Abstract

Song Yuan Huaya (the Huaya of the Song and Yuan Dynasties) is a type of seal featuring figurative patterns and sometimes decorated with ciphered or ethnic characters. Their origins are the Song and Yuan Dynasties, although their influence extends to the Ming (1368–1644 CE) and Qing (1644–1912 CE) Dynasties. Although it is based on the Chinese Han seal tradition, Song Yuan Huaya exhibits various elements from the influence of the Silk Road. This is thought to be the first time in Han seal history that the Steppe culture can be seen so abundantly on private seals. This paper takes an interdisciplinary approach to analyse, probably for the first time in the field, some cases of Song Yuan Huaya, in which a dialogue between the Han seal tradition and Silk Road culture occurs. The findings will hopefully advance the understanding of the complicated nature of the art history, society, peoples, and ethnic relationships in question, and will serve as the starting point for further studies of intercultural communication during specific historical periods.

1. Introduction

As an established category of Chinese art, seals are considered among the most significant representatives of Chinese aesthetics. Their form and function evolved from a history of over 3000 years, and the consistency, compared to seals from other cultures, for example the cylinder seals of Mesopotamia, is worth noting.

As a recently studied genre of Chinese seals and having emerged from the large family of Xiaoxingyin 肖形印, also bearing the name Huaya 花押 (both definitions will be discussed later), the estimated total number of Song Yuan Huaya 宋元花押, namely, the Huaya in the Song 宋 and Yuan 元 Dynasties, preserved around the world could be more than 10,000 pieces.1 The style is praised by scholars as “the second and the last summit”, since the first one is considered to be the Qin-Han 秦漢 seals,2 and representing “a revolution” in the genre of Chinese bronze seals.3 Carved with distinctive pictorial designs, enigmatic codes, and ethnic characters, Song Yuan Huaya allegedly developed early during the Song Dynasty (960–1279 CE) and prospered during the Yuan Dynasty (1279–1368 CE), although their influence, as part of a growing appreciation of literati art, is considered to extend to the early period of the Qing 清 Dynasty (1644–1912 CE).

The inter-cultural communications among different nations, ethnicities and regions along the Silk Road became increasingly intense with the expansion of nomadic people who served as the catalysts and agents for that communication. East Asia, as one of the crucial locations in that communication, had an important role in the Song Dynasty and especially so in the Yuan Dynasty founded by the Mongols in the territory of ancient China. During the Song Dynasty, many ethnic political powers set up their own states in the northern area of China, and, by doing so, they kept an intense relation with the Central China regime during their rule. Even though regional conflicts and wars were frequent, economic and cultural exchange occurred intensively between these nations and Central China during the mentioned period. The situation became more interesting in the following period—the Yuan Dynasty. The people of Han ethnicity, although they had lost their political superiority during the Yuan Dynasty, their cultural advantage remained and the communication between the Sino culture and other cultures, such as those introduced via the Silk Road, was deepened and complicated by the empowerment of ethnic groups and the dialectical situation of the people of Han ethnicity.

New and old traditions, the Silk Road and central Chinese cultures, the complex languages, and so on, are all preserved and represented in the material cultures of that time. The study of Song Yuan Huaya as a major cultural heritage of—although not limited to—the period, can certainly help us to better understand the art of seals of the period in question under the influence of the Silk Road.

2. The Study of Song Yuan Huaya

2.1. Definition: Xiaoxingyin, Huaya, and Yuanya—Song Yuan Huaya

Since the character “Ya 押” mainly refers to “signature” in Chinese,4 strictly speaking it should also mean the imprints made by the stamps. However, for the sake of being concise, this paper generalizes the term Ya to indicate both the stamp and the imprint of that stamp, unless clarification is needed for a particular use.

Xiaoxingyin, Huaya, and Yuanya 元押 (Ya of the Yuan Dynasty), are all terms used to describe a genre of seals with pictorial, figurative and coded personal logos or marks on the front surface, i.e., Yinmian 印面. However, the differences between these terms cannot be neglected, and a more precise definition for the research objects of this paper is needed. On the one hand, if the design of Yinmian is taken as the first consideration, then the term Xiaoxingyin should be regarded as synonymous with Huaya, since the term Xiaoxing 肖形 (literally means the depiction of an object) equals the general sense of Hua 花 (flower or non-calligraphic character).5 However, if chronology is the prerequisite, then Yuanya should be taken from Xiaoxingyin and Huaya respectively, since the name “Yuanya” makes explicit reference to a limited historical period: The Yuan Dynasty.

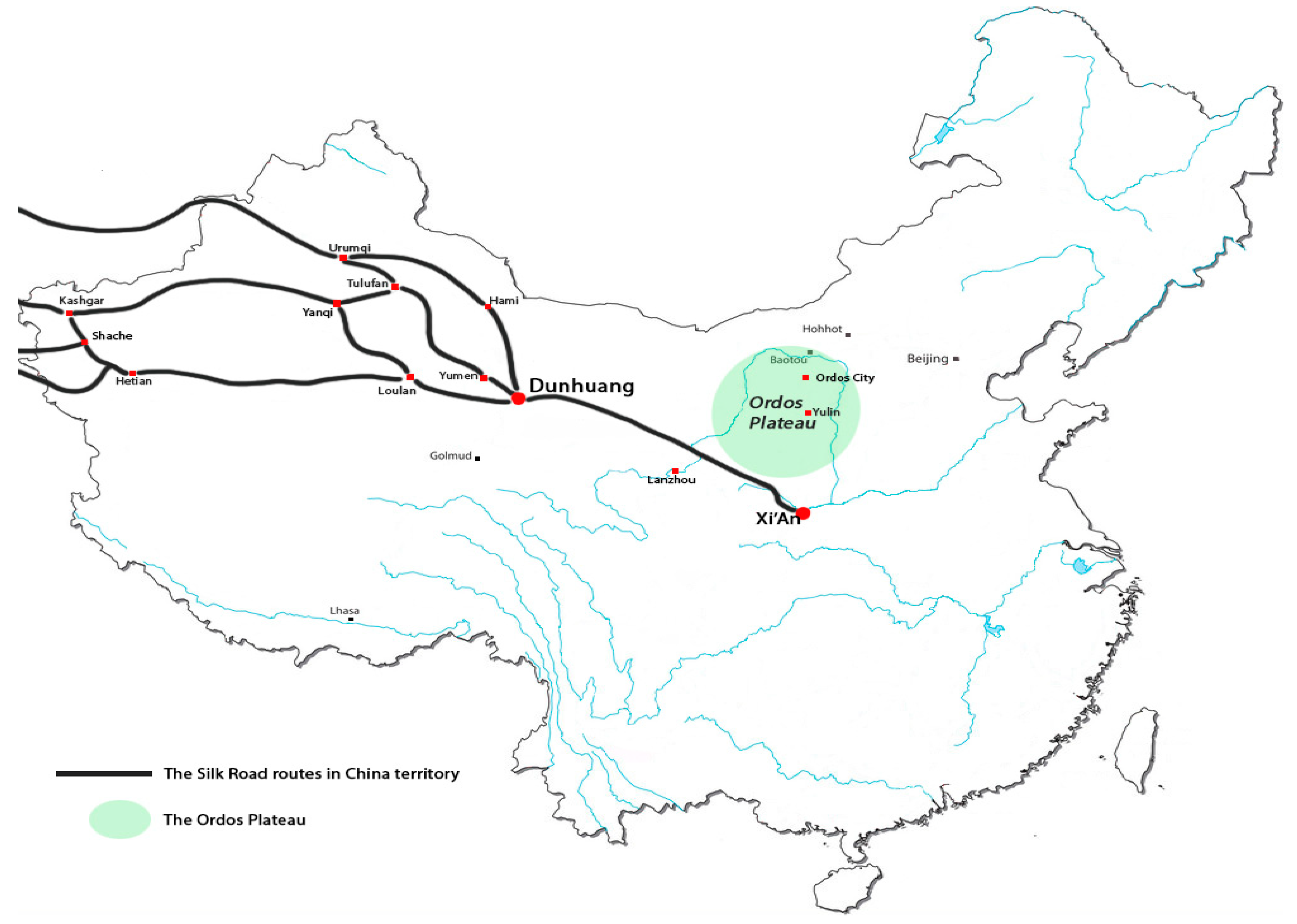

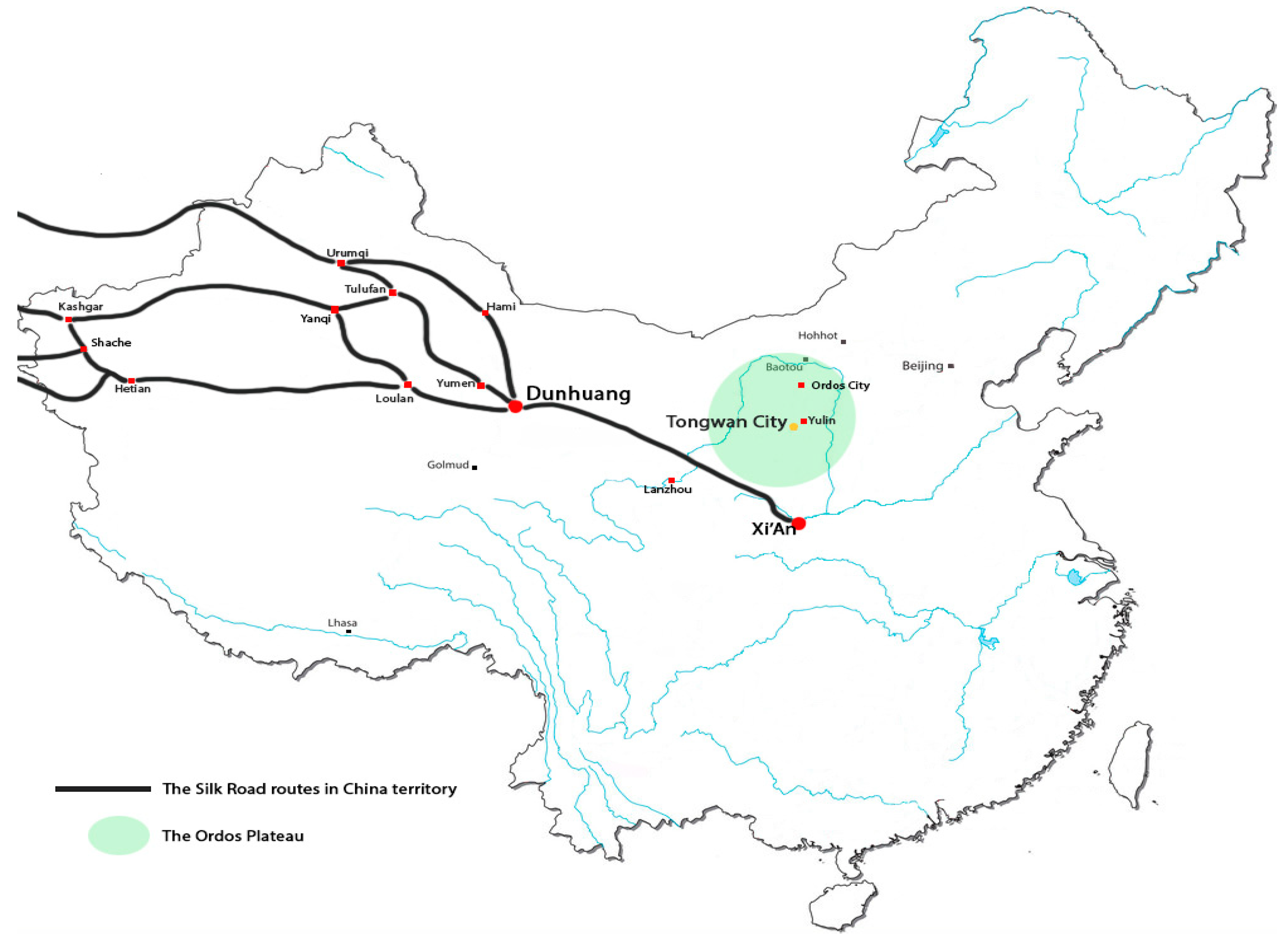

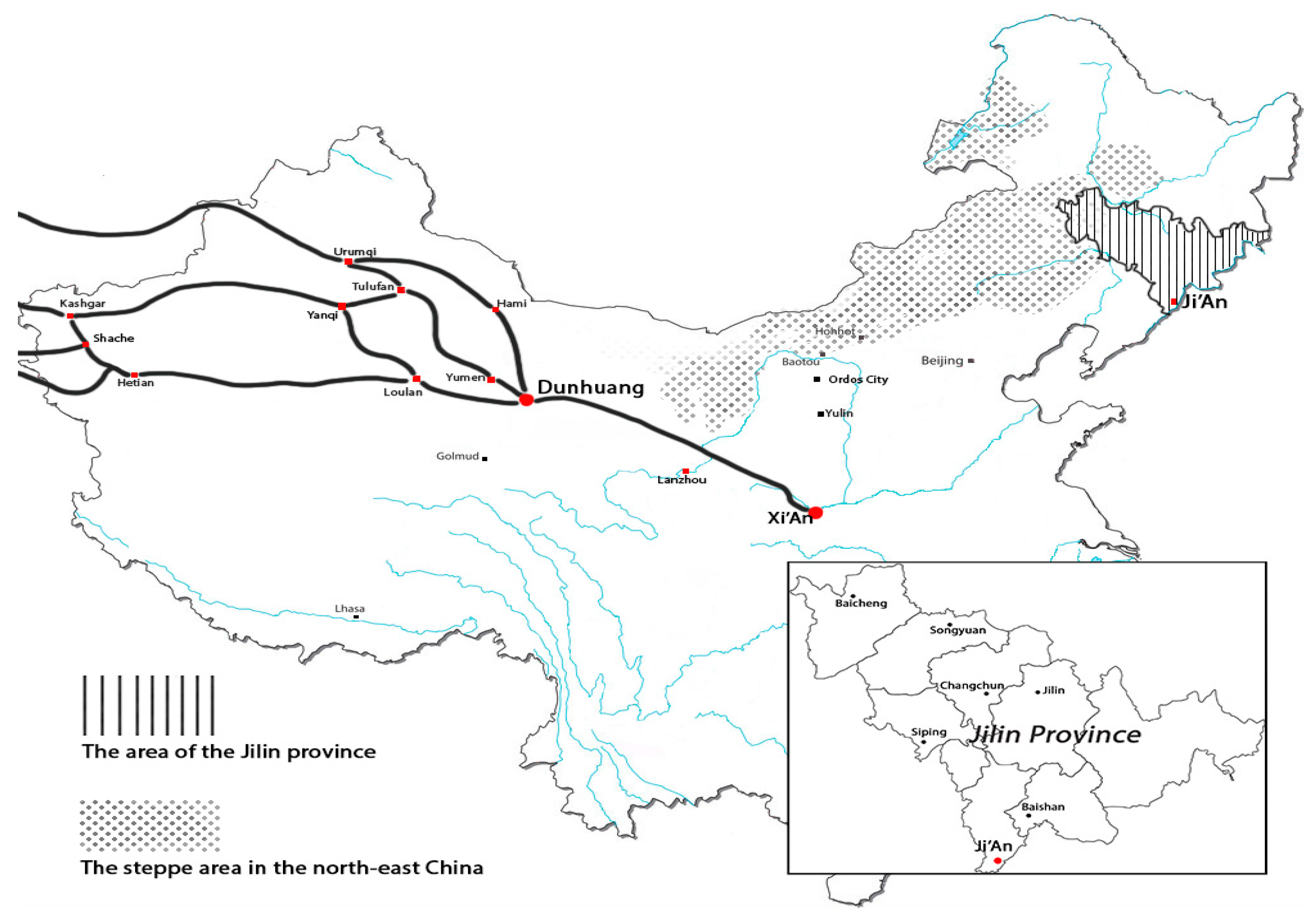

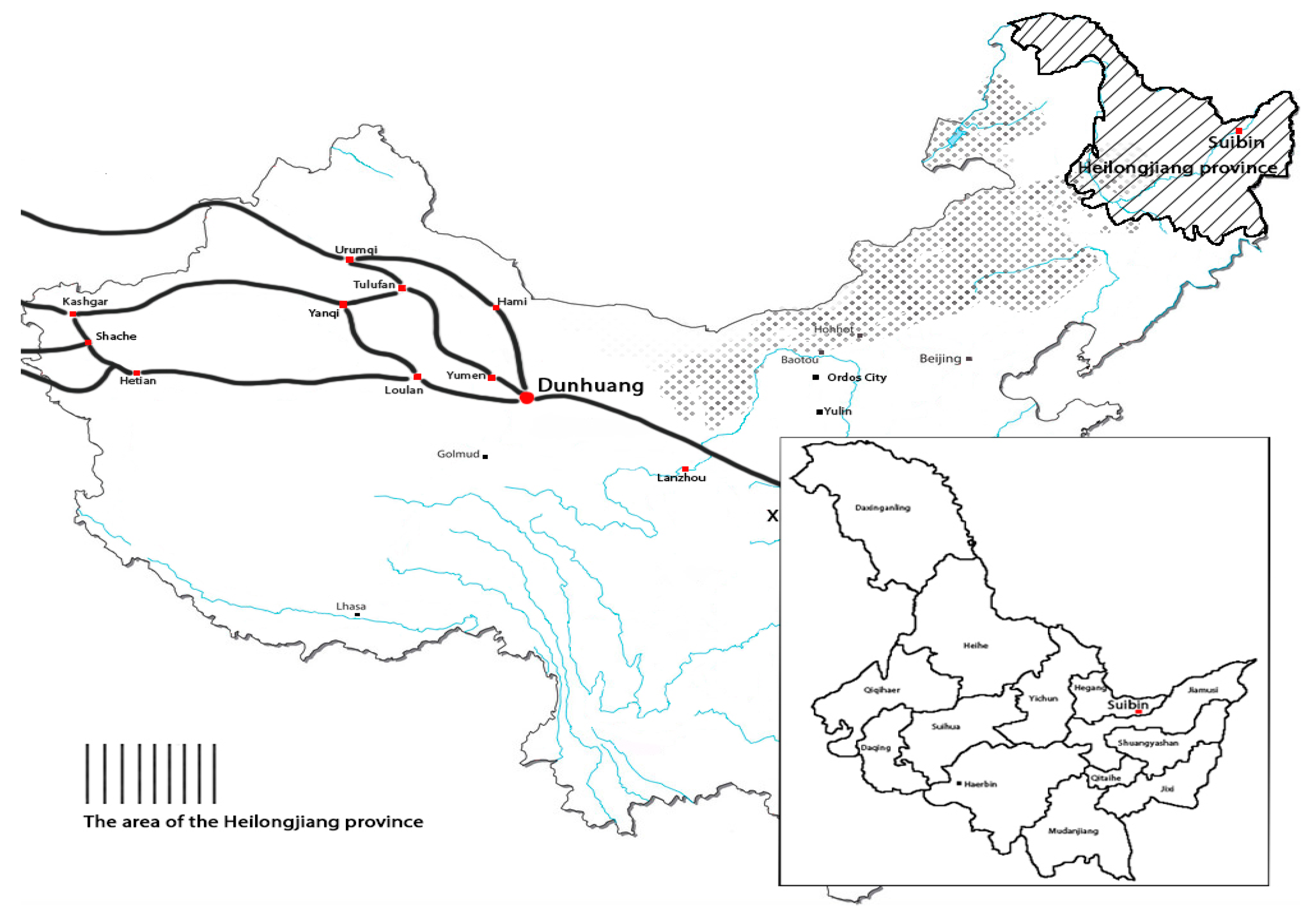

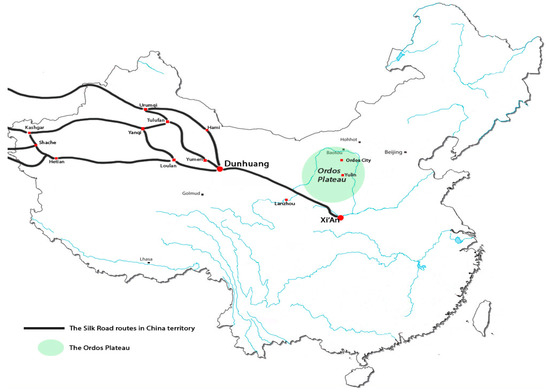

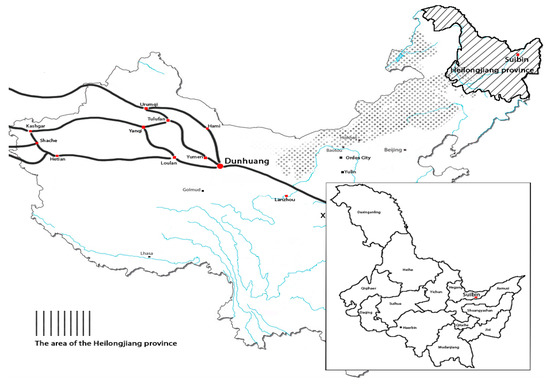

As the current study will show, the term Yuanya is not well-defined, since a great number of seals in this category were not made during the Yuan Dynasty. In fact, the geographic and chronological spectrum of the seals in question is very broad. Geographically, the majority of the seals were found in the grand area of the Ordos plateau, which is near to the hub of the Silk Road’s far-east section: Shannxi 陝西 Province and Xi’an 西安 (Figure 1). According to the mainstream definition, some pieces are from early in the Song Dynasty;6 for instance, Western Xia 西夏 (1039–1227 CE) and Jin 金 (1115–1234 CE) periods, and the majority of them from the Yuan Dynasty. Therefore, in order to differentiate the seals in question from those of earlier periods, such as the Pre-Qin 先秦, Han 漢 and Tang 唐 Huaya, which are mainly addressed by the study of Xiaoxingyin, and to date them more accurately, I suggest that we should narrow the definition down to “Song Yuan Huaya 宋元花押” which literally means those Huaya from the Song and Yuan Dynasties. By doing this, we can also separate them from Ming Qing Huaya 明清花押 (those from the Ming 明 (1368–1644 CE) and Qing 清 Dynasties), because the latter have their own style and artistic pursuit, and hence are not the target of the current study.

Figure 1.

The Ordos Plateau.

Although, as implied by the above naming, this paper will use the term Song Yuan Huaya as a subgroup of Xiaoxingyin in acknowledging that they have many characteristics in common, the uniqueness of Song Yuan Huaya is at the forefront of the discussion. For instance, although the design on Yinmian, which is not exquisite calligraphy as traditional Chinese seals always have, is shared by all Xiaoxingyin, Song Yuan Huaya, as a kind of private seal, was prevalent among all social classes, especially during the Yuan Dynasty,7 and is considered a representative of literati art favored since the North Song 北宋 Dynasty (960–1127 CE),8 due to its free, creative and sometimes decorative abstract style. In many respects, Song Yuan Huaya developed away from its predecessors, namely those Xiaoxingyin before it. For example, unlike others, it is highly inclusive and shows the intense influences of other cultures.

2.2. Literature Review

It is not surprising that, compared to the more comprehensive Yinxue 印學 (Chinese orthodox seal9 study), the study of Song Yuan Huaya began quite late, and its earlier stages were stagnant for four reasons: (1) The majority of the objects identified as Song Yuan Huaya were allegedly obtained from tomb robbery and random surface finds, later emerging in curio markets no earlier than the 1920s to 1930s. They are therefore quite new to the experts, connoisseurs and collectors. (2) For the same reason, the archaeological context and other interpretational information about Song Yuan Huaya remain seriously insufficient, and it is very difficult to ignite a fast-growing expertise without adequate resources. (3) The number of the objects identified as Song Yuan Huaya is relatively small compared to the massive amount of so-called Chinese orthodox seals, so they are usually studied as a subgroup of Chinese orthodox seals and hence lose their unique identity. (4) Finally, some early studies and records of Song Yuan Huaya, preserved in the collection of Yinpu 印譜 (a book of seal imprints) under the title of Zaxiang 杂项 (miscellaneous items), are executed in the most traditional way of studying seals.10 Yinpu, Yince 印冊 (an anthology of seal imprints) or Yinhui 印匯 (a collection of seal imprints) are the dominant forms of publication of the field of Yinxue, and should be understood as a typological inventory focusing on collecting, reporting and reading the seal imprints, rather than their investigation and interpretation as a cultural, social and historical complex.11 The topics in the field of Xiaoxingyin studies, such as the relations between primordial pictorial design and the development of the Chinese written language, and cultural influences reflected by Xiaoxingyin in different historical and social contexts, etc., are not taken as main subjects in a book like Yinpu, although general information is sometime sporadically provided in the preface, introduction and other relatively short sections.

Books in the field of Xiaoxingyin studies and/or Song Yuan Huaya studies in recent years usually start with a criticism of classical seal studies and advocate a re-evaluation of Chinese seals. They intentionally add more information to the preface or other introductory sections in order to examine the research objects more extensively. Yet an interdisciplinary approach is still needed for a better understanding, because the majority of the works, influenced by previous studies, orientate themselves mainly to the traditional form of Yinpu. For example, Xiaolu Zhou’s book: Zhongguo Gudai Zhuanke Yishu Qipa 元押:中國古代篆刻藝術奇葩 is among the distinguished works in this field, for it not only collects nearly three thousand pieces of Song Yuan Huaya12 from a broad span of time, but also justifies the idea that Song Yuan Huaya should be considered an enrichment of the Chinese seal system since the system used to be focusing only on the calligraph related seals.13 Yet the book still calls itself a “Yinpu” and hence its goal is to “share the interests of the collection of Yuanya”.14 In other words, the book, as a representative of the study, takes the traditional approach to presenting its objects more for their aesthetic than other values.

Other works with a similar approach, such as Tingkuan Wen’s Zhongguo Xiaoxingyin Daquan 中國肖形印大全, has an even more informative introduction to the genre of Xiaoxingyin, including Song Yuan Huaya, yet still locates itself in the genre of Yinpu.15 The famous seal collector, Shanqing Dai 戴山青, credits Song Yuan Huaya as being the “second and the last peak of the Bronze Seal system, [and] it should be regarded as the revolutionary period in the history of seals”.16 Yet his article remains in the area of traditional Yinpu. Other Yinpu of the same sort written by scholars in recent decades include Yuanya Yinhui 元押印汇,17 and Tangsongyuan Siyin Yaji Jicun 唐宋元私印押記集存.18

There have nevertheless been many works published in recent years related to the subject of Song Yuan Huaya. Although they inherit the traditional definition and identification (and still call the seals Yuanya), most of them begin to move towards a new horizon that regards Song Yuan Huaya as part of the material cultural complex of a specific historical time. For example, Chen and Pan’s article studies the imprints of Yuanya on the documents found in Heishui City 黑水城 (Khara-Khoto). The article starts with the seal imprints, and proceeds to investigate the seal system designated by the government of Heishui City during the Yuan Dynasty.19 Another example is the book: Yuandai Chuban Shi 元代出版史, which locates Song Yuan Huaya in the study of the publishing history of the Yuan Dynasty and investigates the social context and cultural stimuli that gave Song Yuan Huaya popularity during that time.20 Following this trend, this paper employs an interdisciplinary approach, including art historical, linguistic, and historical studies, to the nature of Song Yuan Huaya as the important material culture of the Song and Yuan Dynasties. The emphasis on those artistic characteristics that intensively reflect the influences of the Silk Road culture and the interaction of those influences with the local context. Hopefully, this study can serve as the starting point or a resource for the further study of topics, such as the Song and Yuan societies and ethnic relationships, and cultural policies, for example, the restrictions on metal workmanship issued by the Yuan government and the inter-influences between the cultures of the Silk Road and Central China.

3. Case Studies: The Characteristics of Song Yuan Huaya and the Silk Road Influences

As a genre of Chinese seals, Song Yuan Huaya’s most distinctive characteristic should be those that differentiate it from other genres. Therefore, the free style of the themes, abstract pictorial signs and ethnic characters, the personal signature design on Yinmian, and sometimes the combinations of these elements are all considered by mainstream studies to be the attributes of Song Yuan Huaya. Nevertheless, not enough studies have been conducted so far to identify some of these elements and their possible correlation with the influences of the Silk Road. This paper, however, focuses on these elements.

When using the term Silk Road, this paper adopts the singular form. The reason is because I agree with Beckwith (2009) that the plural form “Silk Roads” contains a “misconception of Central Eurasia only being a system of trade routes”.21 Beckwith elaborates:

The Silk Road was not a network of trade routes, or even a system of cultural exchange. It was the entire local political-economic-cultural system of Central Eurasia, in which commerce, whether internal or external, was very highly valued and energetically pursued—in that sense, the ‘Silk Road’ and ‘Central Eurasia’ are essentially two terms for the same thing.22

The abovementioned principle is also applicable to East Asian perspectives on the Silk Road. Similar to the meaning that the Silk Road concept cast on the “political-economic-cultural system of Central Eurasia”, the singular form of the term should be appropriate for describing a dynamic system of the East Asia part of the Silk Road as well.

Song Yuan Huaya was definitely born in such an East Asian part of the Silk Road complex due to the historical context of its time. The following case studies will show that no matter on which route the cultural exchange occurred,23 the uniqueness of Song Yuan Huaya as a genre of Chinese ancient seals is closely correlated with the influences of that complex.

A book written in the Yuan dynasty, Yunhui 韻會, explains that “Ya, means signature (押,署也)”.24 The character “Ya” was not introduced into the Chinese written language system until East-Han 東漢 Dynasty (25–220 CE), as Xiaolu Zhou mentions in his work,25 although the objects functioning as “Ya” have existed since the earliest stages of China’s history. The character “Ya” can serve as a morpheme to combine with other characters to refer to different kinds of seals. For instance, the book from the Song Dynasty: Shilin Yanyu 石林燕语, states that: “there was no ‘Ya-zi’ 押字 (zi 字 Chinese character) in the early period of the Tang 唐 dynasty (618–970 CE), only Caoshu 草书 (cursive script) of one’s own name used as the personal code. That is why it was called ‘Hua-shu’ 花書 (non-calligraph script) at that time.”26 The tradition of Ya serving as personal code, along with the prevalence of Song Yuan Huaya and the uprising of literati arts, makes its way into the Qing Dynasty.27

Unlike the traditional Chinese seals, as mentioned earlier, Song Yuan Huaya adopted a very free style in its shapes, designs, and themes. The subordinary, or sometimes completely absent, calligraphic characters create room for decorative patterns or ethnic characters. A Yinpu of the Ming dynasty explains this is because most of the Mongolians and Semuren28 色目人 were not familiar with Chinese characters, and so invented Yuanya to sign their own names.29 I agree with Xiaolu Zhou that the point seems biased from a Sino-centric perspective.30 That is to say, the dominant preference of non-calligraphic design seen on the Song Yuan Huaya could result from many possible reasons, such as aesthetic choice, favored identity recognition, or contemporary fashion, rather than just one possibility that lacks evidence.

The following case studies reveal that the various elements and the format of their application to Song Yuan Huaya, coherent with the forms of folk art, are mainly expressing the good wishes for auspiciousness, blessing and good fortune. This theme relates Song Yuan Huaya closely to the ancient tradition of Jiyuyin 吉語印 (auspicious seals), which is one of the traditions most welcomed by folk people in Chinese seal history.31 Nevertheless, Song Yuan Huaya is unique compared to other Jiyuyin. Unlike its predecessors, its artistic style is more decorative, abstract and free, moreover, it intensively shows the influence of the non-Han culture of, for instance, Jurchen, Khitan, and Mongolian peoples. All these make it more customized for patronage’s need than seals of other historical periods, such as a demand of family name combined with an anti-forgery code or an ethnic character/symbol.

3.1. The Deer

It is noteworthy that most of the zoomorphic designs on Song Yuan Huaya are stylistically different from those on other Chinese seals. The motif of the deer is taken as an example here since the deer is one of the most important symbols both for nomadic people and the people of Han ethnicity.

For the people of Han ethnicity, the deer symbolizes purity, nobility, and harmony in Chinese culture.32 For nomadic people, the deer is the most holy creature in their religion. For instance, an anthropomorphic deer stone was observed in Mongolian societies from the early to the late bronze age.33 Similar deer stone with deer motif decorations were found in the west-north area of China, dating to the Shang and Zhou Dynasties.34

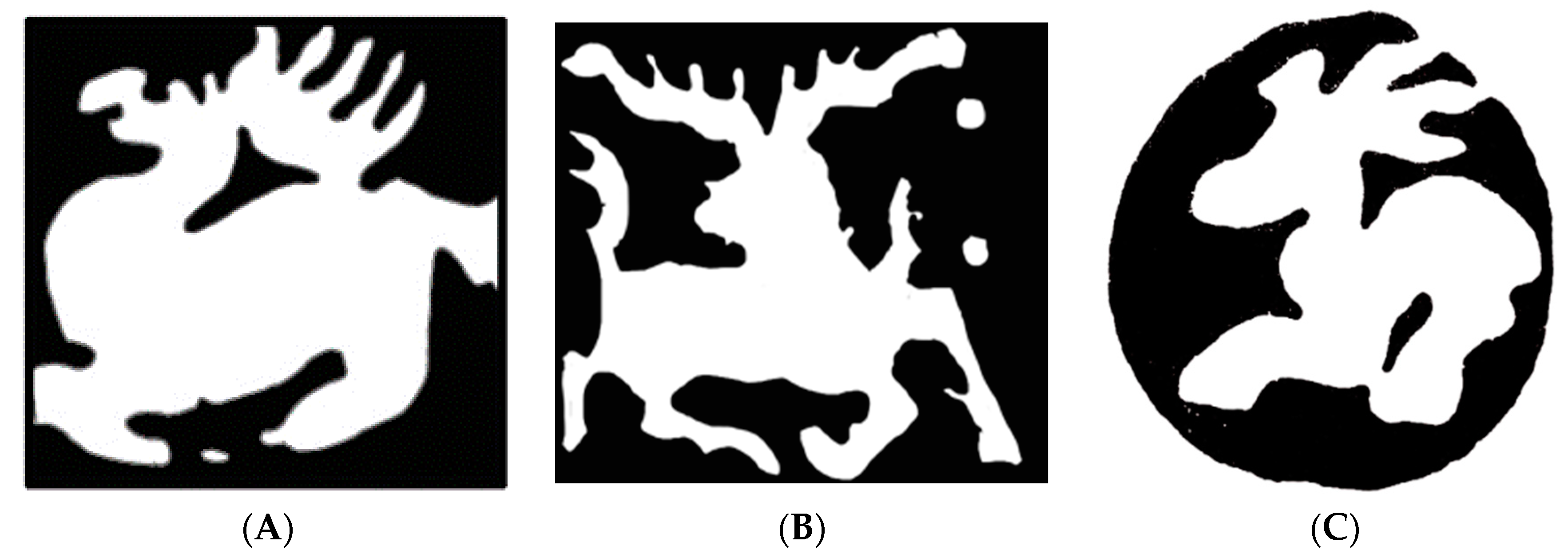

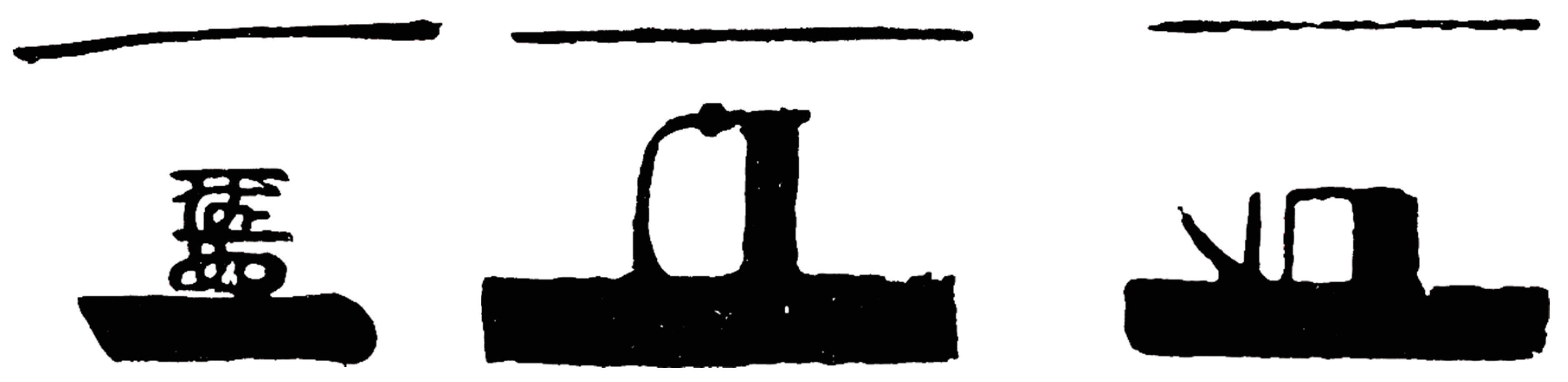

The shapes and plastic styles of the deer motif from periods, such as the Warrior States 戰國 (453 BC–221 CE), the Han 漢 (202 BC-220 CE), and the Tang Dynasties are quite consistent. In other words, they belong to the style of the Qin-Han tradition of Xiaoxingyin.35 The earlier the historical period, the more coherent consistency can be observed. The plastic style of the Qin-Han is presented in a highly decorative way, which emphasizes the carved lines suggested by different parts of the deer, such as the bent backward slender neck, head, antlers, the always twisted, sometimes crossed legs, and the waved trunk. The simplified “S” shape of the deer’s body has always been the focus of the depiction (Figure 2).

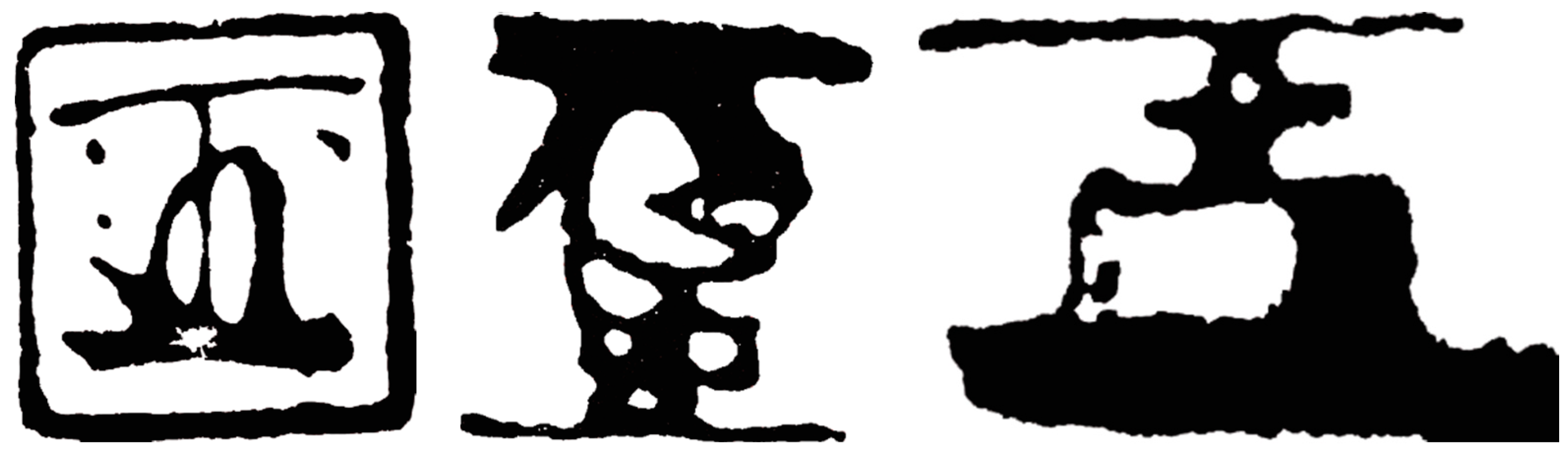

Figure 2.

(A) A Xiaoxingyin with a reindeer motif. The Warrior States Period. Inventory number: 0647. Sketched by author. Picture source: Wen (1995), p. 191. (B) A Xiaoxingyin with a reindeer motif. The Warrior States Period. Inventory number: 0649. Sketched by author. Picture source: Wen (1995), p. 191. (C) A Xiaoxingyin with a reindeer motif. The Warrior States Period. Inventory number: 0648. Picture source: Wen (1995), p. 191.

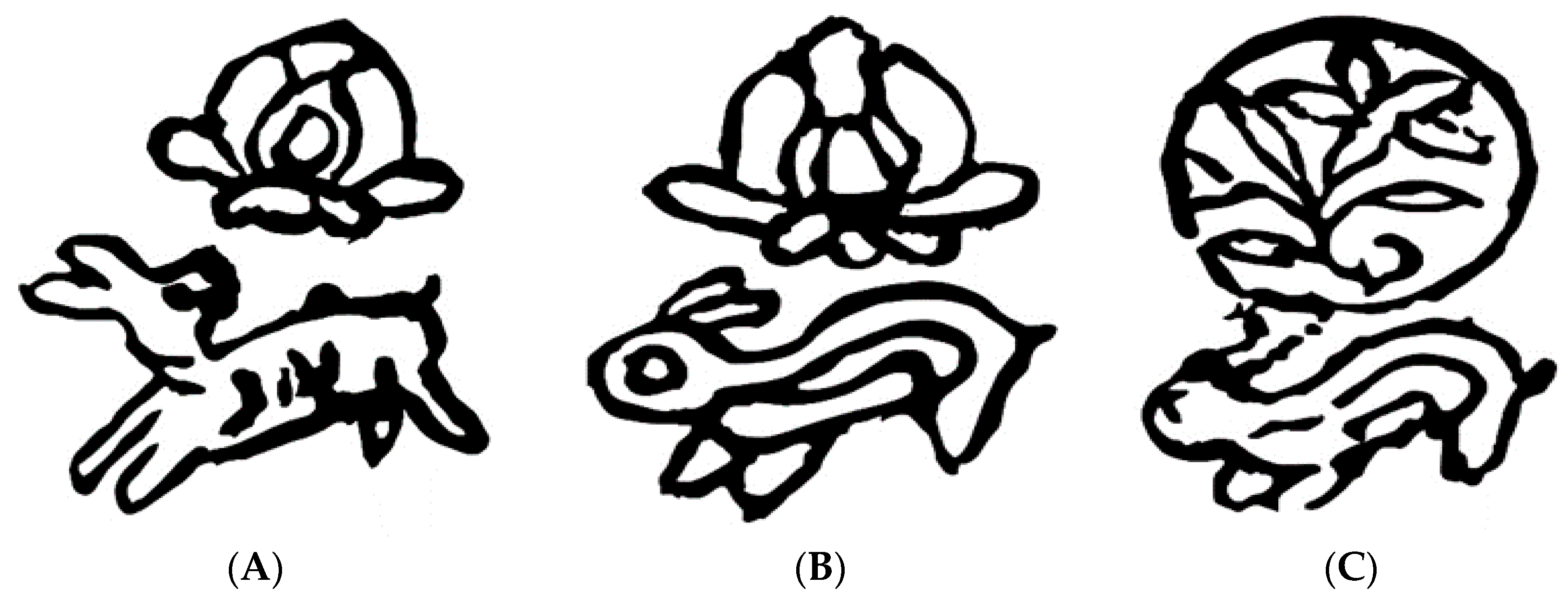

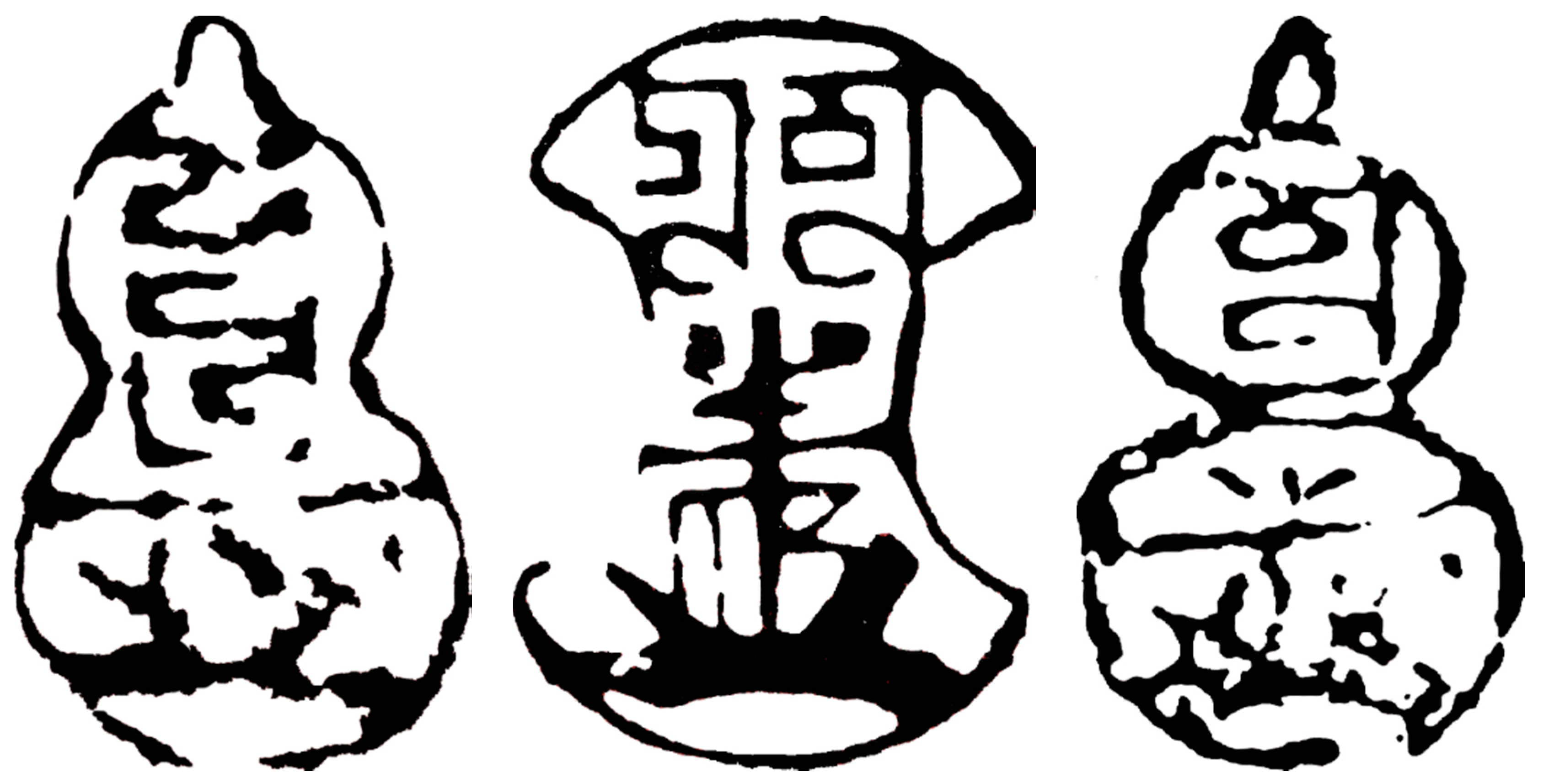

However, that “S” shape of the Qin-Han style changed into freestyle, minimalist or naturalistic forms in the case of the deer motifs of Song Yuan Huaya. Some of the details which once were omitted in the Qin-Han style, such as the spotted coat and the round eyes, can be seen in the design. From a technical aspect, that change is partially because most of the Song Yuan Huaya were made in Zhuwen 朱文 (relief Yinmian), which is able to capture more details than the calligraphic-friendly Baiwen 白文 (intaglio Yinmian). In some cases of minimalistic style, the spotted coat is symbolized by compartmentalized lines, which can be considered another unique feature of Song Yuan Huaya (Figure 3).

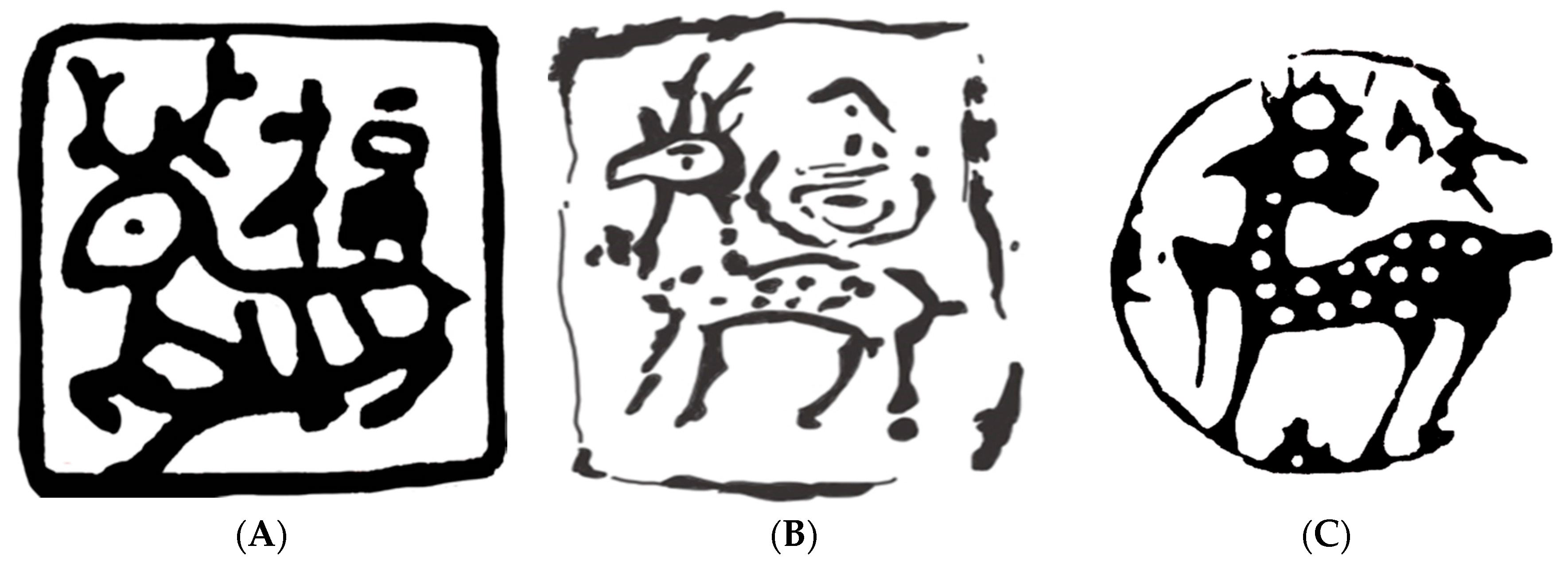

Figure 3.

(A) A Song Yuan Huaya with a deer motif. The period of the Song and Yuan dynasties. Inventory number: 0670. Sketched by author. Picture source: Wen (1995), p. 195. (B) A Song Yuan Huaya with a deer motif. The period of the Song and Yuan dynasties. Inventory number: 0673. Sketched by author. Picture source: Wen (1995), p. 191. The original collection: Bochuan, Huang. Zun Gu Zhai Ji Yin [《尊古齋集印》]. Book of impressions. (C) A Song Yuan Huaya with a deer motif. The period of the Song and Yuan dynasties. Inventory number: 0675. Picture source: Wen (1995), p. 195. The original collection: Qingqing, Wu. Shiliu Jinfu Zhai Yin Cun [《十六金符齋印存》]. Book of impressions. The Fourteenth year of Guangxu, the Qing dynasty.

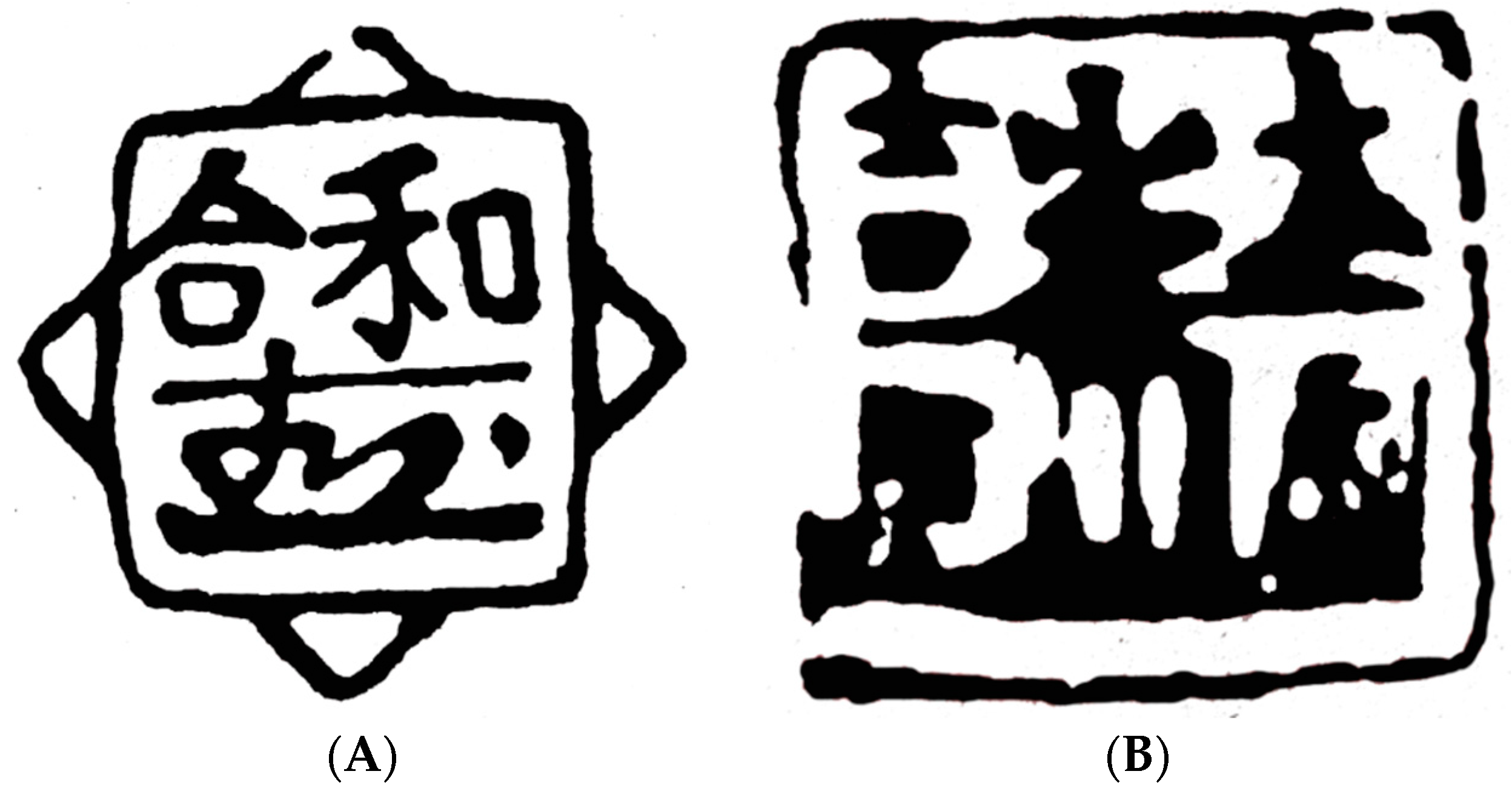

Apart from the diverse designs of the body, the deer motif of Song Yuan Huaya can also combine with different motifs and/or characters. In most cases, the deer motif is accompanied by a Chinese character “Lu 鹿 (deer)” or “Fu 福 (blessings)”, or a Phagspa character “ꡂꡞ” Ji 記 (a sign labelling the signature or a commercial brand) (Figure 4). Phagspa is one of the most persuasive diagnostic features for identification of Song Yuan Huaya, since it is a language invented and prevalent during the Yuan dynasty.36 It is noteworthy that when the deer motif is co-represented with the character Fu 福, it forms a Jilihua 吉利話 (auspicious idiom): “Fulu Shuangquan 福祿雙全 (both blessings and wealth)”.37 The spirit of this combination matches the overall spirit of Song Yuan Huaya, because seals with auspicious significance were highly regarded in the field of private seals. There are many Jilihua seen in Song Yuan Huaya, such as Wanan 萬安, which means all kinds of wellbeing, Daji 大吉, which means auspicious, and Hehe 和合, which means harmony (Figure 5). There is sufficient reason to believe that some particular patterns and ethnic characters also express this spirit. This will be elaborated upon later.

Figure 4.

A Song Yuan Huaya with a deer motif and a Phagspa character “Ji”. The Yuan Dynasty. Inventory number: 0668. Sketched by author. Picture source: Wen (1995), p. 194.

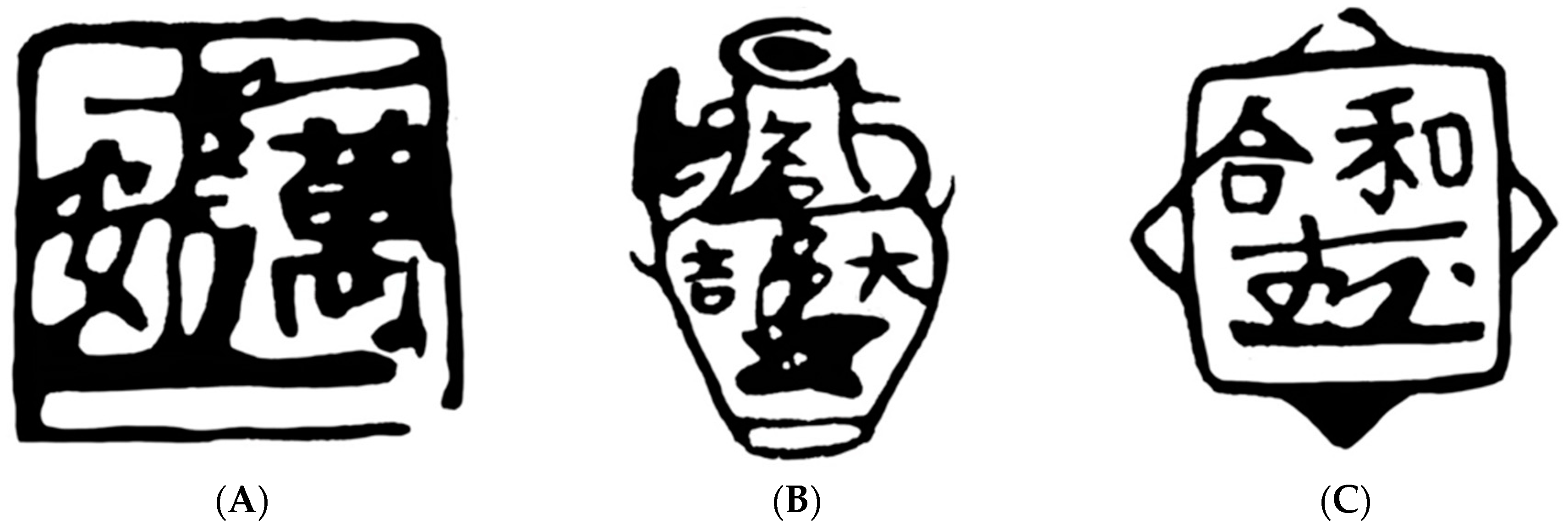

Figure 5.

(A) A Song Yuan Huaya with Chinese characters “Wanan” and an ethnic element. The period of the Song and Yuan Dynasties. Sketched by author. Picture source: Shi (1995), p. 60. (B) A Song Yuan Huaya with Chinese characters “Daji 大吉” and an ethnic element. The period of the Song and Yuan dynasties. Inventory number: 1873. Sketched by author. Picture source: Wen (1995), p. 436. The original collection: Qingqing, Wu. Shiliu Jinfu Zhai Yin Cun [《十六金符齋印存》]. Book of impressions. The Fourteenth year of Guangxu, the Qing dynasty. (C) A Song Yuan Huaya with Chinese characters “Hehe 和合” and an ethnic element. The period of the Song and Yuan Dynasties. Inventory number: 1684. Sketched by author. Picture source: Wen (1995), p. 402.

The difference in artistic style illustrated by the deer motif can also be observed in the case of the tiger motif. Xiaoxingyins inscribed with the tiger before the Song and Yuan Dynasties mainly follow the composition that has the tiger, with emphasis on their curved and succinct lines, similar to the deer, remaining in the lower part of the Yinmian, while Chinese characters such as idioms like Weiyang 未央 (ceaseless)38 or Changli 長利 (profit forever),39 which are the diagnostic features for dating to the Han Dynasty (Figure 6). The abstract tiger motif of the Han Dynasty delineated by restrained and formatted lines, shows that they belong to a similar artistic trend.

Figure 6.

(A) A Jiyuyin with Chinese characters “Weiyang” and a tiger motif. The Han Dynasty. Inventory number: 0509. Sketched by author. Picture source: Wen (1995), p. 164. The original collection: Chen, Jieqi. Fu Zhai Gu Yin Ji [《簠齋古印集》]. Shanghai: Shenzhou Guoguang Society, 1936. (B) A Jiyuyin with Chinese characters “Changli 長利”. The Han Dynasty. Sketched by author. Picture source: Li (2012), p. 72.

It is not surprising that this composition tradition is broken by Song Yuan Huaya as well. Similar to the deer motif, the tiger motif in Song Yuan Huaya preserves more of a sense of creativity and diversity, with an obvious inclination to a more naturalistic style. For instance, the Song Yuan Huaya sample highlighted here illustrates a tiger standing diagonally, with compartmentalized lines on its body symbolizing the texture of its coat, and its two front legs hanging beneath the stylistic head. There is a Phagspa character “ꡂꡞ” Ji 记 on top of the tiger’s back (Figure 7).40 The composition reminds the viewer of the tradition of the Han Dynasty Jiyuyin mentioned above, yet the artistic innovation and more naturalistic ideal show that Song Yuan Huaya is not just a simple successor to that tradition, but a creative invention resulting from cultural dialogue.

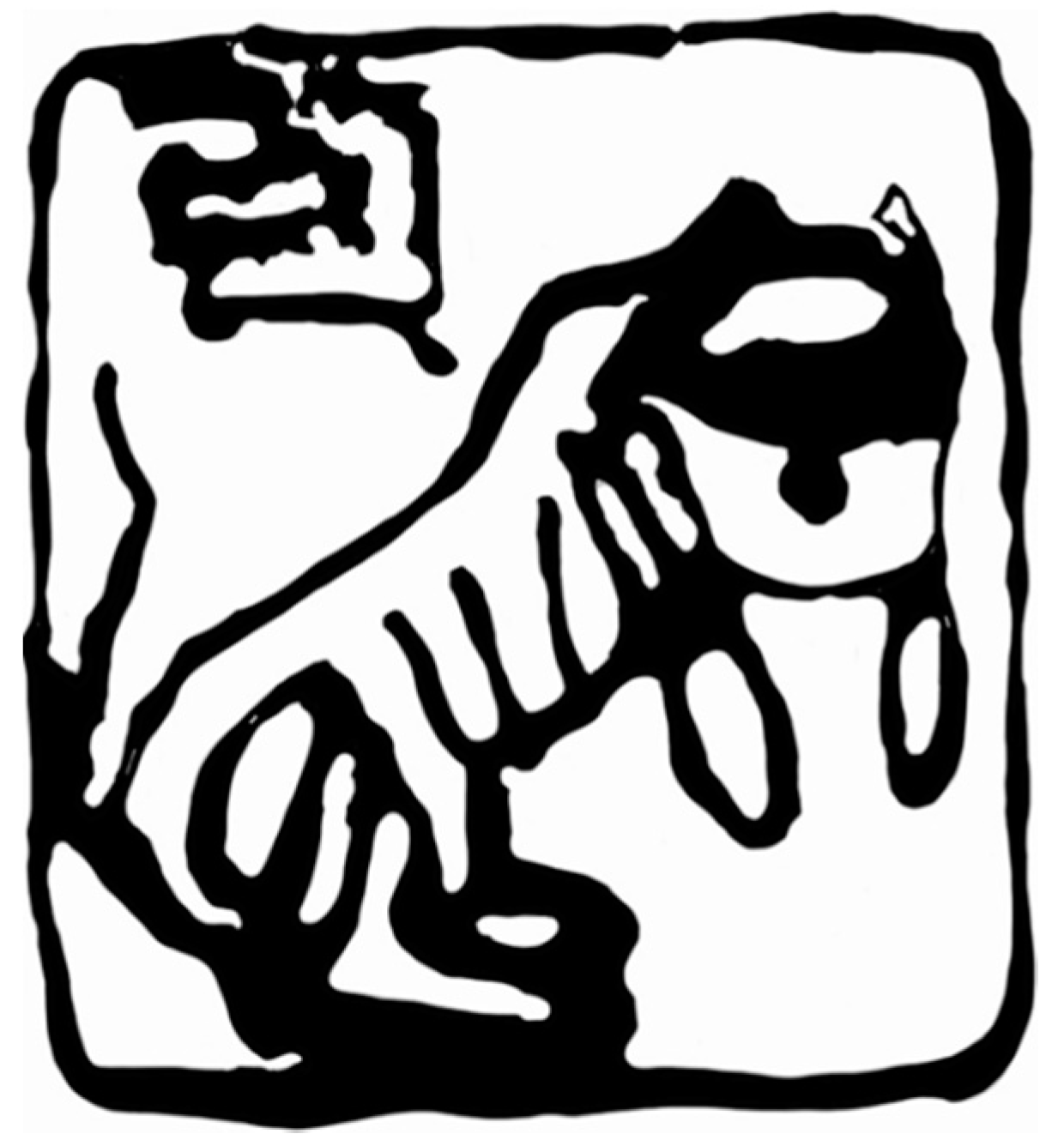

Figure 7.

A Song Yuan Huaya with a Phagspa characters “Ji” and a tiger motif. The Yuan Dynasty. Inventory number: 0429. Sketched by author. Picture source: Wen (1995), p. 150.

3.2. The Hare/Rabbit

The case of the hare/rabbit motif can explicitly illustrate how the Silk Road influenced dialogue with the Chinese seals tradition. The following analyses will show that the themes, animal species, and artistic styles of the concerned groups are different.

“Jade rabbit-on-the moon” is an ancient Chinese artistic theme, and after the Tsin晋 Dynasty (280–420 CE), the Jade rabbit-on-the-moon theme developed into a format depicting a Jade rabbit (deity) on the moon busy making an elixir by pulverizing ingredients with a pestle in a mortar.41 This theme is well captured in Xiaoxingyin and Song Yuan Huaya pieces (Figure 8). However, with further inquiry into the Song Yuan Huaya group, following this theme, one can see the uniqueness that reflects the influence from the West region, more specifically, from the Steppe culture.

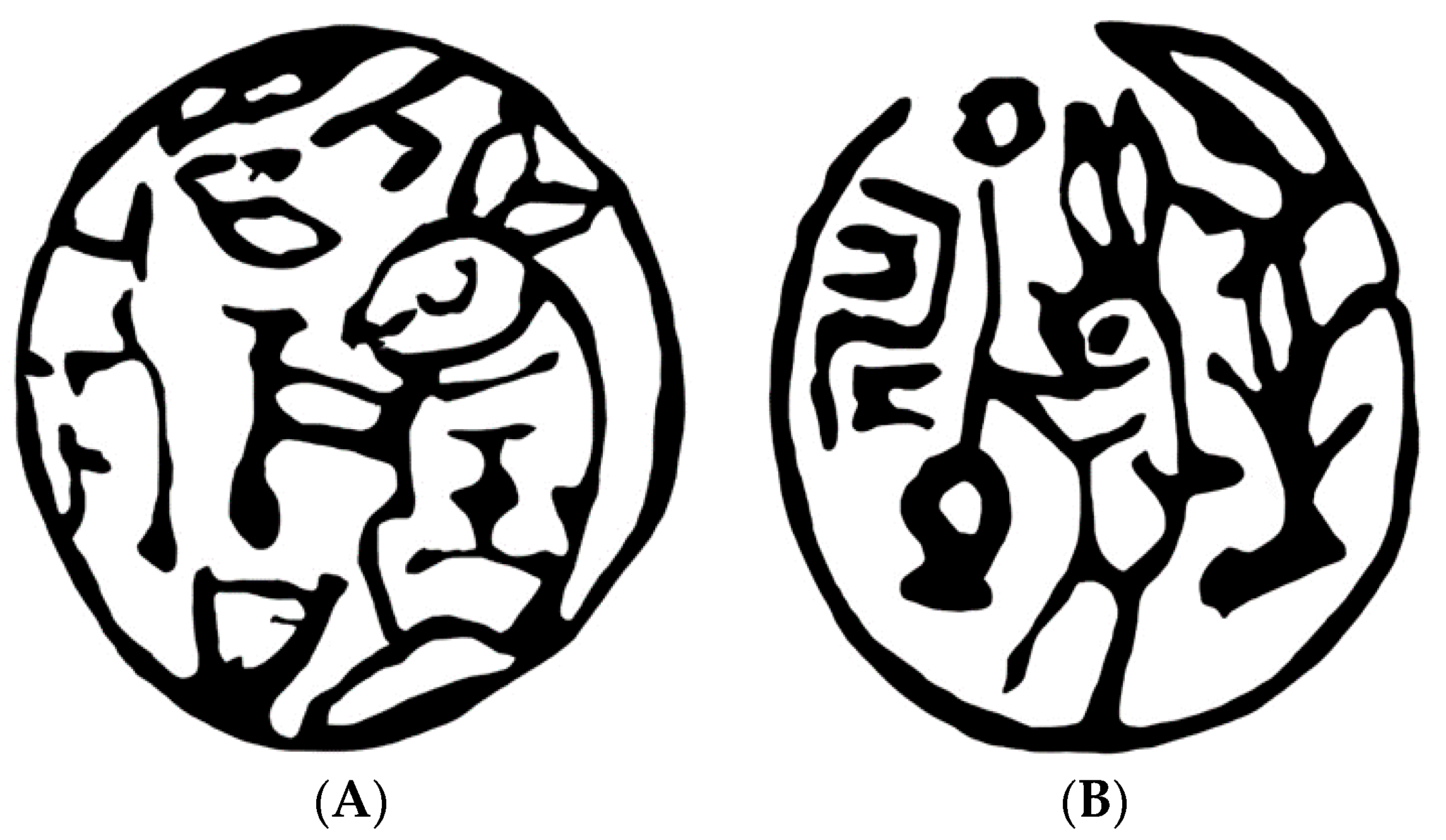

Figure 8.

(A) A Song Yuan Huaya with a depiction of Jade rabbit-on-the moon. The period of the Song and Yuan Dynasties. Inventory number: 0703. Sketched by author. Picture source: Wen (1995), p. 201. The original collection: Bochuan, Huang. Zun Gu Zhai Ji Yin [《尊古齋集印》]. Book of impressions. (B) A Song Yuan Huaya with a depiction of Jade rabbit-on-the moon. The Yuan Dynasty. Inventory number: 0699. Sketched by author. Picture source: Wen (1995), p. 200.

As already mentioned above, Song Yuan Huaya has a strong relation to the traditional artistic ideal of Chinese seals. Nevertheless, some of the Song Yuan Huaya highlighting the hare theme can be differentiated from traditional seals. They usually depict a single hare, unlike the rabbit in the Jade rabbit-in-moon theme, mostly running in one direction with its head turned back in the opposite direction. Occasionally there is an enigmatic inscription on its main body, otherwise only compartment marks are presented there (Figure 9). Except for the single running hare, there are three other formats of the hare theme: the first one is a single hare raising its lower half body so the whole shape of its body resembles a horizontal “S” with a smaller tail flying to the diagonal top (Figure 10). In that case, the two back legs disappear for the sake of the plastic style. The second one shows a single running hare with floral motifs, such as a stylistic lotus flower hanging above its back (Figure 11), while the last one is a unique item depicting the featured hare with an inscribed ingot shape component below it (Figure 12).42

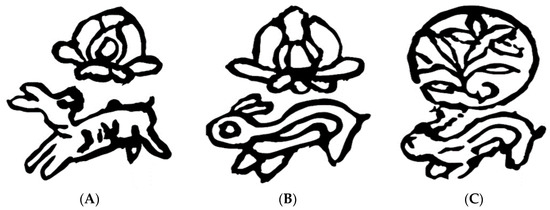

Figure 9.

(A) A Song Yuan Huaya with a Hare motif. The period of the Song and Yuan Dynasties. Inventory number: 0690. Sketched by author. Picture source: Wen (1995), p. 198. The original collection: Bochuan, Huang. Zun Gu Zhai Ji Yin [《尊古齋集印》]. Book of impressions. (B) A Song Yuan Huaya with a Hare motif. The period of the Song and Yuan Dynasties. Inventory number: 0702. Sketched by author. Picture source: Wen (1995), p. 201. The original collection: Bochuan, Huang. Zun Gu Zhai Ji Yin [《尊古齋集印》]. Book of impressions.

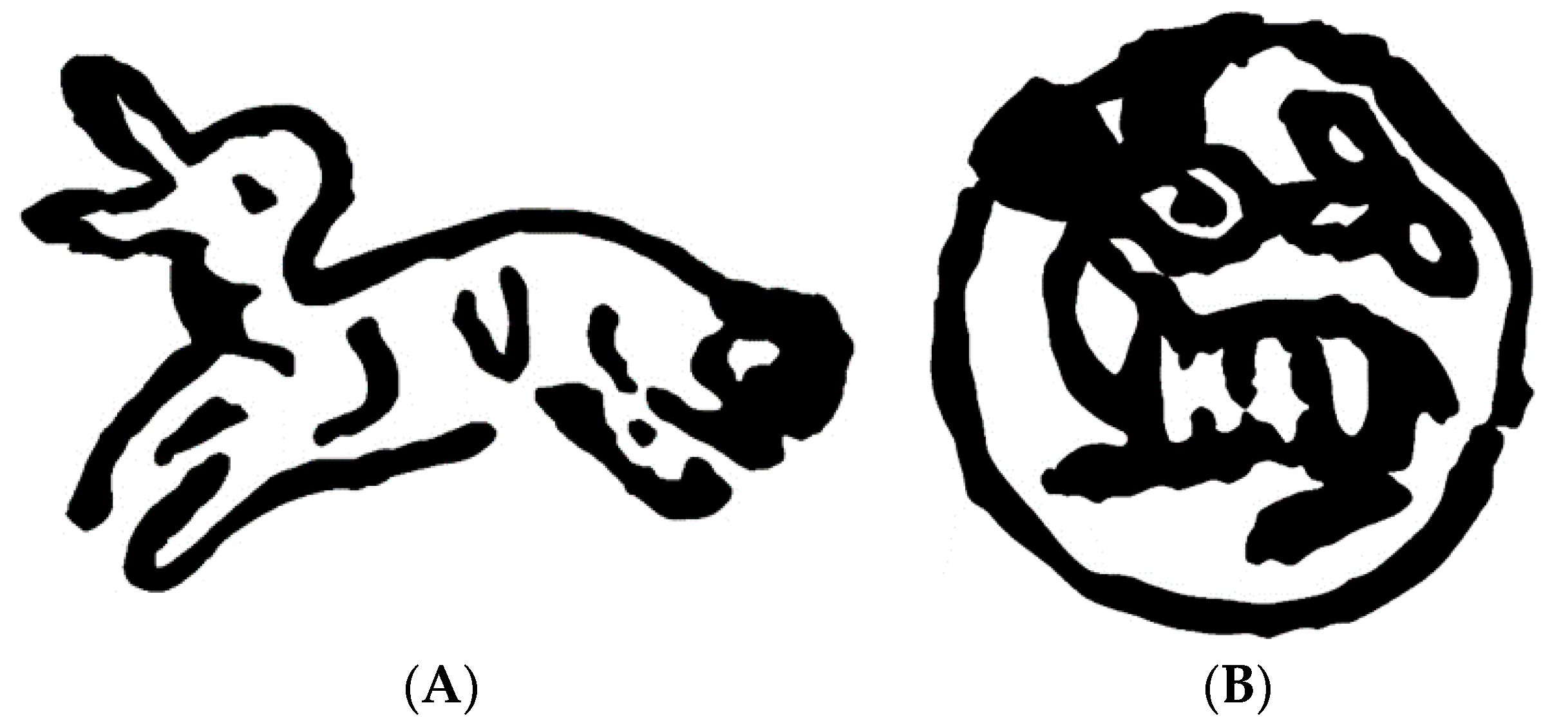

Figure 10.

A Song Yuan Huaya with a Hare motif depicted as an “S” shape. The period of the Song and Yuan Dynasties. Inventory number: 0692. Sketched by author. Picture source: Wen (1995), p. 198.

Figure 11.

(A) A Song Yuan Huaya with a Hare motif and a “Shoutao 壽桃 (the Longevity Peach)” lotus. The period of the Song and Yuan Dynasties. Inventory number: 0694. Sketched by author. Picture source: Wen (1995), p. 199. (B) A Song Yuan Huaya with a Hare motif and a stylistic lotus. The period of the Song and Yuan Dynasties. Inventory number: 0693. Sketched by author. Picture source: Wen (1995), p. 199. (C) A Song Yuan Huaya with a Hare motif and a floral motif. The period of the Song and Yuan Dynasties. Inventory number: 0704. Sketched by author. Picture source: Wen (1995), p. 201. The original collection: Zhuang, Sun. Xue Yuan Cang Yin [《雪園藏印》]. Book of impressions.

Figure 12.

A Song Yuan Huaya with a Hare motif and an ingot. The Song Dynasty. Inventory number: 114. Sketched by author. Picture source: Wang (1990), p. 46.

The last one, namely the hare with the ingot, is among five pieces identified with a reliable archaeological record to be Song Yuan Huaya, which makes it a rare case, because in Song Yuan Huaya studies, the archaeological record and curation information are generally insufficient. This piece was excavated from a ruin called Tongwan City 统万城, which has another name, Baichengzi 白城子 (the White City). The ruin lies in the central-southern area of the present-day Inner Mongolia province of China (Figure 13). It belongs to the Ordos region and has been considered to be “always the political and military centre in the south of the Ordos Plateau, since the day it was built, and remains so all the way through the Northern Wei 北魏 (386–534 CE), the Western Wei 西魏 (535–557 CE), the Northern Zhou 北周 (557–581 CE), the Sui 隋 (581–618 CE), the Tang, and the Five dynasties 五代 (907–960 CE)”.43 Although the exact historical date when this city was abandoned is debated in the field, there is common sense agreement that after the decree of abandonment promulgated by the North Song government, the city declined, not only in its population, but also in political and economic power.44 Nevertheless, its important role as the hub of the Xiazhou 夏州 route of the Silk Road began when it was founded by the famous Emperor Wulie of Xia 夏武烈帝: Helian Bobo 赫連勃勃, in 413 CE, and continued through the Five Dynasties and the Western Xia periods.45 In that sense, the piece with the hare motif excavated in Tongwan City can legitimately be considered the predecessor of other pieces of this kind in Song Yuan Huaya. Furthermore, their artistic styles are overtly consistent.

Figure 13.

Tongwan City and the Ordos Plateau.

The excavations of the remains of Tongwan City uncovered a grand rage of materials from the Han and Jin Dynasties to the Tang and Song Dynasties.46 It is noteworthy that the discoveries, including Wadang 瓦當 (decorative tiles), porcelain shards, broken steles, tombs, stone sculptures and bronze seals, yielded evidence of the influence from the Silk Road, or more specifically, the Steppe culture. For instance, along with the tiles inscribed with characters Yonglong 永隆 (prosperous forever), which is a tile prevalent in the early period of the Tang dynasty, there are tiles decorated with a floral motif (usually considered to be the lotus) with a Lianzhuwen 連珠紋 (beaded pattern). The beaded pattern exists at the early stage of Chinese art history, such as on the bronze vessels of the Zhou 周 Dynasty (1046–256 BC). However, some specific forms of the beaded pattern are considered to be imported from the Xiyu 西域 (West region), namely the Silk Road. For example, the beaded pattern on a circular margin of a round disc, surrounding a central zoomorphic motif, such as an eagle, hare, or lion, is usually regarded as a style inspired by Persian art.47 Besides that, the imprint on the bottom of one porcelain vessel, which seems to me more likely to be a Western Xia character, shows the similarity with some of the undecipherable marks observed on Song Yuan Huaya.

Only five seals excavated there and provided by different research resources can be identified as Xiaoxingyin or Song Yuan Huaya. Among them, the turtle-shaped seal with the undeciphered inscription, a square shape seal with an enigmatic pattern, and the abovementioned hare-ingot seal can be attributed to the Song Yuan Huaya. All of the five pieces have relief Yinmian, and slim and round bridge Yinniu 印鈕 (the loop of the seal), which are all elements commonly seen among Song Yuan Huaya. Because Tongwan City has been a multi-ethnic city all through its history, it is not currently possible to decide if these pieces were made by nomadic inhabitants of that city, or by the Central Chinese inhabitants influenced by the Silk Road fashion. Yet in both senses, the Silk Road influences are inevitable. This is also reflected in the artistic style of the hare motif from the piece concerned. It has undeniable traits of Steppe art, which are in contrast with the traditional Jade-rabbit-on-the-moon. For instance, in the old theme of Jade-rabbit-on-the-moon, the rabbit is always depicted as a Jade-rabbit, which refers to its symbolic meaning: pure, auspicious, and a domestic pet possessed by Chang-e 嫦娥, a fairy living on the moon. By contrast, the hare seal in question represents a mammal species called the Tolai hare, or in Chinese: Menggutu 蒙古兔 (Mongolian hare). The Tolai hare has a longer body, and a longer and flatter tail, while the Jade-rabbit has a rounder and shorter body and a ball-like, fluffy tail. Moreover, unlike the pure-white body hair that the Jade-rabbit is famous for, the Mongolian hare has a yellow-brown coat and white belly hair, and sometimes it has stripes on its body.

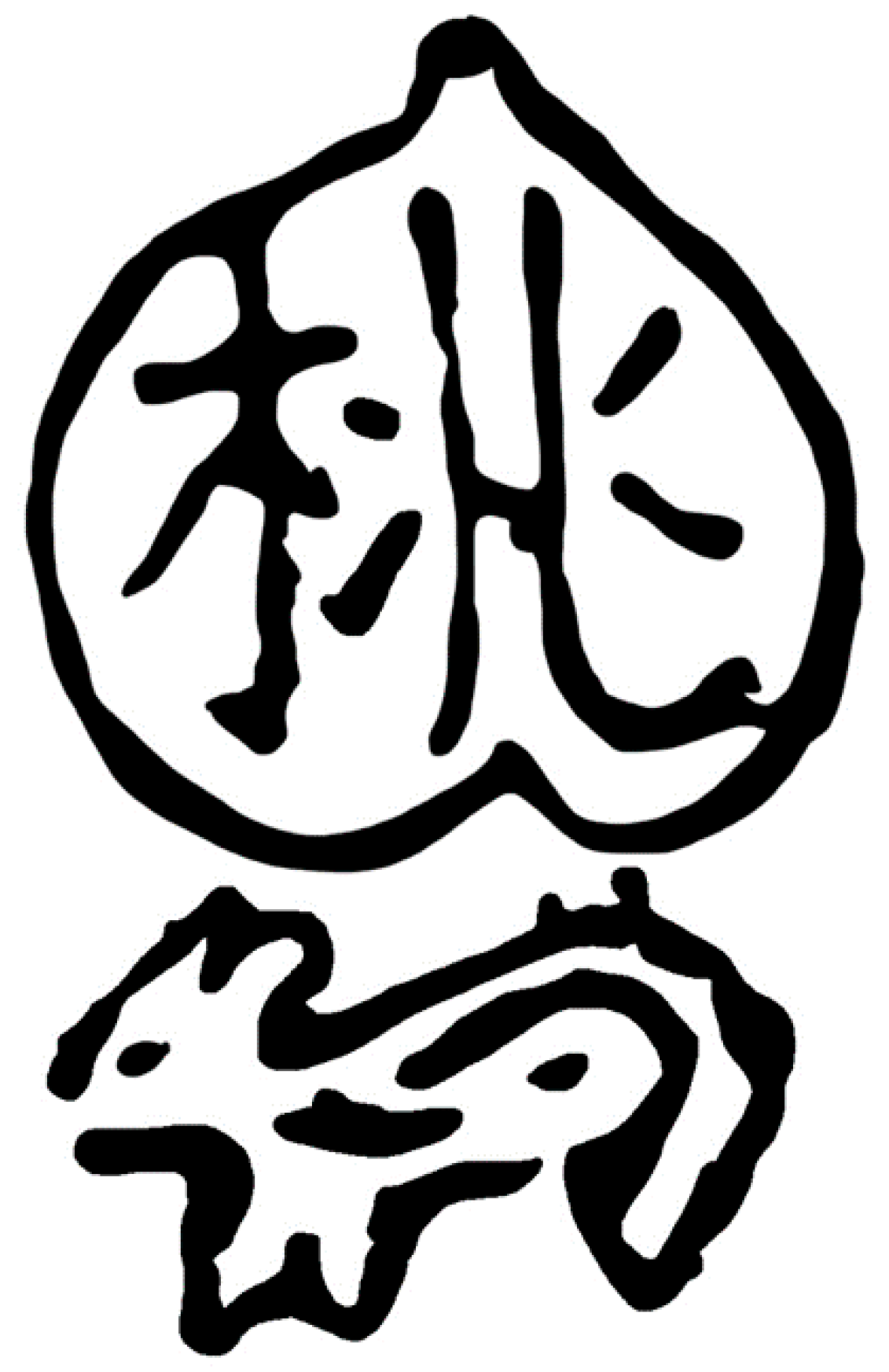

Without further archaeological information, it is hard to decide on the chronological sequence for the abovementioned Tongwan City hare-ingot seal and the seal of the hare-lotus combination. The artistic style that these two hare motifs share in common is obvious, however. Thus, it is justifiable to say that the hare motifs from both kinds of pieces show the vicinity of their workmanship. It is noteworthy that the lotus motif combined with the hare motif is typical among Song Yuan Huaya (Figure 14). I define it as the Shoutao 壽桃 (the Longevity Peach) Style because of its shape and position. Interestingly, there is a piece in the Song Yuan Huaya depicting a peach on the back of a hare (Figure 15), which seems to support this idea. The lotus flower in Shoutao shape are also seen among Mongolian burial art (Figure 16). Thus, the Shoutao Style of the lotus motif shows the possible relation between Song Yuan Huaya (at least part of them) and Steppe art.

Figure 14.

A Song Yuan Huaya with a “Shoutao” lotus and Phagspa characters. The period of the Song and Yuan Dynasties. Sketched by author. Picture source: Shi (1995), p. 55.

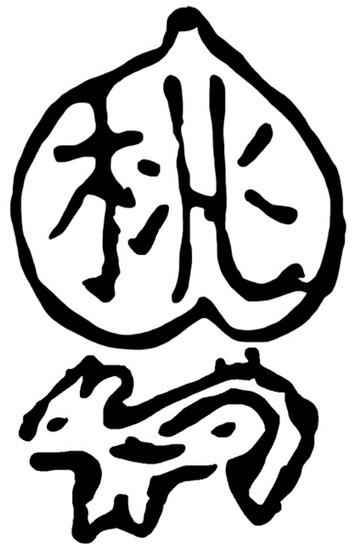

Figure 15.

A Song Yuan Huaya with a peach inscribed with a Chinese character “Tao 桃 (Peach)” on the back of a hare. The period of the Song and Yuan Dynasties. Sketched by author. Picture source: Shi (1995), p. 58.

Figure 16.

A tomb stone from Mongolian culture with a “Shoutao” lotus. The Yuan Dynasty. Sketched by author. Picture source: Tjalling and Wei (2005), p. 169.

In conclusion, one can argue that the hare piece, along with the other two pieces excavated from Tongwan City, are representatives of the Song Yuan Huaya, and because of their unique artistic style and archaeological context, they are evidence for the influence of the Silk Road on Chinese seals.

3.3. The Hu Pipa 胡琵琶

Pipa 琵琶 is the most commonly seen musical instrument among the Song Yuan Huaya. The analyses of different origins, genres, and characteristics of Pipa would, echo to the other case studies in this paper, reveal the strong influences of Silk Road in the Song Yuan Huaya.

The musical instrument seals found among the Song Yuan Huaya are mostly in the shape of Pipa, a very interesting musical instrument which has a history in China of more than two thousand years.48 Different trends and shapes can be observed from material cultures such as the Dunhuang Grottos. The earliest Pipa was allegedly the Qin Pipa 秦琵琶, which was welcomed during the Qin 秦 (221–206 BC) and the Han Dynasties.49 Its shape, musical mechanism, and playing method are all different from the Hu Pipa 胡琵琶 (Foreign Pipa), which was imported firstly to Xinjiang 新疆 and Gansu 甘肅 via the Silk Road, later reaching Central China in the Southern and Northern Dynasties 南北朝 (439–589 CE), and becoming highly prevalent during the Sui and the Tang dynasties.50 After that, the Hu Pipa continued to develop and disseminate through the Song, Yuan and Ming Dynasties and eventually became the standard of modern Pipa. On the other hand, the Han Pipa gradually moved out of the Pipa stage and ended up with the name of Ruanqin 阮琴 or Ruanxianqin 阮咸琴, a musical instrument allegedly named after its master player Ruanxian 阮咸,51 and, when it reappeared during the Song Dynasty, received the new name of Sanxian 三弦.52

Compared to the Qin Pipa, the body of the Hu Pipa is pear-shaped, or water-drop shaped (Figure 17). In contrast, Qin Pipa has the distinguishably smaller and rounder body, with both front and back faces of the body covered with leather, and a longer and narrower neck (Figure 18). When playing the Pipa, the Hu Pipa is held more horizontally. According to current Pipa studies, the Hu Pipa, especially the one with the crooked neck, is evidence of Silk Road influences. The book of Sui 隋書 makes the following statement: “The musical instruments such as crooked neck Pipa and vertical head Konghou 箜篌 of nowadays are all from Xiyu while not the traditional ones of Huaxia 華夏 (China).”53 The book of Tongdian 通典 mentions in relation to this kind of Pipa that the “crooked neck (Pipa), originated from Hu (foreign origin), allegedly was made in China during the Han dynasty.”54 Weiping Zhao investigated the possible origin of the crooked neck Pipa with its four pegs, stating that: “the development flow of the crooked neck Pipa with four pegs should be considered as being disseminated from Gandhara to the Sasanian Persia, then to Yutian 于闐 (in the present day Xinjiang province), and finally to Central China.”55

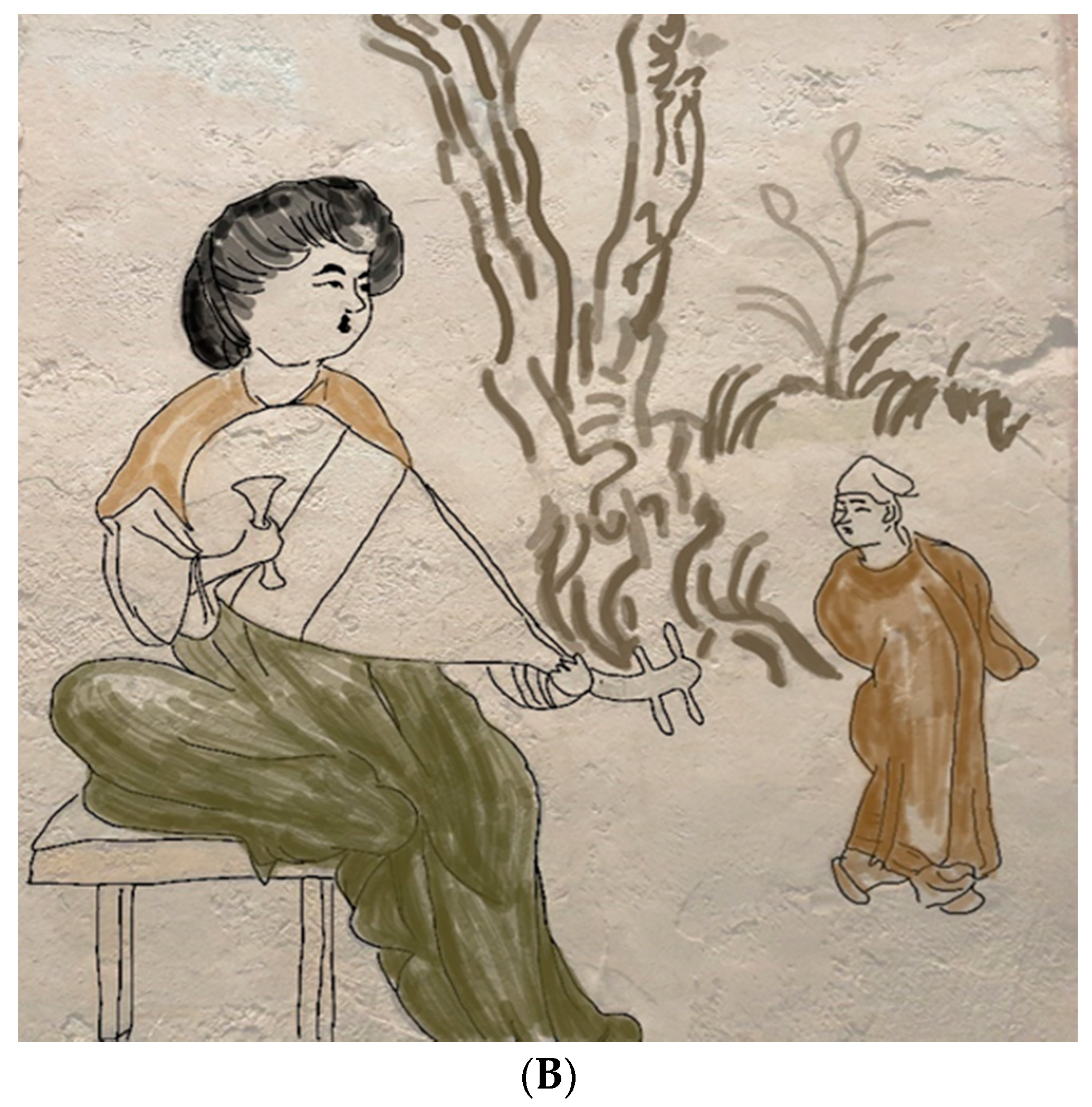

Figure 17.

(A) Part of a mural painting of Kizil Grotto with a depiction of the Hu Pipa, chamber no. 38. The middle of fourth century to the end of fifth century, CE. Sketched by author. Picture source: Zhao (2003), p. 40. (B) Part of a mural painting of the tomb Nanliwang 南里王 village with a depiction of Hu Pipa. The Tang Dynasty. Sketched by author. Picture source: Shaanxi History Museum.

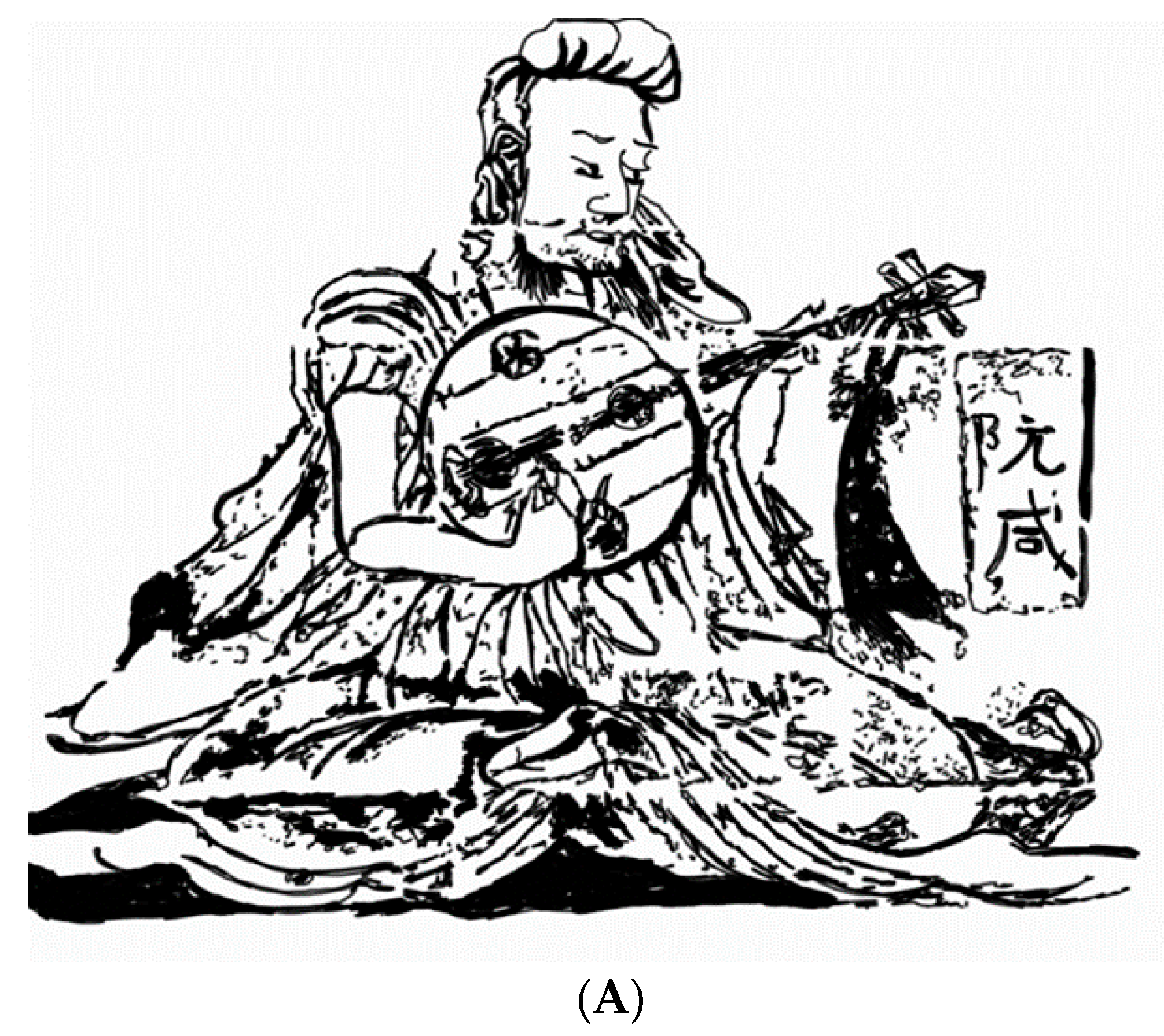

Figure 18.

(A) Part of a mural painting from a tomb discovered from Xishanqiao 西善橋, Nanjing 南京, depicting Ruanxian playing the Qin Pipa—Ruanxian Qin. The early period of the South Dynasty 南朝 (439–589 CE). Sketched by author. Picture source: Zhang and Zhongguo Yinyue Wenwu Dxi Editorial Committee (1996a). (B) Part of a relief of a Qin Pipa from a tomb discovered in Huangguan Shan 皇冠山, Fujian 福建, chamber number: 19. 378–512 CE. Sketched by author. Picture source: Zhang and Zhongguo Yinyue Wenwu Dxi Editorial Committee (1996b). (C) Detail from an urn decorated with musicians holding a Qin Pipa discovered in Ruian 瑞安, Zhejiang 浙江. The Wu State 吳國 of the period of the Three Kingdoms 三國 (220–280 CE). Sketched by author. Picture source: Yu (1992).

There is no identifiable piece of Huaya with depiction of Qin Pipa among the currently provided materials, although Qin Pipa did not disappear from China, even after the prevalence of Hu Pipa. Before new evidence emerges, this situation could be regarded as side evidence supporting the current hypothesis that the Song Yuan Huaya, as a form of art, was born in the dialogue between the Xiyu cultures and the Chinese seal tradition. The existing study in this field only emphasizes the existence of Pipa in Song Yuan Huaya, and that Pipa is one of the Chinese traditional instruments, and hence missed the chance to investigate further the configuration of the abovementioned dialogue in Song Yuan Huaya.

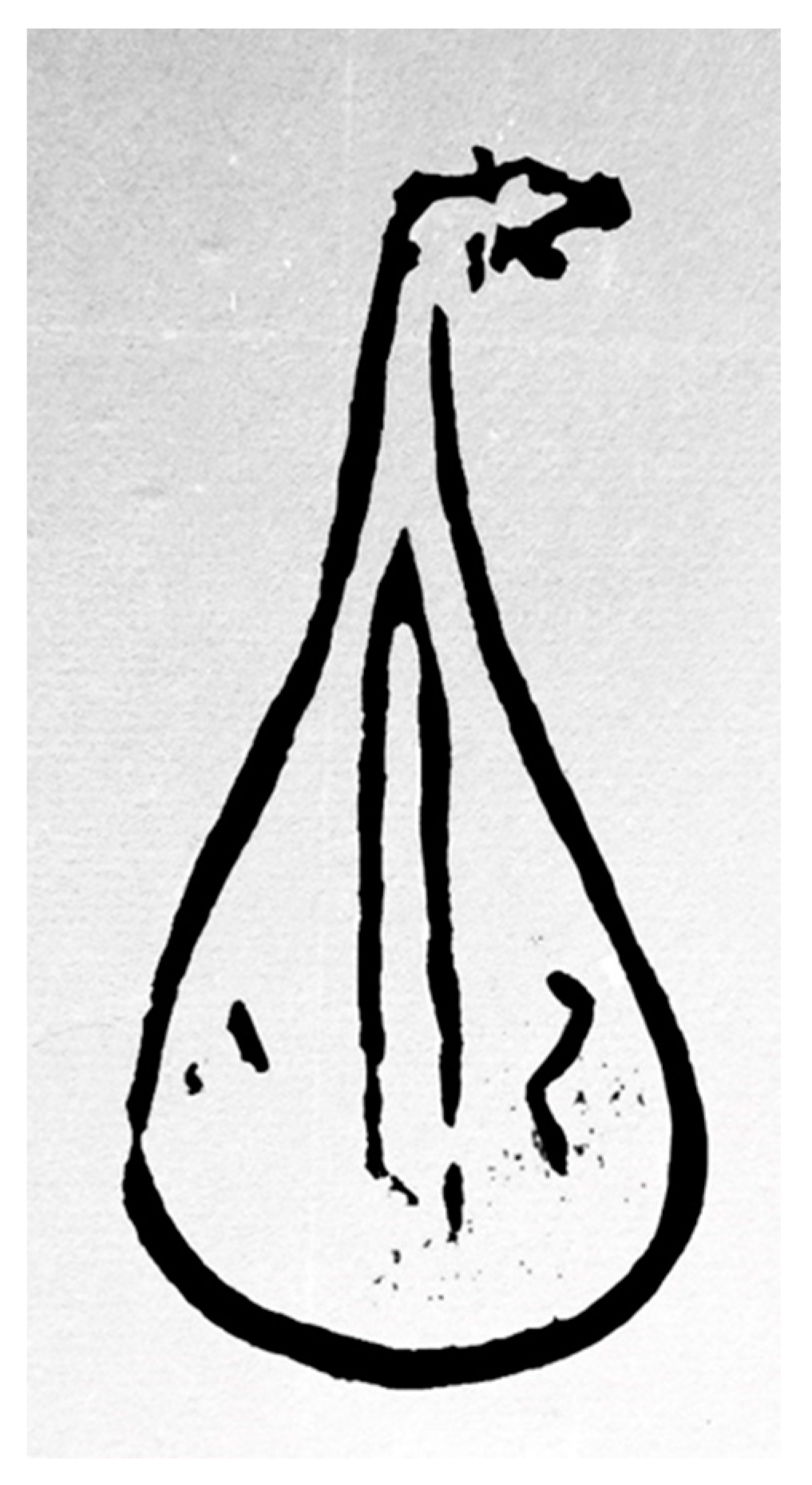

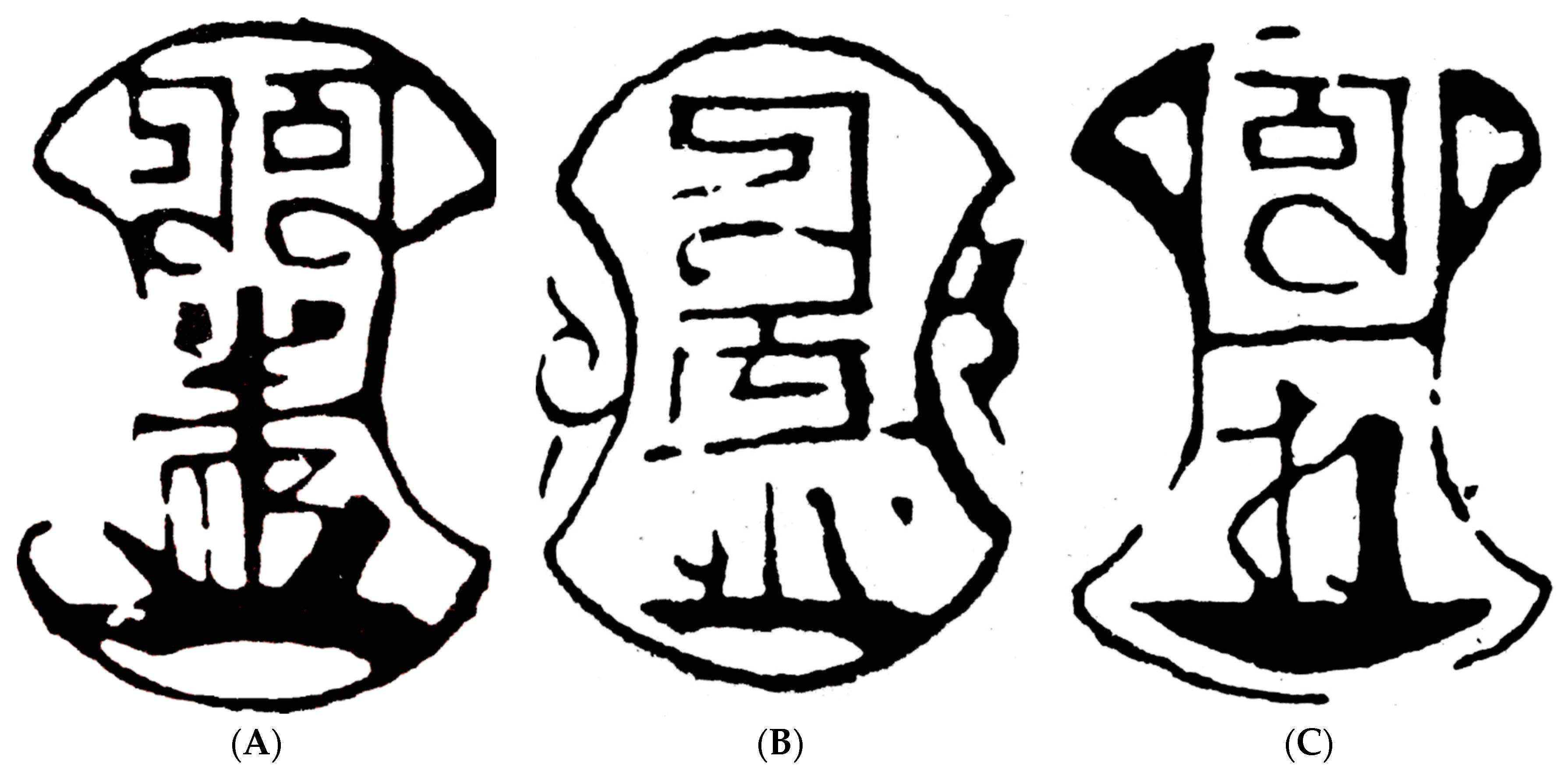

The Song Yuan Huaya, in the shape of Hu Pipa, can mainly be categorized into two groups: One with the straight, but relatively shorter neck, four pegs (four strings), pear-shaped body and soundboard (Figure 19); and the other with a crooked and relatively longer neck, two or four pegs (two or four strings), a relatively narrower and slimmer pear-shaped body and soundboard (Figure 20). Due to the minimalistic artistic style and sometimes worn-out condition, it is not clear if any of the pieces have frets, which is unfortunate, because the presence of frets could be considered a dating criterion, since most of the Pipa with frets are no earlier than the Song dynasty.5657 It is also noteworthy that on some straight neck Pipa pieces, there are Phagspa inscriptions (Figure 19) on their soundboards, which indicate that these pieces, bearing the influence of Xiyu, are no earlier than the Yuan Dynasty.

Figure 19.

A Song Yuan Huaya in the shape of Hu Pipa with straight neck. The period of the Song and Yuan Dynasties. Inventory number: HKU.m.61.937. Copyright © the database of the University Museum and Art Gallery of the University of Hong Kong.

Figure 20.

A Song Yuan Huaya in the shape of Hu Pipa with crooked neck. The period of the Song and Yuan Dynasties. Inventory number: 1883. Sketched by author. Picture source: Wen (1995), p. 439. The original collection: Cheng, Conglong. Chenglijiang Yinpu [《程荔江印譜》]. Book of impressions. 1927.

As for the crooked-neck Pipa, currently there are no Phagspa inscriptions on them. Usually their soundboards are decorated only with abstract (Figure 20) and circular lines (Figure 21). Compared to the more diverse elements on the straight-necked Pipa, such as Phagspa characters, Chinese characters, and even one depicting a human figure holding an umbrella standing next to a stele or tombstone, the design of the crooked-necked Pipa is far simpler and more consistent.58

Figure 21.

A Song Yuan Huaya in the shape of Hu Pipa with crooked neck and abstract motif. The period of the Song and Yuan Dynasties. Inventory number: HKU.m.61.936. Copyright © the database of the University Museum and Art Gallery of the University of Hong Kong.

At the current stage, it is clear that, first of all, only Hu Pipa is abundantly seen in Song Yuan Huaya; secondly, there is no overtly mixed form of the crooked neck with four pegs and the straight neck with four pegs; and thirdly—also most importantly—among the crooked neck Hu Pipa with four pegs identified as having Sasanian Persian origin, there is no explicit sign of Central Chinese culture, and no dating indication to the Yuan dynasty either. In other words, we can only be sure that these pieces with a crooked-necked Pipa shape are more Xiyu influenced or that they originated from the Silk Road cultural milieu, rather than having the style of Central China. If they were indeed produced and/or used in the Yuan Dynasty, this would suggest a propensity for a Xiyu-orientated taste among those Song Yuan Huaya patrons, workmen and users.

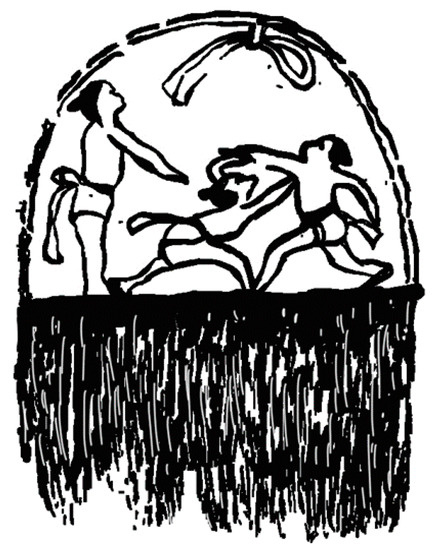

3.4. The Wrestling Scene

Although the Song Yuan Huaya depicting a wrestling scene gives an impression of Mongolian style at first sight, we still cannot determine it to be unmistakably of Mongolian origin unless we can differentiate it from other wrestling-themed seals, for example, those seals from the Han Dynasty carved with Jiaodi 角抵 or Jiaodi Xi 角抵戲 (Jiaodi drama), which is the name for traditional Central Chinese wrestling and wrestling drama, respectively. The analyses here will reveal that the Huaya with wrestling scene depiction in the Song Yuan Huaya is undoubtedly from Mongolian tradition.

The Jiaodi started its history in Central China from the Pre-Qin Period (before 221 BC), yet the material evidence of the Jiaodi, such as steles, tiles and seals from before the Warrior States Period are very scarce.59 Most of the evidence available nowadays is from the Han and Tang dynasties. However, some textual records provide clues for the existence of Jiaodi as a performance during the Warrior States period. For instance, the chapter “Lisilie Zhuan 李斯列傳” in the book, Shiji 史記, states that at that time the performance of Jiaodi was taken as a part of the martial art liturgy, and was granted the name Jiaozi in the Qin dynasty.60 During the Qin and the Han Dynasties, Jiaodi developed out of the field of martial art, into a form of drama performance,61 and finally became one drama of the prosperous category of Baixi 百戲 (hundreds of dramas) during the Han Dynasty. Thus, the term Jiaodi in China is an inclusive one, and hence wrestling is just one performance out of many in Jiaodi, and when it is performed, dance, juggling, music and many other elements are added, eventually making it into a traditional drama.62 Despite the fact that it had always been criticized by the Shidafu 士大夫 (scholars and literati), the popularity of Baixi in the court and military during the Han and Tang Dynasties, continued to the Song Dynasty, where it was greatly promoted among the lay people.63 That situation changed in the Yuan Dynasty. Because of political concerns, the court of the Yuan dynasty banned the practices and performance of Jiaodi along with other martial arts among lay people, mainly the people of the Han ethnicity, although, like any other edict, it may not have thoroughly extinguished the practice from folk culture, even though it indeed affected the development of Jiaodi in a negative way.64

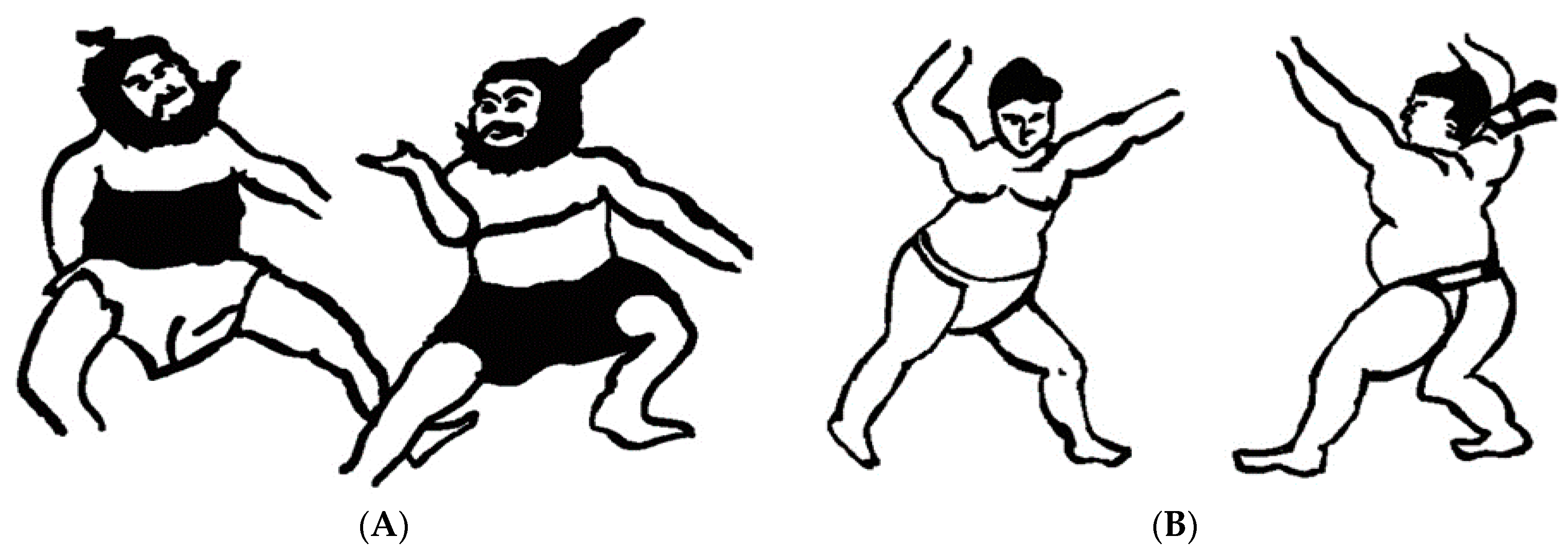

So far, only two Xiaoxingyin from the Han Dynasty stored in the Palace Museum depict Jiaodi or Jiaodi Xi (Figure 22).65 Some other co-related depictions are available, for instance, in the form of mural paintings from the Han and Tang dynasties (Figure 23), and a wooden comb from the Qin dynasty (Figure 24). It is obvious that although the depictions of Jiaodi on these materials seem different from each other, some shared traits can also be found. For instance, in the depictions, the upper bodies of the participants in Jiaodi are usually naked, while the lower bodies wear short pants of different kinds, with hair tied into buns on the top or back of heads. This trait is in accordance with the textual record of the Jiaodi as a drama before the Song dynasty. The book Tang Yin Kui Qian 唐音癸簽 mentions that in the Tang Dynasty, Jiaodi as Jiaodi Xi was the kind of drama performed after all the other dramas were finished; in other words, it was similar to an epilogue, and in this epilogue military drums would be played, and strong naked men would be introduced to the arena to perform the Jiaodi as a competition.66 The two Xiaoxingyin with Jiaodi depictions do not clearly show the detail of the costume, but it is still apparent that the participants on one seal seem to be completely naked, and those on the other seem to have short pants and decorated jackets. At this stage, it is sufficient to say that the most common characteristic of the Jiaodi or Jiaodi Xi costume is the short pants, no boots (although sometimes it seems that shoes are involved) and no hat.67

Figure 22.

The Xiaoxingyin depicting the scene of Jiaodi. The Han Dynasty. Inventory: 78 and 79. Sketched by author. Picture source: National Palace Museum (1984), pp. 79–80.

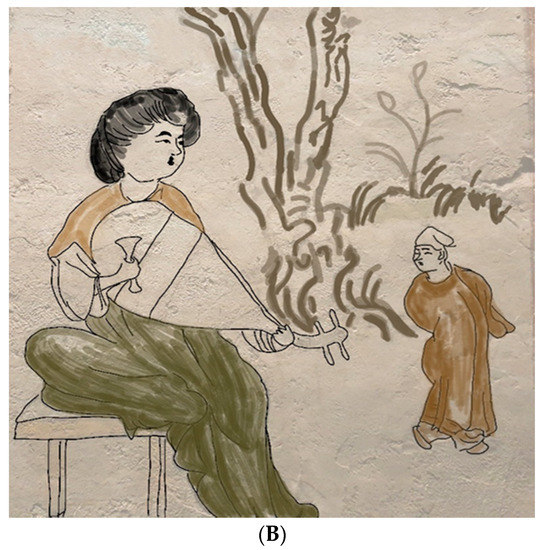

Figure 23.

(A) Part of a mural painting depicting the scene of Jiaodi. The Han Dynasty. Sketched by author. Picture source: Liu (1985), p. 9. (B) Part of a silk painting depicting the scene of Jiaodi. The Tang Dynasty. Sketched by author. Picture source: Liu (1985), p. 10.

Figure 24.

A wooden comb discovered in Jiangling 江陵, Hubei湖北, decorated with the depiction of the scene of Jiaodi. The Qin Dynasty. Sketched by author. Picture source: Liu (1985), p. 9.

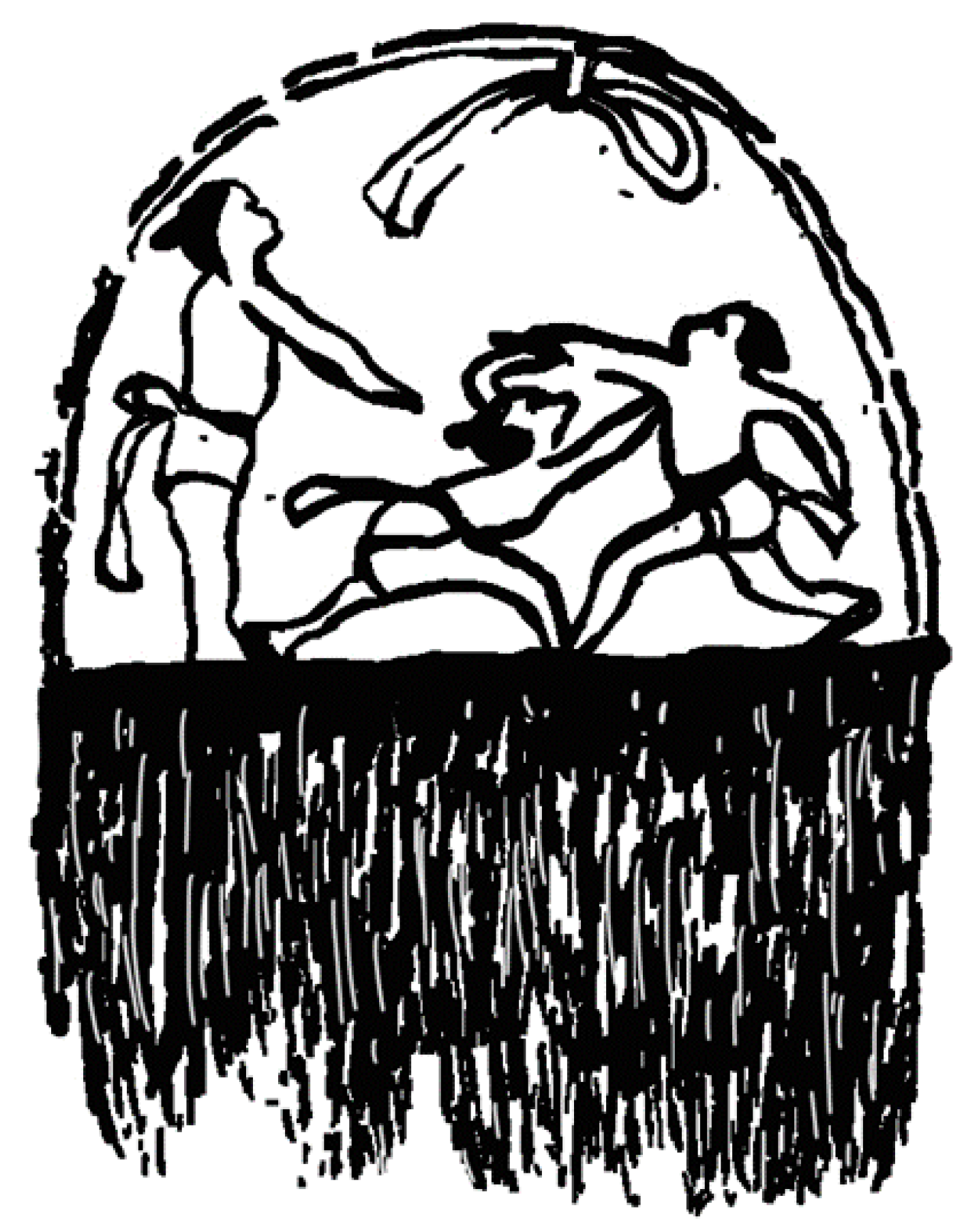

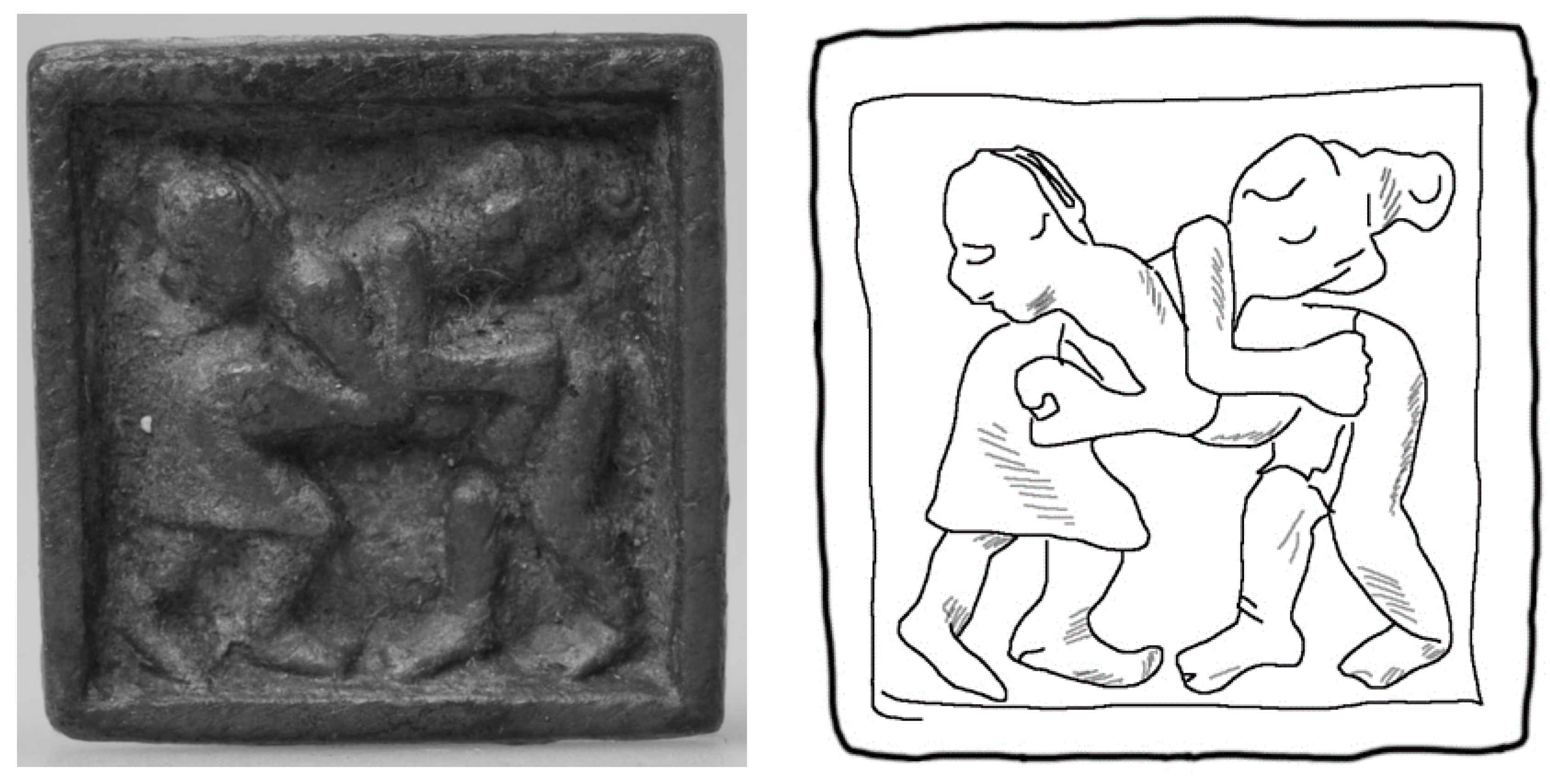

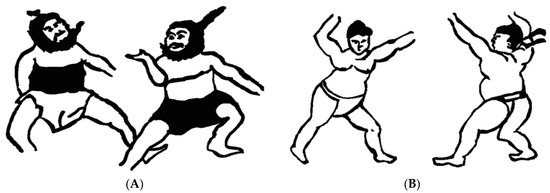

When comparing and contrasting the abovementioned Jiaodi or Jiaodi Xi depictions with the Song Yuan Huaya piece in question (Figure 25), and with another piece excavated from Xi‘an of the late Warrior States period, which is considered by scholars a possible heritage of the Xiongnu Ren 匈奴人 (Figure 26),68 it is clear from the costumes and the iconographical purpose that these two groups of depictions represent two different activities.

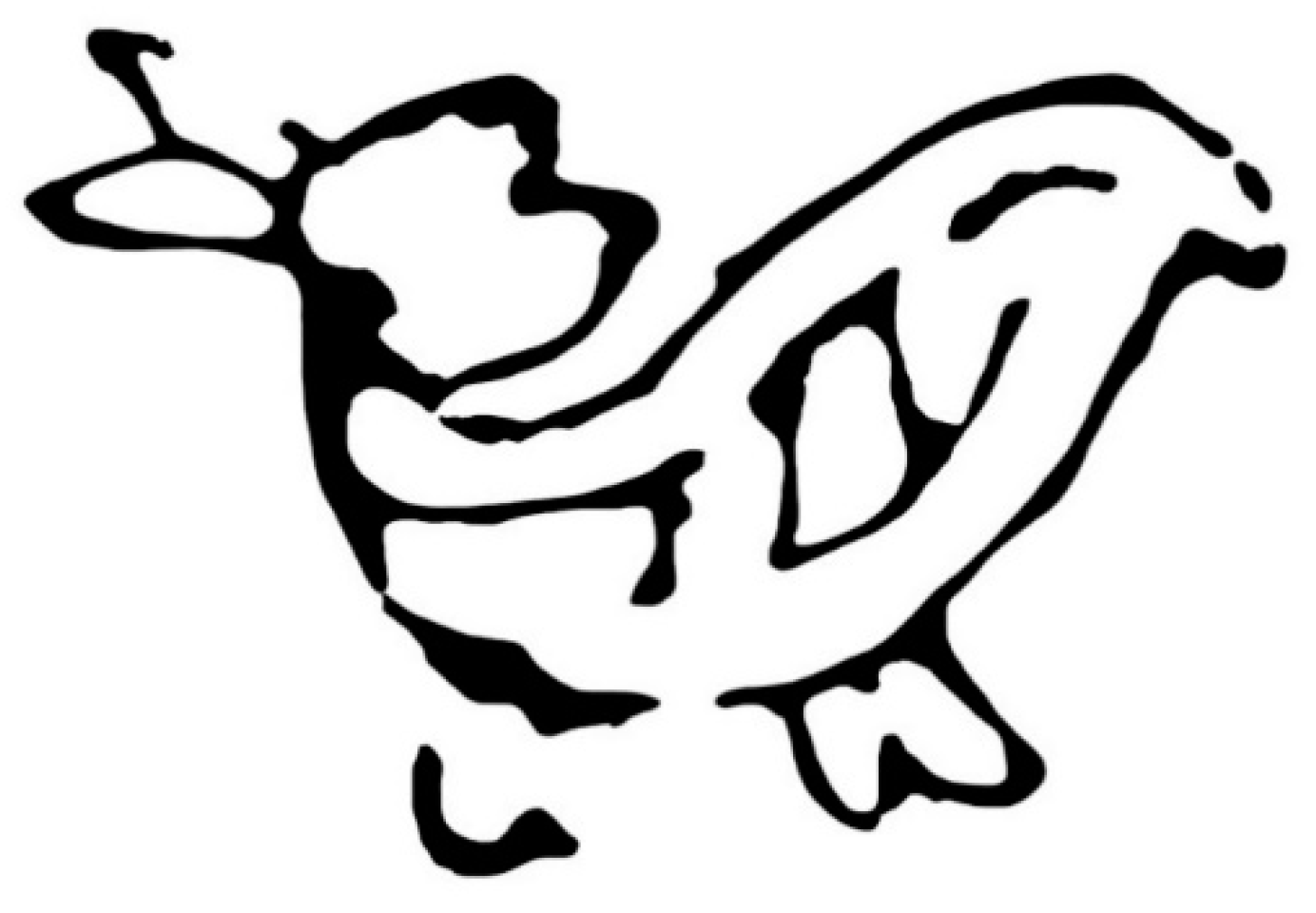

Figure 25.

A Song Yuan Huaya with the depiction of Mongolian Bukh. The period of the Song and Yuan Dynasties. Inventory number: HKU.m.61.899. Sketched by author. Copyright © the database of the University Museum and Art Gallery of the University of Hong Kong.

Figure 26.

A bronze plate carved with the depiction of wrestling in Xiongnu style. The late period of the Warrior States. Sketched by author. Picture source: Cui (2003), p. 118.

The depiction of Jiaodi and Jiaodi Xi, as shown by the abovementioned Xiaoxingyin, mural painting, and artefact, is much more diverse and dynamic. Moments of winning, struggling, and saluting each other before the activity, etc., are all captured in these depictions, and more importantly, in some cases, a third person (usually identified as the referee of the game) is present. On the other hand, the costumes of the Song Yuan Huaya depiction consist of pants, boots, and a decorated pointed hat, which are more akin to the costumes of both ancient and modern Mongolian wresting, “Bukh”, than to the Jiaodi Xi. Furthermore, it is likely that these costumes are the Mongolian Northern Desert style of wrestling rather than the Southern Desert style because of the pointed hat and lack of ribbons.69 The depictions of the material concerned always have two figures occupied in a symmetric wrestling “hug”, with the upper bodies bending toward each other to form an arc in the composition. This is more obvious if we introduce similar depictions of this kind of wrestling here as side-evidence, for instance, the mural painting piece from Ji’An 集安 of Jilin 吉林 Province (Figure 27), also located in the Steppe culture region (Figure 28), where the later Jurchen, Khitan and Mongolian people and their ancestors had been active since the early stage of the history.70

Figure 27.

Part of a mural painting discovered in Ji’An, Jilin. Third to fourth century, CE. Li (1983), p. 8.

Figure 28.

Jilin province and the Ji’An town.

Although the study of wrestling schools seems relatively weak in the field of Chinese historical sports studies, that is, the study of their geographical, cultural and developmental differences is very inadequate, there are some scholars trying to distinguish Jiaodi and Jiaodi Xi from the art of Bukh (Mongolian wrestling).71

Unlike Jiaodi, the art of Bukh was born in the Eurasian steppe belt and relates closely to the civilization of early tribes in that area long before the Warrior States period.72 Some scholars believe that the sport of wrestling has its roots in pre-historical activities, and could be a transformation of the northern folk dance activity.73 Since the day of its birth, Bukh has been one of the most important liturgical activities of the Steppe People. The Book of the Later Han 后汉书 mentions that early in Ujung’s time, the Ujung people, who are considered to be the ancestors of the Mongolians, used the sport of Bukh as an official method for electing their tribal leaders.74 During the Mongolian period, Bukh became one of three activities held in the annual Naadam festival. As one of the most important traditions of Mongolian people thought to reflect the Mongolian ethos, the whole process of Bukh and its every detail, including the eagle dance, the arena where it is held, and the costumes, are full of symbolic meaning.75

On the other hand, the athletic fighting essence of Chinese Jiaodi dissolved into Jiaodi Xi, the traditional drama. Nevertheless, under the influence of the Silk Road, the Hun and later Mongolian Bukh became mainstream wrestling in China, especially during and after the thirteenth centuries,76 when the powers of Steppe peoples were thriving and giving birth to nations such as the Liao 遼 (907–1125 CE), Jin and Western Xia Dynasties in the Northern region of China. All of them praised Bukh highly in their traditions.77

From the above comparison and contrast, it is legitimate to say that, similar to the Pipa case, the wrestling scene of the unique Song Yuan Huaya piece should be identified as a depiction of the art of Bukh, Mongolian wrestling, rather than of the traditional Han Jiaodi or Jiaodi Xi. It is noteworthy that the artistic characteristic of the Bukh seal is in accordance with Song Yuan Huaya characteristics. For instance, the carved scene is in Zhuwen, the style of the figures is succinct, symmetrical and naturalistic. Like other figure depictions, the loop of the piece (the round holder on the back) in question is identical to other Song Yuan Huaya loops, etc. All these factors can show that Steppe culture played an important role in the birth and prevalence of Song Yuan Huayin. There are many cases beside those I have outlined here that can serve as evidence, for example, the abundantly-found swastikas, and a piece depicting an anthropomorphic bird similar to the “fire-bird” figure discovered at the Yuhong Tomb 虞弘墓 of the Sui Dynasty, which has been closely related to a nomadic people called Rouran 柔然, who surrendered to Northern Wei sovereignty.78

3.5. Some Ethnic Characters

The study of the inscription is an area in seal study that cannot be neglected. This paper, following the principle of the field, will introduce the most correlated and important inscriptions here.

As mentioned above, except for the free design of shapes, thematic motifs, and Phagspa and Chinese characters, there are also characters/symbols which are regarded by mainstream studies as unidentifiable “Shaoshu Minzu Wenzi 少數民族文字 (minority ethnic characters)”.79 I cannot agree with this hypothesis, however, because first of all, in my view, the current definition seems unable to free itself from possible Sino-centric inclination. Secondly, and more importantly, the cursory categorization to a group of unidentifiable symbols may result in neglect of their true identity. For example, as this paper tries to argue that at least some of the characters may originate from Jurchen or Khitan languages from the period of Liao and Jin dynasties, obviously it is not proper to call them “minority ethnic characters”. At that time, these were independent nations founded by Steppe peoples in the west-north and east-north areas of nowadays China. Furthermore, examination reveals that the formatted usage of the characters in the Song Yuan Huaya in question may reflect the fact that the existence of those characters in a Yinzhi 印製 (the style of the seal) of the Qin-Han tradition is more likely an artistic fashion embraced by “Hanren 漢人”, rather than a semantically accurate expression of specific ethnic identity. Hopefully such a conclusion can serve as the basis for further discussions, for instance, of the overall attitude toward the Steppe culture heritage among the “Hanren” during the Yuan dynasty, and how the influence of the Silk Road altered the art forms in the Yuan Dynasty differently from the way it did in earlier periods, such as Tang (which works on the art form intensively for the first time in Chinese history), and the significance of that difference.

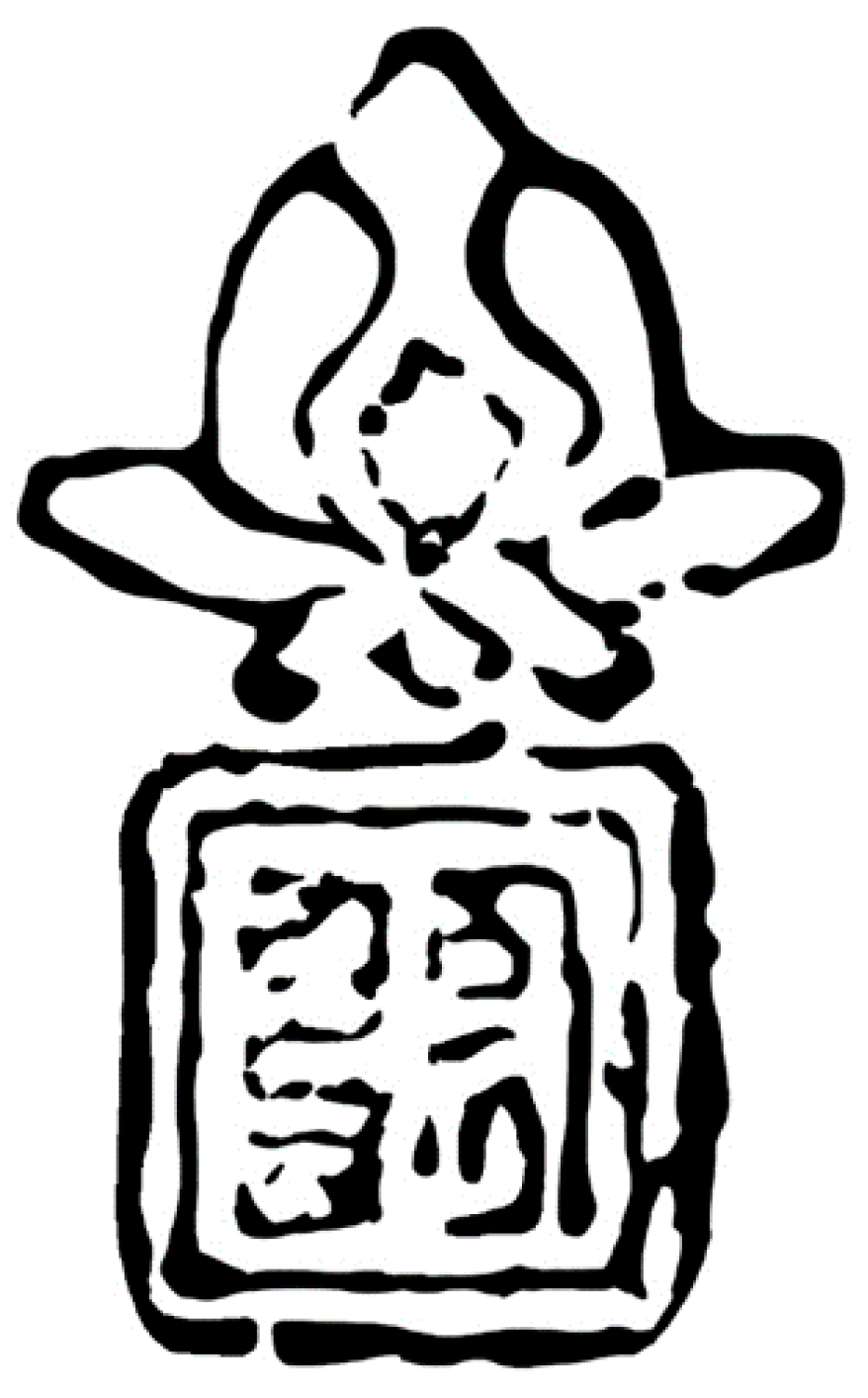

When introducing the Jurchen/Khitan characters, we should start with the question “Ji”. Among the Phagspa inscriptions, there is the most commonly seen Phagspa character, “ꡂꡞ”, which can be translated as “Ji”. In fact, Phagspa is the only language so far identified by scholars in Song Yuan Huaya studies. There is also the Chinese character, “Ji”, written as “記”, found abundantly in Song Yuan Huaya. Their composition, and combination with other elements and the Yinzhi, are all similar to those of the Phagspa Ji.

In Chinese seal history, there are different traditions for naming a seal, and the name of the seal usually appears on the Yinmian. One of the functions is to indicate the ownership of the seal. The earliest character inscribed on Yinmian with that purpose is “Xi” 璽. Following Xi, there comes “Yin” 印 and “Zhang” 章. The first combination of Yin and Zhang, namely the phrase “Yinzhang” 印章, appears during the early period of the Han dynasty. The term “Ji”, functioning similarly to Yin and Zhang, was commonly found on the Guanyin 官印 (official seals) in the Tang Dynasty, and on both official and private seals in the Song Dynasty.80 Nevertheless, the extensive existence of “Ji” in Song Yuan Huaya, in Chinese or in Phagspa, can illustrate that, in general, the tradition of the employment of “Ji” was not a new invention of Song Yuan Huaya, but an inheritance and development of an old tradition.

The use of the Phagspa character ꡂꡞ is almost identical phonetically or semantically to that of the Chinese character 記. In other words, the Phagspa ꡂꡞ should be regarded as the transcription of the Chinese 記. Moreover, similar to the Chinese character 記, the Phagspa is, in most cases, combined with a family name. In other cases, it goes with an ethnic character or an abstract pattern.

Compared to other seal genres in the long history of China, only in Song Yuan Huaya, are the non-Chinese elements so abundantly introduced to seals of the Han tradition. In the past, due to the difficulties in interpreting the characters/motifs, the studies usually took the easy route of attributing them as “Ya” assuming that these characters/motifs have no sematic meaning and just serve as substitutes for a personal signature.81 Thus, the idea of “Ya” becomes the origin of the term “Yuanya”. I admit that “Ya” is a good term for the present, since most of the non-Chinese characters cannot be easily interpreted, and in general, they do have the function of “Ya” or “Ji” on the seals. However, with the development of the study, we cannot be satisfied just knowing that these characters belong to the “Huaya” family, but should instead proceed to investigate their specific meanings and identities. Thanks to the development of ethnic linguistic studies, some of the ethnic characters are now more accessible for interpretation.

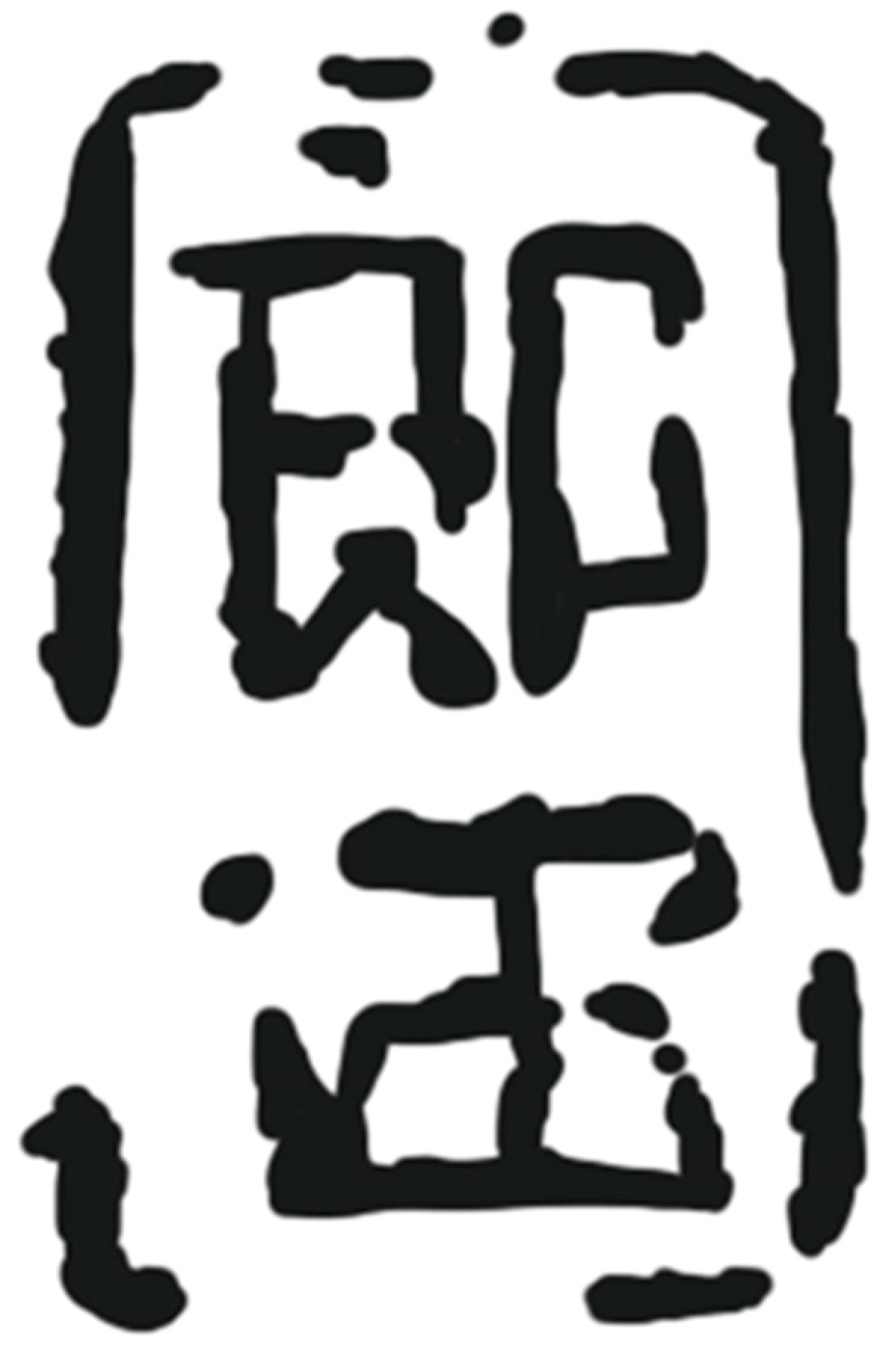

The designs with ethnic characters in Song Yuan Huaya have two compositions: One is a formatted design with one short thin line on the top of the character and another much thicker line on the bottom (A type, Figure 29). The other is absolutely free with no given pattern to the character (B type, Figure 30). Most of the Song Huaya are made of jade with luxurious Niuzhi 紐制 (the shape of the loop on the back), for example, a dragon shape implying a connection to the upper class or even royal family. The material, the shape, and the design—for instance, the proportion of the lines, the clearness of the curve, and the artistic value of the calligraphic style—are all consistent and exquisite, and seem to be a rigorously executed format. However, during the later periods, such as the Yuan Dynasty, type A became stylistically irregular, free in combinations, and sometimes cursorily carved (Figure 31). In other words, it was no longer a fixed format for making high class private seals, but became a fashion welcomed by lay people and hence transformed into free art expression. In that sense, the abovementioned B type could be a later development of the A type.

Figure 29.

The Song Yuan Huaya with two short lines (A type). The Song Dynasty. Sketched by author. Picture source: Shi (1995), pp. 4, 7.

Figure 30.

The Song Yuan Huaya in free style with two short lines (B type). The period of the Song and Yuan Dynasties. Sketched by author. Picture source: Shi (1995), pp. 52, 59.

Figure 31.

The Song Yuan Huaya in free style with two short lines. The Yuan Dynasty. Sketched by author. Picture source: Shi (1995), pp. 46, 52, 60.

The combinations of the ethnic character(s) with other elements are in free style. The frequently-occurring combination is with Chinese characters, usually with family names (Figure 32) and auspicious idioms (Figure 33). Sometimes the character also pairs with the Phagspa character (Figure 34) and motif (Figure 35). Furthermore, they can appear alone on Yinmian, with or without the frame (Figure 36). The identification and categorization of the ethnic characters are complicated and requires linguistic expertise. Due to the limitations of this paper, only two will be mainly discussed here: One is the Jurchen character written in multiple forms and the other might have a Khitan origin and has more than one interpretation.

Figure 32.

The Song Yuan Huaya carved with the combination of a Chinese character (a family name) with an ethnic character. The period of the Song and Yuan Dynasties. Sketched by author. Picture source: Shi (1995), pp. 22, 30.

Figure 33.

(A) A Song Yuan Huaya carved with an ethnic character and an auspicious idiom. The period of the Song and Yuan Dynasties. Inventory number: 1689. Sketched by author. Picture source: Wen (1995), p. 402. (B) A Song Yuan Huaya carved with an ethnic character and an auspicious idiom. The period of the Song and Yuan Dynasties. Sketched by author. Picture source: Shi (1995), p. 54.

Figure 34.

(A) A Song Yuan Huaya carved with Phagspa characters and an ethnic character. The Yuan dynasty. Sketched by author. Picture source: Shi (1995), p. 52. (B,C) The Song Yuan Huaya carved with Phagspa character(s) and an ethnic character. The Yuan Dynasty. Inventory number: 1852 and 1853. Sketched by author. Picture source: Wen (1995), p. 431.

Figure 35.

A Song Yuan Huaya carved with an ethnic character, and the top end of the character transformed into a bird motif. The period of the Song and Yuan Dynasties. Sketched by author. Picture source: Shi (1995), p. 52.

Figure 36.

The Song Yuan Huaya carved with an ethnic character. The period of the Song and Yuan Dynasties. Sketched by author. Picture source: Shi (1995), pp. 68, 69.

According to Qizong Jin’s Jurchen dictionary and other Jurchen study resources, the character  ,

,  , and

, and  refer to the same Jurchen character. Jin states:

refer to the same Jurchen character. Jin states:

,

,  , and

, and  refer to the same Jurchen character. Jin states:

refer to the same Jurchen character. Jin states:

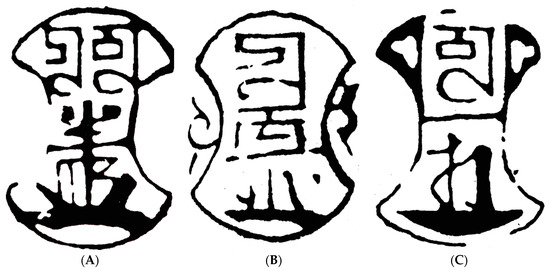

In the third volume of Manzhou Jinshi Zhi 滿洲金石志, Luo, Fuyi 羅福頤 writes: “there is inscription carved on the edge of the Maoke mirror 毛克鏡 of Xianping Fu 咸平府 that: ‘This is officialof Xianping Fu.’” Besides, there is a round bronze seal excavated from the Zhongxing 中興 ancient city of Suibin 綏濱, near to Heilong Jiang river 黑龍江 (Figure 37, added by author), with the character

carved on the position traditionally interpreted to be the Chinese character Yin 印 (seals or stamps). Also, this

is seen on other edges of the mirrors, thus, it should be functionally similarly to the Chinese character “Feng 封”, “Ji”, etc., which are the common characters on seals. As for the accurate pronunciation and meaning of this character, more studies should be conducted on that.

Figure 37. Heilongjiang Province and the Suibin city.

Figure 37. Heilongjiang Province and the Suibin city.

When in some cases the  was presented in a form

was presented in a form  , Jin explains that “it is the transformation form of

, Jin explains that “it is the transformation form of  ……in many bronze mirrors of the Jin dynasty, this character was commonly carved on the edge of the mirrors, yet in a very rudimentary way, and sometimes in the form of

……in many bronze mirrors of the Jin dynasty, this character was commonly carved on the edge of the mirrors, yet in a very rudimentary way, and sometimes in the form of  , or

, or  . They are actually the same character.”83

. They are actually the same character.”83

was presented in a form

was presented in a form  , Jin explains that “it is the transformation form of

, Jin explains that “it is the transformation form of  ……in many bronze mirrors of the Jin dynasty, this character was commonly carved on the edge of the mirrors, yet in a very rudimentary way, and sometimes in the form of

……in many bronze mirrors of the Jin dynasty, this character was commonly carved on the edge of the mirrors, yet in a very rudimentary way, and sometimes in the form of  , or

, or  . They are actually the same character.”83

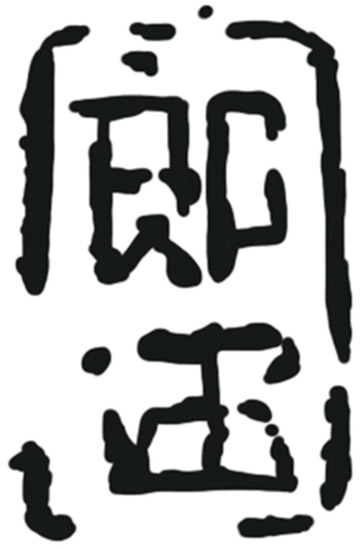

. They are actually the same character.”83The city of Zhongxing that Jin mentions is dated to the middle to late Jin dynasty because some coins of Da Ding Tong Bao 大定通寶 were found there in tomb no. 8.84 The round bronze seal excavated in Zhongxing city with  on it in the Shoujin 瘦金 script, could be among the earliest cases of that character (Figure 38). There is another character found on a stone seal there in the same tomb. It is a stone seal carved with a Chinese character “Lang 郎 (in this case a family name)”85 and a character

on it in the Shoujin 瘦金 script, could be among the earliest cases of that character (Figure 38). There is another character found on a stone seal there in the same tomb. It is a stone seal carved with a Chinese character “Lang 郎 (in this case a family name)”85 and a character  (Figure 39). One thing for sure that this is not the earliest case of

(Figure 39). One thing for sure that this is not the earliest case of  . There are some coins inscribed with four characters including

. There are some coins inscribed with four characters including  (Figure 40), mentioned by different scholars and dealers, which are dated to the Liao dynasty. Although the interpretation of the relevant characters is controversial, one thing is certain and that is that four of the characters are Khitan not Jurchen.

(Figure 40), mentioned by different scholars and dealers, which are dated to the Liao dynasty. Although the interpretation of the relevant characters is controversial, one thing is certain and that is that four of the characters are Khitan not Jurchen.

on it in the Shoujin 瘦金 script, could be among the earliest cases of that character (Figure 38). There is another character found on a stone seal there in the same tomb. It is a stone seal carved with a Chinese character “Lang 郎 (in this case a family name)”85 and a character

on it in the Shoujin 瘦金 script, could be among the earliest cases of that character (Figure 38). There is another character found on a stone seal there in the same tomb. It is a stone seal carved with a Chinese character “Lang 郎 (in this case a family name)”85 and a character  (Figure 39). One thing for sure that this is not the earliest case of

(Figure 39). One thing for sure that this is not the earliest case of  . There are some coins inscribed with four characters including

. There are some coins inscribed with four characters including  (Figure 40), mentioned by different scholars and dealers, which are dated to the Liao dynasty. Although the interpretation of the relevant characters is controversial, one thing is certain and that is that four of the characters are Khitan not Jurchen.

(Figure 40), mentioned by different scholars and dealers, which are dated to the Liao dynasty. Although the interpretation of the relevant characters is controversial, one thing is certain and that is that four of the characters are Khitan not Jurchen.

Figure 38.

A round bronze seal carved with a Jurchen character excavated in Zhongxing City, Heilongjiang. The Jin Dynasty. Picture source: The Heilongjiang Provincial Archaeological Research Team (1977), p. 45.

Figure 39.

A stone bronze seal inscribed with a Chinese character and an ethnic character excavated in Zhongxing City, Heilongjiang. The Jin Dynasty. Picture source: The Heilongjiang Provincial Archaeological Research Team (1977), p. 45.

Figure 40.

A Khitan coin inscribed with four characters. The Liao Dynasty. Sketched by author. Picture source: Wei (1984), p. 62.

One suggestion of the meaning of Khitan inscriptions on the relevant coins that was raised by Jingyan Jia is that the coins should be categorized with the numismatic group of Tian Lu Tong Bao 天祿通寶, because the shape of  resembles the Jurchen character

resembles the Jurchen character  , which is pronounced “Bai”, and hence sounds similarly to “Bao”.86 Fengzhu Liu provides another idea, that they should be read as “Tian Chao Wan Shun 天朝萬順”.87 Based on Liu’s account, Yuewang Wei suggests that the character concerned should be read as “Sui 歲”.88 Naixiong Chen questions all the above interpretations with good reason, and that leaves the meaning and pronunciation of the character undecided. I suggest that there is another clue which should be considered.

, which is pronounced “Bai”, and hence sounds similarly to “Bao”.86 Fengzhu Liu provides another idea, that they should be read as “Tian Chao Wan Shun 天朝萬順”.87 Based on Liu’s account, Yuewang Wei suggests that the character concerned should be read as “Sui 歲”.88 Naixiong Chen questions all the above interpretations with good reason, and that leaves the meaning and pronunciation of the character undecided. I suggest that there is another clue which should be considered.

resembles the Jurchen character

resembles the Jurchen character  , which is pronounced “Bai”, and hence sounds similarly to “Bao”.86 Fengzhu Liu provides another idea, that they should be read as “Tian Chao Wan Shun 天朝萬順”.87 Based on Liu’s account, Yuewang Wei suggests that the character concerned should be read as “Sui 歲”.88 Naixiong Chen questions all the above interpretations with good reason, and that leaves the meaning and pronunciation of the character undecided. I suggest that there is another clue which should be considered.

, which is pronounced “Bai”, and hence sounds similarly to “Bao”.86 Fengzhu Liu provides another idea, that they should be read as “Tian Chao Wan Shun 天朝萬順”.87 Based on Liu’s account, Yuewang Wei suggests that the character concerned should be read as “Sui 歲”.88 Naixiong Chen questions all the above interpretations with good reason, and that leaves the meaning and pronunciation of the character undecided. I suggest that there is another clue which should be considered.There are two coins identically inscribed with two characters and three groups of Yunwen 孕文 (pattern of the sun and the moon) coming onto the numismatic market (Figure 41), which are being studied by some scholars who are suggesting they be called “Tian Zheng Yuan Bao 天正元寶”.89 There was only one short period (1161–1162) during the Jin Dynasty given the title of the reign of “Tian Zheng 天正”. Corresponding to the shortness of the period, the coins of “Tian Zheng” are very rare—only two have been discovered so far. In 1161, Yilawogan 移刺窩幹, a Khitan leader, led an army against the Jin ruler (Jurchen nobles) and then seized the throne to set up the Tian Zheng reign, but it only lasted ten months. In 1162, Yilawogan was betrayed and killed and hence the period of Tian Zheng ended with him. The Jin rulers then resumed their reign until they were completely conquered by the Mongolian forces. When looking at the Tian Zheng coins, it is noteworthy that the two characters Tian and  (Zheng) are located in the same spots where the Tian and

(Zheng) are located in the same spots where the Tian and  are on the abovementioned coins of four Khitan characters, and the shape of

are on the abovementioned coins of four Khitan characters, and the shape of  (Zheng) is very close to that of

(Zheng) is very close to that of  (Bao), only it seems to be written in abstract and cursive script rather than Shoujin style. If that is the case, then at least we can reach an inference that the tradition of using

(Bao), only it seems to be written in abstract and cursive script rather than Shoujin style. If that is the case, then at least we can reach an inference that the tradition of using  and

and  on seals started around 1161, and was retained among the nobles thereafter, finally making its way to the mainstream tradition of Song Yuan Huaya during the Yuan Dynasty. Since the meaning of

on seals started around 1161, and was retained among the nobles thereafter, finally making its way to the mainstream tradition of Song Yuan Huaya during the Yuan Dynasty. Since the meaning of  , although lacking accurate interpretation, is closely related to auspicious connotations (Fu, Bao, Bai, or Zheng), it is not surprising to see them thriving in Song Yuan Huaya, since with private seals, the appeal to auspicious significance is the most important.

, although lacking accurate interpretation, is closely related to auspicious connotations (Fu, Bao, Bai, or Zheng), it is not surprising to see them thriving in Song Yuan Huaya, since with private seals, the appeal to auspicious significance is the most important.

(Zheng) are located in the same spots where the Tian and

(Zheng) are located in the same spots where the Tian and  are on the abovementioned coins of four Khitan characters, and the shape of

are on the abovementioned coins of four Khitan characters, and the shape of  (Zheng) is very close to that of

(Zheng) is very close to that of  (Bao), only it seems to be written in abstract and cursive script rather than Shoujin style. If that is the case, then at least we can reach an inference that the tradition of using

(Bao), only it seems to be written in abstract and cursive script rather than Shoujin style. If that is the case, then at least we can reach an inference that the tradition of using  and

and  on seals started around 1161, and was retained among the nobles thereafter, finally making its way to the mainstream tradition of Song Yuan Huaya during the Yuan Dynasty. Since the meaning of

on seals started around 1161, and was retained among the nobles thereafter, finally making its way to the mainstream tradition of Song Yuan Huaya during the Yuan Dynasty. Since the meaning of  , although lacking accurate interpretation, is closely related to auspicious connotations (Fu, Bao, Bai, or Zheng), it is not surprising to see them thriving in Song Yuan Huaya, since with private seals, the appeal to auspicious significance is the most important.

, although lacking accurate interpretation, is closely related to auspicious connotations (Fu, Bao, Bai, or Zheng), it is not surprising to see them thriving in Song Yuan Huaya, since with private seals, the appeal to auspicious significance is the most important.

Figure 41.

A Khitan coin inscribed with characters “Tian Zheng” (with highlighted). 1661–1662 CE. Sketched by author. Picture source: Yang (1991), p. 75.

As for another Jurchen character  , seen abundantly in Song Yuan Huaya, it is too early to decide on its meaning. However, according to its shape, it may have some relation to the character

, seen abundantly in Song Yuan Huaya, it is too early to decide on its meaning. However, according to its shape, it may have some relation to the character  . This character is pronounced “ta”, but its meaning remains unknown.90

. This character is pronounced “ta”, but its meaning remains unknown.90

, seen abundantly in Song Yuan Huaya, it is too early to decide on its meaning. However, according to its shape, it may have some relation to the character

, seen abundantly in Song Yuan Huaya, it is too early to decide on its meaning. However, according to its shape, it may have some relation to the character  . This character is pronounced “ta”, but its meaning remains unknown.90

. This character is pronounced “ta”, but its meaning remains unknown.90Compared to the other Khitan and Jurchen seals, including private seals and official seals with inscriptions of proverbs, phrases, or single words, it seems that only the abovementioned three characters were broadly preserved in Song Yuan Huaya and became popular in combination with other elements. Except for the last character  , the other two characters in question seem possibly parallel with traditional Chinese seal signs “Ji” and “Ya” as mentioned above. Can we hypothesize that when the peoples in the later Song and the Yuan Dynasties developed the various Song Yuan Huaya trends, they borrowed ethnic elements in their simplest and hence most popular forms, making the borrowing of the elements more akin to a fashion than to a demand for strong and clear sematic expression, such as an identity declaration or differentiation?

, the other two characters in question seem possibly parallel with traditional Chinese seal signs “Ji” and “Ya” as mentioned above. Can we hypothesize that when the peoples in the later Song and the Yuan Dynasties developed the various Song Yuan Huaya trends, they borrowed ethnic elements in their simplest and hence most popular forms, making the borrowing of the elements more akin to a fashion than to a demand for strong and clear sematic expression, such as an identity declaration or differentiation?

, the other two characters in question seem possibly parallel with traditional Chinese seal signs “Ji” and “Ya” as mentioned above. Can we hypothesize that when the peoples in the later Song and the Yuan Dynasties developed the various Song Yuan Huaya trends, they borrowed ethnic elements in their simplest and hence most popular forms, making the borrowing of the elements more akin to a fashion than to a demand for strong and clear sematic expression, such as an identity declaration or differentiation?