Folklore and the Internet: The Challenge of an Ephemeral Landscape1

Abstract

:While mass-mediated communication technologies have empowered the institutional, participatory media offer powerful new channels through which the vernacular can express its alterity. However, alternate voices do not emerge from these technologies untouched by their means of production. Instead, these communications are amalgamations of institutional and vernacular expression. In this situation, any human expressive behavior that deploys communication technologies suggests a necessary complicity. Insofar as individuals hope to participate in today’s electronically mediated communities, they must deploy the communication technologies that have made those communities possible. In so doing, they participate in creating a telectronic world where mass culture may dominate, but an increasing prevalence of participatory media extends into growing webs of network-based folk culture.

no other discipline is more concerned with linking us to the cultural heritage from the past than is folklore; no other discipline is more concerned with revealing the interrelationships of different cultural expressions than is folklore; and no other discipline is more concerned, or no other discipline should be more concerned, with discovering what it means to be human. It is this attempt to discover the basis of our common humanity, the imperatives of our human existence, that puts folklore study at the very center of humanistic study.

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Blank, Trevor J., ed. 2009. Folklore and the Internet: Vernacular Expression in a Digital World. Logan: Utah State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Blank, Trevor J., ed. 2012. Folk Culture in the Digital Age: The Emergent Dynamics of Human Interaction. Logan: Utah State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Blank, Trevor J. 2013a. The Last Laugh: Folk Humor, Celebrity Culture, and Mass-Mediated Disasters in the Digital Age. Folklore Studies in a Multicultural World Series; Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. [Google Scholar]

- Blank, Trevor J. 2013b. Hybridizing Folk Culture: Toward a Theory of New Media and Vernacular Discourse. Western Folklore 72: 105–30. [Google Scholar]

- Blank, Trevor J. 2015. Faux Your Entertainment: Amazon.com Product Reviews as a Locus of Digital Performance. Journal of American Folklore 128: 286–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blank, Trevor J. 2016. Giving the “Big Ten” a Whole New Meaning: Tasteless Humor and the Response to the Penn State Sexual Abuse Scandal. In The Folkloresque: Reframing Folklore in a Popular Culture World. Edited by Michael Dylan Foster and Jeffrey A. Tolbert. Boulder: Utah State University Press, pp. 147–72. [Google Scholar]

- Bronner, Simon J. 2009. Digitizing and Virtualizing Folklore. In Folklore and the Internet: Vernacular Expression in a Digital World. Edited by Trevor J. Blank. Logan: Utah State University Press, pp. 21–66. [Google Scholar]

- Buccitelli, Anthony Bak. 2012. Performance 2.0: Observations toward a Theory of the Digital Performance of Folklore. In Folk Culture in the Digital Age: The Emergent Dynamics of Human Interaction. Edited by Trevor J. Blank. Logan: Utah State University Press, pp. 60–84. [Google Scholar]

- Carmichael, Emma. 2011. This Is What Happens When ESPN.com Attempts to Fight Back. Deadspin. November 2. Available online: http://deadspin.com/5855836/this-is-what-happens-when-espncom-attempts-to-fight-back (accessed on 5 November 2011).

- Caughey, John L. 1984. Imaginary Social Worlds: A Cultural Approach. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. [Google Scholar]

- Craggs, Tommy. 2011. The Stupid Moral Panic over Mocking Tim Tebow; Or, What Would Jesus Do about Tebowing? Deadspin. November 4. Available online: http://deadspin.com/5856237/the-stupid-moral-panic-over-mocking-tim-tebow-or-what-would-jesus-do-about-tebowing (accessed on 5 November 2011).

- Davies, Christie. 1999. Jokes on the Death of Diana. In The Mourning for Diana. Edited by Tony Walter. New York: Berg, pp. 253–68. [Google Scholar]

- Dundes, Alan. 1966. Metafolklore and Oral Literary Criticism. The Monist 50: 505–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogarty, Dan. 2011. ESPN.com Comment Thread Descends into Chaos Because of Tim Tebow’s Lackluster Play. Sportsgrid.com. November 1. Available online: http://www.sportsgrid.com/real-sports/nfl/greater-than-tebow/ (accessed on 3 November 2011).

- Foster, Michael Dylan. 2016. Introduction: The Challenge of the Folkloresque. In The Folkloresque: Reframing Folklore in a Popular Culture World. Edited by Michael Dylan Foster and Jeffrey A. Tolbert. Boulder: Utah State University Press, pp. 3–36. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, Michael Dylan, and Jeffrey A. Tolbert, eds. 2016. The Folkloresque: Reframing Folklore in a Popular Culture World. Boulder: Utah State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, Robert Glenn. 2005. Toward a Theory of the World Wide Web Vernacular: The Case for Pet Cloning. Journal of Folklore Research 42: 323–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, Robert Glenn. 2008. Electronic Hybridity: The Persistent Processes of the Vernacular Web. Journal of American Folklore 121: 192–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, Jeana. 2016. #FolkloreThursday: Digital Folklore & Internet Folklore. Patheos. March 31. Available online: http://www.patheos.com/blogs/foxyfolklorist/folklorethursday-digital-folklore-internet-folklore/ (accessed on 25 January 2017).

- Kapchan, Deborah A., and Pauline Turner Strong. 1999. Theorizing the Hybrid. Journal of American Folklore 112: 239–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, Merrill. 2013. Curation and Tradition on Web 2.0. In Tradition in the Twenty-First Century: Locating the Role of the Past in the Present. Edited by Trevor J. Blank and Robert Glenn Howard. Logan: Utah State University Press, pp. 123–48. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley, Greg. 2016. “The Joke’s On Us”: An Analysis of Metahumor. In The Folkloresque: Reframing Folklore in a Popular Culture World. Edited by Michael Dylan Foster and Jeffrey A. Tolbert. Boulder: Utah State University Press, pp. 205–20. [Google Scholar]

- Malmsheimer, Lonna M. 1986. Three Mile Island: Fact, Frame, and Fiction. American Quarterly 38: 35–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeill, Lynne S. 2015. “The Internet is Weird”: Folkloristics in the Digital Age. Folklore Fellows Network 47: 12–13, 16–17. [Google Scholar]

- Oring, Elliott. 2008. Engaging Humor. Champaign: University of Illinois Press. First published 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Petchesky, Barry. 2011. How Contempt for Tim Tebow Caused an ESPN.com Commenter Revolution. Deadspin. November 2. Available online: http://deadspin.com/5855575/how-contempt-for-tim-tebow-caused-an-espncom-commenter-revolution (accessed on 5 November 2011).

- Stross, Brian. 1999. The Hybrid Metaphor: From Biology to Culture. Journal of American Folklore 112: 254–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, William A. 1988. The Deeper Necessity: Folklore and the Humanities. Journal of American Folklore 101: 156–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | An earlier version of this paper was presented as “Authoring and Curating Meaning in the Digital Age: Ethnographic Considerations for Documenting Hybridity, Cultural Inventory, and Performative Vernacular Expression” at the Folklore Fellows’ Summer School 2015, Doing Folkloristics in the Digital Age, 15 June 2015, in Seili, Finland. My deepest thanks to the FFSS coordinators and summer school attendees whose feedback and engagement with the lecture provided incredibly thoughtful and adept suggestions for strengthening my argumentation and organization. |

| 2 | A stable URL hosting the article can be found at http://www.espn.com/blog/afcwest/post/_/id/34680/time-for-elway-to-think-post-tebow. |

| 3 | By October 2011, Tebow’s popularity was so ubiquitous that his practice of kneeling down on one knee to pray after completing a touchdown inspired the meme known as “Tebowing” (a variant of “planking”) in which individuals posed in the kneeling prayer position in pictures and posted them on the Internet. See http://knowyourmeme.com/memes/tebowing for more information on the Tebowing meme. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Planking_(fad) for a folk moderated write-up on the planking meme that served as a pretext to “Tebowing”. |

| 4 | As more X > Tebow jokes appeared, “a corpus of their general characteristics [were] cognitively registered by readers”, with the characteristics serving as “contextual cues for recognizing and interpreting these communication events as expressive performances” (Blank 2015, p. 290). The top-ranked comment was “Knock knock?…. Who’s there?…. Doesn’t matter, it’s > Tebow.” [Collected 4 November 2011] Some commenters acknowledged the rating system’s implicit bias and folk manipulation: “trying to find my post so I can see if anyone likes it, thereby confirming to myself that I really am witty > Tebow” and “Liking your own post > Tebow”, which was followed by the original poster with “Replying to your own post > Tebow.” [Collected 3 November 2011] See Blank (2015, pp. 289–92) for a discussion on how individuals utilize and/or play with a website’s rating system for humorous and counter-hegemonic purposes. |

| 5 | For example, “Legally marrying a McRib sandwich > Tebow”, “Eating your kids > Tebow”, and “Coke-Boogers > Tebow.” [Collected 1 November 2011]. |

| 6 | Examples include “making eye contact with a 40-year-old man while he’s eating a banana > Tebow” and “That awkward moment when my doctor is checking my balls during a physical and I run my fingers through his hair > Tebow.” [Collected 4 November 2011]. |

| 7 | One popular thread made explicit reference to the 1990 computer game, The Oregon Trail: Getting Scurvy on Oregon trail > Tebow ↳ Getting dysentery on Oregon Trail > Tebow ↳ Trying to ford the river instead of caulking the wagon > Tebow ↳ Getting robbed by Indians in Oregon Trail > Tebow ↳ Wasting all your bullets on a squirrel and then seeing a bear run by > Tebow These comments show a keen awareness of not only the game but folk knowledge surrounding strategies for succeeding within it, as well as common pitfalls players experienced and other uniting factors that helped coalesce the thread in a united humor front. Each of the posts in the thread were made by different individuals. [Collected 5 November 2011]. |

| 8 | Examples include “Michael Jackson calling Boyz II Men because he thought it was a delivery service > Tebow”—a derivative of a joke I collected around the time of Jackson’s death in 2009 (see Blank 2013a, pp. 83–98)—and “Calling Shotgun in Princess Diana’s car > Tebow”—a play on the jokes surrounding Princess Diana’s death in 1997 (Blank 2013b, pp. 40, 125n7; see also Davies 1999). Others tapped into their cultural inventories (Blank 2013a, 2016; Malmsheimer 1986) to make humorous remarks. For example, calling upon knowledge about the actor’s Parkinson’s diagnosis, “Michael J. Fox’s Etch-A-Sketch drawings > Tebow” and “Yelling the N word at a DMX [a black gangsta rapper] concert > Tebow.” [Collected 6 November 2011]. |

| 9 | Representative examples include “Tebow calling third-downs ‘Muslims’ because they’re so hard to convert > Tebow” and “Buying a player’s jersey because he has the same imaginary friend as you > Tebow” [Collected 3 November 2011]. |

| 10 | For example, “Bill Williamson [ESPN article author] getting an E-mail notification after each comment on his blog post > Tebow” and “Being part of the first ESPN thread that hits 1,000,000 posts > Tebow”, an acknowledgment of both the community atmosphere and meta-awareness of the thread’s potency. [Collected 1 November 2011]. |

| 11 | One popular joke posted read “having more espn accounts than tebow has [pass] completions > Tebow” [Collected 3 November 2011, right at the height of ESPN’s initial effort to delete posts and suspend user accounts]. This joke relies on the folk knowledge that an ESPN.com account is required to post to the comments section while also highlighting the defiance of commenters intent on disrupting both the ESPN article’s comment section and mocking Tim Tebow all at once. |

| 12 | My thanks to David J. Puglia for drawing my initial attention to the “Greater Than Tebow” thread. |

| 13 | Importantly, moderators did temporarily retreat for a day on 2 November, 2011 after it was obvious that too many commenters were overwhelming their servers. This was seen as a major victory for commenters (see Carmichael 2011; Fogarty 2011). ESPN.com moderators revamped their approach beginning 3 November, 2011 and began suspending accounts in addition to deleting posts. |

| 14 | It is important to note, however, that the meme did periodically appear on non-ESPN websites, including Deadspin and Fark.com, to name a few, although the phenomenon was most nascent on ESPN.com, where the meme originated. Additionally, there were instances of people bringing “> Tebow” signs to football games in the days following the article’s publication, which also points to the hybridity of the phenomenon. |

| 15 | |

| 16 | As Greg Kelley (2016) observes, the comic value of a joke often depends upon an audience’s awareness of the joke’s antecedent for successful deployment (see also Oring [2003] 2008, p. 56). This was certainly the case with the “Greater Than Tebow” jokes that I collected from 1 November to 9 November, 2011. See also Blank (2016) and Dundes (1966, p. 510) on metafolklore and its applications to joke formulas and Foster and Tolbert (2016) for more comprehensive analyses of the intersections of folklore and popular culture. |

| 17 | Indeed, the sometimes slow pace of the academic publication process makes it difficult to document and analyze cultural phenomena synchronously. Also, as Michael Dylan Foster notes, there is often “a time lag between the professional world and the popular culture world, between academic inception and vernacular reception” (Foster 2015, p. 17). |

| 18 | |

| 19 | Although penned before the advent of the World Wide Web and new media technologies, anthropologist John L. Caughey (1984) has thoughtfully used the term “imaginary social worlds” to differentiate between individuals’ face-to-face interactions and “artificial” social planes derived from interactions with television, radio, movies, books, magazines, and newspapers. My conceptualization of cultural inventory has assuredly been influenced by Caughey’s work. See also Malmsheimer (1986, pp. 36–37). |

| 20 | For example, a narrator reads line such as “In a past life, he was himself”, “He can slam a revolving door”, “If opportunity knocks and he’s not home, opportunity waits”, and “He gave his father ‘the talk’”. These overtures are reminiscent of “Chuck Norris” jokes that popularly circulated in oral and digital repertoires in the early twenty-first century. My thanks to the peer reviewer of this piece for drawing attention to this connection. |

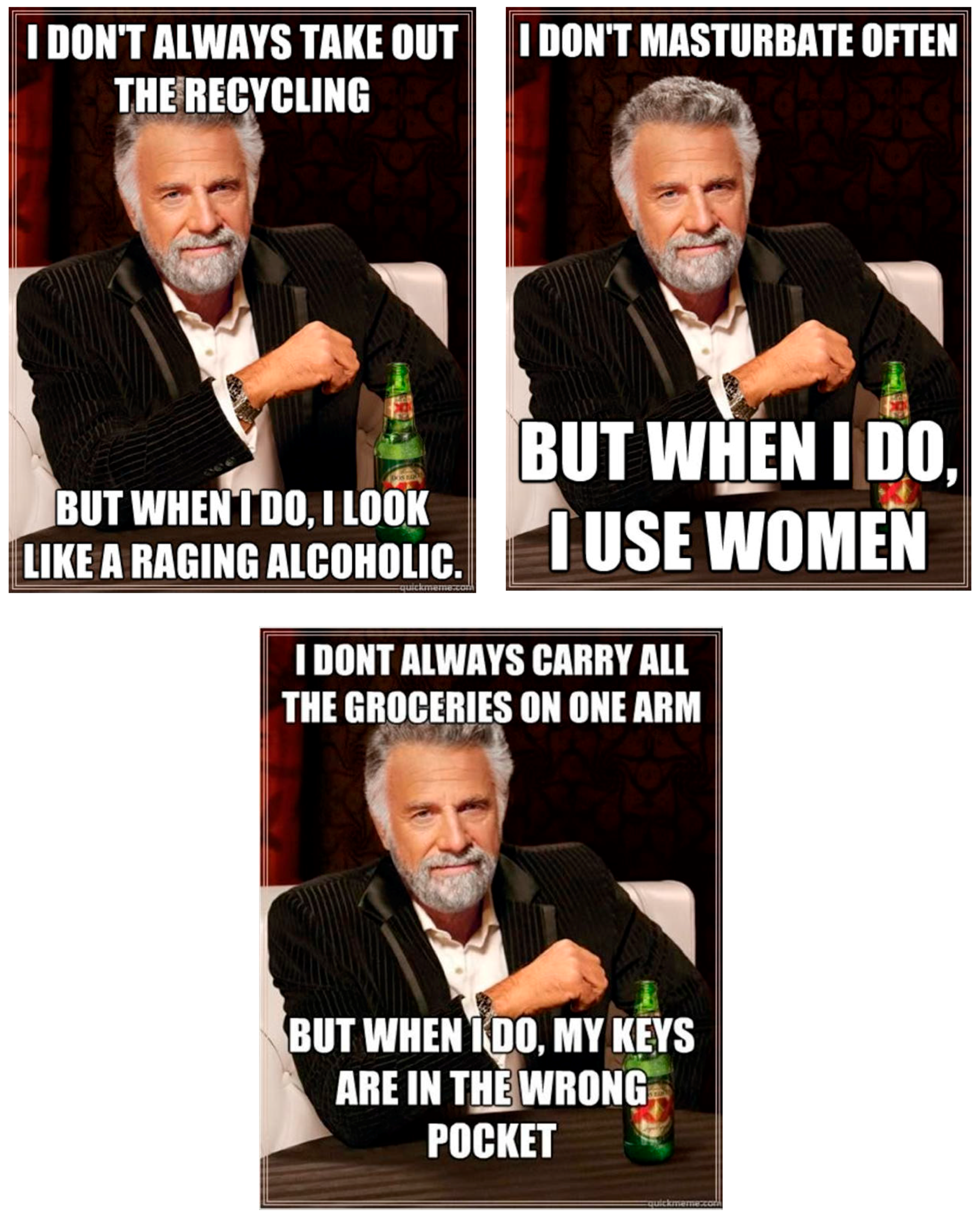

| 21 | The Google Trends analytics chart, showing the chronological search popularity for the Most Interesting Man in the World in Google’s recorded history, can be found at https://trends.google.com/trends/explore?date=all&q=most%20interesting%20man%20in%20the%20world. The data also shows that search queries took place predominantly in North America, which makes sense given the Dos Equis brand’s marketing efforts on the continent. |

| 22 | See http://knowyourmeme.com/memes/the-most-interesting-man-in-the-world for additional information on the meme, as well as more examples of variations collected. |

| 23 | This is reminiscent of Simon J. Bronner’s cataloging of Budweiser pun jokes after the suicide of Pennsylvania politician R. Budd Dwyer (Bronner 2009, pp. 46–47, 49). |

| 24 | See Foster and Tolbert (2016) for a more extensive treatment of the folkloresque. |

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Blank, T.J. Folklore and the Internet: The Challenge of an Ephemeral Landscape1. Humanities 2018, 7, 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/h7020050

Blank TJ. Folklore and the Internet: The Challenge of an Ephemeral Landscape1. Humanities. 2018; 7(2):50. https://doi.org/10.3390/h7020050

Chicago/Turabian StyleBlank, Trevor J. 2018. "Folklore and the Internet: The Challenge of an Ephemeral Landscape1" Humanities 7, no. 2: 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/h7020050

APA StyleBlank, T. J. (2018). Folklore and the Internet: The Challenge of an Ephemeral Landscape1. Humanities, 7(2), 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/h7020050