Identification of Potential Vectors and Species Density of Tsetse Fly, Prevalence, and Genetic Diversity of Drug-Resistant Trypanosomes in Kenya

Abstract

1. Introduction

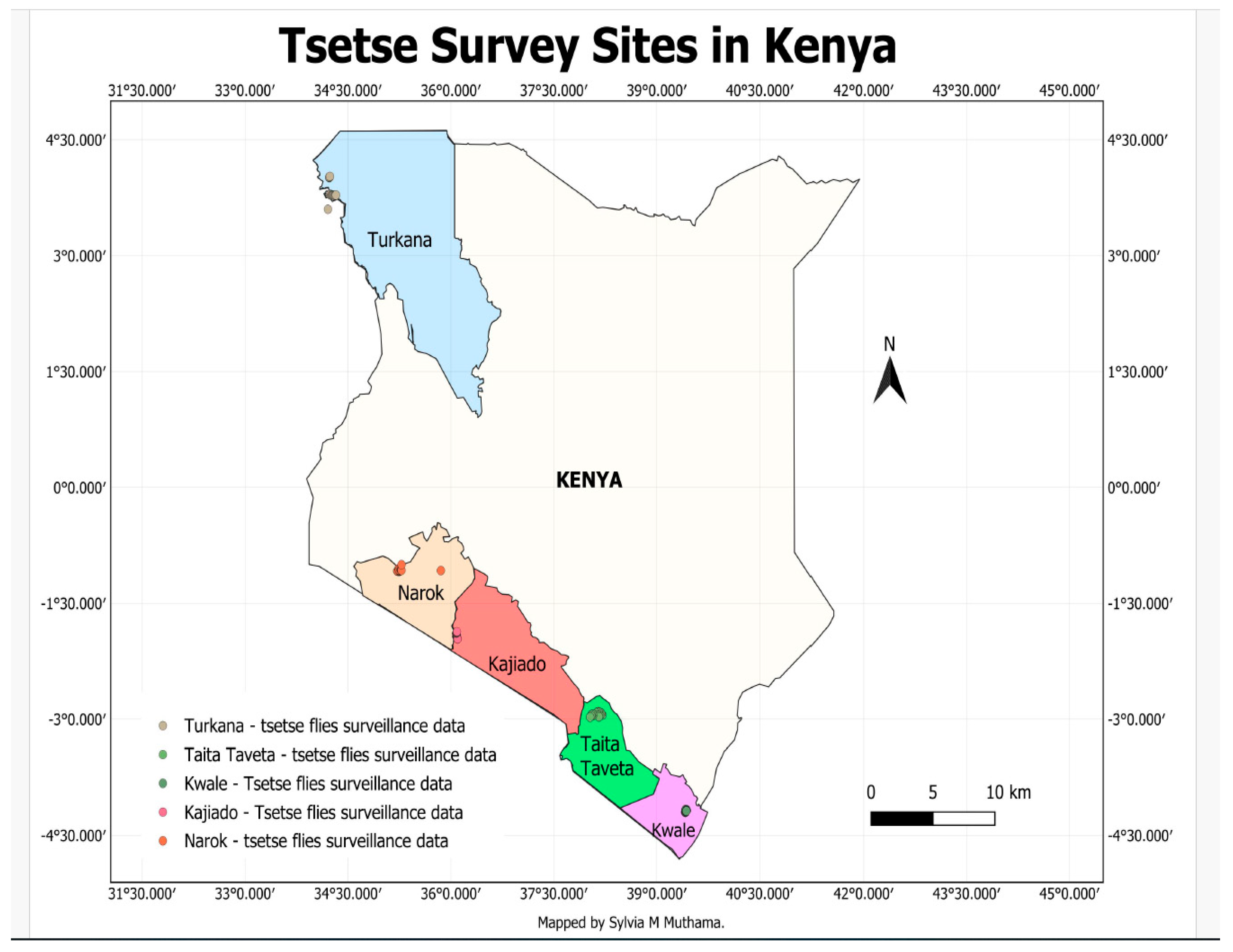

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Trapping of Tsetse Flies

2.2. Molecular Experiments

2.3. Data Analysis

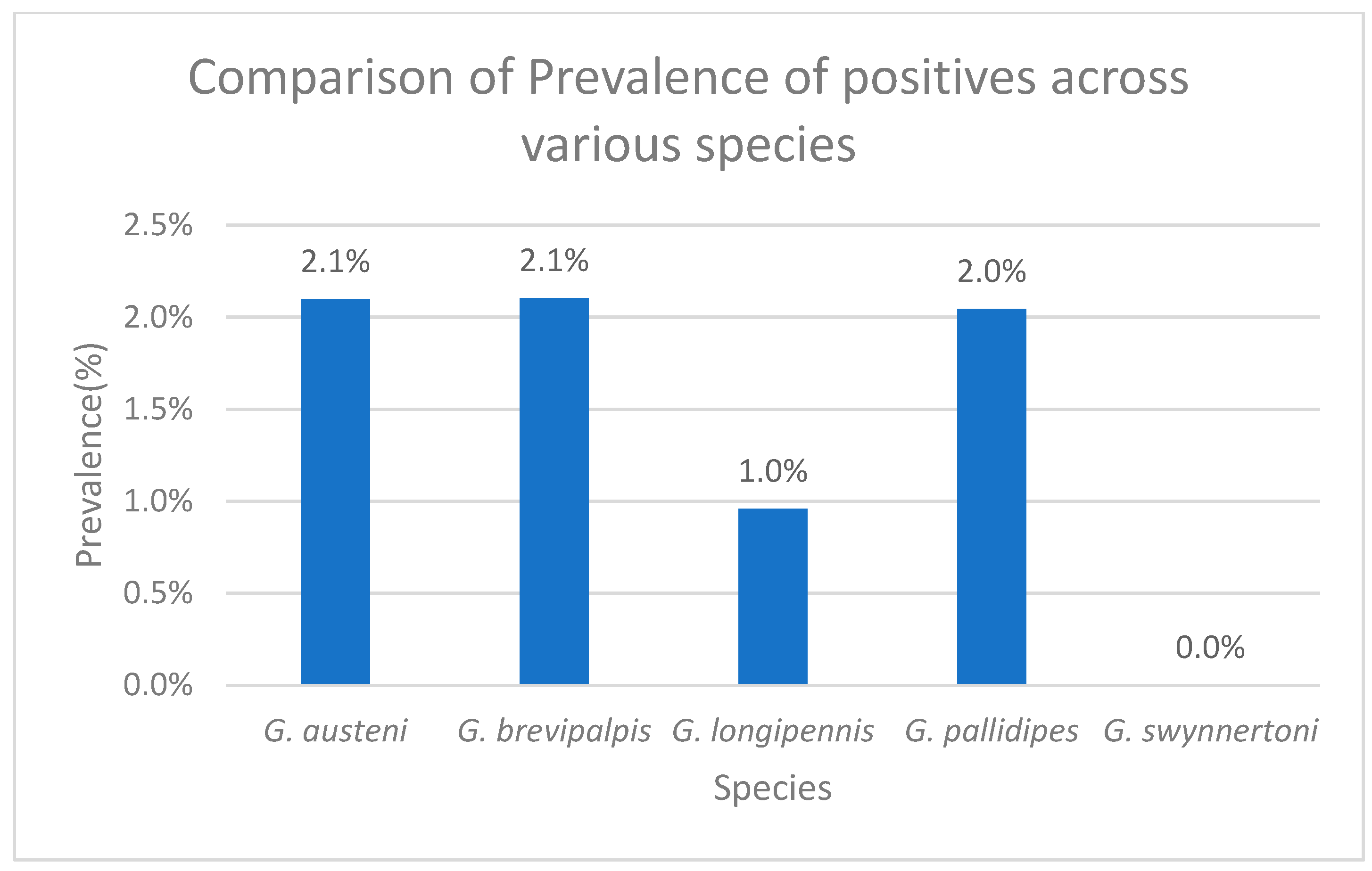

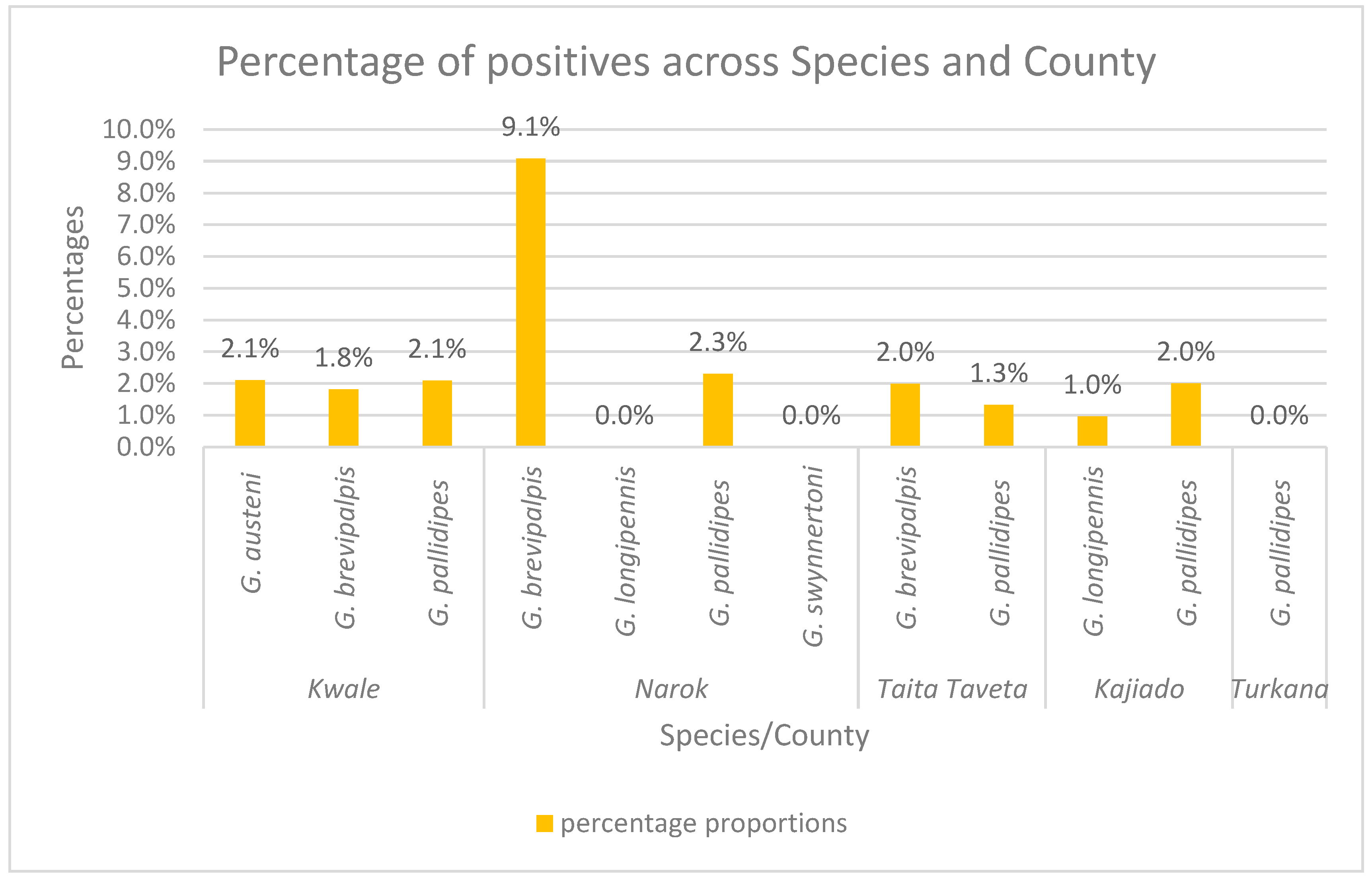

3. Results

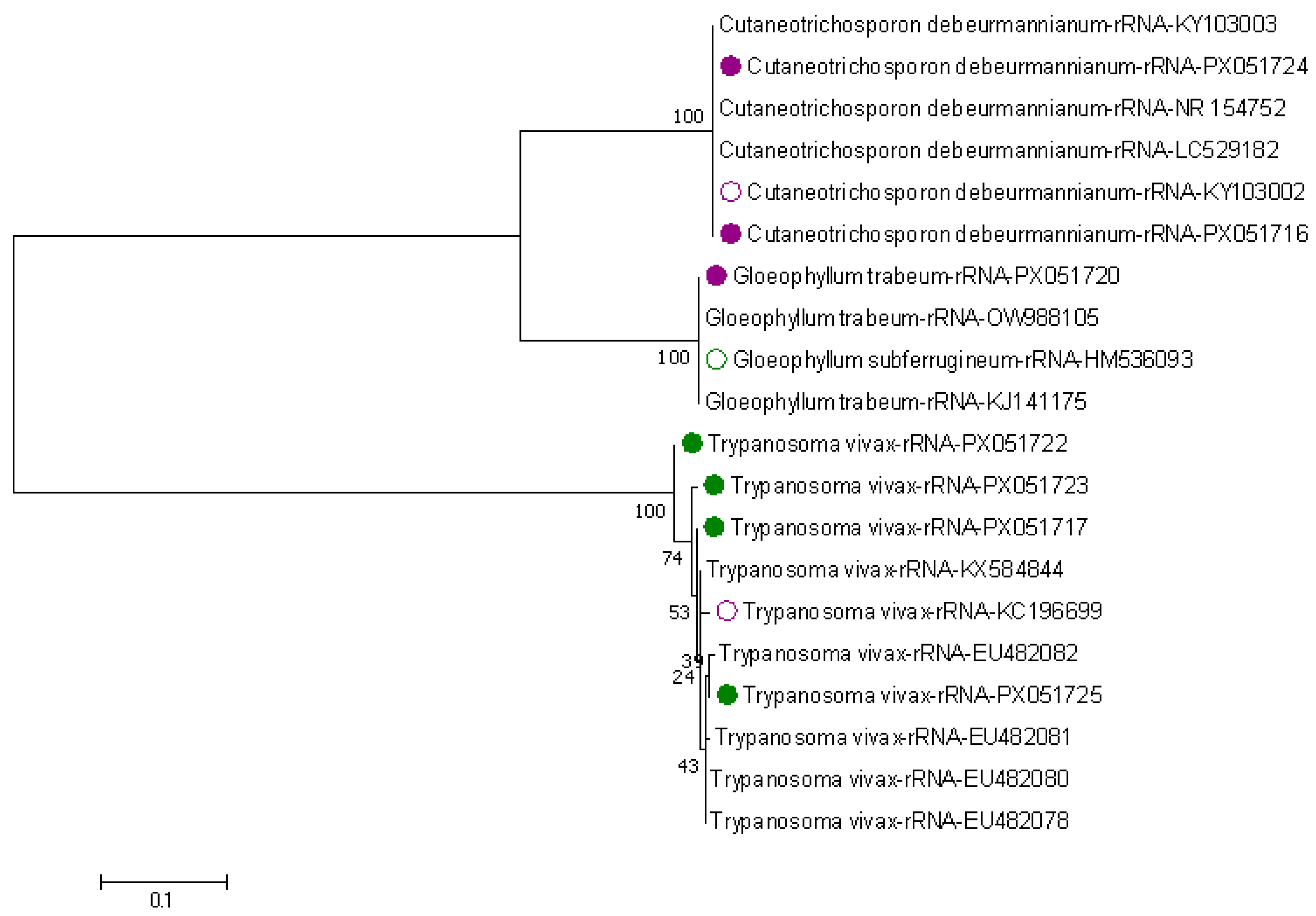

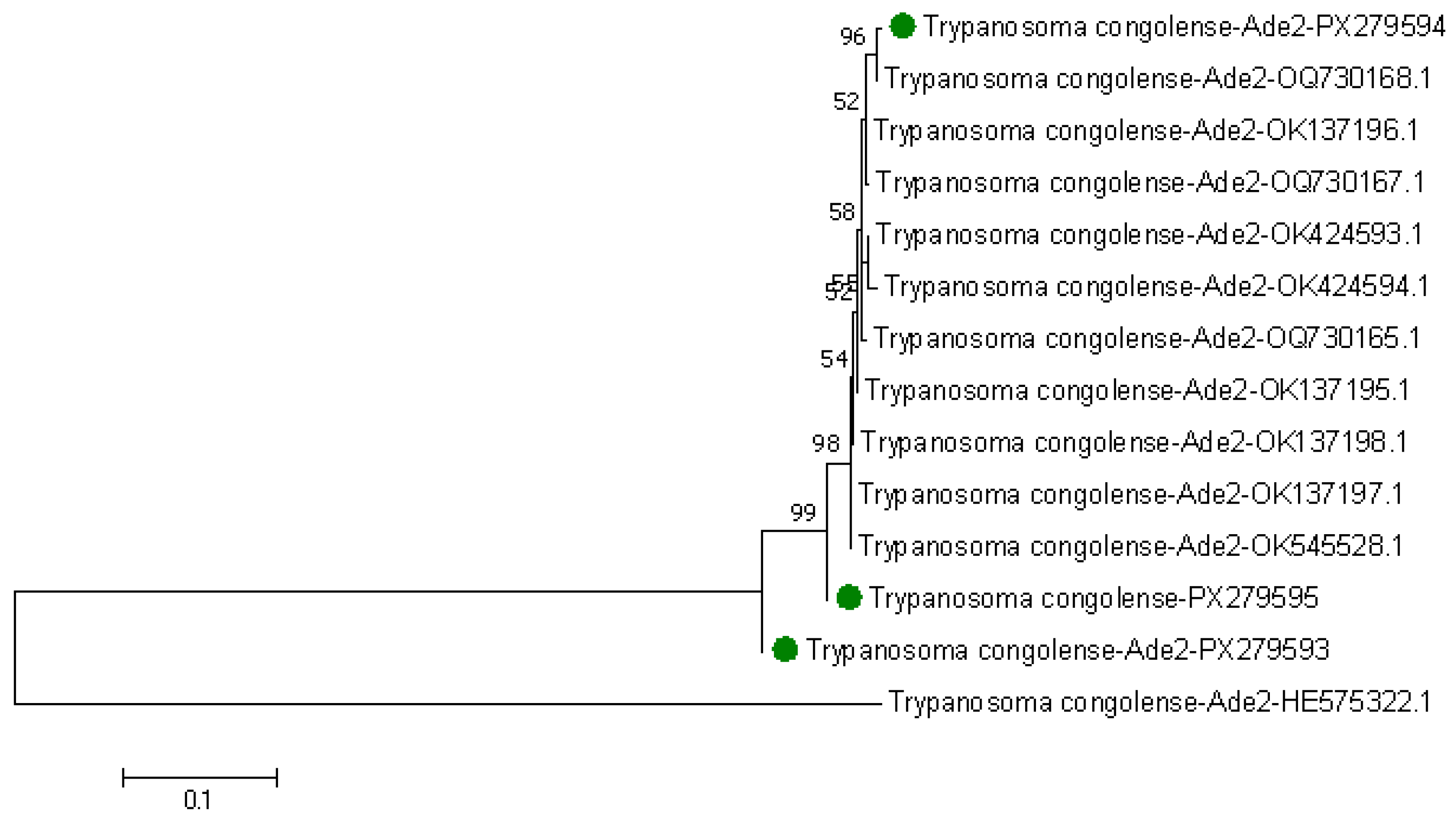

3.1. Sequence Identification

3.2. Genetic Diversity Among Trypanosome Species in Tsetse Flies

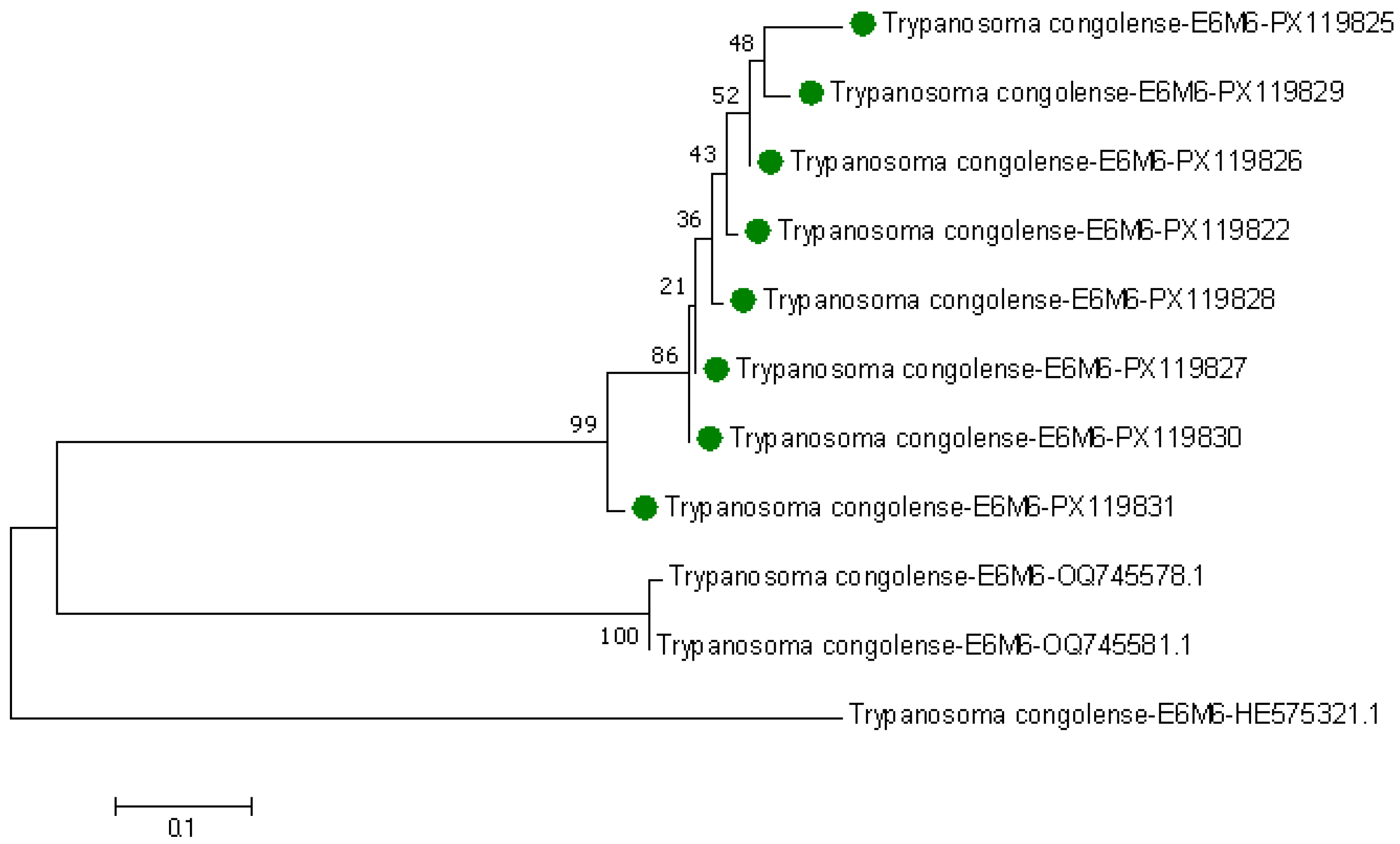

3.3. Phylogenetic Tree of Trypanosomes in Tsetse Flies Based on Amplified Partial 28S and Partial 18S, ITS1, 5.8S, ITS2 rRNA Genes

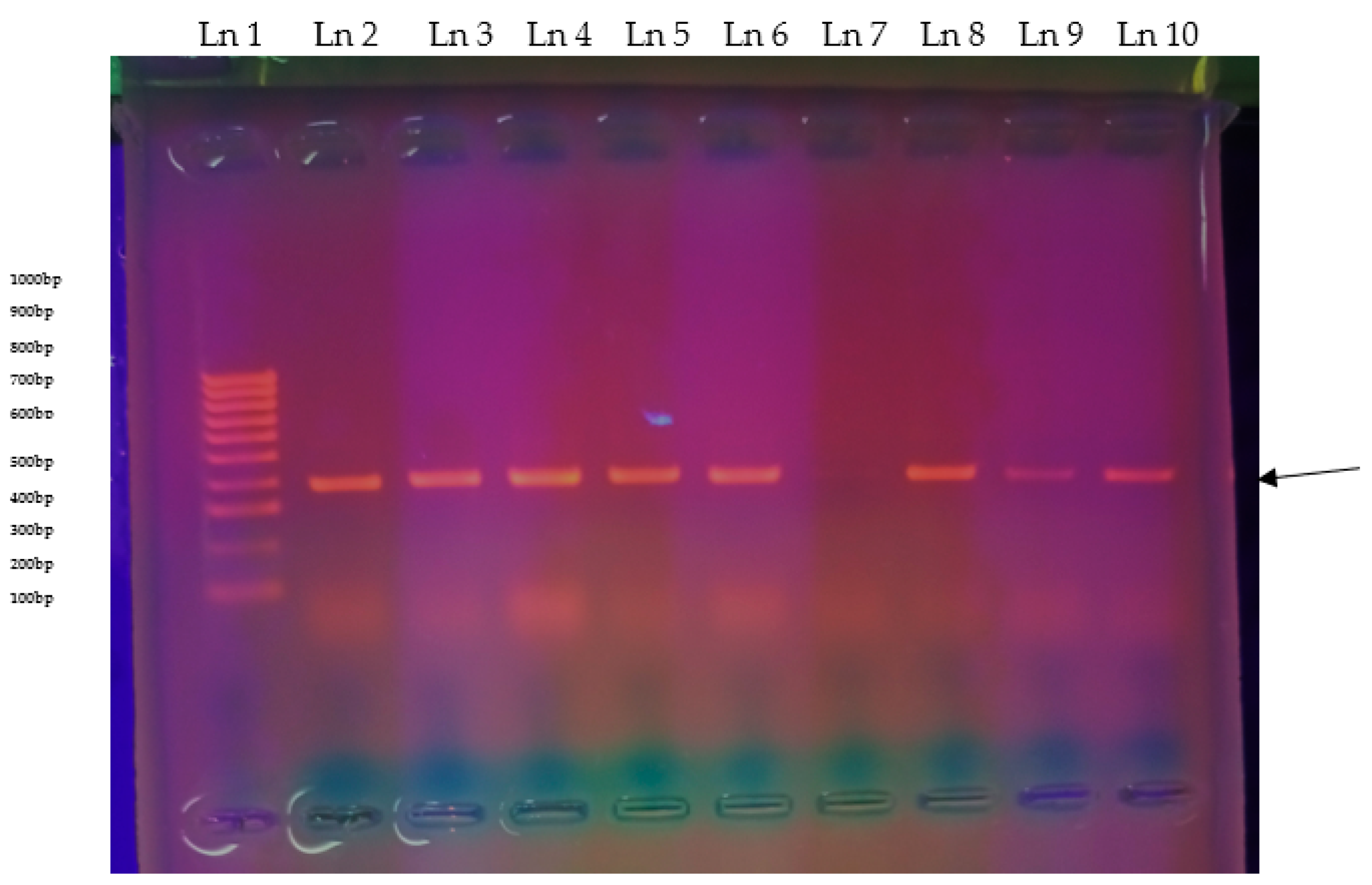

3.4. Transporter Genes Detection and Sequence Comparisons

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| KENTTEC | Kenya Tsetse and Trypanosomiasis Eradication Council |

| AAT | African animal trypanosomiasis |

| rRNA | ribosomal RNA gene |

| ITS1 | Internal transcribed spacer 1 region |

| DMT | drug metabolite transporter |

| RFLP | restriction fragment length polymorphisms |

| TbAT/P2 | Trypanosome brucei adenosine transporter gene |

| E6M6 | ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter gene |

| TcoAde2 | Trypanosoma congolense adenosine transporter gene |

References

- Ngari, N.N.; Gamba, D.O.; Olet, P.A.; Zhao, W.; Paone, M.; Cecchi, G. Developing a National Atlas to Support the Progressive Control of Tsetse-Transmitted Animal Trypanosomosis in Kenya. Parasit. Vectors 2020, 13, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simwango, M.; Ngonyoka, A.; Nnko, H.J.; Salekwa, L.P.; Ole-Neselle, M.; Kimera, S.I.; Gwakisa, P.S. Molecular Prevalence of Trypanosome Infections in Cattle and Tsetse Flies in the Maasai Steppe, Northern Tanzania. Parasit. Vectors 2017, 10, 507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheferaw, D.; Birhanu, B.; Asrade, B.; Abera, M.; Tusse, T.; Fikadu, A.; Denbarga, Y.; Gona, Z.; Regassa, A.; Moje, N.; et al. Bovine Trypanosomosis and Glossina Distribution in Selected Areas of Southern Part of Rift Valley, Ethiopia. Acta Trop. 2016, 154, 145–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fineile, P.; Murray, M.; Barry, J.D.; Morrison, W.I.; Williams, R.O.; Hirum, H.; Rovis, L. African Animal Trypanosomiasis. In World Animal Review, 3rd ed.; Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO): Rome, Italy, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, S.K.; Rahman, A.H.; Hassan, M.A.; Salih, S.E.M.; Paone, M.; Cecchi, G. An Atlas of Tsetse and Bovine Trypanosomosis in Sudan. Parasit. Vectors 2016, 9, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desquesnes, M.; Dia, M.L. Mechanical Transmission of Trypanosoma vivax in Cattle by the African Tabanid Atylotus fuscipes. Vet. Parasitol. 2004, 119, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desquesnes, M.; Biteau-Coroller, F.; Bouyer, J.; Dia, M.L.; Foil, L. Development of a Mathematical Model for Mechanical Transmission of Trypanosomes and Other Pathogens of Cattle Transmitted by Tabanids. Int. J. Parasitol. 2009, 39, 333–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okello, I.; Mafie, E.; Eastwood, G.; Nzalawahe, J.; Mboera, L.E.G. African Animal Trypanosomiasis: A Systematic Review on Prevalence, Risk Factors and Drug Resistance in Sub-Saharan Africa. J. Med. Entomol. 2022, 59, 1099–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nsengimana, I.; Hakizimana, E.; Mupfasoni, J.; Hakizimana, J.N.; Chengula, A.A.; Kasanga, C.J.; Eastwood, G. Identification of Potential Vectors and Detection of Rift Valley Fever Virus in Mosquitoes Collected Before and During the 2022 Outbreak in Rwanda. Pathogens 2025, 14, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekra, J.Y.; Mafie, E.M.; N’Goran, E.K.; Kaba, D.; Gragnon, B.G.; Srinivasan, J. Genetic Diversity of Trypanosomes Infesting Cattle from Savannah District in North of Côte d’Ivoire Using Conserved Genomic Signatures: RRNA, ITS1 and GGAPDH. Pathogens 2024, 13, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulohoma, B.W.; Wamwenje, S.A.O.; Wangwe, I.I.; Masila, N.; Mirieri, C.K.; Wambua, L. Prevalence of Trypanosomes Associated with Drug Resistance in Shimba Hills, Kwale County, Kenya. BMC Res. Notes 2020, 13, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okello, I.; Nzalawahe, J.; Mafie, E.; Eastwood, G. Seasonal Variation in Tsetse Fly Apparent Density and Trypanosoma spp. Infection Rate and Occurrence of Drug-Resistant Trypanosomes in Lambwe, Kenya. Parasitol. Res. 2024, 123, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitanga, S.; Marcotty, T.; Namangala, B.; Van den Bossche, P.; Van Den Abbeele, J.; Delespaux, V. High Prevalence of Drug Resistance in Animal Trypanosomes without a History of Drug Exposure. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2011, 5, 1454–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munday, J.C.; Tagoe, D.N.A.; Eze, A.A.; Krezdorn, J.A.M.; Rojas López, K.E.; Alkhaldi, A.A.M.; McDonald, F.; Still, J.; Alzahrani, K.J.; Settimo, L.; et al. Functional Analysis of Drug Resistance-Associated Mutations in the Trypanosoma brucei Adenosine Transporter 1 (TbAT1) and the Proposal of a Structural Model for the Protein. Mol. Microbiol. 2015, 96, 887–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tihon, E.; Imamura, H.; Van den Broeck, F.; Vermeiren, L.; Dujardin, J.C.; Van Den Abbeele, J. Genomic Analysis of Isometamidium Chloride Resistance in Trypanosoma congolense. Int. J. Parasitol. Drugs Drug Resist. 2017, 7, 350–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delespaux, V.; Geysen, D.; Majiwa, P.A.O.; Geerts, S. Identification of a Genetic Marker for Isometamidium Chloride Resistance in Trypanosoma congolense. Int. J. Parasitol. 2005, 35, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delespaux, V.; Chitanga, S.; Geysen, D.; Goethals, A.; Van den Bossche, P.; Geerts, S. SSCP Analysis of the P2 Purine Transporter TcoAT1 Gene of Trypanosoma congolense Leads to a Simple PCR-RFLP Test Allowing the Rapid Identification of Diminazene Resistant Stocks. Acta Trop. 2006, 100, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekra, J.-Y.; Mafie, E.M.; Sonan, H.; Kanh, M.; Gragnon, B.G.; N’Goran, E.K.; Srinivasan, J. Trypanocide Use and Molecular Characterization of Trypanosomes Resistant to Diminazene Aceturate in Cattle in Northern Côte D’Ivoire. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2024, 9, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitouley, H.S.; Mungube, E.O.; Allegye-Cudjoe, E.; Diall, O.; Bocoum, Z.; Diarra, B.; Randolph, T.F.; Bauer, B.; Clausen, P.H.; Geysen, D.; et al. Improved Pcr-Rflp for the Detection of Diminazene Resistance in Trypanosoma congolense under Field Conditions Using Filter Papers for Sample Storage. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2011, 5, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okello, I.; Mafie, E.; Nzalawahe, J.; Eastwood, G.; Mboera, L.E.G.; Hakizimana, J.N.; Ogola, K. Trypanosoma congolense Resistant to Trypanocidal Drugs Homidium and Diminazene and Their Molecular Characterization in Lambwe, Kenya. Acta Parasitol. 2023, 68, 130–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugunieri, G.L.; Murilla, G.A. Resistance to Trypanocidal Drugs—Suggestions from Field Survey on Drug Use in Kwale District, Kenya. Onderstepoort J. Vet. Res. 2003, 70, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rayaisse, J.B.; Tirados, I.; Kaba, D.; Dewhirst, S.Y.; Logan, J.G.; Diarrassouba, A.; Salou, E.; Omolo, M.O.; Solano, P.; Lehane, M.J.; et al. Prospects for the Development of Odour Baits to Control the Tsetse Flies Glossina tachinoides and G. palpalis s.L. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2010, 4, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torr, S.J.; Hall, D.R.; Phelps, R.J.; Vale, G.A. Methods for Dispensing Odour Attractants for Tsetse Flies (Diptera: Glossinidae). Bull. Entomol. Res. 1997, 87, 299–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RGooding, H.; Krafsur, E.S. Tsetse Genetics: Contributions to Biology, Systematics, and Control of Tsetse Flies. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2005, 50, 101–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, A.; Tilley, A.; McOdimba, F.; Fyfe, J.; Eisler, M.; Hide, G.; Welburn, S. A PCR Based Assay for Detection and Differentiation of African Trypanosome Species in Blood. Exp. Parasitol. 2005, 111, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyana Pati, P.; Van Reet, N.; Mumba Ngoyi, D.; Ngay Lukusa, I.; Karhemere Bin Shamamba, S.; Büscher, P. Melarsoprol Sensitivity Profile of Trypanosoma brucei gambiense Isolates from Cured and Relapsed Sleeping Sickness Patients from the Democratic Republic of the Congo. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2014, 8, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Li, M.; Knyaz, C.; Tamura, K. MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis across Computing Platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018, 35, 1547–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wamwiri, F.N.; Changasi, R.E. Tsetse Flies Glossina as Vectors of Human African Trypanosomiasis: A Review. Biomed. Res. Int. 2016, 8, 2–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adungo, F.; Mokaya, T.; Makwaga, O.; Mwau, M. Tsetse Distribution, Trypanosome Infection Rates, and Small-Holder Livestock Producers’ Capacity Enhancement for Sustainable Tsetse and Trypanosomiasis Control in Busia, Kenya. Trop. Med. Health 2020, 48, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keita, M.L.; Medkour, H.; Sambou, M.; Dahmana, H.; Mediannikov, O. Tabanids as Possible Pathogen Vectors in Senegal (West Africa). Parasites Vectors 2020, 13, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamilton, P.B.; Stevens, J.R.; Gaunt, M.W.; Gidley, J.; Gibson, W.C. Trypanosomes Are Monophyletic: Evidence from Genes for Glyceraldehyde Phosphate Dehydrogenase and Small Subunit Ribosomal RNA. Int. J. Parasitol. 2004, 34, 1393–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djohan, V.; Kaba, D.; Rayaissé, J.B.; Dayo, G.K.; Coulibaly, B.; Salou, E.; Dofini, F.; Kouadio, A.D.M.K.; Menan, H.; Solano, P. Detection and Identification of Pathogenic Trypanosome Species in Tsetse Flies along the Comoé River in Côte d’Ivoire. Parasite 2015, 22, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- County Government of Taita Taveta. County Government of Taita Taveta—Integrated Development Plan 2018–2022; County Government of Taita Taveta: Wundanyi, Kenya, 2018; p. 459.

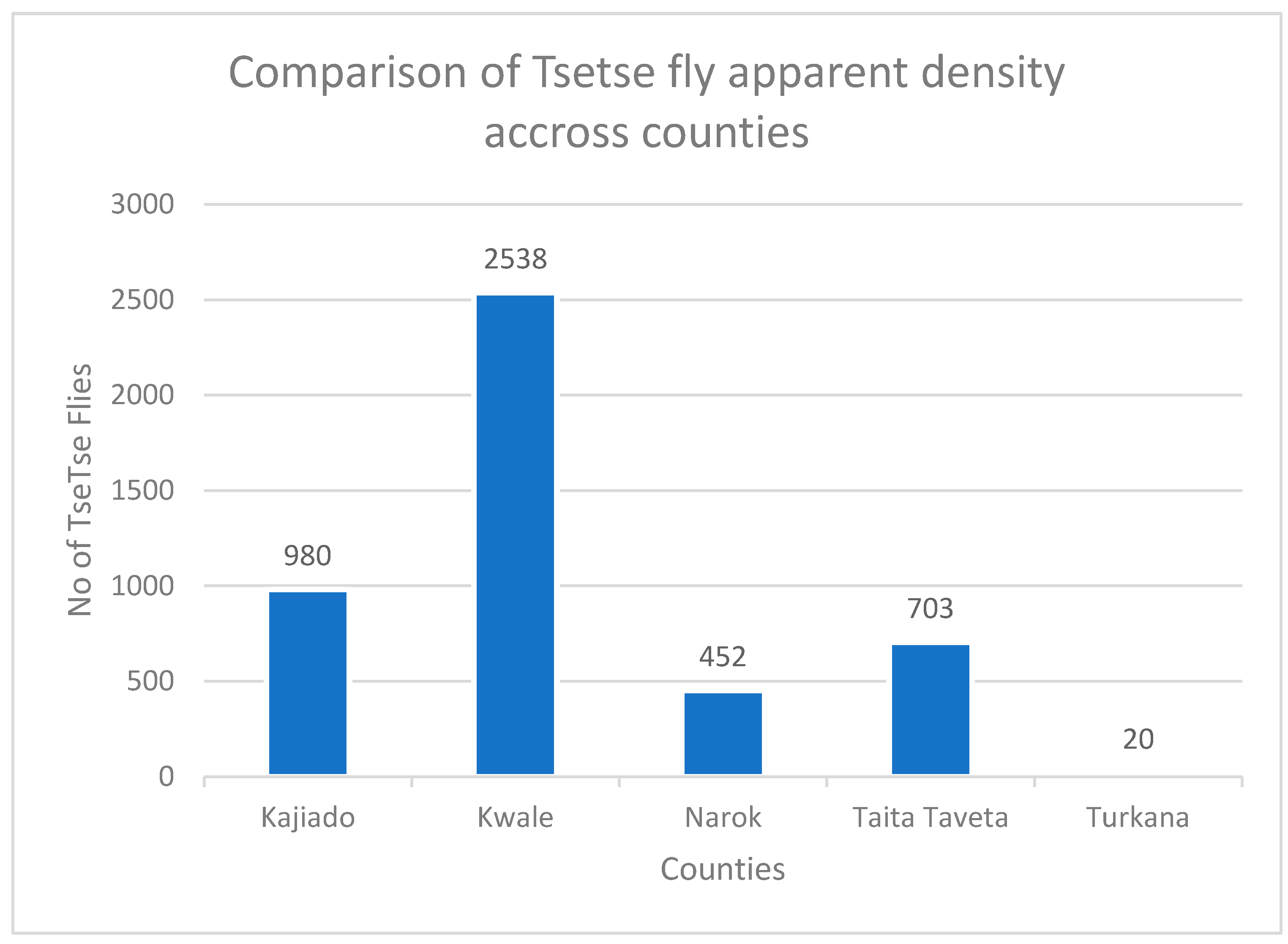

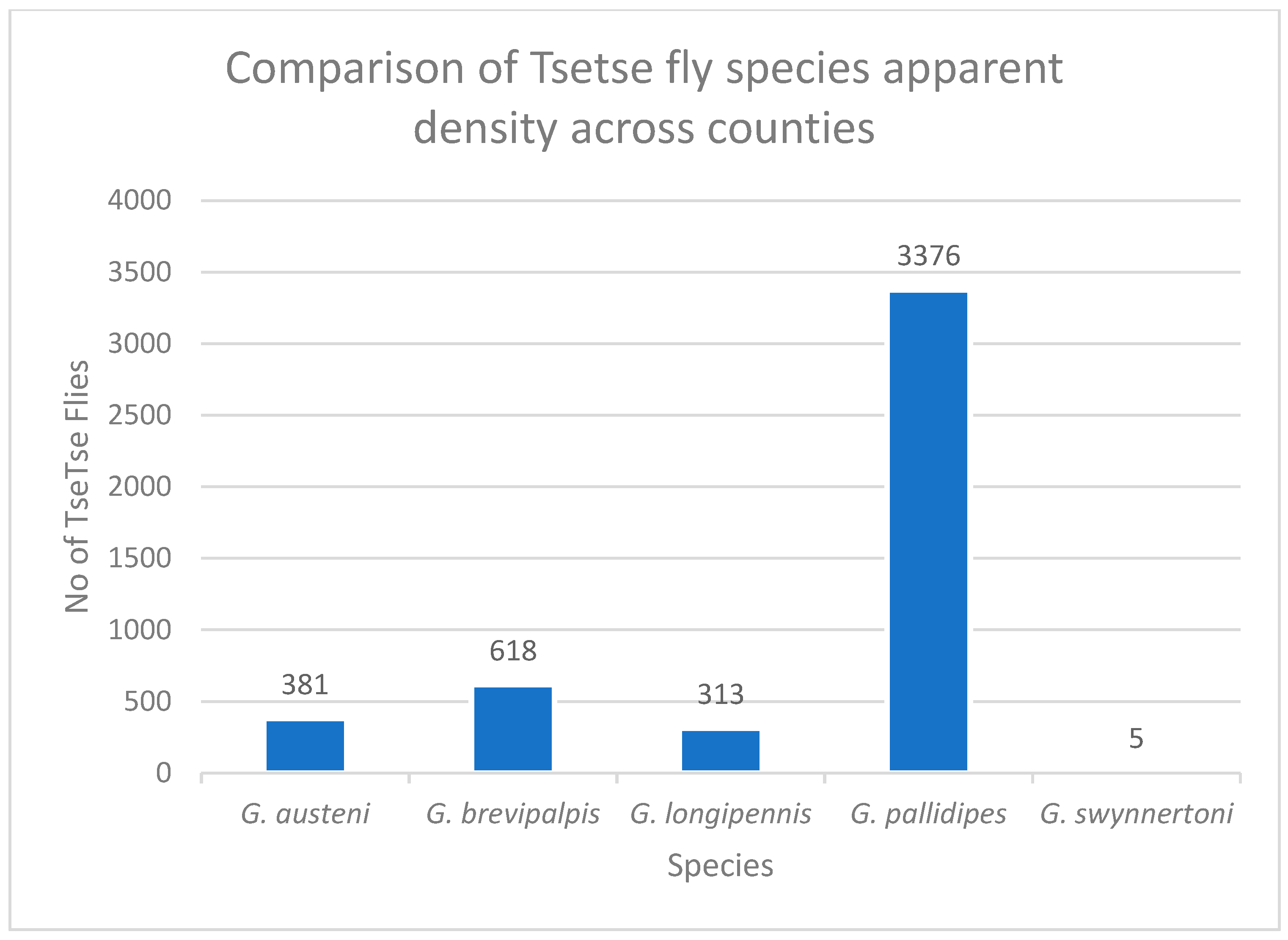

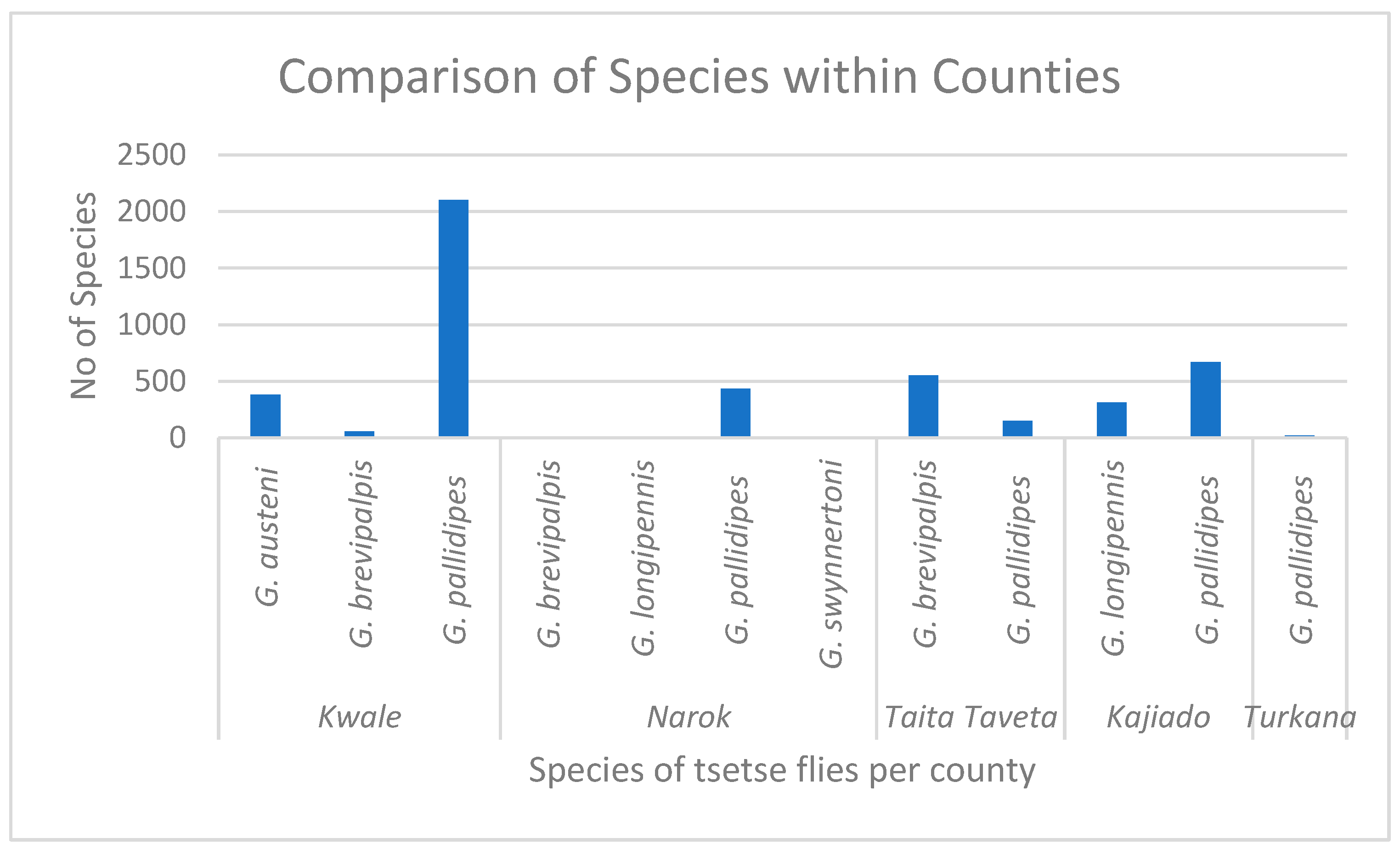

| Narok | Tb | Tv | Tc | Mixed Tv + Tb | Mixed Tv + Tc | Mixed Tc + Tb | Mixed Tv + Tc + Tb | Total Infections | Total Tsetse Flies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G. pallidipes | 4 | 4 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 435 |

| G. brevipalpis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 11 |

| G. swynnertoni | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| G. longipennis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Total | 4 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 452 |

| Kwale | Tb | Tv | Tc | Mixed Tv + Tb | Mixed Tv + Tc | Mixed Tc + Tb | Mixed Tv + Tc + Tb | Total infections | Total tsetse flies |

| G. pallidipes | 6 | 6 | 21 | 1 | 3 | 7 | 0 | 44 | 2102 |

| G. autseni | 2 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 381 |

| G. brevipalpis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 55 |

| Total | 8 | 8 | 25 | 1 | 4 | 7 | 0 | 53 | 2538 |

| Taita-Taveta | Tb | Tv | Tc | Mixed Tv + Tb | Mixed Tv + Tc | Mixed Tc + Tb | Mixed Tv + Tc + Tb | Total infections | Total tsetse flies |

| G. pallidipes | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 151 |

| G. brevipalpis | 4 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 11 | 552 |

| Total | 4 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 13 | 703 |

| Kajiado | Tb | Tv | Tc | Mixed Tv + Tb | Mixed Tv + Tc | Mixed Tc + Tb | Mixed Tv + Tc + Tb | Total infections | Total tsetse flies |

| G. pallidipes | 9 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 668 |

| G. longipennis | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 312 |

| Total | 10 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 15 | 980 |

| Turkana | Tb | Tv | Tc | Mixed Tv + Tb | Mixed Tv + Tc | Mixed Tc + Tb | Mixed Tv + Tc + Tb | Total infections | Total tsetse flies |

| G. pallidipes | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 |

| Total | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 |

| Overall total | 26 | 18 | 29 | 8 | 4 | 8 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Okello, I.S.; Onyoyo, S.G.; Kiteto, I.N.; Korir, S.M.; Onyango, S.O. Identification of Potential Vectors and Species Density of Tsetse Fly, Prevalence, and Genetic Diversity of Drug-Resistant Trypanosomes in Kenya. Pathogens 2025, 14, 1207. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121207

Okello IS, Onyoyo SG, Kiteto IN, Korir SM, Onyango SO. Identification of Potential Vectors and Species Density of Tsetse Fly, Prevalence, and Genetic Diversity of Drug-Resistant Trypanosomes in Kenya. Pathogens. 2025; 14(12):1207. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121207

Chicago/Turabian StyleOkello, Ivy S., Samuel G. Onyoyo, Isaiah N. Kiteto, Sylvia M. Korir, and Seth. O. Onyango. 2025. "Identification of Potential Vectors and Species Density of Tsetse Fly, Prevalence, and Genetic Diversity of Drug-Resistant Trypanosomes in Kenya" Pathogens 14, no. 12: 1207. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121207

APA StyleOkello, I. S., Onyoyo, S. G., Kiteto, I. N., Korir, S. M., & Onyango, S. O. (2025). Identification of Potential Vectors and Species Density of Tsetse Fly, Prevalence, and Genetic Diversity of Drug-Resistant Trypanosomes in Kenya. Pathogens, 14(12), 1207. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121207