1. Introduction

On 24 October 1967, a helicopter carrying France’s president, Charles de Gaulle, landed on the shores of the Etang de l’Or, one of the many brackish lagoons that punctuate the Mediterranean coast of France west of the Rhone Delta. De Gaulle had come there to visit the construction site of La Grande Motte, a new tourist town slowly taking shape on the coast of the Gulf du Lion. La Grande Motte was the destination of a flight that took de Gaulle over 200 km of the coast where other similar settlements were taking shape (Le Monde, 25 October 1967). The creation of these new towns was the culmination of action undertaken by the Mission pour l’aménagement touristique du littoral du Languedoc Roussillon, a special regional planning program aimed at redeveloping the scarcely populated littoral of the Languedoc-Roussillon region into a major tourist destination. The redevelopment plan entailed extensive modification of the coastline via the construction of leisure ports and artificial bays and the urbanization of large areas, but also eradication of mosquitoes and reforestation of selected sites.

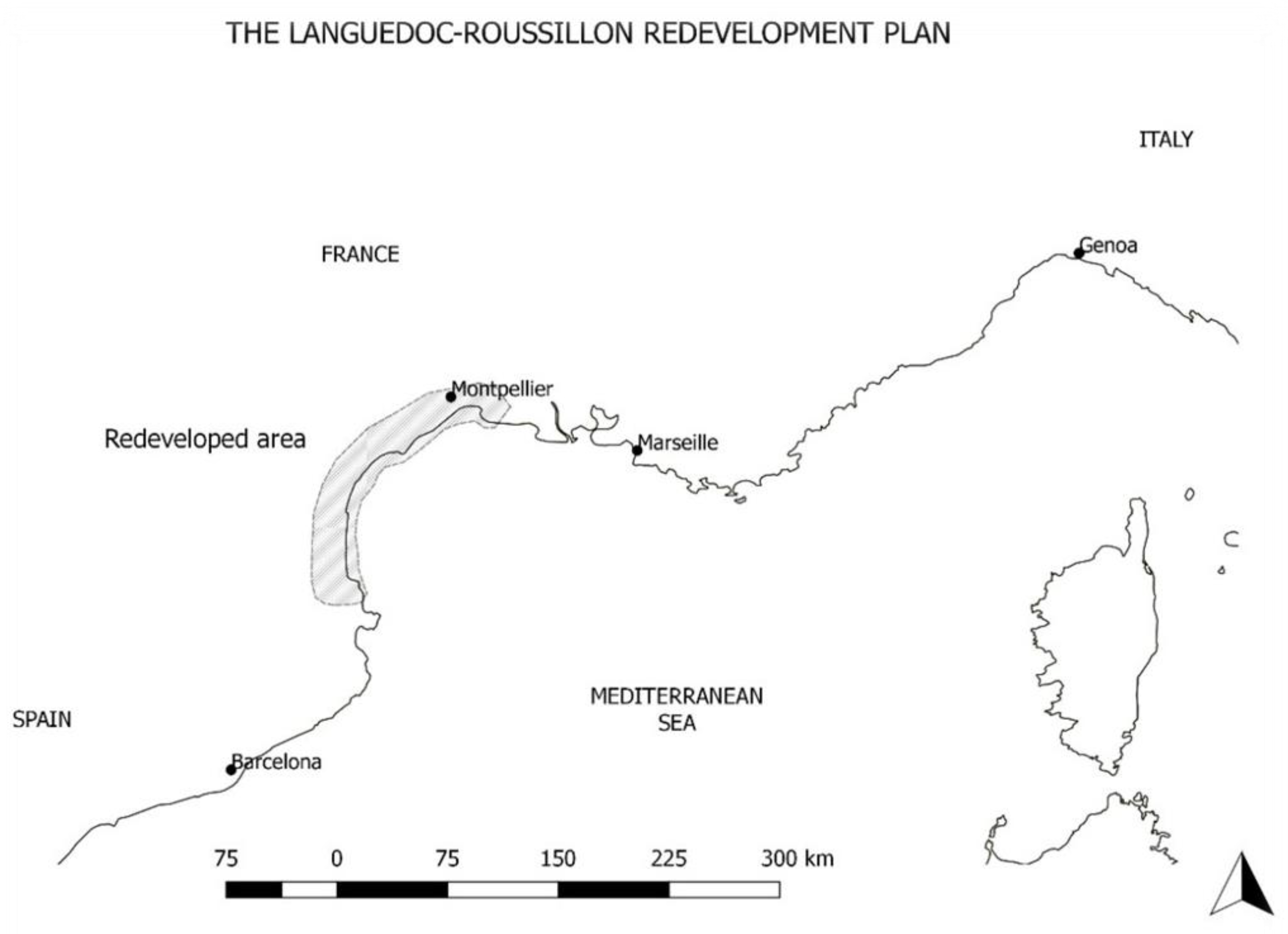

This article reviews this complex case of regional planning from a historical perspective, bringing into focus its roots, unfolding, and environmental consequences on the coastal interface, with the ultimate aim of encouraging further comparative analysis. This case is particularly interesting on at least four counts. The first reason is its scale: the redevelopment plan covered the entirety of the coast of Languedoc-Roussillon, which spans from the Rhone Delta to the French–Spanish border for more than 100 km (see

Figure 1). Second, this very large-scale plan was also highly centralized. Funding came entirely from the French state and state officers directly led the redevelopment operation via a new type of administrative tool, the interministerial “mission.” Thirdly, this centralized, large-scale regional planning initiative was devoted explicitly to the promotion of littoral tourism: the planners saw tourism as the best development opportunity for this region and directed all the resources to this aim. Finally, this centralized, large-scale regional planning initiative for seaside tourism entailed an extremely ambitious and complex set of physical interventions on the coastal interface. These interventions involved infrastructure (including new roads, ports, and airports), settlement (expansion of existing towns and creation of new towns), and the littoral environment (drainage, filling, reforestation, and mosquitos’ eradication).

Building on this literature, this paper aims to explore further the historical role of public policy in tourism development of the coast by focusing on the accelerated, state-driven coastal redevelopment of Languedoc-Roussillon, which is also a prime example of postwar regional planning in France. Through the historical analysis of this complex case, we wish to contribute to the historical assessment of regional planning for tourism by emphasizing three points. First, echoing other studies of this case (

Furlough and Wakeman 2001), we argue that regional planning actors worked in cooperation with local actors. While the state officers who led the Mission Racine played a crucial and undeniable role in remaking the Languedoc-Roussillon seaside, they adopted ideas and plans developed by local political players and collaborated with them to define and implement the Mission’s objectives. Second, the tourism-centered redevelopment of Languedoc-Roussillon promoted by the regional planners was rooted in pre-existing forms of coastal tourism. The coast of Languedoc-Roussillon, far from being the desolated wilderness that the regional planners described in their documents, had been experiencing local and unplanned forms of coastal tourism at least since the early 20th century. This long history of coastal tourism was an important factor in the success of the Mission Racine. Finally, regional planning in Languedoc-Roussillon had an interesting if ambivalent approach to the protection of the coastal environment. Pierre Racine, the leader of the Mission, presented the redevelopment plan as a model for an environmentally friendly coastal tourism development, one in which the need for new settlements and infrastructure was balanced by the establishment of protected areas and reforestation. The record of the Mission on this count, however, is less clear and incontestable than the rhetoric of Pierre Racine reveals.

The remainder of this paper is structured in four sections.

Section 2 presents in more detail the Mission Racine, its creation, vision, and functioning.

Section 3 discusses the trajectories of tourism growth and the local attempts at regional planning prior to the Mission.

Section 4 analyzes the outcome of the Mission, with special regard to its environmental impact. The conclusive

Section 5 briefly summarizes the results of this paper and suggests some lines of inquiry for future comparative investigations.

2. The Mission Racine

When de Gaulle visited the construction site of La Grande Motte in 1967, the Inter-Ministerial Mission for the Touristic Redevelopment of Languedoc-Roussillon Littoral was already four years old. The Mission was created on 18 June 1963 and formed by representatives of the ministries of Interior, Finances, Budget, Construction, Public Works, Agriculture, and Tourism. Furthermore, it included prefects of the four departments interested in the redevelopment plan (Hérault, Aude, Pyrénées Orientales, and Gard), plus a number of other experts and political personalities. The number of branches of the public administration involved in this peculiar organization already provides a clue to the magnitude of its ambitions. Its president was Pierre Racine, founder and director of the Ecole Nationale d’Administration (ENA, the National School of Administration) and close collaborator of former Prime Minister Michel Debré. On a regional level, the Mission included two structures: a ‘study service’ to prepare and facilitate decision-making and a town-planning office, in which architects were linked to the Mission by contract (

Arrago 1969).

True to the spirit of postwar regional planning, the Mission’s goal was to boost the economy of Languedoc-Roussillon. A chronically depressed region (

Johnson 1995;

Marty 2013), in the late 1950s Languedoc-Roussillon was experiencing growing problems as a consequence of repeated crises of overproduction in viticulture (the last of which took place during 1953–1957) and the pressure on employment exerted by thousands of recently settled

pieds-noirs, the former colonists who had to flee Algeria after independence. To boost the region’s economy and solve its chronic problems, the Mission Racine sought to transform its littoral into a major tourist destination. The wide, sandy beaches of Languedoc-Roussillon seemed perfect to meet the needs of growing numbers of European tourists looking for sea and sun along the Mediterranean. Moreover, favoring the growth of seaside tourism in Languedoc would have released the pressure on traditional Mediterranean destinations in the Côte d’Azur, while reducing the drain of tourists to neighbouring Spain.

The redevelopment plan was completed and released in 1964. The capacity of Languedoc-Roussillon amounted to 250,000 beds, which the Mission sought to increase to 650,000 beds by 1980 Mission Interministerielle pour l’Aménagement Touristique du Littoral Languedoc-Roussillon (

MIATLLR 1964). Accordingly, the plan included the creation of six new tourist ‘units’: each unit was to host up to 80,000 persons and included the creation of a brand new town (one per unit) and the expansion of existing coastal villages and towns. To meet what seemed to the planners an irresistible trend of growth in private boat ownership, each of the new towns would be equipped with a marina, which would follow the natural features of the coastline to facilitate harbor construction and maintenance (

Pinchon 2007). In total, the Mission planned the construction of 13 new marinas and the expansion of 12 existing ones (

MIATLLR 1964).

A key element of the Mission’s rhetoric was, as mentioned in the introduction, the combination of tourism development and coastal environmental protection. This combination of development and protection was the ultimate justification of planning, as opposed to unregulated coastal growth as experienced in other parts of the Mediterranean. The Mission, therefore, devoted certain areas to urban expansion. Urbanization, however, had to be contained within these pre-established areas. In other portions of the littoral, on the other hand, the Mission envisioned the establishment of protected areas. These protected stretches of littoral were to be kept in a ‘natural’ state (which meant nonurbanized) and, in some cases, reforested in collaboration with the French Forestry Agency (

Saussol 1992;

Andreu-Boussut 2008).

Much of the land-use planning needed to enact such a vision passed through the Plan d’urbanisme d’intérêt régional (PUIR, Urban plan of regional interest). This planning tool established ten different zones, which we can regroup in three categories. First of all, it established urbanization areas in which population density would be drastically limited to 100 beds per hectare or fewer (as in the case of the special ‘priority tourist areas’). Secondly, it established zones to be protected from urbanization or industrialization by classifying them alternatively as ‘natural sites and monuments’, as localized ‘biological protection’ areas of scientific interest, or as areas to be reforested. Finally, zoning was used to confine traditional activities, such as oyster farming or salt harvesting, to their original locations and to concentrate industrial areas around Sète and Port-la-Nouvelle. These zoning measures were an extremely important part of the Mission’s narrative of a planned and harmonious growth. Based on the zoning, and the place that environmental protection had in it, Pierre Racine in his memoires proclaimed the Mission to be the “ecologist before the ecologists”

1 (

Racine 1980, p. 98).

The plan, however, did involve landscape and ecological transformation. The Languedoc-Roussillon coast was an area of brackish lagoons and sand dunes with a very unstable and changeable geomorphology, which required extensive intervention to achieve the stabilization needed by permanent settlements. The ecological features of this humid area, moreover, did not lend themselves well to the massive presence of tourists. Mosquitoes were one of the most pressing concerns, as they were seen by the Mission not only as a health menace but also as a deterrent for tourists. To eradicate or minimize the population of mosquitoes, the Mission, therefore, decided to support the activities of a special body that had been established just a few years previous for that exact purpose: the

Entente interdépartementale pour la démoustication (EID, interdepartmental agreement for mosquito eradication). With the guidance and unprecedented funding provided by the Mission, the EID was charged with erasing mosquitoes from about 55,000 hectares. The EID eradication plan was elaborated with the cooperation of scientists from Florida and Montpellier and was based upon three types of interconnected interventions. The first required the massive use of DDT, sprayed by airplane on areas identified as potential mosquito shelters. The second concerned filling up or draining swamps and lagoons. The third involved the introduction of predatory insects (

Sagnes 2001). These measures, while compatible with the protection of scenic landscapes from the most visible presence of tourism such as buildings and infrastructure, had an obvious and very important ecological impact. Mosquito control was eventually defined as a precondition of tourism (

National Archives 1962).

3. Plans and Trends before the Mission Racine

The Mission Racine was unprecedented, at least for France, and the transformation it envisioned would represent a major turning point in the history of coastal Languedoc. However, in spite of the surrounding rhetoric on innovation and rupture, it is nonetheless possible to identify deeper roots of its action and plans. To begin with, Languedoc was certainly not new to large-scale state plans for economic development via landscape and infrastructure redesign. The endpoint of the monumental Canal du Midi (

Mukerji 2009) and of massive early modern irrigation works, it was also the site that King Louis XIV chose to establish a new Mediterranean port. Sète, the new port city, was built in the middle of a coastal lagoon to be the main outlet for Languedoc agriculture and a driver of economic growth and development for the entire region.

Moreover, as the head of the Mission itself, Pierre Racine remembered, “the idea to profit off of the tourist wealth of Languedoc-Roussillon was not new. It was among the grand plans that Philippe Lamour had imagined since 1935, and Jules Milhau, a man who exerted a profound influence on the region for its whole life, … had studied it” (

Racine 1980, p. 25). Lamour was a former lawyer who settled in Languedoc during the war as a farmer and became president of the Confédération Générale Agricole (CGA, General Agricultural Confederation) (

Dard 2002). Taking as a model the Tennessee Valley Authority in the United States, Lamour promoted in 1955 the establishment of a Compagnie nationale d’aménagement du Bas Rhône Languedoc, of which he would become president and lead the drafting of a Plan d’aménagement du Bas Rhône. Lamour saw water management as the keystone of the economic development of Languedoc. Importantly, he also mentioned “tourist redevelopment of a littoral currently inhabited solely by mosquitoes” as an important element—albeit not the only one—in his vision of development and modernity for Languedoc-Roussillon (Lamour, quoted in

Ruf 2015, p. 8). Jules Milhau, on the other hand, was a professor at the University of Montpellier and founder of the Centre régional de productivité et des études économiques (Regional Centre of Productivity and Economic Studies) during the 1950s. Milhau played a significant role in the elaboration of a program of regional development in Languedoc in 1957 (

Marty 2013, pp. 78–79). These local figures and their ideas were thus an essential source of inspiration for the Mission Racine.

Furthermore, even before the Mission Racine was officially established, some local actors were preparing the terrain for its inception. In that respect, a key figure was Abel Thomas, a state officer who had been appointed as regional commissioner for territorial planning of the Massif Central et Midi in April 1959 (

Sagnes 2001;

Racine 1980). While his role in the creation of the commission has yet to be precisely determined, it is certain that Thomas, in agreement with Minister of Construction Sudreau, planned the acquisition of land on the littoral for tourism development purposes as early as 1959. This acquisition was, in fact, a crucial part of what would later become the action of the Mission itself and was the first of numerous initiatives conceived to prevent speculation in the wake of future redevelopment. In 1961, indeed, the state started to acquire littoral land via the Société centrale pour l’équipement du territoire, an investment fund created in the 1950s in order to support urban planning. Employees of the Compagnie nationale du Bas Rhône Languedoc participated in the early phases of land acquisition (

Andreu-Boussut 2008, p. 66). These activities were then accompanied by the deployment of land-use planning tools developed in the postwar period, through which to ensure the possibility to enact the functional zoning which was at the core of regional planning. The creation of the Mission itself in 1963 was thus in many ways the last moment of a longer process that had started at least 10 years before thanks to the initiative of local actors, and was based on institutions, plans, and tools that were already in place before its establishment.

As the Mission was not a radical innovation from the center, but in many ways the outcome of a longer accumulation of local plans, so the Languedoc littoral prior to the Mission was not a deserted blank space. On the contrary, when the Mission itself was created, tourism was already well established in the littoral. At least 20 tourist settlements existed from the Rhône to the Spanish border. Following a model that could be found all over the northwestern Mediterranean, most of these stations emerged during the 19th century as health resorts (

Sagnes 2001, pp. 29–30). During the 19th century, several hospitals and medical institutions opened sanatoriums in coastal areas, such as the Assistance Publique de Nîmes in Grau du Roi and the Institut Hélio-Marin in Palavas (

Sagnes 2001, p. 31). Most of these stations soon outgrew their original purpose and, from the late 19th century, were colonized by regional residents who could afford to build small, temporary housing along the shore. The creation of new local transport networks, such as tramway lines and the regional railroad, further increased the flow of seasonal tourists to these coastal settlements (

Furlough and Wakeman 2001, p. 352). Taking stock of these well-established processes of growth, moreover, in the aftermath of World War II, regional and national funding agencies had started to fund redevelopment initiatives in several coastal locations. Even in this respect, therefore, the Mission appears to be rooted in a long continuity. The idea of remaking the Languedoc-Roussillon littoral into a seaside paradise for tourists, in sum, was floating around way before the Mission Racine was established. This idea contributed to shaping the Mission Racine itself, through the local actors who contributed to its establishment and redevelopment vision.

4. The Outcomes of the Mission Racine

The deep roots of the Mission Racine provide some important elements to assess the significance and limits of this experiment of regional planning in promoting tourism development. To evaluate significance and limits in full, however, we must also take into account regional planning’s actual results. Regional planners who designed and led the Mission Racine aimed at promoting seaside tourism as an engine for the entire region’s economic development. They also claimed that, through planning, they would have been able to direct and shape the social and environmental changes linked to tourist development, keeping this development within pre-established limits and protecting the coastal environment. The Mission Racine was surely able to expand substantially tourist reception capacities, and as early as 1982, the region welcomed three million tourists (

Andreu-Boussut 2008, p. 89). Second homes and regional tourism were a major part of this growth. In 1975, three homebuyers out of four in La Grande Motte were residents of Languedoc (

Barthèz 1992). Over the years, Languedoc-Roussillon has become the French region with the highest proportion of second homes in the housing stock of littoral municipalities. In the late 20th century, this proportion exceeded 59 per cent (

Zaninetti 2006). Yet the attractiveness of the region is only seasonal, and the Mission was not able to stabilize permanent professional activities. The Mission thus enabled the creation of a ‘tourist rent’ (

Barthèz 1992), but it failed to boost structural economic growth, which was its aim and the goal of the development plans and initiatives that had preceded it.

The Mission did not succeed entirely to control local dynamics and actors, which modified the planners’ original vision. As we have seen, long-term vacationers had created informal settlements of huts on the shoreline. One of the Mission’s priorities, then, was to erase these settlements, which were perceived both as an aesthetic and sanitary nuisance. In some cases, it was proposed that owners of these huts could acquire newly built flats. As early as 1963, regionalist movements contested the Mission, expressing concerns about the potential dispossession of the locals at the hands of Parisian technocrats (

Lafont 1967). In several municipalities, local cabaniers protested against these expulsions, especially at the mouths of the Aude and Bourdigou rivers (

Collectif Bourdigou 1979;

Andreu-Boussut 2008). The Mission responded to these protests by attempting to revise the perimeter of maritime public domain, thereby stopping any possible legal action based on private property rights. These attempts, however, sparked numerous lawsuits. At the beginning, judgements were mostly favourable to the Mission: a 10 July 1964 judgement by the French Conseil d’État (Council of State) defended evictions from the huts by arguing that they were a threat to public health. Yet, in early 1970, the Conseil d’État showed some reluctance towards the extension of the public maritime domain in conflicted coastal areas (Midi Libre, 28 December 1972). Also due to these protests and lawsuits, the Mission was forced to abandon altogether the construction of one of the original six stations (at the mouth of the Aude River).

Finally, the environmental record of the Mission is also mixed at best. Although reforestation was a success story, zoning did not curb overall coastal urbanization. On the shoreline of the Aude department, urbanization grew from 15 per cent in 1963 to 36 per cent in 1983 and more than 40 per cent in 2003 (

Andreu-Boussut 2008). Tourism-led urbanization increased the frequency and impact of a phenomenon locally known as malaïgues. This amounts to a decrease of oxygen in the water and the diffusion of sulphides that lead, in turn, to an increase of fauna and flora mortality during the summer. In the summer of 1975, for example, oyster farming of the Thau pond was troubled by a long period of malaïgue, which caused heavy losses (

Hamon et al. 2003). Finally, tourism-led urbanization significantly increased coastal erosion. Since the post-World War II years, the mayor of Le Grau-du-Roi denounced the increasing erosion of the shore and asked for the state to build dykes (

Ramain Belsamond to the Prefect of Hérault 1962). Over the years, long-standing erosion and the construction of the seaside resort caused siltation in the ports of Grau-du-Roi and La Grande Motte, which, in turn, hampered fishing activities and required consistent investments. In traditional seaside resorts, such as Valras, 1960s urbanization weakened the shoreline. The construction of a pier at the mouth of the Orb River provoked the loss of about 82,000 m

3 of sand from the local beach between 1968 and 1998. Successive attempts to confine the erosion were both expensive and unsuccessful, as breakwaters only led to the displacement (if not the expansion) of erosion (

Durand 2001). These unexpected consequences of redevelopment rendered necessary conspicuous public investment in the artificial stabilization of the shoreline. In 2003, this involved about 32 per cent of the Hérault coast (

Andreu-Boussut 2008). Moreover, the protection regimes envisioned by the Mission as counterbalance to urbanization were not always effectively enforced. The most remarkable case is the Espiguette Cap, in the westernmost section of the Rhone Delta. The Mission had originally envisioned keeping the Cap free from all development, making it the largest protected area of the Languedoc-Roussillon coast. However, only a few years after the beginning of the Mission, the protection plans were lifted to make it possible to build a new pleasance harbor and resort, Port Camargue, which is now the largest marina of the entire littoral of Languedoc-Roussillon (

Sagnes 2001). Finally, the mosquitos eradication program, while not entirely successful, did involve spraying chemicals over much of the littoral, as well as draining and filling lagoons (

Sagnes 2001). Whereas this might have been compatible with preserving landscapes, it can hardly be considered as ecological protection.

5. Conclusions

The Mission Racine was a major experiment of regional planning for tourism development, for the scale, centralization, and complexity of the redevelopment it enacted. While it reveals the historical significance of regional planning in coastal tourism growth, we need to put its origins, workings, and influence into historical context. The Mission Racine was a clear expression of centralizing ambitions of the French state, as well as of the narrative that represented the French province as a “desert” in need of reclamation (

Frost 1985;

Pritchard 2011). However, its actual workings did not exclude interaction and cooperation with local actors. Local actors, as we saw, played a key role in the elaboration of the vision of a regional development based on seaside tourism, as well as in the concrete steps preceding the establishment of the Mission, such as buying coastal real estate to prevent speculation. Moreover, whereas the Mission Racine’s impact on the growth of seaside tourism in Languedoc-Roussillon is evident, and has been highlighted by many authors (i.e.,

Sagnes 2001;

Andreu-Boussut 2008), we need to remember that Languedoc-Roussillon had a long tradition of local seaside tourism. This tradition was taken into account by the Mission’s plan, and actors of local tourism limited the action and plans of the Mission, such as in the case of the conflicts which led to the abandonment of the plans for a sixth new town in the Aude River estuary. The Mission, furthermore, did not achieve its declared aim of a controlled littoral urbanization balanced by nature protection. While reforestation did occur, the establishment of protected areas was much less ambitious than planned, while urbanization spilled over the zoning initially established by the Mission’s planners. Regional planning, in sum, was a major force in the transformation of Languedoc-Roussillon into a major seaside tourism destination. However, it did so in cooperation with other forces and actors and within important limits that need to be acknowledged.

The Mission Racine was at the intersection of two long-standing trends in French public policy. Some authors have pointed out a dynamic of growing state control on the littoral since the 17th century (

Le Bouëdec 2010). Through large-scale redevelopment plans, such as the Canal du Midi and the port of Sète, French national authorities increasingly extended their reach to coastal Languedoc, for military as well as commercial reasons. Tourism development and landscape protection could therefore be seen as yet another instance of state intervention and appropriation of the shoreline during the 20th century, symbolized by General de Gaulle’s overlooking gaze on Languedoc’s coast from the helicopter in 1967. On the other hand, the Mission was also the direct outcome of planning ideas and proposals that had started to emerge in France in the 1930s and 1940s. Many of the planning tools used by the Mission Racine had been introduced in the aftermath of the war for the reconstruction of bombed urban centres. Ideas and proposals for large-scale territorial planning, moreover, had been advanced by various networks of engineers and civil servants since the 1930s and gained traction after the war. In 1963, these proposals led to the establishment of a special governmental authority for regional planning: the Délégation interministérielle à l’aménagement du territoire et à l’attractivité régionale or DATAR (Interministerial Delegation of Large-Scale Planning and Regional Attractiveness). The Mission Racine was, in many ways, the product of these large trends.

While rooted in these trends, the construction of unités touristiques in Languedoc was also explicitly aimed at shaping an environment conducive to leisure and holidays. Seaside resorts were presented as the antithesis of the new towns that were being built close to large French agglomerations. Both the built environment and urban structure were shaped to make the seaside experience an exceptional moment. In the words of the Plan d’urbanisme d’intérêt regional, the goal was indeed “to create, through appropriate urban planning, the framework for this second way of life, which everyone seeks during his few weeks off” (

MIATLLR 1964, p. 3). This was also the main rationale behind environmental protection measures. Although presented as ecological policies and contemporary to the first explicitly environmental intervention of the French state, measures such as reforestation or protection of natural heritage sites sought more to create a pleasant living environment for tourists rather than to preserve ecosystem balances. These measures reinforced the attractiveness of tourism for two reasons: they prevented speculation, while avoiding in selected sites the aesthetic degradation caused by accelerated urbanization. However, they did not stop the expansion of the built space along the Languedoc littoral and its ecological and morphological consequences. In some cases, as with the large-scale use of DDT and other mosquito-eradication techniques, redevelopment might have also caused specific ecological damage.

The Mission Racine was only the first of a long series of public policies for the coast in France. In 1966, two similar missions were established for Corsica and Aquitaine. In the latter case, state officers were very critical of what was considered to be the gigantism of the construction in Languedoc. Despite its modest aims and internal conflicts, the Mission for Aquitaine made it possible to plan small-scale infrastructure concentrated in existing settlements, paying more attention to landscape protection. The success of the Mission Racine led the public administration to present this as a model of public intervention (

Morand-Deviller and Racine 1987). Yet the most significant legacy of the Mission Racine was probably the foundation of the Conservatoire du littoral. Established in 1975, this public body’s mission was to buy and protect coastal land “for today and for the generations to come”. The Conservatoire is frequently seen as representative of the environmental turn of public policies in France. There is, however, a clear continuity with the Mission Racine. The first director of the Conservatoire was Pierre Raynaud, former secretary of the Mission. During his mandate at the Conservatoire, he advocated the development of coastal tourism in France. Convinced that littoral protection was also relevant for keeping the attractiveness of the shoreline, he did not perceive major contradictions between tourism expansion and the function of the institution he directed (

Raynaud 1978). While exceptional in many respects, the Mission Racine thus is part of a longer history of public policies for tourist development in France.

Regional planning for tourist development, however, was not germane to France only. In the United States, the development of coastal tourism in Florida has been prepared and made possible by investment in transportation (roads) and urban infrastructure (aqueducts and energy) made in the context of the New Deal regional planning policies, albeit without much concern for the environment or for the risks associated with coastal settlement (

Steinberg 2006). Regional planning in 1960s and 1970s Italy often included the development of littoral tourism through infrastructure and land-use planning on a very large scale (

Parrinello 2013). In Spain, the growth of tourism in the 1960s was accompanied by conspicuous public investments made in the framework of national economic planning (

Pellejero Martinez 2004). This also included free-interest loans to private developers to expand the infrastructure for tourism, leading also to the creation of new towns along the coast (

Garcia-Ayllon 2015). In a later period, public policies played an important role via the establishment of coastal protected areas, such as in the natural parc of the Aiguamolls de l’Empordà (

Pujol 1985). The attempt to combine development of coastal tourism and the protection of the coastal environment was central to the 1970 plans of the UK Countryside Commission (

Countryside Commission 1970), which discussed the need to protect and valorize England and Wales coasts in terms very similar to the Mission Racine. Regional planning has been key to the growth of foreign tourism in Nigeria in the postcolonial era, although with an approach that prioritized tourism at the expenses of local development (

Adu-Ampong 2018). These cases demonstrate the global significance of this phenomenon. As this paper has shown, historical analysis can help disentangle the role of regional planning and its relation with local actors and pre-existing dynamics. An environmental historical approach can also expose the way the important question of coastal protection has been addressed (or not) and with what effects. We believe these are important questions which would deserve future, more systematic and extended international comparisons.