Seroprevalence of Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever and Rift Valley Fever Viruses Among Ruminants in Nigeria: A Descriptive Epizootiological Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

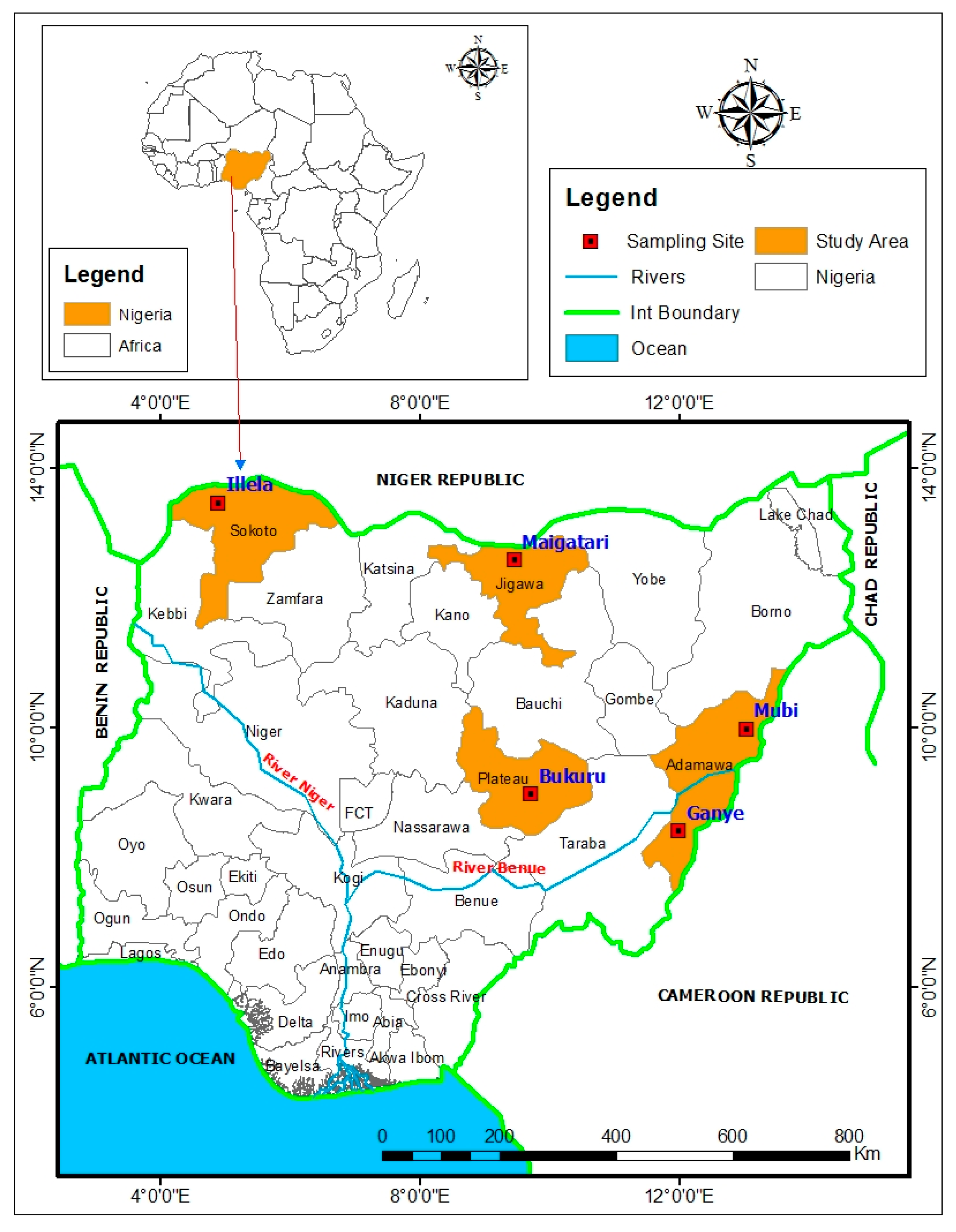

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Study Population and Data Collection

2.3. Sample Collection

2.4. Serological Analysis

2.5. Variable Definition and Coding

2.6. Data Management and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Study Animals

3.2. Serological Prevalence of CCHFV in Ruminants at Nigerian Livestock Markets

3.3. Serological Prevalence of RVFV in Ruminants in Nigerian Livestock Markets

3.4. Seroprevalence of Combined CCHFV and RVFV Antibodies in Ruminants in Nigerian Livestock Markets

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ergönül, Ö. Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2006, 6, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bente, D.A.; Forrester, N.L.; Watts, D.M.; McAuley, A.J.; Whitehouse, C.A.; Bray, M. Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever: History, epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical syndrome and genetic diversity. Antivir. Res. 2013, 100, 159–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirmak, T.; Tulek, N.; Bulut, C. Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever: Transmission to visitors and healthcare workers. Infection 2016, 44, 687–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazlalipour, M.; Jalali, T.; Hewson, R.; Pouriayevali, M.H.; Salehi-Vaziri, M. Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever among healthcare workers in Iran 2000–2023, a report of National Reference Laboratory. BMC Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, 1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, M.G.; Weaver, G.; Raabe, V. State of the Clinical Science Working Group of the National Emerging Pathogens Training Educational Center’s Special Pathogens Research Network. Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever Virus for Clinicians—Diagnosis, Clinical Management, and Therapeutics. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2024, 30, 864–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepin, M.; Bouloy, M.; Bird, B.H.; Kemp, A.; Paweska, J. Rift Valley fever virus (Bunyaviridae: Phlebovirus): An update on pathogenesis, molecular epidemiology, vectors, diagnostics and prevention. Vet. Res. 2010, 41, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwaśnik, M.; Rożek, W.; Rola, J. Rift Valley Fever—A Growing Threat to Humans and Animals. J. Vet. Res. 2021, 65, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balkhy, H.H.; Memish, Z.A. Rift Valley fever: An uninvited zoonosis in the Arabian peninsula. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2003, 21, 153–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikegami, T.; Makino, S. The pathogenesis of Rift Valley fever. Viruses 2011, 3, 493–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, D.; Kortekaas, J.; Bowden, T.A.; Warimwe, G.M. Rift Valley fever: Biology and epidemiology. J. Gen. Virol. 2019, 100, 1187–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Crimean-Congo Haemorrhagic Fever and Rift Valley Fever Fact Sheets; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; Available online: https://www.who.int (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- FAO. The Future of Livestock in Nigeria. Opportunities and Challenges in the Face of Uncertainty; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2019; Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/ (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- National Bureau of Statistics (NBS). National Agricultural Sample Census 2022/2023; National Bureau of Statistics: Abuja, Nigeria, 2024. Available online: https://microdata.nigerianstat.gov.ng/index.php/home (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Aminu, N.; Aminu, N.; Muhammad, S.S.; Idris, A.A. Population distribution of cattle, sheep and goat in Nigeria. Niger. J. Anim. Prod. 2024, 51, 874–877. [Google Scholar]

- Valerio, V.C.; Walther, O.J.; Eilittä, M.; Cissé, B.; Muneepeerakul, R.; Kiker, G.A. Network analysis of regional livestock trade in West Africa. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0232681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oluwayelu, D.; Afrough, B.; Adebiyi, A.; Varghese, A.; Eun-Sil, P.; Fukushi, S.; Yoshikawa, T.; Saijo, M.; Neumann, E.; Morikawa, S.; et al. Prevalence of Antibodies to Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever Virus in Ruminants, Nigeria, 2015. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020, 26, 744–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzikwi-Emennaa, A.A.; Meseko, C.; Emennaa, P.; Adeyinka, A.J.; Adamu, A.M.; Adegboye, O.A. Detection of Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever Virus Antibodies in Cattle in Plateau State, Nigeria. Viruses 2022, 14, 2618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igah, O.E.; Natala, A.J.; Kabir, J.; Ogo, N.I.; Chinyere, C.; Shittu, I.; Meseko, C.A. Detection of Crimean-Congo Haemorrhagic Fever Virus Circulating in Ticks and Cattle in Plateau and Kaduna States, Nigeria. Sokoto J. Vet. Sci. 2024, 22, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinonyerem, C.; Shittu, I.; Ogo, N.; Adedeji, A.; Sada, A.; Columba, V.; Ularamu, H.; Nwosuh, C.; Meseko, C. Further evidence of antibodies against Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever virus in different livestock species in Nigeria. J. Immunoass. Immunochem. 2025, 46, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umoh, J.U.; Ezeokoli, C.D.; Ogwu, D. Prevalence of antibodies to Crimean-haemorrhagic fever-Congo virus in cattle in northern Nigeria. Int. J. Zoonoses 1983, 10, 151–154. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Daodu, O.B.; Hartlaub, J.; Olopade, J.O.; Oluwayelu, D.O.; Groschup, M.H. Serological evidence of tick-borne Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever and Dugbe orthonairovirus infections in cattle in Kwara State in northern Nigeria indicate independent endemics. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2024, 18, e0012539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olaleye, O.D.; Tomori, O.; Schmitz, H. Rift Valley fever in Nigeria: Infections in domestic animals. Rev. Sci. Tech. Off. Int. Epiz. 1996, 15, 937–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anejo-Okopi, J.; Arthur, O.O.; Okojokwu, O.J.; Joseph, S.; Chibueze, G.; Adetunji, J.; Okwori, J.A.; Amanyi, D.O.; Ujah, O.I.; Audu, O. Seroprevalence of rift valley fever virus infection among slaughtered ruminants in Jos, North-Central, Nigeria. Hosts Viruses 2020, 7, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atuman, Y.J.; Kudi, C.A.; Abdu, P.A.; Okubanjo, O.O.; Wungak, Y.; Ularamu, H.G.; Abubakar, A. Serological Evidence of Antibodies to Rift Valley Fever Virus in Wild and Domestic Animals in Bauchi State, Nigeria. Vet. Med. Int. 2022, 2022, 6559193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhaji, N.B.; Aminu, J.; Lawan, M.K.; Babalobi, O.O.; Ghali-Mohammed, I.; Odetokun, I.A. Seropositivity and Associated Intrinsic and Extrinsic Factors for Rift Valley Fever Virus Occurrence in Pastoral Herds of Nigeria: A Cross-Sectional Survey. BMC Vet. Res. 2020, 16, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oragwa, A.; Obishakin, E.; Oluwayelu, D. Molecular Detection and Characterization of Rift Valley Fever Virus in Humans and Domestic Ruminants in Nigeria. Microbe 2023, 1, 100016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamu, A.M.; Enem, S.I.; Ngbede, E.O.; Owolodun, O.A.; Dzikwi, A.A.; Ajagbe, O.A.; Datong, D.D.; Bello, G.S.; Kore, M.; Yikawe, S.S.; et al. Serosurvey on Sheep Unravel Circulation of Rift Valley Fever Virus in Nigeria. EcoHealth 2020, 17, 393–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinto, B.; Quellec, J.; Cêtre-Sossah, C.; Dicko, A.; Salinas, S.; Simonin, Y. Rift Valley fever in West Africa: A zoonotic disease with multiple socio-economic consequences. One Health 2023, 17, 100583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oragwa, A.O.; Obishakin, E.T.; Oluwayelu, D.O. Molecular Detection and Characterization of Rift Valley Fever Virus in Arthropod Vectors in Nigeria. Microbe 2024, 5, 100198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 15; StataCorp LLC: College Station, TX, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- El Ghassem, A.; Apolloni, A.; Vial, L.; Bouvier, R.; Bernard, C.; Khayar, M.S.; Ahmed, M.C.; Fausther-Bovendo, H.; Beyit, A.D.; Yahya, B.; et al. Risk factors associated with Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus circulation among humans, livestock, and ticks in Mauritania through a One Health retrospective study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2023, 23, 764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, J.; Secka, A.; McVey, D.S.; Dodd, K.A.; Faburay, B. Serological Prevalence of Crimean–Congo Hemorrhagic Fever Virus Infection in Small Ruminants and Cattle in The Gambia. Pathogens 2023, 12, 749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasparine, M.; Namekong Fokeng, A.; Lopez, E.; Mvodo, S.; Thirion, L.; Paguem, A.; Charrel, R.; de Lamballerie, X.; Falchi, A. First report of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus exposure in human and livestock populations, Center Region, Cameroon. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2025, 15, 1578518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukhaye, E.; Akoko, J.M.; Nyamota, R.; Mwatondo, A.; Muturi, M.; Nthiwa, D.; Kirwa, L.J.; Bargul, J.L.; Abkallo, H.M.; Bett, B. Exposure patterns and the risk factors of Crimean Congo hemorrhagic fever virus amongst humans, livestock and selected wild animals at the human/livestock/wildlife interface in Isiolo County, upper eastern Kenya. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2024, 18, e0012083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, E.C.; de Glanville, W.; Kibona, T.; Mmbaga, B.T.; Rostal, M.K.; Swai, E.S.; Cleaveland, S.; Lankester, F.; Willett, B.J.; Allan, K.J. Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus seroprevalence in human and livestock populations, Northern Tanzania. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2024, 30, 836–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adam, I.A.; Mahmoud, M.A.; Aradaib, I.E. A seroepidemiological survey of Crimean Congo hemorrhagic fever among cattle in North Kordufan State, Sudan. Virol. J. 2013, 10, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omoga, D.C.A.; Tchouassi, D.P.; Venter, M.; Ogola, E.O.; Osalla, J.; Kopp, A.; Slothouwer, I.; Torto, B.; Junglen, S.; Sang, R. Transmission Dynamics of Crimean–Congo Haemorrhagic Fever Virus (CCHFV): Evidence of Circulation in Humans, Livestock, and Rodents in Diverse Ecologies in Kenya. Viruses 2023, 15, 1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zouaghi, K.; Bouattour, A.; Aounallah, H.; Surtees, R.; Krause, E.; Michel, J.; Mamlouk, A.; Nitsche, A.; M’ghirbi, Y. First Serological Evidence of Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever Virus and Rift Valley Fever Virus in Ruminants in Tunisia. Pathogens 2021, 10, 769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gahn, M.C.B.; Diouf, G.; Cissé, N.; Ciss, M.; Bordier, M.; Ndiaye, M.; Bakhoum, M.T.; Djiba, M.L.; Brown, C.; Faburay, B.; et al. Large-Scale Serological Survey of Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever Virus and Rift Valley Fever Virus in Small Ruminants in Senegal. Pathogens 2024, 13, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebogo-Belobo, J.T.; Sadeuh-Mba, S.A.; Mveng-Sanding, G.M.A.; Chavely, G.M.; Groschup, M.H.; Mbacham, W.F.; Njouom, R. Serological evidence of the circulation of the Rift Valley fever virus in sheep and goats slaughtered in Yaoundé, Cameroon. Vet. Med. Sci. 2022, 8, 2114–2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Situma, S.; Omondi, E.; Nyakarahuka, L.; Odinoh, R.; Mweu, M.; Mureithi, M.W.; Mulinge, M.M.; Clancey, E.; Dawa, J.; Ngere, I.; et al. Serological Evidence of Cryptic Rift Valley Fever Virus Transmission Among Humans and Livestock in Central Highlands of Kenya. Viruses 2024, 16, 1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anyangu, A.S.; Gould, L.H.; Sharif, S.K.; Nguku, P.M.; Omolo, J.O.; Mutonga, D.; Rao, C.Y.; Lederman, E.R.; Schnabel, D.; Paweska, J.T.; et al. Risk Factors for Severe Rift Valley Fever Infection in Kenya, 2007. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2010, 83, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, M.; Mosha, F.; Mghamba, J.; Zaki, S.R.; Shieh, W.J.; Paweska, J.; Omulo, S.; Gikundi, S.; Mmbuji, P.; Bloland, P.; et al. Epidemiologic and Clinical Aspects of a Rift Valley Fever Outbreak in Humans in Tanzania, 2007. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2010, 83, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.A.M.; Asmah, R.; Awuni, J.A.; Tasiame, W.; Mensah, G.I.; Paweska, J.T.; Weyer, J.; Hellferscee, O.; Thompson, P.N. Evidence of Rift Valley fever virus circulation in livestock and herders in Southern Ghana. Viruses 2023, 15, 1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sado, F.Y.; Tchetgna, H.S.; Kamgang, B.; Djonabaye, D.; Nakouné, E.; McCall, P.J.; Ndip, N.R.; Wondji, C.S. Seroprevalence of Rift Valley fever virus in domestic ruminants of various origins in two markets of Yaoundé, Cameroon. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2022, 16, e0010683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadja, M.C.; Hamidou Ibrahim, K.; Onidje, E.; Sourokou Sabi, S.; Yahaya Mahamane, A.; Gagara, H.; Emikpe, B.O.; Bada Alambedji, R. Seroprevalence of Rift Valley fever virus antibodies in domestic livestock in the Tahoua Region of Niger. Vet. Ital. 2025, 61, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Category | Number | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Species | Bovine | 1150 | 33.3 |

| Caprine | 1150 | 33.3 | |

| Ovine | 1150 | 33.3 | |

| Location | Bukuru livestock market | 689 | 20 |

| Ganye livestock market | 690 | 20 | |

| Illela livestock market | 690 | 20 | |

| Maigatari livestock market | 676 | 19.6 | |

| Mubi livestock market | 705 | 20.4 | |

| Age | Young | 485 | 14.1 |

| Old | 2963 | 85.9 | |

| Sex | Female | 2208 | 64 |

| Male | 1196 | 34.7 | |

| Missing/Not recorded | 46 | 1.3 | |

| Origin | Local | 2410 | 69.9 |

| Foreign | 1012 | 29.3 | |

| Missing/Not recorded | 28 | 0.8 | |

| Tick | No | 2953 | 85.6 |

| Yes | 449 | 13 | |

| Missing/Not recorded | 48 | 1.4 |

| Variable | Total Samples | Total Positive (%) | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall seroprevalence | 3450 | 936 (27.1) | 25.6–28.6 |

| Species | |||

| Cattle | 1150 | 637 (55.4) | 52.5–58.1 |

| Sheep | 1150 | 200 (17.4) | 15.3–19.7 |

| Goats | 1150 | 99 (8.6) | 7.1–10.3 |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 2202 | 670 (30.4) | 28.5–32.4 |

| Male | 1188 | 257 (21.6) | 19.4–24.1 |

| Age | |||

| Adult | 2951 | 813 (27.6) | 26.0–29.2 |

| Young | 482 | 123 (25.5) | 21.8–29.6 |

| Market location | |||

| Illela | 690 | 188 (27.2) | 24.1–30.7 |

| Maigatari | 679 | 164 (24.3) | 21.2–27.6 |

| Mubi | 705 | 250 (35.5) | 32.2–39.1 |

| Ganye | 680 | 164 (24.1) | 21.0–27.5 |

| Bukuru | 684 | 170 (24.9) | 21.8–28.2 |

| Origin of animals | |||

| Local | 1012 | 297 (29.3) | 26.6–32.2 |

| Foreign | 2395 | 628 (26.2) | 24.5–28.0 |

| Presence of ticks | |||

| Yes | 449 | 180 (40.1) | 35.6–44.7 |

| No | 2938 | 740 (25.2) | 23.6–26.8 |

| Variable | Total Samples | Total Positive (%) | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall seroprevalence | 3450 | 201 (5.8) | 5.1–6.7 |

| Species | |||

| Cattle | 1150 | 129 (11.2) | 9.5–13.2 |

| Sheep | 1150 | 33 (2.9) | 2.0–4.0 |

| Goats | 1150 | 39 (3.4) | 2.5–4.6 |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 2208 | 148 (6.7) | 5.7–7.8 |

| Male | 1196 | 47 (3.9) | 3.0–5.2 |

| Age | |||

| Adult | 2963 | 171 (5.8) | 5.0–6.7 |

| Young | 485 | 30 (6.2) | 4.4–8.7 |

| Market location | |||

| Illela | 690 | 77 (11.2) | 9.0–13.7 |

| Maigatari | 676 | 50 (7.4) | 5.6–9.6 |

| Mubi | 705 | 28 (4.0) | 2.8–5.7 |

| Ganye | 690 | 35 (5.1) | 3.7–7.0 |

| Bukuru | 689 | 11 (1.6) | 0.9–2.9 |

| Origin of animals | |||

| Local | 1012 | 107 (10.6) | 8.8–12.6 |

| Foreign | 2410 | 91 (3.8) | 3.1–4.6 |

| Presence of ticks | |||

| Yes | 449 | 54 (12.0) | 9.3–15.4 |

| No | 2953 | 144 (4.9) | 4.2–5.7 |

| Variable | Total Samples | Total Positive (%) | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cattle | 1150 | 94 (8.2) | 6.6–9.8 |

| Sheep | 1150 | 8 (0.7) | 0.22–1.18 |

| Goats | 1150 | 2 (0.2) | 0–0.46 |

| Total | 3450 | 104 (3.0) | 2.4–3.6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ehizibolo, D.O.; Oyekan, O.; Mkpuma, N.; Gado, D.A.; Turaki, I.Z.; Haliru, H.; Garba, I.; Williams, E.E.; Kennedy, S.; Abdullahi, A.; et al. Seroprevalence of Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever and Rift Valley Fever Viruses Among Ruminants in Nigeria: A Descriptive Epizootiological Analysis. Pathogens 2025, 14, 1219. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121219

Ehizibolo DO, Oyekan O, Mkpuma N, Gado DA, Turaki IZ, Haliru H, Garba I, Williams EE, Kennedy S, Abdullahi A, et al. Seroprevalence of Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever and Rift Valley Fever Viruses Among Ruminants in Nigeria: A Descriptive Epizootiological Analysis. Pathogens. 2025; 14(12):1219. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121219

Chicago/Turabian StyleEhizibolo, David Odion, Olumuyiwa Oyekan, Nicodemus Mkpuma, Dorcas Amara Gado, Isa Zayyad Turaki, Habibu Haliru, Ibrahim Garba, Elizabeth Ene Williams, Samdi Kennedy, Ardo Abdullahi, and et al. 2025. "Seroprevalence of Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever and Rift Valley Fever Viruses Among Ruminants in Nigeria: A Descriptive Epizootiological Analysis" Pathogens 14, no. 12: 1219. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121219

APA StyleEhizibolo, D. O., Oyekan, O., Mkpuma, N., Gado, D. A., Turaki, I. Z., Haliru, H., Garba, I., Williams, E. E., Kennedy, S., Abdullahi, A., Akawu, B., Dogonyaro, B. B., Shallangwa, J. M., Kilyobas, C. S., Gregory, I., Auta, N., Kussiy, M. H., Mohammed, A., Muhammad, M. A., ... Faburay, B. (2025). Seroprevalence of Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever and Rift Valley Fever Viruses Among Ruminants in Nigeria: A Descriptive Epizootiological Analysis. Pathogens, 14(12), 1219. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121219