Abstract

Autism spectrum disorder is markedly heterogeneous and frequently accompanied by gastrointestinal symptoms that often correlate with behavioral phenotypes. Emerging evidence suggests that the microbiota–gut–brain axis may contribute to these associations through multiple bidirectional communication routes—including neural, immune, and endocrine pathways, as well as microbial metabolites such as short-chain fatty acids and tryptophan–kynurenine intermediates. This narrative review synthesizes clinical, mechanistic, and interventional evidence published between January 2010 and July 2025, clarifies the extent to which current data support association versus causation, evaluates key confounding factors, summarizes evidence for interventions such as probiotics, prebiotics, and fecal microbiota transplantation, and outlines future directions for precision research and targeted interventions based on functional pathways and stratified subgroups.

1. Introduction

1.1. Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) Heterogeneity and Epidemiologic Challenges

ASD represents a highly heterogeneous neurodevelopmental condition characterized by persistent deficits in social communication and interaction, alongside restricted and repetitive behaviors, interests, or activities [1,2]. Its etiology is multifactorial: genetic susceptibility interacts with diverse environmental and biological influences, including immune–inflammatory pathways [3,4] and oxidative stress [5]. No single pathophysiological mechanism fully accounts for the marked phenotypic variability [6,7,8]. Epidemiologic surveillance over the past decade indicates a global rise in ASD prevalence, underscoring its public health significance [9]. Current interventions primarily alleviate symptoms and enhance functioning, while disease-modifying therapies remain unavailable [10,11]. Accordingly, identifying modifiable biological and environmental pathways that contribute to ASD-related phenotypes represents a critical research priority [12,13].

1.2. The Microbiota–Gut–Brain Axis (MGBA) Framework for Understanding ASD

The MGBA describes a bidirectional communication network between the gut and the central nervous system (CNS), mediated by intestinal microbiota [14,15]. This network operates through multiple interacting routes [16]: (1) neural—primarily via the vagus nerve (VN), enteric nervous system (ENS), and sympathetic nervous system (SNS); (2) immune—through innate and adaptive immune cells and cytokine signaling; (3) endocrine—via the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis; and (4) metabolic—through microbially derived metabolites such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) and tryptophan derivatives that can modulate glial activity and neural circuits. This framework offers a conceptual model for exploring how gut physiology may influence brain function and behavior. Nevertheless, current findings are largely correlational, providing mechanistic hypotheses rather than demonstrating causality [17].

1.3. Gastrointestinal Comorbidity in ASD: Prevalence and Clinical Correlates

Multiple studies indicate that gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms (e.g., constipation, diarrhea, abdominal pain, and bloating) are more prevalent among individuals with ASD [18,19,20]. Reported prevalence varies across studies due to differences in assessment tools, age groups, recruitment settings, and medication use, but meta-analyses estimate that roughly one-third of individuals with ASD are affected—significantly higher than in the general pediatric population [21]. The presence and severity of GI symptoms frequently correlate with greater social communication deficits, restricted and repetitive behaviors, anxiety, and sleep disturbances [22]. However, these associations remain correlational, and causal relationships are not yet established. This pattern highlights the MGBA as a potentially informative framework for investigating the biological underpinnings of ASD’s clinical heterogeneity [23].

2. Methods and Search Strategy

This article is a narrative review, structured with a systematic search strategy to ensure methodological transparency. The literature selection process was twofold:

First, a primary systematic search was conducted using the PubMed database for articles published in the modern era of MGBA research, defined as 1 January 2010, through 31 July 2025. The search utilized a keyword combination of (“Autism spectrum disorder”) AND (“Brain-Gut Axis” OR “Microbiota” OR “Metabolism” OR “Signs and Symptoms, Digestive”). This primary search identified 859 articles.

Second, to provide essential historical context, this systematic search was supplemented by an expert-driven identification of foundational, pre-2010 studies that were identified through the authors’ existing knowledge and citation tracking from key review articles.

The final set of 146 publications was curated from both the systematically identified pool (the 859 articles) and the supplemental foundational pool. The selection was guided by the following criteria. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) articles published in English; (2) original research (human or key mechanistic animal models) or review articles; (3) studies directly addressing the MGBA in the context of ASD; and (4) high relevance to the review’s core themes of mechanistic pathways, methodological challenges, causal inference, or therapeutic interventions. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) articles not relevant to the core themes; (2) editorials, letters, or case reports (unless highly illustrative); and (3) studies primarily focused on non-ASD conditions.

Figures were created with BioRender (www.biorender.com, accessed on 27 September 2025). The conceptual frameworks in Box 1 and Box 2 were designed by the authors. A generative AI assistant (ChatGPT 4.0) was used only for text refinement and formatting. The authors directed and verified all steps and take full responsibility for the scientific accuracy of the figures and boxes.

Box 1. Dissecting Bidirectional Causality: A Framework for Forward and Reverse Inference.

Establishing a robust causal link between the microbiota and ASD requires a framework that can not only validate the forward pathway (microbiome → ASD) but also rigorously assess the reverse pathway (ASD → microbiome), accounting for critical confounders like behavior and diet.

Part A: Validating the Microbiome → ASD Pathway (Forward Causality)

This three-step roadmap translates genetically prioritized signals into biologically validated mechanisms.

- Step 1: Prioritize Causal Candidates with MR and Colocalization.

- ○

- Action: Employ robust MR analyses and colocalization to identify microbial functions or metabolites with a putative causal link to ASD, ensuring shared genetic causality.

- ○

- Outcome: A high-confidence list of candidates for experimental validation.

- Step 2: Interrogate Mechanisms in Patient-Derived Functional Models.

- ○

- Action: Expose prioritized metabolites to patient-derived intestinal or BBB organoids.

- ○

- Outcome: Quantify key endpoints like barrier integrity (TEER, tight junctions) and immune activation (cytokine profiles) to establish biological plausibility.

- Step 3: Confirm Causality with Dose-Response and Time-Series Analyses.

- ○

- Action: Perform systematic dose-response and time-series experiments. Where feasible, use inhibitors for reverse validation.

- ○

- Outcome: Robust preclinical evidence of a specific, dose-dependent causal relationship.

Part B: Investigating the ASD → Microbiome Pathway (Reverse Causality)

This step is critical for disentangling whether microbial alterations are causes or consequences of ASD-related phenotypes.

- Action 1: Employ Bidirectional MR.

- ○

- Method: Use genetic instruments for ASD as the exposure and microbial features as the outcome. This formally tests the hypothesis that genetic liability for ASD causally influences the gut microbiome.

- ○

- Outcome: Genetic evidence for or against a causal effect of ASD on the microbiome, helping to untangle the direction of the primary association.

- Action 2: Implement Longitudinal and Cross-Lagged Models.

- ○

- Method: In prospective cohort studies, use advanced statistical models (e.g., cross-lagged panel models, linear mixed-effects models) to analyze the temporal interplay between ASD-related behaviors (e.g., changes in diet, medication use) and microbiome shifts over time.

- ○

- Outcome: A dynamic, longitudinal understanding of how ASD-related factors drive microbial changes, thereby statistically controlling for the confounding effects discussed throughout this review.

Box 2. Major Confounders and Practical Control Strategies in MGBA–ASD Research.

Dietary factors. Dietary selectivity and restricted food variety are common in ASD and strongly influence gut microbial composition. Future studies can apply structured 24 h dietary recalls or food-frequency questionnaires, with energy adjustment or macronutrient normalization, to mitigate dietary bias.

Medication exposure. Antibiotics, proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), and psychotropic medications can induce lasting shifts in gut microbial ecology. Recording medication history and applying stratified analyses—or incorporating medication washout periods where ethically feasible—can reduce pharmacological confounding.

Comorbidities. Gastrointestinal disorders, anxiety, and sleep disturbances frequently co-occur with ASD and may independently affect MGBA signaling. Sensitivity analyses that exclude or statistically adjust for these conditions help clarify independent microbiome–behavior associations.

Sample collection and processing. Variability in sampling time, dietary state (fasting vs. postprandial), and storage conditions introduces noise. Harmonized collection protocols—standardizing sampling timing, pre-sampling diet, and biospecimen handling—enhance reproducibility and cross-cohort comparability.

Overall, acknowledging and systematically addressing these confounders will strengthen causal inference and the translational reliability of MGBA-related findings in ASD research.

3. MGBA: Bidirectional Neurobiology

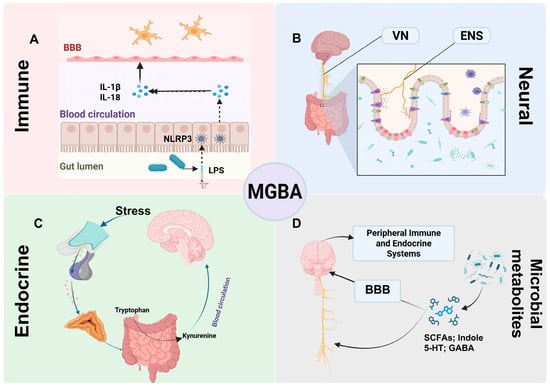

The MGBA encompasses four interacting modules—neural, immune, endocrine, and microbial metabolic—that communicate through systemic circulation and across the blood–brain barrier (BBB) (Figure 1) [16].

Figure 1.

Overview of bidirectional MGBA modules and their crosstalk. Flow Explanation: This schematic illustrates the four principal communication routes constituting the MGBA and their reciprocal interactions. (A) Immune module: Gut dysbiosis or external stimuli allow LPS to activate NLRP3 inflammasomes, promoting IL-1β/IL-18 release and BBB disruption, linking peripheral inflammation to neuroinflammation. (B) Neural module: The VN and ENS transmit microbial, hormonal, and immune signals from the gut to the brain, providing a rapid neural conduit for bidirectional regulation. (C) Endocrine module: Stress activates the HPA axis, altering tryptophan metabolism toward the kynurenine pathway, thereby influencing neuroimmune signaling. (D) Microbial metabolite module: Microbial products act through endocrine and immune routes or interact with the BBB to modulate neural and systemic homeostasis. Together, these interconnected pathways form a dynamic network through which gut microbes influence brain function and behavior, and vice versa. Abbreviations: MGBA, microbiota–gut–brain axis; BBB, blood–brain barrier; IL-1β, interleukin-1 beta; IL-18, interleukin-18; NLRP3, NLR family pyrin domain-containing 3 (inflammasome); LPS, lipopolysaccharide; VN, vagus nerve; ENS, enteric nervous system; SCFAs, short-chain fatty acids; 5-HT, 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin); GABA, γ-aminobutyric acid.

3.1. Immune: Barrier, Cytokines, and Neuroinflammation

Integrity of the intestinal barrier is essential for maintaining host–microbiota symbiosis and homeostasis [24]. When dysbiosis or external factors such as diet compromise this barrier, pathogen-associated molecular patterns, including lipopolysaccharide (LPS), can translocate across the mucosa into circulation, activating innate immune pathways such as the NLRP3 inflammasome and inducing interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and interleukin-18 (IL-18) release [25,26,27]. Systemic inflammation may subsequently disrupt BBB integrity through cytokine signaling and loss of endothelial tight junctions, thereby promoting neuroinflammation. Microglial activation and polarization are consistently reported in ASD models and human studies [28,29,30,31]. Recent evidence also implicates central NLRP3 activation in BBB dysfunction. In ASD, in vivo imaging and histological analyses reveal abnormal microglial activation [32]. Nonetheless, most evidence remains correlational and insufficient to infer causality [26,33,34].

3.2. Neural: A Rapid Conduit

Because the enteric (ENS) and sympathetic (SNS) nervous systems are less extensively studied, this section focuses on the VN. Among MGBA pathways, the VN provides the most rapid anatomical and physiological link between the gut and the CNS [35]. As the tenth cranial nerve and the main afferent–efferent branch of the parasympathetic system, the VN descends from the brainstem to the thoracoabdominal cavity, extensively innervating visceral organs, including the gastrointestinal tract [36]. Approximately 80% of its fibers are afferent, establishing a predominantly bottom-up flow of information from the gut to central nodes such as the nucleus tractus solitarius [37,38,39]. Peripheral VN terminals detect luminal and mucosal signals—including microbial metabolites, gut-derived hormones, and inflammatory mediators—and relay them to the brainstem–limbic–cortical network, modulating emotional and cognitive processing [35,37,40,41]. Classic animal studies demonstrate that Bifidobacterium longum NCC3001 induces anxiolytic-like effects in mice with chronic colitis, effects abolished after vagotomy, underscoring the VN’s role in microbiota-to-brain signaling [42,43]. The VN also regulates peripheral immunity via the cholinergic anti-inflammatory reflex and the sympathetic–splenic pathway, reinforcing its function as an integrative hub within the MGBA [44].

3.3. Endocrine: HPA Axis

The endocrine system connects stress and metabolic states to the MGBA through the HPA axis [45,46]. Stress-induced cortisol elevations upregulate the rate-limiting enzymes tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase (TDO) and indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO), shifting tryptophan metabolism toward the kynurenine pathway and reducing serotonin synthesis [47]. Kynurenine metabolites, in turn, modulate neuroimmune signaling and affective behaviors. Evidence from human and animal studies supports these mechanisms, though effect sizes and population variability remain to be clarified [48,49].

3.4. Systems Crosstalk: From Pathways to Metabolites

MGBA signaling operates through parallel, interconnected neural (vagal and enteric), immune (NLRP3–cytokine), endocrine (HPA), and metabolic (SCFAs and tryptophan–kynurenine) pathways. For instance, peripheral LPS-induced inflammation can alter the excitability of vagal nodose ganglion neurons [50,51]. Microbiota-derived metabolites are discussed in Section 3.

4. Microbial Metabolites: Regulatory Roles in Neural Function

Within the MGBA, microbial metabolites act as key mediators linking gut ecology with host physiology. Table 1 summarizes their major classes, representative sources, mechanisms, and effects on neural function. These metabolites influence the brain through multiple routes: some cross the BBB, others act on endothelial receptors, modulate peripheral immune or endocrine signaling, or affect brain networks via the vagus nerve. They reflect the functional state of the microbiota and represent potential intervention targets, although current evidence remains largely correlational and mechanistic.

Table 1.

Key microbiota-derived metabolites in the gut–brain axis and their mechanisms.

4.1. SCFAs: Gut-to-Brain Mediators

Short-chain fatty acids—mainly acetate, propionate, and butyrate—are produced by anaerobic fermentation of dietary fiber and resistant starch, and their levels can be modulated by altering the gut microbiota through probiotic intake [52,56,57,58,59]. Butyrate serves as a key energy source for colonic epithelial cells, upregulating tight-junction proteins (e.g., claudin, occludin) and maintaining barrier integrity [60], thereby limiting bacterial translocation into the circulation.

A subset of SCFAs crosses the BBB via monocarboxylate transporters [61,62], or acts on free fatty acid receptor 3 on brain endothelial cells [63,64,65], modulating BBB stress responses and permeability. Centrally, SCFAs regulate microglial maturation, homeostasis, and neuroinflammation [66]; butyrate additionally inhibits histone deacetylases [67,68,69] and is associated with increased brain-derived neurotrophic factor expression, synaptogenesis, and neurogenesis in preclinical models [52]. Overall, SCFAs link diet, microbiota, barrier function, and neural plasticity, representing intervention targets that require further validation in well-controlled human studies [70,71,72].

4.2. Neuroactive Compounds and Precursors

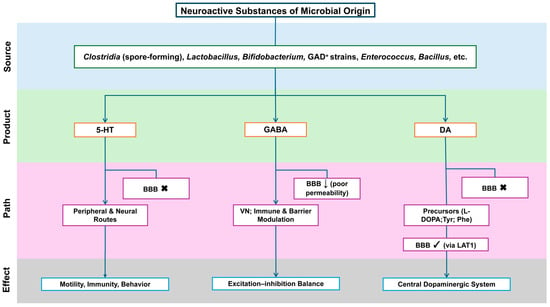

The gut microbiota both synthesizes neuroactive molecules and modulates their host production through substrate supply and metabolic regulation [39]. Figure 2 outlines key microbial sources, products, BBB permeability, and signaling routes.

Figure 2.

Neuroactive substances of microbial origin: sources, routes, and CNS reachability. Flow Explanation: The figure outlines the stepwise flow of microbial–neural interaction from origin to functional outcome. Specific gut bacterial taxa (Clostridia, Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, Enterococcus, Bacillus) generate neuroactive products such as 5-HT, GABA, and DA. These compounds differ in their permeability across the BBB and thus utilize distinct communication routes. 5-HT primarily acts through peripheral and vagal neural pathways to regulate motility and behavior, as it cannot cross the BBB. GABA has poor BBB permeability and therefore exerts its effects indirectly—through vagus nerve signaling, immune modulation, and barrier interactions—rather than direct diffusion into the brain. DA precursors (L-DOPA, Tyr, Phe) can traverse the BBB through LAT1, integrating into the central dopaminergic system. Collectively, these pathways illustrate how microbial metabolites—through neural, immune, and metabolic conduits—contribute to the MGBA implicated in ASD pathophysiology. Abbreviations: 5-HT, 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin); GABA, γ-aminobutyric acid; DA, dopamine; BBB, blood–brain barrier; CNS, central nervous system; VN, vagus nerve; L-DOPA, L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine; Tyr, tyrosine; Phe, phenylalanine; LAT1, L-type amino acid transporter 1; GAD+, glutamate decarboxylase–positive (GABA-producing) strains. Symbols: “×”, cannot cross the BBB; “↓”, low BBB permeability; “√”, BBB-permeant (via LAT1 where indicated).

Serotonin (5-HT). About 90–95% of total 5-HT is synthesized by intestinal enterochromaffin (EC) cells, and peripheral 5-HT does not cross the BBB. Spore-forming microbes promote gut-derived 5-HT synthesis and release by regulating EC cells, influencing motility, immunity, and behavior through peripheral and neural pathways [73,74,75,76,77].

γ-Aminobutyric acid (GABA). Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, and some Bacteroides produce GABA, whose central effects are likely mediated indirectly—via the vagus nerve, immune signaling, or barrier modulation—rather than by direct BBB passage [78].

Glutamate and dopamine-related signaling. Certain strains convert glutamate to GABA, shaping the peripheral substrate balance between excitation and inhibition. Peripheral dopamine poorly crosses the BBB, but its precursors—levodopa (L-DOPA) and large neutral amino acids (tyrosine, phenylalanine)—enter via large neutral amino acid transporter 1 (LAT1), influencing central dopaminergic activity [79,80].

From an interventional standpoint, targeting measurable metabolites or pathways may be more practical than manipulating the microbiota as a whole—for example, enhancing SCFA production through fiber intake or modulating 5-HT precursor availability via strain selection and nutrition. These approaches remain under study, and no definitive human evidence yet supports their efficacy for core ASD symptoms [16].

4.3. Tryptophan Metabolism: Imbalance and Neuroinflammation

Tryptophan is metabolized through three main routes: the serotonin, kynurenine (KYN), and indole pathways [47]. Inflammation-induced activation of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) and tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase (TDO) shifts metabolism toward the KYN pathway, generating metabolites such as quinolinic acid and KYN, which exert N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor-related neurotoxic and immunomodulatory effects [47,81].

In ASD, peripheral tryptophan (TRP), KYN levels, and their ratios (e.g., KYN/TRP) show inconsistent findings. Although some studies report KYN-pathway activation alongside low-grade inflammation, recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses have not confirmed consistent alterations in peripheral TRP metabolism or tryptophan catabolites. Thus, KYN-pathway imbalance remains a plausible but non-universal mechanism, potentially amplifying gut–immune–brain signaling in subsets of individuals [81,82,83].

5. MGBA Dysregulation in ASD: Clinical Relevance and Pathophysiology

5.1. Dysbiosis in ASD: Evidence, Confounders, and Variability

Many studies report gut microbiota differences between individuals with ASD and neurotypical controls [2], yet cross-study consistency remains limited. Some cohorts note phylum- or genus-level shifts—such as altered Firmicutes-to-Bacteroidetes ratios [84] and increased Proteobacteria or Sutterella—while others fail to replicate these patterns [2,85]. No single, universal “ASD microbiome signature” has been identified [86], and results depend heavily on sample source and methodology [87,88,89]. Table 2 summarizes taxa-level findings in ASD, highlighting recurrent trends, inconsistent results, and key confounders across studies.

Table 2.

Gut microbiota changes in ASD: summary of consistent and inconsistent findings.

Drivers of divergence include:

- (1)

- Clinical and behavioral heterogeneity: ASD phenotypes and the spectrum of GI comorbidities vary widely, with pronounced subgroup differences [53].

- (2)

- Lifestyle and confounding factors: notably restrictive diets and food selectivity, which can shape microbial differences and correlate with ASD features [86,89].

- (3)

- Sequencing and analytic variation: 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing versus whole-metagenome shotgun sequencing differ in taxonomic resolution and functional inference; batch effects, often addressed with tools like ComBat-Seq or RUV-III-NB, and statistical pipelines, which must account for the compositional nature of microbiome data using methods such as centered/additive log-ratio transformations, ANCOM-BC, or ALDEx2, further influence differential-abundance conclusions [89,106,107,108].

Against this backdrop, research focus is shifting from identifying specific taxa toward mapping functional pathways and metabolic networks. Multi-omics integration suggests that reproducible ASD-associated signals often involve amino acid, carbohydrate, and lipid metabolism, correlating with host transcriptomic and dietary profiles. These findings are largely correlational and remain mechanistic rather than causal [108].

Large-scale, multi-domain metagenomic studies employing machine learning have identified discriminative microbial and functional features—spanning bacteria, archaea, fungi, viruses, and pathways—with within-cohort classification AUCs up to ~0.9. However, external validation, cross-cohort reproducibility, and clinical translation remain major challenges [109].

5.2. Barrier Disruption and Neuroimmune Activation

Dysbiosis and impaired epithelial or BBB integrity are candidate mechanisms linking gut and brain in ASD. Loss of mucosal homeostasis allows translocation of bacterial components (e.g., LPS) and metabolites (e.g., p-cresol) into the circulation, eliciting systemic inflammation that can influence BBB permeability and central immune activity [110]. Elevated urinary p-cresol has been repeatedly reported, though its causality and diagnostic value remain uncertain [111].

A Neuroimaging and biofluid studies further indicate neuroimmune activation: increased 18-kDa translocator protein binding and higher inflammatory mediators in cerebrospinal fluid have been observed, albeit inconsistently and with limited specificity [112,113,114].

Collectively, these findings support a plausible cascade—gut inflammation → barrier dysfunction → systemic cytokines → BBB alteration → glial activation—potentially linking gastrointestinal and behavioral phenotypes in subsets of individuals with ASD. Prospective, controlled studies integrating dietary, pharmacologic, and omic variables are required to determine causality and modifiability [108].

6. From Correlation to Causation: Methodological Challenges and Emerging Advances

6.1. Core Challenge: Correlation Is Not Causation

Current evidence consistently demonstrates associations among ASD, gut microbiota composition, gastrointestinal symptoms, and behavioral phenotypes. Yet, most studies are cross-sectional or retrospective and therefore cannot infer causality [75]. A central confounder is selective and hypersensitive eating: many children with ASD exhibit sensory aversions to taste, texture, and smell, leading to restricted diets and nutrient imbalances [53]. Such dietary patterns alone can reshape gut microbial and metabolic profiles [86]. Hence, observed microbial alterations may reflect secondary effects rather than etiologic drivers. Robust causal inference will require designs that rigorously control for diet, medication use, and comorbidities [89,115].

6.2. Mendelian Randomization (MR) and Multi-Omics Integration

MR uses genetic variants robustly associated with an exposure (e.g., microbial taxa or functions) as instrumental variables to infer causal effects under specific assumptions, thereby mitigating confounding and reverse causation [116,117]. Recent two-sample and bidirectional MR analyses have reported directional links between selected taxa (e.g., Turicibacter, Prevotellaceae) and ASD, although directions and effect sizes remain inconsistent across studies; some even suggest potentially protective associations [117]. These findings are constrained by weak instruments in microbiome GWAS, horizontal pleiotropy, and sample overlap, necessitating sensitivity analyses (e.g., weighted median, MR-Egger regression, MR-PRESSO, Steiger tests) and colocalization to reduce bias. Overall, MR currently offers preliminary genetic evidence rather than definitive causal proof [117,118].

Multi-omics integration—including metagenomics, transcriptomics, metabolomics, and host phenotypic data—shifts focus from individual taxa to functional pathways [108]. Large-scale integrative studies highlight alterations in amino acid, carbohydrate, and lipid metabolism, correlating with host brain-region transcriptomic profiles and dietary diversity [108]. However, these associations remain primarily correlational and require prospective and interventional validation.

Emerging analytical frameworks such as two-step mediation MR can decompose putative causal chains (e.g., “microbiota → circulating metabolite → ASD”), while reverse MR (“ASD → microbiota”) helps assess bidirectionality and mediation, informing mechanistic targeting of metabolic and dietary pathways [119].

A credible research trajectory would therefore include: (i) prospective cohorts with harmonized data on diet, medication, and behavior analyzed using longitudinal and cross-lagged models; (ii) multivariable MR with colocalization and multi-omics integration to prioritize causal pathways; and (iii) interventional validation through randomized controlled trials (RCTs) enhancing dietary diversity or targeting metabolites and pathways—explicitly accounting for the bidirectional gut–brain–behavior feedback loop and integrating gut-targeted with behavioral-nutritional strategies [89,108]. This comprehensive approach requires a systematic framework that outlines not only the validation of forward causal pathways (microbiome → ASD), but also the investigation of reverse causation (ASD → microbiome), thereby fully addressing the system’s bidirectional dynamics (see Box 1).

7. Interventions Targeting MGBA: Therapeutic Prospects and Challenges

We first summarize representative clinical interventions targeting the MGBA—probiotics/prebiotics and fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT)—highlighting study designs, main findings, and limitations (Table 3).

7.1. Probiotics and Prebiotics: Promise and Limits

Given recurrent evidence of MGBA imbalance, probiotics and prebiotics have been evaluated as microbiome-targeted interventions in multiple clinical studies [120,121,122]. Systematic reviews and RCTs indicate that these interventions can alleviate GI symptoms in some children and, for certain strains or consortia, improve selected behavioral measures [120,123,124,125]. Other reviews, however, report inconsistent or nonsignificant effects on core ASD symptoms such as social communication and restricted, repetitive behaviors [105]. Overall, the evidence remains heterogeneous, with small and strain-specific effects influenced by dose, duration, baseline GI symptoms, and diet [126,127].

Methodologically, most studies are limited by small samples, heterogeneous interventions, nonstandardized outcome measures, and short follow-up. Open-label designs are prone to placebo and observer bias, and even RCTs show reduced comparability due to differences in strains, consortia, and baseline GI status [105]. A cautious summary is that evidence supporting improvements in GI symptoms is relatively consistent, whereas effects on core behavioral symptoms remain suggestive [126].

Recognizing ASD heterogeneity [86], the concept of personalized or precision synbiotics—tailoring strain–prebiotic combinations to individual microbiome and symptom profiles—is emerging. Pilot and open-label studies show modulation of microbial function and GI outcomes, with limited behavioral improvement, but large-scale, double-blind multicenter trials with standardized endpoints are lacking. Thus, personalized synbiotics currently represent a translational research direction rather than a clinical therapy [128].

Table 3.

Clinical interventions targeting the gut–brain axis: key trial highlights.

Table 3.

Clinical interventions targeting the gut–brain axis: key trial highlights.

| Intervention | Study Design | Sample Type (n, Age) | Duration/Follow-Up | Main Findings | Limitations and Challenges | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Probiotics/Prebiotics | Double-blind RCT | 80 children (5–14 y) | 12 weeks | Microbial α-diversity increases; shifts in several genera; signals linked to GI symptoms/anxiety | Short intervention; 16S limits species/function; activity predicted, not measured | Novau-Ferré et al. 2025 [129] |

| Double-blind RCT | 46 preschoolers (18–72 mo; 26 vs. 20) | 6 months | EEG coherence changes; correlations with behavior + lower inflammatory markers | Small n; wide age; no multiple-testing correction; no stratification by GI/sex | Billeci, L. et al. 2023 [130] | |

| Double-blind RCT | 80 children (5–16 y) | 12 weeks | No overall core-ASD improvement; age-stratified benefit (reduced hyperactivity/impulsivity in younger children) | Small n; mild baseline severity; non-personalized strains; 12 weeks may be short | Rojo-Marticella, M. et al. 2025 [123] | |

| Post hoc of Double-blind RCT | 35 (3–25 y) | 16 weeks | Baseline biomarkers ↔ ASD severity; probiotic group showed symptom improvement | Post hoc; wide age; no healthy biomarker controls; no multiple-testing correction | Sherman, H. T. et al. 2022 [131] | |

| Crossover RCT | 15 males (15–27 y) | 14-day washout; 28-day treatment | Adaptive behavior improved; trend toward greater social preference (eye-tracking); no GI outcomes captured | Very small, male-only; short; no GI assessment | Schmitt, L. M. et al. 2023 [132] | |

| Single-blind RCT | 180 children (2–9 y) | 3 months | Improvements on selected behavioral domains and constipation/diarrhea | Single-blind; short; parent-reported scales, limited validation | Narula Khanna, H. et al. 2025 [120] | |

| 2-stage pilot RCT | 35 (3–20 y) | 28 weeks (oxytocin added from week 16) | Probiotic + oxytocin > either alone on clinical measures | Small pilot; wide age; two-stage less robust; parental-report bias | Kong, X. J. et al. 2021 [133] | |

| Nutritional RCT | 30 (ASD + neurotypical controls) | 12 weeks | Immune reconfiguration (e.g., IFN-γ ↓, IL-8/MIP-1β ↑); behavior not integrated | Small n; immunology-only endpoints; limited link to clinical behavior | Naranjo-Galvis, C. A. et al. 2025 [134] | |

| Parallel-group Double-blind RCT | 43 children (2–8 y) | 6 months | QoL and some behavioral measures improved; no change in core-ASD severity | Small n; COVID-19 recruitment issues; few females; core scale may be insensitive at 6 mo | Mazzone, L. et al. 2024 [135] | |

| FMT | Multi-center Double-blind RCT | 29 children with ASD (2–13 y) | 4 months | GI outcomes improved; some behavioral measures improved; taxa shifts (e.g., Collinsella) tracked with outcomes; younger children responded better | Open-label components; small n; inconsistent endpoints/timepoints; missing final metagenomic/metabolomic timepoint in some. | Chen, Q. et al. 2024 [136] |

Abbreviations: RCT, randomized controlled trial; GI, gastrointestinal; ASD, autism spectrum disorder; EEG, electroencephalography; IFN-γ, interferon-gamma; IL, interleukin; MIP-1β, macrophage inflammatory protein-1 beta; QoL, quality of life; FMT, fecal microbiota transplantation; n, number of participants; y, years; mo, months.

7.2. FMT: Breakthroughs and Caution

As a more potent modality for gut ecosystem remodeling, FMT has shown encouraging but preliminary evidence in ASD. Open-label microbiota transfer therapy studies, such as those by Kang et al., reported improvements in pediatric GI symptoms (≈59%) and reductions in Childhood Autism Rating Scale scores (≈47%) sustained over two years [137]. However, these results derive from small, uncontrolled studies and require confirmation in double-blind RCTs [138,139].

Recently, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, and multicenter trials of oral FMT have emerged, elevating the level of evidence. Overall, findings suggest potential benefits for GI outcomes and certain behavioral measures, though effects vary by scale, time point, and cohort. Larger samples and standardized endpoints are needed to clarify reproducibility, effect size, and durability [27,140,141].

Safety and regulatory oversight warrant particular attention. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has issued safety alerts—most notably in 2019 and 2020— regarding the transmission of multidrug-resistant organisms, opportunistic pathogens (e.g., Escherichia coli, Enterococcus faecium), and rare cases of severe infections and deaths resulting from donor stool–derived FMT materials [142]. These events underscored the need for systematic donor screening, including comprehensive medical history, stool and blood testing for infectious agents, and specific screening for antimicrobial resistance genes or MDRO carriage. Outside of recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection (rCDI)—the only indication currently approved for clinical FMT—such interventions are considered investigational and must adhere to regulatory pathways such as FDA Investigational New Drug applications or equivalent local ethical oversight. At present, approved microbiome-based products—Rebyota (enema formulation) and Vowst (oral spore-based therapy)—are indicated solely for rCDI prevention and are not generalizable to ASD [143]. Before clinical adoption, FMT for ASD should be validated through large, multicenter, double-blind RCTs using standardized donor screening, preparation, delivery, and follow-up protocols, to robustly establish both efficacy and safety [139].

8. Conclusions and Future Directions

8.1. Summary of Current Evidence

The MGBA represents a conceptual framework for exploring part of the clinical heterogeneity observed in ASD. Gastrointestinal symptoms appear more prevalent among individuals with ASD and are frequently accompanied by shifts in microbiome composition and metabolite profiles, which are broadly consistent with mechanistic hypotheses involving neuroimmune and neuroplasticity pathways. Together, these findings form a convergent yet largely associational body of evidence [144]. However, no reproducible or universal “ASD microbiome signature” has been established across cohorts; reported taxa-level alterations often vary in both direction and magnitude among studies, reflecting substantial methodological and population heterogeneity. The most reproducible signals tend to converge on microbial functional pathways rather than on specific taxa, suggesting that pathway-level features may better capture biologically relevant host–microbe interactions. Causal directionality has not yet been established, and major confounders—including selective eating, medication use, and methodological variability—persist [21,75,108]. A recent large-scale, multi-domain metagenomic study identified functional signatures with potential discriminatory capacity, indicating a step toward translational exploration. Nonetheless, these models remain at an early research stage and require rigorous prospective validation, standardized data collection, and cross-population reproducibility assessment before any clinical application [109].

8.2. Contribution and Limitations of This Review

The primary contribution of this review is translating abstract concepts of causal inference and precision-oriented study design into actionable frameworks for the ASD-MGBA field. By synthesizing complex methodological challenges and proposing concrete, actionable frameworks (e.g., the bidirectional causality model in Box 1 and the confounder control strategies in Box 2), this work provides a specific roadmap for future research.

However, this review has limitations. As a narrative review, the selection of studies is not exhaustive and is subject to the authors’ selection bias, unlike a systematic review or meta-analysis, which quantifies all available evidence. The forward-looking proposals, particularly for biomarker cutoffs and patient stratification, are intended as conceptual examples to guide future trial design rather than as definitive clinical guidelines.

8.3. Priorities for Future Research

Future investigations should aim to move from correlation toward mechanistic understanding and causal inference. In addition to advancing from association to causation, future research must rigorously address key methodological confounders that may obscure microbiome–behavior relationships (Box 2).

Studies need to link specific microbial metabolites and pathways to neural plasticity through controlled animal and organoid models, complemented by longitudinal, standardized multi-omic human cohorts that rigorously account for diet, medication, and geographic variation. Methodologically, these multi-center studies should model as a random effect and employ leave-site-out validation for robustness, while multi-omics integration can be achieved using frameworks such as MOFA+ or DIABLO. MR analyses should be employed cautiously—only when instrumental variable assumptions are satisfied—and their limitations transparently reported. Therapeutic trials should move beyond a one-size-fits-all approach by integrating gut-targeted, behavioral, and nutritional interventions. A critical next step is to stratify participants based on well-defined clinical and biological phenotypes to identify subgroups most likely to benefit from MGBA-targeted therapies. For instance, future RCTs could prioritize recruitment of specific subgroups, such as individuals with (1) a high burden of GI symptoms, (2) pronounced restrictive eating behaviors or sensory hypersensitivities that directly shape the microbiome, or (3) a recent history of significant microbial disruption, such as exposure to antibiotics or PPIs.

To objectify this stratification, a candidate biomarker panel could be employed for patient screening and monitoring. Such a panel might include (1) microbial metabolites like SCFAs and the tryptophan–kynurenine ratio to assess metabolic function; (2) gut-derived xenobiotics like p-cresol, which reflect dysbiotic activity; (3) markers of gut inflammation, such as fecal calprotectin; and (4) key systemic inflammatory cytokines. This approach would enable the development of more precise protocols. For example, a trial might set an inclusion criterion of fecal calprotectin > 50 µg/g to target gut inflammation, or it could involve longitudinal monitoring of the tryptophan-kynurenine ratio at 3- or 6-month intervals to gauge therapeutic response to an immunomodulatory probiotic. These trials must be conducted as preregistered, multicenter RCTs with harmonized endpoints to ensure reproducibility and clinical relevance.

Particular caution and regulatory oversight are essential for FMT, which remains experimental outside of Clostridioides difficile infection. Ultimately, reproducibility, transparent data sharing, and formal causal inference frameworks will determine whether functional microbiome and metabolite patterns can be validated as reliable biomarkers or as modifiable contributors to ASD-related phenotypes.

Author Contributions

Z.Z.: Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing, Conceptualization, Software, Validation, Visualization. W.K.: Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing, Visualization, Methodology. Y.M.: Writing—original draft, Visualization. Y.H.: Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing, Conceptualization, Project administration, Resources, Supervision. X.Z.: Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing, Supervision, Methodology, Software, Funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Shenzhen Clinical Research Center for Gastroenterology (Gastrointestinal Surgery) (Grant No. LCYSSQ20220823091203008) and the Shenzhen Medical Research Fund (Grant No. A2402008).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| 5-HT | Serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine) |

| ASD | Autism spectrum disorder |

| BBB | Blood–brain barrier |

| EC | Enterochromaffin (cells) |

| ENS | Enteric nervous system |

| FDA | United States Food and Drug Administration |

| FMT | Fecal microbiota transplantation |

| GI | Gastrointestinal |

| GABA | γ-Aminobutyric acid |

| HPA | Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (axis) |

| IDO | Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase |

| IL-1β | Interleukin-1β |

| IL-18 | Interleukin-18 |

| KYN | Kynurenine |

| LAT1 | Large neutral amino acid transporter 1 |

| L-DOPA | L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| MGBA | Microbiota–gut–brain axis |

| MR | Mendelian randomization |

| MR-Egger | Mendelian randomization-Egger (regression) |

| NMDA | N-methyl-D-aspartate |

| NLRP3 | NLRP3 inflammasome |

| RCTs | Randomized controlled trials |

| rCDI | Recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection |

| SCFAs | Short-chain fatty acids |

| SNS | sympathetic nervous systems |

| TRP | Tryptophan |

| TRYCATs | Tryptophan catabolites |

| TSPO | 18-kDa translocator protein |

| VN | Vagus nerve |

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Clinical Testing and Diagnosis for Autism Spectrum Disorder. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/autism/hcp/diagnosis/index.html (accessed on 27 November 2024).

- Korteniemi, J.; Karlsson, L.; Aatsinki, A. Systematic review: Autism spectrum disorder and the gut microbiota. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2023, 148, 242–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stilling, R.M.; van de Wouw, M.; Clarke, G.; Stanton, C.; Dinan, T.G.; Cryan, J.F. The neuropharmacology of butyrate: The bread and butter of the microbiota-gut-brain axis? Neurochem. Int. 2016, 99, 110–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, G.; Stilling, R.M.; Kennedy, P.J.; Stanton, C.; Cryan, J.F.; Dinan, T.G. Minireview: Gut microbiota: The neglected endocrine organ. Mol. Endocrinol. 2014, 28, 1221–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Usui, N.; Kobayashi, H.; Shimada, S. Neuroinflammation and oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of autism spectrum disorder. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 5487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandin, S.; Yip, B.H.K.; Yin, W.; Weiss, L.A.; Dougherty, J.D.; Fass, S.; Constantino, J.N.; Hailin, Z.; Turner, T.N.; Marrus, N.; et al. Examining Sex Differences in Autism Heritability. JAMA Psychiatry 2024, 81, 673–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Love, C.; Sominsky, L.; O’Hely, M.; Berk, M.; Vuillermin, P.; Dawson, S.L. Prenatal environmental risk factors for autism spectrum disorder and their potential mechanisms. BMC Med. 2024, 22, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaste, P.; Leboyer, M. Autism risk factors: Genes, environment, and gene-environment interactions. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2012, 14, 281–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeidan, J.; Fombonne, E.; Scorah, J.; Ibrahim, A.; Durkin, M.S.; Saxena, S.; Yusuf, A.; Shih, A.; Elsabbagh, M. Global prevalence of autism: A systematic review update. Autism Res. 2022, 15, 778–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crowell, J.A.; Keluskar, J.; Gorecki, A. Parenting behavior and the development of children with autism spectrum disorder. Compr. Psychiatry 2019, 90, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenlee, J.L.; Stelter, C.R.; Piro-Gambetti, B.; Hartley, S.L. Trajectories of dysregulation in children with autism spectrum disorder. J. Clin. Child. Adolesc. Psychol. 2021, 50, 858–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyman, S.L.; Levy, S.E.; Myers, S.M.; Kuo, D.Z.; Apkon, S.; Davidson, L.F.; Ellerbeck, K.A.; Foster, J.E.; Noritz, G.H.; Leppert, M.O.C. Identification, evaluation, and management of children with autism spectrum disorder. Pediatrics 2020, 145, e20193447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, M.; Niu, B.; Ma, J.; Ge, Y.; Han, Y.; Wu, W.; Yue, C. Intervention and research progress of gut microbiota-immune-nervous system in autism spectrum disorders among students. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1535455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, E.A. Gut feelings: The emerging biology of gut-brain communication. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2011, 12, 453–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cryan, J.F.; Dinan, T.G. Mind-altering microorganisms: The impact of the gut microbiota on brain and behaviour. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2012, 13, 701–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalile, B.; Van Oudenhove, L.; Vervliet, B.; Verbeke, K. The role of short-chain fatty acids in microbiota-gut-brain communication. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 16, 461–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Riordan, K.J.; Moloney, G.M.; Keane, L.; Clarke, G.; Cryan, J.F. The gut microbiota-immune-brain axis: Therapeutic implications. Cell Rep. Med. 2025, 6, 101982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, J.B.; Johansen, L.J.; Powell, L.D.; Quig, D.; Rubin, R.A. Gastrointestinal flora and gastrointestinal status in children with autism–comparisons to typical children and correlation with autism severity. BMC Gastroenterol. 2011, 11, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holingue, C.; Newill, C.; Lee, L.C.; Pasricha, P.J.; Daniele Fallin, M. Gastrointestinal symptoms in autism spectrum disorder: A review of the literature on ascertainment and prevalence. Autism Res. 2018, 11, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esnafoglu, E.; Cırrık, S.; Ayyıldız, S.N.; Erdil, A.; Ertürk, E.Y.; Daglı, A.; Noyan, T. Increased serum zonulin levels as an intestinal permeability marker in autistic subjects. J. Pediatr. 2017, 188, 240–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lasheras, I.; Real-López, M.; Santabárbara, J. Prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms in autism spectrum disorder: A meta-analysis. An. Pediatría (Engl. Ed.) 2023, 99, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Gao, Z.; Liu, C.; Liu, T.; Gao, J.; Cai, Y.; Fan, X. Alteration of Gut Microbiota: New Strategy for Treating Autism Spectrum Disorder. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 792490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulceri, F.; Morelli, M.; Santocchi, E.; Cena, H.; Del Bianco, T.; Narzisi, A.; Calderoni, S.; Muratori, F. Gastrointestinal symptoms and behavioral problems in preschoolers with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Dig. Liver Dis. 2016, 48, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Missiego-Beltran, J.; Beltran-Velasco, A.I. The Role of Microbial Metabolites in the Progression of Neurodegenerative Diseases—Therapeutic Approaches: A Comprehensive Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Violi, F.; Cammisotto, V.; Bartimoccia, S.; Pignatelli, P.; Carnevale, R.; Nocella, C. Gut-derived low-grade endotoxaemia, atherothrombosis and cardiovascular disease. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2023, 20, 24–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blevins, H.M.; Xu, Y.; Biby, S.; Zhang, S. The NLRP3 inflammasome pathway: A review of mechanisms and inhibitors for the treatment of inflammatory diseases. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 879021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Xueying, Z.; Jiaqu, C.; Qiyi, C.; Huanlong, Q.; Ning, L.; Yasong, D.; Xiaoxin, Z.; Rong, Y.; Jubao, L.; et al. FTACMT study protocol: A multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial of faecal microbiota transplantation for autism spectrum disorder. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e051613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, A.H.; Raison, C.L. The role of inflammation in depression: From evolutionary imperative to modern treatment target. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2016, 16, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segerstrom, S.C.; Miller, G.E. Psychological stress and the human immune system: A meta-analytic study of 30 years of inquiry. Psychol. Bull. 2004, 130, 601–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varatharaj, A.; Galea, I. The blood-brain barrier in systemic inflammation. Brain Behav. Immun. 2017, 60, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoogland, I.C.; Houbolt, C.; van Westerloo, D.J.; van Gool, W.A.; van de Beek, D. Systemic inflammation and microglial activation: Systematic review of animal experiments. J. Neuroinflammation 2015, 12, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frick, L.R.; Williams, K.; Pittenger, C. Microglial dysregulation in psychiatric disease. Clin. Dev. Immunol. 2013, 2013, 608654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, S.-H.; Kim, C.y.; Lee, E.; Lee, C.; Lee, K.-S.; Lee, J.; Park, H.; Choi, B.; Hwang, I.; Kim, J.; et al. Microglial NLRP3-gasdermin D activation impairs blood-brain barrier integrity through interleukin-1β-independent neutrophil chemotaxis upon peripheral inflammation in mice. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, D.; Gharehgazlou, A.; Da Silva, T.; Labrie-Cleary, C.; Wilson, A.A.; Meyer, J.H.; Mizrahi, R.; Rusjan, P.M. In vivo imaging translocator protein (TSPO) in autism spectrum disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology 2022, 47, 1421–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carabotti, M.; Scirocco, A.; Maselli, M.A.; Severi, C. The gut-brain axis: Interactions between enteric microbiota, central and enteric nervous systems. Ann. Gastroenterol. Q. Publ. Hell. Soc. Gastroenterol. 2015, 28, 203–209. [Google Scholar]

- Waise, T.M.Z.; Dranse, H.J.; Lam, T.K.T. The metabolic role of vagal afferent innervation. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 15, 625–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaz, B.; Bazin, T.; Pellissier, S. The Vagus Nerve at the Interface of the Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Y.; Wang, B.; Gao, H.; He, C.; Hua, R.; Liang, C.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Y.; Xin, S.; Xu, J. Vagus Nerve and Underlying Impact on the Gut Microbiota-Brain Axis in Behavior and Neurodegenerative Diseases. J. Inflamm. Res. 2022, 15, 6213–6230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miri, S.; Yeo, J.; Abubaker, S.; Hammami, R. Neuromicrobiology, an emerging neurometabolic facet of the gut microbiome? Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1098412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Hao, Y.; Zhu, J.; Owyang, C. Serotonin released from intestinal enterochromaffin cells mediates luminal non-cholecystokinin-stimulated pancreatic secretion in rats. Gastroenterology 2000, 118, 1197–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strader, A.D.; Woods, S.C. Gastrointestinal hormones and food intake. Gastroenterology 2005, 128, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo, J.A.; Forsythe, P.; Chew, M.V.; Escaravage, E.; Savignac, H.M.; Dinan, T.G.; Bienenstock, J.; Cryan, J.F. Ingestion of Lactobacillus strain regulates emotional behavior and central GABA receptor expression in a mouse via the vagus nerve. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 16050–16055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bercik, P.; Park, A.J.; Sinclair, D.; Khoshdel, A.; Lu, J.; Huang, X.; Deng, Y.; Blennerhassett, P.A.; Fahnestock, M.; Moine, D.; et al. The anxiolytic effect of Bifidobacterium longum NCC3001 involves vagal pathways for gut-brain communication. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2011, 23, 1132–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaz, B. Is-there a place for vagus nerve stimulation in inflammatory bowel diseases? Bioelectron. Med. 2018, 4, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bali, A.; Jaggi, A.S. An Integrative Review on Role and Mechanisms of Ghrelin in Stress, Anxiety and Depression. Curr. Drug Targets 2016, 17, 495–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Tang, X.; He, X.; Weng, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Fang, Q.; Zhang, L. A Comprehensive Review of the Role of the Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis via Neuroinflammation: Advances and Therapeutic Implications for Ischemic Stroke. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osredkar, J.; Kumer, K.; Godnov, U.; Jekovec Vrhovsek, M.; Vidova, V.; Price, E.J.; Javornik, T.; Avgustin, G.; Fabjan, T. Urinary Metabolomic Profile in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Ran, M.; Li, H.; Lin, Y.; Ma, K.; Yang, Y.; Fu, X.; Yang, S. New insight into neurological degeneration: Inflammatory cytokines and blood–brain barrier. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2022, 15, 1013933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiappelli, J.; Pocivavsek, A.; Nugent, K.L.; Notarangelo, F.M.; Kochunov, P.; Rowland, L.M.; Schwarcz, R.; Hong, L.E. Stress-induced increase in kynurenic acid as a potential biomarker for patients with schizophrenia and distress intolerance. JAMA Psychiatry 2014, 71, 761–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huuskonen, J.; Suuronen, T.; Nuutinen, T.; Kyrylenko, S.; Salminen, A. Regulation of microglial inflammatory response by sodium butyrate and short-chain fatty acids. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2004, 141, 874–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosoi, T.; Okuma, Y.; Matsuda, T.; Nomura, Y. Novel pathway for LPS-induced afferent vagus nerve activation: Possible role of nodose ganglion. Auton. Neurosci. 2005, 120, 104–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, Y.P.; Bernardi, A.; Frozza, R.L. The Role of Short-Chain Fatty Acids From Gut Microbiota in Gut-Brain Communication. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauer, A.K.; Malijauskaite, S.; Meleady, P.; Boeckers, T.M.; McGourty, K.; Grabrucker, A.M. Zinc is a key regulator of gastrointestinal development, microbiota composition and inflammation with relevance for autism spectrum disorders. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2022, 79, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernikova, M.A.; Flores, G.D.; Kilroy, E.; Labus, J.S.; Mayer, E.A.; Aziz-Zadeh, L. The brain-gut-microbiome system: Pathways and implications for autism spectrum disorder. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, A.P.; Marrelli, L.M.; Bonner-Reid, F.T.; Shekhawat, P.; Toney, R.; Benipal, I.K.; Dias, H.A.; Kandi, A.; Siddiqui, H.F. Gut-Brain Axis: Understanding the Interlink Between Alterations in the Gut Microbiota and Autism Spectrum Disorder. Cureus 2025, 17, e88579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, T.L.; Wolin, M.J. Pathways of acetate, propionate, and butyrate formation by the human fecal microbial flora. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1996, 62, 1589–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macfarlane, S.; Macfarlane, G.T. Regulation of short-chain fatty acid production. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2003, 62, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, M.E. Probiotics: Definition, sources, selection, and uses. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2008, 46 (Suppl. 2), S58–S61; discussion S144-151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LeBlanc, J.G.; Chain, F.; Martin, R.; Bermudez-Humaran, L.G.; Courau, S.; Langella, P. Beneficial effects on host energy metabolism of short-chain fatty acids and vitamins produced by commensal and probiotic bacteria. Microb. Cell Fact. 2017, 16, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, K.; Lutgendorff, F.; Phan, V.; Soderholm, J.D.; Sherman, P.M.; McKay, D.M. Enhanced translocation of bacteria across metabolically stressed epithelia is reduced by butyrate. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2010, 16, 1138–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijay, N.; Morris, M.E. Role of monocarboxylate transporters in drug delivery to the brain. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2014, 20, 1487–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kekuda, R.; Manoharan, P.; Baseler, W.; Sundaram, U. Monocarboxylate 4 mediated butyrate transport in a rat intestinal epithelial cell line. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2013, 58, 660–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dass, N.B.; John, A.K.; Bassil, A.K.; Crumbley, C.W.; Shehee, W.R.; Maurio, F.P.; Moore, G.B.; Taylor, C.M.; Sanger, G.J. The relationship between the effects of short-chain fatty acids on intestinal motility in vitro and GPR43 receptor activation. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2007, 19, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nohr, M.K.; Egerod, K.L.; Christiansen, S.H.; Gille, A.; Offermanns, S.; Schwartz, T.W.; Moller, M. Expression of the short chain fatty acid receptor GPR41/FFAR3 in autonomic and somatic sensory ganglia. Neuroscience 2015, 290, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Poul, E.; Loison, C.; Struyf, S.; Springael, J.Y.; Lannoy, V.; Decobecq, M.E.; Brezillon, S.; Dupriez, V.; Vassart, G.; Van Damme, J.; et al. Functional characterization of human receptors for short chain fatty acids and their role in polymorphonuclear cell activation. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 25481–25489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fellows, R.; Denizot, J.; Stellato, C.; Cuomo, A.; Jain, P.; Stoyanova, E.; Balazsi, S.; Hajnady, Z.; Liebert, A.; Kazakevych, J.; et al. Microbiota derived short chain fatty acids promote histone crotonylation in the colon through histone deacetylases. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, H.G.; Takeo Sato, F.; Curi, R.; Vinolo, M.A.R. Fatty acids as modulators of neutrophil recruitment, function and survival. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2016, 785, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, P.V.; Hao, L.; Offermanns, S.; Medzhitov, R. The microbial metabolite butyrate regulates intestinal macrophage function via histone deacetylase inhibition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 2247–2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Kim, M.; Kang, S.G.; Jannasch, A.H.; Cooper, B.; Patterson, J.; Kim, C.H. Short-chain fatty acids induce both effector and regulatory T cells by suppression of histone deacetylases and regulation of the mTOR-S6K pathway. Mucosal Immunol. 2015, 8, 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erny, D.; Hrabě de Angelis, A.L.; Jaitin, D.; Wieghofer, P.; Staszewski, O.; David, E.; Keren-Shaul, H.; Mahlakoiv, T.; Jakobshagen, K.; Buch, T.; et al. Host microbiota constantly control maturation and function of microglia in the CNS. Nat. Neurosci. 2015, 18, 965–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Leeds, P.; Chuang, D.M. The HDAC inhibitor, sodium butyrate, stimulates neurogenesis in the ischemic brain. J. Neurochem. 2009, 110, 1226–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Church, J.S.; Bannish, J.A.M.; Adrian, L.A.; Rojas Martinez, K.; Henshaw, A.; Schwartzer, J.J. Serum short chain fatty acids mediate hippocampal BDNF and correlate with decreasing neuroinflammation following high pectin fiber diet in mice. Front. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1134080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terry, N.; Margolis, K.G. Serotonergic Mechanisms Regulating the GI Tract: Experimental Evidence and Therapeutic Relevance. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2017, 239, 319–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yano, J.M.; Yu, K.; Donaldson, G.P.; Shastri, G.G.; Ann, P.; Ma, L.; Nagler, C.R.; Ismagilov, R.F.; Mazmanian, S.K.; Hsiao, E.Y. Indigenous bacteria from the gut microbiota regulate host serotonin biosynthesis. Cell 2015, 161, 264–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlynarska, E.; Barszcz, E.; Budny, E.; Gajewska, A.; Kopec, K.; Wasiak, J.; Rysz, J.; Franczyk, B. The Gut-Brain-Microbiota Connection and Its Role in Autism Spectrum Disorders. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stasi, C.; Bellini, M.; Bassotti, G.; Blandizzi, C.; Milani, S. Serotonin receptors and their role in the pathophysiology and therapy of irritable bowel syndrome. Tech. Coloproctol. 2014, 18, 613–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browning, K.N. Role of central vagal 5-HT3 receptors in gastrointestinal physiology and pathophysiology. Front. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strandwitz, P.; Kim, K.H.; Terekhova, D.; Liu, J.K.; Sharma, A.; Levering, J.; McDonald, D.; Dietrich, D.; Ramadhar, T.R.; Lekbua, A.; et al. GABA-modulating bacteria of the human gut microbiota. Nat. Microbiol. 2019, 4, 396–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rautio, J.; Gynther, M.; Laine, K. LAT1-mediated Prodrug Uptake: A Way to Breach the blood–brain barrier? Ther. Deliv. 2013, 4, 281–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puris, E.; Gynther, M.; Auriola, S.; Huttunen, K.M. L-Type amino acid transporter 1 as a target for drug delivery. Pharm. Res. 2020, 37, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Launay, J.-M.; Delorme, R.; Pagan, C.; Callebert, J.; Leboyer, M.; Vodovar, N. Impact of IDO activation and alterations in the kynurenine pathway on hyperserotonemia, NAD+ production, and AhR activation in autism spectrum disorder. Transl. Psychiatry 2023, 13, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almulla, A.F.; Thipakorn, Y.; Tunvirachaisakul, C.; Maes, M. The tryptophan catabolite or kynurenine pathway in autism spectrum disorder; a systematic review and meta-analysis. Autism Res. 2023, 16, 2302–2315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana-Coelho, D. Does the kynurenine pathway play a pathogenic role in autism spectrum disorder? Brain Behav. Immun. Health 2024, 40, 100839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattorusso, A.; Di Genova, L.; Dell’Isola, G.B.; Mencaroni, E.; Esposito, S. Autism spectrum disorders and the gut microbiota. Nutrients 2019, 11, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, K.A.; Yin, X.; Rutherford, E.M.; Wee, B.; Choi, J.; Chrisman, B.S.; Dunlap, K.L.; Hannibal, R.L.; Hartono, W.; Lin, M.; et al. Multi-angle meta-analysis of the gut microbiome in Autism Spectrum Disorder: A step toward understanding patient subgroups. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 17034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, M.M. The Role of the Microbiome in Autism: All That We Know about All That We Don’t Know. mSystems 2021, 6, e00234-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Li, J.; Wu, F.; Zheng, H.; Peng, Q.; Zhou, H. Altered composition and function of intestinal microbiota in autism spectrum disorders: A systematic review. Transl. Psychiatry 2019, 9, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, Y.; Lee, T.; Oh, H.-S.; Hyun, Y.; Song, S.; Chun, J.; Kim, H.-W. Gut microbial and clinical characteristics of individuals with autism spectrum disorder differ depending on the ecological structure of the gut microbiome. Psychiatry Res. 2024, 335, 115775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, C.X.; Henders, A.K.; Alvares, G.A.; Wood, D.L.; Krause, L.; Tyson, G.W.; Restuadi, R.; Wallace, L.; McLaren, T.; Hansell, N.K. Autism-related dietary preferences mediate autism-gut microbiome associations. Cell 2021, 184, 5916–5931.e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaza-Díaz, J.; Gómez-Fernández, A.; Chueca, N.; Torre-Aguilar, M.J.d.l.; Gil, Á.; Perez-Navero, J.L.; Flores-Rojas, K.; Martín-Borreguero, P.; Solis-Urra, P.; Ruiz-Ojeda, F.J. Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) with and without mental regression is associated with changes in the fecal microbiota. Nutrients 2019, 11, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.; Liu, J.; Cetinbas, M.; Sadreyev, R.; Koh, M.; Huang, H.; Adeseye, A.; He, P.; Zhu, J.; Russell, H. New and preliminary evidence on altered oral and gut microbiota in individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD): Implications for ASD diagnosis and subtyping based on microbial biomarkers. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Yang, J.; Zhang, J.; Liang, C.; Wang, Y.; Chen, B.; Zhao, C.; Wang, J.; Zhang, G.; Zhao, D. Correlation of gut microbiome between ASD children and mothers and potential biomarkers for risk assessment. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2019, 17, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dan, Z.; Mao, X.; Liu, Q.; Guo, M.; Zhuang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Chen, K.; Chen, J.; Xu, R.; Tang, J. Altered gut microbial profile is associated with abnormal metabolism activity of Autism Spectrum Disorder. Gut Microbes 2020, 11, 1246–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Li, L.; Wu, X.; Hou, F.; Chen, Y.; Shi, L.; Liu, Q.; Zhu, K.; Jiang, Q.; Feng, Y. Alteration of the fecal microbiota in Chinese children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism Res. 2022, 15, 996–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, S.; Oh, D.; Lee, S.; Park, J.; Ahn, J.; Choi, S.; Cheon, K.-A. Altered gut microbiota in Korean children with autism spectrum disorders. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhai, Q.; Cen, S.; Jiang, J.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H.; Chen, W. Disturbance of trace element and gut microbiota profiles as indicators of autism spectrum disorder: A pilot study of Chinese children. Environ. Res. 2019, 171, 501–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Ma, W.; Zhang, J.; He, Y.; Wang, J. Analysis of gut microbiota profiles and microbe-disease associations in children with autism spectrum disorders in China. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 13981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, B.L.; Hornig, M.; Parekh, T.; Lipkin, W.I. Application of novel PCR-based methods for detection, quantitation, and phylogenetic characterization of Sutterella species in intestinal biopsy samples from children with autism and gastrointestinal disturbances. MBio 2012, 3, e00261-11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Shi, K.; Liu, X.; Dai, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Du, X.; Zhu, T.; Yu, J.; Fang, S. Gut microbial profile is associated with the severity of social impairment and IQ performance in children with autism spectrum disorder. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 789864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedarf, J.R.; Hildebrand, F.; Coelho, L.P.; Sunagawa, S.; Bahram, M.; Goeser, F.; Bork, P.; Wüllner, U. Functional implications of microbial and viral gut metagenome changes in early stage L-DOPA-naïve Parkinson’s disease patients. Genome Med. 2017, 9, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurita, M.F.; Cárdenas, P.A.; Sandoval, M.E.; Peña, M.C.; Fornasini, M.; Flores, N.; Monaco, M.H.; Berding, K.; Donovan, S.M.; Kuntz, T. Analysis of gut microbiome, nutrition and immune status in autism spectrum disorder: A case-control study in Ecuador. Gut Microbes 2020, 11, 453–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, R.; Xu, F.; Wang, Y.; Duan, M.; Guo, M.; Zhang, Q.; Zhao, H.; Zheng, H. Changes in the gut microbiota of children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism Res. 2020, 13, 1614–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, M.; Li, Q.; Zhang, J.; Wen, F.; Dang, W.; Duan, G.; Li, H.; Ruan, W.; Yang, P.; Guan, C. Characterization of intestinal microbiota and probiotics treatment in children with autism spectrum disorders in China. Front. Neurol. 2019, 10, 1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, N.; Yang, J.-J.; Zhao, D.-M.; Chen, B.; Zhang, G.-Q.; Chen, S.; Cao, R.-F.; Yu, H.; Zhao, C.-Y. Probiotics and fructo-oligosaccharide intervention modulate the microbiota-gut brain axis to improve autism spectrum reducing also the hyper-serotonergic state and the dopamine metabolism disorder. Pharmacol. Res. 2020, 157, 104784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Han, F.; Wang, Q.; Fan, F. Probiotics and Prebiotics in the Treatment of Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Narrative Review. J. Integr. Neurosci. 2024, 23, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nearing, J.T.; Douglas, G.M.; Hayes, M.G.; MacDonald, J.; Desai, D.K.; Allward, N.; Jones, C.M.A.; Wright, R.J.; Dhanani, A.S.; Comeau, A.M.; et al. Microbiome differential abundance methods produce different results across 38 datasets. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scanu, M.; Del Chierico, F.; Marsiglia, R.; Toto, F.; Guerrera, S.; Valeri, G.; Vicari, S.; Putignani, L. Correction of Batch Effect in Gut Microbiota Profiling of ASD Cohorts from Different Geographical Origins. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morton, J.T.; Jin, D.-M.; Mills, R.H.; Shao, Y.; Rahman, G.; McDonald, D.; Zhu, Q.; Balaban, M.; Jiang, Y.; Cantrell, K.; et al. Multi-level analysis of the gut–brain axis shows autism spectrum disorder-associated molecular and microbial profiles. Nat. Neurosci. 2023, 26, 1208–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Q.; Wong, O.W.H.; Lu, W.; Wan, Y.; Zhang, L.; Xu, W.; Li, M.K.T.; Liu, C.; Cheung, C.P.; Ching, J.Y.L.; et al. Multikingdom and functional gut microbiota markers for autism spectrum disorder. Nat. Microbiol. 2024, 9, 2344–2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Ke, H.; Wang, S.; Mao, W.; Fu, C.; Chen, X.; Fu, Q.; Qin, X.; Huang, Y.; Li, B.; et al. Leaky Gut Plays a Critical Role in the Pathophysiology of Autism in Mice by Activating the Lipopolysaccharide-Mediated Toll-Like Receptor 4-Myeloid Differentiation Factor 88-Nuclear Factor Kappa B Signaling Pathway. Neurosci. Bull. 2023, 39, 911–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano-Tomás, M.I.; Contreras-Romero, P.; Parellada, M.; Chaves-Cordero, J.; Zamora, J.; Hengst, M.; Pozo, P.; Del Campo, R.; Guzmán-Salas, S. Recognition of the microbial metabolite p-cresol in autism spectrum disorder: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2025, 18, 1576388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarimeidani, F.; Rahmati, R.; Mostafavi, M.; Darvishi, M.; Khodadadi, S.; Mohammadi, M.; Shamlou, F.; Bakhtiyari, S.; Alipourfard, I. Gut Microbiota and Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Neuroinflammatory Mediated Mechanism of Pathogenesis? Inflammation 2025, 48, 501–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tseng, C.-E.J.; Canales, C.; Marcus, R.E.; Parmar, A.J.; Hightower, B.G.; Mullett, J.E.; Makary, M.M.; Tassone, A.U.; Saro, H.K.; Townsend, P.H.; et al. In vivo translocator protein in females with autism spectrum disorder: A pilot study. Neuropsychopharmacology 2024, 49, 1193–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Picker, L.J.; Morrens, M.; Branchi, I.; Haarman, B.C.M.; Terada, T.; Kang, M.S.; Boche, D.; Tremblay, M.-E.; Leroy, C.; Bottlaender, M.; et al. TSPO PET brain inflammation imaging: A transdiagnostic systematic review and meta-analysis of 156 case-control studies. Brain Behav. Immun. 2023, 113, 415–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. Autism Spectrum Disorder and Eating Problems: The Imbalance of Gut Microbiota and the Gut-Brain Axis Hypothesis. J. Korean Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2024, 35, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartwig, F.P.; Davies, N.M.; Hemani, G.; Davey Smith, G. Two-sample Mendelian randomization: Avoiding the downsides of a powerful, widely applicable but potentially fallible technique. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2016, 45, 1717–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Xue, Y.; Jia, L.; Yang, M.; Huang, G.; Xie, J. Causal effects of gut microbiota on autism spectrum disorder: A two-sample mendelian randomization study. Medicine 2024, 103, e37284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liu, S.; Liu, F.; Dai, N.; Liang, R.; Lv, S.; Bao, L. Gut microbiota and autism spectrum disorders: A bidirectional Mendelian randomization study. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1267721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Dou, H.-H.; Liang, Q.-Y. Causal relationship between gut microbiota, blood metabolites and autism spectrum disorder: A Mendelian randomization study. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2025, 12, 250158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narula Khanna, H.; Roy, S.; Shaikh, A.; Chhabra, R.; Uddin, A. Impact of probiotic supplements on behavioural and gastrointestinal symptoms in children with autism spectrum disorder: A randomised controlled trial. BMJ Paediatr. Open 2025, 9, e003045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puricelli, C.; Rolla, R.; Gigliotti, L.; Boggio, E.; Beltrami, E.; Dianzani, U.; Keller, R. The Gut-Brain-Immune Axis in Autism Spectrum Disorders: A State-of-Art Report. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 755171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohle, L.; Mattei, D.; Heimesaat, M.M.; Bereswill, S.; Fischer, A.; Alutis, M.; French, T.; Hambardzumyan, D.; Matzinger, P.; Dunay, I.R.; et al. Ly6C(hi) Monocytes Provide a Link between Antibiotic-Induced Changes in Gut Microbiota and Adult Hippocampal Neurogenesis. Cell Rep. 2016, 15, 1945–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojo-Marticella, M.; Arija, V.; Canals-Sans, J. Effect of Probiotics on the Symptomatology of Autism Spectrum Disorder and/or Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder in Children and Adolescents: Pilot Study. Res. Child. Adolesc. Psychopathol. 2025, 53, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soleimanpour, S.; Abavisani, M.; Khoshrou, A.; Sahebkar, A. Probiotics for autism spectrum disorder: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis of effects on symptoms. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2024, 179, 92–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandhu, K.V.; Sherwin, E.; Schellekens, H.; Stanton, C.; Dinan, T.G.; Cryan, J.F. Feeding the microbiota-gut-brain axis: Diet, microbiome, and neuropsychiatry. Transl. Res. 2017, 179, 223–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahim, F.; Toguzbaeva, K.; Qasim, N.H.; Dzhusupov, K.O.; Zhumagaliuly, A.; Khozhamkul, R. Probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics for patients with autism spectrum disorder: A meta-analysis and umbrella review. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1294089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, P.; Zhang, C.-z.; Fan, Z.-x.; Yang, C.-j.; Cai, W.-y.; Huang, Y.-f.; Xiang, Z.-j.; Wu, J.-y.; Zhang, J.; Yang, J. Effect of probiotics on children with autism spectrum disorders: A meta-analysis. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2024, 50, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, J.; Calvo, D.C.; Nair, D.; Jain, S.; Montagne, T.; Dietsche, S.; Blanchard, K.; Treadwell, S.; Adams, J.; Krajmalnik-Brown, R. Precision synbiotics increase gut microbiome diversity and improve gastrointestinal symptoms in a pilot open-label study for autism spectrum disorder. mSystems 2024, 9, e0050324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novau-Ferré, N.; Papandreou, C.; Rojo-Marticella, M.; Canals-Sans, J.; Bulló, M. Gut microbiome differences in children with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and Autism Spectrum Disorder and effects of probiotic supplementation: A randomized controlled trial. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2025, 161, 105003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billeci, L.; Callara, A.L.; Guiducci, L.; Prosperi, M.; Morales, M.A.; Calderoni, S.; Muratori, F.; Santocchi, E. A randomized controlled trial into the effects of probiotics on electroencephalography in preschoolers with autism. Autism 2023, 27, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherman, H.T.; Liu, K.; Kwong, K.; Chan, S.T.; Li, A.C.; Kong, X.J. Carbon monoxide (CO) correlates with symptom severity, autoimmunity, and responses to probiotics treatment in a cohort of children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD): A post-hoc analysis of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry 2022, 22, 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitt, L.M.; Smith, E.G.; Pedapati, E.V.; Horn, P.S.; Will, M.; Lamy, M.; Barber, L.; Trebley, J.; Meyer, K.; Heiman, M.; et al. Results of a phase Ib study of SB-121, an investigational probiotic formulation, a randomized controlled trial in participants with autism spectrum disorder. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 5192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.J.; Liu, J.; Liu, K.; Koh, M.; Sherman, H.; Liu, S.; Tian, R.; Sukijthamapan, P.; Wang, J.; Fong, M.; et al. Probiotic and Oxytocin Combination Therapy in Patients with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Randomized, Double-Blinded, Placebo-Controlled Pilot Trial. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naranjo-Galvis, C.A.; Trejos-Gallego, D.M.; Correa-Salazar, C.; Triviño-Valencia, J.; Valencia-Buitrago, M.; Ruiz-Pulecio, A.F.; Méndez-Ramírez, L.F.; Zabaleta, J.; Meñaca-Puentes, M.A.; Ruiz-Villa, C.A.; et al. Anti-Inflammatory Diet and Probiotic Supplementation as Strategies to Modulate Immune Dysregulation in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]