Targeting Gut–Lung Crosstalk in Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome: Exploring the Therapeutic Potential of Fecal Microbiota Transplantation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

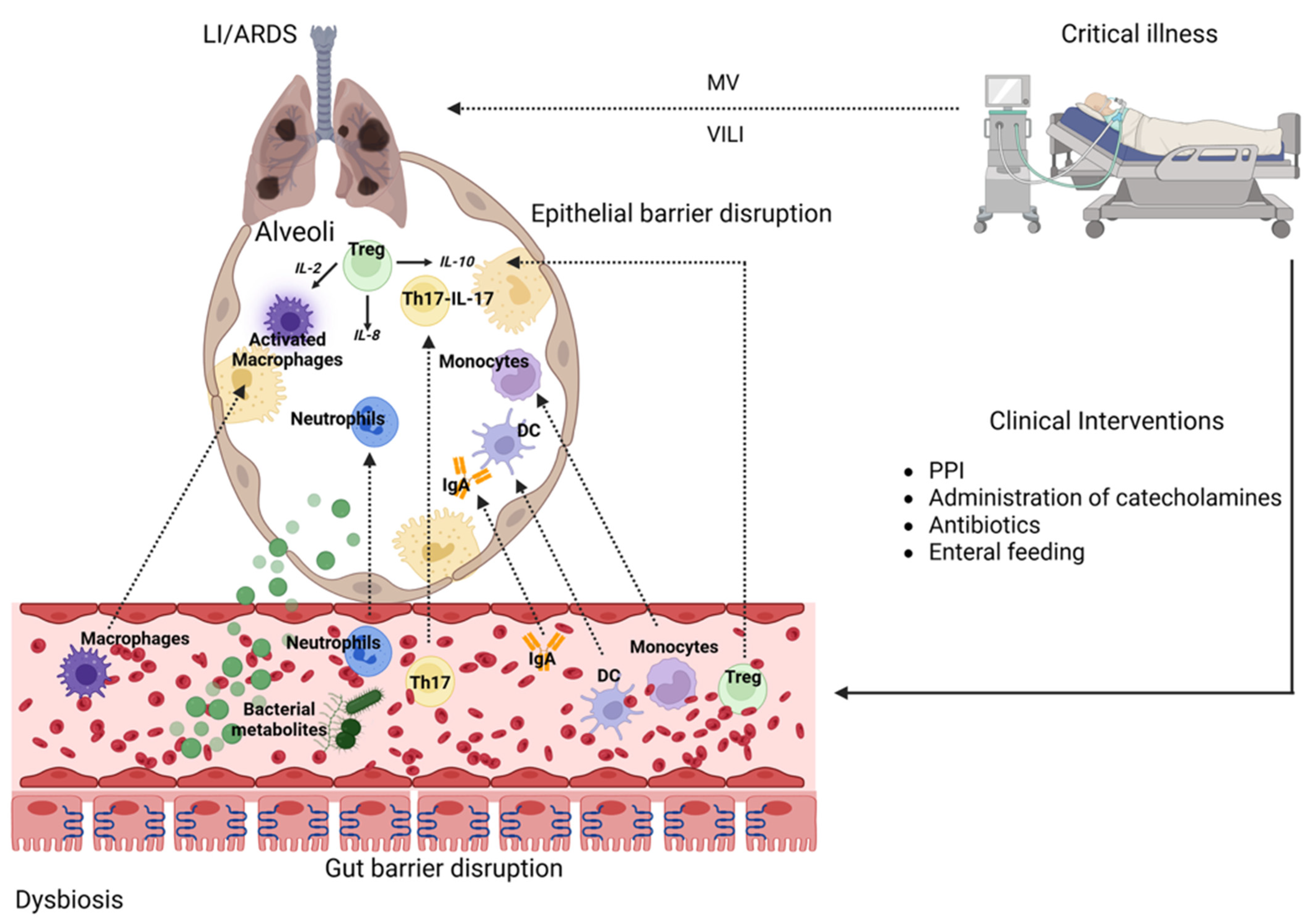

3. The Gut–Lung Axis in ARDS

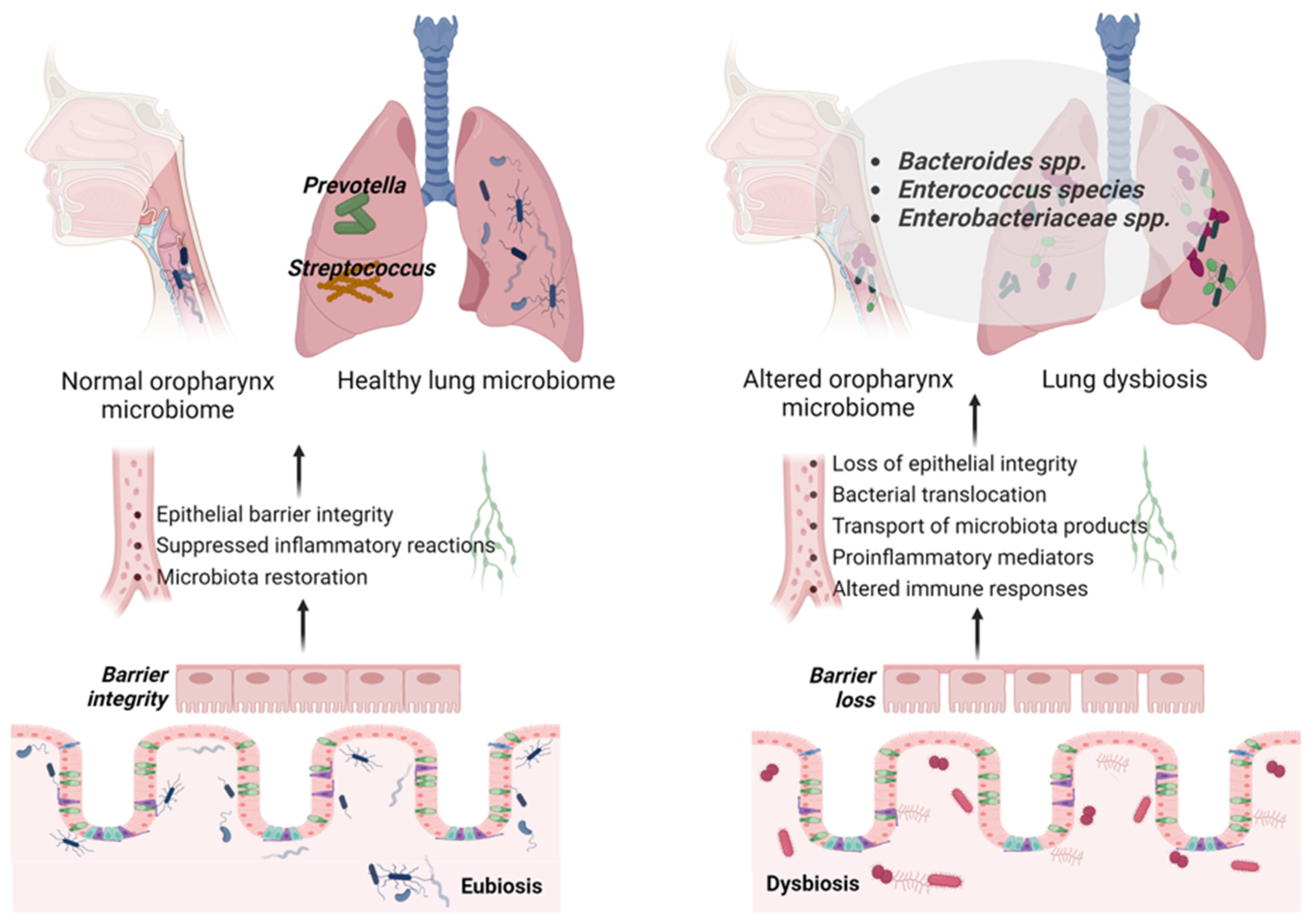

3.1. Gut–Lung Microbiota Axis in ARDS

3.2. Gut Microbiome in ARDS

3.3. Lung Microbiome in ARDS

4. Therapeutic Implications and Area of Further Research

Fecal Microbiota Transplantation

| Evidence Source | Model/Study Type | Key Findings | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preclinical studies | Animal models of LI, pneumonia, and ARDS | FMT restored gut–lung immune balance, reduced inflammation and fibrosis, improved oxygenation, and decreased mortality. | [41,133,145,146,147,148,149,150,151] |

| Human studies in LI/ARDS | Case report | Severe ARDS with refractory CDI; FMT via upper endoscopy resolved diarrhea. Data on ARDS outcomes were not reported. | [33] |

| Human studies in severe pneumonia | Case report | 95-year-old with severe pneumonia and pan-drug-resistant K. pneumoniae; FMT led to respiratory improvement and clinical recovery after treatment failure. | [132] |

| Human studies in respiratory failure, other etiology (ALS) | Case series, RCT | RCT (27 pts): No significant effect of FMT on respiratory function. Case series: Marked respiratory improvement and ventilator weaning after FMT. | [42,152] |

| Human studies in sepsis, MODS, and severe infection | Case reports, case series | FMT restored gut microbiota, alleviated systemic inflammation, and improved clinical status; respiratory outcomes were not always explicitly reported, but overall organ function and recovery were supported. | [37,38,39,40,153,154,155,156,157,158] |

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bellani, G.; Laffey, J.G.; Pham, T.; Fan, E.; Brochard, L.; Esteban, A.; Gattinoni, L.; van Haren, F.; Larsson, A.; McAuley, D.F.; et al. Epidemiology, Patterns of Care, and Mortality for Patients with Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome in Intensive Care Units in 50 Countries. JAMA 2016, 315, 788–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Force, A.D.T.; Ranieri, V.M.; Rubenfeld, G.D.; Thompson, B.T.; Ferguson, N.D.; Caldwell, E.; Fan, E.; Camporota, L.; Slutsky, A.S. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: The Berlin Definition. JAMA 2012, 307, 2526–2533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, T.; Madotto, F.; Pham, T.; Nagata, I.; Uchida, M.; Tamiya, N.; Kurahashi, K.; Bellani, G.; Laffey, J.G.; Investigators, L.-S.; et al. Epidemiology and patterns of tracheostomy practice in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome in ICUs across 50 countries. Crit. Care 2018, 22, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Opitz, B.; van Laak, V.; Eitel, J.; Suttorp, N. Innate immune recognition in infectious and noninfectious diseases of the lung. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2010, 181, 1294–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mantovani, A.; Cassatella, M.A.; Costantini, C.; Jaillon, S. Neutrophils in the activation and regulation of innate and adaptive immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2011, 11, 519–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imai, Y.; Kuba, K.; Neely, G.G.; Yaghubian-Malhami, R.; Perkmann, T.; van Loo, G.; Ermolaeva, M.; Veldhuizen, R.; Leung, Y.H.; Wang, H.; et al. Identification of oxidative stress and Toll-like receptor 4 signaling as a key pathway of acute lung injury. Cell 2008, 133, 235–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthay, M.A.; Ware, L.B.; Zimmerman, G.A. The acute respiratory distress syndrome. J. Clin. Investig. 2012, 122, 2731–2740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ware, L.B.; Matthay, M.A. Alveolar fluid clearance is impaired in the majority of patients with acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2001, 163, 1376–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthay, M.A.; Zimmerman, G.A. Acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome: Four decades of inquiry into pathogenesis and rational management. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2005, 33, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quilez, M.E.; Lopez-Aguilar, J.; Blanch, L. Organ crosstalk during acute lung injury, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and mechanical ventilation. Curr. Opin. Crit. Care 2012, 18, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziaka, M.; Exadaktylos, A. Exploring the lung-gut direction of the gut-lung axis in patients with ARDS. Crit. Care 2024, 28, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putensen, C.; Wrigge, H.; Hering, R. The effects of mechanical ventilation on the gut and abdomen. Curr. Opin. Crit. Care 2006, 12, 160–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deitch, E.A. Bacterial translocation or lymphatic drainage of toxic products from the gut: What is important in human beings? Surgery 2002, 131, 241–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, R.; Coopersmith, C.M. Redefining the gut as the motor of critical illness. Trends Mol. Med. 2014, 20, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatt, M.; Reddy, B.S.; MacFie, J. Review article: Bacterial translocation in the critically ill-evidence and methods of prevention. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2007, 25, 741–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reintam, A.; Kern, H.; Starkopf, J. Defining gastrointestinal failure. Acta Clin. Belg. 2007, 62 (Suppl. S1), 168–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Louis, K.; Netea, M.G.; Carrer, D.P.; Kotsaki, A.; Mylona, V.; Pistiki, A.; Savva, A.; Roditis, K.; Alexis, A.; Van der Meer, J.W.; et al. Bacterial translocation in an experimental model of multiple organ dysfunctions. J. Surg. Res. 2013, 183, 686–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, R.P.; Singer, B.H.; Newstead, M.W.; Falkowski, N.R.; Erb-Downward, J.R.; Standiford, T.J.; Huffnagle, G.B. Enrichment of the lung microbiome with gut bacteria in sepsis and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Nat. Microbiol. 2016, 1, 16113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unertl, K.; Ruckdeschel, G.; Selbmann, H.K.; Jensen, U.; Forst, H.; Lenhart, F.P.; Peter, K. Prevention of colonization and respiratory infections in long-term ventilated patients by local antimicrobial prophylaxis. Intensive Care Med. 1987, 13, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestri, L.; de la Cal, M.A.; van Saene, H.K. Selective decontamination of the digestive tract: The mechanism of action is control of gut overgrowth. Intensive Care Med. 2012, 38, 1738–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silvestri, L.; van Saene, H.K.; Zandstra, D.F.; Marshall, J.C.; Gregori, D.; Gullo, A. Impact of selective decontamination of the digestive tract on multiple organ dysfunction syndrome: Systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Crit. Care Med. 2010, 38, 1370–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickson, R.P. The microbiome and critical illness. Lancet Respir. Med. 2016, 4, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, D.G.; Vieira, A.T.; Soares, A.C.; Pinho, V.; Nicoli, J.R.; Vieira, L.Q.; Teixeira, M.M. The essential role of the intestinal microbiota in facilitating acute inflammatory responses. J. Immunol. 2004, 173, 4137–4146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Chen, G.; Manwani, D.; Mortha, A.; Xu, C.; Faith, J.J.; Burk, R.D.; Kunisaki, Y.; Jang, J.E.; Scheiermann, C.; et al. Neutrophil ageing is regulated by the microbiome. Nature 2015, 525, 528–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rush, B.F., Jr.; Redan, J.A.; Flanagan, J.J., Jr.; Heneghan, J.B.; Hsieh, J.; Murphy, T.F.; Smith, S.; Machiedo, G.W. Does the bacteremia observed in hemorrhagic shock have clinical significance? A study in germ-free animals. Ann. Surg. 1989, 210, 342–345; discussion 346–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuevas, P.; De la Maza, L.M.; Gilbert, J.; Fine, J. The lung lesion in four different types of shock in rabbits. Arch. Surg. 1972, 104, 319–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiertsema, S.P.; van Bergenhenegouwen, J.; Garssen, J.; Knippels, L.M.J. The Interplay between the Gut Microbiome and the Immune System in the Context of Infectious Diseases throughout Life and the Role of Nutrition in Optimizing Treatment Strategies. Nutrients 2021, 13, 886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziaka, M.; Exadaktylos, A. Gut-derived immune cells and the gut-lung axis in ARDS. Crit. Care 2024, 28, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, S.R.; Pop, M.; Deboy, R.T.; Eckburg, P.B.; Turnbaugh, P.J.; Samuel, B.S.; Gordon, J.I.; Relman, D.A.; Fraser-Liggett, C.M.; Nelson, K.E. Metagenomic analysis of the human distal gut microbiome. Science 2006, 312, 1355–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avila, P.R.M.; Michels, M.; Vuolo, F.; Bilesimo, R.; Burger, H.; Milioli, M.V.M.; Sonai, B.; Borges, H.; Carneiro, C.; Abatti, M.; et al. Protective effects of fecal microbiota transplantation in sepsis are independent of the modulation of the intestinal flora. Nutrition 2020, 73, 110727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zou, G.; Li, B.; Du, X.; Sun, Z.; Sun, Y.; Jiang, X. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT) Alleviates Experimental Colitis in Mice by Gut Microbiota Regulation. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 30, 1132–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costello, S.P.; Hughes, P.A.; Waters, O.; Bryant, R.V.; Vincent, A.D.; Blatchford, P.; Katsikeros, R.; Makanyanga, J.; Campaniello, M.A.; Mavrangelos, C.; et al. Effect of Fecal Microbiota Transplantation on 8-Week Remission in Patients with Ulcerative Colitis: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2019, 321, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.E.; Gweon, T.G.; Yeo, C.D.; Cho, Y.S.; Kim, G.J.; Kim, J.Y.; Kim, J.W.; Kim, H.; Lee, H.W.; Lim, T.; et al. A case of Clostridium difficile infection complicated by acute respiratory distress syndrome treated with fecal microbiota transplantation. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 12687–12690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gai, X.; Wang, H.; Li, Y.; Zhao, H.; He, C.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, H. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation Protects the Intestinal Mucosal Barrier by Reconstructing the Gut Microbiota in a Murine Model of Sepsis. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 736204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Nood, E.; Vrieze, A.; Nieuwdorp, M.; Fuentes, S.; Zoetendal, E.G.; de Vos, W.M.; Visser, C.E.; Kuijper, E.J.; Bartelsman, J.F.; Tijssen, J.G.; et al. Duodenal infusion of donor feces for recurrent Clostridium difficile. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alukal, J.; Dutta, S.K.; Surapaneni, B.K.; Le, M.; Tabbaa, O.; Phillips, L.; Mattar, M.C. Safety and efficacy of fecal microbiota transplant in 9 critically ill patients with severe and complicated Clostridium difficile infection with impending colectomy. J. Dig. Dis. 2019, 20, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wurm, P.; Spindelboeck, W.; Krause, R.; Plank, J.; Fuchs, G.; Bashir, M.; Petritsch, W.; Halwachs, B.; Langner, C.; Hogenauer, C.; et al. Antibiotic-Associated Apoptotic Enterocolitis in the Absence of a Defined Pathogen: The Role of Intestinal Microbiota Depletion. Crit. Care Med. 2017, 45, e600–e606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wang, C.; Tang, C.; He, Q.; Zhao, X.; Li, N.; Li, J. Successful treatment of severe sepsis and diarrhea after vagotomy utilizing fecal microbiota transplantation: A case report. Crit. Care 2015, 19, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Y.; Yang, J.; Wang, J.; Yang, Y.; Huang, J.; Gong, H.; Cui, H.; Chen, D. Successful treatment with fecal microbiota transplantation in patients with multiple organ dysfunction syndrome and diarrhea following severe sepsis. Crit. Care 2016, 20, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, M.; Liu, Y.; Chen, W.; Buch, H.; Shan, Y.; Chang, L.; Bai, Y.; Shen, C.; Zhang, X.; Huo, Y.; et al. Rescue fecal microbiota transplantation for antibiotic-associated diarrhea in critically ill patients. Crit. Care 2019, 23, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurczynski, S.J.; Lipinski, J.H.; Strauss, J.; Alam, S.; Huffnagle, G.B.; Ranjan, P.; Kennedy, L.H.; Moore, B.B.; O’Dwyer, D.N. Horizontal transmission of gut microbiota attenuates mortality in lung fibrosis. JCI Insight 2023, 9, e164572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Peng, L.; Wang, Z.; Lan, X.; Yu, S.; Yang, Y. Fecal microbiota transplantation significantly improved respiratory failure of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2353396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, S.L.; Gold, M.J.; Reynolds, L.A.; Willing, B.P.; Dimitriu, P.; Thorson, L.; Redpath, S.A.; Perona-Wright, G.; Blanchet, M.R.; Mohn, W.W.; et al. Perinatal antibiotic-induced shifts in gut microbiota have differential effects on inflammatory lung diseases. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2015, 135, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negi, S.; Pahari, S.; Bashir, H.; Agrewala, J.N. Gut Microbiota Regulates Mincle Mediated Activation of Lung Dendritic Cells to Protect Against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheffold, A.; Bacher, P. Anti-fungal T cell responses in the lung and modulation by the gut-lung axis. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2020, 56, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enaud, R.; Prevel, R.; Ciarlo, E.; Beaufils, F.; Wieers, G.; Guery, B.; Delhaes, L. The Gut-Lung Axis in Health and Respiratory Diseases: A Place for Inter-Organ and Inter-Kingdom Crosstalks. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winglee, K.; Eloe-Fadrosh, E.; Gupta, S.; Guo, H.; Fraser, C.; Bishai, W. Aerosol Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection causes rapid loss of diversity in gut microbiota. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e97048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wypych, T.P.; Wickramasinghe, L.C.; Marsland, B.J. The influence of the microbiome on respiratory health. Nat. Immunol. 2019, 20, 1279–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsland, B.J.; Trompette, A.; Gollwitzer, E.S. The Gut-Lung Axis in Respiratory Disease. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2015, 12 (Suppl. S2), S150–S156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziaka, M.; Exadaktylos, A. Pathophysiology of acute lung injury in patients with acute brain injury: The triple-hit hypothesis. Crit. Care 2024, 28, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, S.; Lin, F.; Hu, X.; Pan, P. Gut Microbiome-Based Therapeutics in Critically Ill Adult Patients-A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ney, L.M.; Wipplinger, M.; Grossmann, M.; Engert, N.; Wegner, V.D.; Mosig, A.S. Short chain fatty acids: Key regulators of the local and systemic immune response in inflammatory diseases and infections. Open Biol. 2023, 13, 230014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golpour, F.; Abbasi-Alaei, M.; Babaei, F.; Mirzababaei, M.; Parvardeh, S.; Mohammadi, G.; Nassiri-Asl, M. Short chain fatty acids, a possible treatment option for autoimmune diseases. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 163, 114763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, M.I.; Cryan, J.F.; Dinan, T.G. Man and the Microbiome: A New Theory of Everything? Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2019, 15, 371–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosang, L.; Canals, R.C.; van der Flier, F.J.; Hollensteiner, J.; Daniel, R.; Flugel, A.; Odoardi, F. The lung microbiome regulates brain autoimmunity. Nature 2022, 603, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaborin, A.; Smith, D.; Garfield, K.; Quensen, J.; Shakhsheer, B.; Kade, M.; Tirrell, M.; Tiedje, J.; Gilbert, J.A.; Zaborina, O.; et al. Membership and behavior of ultra-low-diversity pathogen communities present in the gut of humans during prolonged critical illness. mBio 2014, 5, e01361-14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, D.; Ackermann, G.; Khailova, L.; Baird, C.; Heyland, D.; Kozar, R.; Lemieux, M.; Derenski, K.; King, J.; Vis-Kampen, C.; et al. Extreme Dysbiosis of the Microbiome in Critical Illness. mSphere 2016, 1, 10-1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alverdy, J.C.; Chang, E.B. The re-emerging role of the intestinal microflora in critical illness and inflammation: Why the gut hypothesis of sepsis syndrome will not go away. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2008, 83, 461–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latorre, M.; Krishnareddy, S.; Freedberg, D.E. Microbiome as mediator: Do systemic infections start in the gut? World J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 21, 10487–10492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klingensmith, N.J.; Coopersmith, C.M. The Gut as the Motor of Multiple Organ Dysfunction in Critical Illness. Crit. Care Clin. 2016, 32, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Lu, X.; Ling, L.; Li, H.; Ou, Y.; Shi, X.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, D. Houttuynia cordata polysaccharides ameliorate pneumonia severity and intestinal injury in mice with influenza virus infection. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018, 218, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, M.; Klingensmith, N.J.; Coopersmith, C.M. New insights into the gut as the driver of critical illness and organ failure. Curr. Opin. Crit. Care 2017, 23, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hara, A.M.; Shanahan, F. The gut flora as a forgotten organ. EMBO Rep. 2006, 7, 688–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gavzy, S.J.; Kensiski, A.; Lee, Z.L.; Mongodin, E.F.; Ma, B.; Bromberg, J.S. Bifidobacterium mechanisms of immune modulation and tolerance. Gut Microbes 2023, 15, 2291164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leylabadlo, H.E.; Ghotaslou, R.; Feizabadi, M.M.; Farajnia, S.; Moaddab, S.Y.; Ganbarov, K.; Khodadadi, E.; Tanomand, A.; Sheykhsaran, E.; Yousefi, B.; et al. The critical role of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii in human health: An overview. Microb. Pathog. 2020, 149, 104344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoseph, B.P.; Klingensmith, N.J.; Liang, Z.; Breed, E.R.; Burd, E.M.; Mittal, R.; Dominguez, J.A.; Petrie, B.; Ford, M.L.; Coopersmith, C.M. Mechanisms of Intestinal Barrier Dysfunction in Sepsis. Shock 2016, 46, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Liao, Y. Gut-Lung Crosstalk in Sepsis-Induced Acute Lung Injury. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 779620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, C.; Liu, X.; Li, N.; Li, J. Disruption of tight junctions during polymicrobial sepsis in vivo. J. Pathol. 2009, 218, 210–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunzel, D. Claudins: Vital partners in transcellular and paracellular transport coupling. Pflugers Arch. 2017, 469, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lankelma, J.M.; van Vught, L.A.; Belzer, C.; Schultz, M.J.; van der Poll, T.; de Vos, W.M.; Wiersinga, W.J. Critically ill patients demonstrate large interpersonal variation in intestinal microbiota dysregulation: A pilot study. Intensive Care Med. 2017, 43, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Chang, G.; Huang, J.; Wang, Y.; Ma, N.; Roy, A.C.; Shen, X. Sodium Butyrate Inhibits the Inflammation of Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Acute Lung Injury in Mice by Regulating the Toll-Like Receptor 4/Nuclear Factor kappaB Signaling Pathway. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 1674–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Li, J.; Liu, Y.; Xiao, N.; Suo, H.; Xie, K.; Yang, C.; Wu, C. Short-chain fatty acids suppress lipopolysaccharide-induced production of nitric oxide and proinflammatory cytokines through inhibition of NF-kappaB pathway in RAW264.7 cells. Inflammation 2012, 35, 1676–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; van Esch, B.; Wagenaar, G.T.M.; Garssen, J.; Folkerts, G.; Henricks, P.A.J. Pro- and anti-inflammatory effects of short chain fatty acids on immune and endothelial cells. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2018, 831, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, J.; Wang, S.; Xia, H.; Han, S.; Wang, Q.; Wu, Z.; Zhuge, A.; Li, S.; Chen, H.; Lv, L.; et al. Akkermansia muciniphila attenuated lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury by modulating the gut microbiota and SCFAs in mice. Food Funct. 2023, 14, 10401–10417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panzer, A.R.; Lynch, S.V.; Langelier, C.; Christie, J.D.; McCauley, K.; Nelson, M.; Cheung, C.K.; Benowitz, N.L.; Cohen, M.J.; Calfee, C.S. Lung Microbiota is Related to Smoking Status and to Development of Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome in Critically Ill Trauma Patients. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2018, 197, 621–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S.; Hanidziar, D. More of the Gut in the Lung: How Two Microbiomes Meet in ARDS. Yale J. Biol. Med. 2018, 91, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Yang, X.; Chatterjee, V.; Wu, M.H.; Yuan, S.Y. The Gut-Lung Axis in Systemic Inflammation. Role of Mesenteric Lymph as a Conduit. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2021, 64, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauche, D.; Joyce-Shaikh, B.; Fong, J.; Villarino, A.V.; Ku, K.S.; Jain, R.; Lee, Y.C.; Annamalai, L.; Yearley, J.H.; Cua, D.J. IL-23 and IL-2 activation of STAT5 is required for optimal IL-22 production in ILC3s during colitis. Sci. Immunol. 2020, 5, eaav1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eladham, M.W.; Selvakumar, B.; Saheb Sharif-Askari, N.; Saheb Sharif-Askari, F.; Ibrahim, S.M.; Halwani, R. Unraveling the gut-Lung axis: Exploring complex mechanisms in disease interplay. Heliyon 2024, 10, e24032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Kwon, J.E.; Cho, M.L. Immunological pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Intest. Res. 2018, 16, 26–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birring, S.S.; Brightling, C.E.; Symon, F.A.; Barlow, S.G.; Wardlaw, A.J.; Pavord, I.D. Idiopathic chronic cough: Association with organ specific autoimmune disease and bronchoalveolar lymphocytosis. Thorax 2003, 58, 1066–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delgado Jimenez, R.; Benakis, C. The Gut Ecosystem: A Critical Player in Stroke. Neuromolecular Med. 2021, 23, 236–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R.; Qiao, S.; Yang, X. Th17/Treg Imbalance: Implications in Lung Inflammatory Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Stone, C.R.; Elkin, K.; Geng, X.; Ding, Y. Immunosuppression and Neuroinflammation in Stroke Pathobiology. Exp. Neurobiol. 2021, 30, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chhor, V.; Moretti, R.; Le Charpentier, T.; Sigaut, S.; Lebon, S.; Schwendimann, L.; Ore, M.V.; Zuiani, C.; Milan, V.; Josserand, J.; et al. Role of microglia in a mouse model of paediatric traumatic brain injury. Brain Behav. Immun. 2017, 63, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, M.; Chu, J.; Feng, S.; Guo, C.; Xue, B.; He, K.; Li, L. Immunological mechanisms of inflammatory diseases caused by gut microbiota dysbiosis: A review. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 164, 114985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; Roth, S.; Llovera, G.; Sadler, R.; Garzetti, D.; Stecher, B.; Dichgans, M.; Liesz, A. Microbiota Dysbiosis Controls the Neuroinflammatory Response after Stroke. J. Neurosci. 2016, 36, 7428–7440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessein, R.; Bauduin, M.; Grandjean, T.; Le Guern, R.; Figeac, M.; Beury, D.; Faure, K.; Faveeuw, C.; Guery, B.; Gosset, P.; et al. Antibiotic-related gut dysbiosis induces lung immunodepression and worsens lung infection in mice. Crit. Care 2020, 24, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Bai, C.; Hu, T.; Luo, C.; Yu, H.; Ma, X.; Liu, T.; Gu, X. Emerging trends and hotspot in gut-lung axis research from 2011 to 2021: A bibliometrics analysis. Biomed. Eng. OnLine 2022, 21, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otani, S.; Coopersmith, C.M. Gut integrity in critical illness. J. Intensive Care 2019, 7, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deitch, E.A. Gut lymph and lymphatics: A source of factors leading to organ injury and dysfunction. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2010, 1207 (Suppl. S1), E103–E111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, E.E. Claude H. Organ, Jr. Memorial Lecture: Splanchnic hypoperfusion provokes acute lung injury via a 5-lipoxygenase–dependent mechanism. Am. J. Surg. 2010, 200, 681–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, K.; Ogura, H.; Hamasaki, T.; Goto, M.; Tasaki, O.; Asahara, T.; Nomoto, K.; Morotomi, M.; Matsushima, A.; Kuwagata, Y.; et al. Altered gut flora are associated with septic complications and death in critically ill patients with systemic inflammatory response syndrome. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2011, 56, 1171–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madan, J.C.; Salari, R.C.; Saxena, D.; Davidson, L.; O’Toole, G.A.; Moore, J.H.; Sogin, M.L.; Foster, J.A.; Edwards, W.H.; Palumbo, P.; et al. Gut microbial colonisation in premature neonates predicts neonatal sepsis. Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2012, 97, F456–F462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, K.; Ogura, H.; Goto, M.; Asahara, T.; Nomoto, K.; Morotomi, M.; Yoshiya, K.; Matsushima, A.; Sumi, Y.; Kuwagata, Y.; et al. Altered gut flora and environment in patients with severe SIRS. J. Trauma. 2006, 60, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, R.; Tan, C.; Zhu, J.; Zeng, X.; Gao, X.; Wu, Q.; Chen, Q.; Wang, H.; Zhou, H.; He, Y.; et al. Dysbiosis of the intestinal microbiota in neurocritically ill patients and the risk for death. Crit. Care 2019, 23, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agudelo-Ochoa, G.M.; Valdes-Duque, B.E.; Giraldo-Giraldo, N.A.; Jaillier-Ramirez, A.M.; Giraldo-Villa, A.; Acevedo-Castano, I.; Yepes-Molina, M.A.; Barbosa-Barbosa, J.; Benitez-Paez, A. Gut microbiota profiles in critically ill patients, potential biomarkers and risk variables for sepsis. Gut Microbes 2020, 12, 1707610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.W.; Lu, J.L.; Dong, B.Y.; Fang, M.Y.; Xiong, X.; Qin, X.J.; Fan, X.M. Gut microbiota and its metabolic products in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1330021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Han, Z.; Zhou, R.; Su, W.; Gong, L.; Yang, Z.; Song, X.; Zhang, S.; Shu, H.; Wu, D. Altered gut microbiota in the early stage of acute pancreatitis were related to the occurrence of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1127369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, T.; Zhang, F.; Lui, G.C.Y.; Yeoh, Y.K.; Li, A.Y.L.; Zhan, H.; Wan, Y.; Chung, A.C.K.; Cheung, C.P.; Chen, N.; et al. Alterations in Gut Microbiota of Patients With COVID-19 During Time of Hospitalization. Gastroenterology 2020, 159, 944–955 e948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeoh, Y.K.; Zuo, T.; Lui, G.C.; Zhang, F.; Liu, Q.; Li, A.Y.; Chung, A.C.; Cheung, C.P.; Tso, E.Y.; Fung, K.S.; et al. Gut microbiota composition reflects disease severity and dysfunctional immune responses in patients with COVID-19. Gut 2021, 70, 698–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdes-Duque, B.E.; Giraldo-Giraldo, N.A.; Jaillier-Ramirez, A.M.; Giraldo-Villa, A.; Acevedo-Castano, I.; Yepes-Molina, M.A.; Barbosa-Barbosa, J.; Barrera-Causil, C.J.; Agudelo-Ochoa, G.M. Stool Short-Chain Fatty Acids in Critically Ill Patients with Sepsis. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2020, 39, 706–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamer, H.M.; Jonkers, D.; Venema, K.; Vanhoutvin, S.; Troost, F.J.; Brummer, R.J. Review article: The role of butyrate on colonic function. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2008, 27, 104–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, K.; Ogura, H.; Asahara, T.; Nomoto, K.; Morotomi, M.; Tasaki, O.; Matsushima, A.; Kuwagata, Y.; Shimazu, T.; Sugimoto, H. Probiotic/synbiotic therapy for treating critically ill patients from a gut microbiota perspective. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2013, 58, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osuka, A.; Shimizu, K.; Ogura, H.; Tasaki, O.; Hamasaki, T.; Asahara, T.; Nomoto, K.; Morotomi, M.; Kuwagata, Y.; Shimazu, T. Prognostic impact of fecal pH in critically ill patients. Crit. Care 2012, 16, R119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wozniak, H.; Beckmann, T.S.; Frohlich, L.; Soccorsi, T.; Le Terrier, C.; de Watteville, A.; Schrenzel, J.; Heidegger, C.P. The central and biodynamic role of gut microbiota in critically ill patients. Crit. Care 2022, 26, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Honda, K.; Littman, D.R. The microbiota in adaptive immune homeostasis and disease. Nature 2016, 535, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajilic-Stojanovic, M.; de Vos, W.M. The first 1000 cultured species of the human gastrointestinal microbiota. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2014, 38, 996–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, M.M.; Appelberg, O.; Reintam-Blaser, A.; Ichai, C.; Joannes-Boyau, O.; Casaer, M.; Schaller, S.J.; Gunst, J.; Starkopf, J.; ESICM-MEN Section. Prevalence of hypophosphatemia in the ICU—Results of an international one-day point prevalence survey. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 3615–3621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karczewski, J.; Poniedzialek, B.; Adamski, Z.; Rzymski, P. The effects of the microbiota on the host immune system. Autoimmunity 2014, 47, 494–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, A.; De Vadder, F.; Kovatcheva-Datchary, P.; Backhed, F. From Dietary Fiber to Host Physiology: Short-Chain Fatty Acids as Key Bacterial Metabolites. Cell 2016, 165, 1332–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, I.; Ichimura, A.; Ohue-Kitano, R.; Igarashi, M. Free Fatty Acid Receptors in Health and Disease. Physiol. Rev. 2020, 100, 171–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Vincenzo, F.; Del Gaudio, A.; Petito, V.; Lopetuso, L.R.; Scaldaferri, F. Gut microbiota, intestinal permeability, and systemic inflammation: A narrative review. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2024, 19, 275–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huffnagle, G.B.; Dickson, R.P.; Lukacs, N.W. The respiratory tract microbiome and lung inflammation: A two-way street. Mucosal Immunol. 2017, 10, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickson, R.P.; Erb-Downward, J.R.; Martinez, F.J.; Huffnagle, G.B. The Microbiome and the Respiratory Tract. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2016, 78, 481–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moffatt, M.F.; Cookson, W.O. The lung microbiome in health and disease. Clin. Med. 2017, 17, 525–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsay, J.J.; Wu, B.G.; Badri, M.H.; Clemente, J.C.; Shen, N.; Meyn, P.; Li, Y.; Yie, T.A.; Lhakhang, T.; Olsen, E.; et al. Airway Microbiota is Associated with Upregulation of the PI3K Pathway in Lung Cancer. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2018, 198, 1188–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gustafson, A.M.; Soldi, R.; Anderlind, C.; Scholand, M.B.; Qian, J.; Zhang, X.; Cooper, K.; Walker, D.; McWilliams, A.; Liu, G.; et al. Airway PI3K pathway activation is an early and reversible event in lung cancer development. Sci. Transl. Med. 2010, 2, 26ra25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandler, N.G.; Douek, D.C. Microbial translocation in HIV infection: Causes, consequences and treatment opportunities. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2012, 10, 655–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balzan, S.; de Almeida Quadros, C.; de Cleva, R.; Zilberstein, B.; Cecconello, I. Bacterial translocation: Overview of mechanisms and clinical impact. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2007, 22, 464–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, R.P.; Schultz, M.J.; van der Poll, T.; Schouten, L.R.; Falkowski, N.R.; Luth, J.E.; Sjoding, M.W.; Brown, C.A.; Chanderraj, R.; Huffnagle, G.B.; et al. Lung Microbiota Predict Clinical Outcomes in Critically Ill Patients. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 201, 555–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, F.C.F.; Lipinski, A.; Hofer, S.; Uhle, F.; Nusshag, C.; Hackert, T.; Dalpke, A.H.; Weigand, M.A.; Brenner, T.; Boutin, S. Pulmonary microbiome patterns correlate with the course of the disease in patients with sepsis-induced ARDS following major abdominal surgery. J. Hosp. Infect. 2020, 105, 438–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, N.; Zheng, B.; Yao, J.; Guo, L.; Zuo, J.; Wu, L.; Zhou, J.; Liu, L.; Guo, J.; Ni, S.; et al. Influence of H7N9 virus infection and associated treatment on human gut microbiota. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 14771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, S.; Chen, Y.; Wu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Gao, H.; Lv, L.; Guo, F.; Zhang, X.; Luo, R.; Huang, C.; et al. Alterations of the Gut Microbiota in Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 or H1N1 Influenza. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 71, 2669–2678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, M.; Lu, F.; Yu, D.; Wang, Y.; Chen, P.; Liu, S. Respiratory diseases and gut microbiota: Relevance, pathogenesis, and treatment. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1358597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.L.; Liang, J.; Lin, S.Z.; Xie, Y.W.; Ke, C.H.; Ao, D.; Lu, J.; Chen, X.M.; He, Y.Z.; Liu, X.H.; et al. Gut-lung axis and asthma: A historical review on mechanism and future perspective. Clin. Transl. Allergy 2024, 14, e12356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, H.C.; Lin, T.L.; Chen, T.W.; Kuo, Y.L.; Chang, C.J.; Wu, T.R.; Shu, C.C.; Tsai, Y.H.; Swift, S.; Lu, C.C. Gut microbiota modulates COPD pathogenesis: Role of anti-inflammatory Parabacteroides goldsteinii lipopolysaccharide. Gut 2022, 71, 309–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wu, K.; Shi, C.; Li, G. Cancer Immunotherapy: Fecal Microbiota Transplantation Brings Light. Curr. Treat. Options Oncol. 2022, 23, 1777–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Y.O.; Lee, S.H.; Choi, J.J.; Kim, D.H.; Choi, J.M.; Kang, M.J.; Oh, Y.M.; Park, Y.J.; Shin, Y.; Lee, S.W. Fecal microbial transplantation and a high fiber diet attenuates emphysema development by suppressing inflammation and apoptosis. Exp. Mol. Med. 2020, 52, 1128–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.; Qiu, R.; Zhou, J.; Ren, L.; Qu, Y.; Zhang, G. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation Alleviates Airway Inflammation in Asthmatic Rats by Increasing the Level of Short-Chain Fatty Acids in the Intestine. Inflammation 2025, 48, 1538–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, P.; Xu, Y.; Ye, S.; Yang, F.; Wu, L.; Su, G.; Liu, Y.; Feng, J.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Z.; et al. A preliminary study on the effects of fecal microbiota transplantation on the intestinal microecology of patients with severe pneumonia during the convalescence period. Zhonghua Wei Zhong Bing Ji Jiu Yi Xue 2023, 35, 352–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, L.; You, Y.; Zeng, S.; Yu, Z.; Wang, H.; Chen, M.; Wen, W. Fecal microbiota transplantation in severe pneumonia: A case report on overcoming pan-drug resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae infection. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1451751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Dong, B.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zeng, W.; Liao, L.; Xiong, X.; Qin, X.; Fan, X. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation Modulates Th17/Treg Balance via JAK/STAT Pathway in ARDS Rats. Adv. Biol. 2025, 9, e00028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cammarota, G.; Ianiro, G.; Tilg, H.; Rajilic-Stojanovic, M.; Kump, P.; Satokari, R.; Sokol, H.; Arkkila, P.; Pintus, C.; Hart, A.; et al. European consensus conference on faecal microbiota transplantation in clinical practice. Gut 2017, 66, 569–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopetuso, L.R.; Deleu, S.; Godny, L.; Petito, V.; Puca, P.; Facciotti, F.; Sokol, H.; Ianiro, G.; Masucci, L.; Abreu, M.; et al. The first international Rome consensus conference on gut microbiota and faecal microbiota transplantation in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut 2023, 72, 1642–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaines, S.; Alverdy, J.C. Fecal Micobiota Transplantation to Treat Sepsis of Unclear Etiology. Crit. Care Med. 2017, 45, 1106–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ianiro, G.; Maida, M.; Burisch, J.; Simonelli, C.; Hold, G.; Ventimiglia, M.; Gasbarrini, A.; Cammarota, G. Efficacy of different faecal microbiota transplantation protocols for Clostridium difficile infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 2018, 6, 1232–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quraishi, M.N.; Widlak, M.; Bhala, N.; Moore, D.; Price, M.; Sharma, N.; Iqbal, T.H. Systematic review with meta-analysis: The efficacy of faecal microbiota transplantation for the treatment of recurrent and refractory Clostridium difficile infection. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2017, 46, 479–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.L.; Chen, S.Z.; Xu, H.M.; Zhou, Y.L.; He, J.; Huang, H.L.; Xu, J.; Nie, Y.Q. Efficacy and safety of fecal microbiota transplantation for treating patients with ulcerative colitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Dig. Dis. 2020, 21, 534–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Xu, Y.; Wu, P.; Zhou, H.; Lasanajak, Y.; Fang, Y.; Tang, L.; Ye, L.; Li, X.; Cai, Z.; et al. Transplantation of fecal microbiota rich in short chain fatty acids and butyric acid treat cerebral ischemic stroke by regulating gut microbiota. Pharmacol. Res. 2019, 148, 104403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.W.; Adams, J.B.; Gregory, A.C.; Borody, T.; Chittick, L.; Fasano, A.; Khoruts, A.; Geis, E.; Maldonado, J.; McDonough-Means, S.; et al. Microbiota Transfer Therapy alters gut ecosystem and improves gastrointestinal and autism symptoms: An open-label study. Microbiome 2017, 5, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.W.; Adams, J.B.; Coleman, D.M.; Pollard, E.L.; Maldonado, J.; McDonough-Means, S.; Caporaso, J.G.; Krajmalnik-Brown, R. Long-term benefit of Microbiota Transfer Therapy on autism symptoms and gut microbiota. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 5821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheperjans, F.; Aho, V.; Pereira, P.A.; Koskinen, K.; Paulin, L.; Pekkonen, E.; Haapaniemi, E.; Kaakkola, S.; Eerola-Rautio, J.; Pohja, M.; et al. Gut microbiota are related to Parkinson’s disease and clinical phenotype. Mov. Disord. 2015, 30, 350–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boicean, A.; Neamtu, B.; Birsan, S.; Batar, F.; Tanasescu, C.; Dura, H.; Roman, M.D.; Hasegan, A.; Bratu, D.; Mihetiu, A.; et al. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation in Patients Co-Infected with SARS-CoV2 and Clostridioides difficile. Biomedicines 2022, 11, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Yin, G.F.; Wang, Y.L.; Tan, Y.M.; Huang, C.L.; Fan, X.M. Impact of fecal microbiota transplantation on TGF-beta1/Smads/ERK signaling pathway of endotoxic acute lung injury in rats. 3 Biotech 2020, 10, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Xu, L.; Zeng, Y.; Gong, F. Effect of gut microbiota on LPS-induced acute lung injury by regulating the TLR4/NF-kB signaling pathway. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2021, 91, 107272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Sun, L.; Yang, C.; Zhang, D.W.; Wei, Y.Y.; Yang, M.M.; Wu, H.M.; Fei, G.H. Gut microbiota-derived acetate attenuates lung injury induced by influenza infection via protecting airway tight junctions. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, G.F.; Li, B.; Fan, X.M. Effects and mechanism of fecal transplantation on acute lung injury induced by lipopolysaccharide in rats. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi 2019, 99, 1582–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hua, F.; Cui, E.; Lv, L.; Wang, B.; Li, L.; Lu, H.; Chen, N.; Chen, W. Fecal microbiota transplantation from HUC-MSC-treated mice alleviates acute lung injury in mice through anti-inflammation and gut microbiota modulation. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1243102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Zhang, Z.; Liao, L.; Dong, B.; Xiong, X.; Qin, X.; Fan, X. Impact of fecal microbiota transplantation on lung function and gut microbiome in an ARDS rat model: A multi-omics analysis including 16S rRNA sequencing, metabolomics, and transcriptomics. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2025, 39, 3946320251333982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, L.; Shi, L.; Kong, X.L.; Li, K.Y.; Li, H.; Jiang, D.X.; Zhang, F.; Zhou, Z.G. Gut Microbiota Protected Against pseudomonas aeruginosa Pneumonia via Restoring Treg/Th17 Balance and Metabolism. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 856633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, R.; Zhu, Q.; Wang, A.; Wang, H.; Wang, J.; Chen, P.; Zhang, R.; Liang, D.; Teng, J.; Ma, M.; et al. Effect of fecal microbiota transplantation on patients with sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. BMC Med. 2024, 22, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, W.; Peng, N.; Geng, Y. Fecal microbiota transplantation as salvage therapy for disseminated strongyloidiasis in an immunosuppressed patient: A case report. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1676906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Li, N.; Xing, H.; Guo, T.; Gong, H.; Chen, D. Effectiveness of fecal microbiota transplantation for severe diarrhea after drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome. Medicine 2019, 98, e18476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Wang, C.; Tang, C.; He, Q.; Zhao, X.; Li, N.; Li, J. Therapeutic modulation and reestablishment of the intestinal microbiota with fecal microbiota transplantation resolves sepsis and diarrhea in a patient. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 109, 1832–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gopalsamy, S.N.; Sherman, A.; Woodworth, M.H.; Lutgring, J.D.; Kraft, C.S. Fecal Microbiota Transplant for Multidrug-Resistant Organism Decolonization Administered During Septic Shock. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2018, 39, 490–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Y.; Gong, J.; Zhu, W.; Guo, D.; Gu, L.; Li, N.; Li, J. Fecal microbiota transplantation restores dysbiosis in patients with methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus enterocolitis. BMC Infect. Dis. 2015, 15, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueckermann, V.; Hoosien, E.; De Villiers, N.; Geldenhuys, J. Fecal Microbial Transplantation for the Treatment of Persistent Multidrug-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae Infection in a Critically Ill Patient. Case Rep. Infect. Dis. 2020, 2020, 8462659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcella, C.; Cui, B.; Kelly, C.R.; Ianiro, G.; Cammarota, G.; Zhang, F. Systematic review: The global incidence of faecal microbiota transplantation-related adverse events from 2000 to 2020. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021, 53, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shogbesan, O.; Poudel, D.R.; Victor, S.; Jehangir, A.; Fadahunsi, O.; Shogbesan, G.; Donato, A. A Systematic Review of the Efficacy and Safety of Fecal Microbiota Transplant for Clostridium difficile Infection in Immunocompromised Patients. Can. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 2018, 1394379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrieze, A.; de Groot, P.F.; Kootte, R.S.; Knaapen, M.; van Nood, E.; Nieuwdorp, M. Fecal transplant: A safe and sustainable clinical therapy for restoring intestinal microbial balance in human disease? Best. Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2013, 27, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Zuo, T.; Yeoh, Y.K.; Cheng, F.W.T.; Liu, Q.; Tang, W.; Cheung, K.C.Y.; Yang, K.; Cheung, C.P.; Mo, C.C.; et al. Longitudinal dynamics of gut bacteriome, mycobiome and virome after fecal microbiota transplantation in graft-versus-host disease. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broecker, F.; Klumpp, J.; Schuppler, M.; Russo, G.; Biedermann, L.; Hombach, M.; Rogler, G.; Moelling, K. Long-term changes of bacterial and viral compositions in the intestine of a recovered Clostridium difficile patient after fecal microbiota transplantation. Cold Spring Harb. Mol. Case Stud. 2016, 2, a000448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, N.D.; Crothers, J.W.; Nguyen, L.T.T.; Kearney, S.M.; Smith, M.B.; Kassam, Z.; Collins, C.; Xavier, R.; Moses, P.L.; Alm, E.J. Dynamic Colonization of Microbes and Their Functions after Fecal Microbiota Transplantation for Inflammatory Bowel Disease. mBio 2021, 12, e0097521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Garg, S.; Girotra, M.; Maddox, C.; von Rosenvinge, E.C.; Dutta, A.; Dutta, S.; Fricke, W.F. Microbiota dynamics in patients treated with fecal microbiota transplantation for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e81330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Liu, M.; Cao, J.; Li, X.; Fan, D.; Xia, Y.; Lu, X.; Li, J.; Ju, D.; Zhao, H. The Dynamic Interplay between the Gut Microbiota and Autoimmune Diseases. J. Immunol. Res. 2019, 2019, 7546047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliva-Hemker, M.; Kahn, S.A.; Steinbach, W.J. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation: Information for the Pediatrician. Pediatrics 2023, 152, e2023062922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Xu, M.; Wang, W.; Cao, X.; Piao, M.; Khan, S.; Yan, F.; Cao, H.; Wang, B. Systematic Review: Adverse Events of Fecal Microbiota Transplantation. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0161174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smillie, C.S.; Smith, M.B.; Friedman, J.; Cordero, O.X.; David, L.A.; Alm, E.J. Ecology drives a global network of gene exchange connecting the human microbiome. Nature 2011, 480, 241–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kassam, Z.; Lee, C.H.; Yuan, Y.; Hunt, R.H. Fecal microbiota transplantation for Clostridium difficile infection: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 108, 500–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeFilipp, Z.; Bloom, P.P.; Torres Soto, M.; Mansour, M.K.; Sater, M.R.A.; Huntley, M.H.; Turbett, S.; Chung, R.T.; Chen, Y.B.; Hohmann, E.L. Drug-resistant E. coli Bacteremia Transmitted by Fecal Microbiota Transplant. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 2043–2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, K.; Ulrichsen, J.U.; Westphal, A.N.; Iepsen, U.W.; Ronit, A.; Plovsing, R.R.; Berg, R.M.G. Composition and diversity of the pulmonary microbiome in acute respiratory distress syndrome: A systematic review. Crit. Care 2025, 29, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cibulkova, I.; Rehorova, V.; Hajer, J.; Duska, F. Fecal Microbial Transplantation in Critically Ill Patients-Structured Review and Perspectives. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruszkowski, J.; Kachlik, Z.; Walaszek, M.; Storman, D.; Podkowa, K.; Garbarczuk, P.; Jemiolo, P.; Lyzinska, W.; Nowakowska, K.; Grych, K.; et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation from patients into animals to establish human microbiota-associated animal models: A scoping review. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 23, 662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cibulkova, I.; Rehorova, V.; Soukupova, H.; Waldauf, P.; Cahova, M.; Manak, J.; Matejovic, M.; Duska, F. Allogenic faecal microbiota transplantation for antibiotic-associated diarrhoea in critically ill patients (FEBATRICE)-Study protocol for a multi-centre randomised controlled trial (phase II). PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0310180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soranno, D.E.; Coopersmith, C.M.; Brinkworth, J.F.; Factora, F.N.F.; Muntean, J.H.; Mythen, M.G.; Raphael, J.; Shaw, A.D.; Vachharajani, V.; Messer, J.S. A review of gut failure as a cause and consequence of critical illness. Crit. Care 2025, 29, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Liu, J.; Rhodes, C.; Nie, Y.; Zhang, F. Ethical Issues in Fecal Microbiota Transplantation in Practice. Am. J. Bioeth. 2017, 17, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziaka, M.; Exadaktylos, A. ARDS associated acute brain injury: From the lung to the brain. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2022, 27, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, J.E.; Davis, J.A.; Berk, M.; Hair, C.; Loughman, A.; Castle, D.; Athan, E.; Nierenberg, A.A.; Cryan, J.F.; Jacka, F.; et al. Efficacy and safety of fecal microbiota transplantation for the treatment of diseases other than Clostridium difficile infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut Microbes 2020, 12, 1854640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziaka, M.; Exadaktylos, A. Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome: Pathophysiological Insights, Subphenotypes, and Clinical Implications-A Comprehensive Review. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 5184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziaka, M.; Exadaktylos, A. Fluid management strategies in critically ill patients with ARDS: A narrative review. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2025, 30, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ziaka, M. Targeting Gut–Lung Crosstalk in Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome: Exploring the Therapeutic Potential of Fecal Microbiota Transplantation. Pathogens 2025, 14, 1206. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121206

Ziaka M. Targeting Gut–Lung Crosstalk in Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome: Exploring the Therapeutic Potential of Fecal Microbiota Transplantation. Pathogens. 2025; 14(12):1206. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121206

Chicago/Turabian StyleZiaka, Mairi. 2025. "Targeting Gut–Lung Crosstalk in Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome: Exploring the Therapeutic Potential of Fecal Microbiota Transplantation" Pathogens 14, no. 12: 1206. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121206

APA StyleZiaka, M. (2025). Targeting Gut–Lung Crosstalk in Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome: Exploring the Therapeutic Potential of Fecal Microbiota Transplantation. Pathogens, 14(12), 1206. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121206