Abstract

This paper examines some of the many ways in which example early cut-ups from Minutes to Go recall canonical literary forms, revive the revolutionary destructive urgency of Dada aesthetics, as well as contribute to wider environmental concerns. How do unusual examples of radically experimental literature contribute to how people think about the environment? What can additional consideration of the cut-up manifesto Minutes to Go tell us about the relationship between culture and nature? This paper suggests that unstudied examples of cryptic cut-ups from Minutes to Go participate in cultural recycling through the Glorious Plagiarism of canonical texts, and what emerges from the Dada Compost Grinder is a trash aesthetic that highlights the voids of both consumer and material culture.

1. Introduction

One century ago, experimental negative aesthetics arose to counter the age of industrial chemical warfare, and today the alarming and mounting dangers of environmental change again force us to rethink the form and function of literature. Although they were not consciously aware of their deep entanglement with environmental issues, it is important that Dadaists anticipated ways that art responds to ecological problems including access to limited resources and human overpopulation.1 One hundred years after Dada, countless environmental pressures confront humanity, and serious questions remain. Can the humanities really contribute to current environmental debates? Can scholarly activities assist in reconciling the many aesthetic and ethical questions that environmental change demands? Ecocriticism is one academic approach within the broader environmental humanities that examines cultural texts such as literature or film in the context of contemporary environmental concerns. Scholars working in the environmental humanities have done significant groundwork in this area, but existing scholarship is uneven. Scholars need to examine entire bodies of cultural texts, and since the environmental challenges ahead are so great, their involvement is urgent. The lack of green perspectives on experimental and avant-garde literature also demands attention. For example, early cut-ups from Minutes to Go recall canonical literary forms, revive the revolutionary destructive urgency of Dada aesthetics, as well as contribute to wider environmental concerns. Thus, one hundred years later, “Dada still speaks to us” (Forcer 2013, p. 272).

Experimental writing challenges literary tradition in order to innovate and demands much more attention in the context of increasing global environmental awareness. In recent years, scholars have begun to discuss the ways avant-garde aesthetics contributes to environmental discourse. Tarlo (2009) reminds us that few ecocritics study avant-garde writing. Bellarsi (2009) and Botar and Wünsche (2011) highlight the need to research green ethics in different experimental practices. Canadian scholar Rasula (2002) is far more bold and even goes so far as to propose that wild avant-garde practices might contribute to “biodegradable thinking”, which essentially suggests that literature can work towards the wider development of collective environmental consciousness.2 However, these voices are marginal and generally remain on the fringes of ecocritical studies. A fascinating consideration is whether creative endeavors might function as a form of environmental praxis as Lawrence Buell imagines (Buell 1995). Following the thinking of Rasula and Buell, the study of experimental forms might offer new ways of understanding our relationship with the environment, the space that surrounds us. Thus, the lack of ecological perspectives on experimental texts and the need for further study seems clear enough. I also think that a sustained examination of transnational experimental literature in an ecological framework can lead to new perspectives on the form and function of culture and provide new perspectives on the Beats. Against this background, this paper takes a step forward through a dialogue with unfamiliar avant-garde literature and the environment, and more specifically discussion of a strange composite text from the mid-twentieth century that recalls and honors Dada and yet strangely enough anticipates the age of environmental and ontological crises. The environment has long served as a source of inspiration for writers, and the critical literature widely recognizes this fact. However, this paper approaches culture from a more counterintuitive conceptual and theoretical position. How do unusual examples of radically experimental literature contribute to how people think about the environment? What can additional consideration of the cut-up manifesto Minutes to Go tell us about the relationship between culture and nature? There are, however, obvious snags.

The difficulties of attempting green readings outside of the nature-writing genre necessitate brief attention. Ecocriticism developed in successive stages; all phases remain active today, but challenges to the movement remain. In the United States, early ecocritical studies explored thematic issues in traditional forms of nature writing, for example, on canonical American cultural texts by Thoreau and Emerson.3 The second phase appeared around 2000. Lawrence Buell highlights the importance of environmental justice issues to this phase in the movement (Buell 2005), while Greg Garrard stresses the importance of critical self-reflection and the need for a willingness among scholars and thinkers to question common assumptions about the goals of ecocriticism (Garrard 2007). While Garrard proposes an ecocriticism that is deeply aware of human subjectivity and ideological bias, Joni Adamson and Scott Slovic stress the need for research to focus more on comparative and transnational connections between culture and the environment, which implies a more activist approach (Adamson and Slovic 2009). Developments that are more recent include a consideration of the Anthropocene and other framing models such as the Chthulucene (Haraway 2016). Essentially, ecocriticism examines art across cultures to uncover patterns and develop theoretical and practical solutions to the many questions surrounding environmental issues, in the spirit of environmental praxis. Therefore, literary texts are a particularly ripe space for environmental dialogue “according to their capacity to articulate ecological contexts” (Oppermann 2006, p. 111). The practice of ecocriticism here “operates from the premises of mimetic theories of literature (ibid.)” and in the case of Minutes to Go, the results are incredibly inventive forms of both mimicry and imitation. A literary text that displays repeated images of disease, flooding, and pollution might make readers uncomfortable in this textual world, and by confrontation with fictional frightening ecological scenarios through the didactic function of literature in this imaginary space, readers might begin to envision alternative paths to social and cultural recovery in the real world. In a wide sense, the environmental humanities “assume[s] that modes of social belonging and participation are mediated by cultural representations and interpretations of them” (Braidotti et al. 2013, p. 507). The scientific relevance of ecocriticism in this case is instructive. While ecocriticism is influencing literary studies, it faces challenges. One valid critique is that ecocriticism remains largely an academic exercise and has not been fully connected to the wider public discourse nearly enough to mark a true shift in consciousness. What is needed then is a transnational ecocriticism that builds on the theoretical strengths of European scholarship while connecting to and maintaining the social engagement and praxis of left-of-center American practitioners. While ecocriticism may seem most capable of dealing with texts with obvious environmental content such as texts that handle thematic representation of the natural world including plants, animals, and the many related ethical and philosophical questions, when pushed further it becomes blocked, nearly. On the surface, ecocriticism seems less suited to illuminating experimental writing forms that have little obvious environmental content or even relevance. As such, this paper challenges common trends within ecocriticism by addressing experimental literature in a transnational environmental context, focusing principally on experimental literature and more specifically the peculiar and early cut-up experiments found in Minutes to Go.

Minutes to Go (1959) is a brilliant cut-up manifesto and features a number of early, diminutive cut-up poems by Sinclair Beiles, William Burroughs, Gregory Corso, and Brion Gysin.4 One of the goals of the cut-up experiments seems to be to liberate linguistic discourse by stripping away context, thus revealing new ways of producing and reading culture. Robin Lydenberg sees links between the Burroughsian cut-up and its Dada precedents and highlights the negativity of the practice as a “kind of Dadaist destruction” (Lydenberg 1987, p. 48). Therefore, if we can accept that the cut-up links to Dada, then the implications for the Beat experiments with the cut-up form are significant. In the opening pages of Minutes to Go, Gysin echoes Tristan Tzara’s early groundbreaking call one century ago to destroy the culture of destruction through violent ideological and aesthetic revolt. In Minutes to Go, Gysin openly declares: “Pick a book … any book … cut it up” (Beiles et al. 1960, p. 4) and “here is the system … according to us” (ibid., p. 5). Links to the historical avant-garde are evident in both procedural aspects of the cut-up technique, which differ to varying degrees but preserve the desperate ideological fervor and urgency of Dada (and also Surrealism). Oliver Harris asserts that the “Exquisite Corpse required the participation of other practitioners”, but that the cut-up is far more flexible and needs only “a sheet of typed paper and a pair of scissors” (Harris 2009, p. 90). He further stresses the significance of the anti-aesthetic nature of the Exquisite Corpse system but insists that Burroughs was far more serious in the application of the cut-up and actually envisioned that people would employ the method at all levels of society to disrupt dominant control systems on a wide scale. What is clear is that the historical avant-garde functioned as a lightning rod for the Gysin-inspired cut-up and subsequent colossal book-length cut-ups written by Burroughs. Gregory Stephenson notes intriguing connections between the most experimental Beat works and the writing of the historical avant-garde:

In the tradition of dadaism and surrealism, the Beat Generation cultivated extreme forms of artistic expression, employed radically experimental techniques, and broke the fetters of established taste, literary decorum, and legal censorship. Their ebullience and energy, high-spirits and wit, boisterousness and rambunctiousness, panache and zany humor are also reminiscent of the dadaists and surrealists; as is, too, their penchant for public provocation and outrage, for scandalous antics and controversy. And of course, in the manner of dadaism and surrealism, the Beat Generation vehemently rejected traditional and conventional modes of thought and expression and sought instead to discover and explore, to reconceive and revalue, to invent new forms, and to create new visions.(Stephenson 1990, p. 7)

William Burroughs and Brion Gysin sincerely believed they were bringing the groundbreaking aesthetic potential of montage and collage to literature that had already been at work in the visual arts for decades. If the Dada movement and Brion Gysin are correct, then maybe “[t]here are no real political solutions—only aesthetic responses to calamities. The very point of Dada is that we all lose. Therefore, if industrialized society offers only industrial-scale death, then perhaps Dada[-inspired] forms are one way out of our untenable social situation” (Weidner 2016, p. 69). The transformative impact of Burroughs’ cut-up method influenced wide aspects of postwar popular English-language culture ranging from David Bowie’s fragmentary and hypnotizing lyrics to the ephemeral flickering images of 1980s pop music videos on MTV and to the angst-filled cut-up lyrics of grunge guru Kurt Cobain. In other words, the impact of the cut-up was far-reaching. Moreover, given the distinctiveness of the primordial cut-up period as found in Minutes to Go in the context of the extended cut-up books that later follow, and given the reluctance of many Beat scholars to work with the cut-up generally and more specifically with Minutes to Go, more work on these miniature cut-ups is needed. I propose that unstudied examples of cryptic cut-ups from Minutes to Go participate in cultural recycling through the glorious plagiarism of canonical texts, and what emerges is a trash aesthetic that highlights the voids of both consumer and material culture. What follows, then, is consideration of three example cut-ups from Minutes to Go including Gregory Corso’s “MOVE THE BONE WORDS OF THE IMMORTAL BARD WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE”, William Burroughs and Gregory Corso’s “EVERYWHERE MARCH YOUR HEAD”, and Brion Gysin’s “CALLING ALL REACTIVE AGENTS”.

2. Reanimating the English Canon: “MOVE THE BONE WORDS OF THE IMMORTAL BARD WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE”

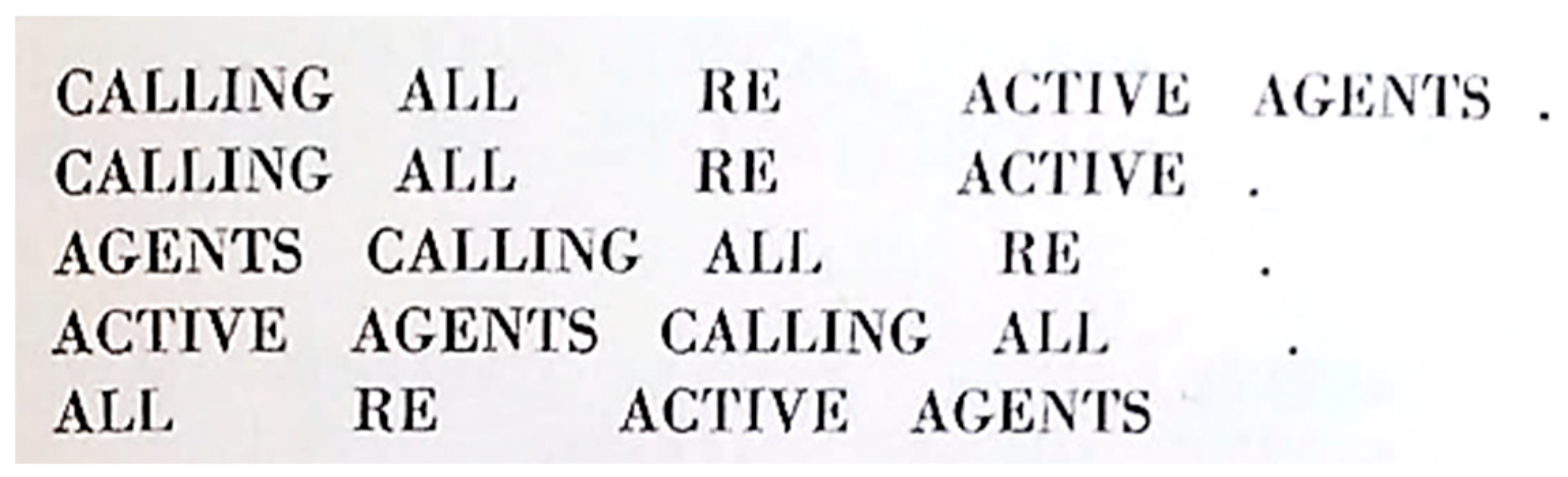

The initial piece for discussion here is Gregory Corso’s cut-up “MOVE THE BONE WORDS OF THE IMMORTAL BARD WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE”. Intriguing is the fact that Corso was a reluctant participant in the larger cut-up project. He renounced the project in the closing pages of Minutes to Go and cautioned: “Word poetry is for everyman, but soul poetry—alas, is not heavily distributed” (Beiles et al. 1960, p. 63). He also asserted that the cut-up essentially engineers lifeless and “uninspired machine-poetry” (ibid.). However, considering the variety of the different cut-ups that exist in Minutes to Go in the context of the selection of source texts and the differing procedural variations, Corso’s early cut-ups are clearly distinctive. It seems that Corso’s experiments in particular recall canonical texts most convincingly than others published in Minutes to Go. For example, “FRAGMENT P.B. Shelley” recalls Percy Shelley’s “Lines”, which was published after Shelley’s death in 1824. Inspection suggests that Corso utilized great care in the composition of the recycled and recomposed cut-up text, which resulted in a piece that is nearly identical to the source text, though the punctuation deviates considerably from the original. One important methodological difference between Corso’s cut-ups and the others presented in Minutes to Go involves the selection of source texts. Gysin and Burroughs often chose popular contemporary texts such as Time Magazine and the Herald Tribune as source material for later deconstruction and recomposition. The selection of source texts is interesting here since the selection process interrupted and subverted linguistic discourse. It is also intriguing that Corso seemed to look retroactively for inspiration while Burroughs and Gysin drew more heavily on popular publications and other accessible texts. Corso dug up canonical texts as source material for his cut-up research. In one instance, Corso selected a canonical source (Shakespeare) and subsequently cannibalized the source text for re-representation in the final cut-up form in the strange cut-up “MOVE THE BONE WORDS OF THE IMMORTAL BARD WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE”. The cut-up opens with a twist on Shakespeare’s own words, which certainly sound familiar:5

(Beiles et al. 1960, p. 61)

Straightway the odd reversed quotation marks that are usually used when ending and not beginning a quotation confront the reader. Thus, this particular cut-up immediately suggests that things may not be as they might at first seem. Further reflection suggests that this line can be read as a posthumous declaration of sorts, an homage to Shakespeare’s words projected far into a distant future. A straightforward reading and interpretation of cut-ups is difficult. This is especially true when considering the long extended Nova trilogy Burroughs later produced that challenged the very idea of what a narrative is and what it is supposed to do. Important here is that the form of the cut-up is the principle literary strategy. In other words, the anti-aesthetic ideology of the cut-up is an essential and predominant feature, which too recalls Dada. While a generic reading of cut-ups is a challenge, searching for fragments of meaning can be more productive. What also becomes interesting here are other lines in the cut-up. Consider the following textual extract that contains block letters: “TO. THE. ONLIE. BEGETTER. OF./THESE. INSUING. SONNETS” (Beiles et al. 1960, p. 61). This line suggests an effort to attract the reader’s focused attention or to convey a message of great importance and urgency. The speaker seems to be addressing the reader directly, though it remains unclear whether the speaker is Shakespeare, Corso, both, or someone else entirely. One of the more intriguing features of the cut-up broadly is the great difficulty in identifying narrative voice. In other words, the speaker is never really known. In this way too, the cut-ups recall the linguistic playfulness and destabilization of language essential to Dada. Authorship always seems up in the air, open to debate, and unclear, which is disorienting and puzzling to the reader. While participatory reading requires mental energy from the reader, one message is clear enough: Listen all future readers, as I bear a message of great importance. The subsequent lines mention both “HAPPINESSE./AND THAT ETERNITIE”. While not specifically environmental in theme, there is a subtle suggestion that is venerated in mainstream environmentalism that suggests the ongoing development of global ecological consciousness demands ample amounts of optimism and hope. This is confirmed in the subsequent lines, “THE. WELL-WISHING./ADVENTURE. IN./SETTING/FORTH” (ibid.). These lines can be taken as suggesting a plea for good fortune in subsequent endeavors. What is also interesting here is the punctuation, which also violates normative grammatical rules. We can speculate that the periods indicate potential breaks in the text, which suggests a deeply intricate recomposition process. Deviant punctuation is also found in Corso’s cut-up of Shelley, which I think reveals a degree of glorious plagiarism that is not as clearly seen in the other cut-ups in Minutes to Go. Glorious plagiarism can be described as an amplified form of homage. Lydenberg emphasizes that to Burroughs, “a cut-up of even the most familiar text will literally reincarnate the voice and creative imagination of the writer: ‘Shakespeare, Rimbaud live in their words’” (Lydenberg 1987, p. 49). My contention is that the recycling of the source text and subsequent feeding of the subverted text to the reader in an altered form amplifies the canonical source. The great care in the procedural recomposition, to produce replicas turned, is unusual in the context of the wider cut-up project. Thus, in some ways Corso’s cut-ups are quite distinctive even within the context of the cut-ups presented in the Minutes to Go manifesto. An intriguing consideration is whether Corso’s experiments involved not only procedural differences from the cut-ups as designed by Gysin and Burroughs but whether the purpose of the experiment was different too.

Given Corso’s personal fascination with canonical texts, his efforts can rightfully be said to resurrect, to a large degree, the canonical legacies of the original texts. Therefore, what essentially Corso accomplishes with “MOVE THE BONE WORDS OF THE IMMORTAL BARD WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE” is twofold. The act of cultural cannibalism can be seen as both an effort to destabilize literary convention while at the same time reinscribing the canonical power of Shakespeare. Paradoxically, the text functions as an act of homage and glorious plagiarism and at the same time encourages writers to reinvent the process of literary creation by re-envisioning the canon. If we do indeed live in the age of intractable climate change, then rethinking how to make art and what constitutes literature precisely may be part of the greater movement towards ultimate cultural recovery. This is why conjuring the ghost of Shakespeare is so essential to this particular cut-up, since in the context of English-language literary culture, everything begins with Shakespeare.

3. Remaking Rimbaud: “EVERYWHERE MARCH YOUR HEAD”

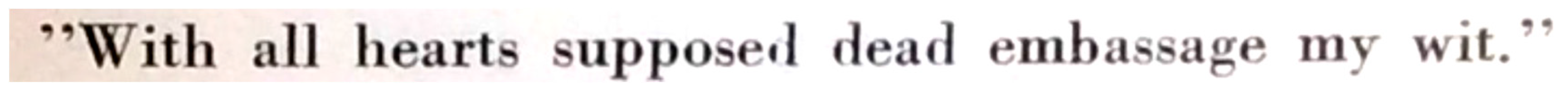

While cut-ups from Minutes to Go remain generally understudied in the context of Beat scholarship, current research traces the intriguing linguistic connections between Rimbaud and the earliest Beat cut-up experiments. Veronique Lane deliberates what she sees as the systematic appropriation of French-language modern literature “from Rimbaud to Michaux” by members of the Beat Generation. She asserts, boldly, that the Beats borrowed heavily from French literature and culture (Lane 2017). Lane argues that the common assumption that Dada and Surrealism exclusively (or mostly) inspired the cut-ups is incorrect. She thinks that the cut-ups in Minutes to Go are in fact richly connected to French texts. Lane might overestimate the linguistic dexterity of the Beats a bit here. Apart from Jack Kerouac and Gary Snyder to a lesser extent, the Beats were not particularly polyglot. Burroughs wrote brief asides in German and Spanish throughout his work but not much in French. Ginsberg seems to have been even more monolingual even if he did develop a genuine fascination with other cultures. Although it would seem that the Beats were acutely aware of French literary developments, they were at the same time bound by the English language medium for the most part. This point is more tentative, and I recognize the potential of further studies to push into further linguistic links between the Beats and other languages, and not just European languages. In any case, Lane is correct that the Beats were inspired by French literature, absolutely. Most interesting for the purposes of this paper are the ways Lane traces the translation of the source Rimbaud text and the many problems and linguistic difficulties that accompany such an effort. At one point, Lane discusses the cut-up “EVERYWHERE MARCH YOUR HEAD”, and argues, amongst other things, that while “EVERYWHERE MARCH YOUR HEAD” is presented as being jointly authored by Burroughs and Corso, she stresses that Burroughs had the leading authorship role for this particular cut-up (ibid., p. 37), and she builds a case on textual evidence. Recent critical attention to “EVERYWHERE MARCH YOUR HEAD” is welcome and emphasizes the richness of Minutes to Go to the expanding circle of Beat studies that is continuing. Lane discusses the imaginative translation of the source text “À une Raison” to the reincarnations “EVERYWHERE MARCH YOUR HEAD” and “Cut up Rimbaud’s TO a REASON”. Lane’s suggestion that the combinations of ethical and aesthetic endeavors are key to appreciating the Beats are particularly thought provoking, and I think connects directly to environmental dialogue. Ecocriticism is primarily interested in questions of philosophy and interpretation in the context of contemporary environmental concerns, so this is where overlap takes place (see also Weidner et al. (2019)). In other words, one cannot fully separate ethical and aesthetic considerations, and the tension and overlap between culture and nature are actually very interesting sources for reflection on contemporary environmental discourse. Consider the following textual fragment, which provides remnants of environmental meaning and yet recalls the canonical power of Rimbaud in another example of glorious plagiarism:

(Beiles et al. 1960, p. 23)

Attempting a green reading of “EVERYWHERE MARCH YOUR HEAD” creates an instantaneous barrier to interpretation, although the ideology behind the creative act connects to environmental discourse. Lane discusses the difficulties in attempting an initial reading of this cut-up, citing incomprehensibility (Lane 2017, p. 38). There simply does not seem to be very much to hold onto here. The title of the cut-up poem is followed by an odd open double quotation mark, which suggests incompleteness and confirms the general trend of cut-ups to play with and subvert the functions of punctuation and grammatical language. This also suggests that the cut-ups were composed with great care and were not nearly as spontaneous and immediate as the myth of the cut-up might otherwise suggest. Burroughs was contradictory on this point and proclaimed that the text of Minutes to Go included “unedited unchanged cut-ups” (Burroughs and Gysin 1978). However, the writer elsewhere admitted that in fact a great degree of composition was essential to the cut-up practice: “One tries not to impose story plot … but you do have to compose the materials, you can’t just dump down a jumble of notes and thoughts and considerations and expect people to read it” (Odier 1989, p. 48). David Sterritt also holds that Burroughs’ apparent “cut-up spontaneity was not based on random or haphazard juxtaposition, since after cutting or folding a text … he would rewrite the result until it carried some degree of identifiable sense” (Sterritt 2000, p. 167). However, attempting a straightforward literary analysis of the lines “Everywhere/march/your/head” is truly puzzling. There does not seem to be any coherence nor does there seem to be any recognizable sense.

Ecocriticism is challenged in doing a thematic reading of “EVERYWHERE MARCH YOUR HEAD”, but the ideology behind the form can help us understand the ways in which experimental literature contributes to how people think about the environment. Generic reading grids that emphasize biographical concerns and attention to overarching matters of theme and plot do not function well here. Instead, if one considers the significance of the new form that emerges from the vigorous use of the found text, it can be said that the cut-up forces us to question, radically, what is suitable material for environmental reflection. Furthermore, the simultaneous destabilization of literature through the veneration and sabotage of Rimbaud forces the reader to pose tricky questions about authorship and agency. Bellarsi and Rauscher emphasize the “Entangled Reconfiguring of Authorship” of ecopoetic texts as essential considerations in understanding avant-garde literature (Bellarsi and Rauscher 2019, p. 8). Rimbaud’s position in the avant-garde canon is assured, and the attempt to appropriate his work in the combustible cut-up form is important. The consequences of selecting Rimbaud source texts are on the one hand a form of homage. At the same time, the cut-up technique processes the source text and spits it out at the reader in a modified and subversive form. This is where homage is amplified into an act of glorious plagiarism, the odd condition of simultaneous homage and sabotage. If we look at language as an instrument of higher understanding, then literature may provide humans with a vehicle to begin to comprehend our existence on this planet. As Bellarsi and Rauscher remind us, ecopoetic endeavours do not just summon the pastoral or involve only ecopoetry, but the other spaces to work through our larger concerns. They emphasize,

without necessarily turning its back on literature and writing, [ecoppoetics] goes “beyond the page” and refers to a broad array of artistic, activist, and performative practices (including but also going beyond poetry) that examine the non-human world, human-world relations, and the conditions, possibilities, and limits of the knowledges, ethics, and politics such examinations may produce.(ibid., p. 3)

If we think of the text as a screen to work through the limits of human knowledge as well as the many corresponding ethical and political concerns, the “urns” mentioned in “EVERYWHERE MARCH YOUR HEAD” are not necessarily another example of haphazard linguistic play at all but instead point to more existential anxieties that slip out of the recomposed text. This slippage is found in the cut-ups more broadly, as well as the most significant works of the Beat Generation. In other words, any cultural space that allows the writer or reader to work through the limits of current human knowledge or force us to question common assumptions about the way things are or how they might be is essentially ecopoetic at the level of conception.

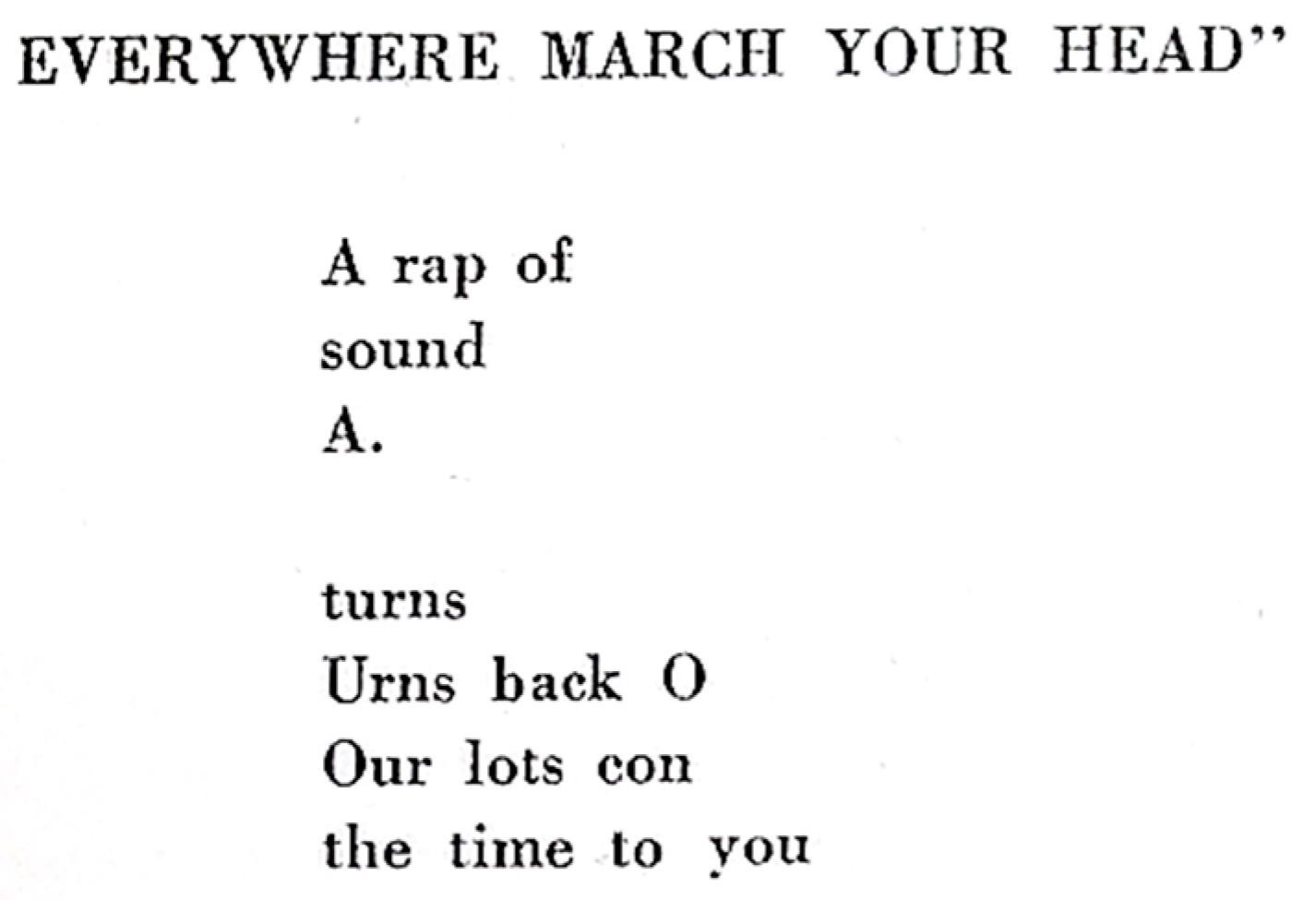

4. A Dada Call to Action: “CALLING ALL REACTIVE AGENTS”

(Beiles et al. 1960, p. 29)

Brion Gysin’s “CALLING ALL REACTIVE AGENTS” also confronts ecocriticism with theoretical limits. At first glance, one notices a process of degradation in the fragment, of language being reduced to simpler forms. Lines collapse, gradually, over a number of lines. At the same time, words are repeated and the result nearly functions as a flickering incantation. “CALLING” and “AGENTS” are recurrent. At first, it might seem that when faced with some of the most cryptic cut-ups such as “CALLING ALL REACTIVE AGENTS”, ecocritical reading grids find great difficulty in handling fragmented literary forms, especially given the absence of clearly relevant environmentally thematic material. However, Gammel and Wrighton suggest that a Dada theory of trash aesthetics works to radically dismantle nature/city boundaries and thus creates a multisensorial immersive perspective that is essentially antipastoral and in the end produces a “radical ecopoetic liminality” (Gammel and Wrighton 2013, p. 4). They assert that “[e]copoetry is looking for its literary history. In its form, instead of an over-reliance on a Wordsworthian Romantic (and male) tradition, it can look to the Dada expressions as pioneering practice of a radical ecopoetics” (ibid., p. 17). Therefore, it can be said that the cut-up essentially functions as an anti-pastoral Dada Compost Grinder, and alternative to ecopoetry.

Certainly, “CALLING ALL REACTIVE AGENTS” resounds with Dada inspiration and resolve and thus by extension can be called ecopoetic at the conceptual level. As Gammel and Wrighton remind us, “Within the ecology of recycling and sustainability, language itself is a cultural litter to be recycled and renewed, while culture as a rich compost for poetry is subject to the ecological laws of decomposition and recomposition” (Gammel and Wrighton 2013, p. 10). One of the key aspects of found text practices is generally the idea that language can be reassembled from the cultural scraps of history. The reverberation of the cut-up back to Dada is also clear in “CALLING ALL REACTIVE AGENTS” in a message to engage the reader in direct forms of Dada-aesthetic guerilla action and revolt.6 The lines repeat a wide message of warning through the strategic employment of culture jamming and guerrilla semiotics (Tietchen 2001). Such a call to engage in violent aesthetic action echoes not just Dada but the more radical elements of the environmental movement such as the Deep Green Resistance movement, which advocates an uprising against capitalist infrastructure, compliant corporations, and corrupt governments in the worldwide struggle for what McBay, Keith and Jensen believe is survival.7 This idea of remaking society is repeated throughout William Burroughs’ wider body of work and especially the later Cities trilogy. There are limits to the Deep Green Resistance movement. The practical problems of implementing such a violent revolution make the goal unpalatable or even borderline evil, but what is important here is the common call to action in defense of our common humanity. After all, Burroughs and the other Beats also lived in the Anthropocene; that is, the age of the human.8 Therefore, it is not surprising to see primary Beat texts deal with the same essential questions, at least abstractly, that only in recent years have become so clearly ingrained in our everyday thinking.

“CALLING ALL REACTIVE AGENTS” ultimately participates in what can be called ecological entropy, the gradual grinding down of order into disorder, and of language into the cut-up, thus mimicking natural processes. We now know that mutations occur randomly, and that nature is far less predictable than we might at first imagine. Ecological entropy is essentially the negative response within organic systems towards breaking down into chaos (Frautschi 1982). In this way, the cut-up mimics natural processes in the gradual breakdown of language into fragments. Bellarsi and Rauscher argue: “Ecopoetic practice exceeds poetry [and] forms an attempt to map the shifting area where randomness and design spill into [each other,] whether this intermingling be voluntary or suffered” (Bellarsi and Rauscher 2019, p. 10). If Bellarsi and Rauscher are correct, then the ecological effect of cut-ups such as “CALLING ALL REACTIVE AGENTS” involves both the randomness and the design of the cut-up procedure itself, which deconstructs language and strips discourse of place and context (Bellarsi 1997, pp. 45–56). At the same time, again, what can be found is homage to the revolutionary destructive urgency of a wider Dada aesthetic. It is also interesting that the selection of the source texts and the subsequent reconstitution can be seen as attempts to subvert the cut-up practice itself.

5. Conclusions

The cut-ups in Minutes to Go participate in an ongoing, if hidden, dialogue between literature and intriguing environmental questions. The cut-up technique functions as a Dada Compost Grinder, and the process provides rich material for ecopoetic consideration. The leading principle behind the Gysin-inspired cut-up is the Dada Compost Grinder. Essentially, the cut-up process cannibalizes culture and at the same time destabilizes linguistic discourse. While ecocriticism tends to think of certain approaches to texts, anthropologists show us that the remnants of culture, that is to say trash, are also incredibly valuable forms of cultural stuff and tell us a lot about the limits of material culture. Therefore, artistic forms that utilize a trash aesthetic pay homage not only to the international historical avant-garde, but also to Tzara and Dada and Ball and many others, to Surrealism and Dali, Picasso, and Duchamp. The Cut-ups contained in Minutes to Go depend on and promote a “trash aesthetic as rich compost for creative rebirth that goes beyond human agency” (Weidner 2016, p. 160). The consequences are very interesting and suggest that experimental writing techniques can function as radical techniques of transformation. At the same time, the cut-up assists in cultural recovery by utilizing Dada-inspired methods. Moreover, the cryptic early cut-ups of Minutes to Go participate in the glorious plagiarism of older texts, some of which are canonical, and some of which are Dada-inspired. The act attempts to construct a new culture distant from the unsustainable present through the reassembly of texts. The cut-up remains subversive, and such writing amounts to trash aesthetics that is both self-reflective and anticipatory. What can be found in early cut-ups is more than the total recall of canonical literary forms. At the same time, they revive the revolutionary Dada aesthetic and acknowledge wider environmental concerns.

What emerges from the Dada Compost Grinder is a trash aesthetic that highlights the voids of consumer and material culture. The original context of the source texts is stripped clean, and the reanimated fragments are fed back to the receiver in a strange, amended form. The revolutionary Dada aesthetic, which is cut up into the cut-up, maintains and amplifies the destructive urgency of Dada. The early cut-ups are so interesting even within the Beat canon because of the difficulties of authorship and readership. Gary Snyder once proclaimed “[p]oetry as ecological survival technique” (Snyder 1969, p. 117). A fascinating consideration is to what extent other fragmentary and fringe aesthetic forms might function as a method of ecological survival through the didactic and mimetic functions of literature. In this way, the Beat project can be enriched by further green readings (See also (Phillips 2000; Skinner 2018)). At the same time, the ever-expanding loop of ecocriticism can benefit by further consideration of Beat and Bohemian cultures. Finally, it can be said that the initial deeply creative cut-up experiments in Minutes to Go expose increasing human isolation in an age of environmental disorder. The dismantling and reassembly of language through the cut-up process allows space for potential cultural salvation by reimagining the human situation and our relationship with the art and the world.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Adamson, Joni, and Scott Slovic. 2009. The Shoulders We Stand On: An Introduction to Ethnicity and Ecocriticism. MELUS 34: 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beiles, Sinclair, William Burroughs, Gregory Corso, and Brion Gysin. 1960. Minutes to Go. Paris: Two Cities Editions. [Google Scholar]

- Bellarsi, Franca. 1997. William S. Burroughs’s Art; the Search for a Language That Counters Power. In Voices of Power: Co-Operation and Conflict in English Language and Literatures. Edited by Marc Maufort and Jean Pierre van Noppen. Liege: Belgian Association of Anglicists in Higher Education, pp. 45–56. [Google Scholar]

- Bellarsi, Franca. 2009. Eleven Windows into Post-Pastoral Exploration. Journal of Ecocriticism 1: 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Bellarsi, Franca, and Judith Rauscher. 2019. Toward an Ecopoetics of Randomness and Design. Ecozon@ 10: 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Bolton, Michael Sean. 2010. Get Off the Point: Deconstructing Context in the Novels of William S. Burroughs. Journal of Narrative Theory 40: 53–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botar, Oliver, and Isabel Wünsche. 2011. Biocentrism and Modernism. Surrey and Burlington: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Braidotti, Rosi, Kum Kum Bhavnani, Poul Holm, and Hsiung Ping-chen. 2013. The Humanities and Changing Global Environments. Paris: OECD Publishing/Unesco Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Buell, Lawrence. 1995. The Environmental Imagination: Thoreau, Nature Writing, and the Formation of American Culture. Cambridge: Belknap-Harvard UP. [Google Scholar]

- Buell, Lawrence. 2005. The Future of Environmental Criticism: Environmental Crisis and Literary Imagination. Malden: Blackwell Pub. [Google Scholar]

- Burroughs, William S., and Brion Gysin. 1978. The Third Mind. New York: Viking Press. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, Karen. 2005. Dead Channel Surfing: The Commonalities between Cyberpunk Literature and Industrial Music. Popular Music 24: 165–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forcer, Stephen. 2013. The Importance of Talking Nonsense: Tzara, Ideology, and Dada in the 21st Century. In Dada and Its Legacies. Edited by Elza Adamowicz and Eric Robertso. Amsterdam and New York: Rodopi, pp. 263–74. [Google Scholar]

- Frautschi, Steven. 1982. Entropy in an Expanding Universe. Science 217: 593–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gammel, Irene, and John Wrighton. 2013. ‘Arabesque Grotesque’: Toward a Theory of Dada Ecopoetics. Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and Environment 20: 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrard, Greg. 2007. Ecocriticism and Education for Sustainability. Pedagogy: Critical Approaches to Teaching Literature, Language, Composition, and Culture 7: 359–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, Terry. 2000. Pastoral, Anti-Pastoral, Post-Pastoral. In The Green Studies Reader: From Romanticism to Ecocriticism. Edited by Laurence Coupe. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 219–22. [Google Scholar]

- Grace, Nancy. 2004. Ruth Weiss’s Desert Journal: A Modern-Beat-Pomo Performance. In Reconstructing the Beats. Edited by Jennie Skerl. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 57–71. [Google Scholar]

- Haraway, Donna Jeanne. 2016. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Experimental Futures: Technological Lives, Scientific Arts, Anthropological Voices. Durham: Duke UP. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, Oliver. 1996. A Response to John Watters, ‘the Control Machine: Myth in the Soft Machine of W. S. Burroughs’. Connotations—A Journal for Critical Debate 6: 337–53. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, Oliver. 2004. ‘Burroughs Is a Poet Too, Really’: The Poetics of Minutes to Go. In Edinburgh Review. Edited by Ronald Turnbull. Edinburgh: Centre for the History of Ideas in Scotland, pp. 24–36. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, Oliver. 2009. Cutting up the Corpse. In The Exquisite Corpse: Chance and Collaboration in Surrealism’s Parlor Game. Edited by Kanta Kochhar-Lindgren, Davis Schneiderman and Tom Denlinger. Lincoln: U of Nebraska P, pp. 82–103. [Google Scholar]

- Lane, Veronique. 2017. The French Genealogy of the Beat Generation: Burroughs, Ginsberg and Kerouac’s Appropriations of Modern Literature, from Rimbaud to Michaux. New York: Bloomsbury Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Lydenberg, Robin. 1987. Word Cultures: Radical Theory and Practice in William S. Burroughs’ Fiction. Urbana: U of Illinois P. [Google Scholar]

- McBay, Aric, Lierre Keith, and Derrick Jensen. 2011. Deep Green Resistance: Strategy to Save the Planet. New York: Seven Stories Press. [Google Scholar]

- Odier, Daniel. 1989. The Job: Interviews with William S. Burroughs. New York: Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- Oppermann, Serpil. 2006. Theorizing Ecocriticism: Toward a Postmodern Ecocritical Practice. Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and Environment 13: 103–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlik, Joanna. 2013. Surrealism, Beat Literature and the San Francisco Renaissance. Literature Compass 10: 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, Rod. 2000. “Forest Beatniks” and “Urban Thoreaus”: Gary Snyder, Jack Kerouac, Lew Welch, and Michael Mcclure. Modern American Literature. New York: P. Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Rasula, Jed. 2002. This Compost: Ecological Imperatives in American Poetry. Athens: U of Georgia P. [Google Scholar]

- Rasula, Jed. 2014. Bringing in the Trash: The Cultural Ecology of Dada. Green Letters 18: 22–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rettberg, Scott. 2008. Dada Redux: Elements of Dadaist Practice in Contemporary Electronic Literature. In The Fibreculture Journal. London: Open Humanities Press. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, Edward S. 2011. Shift Linguals: Cut-up Narratives from William S. Burroughs to the Present. Postmodern Studies. Amsterdam and New York: Rodopi. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner, Jonathan. 2001. Why Ecopoetics? Ecopoetics 1: 105–6. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner, Jonathan. 2018. Visceral Ecopoetics in Charles Olson and Michael McClure: Proprioception, Biology, and the Writing Body. In Ecopoetics: Essays in the Field. Edited by Angela Hume and Gillian Osborne. Iowa City: U of Iowa P, pp. 65–83. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder, Gary. 1969. Earth House Hold; Technical Notes & Queries to Fellow Dharma Revolutionaries. A New Directions Book. New York: New Directions P. [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson, Gregory. 1990. The Daybreak Boys: Essays on the Literature of the Beat Generation. Carbondale: Southern Illinois UP. [Google Scholar]

- Sterritt, David. 2000. Revision, Prevision, and the Aura of Improvisatory Art. Journal of Aesthetics & Art Criticism 58: 163. [Google Scholar]

- Tarlo, Harriet. 2009. Recycles: The Eco-Ethical Poetics of Found Text in Contemporary Poetry. Journal of Ecocriticism 1: 114–30. [Google Scholar]

- Tietchen, Todd. 2001. Language out of Language: Excavating the Roots of Culture Jamming and Postmodern Activism from William S. Burroughs’ Nova Trilogy. Discourse 23: 107–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watters, John G. 1995. The Control Machine: Myth in the Soft Machine of W.S. Burroughs. Connotations—A Journal for Critical Debate 5: 284–303. [Google Scholar]

- Weidner, Chad. 2013. Mutable Forms: The Proto-Ecology of William Burroughs’ Early Cut-Ups. Comparative American Studies 11: 314–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidner, Chad. 2016. The Green Ghost: William Burroughs and the Ecological Mind. Carbondale: Southern Illinois UP. [Google Scholar]

- Weidner, Chad, Rosi Braidotti, and Goda Klumbyte. 2019. The Emergent Environmental Humanities: Engineering the Social Imaginary. Connotations—A Journal for Critical Debate 28: 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Zurbrugg, Nicholas. 1979. Dada and the Poetry of the Contemporary Avant-Garde. Journal of European Studies 9: 121–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | For a discussion of the connections between Dada and environmental criticism, see Gammel and Wrighton (2013). |

| 2 | Here, the ghost of Dada tells us that radically rethinking the form and function of art counters dominant cultures of destruction. It can be said that the Dada corrective functions essentially as an anti-pastoral form of environmental thinking. See also Gifford (2000). |

| 3 | Transcendentalism was a common source of inspiration for both early American ecocritics as well as the writers of the Beat Generation. |

| 4 | Existing scholarship establishes the connections between Dada and the cut-up strategy. See Zurbrugg (1979); Lydenberg (1987); Stephenson (1990); Watters (1995); Harris (1996, 2004); Tietchen (2001); Grace (2004); Collins (2005); Rettberg (2008); Bolton (2010); Robinson (2011); Pawlik (2013); Weidner (2013); Rasula (2014). See also Skinner (2001). |

| 5 | Because of the deviant spacing, punctuation, and formatting of the Minutes to Go cut-ups under discussion here, photos of textual fragments are occasionally used. |

| 6 | William Burroughs believed that ideological goals can be met through writing and protest. When once asked about the growing youth movement and the protests in the 1960s, Burroughs exclaimed his support for direct action, “There should be more riots and more violence. Young people in the West have been lied to, sold out, and betrayed. Best thing they can do is take the place apart before they are destroyed in a nuclear war. Nuclear war is inevitable if the present controllers remain in power” (qtd. in (Odier 1989, p. 81)). |

| 7 | See McBay et al. (2011). They argue that society will never voluntarily transform itself into a sustainable civilization; therefore, according to them, the time is right for people to contribute to a worldwide insurgency voluntarily, in defense of the environment. |

| 8 | The Anthropocene is a recent word that suggests that humans created a new geological age that began during the Industrial Revolution, a time when humans began introducing significant amounts of carbon into the atmosphere. |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).