1. Introduction

During the Arab Uprisings of 2011, viewers of channels such as Al Jazeera and participants in social media platforms like Facebook and Twitter watched as revolutionary movements spread from Tunisia to Egypt, Libya, Syria, Bahrain, Yemen, and elsewhere. Citizen journalists, wielding their camera phones, fed on-the-ground records to both the mainstream and the alternative media. Meanwhile, intellectuals and journalists, many of them from the countries concerned and others among them outsiders, offered background knowledge and analysis of events on television and online.

Small wonder, then, that in his recent novel about the Egyptian Revolution,

The City Always Wins, Omar Robert Hamilton depicts an internet-enabled phone as being equally essential to Cairo’s protestors as water. This is illustrated in the novel’s very first chapter. The female protagonist, Mariam, is helping with the dead and injured in hospital after a thwarted march on the state broadcaster at Maspero. Amid the bloodshed, rage, and panic she orders herself: ‘Go find a charger, some water’ (

Hamilton 2017a, p. 8).

1 Later, working through a packing list of supplies for a protest in Tahrir Square, her smartphone charger is the first item on this inventory—ahead of water, her notebook, medication, and toiletries (39). In the Arab Spring, phones therefore became a central ‘weapon of the weak’—to adapt James Scott’s (

Scott 1985) formulation. Hamilton’s central characters Mariam and Khalil make use of technology in unexpected ways which appear to protect them and their activist friends, or at least hold hostile larger forces at bay. Hamilton emphasizes that the dissemination of propaganda and fake news has long been the

modus operandi of Egypt’s rulers. However, when even the powerless have powerful technologies in their hands, things start to change. I want to explore the novel’s representations of (social) media and the impact these have on everyday lives, modes of protest, and literary form. In the Egyptian Revolution, the social media to which the activists’ phones provided access could be used to organize protests, regulate community behaviour, and shine a spotlight on regime atrocities. These new media functioned as a digital public square, encouraging Cairenes to protest in the real public square of Tahrir.

The alternative media possess mass engagement and a global reach, and, at least at first, threaten power. However, over the course of his novel the Egyptian-heritage writer traces the crushing of the ‘social media revolution’ and the rise of a disillusionment and despair among the revolutionaries. This downward trajectory is typified in the appellative journey from Hamilton’s own non-profit media collective, Mosireen—according to his mother the novelist Ahdaf Soueif, this means ‘determined’ while also playing on the Arabic word for Egyptians,

misriyeen (

Soueif 2012, p. 201)—to the novel’s similar group, portentously known as the Chaos Collective. This name signals the fictional organization’s spontaneous and leaderless nature. However, later the religious right uses it to smear the group’s reputation: ‘

Chaos. What kind of an organization is called Chaos? […] Names matter. So they call themselves Chaos and they’ve been laughing at us’ (

Hamilton 2017a, p. 268; emphasis in original). If it is true that ‘[y]ou need chaos to win an insurgency’, the insurgency turns into a war—for which ‘discipline’ (152) might have proven more effective than Chaos’s preferred approach of anarchic egalitarianism.

The novel’s increasingly gloomy narrative arc is also reflected in its reverse chronological structure of three parts entitled ‘Tomorrow’, ‘Today’, and ‘Yesterday’. The novel opens with ‘Tomorrow’, which is set between 9 October 2011 and 1 February 2012. This period comprises five of the 18 months when Egypt was ruled by the interim government of the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF). At that time, just eight months to a year after President Mubarak’s forced resignation, a great hopefulness still pervaded Egypt, as activists tried to harness the nation’s post-revolutionary momentum. As noted by one prominent activist Alaa Abd el-Fattah—whose work will be discussed later—in the SCAF era, there was a ‘sheer sense of hope and possibility: despite setbacks our dreams continued to soar’ (

El Fattah 2016, n.p.). Chaos regularly release videos, photographs, writing, and podcasts about such ‘setbacks’, detailing the authorities’ brutality, the movement’s bravery, and the suffering of martyrs and their relatives. In the immediate post-revolutionary climate, these outputs go viral without fail. Similarly, ‘[a]t its height, [Mosireen’s] YouTube channel was the most watched non-profit channel in the world’ (

Moore 2018, p. 202). Hamilton’s novel can be situated as an extension of Mosireen’s three-year dissident activities. If there initially seems a generic disjuncture preventing this work of literary fiction from fitting into the nonfictional cultural products presented by Mosireen, Kazeboon, and other organizations, Hamilton tells the

Scotsman: ‘I’ve had to imagine myself into some situations, and some sectors, but I don’t think there’s anything in [the novel] that is fictive’ (

n.a. 2017, n.p.). In

The City Always Wins, the Chaos media collective is depicted with a neurological metaphor as ‘a cerebral cortex at the center of the information war’ (

Hamilton 2017a, p. 47). This technological dynamism is mirrored in the form of the first section, which is replete with interpolated tweets and a plethora of perspectives on the revolution and its aftermath.

‘Today’ narrates events between November 2012 and August 2013, which are fast-moving and caught up in the moment, composed more of mainstream, seemingly neutral newspaper headlines than of passionate, one-sided tweets. One of the protestors, Hafez, who was previously doing a PhD in London, speaks wistfully in the ‘Today’ section about the nobility of dying in the Eighteen Days

2 for the revolutionary cause (168). But, from mid-2012 onwards when the Ikhwan or Muslim Brotherhood leader Mohamed Morsi won Egypt’s first and only democratic election, deaths were becoming an ignoble and quotidian reality. Many Egyptians swiftly came to feel that Morsi was following the despotic footsteps of Mubarak in ruling the country. Not only that, but he was also using his authority—in the name of religion (Islam)—to turn the Egyptian social, political, and economic scene into a system that only worked for one section of society (Muslim Brotherhood men). Morsi simultaneously disenfranchised other groups and their interests. He stripped oppositional groups, especially the women among them, of their human rights. Apart from the Eighteen Days, when ‘sexual harassment was remarkable because it was rare’ (

Langohr 2013, p. 19), women demonstrators were sexually assaulted and raped in large numbers in the months and years following the revolution, and sexual violence is explored with sensitivity and anger in ‘Today’.

The dates of ‘Yesterday’ remain unspecified but, as Lindsey Moore points out, they must be ‘during the Sisi era that commenced in July 2013’ (

Moore 2018, p. 203). Under Abdel Fattah el-Sisi’s premiership, repression got even worse. In his virtuosic journalistic exploration

Fractured Lands: How the Middle East Came Apart, Scott Anderson points out that ‘less than a year after Sisi took power, there were already far more political prisoners in Egypt’s jails than there had ever been under Mubarak’ (

Anderson 2017, p. 132). In this post-

coup d’état period, the hope is largely lost (even if there are a few slivers of optimism at the novel’s end). Hamilton’s male protagonist Khalil temporarily returns to his diasporic home in the US, and the unstructured writing evocatively reflects his decision to give up on his radical political aspirations. ‘Yesterday’ is narrated from Khalil’s often stream-of-consciousness focalization when the young man, old before his time, seems physically exhausted, mentally defeated, and nostalgic for the Eighteen Days. For the rest of this essay, I will trace the diminishment of the social media revolution’s great promise, and the rise of politically-committed art as a possible alternative, in the approximately two years narrated in Hamilton’s novel.

2. A Revolutionary Family

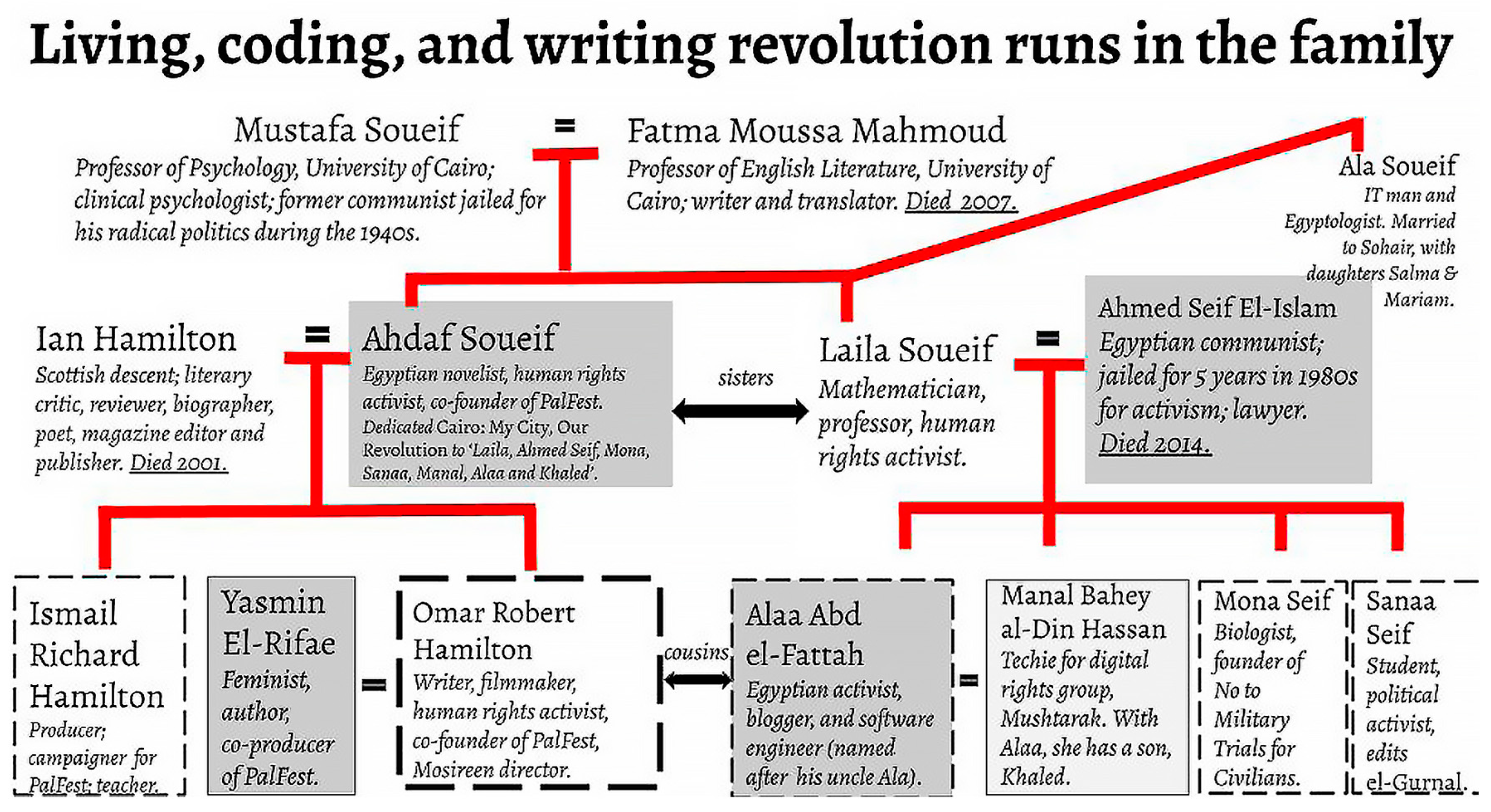

Living, coding, and writing revolution run in Hamilton’s family, as can be seen from

Figure 1, below. Four members of this family are worth discussing in some detail: Alaa Abd el-Fattah, Ahdaf Soueif, Ahmed Seif El-Islam, and Yasmin El-Rifae. Elsewhere, Scott Anderson has written extensively about Hamilton’s aunt, the mathematics professor and activist Laila Soueif (

Anderson 2017, pp. 11–17, 55–70, 77–82, and so on); while others from this interesting dynasty warrant further investigation.

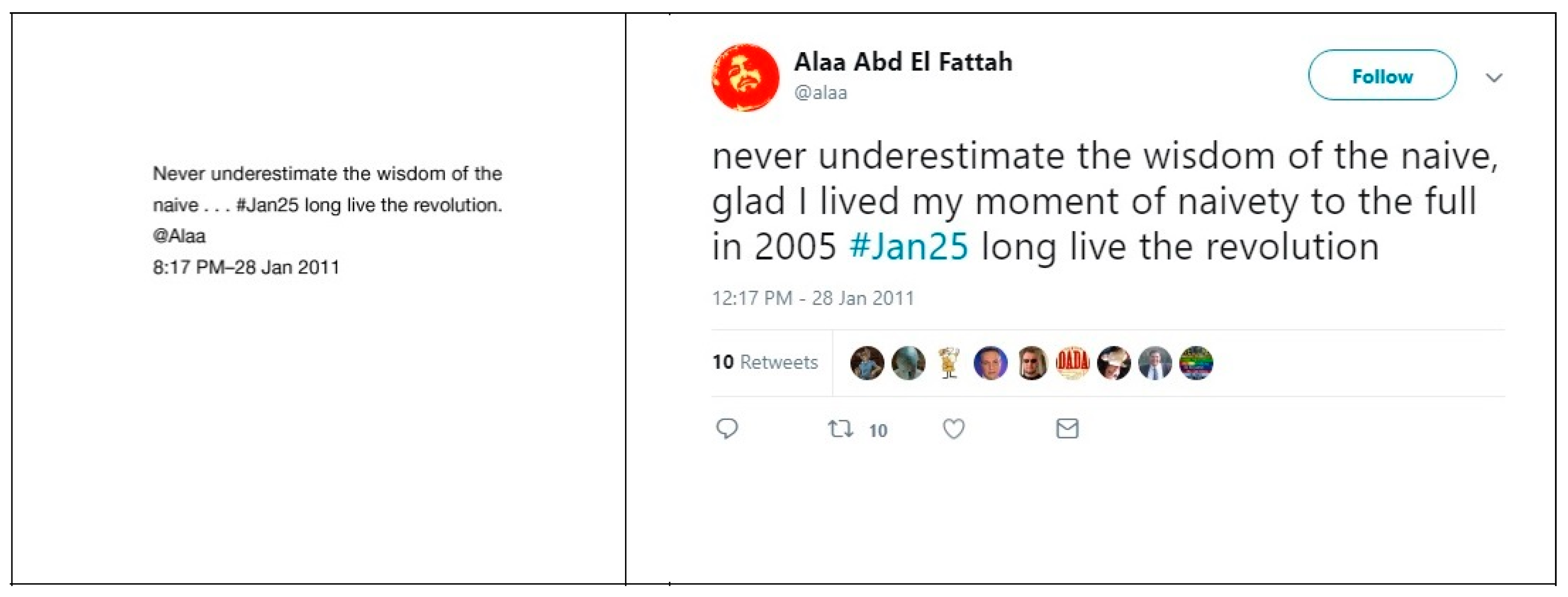

Hamilton’s cousin, the blogger and revolutionary activist Alaa Abd el-Fattah, was arrested (not for the first time) in March 2013 and sentenced to five years in jail in October 2014 for the leadership part he played in protests. This unjust detention inspired the hashtag #FreeAlaa and multimedia campaigns for his release. Yet the young man languished in jail until March 2019 and is still heavily surveilled (

Masr 2019, n.p.), in part due to trumped-up charges concerning his Facebook activity early on in the Egyptian Revolution (

Anderson 2017, p. 195). Hamilton dedicates

The City Always Wins to Alaa, writing that it ‘

would have been a better book if I’d been able to talk to you’ (

Hamilton 2017a, n.p.; emphasis in original). The author uses Alaa’s Twitter feed as the repository of an alternative, oppositional history of revolutionary struggle, which is recognized in the Acknowledgements at the novel’s end. Alaa’s tweets and other writing are testimonios (

see Beverley 2004;

Rege 2006) speaking for other young people who have been imprisoned. As Hamilton writes of a fictional young man killed in protests: ‘[t]he martyr dies for his testimony’ (

Hamilton 2017a, p. 32). In 2016 Alaa smuggled an article to the

Guardian from his prison cell in which he contrasted 2011’s mood of optimism with the desolation widely experienced five years later, writing in despair that ‘tomorrow will be exactly like today and yesterday and all the days preceding and all the days following’ (

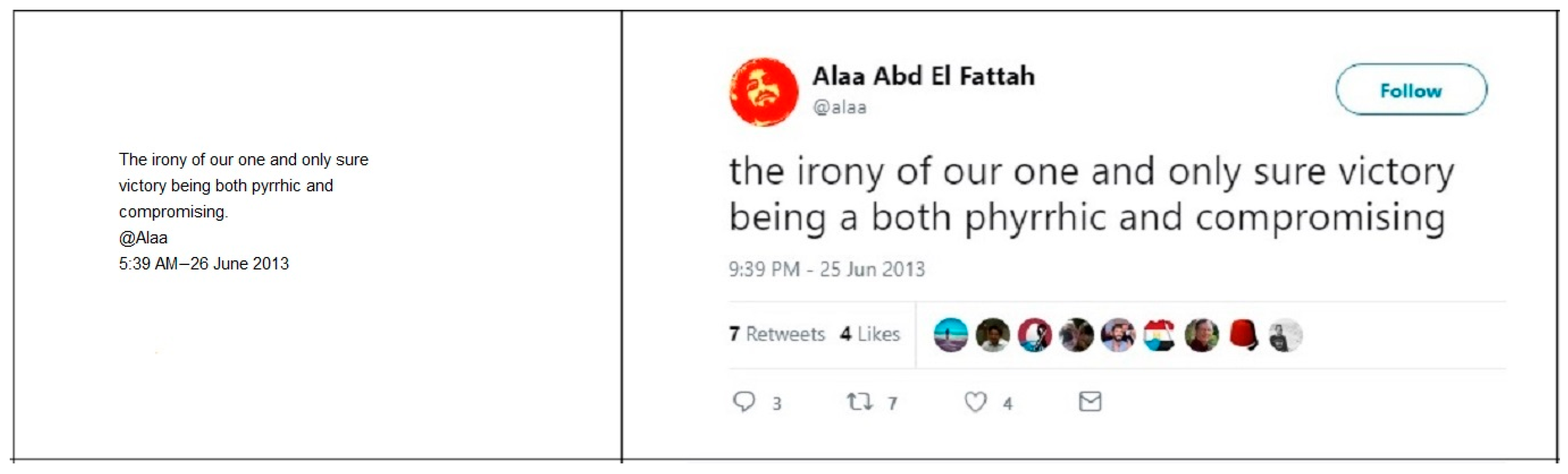

El Fattah 2016, n.p.). As such, it is likely that Hamilton’s novel’s three-part structure is also inspired by his cousin, conveying the heady sense of hope at the start of the revolution, followed by its slow erosion.

Alaa makes several shadowy cameos in The City Always Wins. For instance, in the novel’s opening chapter set in the hospital morgue, Mariam sees this famous activist, ‘the curls of his hair framing his face as she had seen it on television’ (6), hears his voice courteously advocating that autopsies are carried out for the dead, and later searches for him but cannot find him. At the end of ‘Tomorrow’, his image appears at a rousing public screening of a film about the Eighteen Days as he holds his baby son Khaled in his arms and orates about the Maspero martyrs. In ‘Today’ and ‘Yesterday’, Alaa disappears into headlines and news feeds, this disembodiment signalling his silencing through incarceration. In the novel’s closing pages, Khalil writes the absent Alaa an anguished letter, praising the activist’s and his wife Manal’s bravery, berating his own cowardice, and bemoaning ‘the obviousness of our defeat’ (279).

This bleak political landscape is a far cry from the months immediately after the revolution, when Hamilton’s mother the Egyptian diasporic novelist Ahdaf Soueif held that ‘[o]ptimism is a duty’, while noting that the fight might take longer and prove more difficult than was first thought (

Soueif 2011a, n.p.). This author found herself in the position of having to act as a commentator during the revolution. At first, she felt frustration at being unable to experience in their fullness the eighteen days of the Tahrir protests. But Soueif came to the conclusion that her role was the business of interpreting, contextualizing, and representing: ‘In revolution, you can’t not be a participant’ (

Soueif 2011a, n.p.). She describes the book she produced about the revolution,

Cairo: My City, Our Revolution, as being a revolutionary act. It was conceived of, written, and published with the intention of furthering the aims of the revolution, rather than simply commenting on it. Like

The City Always Wins, this nonfiction book is dedicated to Alaa (Soueif’s nephew)—as well as to the other members of his nuclear family. To convey the dynamic nature of the Egyptian movement, Soueif even invents a verb: ‘I tried to “revolute” and write at the same time’ (

Soueif 2012, p. xiv). In Soueif’s son’s book, written five years later in a much darker time, there is a similar invention of a word—‘revolutionists’ (see 64, 69, 98, and so on) instead of the customary ‘revolutionaries’. Both writers therefore show frustration with the existing language around resistance, striving for a new vocabulary to express these protests’ fluid form.

Soueif’s brother-in-law and Hamilton’s uncle Ahmed Seif El-Islam belonged to a communist cell as a young man and spent five years in jail from 1984 to 1989. Seif explained in an interview that a bell was rung before each of his torture sessions, and to the end of his life the sound of a bell made his ‘body shake’ (qtd. in

Stork 2014, n.p.). During his jail stint, Seif read up on Egyptian law, and soon after his release was called to the Bar. For the next quarter-century, his was a loud voice for human rights in Egypt. He considered his equal-opportunities campaigning against torture his greatest achievement as a lawyer, telling his interviewer: ‘We managed to create a social consensus against torture. That didn’t exist 10 years ago’ (qtd. in

Stork 2014, n.p.). During the Eighteen Days Seif was held in detention for two days, and he then witnessed his son Alaa and daughter Sanaa being put behind bars in 2013. Sanaa was released after 15 months, but Seif died in August 2014 without seeing his son paroled.

Egypt’s human rights activism is a history that includes many feminist campaigners—some secular, some believing Muslims or devotees of other religions—who have claimed and continue to demand freedom from oppression due to gender. The novel demonstrates that Hamilton is inspired by these demands, coming as he does from quite a matriarchal family. His wife Yasmin El-Rifae’s online essays shed light on the backlash that women have suffered for attending protests. This backlash is severe, and includes lewd comments, groping, and rape. Such assaults cannot simply be put down to mob behaviour, for some of the atrocities were committed by the authorities as they sought to ‘discourage female participation in public life’ (

El-Rifae 2014, n.p.). Their abuses include the notorious virginity tests, which function simultaneously as victim-blaming and cover for sexual torture; Hamilton writes of ‘[t]he army doctors’ vaginal violations they call virginity tests’ (

Hamilton 2017a, p. 74). But it is important not to cast women—especially Muslim and Arab women, stereotyped for far too long—merely as passive victims. As El-Rifae writes, ‘People remember the mob attacks, but they mostly do not know about the women who resisted them’ (

El-Rifae 2018, n.p.). She is accordingly writing a history of the direct action group for women’s human rights she was involved in, Operation Anti-Sexual Harassment and Assault (OpAntiSH). The work of OpAntiSH is directly referred to several times in the novel. Like El-Rifae, Mariam is involved in OpAntiSH, and Khalil and other men in the novel such as Hafez also directly intervene to combat sexual violence (181), even if the operation is ultimately women-led. In this way, Hamilton presents the novel’s women as having agency to change their own situation. Through free indirect discourse, Mariam thinks: ‘What more cohesive force is there than simply: women’ (151). Like El-Rifae in her articles, Hamilton is quick to emphasize (this time from Khalil’s perspective) that the problem is ‘not Egypt, it’s not Egyptian men, it is simply: men’ (141), the author’s repetition of ‘simply: (wo)men’ underscoring the point. Gendered oppression stems from global patriarchy intertwined with other systemic and structural manifestations of power inequality, but this gets forgotten in simplistic discussions about Arabs’ and Muslims’ ‘sick’ sexuality (see, for example,

Daoud 2016). To conclude this section, El-Rifae writes of women in general and OpAntiSH in particular: ‘When narrative is grabbed by the voiceless, it has the ability to grow with a pace and breadth that is startling and exciting and unknowable. Didn’t the Arab revolutions themselves show us that? (

El-Rifae 2018, n.p.). Let us now zoom in on the Egyptian Revolution and how the voiceless grabbed the narrative in cyberspace.

3. ‘[A]n Army of Samsungs’: Techno-optimism

The alternative media initially seem to possess mass engagement and a global reach, and to threaten power. Early on in the novel, through Mariam’s free indirect discourse, the following vainglorious declaration is made:

The revolution is unstoppable. Chaos will carry news, and tactics and triumphs from Bahrain, Libya, Yemen, Syria, Palestine. Start with the Arab Spring countries, then open to the whole Arab world, then: who knows? They can’t keep up with us, an army of Samsungs, Twitters, HTCs, emails, Facebook events, private groups, iPhones, phone calls, text messages all adjusting one another’s movements millions of times each second. An army of infinite mobility—impossible to outmaneuver. All they know to do is pull the plug, cut the line. And the world saw what happened when they tried that. They have no moves left.

At the end of this excerpt Mariam thinks back to 28 January 2011, when Hosni Mubarak tried to ‘pull the plug’ on picketers’ plans for mobilization. The president shut down Egyptian internet access for what ended up being a five-day clampdown. As Mariam’s thoughts suggest and Noam Cohen’s journalistic investigations confirm, this had an inverse effect to that intended by the regime. Instead of stopping the protests, the blackout galvanized more people to join the resistance. One activist told Cohen that Mubarak’s strategy at first left him feeling ‘digitally disabled’. However, the activist soon discovered that he didn’t miss the internet in those revolutionary days, declaring: ‘Tahrir was a street Twitter’ (qtd. in

Cohen 2011, n.p.).

The early part of the block quotation indicates the kind of techno-optimism upheld by Hamilton’s fictional dissidents. (That said, it may be a case of the lady protesting too much, as Mariam’s exultant statement immediately follows her worries about protest fatigue and the possible dwindling of crowd numbers at future events.) Mariam tries to hold fast to the belief that social media are an empowering social force, preventing human rights abuses from being hushed up as they were in the past. These

shabab (youths) appear to revel in the fact that #Egypt was the top trending hashtag of 2011 (

Friedman 2011, n.p.). Mariam points to the creative, open-source, and resistant nature of her ‘army of Samsungs’. She believes that the peaceful and itinerant tactics of the online media will never be overcome. Indeed, social media have successfully connected global communities and disseminated a wide range of news outputs, bypassing analogue censorship methods. According to Paul Mason, different platforms are availed for various practical ends:

If you look at the full suite of information tools that were employed to spread the revolutions of 2009–2011, it goes like this: Facebook is used to form groups, covert and overt—in order to establish those strong but flexible connections. Twitter is used for real-time organization and news dissemination, bypassing the cumbersome ‘newsgathering’ operations of the mainstream media. YouTube and the Twitter-linked photographic sites […] are used to provide instant evidence of the claims being made.

This chimes with Hamilton’s representations of the fast pace of online activism.

Facebook is referenced in the novel more than any other forum, which accords with Mark Zuckerberg’s supremacy in the global market. In Egypt, as elsewhere in the world, Facebook dominates, in 2010 commanding an audience of about five million, and becoming one of the country’s most popular websites (second only to Google). By the start of this millennium’s second decade there existed ‘more Facebook users than newspaper readers’ in Egypt (

Lim 2012, p. 235). Unsurprisingly, then, Facebook activism was a major catalyst for the pivotal 25 January protests at Tahrir Square. On 7 June 2010, two policemen arrested a 28-year-old called Khaled Said in a cybercafé where he was allegedly trying to upload a video of police dealing in drugs. Said was beaten and then tortured to death, sparking regular protests organized by Wael Ghonem and other admins working on the Facebook page ‘We Are All Khaled Said’. This page was established the month of Said’s death, June 2010, and by 2015 it had attracted in excess of four million likes, playing an ‘important role [… in] distribut[ing] information, coordinat[ing] decision-making, and ke[e]p[ing] up the momentum’ (

Rieder et al. 2015, p. 11). The social network’s influence is emblematized in the fact that one Egyptian couple named their baby ‘Facebook’ in the heady days of February 2011 so as to honour the platform’s significance in the revolution.

As both Mason and the fictional Mariam suggest, some of the most easily discernible uses of Facebook are the formation of groups, both public and private; organization of events; and dissemination of material such as podcasts and videos. More subtly and intangibly, Facebook enables the creation of virtual communities out of ‘a sense of togetherness and a common identity’ (

Gerbaudo 2012, p. 15). The community-formation benefit is tacitly recognized by a neighbour of Khalil’s. This middle-aged man congratulates the youngster on what his generation have achieved in making the army answerable for its actions, wryly exclaiming: ‘You kids and that Facebook of yours’ (

Hamilton 2017a, p. 68). The network also produces instant endorsements and emotions, sustaining the idea of ‘circles of friends’ (

El-Nawawy and Khamis 2013, p. 4). This affective dimension is apparent when Khalil receives a laudatory Facebook message about his activism from an ex-girlfriend in America, which makes him swell with ‘virile pride’ and not a little posturing (

Hamilton 2017a, p. 54). Libidinal lure is therefore at least as much of a factor on social media as platonic friendship, tallying with one of Zuckerberg’s aims that Facebook should facilitate flirtation when he set it up at Harvard University in 2004.

As is intimated in Mason’s reference to ‘news dissemination’, Twitter is more current affairs-focused, and less friends-oriented and personal than Facebook. In The City Always Wins’ first section, Hamilton captures the exhilarating way in which Twitter connects strangers with each other, sets ‘alight’ (146) the touch-paper on various important topics, and allows organizations like Chaos to attract ‘a thousand new followers […] every day’, 20). At the street level, the platform encourages activists to ‘live tweet’ about particular protests, using hashtags to make their topic threads easily discoverable, and passing on information about particular opportunities or dangers. For instance, Mariam tweet-directs her fellow activists to go to Tahrir Square and demonstrate against a police attack (39). Even in the darker ‘Yesterday’ part, when a massacre leaves Hafez gravely injured, activists tweet desperately for his blood type. Within minutes several volunteers have arrived at the hospital to donate their O-negative blood (258). By this point in the novel much of Twitter’s exciting potential has been exposed as illusory, but the platform still has its uses, albeit in a limited, local way.

Twitter usage is not just the preserve of the shabab. The older-generation Abu Bassem, father of a fictional Eighteen Days martyrs Bassem Gouda, tells Khalil early on: ‘I’m just doing a tweet for people to watch this [TV] show’ (24). The fact that Abu Bassem cannot talk and tweet at the same time and uses the slightly inappropriate verb ‘doing’ (instead of ‘composing’ or ‘writing’) for his tweet indicates that social media are more laborious and less enabling for the older man than for his son’s generation. Abu Bassem will never find social media a source of mindless relaxation the way Khalil does, given that the latter sees smoking and the checking of Twitter as equivalent ways to unwind (81). However, Abu Bassem’s zeal to generate publicity for the television interview being given by Manal, Alaa’s wife, is no less intense than that of the younger activists. As well as its efficacy when it comes to internal organization, Twitter enables the revolutionaries to talk to Egypt’s mass media and to the outside world. Khalil acts as a fixer for a French television crew making a documentary about the Egyptian Revolution, and receives a private message from ‘Jim from Huffpost’ (56). This suggests that his work with Chaos and publications on the microblogging site have yielded high-profile global connections.

Moving to the extradiegetic level, Hamilton draws on Twitter as a living archive providing entry into an alternative, resistant history of revolutionary struggle. Various political factions are represented through heteroglossic Twitter interactions. This polyphony is reflected in the typography, given that a traditional serif font is used for the main body text, whereas a sparse, contemporary sans serif typeface usually denotes electronic communication in the novel (for instance, Arial for tweets). The Twitter posts by Alaa Abd el-Fattah (@Alaa) and other accredited tweets are real, even if they have sometimes been edited and/or translated (for some examples, see

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4).

Elsewhere in the novel, all the anonymous tweets appear to be loosely based on actual posts but with key details altered and their authors’ handles removed. As well as calling people out to protest, tweets are thus used as a narrative tool. For example, an entire section recounting a bloody riot against Al-Ahly FC supporters at a football match in Port Said—perpetrated by Al-Masry fans while the authorities stood by—is narrated through invented tweets (110–12). The fragmentary tweets evoke the rapidly rising death toll on 1 February 2012, which eventually exceeded 70 fatalities, and a widespread sense of anger and confusion as events unfolded. Supporters of Cairo’s Al-Ahly club, known as Ultras, had been ‘crucial in coordinating and waging street fights with the police’ during the revolution (

Gerbaudo 2012, pp. 142–43). Speculation swirled that the authorities’ inaction came as ‘revenge’ (

Kirkpatrick 2012, n.p.) for fans’ incendiary activities the previous, tumultuous year.

As

Mason (

2013) demonstrates, YouTube played an important role in global uprisings as an evidence broadcasting site. If it was Facebook that publicized Khaled Said’s murder by torture, it was his attempt to upload a video documenting police corruption that triggered that torture in the first place. Launched in 2005, the video-sharing site rapidly attracted both controversy and a vast number of clicks. Over time, it was put to action holding the mighty accountable for their transgressions, as Christopher J. Schneider recognizes: ‘amateur-produced content can now include surreptitious recordings of people engaged in deviant acts […], including actions of police misconduct and brutality’ (

Schneider 2015, p. 229). And as Hamilton puts it about his work with Mosireen: ‘a good video, quite simply, brought people out on to the street. […] When the state denies it is killing its citizens, it is politically powerful to prove they are lying’ (

Hamilton 2019, n.p.).

In addition to videos’ use-value in protests and other quests for justice, they also have a crucial affective and relational dimension. For example, the digital migrant Abu Bassem, whom we met earlier ‘doing a tweet’, accesses YouTube endlessly to view his deceased son Bassem at a happier time on earth. Abu Bassem fails fully to understand the process of internet searching as he ‘mov[es] through the learned motions’ of wielding the mouse to click through to a YouTube search (29). However, ‘muscle memory’ (298) from repeated viewings allows him to watch footage of his son and his mahragan band performing their digitally manipulated music. Later in the novel, the grieving father will panic about the possibility of this video being taken down: ‘What if Bassem doesn’t appear? What if it breaks or is lost or deleted and the last time was the last time I will ever see him’ (298). Here Hamilton points to the ephemeral nature of internet content and to how some viewers are helplessly dependent on user-generated footage subject to the vagaries of YouTube’s terms of service, wider intellectual property laws, or state censorship.

Taken together, social media function as connectors of people. Web 2.0 has the ability to mobilize people en masse because of its instant, participatory nature; as Mariam thinks: ‘How can they control us when, at last, we can all see one another, talk to one another, plan together?’ (21). We have seen that Hamilton embeds tweets in the fabric of this fragmentary, experimental novel, and social media posts interrupt and punctuate the narrative. This formatting is akin to the experience of scrolling through digital media, and it reflects the real lives of millennials like these. For instance, Mariam’s phone rings once and vibrates twice in a short time when she is caring for Khalil, who is lying injured after taking a bullet in one march in Tahrir Square late in 2011. The media has so strong a presence that it has leaked into the novel’s structure, not just furnishing Hamilton with content but being written into his novel’s palimpsestic form. This is a uniquely appropriate texture for his novel about the Egyptian Revolution.

In her foreword to the collection

Tweets from Tahrir, Ahdaf Soueif asserts, ‘I think we’re agreed: Without the new media the Egyptian Revolution could not have happened in the way that it did. […] [I]t was the instant and widespread nature of the new media that made it possible to recognize the moment and to push it into such an effective manifestation’ (

Soueif 2011b, p. 9). Writing the same year as Mubarak’s unexpected and welcome ouster, Soueif’s optimism is understandable if somewhat breathless. That said, she astutely realizes that even without social media there would still have been some sort of revolution, which is confirmed by Maeve Shearlaw five years later: ‘the uprisings didn’t happen

because of social media. Instead, the platforms provided opportunities for organisation and protest that traditional methods couldn’t’ (

Shearlaw 2016, n.p.; emphasis in original). Moreover, Soueif’s point about the way in which these media’s immediacy and reach shaped the nature of the revolution is well made. Let us now turn to more pessimistic analysis of (social) media’s role in the Egyptian Revolution.

4. ‘[T]he Toxic Fumes of the Internet’: Techno-pessimism

If it starts to seem that the technology’s images and words have an intrinsic power over the streets, it is important to remember that social media are reliant on human push factors. In other words, these media are merely instruments put to various uses by different constituencies. Although the internet is itself neutral, its anonymity and virality have also fostered the circulation of conspiracy theories and fake news. Ultimately, those social media platforms depicted in the novel turn ‘toxic’ (

Hamilton 2017a, pp. 198, 218), being increasingly shown to be a ‘Pandora’s box’ (198) of dis- and misinformation, conspiracy theories, fake news, and regime policing.

The state media—whose Radio and Television building in Maspero Mariam and her friends had demonstrated at but stopped short of breaking into—are the regime’s mouthpiece. Some of their tactics are to spread confusion and to divide and rule different communities. For example, state broadcasters disseminate anti-Christian propaganda designed to set the majority of Muslims against their Coptic neighbours. One of the greatest regrets of Hamilton’s protestors that recurs like a refrain in the novel’s final pages is ‘I wish we’d taken Maspero’ (235, 239, 275). If they had done so, they could have ‘broadcast the new voice of the revolution’ (288) and thus reversed the damage of the regime’s television and radio programming. But at that time they made the ‘mistake’ of not confronting the army (159), then still being seen as a potential ally. The result is a growth in the strength of counter-revolutionary forces and the snuffing out of the shabab’s hope for ‘bread, freedom, and social justice’ (31). Whereas at The City Always Wins’ inception, the internet seems to bolster young Egyptians’ political agency, this promise is diluted and damaged by the authorities’ deployment of electronic censorship and surveillance. Cyber activists in Egypt are ultimately stymied and oppressed by the state’s digital oppression and control of internet infrastructure.

In February 2013, as a headline included in the Today section makes plain, Egypt issued the ‘[f]irst court order in history’ (148) directing a shutdown of YouTube. The banning of the video-sharing site was on the pretext of YouTube’s role from July 2012 onwards in disseminating the offensive

Innocence of Muslims film (

Hauslohner 2013, n.p.). This low-budget movie, branded by religious studies expert Bruce Lawrence as ‘YouTube terrorism’ (

Lawrence 2012, n.p.), was made by a right-wing Christian collaboration in the United States. The group was led by Egyptian Coptic Christian and former illegal drug manufacturer and fraudster Nakoula Basseley Nakoula (working under the false name of Sam Bacile). Nakoula was supported by fellow Copt Morris Sadek, who was on record as saying, ‘My enemy is the God of Islam’ (qtd. in

Lane 2012, p. 18). These two men and five other diasporic Egyptians involved in

Innocence of Muslims’ release were sentenced to death

in absentia by a Cairene court in November 2012 (

El Deeb 2012). The Qur’an-burning American pastor Terry Jones was also said to have acted as a promoter for the picture. Anti-Islamic content was overdubbed afterwards, allegedly without the actors’ knowledge and to their consternation. Fierce protests which erupted in the film’s wake led to over 50 deaths in eight countries. Pakistan and Afghanistan seem to have borne the brunt, with 23 and 12 deaths respectively, but Egypt experienced at least one killing of its own. However, we should resist the temptation to flatten the so-called Muslim world into a homogeneous monolith, instead taking a cue from

Max Fisher (

2012), who writes in his notes to accompany an ‘Annotated Map’ of the protests that local political factors had greater influence than religion in the riots. Fisher gestures, for example, towards the turbulent situation in the nations affected by the Arab Spring, to which we could add attacks in Pakistan and Afghanistan by the Taliban and by US drones. These protests are not yet resolved in Egypt, as can be seen in the fact that in May 2018 the Sisi government revived attempts to block YouTube over

Innocence of Muslims (

Dahir 2018, n.p.), the original court order having been defeated on appeal in 2013.

The notion of the internet as a bastion of free speech and leveller of social hierarchies has also been challenged by the Cambridge Analytica revelations. One strand of Carole Cadwalladr’s (

Cadwalladr 2018) famous journalistic investigations for the

Guardian concerned Facebook’s clandestine harvesting of users’ personal information, and the subsequent deployment of this data to effect political change. Hamilton refers to such debates when he writes from Khalil’s pessimistic perspective near the end of the novel:

What can we do with information or facts when the only currency that counts is guns and lies, when all anyone wants are guns and lies? Will we go on chattering forever in our digital echo chambers as Facebook throws up algorithmic borders around us uncrossable as the Berlin Wall, irresistibly invisible as gravity, corralling us into digital polities of irrelevant impotence that we occasionally emerge from, blinking, to discover the physical world of violence seething all around us?

Hamilton draws readers into the dilemma

3 through Khalil’s use of the second person plural pronoun. His subsequent deployment of the epistrophe, an ornament of rhetoric involving the repetition of the same word or words at the end of successive clauses (‘guns and lies’), gives the violence and deceit heavy emphasis, which is added to by the italicization and assonance. Moreover, Khalil’s similes of borders, walls, and the pull of gravity foreground his central idea of an irrelevant digital polity or state that almost blinds digital natives to the violence that exists outside this cosy cyber world. Khalil shows that such an insular view is not uniquely Egyptian through his universalist, global reference to the Berlin Wall. The allusion also provides readers with a glimmer of hope, since that divisive partition was of course eventually pulled down.

Thousands of Arabs have been arrested (and more often than not beaten up, refused a fair trial, and tortured) as a result of their activity on social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, and, increasingly, Instagram. This includes many young people based in countries whose revolutions were successful, including Tunisia and—at least initially—Egypt. Hamilton refers to one counter-revolutionary instance when three influential Facebook admins are rumoured to have been killed and further activists badly injured (167).

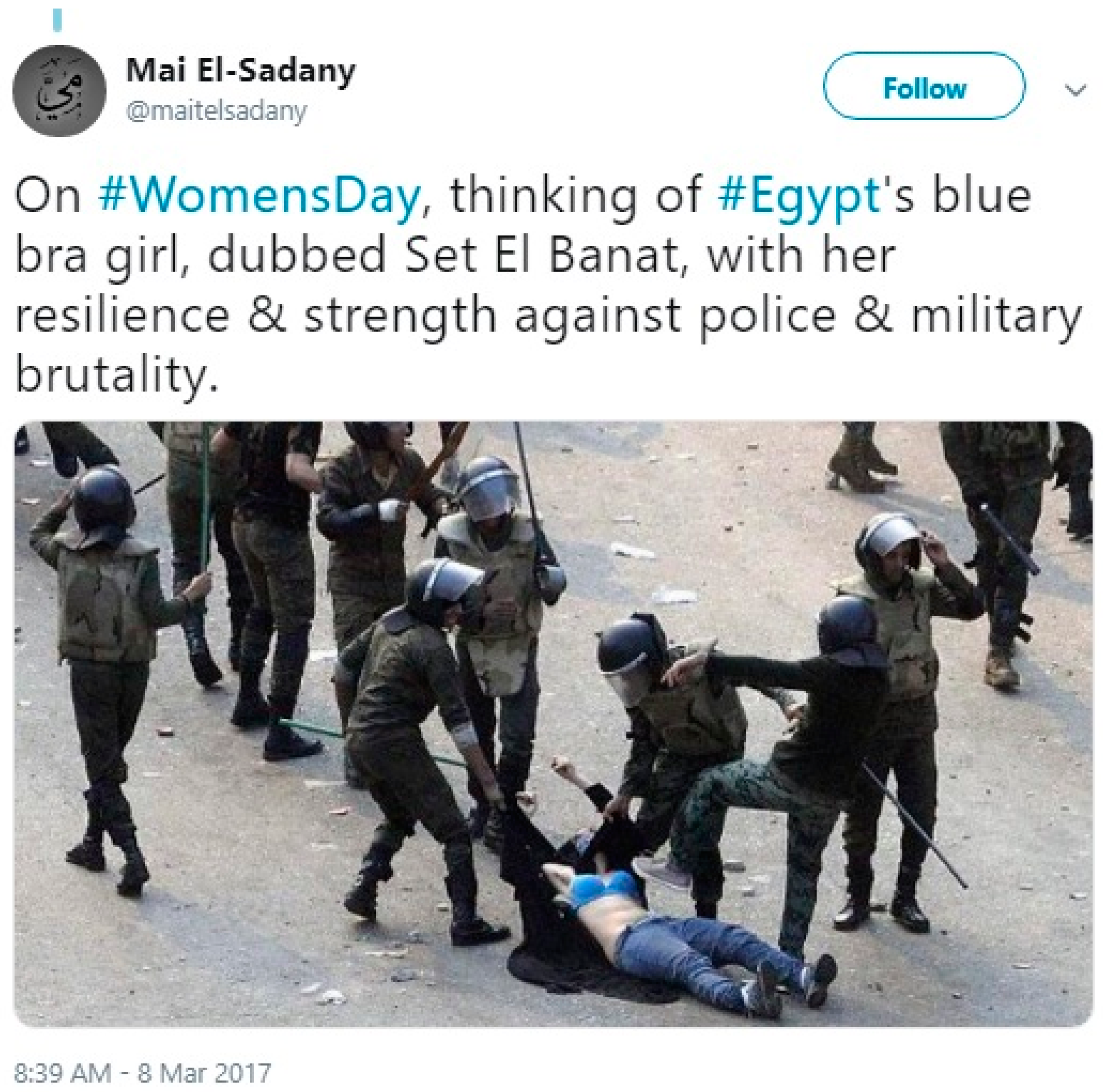

In the uprisings that began in North Africa, we have seen that women were prominent among the dissenters in publicly voicing their demands for long overdue economic and political reforms. A photograph of a woman stripped of her

abaya by army officers became a social media phenomenon, with bloggers, tweeps, and Facebookers criticizing the Egyptian establishment’s use of sexual harassment to keep women dissidents in line. This photo of the woman exposed in her blue bra (

Figure 5) is alluded to at several moments in the novel.

Hamilton reflects the fact that this blue bra became popular in stencilled revolutionary graffiti (98), but that there were also conspiracy theories around the girl. Unaccredited whispers go around as follows:

If you look at the picture you’ll see it’s not actually a boot. He’s wearing running shoes. Which is proof that these men were infiltrators. Sent to discredit the army. […] Why was she wearing this sultry blue bra? Where did she think she was? And she’s clearly not wearing anything else under there, so what’s really going on here?

Khalil is angered by these sorts of rumours coming from what he calls ‘[t]he radio commentariat [...] The Facebook warriors. The sycophants working through the night to poison people’s minds’ (99). These conspiracy theorists suggest the woman staged the confrontation or was ‘asking for it’ or, with impressive mental gymnastics, both at the same time.

Yet it would be wrong to assume that the demise of the social media revolution is entirely due to such external pressures as conspiracy theories, mainstream propaganda, electronic eavesdropping, and successive governments’ subjugation of online insurrection. There are also significant problems that emerge from the inside out. First, there is indubitably a digital divide in Egypt, between young and old, urban and rural, and rich and poor—with the former always more switched on than the latter. Estimates of this connective asymmetry vary, but in his book

Tweets and the Streets Paolo Gerbaudo cites one study that puts the number of Egyptian households with internet in 2011 at just 25 per cent. (However, at that time internet cafes were still very popular, accounting for a higher number of users invisible to this particular survey.) Moreover, it is sobering to read that ‘only 4 per cent of Egyptian adults were members of Facebook, and only a miniscule 0.15 per cent of them had a Twitter account’ in the year of the so-called social media revolution (

Gerbaudo 2012, p. 49). Thus, when Mariam scornfully corrects an older relative for her inaccurate diction when the latter claims that the young woman and her friends use particular language ‘on the Face’ (

Hamilton 2017a, p. 155), behind the humour are signals that Facebook political chatter is far removed from most Egyptians’ daily concerns.

Twitter can be even more elitist and disconnected from provincial Arab life than Facebook. Gerbaudo writes, for example, of a privileged group of ‘Twitter pashas’; the platform’s hierarchical structure of ‘followers’, rather than ‘friends’; and its slow adaptation to the Arabic language (

Gerbaudo 2012, pp. 70–74, 144). Hamilton portrays Twitter’s negative traits as including its thoughtlessly addictive quality and the existence of trolls who spout their vitriol across the network (

Hamilton 2017a, pp. 19, 200, 218). Khalil, who was once enlivened by clicks, retweets, and likes, stops reading Twitter altogether as his country’s online mood worsens.

One of the features of the Eighteen Days that was so impressive was the diversity of protestors at Tahrir Square and the other revolutionary cities in Egypt. They came from all professions, ages, classes, and ideological persuasion, some of them wired and others contentedly living offline lives. It was only after the fall of Mubarak and the clearing of the square that Egyptian society became segmented again. Online activists found themselves more and more preaching to the converted amongst people from similar backgrounds with the same adroitness for electronic communication technologies.

Another problem faced by online activists when they try to widen their circle of influence is solidarity fatigue, a conundrum summed up by Hafez in the question, ‘What do you do when nobody looks anymore?’ (244). Working as a cameraman and photographer, Hafez can only show an ever-multiplying number of the same types of atrocity. To his dismay, Chaos’s audience hunger to see something new and begin deserting their social media: ‘Each [video …] has to be more shocking than the last’ (245). People’s desire for instant ocular gratification cannot be sated by ‘the same thing’ on a loop (233). What had once seemed an energetic, web-based hacktivism degenerates into slacktivism as people stay home and Tahrir Square becomes ever more sparsely populated by demonstrators.

Difficulties arise not just from the attrition of Chaos’s casual support, but also from within the committed inner circle. Writing especially about Turkey’s Gezi Park protests of 2013, Zeynep Tufekci links these with the recent movements in the Arab world and Iran:

Now, big protests can take place […], organized by movements with modest decision-making structures that are often horizontal and participatory but usually lack a means to resolve disagreements quickly. This frailty, in turn, means that many twenty-first-century movements find themselves hitting dangerous curves while traveling at top speed, without the ability to adjust course. Although participatory leaderlessness and horizontalism are a source of strength in some ways, it is also a treacherous path over the long haul.

This statement is salutary for describing the swift rise followed by the slow-motion fall from grace of Hamilton’s

shabab. Disagreement emerges during Morsi’s presidency when Hafez’s girlfriend Nancy wants to take a more hardline, even vigilante stance against Ikhwan Islamists than the rest of her comrades. She breaks off her romantic involvement with Hafez and leaves Chaos. The others are enraged when they read her bigoted Twitter feed over the months to come, but they lack potency against a rogue actor of this sort because of the leaderless nature of their organization, as identified by Tufekci. In the end, the ‘top speed’ of online activism which propels change is also behind the group’s ‘frailty’. Social media may offer innovative organizational methods and a comforting sense of community. That said, their use is capriciously faddish, meaning they can easily come unstuck as a basis for insurrection.

5. Creative Insurgency

A more durable and profound option for (social) media is art: what Siobhán Shilton dubs an ‘aesthetic of resistance’ (

Shilton 2013, p. 131) or Marwan M. Kraidy calls ‘creative insurgency’ (

Kraidy 2016, pp. 206–7). In this last section I discuss Hamilton’s evocations of what art can achieve that (citizen) journalism cannot, and how this applies to the novel’s portrayals of one art form in particular: music. Musicians used their popularity to push for change during the years of revolution in Egypt, and ‘popular protest music […] helped to shape and articulate emerging desires and aspirations’ (

Valassopoulos and Mostafa 2013, p. 638). In his book on the status and function of art during the uprisings,

The Naked Blogger of Cairo, Kraidy defines what he means by creative insurgency:

Inventiveness is vital to rebellion, but revolutionary publics place politics above aesthetics. Creative insurgency uses art to shape revolutionary political identities and promote cross-border solidarities, but it is not limited to art making. It is in the seesaw of bodies-in-pain and bodies-in-paint, in the cycle of artful protest and protest art, and in the debate about art that creative insurgency unfolds.

As with Barbara Harlow’s notion of resistance literature (

Harlow 1987,

2012), this is not art for art’s sake; rather, it is art that puts political commitment first. In light of this art’s inventiveness and political resonance, it is unsurprising that oppressive regimes are quick to suppress it. In Egypt, for instance, the then-unknown musician Ramy Essam came to Tahrir and popularized revolutionary slogans through his musical renditions (

Valassopoulos and Mostafa 2013, p. 648). For this act of creative insurgency, he was beaten and tortured by the military in March 2011 at the National Museum, a site of great civic and symbolic importance in Cairo (

Aidt 2011, n.p.).

There is some ambivalence around the role of art in

The City Always Wins. The repetition of the highly ambivalent sentence ‘No time for artistry’ (

Hamilton 2017a, pp. 160, 161, 170) shadows this forth well. The terse, ungrammatical, colloquial nature of this sentence suggests the activists’ hurry. It also allows Hamilton to evade specificity as to whether this is no time for artistry (the revolutionary period makes art inappropriate), or his characters have no time for artistry (they are too busy). Equally, the word ‘artistry’ probably denotes art, whether high or low, but it could also have connotations of deceit—con artistry. Furthermore, as we have already seen, it is something of a problem for the revolutionists that they are

artless, lack formal discipline, and have no leader. This is one of their greatest strengths, but it does leave them open to the manipulations and violence of the Muslim Brotherhood, the army, and the police.

Sound studies, which I have explored elsewhere in relation to Kamila Shamsie’s

Home Fire (

Chambers 2018), also proves an enabling lens for reading Hamilton’s novel. As with Shamsie’s jihadist character Parvaiz in his role as a sound engineer for ISIS, Khalil works as a sound man for Chaos. Khalil believes that sound is more ‘cerebral’ and less ‘exploitative’ than vision (

Hamilton 2017a, p. 144). He puts his faith in the persuasive properties of sound, spending hours in his studio working on his recordings of the violence. He tries to make these videos’ ‘aural architecture’ (30) as sharp and syncopated as possible, so that the podcasts that Chaos puts out win over more hearts and minds to the revolutionary cause.

Khalil was born in the US, the son of an Egyptian mother and a Palestinian father. The father, Nabil, was sent to America to further his career as a violinist by a mother worrying about the West Bank’s violence. There, the young man renamed himself Ned out of defeat at his exile from Palestine, and tried to expunge the Arab parts of his identity. Khalil feels resentment at this cultural effacement, imagining asking his father, ‘What sewed up the Arabic in your tongue?’ (73), and thus positioning his father as a mute and mutilated man. But one thing the older man and his son have in common is a shared love of music, particularly jazz. Observe, for example, this quotation:

Cairo is jazz: all contrapuntal influences jostling for attention, occasionally brilliant solos standing high above the steady rhythm of the street. […] Yes, Cairo is jazz. Not lounge jazz, not the commodified lobby jazz that works to blanch history, but the heat of New Orleans and gristle of Chicago: the jazz that is beauty in the destruction of the past, the jazz of an unknown future, the jazz that promises freedom from the bad old times.

In their respective reviews of the novel for the

Guardian and the

LA Review of Books, the British-Syrian novelist Robin Yassin-Kassab (

Yassin-Kassab 2017) and Cairo-based journalist and organic intellectual Farid Farid (

Farid 2017) both find the jazz metaphor striking. Indeed, Yassin-Kassab fleetingly takes the first sentence, ‘Cairo is jazz’, as a metaphor for Hamilton’s writing. This makes sense, for there is a large cast of characters but the voices of Khalil and Mariam soar above the others. Through his use of the musical idea of contrapuntal notes—in other words, the use of multiple independent harmonies, each of which is accorded equal importance—Hamilton alludes to the work of his family friend Edward W. Said.

4 In

Culture and Imperialism Said develops his idea of contrapuntality, a concept offering an open, conjugative mode of reading that breaks down spatial and temporal boundaries. Through his image of autonomous melodies, Said draws readers’ attention to important points of overlap even between ‘experiences that are discrepant, each with its particular agenda and pace of development, its own internal formations’ (

Said 1993, p. 36). Developing this idea of musical counterpoint, he reads colonial and postcolonial texts alongside each other, arguing that to do otherwise ‘is to disaffiliate modern culture from its engagements and attachments’ (

Said 1993, p. 71). This sounds a harmonious note with the block quote’s depiction of past, present, and future coming together in an art that is neither airbrushed nor whitewashed but is instead full of ‘heat’ and ‘gristle’.

It is significant that Hamilton chooses jazz as the musical style to associate with the creative flowering and apocalyptic violence and resistance of Cairo. For jazz, as Michael Titlestadt reminds us, ‘is about asserting trajectories of becoming […]; it is perforce improvisation within a form’ (

Titlestad 2002, p. 149). The whole novel could be considered as a work of jazz, in terms of both form and content. In addition to being improvisatory, how the book sounds is as important as how it reads. Farid recognizes this in the headline to his review, ‘Pulsing Instantiations of a Revolution’ (

Farid 2017 n.p.). That word ‘pulsing’ hints at the text’s insistent rhythms, which we see in incantatory sentences such as ‘Not lounge jazz, not the commodified lobby jazz that works to blanch history, but the heat of New Orleans and gristle of Chicago: the jazz that is beauty in the destruction of the past, the jazz of an unknown future, the jazz that promises freedom from the bad old times’. Another issue that would be valuable for future scholars to pursue is an application to Hamilton’s resonant novel of that part of affect theory which intersects with sonic studies (see

Thompson and Biddle 2013,

2017). And then perhaps researchers could bring out the way this novel functions as a kind of immanent critique of some aspects of the Arab Spring and, even more so, of Egyptian society and its inability to complete the 2011 Revolution.

Regarding content, the novel’s revolutionists are like jazz players, responding to the authorities’ draconian moves and improvising their protests. This is perhaps best illustrated towards the end of the novel when Khalil puts his MP3 player in a bin (302). Readers at first assume that this is a gesture of despair at the political soundscapes he had earlier tried to create which came to nothing, but he then turns it into a revolutionary radio transmitter. The radical radio station it broadcasts will disseminate a pre-recorded MP3 mixing together political discussion, ‘

world news, new music, and notes from the cinema’ (303; emphasis in original). One is reminded of Frantz Fanon’s essay ‘This is the Voice of Algeria’, in which the Martinican psychiatrist avers:

It became essential […] to be informed both of the enemy’s real losses and his own. The Algerian […] had to enter the vast network of news […]. [T]he Algerian found himself having to oppose the enemy news with his own news. The ‘truth’ of the oppressor […] was now countered by another, an acted truth.

Opposing the enemy news with his own news is exactly what Khalil does when he deposits the transistor in the bin and starts broadcasting. Read in this key, his pirate radio is creative insurgency writ large, given its extemporary,

bricoleur, and oppositional nature.

Yet more than jazz or any other music from the novel’s soundscape, it is the raucous din of bombs, sirens, gunshot, screaming, and the ‘white noise of helicopters’ (231) that reverberates. Certain phrases such as a boy crying desperately ‘She’s my sister, she’s my sister’ are repeated as though on a loop. Khalil reminds readers that ‘[s]hell shock is a brain traumatized by sound, by violent reverberations detonating through the fabric of your mind, a sonic flood washing away your synapses’ (280). As the revolutionists are defeated, turn traitor, are killed, or leave, Khalil’s previously pleasurable relationship with sound turns sour. He realizes ‘there are no sounds anymore, no pure sounds, nothing distinguishable from the crowd, nothing but static attacking the world around it, a flood of sonic waves all broken and ugly’ (228). Perhaps his newly troubled relationship with the soundscapes around him is best evoked through ‘Doctor_02022012.mp4’, the sound file that haunts Khalil after a female medic dies in his arms at one of the protests. He cannot bring himself to listen to this MP4 but has various simultaneously horrifying and erotic dreams about his encounter with the doctor and her brutal murder. In light of such violence, he wants to ‘throw up from all the words’ (285) people spout about the army’s good intentions or the revolutionists as foreign agents. One of the things he likes about Mariam is that she sees no need to ‘fill the silence with pointless noise’ (300).

6. Conclusions

In

Tweets and the Streets Paolo Gerbaudo makes the important point that social media are neither intrinsically positive nor negative. Rather, their significance lies in what people do with them. Gerbaudo writes of these media’s specific uses in political mobilization and the way they lend themselves to ‘a

choreography of assembly as a process of symbolic construction of public space which facilitates and guides the physical

assembling of a highly dispersed and individualised constituency’ (

Gerbaudo 2012, p. 5; emphasis in original). Gerbaudo holds that electronic campaigning is not as spontaneous and leaderless as it is widely perceived, but is instead a choreographed assemblage (see also

Puar 2007). His image drawn from dance speaks to the novel’s representations of sound (especially jazz) as a progressive art form.

Moreover, the ethically neutral and fluid essence of social media is recognized by Hamilton in this techno-realist and very inventive novel. One of his characters, Malik, a pugnacious revolutionist from Glasgow, declares: ‘Mobile phones and the internet, mate. You need more than just an army to control people’ (86). Although this seems like one-dimensional techno-optimism, the quintessentially British terms ‘[m]obile phones’ and ‘mate’ hint at the diasporic roots of many of the protestors (Malik and Hafez from Britain, and Khalil from the US). This perhaps distances the revolutionaries from ordinary Egyptians who are less in thrall to apps and the web. As one Cairo graffito has it, in a twist on Gil Scott-Heron’s song, ‘The Revolution Will Not Be Tweeted’ (

Scott-Heron 1970). However, if Twitter cannot do the revolution justice, the site has nonetheless woven itself into the fabric of this revolutionist and resistant novel.

The City Always Wins showcases both the positive and negative aspects of social media but is never patronizing about them.

Ultimately, this novel is all about the issue of voice, the marginalized, and those young people ‘who will not be silenced’ (

Hamilton 2017a, p. 32). Almost at the novel’s end, Hamilton leaves us with two glimmers of sanguinity after all the horror. The first is an image of bats as the reincarnation of the fallen rebels who were martyred in the Eighteen Days and their aftermath. And second Khalil spots a small marker of their protest which is not dead but has for now vanished underground. Both instances can be observed in the following passage:

I hold my hand out into the night, strain to reach out as far into the nothing as I can. Bats click past in the darkness. The boat comes closer, its music echoing off both banks surrounding me and reaching out with me into the breeze, the darkness. The bats cut through the air around me like an innocent. I think, sometimes, that our martyrs live their second lives in them, the bats, the true inheritors of the city. [Y]esterday […] when I was coming downstairs I saw something familiar. I couldn’t believe it at first but it was really there: a sticker on my neighbors’ door. It says Free Alaa.

Because bats move through sound using the ‘sonic perfection’ of echolocation (303), this trope make readers think of the political reverberations still sounding from the martyrs’ deaths. The revolutionists use these political echoes as a way to guide them when there appear no chinks of light. Hamilton undermines that well-worn metaphor of illumination representing moral goodness and enlightenment. In the murky moral world of Sisi’s Egypt, the cover of darkness is kinder than the glaring light of day. As Hamilton puts it, through Khalil’s focalization: ‘The daylit world is worse’ (212). The revolutionists must allow themselves to be led by their ears rather than relying on sight, responding to ideas and art as opposed to the immediacy of experiences and toxicity of tweets. The ‘

Free Alaa’ decal also gives hope, showing that even the strangers next door are still thinking of the young campaigners’ sacrifices and anticipating their release. One day, it seems, there will be another ‘Tomorrow’.