Abstract

Motivated by “the need to embody … the palpable tension between the North and the South as it is reflected, articulated, and interpreted in contemporary cultural production”, documenta 14’s selection of Athens as a “vantage point … where Europe, Africa, the Middle East, and Asia face each other” is in line with the ancient Greek concept of the ‘cosmopolite’, a term that Diogenes first coined “as a means of overcoming the usual dualism Hellene/Barbarian”. In this article, I suggest that Naeem Mohaiemen’s feature film, Tripoli Cancelled (2017), commissioned by documenta 14 and premiered at the National Contemporary Art Museum in Athens, proposes a rich and compelling model of cosmopolitan world-making. Shot at the abandoned Elliniko Airport, the film is poetically suspended between fact and fiction, past and present, the historical and the incidental, the local and the global. Creatively positioning the concepts of cosmopolitanism, nostalgia, and hospitality in dialogue, I develop a theoretical model through which I seek to explore how the literally and metaphorically liminal space inhabited by the film’s anonymous protagonist resonates with the contemporary conditions of desperate migration.

1. Introduction: Toward a Cosmopolitan Model of World-Making or Documenta 14 Goes to Athens

“We often imagine our place in the world—or others imagine it for us—via loaded directionals like North and South, East and West,” documenta 14 artistic director Adam Szymczyk and his collaborator Quinn Latimer observed in the editorial of the exhibition’s first collateral journal issue (Documenta 14 2015). While binary models like those of center/periphery or North/South may have their strategic advantages in the rhetorical realm as counterhegemonic tools of antiimperialist resistance, they are also characterized by a rigidity that often does not allow for the accommodation of the lived complexities and contradictions that permeate the material world. Within this framework, the curatorial program of documenta 14 might be seen as a welcome corrective. Motivated by “the need to embody … the palpable tension between the North and the South as it is reflected, articulated, and interpreted in contemporary cultural production”, the selection of Athens as a “vantage point … where Europe, Africa, the Middle East, and Asia face each other” (Documenta 14 2014) is in line with the concept of the ‘cosmopolite’, a term that Diogenes first coined “as a means of overcoming the usual dualism Hellene/Barbarian” (Koundoura 2007, p. 10). Maria Koundoura likewise proposes a nuanced politics of place that diverges both from the dominant understanding of Greece as a “historically tested utopianism” and from the resistant understanding of Greece as the point of departure of our “currently most despised vices: sexism, racism, colonialism, imperialism, metaphysics, and the verb ‘to be’” (Koundoura 2007, p. 3):

Indeed, such a notion of place as contact zone or porous interface for transcultural contact and exchange is historically consistent with Greek ideals—both in terms of its geographical territory, which has been subject to various configurations of sovereignty throughout its history, and in terms of its transnationally oriented people(s).Whether one reads [Greece] as the origin or uses it to argue the end of Western culture, locates it at the center of the critical discourse on historical modernity and its epistemological structures, or points to it as an experiment on the margins, it remains the axis around which a number of modernity’s workings of subject formation are staged: Oriental/European, ancient/modern, civilized/barbaric, metropolitan/peripheral, dominant/diverse.(Koundoura 2007, pp. 7–8)

It is my contention that contemporary artistic production is uniquely poised to help us position Greece in what Nikos Papastergiadis calls the “cosmopolitan imaginary”. Departing from Cornelius Castoriadis’s claim that “the act of the imagination is the principal means for facing both the abyss of the being and the eternity of the cosmos”, Papastergiadis posits that “the cosmopolitan images of conviviality arise not only from a moral imperative but also from an aesthetic interest in others and difference. The most vivid signs of the aesthetic dimension of the cosmopolitan imaginary can be found in the world-making process of contemporary art” (Papastergiadis 2012, p. 90). In what follows, I propose Naeem Mohaiemen’s feature film, Tripoli Cancelled (2017), commissioned by documenta 14 and premiered at the National Contemporary Art Museum in Athens, as a rich and compelling model of cosmopolitan world-making. I suggest, moreover, that the cosmopolitan world envisioned by Mohaiemen and enacted by Tripoli Cancelled is characterized by the complication of time, space, and identity, the punctuation of the historical with the incidental, the global with the local, and vice versa. From my analysis of Tripoli Cancelled, three key conceptual axes emerge: the suspension of time, the expansion of space, and the entanglement of identity.

2. As You Set Out on the Way to Tripoli, Hope That the Road Is a Long One—A Journey in Four (Plus Four) Vignettes

Shot at the abandoned Elliniko Airport, Naeem Mohaiemen’s Tripoli Cancelled performs a poetic balancing act between fact and fiction, local and global, past and present. In an aesthetic that combines seductive cinematography and a surreal plotline punctuated by contrasting instances of the quotidian, the lyrical, the critical, and the humorous, the film portrays a week in the life of a man who has been living for a decade in an abandoned airport. The camera follows the anonymous protagonist, embodied by Vassilis Koukalani, as he navigates the decaying modernist structure, struggling to hold onto his intellectual lucidity. The sharp, wide-angle cinematography of Petros Nousias creates an immersive environment that heightens the feeling of intimacy kindled by Koukalani’s haunting performance. Inflected by the protagonist’s exilic condition of loneliness and the airport’s state of ruin, the vignettes of otherwise mundane actions take on a rather absurd quality.

In the opening scene, the protagonist engages in the routine ritual of shaving, typically marking the dawn of a new day, but, in this context, the beginning of the narrative as well. Instead of a bathroom mirror, however, he gazes pensively into the camera. In another vignette, the protagonist sits in a folding chair in the middle of the tarmac, reading out loud passages from the 1972 British adventure novel, Watership Down, while brewing coffee on a portable gas burner (Figure 1). Elsewhere, the protagonist boogies to The Melodians’ 1970 song, “Rivers of Babylon”, in a deserted gate. “By the rivers of Babylon, where we sat down/And there we wept, when we remembered Zion …”, the song begins. Borrowing its lyrics from Psalm 137 of the Old Testament, “Rivers of Babylon” represents the Rastafarian identification with the ancient Israelites. While the element of nostalgia is pronounced in the verse of Psalm 137, “Rivers of Babylon” instead “offers an exhortation to struggle and protest … The Rasta version replaces the spirit of resignation and self-pity of the Babylonian exile with militant defiance”, David Stowe points out (Stowe 2016, p. 52). In Tripoli Cancelled, such a “militant defiance” is suspended in high tension by the discourse of ‘der Muselmann’, discussed below.

Figure 1.

Naeem Mohaiemen, still from Tripoli Cancelled, 2017, digital video (color, sound), 95 min. © 2017 Naeem Mohaiemen. Courtesy of the artist and Experimenter, Kolkata.

Other scenes point more directly to the liminal space the protagonist inhabits. In one such instance, the protagonist can be seen sifting through a dusty pile of discarded boarding passes on the floor. While the voluminous amount of information (names, destinations, dates, etc.) found in this archive of sorts alludes to the hustle and bustle of millions of journeys that traversed the historic hub, the boarding passes’ dusty state calls to mind Carolyn Steedman’s view of dust as an essential element of the historian’s ‘archival romance’ (Steedman 2001), thus placing the space’s vivacity clearly and decidedly in the past. In another such instance, the protagonist can be seen sitting in the cockpit of an abandoned helicopter, acting out the pilot’s gestures, complete with the requisite sound effects, in what appears to be a burst of childish spontaneity. This sudden demonstration of conviction in the protagonist’s make-believe may symbolize his (desperate) attempt to exercise control over his destiny, a desire that remains elusive throughout the film.

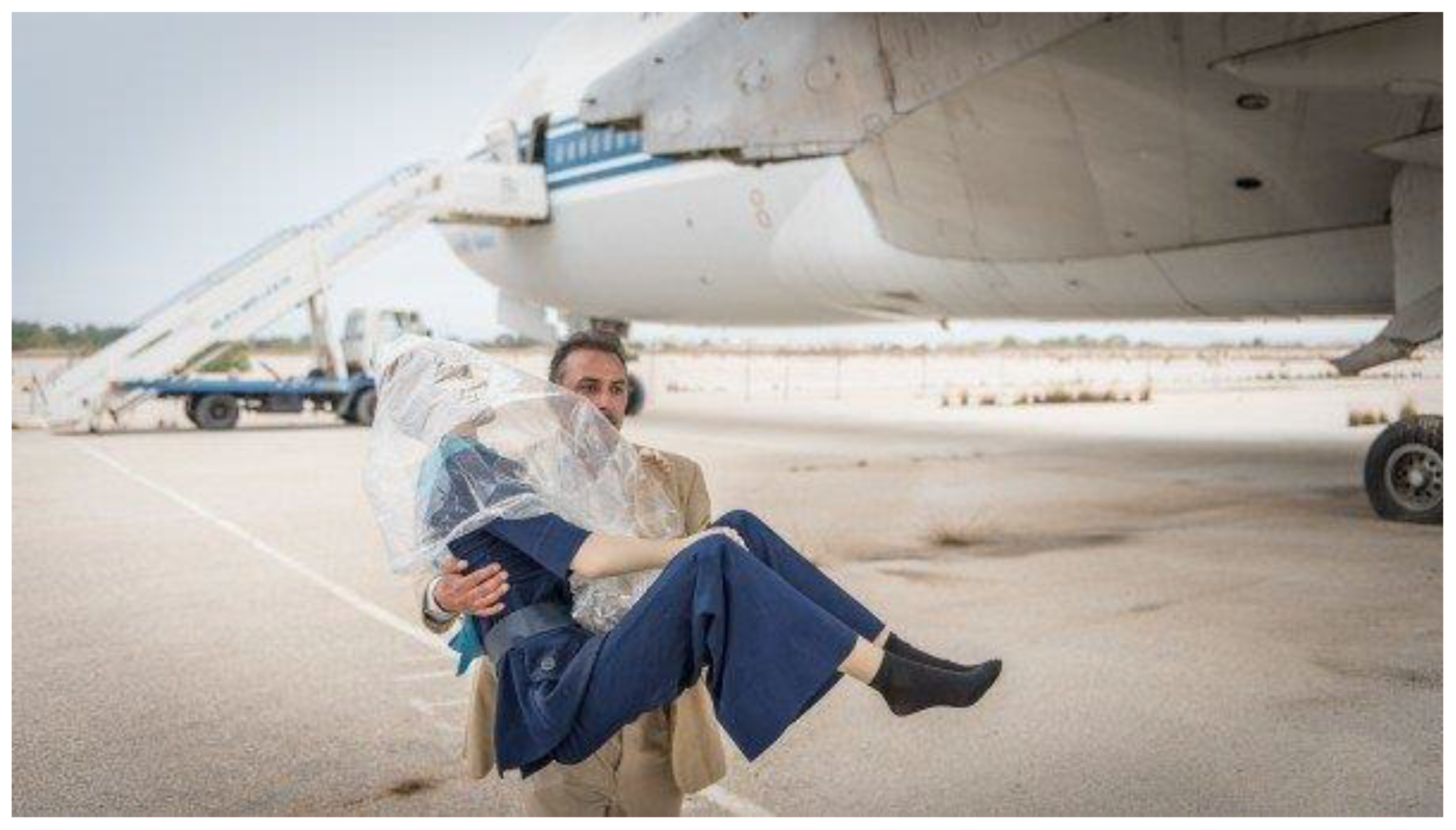

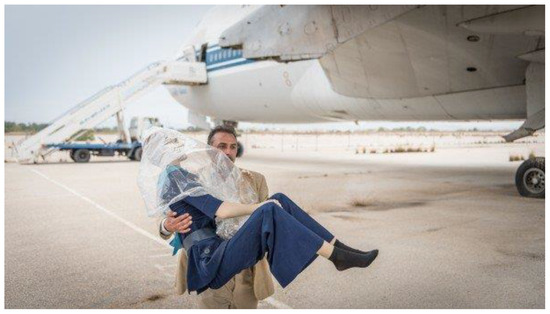

VIGNETTE ONE: The protagonist’s fantasy world extends to a longer sequence unfolding inside the cabin of a decommissioned Olympic Airways (OA) aircraft. Dressed up in what is meant to resemble a pilot’s uniform, the protagonist performs several pre-flight rituals, yet, unsurprisingly, the plane never takes off—an undeniable allusion to the entrapment experienced by countless asylum-seekers in the age of forced migration. Meanwhile, the would-be pilot seeks intimacy in the company of a cast of mannequins in OA stewards’ uniforms (Figure 2). The sense of isolation experienced by the protagonist during his ‘residency’ in the vacant building here seems to have driven him to a psychological breaking point. Despite their statuesque poses and naturalistic features, by being cast in absurd scenarios the mannequins invoke the language of Surrealism. The scene in which the protagonist carries a female mannequin into the aircraft (Figure 3) recalls a 1938 black-and-white photograph by Denise Bellon, in which Salvador Dalí—one of sixteen participants invited by Marcel Duchamp to ‘dress’ the mannequins lining the Surrealist Street greeting visitors to the 1938 International Exhibition of Surrealism at the Galerie des Beaux-Arts in Paris—poses with a headless mannequin in his arms.1 How might we understand the significance of a reference to the interwar Parisian avant-garde in a narrative anchored in the ethics and aesthetics of postwar cosmopolitanism? One possible answer can be excavated from within the film itself.

Figure 2.

Naeem Mohaiemen, still from Tripoli Cancelled, 2017, digital video (color, sound), 95 min. © 2017 Naeem Mohaiemen. Courtesy of the artist and Experimenter, Kolkata.

Figure 3.

Naeem Mohaiemen, still from Tripoli Cancelled, 2017, digital video (color, sound), 95 min. © 2017 Naeem Mohaiemen. Courtesy of the artist and Experimenter, Kolkata.

VIGNETTE TWO: From among Mohaiemen’s intricately layered transcultural and transtemporal historical resonances emerges a moment in which the protagonist’s narrative focuses on the year 1938: “We had a Muselmann staying with us before, back in 1938.”2 Throughout the elliptical narration of the film, the protagonist links (his own) Muslim identity to the liminal space “between being human and not” through the term ‘Muselmann.’ While the etymology of the term has been traced back over centuries through its Italian, Ottoman Turkish, and Persian iterations back to Arabic origins, the antiquated German word for Muslim most notably evokes the nuanced inflection connoted in its use by Auschwitz inmates and guards alike to refer to those “prisoners who were too weak to survive and have given up hope” (Mohaiemen and Lookofsky 2018). The conceptual potency of the Muselmann has been projected, most seminally, through the writings of Primo Levi and Giorgio Agamben. Agamben’s formulation of a figure whose existence is defined by ‘bare life’ and Levi’s account of ‘non-humans’ converge upon the notion of a “lacuna in testimony” (Agamben 1999, p. 41) or “silent automat[on] … a Cartesian empty vessel from which the human spirit is absent” (Ross 2011, p. 49). Moreover, both arrive—albeit through different paths—at the Muselmann’s place within humanity: Levi from a theoretical line of investigation and Agamben from an ethical standpoint (Ross 2011, p. 50). In Tripoli Cancelled, moreover, the concept of ‘der Muselmann’ gets transposed onto the spatial and temporal context(s) of the contemporary phenomenon of desperate migration. Against the filmmaker’s initial impetus to make “a film about loneliness” (Mohaiemen 2018), the use of the abandoned Elliniko Airport as a temporary refugee shelter from February 2016 to June 2017—namely, after the shooting but before the debut of Tripoli Cancelled—commands a historicized reading of the film’s discursive trajectories.

VIGNETTE THREE: Reading from one of his letters to his wife—an act at once introspective and performative, rather than communicative—the protagonist confesses his “inability to locate the qibla” or direction of prayer (McDonough 2018), a reference that resonates with the discourse evoked by his mention of ‘der Muselmann’. Thus, the historicized signifier projects upon the character not only a Muslim identity, but also the archetype of the deracinated figure, from conditions of ‘bare life’ in the Nazi death camps to the displacement of asylum seekers, economic immigrants, and climate refugees in the twenty-first century migration crisis. The protagonist’s deracination and spiritual disorientation echo the words of Simone Weil, who considers a view toward God as a vital element of establishing roots and, conversely, a remedial measure against uprootedness. “In the light of Weil’s writing—and personal experiences—her account of uprootedness stands in haunting relation to the phenomena of diaspora and the experience of forced exile from one’s nation …” (LaRocca and Miguel-Alfonso 2015, p. 14), conditions that similarly permeate the existence of the film’s protagonist. According to David LaRocca and Ricardo Miguel-Alfonso, Kwame Anthony Appiah’s model of ‘rooted cosmopolitanism’ offers a ‘response’ to Weil’s overwhelming concern with the condition of uprootedness (LaRocca and Miguel-Alfonso 2015). In the following section, I take up their proposal and explore (rooted) cosmopolitanism’s critical potential in thinking through the condition of rootlessness.

VIGNETTE FOUR: In the closing scene of the film, the protagonist can be seen seated on an escalator frozen in time, melancholically singing, sotto voce, the emblematic song, “Never on Sunday” (1960). Composed by Manos Hadjidakis for the homonymous Jules Dassin film starring Melina Mercouri, “The Children of Piraeus”, as it was originally titled, became the first song from a foreign-language picture to win an Academy Award for Best Original Song, signaling “a momentum of intensified globality in the history of music made in Greece” (Tragaki 2019). In the fifty-eight years of its afterlife, the song has undergone multiple layers of mediation and has continuously occupied a prominent position in the global imaginary, commonly associated with modern Greek identity. The original song, together with its numerous covers—ranging from translation to parody, including Dizzy Gillespie’s jazz adaptation characterized by Dafni Tragaki as a “creative entanglement of jazzified Greekness”—can be understood in the context of what Tragaki identifies as musical cosmopolitanism “made in Greece” (Tragaki 2019).

Yet, despite the critical acclaim it received and the massive popularity it gained, “Never on Sunday” was renounced by Hajdidakis, as it had, in the multilayered processes of mediation and commodification, lost the qualities with which the composer had imbued “The Children of Piraeus”. Most significantly, the title (and lyrics) of “The Children of Piraeus”, as performed by Mercouri in her role as Ilya, an independent and free-spirited prostitute, convey a sense of social and cultural solidarity among the working classes of Piraeus.3 The political undercurrent of Hadjidakis’s lyrics resonates with the narrative function of Ilya as a symbol of the postwar nation. The renaming of the song to “Never on Sunday”, which sensationalizes Ilya’s occupation, paired with the subsequent decontextualization of the song through the proliferation of popular covers, resulted in the erasure of the composer’s ideologically-inflected message. In Tripoli Cancelled, however, Mohaiemen critically reinscribes the song into two different cosmopolitan contexts. Firstly, by setting the film in the East terminal of Elliniko Airport, used for international flights, he rekindles the song’s cosmopolitan presence within the national imaginary. The protagonist’s melancholy performance of the song echoes sentiments of national yearning for bygone times of affluence and mobility. Secondly, the affinity with which the protagonist sings “The Children of Piraeus” points to the emergence of a cosmopolitan musical sensibility in the second half of the twentieth century, enabled by the multidirectional circulation and mediation of music and motivated—not exclusively, but at least in part—by “an aesthetic interest in others and difference” (Papastergiadis 2012, p. 90).

3. Nostalgia and Cosmopolitanism in Tripoli Cancelled

Taking the protagonist’s condition of displacement as my point of departure, in this section I explore the critical potential of reflective nostalgia and reflexive cosmopolitanism to theorize a position of being-in-the-world that is both informed by history and oriented towards an unavoidably precarious and disjunctive contemporaneity. Departing from Hannah Arendt’s understanding of the right to asylum as essentially state-bound (Arendt [1951] 1958) fifty years after the original publication of her seminal work, The Origins of Totalitarianism, Jacques Derrida turned to the ethical gesture of cosmopolitan hospitality as the only viable alternative in an age of volatile national sovereignty and powerless supranational governance (Derrida [1997] 2001).

Cosmopolitanism, deriving from the Greek word κοσμοπολίτης (kosmopolitês or ‘citizen of the world’), and nostalgia, the compound of νόστος (nóstos or ‘return home’) and ἄλγος (álgos or ‘longing’), seem to pull in opposite directions, as one calls for a rooted connection to place while the other favors rootless circulation. Cosmopolitanism and nostalgia, however, are no strangers. In ancient Greek thought, reconciliation between cosmopolitanism and nostalgia was achieved through the understanding of cosmopolitanism as an essential stage in attaining perspective on one’s self or ‘home’. Thus, cosmopolitanism and nostalgia enter into a positive binary, one governed not by mutual exclusion, but rather by mutual dependency. In modern theory, however, the productive tension between the two concepts seems to dissolve, with nostalgia’s restorative tendencies either calling a normative version of cosmopolitanism back to order (Türeli 2010) or compromising cosmopolitan engagement with strangers (Funchion 2010). As Alastair Bonnett insightfully points out in his introduction to The Geography of Nostalgia: Global and Local Perspectives of Modernity and Loss, a sweeping decline of interest in questions of location against a rising interest in the temporal across academia around mid-twentieth century caused the scope of nostalgia to shift accordingly (Bonnett 2016, p. 2). It was not until the beginning of the twenty-first century that Terry Eagleton sought to counter restorative nostalgia’s ideological associations with sentimentalism, tradition, and conservativism by bringing Walter Benjamin’s revolutionary meaning of nostalgia back to the forefront of critical theory (Eagleton 2000, p. 21). Bonnett, more recently, unearthed the radical potential of nostalgia, positioning it “as a site of historical acknowledgement, experience, and exploration” (Bonnett 2010, p. 2352). In her influential book, The Future of Nostalgia (2001), Svetlana Boym insightfully distinguishes between two major types of nostalgia. In its most typical form, ‘restorative’ nostalgia represents a desire to reconstruct “emblems and rituals of home and homeland in an attempt to conquer and spatialize time” (Boym 2001, p. 49). In contrast, ‘reflective’ nostalgia “dwells on the ambivalences of human longing and belonging” (Boym 2001, p. xviii), “cherishes shattered fragments of memory and temporalizes space” (Boym 2001, p. 49). In what follows, I pursue parallel readings of Tripoli Cancelled through Svetlana Boym’s two types of nostalgia and a nuanced model of cosmopolitanism informed by the writing of Kwame Anthony Appiah, Ulrich Beck, Seyla Benhabib, and Nikos Papastergiadis, in an effort to reenergize the points of intersection between these two theoretical frameworks.

On its surface, Tripoli Cancelled seems to be permeated by Boym’s ‘restorative’ nostalgia. Most prominent is the anonymous protagonist’s nostalgia for the material and affective attachments of his previous life; poignant, in this respect, is his desperate attempt to explain, likely to a telephone operator of a bygone era, that his wife is “always home … waiting for [his] call”. The film is also imbued with the artist’s own nostalgia, as he revisits and restages scenes of autobiographical significance. Reaching beyond the personal into the collective, the film also evokes Greek audience members’ memories of their own past travels. In a national context, moreover, the modernist building, backed by shipping tycoon Aristotle Onassis and designed by leading midcentury Finnish-American architect Eero Saarinen, functions as a historical reminder of the postwar boom, an era characterized by the trademarks of normative cosmopolitanism: affluence, modernity, and glamor.

Such versions of cosmopolitanism, dubbed ‘banal cosmopolitanism’ by Ulrich Beck, have been widely criticized in recent decades for celebrating economic privilege, cultural elitism, and rootlessness of the geopolitical and the moral varieties alike (Mendieta 2009). More ominously, the notion of moral universalism advanced by cosmopolitanism has functioned for centuries as a central ideological pillar of European hegemony, resulting in what Immanuel Wallerstein describes as the world-system. In the words of Peter Hitchcock, “[t]raditionally, cosmopolitanism has been too brusquely associated with a kind of insipid Western worldliness—either one of insouciant imperialist panache or one of a generally liberalist pedigree (oscillating between ‘I know where you’re coming from’ to ‘I own where you’re coming from’)” (Hitchcock 1998, p. 429). Domna Stanton calls for the blurring of the binary opposition between cosmopolitanism and the various units of the geopolitical scale: “If cosmopolitanism since the early modern period has been defined in opposition to the nation and then nationalism, it becomes clear today, after the end of the cold war, that such binary thinking must be rejected in favor of a more capacious view that encompasses both the national and the transnational, the local and the global” (Stanton 2006, p. 636). Increasingly, alternative—resistant or critically inflected—definitions of cosmopolitanism, motivated by a keenness to engage with the Other, have begun to emerge in critical theory.4 Despite their respective nuances, these formulations can be aptly summed up as “what might help us counter nationalism and humanize globalization, pushing it to be a vehicle for freedom and opportunity for most, not just a privileged few” (Petriglieri 2016); as an endorsement of “reflective distance from one’s cultural affiliations, a broad understanding of other cultures, and a belief in universal humanity” (Anderson 1998, p. 267); as “forms of consciousness . . . heightened by the intensified flows or abrupt confrontations with cultural difference” (Papastergiadis 2012, p. 143); or as “a tolerance for conditions of multiple temporalities” (Okeke-Agulu and Enwezor 2009, p. 19). As such, cosmopolitanism provides a capacious and dynamic theoretical framework for the illumination of Mohaiemen’s vision.

Rejecting cultural purity as a discursive figment, Appiah proposes the notion of cosmopolitan contamination (Appiah 2006)—a position echoed in Papastergiadis’s affirmation that in order to “grasp the forms of cosmopolitan agency”, we need a perspective on identity “that can comprehend the fluidity of mixture” (Papastergiadis 2007, p. 145). In the Roman comedy The Self-Tormertor by Publius Terentius Afer, the Carthage-born slave who emerged as one of the most successful playwrights of late second century AD Rome, Appiah finds what he refers to as “the golden rule of cosmopolitanism: Homo sum: humani nil a me alienum puto. ‘I am human: nothing human is alien to me’” (Appiah 2006, p. 111). Tracing the history of ‘contamination’ back to the early Cynic and Stoic philosophers who “took their contamination from the places they were born to the Greek cities where they taught”, Appiah gestures to the longue durée history of global circulation of objects and attitudes, from the age of empire to the age of global capital, a historiographical approach adopted more recently by Thomas DaCosta Kaufmann, Catherine Dossin, and Béatrice Joyeux-Prunel in their edited volume, Circulations in the Global History of Art (2015). In the realm of literature, Appiah points out, “the ideal of contamination has no more eloquent exponent than Salman Rushdie”, who declares of hybridity, impurity, and intermingling that it is “the great possibility that migration gives the world, and I have tried to embrace it” (Appiah 2006, p. 112). At the convergence of these geographic and intellectual trajectories, Appiah concludes that a “tenable cosmopolitanism tempers a respect for difference with a respect for actual human beings” (Appiah 2006, p. 113).

Ulrich Beck takes the critique of cosmopolitanism one step further, asserting that even cosmopolitan empathy, when invoked within the context of multiculturalist moralism, can itself provoke military conflicts, as “[w]ell-meaning multiculturalists can easily ally themselves with cultural relativists, thereby giving a free hand to despots who invoke the right to difference” (Beck 2006, p. 67). At the head of such an agenda is the position that “individuals are merely epiphenomena of their cultures. Hence there is a direct line leading from the duality between Europe and its barbarian others, through imperialism, colonialism and Eurocentric universalism, to multiculturalism and ‘global dialogue’” (Beck 2006, p. 67). It is in cosmopolitanism, and cosmopolitanism alone, that Beck identifies the potential to supersede the “social predetermination of the individual that marks classical sociology” (Beck 2006, p. 67). Beck’s formulation of ‘cosmopolitan realism’ is based on Edgar Grande’s notion of ‘reflexive cosmopolitanism’, one which “must not only incorporate different substantive norms and principles, [but] must also integrate and balance different modalities and principles of dealing with difference” (Grande quoted in Beck 2006, p. 68). For Beck, three critical axes permeate cosmopolitanism: the transnational; the postcolonial; and the hybrid. More specifically, the concept of cosmopolitan realism is triangulated by the following key positions: (a) the break from “the hallowed principle of national sovereignty”; (b) the transformation of European subjectivity based on the postcolonial interweaving of the ‘European self’ with the ‘excluded other’ and the resulting expansion of the national into the cosmopolitan; and (c) the positive transvaluation of concepts such as ‘diaspora’, ‘cultural métissage’ (or creolization), ‘hybridity’, and even ‘rootlessness’, as well as the experiences of alienation and loss of ontological security (Beck 2006, pp. 68–70). Elsewhere, Beck distinguishes cosmopolitan realism from normative cosmopolitanism and situates it within a broader epistemological turn in which national perspectives became disenchanted and transnational methodologies took their place (Beck 2004, p. 132).

Indeed, both Appiah’s conception of rooted cosmopolitanism as a model for cultural contamination and Beck’s conception of cosmopolitan realism as models for transnational and transcultural plurality converge with Boym’s notion of ‘reflective nostalgia’. From the theoretical milieux of nostalgia and cosmopolitanism, as well as the worldly conditions of homelessness, dispossession, and rootlessness, emerges the corollary concept of hospitality, powerfully present—if latent—in Tripoli Cancelled across different layers of the film’s imagery and (meta)narrative. Interestingly, Mohaiemen has twisted the double bind of the concept of hospitality into a curious knot: the protagonist’s right to asylum may linger persistently in every scene, yet the complete absence of all other human presence in the film leaves the duty of hospitality poignantly unassigned—perhaps a metaphor for the corresponding inertia of national and international bodies in safeguarding the universal right to asylum.

In the philosophical realm, Immanuel Kant’s framing of hospitality as a ‘cosmopolitan right’ has had a lasting legacy in discourses on the intersection between state sovereignty and international human rights law. Seyla Benhabib, largely influenced by Kantian theory, reads his doctrine of universal hospitality as “opening up a space of discourse, a space of articulation, for ‘all human rights claims which are cross-border in scope’” (Benhabib 2006, p. 148). Such a reading of the Kantian ideal of universal and unconditional hospitality as a cosmopolitan right resonates deeply with the ancient Greek notion of ξενία (xenía) as a divine right, yet one framed by uncertainty:

A Greek could never know in advance whether a stranger was an enemy or a god in disguise. The conventions of Greek hospitality were therefore laced with a mixture of self-interest and the desire to please the gods. To share food and offer gifts to a stranger was considered the highest form of civilization.(Papastergiadis 2012, p. 57)

In contrast, Derrida views the ‘right’ of the stranger and the ‘duty’ of the host as conditional, contingent upon their reciprocally peaceful intentions (Papastergiadis 2012, p. 156). In a similar vein as Benhabib, Nikos Papastergiadis theorizes hospitality as “a fundamental gesture that facilitates the encounter and understanding between strangers”, but observes that in the past decade the “possibilities for welcoming strangers and recognizing the needs of others has been violently disfigured” at a social and political level alike (Papastergiadis 2014). In invoking Derrida’s ‘ethic of hospitality’, according to which “the guest and host are mutually entangled”, Papastergiadis gestures toward a ‘hospitality of art’, a Rancièrian equation of politics and aesthetics (Papastergiadis 2007) that aptly describes Tripoli Cancelled. Indeed, Mohaiemen’s multilayered narrative expresses, more powerfully than Rancière himself, the alluring tension between the aesthetic and the political: “Aesthetic art promises a political accomplishment that it cannot satisfy, and thrives on that ambiguity. That is why those who want to isolate it from politics are somewhat beside the point. It is also why those who want it to fulfil its political promise are condemned to a certain melancholy” (Rancière 2010, p. 133).

The intellectual regimes of restorative nostalgia and normative cosmopolitanism apparent on the film’s surface are complicated by the film’s narrative of displacement. The protagonist’s fictional experience of exile resonates on multiple levels. Most closely, it parallels the artist’s own biography: when he was posted to work as a doctor in Tripoli in 1977, the artist’s father departed India, where he and his family had been living, to relocate to Libya; while in transit, however, his father lost his passport and thus found himself trapped inside the then Athens airport for nine days. The protagonist’s experience of displacement moreover resonates with the actor who brings him to life. Born in Köln, Germany, to an Iranian father and a Greek mother, and raised between Tehran and Athens, Vassilis Koukalani has, since childhood, developed his own cosmopolitan immigrant culture, as one interviewer recently observed (Antonopoulos 2016). Koukalani’s handling of the English language projects upon his character an identity of diasporic cosmopolitanism much like his own and much like the filmmaker’s. Importantly, the subjectivities of Mohaiemen, Koukalani, and the anonymous protagonist alike can be further situated within the Global South or perhaps what Walter Mignolo refers to as the ‘colonial difference’ (Mignolo 2002).

On a broader scale, the literally and metaphorically liminal space inhabited by the protagonist resonates with the contemporary conditions of desperate migration permeating much of Asia, Africa, and Europe. As the epicenter of these migratory flows, Greece, along with the other territories surrounding the Mediterranean, has become entangled in the asymmetries of power and privilege between the desperate migrants’ quest for a more peaceful and equitable future and European nation-states’ protectionist immigration policies. The former Elliniko Airport was recently one of dozens of sites used by Greek authorities as shelters for displaced migrants and asylum seekers, who found themselves trapped, like the film’s protagonist and the artist’s father, by the impermeability of national borders. Despite the fact that Mohaiemen’s interest in shooting at the Elliniko Airport was not originally motivated by the building’s recent function as a refugee camp, this connotation is rather inescapable; thus, site specificity functions as a crucial source of meaning in Tripoli Cancelled. Furthermore, through his protagonist’s invocation of Hannah Arendt’s understanding of acts of genocide in the Third Reich as crimes against humanity and the discourse of ‘der Muselmann’ in the historical context of Auschwitz, Mohaiemen offers a historicist lens through which to view contemporary desperate migration. Such a reading of the new against the grain of the past shifts the film into the registers of reflective nostalgia and reflexive cosmopolitanism.

4. Cold War Cosmopolitanism: The Elliniko International Airport in Historical Context

The first airport in Greece, located on the outskirts of Athens, near the port of Piraeus, opened in 1938. By the mid-1950s, however, the postwar economic boom in general and the founding of Olympic Airways by Aristotle Onassis in particular necessitated expanded and modernized aviation facilities, and the site of the new airport became, once again, the subject of heated debate.5 By 1961, several rounds of consultations with aviation experts later, it had been determined that the airport would, in fact, stay in Elliniko and on May 25 Eero Saarinen arrived in Athens to present his proposed designs for a new East Terminal, slated to serve international flights, to the Ministry of Transportation. In contrast to his earlier airport projects, characterized by their “soaring, curvilinear forms”, here Saarinen “opted for a more restrained design at Athens” (Canadian Centre for Architecture 2003). It is worth noting here that 1961 can be seen as a landmark year in the postwar architectural history of Athens, intertwined as it is with the international politics of the Cold War; it was on July 4—U.S. Independence Day—of that year that the new U.S. Embassy, designed by Walter Gropius, was inaugurated.

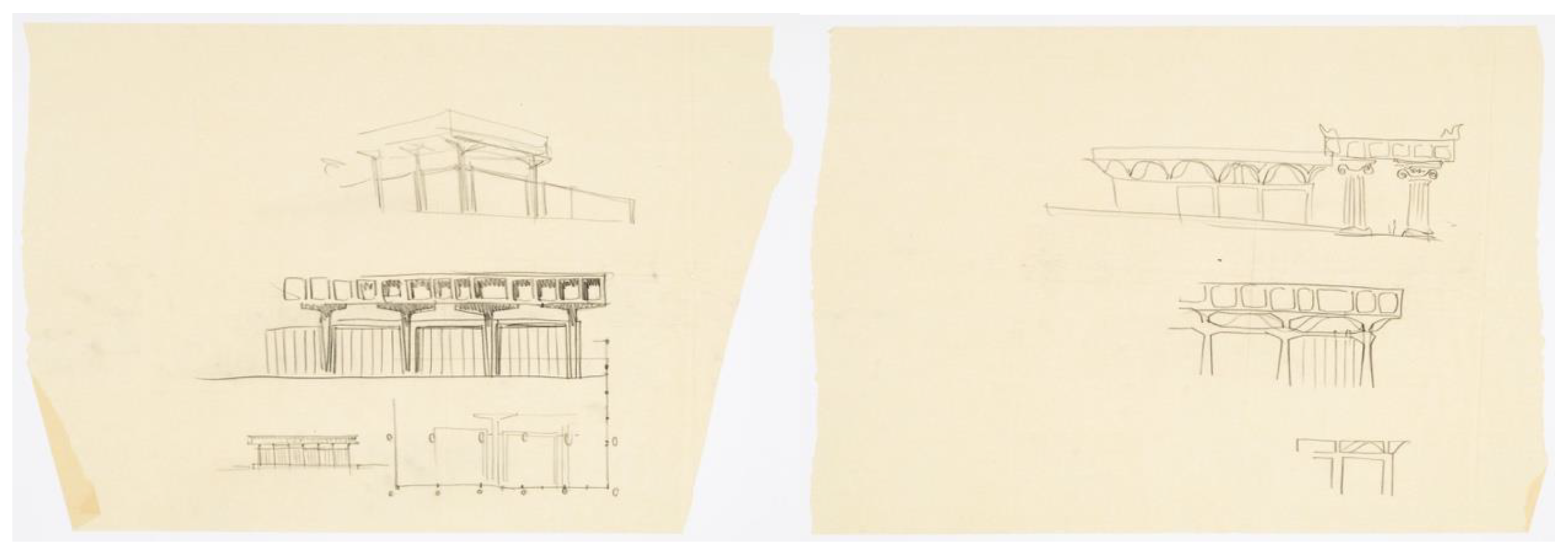

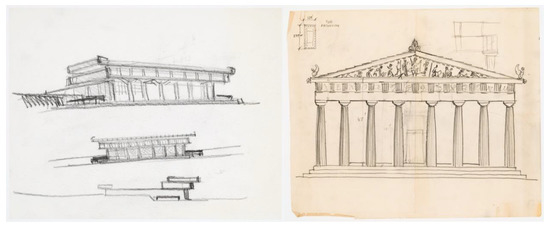

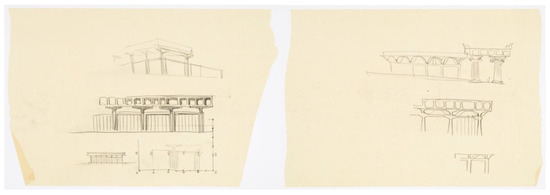

Saarinen’s conceptual sketches for the Elliniko project (Figure 4) show “how the columnar rhythm and load-bearing, post and lintel construction of Greek temple architecture served as an initial inspiration” (Canadian Centre for Architecture 2003). Indeed, the extent of the aesthetic relationship between modernism and classical antiquity is an aspect of architectural history that calls for further emphasis. Telling, in this respect, is Le Corbusier’s reflection on his 1911 visit to the Acropolis: “Greece, and in Greece the Parthenon, have marked the apogee of this pure creation of the mind”, the architect whose vision contributed heavily towards the emergence of midcentury modernism remarked in his seminal book, Towards a New Architecture (Le Corbusier [1923] 1986, p. 218). In the late 1950s, Gropius similarly remarked of his designs for the new U.S. Embassy in Athens that it “should be inspired by the Greek spirit”.6 Though Saarinen did not live to see the realization of his design, as he died later in 1961, eight years before its completion in 1969, the East Terminal would become a symbol of internationalism in the era of postwar prosperity (and characterized as a heritage building in 2006, five years after the opening of the new Eleftherios Venizelos Athens International Airport).

Figure 4.

Eero Saarinen, conceptual sketches for Athens Airport, 1960, graphite on tracing paper, Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montréal, gift of David Graham Powrie. From top left to bottom right: Conceptual Perspective, Elevation and Section Sketches; Elevation with Plan of the Parthenon; Conceptual Perspective, Elevation and Plan Sketches; Conceptual Elevation Sketches.

Around midcentury, International Style architectural vocabularies were circulated widely across the ‘Western’ world by the United States as emblems of modernity, progress, and (neo)liberal democracy. The United States had, in fact, begun to exercise influence on Greece in the 1920s and 1930s, but it was not until 1947 that the Truman Doctrine announced Washington as the successor of London’s role as guarantor of the country’s western orientation (Botsiou 2010, p. 180). With the end of the Civil War in 1949 and the induction of Greece into NATO in early 1952, the significance of Greece as a strategic ally of the United States in the region began to solidify. While after 1955 the U.S. gradually shifted its tactics of influence from economic dependence to the field of ideology—and particularly to the practice of cultural diplomacy under the Kennedy presidency—American actors continued to play key roles in the country’s infrastructural development for decades. The selection of the New York firm Ammann & Whitney for the technical study and management of the Elliniko project, as well as the naturalized American architect Eero Saarinen for the design, reflects the concurrent operation of both spheres of influence on the American part. Despite its undoubtedly hegemonic role in the non-communist world during the Cold War, the United States promoted a cosmopolitan vision of internationalism, characterized by a shared code of neoliberal values.

Marc Augé’s consideration of airports as quintessential examples of non-places may be useful in understanding Elliniko Airport in its former life as an operational transportation hub. According to Augé, the condition of supermodernity has transformed certain spatial typologies into spaces devoid of the relational, historical, or identity-concerned qualities that define place (Augé [1992] 1995, pp. 77–78). The operation of Elliniko Airport within the narrative space of Tripoli Cancelled, however, diverges considerably from Augé’s model, as it exceeds the typical function of a building as set. Rather, its most significant role is its semiotic function, imbuing the film with relational and entangled questions relating to history and identity. Thus, within the cinematic context of Tripoli Cancelled, Elliniko Airport (re)gains ‘space’ status.

5. Epilogue

Through the suspension of time, the expansion of space, and the entanglement of identity, Tripoli Cancelled compellingly affirms the continued relevance of reflective nostalgia and reflexive cosmopolitanism to both contemporary life and contemporary art. Cosmopolitanism emerged as a useful tool in my attempts to solve the equation of politics and aesthetics proposed by Tripoli Cancelled. Before I could tackle this Rancièrian equation, however, I had to take up Mohaiemen’s challenge of fixing the flaw(s) in the algorithm of cosmopolitanism.7 In pursuing these two disparate in scope yet inevitably intersecting tasks, this article is far from linear in its development. I appreciate my readers’ patience in joining me down the meandering paths of my inquiry and hope they have enjoyed moments of enlightenment (or at least delight) along the way. As a gesture of clarity, I offer the following summary of my findings. Deeply informed by both its creator’s and its protagonist’s lived experiences of transnational and transcultural hybridity across the perceived border between the Global North and Global South, Tripoli Cancelled presents a vision of cosmopolitan worldmaking that encourages openness, incites empathy, and offers hope. Its impact in discursive and affective registers alike parallels the dual operation of critical cosmopolitanism in the fields of ethics and aesthetics. “Imagining ourselves at home in the world, where our homes are not fixed objects but processes of material and conceptual engagement with other people and different places, is the first step toward becoming cosmopolitan”, Marsha Meskimmon (2011, p. 8) asserts. Indeed, Tripoli Cancelled renders the productive relationship between ethical cosmopolitanism and aesthetic cosmopolitanism in high relief. If the principle of cosmopolitan hospitality emerges as an ethical imperative, then agents of cosmopolitan imagination like Tripoli Cancelled allow us to envision the making of such a world.

Funding

The research for this article was funded in part by a Doctoral Fellowship from the Alexander S. Onassis Public Benefit Foundation.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to the editors of this special issue, Jennifer Barker and Christa Zorn, for their enthusiastic reception and thoughtful stewardship of my manuscript, as well as the two external reviewers for their insightful feedback.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the research or writing of the manuscript.

References

- Agamben, Giorgio. 1999. The Muselmann. In Remnants of Auschwitz: The Witness and the Archive. Translated by Daniel Heller-Roazen. Brooklyn: Zone Books, pp. 41–86. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, Amanda. 1998. Cosmopolitanism, Universalism, and the Divided Legacies of Modernity. In Cosmopolitics: Thinking and Feeling beyond the Nation. Edited by Pheng Cheah and Bruce Robbins. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, pp. 265–89. [Google Scholar]

- Antonopoulos, Thodoris. 2016. Ο Βασίλης Κουκαλάνι και η μπίζνα των συνόρων [Vassilis Koukalani and the Business of Borders]. LiFO. December 8. Available online: https://www.lifo.gr/articles/cinema_articles/123827 (accessed on 13 January 2019).

- Appiah, Kwame Anthony. 2006. Cosmopolitanism: Ethics in a World of Strangers. New York and London: W. W. Norton & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Arendt, Hannah. 1958. The Origins of Totalitarianism, 2nd ed. Cleveland and New York: Meridian Books. First published 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Augé, Marc. 1995. Non-Places: Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity. Translated by John Howe. London and New York: Verso. First published as Non-Lieux, Introduction à una anthropologie de la supermodernité. 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, Ulrich. 2004. Cosmopolitan Realism: On the Distinction between Cosmopolitanism in Philosophy and the Social Sciences. Global Networks 4: 131–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, Ulrich. 2006. Cosmopolitan Vision. Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Benhabib, Seyla. 2006. Hospitality, Sovereignty, and Democratic Iterations. In Another Cosmopolitanism. Edited by Robert Post. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bonnett, Alastair. 2010. Radicalism, Antiracism, and Nostalgia: The Burden of Loss in the Search for Convivial Culture. Environment and Planning A 42: 2351–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnett, Alastair. 2016. Introduction. In The Geography of Nostalgia: Global and Local Perspectives of Modernity and Loss. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Botsiou, Konstantina. 2010. H επιρροή των HΠΑ στη μεταπολεμική Ελλάδα: Αλληλεπιδράσεις πολιτικής και πολιτισμού [U.S. Influence in Postwar Greece: The Interaction of Politics and Culture]. In H δική μας Αμερική: H αμερικανική κουλτούρα στην Ελλάδα [Our America: American Culture in Greece]. Edited by Helena Maragou and Theodora Tsimpouki. Athens: Metaichmio, pp. 179–237. [Google Scholar]

- Boym, Svetlana. 2001. The Future of Nostalgia. New York: Basic. [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Centre for Architecture. 2003. Eero Saarinen: Athens Airport. Cached 24 January 2013. Available online: https://www.webcitation.org/6DuiSXLEN?url=http://www.cca.qc.ca/en/collection/1078-eero-saarinen-athens-airport (accessed on 29 January 2019).

- Derrida, Jacques. 2001. On Cosmopolitanism and Forgiveness. Translated by Mark Dooley, and Michael Hughes. with a preface by Simon Critchley and Richard Kearney. London and New York: Routledge, Originally published in French, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Documenta 14. 2014. Learning from Athens (Press Release). October 7. Available online: http://newsletter.documenta.de/t/j-12C9729D2BF513CC#english (accessed on 2 March 2017).

- Documenta 14. 2015. Launch of the Documenta 14 Publication Program with South as a State of Mind #6 [documenta 14 #1] (Newsletter). October 14. Available online: http://www.documenta14.de/newsletter/10/2015-10-14_en.html (accessed on 26 March 18).

- Eagleton, Terry. 2000. Versions of Culture. In The Idea of Culture. Malden: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Funchion, John. 2010. When Dorothy Became History: L. Frank Baum’s Enduring Fantasy of Cosmopolitan Nostalgia. Modern Language Quarterly 71: 429–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitchcock, Peter. 1998. Cosmopolitan Contraries. Postcolonial Studies 1: 429–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koundoura, Maria. 2007. The Greek Idea: The Formation of National and Transnational Identities. London and New York: I. B. Tauris. [Google Scholar]

- LaRocca, David, and Ricardo Miguel-Alfonso. 2015. Introduction: Thinking Through International Influence. In A Power to Translate the World: New Essays on Emerson and International Culture. Edited by David LaRocca and Ricardo Miguel-Alfonso. Hanover: Dartmouth College Press, pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Le Corbusier. 1986. Towards a New Architecture. Translated and with an Introduction by Frederick Etchells. New York: Dover Publications. First published 1923. [Google Scholar]

- McDonough, Tom. 2018. Bare Life: Naeem Mohaiemen’s There Is No Last Man. BOMB Magazine. January 29. Available online: https://bombmagazine.org/articles/bare-life-naeem-mohaiemens-there-is-no-last-man/ (accessed on 26 January 2019).

- Mendieta, Eduardo. 2009. From Imperial to Dialogical Cosmopolitanism. Ethics & Global Politics 2: 241–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meskimmon, Marsha. 2011. Contemporary Art and the Cosmopolitan Imagination. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Mignolo, Walter. 2002. The Geopolitics of Knowledge and the Colonial Difference. The South Atlantic Quarterly 101: 57–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohaiemen, Naeem. 2018. Naeem Mohaiemen: ‘I Wanted to Take the Documentary Form and Jar It.’ By Killian Fox. The Guardian. September 22. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2018/sep/22/naeem-mohaiemen-turner-prize-2018-documentary (accessed on 25 November 2018).

- Mohaiemen, Naeem, and Sarah Lookofsky. 2018. The History That Did Not Come to Pass: Naeem Mohaiemen in Conversation with Sarah Lookofsky. Post: Notes on Modern and Contemporary Art Around the Globe. February 7. Available online: https://post.at.moma.org/content_items/1089-the-history-that-did-not-come-to-pass-naeem-mohaiemen-in-conversation-with-sarah-lookofsky (accessed on 28 January 2019).

- Nerdinger, Winfried. 1985. Walter Gropius. Berlin: Bauhaus-Archiv. [Google Scholar]

- Okeke-Agulu, Chika, and Okwui Enwezor. 2009. Contemporary African Art Since 1980. Bologna: Damiani Press. [Google Scholar]

- Papastergiadis, Nikos. 2007. Glimpses of Cosmopolitanism in the Hospitality of Art. European Journal of Social Theory 10: 139–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papastergiadis, Nikos. 2012. Cosmopolitanism and Culture. Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Papastergiadis, Nikos. 2014. Interview by Alistair Brisbourne. Interview with Professor Nikos Papastergiadis on ‘Cosmopolitanism and Culture’. Global Studies Association. June 19. Available online: https://globalstudiesassoc.wordpress.com/2014/06/19/interview-with-professor-nikos-papastergiadis-on-cosmopolitanism-and-culture/ (accessed on 14 March 2018).

- Petriglieri, Gianpiero. 2016. In Defense of Cosmopolitanism. Harvard Business Review. December 15. Available online: https://hbr.org/2016/12/in-defense-of-cosmopolitanism (accessed on 18 May 2018).

- Rancière, Jacques. 2010. The Aesthetic Revolution and Its Outcomes. In Dissensus: On Aesthetics and Politics. London and New York: Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, Charlotte. 2011. Embodying (In/Non-)Humanity. In Primo Levi’s Narratives of Embodiment: Containing the Human. New York and London: Routledge, pp. 41–61. [Google Scholar]

- Stanton, Domna. 2006. Presidential Address 2005: On Rooted Cosmopolitanism. PMLA 121: 627–40. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/25486345 (accessed on 29 January 2019). [CrossRef]

- Steedman, Carolyn. 2001. Dust: The Archive and Cultural History. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stowe, David W. 2016. Song of Exile: The Enduring Mystery of Psalm 137. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tragaki, Dafni. 2019. Introduction: Greek Popular Music Studies? In Made in Greece: Studies in Popular Music. Edited by Dafni Tragaki. New York: Routledge. Ebook. [Google Scholar]

- Türeli, Ipek. 2010. Ara Güler’s Photography of ‘Old Istanbul’ and Cosmopolitan Nostalgia. History of Photography 34: 300–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | This image has not been reproduced here due to pending copyright clearance, but can be found in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago: https://www.artic.edu/artworks/236348/salvador-dali-with-his-manniquin-international-surrealist-exhibition-paris. |

| 2 | The artist’s critical engagement with the historical moment of 1930s Nazi Germany from a transnational perspective in fact appears elsewhere in Mohaiemen’s work and specifically occupies a central position in his text-and-image work, Volume Eleven (flaw in the algorithm of cosmopolitanism) (2016). More specifically, however, 1938 was not only a year of escalating geopolitical turmoil, as the imminence of Nazi occupation overshadowed Europe, but also the year in which the dictatorial government of Ioannis Metaxas, under the watchful eye of anglophile King George ΙΙ, inaugurated Elliniko Airport, as will be discussed in more detail in Section 4. |

| 3 | Piraeus has served as the seaport of Athens and one of the largest shipping centers of the Mediterranean since the 5th century BC. In the mid-twentieth century, the population of Piraeus belonged predominantly to the working classes—factory workers, dock workers, and other menial laborers, who, having arrived from Asia Minor in 1922 as displaced and destitute refugees, struggled for decades to survive. Harsh labor conditions and subpar housing facilities (mostly shanties) persisted up until 1960, when residents, shopkeepers, and factory workers all went on strike in protest of the governments’ plan to raise all shanties in a major real estate development project that would leave occupants homeless for an indefinite period of time. Jules Dassin’s interest in and sympathy toward such a subject is in keeping with his leftist filmmaking practice overall. |

| 4 | Such strands, emerging largely in scholarship of the last twenty or so years, include Amanda Anderson’s ‘inclusionary cosmopolitanism’, Kwame Anthony Appiah’s ‘rooted cosmopolitanism’ (a term also invoked, albeit with subtle variations, by Bruce Ackerman, Mitchell Cohen, David Hollinger, Scott Malcolmson, and Domna Stanton), Seyla Benhabib’s ‘ethical cosmopolitanism’, what Homi Bhabha and Paul Gilroy refer to as ‘vernacular cosmopolitanism’, James Clifford’s ‘discrepant cosmopolitanism’, Toni Erskine’s ‘embedded cosmopolitanism’, Partha Mitter’s ‘virtual cosmopolitanism’, Nikos Papastergiadis’s ‘aesthetic cosmopolitanism,’ and Bruce Robbins’s ‘comparative cosmopolitanisms’, among others. |

| 5 | Indicative of this trend are the statistics that the projected traffic for 1968 was, in fact, already reached in 1967, a year in which the previous iteration of the Elliniko Airport accommodated more than three million passengers. |

| 6 | Winfried Nerdinger has argued that in contrast to Gropius’s vision that the project should only take conceptual cues from the “Greek spirit” without reproducing features found in a classical Greek temple, in the end several of the building’s formal elements made the embassy appear historicist (Nerdinger 1985, p. 287). |

| 7 | In 2015, Naeem Mohaiemen contributed a photo essay to volume #6 of South as a State of Mind, titled “Volume Eleven (A Flaw in the Algorithm of Cosmopolitanism)”, a project that “responded to Documenta’s origin in the post-war German denazification history, by looking at imbrications of Asian histories with the European pre-war condition”. Naeem Mohaiemen, “Volume Eleven (A Flaw in the Algorithm of Cosmopolitanism)”, artist’s website, https://www.shobak.org/volume-eleven-flaw-in-the-algorithm-of-cosmopolitanism. |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).