Abstract

Through the lens of memetic folk humor, this essay examines the slippery, ephemeral nature of hybridized forms of contemporary digital folklore. In doing so, it is argued that scholars should not be distracted by the breakneck speed in which expressive materials proliferate and then dissipate but should instead focus on the overarching ways that popular culture and current news events infiltrate digital folk culture in the formation of individuals' cultural inventories. The process of transmission and variation that shapes the resulting hybridized folklore requires greater scrutiny and contextualization.

Folklore in the digital age constitutes a complex and, at times, disorienting array of expressive materials. Nevertheless, it appears that we have entered an era of ephemeral digital folk culture in which some genres of folklore and the traditional forms of expressive material they generate (e.g., songs, stories, wordplay and wordsmithery, visual, and narrative humor, etc.) proliferate but often do not always establish a refined, permanent niche within individual repertoires. To be sure, a substantial portion of modern technologically-mediated folklore is comprised of material that follows folkloric form and function, carrying unmistakable evidence of repetition and variation, only to vanish or significantly dissipate after short periods of circulation. This presents a difficult task for folklorists attempting to ascertain the origins or document the evolution of ephemeral digital folk culture, but it also highlights the importance of being on the intellectual frontlines when such phenomena emerge.

As a folklorist and ethnographer specializing in the study of mass media and digital culture, I have often found myself in a perpetual struggle to keep up with the most current iterations of memes and other Internet-derived cultural phenomena. Of course, this is not necessarily due to a lack of effort on my part but, rather, a testament to the ubiquity and fluidity of hybridized modes of vernacular expression. These emergent forms invite the expeditious dissemination of images and stories, instantaneous social commentary, and direct or peripheral engagements with contemporary folk and popular culture across a malleable spread of face-to-face and technologically-mediated communication venues. One notable example comes to mind.

On 31 October 2011, ESPN.com posted an article by Bill Williamson titled “Time for Elway to Think Post-Tebow.”2 The focus of the article was Tim Tebow, the straight-laced starting quarterback for the Denver Broncos, a role he assumed after enjoying a prolific college football career at the University of Florida that launched him into the National Football League as a first-round draft pick. At the time of the article’s publication, however, Tebow was struggling mightily in his transition to professional football, prompting some sports journalists to call for his ouster by the Broncos’ former quarterback (1983–1999) turned Vice President of Football Operations and general manager, John Elway. Nevertheless, Tebow was a media force, attracting copious attention at every turn—whether it was coverage of his inadequate performances on the field, speculation that his future was inevitably doomed (or, conversely, poised for greatness), or commentaries on his penchant for openly professing his Christian faith. Tebow quickly became a household name within popular culture and a polarizing figure within the sports fandom.3 ESPN, the preeminent sports journalism outlet of the time, was especially guilty of saturating their newsfeeds with coverage about every aspect of Tebow’s life and career (see Craggs 2011; Petchesky 2011). Thus, what seemed like another innocuous post about the embattled but fervently popular quarterback quickly morphed into a brutal, fast-paced arena of vernacular expression online. The comments section of the ESPN article became a breeding ground for mocking humor, banter, and counter-hegemonic discourse rallying against ESPN’s institutional authority. It accentuated a keen moment in folkloric expression that lasted in earnest for eight days before slowly evaporating into the digital ether after ESPN, for the most part, successfully intervened to end the spectacle.

The joke formula populating the comments section was simple: “X > Tebow.” What constituted “X” distinguished one joke from another and forum users were able to vote with a thumbs up or thumbs down on posts, acting as a communal barometer of folk approval and appreciation.4 The “Greater Than Tebow” jokes encompassed an array of topics: the nonsensical,5 sexually explicit inferences,6 incorporations of pop culture references7 and existing joke cycles,8 as well as more direct critiques of Tebow’s football acumen and religion9 and jabs at ESPN.10 At the height of the trend, new posts were coming in at a rate of at least one per second, seldom deviating from the X > Tebow formula. Anyone with a registered ESPN.com account could post a comment, which also became a source of contention. As ESPN moderators began the task of deleting new and old posts deriding Tebow, they also began suspending user accounts for “violations of terms and services,” prompting many individuals to perpetually register new accounts in order to continue posting on the site.11

As I have previously noted, the disruption of a community-based website like ESPN.com can serve as “an especially vivacious vernacular experience because the venue suspends the site’s institutional authority while presenting the opportunity for the communal construction of narrative norms and performative expectations” (Blank 2015, p. 290). I happened to stumble across the now-infamous ESPN article on 1 November, 2011, approximately 24 hours after it had initially been posted, upon being alerted to the cultural scene by a colleague.12 I spent the next eight days documenting the jokes that surfaced in the comments section. On the first day, I collected 66 pages of data. On the second day, ESPN.com moderators began to delete posts en masse,13 and several Internet blogs and sports websites began to take notice (Carmichael 2011; Fogarty 2011; Petchesky 2011). On the third day, I collected 97 pages of data. By the fifth day, I collected 161 pages of data. After about a week, the rapid-fire pace of posts began to wane. Within a matter of days thereafter, the “Greater Than Tebow” meme had significantly declined on ESPN.com14 and ultimately moved into the annals of Internet history as a short-lived but potent display of folk power dynamics in a digital setting. However, in that brief window, hundreds if not thousands of people symbolically and performatively fought united against ESPN’s coverage of Tim Tebow and their moderators’ practice of deleting posts and suspending accounts.15 Individuals relied on metafolklore to appropriately craft joke forms and content to meet the expectations established by forum participants, resulting in parodic invocations of concurrent news and popular culture and many self-referential jokes formed in response to other jokes. The context of forum discourse and constraints of the dialogic interface of the ESPN website itself simultaneously acted as a metacommentary on Tim Tebow, ESPN, and the jokes of the forum.16

It could be argued that the transitory nature of this material renders it of less concern for folklorists, but I believe that such a conclusion would be naïve. On the contrary, I submit that ephemeral digital folk culture underscores how individuals construct expressive repertoires, accumulate knowledge and mastery of folkloric forms, and meaningfully engage in vernacular discourse as part of a folk process aimed at quickly parsing through the onslaught of mass mediated information. Moreover, the expressive texts that surface—however briefly—are living archives of a salient moment in folkloric transmission. That being said, I propose that folklorists focus less on capturing every meme or passing singular cultural fad online; in fact, the constant, ever-changing stream of ephemeral digital folk culture makes such an endeavor nearly impossible.17 Instead, folklorists should concern themselves with documenting the major emergent patterns, overarching motifs, and symbolic behaviors of hybridized folklore that manifest online and in face-to-face communication, and they should seek to explicate the influence of mass media and popular culture in expressive interaction.

To illustrate what I mean by “hybrid”, consider an individual who uses a smartphone or some other new media technology to access information about a recent news event. That individual can interchangeably react (or not) to accessing that information by utilizing the online medium in a variety of ways (e.g., posting to social media, emailing peers, text messaging family members, etc.), and/or they can transfer the knowledge of the news and their own individual relationship to the story (e.g., explaining or interpreting what actually took place to others, sharing how/when they first encountered the news, etc.) in a face-to-face setting. The inverse can also occur. In this case, then, corporeality (or lack thereof) does not have an inherent bearing on the authenticity of folkloric interaction and expressive content. I have previously offered the term “virtual corporeality” to refer to “a state in which a user of new media technology becomes so cognitively immersed in their digitally mediated experiences that they perceive them to be just as tangibly ‘real’ as their sense of corporeal embodiment” (Blank 2013b, p. 109). Hybridity speaks to the acknowledgment that new media technologies—participatory media—and their use have been irrevocably inserted into how individuals approach seeking and sharing knowledge in the digital age, especially in the face of significant news events.18 As Robert Glenn Howard explains

While mass-mediated communication technologies have empowered the institutional, participatory media offer powerful new channels through which the vernacular can express its alterity. However, alternate voices do not emerge from these technologies untouched by their means of production. Instead, these communications are amalgamations of institutional and vernacular expression. In this situation, any human expressive behavior that deploys communication technologies suggests a necessary complicity. Insofar as individuals hope to participate in today’s electronically mediated communities, they must deploy the communication technologies that have made those communities possible. In so doing, they participate in creating a telectronic world where mass culture may dominate, but an increasing prevalence of participatory media extends into growing webs of network-based folk culture.(Howard 2008, p. 192)

There is a similar complicity in the deployment of commodified artifacts from popular culture in vernacular expression as they are repurposed in new contexts. Indeed, a central component of hybridized ephemeral digital folklore is the persistent, allusive tie to artifacts from popular culture and the folk connections made to current events or trends in the news as procured through the consumption of mass media. These strong connections to mass media and popular culture emphasize the important role of cultural inventory in contemporary vernacular expression, a key concept in making sense of ephemeral folklore.

Cultural inventory refers to the cognitive index of enduring and resonant elements of folk and popular culture that populate an individual’s expressive repertoire and “the contextual frames of reference we use to reconcile our individual ideas, values, beliefs, and experiences” in relating to the world (Blank 2013a, p. 7; Blank 2016; Malmsheimer 1986).19 It is an individual’s cerebral storehouse of knowledge that compartmentalizes and recalls meaningful symbols in culture and society for easy access. Thus, when encountering traditional folkloric forms online—be it jokes, stories, memes, or some other kind of expressive content in everyday interactions—individuals correlate appropriate analogs from popular culture and knowledge gleaned from mass media in order to process their interactions in context. The subjects of these analogs reveal the imprint of mass and popular culture in digital folklore, which illuminates how such forces permeate into cultural communications and contribute to the fusion of folk and popular culture. The adaptive use of folkloric forms and transmission remain a viable area of study precisely because digital folklore, influenced by the inescapable reach of mass media, evolves alongside popular culture; as a text or artifact from popular culture declines in popularity or retreats from mainstream news coverage, so too does its conspicuous appearance in vernacular expression.

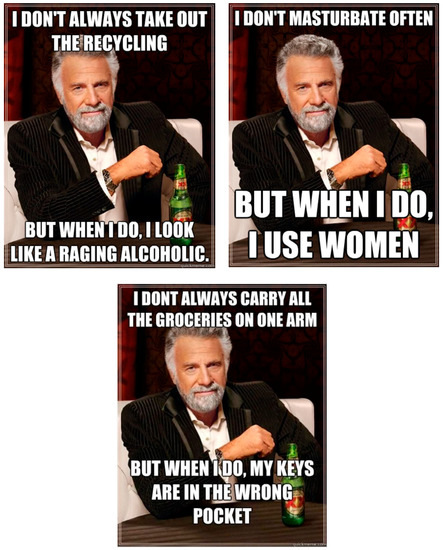

A good example is the “Most Interesting Man in the World” meme, which is drawn from a series of popular Dos Equis beer commercials that ran from 2006 to 2016. In these commercials, the eponymous character, after a series of boastful remarks about his (fictional) grandiose feats, facts, and legendary swagger,20 always declares at the end, “I don’t always drink beer, but when I do, I prefer Dos Equis”, before imploring viewers with the quip, “Stay thirsty, my friends”. The commercial gave way to an image macro template featuring the Most Interesting Man in the World character wherein individuals followed the simple text formula of “I don’t always X, but when I do, Y” to create literally thousands of variations of the humorous image, shared prominently throughout the Internet (Figure 1). This took off in 2009, peaking in popularity between 2010 and 2012, before slowly beginning to decline after 2016.21

Figure 1.

Some representative examples of the “Most Interesting Man in the World” meme.22

The success of the joke is predicated on individuals recognizing not only the Most Interesting Man in the World character but also the constructs of the Dos Equis commercials themselves.23 The X-Y formula keys the interactive humor frame and points to multiple existence and variation of the source materials. This also falls under the umbrella of what Michael Dylan Foster calls the folkloresque or “popular culture’s own (emic) perception and performance of folklore” (Foster 2015, p. 5), another area in need of deeper folkloristic inquiry.24

At first blush, the examples of Tim Tebow and Dos Equis inspired memes perhaps do not appear to pass muster as subjects of serious study. However, as folklorists are consumed with the task of studying the everyday, it bears noting that folklore studies, as an intrinsically humanistic discipline, stands to gain as much, if not more, from holding its unique stead as a student of the human experience, past and (especially) present. As William A. Wilson so eloquently states:

no other discipline is more concerned with linking us to the cultural heritage from the past than is folklore; no other discipline is more concerned with revealing the interrelationships of different cultural expressions than is folklore; and no other discipline is more concerned, or no other discipline should be more concerned, with discovering what it means to be human. It is this attempt to discover the basis of our common humanity, the imperatives of our human existence, that puts folklore study at the very center of humanistic study.(Wilson 1988, pp. 157–58)

It is imperative that we recognize that while the cultural milieu undergoes recalibration at a breakneck pace, the traditional genres and expressive dynamics long chronicled by folklorists continue to thrive in hybridized expressive materials. By looking at the bigger picture within vernacular discourse instead of just the minutiae, folklorists can better see the forest from the trees. In short, the challenge of studying folklore and the Internet today stems not from the ephemeral landscape but from the necessity to acknowledge the ways that technologically-mediated communications complicate, amalgamate, and inculcate everyday practices across virtual and corporeal venues. By accounting for cultural inventory, hybridity, and the influence of mass media and popular culture on expressive repertoires, we can begin to mindfully grasp the complex dynamics of human interaction that manifest online.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Blank, Trevor J., ed. 2009. Folklore and the Internet: Vernacular Expression in a Digital World. Logan: Utah State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Blank, Trevor J., ed. 2012. Folk Culture in the Digital Age: The Emergent Dynamics of Human Interaction. Logan: Utah State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Blank, Trevor J. 2013a. The Last Laugh: Folk Humor, Celebrity Culture, and Mass-Mediated Disasters in the Digital Age. Folklore Studies in a Multicultural World Series; Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. [Google Scholar]

- Blank, Trevor J. 2013b. Hybridizing Folk Culture: Toward a Theory of New Media and Vernacular Discourse. Western Folklore 72: 105–30. [Google Scholar]

- Blank, Trevor J. 2015. Faux Your Entertainment: Amazon.com Product Reviews as a Locus of Digital Performance. Journal of American Folklore 128: 286–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blank, Trevor J. 2016. Giving the “Big Ten” a Whole New Meaning: Tasteless Humor and the Response to the Penn State Sexual Abuse Scandal. In The Folkloresque: Reframing Folklore in a Popular Culture World. Edited by Michael Dylan Foster and Jeffrey A. Tolbert. Boulder: Utah State University Press, pp. 147–72. [Google Scholar]

- Bronner, Simon J. 2009. Digitizing and Virtualizing Folklore. In Folklore and the Internet: Vernacular Expression in a Digital World. Edited by Trevor J. Blank. Logan: Utah State University Press, pp. 21–66. [Google Scholar]

- Buccitelli, Anthony Bak. 2012. Performance 2.0: Observations toward a Theory of the Digital Performance of Folklore. In Folk Culture in the Digital Age: The Emergent Dynamics of Human Interaction. Edited by Trevor J. Blank. Logan: Utah State University Press, pp. 60–84. [Google Scholar]

- Carmichael, Emma. 2011. This Is What Happens When ESPN.com Attempts to Fight Back. Deadspin. November 2. Available online: http://deadspin.com/5855836/this-is-what-happens-when-espncom-attempts-to-fight-back (accessed on 5 November 2011).

- Caughey, John L. 1984. Imaginary Social Worlds: A Cultural Approach. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. [Google Scholar]

- Craggs, Tommy. 2011. The Stupid Moral Panic over Mocking Tim Tebow; Or, What Would Jesus Do about Tebowing? Deadspin. November 4. Available online: http://deadspin.com/5856237/the-stupid-moral-panic-over-mocking-tim-tebow-or-what-would-jesus-do-about-tebowing (accessed on 5 November 2011).

- Davies, Christie. 1999. Jokes on the Death of Diana. In The Mourning for Diana. Edited by Tony Walter. New York: Berg, pp. 253–68. [Google Scholar]

- Dundes, Alan. 1966. Metafolklore and Oral Literary Criticism. The Monist 50: 505–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogarty, Dan. 2011. ESPN.com Comment Thread Descends into Chaos Because of Tim Tebow’s Lackluster Play. Sportsgrid.com. November 1. Available online: http://www.sportsgrid.com/real-sports/nfl/greater-than-tebow/ (accessed on 3 November 2011).

- Foster, Michael Dylan. 2016. Introduction: The Challenge of the Folkloresque. In The Folkloresque: Reframing Folklore in a Popular Culture World. Edited by Michael Dylan Foster and Jeffrey A. Tolbert. Boulder: Utah State University Press, pp. 3–36. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, Michael Dylan, and Jeffrey A. Tolbert, eds. 2016. The Folkloresque: Reframing Folklore in a Popular Culture World. Boulder: Utah State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, Robert Glenn. 2005. Toward a Theory of the World Wide Web Vernacular: The Case for Pet Cloning. Journal of Folklore Research 42: 323–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, Robert Glenn. 2008. Electronic Hybridity: The Persistent Processes of the Vernacular Web. Journal of American Folklore 121: 192–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, Jeana. 2016. #FolkloreThursday: Digital Folklore & Internet Folklore. Patheos. March 31. Available online: http://www.patheos.com/blogs/foxyfolklorist/folklorethursday-digital-folklore-internet-folklore/ (accessed on 25 January 2017).

- Kapchan, Deborah A., and Pauline Turner Strong. 1999. Theorizing the Hybrid. Journal of American Folklore 112: 239–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, Merrill. 2013. Curation and Tradition on Web 2.0. In Tradition in the Twenty-First Century: Locating the Role of the Past in the Present. Edited by Trevor J. Blank and Robert Glenn Howard. Logan: Utah State University Press, pp. 123–48. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley, Greg. 2016. “The Joke’s On Us”: An Analysis of Metahumor. In The Folkloresque: Reframing Folklore in a Popular Culture World. Edited by Michael Dylan Foster and Jeffrey A. Tolbert. Boulder: Utah State University Press, pp. 205–20. [Google Scholar]

- Malmsheimer, Lonna M. 1986. Three Mile Island: Fact, Frame, and Fiction. American Quarterly 38: 35–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeill, Lynne S. 2015. “The Internet is Weird”: Folkloristics in the Digital Age. Folklore Fellows Network 47: 12–13, 16–17. [Google Scholar]

- Oring, Elliott. 2008. Engaging Humor. Champaign: University of Illinois Press. First published 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Petchesky, Barry. 2011. How Contempt for Tim Tebow Caused an ESPN.com Commenter Revolution. Deadspin. November 2. Available online: http://deadspin.com/5855575/how-contempt-for-tim-tebow-caused-an-espncom-commenter-revolution (accessed on 5 November 2011).

- Stross, Brian. 1999. The Hybrid Metaphor: From Biology to Culture. Journal of American Folklore 112: 254–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, William A. 1988. The Deeper Necessity: Folklore and the Humanities. Journal of American Folklore 101: 156–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | An earlier version of this paper was presented as “Authoring and Curating Meaning in the Digital Age: Ethnographic Considerations for Documenting Hybridity, Cultural Inventory, and Performative Vernacular Expression” at the Folklore Fellows’ Summer School 2015, Doing Folkloristics in the Digital Age, 15 June 2015, in Seili, Finland. My deepest thanks to the FFSS coordinators and summer school attendees whose feedback and engagement with the lecture provided incredibly thoughtful and adept suggestions for strengthening my argumentation and organization. |

| 2 | A stable URL hosting the article can be found at http://www.espn.com/blog/afcwest/post/_/id/34680/time-for-elway-to-think-post-tebow. |

| 3 | By October 2011, Tebow’s popularity was so ubiquitous that his practice of kneeling down on one knee to pray after completing a touchdown inspired the meme known as “Tebowing” (a variant of “planking”) in which individuals posed in the kneeling prayer position in pictures and posted them on the Internet. See http://knowyourmeme.com/memes/tebowing for more information on the Tebowing meme. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Planking_(fad) for a folk moderated write-up on the planking meme that served as a pretext to “Tebowing”. |

| 4 | As more X > Tebow jokes appeared, “a corpus of their general characteristics [were] cognitively registered by readers”, with the characteristics serving as “contextual cues for recognizing and interpreting these communication events as expressive performances” (Blank 2015, p. 290). The top-ranked comment was “Knock knock?…. Who’s there?…. Doesn’t matter, it’s > Tebow.” [Collected 4 November 2011] Some commenters acknowledged the rating system’s implicit bias and folk manipulation: “trying to find my post so I can see if anyone likes it, thereby confirming to myself that I really am witty > Tebow” and “Liking your own post > Tebow”, which was followed by the original poster with “Replying to your own post > Tebow.” [Collected 3 November 2011] See Blank (2015, pp. 289–92) for a discussion on how individuals utilize and/or play with a website’s rating system for humorous and counter-hegemonic purposes. |

| 5 | For example, “Legally marrying a McRib sandwich > Tebow”, “Eating your kids > Tebow”, and “Coke-Boogers > Tebow.” [Collected 1 November 2011]. |

| 6 | Examples include “making eye contact with a 40-year-old man while he’s eating a banana > Tebow” and “That awkward moment when my doctor is checking my balls during a physical and I run my fingers through his hair > Tebow.” [Collected 4 November 2011]. |

| 7 | One popular thread made explicit reference to the 1990 computer game, The Oregon Trail: Getting Scurvy on Oregon trail > Tebow ↳ Getting dysentery on Oregon Trail > Tebow ↳ Trying to ford the river instead of caulking the wagon > Tebow ↳ Getting robbed by Indians in Oregon Trail > Tebow ↳ Wasting all your bullets on a squirrel and then seeing a bear run by > Tebow These comments show a keen awareness of not only the game but folk knowledge surrounding strategies for succeeding within it, as well as common pitfalls players experienced and other uniting factors that helped coalesce the thread in a united humor front. Each of the posts in the thread were made by different individuals. [Collected 5 November 2011]. |

| 8 | Examples include “Michael Jackson calling Boyz II Men because he thought it was a delivery service > Tebow”—a derivative of a joke I collected around the time of Jackson’s death in 2009 (see Blank 2013a, pp. 83–98)—and “Calling Shotgun in Princess Diana’s car > Tebow”—a play on the jokes surrounding Princess Diana’s death in 1997 (Blank 2013b, pp. 40, 125n7; see also Davies 1999). Others tapped into their cultural inventories (Blank 2013a, 2016; Malmsheimer 1986) to make humorous remarks. For example, calling upon knowledge about the actor’s Parkinson’s diagnosis, “Michael J. Fox’s Etch-A-Sketch drawings > Tebow” and “Yelling the N word at a DMX [a black gangsta rapper] concert > Tebow.” [Collected 6 November 2011]. |

| 9 | Representative examples include “Tebow calling third-downs ‘Muslims’ because they’re so hard to convert > Tebow” and “Buying a player’s jersey because he has the same imaginary friend as you > Tebow” [Collected 3 November 2011]. |

| 10 | For example, “Bill Williamson [ESPN article author] getting an E-mail notification after each comment on his blog post > Tebow” and “Being part of the first ESPN thread that hits 1,000,000 posts > Tebow”, an acknowledgment of both the community atmosphere and meta-awareness of the thread’s potency. [Collected 1 November 2011]. |

| 11 | One popular joke posted read “having more espn accounts than tebow has [pass] completions > Tebow” [Collected 3 November 2011, right at the height of ESPN’s initial effort to delete posts and suspend user accounts]. This joke relies on the folk knowledge that an ESPN.com account is required to post to the comments section while also highlighting the defiance of commenters intent on disrupting both the ESPN article’s comment section and mocking Tim Tebow all at once. |

| 12 | My thanks to David J. Puglia for drawing my initial attention to the “Greater Than Tebow” thread. |

| 13 | Importantly, moderators did temporarily retreat for a day on 2 November, 2011 after it was obvious that too many commenters were overwhelming their servers. This was seen as a major victory for commenters (see Carmichael 2011; Fogarty 2011). ESPN.com moderators revamped their approach beginning 3 November, 2011 and began suspending accounts in addition to deleting posts. |

| 14 | It is important to note, however, that the meme did periodically appear on non-ESPN websites, including Deadspin and Fark.com, to name a few, although the phenomenon was most nascent on ESPN.com, where the meme originated. Additionally, there were instances of people bringing “> Tebow” signs to football games in the days following the article’s publication, which also points to the hybridity of the phenomenon. |

| 15 | See Blank (2015) and Buccitelli (2012) for supplementary information on the performative nature of digital communication and Kaplan (2013) on digital curatorship. |

| 16 | As Greg Kelley (2016) observes, the comic value of a joke often depends upon an audience’s awareness of the joke’s antecedent for successful deployment (see also Oring [2003] 2008, p. 56). This was certainly the case with the “Greater Than Tebow” jokes that I collected from 1 November to 9 November, 2011. See also Blank (2016) and Dundes (1966, p. 510) on metafolklore and its applications to joke formulas and Foster and Tolbert (2016) for more comprehensive analyses of the intersections of folklore and popular culture. |

| 17 | Indeed, the sometimes slow pace of the academic publication process makes it difficult to document and analyze cultural phenomena synchronously. Also, as Michael Dylan Foster notes, there is often “a time lag between the professional world and the popular culture world, between academic inception and vernacular reception” (Foster 2015, p. 17). |

| 18 | See Blank (2009, 2012, 2013a); Bronner (2009); Howard (2005); Jorgensen (2016); and McNeill (2015). For additional readings on folklore and hybridity, see Blank (2013b, 2015); Kapchan and Strong (1999); Stross (1999); and especially Howard (2008). |

| 19 | Although penned before the advent of the World Wide Web and new media technologies, anthropologist John L. Caughey (1984) has thoughtfully used the term “imaginary social worlds” to differentiate between individuals’ face-to-face interactions and “artificial” social planes derived from interactions with television, radio, movies, books, magazines, and newspapers. My conceptualization of cultural inventory has assuredly been influenced by Caughey’s work. See also Malmsheimer (1986, pp. 36–37). |

| 20 | For example, a narrator reads line such as “In a past life, he was himself”, “He can slam a revolving door”, “If opportunity knocks and he’s not home, opportunity waits”, and “He gave his father ‘the talk’”. These overtures are reminiscent of “Chuck Norris” jokes that popularly circulated in oral and digital repertoires in the early twenty-first century. My thanks to the peer reviewer of this piece for drawing attention to this connection. |

| 21 | The Google Trends analytics chart, showing the chronological search popularity for the Most Interesting Man in the World in Google’s recorded history, can be found at https://trends.google.com/trends/explore?date=all&q=most%20interesting%20man%20in%20the%20world. The data also shows that search queries took place predominantly in North America, which makes sense given the Dos Equis brand’s marketing efforts on the continent. |

| 22 | See http://knowyourmeme.com/memes/the-most-interesting-man-in-the-world for additional information on the meme, as well as more examples of variations collected. |

| 23 | This is reminiscent of Simon J. Bronner’s cataloging of Budweiser pun jokes after the suicide of Pennsylvania politician R. Budd Dwyer (Bronner 2009, pp. 46–47, 49). |

| 24 | See Foster and Tolbert (2016) for a more extensive treatment of the folkloresque. |

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).