Differential Expression of Mitosis and Cell Cycle Regulatory Genes during Recovery from an Acute Respiratory Virus Infection

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Mice

2.2. Inoculation with PVM and Immunobiotic L. plantarum

2.3. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assays (ELISAs)

2.4. Measurements of Airway Resistance

2.5. RNA Extraction from Whole Lung Tissue

2.6. RNA Sequencing

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

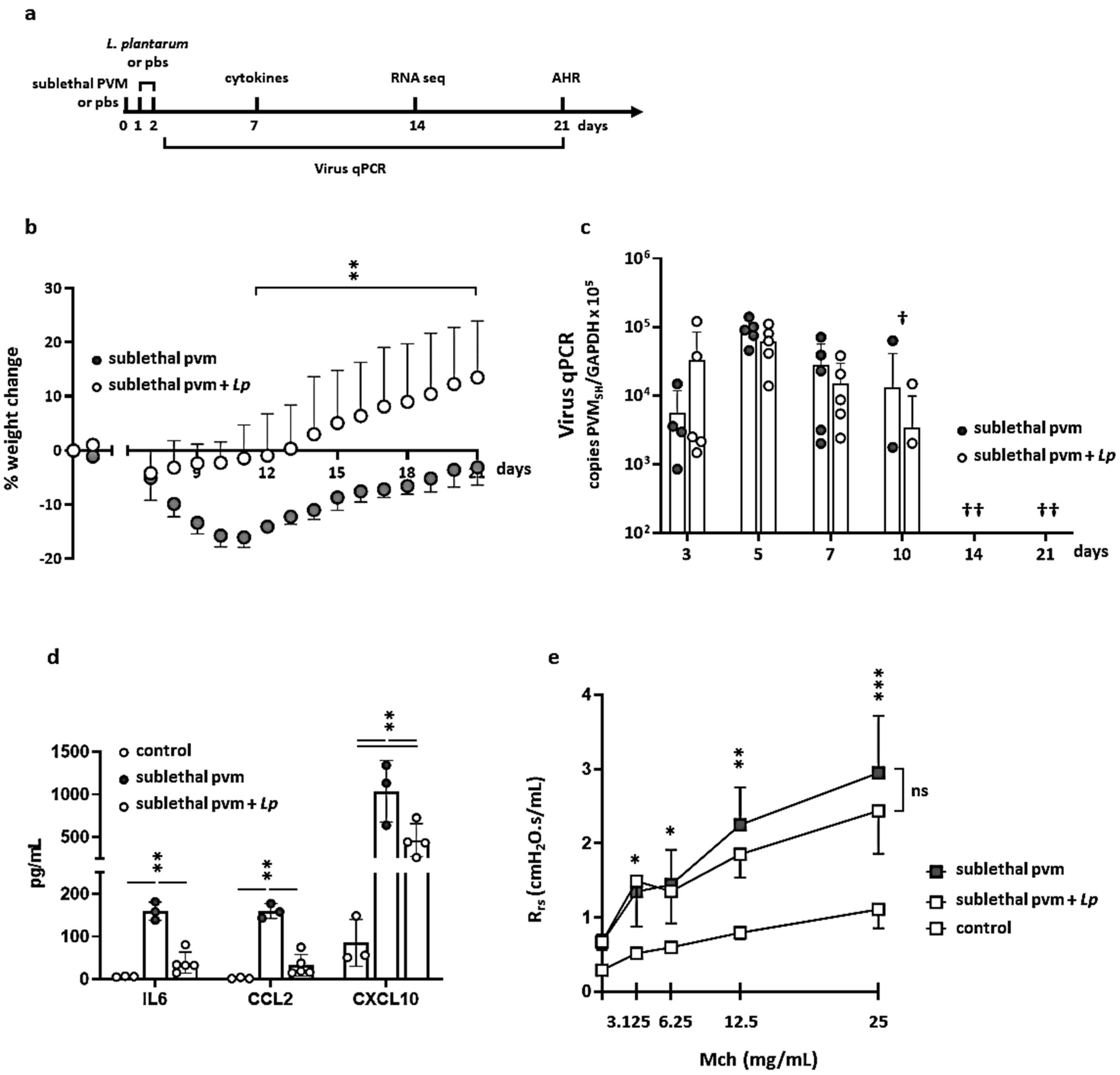

3.1. Impact of L. plantarum in Mice with Sublethal PVM Infection

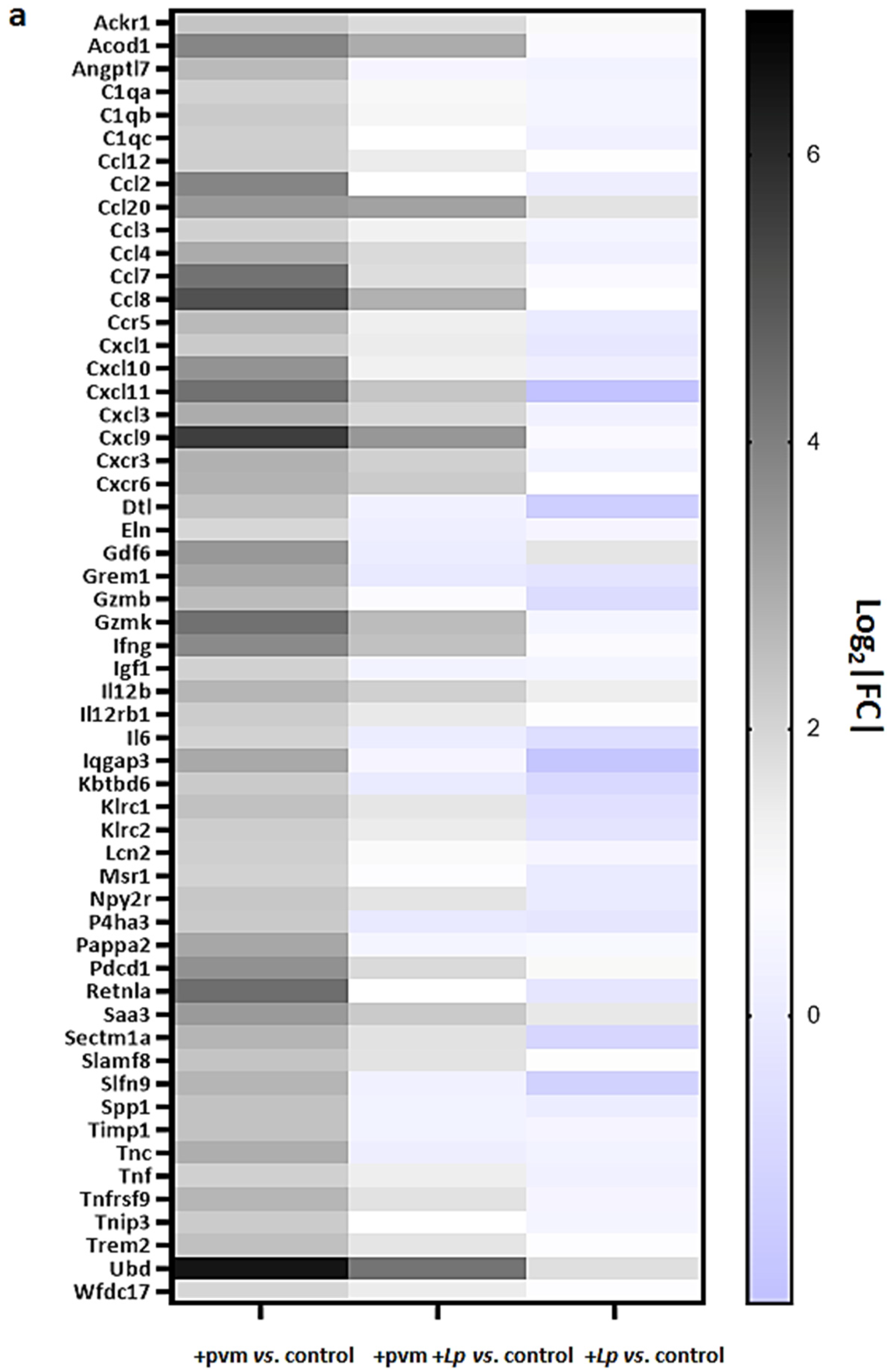

3.2. Gene Expression during Recovery from an Acute Sublethal PVM Infection

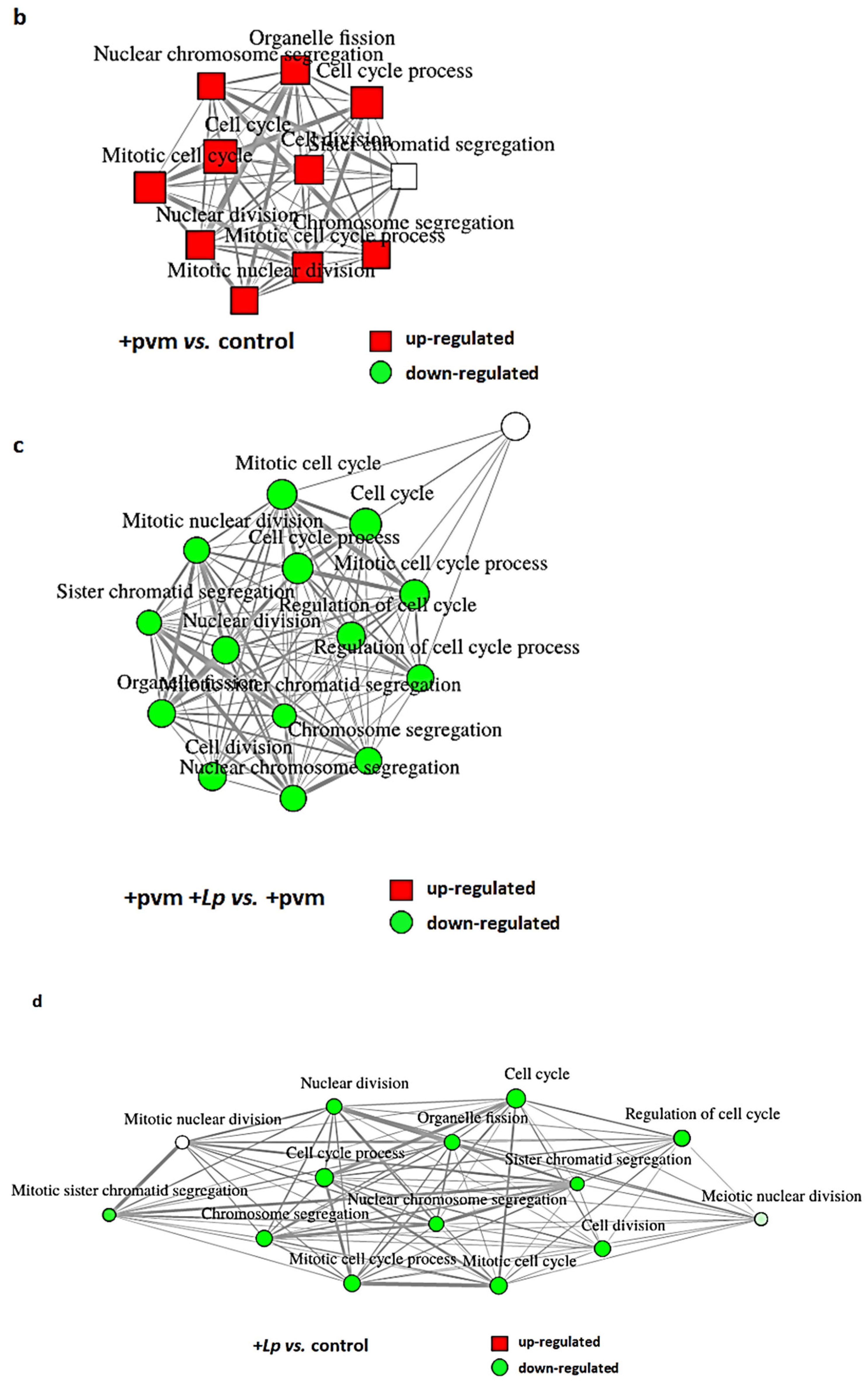

3.3. Differential Expression of Proinflammatory Genes

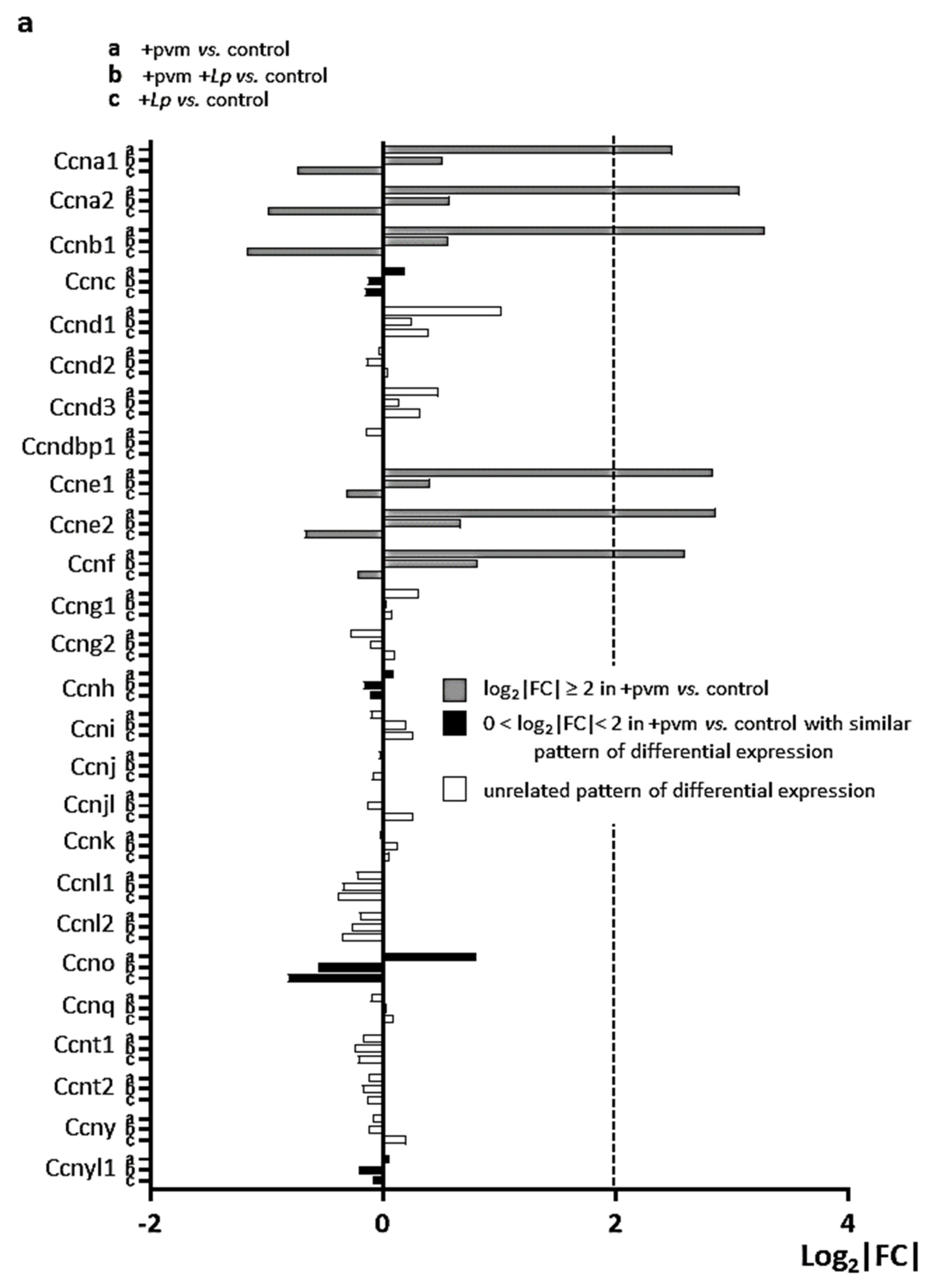

3.4. Differential Expression of Genes Associated with Mitosis and Cell Cycle Regulation

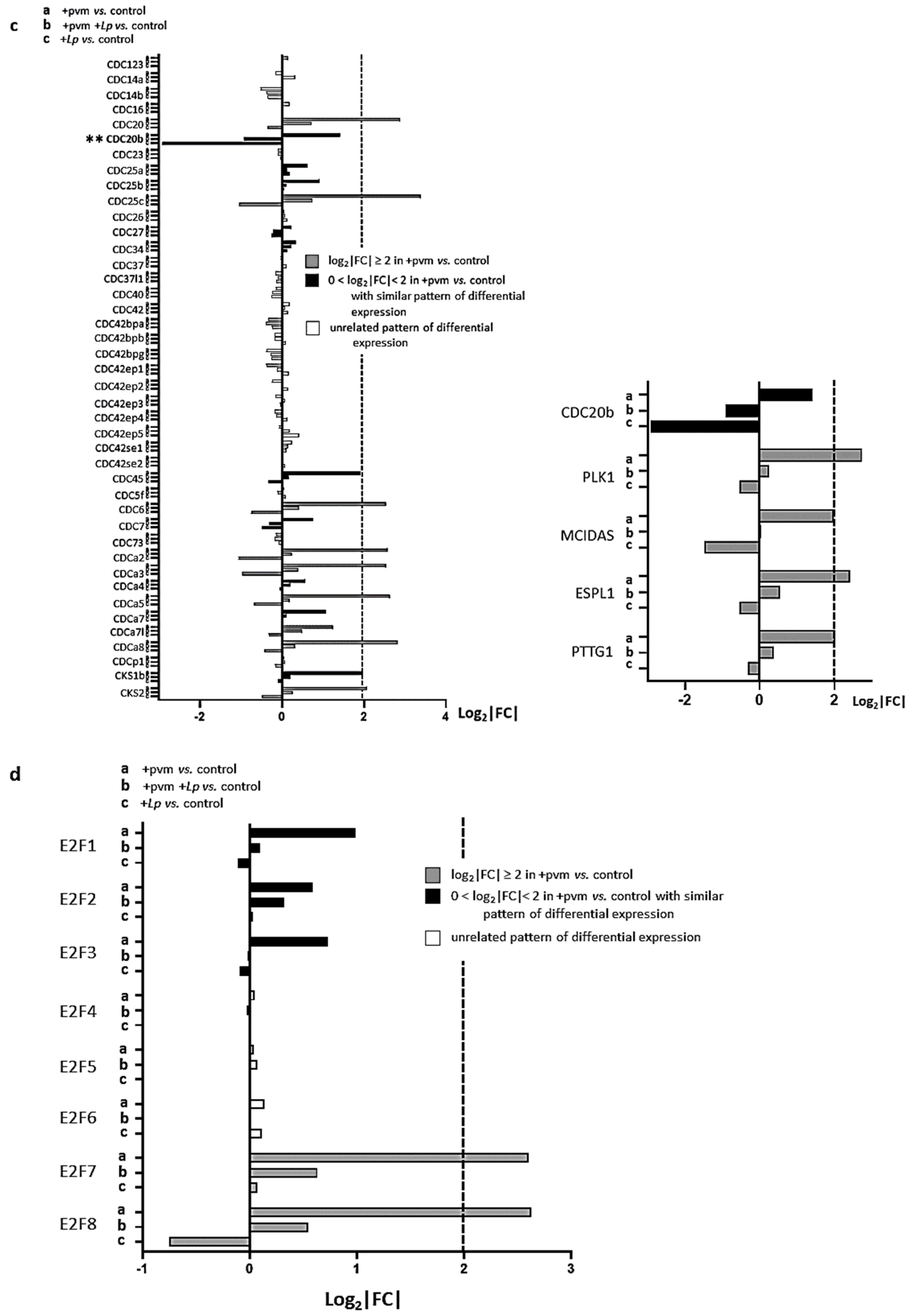

3.5. Differential Expression of Genes Encoding Cyclins (CCNs), Cyclin-Dependent Kinases (CDKs), Cell-Division Cycle Genes (CDCs), and E2F Transcription Factors

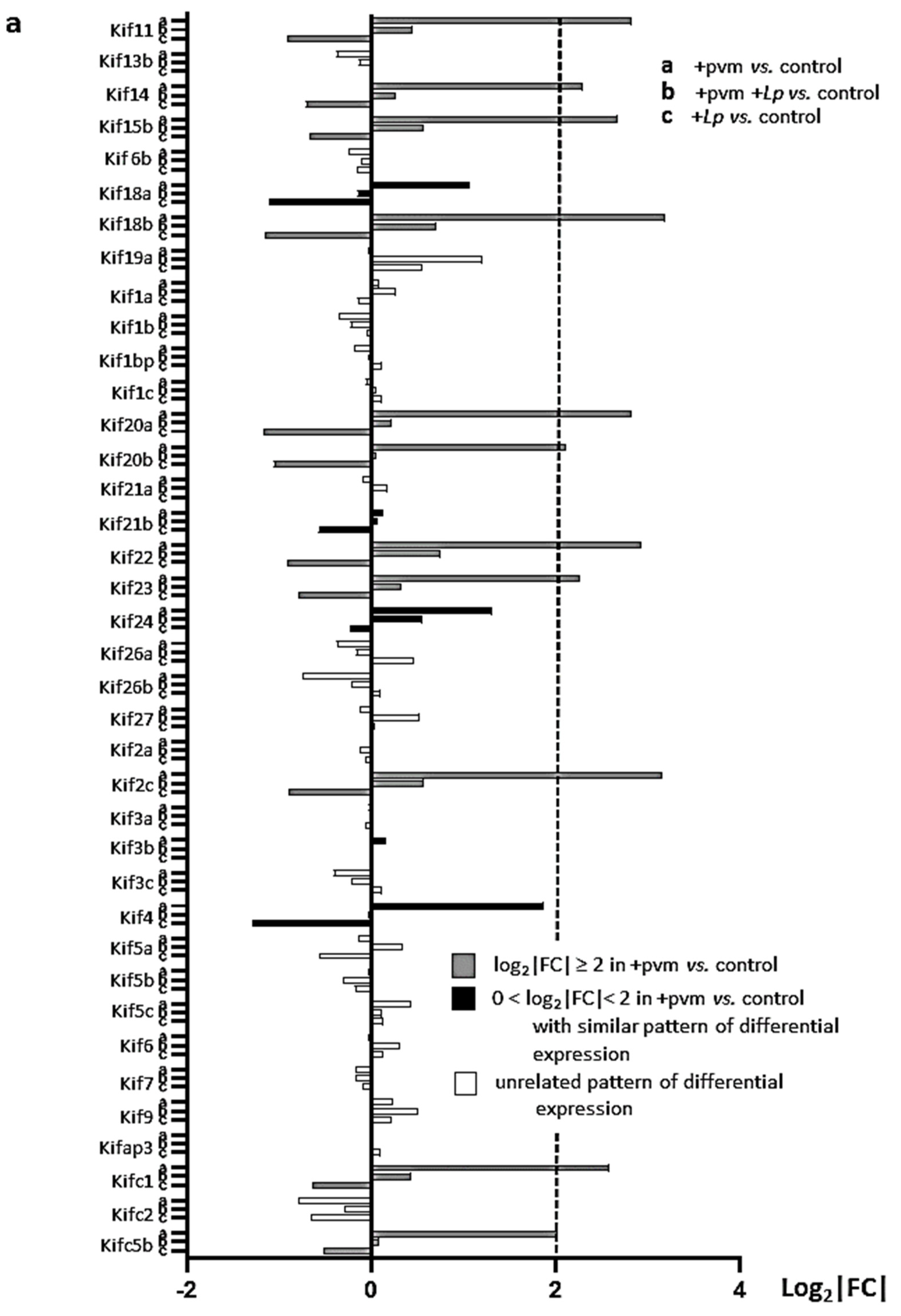

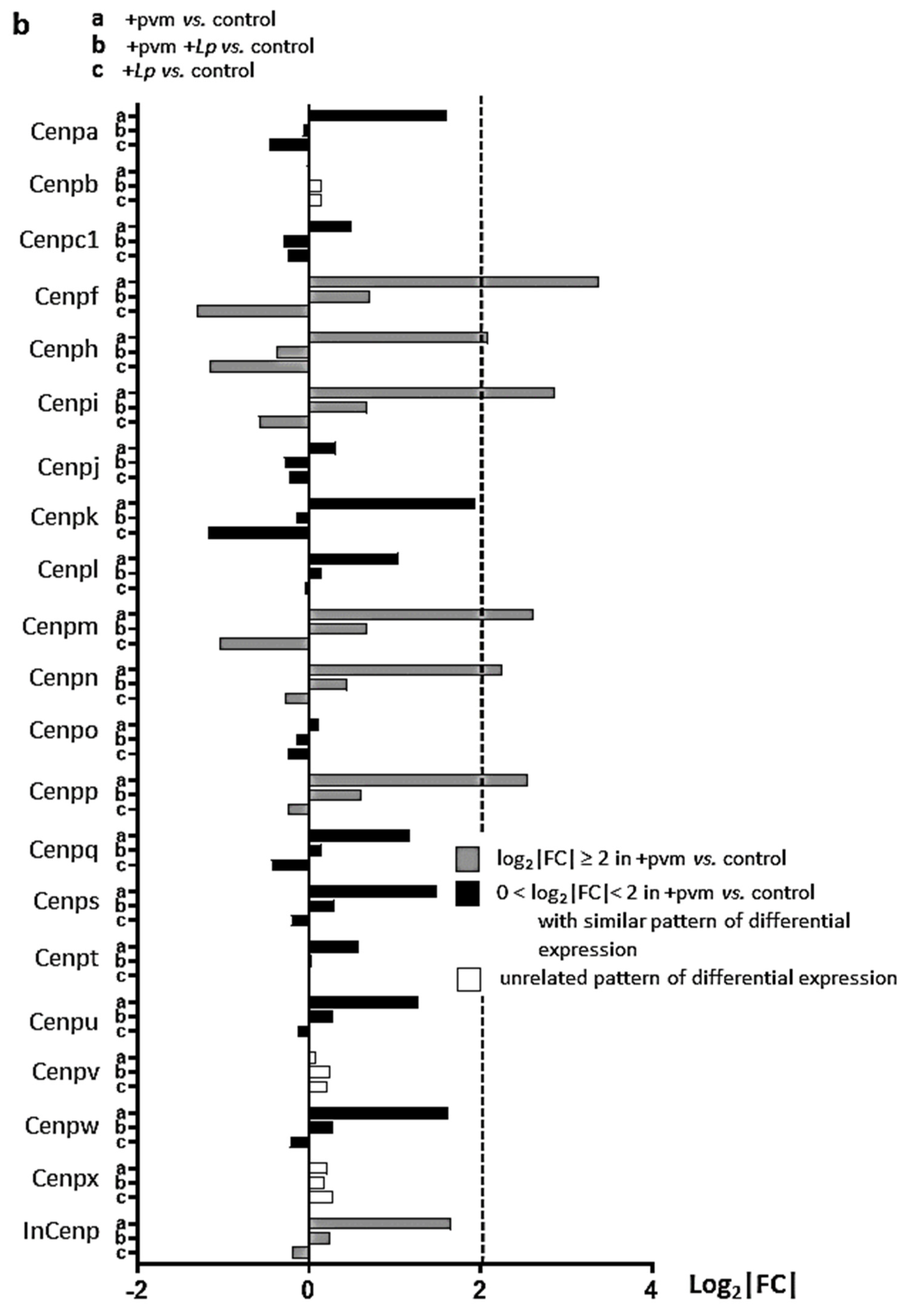

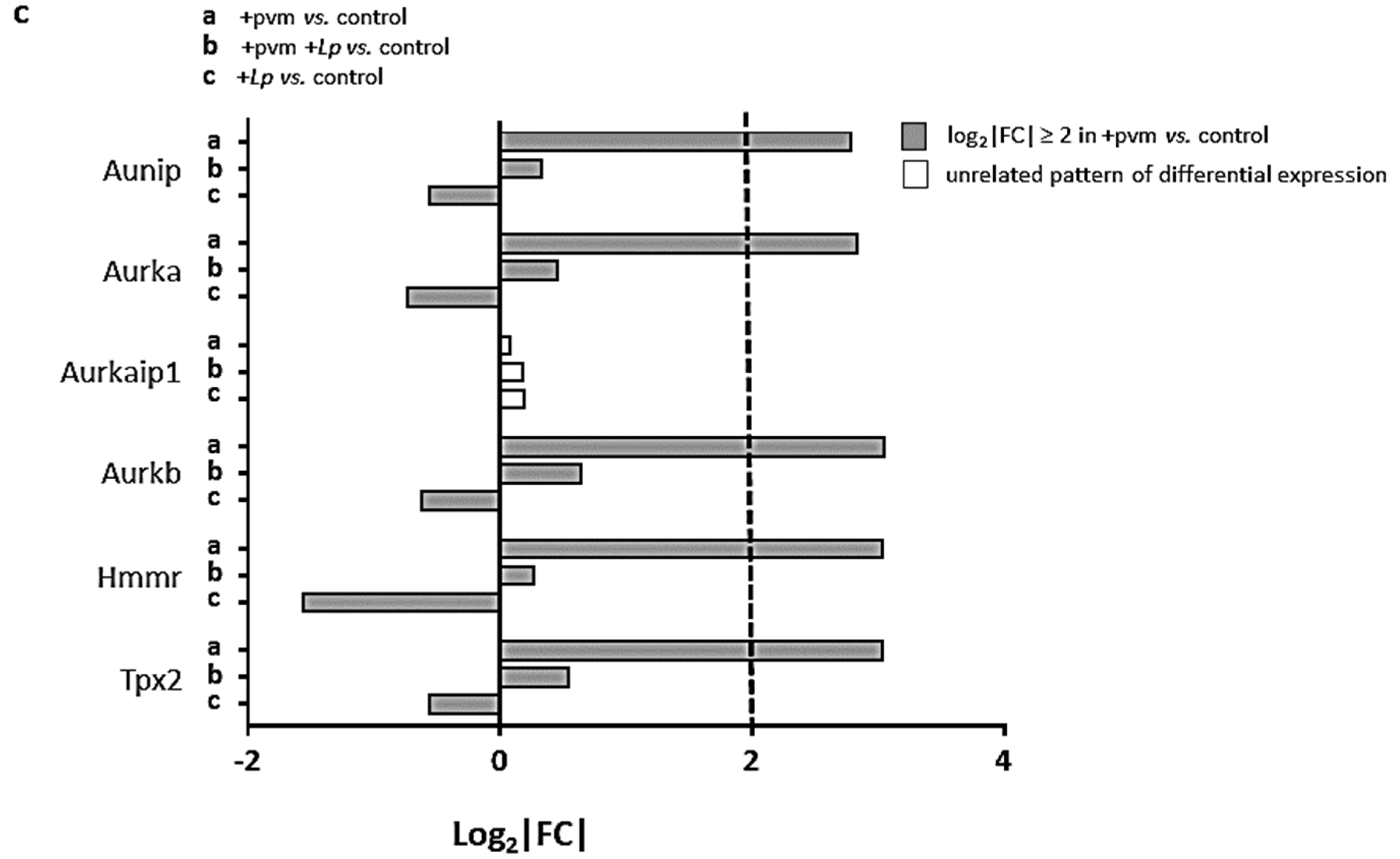

3.6. Differential Expression of Genes Encoding Kinesins (KIFs), Centromere Proteins (CENPs), and Aurora Kinases

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Phillips, S.; Williams, M.A. Confronting our next national health disaster–long-haul COVID. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 577–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quinn, L.A.; Shields, M.D.; Sinha, I.; Groves, H.E. Respiratory syncytial virus prophylaxis for prevention of recurrent childhood wheeze and asthma: A systematic review. Syst. Rev. 2020, 9, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Driscoll, A.J.; Arshad, S.H.; Bont, L.; Brunwasser, S.M.; Cherian, T.; Englund, J.A.; Fell, D.B.; Hammitt, L.L.; Hartert, T.V.; Innis, B.L.; et al. Does respiratory syncytial virus lower respiratory illness in early life cause recurrent wheeze of early childhood and asthma? Critical review of the evidence and guidance for future studies from a World Health Organization-sponsored meeting. Vaccine 2020, 38, 2435–2448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dyer, K.D.; Garcia-Crespo, K.E.; Glineur, S.; Domachowske, J.B.; Rosenberg, H.F. The pneumonia virus of mice (PVM) model of acute respiratory infection. Viruses 2012, 4, 3494–3510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenberg, H.F.; Bonville, C.A.; Easton, A.J.; Domachowske, J.B. The pneumonia virus of mice infection model for severe respiratory syncytial virus infection: Identifying novel targets for therapeutic intervention. Pharmacol. Ther. 2005, 105, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bem, R.A.; Domachowske, J.B.; Rosenberg, H.F. Animal models of human respiratory syncytial virus disease. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2011, 301, L148–L156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, G. Animal models of respiratory syncytial virus infection. Vaccine 2017, 35, 469–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabryszewski, S.J.; Bachar, O.; Dyer, K.D.; Percopo, C.M.; Killoran, K.E.; Domachowske, J.B.; Rosenberg, H.F. Lactobacillus-mediated priming of the respiratory mucosa protects against lethal pneumovirus infection. J. Immunol. 2011, 186, 1151–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Percopo, C.M.; Rice, T.A.; Brenner, T.A.; Dyer, K.D.; Kanakabandi, K.; Luo, J.L.; Sturdevant, D.E.; Porcella, S.F.; Domachowske, J.B.; Keicher, J.D.; et al. Immunobiotic Lactobacillus administered post-exposure averts the lethal sequelae of respiratory virus infection. Antivir. Res. 2015, 121, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Percopo, C.M.; Ma, M.; Rosenberg, H.F. Administration of immunobiotic Lactobacillus plantarum delays but does not prevent lethal pneumovirus infection in Rag1-/- mice. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2017, 102, 905–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Percopo, C.M.; Ma, M.; Brenner, T.A.; Krumholz, J.O.; Break, T.J.; Laky, K.; Rosenberg, H.F. Critical adverse impact of IL-6 in acute pneumovirus infection. J. Immunol. 2019, 202, 871–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rice, T.A.; Brenner, T.A.; Percopo, C.M.; Ma, M.; Keicher, J.D.; Domachowske, J.B.; Rosenberg, H.F. Signaling via pattern recognition receptors NOD2 and TLR2 contributes to immunomodulatory control of lethal pneumovirus infection. Antivir. Res. 2016, 132, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Limkar, A.R.; Percopo, C.M.; Redes, J.L.; Druey, K.M.; Rosenberg, H.F. Persistent airway hyperresponsiveness following recovery from infection with pneumonia virus of mice. Viruses 2021, 13, 728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Percopo, C.M.; Dyer, K.D.; Karpe, K.A.; Domachowske, J.B.; Rosenberg, H.F. Eosinophils and respiratory virus infection: A dual-standard curve qRT-PCR-based method for determining virus recovery from mouse lung tissue. Methods Mol. Biol. 2014, 1178, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Martin, M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet J. 2011, 17, 10–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobin, A.; Davis, C.A.; Schlesinger, F.; Drenkow, J.; Zaleski, C.; Jha, S.; Batut, P.; Chaisson, M.; Gingeras, T.R. STAR: Ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 2012, 29, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Dewey, C.N. RSEM: Accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BCM Bioinform. 2011, 12, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Law, C.W.; Chen, Y.; Shi, W.; Smyth, G.K. Voom: Precision weights unlock linear model analysis tools for RNA-seq read counts. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, R29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.; Johns, R.A. Resistin family proteins in pulmonary diseases. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2020, 319, L422–L434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holcomb, I.N.; Kabakoff, R.C.; Chan, B.; Baker, T.W.; Gurney, A.; Henzel, W.; Nelson, C.; Lowman, H.B.; Wright, B.D.; Skelton, N.J.; et al. FIZZ1, a novel cysteine-rich secreted protein associated with pulmonary inflammation, defines a new gene family. EMBO J. 2000, 19, 4046–4055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samarasinghe, A.; Lin, Y.; LeMessurier, K.; Woolard, S.; McCullers, J. Resistin-like molecules reduce influenza A virus morbidity in mice (VIR5P.1158). J. Immunol 2015, 194 (Suppl. 1), 148-26. [Google Scholar]

- Reddel, C.J.; Weiss, A.S.; Burgess, J.K. Elastin in asthma. Pulm. Pharmacol. Ther. 2012, 25, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, S.J.; Ward, J.A.; Pickett, H.M.; Baldi, S.; Sousa, A.R.; Sterk, P.J.; Chung, K.F.; Djukanovic, R.; Dahlen, B.; Billing, B.; et al. Airway elastin is increased in severe asthma and relates to proximal wall area: Histological and computed tomography findings from the U-BIOPRED severe asthma study. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2021, 51, 296–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sands, M.F.; Ohtake, P.J.; Mahajan, S.J.; Takyar, S.S.; Aalinkeel, R.; Fang, Y.V.; Blume, J.W.; Mullan, B.A.; Sykes, D.E.; Lachina, S.; et al. Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 modulates allergic lung inflammation in murine asthma. Clin. Immunol. 2009, 130, 186–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabral-Pacheco, G.A.; Garza-Veloz, I.; Castruita-De la Rosa, C.; Ramirez-Acuña, J.M.; Perez-Romero, B.A.; Guerrero-Rodriguez, J.F.; Martinez-Avila, N.; Martinez-Fierro, M.L. The roles of matrix metalloproteinases and their inhibitors in human diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 9739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birukova, A.A.; Xing, J.; Fu, P.; Yakubov, B.; Dubrovske, O.; Fortune, J.A.; Klibanov, A.M.; Birukov, K.G. Atrial natriuretic peptide attenuates LPS-induced lung vascular leak: Role of PAK1. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2010, 299, L652–L663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Rubin, B.K.; Voynow, J.A. Mucins, mucus, and goblet cells. Chest 2018, 154, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonser, L.R.; Erle, D.J. Airway mucus and asthma: The role of MUC5AC and MUC5B. J. Clin. Med. 2017, 6, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bingle, L.; Bingle, C.D. Distribution of human PLUNC/BPI fold-containing (BPIF) proteins. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2011, 39, 1023–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akram, K.; Moyo, N.; Tompkins, M.; Tripp, R.; Bingle, L.; Stewart, J.; Bingle, C. An innate defence role for BPIFA1/SPLUNC1 against influenza-A virus infection. Eur. Respir. J. 2015, 46, OA1781. [Google Scholar]

- Gorski, S.A.; Hufford, M.M.; Braciale, T.J. Recent insights into pulmonary repair following virus-induced inflammation of the respiratory tract. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2012, 2, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucchini, A.C.; Gachanja, N.N.; Rossi, A.G.; Dorward, D.A.; Lucas, C.A. Epithelial cells and inflammation in pulmonary wound repair. Cells 2021, 10, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otto, T.; Sicinski, P. Cell cycle proteins as promising targets in cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2017, 17, 93–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harashima, H.; Dissmeyer, N.; Schnittger, A. Cell cycle control across the eukaryotic kingdom. Trends Cell Biol. 2013, 23, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertoli, C.; Skotheim, J.M.; de Bruin, R.A.M. Control of cell cycle transcription during G1 and S phases. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2013, 14, 518–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.; Kaldis, P. Cdks, cyclins and CKIs: Roles beyond cell cycle regulation. Development 2013, 140, 3079–3093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Alonso, D.; Malumbres, M. Mammalian cell cycle cyclins. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 107, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Müller, C.; Huynh, V.; Fung, Y.K.; Yee, A.S.; Koeffler, H.P. Functions of cyclin A’ in the cell cycle and it interactions with transcription factor E2F-1 and the Rb family of proteins. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999, 19, 2400–2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, P.; Agrawal, S.; Diederichs, S.; Bäumer, N.; Becker, A.; Cauvet, T.; Kowski, S.; Beger, C.; Welte, K.; Berdel, W.E.; et al. Cyclin A1, the alternative A-type cyclin, contributes to G1/S cell cycle progression in somatic cells. Oncogene 2005, 24, 2739–2744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, B.; Wang, S.; Jiang, N.; Li, J.J. Cyclin B1/CDK1-regulated mitochondrial bioenergetics in cell cycle progression and tumor resistance. Cancer Lett. 2019, 443, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, C.; Richman, R.; Elledg, S.J. Human cyclin F. EMBO J. 1994, 13, 6087–6098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Angiolella, V.; Esencay, M.; Pagano, M. A cyclin without cyclin-dependent kinases: Cyclin F controls genome stability through ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis. Trends Cell Biol. 2013, 23, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malumbres, M. Cyclin-dependent kinases. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malumbres, M.; Barbacid, M. Cell cycle, CDKs and cancer: A changing paradigm. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2009, 9, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asghar, U.; Witkiewicz, A.K.; Turner, N.C.; Knudsen, E.S. The history and future of targeting cyclin-dependent kinases in cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2015, 14, 130–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, A.D.; Morawski, P.A. New roles for cyclin-dependent kinases in T cell biology: Linking cell division and differentiation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2014, 14, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arellano, M.; Moreno, S. Regulation of CDK/cyclin complexes during the cell cycle. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 1997, 29, 559–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamaria, D.; Barrière, C.; Cerqueira, A.; Hunt, S.; Tardy, C.; Newton, K.; Cáceres, J.F.; Dubus, P.; Malumbres, M.; Barbacid, M. Cdk1 is sufficient to drive the mammalian cell cycle. Nature 2007, 448, 811–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurse, P. Fission yeast cell cycle mutants and the logic of eukaryotic cell cycle control. Mol. Biol. Cell 2020, 31, 2871–2873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biggins, S.; Hartwell, L.; Toczyski, D. Fifty years of cycling. Mol. Biol. Cell 2020, 31, 2868–2870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revinski, D.R.; Zaragosi, L.-E.; Boutin, C.; Ruiz-Garcia, S.; Deprez, M.; Thomé, V.; Rosnet, O.; Gay, A.-S.; Mercey, O.; Paquet, A.; et al. CDC20B is required for deuterosome-medicated centriole production in multiciliated cells. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsou, M.-F.B.; Wang, W.-J.; George, K.A.; Uryu, K.; Stearns, T.; Jallepalli, P.V. Polo kinase and separase regulate the mitotic licensing of centriole duplication in human cells. Dev. Cell 2009, 17, 344–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Mateos, M.A.; Espina, Á.G.; Torres, B.; Gámez del Estral, M.M.; Romero-Franco, A.; Rios, R.M.; Pintor-Toro, J.A. PTTG1/securin modulates microtubue nucleation and cell migration. Mol. Cell Biol. 2011, 22, 4302–4311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flodby, P.; Li, C.; Liu, Y.; Wang, H.; Rieger, M.E.; Minoo, P.; Crandall, E.D.; Ann, D.K.; Borok, Z.; Zhou, B. Cell-specific expression of aquaporin-5 (Aqp5) in alveolar epithelium is directed by GATA6/Sp1 via histone acetylation. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 3473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weng, J.S.; Nakamura, T.; Moriizumi, H.; Yao, R.; Takekawa, M. MCRIP1 promotes the expression of lung-surfactant proteins in mice by disrupting CtBP-mediated epigenetic gene silencing. Commun. Biol. 2019, 2, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohinski, R.J.; Di Lauro, R.; Whitsett, J.A. The lung-specific surfactant protein B gene promoter is a target for thyroid transcription factor 1 and hepatocyte nuclear factor 3, indicating common factors for organ-specific gene expression along the foregut axis. Mol. Cell Biol. 1994, 14, 5671–5681. [Google Scholar]

- Rawlins, E.L.; Perl, A.K. The a “MAZE” ing world of lung-specific transgenic mice. Cell Mol. Biol. 2012, 46, 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kent, L.N.; Leone, G. The broken cycle: E2F dysfunction in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2019, 19, 326–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trimarchi, J.M.; Lees, J.A. Sibling rivalry in the E2F family. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2002, 3, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Shats, I.; Angus, S.P.; Gatza, M.L.; Nevins, J.R. Interactions of E2F7 transcription factor with E2F1 and C-terminal-binding protein (CtBP) provides a mechanism for E2F7-dependent transcriptional repression. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 24581–24589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westendorp, B.; Mokry, M.; Groot Koerkamp, M.J.A.; Holstege, F.C.P.; Cuppen, E.; de Bruin, A. E2F7 represses a network of oscillating cell cycle genes to control S-phase progression. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, 3511–3523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vicente, J.J.; Wordeman, L. Mitosis, microtubule dynamics and the evolution of kinesins. Exp. Cell Res. 2015, 334, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, A.; Wordeman, L. The mechanism, function and regulation of depolymerizing kinesins during mitosis. Trends Cell Biol. 2004, 14, 537–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirokawa, N.; Noda, Y.; Tanaka, Y.; Niwa, S. Kinesin superfamily motor proteins and intracellular transport. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009, 10, 682–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, B.J.; Wadsworth, P. Kinesin-5: Regulation and function in mitosis. Trends Cell Biol. 2019, 29, 66–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, H.; Popov, M.; Goldstein-Levitin, A.; Gheber, L. Mechanisms by which kinesin-5 motors perform their multiple intracellular functions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferenz, N.P.; Gable, A.; Wadsworth, P. Mitotic functions of kinesin-5. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2010, 21, 255–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ems-McClung, S.C.; Walczak, C.E. Kinesin-13s in mitosis: Key players in the spatial and temporal organization of spindle microtubules. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2010, 21, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, F.; Whitby, M.C. Emerging roles for centromere-associated proteins in DNA repair and genetic recombination. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2013, 41, 1726–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willems, E.; Dedobbeleer, M.; Digregorio, M.; Lombard, A.; Lumapat, P.N.; Rogister, B. The functional diversity of Aurora kinases: A comprehensive review. Cell Div. 2018, 13, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosas-Salazar, C.; Shilts, M.H.; Tovchigrechko, A.; Schobel, S.; Chappell, J.D.; Larkin, E.K.; Gebretsadik, T.; Halpin, R.A.; Nelson, K.E.; Moore, M.L.; et al. Nasopharyngeal Lactobacillus is associated with a reduced risk of childhood wheezing illnesses following acute respiratory syncytial virus infection in infancy. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2018, 142, 1447–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hough, K.P.; Curtiss, M.L.; Blain, T.J.; Liu, R.-M.; Trevor, J.; Deshane, J.S.; Thannickal, V.J. Airway remodeling in asthma. Front Med. 2020, 7, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, M.; Rice, T.A.; Percopo, C.M.; Rosenberg, H.F. Silkworm plasma larvae (SLP) assay for detection of bacteria: False positives secondary to inflammation in vivo. J. Microbiol. Methods. 2017, 132, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, M.; Teixeira, A.L.; Coelho, A.; Araújo, A.; Medeiros, R. The role of inflammation in lung cancer. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2014, 816, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hirano, T. IL-6 in inflammation, autoimmunity and cancer. Int. Immunol. 2021, 33, 127–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houghton, A.M. Mechanistic links between COPD and lung cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2013, 13, 233–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| #Up-Regulated | #Down-Regulated | |

|---|---|---|

| (log2|FC| ≥ 2.00) | (log2|FC| ≤ −2.00) | |

| +pvm vs. control | 289 | 19 |

| +pvm vs. +pvm +Lp | 162 | 44 |

| +pvm +Lp vs. control | 86 | 4 |

| +Lp vs. control | 68 | 8 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Limkar, A.R.; Lack, J.B.; Sek, A.C.; Percopo, C.M.; Druey, K.M.; Rosenberg, H.F. Differential Expression of Mitosis and Cell Cycle Regulatory Genes during Recovery from an Acute Respiratory Virus Infection. Pathogens 2021, 10, 1625. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens10121625

Limkar AR, Lack JB, Sek AC, Percopo CM, Druey KM, Rosenberg HF. Differential Expression of Mitosis and Cell Cycle Regulatory Genes during Recovery from an Acute Respiratory Virus Infection. Pathogens. 2021; 10(12):1625. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens10121625

Chicago/Turabian StyleLimkar, Ajinkya R., Justin B. Lack, Albert C. Sek, Caroline M. Percopo, Kirk M. Druey, and Helene F. Rosenberg. 2021. "Differential Expression of Mitosis and Cell Cycle Regulatory Genes during Recovery from an Acute Respiratory Virus Infection" Pathogens 10, no. 12: 1625. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens10121625

APA StyleLimkar, A. R., Lack, J. B., Sek, A. C., Percopo, C. M., Druey, K. M., & Rosenberg, H. F. (2021). Differential Expression of Mitosis and Cell Cycle Regulatory Genes during Recovery from an Acute Respiratory Virus Infection. Pathogens, 10(12), 1625. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens10121625