Abstract

The interpretation of early Buddha images with a crown has long been a source of debate. Many scholars have concluded that the iconography of the crown is intended to denote Śākyamuni as a cakravartin or universal Buddha. A few have suggested it represents a sambhogakāya Buddha in Mahāyāna Buddhism. This art historical and Buddhological study examines the visual record of early crowned Buddhas along the Silk Road, focusing on the iconographic signifiers of the crown, silk items, and ornaments, and interprets them within a broader framework of Buddhist theoretical principals and practice. Not only is this a visual analysis of iconography, it also considers contemporary Buddhist literary evidence that shows the development of the iconography and ideology of the crowned Buddha. As a result of this examination, I propose that the recurring iconographic evidence and the textual evidence underscore the intention to depict a form of sambhogakāya Buddha as an early esoteric meditational construct. Moreover, many Buddhas perform one of the two mudrās that are particular to the esoteric form of Vairocana Buddha. Therefore, the iconography also signifies the ideology of the archetypal Ādi Buddha as an esoteric conception.

Keywords:

crowned Buddha; Buddhism; Vajrayāna; sambhogakāya; Vairocana; cakravartin; Silk Road; Paṭola Śāhi 1. Introduction

The paradigm of the crowned Buddha figures found along the transcontinental travel system of the Silk Road has been a discourse in scholarship for many years. These images are often called bejeweled Buddhas because they not only feature a crown, they are also decorated with ornaments and jewels in contrast to the depiction of the unadorned Buddha in monastic robes. The most prevalent interpretation for this iconography is that the crown is used to denote a Buddha as a cakravartin or universal sovereign. Under this ideology, the historical Śākyamuni Buddha has been given new, transcendent powers within Mahāyāna Buddhism.1 In particular, several scholars suggest the iconography of the crowned Buddha with a cape (often called a chasuble) and jewels depicts Śākyamuni’s coronation or abhiṣeka (consecration) as a cakravartin in Tuṣita paradise, where Maitreya, the future Buddha, will reside until his eon or kalpa arrives (Rowland 1961; Snellgrove 1978; Klimburg-Salter 1989; Taddei 1989; Von Schroeder 2001). In a Mahāyāna Buddhist context, the crown typically represents the highest level of knowledge and attainment, especially due to the completion of the last or 10th stage or bhūmi on a bodhisattva path experienced by all bodhisattvas or Buddhas-to-be before their last rebirth.2 As such, the crown is a marker of Buddhahood. Klimburg-Salter (1989) stated that during the coronation, he is crowned and given royal regalia, which corresponds to the iconography of these images.3

Another ideology presented by previous scholars is that the iconography of the crowned Buddha relates to the pañcavārṣika ceremony (Rowland 1961; Klimburg-Salter 1989; Taddei 1989). The ceremony was documented by Buddhist pilgrims, such as Faxien and later by Xuan Zhang in various Buddhist kingdoms and sites, including Bamiyan, Kapisa, Khotan, and Kucha.4 For example, Xuan Zhang (629) described one ceremony that involved the king and all of his people as well as a procession of “highly adorned images of Buddha, decorated with precious substances and covered with silken stuffs” (Klimburg-Salter 1989; Walter 1997). During the ritual, the king gives his crown and cape to the adorned Buddha. It is at this point, according to Maurizio Taddei (1989), that the Buddha revealed himself as a universal sovereign or cakravartin. Moreover, Taddei proposed that an image of a jeweled Buddha was a gift during the ceremony. Since the ritual is closely tied to the sacred role of the king, it is often argued that only the images of the crowned Buddhas with accompanying donors can be interpreted as this particular ceremony. Using the Saṃghāṭa Sūtra (a text also found among the Gilgit Manuscripts), Rob Linrothe (2014) suggested that the cape as an expensive garment is meant to be a gift to an image of the Buddha, and is not necessarily tied to the ceremony or kingship. This is based on a section where Śākyamuni Buddha recalls one of his previous lives as a wealthy householder and the gifts he gave to Buddhas, including garments, ornaments, and cloaks.

On the other hand, some scholars have suggested that the crowned Buddha represents a sambhogakāya Buddha in Mahāyāna Buddhism (Mus 1928; Coomaraswamy 1928; Rowland 1961; Snellgrove 1978; Paul 1986). The sambhogakāya or enjoyment body form of a Buddha is a meditational construct that is part of the trikāya or three-body system, which will be discussed in depth later in this article. V. Krishan (1971) and Taddei (1989) disagreed with this notion, saying the iconography refers to the abhiṣeka. Moreover, Taddei said that in the Lotus Sutra, Śākyamuni only revealed his sambhogakāya form to a multitude of bodhisattvas, and therefore, since no bodhisattvas are depicted with the crowned Buddhas, the iconography does not fit.

This article focuses on the visual record of images specifically depicting crowned Buddhas, including sculptures and paintings, from some of the major cities along the Silk Road, including Bamiyan, Foundukistan, Haḍḍa, Gandhara, Swat, Kashmir, Tibet, Gilgit, and Baltistan or Bolōr (today known as Northern Pakistan). Using this visual record, I first demonstrate that there are recurring core iconographic elements on the crowned Buddhas with underlying symbolism. These iconographic parallels consist of the cape, the crown, and the symbol of a crescent moon with a sun. Next, using more recent publications on Buddhist iconography and Vajrayāna Buddhism (Huntington and Bangdel 2003; Chandrasekhar 2004; Twist 2011), I show that an examination of these images with their coded visual language within a larger Buddhist framework underscores the intention to depict a form of a sambhogakāya Buddha or enjoyment body nature of a meditational construct that relates to early Vajrayāna Buddhism. In addition, I propose that there are also iconographic signifiers that are relevant to an esoteric form of Vairocana Buddha as an archetypal Ādi or Primordial Buddha. Thus, through the new contextualization of these crowned Buddhas along the Silk Road, a form of religious transmission or early Vajrāyana ideology and practice is revealed.

2. Recurring Core Iconographic Elements

2.1. Cape

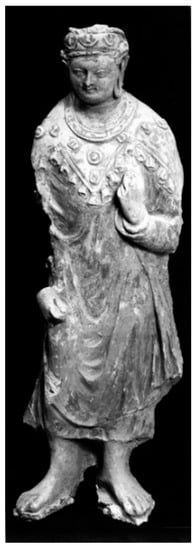

The distinct cape found on the Buddha images is depicted with a triangle corner draped over each shoulder, one on the chest, and one on the back, making a four pointed cape. This can be seen on a seventh to eighth c. crowned Buddha from Kashmir published in Buddhist Sculptures in Tibet (Von Schroeder 2001), pl. 16A. These capes are typically decorated with jewels and/or tassels. Although Klimburg-Salter (1989) called it a three-pointed cape, Taddei (1989) and P. Banerjee (1992) among other scholars generally agreed that in a frontal image with such a cape, the fourth corner on the back is likely to be understood as another point. Examples of this cape can be found on a sculpture of Buddha from Gandhara (second to fourth c.) and on a Buddha painted in niche I at Bamiyan (seventh c.) (Figure 1 and Figure 2).5 Similarly, a fragment of a Buddha figure from Haḍḍa wears a cape decorated with jewels, including a large crescent moon symbol (Figure 3). A similar cape is found on a Buddha from Niche D at a monastery in Fondukistan (seventh c.); he is wearing a jeweled four-pointed cape with tassels (Figure 4).6 In addition, there are several sculptures of Buddhas from Gilgit or Baltistan (Little or Greater Bolōr) that all feature the same distinct elaborate cape (Figure 5 and Figure 6).7 Through inscriptions, these are known to have been commissioned by the Paṭola Śāhi dynasty that ruled in that region (Von Hinüber 2004; Twist 2011). Since the geographical location of Gilgit is more commonly known in scholarship, I will use that term for this article.

Figure 1.

Buddha wearing a crown and jeweled cape, second to fourth c. Gandhara. Stucco. H 51 cm. Walmore Collection, London. Photograph courtesy of John C. Huntington.

Figure 2.

Buddha wearing a crown and cape. Painting in niche “I” at Bamiyan, seventh c. Photograph courtesy of John C. Huntington.

Figure 3.

Buddha figure wearing a cape and jewels. Haḍḍa. Stucco fragment. Musée Guimet, Paris (MG 20996). Photograph from Taddei (1989), courtesy of the Musée Guimet.

Figure 4.

Buddha wearing a jeweled cape. Clay fragment from niche D, seventh c. Fondukistan. Musée Guimet, Paris. Photograph from Twist, courtesy of the Musée Guimet.

Figure 5.

Buddha wearing a crown and cape with crescent moon and sun symbols performing the dharmacakra-pravartana mudrā. Commissioned by King Nandivikramadityanandi, April or September, 715 C.E. Gilgit. Brass with copper and silver inlay. 36.8 cm H. Pritzker Collection. https://himalayanbuddhistart.files.wordpress.com/2015/08/8th-c-715-gilgit-shakyamuni-brasssil-c-inlay-donorsattendantsdancer-private-col.jpg.

Figure 6.

Buddha wearing a crown and cape with crescent moon and sun symbols performing the dharmacakra-pravartana mudrā. Commissioned by Saṃkaraseṇa and the princess Devasrī, April 20, 714 C.E. Gilgit. Brass with inlays of copper, silver, and zinc. 12 ¼ in. H. (31.1. cm). Asia Society, New York: Mr.and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3rd Collection (1979.44). https://www.buddhistdoor.net/news/collecting-paradise-buddhist-art-of-kashmir-and-its-legacies.

2.2. Crown

Crowns are utilized in a plethora of religions for the representation of deities as an emblem of their supremacy. Thus, it is no surprise to find images of crowned Buddhas both with and without the jeweled cape from the Silk Road. Two exemplars of crowned Buddhas without the cape are from Kashmir (eighth to ninth c.) (Figure 7 and Figure 8). Numerous crowned Buddhas also without capes come from Gilgit, some with inscriptions that indicate they are from the Paṭola Śāhi dynasty (Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11 and Figure 12) (Von Schroeder 2001; Von Hinüber 2004; Twist 2011).8 It is important to note that these bejeweled crowns, some with a string of pearls, are consistently depicted with flowing silk ribbons attached to sides along with two open lotuses as jewels on each side of the crowns.9 This iconography is consistent among the Silk Road crowned Buddhas, and will be discussed later.

Figure 7.

Buddha wearing a crown. Eighth c. Parihasapura, Kashmir. Stone. H 128.2 cm. Sri Pratap Singh Museum, Srinagar, Kashmir. Photograph courtesy of John C. Huntington.

Figure 8.

Buddha wearing a crown. Eighth to ninth c. Kashmir. Brass. H 35 cm. Po to la Collection: Li ma lha khang; inventory no. 1392. Red Palace, Lhasa, Tibet. https://www.himalayanart.org/items/9086. Copyright@ 2018 Himalayan Art Resources Inc.

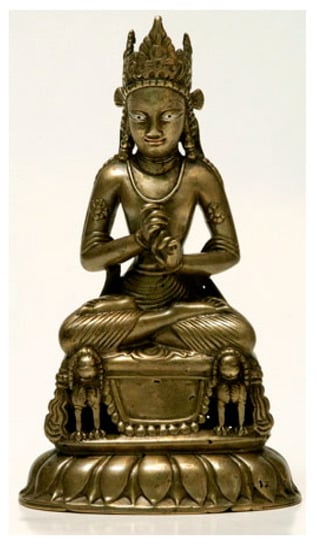

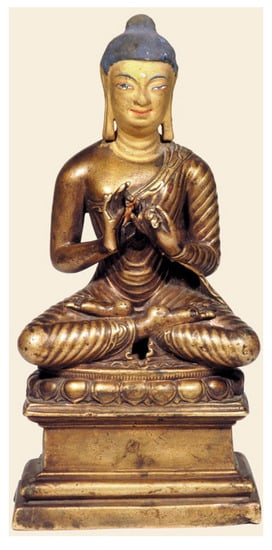

Figure 9.

Buddha wearing a crown. Commissioned by King Nandivikramadityanandi, April 714 C.E. Gilgit. Brass–copper alloy with copper and silver inlays. 11 ½”H × 6”W × 4”D. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond. Arthur and Margaret Glasgow Fund (86.120). https://alaintruong2014.files.wordpress.com/2015/01/1919.jpg.

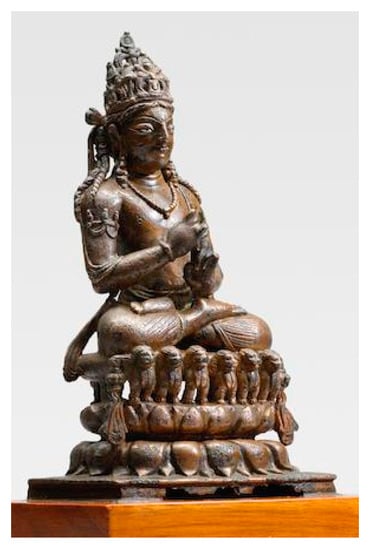

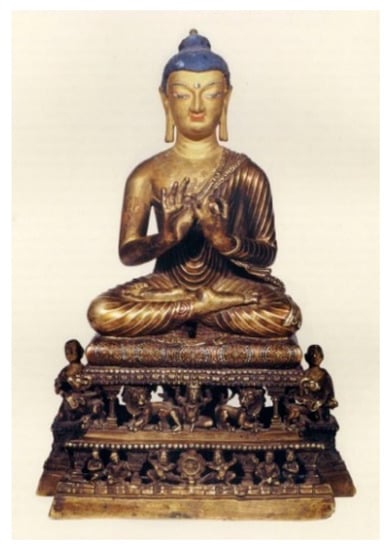

Figure 10.

Buddha wearing a crown performing the dharmacakra-pravartana mudra. Commissioned by Śrī Surabhī and the monk Hariṣayaśa, 678/679 C.E. Gilgit. Brass with copper and silver inlay. 22cm H. Tibet Museum, Alain Bordier Foundation, Gruyeres/Suisse (No. 3). (item #3 on website page) http://tibetmuseum.info/e/Kashmir.html.

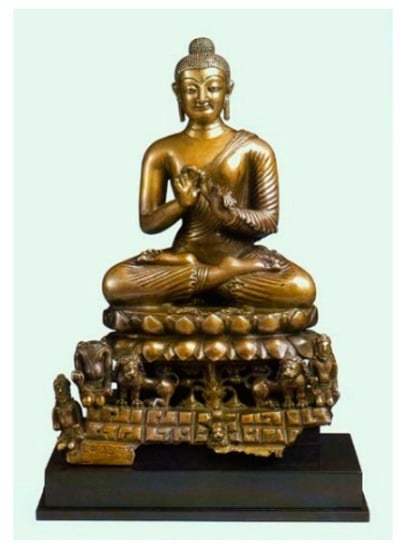

Figure 11.

Buddha wearing a crown performing the dharmacakra-pravartana mudrā. Approx. 675–722 C.E. Gilgit or Kashmir. Brass with copper and silver alloy. 31.1 cm H. Jo khang/gTsug lag khang Collection: inventory no. 261[A]. Lhasa, Tibet. https://www.himalayanart.org/items/57104. Copyright@ 2018 Himalayan Art Resources Inc.

Figure 12.

Crowned Buddha, seventh century. Side one of a three-sided stone sculpture from Gilgit. Photograph courtesy of John C. Huntington.

More importantly, several images of crowned Buddhas feature both iconographic motifs of the crown and the elaborate cape. Several examples of crowned Buddhas with capes come from Kashmir (seventh to eighth and ninth c.) (Figure 13, Figure 14, Figure 15 and Figure 16). Two Buddhas believed to be from Gilgit or possibly Kashmir also feature a cape and a crown (Figure 17 and Figure 18).10 An example can even be found on a rock carving from Chilas clearly depicting a crowned Buddha figure wearing the cape (dated prior to 630) (Figure 19). In addition, several examples mentioned previously regarding the elaborate cape from Bamiyan and Gilgit also feature a crown (Figure 2, Figure 5 and Figure 6).

Figure 13.

Buddha wearing a crown and jeweled cape with a crescent moon and sun symbols, eighth c. Parihasapura, Kashmir. Stone. Sri Pratap Singh Museum, Srinagar, Kashmir. Photograph courtesy of John C. Huntington.

Figure 14.

Buddha wearing a crown and a jeweled cape, seventh to eighth c.Kashmir. Brass with silver inlay. H 16 cm. Jo khang/gTsug lag khang Collection; inventory no. 644, Lhasa, Tibet. https://www.himalayanart.org/items/57102. Copyright@ 2018 Himalayan Art Resources Inc.

Figure 15.

Buddha wearing a crown and jeweled cape, ninth c. Kashmir or Northern India. Bronze. Alan Robert Naftalis Collection. https://www.himalayanart.org/items/86315/images/primary#-1710,-2380,3009,-1. Copyright@ 2018 Himalayan Art Resources Inc.

Figure 16.

Buddha wearing a crown and a cape with crescent moon and sun symbols, eighth to ninth c. Kashmir. Brass. H 52 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Ben Heller (1970.297). https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/39345.

Figure 17.

Buddha wearing a crown and cape performing the dharmacakra-pravartana mudrā, eighth c. Gilgit or Kashmir. Gilt copper alloy, private collection. https://himalayanbuddhistart.files.wordpress.com/2015/08/8th-c-gilgit-shakyamuni-labellted-maitreya-gilt-bronze-photo-hughes-dubois.jpeg.

Figure 18.

Buddha wearing a crown and cape with crescent moon and sun symbols. Approx. 675–722 C.E. Kashmir or Gilgit. Brass. 7 ¼” H. Pan-Asian Collection https://www.himalayanart.org/items/61436. Copyright@ 2018 Himalayan Art Resources Inc.

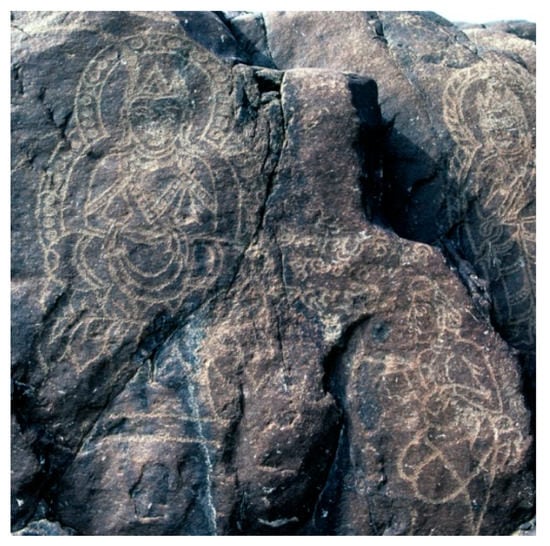

Figure 19.

Crowned Buddha with a cape, prior to 630 C.E. Rock carving from Chilas. Commissioned by Siṃhota. Photograph courtesy of John C. Huntington.

2.3. Crescent Moon with a Sun

The symbols of the crescent moon with a rosette-like sun are also recurring iconographic elements on crowned Buddha figures from the Silk Road. Sometimes, these symbols are depicted within the crown and/or on the shoulders of the Buddha; hence, they can be considered a form of jeweled ornament. Several crowned Buddha figures from Kashmir that were mentioned earlier feature crowns that carry the motifs of the crescent moon with a rosette-like sun inside of it (see Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 13 and Figure 16). Note that two of the four Buddhas also feature the elaborate cape, and that Figure 16 also bears the same symbolic motif on the shoulders.

Similar lunar and solar symbolism appears on quite a few of the crowns on the Paṭola Śāhi Buddhas. More importantly, a crescent moon with a sun inside is found on all of the shoulders of their crowned Buddhas wearing capes (see Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 19). Interestingly, the symbols also appear on the top of the stūpas that flank the Buddha in one sculpture (Figure 6). These are not the only examples of this iconography along the Silk Road. The crescent moon with a solar disc is also depicted on several stūpas found in rock carvings in Chilas and one from Thalpan.

3. Crowned Buddha as Cakravartin

As mentioned previously, one iconographic interpretation of a Buddha with a crown is that he is to be understood as a cakravartin, and as such, the recurring parallels of the above motifs can certainly support the meaning of a universal sovereign. For example, some scholars suggest that the elaborate cape was adopted from royal attire, perhaps from Gandhara, Central Asia, or even the Himalayas, in order to denote a cakravartin Buddha (Taddei 1989; Klimburg-Salter 1989; Von Schroeder 2001; Paul 1986).11 An example of a royal donor figure wearing a cape can be seen on two Gandharan sculptures. One from the Lahore Museum in India depicts Pāῆcika with a donor that wears a cape (see S. Huntington, The Art of Ancient India, Figure 8.25). Another sculpture from a private collection is believed to be a donor wearing a cape holding his offering (see Isao Kurita, The World of the Buddha: Ancient Buddhist Art-Gandhara, vol. 2, Figure 523) However, it is important to note that the donor capes are made of what appears to be animal skin, and they are not decorated with jewels or a fringe of tassels. Therefore, they are very different than the capes depicted on the crowned Buddhas. Moreover, several Paṭola Śāhi kings are depicted in their sculptures, and none of them wear a cape. Linrothe (2014, pl. 1.30) pointed out a sculpture that is possibly from Kashmir published by John Siudmak (2013, pl. 189) that features Surya and Danda in a tasseled cape, suggesting this indicates it was not strictly used in Buddhist iconography. Rather, he stated that it was used to show power on images from Greater Kashmir. However, it is significant to note that these capes are not decorated with jewels. Regardless, it is certainly possible that the cape may have been a symbol borrowed from kings to convey the notion of the attainment of Buddhahood.

The crown is historically an ancient symbol that is worn to mark royalty in the earthly realm, and therefore, it became an emblem to denote power and authority. Since the crown is a signifier of kingship, it is no surprise to see it used in Buddhist images to convey the ideology of a universal sovereign or cakravartin Buddha. As mentioned previously, the crown represents the highest level of knowledge and attainment of Buddhahood in the completion of the last stage or bhūmi (his abhiṣeka); hence, he could be recognized as a universal Buddha via the crown. The flowing ribbons and lotuses on the crown further signify the royal imagery of a universal sovereign.

The lunar and solar symbols are also effigies of kingship, and therefore, their royal connotations serve as iconographic symbols on a crowned Buddha to denote his status as a cakravartin.12 A Buddha in the aspect of a universal sovereign is depicted wearing a crown and jewelry to symbolize his great power and authority. John Huntington explained that the crown and jewelry “draw a visual analogy between the attainment of Buddhahood and coronation as a king” (Huntington and Huntington 1990). Therefore, the crescent moon with the rosette-like sun on a Buddha’s shoulders, together with a crown, signifies his highest status.

These iconographic symbols are also significant emblems in Buddhist iconography. The sun and the moon are often used as metaphors or descriptors for Buddhas and Buddhist teachings. For example, the Lotus Sūtra says, “As the light of the sun and moon can banish all obscurity and gloom, so this person [Buddha] as he passes through the world can wipe out the darkness of living beings” (Watson 1993). The sun and the moon dispel darkness and aid in disseminating light just like the light of knowledge taught by the Buddhist dharma. In addition, in the Bhaisajyagura Sūtra found in Gilgit, it says that the sun and moon have great power, just like the Buddha and the dharma (Schopen 1976). Moreover, in visual imagery, a moon or sun disk on a lotus represents the perfect wisdom attained by all Buddhas through the dharma.

Thus, it is likely that these recurring key motifs were deliberately chosen as iconography explicitly used for crowned Buddhas to set them apart and convey specific meanings. Since they were all emblems used by royalty, this iconography of kingship was given to a supreme Buddha figure to imbue him with a higher status and mark him as a cakravartin. Therefore, it is clear that these core iconographic motifs can work together on one level to denote the notion of a transcendent Buddha and universal sovereign, signifying the crowned Buddha’s attainment of the highest truth and authority of Buddhahood. Similar to other scholars, Linrothe (2014) suggested that it is safest to conclude that the crown and cape are merely associated with kingship and royal rituals.13

4. Crowned Buddha as Sambhogakāya

However, Buddhist iconography is often multivalent, and as such, several of these symbols hold underlying esoteric ideologies as well. I propose in a deeper contextualization of these crowned Buddhas that the iconography reveals an underlying pattern of the primary benchmarks that are needed to portray an early meditational construct of a sambhogakāya Buddha.

The sambhogakāya or enjoyment body form of a Buddha is the meditational form that serves as a way to experience or visualize the highest or non-representational form body of a Buddha called the dharmakāya. It is part of the trikāya or three-body system that is used to understand the nature of numerous Buddhas, and is a fundamental concept in both Mahāyāna and Vajrayāna Buddhism. The three natures of a Buddha can be experienced as nirmāṇakāya (the transformation and physical body), sambhogakāya (the enjoyment body), and dharmakāya, which is inconceivable, so it has no representation.14 All three bodies were considered different aspects of the same reality. Paul Griffiths (1994) explained that dharmakāya is considered to be identical to dharmadhātu or the dharma realm. Minoru Kiyota (1982) explained that sambhogakāya is indestructible and eternal, similar to dharmakāya, but it is also capable of communicating with sentient beings like nirmāṇakāya. The enjoyment body transcends the nirmāṇakāya Buddha as a symbol for living beings to understand dharmakāya, and as such, sambhogakāya concretizes the indefinable (Xing 2005; Williams 1989).

In the meditational realm of skilled adepts, the sambhogakāya enables beings to perfect their skills and attain the reification of dharmakāya and Buddhahood (Griffiths 1994). Thus, the intrinsic nature of the Buddha field and sambhogakāya is manifested in the mind. Chaya Chandrasekhar (2004) explained that enjoyment bodies “are sole meditational constructs, manifested in the minds of skilled practitioners … In other words, through envisioning a Buddha field and its inhabitants, an adept practitioner, while physically bound to earthly existence, conceptually experiences the glory of the sambhogakāya and transcends ordinary space and time.” In Vajrayāna Buddhism, in particular, through using transformative meditation practices, the adept even becomes a sambhogakāya Buddha in the highest meditational realm of Akaniṣṭha on Mt. Meru. In essence, a sambhogakāya Buddha is a meditational construct that is manifest in the minds of advanced practitioners, especially in esoteric Buddhism.

4.1. The Representation of a Sambhogakāya Buddha

When a Buddha (such as the historical Śākyamuni) is portrayed or visualized in his human emanation body or nirmāṇakāya, he is depicted as an unadorned ascetic wearing monastic garments. Often, his mudrā refers to a particular life event highlighting his nirmāṇakāya nature. Chandrasekhar (2004) explained that the nirmāṇakāya Buddha’s mudrās relate to the earthly activities completed in order to bring living beings to enlightenment.

According to Sonam Kazi’s translation (Kazi 1989–1993) of Kün-zang Lama’s instructions, the visual representation of a tantric, meditational, or sambhogakāya Buddha is presented with key identifying traits. The list of 13 specific characteristics for the fully developed iconography of a meditational Buddha is listed below, and is divided into Silk Items and Jeweled Ornaments (Huntington 2003a):

Five Silk Items:

- (1)

- Ribbons (ties on the crown)

- (2)

- Upper garment (almost never depicted)

- (3)

- Silk scarf (billowing behind)

- (4)

- Sash at the waist (often hidden)

- (5)

- Lower garment (dhoti)

Eight Jeweled Ornaments:

- (1)

- Crown

- (2)

- Right and left earrings (count as one)

- (3)

- Necklace

- (4)

- Two armlets (count as one)

- (5)

- Long and short necklaces (count as one)

- (6)

- Two bracelets (count as one)

- (7)

- Finger rings (count as one)

- (8)

- Two anklets (count as one)

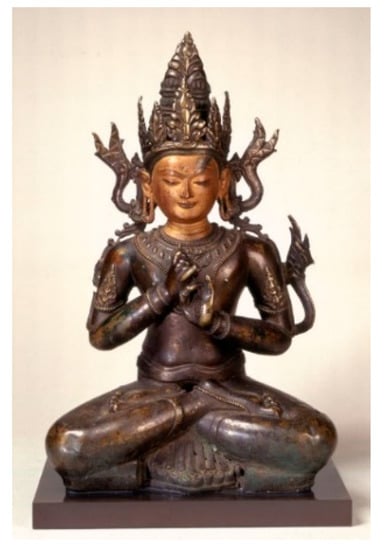

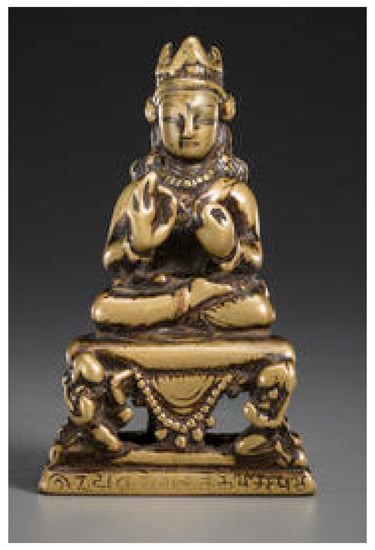

The sculpture of a 14th century Vairocana Buddha from Western Tibet displays this fully developed codified iconography of a sambhogakāya (see Figure 20).

Figure 20.

Vairocana Buddha. 14th century, Western Tibet https://himalayanbuddhistart.files.wordpress.com/2015/09/12th-c-tibet-ct-vairocana-c-a-cold-g-61-cm-albuquerque.jpg.

In Vajrayāna or esoteric Buddhism, the five-pointed crown especially represents the five transcendent insights (jñāna) that are needed to attain all knowledge and ensuing Buddhahood. These five qualities are personified in Buddhist iconography by the pañca (five) jina (victorious) Buddhas, who are often depicted in a mandala.15 They are also called cosmic or transcendent Buddhas (or sometimes dhyana Buddhas), and are generally shown wearing the silk items and jeweled ornaments of a sambhogakāya. Vairocana Buddha is shown in the center of their mandala as the most important, since he personifies the transcendent insight of the full understanding of truth and reality, or the totality of all five insights.

Moreover, when a crown on a Buddha has five points or triangular sections or five jewels around the diadem, it especially represents the five insights of the pañca jina Buddhas, and is therefore called a pañca jina crown (Figure 21). The crown can also depict each of the five Buddhas as well. The pañca jina crown is an esoteric symbol of the five transcendent qualities and five Buddhas that constitute the totality of enlightenment or Buddhahood (Huntington and Huntington 1990; Livingston 2003; Huntington and Bangdel 2003).16 Thus, both the pañca jina Buddhas and the crown are a paradigm for Vajrayāna symbology, practice, and attainment.

Figure 21.

Paῆca jina Crown, Tibet. https://www.himalayanart.org/items/59558/images/primary#-55,-1300,2524,0. Copyright@ 2018 Himalayan Art Resources Inc.

Considering the representation of a sambhogakāya Buddha, it is evident that many of the crowned Buddhas in the visual record from the Silk Road feature some of the primary benchmarks from Kün-zang Lama’s list that are especially needed to distinguish them as early forms of esoteric meditational constructs—in particular, the crown, the silk ribbons, and the jeweled ornaments. While not all of the crowns found on the Buddha images are the five-pointed pañca jina crowns, some of them appear to have five leaves. Regardless, the symbology of the crown creates a clear distinction between an unadorned Buddha and a crowned one wearing jeweled ornaments.

It is possible that the elaborate cape was an early form of the upper garment listed under the Silk Items. In a Buddhist practitioner’s context, each of the four corners of the cape represent the four corners of Mt. Meru (or the Buddhist cosmos), and the four quarters of the worldly realm of knowledge (Bangdel and Huntington 2003).17 This is even evident today in Vajrayāna Buddhism, where this same type of cape is worn by Vajrasattva priests in Nepal when they do meditations, visualizing themselves as being on Mt. Meru at the center of a mandala (Huntington and Bangdel 2003). The cape aids in the transformation of space and identity in Vajrayāna practice for a yogin priest, particularly taking place in the highest meditational realm on Mt. Meru: Akaniṣṭha.

Moreover, the moon and sun symbols appearing in the crown and on the shoulders could be considered jeweled ornaments from the list. As Gérard Fussman (1994) pointed out, the sun and moon symbols, especially on a crowned, tantric Buddha’s shoulders, signify his attainment of the highest truth and Buddhahood, similar to the iconography of the crown. Both the Buddha and his teachings emanate light and truth; similar to the heavenly symbols, they reflect his great power and sovereignty.

In a further contextualization of the Buddhist iconography, there is another level of interpretation for the symbols. The emblems are found on the shoulders of many crowned Buddhas wearing the elaborate cape, which as mentioned, symbolizes Mt. Meru. Hence, it is also possible that in Vajrayāna mediations, the sun and moon symbols represent the sun and moon that are visualized to circle around Mt. Meru, aiding in the transformation of space. Therefore, the effigies are most likely another iconographic element that is chosen to reinforce the notion of the highest realm of attainment in Akaniṣṭha on Mt. Meru. They are also symbols in yogic meditation where the sun and moon motif represent the top chakras (Huntington and Bangdel 2003). Moreover, in Vajrayāna Buddhism, the emblems of the sun and moon can also symbolize the male and female principles, and are still used to represent their union in esoteric methodology (Dasgupta 1974; Huntington and Bangdel 2003; Twist 2011).18 Thus, the visual evidence indicates that the hallmark symbols that consistently appear were possibly chosen and understood at a multivalent level to convey the iconography of an early form of esoteric sambhogakāya Buddha.

4.2. Textual Evidence: Transition from Cakravartin to Sambhogakāya

This raises the question: “What contemporary Buddhist literary evidence exists that specifically describes the same iconography of a sambhogakāya?” Consequently, I examined various Buddhist texts, such as the Mahāvastu, the Avatamsaka Sūtra, the Mañjusrīmūlakalpa, the Guhyasamāja Tantra, and the Mahāvairocana abhisaṃbodhi Tantra, looking for descriptions of crowned Buddhas and the sambhogakāya nature. The dates of the texts provide a general understanding of the religious principles and practices that were current at the time of this visual record. Although this article cannot discuss all of the texts in detail, the premise is that there is a clear development in the texts illustrating the iconographical conception of a crowned Buddha, which transitions from a cakravartin, and changes to then portray a sambhogakāya aspect within Vajrayāna theoretical practices. This transition includes images of Vairocana Buddha as the archetypal sambhogakāya.

4.3. Mahāvastu

The Mahāvastu, an early Mahāyāna Buddhist text, was compiled over a long period of time, so it is generally dated from the first to the fourth c. (Jones 1973–1978). It is a collection of history and legends regarding Śākyamuni and other Buddhas. It is an example where magic powers and superhuman qualities are attributed to Śākyamuni in the emanation body. Adjectives such as “transcendent”, the “king of dharma”, and “splendid in majesty” are used to describe Śākyamuni (Jones 1973–1978). Although there are references to Śākyamuni as a king, he is not directly called a universal king or cakravartin, nor is he described as wearing a crown. The term “universal king” is used throughout the text, but it is used for the 10th stage bodhisattvas in their last rebirth as a cakravartin king, which of course relates to Śākyamuni (Jones 1973–1978). This is the text that is most commonly used to refer to the abhiṣeka ceremony or coronation associated with the iconography of a royal crown on images of Śākyamuni. Hence, in the text, the ascetic figure of Śākyamuni developed into a transcendent Buddha endowed with great powers.19 The date of the text is too early for the established trikāya system, and the sambhogakāya body theory is not mentioned or implied in the Mahāvastu text.

4.4. Avatamsaka Sūtra (Flower Garland Sūtra)

The Avatamsaka Sūtra was begun as early as the second century, with a comprehensive rendition existing by the early fifth century (Cleary 1993). It is a Mahāyāna text that is primarily about Vairocana (Intense Light) and spiritual experience. In addition, it is considered the precursor of later Tantras that centered on Mahāvairocana (Greatly Intense Light). Moreover, Shashi Bhushan Dasgupta (1974) said that the dharmakāya’s cosmological and ontological meaning in this sūtra lead to the development of the tantric concept of the primordial or Ādi Buddha.

In the text, Śakyamuni, as a cakravartin, is no longer the primary Buddha. The new theory of sambhogakāya is presented as a means to differentiate between the emanation body and the enjoyment body, so Vairocana is described as the universal Buddha. Therefore, it has a clear description of the dharmakāya as Vairocana who resides in Akaniṣṭha (the realm of the sambhogakāya beings), where he is the entirety of all of the Buddha realms and teachings (Huntington and Chandrasekhar 2000). It states that the universe or dharmadhātu realm is the Buddha, and the essence of Vairocana.20 Therefore, when Vairocana is visualized or depicted, it is generally understood that his sambhogakāya nature personifies dharmakāya.

To indicate Vairocana’s status as a universal Buddha and early sambhogakāya form in the sūtra, he is described as an intensely luminescent light, transcendent as the sun, pervading the whole universe. Vairocana is also described as purified by jewels and arrayed with adornments, or with marks of greatness, so that each limb is adorned with multiple jewels (Cleary 1993). The sūtra also contains the “Tenth Stage of Enlightenment”, which is the stage of coronation or anointment where receiving a crown represents the attainment of a Buddha as a symbol of all knowledge, including Vairocana.

In this sūtra, Śākyamuni is simultaneously present in several places in different forms, so at this point, it is important to discuss the hypostasis or conflation of Buddhas that will be seen in later iconography. In the text, while Śākyamuni is sitting under the bodhi tree, he also ascends to the peak of Mt. Meru in Akaniṣṭha to preach to enlightened beings. In other words, Śākyamuni is Vairocana, and they are just two different manifestations in two places. This happens in other Buddha fields (or Pure Lands) as well. The conflation of two seemingly different Buddhas indicates a conscious association of the two; therefore, the identity of a Buddha can be layered with the identity of sambhogakāya Vairocana. In addition, using the Avatamsaka Sūtra and its 10th stage coronation to explain the iconography of a crowned Buddha, some scholars argue about when and where Śākyamuni can appear as a crowned Buddha. As mentioned earlier, it is thought that crowned Buddhas represent the abhiṣeka Buddhas in Tuṣita, and that bodhisattvas should be present as other figures in the composition. Yet in this text, it is clear that he is conflated with other Buddhas in other paradises, so the singular interpretation of the crown as only related to the abhiṣeka ceremony does not hold up.

Hence, by the time of this sūtra, the royal motif of a crown and the solar symbolism is clearly used as a signifier not only for a cakravartin, but also for a sambhogakāya Buddha. It is obvious that the text is no longer referring to an all-powerful or transcendent Śākyamuni Buddha, but rather, a cosmic principal of the universe: Vairocana, who is a dharmakāya Buddha.

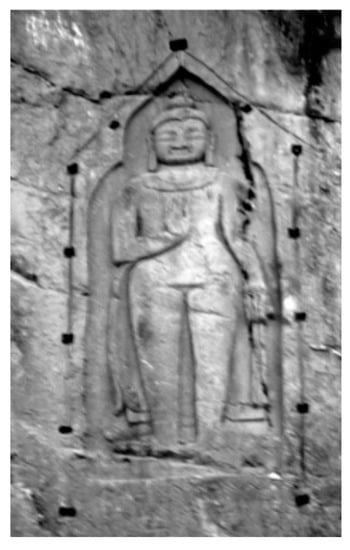

There are several extant images that likely represent Vairocana in his Mahāyāna sambhogakāya form that relate to this text. The colossal Buddha carved at Longmen in Honan, China commissioned by the Empress Wu in 672–675 is identified as Vairocana. This representation of a giant Buddha is based on the Avatamsaka Sūtra, which was popular in China at that time. His transcendent light that emanates and pervades all things is symbolized through his flaming halo and mandorla. Moreover, the large size of the sculpture conveys the notion in the sūtra that he has a great cosmic body as a Universal Buddha. Both the eighth c. colossal Vairocana Buddha (Birushana) at Tōdai-ji in Japan and the eighth c. Vairocana Buddha at Tōshōdai-ji (with 1000 little Buddhas in his halo) were likely based on the same premise and sūtra. Although missing the solar symbolism, perhaps the colossal Buddha at Kargah, near Gilgit, is meant to represent Vairocana as the great Universal Buddha as well (Figure 22).

Figure 22.

Colossal Buddha, seventh to eighth century. Carved into cliffs at Kargah near Gilgit. https://explorebeautyofpakistan.com/gilgit-baltistan/gilgit-region/kargha-budhha/.

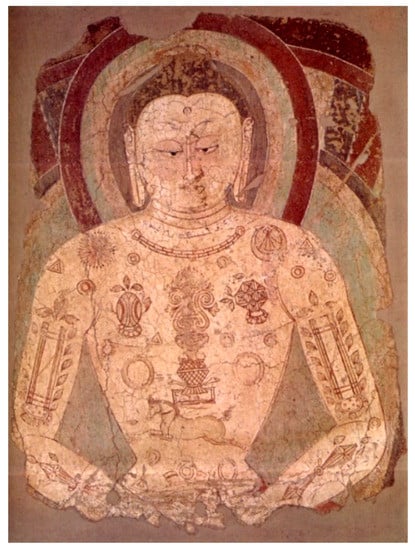

Vairocana’s early sambhogakāya aspect was also depicted through other forms of representation. For example, the cave painting at Balawaste in Central Asia (seventh to eighth c.) depicts the concept of the universal and cosmic Vairocana by painting ornaments and symbols on the body of the Buddha (Figure 23). Vairocana even has a solar symbol on his right shoulder and a crescent moon with a rosette on his left shoulder. Banerjee (1992) suggested that he held a crown in his hands that is no longer present. Other images that are similar include a Vairocana Buddha painted on a banner from Dunhuang which is now in the British Museum, and others from Farhad-Beg, Kyzyl, Karashar, and China, some dated as early as the fifth to sixth c. (Howard 1986). Thus, the textual evidence of the Flower Garland Sūtra indicates an understanding of the sambhogakāya form in Mahāyāna Buddhism, but visually, the iconography of correlating images is still being formulated. Although the iconography successfully conveys a cosmic and universal form with solar symbolism, the extant Buddhas do not yet feature crowns.

Figure 23.

Vairocana with crescent moon and sun symbols. Painting from Balawaste, Central Asia, eighth c. National Museum, New Delhi, Stein Collection of Central Asian Antiquities. Photograph courtesy of John C. Huntington. See also http://museumsofindia.gov.in/repository/record/nat_del-99-1-46-4635.

4.5. Mañjusrīmūlakalpa

The Mañjusrīmūlakalpa (hereafter called the Mmk) is another Buddhist text that was compiled over time and contains parts that might have existed independently at one time (Wallis 1999). It is suggested that Mmk 4 is the oldest, perhaps dating between the second and fourth century, while the remaining chapters are dated somewhere between the fifth and seventh centuries.21 However, Glenn Robert Wallis (1999) pointed out that it is clear that the Mmk documents a prevalent form of Buddhism practiced by the early eighth century. This text is important not only because it introduces many new Buddhist deities, but also because they are to be worshiped inside mandalas (sacred diagrams) through various rituals using mantras (sacred syllables or words) and mudrās (sacred hand gestures), which are all associated with Vajrayāna Buddhist practice.22

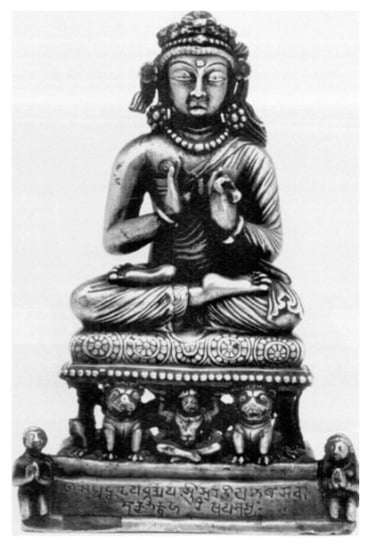

In the Mmk, the iconography is clearly set forth where sambhogakāya Buddhas are described as crowned and adorned with jewels and garments, including Mañjusrī and Ratnaketu (also known as the jina Buddha Akṣobhya). Interestingly, there is a crowned Buddha figure that is often identified as Mañjusrī (714 CE) from the Paṭola Śāhi dynasty in Gilgit that has these primary visual indicators to create a sambhogakāya Buddha with the crown and jewels and silk scarfs (Figure 9).

Some scholars, such as Klimburg-Salter (1989), have attempted to use the explanation for an image of a crowned Buddha in the Mmk mandalas as a direct correlation to a coronation or abhiṣeka during the 10th stage. Klimburg-Salter stated that transcendent Śākyamuni is dressed as a king in the center of the mandala; however, it is Ratnakatu who is named in the text as being in the mandala. It is rightly so in Vajrayāna Buddhism that the abhiṣeka takes place in the mandala for the initiate, and there, the initiate identifies with the crowned Buddha. However, in theoretical application, it is not a nirmāṇakāya Buddha that one visualizes for identity transfer, but rather a sambhogakāya crowned Buddha. Therefore, the crowned Buddha in a mandala is best explained in the Mmk as the sambhogakāya nature manifesting the body of dharma. Thus, in the Mmk, there is a standard formula developed for the iconography of an enjoyment body Buddha, particularly with the crown, garments, and jewels that are seen in contemporary images. It is a means of visualization and representation for the meditational construct of a sambhogakāya Buddha, not nirmāṇakāya Śākyamuni.

4.6. Guhyasamāja Tantra: (Secret Assembly Tantra)

The Guhyasamāja Tantra is dated by some to the third to fourth century or by others to the sixth to seventh century, with its explanatory Tantras written in the eighth to 12th centuries (Cunningham 2003).23 It is more systematic than the Mmk with a clear classification of the Vajrayāna Buddhist pantheon worshipped through mandalas, mantras, invocations, and mudrās. It includes the esoteric form of Mañjusrī, as Guhyasamāja-Mañjuvajra, and the esoteric pañca jina Buddhas with their prajῆās or female counterparts (Cunningham 2003). The Buddhas are described as wearing the fully codified iconography consisting of the five silk items and the eight jeweled ornaments, particularly the crown, in order to manifest their esoteric sambhogakāya nature.24 Moreover, Vairocana is referenced as becoming a supreme Buddha. As quoted by David Snellgrove (1959), “At that moment, (the yogin) becomes equal in radiance to Vairocana, (he becomes) Vajrasattva, the Great King, a Buddha, comprehending the vara of the threefold body.”

The pañca jina Buddhas in the sūtra are also embodiments of the dharmakāya, and as such, they play a fundamental role in the conception of sambhogakāya (Huntington 2003b).25 Iconographically, they appear in sambhogakāya form and are most often depicted with the characteristic enjoyment body traits, in particular, the pañca jina crown mentioned earlier. Two sculptures from Kashmir (seventh to eighth c.) represent the early iconography for the esoteric group of pañca jina Buddhas (Figure 24 and Figure 25). Both sculptures show the five transcendent Buddhas sitting in a row upon their vāhanas (vehicles). However, in these figures, only Vairocana is shown as a sambhogakāya Buddha with a crown, jeweled ornaments, and silk items; the other Buddhas are unadorned. This early iconography likely sets him apart from the others in order to mark his primary role in Vajrayāna Buddhism as the totality of all five insights (Snellgrove 1978). Consequently, the Guhyasamāja Tantra indicates a formulated iconography for the esoteric meditational construct of a sambhogakāya Buddha that is also reflected, in part, in some contemporary artworks from the Silk Road.

Figure 24.

Paῆca jina Buddhas with crowned Vairocana, seventh to eighth c. Kashmir. Brass. H 14.7 cm W. 25.6 cm. Po ta la Collection: Li ma lha khang: inventory no. 567. Red Palace, Lhasa, Tibet. https://himalayanbuddhistart.wordpress.com/category/all/tibet/buddhas-masculine-form/amitabha/.

Figure 25.

Paῆca jina Buddhas with crowned Vairocana. Possible Kashmir originally, now in Ladakh, Tibet, seventh to eighth c. Brass. Photograph courtesy of John C. Huntington.

4.7. Mahāvairocana abhisaṃbodhi Tantra

The Mahāvairocana abhisaṃbodhi Tantra, which is also called the Mahāvairocana Sūtra (hereafter called MVT), was most likely composed during the first half of the seventh century according to Stephen Hodge (2003), who also said that it is one of the first fully developed extant tantras.26 In this tantra, Mahāvairocana is indeed a supreme Ādi or Primordial Buddha.27 Thus, there is a clear reference to him as a sambhogakāya by describing him as blazing in light with his topknot, crown, and jeweled ornaments (Hodge 2003). Michael Saso (1990) pointed out that in the meditation, Vairocana is wearing the paῆca jina crown and is finely adorned. The imagery identifying Mahāvairocana as a sambhogakāya Buddha is further confirmed in the eighth century commentary on the sūtra by Buddhaguhya, where it directly states that Mahāvairocana is a sambhogakāya Buddha. In the MVT, Vairocana or Mahāvairocana as a transcendent Buddha not limited by time and space is also considered the universal sovereign. Tom Kasulis (2004) explained that the universe is a manifestation of the actions and deeds of Vairocana; thereby, this Buddha is at the core of everything in the cosmos. According to John Huntington (2003b), the Ādi Buddha “who, depending entirely on sectarian teachings, is actually the Dharmakaya or is a sambhoga kaya Buddha manifesting the Dharmakaya”. Therefore, Vairocana is the descriptor or manifestation of dharmakāya (Saso 1990; Huntington 2003b).

In the MVT, it is clear from the prescribed practice and the text itself that Mahāvairocana is a mind-manifested being. It says, “Know your mind as it really is. That is, the supreme, full and perfect enlightenment” (Hodge 2003). In other words, to know enlightenment is to know Mahāvairocana. Hodge (2003) explained that he manifests all three bodies of the trikāya in the tantra.28 The dharmakāya is Mahāvairocana’s mind, and since it is formless, it cannot be directly manifested. In this aspect, he is an Ādi Buddha, generating the mandala of the mind. Therefore, he is an archetypal enjoyment body Buddha and Ādi Buddha, and now he is worshiped and visualized through Vajrayāna practices (Saso 1990; Huntington and Chandrasekhar 2000; Huntington 2003b). Hence, the image of a crowned Buddha clearly evolved from the Mahāyāna universal sovereign to an esoteric conception.29

5. Crowned Buddha as Ādi Buddha

An Ādi Buddha is a primordial or supreme Buddha that is considered to be the essence of Buddhist dharma; they are dharmakāya in Mahāyāna and Vajrayāna Buddhism. Since the dharmakāya is non-representational, a visual depiction of an Ādi Buddha is regarded as a sambhogakāya manifestation (Huntington and Bangdel 2003). Some of the Ādi Buddhas include Vairocana, Vajrasattva, and Vajradhatu. Vairocana, as the embodiment of dharma, is the totality of the processes of the pañca jina Buddhas and an Ādi Buddha; therefore, he is the true teacher of esoteric Buddhism. In a conversation with John Huntington in 2005, he stated, “The Vairocana concept humanizes and reifies the teachings that generate all Buddhas.” In other words, Vairocana is implied in any and every Buddha, making him the perfect construct for the sambhogakāya and Ādi Buddha.

Vairocana in his sambhogakāya form can be distinguished by the silk items and jeweled ornaments. Interestingly, in early esoteric artworks in Tibet, the iconography of the cape was used as a means to distinguish an Ādi Buddha from other Buddhas (Von Schroeder 2001). For example, the four-pointed cape is placed on a rock carving of Vairocana abhisaṃbodhi (804–816 CE) at lDan ma brag in Eastern Tibet or Kahms (see Von Schroeder 2001, Figure xxi-9). The cape was also used in later images in Tibet to individualize the other Ādi Buddhas, such as Vajrasattva, Vajradhara, and Sarvavid Vairocana.

5.1. Representations of Mahāvairocana: Bodhyāgrī Mudrā

The artworks depicting the concept of a universal dharmakāya Buddha and theoretical practice of Vairocana as a meditational construct or sambhogakāya become more consistent in their iconography by the seventh to eighth century along the Silk Road. He no longer appears solely as a luminescent, colossal, or cosmic representation. Rather, Vairocana is depicted with the specific characteristics of a sambhogakāya that are described in the MVT, such as the crown, silk items (including those tied to the crown), and jeweled ornaments.

Moreover, the sambhogakāya and Ādi Buddha Mahāvairocana performs the bodhyāgrī mudrā that symbolizes supreme wisdom and immediate enlightenment. This mudrā is also called the bodhāgrī and the bodhyāngī mudra (fist of wisdom). The bodhyāgrī mudrā is formed by the index finger of the right hand pointing upwards, while the thumb and remaining fingers of the right hand make a fist. The fingers of the left hand wrap around the vertical right finger. As prescribed in the Sarva-tathāgata-tattva-saṃgraha (sixth to eighth c.) and the Sādhanamālā for Vairocana, this mudrā is specific to Vairocana, because it represents the totality of the five transcendental insights of the pañca jina Buddhas.30 As such, Vairocana is a manifestation of the supreme or highest enlightenment of the five (Chandra and Snellgrove 1981; Wilson and Brauen 2000). Therefore, as Chandrasekhar (2004) explained, the bodhyāgrī mudrā of Vairocana is, in essence, an attribute that conveys his primary nature as a meditational tantric Buddha.

In addition, this mudrā represents the union of wisdom and compassion, which is also representative of male and female principles in esoteric Buddhism (Huntington and Bangdel 2003; Snellgrove 1978). Therefore, it is the gesture or symbol of a promise of quick enlightenment; in other words, it is a symbol of the rapid Vajrayāna path. Thus, the bodhyāgrī mudrā denotes the highest enlightenment held by a dharmakāya Buddha in esoteric Buddhism.

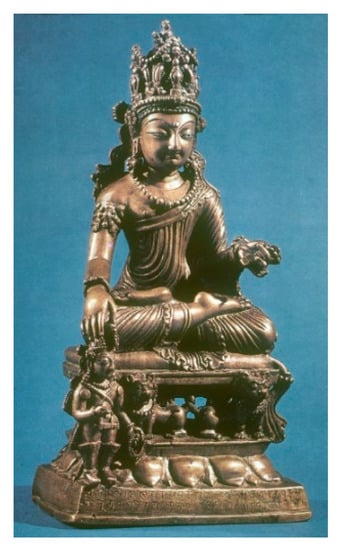

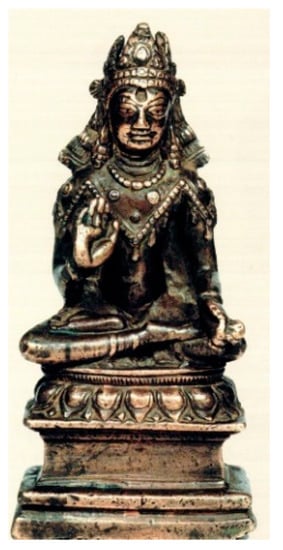

This iconography unequivocally identifies the eighth c. sculpture of Mahāvairocana from Kashmir (Figure 26) and the seventh to eighth c. sculpture from Gilgit (Von Schroeder 2001, pl. 23E). There are three similar sculptures of Vairocana from Swat, one from the seventh c. (Figure 27) and the other two from the eighth and ninth c. (Figure 28 and Figure 29). Another example is from Kashmir or Gilgit, dating to the ninth or early 10th c. (Figure 30). As esoteric constructs, they all consistently wear the silk items of the ribbons tied to the crown, a silk scarf, perhaps a sash at the waist, and the lower garment. They also wear the jeweled ornaments, including the crown, earrings, beaded necklace, armlets, bracelets, ring, and anklets. Thus, the iconography corresponds to Kün-zang Lama’s codified representation for a tantric sambhogakāya Buddha.

Figure 26.

Mahāvairocana in sambhogakāya form performing the bodhyāgrī mudrā, eighth c. Kashmir. Brass. Sri Pratap Singh Museum, Srinagar, Kashmir. Photograph from Pal, Bronzes of Kashmir, pl. 37.

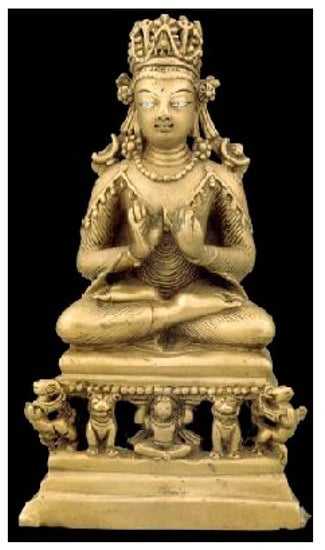

Figure 27.

Vairocana in sambhogakāya form performing the bodhyāgrī mudrā, seventh c. Swat. Brass with silver inlay eyes and copper inlay lips, 19 cm H. https://himalayanbuddhistart.files.wordpress.com/2012/10/7th-c-swat-valley-vairocana-brasssil-inlay-19-cm-rossi.jpg.

Figure 28.

Vairocana in sambhogakāya form performing the bodhyāgrī mudrā, eighth to ninth c. Swat. Copper alloy with silver inlay. Private collection. https://himalayanbuddhistart.wordpress.com/category/all/swat-valley-area/#jp-carousel-15485.

Figure 29.

Vairocana in sambhogakāya form performing the bodhyāgrī mudrā, eighth to ninth c. Swat. Bronze with silver inlay. 12.7 cm H. Private Collection. https://himalayanbuddhistart.files.wordpress.com/2012/10/8-9th-c-swat-valley-vairocana-bronzesil-eyes-127-cm-christies.jpg.

Figure 30.

Vairocana in sambhogakāya form performing the bodhyāgrī mudrā, ninth to early 10th c. From Pakistan (possibly Gilgit region). https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gandharan_Buddhism#/media/File:MET_DT5714.jpg.

5.2. Representations of Mahāvairocana: Dharmacakra-Pravartana Mudrā

Some scholars have argued that a figure can only be identified as Vairocana if he is performing the bodhyāgrī mudrā. However, there is another mudrā that acts as an iconographic signifier to identify Vairocana, although it is perhaps less known. It is the dharmacakra-pravartana mudra (Snellgrove 1978; Huntington and Chandrasekhar 2000; Von Schroeder 2001). This mudrā refers to the turning or teaching of the wheel of Buddhist law. Typically, in the dharmacakra mudra, the wheel is formed by the thumb and forefinger of the right hand in front of the chest, or where the seat of the heart–mind lies, while the index or second finger of the left hand points to the wheel. In the dharmacakra-pravartana mudrā, the right hand is creating the same wheel; however, the little or fourth finger of the left hand points to the wheel instead (Huntington and Chandrasekhar 2000).

While there are images of a Buddha using the index finger or the third or ring finger to point to the wheel, the symbolic meaning of the dharmacakra-pravartana mudrā especially relates to the use of the fourth finger of the left hand touching the dharmacakra formed in the right hand.31 Huntington and Chandrasekhar (2000) suggested that since a mudrā is a symbolic language, there is a sequential progression counted on the fingers in the mudrās that refers to a specific category of Buddhist teaching. In this case, this fourth or little finger pointing to the forefinger of the right hand refers to the fourth Buddhist teaching. They suggest that this might relate to the teachings of Zhiyi, the founder of the Tendai sect (Huntington and Chandrasekhar 2000).32 Zhiyi divided Śākyamuni’s teachings into five categories. The first category refers to the moment of Śākyamuni’s enlightenment and victory over Mara when he goes to Akaniṣṭha and teaches as Vairocana. The second teaching refers to the First Sermon at Deer Park, or what is known as Hinayāna or Sravakayāna Buddhism. The third category is the Mahāyāna Buddhist teachings. Since esoteric Buddhism is the last and most complex of the Buddhist teachings, it is suggested that the fourth teaching refers to Vajrayāna Buddhism. Therefore, the dharmacakra-pravartana mudrā is not only another means of depicting Vairocana as a sambhogakāya and Ādi Buddha—the embodiment of dharmakāya—it is also another symbolic reference to esoteric Buddhist teachings, which are the quickest and highest method of enlightenment through Vajrayāna Buddhism.

The dharmacakra-pravartana mudrā is known to be performed by Vairocana Buddha in the Durgatipariśodhana mandala in the eighth to ninth c. Niśpanna Yogavalī (Garland of Perfection Yoga) (Skorupski 1983). In the text, Vairocana is dressed in the monastic robes of Śākyamuni (meaning he is unadorned) and performs this mudra (Von Schroeder 2001).33 Chandrasekhar (2004) explained that the mudrās of Vairocana can also serve to underscore his sambhogakāya identity. In Buddhism, a mudrā is defined as a sign or a seal. It is a symbolic mark or seal of a vow to lead sentient beings to enlightenment; therefore, it is a visual manifestation of the permanent and absolute dharma. In other words, since he embodies the ultimate state of Buddhahood, he does not need an attribute; his mudrā is his symbol or promise. As the manifestation of dharmakāya, Vairocana does not need the crown and silks, since this mudrā also serves as a signifier of his mind-manifested sambhogakāya nature as an Ādi Buddha.

It is no surprise that the dharmacakra-pravartana mudrā is also found in images along the Silk Road, such as three Buddhas from Kashmir dating to the seventh to eighth century (Figure 31, Figure 32 and Figure 33).34 There is one from Swat as well, although it is dated much later (see Klimburg-Salter 1982, pl. 113). As the text describes, the unadorned Buddhas wear monastic robes and perform this mudrā.35 Through the iconographic signifier of the mudrā, they can be identified as Vairocana or Mahāvairocana: the quintessential enjoyment body Buddha.

Figure 31.

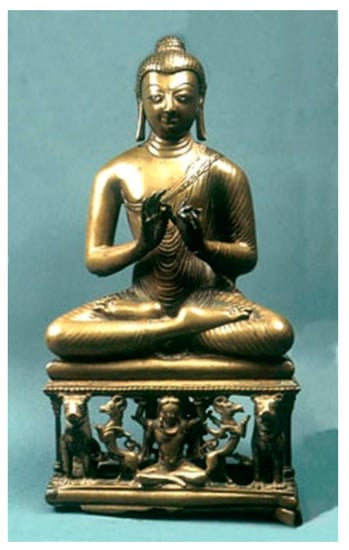

Vairocana Buddha performing the dharmacakra-pravartana mudrā. circa 725–750. India, Jammu and Kashmir, Kashmir region, South Asia. Brass inlaid with silver. 16 × 8 1/2 × 3 5/8 in. (40.64 × 21.59 × 9.2 cm). Nasli and Alice Heeramaneck Collection (M.69.13.5). LACMA. https://collections.lacma.org/node/236668.

Figure 32.

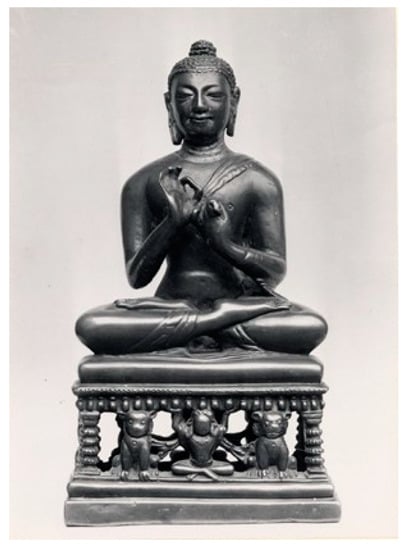

Vairocana Buddha performing the dharmacakra-pravartana mudrā. Kashmir eighth c. Gilded bronze, British Museum (1953,0718.1) http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_details/collection_image_gallery.aspx?assetId=57550001&objectId=247419&partId=1. Copyright@ Trustees of the British Museum.

Figure 33.

Vairocana Buddha performing the dharmacakra-pravartana mudrā. 7th c. Kashmir. Brass with cold gold and pigments from Tibet. https://himalayanbuddhistart.files.wordpress.com/2015/08/7th-c-kashmir-shakyamuni-brasspig-232-cm-karkota-potala.jpg.

Moreover, the dharmacakra-pravartana mudrā is commonly found on the Paṭola Śāhi Buddhas (Twist 2011). Four similar Paṭola Śāhi Vairocana Buddhas dating from the seventh to eighth c. are unadorned, wear monastic robes, and perform the dharmacakra-pravartana mudrā (Figure 34, Figure 35 and Figure 36). Interestingly, several crowned Buddhas from the Paṭola Śāhi dynasty featuring jewelry, flowing silk ribbons, a cape, and a crescent moon with a sun, perform the same mudrā as well, and therefore can likely be identified as Vairocana (Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 10 and Figure 11). In addition, a Buddha with all of the similar iconographic emblems comes from seventh Kashmir (Figure 37), while another similar Vairocana Buddha from the seventh to eighth c. comes from Gilgit or Kashmir (Figure 38).

Figure 34.

Buddha performing the dharmacakra-pravartana mudrā. From a pair of painted covers from Manuscript 3, Saṃghāṭa Sūtra, commissioned by Devaśirikā and Atthocasiṃgha, 627/628 C.E. Gilgit. Pigment on birch bark. 9” × 3”. Museum of the Institute of Central Asian Studies at Kashmir University, Srinigar, Kashmir. http://travelthehimalayas.com/kiki/2018/7/21/the-gilgit-manuscripts.

Figure 35.

Vairocana Buddha performing the dharmacakra-pravartana mudrā. Approx. 675–722 C.E. Kashmir or Gilgit. Brass with copper and silver inlay. 30.3 cm H. Po ta la Collection: Li ma lha khang: inventory no. 1383. Red Palace, Lhasa, Tibet. https://himalayanbuddhistart.wordpress.com/category/all/gilgit/#jp-carousel-178.

Figure 36.

Vairocana Buddha performing the dharmacakra-pravartana mudrā. Commissioned by Varṣa, 645 or 654 C.E. Kashmir or Gilgit. Brass. 29 cm H. Anna Maria Rossi and Fabio Rossi Collection (88515). https://www.himalayanart.org/items/88515. Copyright@ 2018 Himalayan Art Resources Inc.

Figure 37.

Vairocana Buddha wearing a crown and cape with crescent moon and sun symbols performing the dharmacakra-pravartana mudrā, seventh c. Kashmir. Brass with silver inlay. Private collection. https://himalayanbuddhistart.files.wordpress.com/2012/11/7th-c-kashmir-shakyamuni-brasssil-inlaid-eyes.jpg.

Figure 38.

Vairocana Buddha wearing a crown and jewelry performing the dharmacakra-pravartana mudrā, seventh to eighth c. Gilgit or Kashmir. Brass with silver and copper inlay. https://himalayanbuddhistart.files.wordpress.com/2015/08/7th-8th-c-gilgit-vairocana-brasssil-eyescop-lips-beaded-textile-2-donors-sharada-inscrip-identify-patron-bonhams.jpg.

6. Conclusions

Overall, there is a clear pattern of deliberate core iconographic elements that recur on crowned Buddha figures from the extant visual record of the Silk Road. On one level, the ideology could be intended to convey the notion of a cakravartin Buddha. Yet, I suggest that scholars do not need to restrict it to a singular interpretation. Rather, an analysis and contextualization reveals there is a multilayered significance to the crowned Buddha. The iconography presents a coded visual language to manifest a transcendent form of an enjoyment body Buddha. Therefore, the crown, silk ribbons, ornaments, and possibly the jeweled cape are iconographic signifiers of a sambhogakāya meditational construct. Moreover, the visual and textual evidence demonstrate the potential for some of these Buddhas to be identified as the esoteric archetypal sambhogakāya and Ādi Buddha Vairocana in Akaniṣṭha.

Thus, Vairocana can be identified not only through the sambhogakāya traits, but also with the two mudrās that serve as attributes and identifiers. Both the bodhyāgrī and dharmacakra-pravartana mudrā denote the highest enlightenment held by a dharmakāya Buddha in esoteric Buddhism, and thus convey his primary nature as a meditational tantric Buddha. Therefore, the iconography constructs Vairocana as a paradigm for early Vajrayāna symbology, practice, and attainment.36 Thus, the prolific examples from the various locations along the Silk Road demonstrate a systematic form of transmission and religious syncretism in both iconography and ideology.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest in the publication of this article.

References

- Banerjee, Priyatosh. 1992. New Light on Central Asian Art and Iconography. New Delhi: Abha Prakashan. [Google Scholar]

- Bangdel, Dina, and John C. Huntington. 2003. Buddhist Cosmology: Environment of Meditative Transformation—Mt. Meru. In The Circle of Bliss: Buddhist Meditational Art. Edited by John C. Huntington and Dina Bangdel. Chicago: Serindia Publications, pp. 66–69. [Google Scholar]

- Bautze-Picron, Claudine. 2010. The Bejewelled Buddha: From India to Burma, New Considerations. New Delhi: Sanctum Books. [Google Scholar]

- Beer, Robert. 1999. The Encyclopedia of Tibetan Symbols and Motifs. Boston: Shambhala. [Google Scholar]

- Chandra, Lokesh, and David L. Snellgrove. 1981. Sarva-Tathāgata-tattva-saṃgraha. New Delhi: Sharada Rani. [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekhar, Chaya. 2004. Pāla-Period Buddha Images: The Hands, Hand Gestures, and Hand-Held Attributes. Ph.D. dissertation, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Chegwan, Monk. 1983. T’en-T’ai Buddhism: An Outline of the Fourfold Teachings. Translated by The Buddhist Translation Seminar of Hawaii. Tokyo: Daiichi-Shobo. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas Cleary, trans. 1993, The Flower Ornament Scripture: A Translation of the Avatamsaka Sūtra. Boston: Shambhala Publications, Inc.

- Coomaraswamy, Ananda K. 1928. The Buddha’s cūḍā, Hair, uṣṇīsa, and crown. JRAS 60: 815–41. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham, Cathleen A. 2003. Guhysamaja Tantra. In The Circle of Bliss: Buddhist Meditational Art. Edited by John C. Huntington and Dina Bangdel. Chicago: Serindia Publications, pp. 432–35. [Google Scholar]

- Dasgupta, Shashi Bhushan. 1974. An Introduction to Tantric Buddhism, 3rd ed.Kolkata: Calcutta University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fussman, Gérard. 1994. Chilas-Thalpan et L’art du Tibet. In Antiquities of Northern Pakistan: Reports and Studies. Mainz: Verlag Philip von Zabern, vol. 3, pp. 57–72. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths, Paul J. 1989. The Realm of Awakening: A Translation and Study of the tenth chapter of Asaṅga’s Mahāyānasaṃgraha. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths, Paul J. 1994. On Being Buddha—The Classical Doctrine of Buddhahood. Albany: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hanson, Mervin Viggo. 1980. The Trikāya: A Study of the Buddhology of the Early Vijñanavada School of Indian Buddhism. Ph.D. dissertation, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Hodge, Stephen. 2003. Māha-vairocana-abhisaṃbodhi tantra with Buddhaguhya’s Commentary. London: RoutledgeCurzen. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, Angela Falco. 1986. The Imagery of the Cosmological Buddha. Leiden: E.J. Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Huntington, John C. 1981. Cave Six at Aurangabad: A Tantrayåna Moment. In Kalādarśana-American Studies in the Art of India. Edited by Joanna G. Williams. Collaboration with American Institute of Indian Studies. New Delhi, Bombay and Calcutta: Oxford and IBH Publishing Co., pp. 47–55. [Google Scholar]

- Huntington, John C., and Chaya Chandrasekhar. 2000. The Dharmacakramudrā Variant at Ajanta: An Iconological Study. Ars Orientalis 1: 33–39. [Google Scholar]

- Huntington, John C., and Dina Bangdel, eds. 2003. The Circle of Bliss: Buddhist Meditational Art. Chicago: Serindia Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Huntington, John C. 2003a. Practitioner as Perfected Being: Meditations on Vajrasattva. In The Circle of Bliss: Buddhist Meditational Art. Edited by John C. Huntington and Dina Bangdel. Chicago: Serindia Publications, pp. 208–11. [Google Scholar]

- Huntington, John C. 2003b. Vairochana and Vajradhara: Visually Communicating the Buddhist Notion of Universality. In The Circle of Bliss: Buddhist Meditational Art. Edited by John C. Huntington and Dina Bangdel. Chicago: Serindia Publications, pp. 80–81. [Google Scholar]

- Huntington, John C. 2003c. Buddhist Cosmology: Environment of Meditative Transformation: Mt. Meru. In The Circle of Bliss: Buddhist Meditational Art. Edited by John C. Huntington and Dina Bangdel. Chicago: Serindia Publications, pp. 66–69. [Google Scholar]

- Huntington, Susan L., and John C. Huntington. 1990. Leaves from the Bodhi Tree: The Art of Pāla India (8th–12th centuries) and Its International Legacy. Seattle and London: The Dayton Art Institute in Association with University of Washington Press. [Google Scholar]

- John James Jones, trans. 1973–1978, The Mahāvastu. London: The Pali Text Society, Boston: Routledge and Kegan Paul Ltd., vols. 1–3.

- Kasulis, Thomas P. 2004. Shinto—The Way Home. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. [Google Scholar]

- Translated and Edited by Sonam T. Kazi. 1989–1993, Kün-zang la-may zhal-lung: The Oral Instruction of Kün-zang La-ma on the Preliminary Practices of Dzog-ch’en Long-ch’en Nying-tig. Upper Montclair: Diamond-Lotus Publishing, vols. 4, 5.

- Kiyota, Minoru. 1978. Shingon Buddhism: Theory and Practice. Los Angeles-Tokyo: Buddhist Books International. [Google Scholar]

- Kiyota, Minoru. 1982. Tantric Concept of Bodhicitta: A Buddhist Experiential Philosophy—An Exposition based upon the Mahāvairocana-sütra, Bodhicitta-śāstra and Sokushin-jōbutsu-gi. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Klimburg-Salter, Deborah. 1982. The Silk Route and the Diamond Path: Esoteric Buddhist Art on the Trans-Himalayan Trade Routes. Los Angeles: Published under the Sponsorship of the UCLA Art Council. [Google Scholar]

- Klimburg-Salter, Deborah. 1989. Kingdom of Bāmiyān: Buddhist Art and Culture of the Hindu Kush. Naples and Rome: Istituto Italiano per il Medio ed Estremo Oriente. [Google Scholar]

- Krishan, V. 1971. The Origin of the Crowned Buddha. East and West XXI: 91–96. [Google Scholar]

- Linrothe, Rob. 1999. Ruthless Compassion—Wrathful Deities in Early Indo-Tibetan Esoteric Buddhist Art. London: Serindia Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Linrothe, Rob. 2014. Collecting Paradise: Buddhist Art of Kashmir and its Legacies. New York: Ruben Museum of Art and the Mary and Leigh Block Museum of Art, Northwestern University. [Google Scholar]

- Livingston, Amy. 2003. Enlightenment Symbolized: The Five Jina Buddhas. In The Circle of Bliss: Buddhist Meditational Art. Edited by John C. Huntington and Dina Bangdel. Chicago: Serindia Publications, pp. 90–92. [Google Scholar]

- Mus, Paul. 1928. Le Buddha Paré. Son Origine Indienne. Śakyamuni dans le Mahāyānism moyen. Bulletin de l’École Française d’Extrême-Orient XXVIII: 153–278. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, Pran Gopal. 1986. Early Sculpture of Kashmir: Before the Middle of the 8th Century. Ph.D. dissertation, Rijksuniversiteit te Leiden, Leiden, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Rowland, Benjamin. 1961. The Bejeweled Buddha in Afghanistan. Artibus Asiae XXIV: 20–24. [Google Scholar]

- Saso, Michael. 1990. Tantric Art and Meditation: The Tendai Tradition. Honolulu and Hawaii: University of Hawaii Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schopen, Gregory. 1976. Three Studies in Non-Tantric Buddhist Cult Form. Master’s thesis, McMaster University, Hamilton, ON, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Siudmak, John. 2013. The Hindu-Buddhist Sculpture of Ancient Kashmir and its Influence. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Skorupski, Tadeusz. 1983. The Sarvadurgatiparśodhana Tantra: Elimination of all Evil Destinies. Delhi, Varnasi and Patna: Motilal Banarsidass. [Google Scholar]

- Snellgrove, D. L. 1959. The Notion of Divine Kingship in Tantric Buddhism. In The Sacral Kingship—Contributions to the Central Theme of the XIIIth International Congress for the History of Religions, Rome, April, 1955. Leiden: E.J. Brill, pp. 204–18. [Google Scholar]

- Snellgrove, David L., ed. 1978. The Image of the Buddha. Paris: United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization, Tokyo: Kodansha International. [Google Scholar]

- Taddei, Maurizio. 1989. The Bejewelled Buddha and the Mahiṣāsuramardinī: Religion and Political Ideology in Pre-Muslim Afghanistan. South Asian Archaeology, 457–64. [Google Scholar]

- Twist, Rebecca L. 2011. The Patola Shahi Dynasty: A Buddhological Study of their Patronage, Devotion and Politics. Germany: VDM Verlag Dr. Müller. [Google Scholar]

- Von Hinüber, Oskar. 2004. Die Palola Ṣāhis: ihre Steinenschriften, Inschriften auf Bronzen, Handschriftenkolophone und Schutzzauber—Materialen zur Geschlichte von Gilgit und Chilas. In Antiquities of Northern Pakistan: Reports and Studies. Mainz: Philipp von Zabern, vol. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Von Schroeder, Ulrich. 2001. Buddhist Sculptures in Tibet. Hong Kong: Visual Dharma Publications Ltd., vols. 1, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Wallis, Glenn. 1999. The Persistence of Power: Ritual in the Mañjuśrīmūlakalpa. Ph.D. dissertation, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Walter, Mariko Namba. 1997. Kingship and Buddhism in Central Asia. Ph.D. dissertation, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Burton Watson, trans. 1993, The Lotus Sūtra. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Williams, Paul. 1989. Mahāyāna Buddhism—The Doctrinal Foundations. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, Martin, and Martin Brauen. 2000. Deities of Tibetan Buddhism: The Zurich Painting of the Icons Worthwhile to See (Bris sku mthon ba don Ldan). Boston: Wisdom Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, Guang. 2005. The Concept of the Buddha: Its Evolution from Early Buddhism to the Trikāya Theory. London and New York: RoutledgeCurzon. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Rowland (1961) suggests that the ornamentation was added to distinguish Mahāyāna Buddha images from Hinayāna ones. |

| 2 | For example, in Mahāyāna Buddhism, a tenth-stage or great bhūmi bodhisattva is an advanced being who has completed the practice of the ten dharmas of the ten bhūmis. The bodhisattvas at this level perform intense meditation, allowing them to visualize or experience various Buddhas and to receive the teachings. On the 10th bhūmi, which is equivalent to attaining the dharmakāya, the bodhisattva is on the threshold of Buddhahood (Griffiths 1994; Xing 2005). |

| 3 | Klimburg-Salter (1989) stated that originally, flames on the shoulders were used in early iconography for this purpose, which were then replaced by the moon and sun symbols. |

| 4 | Klimburg-Salter (1989) stated that this ceremony was found in China from the sixth to eighth century and Japan from the sixth to the 11th century. |

| 5 | It is not clear if there is a symbol of a sun and moon on the shoulders or not. According to Klimburg-Salter (1989), there are flame-like emblems on the shoulders. She provided images of other crowned Buddhas with capes at Bamiyan, such as in the colossal Buddha niche (Klimburg-Salter 1989, Figures 31, 35, 36); one in cave S (Figure 33); and in cave K on the ceiling (Figure 5). |

| 6 | David Snellgrove (1978) suggested that the Buddha had a metal crown originally. There is also a Buddha figure made of clay from Tapa Sardar on the left wall in Chapel 23 who wears monastic robes and a cape. This is discussed in (Taddei 1989). |

| 7 | For an additional example, see the Buddha wearing a crown and cape with crescent moon and sun symbols that was commissioned by the monk Bhadradharma and his parents, 679/680 C.E. Gilgit. Brass with silver inlay. 20.5 cm H × 20.2 cm W. Po ta la Collection: Sa gsum lha khang: inventory no. 82. Red Palace, Lhasa, Tibet, in Ulrich von Schroeder (2001, pl. 22). |

| 8 | Two other crowned Buddhas of a similar artistic idiom are believed to be from Gilgit as well or perhaps Kashmir. (See (von Schroeder 2001, pl. 25A and 25B) or (Twist 2011, Figures A25 and A26)). |

| 9 | The silk ribbons were likely derived from royal crowns on historical kings, thus becoming a symbol of royalty used by Buddhist artists. This could have originated from the Iranian or Sassanian kings, perhaps back to the Achamenids. The ribbons are also attached to carved images of stūpas along the Silk Road for similar royal symbology. |

| 10 | For a similar Buddha located in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, see Pal, Bronzes of Kashmir, pl. 36. |

| 11 | Several scholars argue that the cape motif is from a famous image at the Mahabodi Temple in Bodh Gaya. This suggestion comes from a ninth c. painting discovered at Dunhuang that has the following inscription: “Country of Magadha light emitting magical image.” See (Rowland 1961). It is believed that this painting was a representation of the same Buddha at Bodh Gaya, and it bears a cape and crown. However, the cape is different, with scalloped edges rather than the distinct four corners found on the Buddha images used for this article. The only cape I found that was similar with the scalloped edges is on the stone-carved crowned Gilgit Buddha. |

| 12 | Evidence of this can even be seen on some of these artworks. For example, both the Paṭola Śāhi king and queen donors of the Buddha in Figure 5 have crescent moons with a solar symbol inside of it decorating their crowns. Moreover, Klimburg-Salter (1989) pointed out examples at Bamiyan and Fondukistan with other variations of the heavenly symbols incorporated into the decoration of the crowns used for kings. It is possible that these motifs also derive from the Sassanians, such as the silk ribbons on the crown. |

| 13 | I agree that the iconography clearly has references to kingship; this is discussed in several chapters in (Twist 2011). |

| 14 | The trikāya system was developed primarily by Asaṅga, his teacher Maitreya, and his brother Vasubandhu in fourth century India. Together, they are often credited with establishing a new school of thought in Mahāyāna Buddhism called Yogācāra. The earliest texts written by the sect introducing the trikāya system are the Mahāyānasūtrālaṃkāra by Maitreya and the Mahāyānasaṃgraha by Asaṅga. See (Hanson 1980, pp. 62–65; Griffiths 1989). |

| 15 | The five insights are: Akshobhya = mirror-like wisdom; Ratnasambhava = equality of all things; Amitabha = discriminating wisdom; Amoghasiddhi = perfected action; and Vairocana = full understanding of truth and reality. Each jina Buddha presides over what is called a Buddha family or kula, each with their own color, direction, mudrā, symbol, and female prajñā (partner). For a detailed discussion on the pañca jina Buddhas, see (Livingston 2003). |

| 16 | An example of the pañca jina crown’s esoteric function can be seen with the Vajrasattva headdress when it is used in public rituals in Nepal. When the practitioner places the crown on his head, he becomes purified as an adamantine being, and transformed into the deity Vajrasattva. The practitioner can then perform the Buddhist ritual with authority and full knowledge of the secret rites. This marks the knowledge and power that are inherent in the crown. The crown is part of esoteric initiations as well. John Huntington suggested that, because their concept is so fundamental in Vajrayāna Buddhism, the jina Buddhas are inherent in every piece of esoteric art, including the five-pointed crown (Huntington and Bangdel 2003). |

| 17 | Mt. Meru is conceptually the center of the Buddhist world system; it not a physical place, but a conceptual one, where almost all meditation and all levels of Buddhist attainments occur. Since every Buddha has attained highest enlightenment, Mt. Meru symbolism is inherent in all Buddhist artworks, architecture, and practice. See (Huntington 2003c). |

| 18 | According to Shashi Bhushan Dasgupta (1974), Vajrayāna Buddhism practiced in Nepal uses the sun and moon symbols to express male and female. The crescent moon symbolizes the female element, and the flame inside it is the male aspect, representing their union. The union of male and female as a symbol of non-duality is an important concept in esoteric methodologies. Perhaps the version of the crescent moon with the rosette sun on these images is an earlier prototype for this metaphor of non-duality through the union of male and female. Pairing of male and female donors is also found with the Paṭola Śāhi sculptures, see discussion in (Twist 2011). |

| 19 | However, the text does briefly mention the name of Vairocana in relation to a universal king. It says, “Suprabhasa was tathāgata and a perfect Buddha when the bodhisattva Maitreya, as the universal king Vairocana, was aiming at perfect enlightenment in the future and first acquired the roots of goodness” (Jones 1973–1978). |

| 20 | For discussion on the dharmadhātu in the Avatamsaka, see (Griffiths 1994, 122 ff). |

| 21 | Scholars debate over the dates. Although Wallis (1999) said it is early, Rob Linrothe (1999) claimed it is from the sixth to seventh century, with later parts from the eighth century. |

| 22 | It is not within the scope of this article to argue whether this text is Mahāyāna or early Vajrayāna. For the sake of this study, it is considered, at least, proto-Vajrayāna with many esoteric elements. |

| 23 | The GS tantra was originally associated with the Sarva Tathāgata Tattva Saṃgraha in the sixth to seventh c. as a supreme uttaratantra in India. |

| 24 | For Tibetan images of Guhyasamāja from the 12th and 15th c., see (Huntington and Bangdel 2003, pl. 134, 135; and Huntington and Huntington 1990, pl. 127). |

| 25 | Huntington (2003b) and Snellgrove (1978) explain that sambhogakāya jina Buddhas began with three Buddha families rather than five, consisting of the Tathāgata or Buddha Family (Vairocana), the Vajra family (Akṣobhya), and the Padma family (Amitābha). By the fourth to fifth century, the three developed into the five families, manifesting the jina Buddhas. |

| 26 | The sūtra was taken to China by the monk Śubhākarasiṃha (637–735). Hodge (2003) suggested a date for the sūtra around 640 C.E., making it a true tantra of the early phase. Śubhākarasiṃha spent two years in Kashmir learning the tantra before going to China (Huntington 1981). The tantra then made it to Japan by the early ninth c. (Snellgrove 1959). This sūtra features the Gharbadhātu mandala with Vairocana at the center, and it is used in both Shingon and Tendai Buddhism in Japan. For a discussion of the transmission to Japan, see (Kiyota 1978, pp. 11–14). |