Abstract

This essay explores the aesthetics of Bertolt Brecht’s compositions of poetry with photography in the so-called photo-epigrams of his 1955 book War Primer. The photo-epigrams have mostly been viewed and appreciated as interventions in photography; but in this essay I aim to show their novelty and efficacy as poetic inventions. To do so, I draw on Karl Marx’s and Walter Benjamin’s views apropos the decline of poetry under modern, industrial capitalism to argue that Brecht, in his photo-epigrams, is responding to—and attempting to counter—a specific problem at the heart of modern poetry: the crisis in perceptibility and accessibility. By coupling poems with photographs—in unique and uniquely politicised ways—Brecht provides a resonant critique of the deadly ideologies of the ruling classes engaged in World War II, as well as a method for addressing the decline in the readability of poetry in the modern era.

Keywords:

Brecht; War Primer; poetry; photography; Benjamin; Marx; photo-epigram; alienation; ideology 1. Introduction

This essay concerns a relatively little-known book by the rather well-known Bertolt Brecht. Brecht’s Kriegsfibel—I will be referring to it as War Primer, its most common English translation—was first published in the German Democratic Republic (GDR) in 1955, only a year before its famed author’s death. This publication differs to the versions of the book that appeared in the following decades, versions which either included aspects of the work removed from it by the author upon request by the GDR’s cultural authorities—this is the case with the 1994 German version, which included an addendum comprising pieces left out of the book’s initial edition—or they presented a revised version to, putatively, better represent the author’s original intentions, as can be seen in the long-overdue English translation, which appeared in 1998.

In all cases, War Primer is a collection of what Brecht terms fotoepigrammen (photo-epigrams), page-long compositions of a press photograph clipping—sometimes with its original caption or accompanying news story—coupled with a rhyming quatrain written by Brecht himself. Whilst the exact relationship between the photograph and the poem is what I seek to interrogate and reinterpret in some detail in what follows, I will note briefly, for the purposes of introduction, that the photographs are taken from reports—as published in German, Scandinavian, English, and other journalistic sources (mostly newspapers)—to do with the events and personalities associated with World War II, such as Hitler and Churchill, the Blitz, and the Normandy landings; and the poems are seemingly written in a compositional association with the pictorial images. I desist from describing the relationship between the poems and the pictures in simpler terms—by claiming, for example, that the poems are mere responses to the images of the War, or that the poems are ekphrastic—because one of the aims of my study is to precisely complicate the rapport between the literary and the visual in order to arrive at a new account of this fascinating work, an account which, I hope, will do justice to what I see as the true, radical novelty of Brecht’s invention of the photo-epigram. In this essay, I argue that the photo-epigrams of War Primer make a startling and inventive intervention, not only in the reception of visual imagery but also in the literary milieu, by proposing a method for the reinvention and revival of the marginalised art of poetry for a modern readership.

Claims may be made apropos the dearth of scholarly or artistic attention concerning War Primer—it remains, according to Bernadette Buckley, writing in this very journal, “shockingly under-analysed” (Buckley 2018, p. 1). This is a fact that can be verified by noting that in one of the key book-length studies of Brecht’s oeuvre, Fredric Jameson’s Brecht and Method (Jameson 1998), War Primer had not at all been mentioned. A more recent study of Brecht’s methods, Anthony Squiers’ An Introduction to the Social and Political Philosophy of Bertolt Brecht: Revolution and Aesthetics (Squiers 2014) also entirely ignored War Primer. In her important study of GDR poetry, Karen Leeder takes note of the influence of a number of Brechtian poetic tropes on future GDR poets—such as the image of life in an “asphalt city” (Leeder 1996, p. 55), a phrase from one of Brecht’s earliest poems—but she does not at all register any influence that War Primer may have had on other poets of Brecht’s immediate milieu. However, whilst certainly not as well-known as some of its author’s other creations—Die Dreigroschenoper (The Threepenny Opera), the much-loved English language standards such as ‘The Ballad of Mack the Knife’, and ‘Pirate Jenny’ adopted from the Opera, Mutter Courage und ihre Kinder (Mother Courage and Her Children), etc.—War Primer has received some attention since its various manifestations. In addition to the composer Hanns Eisler using several of the poems for the cantata of a song cycle soon after Brecht’s death, recent years have seen the publication of book-length studies by Welf Kienast (2001) and Georges Didi-Huberman (2009). In English, War Primer has been the subject of a number of erudite, informative articles, and it has served as the basis for the London-based artists Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin’s 2011 photographic book War Primer 2.

I shall not, at any rate, claim that my study has been occasioned by the work’s supposed marginality. My aim here is to take a close look at the compositional dynamics of Brecht’s unique combining of (found) photographic images with (authored) lyrical poems in a manner that, to the best of my knowledge, has not been done before. Whilst there exists a number of incisive explorations of War Primer from a visual perspective—such as David Evans’ perceptive reading, which begins with the claim that Brecht’s “book merits attention” primarily because “it represents Brecht’s most sustained, practical engagement with photography” (Evans 2003, p. 8)—there exist no sustained accounts of the book from a primarily literary perspective. Kristopher Imbrigotta’s 2010 article, whilst paying some attention to “the combination of the photograph and the epigram” (Imbrigotta 2010, p. 42), sees the poem as little more than a text that “helps to contextualize the photograph” (Ibid., p. 39). Even an article published in the journal Poetics Today was less concerned with the poems of War Primer, per se, than “the various modes of reading and interpretation” required for “deciphering the image” (Long 2008, p. 217).

This lack of attentiveness to the book’s literary dimension is not at all surprising. The pages of War Primer do strike us, initially, as visuals with supplementary texts. Indeed, Brecht’s naming the literary texts epigrams reinforces one’s perception of the poems as secondary, derivative, and peripheral. Nevertheless, I shall argue that such a perception would be quite limited—perhaps even incorrect—because Brecht’s quatrains profoundly challenge, even negate, our focus on the visuals rather than paying tribute to or commemorating the images à la Grecian epigrams (i.e., lapidary inscriptions beneath marble statues). My main aim is to present the photo-epigrams as artistic inventions, almost on par with Brecht’s other, more well-known inventions, such as episches Theater (epic theatre) and Lehrstücke (learning-play). According to the reading of War Primer presented in my essay, Brecht’s picto-poetic compositions recognise and challenge, with a very high degree of originality, one of the fundamental dilemmas of modern poetry and provide us with a singular model for confronting this dilemma.

Brecht’s War Primer offers us, as has been argued by previous commentators, undeniable critiques of the visual ideology of modern warfare and militarism. Brecht’s selection and arrangement of press photographs and his photomontage-like juxtaposition of these with often acerbic, at times scandalous, poems undermines and disrupts the easy, manipulative transmission of hegemonic discourses of the War—and not only those of Brecht’s immediate nemeses, the Nazis—and presents us with official military propaganda distorted and transformed by a rigorous artistic defamiliarisation or, put in Brecht’s own parlance, Verfremdungseffekt (alienation-effect). Brecht’s method distances or alienates the (potentially passive) viewer from the modern regimes of perception that depend on viewers naively receiving factual, photographic images and their subliminal ideological messages. War Primer, in short, makes (press) photography intelligible.

But what I would like to argue in this essay is that this powerful work also recognises a profound problem in our modern relationship with the medium of poetry and, more specifically, with the genre of the lyric poem. The ideological dimension of the photographic—and also, of course, cinematic—image in modern capitalist culture is certainly one phenomenon to which Brecht responds with War Primer. But the pages of this book, if read inversely, that is, if seen as poems with accompanying images and not the other way around, recognise the dramatic decline of the value of the poetic in the modern world, and, as I aim to show, counter the modern reader’s view of the poem as innately obscure or inaccessible. Brecht’s method reveals the modern poem’s (intensified) semantic immanence or un-sensual referentiality as a problem and not as something to be fetishised (as has been the case with many poetic modernisms). And, following on from this diagnosis, he offers novel—albeit occasionally slapdash—solutions to provide the poem with sensory, visual–factual referents to alleviate the poem’s hermetic stance towards the real. In War Primer, Brecht sets out to make poetry sensible.

2. Marx, Benjamin and the Modern Crisis in Poetry

It was none other than Karl Marx who made some of the most poignant observations apropos poetry’s decline and degradation in the modern era. And it should, therefore, not come as a surprise that some of the strongest assessments and responses to this situation come from thinkers and poets associated with Marxism, including Brecht and his friend and contemporary, Walter Benjamin.

In a fragment of an incomplete manuscript written in Paris in 1844, a young Marx depicts poetry as something reduced to an alibi or a tool in the hands of the embattled ruling class of the feudal nobility in their ideological struggle against the ascendant new ruling class, the capitalist bourgeoisie. According to Marx, the agrarian aristocrat “lays stress on the noble lineage of his property, on feudal mementos, reminiscences, the poetry of recollection” and accuses the bourgeoisie of lacking “honour, principles, poetry” (Marx 1967, p. 83). With the intensification of the political conflict between the two classes and the onset of the bourgeois revolutions of the mid-19th century, Marx observes, in The Communist Manifesto, that the victorious bourgeois “has stripped of its halo” the work of the poet, “hitherto honoured and looked up to with reverent awe”, as it has “converted” the poet into one of “its paid wage-labourers” (Marx 1986, p. 82).

Does this conversion necessarily devalue poetry? Marx responds, in Theories of Surplus-Value (1863), that “capitalist production is hostile to certain branches of spiritual production”—by spiritual Marx means mental or non-physical, and not religious—and the key example of a production subjected to capitalist hostility is, indeed, “poetry” (Marx 1863, not paginated). This hostility is not purely cultural or ideological—to do, for instance, with the mental association made between poetry and the ancien régime milieu of aristocrats and absolutism that the modern European bourgeoisie violently supplanted in the 19th century—but, in the first instance, a material or economic attitude. Whilst the capitalist mode of production is not at all hostile towards a “writer who turns out factory-made stuff for his publisher”—and publishing as a capitalist industry in fact depends on the productivity of such a “literary proletarian” for the extraction of surplus-value—it does not deem a poet productive and hence valuable, because a poet such as Milton “produced Paradise Lost for the same reason a silk worm produces silk. It was an activity of his nature” (Marx 1951, p. 109). The poet, because of a natural commitment to producing use–value, cannot be relied upon to produce something with a discernible exchange-value, and his or her work is therefore not simply dismissed and marginalised in a modern world dominated by capitalist production—with whatever degree of systemic hostility—but also, in some instances, made redundant. Epic poems “can no longer be produced in their world epoch-making, classical stature”, according to an important passage in the Grundrisse, because “the material foundation, the skeletal structure” of the pre-modern milieus in which the epics were produced have entirely vanished (Marx 1993, p. 110). Does the same fate not await other genres of poetry, such as short, non-epic poems (i.e., lyric poems) and the art of poetry in its entirety?

This is the question taken up famously by Walter Benjamin in his 1939 essay, ‘On Some Motifs in Baudelaire’. Whereas Marx views the topic from a general, universal economic–productional perspective, Benjamin approaches it by considering the specific genre of lyric poetry and the particularity of the poetry of the 19th century French poet, Charles Baudelaire. Benjamin equates what Marx describes as the poet’s halo with what he terms aura, and, in the same way that, according to Marx, in the milieu of social relations the poet’s reduction to a wage-earner—and a mostly unsuccessful one at that, due to poetry’s innate resistance to exchange–value production or commodification—results in the halo being stripped off the poet, Benjamin argues that “the disintegration of aura makes itself felt in [Baudelaire’s] lyrical poetry” (Benjamin 1992, p. 185). For Benjamin, Baudelaire’s poems are conditioned by the poet’s assumption of modern “readers to whom the reading of lyric poetry would present difficulties” (Ibid., p. 152). In agreement with Marx, Benjamin observes that “the climate for lyric poetry has become increasingly inhospitable” and that “conditions for a positive reception of lyric poetry have become less favourable” (Ibid., pp. 152–53). However, whereas Marx attributes this crisis in poetic appreciation to economic–productional causes, Benjamin instead focuses on literary aesthetics. This is not to say that Benjamin—irrespective of the (supposed) peculiarity of his individualised take on Marxism—is a so-called deviationist apropos Marxism, but that he sees the poetic—and, more broadly, the literary and the aesthetic—as developing in tandem with the material/economic. And it is, very interestingly, the technological advent and development of photography—with all its capitalistic commercial, ideological, and aesthetic preconditions and consequences—that is most strongly registered as both a cause and a symptom of the inhospitable, unfavourable conditions to which poetry is subjected in the modern world.

According to Benjamin, the disintegration of the aura in Baudelaire’s poetry “occurs in the form of a symbol which we encounter in the Fleurs du mal almost invariably whenever the look of the human eye is invoked” (Ibid., p. 185). The poems of the in/famous volume, and their supposed obscurity and inscrutability, are connected to a failure on the part of the poet’s gaze, his inability to see clearly—because of “the remoteness which a glance has to overcome” (Ibid.)—caused by the culturally ascendant “barrenness and lack of depth” found in photographic imagery (Ibid., p. 183). Photography causes a crisis in perceptibility because “the camera records our likeness without returning our gaze”—in photography, the (human) subject stares not into the eyes of the photographer but into the lens of the camera (or is, even when not looking directly into the camera, primarily visible to the eyes of the camera and not to those of another human), a subtle albeit crucial fact which negates “the implicit expectation that our look be returned by the object of our gaze” (Ibid., p. 184). The negation of this perceptual expectation—which clearly resonates with the classic Marxian theme of alienation—undermines our ability to see properly or be attentive to the others, and it is this phenomenon that Benjamin finds at the core of the loss of aura in Baudelaire’s poetry.

Whilst the “profoundly unnerving and terrifying” advent of early photography (Ibid., p. 182) may be key in situating the ennui, spleen, revulsion, and horror found in the Fleurs du mal, the perceptual crisis associated with photography is also implicated in an aesthetic generality, which is specified in the “breakdown” of “correspondence” between the poem’s phrases and words and sensory experience of scents and visual images (Ibid., p. 180). Despite all this, Baudelaire’s collection of lyric poems did become a commercial success, no doubt due to the book’s notoriety, but also because it was one of the “rare instances [of] lyric poetry [being] in rapport with the experience of its readers” (Ibid., p. 153). And yet, for all the reasons noted in Benjamin’s essay and summarised above, Baudelaire’s was “the last lyric work that had a European repercussion; no later work penetrated beyond a more or less limited linguistic area” (Ibid., p. 188). As such, Baudelaire may be described as the poet who succeeded because he foresaw and forged a rapport with his readers’ experience of the decline in the poetic. He was listened to because he prophesied correctly that soon, in a world dominated by visual photographic images, other than poets themselves—the partisans of a limited linguistic area—no one else would listen to poets.

It is precisely this situation that Brecht’s photo-epigrams seek to disrupt and overturn in War Primer.

3. Brecht and His Photo-Epigrams

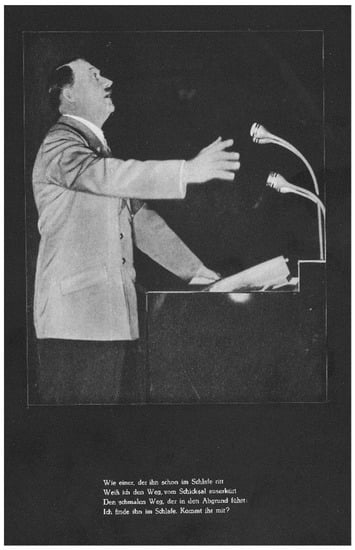

Irrespective of which version of War Primer one chooses to read, the very first image that one encounters atop the book’s first photo-epigram is that of Hitler in a posture, either natural or staged, of public speaking (Brecht 1968, bild 1; Figure 1). The visuality of the image—it being a photograph extracted from a journalistic source—and also the immediately recognisable human form dominating the image—the unmistakable Fuhrer in one of his emblematic poses—may be seen to firmly establish the genre of the text as one premised on the visual and the visually significant.

Figure 1.

Brecht. 1968. Kriegsfibel. Berlin: Eulenspiegel Verlag. Bild 1.

But the perception of the (visually-founded) prominence of Hitler is undermined (literally) by the poem inserted under it (my translation):

I know the path of destinyBecause I’ve walked it in my sleep.In my dreams I’ve found the road to the deepDark chasm. Coming with me?

As noted in the previous, before-mentioned studies of War Primer, this poem and those like it can be seen as attempts at subverting the ideological discourse embodied in the photographic image. Hitler’s speech, in the actual situation signified by the photograph, would have probably been an expression of Nazi military expansionism, entailing promises of swift victory and the like; but in the photo-epigram, the Nazi leader’s actual words have been omitted and replaced by (Brecht’s articulation of) their obscene, phantasmatic death drive. Whilst the Hitler of the press photograph may have triumphalist, optimistic things to say to his audience, the Hitler of Brecht’s photo-epigram is an unashamedly deluded fantasist who admits his vision will lead his people to a “deep, dark chasm” (Abgrund in the original German, meaning abyss).

This exposition of a truth contra official, ruling class ideology is certainly one of the key features of War Primer, and it is one of the main reasons for the book’s enduring relevance and applicability for critiquing other militarist ideologies. (In the recent 2011 artistic homage/adaptation by Broomberg and Chanarin, for example, images of the so-called War on Terror were imposed on top of the images of WWII in Brecht’s book). But what would happen if we were to read the poem alongside and not in subordination to considering the photograph? Would the work retain its subversive aesthetics, or would it be reduced to a formal experiment? And what could be the grounds for such a rereading of War Primer?

The most obvious reason for taking War Primer seriously as poetry—and not solely as an experimental and/or critical picture book—is that Brecht was, of course, a committed and prolific poet. The poems collected in his first collection, Hauspostille (Domestic Prayer Book, 1927), were written whilst Brecht began and developed his career as a theatre-maker, and many of his most celebrated plays feature his poetry in the form of songs, choral hymns, and other musical adaptations of his lyric poetry. And herein one finds one of the difficulties of approaching Brecht’s poetry qua poetry—be it the ballads set to music as part of his epic theatre, or the epigrams coupled with photographs in War Primer—since one finds that Brecht, more so than most other major poets of his milieu, was willing to have his poetry come in contact with—at the risk of being dominated by—other art forms. Such a willingness may be seen as a sign of Brecht’s accepting (the general contours of) Marx’s and Benjamin’s views apropos the decline of poetry. Was he not, in deference to the cultural superiority of photographs and popular entertainment, disguising or parasitically attaching his poems to more significant, more successful art forms, and by so doing further condemning poetry, however unintentionally, to marginality and insignificance?

Such an account—of a fame-hungry, Hollywood-bound Brecht sacrificing poetry at the altar of culture industry—is a tempting, perhaps even logical conclusion, if we were to view macabre ballads such as those published in Domestic Prayer Book—for example, ‘Von der Kindesmörderin, Marie Farrar’ (‘About the Child-killer, Marie Farrar’) and ‘Legende vom toten Soldat’ (‘Legend of the Dead Soldier’)—as (mere) song lyrics written in anticipation of potential musical vocalisation, or to see the epigrams of War Primer as nothing other than (subversive) literary accompaniments to photographs. However, not only would such a depiction of Brecht and his poetic practice betray the actuality of his commitment to the art of poetry—he would continue to write and publish poetry into the final stages of his career—it would present a simplistic, one-sided, and undialectical account of his cross-media artistic productions.

The musicality of the ballads of Domestic Prayer Book, for example, can be seen as a utilisation of aspects and aesthetics of one form of cultural production (the song) at the service of achieving or heightening a particular effect or aesthetic in another form of cultural production (lyric poetry). In one of the first and most influential English language analyses of Brecht’s poetry, Clement Greenberg writes that Brecht’s is “a kind of modern poetry that gets its character from a flavoring of folk or popular culture” (Greenberg 1941, not paginated). “Everything”, Greenberg writes, “is grist for Brecht’s mill: the Lutheran hymn, Bible versicles, the waltz song, nursery rhymes, magic spells, the prayer, even jazz songs” (Ibid.) As such, it’s not Brecht’s aim to participate in popular culture per se, but to develop a poetics that includes or even “exploits” a flavour of popular culture—by incorporating elements of religious hymns, popular songs, etc.—for Brecht’s own “subversive and anti-literary irony” (Ibid.) According to Greenberg, a poem such as ‘Legend of the Dead Soldier’ may have “the stanza, meter and some turns of phrase, even the motif” of an actual folk ballad, but Brecht’s “content and feeling are utterly opposed to the content and feeling with which this form and [its conventional] theme[s] have generally been associated” (Ibid.).

I am not sure if I agree with Greenberg that irony as such is the sole intended effect of Brecht’s use of popular forms in Domestic Prayer Book and elsewhere—particularly in the light of the normalisations of irony as a dominant style in popular cultural products of late capitalism—but Greenberg’s attentiveness to the specific and specifically subversive quality of Brecht’s engagement with popular forms (and some of their associated content) is incisive. Brecht’s use of the folk ballad genre may be a populist, even anti-literary, gesture—or a gest, in Brecht’s own parlance—but it takes place entirely within the space of the poem, and is at the service of producing a certain, subversive quality—be it irony, satire, horror, or anything else—as a quality of the poem itself. The opposition or contradiction detected by Greenberg—between the macabre, politically charged content and feelings of Brecht and those of the original oral ballad form—could come about only as the result of the poetic being brought into conflict with, and not at all subordinated to, the folk song; all within the immanence and singularity of a poem published in a collection of poetry (irrespective of whether or not the poem would be sung by an actual/oral balladeer). And it is precisely such a perspective on the dialectical relationship between the literary-poetic and the non-literary/popular (e.g., photographic) in Brecht’s method that would enable us to see War Primer not simply as a book about the images of WWII, but also as a significant—and significantly radical—contribution to modern poetry.

I would therefore like to return to the first page of War Primer and the photo-epigram that includes a press photograph of Hitler at the lectern, but now I shall take account of the content and feeling of the epigram alongside—and not in submission to—the picture. But how can such a reading be conducted, particularly by one, such as myself, immersed in a culture of visual signs, in which the lyric poem has declined even further than it had at the time of Brecht and Benjamin? And would it be possible, at any rate, to simultaneously see/read a text as well as a picture on the very same page of a book?

To address both the (modern) disparity between the sensibility of the photograph and of the poem, and to also avoid having to construct a challenging—even impossible—form of reading (by, say, transforming Brecht’s photo-epigrams into digital images that could be rearranged via split screens, animation and the like), I would like to propose reading the photo-epigrams as epigram-photos. That is to say, by shifting the vertical order or hierarchy of perceptual priority, and by reading the poem prior to looking at the photograph. The intention of this method of analysis is not to devalue the photographic image—the hugely hegemonic cultural worth of which could frankly not be affected by anything done by me, in this humble literary essay, irrespective of my intentions—but to elevate the visibility of the poem, if necessary (and only contingently) at the expense of temporarily suspending the supremacy of the visual image.

We may therefore observe that Brecht’s poem on the first page of War Primer can be seen as a striking example of precisely what Benjamin saw as one of the key dilemmas of modern poetry as articulated in the poetry of Baudelaire: the question of the human eye and the encounter with the remoteness which a glance has to overcome. The speaker of Brecht’s quatrain claims to have seen “the path of destiny” in their “sleep” and have also found “the road to the deep dark chasm” in “dreams”. These highly abstract, metaphorical, and ethically conflicted objects—a good path to greatness, and a bad road to perdition—are seen by the speaker only with their eyes closed (i.e., in sleep). As such, when directly addressed by the speaker and asked whether or not the reader will “follow” the speaker, the reader is faced with an ethical dilemma occasioned by aesthetic unreliability. Is the speaker to be trusted as one may—indeed, must—trust and adhere to a (divinely inspired) prophet or visionary, who would lead the reader to “the path of destiny”? Or is the speaker to be dismissed and derided—and, if necessary, fought off—as a nihilist lunatic who will lead the reader towards the abyss and annihilation?

And what makes the (ethically) right decision for the reader impossible is the impossibility of seeing itself, the fact that the speaker has seen both possible eventualities (destiny or disaster) without really seeing either of them; they have only encountered them in a dream. The reader’s uncertainty apropos responding to the speaker’s invitation at the end of the quatrain, then, is nothing other than the uncertainty of the poem’s own meaning occasioned by the lack of visual clarity. What precisely is it that the speaker saw in their dream—a road to triumph or to total defeat? Since the speaker cannot possibly be certain about this, because of the mystery and unreliability of the symbolism of a dream, the reader too is left in a state of uncertainty and confusion.

Read on its own, then, this poem could be seen as an exploration of an imaginative, dreamy state of mind (à la Romanticism) or a distortion of sensual reality in the interest of blurring the boundary between (rational) life and (the irrationality of) art, after the kinds of modernist practices (of Symbolists, Surrealists, etc.) that dominated much of Brecht’s poetic milieu. But Brecht does not leave the poem on its own, in a state of vagueness and openness to a multiplicity of interpretations, as much postmodernist poetry would later aspire to do. Instead, he provides us a with a concrete, irrefutable, and absolutely visible referent: a photograph of Adolf Hitler.

Is the poem’s speaker, then, disclosed, once and for all, as the monstrous fantasist on the verge of unleashing unprecedented atrocities? Yes, but the photograph—if seen as an ingredient or a flavour of the overall photo-epigrammatic composition, and not either as its overarching aesthetic frame nor its ultimate semantic destination—may provide us with a reading that is far more interesting, and far more unsettling and radical, than a mere derision of a commonly loathed historical villain. The reader, in considering the poem alongside the image, may now be provided with a finite signified apropos the identity of the poem’s speaker, and may now know that the speaker’s vision is not at all good and that the dream road leads to something very, very bad. But now the question no longer concerns a simple ethical choice between following or not following Hitler—of course one would not follow him (N.B. War Primer was published after Germany’s apocalyptic defeat and devastation in WWII, after the revelation of the horrors of the Final Solution)—and the poem now concerns the very premise of this choice. Why was the reader at all compelled to consider following or not following someone who had seen something (a figurative road to whatever kind of future) without actually seeing it? Could it be that one of the origins of the War—in addition to Hitler’s megalomania, madness, etc.—was in fact people’s (our own) predisposition and penchant for mystical visions of supposedly inspired individuals?

The combination of the poem with the visual image confronts us with the danger—indeed, the horror—of our own deep, psychological complicity in catastrophes such as World War II. One conclusion that may be drawn from this reading of the first photo-epigram of War Primer—a summary that is conversant with Brecht’s commitment to communism and his other methods and projects—is that here Brecht is countering alienation in a number of its manifestations, such as a mysterious, Surrealist-like poem that, in the absence of a sensible, immediately discernible referent (in the form of the photograph), would have simply baffled and alienated the reader; and Brecht is also attacking the alienating mysticism and fetishism of such a potent opium of the masses as the dreamy visions of a cultish leader who—unlike a revolutionary communist, and instead of organising the people and providing rational, materialist methods for political and class struggle—dominates and exploits the blind being led by the blind.

I am generally sympathetic to readings of War Primer—such as J. J. Long’s (2008)—which try to challenge a perception of Brecht’s work as one adhering rigidly to a certain Marxist project (e.g., to Socialist Realism). But, whatever the eccentricities and deviances of Brecht’s correspondence to a Marxist artistic program, I find it difficult to see Brecht as some kind of proto (Deleuzian) postmodernist whose approach in War Primer, in “its multiple modes of address creates a fluid subjectivity” (Long 2008, p. 221). In fact, as I have aimed to show, it is precisely a subjective fluidity—with its attendant undecidability, passivity, and vulnerability to fascistic, demagogic obscurantism—which is very much in Brecht’s poetic crosshairs. As I have aimed to show, the object of Brecht’s critique in the first photo-epigram of the War Primer is not the bogeyman of a general, liberal democratic consensus outraged by Hitler’s aggressive militarism, totalitarianism, and the like; but it is the consciousness of the masses, alienated and overwhelmed by ideology and fetishism (which, as Marx would argue, is the dominant form of life under capitalism, prior to class struggle), who have become susceptible to the harrowing siren song of the likes of Hitler.

There can be no question regarding the sheer irreverence, playfulness, and iconoclasm of much of Brecht’s work, including his photo-epigrams, but it would also be incorrect to dismiss his commitment to a communism informed by Marx’s theories. The space available to me in this essay sadly does not allow me to explore many pieces form War Primer; but to further demonstrate the point apropos the political impulse of Brecht’s compositions, and to further explore the aesthetics of the photo-epigram, I would like to consider one more piece from the book, albeit briefly. And I would like to pursue this reading by presenting the poem before including the corresponding photograph in my analysis—although I am aware that my reader may already be familiar with this specific photo-epigram—in order to conduct my proposed, inverse epigram-photographic reading.

The quatrain in the 38th photo-epigram of the GDR edition of War Primer (Brecht 1968, bild 38)—it appears as the 15th in the 1998 English edition—can be translated as:

I’m familiar with the law of mobstersAnd am perfectly fine with maneaters.They eat out of my hands. HumanityCouldn’t have found a better defender than me.

If, in its cryptic, dreamlike tone and imagery, the first quatrain of the book bears the influence of German Romanticism and/or French Symbolism, the 38th quatrain is clearly conversant with another significant aesthetic strand in Brecht’s poetry, the macabre cabaret associated with figures such as the playwright and performer Frank Wederkind. As such, the image or the persona in the first two lines is very much the kind of violent flamboyant, cocksure villain one would find in many a performance by Wederkind (e.g., his depiction of Jack the Ripper) or, indeed, in Brecht’s own Arturo Ui. But the second half of the poem depicts the speaker as a self-proclaimed defender of humanity (my humanity is a translation of the original German kultur, which may, of course, be translated as culture, plain and simple; but here it has the grander implication of human civilisation or humanity). Is this presentation of a brutal villain as a potential saviour an indication of Brecht’s irony, as Greenberg may have it? Or does it hint at the speaker’s delusional vainglory, a characteristic of their dramatic persona?

Both readings of the poem are, of course, possible; but the central contradiction—between the speaker’s self-identification as both a supreme chief of stereotypical monsters and also the protector of human culture and civilisation—can also be seen as yet another articulation of one of the key tropes of (Benjamin’s thesis on) the decline of poetry in the modern world: the loss of aura. The speaker’s (vaunted and haloed) role—as the defender of mankind—disintegrates and cannot be maintained because of the contemporaneous image of the same speaker as a familiar to killers and an accomplice to cannibals. And, interestingly, this disintegration is associated with a crisis in perception: mobsters and maneaters (whatever their actuality in, say, 1920s Chicago, or in Grimm brothers’ fairy tales) can only be, in the lexicon of Brecht’s poetics, allegorical and metaphorical. Therefore, once again, these signifiers (as with the path to glory and the road to the chasm in the first quatrain) potentially occlude or obscure the actuality of reference, and occasion a lack of correspondence between the poem’s words and the real world, a lack that is only intensified because of the paradox of the same (figurative) villain being presented as a literal champion of humanity.

And it is here that the form of the photo-epigram presents us with a solution to this perceptual crisis, in the form of a photographic image (Brecht 1968, bild 38; Figure 2):

Figure 2.

Brecht. 1968. Kriegsfibel. Berlin: Eulenspiegel Verlag. Bild 38.

I believe only readers with a rather selective knowledge of history—and wilfully or otherwise ignorant of the Bengal famine, of Churchill’s initial support and admiration for fascism, etc.—would be scandalised to see Brecht present the British leader as someone who handfeeds cannibals. Whilst in the capitalist-democratic West, Churchill assumed—and continues to assume—the role of the heroic opponent to Hitler, in the communist world and the GDR—where War Primer was first published—there would have existed no illusions regarding the politics or policies of the staunchly imperialist, violently anti-communist, and unapologetically militarist Tory leader.

As such, Brecht’s designation of Churchill as an odiously duplicitous figure—not so unlike the equally Janus-faced Hitler of the first photo-epigram who preaches both a utopia of greatness and an unimaginable apocalypse—is very much in keeping with Brecht’s political values. Aesthetically, it is important to note that in this photo—which shows Churchill looking inadvertently the part of a gangster, during an inspection of the British army’s weaponry—verifies a reading of the poem’s hypothesis apropos his personality—that, despite claiming to defend humanity, he is, in truth, a murderous criminal—by providing a concrete, tangible referent to contradict the absurdity of the paradoxical personality of the poem’s speaker. Seen as Winston Churchill, the speaker of the poem is no longer an illusory figure of irony and the like, but one who—particularly in this photograph—returns the viewer’s gaze and undoes the lack of correspondence between the (poetic) word and the (political) world.

4. Conclusions

In one of his unpublished late-1930s ripostes against Georg Lukács’s denunciations of him as a formalist—written at around the same time as the creation of War Primer—Brecht defends the revolutionary integrity of his methods and inventions by writing:

I am speaking from experience when I say that one need not be afraid to produce daring, unusual things for the proletariat so long as they deal with its real situation. There will always be people of culture, connoisseurs of art, who will interject: ‘Ordinary people do not understand that.’ But the people will push these persons impatiently aside and come to a direct understanding with artists.(Brecht 1980, p.84)

My essay has been an attempt at showing the photo-epigram as such a daring, unusual thing. Whilst formally innovative and experimental, these compositions certainly deal with the real situation of many people of Europe who were forced—at least until the entry of the Soviet Union into the War—to take sides with either the deluded genocidal demagogues of fascism or with the criminal oligarchs of imperialist capitalism. The photo-epigrams that directly depict—and, indeed, celebrate—the Red Army’s and the Russian people’s participation in the War (such as those numbered 54, 55 and 58 in the original GDR edition) confirm both Brecht’s commitment to the communist cause—if not to Stalinism—and show that, despite some of the more recent Western appreciations of War Primer that have sought to reify the book as an instance of pacifist literature, Brecht does not desist from praising the courage and ferocity of the warriors of the proletariat and the ordinary people.

But, of course, none of this renders Brecht a mere exponent of communist agitprop. Brecht rejects the cynicism of the connoisseurs of art who insist that the ordinary people, that is, the people who enjoy popular songs and take, view, and exchange photographs, do not understand more daring, unusual innovations; yet, at the same time, he does not see himself as an entertainer or a propagandist, but as an artist whose innovations are compelled, first and foremost, by the desire to bring common people to a direct understanding of art.

In this essay I have argued that War Primer and its photo-epigrams may be read not only as critiques of the ideologies of war, but also as methods for bringing viewers/readers to a direct engagement with the art of poetry. Photographs have been used to address the crisis of perception at the heart of modern poetry, a crisis that, as Benjamin would have it, may have been caused—or at least exacerbated—by photography itself. Brecht’s creations, then, in countering the poetic challenges of obscurity and inaccessibly through the method of coupling the poem with a visual referent, present us with one method for continuing to counter the further degradation of poetry in our own age of hyper-intensified visual proliferation.

It may be that, if we were to continue and participate in Brecht’s project, we would need to further develop and experiment with the photo-epigram by, for example, placing the poem before the image, as per my suggested readings of photo-epigrams 1 and 38 in this essay, or by perhaps utilising poetic forms other than the quatrain and visual media other than the press photograph. Either way, I believe there is much that can be learnt from Brecht’s fascinating invention for writers who wish to not only critique the ideologies and fetishisms of our ruling classes, but who also aspire to discover new ways for valuing and creating poetry against the alienating modes of cultural production that have seen to the art form’s atrophy and marginalisation in the modern era.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Benjamin, Walter. 1992. Illuminations. Edited by Hannah Arendt. Translated by Harry Zohn. London: Fontana. [Google Scholar]

- Brecht, Bertolt. 1968. Kriegsfibel. Berlin: Eulenspiegel Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Brecht, Bertolt. 1980. Against Georg Lukács. In Aesthetics and Politics. London: Verso. [Google Scholar]

- Buckley, Bernadette. 2018. The Politics of Photobooks: From Brecht’s War Primer (1955) to Broomberg & Chanarin’s War Primer 2 (2011). Humanities 7: 34. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, David. 2003. Brecht’s War Primer: The “Photo-Epigram” as Poor Monument. Afterimage 30: 8–9. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, Clement. 1941. Bertolt Brecht’s Poetry. Art-Agenda. Available online: https://www.art-agenda.com/features/234163/clement-greenberg-s-bertolt-brecht-s-poetry (accessed on 11 March 2019).

- Imbrigotta, Kristopher. 2010. History and the Challenge of Photography in Bertolt Brecht’s Kriegsfibel. Radical History Review 106: 27–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jameson, Fredric. 1998. Brecht and Method. London: Verso. [Google Scholar]

- Leeder, Karen. 1996. Breaking Boundaries: A New Generation of Poets in the GDR. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Long, J. J. 2008. Paratextual Profusion: Photography and Text in Bertolt Brecht’s War Primer. Poetics Today 29: 197–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, Karl. 1863. Theories of Surplus-Value; Marxist Internet Archive. Available online: https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1863/theories-surplus-value (accessed on 14 January 2018).

- Marx, Karl. 1951. Theories of Surplus Value. Translated by G. A. Bonner, and Emile Burns. London: Lawrence & Wishart. [Google Scholar]

- Marx, Karl. 1967. Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844. Translated by Martin Milligan. Moscow: Progress Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Marx, Karl. 1986. The Communist Manifesto. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Marx, Karl. 1993. Grundrisse: Foundations of the Critique of Political Economy. Translated by Martin Nicolaus. London: Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Squiers, Anthony. 2014. An Introduction to the Social and Political Philosophy of Bertolt Brecht: Revolution and Aesthetics. Amsterdam: Rodopi. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).