The 4-Year Experience with Implementation and Routine Use of Pathogen Reduction in a Brazilian Hospital

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. PR Implementation Feasibility through PC Production Method Adjustments

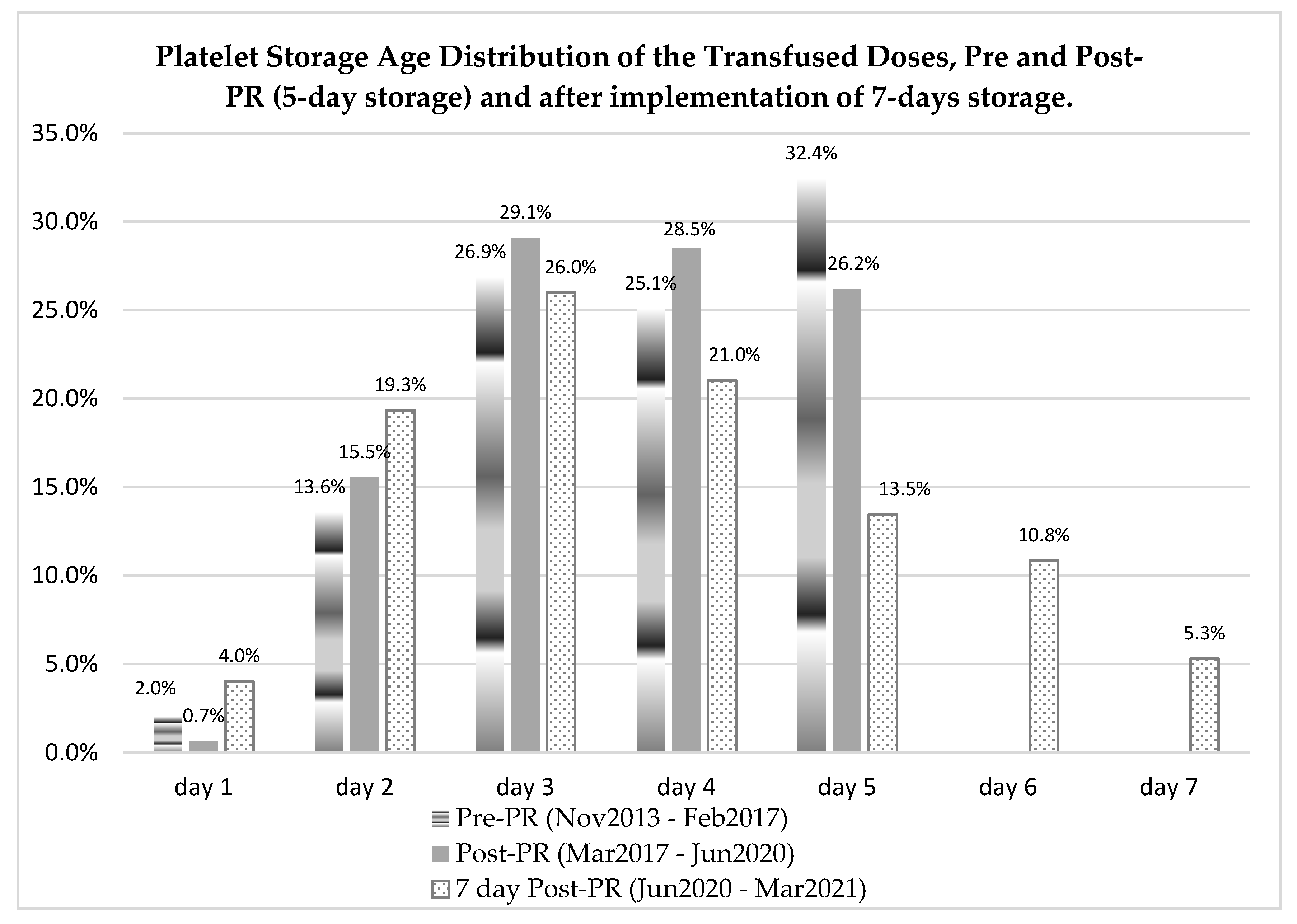

2.2. Meeting Transfusion Demand through Optimized Inventory Management

2.3. Blood Utilization Remained the Same after PR Implementation

2.4. Platelet Transfusion Adverse Events (AEs) Decreased after PR Implementation

2.5. Fresh Frozen Plasma Transfusions

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Apheresis Preparation

4.2. Single Dose Pooling to Double Dose (New Product)

4.3. Preparation of Single and Double Dose RDP Concentrates for PR Treatment

4.4. Preparation of Fresh Frozen Plasma

4.5. Pathogen Reduction Treatment

4.5.1. For Platelets

4.5.2. For Plasma

4.6. QC Tests Performed for Blood Components

4.7. Statistical Analysis

4.8. Ethical Declaration

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Devine, D.V.; Schubert, P. Pathogen Inactivation Technologies: The Advent of Pathogen-Reduced Blood Components to Reduce Blood Safety Risk. Hematol. Clin. N. Am. 2016, 30, 609–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salunkhe, V.; Van der Meer, P.; de Korte, D.; Seghatchian, J.; Gutiérrez, L. Development of blood transfusion product pathogen reduction treatments: A review of methods, current applications and demands. Transfus. Apher. Sci. 2015, 52, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, R.; Razatos, A. Bacterial mitigation strategies: Impact of pathogen reduction and large-volume sampling on platelet productivity. Ann. Blood 2021, 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, R.J.; Carter, K.L.; Corash, L. Amotosalen and ultraviolet-A treated platelets and plasma are safe and efficacious in active hemorrhage. Transfusion 2016, 56, 2649–2650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, B.S.; Schmidt, R.L.; Fisher, M.A.; White, S.K.; Blaylock, R.C.; Metcalf, R.A. The comparative safety of bacterial risk control strategies for platelet components: A simulation study. Transfusion 2020, 60, 1723–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, W.G.; Foley, M.; Doherty, C.; Tierney, G.; Kinsella, A.; Salami, A.; Cadden, E.; Coakley, P. Screening platelet concentrates for bacterial contamination: Low numbers of bacteria and slow growth in contaminated units mandate an alternative approach to product safety. Vox Sang. 2008, 95, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloch, E.M. Residual risk of bacterial contamination: What are the options? Transfusion 2017, 57, 2289–2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FDA. Bacterial Risk Control Strategies for Blood Collection Establishments and Transfusion Services to Enhance the Safety and Availability of Platelets for Transfusion. In Guidance for Industry. Available online: https://wwwfdagov/vaccines-blood-biologics/guidance-compliance-regulatory-informationbiologics/biologics-guidances (accessed on 30 December 2020).

- Hong, H.; Xiao, W.; Lazarus, H.M.; Good, C.E.; Maitta, R.W.; Jacobs, M.R. Detection of septic transfusion reactions to platelet transfusions by active and passive surveillance. Blood 2016, 127, 496–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, D.; Andrade, E.; Godoy, D.T.; Fontana-Maurell, M.; Costa, E.; Ribeiro, M.; Ferreira, A.G.; Brindeiro, R.; Tanuri, A.; Alvarez, P. The Brazilian experience of nucleic acid testing to detect human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis C virus, and hepatitis B virus infections in blood donors. Transfusion 2018, 58, 862–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musso, D.; Bossin, H.; Mallet, H.P.; Besnard, M.; Broult, J.; Baudouin, L.; Levi, J.E.; Sabino, E.C.; Ghawche, F.; Lanteri, M.C.; et al. Zika virus in French Polynesia 2013–14: Anatomy of a completed outbreak. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, e172–e182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Cam, S.; Houze, S.; Barlet, V.; Maugard, C.; Narboux, C.; Morel, P.; Garraud, O.; Tiberghien, P.; Gallian, P. Preventing transfusion-transmitted malaria in France. Vox Sang. 2021, 116, 943–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marks, P.W.; Epstein, J.; Borio, L.L. Maintaining a Safe Blood Supply in an Era of Emerging Pathogens. J. Infect. Dis. 2016, 213, 1676–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Stone, M.; Lanteri, M.C.; Bakkour, S.; Deng, X.; Galel, S.A.; Linnen, J.M.; Muñoz-Jordán, J.L.; Lanciotti, R.S.; Rios, M.; Gallian, P.; et al. Relative analytical sensitivity of donor nucleic acid amplification technology screening and diagnostic real-time polymerase chain reaction assays for detection of Zika virus RNA. Transfusion 2017, 57, 734–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malange, T.D.; Atia, T. Blood shortage in COVID-19: A crisis within a crisis. S. Afr. Med. J. 2021, 111, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azhar, E.I.; Hindawi, S.I.; El-Kafrawy, S.A.; Hassan, A.M.; Tolah, A.M.; Alandijany, T.A.; Bajrai, L.H.; Damanhouri, G.A. Amotosalen and ultraviolet A light treatment efficiently inactivates severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in human plasma. Vox Sang. 2021, 116, 673–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, P.; Verdun, N. Toward universal pathogen reduction of the blood supply (Conference Report, p. 3002). Transfusion 2019, 59, 3026–3028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busch, M.P.; Bloch, E.M.; Kleinman, S.H. Prevention of transfusion-transmitted infections. Blood 2019, 133, 1854–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atreya, C.; Glynn, S.; Busch, M.; Kleinman, S.; Snyder, E.; Rutter, S.; AuBuchon, J.; Flegel, W.; Reeve, D.; Devine, D.; et al. Proceedings of the Food and Drug Administration public workshop on pathogen reduction technologies for blood safety 2018 (Commentary, p. 3026). Transfusion 2019, 59, 3002–3025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutter, S.; Snyder, E.L. How do we integrate pathogen reduced platelets into our hospital blood bank inventory? Transfusion 2019, 59, 1628–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanteri, M.C.; Santa-Maria, F.; Laughhunn, A.; Girard, Y.A.; Picard-Maureau, M.; Payrat, J.; Irsch, J.; Stassinopoulos, A.; Bringmann, P. Inactivation of a broad spectrum of viruses and parasites by photochemical treatment of plasma and platelets using amotosalen and ultraviolet A light. Transfusion 2020, 60, 1319–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Minno, G.; Perno, C.F.; Tiede, A.; Navarro, D.; Canaro, M.; Güertler, L.; Ironside, J. Current concepts in the prevention of pathogen transmission via blood/plasma-derived products for bleeding disorders. Blood Rev. 2016, 30, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thiele, T.; Sablewski, A. Profiling alterations in platelets induced by Amotosalen/UVA pathogen reduction and gamma irradiation—A LC-ESI-MS/MS-based proteomics approach. High Speed Blood Transfus. Equip. 2012, 10, s63–s70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julmy, F.; Ammann, R.A.; Fontana, S.; Taleghani, B.M.; Hirt, A.; Leibundgut, K. Transfusion Efficacy of Apheresis Platelet Concentrates Irradiated at the Day of Transfusion Is Significantly Superior Compared to Platelets Irradiated in Advance. Transfus. Med. Hemotherapy 2014, 41, 176–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cid, J. Prevention of transfusion-associated graft-versus-host disease with pathogen-reduced platelets with amotosalen and ultraviolet A light: A review. Vox Sang. 2017, 112, 607–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerus. INTERCEPT Platelets Technical Data Sheet. prd-tds_00121 2019;v11. Available online: https://cerusemea.showpad.com/share/v9o4bZgoIPZShRUtj9XkD/0 (accessed on 10 October 2021).

- Cerus. INTERCEPT Plasma Technical Data Sheet. PRD-TDS_00120 2019;v13. Available online: https://cerusemea.showpad.com/share/v9o4bZgoIPZShRUtj9XkD/0 (accessed on 10 October 2021).

- Garban, F.; Guyard, A.; Labussière, H.; Bulabois, C.-E.; Marchand, T.; Mounier, C.; Caillot, D.; Bay, J.-O.; Coiteux, V.; Schmidt-Tanguy, A.; et al. Comparison of the Hemostatic Efficacy of Pathogen-Reduced Platelets vs Untreated Platelets in Patients With Thrombocytopenia and Malignant Hematologic Diseases: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2018, 4, 468–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Infanti, L.; Holbro, A.; Passweg, J.; Bolliger, D.; Tsakiris, D.A.; Merki, R.; Plattner, A.; Tappe, D.; Irsch, J.; Lin, J.; et al. Clinical impact of amotosalen-ultraviolet A pathogen-inactivated platelets stored for up to 7 days. Transfusion 2019, 59, 3350–3361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitman, J.; Perez, M.; O’Neal, T.; Park, M.-S.; Liu, K. Safety of Amotosalen/UVA (INTERCEPT) Platelet Components in France over 9Years, Including 2 Years As the National Standard of Care. Transfusion 2021, 61, 217A. [Google Scholar]

- Domanović, D.; Ushiro-Lumb, I.; Compernolle, V.; Brusin, S.; Funk, M.; Gallian, P.; Georgsen, J.; Janssen, M.; Jimenez-Marco, T.; Knutson, F.; et al. Pathogen reduction of blood components during outbreaks of infectious diseases in the European Union: An expert opinion from the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control consultation meeting. Blood Transfus. 2019, 17, 433–448. [Google Scholar]

- Castro, G.; Merkel, P.A.; Giclas, H.E.; Gibula, A.; Andersen, G.E.; Corash, L.M.; Lin, J.S.; Green, J.; Knight, V.; Stassinopoulos, A. Amotosalen/UVA treatment inactivates T cells more effectively than the recommended gamma dose for prevention of transfusion-associated graft-versus-host disease. Transfusion 2018, 58, 1506–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinman, S.; Stassinopoulos, A. Transfusion-associated graft-versus-host disease reexamined: Potential for improved prevention using a universally applied intervention. Transfusion 2018, 58, 2545–2563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, J.; Tsoi, W.C.; Lee, C.K.; Leung, R.; Lam, C.C.K.; Koontz, C.; Liu, A.Y.; Huang, N.; Benjamin, R.J.; Vermeij, H.J.; et al. Transfusion of pathogen-reduced platelet components without leukoreduction. Transfusion 2019, 59, 1953–1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prowse, C.V. Component pathogen inactivation: A critical review. Vox Sang. 2012, 104, 183–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mertes, P.M.; Tacquard, C.; Andreu, G.; Kientz, D.; Gross, S.; Malard, L.; Drouet, C.; Carlier, M.; Gachet, C.; Sandid, I.; et al. Hypersensitivity transfusion reactions to platelet concentrate: A retrospective analysis of the French hemovigilance network. Transfusion 2019, 60, 507–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloch, E.M.; Marshall, C.E.; Boyd, J.S.; Shifflett, L.; Tobian, A.A.; Gehrie, E.A.; Ness, P.M. Implementation of secondary bacterial culture testing of platelets to mitigate residual risk of septic transfusion reactions. Transfusion 2018, 58, 1647–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, C.; Allen, J.; Brailsford, S.; Roy, A.; Ball, J.; Moule, R.; Vasconcelos, M.; Morrison, R.; Pitt, T. Bacterial screening of platelet components by National Health Service Blood and Transplant, an effective risk reduction measure. Transfusion 2017, 57, 1122–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, M.R.; Smith, D.; Heaton, W.A.; Zantek, N.; Good, C.E. PGD Study Group Detection of bacterial contamination in prestorage culture-negative apheresis platelets on day of issue with the Pan Genera Detection test. Transfusion 2011, 51, 2573–2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, R.J.; Corash, L.; Norris, P.J. Intercept pathogen-reduced platelets are not associated with higher rates of alloimmunization with (or without) clinical refractoriness in published studies. Transfusion 2020, 60, 881–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, B.S.; White, S.K.; Schmidt, R.L.; Metcalf, R.A. Residual bacterial detection rates after primary culture as determined by secondary culture and rapid testing in platelet components: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Transfusion 2020, 60, 2029–2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, S.K.; Schmidt, R.L.; Walker, B.S.; Metcalf, R.A. Bacterial contamination rate of platelet components by primary culture: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Transfusion 2020, 60, 986–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janetzko, K.; Lin, L.; Eichler, H.; Mayaudon, V.; Flament, J.; Kluter, H. Implementation of the INTERCEPT Blood System for Platelets into routine blood bank manufacturing procedures: Evaluation of apheresis platelets. Vox Sang. 2004, 86, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estcourt, L.J.; Malouf, R.; Hopewell, S.; Trivella, M.; Dorée, C.; Stanworth, S.J.; Murphy, M.F. Pathogen-reduced platelets for the prevention of bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 7, CD009072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, M.; Knutson, F.; Tardivel, R.; Cid, J.; Maymó, R.M.; Löf, H.; Roddie, H.; Pelly, J.; Docherty, A.; Sherman, C.; et al. A multi-centre study of therapeutic efficacy and safety of platelet components treated with amotosalen and ultraviolet A pathogen inactivation stored for 6 or 7 d prior to transfusion. Br. J. Haematol. 2011, 153, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacLennan, S.; Harding, K.; Llewelyn, C.; Choo, L.; Bakrania, L.; Massey, E.; Stanworth, S.; Pendry, K.; Williamson, L.M. A randomized noninferiority crossover trial of corrected count increments and bleeding in thrombocytopenic hematology patients receiving 2- to 5- versus 6- or 7-day-stored platelets. Transfusion 2015, 55, 1856–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubron, C.; Flint, A.W.J.; Ozier, Y.; McQuilten, Z. Platelet storage duration and its clinical and transfusion outcomes: A systematic review. Crit. Care 2018, 22, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebulla, P.; Garban, F.; Meer, P.F.; Heddle, N.M.; McCullough, J. A crosswalk tabular review on methods and outcomes from randomized clinical trials using pathogen reduced platelets. Transfusion 2020, 60, 1267–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCullough, J.; Goldfinger, D.; Gorlin, J.; Riley, W.J.; Sandhu, H.; Stowell, C.; Ward, D.; Clay, M.; Pulkrabek, S.; Chrebtow, V.; et al. Cost implications of implementation of pathogen-inactivated platelets. Transfusion 2015, 55, 2312–2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Product | Study Phase | Volume (mL) | Platelet Concentration (×109/L) | Platelet Dose (×1011) | pH (22 °C) * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single dose platelet apheresis for individual treatment | Pre-PR | 225 ± 8 | 1700 ± 222 | 3.8 ± 0.5 | 7.25 ± 0.13 |

| Target values | 255–420 | - | 2.5–5.0 | - | |

| Post-PR | 264 ± 6 | 1599 ± 122 | 4.2 ± 0.3 | 7.18 ± 0.20 | |

| p | <0.01 | 0.03 | <0.01 | 0.11 | |

| Single dose platelet apheresis for pool treatment | Pre-PR | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Target values | 200–210 | - | 2.5–4.0 | - | |

| Post-PR | 206 ± 5 | 1868 ± 97 | 3.5 ± 0.3 | 7.30 ± 0.20 | |

| Double dose platelet apheresis | Pre-PR | 447 ± 9 | 1744 ± 178 | 7.8 ± 0.8 | 7.26 ± 0.12 |

| Target values | 375–420 | - | 2.5–8.0 | - | |

| Post-PR | 411 ± 5 | 1849 ± 97 | 7.6 ± 0.4 | 7.27 ± 0.30 | |

| p | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.23 | 0.86 | |

| Random donor platelets (RDP) | Pre-PR | 61 ± 2 | 1308 ± 185 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 7.40 ± 0.10 |

| Target values | 40–45 | - | 0.7–0.9 | - | |

| Post-PR | 43 ± 3 | 1764 ± 470 | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 7.30 ± 0.30 | |

| p | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.24 | 0.09 | |

| Plasma | Pre-PR | 240 ± 30 | - | - | - |

| Target values | 150–300 (per unit) | - | - | - | |

| Post-PR | 196 ± 3 | - | - | - | |

| p | <0.01 |

| Pre-PR (November 13–March 17) | Post-PR (March 17–July 20) | INTERCEPT Device | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LV | DS | |||||

| Total platelet transfusions (doses) | 7777 | 100% | 6921 | 100% | 1599 (23.1%) | 5307 (76.9%) |

| Apheresis doses | 6695 | 86.1% | 6016 * | 86.9% | 1188 (19.8%) | 4822 (80.2%) |

| -Single apheresis (single dose) | 4050 | 60.5% | 1188 | 19.8% | 1188 (37.1%) | NA |

| -Single apheresis (for pool of 2) | NA | NA | 2013 | 33.5% | NA | 2013 (62.9%) |

| -Double apheresis | 2645 | 39.5% | 2809 & | 46.7% | NA | 2809 (100%) |

| RDP doses | 1082 | 13.9% | 905 # | 13.1% | 411 (45.9%) | 485 (54.1%) |

| Pre-PR | Post-PR | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| November 2013–February 2017 | March 2017–July 2020 | p | |||

| Component | Production | Discarded (%) | Production | Discarded (%) | |

| Apheresis | 6818 | 400 (5.9) | 6161 | 196 (3.2) | <0.001 |

| RDP | 8858 | 2013 (22.7) | 5485 | 166 (3.0) | <0.001 |

| Stored for Up to Five Days (June 19–March 20) | Stored for Up to Seven Days (June 20–March 21) | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Component | PR-Treated | Discarded (%) | PR-Treated | Discarded (%) | |

| Apheresis | 1270 | 59 (4.7) | 1526 | 18 (1.2) | <0.001 |

| RDP | 858 | 22 (2.6) | 1375 | 6 (0.4) | <0.001 |

| Clinical Department | Pre-PR November 2013–February 2017 | Post-PR March 2017–July 2020 | P (Doses) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Doses (%) | Patients (%) | Dose per Patient (Mean ± sd) | Doses (%) | Patients (%) | Dose per Patient (Mean ± sd) | ||

| Oncology | 4109 (52.8) | 366 (35.5) | 13.2 ± 24.8 | 3,369 (48.7) | 282 (30.6) | 14.1 ± 32.8 | 0.45 |

| Critical | 2774 (35.7) | 313 (30.4) | 5.0 ± 7.6 | 2,750 (39.7) | 330 (35.9) | 4.6 ± 7.6 | 0.46 |

| Surgical | 416 (5.4) | 226 (21.9) | 3.0 ± 6.0 | 394 (5.7) | 206 (22.4) | 4.0 ± 14.0 | 0.75 |

| Clinical | 478 (6.1) | 126 (12.2) | 5.4 ± 9.9 | 408 (5.9) | 102 (11.1) | 6.2 ± 12.0 | 0.72 |

| Total | 7777 (100%) | 1031 (100%) | 7.5 ± 16.5 | 6,921 (100%) | 920 (100%) | 7.5 ± 20.7 | 0.90 |

| Pre-PR November 2013–February 2017 | Post-PR March 2017–July 2020 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Platelet count pre-transfusion (platelets/µL) | Doses (n) | Patients (n) | Doses/Patient mean + sd (Min-Max) | Doses (n) | Patients (n) | Doses/Patient mean+ sd (Min-Max) |

| <20,000 | 3942 | 513 | 7.68 + 13.0 (1–178) | 3172 | 412 | 7.70 + 13.4 (1–158) |

| >20,000 | 2778 | 613 | 4.53 + 9.2 (1–154) | 2753 | 552 | 4.99 + 16.9 (1–305) |

| Total analyzed * | 6720 | 5925 | ||||

| Pre-PR November 2013–February 2017 | Post-PR March 2017–July 2020 | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mild allergic | 127 | 1.63% | 76 | 1.11% | 0.0065 |

| FNHTR (*) | 35 | 0.45% | 18 | 0.26% | NS |

| HTR | 2 | 0.03% | 0 | NS | |

| Fluid Overload | 2 | 0.03% | 0 | NS | |

| TRALI | 0 | 1 | 0.01% | NS | |

| Non-concluded | 1 | 0.01% | 2 | 0.03% | NS |

| Total | 167 | 2.15% | 97 | 1.41% | 0.0008 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fachini, R.M.; Fontão-Wendel, R.; Achkar, R.; Scuracchio, P.; Brito, M.; Amaral, M.; Wendel, S. The 4-Year Experience with Implementation and Routine Use of Pathogen Reduction in a Brazilian Hospital. Pathogens 2021, 10, 1499. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens10111499

Fachini RM, Fontão-Wendel R, Achkar R, Scuracchio P, Brito M, Amaral M, Wendel S. The 4-Year Experience with Implementation and Routine Use of Pathogen Reduction in a Brazilian Hospital. Pathogens. 2021; 10(11):1499. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens10111499

Chicago/Turabian StyleFachini, Roberta Maria, Rita Fontão-Wendel, Ruth Achkar, Patrícia Scuracchio, Mayra Brito, Marcelo Amaral, and Silvano Wendel. 2021. "The 4-Year Experience with Implementation and Routine Use of Pathogen Reduction in a Brazilian Hospital" Pathogens 10, no. 11: 1499. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens10111499

APA StyleFachini, R. M., Fontão-Wendel, R., Achkar, R., Scuracchio, P., Brito, M., Amaral, M., & Wendel, S. (2021). The 4-Year Experience with Implementation and Routine Use of Pathogen Reduction in a Brazilian Hospital. Pathogens, 10(11), 1499. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens10111499