Phylodynamics of SARS-CoV-2 Lineages B.1.1.7, B.1.1.529 and B.1.617.2 in Nigeria Suggests Divergent Evolutionary Trajectories

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Data Collection

2.2. Data Analysis

2.3. Phylogenetic Analysis

2.4. Phylogeography and Temporal Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Geographic Distribution of Variants

3.2. Introduction and Spread over Time

3.3. Phylogeny of Variants

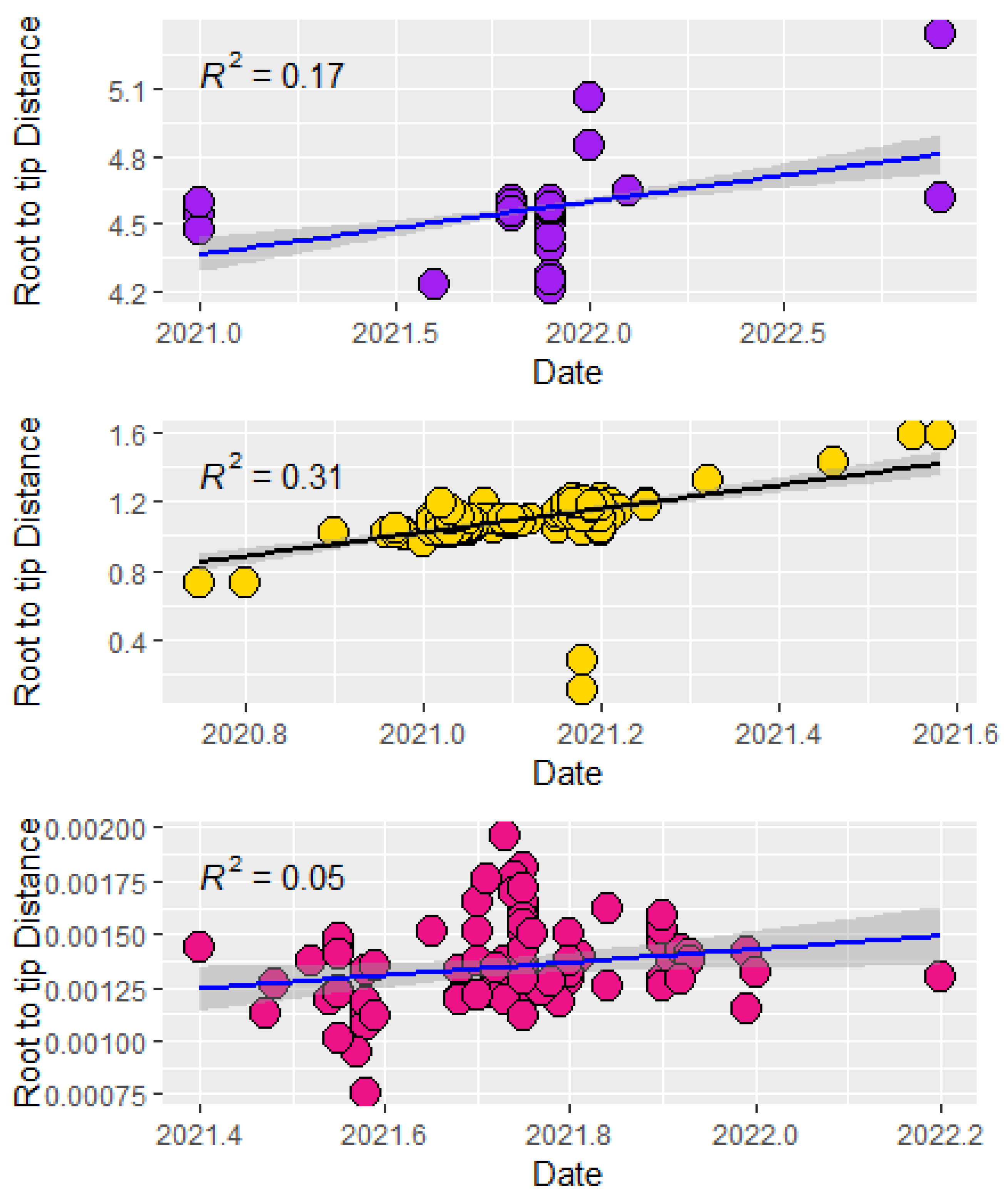

3.4. Temporal Signal and Evolutionary Rates

3.5. Viral Population Dynamics

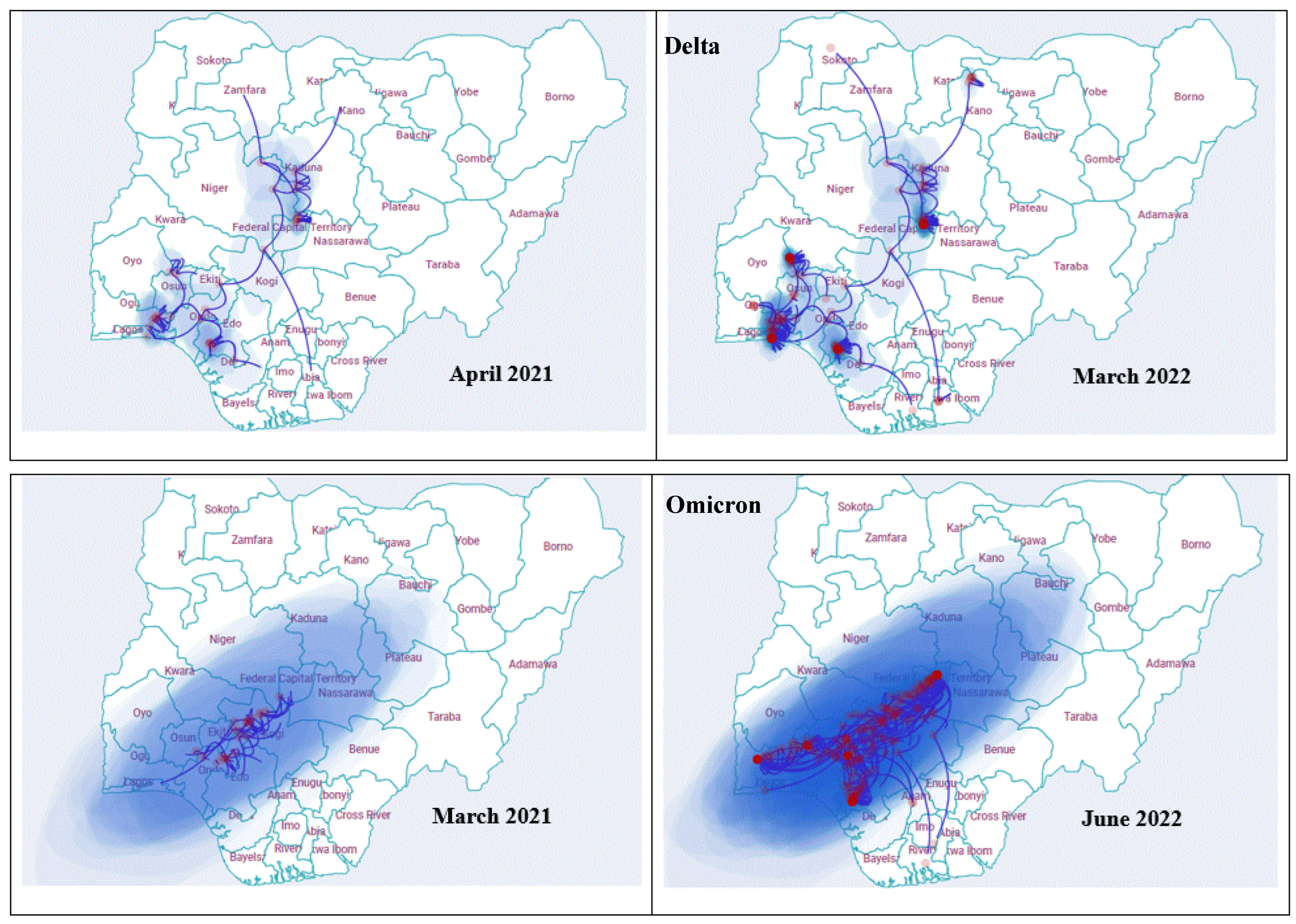

3.6. Geographic Dispersal Patterns

4. Discussion

4.1. Dominance and Geographic Spread of Delta and Omicron Variants

4.2. Temporal Dynamics and Variant Introductions

4.3. Evolutionary Rates and Population Expansion

4.4. Phylogeography and Transmission Patterns

4.5. Public Health Implications and Recommendations

- Expansion of Genomic Surveillance: Establishing regional sequencing hubs and training local scientists will enhance the country’s capacity to monitor viral evolution and detect emerging variants in real time.

- Enhanced Data Integration: Developing a national genomic data-sharing platform will facilitate rapid dissemination of insights to inform public health decision-making.

- Targeted Public Health Measures: Building capacity for mobile testing units, quarantine stations, and digital contact tracing in high-traffic regions can mitigate the spread of fast-moving variants during future epidemics.

- Vaccination and Booster Campaigns: Prioritizing booster doses for vulnerable populations and maintaining vaccine coverage will reduce the risk of severe disease from emerging variants.

- International Collaboration: Continued collaboration with global genomic surveillance networks like GISAID will provide valuable insights into regional and global viral evolution.

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MRCA | Most recent common ancestor |

| NCDC | Nigerian Centers for Disease Control |

| SARS-CoV-2 | severe acute respiratory syndrome virus 2 |

| VOC | Variants of Concern |

References

- Wu, F.; Zhao, S.; Yu, B.; Chen, Y.M.; Wang, W.; Song, Z.G.; Hu, Y.; Tao, Z.W.; Tian, J.H.; Pei, Y.Y.; et al. A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Nature 2020, 579, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, N.; Zhang, D.; Wang, W.; Li, X.; Yang, B.; Song, J.; Zhao, X.; Huang, B.; Shi, W.; Lu, R.; et al. A Novel Coronavirus from Patients with Pneumonia in China 2019. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 727–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathieu, E.; Ritchie, H.; Rodés-Guirao, L.; Appel, C.; Gavrilov, D.; Giattino, C.; Hasell, J.; Macdonald, B.; Dattani, S.; Beltekian, D.; et al. Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19). Our World in Data. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- Olawoye, I.B.; Oluniyi, P.E.; Oguzie, J.U.; Uwanibe, J.N.; Kayode, T.A.; Olumade, T.J.; Ajogbasile, F.V.; Parker, E.; Eromon, P.E.; Abechi, P.; et al. Emergence and spread of two SARS-CoV-2 variants of interest in Nigeria. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, M.; Pullano, G.; Pinotti, F.; Valdano, E.; Poletto, C.; Boëlle, P.-Y.; D’Ortenzio, E.; Yazdanpanah, Y.; Eholie, S.P.; Altmann, M.; et al. Preparedness and vulnerability of African countries against importations of COVID-19: A modelling study. Lancet 2020, 395, 871–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrega, R.; Nelson, D.K.S.; Koval, A.P.; Bond, N.G.; Heinrich, M.L.; Rowland, M.M.; Lathigra, R.; Bush, D.J.; Aimukanova, I.; Phinney, W.N.; et al. Cross-reactive antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 and MERS-CoV in pre-COVID-19 blood samples from Sierra Leoneans. Viruses 2021, 13, 2325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khare, S.; Gurry, C.; Freitas, L.; Schultz, M.B.; Bach, G.; Diallo, A.; Akite, N.; Ho, J.; Lee, R.T.; Yeo, W.; et al. GISAID’s Role in Pandemic Response. China CDC Wkly. 2021, 3, 1049–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Yang, X.L.; Wang, X.G.; Hu, B.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, W.; Si, H.R.; Zhu, Y.; Li, B.; Huang, C.L.; et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature 2020, 579, 270–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambaut, A.; Holmes, E.C.; O’Toole, Á.; Hill, V.; McCrone, J.T.; Ruis, C.; du Plessis, L.; Pybus, O.G. A dynamic nomenclature proposal for SARS-CoV-2 lineages to assist genomic epidemiology. Nat. Microbiol. 2020, 5, 1403–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Toole, Á.; Scher, E.; Underwood, A.; Jackson, B.; Hill, V.; McCrone, J.T.; Colquhoun, R.; Ruis, C.; Abu-Dahab, K.; Taylor, B.; et al. Assignment of epidemiological lineages in an emerging pandemic using the pangolin tool. Virus Evol. 2021, 7, veab064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigeria Centre for Disease Control. COVID-19 NIGERIA. NCDC Coronavirus COVID-19 Microsite. Available online: www.ncdc.org (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Ozer, E.A.; Simons, L.M.; Adewumi, O.M.; Fowotade, A.A.; Omoruyi, E.C.; Adeniji, J.A.; Olayinka, O.A.; Dean, T.J.; Zayas, J.; Bhimalli, P.; et al. Multiple expansions of globally uncommon SARS-CoV-2 lineages in Nigeria. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksamentov, I.; Roemer, C.; Hodcroft, E.B.; Neher, R.A. Nextclade: Clade assignment, mutation calling and quality control for viral genomes. J. Open Source Softw. 2021, 6, 3773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchard, M.A.; Lemey, P.; Baele, G.; Ayres, D.L.; Drummond, A.J.; Rambaut, A. Bayesian phylogenetic and phylodynamic data integration using BEAST 1.10. Virus Evol. 2018, 4, vey016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BEAST Development Team. BEAST X, Version 10.5.0; Zenodo: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Katoh, K.; Misawa, K.; Kuma, K.; Miyata, T. MAFFT: A novel method for rapid multiple sequence alignment based on fast Fourier transform. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 30, 3059–3066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambaut, A.; Lam, T.T.; Max Carvalho, L.; Pybus, O.G. Exploring the temporal structure of heterochronous sequences using TempEst (formerly Path-O-Gen). Virus Evol. 2016, 2, vew007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayres, D.L.; Cummings, M.P.; Baele, G.; Darling, A.E.; Lewis, P.O.; Swofford, D.L.; Huelsenbeck, J.P.; Lemey, P.; Rambaut, A.; Suchard, M.A. BEAGLE 3: Improved performance, scaling, and usability for a high-performance computing library for statistical phylogenetics. Syst. Biol. 2019, 68, 1052–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Smith, D.K.; Zhu, H.; Guan, Y.; Lam, T.T.Y. GGTREE: An R package for visualization and annotation of phylogenetic trees with their covariates and other associated data. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2017, 8, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahata, K.D.; Bielejec, F.; Monetta, J.; Dellicour, S.; Rambaut, A.; Suchard, M.A.; Baele, G.; Lemey, P. SPREAD 4: Online visualisation of pathogen phylogeographic reconstructions. Virus Evol. 2022, 8, veac088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tegally, H.; Wilkinson, E.; Lessells, R.J.; Giandhari, J.; Pillay, S.; Msomi, N.; Mlisana, K.; Bhiman, J.N.; von Gottberg, A.; Walaza, S.; et al. Sixteen novel lineages of SARS-CoV-2 in South Africa. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 440–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- du Plessis, L.; McCrone, J.T.; Zarebski, A.E.; Hill, V.; Ruis, C.; Gutierrez, B.; Raghwani, J.; Ashworth, J.; Colquhoun, R.; Connor, T.R.; et al. Establishment and lineage dynamics of the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic in the UK. Science 2021, 371, 708–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeller, M.; Gangavarapu, K.; Anderson, C.; Smither, A.R.; Vanchiere, J.A.; Rose, R.; Snyder, D.J.; Dudas, G.; Watts, A.; Matteson, N.L.; et al. Emergence of an early SARS-CoV-2 epidemic in the United States. Cell 2021, 184, 4939–4952.e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pak, A.; Adegboye, O.A.; Adekunle, A.I.; Rahman, K.M.; McBryde, E.S.; Eisen, D.P. Economic Consequences of the COVID-19 Outbreak: The Need for Epidemic Preparedness. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, S.A.; Collier, D.A.; Datir, R.P.; Ferreira, I.A.T.M.; Gayed, S.; Jahun, A.; Hosmillo, M.; Rees-Spear, C.; Mlcochova, P.; Lumb, I.U.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 evolution during treatment of chronic infection. Nature 2021, 592, 277–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frampton, D.; Rampling, T.; Cross, A.; Bailey, H.; Heaney, J.; Byott, M.; Scott, R.; Sconza, R.; Price, J.; Margaritis, M.; et al. Genomic characteristics and clinical effect of the emergent SARS-CoV-2 B.1.1.7 lineage in London, UK: A whole-genome sequencing and hospital-based cohort study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 1246–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tegally, H.; Moir, M.; Everatt, J.; Giovanetti, M.; Scheepers, C.; Wilkinson, E.; Subramoney, K.; Makatini, Z.; Moyo, S.; Amoako, D.G.; et al. Emergence of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron lineages BA.4 and BA.5 in South Africa. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 1785–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choga, W.T.; Gustani-Buss, E.; Tegally, H.; Maruapula, D.; Yu, X.; Moir, M.; Zuze, B.J.L.; James, S.E.; Ndlovu, N.S.; Seru, K.; et al. Emergence of Omicron FN.1 a descendent of BQ.1.1 in Botswana. Virus Evol 2024, 10, veae095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dellicour, S.; Hong, S.L.; Vrancken, B.; Chaillon, A.; Gill, M.S.; Maurano, M.T.; Ramaswami, S.; Zappile, P.; Marier, C.; Harkins, G.W.; et al. Dispersal dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 lineages during the first epidemic wave in New York City. PLoS Pathog. 2021, 17, e1009571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variant | Evol Rate | 95% HPD Evol Rate | TMRCA | 95% HPD TMRCA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alpha | 2.66 × 10−4 | 1.67 × 10−4 to 3.47 × 10−4 | July 2020 | Nov. 2018–Sept. 2020 |

| Delta | 3.75 × 10−4 | 4.17 × 10−4 to 7.71 × 10−4 | May 2020 | May 2019–Feb. 2020 |

| Omicron | 4.17 × 10−4 | 2.72 × 10−4 to 7.96 × 10−4 | Dec. 2019 | Sept. 2018–Oct. 2020 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Motayo, B.O.; Oluwasemowo, O.O.; Onoja, A.B.; Akinduti, P.A.; Faneye, A.O. Phylodynamics of SARS-CoV-2 Lineages B.1.1.7, B.1.1.529 and B.1.617.2 in Nigeria Suggests Divergent Evolutionary Trajectories. Pathogens 2025, 14, 1091. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14111091

Motayo BO, Oluwasemowo OO, Onoja AB, Akinduti PA, Faneye AO. Phylodynamics of SARS-CoV-2 Lineages B.1.1.7, B.1.1.529 and B.1.617.2 in Nigeria Suggests Divergent Evolutionary Trajectories. Pathogens. 2025; 14(11):1091. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14111091

Chicago/Turabian StyleMotayo, Babatunde O., Olukunle O. Oluwasemowo, Anyebe B. Onoja, Paul A. Akinduti, and Adedayo O. Faneye. 2025. "Phylodynamics of SARS-CoV-2 Lineages B.1.1.7, B.1.1.529 and B.1.617.2 in Nigeria Suggests Divergent Evolutionary Trajectories" Pathogens 14, no. 11: 1091. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14111091

APA StyleMotayo, B. O., Oluwasemowo, O. O., Onoja, A. B., Akinduti, P. A., & Faneye, A. O. (2025). Phylodynamics of SARS-CoV-2 Lineages B.1.1.7, B.1.1.529 and B.1.617.2 in Nigeria Suggests Divergent Evolutionary Trajectories. Pathogens, 14(11), 1091. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14111091