Abstract

This study was designed to assess the influence of efflux pump activity on the biofilm formation in Salmonella Typhimurium. Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhimurium ATCC 19585 (STWT) and clinically isolated S. Typhimurium CCARM 8009 (STCI) were treated with ceftriaxone (CEF), chloramphenicol (CHL), ciprofloxacin (CIP), erythromycin (ERY), norfloxacin (NOR), and tetracycline (TET) in autoinducer-containing media in the absence and presence of phenylalanine-arginine β-naphthylamide (PAβN) to compare efflux pump activity with biofilm-forming ability. The susceptibilities of STWT and STCI were increased in the presence of PAβN. ERY+PAβN showed the highest decrease in the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of ERY from 256 to 2 μg/mL against STWT and STCI. The antimicrobial activity of NOR against planktonic cells was significantly increased in the presence of PAβN, showing the lowest numbers of STWT (3.2 log CFU/cm2), and the TET+PAβN effectively inhibited the growth of STCI (5.2 log CFU/cm2). The lowest biofilm-forming abilities were observed at NOR+PAβN against STWT (biofilm-forming index, BFI < 0.41) and CEF+PAβN against STCI (BFI = 0.32). The bacteria swimming motility and relative fitness varied depending on the antibiotic and PAβN treatments. The motility diameters of STWT were significantly decreased by NOR+PAβN (6 mm) and TET+PAβN (15 mm), while the lowest motility of STCI was observed at CIP+PAβN (8 mm). The significant decrease in the relative fitness levels of STWT and STCI was observed at CIP+PAβN and NOR+PAβN. The PAβN as an efflux pump inhibitor (EPI) can improve the antimicrobial and anti-biofilm efficacy of antibiotics against S. Typhimurium. This study provides useful information for understanding the role of efflux pump activity in quorum sensing-regulated biofilm formation and also emphasizes the necessity of the discovery of novel EPIs for controlling biofilm formation by antibiotic-resistant pathogens.

1. Introduction

Over the last few decades, antibiotics have been indiscriminately overused and misused in the treatment of infectious diseases. However, the extensive use of antibiotics has accelerated the emergence and spread of multidrug-resistant pathogens, leading to frequent treatment failure due to the limited chemotherapeutic options [1]. Salmonella Typhimurium is highly resistant to various antibiotic classes such as β-lactams and fluoroquinolones, resulting in treatment failure and increased morbidity and mortality [2]. The acquired multidrug resistance in bacteria can be caused by many mechanisms, including reduced membrane permeability, enzymatic modification, target site alteration, protective shield formation, and efflux pump activity [3]. Among these mechanisms, the efflux pumps are known primarily to confer multidrug resistance in bacteria [4]. The multidrug-resistant bacteria can expel different classes of antibiotics through well-developed efflux pump systems such as adenosine triphosphate (ATP)-binding cassette (ABC) superfamily, major facilitator superfamily (MFS), small multidrug resistance (SMR) family, multidrug and toxic compound extrusion (MATE) family, and resistance nodulation division (RND) superfamily [4,5]. The RND efflux pumps as polyspecific transporters are directly responsible for multidrug resistance in Salmonella strains [6].

The antibiotic substrates of single-component efflux pumps pass through the inner membrane into the periplasmic space in Gram-negative bacteria, and the transported antibiotic substrates traverse the outer cell membrane through multiple-component efflux pumps consisting of an inner membrane transporter, periplasmic membrane fusion, and β-barrel channel proteins [7]. In addition, the multidrug efflux pump system has drawn increasing attention as a potential therapeutic target to control biofilm formation [3]. A bacterial cell-to-cell communication system, regulated by a cell density-dependent manner, known as quorum sensing (QS), coordinates the formation of biofilm cells that are highly resistant to antibiotics [3]. Chromobacterium violaceum is commonly known as an acyl-homoserine lactone (AHL) producer, which regulates the production of proteases or pigment compounds such as violacein [8]. The AHLs secreted from C. violaceum can transfer across bacterial cells and induce the QS-controlled virulence and pathogenicity [8]. In addition, the multidrug efflux pumps are involved in the secretion of QS-signaling molecules such as autoinducer 1 (AI-1) and autoinducer 2 (AI-2), which are involved in biofilm formation [5]. Furthermore, the efflux pump-related genes are more expressed in biofilm cells than planktonic cells [9,10]. The overexpression of efflux-related genes corresponds to the overexpression of QS-related genes [11]. Efflux pump inhibitors (EPIs) can block the transport of QS-signaling molecules across membrane channels, resulting in the disruption of biofilm formation [3,12]. Hence, the inhibition of efflux pump expression plays an important role in controlling biofilm formation regulated by QS [13]. However, there is still a lack of knowledge regarding the effect of multidrug efflux pumps on the biofilm formation. Therefore, the aims of this study were to evaluate the antibiotic susceptibility and biofilm-forming ability of Salmonella Typhimurium ATCC 19585 (STWT) and clinically isolated antibiotic-resistant S. Typhimurium CCARM 8009 (STCI) in the presence of phenylalanine-arginine β-naphthylamide (PAβN) and also investigate the relationship between efflux pump activity and biofilm formation of STWT and STCI in C. violaceum-cultured cell-free supernatant (CFS).

2. Results

2.1. Antibiotic Susceptibilities of Salmonella Typhimurium Exposed to Efflux Pump Inhibitor

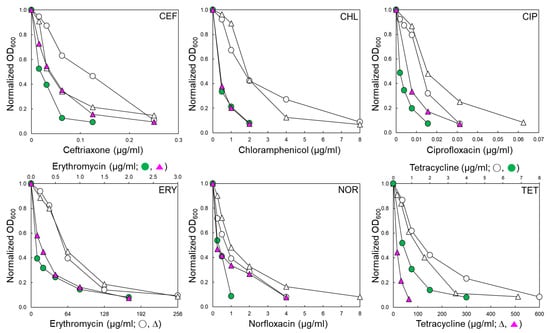

STWT and STCI used in this study have different antibiotic resistance profiles, as shown in Table 1. The antibiotic susceptibilities of STWT and STCI were evaluated in the absence and presence of EPI, phenylalanine-arginine β-naphthylamide (PAβN 120 μg/mL) (Table 1). The antibiotic susceptibility patterns of STWT and STCI exposed to PAβN varied in the classes of antibiotics. The antibiotic activities of ceftriaxone (CEF), chloramphenicol (CHL), ciprofloxacin (CIP), erythromycin (ERY), norfloxacin (NOR), and tetracycline (TET) against STWT and STCI were increased in the presence of PAβN (Figure 1). The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of CEF against STWT was decreased from 0.25 to 0.125 μg/mL when treated with PAβN. Although the growth of STCI was slightly decreased at CEF+PAβN, the addition of PAβN did not affect the MIC of CEF against STCI. The MICs of CHL against STWT and STCI were decreased from 8 to 2 μg/mL in the presence of PAβN. The susceptibilities of STWT and STCI to CIP, ERY, NOR, and TET were increased in the presence of PAβN. The ERY+PAβN showed the highest decrease in the MIC from 256 to 2 μg/mL toward STWT and STCI. The highest MIC was observed for STCI treated with TET (512 μg/mL) and was significantly decreased in the presence of PAβN (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs; µg/mL) of Salmonella Typhimurium ATCC 19585 (STWT) and clinically isolated antibiotic-resistant S. Typhimurium CCARM 8009 (STCI) in the absence and presence of phenylalanine-arginine-b-naphthylamide (PAβN).

Figure 1.

Antibiotic susceptibility of Salmonella Typhimurium ATCC 19585 (STWT; ○, ●) and clinically isolated antibiotic-resistant S. Typhimurium CCARM 8009 (STCI; ∆, ▲) treated with ceftriaxone (CEF), chloramphenicol (CHL), ciprofloxacin (CIP), erythromycin (ERY), norfloxacin (NOR), and tetracycline (TET) in the absence (○, ∆) and presence (●, ▲) of phenylalanine-arginine β-naphthylamide (PAβN).

2.2. Biofilm-Forming Abilities of Salmonella Typhimurium Treated with Antibiotics in the Presence of PAβN

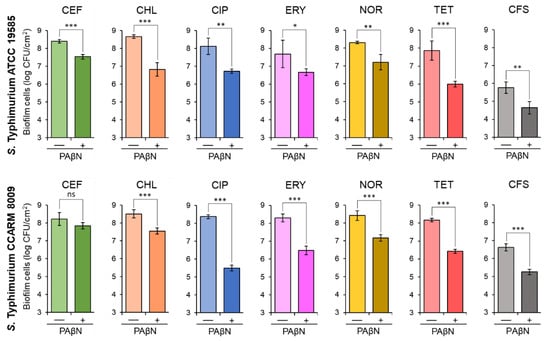

The biofilm-forming abilities of STWT and STCI were evaluated at the sub-MICs of antibiotics, CEF (0.02 and 0.03 μg/mL), CHL (0.5 μg/mL), CIP (0.004 and 0.008 μg/mL), ERY (0.5 μg/mL), NOR (0.25 and 1 μg/mL), and TET (1 and 8 μg/mL), respectively, in the absence and presence of PAβN. The sub-MICs of CEF, CHL, CIP, ERY, NOR, and TET were not effective on the inhibition of biofilm formation of STWT and STCI, which were considerably inhibited in the presence of PAβN (Figure 2). The numbers of biofilm cells formed by STWT and STCI treated with antibiotics alone were approximately 8 log CFU/cm2. However, the addition of PAβN significantly decreased the biofilm-forming abilities of STWT and STCI, showing the noticeable reductions in biofilm cell numbers when treated with CEF+PAβN, CHL+PAβN, CIP+PAβN, ERY+PAβN, NOR+PAβN, and TET+PAβN (Figure 2). In addition, the biofilm-forming abilities of STWT and STCI were evaluated in the cell-free supernatant (CFS) of Chromobacterium violaceum-cultured media with or without PAβN. The number of STWT and STCI biofilm cells in CFS without PAβN were 5.8 and 6.6 log CFU/cm2, respectively, after 24 h of incubation at 37 °C, while the numbers of STWT and STCI biofilm cells in CFS were significantly decreased when treated with PAβN (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Biofilm-forming abilities of Salmonella Typhimurium ATCC 19585 (STWT) and clinically isolated antibiotic-resistant S. Typhimurium CCARM 8009 (STCI) treated with 1/2 MICs of ceftriaxone (CEF), chloramphenicol (CHL), ciprofloxacin (CIP), erythromycin (ERY), norfloxacin (NOR), and tetracycline (TET) in the absence (−) and presence (+) of phenylalanine-arginine β-naphthylamide (PAβN) and the biofilm-forming abilities of STWT and STCI in Chromobacterium violaceum-cultured cell-free supernatant (CFS) in the absence (−) and presence (+) of PAβN. ns, *, **, and *** indicate no significant difference (p > 0.05) and the significant difference between absence and presence of PAβN at p < 0.05, p < 0.01, and p < 0.001, respectively.

2.3. Viability of Salmonella Typhimurium Treated with Antibiotic and PAβN

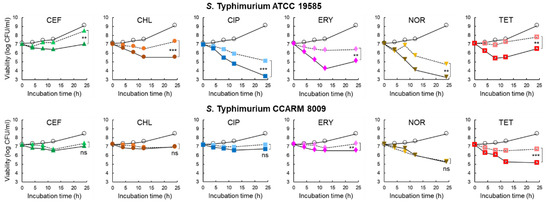

The inhibitory effect of 1/2 MICs of CEF (0.125 and 0.25 μg/mL), CHL (2 and 8 μg/mL), CIP (0.015 and 0.031 μg/mL), ERY (64 and 128 μg/mL), NOR (1 and 4 μg/mL), and TET (4 and 256 μg/mL) on the growth of STWT and STCI, respectively, was evaluated in the CFS of C. violaceum-cultured media with or without PAβN for 24 h at 37 °C. As shown in Figure 3, all antibiotic treatments significantly inhibited the growth of STWT at the early stage of incubation (<12 h). The numbers of STWT treated with CEF and CHL were increased at the late stage of incubation, showing 8.5 and 7.3 log CFU/cm2 after 24 h of incubation, respectively. However, the antibiotic activities of CEF and CHL against STWT were enhanced by PAβN, showing 7.0 log CFU/cm2 at CEF+PAβN and 5.5 log CFU/cm2 at CHL+PAβN, respectively. Compared to the control, CIP+PAβN most effectively inhibited the growth of STWT (3.4 log CFU/cm2) after 24 h of incubation. PAβN restored the antimicrobial activity of ERY against STWT, showing 4.2 log CFU/cm2 at 12 h of incubation. However, the bacterial re-growth was observed for ERY and ERY+PAβN at 24 h of incubation. STWT was susceptible to NOR in the presence of PAβN, showing the lowest number of 3.2 log CFU/cm2. The growth of STWT was significantly decreased by TET (6.9 log CFU/cm2) and TET+PAβN (5.4 log CFU/cm2) at 8 h of incubation. However, the rapid growth of STWT was observed at TET and TET+ PAβN after 12 h of incubation, showing 7.8 and 6.5 log CFU/cm2, respectively (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Survival of Salmonella Typhimurium ATCC 19585 (STWT) and clinically isolated antibiotic-resistant S. Typhimurium CCARM 8009 (STCI) treated with 1/2 MICs of ceftriaxone (CEF), chloramphenicol (CHL), ciprofloxacin (CIP), erythromycin (ERY), norfloxacin (NOR), and tetracycline (TET) in Chromobacterium violaceum-cultured cell-free supernatant (CFS) [○; untreated control, without (▲, ●, ■, ♦, ▼,  ), and with (▲, ●, ■, ♦, ▼,

), and with (▲, ●, ■, ♦, ▼,  ) phenylalanine-arginine β-naphthylamide (PAβN)]. ns, **, and *** indicate no significant difference (p > 0.05) and the significant difference between absence and presence of PAβN at p < 0.05, p < 0.01, and p < 0.001, respectively.

) phenylalanine-arginine β-naphthylamide (PAβN)]. ns, **, and *** indicate no significant difference (p > 0.05) and the significant difference between absence and presence of PAβN at p < 0.05, p < 0.01, and p < 0.001, respectively.

), and with (▲, ●, ■, ♦, ▼,

), and with (▲, ●, ■, ♦, ▼,  ) phenylalanine-arginine β-naphthylamide (PAβN)]. ns, **, and *** indicate no significant difference (p > 0.05) and the significant difference between absence and presence of PAβN at p < 0.05, p < 0.01, and p < 0.001, respectively.

) phenylalanine-arginine β-naphthylamide (PAβN)]. ns, **, and *** indicate no significant difference (p > 0.05) and the significant difference between absence and presence of PAβN at p < 0.05, p < 0.01, and p < 0.001, respectively.

No significant difference in the antimicrobial activities was observed for CEF (7.3 log CFU/cm2) and CEF+PAβN (7.0 log CFU/cm2) against STCI after 24 h of incubation. The numbers of STCI had no significant difference between CHL and CHL+PAβN at the late stage of incubation, showing 7.0 log CFU/cm2 at 24 h of incubation. Compared to the control, the significant decrease in the numbers of STCI was observed at CIP and CIP+PAβN treatments, showing no significant difference between CIP (7.2 log CFU/cm2) and CIP+PAβN (6.7 log CFU/cm2) at 24 h of incubation. PAβN enhanced ERY activity and inhibited the growth of STCI up to 24 h of incubation, showing 6.5 log CFU/cm2 at ERY+PAβN. Compared to the control, the growth of STCI was rapidly decreased to 5.3 and 5.2 log CFU/cm2 by NOR and NOR+PAβN, respectively, after 24 h of incubation. The growth of STCI was significantly decreased by TET+PAβN up to 12 h (5.2 log CFU/cm2), which is the most effective treatment to inhibit the growth of STCI, whereas the steady growth was observed after 12 h of incubation, showing 5.1 log CFU/cm2 (Figure 3).

2.4. Biofilm-Forming Ability, Motility, and Relative Fitness of Salmonella Typhimurium Cultured in Autoinducer-Containing Media

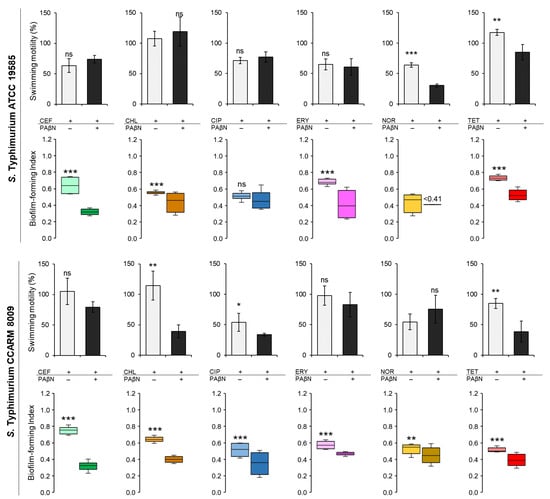

The biofilm-forming abilities and the swimming motilities of STWT and STCI were evaluated in CFS when treated with CEF, CHL, CIP, FRY, NOR, and TET in the absence and presence of PAβN (Figure 4). The biofilm-forming index (BFI < 0.64) of STWT at the combination treatments of antibiotics and PAβN was noticeably decreased when compared to antibiotic alone in the exception of CIP (Figure 4). The presence of PAβN can enhance the anti-biofilm activity of CEF, CHL, CIP, ERY, NOR, and TET against STWT, showing the decrease in BFI to 0.32 at CEF+PAβN, 0.44 at CHL+PAβN, 0.47 at CIP+PAβN, 0.41 at ERY+PAβN, less than 0.41 at NOR+PAβN, and 0.53 at TET+PAβN, respectively. The motility of STWT was varied in treatments. The swimming motilities of STWT treated with antibiotics alone, including CEF (11 mm), CHL (19 mm), CIP (13 mm), and ERY (12 mm), were not significantly different from CEF+PAβN (13 mm), CHL+PAβN (22 mm), CIP+PAβN (14 mm), and ERY+PAβN (11 mm), respectively. However, the motility diameters of STWT were significantly decreased by NOR+PAβN (6 mm) and TET+PAβN (15 mm) when compared to NOR (12 mm) and TET (21 mm) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The biofilm-forming index (BFI) and swimming motility of Salmonella Typhimurium ATCC 19585 (STWT) and clinically isolated antibiotic-resistant S. Typhimurium CCARM 8009 (STCI) treated with 1/2 MICs of ceftriaxone (CEF), chloramphenicol (CHL), ciprofloxacin (CIP), erythromycin (ERY), norfloxacin (NOR), and tetracycline (TET) in Chromobacterium violaceum- cultured cell-free supernatant (CFS). (BFI in the absence (■, ■, ■, ■, ■, ■) and presence (■, ■, ■, ■, ■, ■) of phenylalanine-arginine β-naphthylamide (PAβN) and swimming motility in the absence (□) and presence (■) of PaβN). ns, *, **, and *** indicate no significant difference (p > 0.05) and the significant difference between the absence and presence of PAβN at p < 0.05, p < 0.01, and p < 0.001, respectively.

Compared to the control, the BFI of STCI was decreased in the combination treatments of antibiotics and PAβN (Figure 4). The BFI values of STCI treated with CEF, CHL, CIP, ERY, NOR, and TET were 0.75, 0.64, 0.51, 0.57, 0.53, and 0.51, respectively, while those were decreased to 0.32, 0.40, 0.35, 0.47, 0.45, and 0.39, respectively, after the combination treatments. Regardless of the absence and presence of PAβN, no significant differences in the swimming motility of STCI were observed for each treatment, showing at CEF (24 mm), CEF+PAβN (18 mm), ERY (22 mm), ERY+PAβN (19 mm), NOR (12 mm), and NOR+PAβN (17 mm). The significant decrease in swimming motility of STCI was observed at CHL (26 mm), CHL+PAβN (9 mm), CIP (12 mm), CIP+PAβN (8 mm), TET (19 mm), and TET+PAβN (9 mm) (Figure 4). The relative fitness levels of STWT and STCI treated with CEF, CHL, ERY, and TET were more than 0.9 and 0.7, respectively, which were decreased when treated with PAβN (data not shown). The noticeable reduction in relative fitness of STWT and STCI was observed at CIP+PAβN and NOR+PAβN.

2.5. Correlation between Planktonic Growth and Biofilm Formation of Salmonella Typhimurium Treated with Antibiotics and PAβN

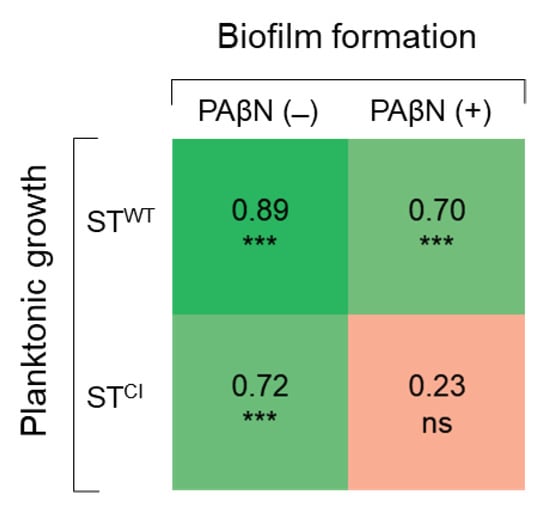

The correlation coefficients between the numbers of planktonic and biofilm cells of STWT and STCI were compared in the absence and presence of PAβN (Figure 5). The planktonic cell numbers were positively correlated with the biofilm cell numbers of STWT (r = 0.89) and STCI (r = 0.72) in the absence of PAβN. STWT planktonic and biofilm cells in the presence of PAβN were highly correlated at 0.70. However, no correlation between STCI planktonic cells and biofilm cells was observed in the presence of PAβN (r = 0.23).

Figure 5.

Correlation matrix of Pearson coefficients between planktonic cell count and biofilm cell counts (n = 24) of Salmonella Typhimurium ATCC 19585 (STWT) and clinically isolated antibiotic-resistant S. Typhimurium CCARM 8009 (STCI) in the absence and presence of PAβN. ns and *** indicate no significance (p > 0.05), significant difference at p < 0.05, p < 0.01, and p < 0.001, respectively.

3. Discussion

This study describes the interplay between efflux pump activity and biofilm formation of STWT and STCI. The bacterial efflux pumps are transmembrane transport proteins targeting multiple substrates, which are known as major determinants of multidrug resistance in bacteria [14]. The RND family is a major efflux pump system in Gram-negative bacteria, which is responsible for intrinsic and acquired resistance to various antibiotics. The AcrAB-TolC belonging to the RND efflux system is the most abundant efflux pump in S. Typhimurium [6]. The loss of AcrB in S. Typhimurium leads to the enhanced susceptibility to quinolones, tetracycline, and chloramphenicol, and the overexpression of acrB contributes to the reduced susceptibility to those antibiotics [15]. In general, AcrB is a substrate-binding trimer anchored in the inner membrane that extends into the periplasm and links with the outer membrane protein TolC, while AcrA is an accessory protein of the functional system [16]. AcrAB-TolC has a binding affinity to multi-substrates such as hydrophilic antibiotics and negatively charged β-lactams [17]. Therefore, the efflux pump systems contribute to the development of antibiotic resistance and also play an important role in the formation of bacterial biofilms [5,13,18]. Several studies have been reported that EPI could be used in a control strategy to inhibit biofilm formation [18,19]. The inhibition of efflux pumps can reduce biofilm formation by interfering with QS-mediated communication within and between strains [20,21,22]. PAβN, a broad-spectrum peptidomimetic inhibitor, inhibits RND efflux pump systems such as AcrAB-TolC of S. Typhimurium [13]. The PAβN competitively binds to the hydrophobic trap of AcrA and AcrB to interrupt the substrate transport pathway [13]. Furthermore, membrane integrity and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) are major target-sites for PAβN, specifically RND-type AcrAB–TolC and MexAB efflux pumps [14]. Therefore, the EPIs can potentiate antibiotic activity against antibiotic-resistant Gram-negative bacteria [23].

The MICs of CEF, CHL, CIP, ERY, NOR, and TET against STWT and STCI were considerably decreased in the presence of PAβN (Figure 1). These results confirm that the efflux pumps are involved in the intrinsic resistance of S. Typhimurium to several classes of antibiotics. This suggests that the antibiotic resistance in S. Typhimurium is associated with the substrate competition-dependent efflux systems [24]. The PAβN noticeably enhanced the ERY activities against STWT and STCI, suggesting that an intrinsic efflux pump activity might use ERY as substrate, leading to ERY resistance. This observation is in good agreement with a previous report that PAβN exhibited the enhanced ERY susceptibility against Gram-negative bacteria [25]. The increased susceptibility to ERY may be attributed to the inhibition of RND efflux, MacAB-TolC, in the presence of PAβN, which is the main resistance mechanism of ERY in S. Typhimurium [26]. The antimicrobial activities of CIP, NOR, and TET against STWT and STCI were enhanced in the presence of PAβN. This observation is in good agreement with a previous report that the MICs of quinolones and tetracyclines were decreased when treated with EPI [25]. Moreover, the deletion of AcrAB-TolC genes resulted in four-fold reduction in the MIC of chloramphenicol, suggesting that AcrAB and TolC proteins, which belong to RND efflux, are important for the development of antibiotic resistance of S. Typhimurium [27]. The overexpression of mdfA and norE could contribute to fluoroquinolone resistance under the overproduction of RND and AcrAB-TolC. In general, the overproduction of AcrAB-TolC increases the MICs of several antibiotics against bacteria. In addition, tetracycline is transported by the MFS and RND efflux systems [28]. This suggests that the inhibition of the RND efflux pump system would be the major contribution to acquiring quinolones and tetracyclines resistance in S. Typhimurium. The major requirement for substrates of the RND efflux pump system is an insertion into the membrane bilayer. For instance, lipophilic side chains are likely to be partitioned into the lipid bilayer of the cytoplasmic membrane, being substrates of the RND efflux pump system [29]. Therefore, the EPIs could effectively enhance the susceptibility to lipophilic antibiotics including chloramphenicol, quinolone, macrolide, and tetracycline. Moreover, the efflux pumps belonging to the RND family are known, as the most effective efflux pump system extrude toxic compounds in S. Typhimurium [15]. Therefore, the competitive binding of PAβN to the RND efflux pump can help control the multidrug-resistant bacteria.

Bacterial biofilms are highly resistant to environmental and chemical stresses such as heat, desiccation, acid, osmotic stress, food preservatives, disinfectants, and antibiotics [4]. The structural integrity of the complex biofilm matrix consisting of DNA, polysaccharides, and proteins provides membrane permeability barrier to antibiotics [30]. Indeed, biofilms are able to induce antibiotic resistance through several mechanisms including permeability disruption, starvation–stress response, and efflux pump activation [31]. In addition, the active efflux and diffusion can be involved in the transport of QS-signaling molecules, leading to the development of biofilm formation in Gram-negative bacteria [3]. The endogenous substrates of RND efflux pumps include fatty acids, natural antibiotics, QS-signaling molecules, and QS precursors [6,32,33]. In general, the biofilm formation of S. Typhimurium is regulated by cell communication process, which is called QS [34]. In a high cell density, bacteria produce and recognize QS-signaling acyl-homoserine lactones (AHLs), called autoinducer (AI), to coordinate gene expression [34]. The extrageneous AI-1 synthesized by various strains and Salmonella self-producing AI-2 can facilitate intra- and interspecies communication within S. Typhimurium biofilms. Therefore, quorum quenching (QQ) can be a possible approach to control bacterial biofilm formation in that QS inhibitors interrupt bacterial communication. Recently, the QQ has drawn more attention to enhance antibiotic susceptibility and eventually inhibit biofilm formation. The biofilm-forming abilities of STWT and STCI were inhibited by CEF, CHL, CIP, ERY, NOR, and TET in the presence of PAβN (Figure 2). The inhibition of biofilm-forming ability resulted in increased antibiotic activity because of the inactivation of efflux pumps developed in STWT and STCI. The sub-MICs of CEF, CHL, CIP, ERY, NOR, and TET can increase the protein level in bacterial membrane compositions and exopolysaccharide production, leading to the antibiotic-induced biofilm formation [35]. However, the addition of PAβN restored the antibiotic activity against STWT and STCI (Figure 2). This suggests that the efflux pumps can use QS-signaling molecules as substrates and eventually inhibit the biofilm formation of S. Typhimurium. The deletion of efflux pump-related genes such as acrB and tolC could cause the loss of curli and extracellular matrix production [36]. The CEF activity against STWT and STCI was increased in the presence of PAβN (Figure 2). This is in good agreement of previous report that ABC transporter is involved in the resistance to β-lactam antibiotics, corresponding to the role of AcrAB–TolC in the enhanced resistance to β-lactam antibiotics [37]. In addition, the RND-type efflux pump, MdsABC, has a broad substrate range, including chloride, cephalosporin, chloramphenicol, and novobiocin [38]. Therefore, the RND efflux pump plays a major role in biofilm formation [16]. The efflux pump-assisted biofilm formation is attributed to the expulsion of extracellular polymeric substances (EPSs) and QS signaling molecules, the regulation of biofilm-related genes, efflux of toxic components, and prevention of cell-to-cell and cell-to-surface adhesion [13,39]. This implies that the RND efflux pump inhibited by PAβN could retard the biofilm formation. The CIP+PAβN and NOR+PAβN decreased the biofilm-forming abilities of STWT and STCI (Figure 2). The QeqA and OqxAB sharing homology with AcrAB and MexAB efflux systems have the ability to hydrolyze fluoroquinolones [40]. Therefore, the reduced biofilm numbers in STWT and STCI treated with CIP or NOR and PAβN might be attributed to QeqA and OqxAB that are specific for fluoroquinolone. This suggests that PAβN could reduce quinolone resistance and restore the quinolone antibiotic activity against Gram-negative bacteria [41]. Moreover, the addition of PAβN also increased the anti-biofilm activity of CHL, ERY, and TET. The reduced biofilm numbers of STWT and STCI treated with CHL, ERY, and TET in the presence of PAβN might be due to the inhibition of mexAB-oprM. This observation implied that the mexAB-oprM efflux pump system is linked to intrinsic resistance to antibiotics such as chloramphenicol, quinolones, macrolides, and tetracycline [42]. MexAB-OprM and MexEF-OprN in Gram-negative bacteria can transport intercellular signals or intermediates during biofilm formation [43]. Therefore, the inhibition of efflux pumps might be a good strategy to effectively inhibit biofilm formation.

Gram-negative bacteria synthesize various N-acyl homoserine lactones (AHLs) in a cell density-dependent manner [44]. In this study, Salmonella can detect AHLs produced by C. violaecium [45]. Salmonella spp. cannot synthesize their own AHLs because of the absence of a luxI homolog but can recognize external AHLs by the receptor, SdiA [44]. The results as given in Figure 2 imply that the biofilm numbers were reduced in CFS containing AHLs when treated with PAβN. This observation suggests that PAβN blocked the transport of AHLs into STWT and STCI, leading to the inhibition of biofilm formation. The RND efflux pump can extrude AHLs such as 3OC12-HSL [46]. For instance, MexCD-OprJ can extrude AIs, resulting in the reduced accumulation of AIs in the bacterial cell [46]. Thus, the inhibition of efflux pumps could affect the AHL transport, leading to the reduced expression of AHL-based QS genes and decrease in biofilm formation.

The sub-MICs of CEF, CHL, CIP, ERY, NOR, and TET could not inhibit the growth of STWT and STCI. No significant differences in the bacterial numbers between the control and antibiotic treatments (Figure 3). The growths of CEF-, CHL-, ERY-, NOR-, and TET-injured STWT and CEF-, CHL-, CIP-, and ERY-stressed STCI were recovered after 12 h, but the recovery rates were significantly lowered in the presence of PAβN. The growths of STWT and STCI were most effectively inhibited by the antibiotics combined with PAβN throughout the incubation period. The decrease in the numbers of bacteria treated with the combination of antibiotics and EPI suggests that the efflux pumps are associated with the innate resistance in S. Typhimurium. However, the mechanisms of resistance of bacteria to β-lactams and chloramphenicol are also associated with β-lactamases-mediated hydrolysis, porin channels, and efflux pump activity [47]. The change in the porin channel influences membrane permeability as an access barrier to antibiotics such as β-lactams and quinolones [47]. The growths of STCI treated with CEF, CEF+PAβN, CHL, and CHL+PAβN were steady constant regardless of the levels of efflux pump activities (Figure 3). Compared to the control, the numbers of STWT and STCI treated with CIP, ERY, and TET were reduced in the presence of PAβN up to 12 h of incubation (Figure 4). This result implies that the efflux pump can extrude antibiotics such as macrolides, tetracyclines, and quinolones as substrates. Moreover, the mechanism of resistance of bacteria to fluoroquinolones is caused by mutations in DNA-gyrase and topoisomerase IV, altered permeability, and active efflux pump [48]. The fluoroquinolone efflux pump system of S. Typhimurium is encoded by the AcrAB homologous protein [49]; thus, PAβN can effectively enhance the antibiotic activities of CIP and NOR against STWT and STCI (Figure 3).

The biofilm-forming abilities of STWT and STCI in CFS containing AHLs are shown in Figure 4. The combination treatments of antibiotics and PAβN showed a lower biofilm-forming index (BFI) than the single antibiotic treatments (Figure 4). The combination of antibiotics and PAβN can synergistically inhibit QS, resulting in the inhibition of biofilm formation. This observation is in good agreement with previous study that the combinations of EPI with fluoroquinolones effectively inhibited QS and biofilm formation [50]. The inhibition of efflux pump in CFS media may be related to the decrease in transport of AHLs, leading to the inhibition of biofilm formation. The lowest BFI was observed in STCI treated with CEF+PAβN (0.32), which was followed by CIP+PAβN (0.35) and TET+PAβN (0.39) (Figure 4). This indicates that EPIs are effective at inhibiting biofilm formation under low concentrations of antibiotics and even enhance the therapeutic potential of low doses of antibiotics. The extrusion of QS-signaling molecules causes an increased concentration of extracellular self-inducers, leading to serious bacterial infection [51]. Thus, certain efflux pumps have a role in modifying both the QS response and pathogenicity in bacteria [18]. In addition, during the infection, pathogenic bacteria can produce a variety of virulence factors such as toxins, outer membrane proteins, or biofilm to invade the host or evade the host immune system [52]. Among virulence factors produced by Gram-negative bacteria, the production of QS-regulated virulence factors plays an important role in biofilm formation. For example, the production of pyocyanin and rhamnolipids from the QS system is responsible for the deposition of extracellular DNA [19]. This indicates that the high efflux pump activity may promote the QS system, leading to the synthesis of several virulence factors and the increase in bacterial pathogenicity. This confirms that the bacterial efflux pumps and QS system are involved in the regulation of biofilm formation. Therefore, the inhibition of bacterial efflux pumps can restore antibiotic activity, leading to the disruption of biofilm formation [14].

STWT treated with NOR+PAβN showed the lowest motility when compared to other treatments (Figure 4). At the early stages of biofilm formation, swimming motility plays an important role in bacterial translocation and adhesion to the surface [53]. This indicates that the reduced motility in the presence of PAβN may result in the decreased ability of STWT to form biofilms. However, the lowest swimming motility of STCI was observed at CIP+PAβN, but the lowest BFI was observed at CEF+PAβN (Figure 4). This implies that the swimming motility was not directly correlated with the biofilm-forming ability of STCI in the presence of PAβN. The relative fitness levels of STWT and STCI treated with antibiotics were comparably decreased in the presence of PAβN, in other words reflecting the increase in fitness cost. In general, bacteria can quickly adapt to new challenges and subsequently continue to optimize their fitness [54]. The antibiotic-resistant bacteria have relatively low fitness under favorable conditions [55]. In addition, bacteria with low efflux pump activity might have a higher fitness cost than bacteria with high efflux pump activity [56]. In particular, genes involved in peptidoglycan synthesis or efflux control were detected more often in populations with low fitness [57]. Therefore, bacteria with a low fitness cost are more likely to develop antibiotic resistance because of a fitness advantage [54]. Furthermore, the accumulation of compensatory mutations can restore the bacterial fitness and decrease the fitness cost in antibiotic-resistant bacteria [58]. Thus, the fitness cost is associated with bacterial evolution and the maintenance of antibiotic resistance. The planktonic cell and biofilm cell numbers of STWT (r = 0.89) and STCI (r = 0.72) were highly correlated in the absence of PAβN. The numbers of active planktonic cells are associated with the surface-attached growth during biofilm maturation [59]. The adhesion of planktonic cells to an abiotic or biotic surface is critical at the early stage of biofilm formation [60]. The efflux pumps may be involved in biofilm formation such as the transport of extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) or QS signaling to facilitate biofilm matrix formation. Therefore, the inhibition of an efflux pump could also inhibit biofilm formation. No significant correlation was observed between STCI planktonic and biofilm cell numbers in the presence of PAβN (r = 0.23). This result suggests that the viability of planktonic cells was not influenced by PaβN, and the reduction in the biofilm cells was related to the inhibition of efflux pump developed in STCI.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Bacterial Strains and Culture Conditions

Strains of Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhimurium ATCC 19585 (STWT) and clinically isolated antibiotic-resistant S. Typhimurium CCARM 8009 (STCI) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, VA, USA) and the Culture Collection of Antibiotic Resistant Microbes (CCARM; Seoul, Korea), respectively. Chromobacterium violaceum KACC 11542 was obtained from the Korean Agricultural Culture Collection (KACC; Seoul, Korea). Strains of STWT and STCI were cultivated in trypticase soy broth (TSB; Difco, BD, Sparks, MD, USA) at 37 °C for 20 h. C. violaceum was cultivated in Luria–Bertani (LB; Difco, BD, Sparks, MD, USA) broth at 26 °C for 20 h. The cultured cells were harvested by centrifugation at 6000× g for 10 min and diluted with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.2) to approximately 108 CFU/mL for assays.

4.2. Antibiotic Susceptibility Assay

The susceptibilities of STWT and STCI to antibiotics and efflux pump inhibitor (EPI) were determined according to the Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute procedure with minor modifications [61]. Antibiotics (Table 1) including ceftriaxone (CEF), chloramphenicol (CHL), ciprofloxacin (CIP), erythromycin (ERY), norfloxacin (NOR), tetracycline (TET), and EPI (phenylalanine-arginine β-naphthylamide, PAβN) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich Chemicals (St. Louis, MO, USA). Antibiotic and EPI stock solutions were prepared by dissolving in sterile distilled water (CEF), ethanol (CHL, ERY, and TET), glacial acetic acid (CIP and NOR), and methanol (PAβN), respectively, at a concentration of 10.24 mg/mL. Each antibiotic stock solution (100 μL) was serially (1:2) diluted to concentrations ranging from 512 to 0.015 μg/mL in fresh TSB without and with PAβN at the pre-determined sub-minimum inhibitory concentrations (sub-MIC; 120 μg/mL) in 96-well microtiter plates (BD Falcon, San Jose, CA, USA). Each strain (105 CFU/mL, 100 μL) was inoculated in the diluted antibiotic with EPI (1:2) and incubated at 37 °C for 18 h to determine MIC defined as the lowest concentrations of antibiotics where no visible bacterial growths were observed.

4.3. Biofilm-Forming Ability Assay

The biofilm-forming abilities of STWT and STCI (106 CFU/mL each) treated with CEF, CHL, CIP, ERY, NOR, and TET were evaluated in the absence and presence of PAβN (120 μg/mL). The concentrations were determined at the 1/2 MICs of all antibiotics in the presence of PAβN, including CEF (0.0625 and 0.125 μg/mL), CHL (1 and 1 μg/mL), CIP (0.0078 and 0.0156 μg/mL), ERY (1 and 1 μg/mL), NOR (0.5 and 2 μg/mL), and TET (2 and 32 μg/mL) against STWT and STCI, respectively. The biofilm cells were enumerated using a swabbing method with slight modification [62,63]. The test strains were also cultured in C. violaceum-cultured cell-free supernatant (CFS) in the absence and presence of PAβN (120 μg/mL). In brief, after 24 h of incubation at 37 °C, the biofilm cells were collected from the 96-well microtiter plates. Each well of the 96-well microtiter plate was gently rinsed two times with PBS to remove planktonic cells and scraped using a water-moistened sterile cotton swab. The collected biofilm cells harvested by centrifugation at 5000× g for 10 min at 4 °C were serially (1:10) diluted with PBS, plated on the TSA using an Autoplate® Spiral Plating System (Spiral Biotech Inc., Norwood, MA, USA) and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. The biofilm cell numbers were enumerated using a QCount® Colony Counter (Spiral Biotech Inc.).

4.4. Growth-Based Bacterial Viability Assay

The antimicrobial activities of single antibiotic and combination treatments of antibiotics and PAβN against STWT and STCI were evaluated in TSB at 37 °C for 24 h. The initial population (107 CFU/mL) of STWT and STCI was inoculated at 37 °C in C. violaceum-cultured CFS with 1/2 MICs of antibiotics in the absence and presence of PAβN (120 μg/mL). The antibiotics concentrations were 0.125 μg/mL CEF, 4 μg/mL CHL, 0.0156 μg/mL CIP, 128 μg/mL ERY, 2 μg/mL NOR, and 4 μg/mL TET for STWT in absence of PAβN, 0.0625 μg/mL CEF, 1 μg/mL CHL, 0.0078 μg/mL CIP, 1 μg/mL ERY, 0.5 μg/mL NOR, and 2 μg/mL TET for STWT in presence of PAβN, 0.125 μg/mL CEF, 4 μg/mL CHL, 0.03125 μg/mL CIP, 128 μg/mL ERY, 4 μg/mL NOR, and 256 μg/mL TET for STCI in the absence of PAβN, and 0.125 μg/mL CEF, 1 μg/mL CHL, 0.0156 μg/mL CIP, 1 μg/mL ERY, 2 μg/mL NOR, and 32 μg/mL TET for STCI in the presence of PAβN. The inoculated samples were incubated for 0, 4, 8, 12, and 24 h at 37 °C. After incubation, the collected planktonic cells were serially (1:10) diluted with PBS. Proper dilutions were plated on the TSA and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. Viable cell numbers were enumerated as described above.

4.5. Biofilm-Forming Ability in CFS

STWT and STCI (107 CFU/mL each) were cultured in C. violaceum-cultured CFS with 1/2 MICs of CEF, CHL, CIP, ERY, NOR, and TET with and without PAβN (120 μg/mL) in a 96-well plate. After incubation at 37 °C for 24 h, the cultures were centrifuged at 5000× g for 10 min at 4 °C to collect planktonic cells. Each well was rinsed with PBS, and biofilm cells were collected by using a cotton swab and centrifuged at 5000× g for 10 min at 4 °C. The planktonic and biofilm cells were enumerated as described above. The biofilm-forming index (BFI) was expressed as the ratio of number of planktonic cells to that of biofilm cells [64].

4.6. Swimming Motility Assay

Flagellum-dependent movement was determined by the swimming motility assay [65]. STWT and STCI cells were treated with 1/2 MICs of CEF, CHL, CIP, ERY, NOR, and TET in the presence and absence of PAβN (120 μg/mL) and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. The planktonic cells (5 mL; 103 CFU/mL) were collected and seeded onto the center of the surface of 0.3% agar-containing plates. After 12 h of incubation at 37 °C, the bacterial migration on each plate was measured using a digital vernier caliper (The L.S. Starrett Co., Athol, MA, USA).

4.7. Measurement of Relative Fitness

The relative fitness was estimated to assess the cost of resistance of STWT and STCI cells treated with 1/2 MICs of CEF, CHL, CIP, ERY, NOR, and TET in the presence and absence of PAβN (120 μg/mL) for 24 h. Then, the antibiotic-treated planktonic cells were collected by centrifugation at 5000× g for 10 min at 4 °C, rinsed two times with PBS, and cultured at 37 °C for 24 h in fresh TSB in the absence of antibiotics and PAβN. The relative fitness was expressed as the ratio of the growth (OD600) of treated cells to that of untreated control in the absence of antibiotics.

4.8. Statistical Analysis

All experiments were carried out in duplicate on three replicates. Data were analyzed using the Statistical Analysis System (SAS). The general linear model (GLM) and Fisher’s least significant difference (LSD) procedures were used to determine significant differences between treatments at p < 0.05, p < 0.01, and p < 0.001. The correlations between planktonic and biofilm cells were evaluated using Pearson’s correlation coefficient.

5. Conclusions

This study highlights the effect of efflux pump activity on the biofilm formation of S. Typhimurium. The most significant findings were that (1) the MICs of CEF, CHL, CIP, ERY, NOR, and TET against STWT and STCI were decreased in the presence of PAβN, (2) the sub-MICs of CEF, CHL, CIP, ERY, NOR, and TET were not effective in the inhibition of biofilm formation of STWT and STCI and, (3) PAβN significantly increased the inhibitory activity of sub-MICs of CEF, CHL, CIP, ERY, NOR, and TET on the biofilm formation by STWT and STCI. The NOR+PAβN and CEF+PAβN treatments showed the highest anti-biofilm activity against STWT and STCI, respectively. The inhibition of efflux pump by EPIs can interfere with the transport of quorum-sensing molecules, leading to the decrease in biofilm-forming abilities of pathogens. PaβN have no effect on the viability of planktonic cells but only inhibited biofilm formation. The use of antibiotics combined with EPIs has a great potential of controlling biofilm formation. Accordingly, EPIs can be used as a potential control agent to inhibit biofilm formation by pathogens.

Author Contributions

J.D. and Y.L. conducted all experiments and also wrote the manuscript. F.L., X.H., and J.A. designed the experiment and contributed to the data analysis. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (NRF-2016R1D1A3B01008304).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ugwuanyi, F.C.; Ajayi, A.; Ojo, D.A.; Adeleye, A.I.; Smith, S.I. Evaluation of efflux pump activity and biofilm formation in multidrug resistant clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from a Federal Medical Center in Nigeria. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2021, 20, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawan, J.; Ahn, J. Effectiveness of antibiotic combination treatments to control heteroresistant Salmonella Typhimurium. Microb. Drug Resist. 2021, 27, 441–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reza, A.; Sutton, J.M.; Rahman, K.M. Effectiveness of efflux pump inhibitors as biofilm disruptors and resistance breakers in Gram-negative (ESKAPEE) bacteria. Antibiotics 2019, 8, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martins, M.; Viveiros, M.; Couto, I.; Costa, S.S.; Pacheco, T.; Fanning, S.; Pages, J.-M.; Amaral, L. Identification of efflux pump-mediated multidrug-resistant bacteria by the ethidium bromide-agar cartwheel method. In Vivo 2011, 25, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Aybey, A.; Usta, A.; Demirkan, E. Effects of psychotropic drugs as bacterial efflux inhibitors on quorum sensing regulated behaviors. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. Food Sci. 2014, 4, 128–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colclough, A.L.; Alav, I.; Whittle, E.E.; Pugh, H.L.; Darby, E.M.; Legood, S.W.; McNeil, H.E.; Blair, J.M. RND efflux pumps in Gram-negative bacteria; regulation, structure and role in antibiotic resistance. Future Microbiol. 2020, 15, 143–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zgurskaya, H.I.; Malloci, G.; Chandar, B.; Vargiu, A.V.; Ruggerone, P. Bacterial efflux transporters’ polyspecificity-A gift and a curse? Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2021, 61, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mion, S.; Carriot, N.; Lopez, J.; Plener, L.; Ortalo-Magné, A.; Chabrière, E.; Culioli, G.; Daudé, D. Disrupting quorum sensing alters social interactions in Chromobacterium violaceum. Biofilm. Microb. 2021, 7, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schembri, M.A.; Kjaergaard, K.; Klemm, P. Global gene expression in Escherichia coli biofilms. Mol. Microbiol. 2003, 48, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waite, R.D.; Papakonstantinopoulou, A.; Littler, E.; Curtis, M.A. Transcriptome analysis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa growth: Comparison of gene expression in planktonic cultures and developing and mature biofilms. J. Bacteriol. 2005, 187, 6571–6576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rahmati, S.; Yang, S.; Davidson, A.L.; Zechiedrich, E.L. Control of the AcrAB multidrug efflux pump by quorum-sensing regulator SdiA. Mol. Microbiol. 2002, 43, 677–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pages, J.M.; Amaral, L. Mechanisms of drug efflux and strategies to combat them: Challenging the efflux pump of Gram-negative bacteria. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2009, 1794, 826–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alav, I.; Sutton, J.M.; Rahman, K.M. Role of bacterial efflux pumps in biofilm formation. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2018, 73, 2003–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sun, J.; Deng, Z.; Yan, A. Bacterial multidrug efflux pumps: Mechanisms, physiology and pharmacological exploitations. Biochem. Biophysic. Res. Commun. 2014, 453, 254–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Baucheron, S.; Tyler, S.; Boyd, D.; Mulvey, M.R.; Chaslus-Dancla, E.; Cloeckaert, A. AcrAB-TolC directs efflux-mediated multidrug resistance in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium DT104. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2004, 48, 3729–3735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Blair, J.M.; Piddock, L.J. Structure, function and inhibition of RND efflux pumps in Gram-negative bacteria: An update. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2009, 12, 512–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, E.W.; Aires, J.R.; McDermott, G.; Nikaido, H. A periplasmic drug-binding site of the AcrB multidrug efflux pump: A crystallographic and site-directed mutagenesis study. J. Bacteriol. 2005, 187, 6804–6815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Piddock, L.J. Multidrug-resistance efflux pumps-not just for resistance. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2006, 4, 629–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, D.; Han, X.; Du, W.; Kou, Z.; Jiang, F. Trp-containing antibacterial peptides impair quorum sensing and biofilm development in multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa and exhibit synergistic effects with antibiotics. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 611009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baugh, S.; Phillips, C.R.; Ekanayaka, A.S.; Piddock, L.J.; Webber, M.A. Inhibition of multidrug efflux as a strategy to prevent biofilm formation. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2014, 69, 673–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sabatini, S.; Piccioni, M.; Felicetti, T.; De Marco, S.; Manfroni, G.; Pagiotti, R.; Nocchetti, M.; Cecchetti, V.; Pietrella, D. Investigation on the effect of known potent S. aureus NorA efflux pump inhibitors on the staphylococcal biofilm formation. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 37007–37014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Acker, H.; Coenye, T. The role of efflux and physiological adaptation in biofilm tolerance and resistance. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 12565–12572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Siriyong, T.; Srimanote, P.; Chusri, S.; Yingyongnarongkul, B.E.; Suaisom, C.; Tipmanee, V.; Voravuthikunchai, S.P. Conessine as a novel inhibitor of multidrug efflux pump systems in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2017, 17, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagès, J.-M.; Masi, M.; Barbe, J. Inhibitors of efflux pumps in Gram-negative bacteria. Trends Mol. Med. 2005, 11, 382–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurincic, M.; Klancnik, A.; Smole Mozina, S. Effects of efflux pump inhibitors on erythromycin, ciprofloxacin, and tetracycline resistance in Campylobacter spp. isolates. Microb. Drug Resist. 2012, 18, 492–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogomolnaya, L.M.; Andrews, K.D.; Talamantes, M.; Maple, A.; Ragoza, Y.; Vazquez-Torres, A.; Andrews-Polymenis, H. The ABC-type efflux pump MacAB protects Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium from oxidative stress. Mbio 2013, 4, e00630-13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nishino, K.; Latifi, T.; Groisman, E.A. Virulence and drug resistance roles of multidrug efflux systems of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Mol. Microbiol. 2006, 59, 126–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, H.I.; Kim, S.; Oh, M.H.; Na, S.H.; Kim, Y.J.; Jeon, Y.H.; Lee, J.C. Outer membrane protein A contributes to antimicrobial resistance of Acinetobacter baumannii through the OmpA-like domain. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2017, 72, 3012–3015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikaido, H.; Basina, M.; Nguyen, V.; Rosenberg, E.Y. Multidrug efflux pump AcrAB of Salmonella typhimurium excretes only those beta-lactam antibiotics containing lipophilic side chains. J. Bacteriol. 1998, 180, 4686–4692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Siala, W.; Kucharikova, S.; Braem, A.; Vleugels, J.; Tulkens, P.M.; Mingeot-Leclercq, M.P.; Van Dijck, P.; Van Bambeke, F. The antifungal caspofungin increases fluoroquinolone activity against Staphylococcus aureus biofilms by inhibiting N-acetylglucosamine transferase. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 13286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, S.M. Role of efflux pumps in the antibiotic resistance of bacteria embedded in a biofilm. Virulence 2013, 4, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Abisado, R.G.; Benomar, S.; Klaus, J.R.; Dandekar, A.A.; Chandler, J.R. Bacterial quorum sensing and microbial community interactions. Mbio 2018, 9, e02331-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Henderson, P.J.F.; Maher, C.; Elbourne, L.D.H.; Eijkelkamp, B.A.; Paulsen, I.T.; Hassan, K.A. Physiological functions of bacterial multidrug efflux pumps. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 5417–5478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kendall, M.M.; Sperandio, V. Cell-to-cell signaling in Escherichia coli and Salmonella. EcoSal Plus 2014, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nucleo, E.; Steffanoni, L.; Fugazza, G.; Migliavacca, R.; Giacobone, E.; Navarra, A.; Pagani, L.; Landini, P. Growth in glucose-based medium and exposure to subinhibitory concentrations of imipenem induce biofilm formation in a multidrug-resistant clinical isolate of Acinetobacter baumannii. BMC Microbiol. 2009, 9, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Baugh, S.; Ekanayaka, A.S.; Piddock, L.J.; Webber, M.A. Loss of or inhibition of all multidrug resistance efflux pumps of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium results in impaired ability to form a biofilm. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2012, 67, 2409–2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Danilchanka, O.; Mailaender, C.; Niederweis, M. Identification of a novel multidrug efflux pump of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2008, 52, 2503–2511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Andersen, J.L.; He, G.-X.; Kakarla, P.; Ranjana, K.C.; Kumar, S.; Lakra, W.S.; Mukherjee, M.M.; Ranaweera, I.; Shrestha, U.; Tran, T.; et al. Multidrug efflux pumps from Enterobacteriaceae, Vibrio cholerae and Staphylococcus aureus bacterial food pathogens. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 1487–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kvist, M.; Hancock, V.; Klemm, P. Inactivation of efflux pumps abolishes bacterial biofilm formation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 74, 7376–7382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hansen, L.H.; Johannesen, E.; Burmølle, M.; Sørensen, A.H.; Sørensen, S.J. Plasmid-encoded multidrug efflux pump conferring resistance to olaquindox in Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2004, 48, 3332–3337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Corcoran, D.; Quinn, T.; Cotter, L.; Fanning, S. Relative contribution of target gene mutation and efflux to varying quinolone resistance in Irish Campylobacter isolates. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2005, 253, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horna, G.; Lopez, M.; Guerra, H.; Saenz, Y.; Ruiz, J. Interplay between MexAB-OprM and MexEF-OprN in clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 16463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakhtah, H.; Koyama, L.; Zhang, Y.; Morales, D.K.; Fields, B.L.; Price-Whelan, A.; Hogan, D.A.; Shepard, K.; Dietrich, L.E. The Pseudomonas aeruginosa efflux pump MexGHI-OpmD transports a natural phenazine that controls gene expression and biofilm development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, E3538–E3547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Janssens, J.C.; Steenackers, H.; Robijns, S.; Gellens, E.; Levin, J.; Zhao, H.; Hermans, K.; De Coster, D.; Verhoeven, T.L.; Marchal, K.; et al. Brominated furanones inhibit biofilm formation by Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 74, 6639–6648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Burt, S.A.; Ojo-Fakunle, V.T.; Woertman, J.; Veldhuizen, E.J. The natural antimicrobial carvacrol inhibits quorum sensing in Chromobacterium violaceum and reduces bacterial biofilm formation at sub-lethal concentrations. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e93414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Minagawa, S.; Inami, H.; Kato, T.; Sawada, S.; Yasuki, T.; Miyairi, S.; Horikawa, M.; Okuda, J.; Gotoh, N. RND type efflux pump system MexAB-OprM of Pseudomonas aeruginosa selects bacterial languages, 3-oxo-acyl-homoserine lactones, for cell-to-cell communication. BMC Microbiol. 2012, 12, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pages, J.-M.; Lavigne, J.-P.; Leflon-Guibout, V.; Marcon, E.; Bert, F.; Noussair, L.; Nicolas-Chanoine, M.-H. Efflux pump, the masked side of beta-lactam resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae clinical isolates. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e4817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Navarro Risueño, F.; Miró Cardona, E.; Mirelis Otero, B. Lectura interpretada del antibiograma de enterobacterias. Enferm. Infecc. Microbiol. Clin. 2002, 20, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giraud, E.; Cloeckaert, A.; Kerboeuf, D.; Chaslus-Dancla, E. Evidence for active efflux as the primary mechanism of resistance to ciprofloxacin in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2000, 44, 1223–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bortolotti, D.; Trapella, C.; Bragonzi, A.; Marchetti, P.; Zanirato, V.; Alogna, A.; Gentili, V.; Cervellati, C.; Valacchi, G.; Sicolo, M.; et al. Conjugation of LasR quorum-sensing inhibitors with ciprofloxacin decreases the antibiotic tolerance of P. aeruginosa clinical strains. J. Chem. 2019, 2019, 8143739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, X.Z.; Plesiat, P.; Nikaido, H. The challenge of efflux-mediated antibiotic resistance in Gram-negative bacteria. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2015, 28, 337–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cepas, V.; Soto, S.M. Relationship between virulence and resistance among Gram-negative bacteria. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pratt, L.A.; Kolter, R. Genetic analyses of bacterial biofilm formation. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 1999, 2, 598–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.; Abdelraouf, K.; Ledesma, K.R.; Nikolaou, M.; Tam, V.H. Predicting bacterial fitness cost associated with drug resistance. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2012, 67, 928–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lin, W.; Zeng, J.; Wan, K.; Lv, L.; Guo, L.; Li, X.; Yu, X. Reduction of the fitness cost of antibiotic resistance caused by chromosomal mutations under poor nutrient conditions. Environ. Int. 2018, 120, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebbensgaard, A.E.; Lobner-Olesen, A.; Frimodt-Moller, J. The role of efflux pumps in the transition from low-level to clinical antibiotic resistance. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, C.; Trebosc, V.; Kemmer, C.; Rosenstiel, P.; Beardmore, R.; Schulenburg, H.; Jansen, G. Alternative evolutionary paths to bacterial antibiotic resistance cause distinct collateral effects. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2017, 34, 2229–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Andersson, D.I.; Hughes, D. Antibiotic resistance and its cost: Is it possible to reverse resistance? Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2010, 8, 260–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bester, E.; Edwards, E.A.; Wolfaardt, G.M. Planktonic cell yield is linked to biofilm development. Can. J. Microbiol. 2009, 55, 1195–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armbruster, C.R.; Parsek, M.R. New insight into the early stages of biofilm formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 4317–4319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- CLSI. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing; Twenty-ninth Informational Supplement; CLSI: Wayne, PA, USA, 2019; Volume M100. [Google Scholar]

- Chae, M.S.; Schraft, H. Cell viability of Listeria monocytogenes biofilms. Food Microbiol. 2001, 18, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Zou, Y.; Lee, H.Y.; Ahn, J. Effect of NaCl on the biofilm formation by foodborne pathogens. J. Food Sci. 2010, 75, M580–M585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall-Stoodley, L.; Nistico, L.; Sambanthamoorthy, K.; Dice, B.; Nguyen, D.; Mershon, W.J.; Johnson, C.; Hu, F.Z.; Stoodley, P.; Ehrlich, G.D.; et al. Characterization of biofilm matrix, degradation by DNase treatment and evidence of capsule downregulation in Streptococcus pneumoniae clinical isolates. BMC Microbiol. 2008, 8, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Calvio, C.; Celandroni, F.; Ghelardi, E.; Amati, G.; Salvetti, S.; Ceciliani, F.; Galizzi, A.; Senesi, S. Swarming differentiation and swimming motility in Bacillus subtilis are controlled by swrA, a newly identified dicistronic operon. J. Bacteriol. 2005, 187, 5356–5366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).