1. Introduction

More than 8.5 million soldiers died in the First World War, and almost 50,000 of them were Irish (

Ferriter 2004, p. 388). The scale and slaughter of the war, the American literary and cultural historian Paul Fussell has argued, shattered British Victorian notions of history and “reversed the Idea of Progress” (

Fussell 1975, p. 8). In Ireland, as Irish historian R. F. Foster explains, the war had profound political consequences: “it temporarily defused the Ulster situation; it put Home Rule on ice; it altered the conditions of military crisis in Ireland at a stroke; and it created the rationale for an IRB rebellion” (

Foster 1988, p. 471). For these reasons,

Foster (

1988) argues, “the First World War should be seen as one of the most decisive events in modern Irish history” (p. 471). But what Foster terms an “IRB rebellion”—better known as the 1916 Easter Rising—has largely eclipsed the Irish experience of the Great War in Irish historical narratives, even though Ireland contributed roughly 210,000 men to the war effort.

1 In April of 1916, just a few months before the Somme, a coalition of rebels led by Padraig Pearse and James Connolly (among others), staged a coup in Dublin, taking over several important administrative buildings and issuing a “Proclamation of an Irish Republic.” The disorganized, slipshod rebellion provoked a harsh response from British authorities, who executed 15 of its leaders over a 10-day period and, in the process, turned a formerly apathetic public’s sympathies towards the rebels (

Beckett 1966, p. 441). William Butler

Yeats (

2000) famously summarized the effect of the so-called Easter Rising in the refrain of his poem “Easter 1916”: “All changed, changed utterly/A terrible beauty is born.”

The convergence of these two events was not an accident. The First World War came at a time when divisions that had been festering between Ireland and Britain over the long 19th century were finally coming to a head. An Irish Home Rule bill had been approved by the British Parliament in 1914, despite significant opposition from unionist Protestants. The outbreak of the war in 1914, however, delayed its implementation. The Easter Rising was, in part, a reaction to this delay that put the 19th century axiom “England’s difficulty is Ireland’s opportunity” into practice.

The Easter Rising became a foundational event in most histories of Ireland, but the significance of the First World War to 20th century Irish history is frequently overlooked. In his preface to the Trinity History Workshop’s collection

Ireland and the First World War (1986), David Fitzpatrick laments the frequency with which works of Irish history “treat the war as an external factor which did little more than modify the terms of political debate and redefine political alignments in Ireland [and] reduce a social catastrophe, which left few people untouched, to the status of a minor if unfortunate disturbance” (viii). The same is true of Irish literature. Declan Kiberd’s nationalist literary history of Ireland,

Inventing Ireland (1995), a 695-page tome, devotes nine pages to the theme of “The Great War and Irish Memory,” and most of these discuss the war only in relation to the Easter Rising (

Kiberd 1995).

2 Even Foster’s well-respected

Modern Ireland: 1600–1972 (1988) does not devote much time to the Irishmen who participated in the war, although it does examine at length the war’s effect on IRB strategy and the British response to the Rising.

Recent years, though, have seen a shift in the cultural and historical responses to Irish involvement in the First World War. Frank McGuinness’s 1985 play

Observe the Sons of Ulster Marching Towards the Somme was widely praised for its depiction of the Irish unionist soldiers of the 36th (Ulster) Division.

3 The subject of this article, Sebastian Barry’s novel

A Long Long Way, was released to critical acclaim in 2005. On the 100th anniversary of the Battle of the Somme in July 2016, the Republic of Ireland and the Royal British Legion (Republic of Ireland) held a joint Centenary Commemoration Ceremony (

Department of the Taoiseach 2018).

2. ‘I Will Go Down—If I Go Down at All—As a Bloody British Soldier’

Part of the problem with defining an Irish experience of the First World War is that at the time of the war the island of Ireland was culturally and politically divided.

4 British colonization from the 17th century onwards had created a class of Protestant landowners and industrialists. Members of the “Protestant Ascendancy,” as it was known, spoke English and belonged to the Church of Ireland. They both benefited from and contributed to British occupation of the island. Meanwhile, most of the landless and working classes identified as culturally Irish

5 and remained Roman Catholic. Generally speaking, it was in the interests of the Protestant classes for Ireland to remain a part of the United Kingdom and they, therefore, mostly identified as unionists.

6 Catholics, on the other hand, were more likely to be Irish nationalists, supporting independence from Britain. These divisions, along with Britain’s interest in maintaining a grip on its Irish colony, would lead to successive conflicts from the Easter Rising in 1916 through the Irish War of Independence (1919–1921), the Irish Civil War (1922–1923), and the Northern Irish “Troubles” (1968–1998). The divisions endure to this day.

7 All this is to explain that while, a great number of Irishmen fought and died in the First World War, the meaning of the term “Irishmen” is debatable. What is certain is that soldiers from the island of Ireland made up a significant portion of the British Army at the outbreak of the war, and that more joined in successive, targeted recruiting campaigns. In total, historian

Fitzpatrick (

1996) estimates “Ireland’s aggregate male contribution to the wartime forces was about 210,000” (p. 388). However, history had conspired so that Protestants/unionists and Catholics/nationalists had wildly different motivations for joining the war effort.

Two groups of “volunteers” were at the center of army recruitment in Ireland, although neither of them had anything to do with the conflict in continental Europe. The introduction of a 1912 Irish Home Rule bill in the British Parliament had angered and frightened unionists—particularly in the north of Ireland, the province known as Ulster.

8 Fearing that Irish Home Rule would make them a cultural and religious minority in the nation, some of them swore to take up arms rather than submit to a Dublin-based parliament. Thus, the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF)

9 was born (

Ferriter 2004, pp. 117–22). Alarmed by the arming of their political opponents, the nationalist Irish Volunteers were formed shortly thereafter (

Ferriter 2004, p. 122). At the onset of the war in July 1914, the leaders of

both groups encouraged their members to enlist and support the war effort.

Fitzpatrick (

1996) explains:

The political leaders of both volunteer forces (Sir Edward Carson [UVF] and John Redmond [Irish Volunteers]) found common cause with the Allies in a fight which each expected to bring political benefits. For Redmond … Irish participation in the war promised the reward of early Home Rule; while Carson saw an opportunity to strengthen Ulster’s case for exclusion by demonstrating that Ulster loyalism was more than a rhetorical figment.

(p. 386)

If these rationales seem confusing and contradictory, that is because they were. In

A Long Long Way, the situation is described succinctly as “a veritable tornado of volunteers” (

Barry 2005, p. 95).

In hindsight, it is easier to understand the unionist rationale for supporting the war effort, but this historical perspective is shaped by almost a century of political propaganda on both sides. At the time, the leader of the Irish Volunteers, John Redmond, was firm in his beliefs and persuasive in his appeals for Irish Volunteers to join the British Army. His most famous recruiting speech was given in the town of Woodenbridge in September of 1914. In it, Redmond claimed:

This war is undertaken in the defence [sic] of the highest principles of religion and morality and right, and it would be a disgrace forever to our country, and a reproach to her manhood, and a denial of the lessons of our history, if young Ireland confined her efforts to remaining at home to defend the shores of Ireland from an unlikely invasion and to shrink from the duty of approval on the field of battle of that gallantry and courage which has distinguished our race through its history.

Redmond’s so-called “Woodenbridge Speech” “led directly to a split between moderate and advanced nationalists in the Volunteer ranks” (

Foster 1988, pp. 472–73). As

Jackson (

2003) notes, Redmond may have been making “a reciprocal gesture” to the British government that would shortly (he believed) grant Home Rule, but he “succeeded only in encouraging thousands of his followers to march to their deaths” (p. 173). But Redmond’s stance was, at the time, a popular one. Much more popular, for example than those in favor of open rebellion: “the total number of insurgents (perhaps 1500) [in the Easter Rising] underlines the extent to which militant separatism was a marginal phenomenon in Irish society; there were, by way of contrast, over 150,000 men in the Redmondite National Volunteers” (

Jackson 2003, p. 173).

Furthermore, Redmond’s call-to-arms was not the only reason that Irish nationalists would have been drawn to the war effort (see

Figure 1). Pro-war propaganda framed the conflict as being fought to defend the rights of small nations (particularly Belgium, which was majority Catholic), which made it a natural parallel for the Irish nationalist cause (

Peatfield 2018). This point of view was aided by British recruiting campaigns that emphasized atrocities being committed against Belgian civilians (

Tierney et al. 1988, p. 49).

The organization of the British Army reflected the political divisions of the new Irish recruits, at least to a degree. The 36th (Ulster) Division was made up almost entirely of Ulster Volunteers, while the 16th Division contained a large number of Irish Volunteers (

Fitzpatrick 1996, pp. 390–91). These Irish divisions were involved in some of the most famous and bloody battles of the war. Most notable among these is the Somme, in which the 36th (Ulster) Division lost 2000 men in a single day (

Pheonix 2016). The 16th (Irish) Division suffered similarly heavy losses at the related battles of Guillemont and Guinchy (

The Somme Association 2019a). In the summer of 1917, the 16th and 36th Divisions fought side-by-side and succeeded in taking the village of Wytschaete. This might be the closest the war came to providing for the hopes of many, including John Redmond, that nationalists and unionists fighting side-by-side might be encouraged to resolve their differences (

Callinan 2014). Both divisions suffered such heavy casualties, however, that they were withdrawn and reconstituted in the spring of 1918 and were virtually unrecognizable by the end of the war (

The Somme Association 2019b).

As political divisions persisted in 20th-century Ireland, so did the divided legacy of the war. From the unionist perspective, the First World War was fought as a defense of the British Empire and, by extension, of the union between Britain and Ireland. In unionist traditions the war, and particularly the “blood sacrifice” of the 36th Division at the Somme “came to represent … a conclusive demonstration of Ulster’s unshakeable loyalty to the Union” (

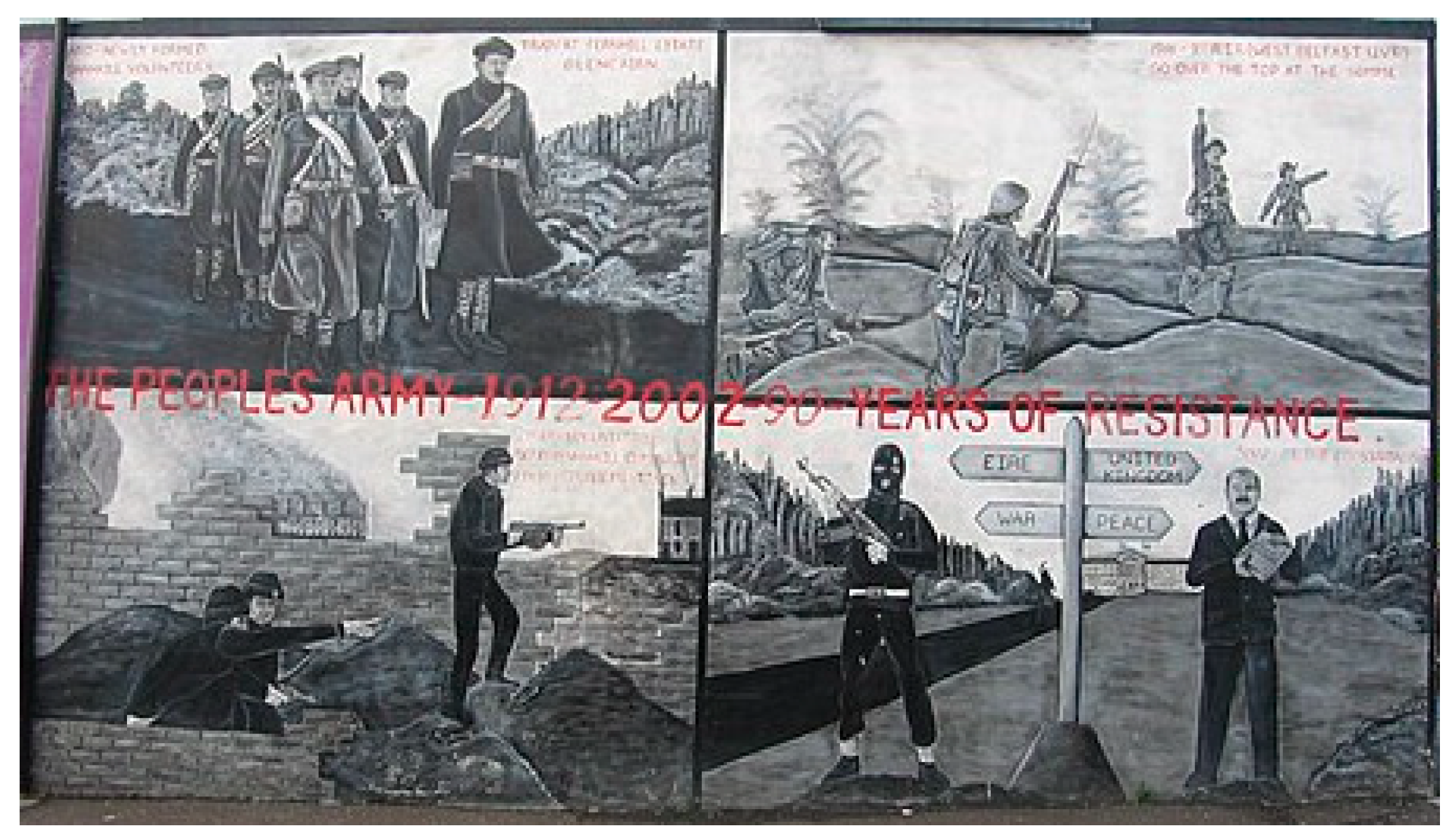

First World War 1998, p. 205) and is a popular subject for murals (see

Figure 2). In what

Foster (

1988) calls “a policy of intentional amnesia,” however, the First World War is largely absent, from Irish nationalist historiographies. While it is understandable that the Easter Rising and the subsequent War of Independence and Civil War would eclipse the Great War in Irish history, the fact remains that thousands of Irish nationalists fought and died with the British Army and believed that they were doing so for their country. Thomas Kettle, an Irish Volunteer, Member of Parliament (MP), and lieutenant in the British Army, predicted their fate. In the wake of the Easter Rising, he reportedly told a friend: “these men [the 1916 leaders] will go down to history as heroes and martyrs and I will go down—if I go down at all—as a bloody British soldier” (

Mulhall 2019). Kettle was killed in action a few months later.

3. Irish Historical Fiction and Sebastian Barry

In the introduction to his work on contemporary Irish historical fiction,

Haunted Historiographies: the Rhetoric of Ideology in Postcolonial Irish Fiction, Matthew Schulz quotes a 2008 interview with Sebastian Barry: “The fact is we are missing so many threads of our story that the tapestry of Irish life cannot but fall apart. There is nothing to hold it together” (qtd. in

Schultz 2014, p. 5).

Schultz (

2014) uses this quote to argue that questions of Irish identity, historical and otherwise, have shifted from “a debate about the necessary or unnecessary homogeneity of Irish civilization to a program that establishes ambiguity as one crucial characteristic of Irishness in the twenty-first century” (p. 5). If one accepts Schultz’s argument, then Sebastian Barry might be considered the poster boy for a version of Irishness that is defined by ambiguity.

Since he first rose to prominence with his 1995 play,

The Steward of Christendom, Barry has been known for examining the “forgotten” experiences of 20th-century Irish history in his fiction. Barry’s eight novels and 14 plays draw on his own family’s history to tell a series of interlocking stories.

A Long Long Way is no exception to this pattern. Willie Dunne, the novel’s protagonist, is the son of Thomas Dunne, the principal character in

The Steward of Christendom. Two of Willie’s sisters—Annie and Lilly—also feature in their own novels:

Annie Dunne (2002) and

On Canaan’s Side (2011), respectively. Together, Barry’s works of historical fiction create something like an imaginary archive that seeks to fill in holes in his own family history, and—by extension—the history of his country:

I grew up with people, particularly my father, who weren’t interested in history or the sense of the end of history. I mean it was understandable because they’d been through all these wars, even vicariously, in the 20th century, starting with 1916, which his father, my grandfather, had been in. But to me it mattered because there were other things thrown in my way as well, like my other grandfather being in the British army. So there were complications that needed to be worked out.

In “working out” these complications, Barry creates his own version of this history, albeit, one that is based in fiction. The body of his work acts as a kind of meta-version of Suzanne Keen’s notion of the “romance of the archive.” Keen describes the process this way: “The central romance of the archive … lies in the recovery or re-discovery of the ‘truth,’ a quasi-historical truth that makes sense of confusion, resolves mystery, permits satisfying closure, and, most importantly, can be located” (

Keen 2001 p. 15). While most of Barry’s body of work does not fall into the exact category of novels that Keen discusses, it is hard not to see his literary project as related, in the sense that his novels seek to fill in the gaps—those “missing threads”—of Irish history.

Barry consistently frames his goal in telling these stories as a personal one but, of course, he cannot avoid the political implications of interpreting history. As Robert

Holton (

1994) notes:

History is a story that is not solely concerned with time and events: in its representations of those times and events, it functions as a powerful form of self-representation and self-definition. Indeed, it is through such shared narratives that the social identity of communities is constituted, both positively (by inclusion) and negatively (through exclusion or demonisation, for example).

For this reason,

Holton (

1994) argues, the line between narratives of history and historical fiction are not as distinct as some might prefer:

the similarity of the mediating roles played by concepts such as intentionality and point of view in the discussion of the writing both of history as narrative and of narrative fiction tends to work against the absolute separation of these two genres … both seek to construct coherent narrative representations of events.

(p. 11)

While Barry does not present his novels as historical fact or “truth,” by retelling and re-interpreting Irish historical narratives, he is still entering into a longstanding and contentious debate.

To give a painfully reductive summary, Irish historical narratives fall into two broadly-defined camps: nationalist and revisionist. Nationalist historians tend to approach Irish history from a postcolonial perspective. Their work is “nationalist” insofar as it interprets centuries of violence, rebellion, and disaster as leading, ultimately, to the formation of the Irish Free State/Republic of Ireland. While many Irish nationalist historians and critics are skeptical of present-day Irish politics, their approach to Irish history tends to emphasize the radical potential in the fight against British colonial rule. Attempts to articulate an “Irish” national literature means that many contemporary literary critics fall into the nationalist camp. One of the most prominent of these is Declan Kibered, whose seminal book Inventing Ireland, traces the development of a literary and historical “Irish” identity from the 16th century onwards.

Many Irish revisionist historians would characterize the nationalist approach as, at best, naïvely poetic and at worst, dangerously sectarian.

10 Revisionists tend to emphasize the incongruities of historically “Irish” identities, and point out that the white, English-speaking, Western European nation of Ireland has little in common with Britain’s other former colonies. Revisionists often benefit from meticulous historical research and see their work as driven by facts rather than ideology. However, they are also, in the words of

Cullingford (

2001), “sometimes less aware of the interests served by their own ostensibly factual narratives” (p. 1).

Barry does not really fit neatly into either side of this debate. His novels riff off major events of the nationalist version of history—especially the 1916 Easter Rising, the Irish War of Independence, and the Civil War. But they also follow characters that are usually ignored or vilified by committed nationalists—loyalist Catholics, apolitical emigrants, soldiers in the British Army. For this reason, some nationalists have taken issue with the viewpoints represented by some of his characters. Kiberd, for example, generally praised

Annie Dunne in a 2002 review, but also suggested rather tartly that the novel was weakest it attempted to “appeal to that herd of independent minds which believes that it is a holy and wholesome thing to dismantle the narrative of nationalism” (

Kiberd 2002). But, in general, Barry’s progressive humanist politics and well-crafted literary stylings mean that he is generally embraced by the Irish establishment: so much so, in fact, that in 2018 he was appointed as the Republic of Ireland’s second-ever Laureate for Irish Fiction (

Doyle 2018).

4. A Long Long Way

With this background in mind, it seems almost inevitable that Barry would take an Irish experience of the First World War as a subject for a novel. In fact, the seeds of

A Long Long Way were planted early in his canon: Willie Dunne first appears (as a ghost) in

The Steward of Christendom.

A Long Long Way itself takes place between 1914 and 1918 and follows Willie Dunne through his experiences as a member of the 16th Irish Division of the British Army. Published in 2005,

A Long Long Way was well-received by critics and was shortlisted for the prestigious Man Booker Prize. Reviews of the novel tend to either paint the story as a corrective re-telling of the forgotten history of Irish soldiers in the First World War or as a Great War novel with an “Irish” twist.

A Long Long Way is both these things. It is also, as

Badin (

2015) writes, one of Barry’s most traditional (which is to say, least postmodern) works of historical fiction.

That said,

A Long Long Way is also one of Barry’s most sympathetic treatments of Irish nationalism. While from Willie’s perspective the Easter Rising is, in the terms of

Briggs (

2017), “carnage and confusion,” its actual purpose is not disavowed in the text. In fact, however chaotic and ill-conceived it may appear, the Rising is violence in service of a defined goal; therefore, it contrasts starkly with the “carnage and confusion” of the trenches, which is mechanized, anonymous, and serves no clear purpose. Over the course of the novel, Willie is traumatized by both types of violence, but while the violence of the trenches leaves him shell-shocked and numb, the Rising provides the catalyst for something like a political awakening. Finding his Irish–English–Loyalist–Catholic identity untenable and understanding that he is on the wrong side of Irish history, Willie nevertheless ends the novel as a reluctant nationalist. It is the contrast between the violence of the Easter Rising and Willie’s experience in the trenches that, in my view, makes

A Long Long Way Barry’s most nuanced take on Irish nation building.

5. Conflicting and Converging Identities

Like many of Barry’s protagonists, Willie is born into a family of complex loyalties. The Dunnes are “Castle Catholics”;

11 Thomas Dunne, Willie’s father, is the chief superintendent of the Dublin Metropolitan Police (DMP). Despite the religious discrimination that he faces—he has “risen as high as a Catholic could go” (

Barry 1998, p. 44) in the DMP—Thomas is fiercely loyal to the Victorian ideals of the Protestant Ascendency and, more broadly, the entire British Empire. The contradictions of Thomas’s identity are magnified in his son. The seeds of an identity crisis are sown into Willie Dunne’s very name. The surname, Dunne, is Irish in origin. It is a derivative of the O’Duinn, a clan which was known to be “hostile to English interest” (

Neafsey 2002, p. 6) in the 16th century. Willie’s first name, however, comes from “the long-dead Orange King” (

Barry 2005, p. 3) William of Orange (William III of England), who cemented England’s Protestant rule in the late 17th century.

12 Throughout Willie’s short life, events conspire to draw out these conflicting identities. He falls in love with the working-class daughter of one of the strikers his father injured during the DMP’s violent dispersal of the 1913 Dublin Lockout.

13 He joins the British Army, but finds himself unable to shoot when fighting the rebels during the Easter Rising. By the end of the book, he is literally branded with the symbols of both England and Ireland: an explosion burns the imprint of a fellow soldier’s medal into his chest, leaving a mark in the shape of “a little harp and a little crown” (

Barry 2005, p. 276).

At the beginning of the novel, Willie looks up to his father both figuratively and literally and hopes to deal with these conflicting identities in the same way that Thomas does. But Willie is barred from joining the DMP by his height, which will “never reach six feet, the regulation height for a recruit” (

Barry 2005, p. 6) and his decision to enlist is motivated by the less-restrictive requirements for the army. Willie signs up at the recruiting office, “his height never in question” and is satisfied to find that “if he could not be a policeman, he could be a soldier” (

Barry 2005, p. 15).

Even beyond the more lax height restriction, joining an Irish division of the British Army seems like one possible way for Willie to reconcile his conflicting identities. The outbreak of the war gives Willie the opportunity to be part of a global movement:

Why, he [Willie] read in the newspaper that men who spoke only Gallic came down to the lowlands of Scotland to enlist, men of the Aran Islands that spoke only their native Irish rowed over to Galway. Public schoolboys from Winchester and Marlborough, boys of the Catholic University School and Belvedere and Blackrock College in Dublin. High-toned critics of Home Rule from the rainy Ulster countries, and Catholic men of the South alarmed for Belgian nun and child. Recruiting sergeants of all the British world wrote down names in a hundred languages, a thousand dialects. Swahili, Urdu, Irish, Bantu, the click languages of the Bushmen, Cantonese, Australian, Arabic.

At the beginning of the war, the unification of the empire against a common enemy papers over the “deep, dark maze of intentions” (

Barry 2005, p. 15) of those who have enlisted. These men also find a unified soldierly identity that, significantly, takes “A Long Way to Tipperary” as its anthem: “every man Jack of them knew ‘Tipperary’ and sang it as if most of them weren’t city-boys but hailed from the verdant fields of that country.

14 Probably every man in the army knew it, whether he was from Aberdeen or Lahore. Even the coolies sang ‘Tipperary’ while they dug: Willie had heard them” (

Barry 2005, p. 57). For Willie, who is at this point entirely apolitical, blending into this mass of humanity seems like it might allow for a reconciliation of his own polarized identities.

Over the course of the novel, several characters express hope that the war might lead to unity within Ireland as well.

15 Father Buckley is the most vocal proponent of this view. He hopes that “Nationalist and Unionist Irish soldiers fighting side by side might some day foment a greater understanding of each other and bring Ireland in spite of the recent rebellion to a place of balance” (

Barry 2005, p. 195). At certain points in the novel, this possibility seems like it might be realized. Barry describes a friendly animosity between unionist and nationalist soldiers, writing that they “liked to trade insults with each other when they passed by chance on the road, or fetched up in billets near each other” (

Barry 2005, p. 144). Under the right circumstances, this animosity can turn into something like camaraderie, like it does after the victory at Guinchy. The 16th Irish Division has secured victory at that town, and Christy Moran describes their reception by the 36th Ulster Division: “And those devious Ulster lads from the 36th milling about and calling us wonderful fucking Paddies, that’s what they said, and shaking our hands” (

Barry 2005, p. 225).

The clearest expression of this uneasy unity, though, comes in an inter-regimental boxing tournament, which pits “a Belfast man called William Beatty” against “a tall bleak-faced hero called Miko Cuddy” (

Barry 2005, p. 191). The match takes place sometime in the fall of 1916, and “the recent trouble in Dublin” (

Barry 2005, p. 195) is certainly on everyone’s mind. However, it is more significant to the proceedings that this “Battle of the Micks” (

Barry 2005, p. 191) takes place shortly after the Battle of the Somme. The sectarian competition, which might have been life-or-death in a different context, is termed “unobjectionable” (

Barry 2005, p. 191) by Father Buckley: “by which he meant it wasn’t an engagement in the field of death and therefore no one would get killed by machine-gun or shrapnel bomb” (

Barry 2005, p. 191). Indeed, the fight ends up being (mostly) a fair and even match, with the two competitors treating each other as fellow sportsmen. But the match does nothing to actually solve partisan divisions. Instead, it merely downgrades them to a form of entertainment. The spectators of the boxing match view it as a “great spectacle” (

Barry 2005, p. 190) not because it will have any effect on the future of their nation, but because it provides a momentary distraction from the coming winter, which will bring only “suffering in the raw ditches of that world” (

Barry 2005, p. 191). The common identity of the men at this point comes from suffering, not idealism. After enduring gas attacks, constant bombings, and utterly random violence perpetrated by an unseen, anonymous enemy, the men find relief in a small-scale, clear-cut conflict between two of their own.

But trauma, Barry will show, is not stable ground on which to build an identity, particularly when there is no clear rationale behind the suffering. Although it is nominally a victory, Willie’s experience at the Guinchy and Guillemont is one of his most traumatic: “at least four men of their platoon were gone, and maybe two thirds of the company, and maybe half the battalion was dead, and another third terribly wounded … The field hospital couldn’t manage the deluge of grief and distress. The world was distressed into a thousand pieces” (

Barry 2005, p. 186). Guinchy itself, the village that has been won, is “only a stretch of flattened ground with some light white patches were bricks and mortar of houses had long since been pulverized” (

Barry 2005, p. 185). This victory that bonds the soldiers is hollow; its only lasting impact is trauma.

6. Easter, 1916

In contrast to the battle at Guinchy, the Easter Rising was a short-term disaster but a long-term victory. In

A Long Long Way, Willie witnesses the Easter Rising firsthand, and the personal and political consequences of this experience reverberate throughout the novel. Although Willie witnesses “a thousand deaths” (

Barry 2005, p. 246) over the course of the novel, the Rising is the first time that he connects death with a political purpose.

Willie is in Dublin when the Easter Rising breaks out, on his way back to the front from his first furlough. The violence in his home city is startling and confusing, and Willie thinks at first that the Germans have invaded Ireland. When told to step away from “the enemy” (a man handing out copies of the Proclamation), Willie responds “What enemy?” (

Barry 2005, p. 88) and when told that the proclamation is addressed to “the people,” he asks “What people?” (

Barry 2005, p. 90). A political innocent, Willie has no knowledge of the unrest that has been brewing in his native city, and when the Rising brings it to a head, his world is turned, suddenly and bafflingly, upside down. Familiar household items become tools of war as the company builds a barricade out of furniture from nearby houses. Familiar places, like “the intersection of the canal and the Ballsbridge road” (

Barry 2005, p. 91) have suddenly become battlefields. Familiar people have become “the enemy.”

In the midst of this turmoil, Willie finds himself face-to-face with a rebel soldier, “a shivering man, a very young shivering man in a Sunday suit and a sort of military hat” (

Barry 2005, p. 92). The soldier attempts to take Willie captive, but is fatally injured by a shot from Willie’s captain. Unwilling to shoot the man himself, and feeling that “it would be heartless not to attend to the man in some fashion” (

Barry 2005, p. 92), Willie kneels beside the rebel as he dies. As Willie watches the man’s blood stream across the familiar street, the soldier insists that he is “An Irishman … fighting for Ireland” (

Barry 2005, p. 92) and says his act of contrition. Two full pages of description are devoted to the rebel’s death, and Willie will literally carry “the young man’s blood to Belgium on his uniform” (

Barry 2005, p. 97). This experience is sharply contrasted with his confrontation of another enemy, just a few pages later. Thrown into hand-to-hand combat with a German soldier, Willie sees the man as “a grey monster in a mask” and imagines him as an enemy invader: “He stood over Willie and all Willie could think of were Vikings, wild Vikings sacking an Irish town” (

Barry 2005, p. 113). The German is only humanized after his death through the family pictures and trinkets in his pockets, and Willie never wonders at his motivations for coming to the war.

The Rising, on the other hand, is (literally) something to write home about. In a letter to his father, Willie expresses sympathy for the executed 1916 leaders and the young man whom he watched die: “

When I came through Dublin I saw a young lad killed in a doorway, a rebel he was, and I felt pity for him. He was no older than myself. I wish they had not seen fit to shoot the three leaders” (

Barry 2005, p. 139). Thomas sees his son’s sympathy for the nationalist cause as a personal affront and when Willie is next home on furlough, he accuses him of betraying the family legacy:

Now, that they might have killed me at the gates of St. Stephen’s Green, that that demon woman Markievicz might have marched up and shot her bullet into my breast and taken this life out of me, before I had to open a bitter letter and read those bitter words and feel the bitter bile loosen in the very centre of my body, so that I was crying in the darkness, crying in the darkness, for a fool and a forsaken father!

Thomas is particularly enraged because of the death of “one of [his] recruits” (

Barry 2005, p. 246), presumably the historical Constable Michael Lahiff, who was shot during the Rising near St. Stephen’s Green and later died of his wounds.

16 Willie, however, cannot muster outrage at this act of violence. Within the scene, he is described as “a man of five foot six who had seen a thousand deaths” (

Barry 2005, p. 246). Trauma and disillusionment make it impossible for Willie to argue with his father in this instance; he simply turns and goes “back down the worn stairs and out in to the gathering dark” (

Barry 2005, p. 248).

The key to Willie’s change of heart, however, is not just the Rising. Instead, it is another death that he witnesses at the front, although not in anything like a battle. Jesse Kirwan

17 is an Irish Volunteer who has enlisted in the war effort because of John Redmond’s appeals. Jesse has not yet seen the war when Willie meets him in Dublin, both of them on their way to the front, but he is well-versed in Irish politics. It is Jesse who explains the Proclamation of the Irish Republic to Willie, along with the reasons for and implications of the Rising.

Jesse is a tragic figure from the beginning. As the soldiers rally behind their barricade in order to fire on the General Post Office, Jesse huddles with a copy of the Proclamation, “intently weeping” (

Barry 2005, p. 90). Later, at the front and after the leaders of the Rising have been executed, Jesse undertakes a silent protest and hunger strike.

18 When Willie is called to his side, he explains his reasoning: “an Irishman can’t fight this war now. Not after those lads being executed … I won’t serve in the uniform that lads wore when they shot those others [sic] lads” (

Barry 2005, p. 155). He is not eating, he says, “so I can shrink, and not to be touching the cloth of this uniform, you know? I am trying to disappear, I suppose” (

Barry 2005, p. 155). The result of the Rising is that Jesse has come to see his own self-concept—as an Irishman fighting in the British Army—as untenable. Ironically, in the midst of so much bloodshed and mayhem, Jesse’s desire for self-annihilation represents the ultimate act of treason, and he is court-martialed and executed. Willie manages to be part of the burial detail and the text explains that, ultimately, Jesse got his final wish: “that earth [where Jesse is buried] would be disturbed four or five times in the coming years. Jesse Kirwan would be blown out of his resting-place and scattered across the bombed earth, blown and scattered again, till every morsel of him was entirely atomized and defunct” (

Barry 2005, p. 161). At the time, Willie does not understand Jesse’s decision, and he wonders “what in the world was the matter with [Jesse] that he refused to obey orders?” (

Barry 2005, p. 149).

By the end of the novel, though, Willie is faced with his own marginalization as an Irishman within the British army and as a British soldier in Ireland. Having lost his family, his sweetheart, and any other sense of his identity, Willie finally decides that Jesse may have been on to something after all: “Finally, the words of Jesse Kirwan had penetrated deep into the sap of his brain and he understood them. All sorts of Irelands were no more, and he didn’t know what Ireland there was behind him now” (

Barry 2005, p. 286). But Willie, knowing the war is almost over, decides he will seek knowledge rather than death: “No, he did not understand Jesse Kirwan entirely, but he would seek to in the coming years, he told himself. At least in the upshot he would try to know that philosophy” (

Barry 2005, p. 287). “That philosophy” is, presumably, the nationalism that led Jesse to join the British army in the first place and that, ultimately, led to his death at its hands. But Willie’s path to this understanding will not be clear:

But how would he live and breathe? How would he love and live? How would any of them? … How could a fella like Willie hold England and Ireland equally in his heart, like this father before him, like his father’s father, and his father’s fathers’ father, when both now would call him a traitor, though his heart was clear and pure, as pure as a heart can be after three years of slaughter.

The answer, of course, is that Willie cannot “hold England and Ireland equally in his heart,” even though he has been branded with the symbols of each nation.

7. An Inclusive Nationalism

Ultimately,

A Long Long Way represents an argument for a more inclusive Irish national identity. This argument is neither particularly new nor particularly controversial in Irish literary circles, but what is provocative about this novel in particular is the way it locates the possibility of this new identity in

both the Easter Rising

and the First World War. The Easter Rising and the Proclamation issued therein is a well-accepted focal point for nationalists arguing against the religious and social conservatism of the Irish Free State. For such scholars, “the execution of James Connolly and the defeat of the anti-Treaty Republicans in the Civil War meant the extinction of the socialist, feminist, and non-sectarian possibilities inherent in the Proclamation of the Republic” (

Cullingford 2001, p. 2). Willie’s slow acceptance of nationalism hints at the Rising as a source of such possibilities, but the ending of the novel also illustrates the ways in which the war creates an Irish community that crosses social, economic, and political barriers.

While the last few months of Willie’s life are filled with bitterness and pain, they do contain a glimpse of what such a nation might look like. Alone on his second furlough, having been exiled from his family, Willie makes his way to the home of his first captain—Captain Pasley. Pasley came from a family of land-owning farmers in County Wicklow, near the place where Willie’s father was raised. Willie had regarded Pasley as a good captain, closely connected with the land and well-suited for leadership: “he had an air of confidence, which was a good air when you were all stuck out in foreign fields, and even the birds did not sing the same run of notes” (

Barry 2005, p. 32). Pasley respected his men and bonded with them over their shared homesickness, worrying over the work, and particularly the “liming of the fields” (

Barry 2005, p. 32) that his father will have to do in his absence. But Pasley’s confidence and honor were of no use against the ravages of 20th century warfare. He was killed in the first gas attack on his platoon after he (both nobly and foolishly) insisted on “hold[ing] the fort” (

Barry 2005, p. 46) as his men fell back in retreat.

In a world of strict divisions, Willie’s religion and class should separate him politically from the Pasleys,

19 but as he moves towards his former captain’s estate, he finds these barriers breaking down. He meets the rector of the local Protestant church, who registers that Willie’s name is “unlikely to be a Protestant one” (

Barry 2005, p. 356) but nonetheless gives him polite directions. Arriving at the house, Willie has “enough sense” (

Barry 2005, p. 256) not to go to the grand front door, and instead knocks at the servants’ entrance to the kitchen. He first assumes that the woman who answers the door is the cook, but later realizes that it is Mrs. Pasley herself. Even Willie’s conceptions of the roles the two of them ought to play in regard to mourning, too, are overturned: “He had come, he had thought, to comfort the captain’s parents. How could there be comfort in a fool sitting in the kitchen with his tongue tied and his heart scalded?” (

Barry 2005, p. 259). These characters gather together as Ireland is on the cusp of nationhood, united by the shared trauma and grief wrought by an entirely different conflict. They will all, ultimately, be left out of official versions of nationalist history, but this brief moment demonstrates the possibility of a different kind of national community—one that is only made possible by the war.

Barry’s protagonists tend to be victims of the process of Irish nation-building. In

On Canaan’s Side, for example, Willie’s sister Lilly Dunne spends most of her life fleeing the political consequences of her husband’s involvement with the Black and Tans.

20 Thomas Dunne, though more unsympathetic than either Willie or Lilly, eventually goes mad in an Ireland that no longer has a place for him. But

A Long Long Way does not completely fit this pattern. Willie is a victim of

both the mass, anonymized violence of the First World War

and the consolidation of an “Irish” identity around the sacrifice of the 1916 rebels. At the same time, Barry represents new possibilities as inherent in both these disruptions, and so he complicates but does not debunk the founding myth of Irish nationhood. While Willie does die tragically in the last days of the fighting, Barry’s representation of his story suggests a new and more complex approach to a painful point in Irish history.