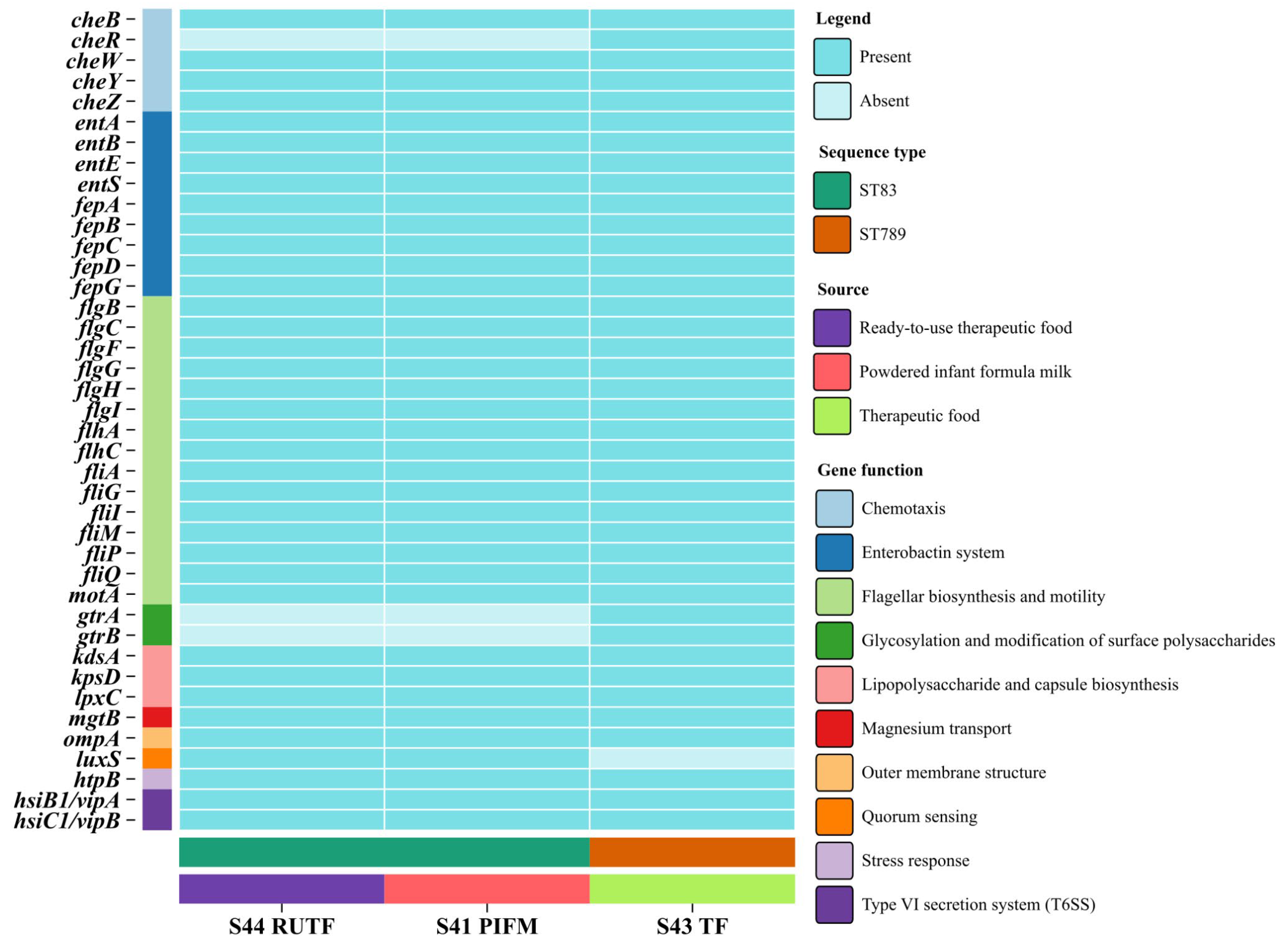

3.6. Prophages, Plasmids, and Other Mobile Genetic Elements

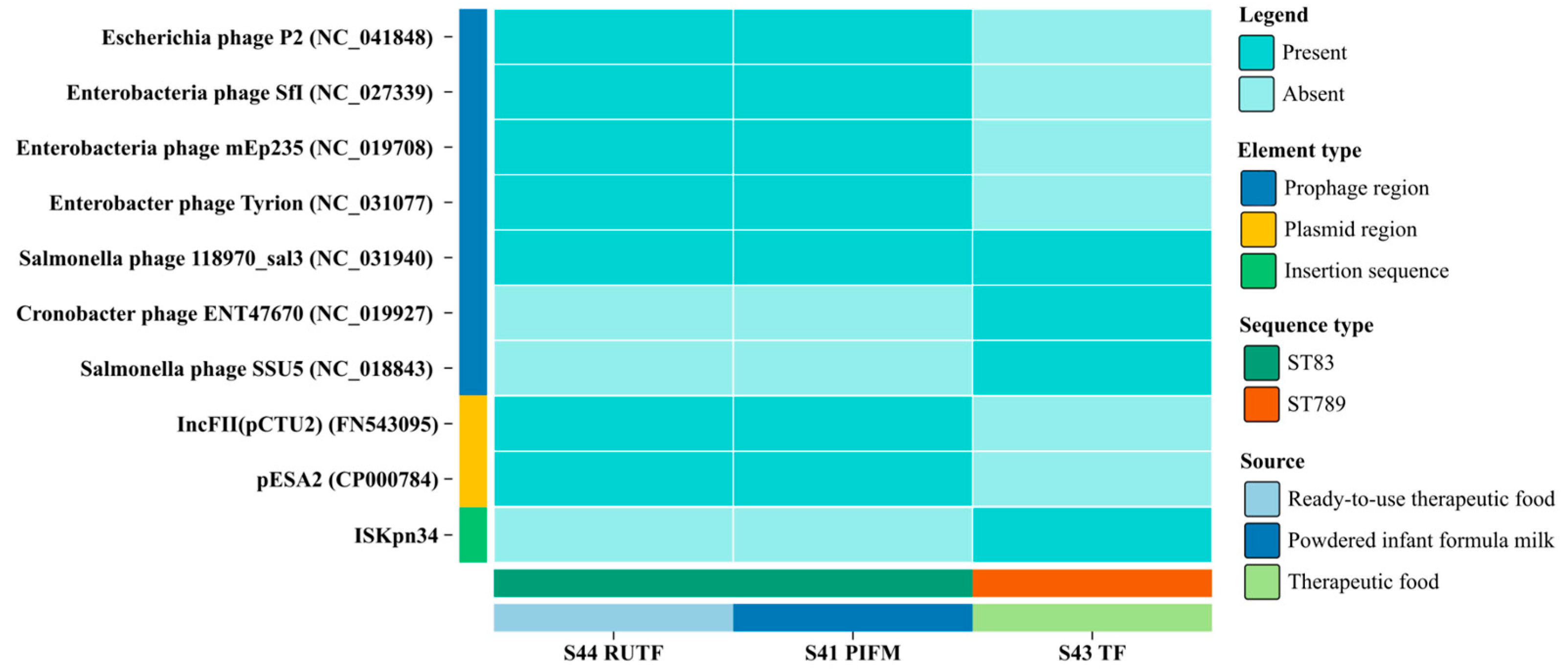

3.7. Detection of CRSIPR

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Joseph, S.; Forsythe, S. Insights into the Emergent Bacterial Pathogen Cronobacter spp., Generated by Multilocus Sequence Typing and Analysis. Front. Microbiol. 2012, 3, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kucerova, E.; Joseph, S.; Forsythe, S. The Cronobacter Genus: Ubiquity and Diversity. Qual. Assur. Saf. Crops Foods 2011, 3, 104–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsythe, S.J. Updates on the Cronobacter Genus. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 9, 23–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lepuschitz, S.; Ruppitsch, W.; Pekard-Amenitsch, S.; Forsythe, S.J.; Cormican, M.; Mach, R.L.; Piérard, D.; Allerberger, F. Multicenter Study of Cronobacter sakazakii Infections in Humans, Europe, 2017. Emerg. Infect. Dis. J. 2019, 25, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holý, O.; Petrželová, J.; Hanulík, V.; Chromá, M.; Matoušková, I.; Forsythe, S.J. Epidemiology of Cronobacter spp. Isolates from Patients Admitted to the Olomouc University Hospital (Czech Republic). Epidemiol. Mikrobiol. Imunol. 2014, 63, 69–72. [Google Scholar]

- Holý, O.; Forsythe, S. Cronobacter spp. as Emerging Causes of Healthcare-Associated Infection. J. Hosp. Infect. 2014, 86, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleiman, M.B.; Allen, S.D.; Neal, P.; Reynolds, J. Meningoencephalitis and Compartmentalization of the Cerebral Ventricles Caused by Enterobacter sakazakii. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1981, 14, 352–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, Z.E.; Koolman, L.; Macori, G.; Fanning, S.; Butler, F. Comprehensive Genomic Characterization of Cronobacter sakazakii Isolates from Infant Formula Processing Facilities Using Whole-Genome Sequencing. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beuchat, L.R.; Kim, H.; Gurtler, J.B.; Lin, L.-C.; Ryu, J.-H.; Richards, G.M. Cronobacter sakazakii in Foods and Factors Affecting Its Survival, Growth, and Inactivation. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2009, 136, 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaker, R.; Osaili, T.; Al-Omary, W.; Jaradat, Z.; Al-Zuby, M. Isolation of Enterobacter sakazakii and Other Enterobacter sp. from Food and Food Production Environments. Food Control 2007, 18, 1241–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Enterobacter sakazakii (Cronobacter spp.) in Powdered Follow-Up Formula: Meeting Report; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2008; Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/9860acca-855b-4960-8b79-74ccf01c16d7/content (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Barron, J.C.; Forsythe, S.J. Dry Stress and Survival Time of Enterobacter sakazakii and Other Enterobacteriaceae in Dehydrated Powdered Infant Formula. J. Food Prot. 2007, 70, 2111–2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekundayo, T.C.; Ijabadeniyi, O.A. Global and Regional Prevalence of Cronobacter sakazakii in Powdered Milk and Flour. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 6865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoque, A.; Ahmed, T.; Shahidullah, M.; Hossain, A.; Mannan, A.; Noor, K.; Nahar, K.; Ilias, M.; Ahmed, D. Isolation and Molecular Identification of Cronobacter spp. from Powdered Infant Formula (PIF) in Bangladesh. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2010, 142, 375–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fakruddin, M.; Rahaman, M.; Ahmed, M.M.; Hoque, M.M. Stress Tolerant Virulent Strains of Cronobacter sakazakii from Food. Biol. Res. 2014, 47, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyser, M.; Witthuhn, R.C.; Ronquest, L.-C.; Britz, T.J. Treatment of Winery Effluent with Upflow Anaerobic Sludge Blanket (UASB)—Granular Sludges Enriched with Enterobacter sakazakii. Biotechnol. Lett. 2003, 25, 1893–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehner, A.; Nitzsche, S.; Breeuwer, P.; Diep, B.; Thelen, K.; Stephan, R. Comparison of Two Chromogenic Media and Evaluation of Two Molecular Based Identification Systems for Enterobacter sakazakii Detection. BMC Microbiol. 2006, 6, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bankevich, A.; Nurk, S.; Antipov, D.; Gurevich, A.A.; Dvorkin, M.; Kulikov, A.S.; Lesin, V.M.; Nikolenko, S.I.; Pham, S.; Prjibelski, A.D.; et al. SPAdes: A New Genome Assembly Algorithm and Its Applications to Single-Cell Sequencing. J. Comput. Biol. 2012, 19, 455–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurevich, A.; Saveliev, V.; Vyahhi, N.; Tesler, G. QUAST: Quality Assessment Tool for Genome Assemblies. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 1072–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolley, K.A.; Bray, J.E.; Maiden, M.C.J. Open-Access Bacterial Population Genomics: BIGSdb Software, the PubMLST.Org Website and Their Applications. Wellcome Open Res. 2018, 3, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, M.V.; Cosentino, S.; Rasmussen, S.; Friis, C.; Hasman, H.; Marvig, R.L.; Jelsbak, L.; Sicheritz-Pontén, T.; Ussery, D.W.; Aarestrup, F.M.; et al. Multilocus Sequence Typing of Total-Genome-Sequenced Bacteria. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2012, 50, 1355–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolley, K.A.; Maiden, M.C. BIGSdb: Scalable Analysis of Bacterial Genome Variation at the Population Level. BMC Bioinform. 2010, 11, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogrodzki, P.; Forsythe, S. Capsular Profiling of the Cronobacter Genus and the Association of Specific Cronobacter sakazakii and C. malonaticus Capsule Types with Neonatal Meningitis and Necrotizing Enterocolitis. BMC Genom. 2015, 16, 758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, R.K.; Bartels, D.; Best, A.A.; DeJongh, M.; Disz, T.; Edwards, R.A.; Formsma, K.; Gerdes, S.; Glass, E.M.; Kubal, M.; et al. The RAST Server: Rapid Annotations Using Subsystems Technology. BMC Genom. 2008, 9, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seemann, T. Prokka: Rapid Prokaryotic Genome Annotation. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2068–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier-Kolthoff, J.P.; Göker, M. TYGS is an Automated High-Throughput Platform for State-of-the-Art Genome-Based Taxonomy. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefort, V.; Desper, R.; Gascuel, O. FastME 2.0: A Comprehensive, Accurate, and Fast Distance-Based Phylogeny Inference Program. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2015, 32, 2798–2800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alikhan, N.-F.; Petty, N.K.; Ben Zakour, N.L.; Beatson, S.A. BLAST Ring Image Generator (BRIG): Simple Prokaryote Genome Comparisons. BMC Genom. 2011, 12, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.; Zhang, Y.; Fan, G.; Sun, D.; Zhang, X.; Yu, Z.; Wang, J.; Wu, L.; Shi, W.; Ma, J. IPGA: A Handy Integrated Prokaryotes Genome and Pan-Genome Analysis Web Service. IMeta 2022, 1, e55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, A.J.; Cummins, C.A.; Hunt, M.; Wong, V.K.; Reuter, S.; Holden, M.T.G.; Fookes, M.; Falush, D.; Keane, J.A.; Parkhill, J. Roary: Rapid Large-Scale Prokaryote Pan Genome Analysis. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 3691–3693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, B.; Raphenya, A.R.; Alcock, B.; Waglechner, N.; Guo, P.; Tsang, K.K.; Lago, B.A.; Dave, B.M.; Pereira, S.; Sharma, A.N.; et al. CARD 2017: Expansion and Model-Centric Curation of the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, D566–D573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosentino, S.; Larsen, M.V.; Aarestrup, F.M.; Lund, O. PathogenFinder—Distinguishing Friend from Foe Using Bacterial Whole Genome Sequence Data. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e77302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zheng, D.; Liu, B.; Yang, J.; Jin, Q. VFDB 2016: Hierarchical and Refined Dataset for Big Data Analysis—10 Years On. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, D694–D697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carattoli, A.; Zankari, E.; García-Fernández, A.; Voldby Larsen, M.; Lund, O.; Villa, L.; Møller Aarestrup, F.; Hasman, H. In Silico Detection and Typing of Plasmids Using PlasmidFinder and Plasmid Multilocus Sequence Typing. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014, 58, 3895–3903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couvin, D.; Bernheim, A.; Toffano-Nioche, C.; Touchon, M.; Michalik, J.; Néron, B.; Rocha, E.P.C.; Vergnaud, G.; Gautheret, D.; Pourcel, C. CRISPRCasFinder, an Update of CRISRFinder, Includes a Portable Version, Enhanced Performance and Integrates Search for Cas Proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, W246–W251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wishart, D.S.; Han, S.; Saha, S.; Oler, E.; Peters, H.; Grant, J.R.; Stothard, P.; Gautam, V. PHASTEST: Faster than PHASTER, Better than PHAST. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, W443–W450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siguier, P.; Perochon, J.; Lestrade, L.; Mahillon, J.; Chandler, M. ISfinder: The Reference Centre for Bacterial Insertion Sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006, 34, D32–D36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blin, K.; Shaw, S.; Vader, L.; Szenei, J.; Reitz, Z.L.; Augustijn, H.E.; Cediel-Becerra, J.D.D.; de Crécy-Lagard, V.; Koetsier, R.A.; Williams, S.E.; et al. antiSMASH 8.0: Extended Gene Cluster Detection Capabilities and Analyses of Chemistry, Enzymology, and Regulation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, gkaf334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Enterobacter sakazakii Infections Associated with the Use of Powdered Infant Formula—Tennessee, 2001. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2002, 51, 297–300. [Google Scholar]

- Forsythe, S.J.; Dickins, B.; Jolley, K.A. Cronobacter, the Emergent Bacterial Pathogen Enterobacter sakazakii Comes of Age; MLST and Whole Genome Sequence Analysis. BMC Genom. 2014, 15, 1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iversen, C.; Forsythe, S. Isolation of Enterobacter sakazakii and Other Enterobacteriaceae from Powdered Infant Formula Milk and Related Products. Food Microbiol. 2004, 21, 771–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Q.Q.; Condell, O.; Power, K.; Butler, F.; Tall, B.D.; Fanning, S. Cronobacter Species (Formerly Known as Enterobacter sakazakii) in Powdered Infant Formula: A Review of Our Current Understanding of the Biology of This Bacterium. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2012, 113, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, E.; Rhee, M.S.; Gonçalves, M.P.M.B.B.; Sant’Ana, A.S. Desiccation Strategies of Cronobacter sakazakii to Survive in Low Moisture Foods and Environment. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 143, 104241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csorba, C.; Pajić, M.; Blagojević, B.; Forsythe, S.; Radinović, M.; Velebit, B. Prevalence, Characterization, and Antibiotic Susceptibility of Cronobacter spp. in a Milk Powder Processing Environment: The First Reported Case in Serbia. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 10, 554–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fei, P.; Jiang, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Yuan, X.; Yang, T.; Chen, J.; Wang, Z.; Kang, H.; Forsythe, S.J. Prevalence, Molecular Characterization, and Antibiotic Susceptibility of Cronobacter sakazakii Isolates from Powdered Infant Formula Collected from Chinese Retail Markets. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grim, C.J.; Gopinath, G.R.; Jarvis, K.G.; Sathyamoorthy, V.; Trach, L.H.; Chase, H.R.; Tall, B.D. Genome Sequence of Cronobacter sakazakii Serogroup O:4, Sequence Type 4 Strain CDC 2009-03746, Isolated from a Fatal Case of Infantile Meningitis. Genome Announc. 2015, 3, e00492-15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hariri, S.; Joseph, S.; Forsythe, S.J. Cronobacter sakazakii ST4 Strains and Neonatal Meningitis, United States. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2013, 19, 175–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chase, H.R.; Gopinath, G.R.; Eshwar, A.K.; Stoller, A.; Fricker-Feer, C.; Gangiredla, J.; Patel, I.R.; Cinar, H.N.; Jeong, H.; Lee, C.; et al. Comparative Genomic Characterization of the Highly Persistent and Potentially Virulent Cronobacter sakazakii ST83, CC65 Strain H322 and Other ST83 Strains. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Fu, S.; Song, D.; Qin, X.; Zhang, W.; Man, C.; Yang, X.; Jiang, Y. Identification, Typing and Drug Resistance of Cronobacter spp. in Powdered Infant Formula and Processing Environment. Foods 2023, 12, 1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison, G.E.; Verma, N.K. Serotype-Converting Bacteriophages and O-Antigen Modification in Shigella flexneri. Trends Microbiol. 2000, 8, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, S.L.; Wadhams, G.H.; Armitage, J.P. Signal Processing in Complex Chemotaxis Pathways. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2011, 9, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, P.; Jiang, Y.; Feng, J.; Forsythe, S.J.; Li, R.; Zhou, Y.; Man, C. Antibiotic and Desiccation Resistance of Cronobacter sakazakii and C. malonaticus Isolates from Powdered Infant Formula and Processing Environments. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilonzo-nthenge, A.; Rotich, E.; Godwin, S.; Nahashon, S.; Chen, F. Prevalence and Antimicrobial Resistance of Cronobacter sakazakii Isolated from Domestic Kitchens in Middle Tennessee, United States. J. Food Prot. 2012, 75, 1512–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakbin, B.; Brück, W.M.; Allahyari, S.; Rossen, J.W.A.; Mahmoudi, R. Antibiotic Resistance and Molecular Characterization of Cronobacter sakazakii Strains Isolated from Powdered Infant Formula Milk. Foods 2022, 11, 1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holý, O.; Parra-Flores, J.; Lepuschitz, S.; Alarcón-Lavín, M.P.; Cruz-Córdova, A.; Xicohtencatl-Cortes, J.; Mancilla-Rojano, J.; Ruppitsch, W.; Forsythe, S. Molecular Characterization of Cronobacter sakazakii Strains Isolated from Powdered Milk. Foods 2021, 10, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aly, M.A.; Domig, K.J.; Kneifel, W.; Reimhult, E. Whole Genome Sequencing-Based Comparison of Food Isolates of Cronobacter sakazakii. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parra-Flores, J.; Holý, O.; Riffo, F.; Lepuschitz, S.; Maury-Sintjago, E.; Rodríguez-Fernández, A.; Cruz-Córdova, A.; Xicohtencatl-Cortes, J.; Mancilla-Rojano, J.; Troncoso, M.; et al. Profiling the Virulence and Antibiotic Resistance Genes of Cronobacter sakazakii Strains Isolated from Powdered and Dairy Formulas by Whole-Genome Sequencing. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 694922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holý, O.; Parra-Flores, J.; Bzdil, J.; Cabal-Rosel, A.; Daza-Prieto, B.; Cruz-Córdova, A.; Xicohtencatl-Cortes, J.; Rodríguez-Martínez, R.; Acuña, S.; Forsythe, S.; et al. Screening of Antibiotic and Virulence Genes from Whole Genome Sequenced Cronobacter sakazakii Isolated from Food and Milk-Producing Environments. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chon, J.-W.; Song, K.-Y.; Kim, S.-Y.; Hyeon, J.-Y.; Seo, K.-H. Isolation and Characterization of Cronobacter from Desiccated Foods in Korea. J. Food Sci. 2012, 77, M354–M358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Jang, S.S.; Kim, S.K.; Park, J.-H.; Heu, S.; Ryu, S. Prevalence and Genetic Diversity of Enterobacter sakazakii in Ingredients of Infant Foods. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2008, 122, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, K.L.; Jarocki, V.M.; Charles, I.G.; Djordjevic, S.P. The Diverse Functional Roles of Elongation Factor Tu (EF-Tu) in Microbial Pathogenesis. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holý, O.; Alsonosi, A.; Hochel, I.; Röderová, M.; Zatloukalová, S.; Mlynárčik, P.; Kolář, M.; Petrželová, J.; Alazraq, A.; Chmelař, D.; et al. Antibiotic Susceptibility of Cronobacter spp. Isolated from Clinical Samples. Pol. J. Microbiol. 2019, 68, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zurfluh, K.; Nüesch-Inderbinen, M.; Morach, M.; Zihler Berner, A.; Hächler, H.; Stephan, R. Extended-Spectrum-β-Lactamase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae Isolated from Vegetables Imported from the Dominican Republic, India, Thailand, and Vietnam. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2015, 81, 3115–3120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.; Gopinath, G.R.; Eshwar, A.; Srikumar, S.; Nguyen, S.; Gangiredla, J.; Patel, I.R.; Finkelstein, S.B.; Negrete, F.; Woo, J.; et al. The Secretion of Toxins and Other Exoproteins of Cronobacter: Role in Virulence, Adaption, and Persistence. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, A.A.; Hu, L.; Grim, C.J.; Gopinath, G.; Sathyamoorthy, V.; Jarvis, K.G.; Lee, C.; Sadowski, J.; Kim, J.; Kothary, M.H.; et al. Characterization of Putative Virulence Genes on the Related RepFIB Plasmids Harbored by Cronobacter spp. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 3255–3267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, I.-C.; Wu, H.-H.; Chen, Z.-W.; Chou, C.-H. Prevalence of IncFIB Plasmids Found among Salmonella enterica Serovar Schwarzengrund Isolates from Animal Sources in Taiwan Using Whole-Genome Sequencing. Pathogens 2021, 10, 1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucerova, E.; Clifton, S.W.; Xia, X.-Q.; Long, F.; Porwollik, S.; Fulton, L.; Fronick, C.; Minx, P.; Kyung, K.; Warren, W.; et al. Genome Sequence of Cronobacter sakazakii BAA-894 and Comparative Genomic Hybridization Analysis with Other Cronobacter Species. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e9556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Bu, K.; Yang, H.; Li, P.; He, Z.; Wu, T.; Li, X.; Nong, H.; Wu, S.; Qin, J.; et al. Genomic Profiling and Virulence Characterization of Cronobacter sakazakii Strains Isolated from Powdered Spices and Instant Cereals in Nanning, China. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrez Lamberti, M.F.; Terán, L.C.; Lopez, F.E.; de las Mercedes Pescaretti, M.; Delgado, M.A. Genomic and Proteomic Characterization of Two Strains of Shigella Flexneri 2 Isolated from Infants’ Stool Samples in Argentina. BMC Genom. 2022, 23, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, H.; Chase, H.R.; Gangiredla, J.; Grim, C.J.; Patel, I.R.; Kothary, M.H.; Jackson, S.A.; Mammel, M.K.; Carter, L.; Negrete, F.; et al. Analysis of the Molecular Diversity Among Cronobacter Species Isolated from Filth Flies Using Targeted PCR, Pan Genomic DNA Microarray, and Whole Genome Sequencing Analyses. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 561204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.; Xie, Z.; Yang, J.; Yang, R.; Li, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, Q.; Chen, J.; Alwathnani, H.A.; et al. Citrobacter portucalensis Sb-2 Contains a Metalloid Resistance Determinant Transmitted by Citrobacter Phage Chris1. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 443, 130184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Fang, L.; Tan, S.; Yu, M.; Li, X.; He, S.; Wei, Y.; Li, G.; Jiang, J.; Wu, M. Type I CRISPR-Cas Targets Endogenous Genes and Regulates Virulence to Evade Mammalian Host Immunity. Cell Res. 2016, 26, 1273–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makarova, K.S.; Wolf, Y.I.; Alkhnbashi, O.S.; Costa, F.; Shah, S.A.; Saunders, S.J.; Barrangou, R.; Brouns, S.J.J.; Charpentier, E.; Haft, D.H.; et al. An Updated Evolutionary Classification of CRISPR–Cas Systems. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2015, 13, 722–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogrodzki, P.; Forsythe, S.J. CRISPR–Cas Loci Profiling of Cronobacter sakazakii Pathovars. Future Microbiol. 2016, 11, 1507–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogrodzki, P.; Forsythe, S.J. DNA-Sequence Based Typing of the Cronobacter Genus Using MLST, CRISPR-Cas Array and Capsular Profiling. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.; Zhang, J.; Li, C.; Xie, T.; Ling, N.; Wu, Q.; Ye, Y. The Driving Force of Prophages and CRISPR-Cas System in the Evolution of Cronobacter sakazakii. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 40206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Feature | Details | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Isolate ID | S44_RUTF | S41_PIFM | S43_TF |

| Sample source | Ready-to-use therapeutic food | Powdered infant formula milk | Therapeutic food |

| Year of isolation | 2024 | 2024 | 2024 |

| Genome length (bp) | 4,366,115 | 4,371,145 | 4,444,405 |

| No. of contigs | 106 | 153 | 38 |

| GC content (%) | 56.98 | 56.97 | 56.84 |

| N50 (bp) | 86,185 | 60,688 | 272,134 |

| L50 | 17 | 23 | 5 |

| Coverage (X) | 23.22 | 19.39 | 123.1 |

| NCBI accession | NZ_JBNUPD000000000 | NZ_JBNPBD000000000 | NZ_JBNUPC000000000 |

| Feature | Details | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Isolate ID | S44_RUTF | S41_PIFM | S43_TF |

| CDS | 4037 | 4066 | 4076 |

| Partial CDS | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| rRNA | 3 | 5 | 3 |

| tRNA | 62 | 64 | 68 |

| tmRNA | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Miscellaneous RNA | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Repeat Regions | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Subsystems | 351 | 351 | 350 |

| Hypothetical proteins | 629 | 642 | 700 |

| Proteins with functional assignments | 3658 | 3713 | 3596 |

| Proteins with EC number assignments | 1140 | 1157 | 1135 |

| Proteins with GO assignments | 929 | 944 | 928 |

| Proteins with Pathway assignments | 807 | 820 | 805 |

| Isolate ID | Sequence Type | Locus | Identity | Coverage | Alignment Length | Allele Length | Gaps | Allele |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S44_RUTF and S41_PIFM | ST83 | atpD | 100 | 100 | 390 | 390 | 0 | atpD_19 |

| fusA | 100 | 100 | 438 | 438 | 0 | fusA_16 | ||

| glnS | 100 | 100 | 363 | 363 | 0 | glnS_19 | ||

| gltB | 100 | 100 | 507 | 507 | 0 | gltB_41 | ||

| gyrB | 100 | 100 | 402 | 402 | 0 | gyrB_19 | ||

| infB | 100 | 100 | 441 | 441 | 0 | infB_15 | ||

| pps | 100 | 100 | 495 | 495 | 0 | pps_23 | ||

| S43_TF | ST789 | atpD | 100 | 100 | 390 | 390 | 0 | atpD_15 |

| fusA | 100 | 100 | 438 | 438 | 0 | fusA_14 | ||

| glnS | 100 | 100 | 363 | 363 | 0 | glnS_15 | ||

| gltB | 100 | 100 | 507 | 507 | 0 | gltB_13 | ||

| gyrB | 100 | 100 | 402 | 402 | 0 | gyrB_22 | ||

| infB | 100 | 100 | 441 | 441 | 0 | infB_5 | ||

| pps | 100 | 100 | 495 | 495 | 0 | pps_347 |

| Isolate ID | Assembly Accession | No. of Core Gene | No. of Accessory Genes | No. of Unique Genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cronobacter sakazakii ATCC BAA_894 | GCA_000017665.1 | 3317 | 749 | 86 |

| Cronobacter sakazakii ES15 | GCA_000263215.1 | 3317 | 527 | 44 |

| Cronobacter sakazakii SP291 | GCA_000339015.1 | 3317 | 735 | 95 |

| Cronobacter sakazakii CMCC 45402 | GCA_000504545.1 | 3317 | 626 | 270 |

| Cronobacter sakazakii CS_931 | GCA_003516125.3 | 3317 | 652 | 96 |

| Cronobacter sakazakii GZcsf_1 | GCA_003955925.1 | 3317 | 725 | 476 |

| Cronobacter sakazakii CFSAN068773 | GCA_009648895.1 | 3317 | 760 | 95 |

| Cronobacter sakazakii 5563_17 | GCA_013425995.1 | 3317 | 525 | 49 |

| Cronobacter sakazakii C767 | GCA_018884085.1 | 3317 | 896 | 0 |

| Cronobacter sakazakii C79 | GCA_018884105.1 | 3317 | 668 | 138 |

| Cronobacter sakazakii C105731 | GCA_018884125.1 | 3317 | 651 | 96 |

| Cronobacter sakazakii C757 | GCA_018884145.1 | 3317 | 896 | 5 |

| Cronobacter sakazakii G4023 | GCA_020869275.1 | 3317 | 855 | 280 |

| Cronobacter sakazakii 70402496 | GCA_022648965.1 | 3317 | 697 | 99 |

| Cronobacter sakazakii JXES_28 | GCA_023805435.1 | 3317 | 657 | 84 |

| Cronobacter sakazakii USDA_ARS_USMARC_54664 | GCA_025200595.1 | 3317 | 571 | 60 |

| Cronobacter sakazakii Crono_589 | GCA_025345525.1 | 3317 | 642 | 166 |

| Cronobacter sakazakii Crono_684 | GCA_025345545.1 | 3317 | 735 | 146 |

| Cronobacter sakazakii S41_PIFM | GCF_050311875.1 | 3317 | 720 | 20 |

| Cronobacter sakazakii S43_TF | GCF_050409185.1 | 3317 | 656 | 84 |

| Cronobacter sakazakii S44_RUTF | GCF_050409205.1 | 3317 | 716 | 9 |

| Isolate ID | Gene | Function |

|---|---|---|

| S44_RUTF | astE | Succinylglutamate desuccinylase |

| curA | NADPH-dependent curcumin reductase | |

| nasR | Nitrate regulatory protein | |

| S41_PIFM | fdhF_5 | Formate dehydrogenase H |

| pepP | Xaa-Pro aminopeptidase | |

| S43_TF | aplIM | Modification methylase AplI |

| hin | DNA-invertase hin | |

| jefA | Drug efflux pump JefA | |

| xerC_4 | Tyrosine recombinase XerC |

| Antibiotic Resistance Ontology (ARO) Term | SNP | Drug Class | Resistance Mechanism | S44_RUTF | S41_PIFM | S43_TF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| acrA | Fluoroquinolone antibiotic, cephalosporin, glycylcycline, penicillin beta-lactam, tetracycline antibiotic, rifamycin antibiotic, phenicol antibiotic, disinfecting agents, and antiseptics | Antibiotic efflux | + | + | + | |

| adeF | Fluoroquinolone antibiotic, tetracycline antibiotic | Antibiotic efflux | + | + | + | |

| cRP | Macrolide antibiotic, fluoroquinolone antibiotic, penicillin beta-lactam | Antibiotic efflux | + | + | + | |

| emrB | Fluoroquinolone antibiotic | Antibiotic efflux | + | + | + | |

| emrR | Fluoroquinolone antibiotic | Antibiotic efflux | + | + | + | |

| H-NS | Macrolide antibiotic, fluoroquinolone antibiotic, cephalosporin, penicillin beta-lactam, tetracycline antibiotic | Antibiotic efflux | + | + | + | |

| kpnE | Macrolide antibiotic, aminoglycoside antibiotic, cephalosporin, tetracycline antibiotic, peptide antibiotic, rifamycin antibiotic, disinfecting agents, and antiseptics | Antibiotic efflux | + | + | + | |

| kpnF | Macrolide antibiotic, aminoglycoside antibiotic, cephalosporin, tetracycline antibiotic, peptide antibiotic, rifamycin antibiotic, disinfecting agents, and antiseptics | Antibiotic efflux | + | + | + | |

| msbA | Nitroimidazole antibiotic | Antibiotic efflux | + | + | + | |

| qacG | Disinfecting agents and antiseptics | Antibiotic efflux | − | − | + | |

| qacJ | Disinfecting agents and antiseptics | Antibiotic efflux | + | + | − | |

| rsmA | Fluoroquinolone antibiotic, diaminopyrimidine antibiotic, phenicol antibiotic | Antibiotic efflux | + | + | + | |

| marA | Fluoroquinolone antibiotic, monobactam, carbapenem, cephalosporin, glycylcycline, penicillin beta-lactam, tetracycline antibiotic, rifamycin antibiotic, phenicol antibiotic, disinfecting agents, and antiseptics | Antibiotic efflux, reduced permeability to antibiotics | + | + | + | |

| csa1 | Cephalosporin | Antibiotic inactivation | + | + | − | |

| fosA8 | Phosphonic acid antibiotic | Antibiotic inactivation | + | + | + | |

| vanG | Glycopeptide antibiotic | Antibiotic target alteration | + | + | + | |

| eF-Tu | R234F | Elfamycin antibiotic | Antibiotic target alteration | + | + | + |

| pbp3 | D350N, S357N | Penicillin-binding protein mutations conferring resistance to beta-lactam antibiotics | Antibiotic target alteration | + | + | + |

| acrAB-tolC with marR mutations | S3N | Fluoroquinolone antibiotic, cephalosporin, glycylcycline, penicillin beta-lactam, tetracycline antibiotic, rifamycin antibiotic, phenicol antibiotic, disinfecting agents, and antiseptics | Antibiotic target alteration, antibiotic efflux | + | + | + |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bhowmik, S.; Rivu, S.; Bari, M.L.; Ahmed, S. Genome Mining of Cronobacter sakazakii in Bangladesh Reveals the Occurrence of High-Risk ST83 and Rare ST789 Lineages. Pathogens 2025, 14, 1220. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121220

Bhowmik S, Rivu S, Bari ML, Ahmed S. Genome Mining of Cronobacter sakazakii in Bangladesh Reveals the Occurrence of High-Risk ST83 and Rare ST789 Lineages. Pathogens. 2025; 14(12):1220. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121220

Chicago/Turabian StyleBhowmik, Sutapa, Supantha Rivu, Md. Latiful Bari, and Sangita Ahmed. 2025. "Genome Mining of Cronobacter sakazakii in Bangladesh Reveals the Occurrence of High-Risk ST83 and Rare ST789 Lineages" Pathogens 14, no. 12: 1220. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121220

APA StyleBhowmik, S., Rivu, S., Bari, M. L., & Ahmed, S. (2025). Genome Mining of Cronobacter sakazakii in Bangladesh Reveals the Occurrence of High-Risk ST83 and Rare ST789 Lineages. Pathogens, 14(12), 1220. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121220