1. Introduction

Platforms enable and limit how we tell stories and the stories we can tell. The Extended Digital Narrative (XDN) research project, led by Scott Rettberg at the Center for Digital Narrative at the University of Bergen, Norway, explores emerging forms of digital storytelling. We analyze the constraints and affordances of emerging technological environments, considering the potentialities of new writing practices to enable literary or multimodal genres of storytelling by mapping historical narrative experiments and by creating our own.

Our work is framed conceptually by its focus on algorithmic narrativity, the combination of the human ability to understand experience through narrative with the power of the computer to process and generate data (

Rettberg and Walker Rettberg 2025). Delineating methods, establishing processes, and testing the narrative capacities of new platforms and modalities of expression are core parts of our group’s work. In this essay, the core members of the team contribute descriptions of their practice-based research projects, spanning AI chatbots, AI text-to-image generation, AI cinema, AI character development in games, and virtual reality, with an emphasis on the ways that making creative work in these new environments is not only an end in itself, but of a mode of engagement essential to the development of critical insights into how AI and Extended Reality platforms can and will shape and be shaped by human narrative capacities now and in the future.

The works we discuss here include narratives produced using new artificial intelligence and virtual reality platforms. Emergent definitions of artificial intelligence, virtual reality, and platforms frame our analysis. Taken together, these perspectives guide our inquiry into how AI and platforms shape the creative and critical possibilities of digital narrative environments.

The EU Artificial Intelligence Act defines an AI system as “a machine-based system that is designed to operate with varying levels of autonomy and that may exhibit adaptiveness after deployment, and that, for explicit or implicit objectives, infers, from the input it receives, how to generate outputs such as predictions, content, recommendations, or decisions that can influence physical or virtual environments” (

European Union 2024, art. 3(1)). However, no single definition fully captures the scope of AI. Broad accounts that equate AI with algorithms risk being overly inclusive, while strict definitions that require human-like intelligence exclude most current applications, and narrow task-based approaches remain partial and ambiguous (see:

Sheikh et al. 2023, pp. 15–20).

Virtual Reality (VR) is part of a broad terminology that includes different virtualities, known as Extended Reality (XR), where X represents the various variables, both present and future, that enable interaction with real and virtual environments through wearables (

LaValle 2020;

Reis 2021;

Roxo 2023b). Currently, there is Augmented Reality (AR) which overlays the real environment through a smartphone; Mixed Reality (MR), using a Head-Mounted Display (HMD), a wearable that provides a deeper AR experience; and the most recognizable, Virtual Reality (VR), which at the other end of the spectrum uses HMDs to block out the real world and immerse the user in a virtual environment.

The concept of platform is similarly multifaceted. Platforms are understood both technically as infrastructures and online environments that support the design, use, and deployment of applications (

Gillespie 2010, p. 349) and discursively as intermediaries that present themselves as neutral while exercising significant economic, infrastructural, and cultural power (

Gillespie 2010;

Nieborg and Poell 2018).

These XDN case studies of narrative projects provide indications of how generative AI and virtual and augmented reality may impact storytelling in different cultural and institutional contexts. Lina Harder’s Hedy Lamarr Chatbot is a prototype developed for her research on histobots, GenAI-driven chatbots that combine education and entertainment into edutainment for contexts such as museums and online platforms. Scott Rettberg’s Republicans in Love is a foray into political satire, using text-to-image generation to critique contemporary Trumpism. David Jhave Johnston’s Messages to Humanity uses Runway’s Act-One to investigate solo rapid micro-video production. Haoyuan Tang’s project Integrating Large Language Models into Video Game Narratives explores the use of generative AI to produce responsive dialogs with non-player characters in computer games. Sérgio Galvão Roxo Her Name Was Gisberta expands on immersive storytelling as a tool of social education against Transphobia through Virtual Reality. We understand these projects both as experiments in the scientific sense, intended to test hypotheses about the narrative affordances of the platforms used to develop them, and as aesthetic experiences, which can be experienced as expressive narratives in their own right.

Apart from the specific research insights we offer in each of our case studies, we are making a more general argument about the importance of practice-based and artistic research to the humanities. It may seem obvious to researchers in specialized fields such as electronic literature or media studies that this type of research has intrinsic value, but we can offer at least two anecdotal cases from our own experience that this is an argument that bears further evidence and reiteration. When Scott Rettberg was reviewed for promotion to full professor about a decade ago, an external expert committee reviewed both his theoretical and creative research, in keeping with the terms under which he was originally hired. However, when the report was received by the humanities faculty board, they decided to send the report back to the committee, asking that they review only the critical publications. Thankfully, the committee elected to recommend promotion on that basis. But it is notable that a generalist humanist faculty chose to exclude an expert committee’s evaluation on the basis of the inclusion of creative work. More recently, Sérgio Galvão Roxo was awarded a PhD fellowship in media production for a creative VR project. As he began his work, he was told that his creative work would not be assessed for the PhD alongside his theoretical publications. We believe that it as urgent now as ever to provide evidence that practice-based and artistic research is essential to many contemporary humanities fields and should be assessed as such.

2. Lina Harder’s Hedy Lamarr Histobot

Interactive narrative has come a long way since

ELIZA, Joseph Weizenbaum’s 1960s chatbot that parodied a psychotherapist (

Weizenbaum 2003), and

TINYMUD (

Mauldin 1994, p. 16), where a computer-controlled “Chatter Bot”-player hinted at conversational artificial intelligence (AI) in text-based virtual worlds (

Al-Amin et al. 2024, p. 9). Until the launch of ChatGPT ushered in what has been termed an “AI spring on steroids” (

Rudolph et al. 2023, p. 364), the idea of holding a meaningful conversation with a machine seemed closer to fantasy than fact. Fictional sentient AIs like HAL 9000 in

2001: A Space Odyssey (

Kubrick 1968), AM in

I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream (

Ellison 1967), and Wintermute in

Neuromancer (

Gibson 1984) did not chat innocently. They manipulated, tortured and killed. These imaginaries framed conversations with AI-machines as dangerous.

Today, large language models (LLMs) like OpenAI’s GPTs power the creation of chatbots and avatars that simulate humans, including approximations of historical figures. I call these

histobots: conversational agents driven by generative AI that re-enact persons of historical record for edutainment purposes (first used at a presentation,

Harder 2024b; also used in other contexts, e.g., for an automatic question-generation system,

Pranav and Prasad V R 2023). Unlike their sci-fi predecessors,

histobots are marketed as safe, accessible, and even educational, while still carrying traces of the fictions and projections that preceded them. Museums, companies, and individual users now deploy such tools in exhibitions, classrooms, and apps. Their marketing often trades in anthropomorphic or even quasi-religious rhetoric: “Always Wanted to Ask Salvador Dalí a Question? Now You Can Through the Magic of A.I.” (

Artnet News 2024); “Have in-depth conversations with history’s greatest” (Hello History,

FACING IT International AB 2023). I try to resist such framings. For me,

histobots are tools, not autonomous actors.

The producers of

histobots attempt to create experiences that appear authentic but lack an original referent. They stitch selected data fragments into copies of copies with no source. Baudrillard would call them

simulacra, signs that generate

hyperreality, a “real without origin” (

Baudrillard 1994, p. 3). Their forms vary:

Bonjour Vincent (

Musée d’Orsay 2023),

Ask Dalí (

Salvador Dalí Museum 2024), and

Chat with Natalie (

Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute and OpenAI 2024) serve heritage purposes as avatars, voice-clones, or simpler chatbots in museums. Various historical characters on

Hello History (

FACING IT International AB 2023) and

Khanmigo (

Khan Academy 2023) promise educational support.

Virtually Parkinson (

Night Train Digital 2025) interviews real-world celebrities on ‘his’ podcast,

Agatha Christie teaches

On Writing (

BBC Maestro and Agatha Christie Ltd. 2025), and users generate their own

histobots for role-play purposes on

character.ai (

Character Technologies, Inc. 2024) in a more

fanbot (

Ask 2025) type of approach. More speculative variants include

The Infinite Conversation (

Miceli 2022) between Werner Herzog and Slavoj Žižek, and

Manifesto for Future AIs (

Nobody & The Computer 2025), which is delivered in the guise of historical figures.

To probe their conditions, I franken-coded (

Cat 2018)—piecing together code from YouTube and forums—and vibe-coded (

Karpathy 2025)—relying on ChatGPT 3.5 Turbo, trial, and intuition—a

histobot myself.

2.1. Darling, I’m a Histobot Now

In autumn 2024, I tested my bilingual

Hedy Lamarr Chatbot prototype (

Harder 2024a) (

Figure 1) at

More Than Meets AI (

O’Kane et al. 2024), an exhibition at the

Center for Digital Narrative in Bergen, Norway. Visitors entered a 1951 Hollywood café chatroom and could converse in German or English with “Hedy”, who replied as the Austrian-American actress and inventor might have at the time. Each session lasted five minutes, but could be ended early or extended.

The Hedy Lamarr Chatbot was explicitly a prototype: an experiential artifact not designed for mass deployment but to test the conditions under which a generative system might perform a historical persona. In hindsight, it was about complicity: what it means for a researcher to design with and within generative systems while critiquing them.

I chose Lamarr because her life combines celebrity, science, and gender politics. She was celebrated for her acting, but her role in developing frequency-hopping technology went unacknowledged until late in her life and only recently entered the cultural

Zeitgeist (see: Documentary “Bombshell”,

Dean 2017). I believe her legacy represents what

Gitelman (

2006, p. 12) calls the “data of culture”: the records and fragments through which modern culture becomes archivable and narratable. I placed Lamarr within an AI-mediated performance, which exposed the biases of remembrance and revealed my complicity as a researcher. In constructing the prototype, I participated in the very processes that reduced her biography to prompts and probabilistic text.

2.2. The Platform Made Me Do It

The Lamarr chatbot ran on a Flask server. Users’ text inputs were sent to the

GPT-4o mini model (

OpenAI 2024) with lightweight memory. Sixty-four prompts encoded Lamarr’s biography, inventions, quotes, and tone. These were refined iteratively until the exhibition. A backend filter blocked certain swearwords.

The system produced fluid, plausible dialogue, yet the platform’s affordances and constraints shaped every output. The model slipped into “GPTisms” (coined by

Upmias 2023; employed in its current meaning by

Gibbs 2023), used flowery language or even fully hallucinated details that contradicted the factually researched prompts. What emerged was not Lamarr but a curated, sanitized “GPT-Hedy”. After their interaction, visitors could give feedback on “Hedy” through a questionnaire. The feedback confirmed the unevenness. Some praised the charm of the persona, like the use of “darling”. Others criticized shallow content, repetition, or anachronisms, such as smartphone references. The bot was supposed to be set in 1951 after all.

Baudrillard’s reading of Borges’s fable of the map shows that representation once mirrored reality but now produces it, leaving only fragments of the real (

Baudrillard 1994, p. 3). The Mercator projection illustrates this, as does the Lamarr chatbot. The Mercator map, created in 1569 for navigation, shows Africa as the size of Greenland, though Africa is fourteen times larger. A distortion that fixed colonial hierarchies and still shapes perception, education, and policy today (

Archie 2025). Like many chatbots based on similar models, the Lamarr chatbot risked a similar effect. It relied on extraction and partial sources, stood in legal gray zones over whether the re-enactment of her character was allowed, and reflected structural industry limits of corporate control, privilege, and gender imbalance. It showed systemic bias in models through training data, corporate alignment, and reinforcement learning. It carried epistemic limits, reproduced archival silences and dominant historiographies that marginalize women, queer figures, and people of color. It drew on platformed bias (also see:

Benjamin 2019;

Noble 2020), likely from sources such as Wikipedia and Wikidata (see:

Luyt 2011;

McDowell 2024;

Robb 2024), and other broken citation trails. It fell into historical negationism, where voices are turned generic. Like the Mercator map, I presented the Lamarr Chatbot as rescaled: a life reduced to 64 prompts instead of 85 years of living, a life I never knew.

2.3. The Ephemeral That Endures

LLMs operate probabilistically. They predict likely continuations based on statistical patterns.

Chun (

2011) describes software as “the enduring ephemeral” (p. 128): media that promises permanence through repetition, yet is inherently fragile and unstable. Digital media is “not always there (accessible), even when it is (somewhere)” (p. 95); it is forgetful, erasable, and prone to disappearance. Its claim to permanence rests on constant regeneration, yet this process ensures obsolescence. Chun’s paradox fits LLMs. The biographies, voices, or characters that appear to endure fade with each update, as digital memory preserves itself only by erasing itself (p. 137). The constraints are infrastructural as much as technical. OpenAI’s API determines cost, latency, moderation filters, and access. Prompt engineering is labor-intensive and unstable across model versions. Platform dependence makes long-term preservation difficult: a prototype that works in 2024 may become obsolete when models are updated or APIs withdrawn.

A comparison with

Marbles of Remembrance (

de Araújo et al. 2018) shows the trade-offs of non-AI design. The Arolsen Archives and fabular.ai built the project on records from the

International Tracing Service (ITS) to tell the stories of Jewish children persecuted under the Nazi regime. Users could query biographies, retrieve registration cards, dates, addresses, and family links, and follow location-based tours tied to

Stolpersteine memorials in Berlin, Germany; small brass-plated concrete blocks set into pavements to mark the last freely chosen residence of victims of Nazi persecution across Europe (see:

STOLPERSTEINE and Demning 2025). The bot’s three main functions included open questions, guided tours, and GPS notifications about nearby

Stolpersteine. Technically, the chatbot ran on the APIs of the messaging app

Telegram for communication. Queries were analyzed, routed through

Google Dialogflow, and matched against a structured knowledge model. Stories were modelled through Person, Act, Location, Narrative, Speech, and Media, linking text, images, audio, and GPS metadata into coherent guided-tour narratives.

Unlike my Lamarr prototype, every response in

Marbles was predetermined and tied to archival sources. The system prioritized accuracy and traceability, but sacrificed flexibility and conversational fluency. Yet platform dependence shaped outcomes here, too. When

Telegram became associated with extremist groups, the project was withdrawn and relaunched on the

berlinHistory app (

Arolsen Archives 2021). Both

Marbles and the Lamarr chatbot demonstrate that platforms are not neutral stages for content. As

Tarleton Gillespie (

2010) argued, platforms present themselves as neutral and “open to all,” but in practice they perform different roles for users, advertisers, partners, and policymakers (pp. 348–50), while also shaping what circulates and how.

2.4. Built to Think It Through

The Lamarr chatbot shows that

histobots are not vessels that “bring the past to life” as producers of the app

Hello History (

FACING IT International AB 2023) claim, but performances shaped by infrastructure, prompts, and platforms. The question is less

can this be built? than

what does it mean that it works in this way, under these conditions?Schechner and Turner (

1989) notion of “restored behavior” as “the making and manipulating of strips of behavior” (p. 33) captures the logic of

histobots. Like theatre, they reassemble existing frames and retell familiar stories, though digitally, and shaped by training data, moderation filters, and platform design. Marvin Carlson calls theatre a haunted human cultural structure (

Carlson 2008, p. 2) that recycles “past perceptions and experience in imaginary configurations […] powerfully haunted by a sense of repetition […]” (p. 3).

Histobots, too, stage this haunting but through algorithms rather than actors.

White and Roth (

2014) claim that history is constructed through narrative

emplotment, the process of turning sequences of past events into stories through the use of familiar literary structures such as tragedy, comedy, romance, or satire. These archetypal plots give coherence and meaning to otherwise disparate facts, framing them in ways that convey an implicit ideology and convention of narrative.

Histobots, or more precisely their creators, reproduce this process: In the Musée d’Orsay Van Gogh is the tragic, misunderstood genius. And I cast Lamarr as the forgotten woman inventor. History, as stated by

White and Roth (

2014), and

histobots are as much literary production as science. Their authority depends less on objectivity than on the recognizable, persuasive power of their storytelling form.

Attributions of authorship also change.

Barthes (

1986) argued that “writing is the destruction of every voice, every origin […] where all identity is lost, beginning with the very identity of the body that writes” (p. 45) and that “life merely imitates the book, and this book itself is but a tissue of signs, endless imitation, infinitely postponed” (p. 53). Foucault likewise notes that not all texts historically required an author (

Foucault 1993).

Histobots exemplify this condition. Their ‘speech’ has no stable origin. It emerges from prompts, datasets, platform architectures, and user inputs rather than a singular authorial voice.

2.5. The Silence That Speaks

Histobots are not encounters with “the past,” no matter the marketing claims. At best, they serve as probes. They reveal how storytelling bends when authored by algorithms, how platforms curate cultural memory, and how histories of yesterday and fantasies of tomorrow become entangled in infrastructures beyond our control. To build is to research, and research with AI means accepting complicity. We are critics and co-authors at once, shaped by and shaping the systems we study. This entanglement is not a weakness of practice-based inquiry but its strength. The danger is no longer the homicidal AIs of scifi’s past, but the seduction of plausibility, the repetition of bias, the ease with which performance masquerades as memory. To build a

histobot is to join the masquerade while tugging at the curtain, and ideally to listen to the echo from the margins. Think of Weizenbaum’s secretary who asked to be left alone with

ELIZA (

Weizenbaum 2003, p. 370). We know her, if she even existed, as his secretary, named for him rather than herself, her authorship clipped into his anecdote (see:

Berry and Ciston 2024;

Roach 2024). The effect survives; the speaker does not. That is the lesson I take from my experiment and the archive. AI’s history still arrives under another’s name, its silences as instructive as its outputs.

3. Scott Rettberg’s Republicans in Love

Republicans in Love (2022–2023) is both a text-to-image generation experiment and a narrative of contemporary politics. It is a foray into political satire, using text-to-image generation and text-to-video generation. It has now had two iterations, one produced during the months following the November 2022 United States Congressional election, which tracks the rise of right wing Trumpism. The second part of the project, Republicans in Love, Episode II: A New Cope (2025) is focused on the initial period of Donald Trump’s second presidential administration.

Both iterations of this project are experiments in cyborg authorship, that is, the idea that storytelling with generative AI is ontologically different from traditional forms of writing because both human intelligence and advanced computational processes contribute to the creation of the narrative experience. (

Aarseth 1997;

Rettberg 2023a) It is not the case that when we write with AI we are writing with an

other in the sense of co-authoring with another consciousness. However, we can understand AI engines to be active non-human cognizers, as they are processing data algorithmically in a way that produces meaning (

Hayles 2017). Emphasizing the relationship between the written text and the images that result, the collection of approximately 100 text and image pairs in

Republicans in Love serve as an experiment in using this environment of human and machine cognition to produce a sustained and recognizably literary work.

3.1. Text-to-Image Generation as a Form of Writing

Rather than being a collaboration with an AI chatbot,

Republicans in Love only makes use of human writing which is then fed to either a text-to-image generation engine (in the first iteration of the project OpenAI’s DALL•E 2, and in the second DALL•E 3) or a text-to-video generation engine (Runway). From the standpoint of fiction writing, conversational interactions with AI chatbots are not exceptionally transformative: human prompts trigger responses from the LLM, but do not produce outputs that a human author would not be capable of. Typing a written prompt into a text-to-image generation engine and getting a radically transcoded (see

Manovich 2001) response that is an entirely different form of media back, however, materializes an entirely new form of writing.

The first iteration of

Republicans in Love integrates elements of art history, politics, and social media discourse while also serving as a case study in the capabilities and limitations of the DALL•E platform, and perhaps text-to-image generation in general.

Republicans in Love consists of pairs of one-line texts (prompts) and the images that result from them. These pairs revisit historical incidents, ironies, and dangers of contemporary Trumpist populism. The project also traverses the history of European and American visual art through the manifestation of the styles of artists specified in the prompts. The project has resulted in an artist’s book, a social media game show, a set of playing cards and exhibitions of videos (

Rettberg 2023b) and prints on canvas from the project.

How should we understand the function and ontological status of text-to-image generative AI? While some fear that these systems are a threat to writers, artists, and designers, I argue that AI-based text-to-image generation systems should be understood as writing environments (

Rettberg 2025). The human writer engages with the nonconscious cognitive system of the AI, which accesses incredibly vast datasets of human language and imagery. The system attempts to draw correlations between the language supplied by the user, approximations of where those language elements might meet in the latent space of its language dataset. The corresponding image includes elements that are conceptual approximations of the language provided. For example, the prompt such as “Republicans in love, angry about the news, eating greasy cheeseburgers at the President’s desk in the Oval Office, in the style of Caravaggio.” (

Figure 2) yields a picture that blends together many of the elements provided (in a way that may or may not be coherent).

3.2. The Aesthetics of Prompt & Image as Literary Dyad

There are many different ways of interpreting what text-to-image generators are actually doing from an aesthetic perspective, and what writing with them actually entails. Relegating the interaction between human cognition, writing, machine cognition, and image production to the status of an artist’s software “tool” would be reductive. Rather than conceptualizing this process as akin to that of producing working with an image editing program, we should understand it as an environment for the literary production of visual narrative.

What kind of writing is a text-to-image prompt? Certainly not a chapter of a novel or a flash fiction. It might have more in common with an aphorism, or a one-line joke, or perhaps a Fluxus score, which may be read on its own, but always results in a different performance when enacted. A prompt is a speech act: typing the prompt and hitting the return key triggers an algorithmic process that results in non-trivial computation: an act of creativity that is neither entirely human-directed nor purely machine-determined. The system is a complex probability calculator, a hermeneutic reader, and a narrative collage artist. It adapts whatever text it is given into multiheaded attention across its vectors, averaging its statistical contextual interpretation of each word into a position within labeled images in its latent space, and then estimating how those elements could cohere and be framed together. It is, however, important to note that although this positioning is statistical, it is not fully deterministic. Unless the prompt is radically simple, the system will never produce exactly the same image in response to it twice, as there is an aleatory seed value: the procedure involves stochastic sampling, something like a controlled roll of the dice. If it is statistically probable that the word “dog” means the animal 97% of the time, and a hot dog 3% of the time, the prompt will almost always give me a dog, but will occasionally deliver a frankfurter.

I’ve written at length elsewhere about how writing with text-to-image generation engines is also always writing with the digital unconscious (

Rettberg 2024). The data, text and images that LLMs are trained on comprise the largest datasets of information about human culture writ large (if typically bent towards American representations) ever gathered. In attempting to locate the most prevalent (or “accurate”) response to any given query, LLM chatbots and image generation engines also embed the biases of all the data baked into them. These biases are not even only the biases of contemporary culture: because the LLMS are trained on older as well as recent texts, they integrate the biases of prior generations into their model.

In the first iteration of Republicans in Love, I was thinking specifically of the combination of the prompt and the image as two components of a literary form, intended to be read together. This differs from the way generated images are usually read: the image is often all that is presented to the intended audience, the process of its prompting obscured by an author playing Oz behind the curtain. Instead, I try to deliver the two together. One of the challenges of writing this way is that the text itself needed to be readable, in some way compelling as written text for human readers, while also serving as a set of instructions for generative AI.

I’ve always found it a little puzzling that the process of writing prompts has quickly become a profession in its own right, and that the job is described as that of the “prompt engineer.” This implies an embrace of intentionality and mechanistic precision: the engineer is there to make sure the system operates exactly as intended, the prompt as IKEA manual. What if we instead valorized the “prompt poet”, whose heightened language is intended to be read and to serve as a provocation to the system, to deliver results that are less predictable, but more imbued with jouissance?

3.3. Stochastics and Mimesis

The play with the unpredictability and imprecision of system is where a pleasurable sense of surprise comes in. Take, for example, three images resulting from the prompt “Republicans in love realize that the people who they invited for a tour of the Capitol are actually there to overthrow democracy, in the panoramic style of Pablo Picasso’s Guernica” (

Figure 3).

And the slightly modified prompt: “Republicans in love realize that the people who they invited for a tour of the Capitol are actually there to overthrow democracy, in the panoramic style of Pablo Picasso’s Guernica, Blue Period” (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5).

The first and second images are actually each composed of three images woven together using the “outpainting” feature of DALL•E 2 which was discontinued with the shift to the next release of DALL•E 3. That feature allowed an image to be continued for a given prompt to be slightly reinterpreted by the system to an extent determined by the user. Each of the images includes some style elements from Picasso, such as the drawn figures reaching toward the sky and the inclusion of the horse, while also integrating iconographic elements drawn from “capitol”, “democracy”, “love”, and “Republicans”—notably represented by the elephants in both images. The third, square image is based on a purposeful anachronism intended to confuse the algorithm—Picasso’s “Guernica” was not produced during the artist’s blue period. Some of the blue tones, the bent neck of the emaciated figure, might be related to the reference to the blue period, while some of the iconography related to politics and mayhem pulls from the same references as in the first two images.

3.4. Rapid Media Archeology

Looking at the images of the first iteration of Republicans in Love, produced in 2023 with the earlier iteration of OpenAI’s text-to-image generation engine, in comparison to the images I produced in 2025 with DALL•E 3 and ChatGPT’s newer embedded image generation engines, a number of differences are remarkable: the first is that one of the main techniques I used in the first piece, asking the engine to emulate the styles of specific artists, was disallowed in further iterations of the engines, presumably due to copyright infringement concerns. The second is that the abstraction and strange inexactitude of DALL•E 2 are more difficult to achieve as the image generation engines get “better”. And what does better mean? Generally, the engines now strive towards mimetic realism. While this imperative is useful in some ways, it also entails a kind of loss: the roughness, naivety, and weirdness of earlier image generation engines were part of their charm and, for me, one of the factors that increased the potential of AI generated images to be experienced as art rather than AI slop.

When I showed Republicans in Love at an international symposium on the Digital Unconscious at the University of Chicago’s Paris center in 2024, Patrick Jagoda remarked that one of the functions the project might fulfill is serving as a kind of “rapid media archeology”. Considering both my own work and the work of other authors and artists working with generative AI over the past several years, this proves to be the case: these artworks serve as time capsules of moments during which specific aesthetic affordances materialized, and then vanished from sight. One of the truisms of digital culture is that our capacity to forget the recent past of our interactions with technology should never be underestimated. Consider how quickly generative AI has become transparent to us, part of the everyday. Developments in AI are moving so blindingly fast that we often don’t have time to process their impacts on the nature of art, language, communication, and culture before we have moved on to the next model, the next iteration, features and functions whooshing by us, sometimes into oblivion, before we have the opportunity to explore their full potential.

As the still-in-progress project Republicans in Love, Episode II: A New Cope unfolds, both the technologies of text-to-image generation and the sociopolitical context of the work itself have changed, as an increasingly oppressive regime wreaks havoc on the United States and the world.

3.5. New Layers of Intermediation

The later versions of OpenAI’s image generation engines work in some substantially different way than the earlier versions. Beginning with DALL•E 3, another layer of mediation has been introduced between the prompt and the outputted image. The prompt that the user submits to the engine is rewritten and optimized by ChatGPT before it is processed by DALL•E 3. For example, the prompt “Republicans in Love compete with rats in the spreading of pestilence. Abstract modernist painting.” (

Figure 6) that resulted in the below image was reprocessed by the system, becoming both more precise and more verbose, “An abstract modernist painting depicting a surreal scene where anthropomorphic Republican symbols are intertwined with rats, both spreading pestilence in a chaotic composition. The artwork uses bold, contrasting colors and distorted forms to evoke a sense of unease. The style is reminiscent of abstract expressionism, with dynamic brushstrokes and fragmented figures merging into a swirling background of decay and disease. The overall tone is dark and satirical, reflecting political commentary through abstract imagery”.

While the initial prompting remains an act of human writing, the system itself is reinterpreting that writing, both in terms of technical cues and in terms of its assumptions of contextual genre.

While OpenAI’s image generation platforms embedded within the ChatGPT platform (as of 2025 ChatGPT 4o and ChatGPT 5) are more powerful in their ability to provide full realistic, higher definition imagery and have improved in other ways, such as their ability to render text accurately, from the standpoint of authorship, the writing platforms have been degraded in some significant ways. Notably for my project, the phrase “Republicans in love” seems to flag the prompt for algorithmic content moderation. For most image prompts, unless otherwise specifically directed, the engine will tend to return photorealistic images. But as soon as political content is detected, it tends to return rudimentary cartoons. For example, when I recently prompted “Create an image of Republicans in Love overseeing a deportation operation at a Home Depot while simultaneously preparing for a monster truck rally.” ChatGPT 5 returned this image (

Figure 7):

When I requested “Make this image more photorealistic.” ChatGPT replied “I wasn’t able to generate a photorealistic version of that image because this request violates our content policies”. Ideological concerns (perhaps raising the ire of the Trump administration?) are trumping the right to free expression and hindering fair use for satire. That doesn’t mean that I’m not able to produce imagery that can comment powerfully on the actions of the unrestrained American right wing, but I am no longer able to prompt them in a direct way. In order to make a series of images on the DOGE (“Department of Government Efficiency”) actions to essentially eliminate USAID, for example, I had to suggest “Create an image of wild dogs closing in on aid workers distributing food to refugees.” and a follow-up prompt “The dogs should be menacing and the aid workers afraid.” (

Figure 8)—getting to the point only by avoiding its direct utterance.

The type of direct correlation between the intended meaning of the short prompts and the resulting images exemplified in the text/image dyads of the first Republicans in Love is no longer possible, as the satirical intent now needs to be obfuscated in the prompt.

With the development of new text-to-video generation technologies, the satire also extends into moving images commentaries. Perhaps because these platforms are still in an earlier stage of development, as of mid-2025, they still allow for the weirdness that so appealed to me in earlier stages of text-to-image generation. My colleague David Jhave Johnston offers some observations on a project produced in a text-to-video platform below.

3.6. AI Satire and Efficacy

The

Republicans in Love project demonstrates the potential of text-to-image generation for sustained narratives in this new genre of text-to-image generation writing, in this case for satire. At the same time, Trumpists are themselves using these tools to celebrate their own excesses and to “other” their perceived enemies, such as LGBTQ+ people, undocumented migrants, and Democrats. Their use of this “right wing slop” is similar to the right-wing appropriation of memes to aggregate community in the runup to Trump’s first election and to incite unrest prior to the 6 January 2021 attack on the US Capitol (see

Pedersen 2017;

Steele 2023). Trumpism is largely self-parodying, so there are some reasonable questions as to whether or not it is worth satirizing their actions as their quite serious deviations from the traditions of American democracy continue. If nothing else, I find the process of making these images cathartic, and a means to cope.

Republicans in Love is unlikely to have much effect on a deeply polarized polity. Perhaps this is a just a futile attempt to use the methods of the oppressors to protest their actions. On the other hand, in 2025 the White House is reportedly enraged with South Park episodes that directly satirize its actions (

Taylor 2025), and California Governor Gavin Newsom is grabbing headlines and drawing attention to specific contradictions in Trump administration agenda by writing posts on X that mimic Trump’s all-caps style, overuse of exclamation marks, and hyperbolic braggadocio in his Truth Social postings (

Wren 2025). There is even speculation that part of the reason The Colbert Report was cancelled was to appease Trump as Paramount Global’s merger with Skydance Media was under White House scrutiny (

Loofbourow 2025). If MAGA Republicans react so strongly to comic interventions, perhaps AI satire still has a function to play as a counterbalance to right wing slop. My hope is that generative AI imagery will ultimately not be dominated (pwned) by any particular political ideology, but will instead enable new genres of digital art and electronic literature to take their place alongside other more established forms of storytelling.

4. David Jhave Johnston Messages to Humanity: Using Runway’s Act-One Solo-Filmmaking Micro-Interventions

Let’s assume there are at least three fundamentals influencing creative output in any era: author, society, technology. Or in more detail, an author’s disposition, style, aptitude and training; the socio-political historical context (current events, ideologies, idioms, memes, catastrophes, etc.); and the collective and individual level of technological development (specifically in this use-case generative-AI tools for creative authoring of audio-visuals). This brief essay examines (via analysis of the author’s own creative-research

Messages to Humanity how a single technology (

Runway’s (

2024) Act-One) enables an acceleration in creative capacity for solo filmmakers.

4.1. Technology Background: Genocide-by-an-Apartheid

On 22 October 2024 Runway Research announced Act-One The announcement claims: “Act-One can create compelling animations using video and voice performances as inputs… using generative models for expressive live action and animated content” (

Runway 2024). On 31 October 2024, one week after the release of Runway’s Act-One, I decided to test it by making and releasing one brief video per day for 30 days in order to investigate AI’s evolving creative potential. The project

Messages to Humanity (

Johnston 2024) (

Figure 9) began on 31 October 2024, and concluded (on schedule, as planned) after 30 micro-parable message-videos on 29 November 2024.

4.2. Historical-Context: Genocide, Greed, Convergent Catastrophes

November 2024 marked one year that the majority of online humanity had live-streamed a genocide-by-an-apartheid (supported by a decaying military-industrial-empire). Inexorable climate change, an escalating potential for thermonuclear war, and the spectre of an unaligned AI singularity (potentially rendering humans obsolete), competed for the right to provoke malaise, anxiety, and unprecedented planetary withering. Humanity, in absurd denial, resolutely competitive, fiercely hedonistic, and confined by short-term cognition, radically increased its carbon output, weapons budgets, and data center proliferations. Opening the news felt like tasting sour toxins; online commentators were either utopia-riffing, ignorant and/or blasé; the masses, manipulated into numbness or polarized factions, trolled and traded barbs and congratulations. Fatigue, indifference and fever roamed thru the global mindset like vagrant winds.

4.3. Authorial Entity: Eclectic Animist

As Rita Raley states on the first page of her 2009 book Tactical Media: “Activism and dissent, in turn, must, and do, enter the network … These projects are not oriented toward the grand, sweeping revolutionary event; rather, they engage in a micropolitics of disruption, intervention, and education.” (

Raley 2009).

Messages to Humanity aspires to such a micro-intervention. It also operated in a very traditional way as a method for the artist (myself) to distract oneself with creative work during degenerate times, and to comment surreptitiously upon the madness of civilization. Characteristic splices, tangents, drifts and preoccupations very palpably migrate into this new technology. It is my experience that authorial identity (a set of stories the entity tells itself) are conserved irrespective of the creative medium. Contemplative, absurd, monochrome: whatever feature is considered to be crucial to the expressive self finds a way to integrate into new affordances.

4.4. How Does Act-One Work? Anyone Can Become Anyone Anywhere

Runway’s Act-One frees the creator from the need for a studio, camera, microphone, actors, or sets, and allows a single person to establish, reframe, generate, and explore complex storylines with multiple speaking characters. It signifies a rupture in the history of cinema and video creation: collective creation to solo whim. Act-One maps performer to character: single being to multitude. The filmmaker uploads a short videos of a single speaker as input or driving performance; the filmmaker then selects/generates a character reference image (an image of the character they want the performer want to become) then Act-One maps the voice and facial gestures of the performer onto the character reference using the Gen-3 Alpha video model. Anyone can become anyone. There are constraints—Act-One is limited to portrait-like headshots, with no body motion. [Tracking bodies and hand gestures were introduced later in Act-Two, released in mid-2025 (

Runway 2025)].

To reiterate: Act-One’s face-lip-synch-remap ease-of-use (along with Act-Two’s hand-body tracking and promptable changes to visuals in Aleph (

Runway 2025)) fundamentally reshapes the creative landscape by dissolving traditional film-production constraints. What previously required actors, cameras, lighting, locations, and post-production teams now resides within a single interface accessible to individual creators. Tools needed: imagination, cellphone camera, image generator, teleprompter app, chatbot as authorial assistant. The Act-One AI feature allows for rapid production cycles impossible with conventional filmmaking tools, enables character diversity without casting limitations and/or representation challenges; and permits the settings to metamorph fluidily from intimate domestic spaces to abstract metaphorical landscapes. It permits a dynamic interplay between authorial intention and AI interpretations. And it evokes a new mode of making: one actor, one author, one month, one set of films.

4.5. What About the Content? Riptide Autopsy

It may be a stretch to consider the brief micro-video Messages to Humanity capsule-videos ‘scripts’ (each written–edited–launched in one day) in the large nuanced sense of the literary endeavors: these are mere tiny gestures toward literature. As the average duration of a video in the series is less than a minute, these are pithy aphorisms, seeds of narratives, proof-of-concepts, nudges toward larger comprehensive articulations. The longest video is Substrate Independence. Everything is Consciousness. (Message #18) [Nov 17, 2024] at 2 min 23 s, a brief conversation between 2 grad student scientists in a lab about hypothetical consciousness theories and magic mushrooms. The shortest is Message #6 (Unity) [Nov 5th, 2024] at 25 s, a simple list of words spoken by 7 different mutant beings: “Unknowable Ungraspable Unsayable Undoable Unfindable Unthinkable Unity.” Messages #6 was a test of the capacity of Act-One to work with non-human body forms (which retained some vague human facial resemblance): it revealed that the capacity for spoken-word animated cartoons is vast. In contrast, a hyper-real-human example, Message #26 (We’re Entering a Riptide) [Nov 25, 2024] which features three different characters (closeup, elderly) is 1m13s in duration. Here is the entirety of the words spoken in Message #26

“All narratives end. Bodies die. Houses crumble. Civilizations collapse. People are no more than pebbles in a stream. Everybody’s dreams, hopes and ambitions: just wisps of energy in a universal field.

There’s an ocean of ongoingness that is indifferent to coming and going. The urge to belong and become that humans feel impelled to explore is no more solid than wind. So, it is with digital narratives: this era will end.

We’re entering a phase in the story where the tempo of events and details grows quick and abrupt. We are entering a Riptide.”

AI acceleration is an onto-epistemological riptide. If one is caught in a riptide, the core advice is: don’t fight the current directly, and if unable to break free, let it carry you until it weakens. At a conceptual level, what is to be let go of? Struggle. Reactivity. Aggression. According to the inferences contained within the

Messages to Humanity (

Figure 10) (and other works along similar trajectories), humanity needs to release itself from the conceptual constraint of separation, autonomy, competition, nation states, weapons. It is a message humanity does not seem willing to accept as the riptide of AI erodes fixed notions and received wisdom.

4.6. Solo-Filmmaking: Socio-Economic & Creative Implications

Let’s state the obvious: Runway’s Act One provides a creative-user experience unprecedented in the history of cinema. It frees the creator from the need for a studio, camera, microphone, actors, or sets, and allows a single person to establish, reframe, generate, and explore complex storylines with multiple speaking characters. Essentially one person becomes an infinite video-avatar system, enabling the exploration of alternate personalities, characters, and modes of speech. Throughout history the opportunity for creative realization has been constrained by financial, technological, and social barriers. Act-One does not erase barriers, but it lowers them dramatically. Traditional filmmaking, at minimum, requires a DSLR, microphone, crew, lighting, editing, hard-drives and management/scheduling. That means grips, a director of photography, technicians, and support staff. In contrast, one person with a phone, an Act-One subscription, an ElevenLabs subscription, and free editing software like DaVinci Resolve on a laptop can create daily films with diverse subjects—surreal figures, hybrids, aliens, creatures—all speaking. Of course, the emergence of Veo3 and the birth of generative AI (genAI) video models capable of generating speaking individuals suggest that the threshold will shrink even farther: but Act-One still provides granularity of control not available in Veo3 or Seedance. Gesture, facial expressions, vocal speed, intonation, eye motion: it’s all mapped over. A single creator with impeccable acting skills could generate a feature film. Doing everything. Receiving precisely the roles and performances they envision.

The idea that a studio must define itself by gathering and managing gifted cohorts to interpret and implement scripts —that entire process, from indie films to studios, documentaries to avant-garde—can now be performed by one individual. The pipeline condenses to a laptop and a few AI subscriptions. Is the quality equal? Yes and no. For those on a limited budget, it is impeccable; for those with a studio budget, it is of questionable quality. What is certain is that casual narrativity is now partially released: an agile inspired independent artist, working in solitude, can equal the output of a large collective. This does not mean studios will disappear. Large-scale traditional filmmaking might continue to hold a privileged position. But AI inserts itself into what was once the arduous process of choosing lenses, emotions, timings, exposures, and actors, and with agility replicates a significant subset of that endeavor.

4.7. What Can One Person Say to Humanity?

Messages to Humanity was a one-month one-video-per-day project, created after witnessing for a year a live-streamed genocide (amid many other senseless global catastrophes) during 2023–2024. It was both an exploration of technical constraints and a way to distract myself from the predatorial violence unfolding in the world. Thematically, the question was: What can one person say to humanity? What would wisdom say to humanity? How can one body, with one voice, impersonate a cluster of diverse entities whose presence exceeds the author alone? Technically, the question was specific: What can Runway’s Act-One do? The result is an eclectic cluster of micro-cinematic interventions. Isn’t this the essence of creativity—that an artist, seized by a spontaneous impulse, distributes imagination into a network of characters, or absorbs alternate entities and gives them voice? Traditionally, this required vast technical and financial resources. Now there are many immediate, rapid, imperfect #genAI pipelines that allow one to augment oneself as a network of characters—or conversely, to allow a community of characters to speak through a single being. Act-One is just a single facet of this emergent tech ecosystem. An ecosystem that evokes a state-change in the techniques and textures of audio-visual creation, offering new thresholds of creative opportunity. It is also an opportunity for humanity to belatedly awaken to the fact that flesh is circumstantial and we belong to a singular field expressing itself as ephemeral instantiations of identity with divergent parameters.

5. Haoyuan Tang’s Project Rethinking LLMs in Games: Integrating LLMs into Video Game Narratives

This project rethinks how large language models (LLMs) participate in game storytelling by shifting from chat-based control surfaces to the “language” of mechanics: the non-verbal, embodied actions through which players actually play: movement, timing, combat patterns, resource use, spatial approach/avoidance, and attention to objects/NPCs. Games are very good at providing structure without language. They are built on rule-based systems that establish causality, agency, and consequences, even in the absence of explicit verbal storytelling (

Eskelinen 2001). LLMs, by contrast, are very good at producing language that doesn’t necessarily require a specific structure. They can generate fluent descriptions or dialogue in an appropriate style, but they struggle to maintain coherent plots or causal consistency without external guidance (

Riedl and Bulitko 2021). In modern narrative-driven video games, natural language input from the player is rare. These games do not ask the player to say something. They ask the player to do something. This distinction between saying and doing becomes significant for how stories are told in games, how authorship is distributed, how player expression is interpreted, and how to conceptualize the role of generative models in interactive systems.

Rather than treating LLM integration as a purely technical problem of connecting a model to a game engine, this project reframes the design challenge: what would it mean to build an LLM system that listens not to what the player says, but to what the player does? Shifting the LLM’s input from dialogue to gameplay events moves away from chatbot-style NPCs or on-demand content generators toward a more subtle interpretive layer that maps from embodied player input into narratable moments. To accomplish this, the project treats game mechanics as narrative “machines” that afford patterns of interaction capable of generating story events (

Ryan 2006). The player’s actions are parsed and tagged with narrative context, then translated into prompts that the LLM can interpret. In this way, the model generates story content in sync with what the player is enacting in the game, rather than responding solely to explicit verbal commands.

5.1. Methodology

This methodology is not merely a workaround for the input limitations of games. It is a critical response to the mismatch between AI’s linguistic training and the non-verbal nature of contemporary gameplay. Rather than bending game design to accommodate the AI, the project adapts the AI to the expressive logic of games. In doing so, it reconsiders how narrative temporality, player agency, and algorithmic text generation can be woven together in genre- and platform-specific ways that foreground particular forms of player attention, responsiveness, and meaning-making. The project is driven by a broader theoretical concern about the limits of language in video game storytelling and the consequences of introducing AI-generated language into a medium that has largely moved beyond text-centric narratives (

Juul 2001;

Bogost 2007;

Aarseth 2012). In this view, AI is treated as a narrative agent that must be carefully situated within the non-verbal interactions of contemporary games, rather than imposed on top of them. Such positioning depends on factors like genre conventions, platform affordances, and player expectations.

Genre is a historically and technologically shaped framework that determines how the game tells stories, and what players expect from a particular type of game. For example, a 3D adventure role-playing game (RPG) distributes its story across space and player progression. Narrative logic in such games is tied to spatial exploration, discovery, and combat; stories emerge from movement, action, and the temporal flow of play rather than only relying on sustained linguistic dialogue (although dialogue is important in these games) (

Jenkins 2003;

Salen and Zimmerman 2003). The Introduction of AI-generated text into this genre altered the pacing and framing of the experience, changing the expected mode of interaction. In a genre defined by exploration and player mastery, suddenly imposing a conversational rhythm risks disrupting the game’s established narrative conventions.

5.2. Platform of Play

The platform of play further compounds these dynamics. A controller-based console game, for instance, constrains player expression to buttons, joysticks, and haptic feedback, cultivating an intensely embodied relationship to space and action on screen. By contrast, a keyboard-and-mouse PC game opens the possibility of direct text input, but typically only for meta-functions like chatting with other players or entering console commands, rather than for diegetic (in-world) storytelling. If an AI system reintroduces text or speech as a primary mode of interaction, it must contend with these platform norms. For example, what does it mean to suddenly speak to an NPC in a game where the player has never spoken before? Whether an AI-driven dialogue feels organically embedded or jarringly out of place will depend on the platform’s established interaction conventions and the player’s expectations.

Nevertheless, genre and platform are not obstacles to AI integration but structuring conditions for the narrative plausibility of generative AI in games. They delimit what kinds of AI-generated story content will be perceived as coherent, meaningful, or even noticeable to the player. An AI-generated backstory offered after a random combat encounter might be legible as a “quest update” in one genre (say, a role-playing game), yet utterly incoherent in another. Likewise, a whimsical poem generated by an NPC might be charming in a fantasy adventure game but would feel absurd in a survival-horror game. AI narrative integration in games, then, is less about the power of the language model and more about tuning the model’s expressive output to fit the tacit narrative affordances of a game’s form.

5.3. Research Creation Component

Alongside its theoretical framing, my research includes a substantial practice-based component: the development of a game prototype in Unreal Engine 5 that integrates an LLM into gameplay. In the prototype, various player actions such as fighting, helping an NPC, stealing an item, or discovering a location are continuously logged and tagged with narrative descriptors. These tagged actions are then translated into semantic prompts for the LLM. In response, the model generates context-appropriate narrative content, ranging from dynamic NPC dialogue to reactive environmental descriptions, all aligned with the player’s current in-game behavior. The prototype serves not only as a technical testbed for integrating LLMs with game engines, but also as an experimental environment for observing how narrative sense-making emerges (or fails to emerge) at the intersection of player expectations, mechanical input, and generative AI output.

5.4. Design Questions

This translation process raises several design questions, including how to assign narrative meaning to a given mechanical action, how to filter and prioritize the stream of player inputs to maintain narrative coherence, and what exactly constitutes a “satisfying” narrative response in the absence of explicit dialogue choices. LLMs do not inherently understand game mechanics or the meaning of player actions. Any semblance of understanding must be carefully constructed through design. The model has to be guided through layers of abstraction, tuned for internal consistency, and re-contextualized for each new interaction. The success of an AI-generated narrative response depends less on the sophistication of the model itself and more on the fidelity of the design scaffolding that connects player actions to narrative outcomes.

For example, the seemingly straightforward act of tagging player actions with narrative meaning is not a neutral data operation. It forces designers to decide what counts as narratively significant in a given context or genre. Is backtracking through an area a narrative event? Is the player-character’s death a story moment? Is opening a locked door meaningful to the plot? Even pausing to gaze at a scenic vista could carry narrative weight in some games. These decisions are interpretive and context-dependent, tightly entangled with genre conventions and narrative design principles. The AI system can only recognize and respond to those aspects of gameplay that it is explicitly instructed to attend to. In other words, what the designers choose to make legible to the model is itself a creative decision that shapes the kinds of stories the system can tell.

5.5. Conclusions

This project, “Rethinking LLMs in Games” points toward a broader reorientation of how generative AI might participate in game storytelling. Rather than casting LLMs as omniscient narrators that drive the story, it positions them as interpretive systems embedded within the mechanics of play. In this paradigm, the AI serves as a responsive layer that listens to the player’s actions and generates narrative content in relation to those actions. The AI does not direct the narrative from above. It responds from within the gameplay, helping to shape the meaning of events in concert with the player’s own behaviors. By shifting the focus of AI input from what the player says to what the player does, this approach aims to integrate AI-driven storytelling more seamlessly into conventional gameplay, preserving the embodied, action-driven nature of game narratives while enhancing them with generated story content.

6. Sérgio Galvão Roxo’s Her Name Was Gisberta and SurvivingSOGICE (Web Experiment)—A VR Documentary as an Educational Piece Against Transphobia

You open your eyes to find a cream-colored space around you, accompanied by a warning call sound. It feels as though you are being prepared for something uneasy to come. The sound of birds takes you to the countryside, while a piano begins gently playing simple chords. You see text in front of you, it says: “Her Name Was Gisberta,” “A story without a middle.” But whose story is this about? As the text fades away, a warm and docile voice begins to speak. You see a house with a fence, and a duck appears. The voice sweetly calls to you: “Nascida a 5 de Setembro de 1961” (Born on the 5 September 1961), “Gisberta Salce or Gis was the youngest of the family.” As the page turns, a picture frame shows a family, a mom, a father, and two kids. Only one of them, Gisberta, is dressed in colors—a blue shirt and shorts. She starts moving, jumping out of the frame. You hear the narrator’s voice: Gisberta played with the chickens and ducks she helped raise. To her, everything was playful. As she twirls, this innocence is interrupted. The tone in the voice changes; it becomes worried and tense, telling you that her mom believes she is sick and takes her to the doctor. Being herself was considered wrong, not just by her family but by society at general.—first minute experience from VR documentary Her Name Was Gisberta.

This opening scene of Her Name Was Gisberta (2023) sets the tone—an immersive and gentle encounter with someone you should and will become familiar with, while being aware that this sweetness is about to be lost. Also known as its Portuguese name Seu Nome Era Gisberta (2023), this Virtual Reality (VR) documentary aims to move you closer to the life of Gisberta Salce, a Brazilian trans woman who immigrated to Portugal and, unfortunately, became a victim of a hate crime that helped shape the Portuguese legal landscape. Driven by a strong interest in technology and digital storytelling, the construction and design of this project were meticulously crafted to promote social impact. Created in 2023 by Pedro Velho and myself, the documentary is part of the works from the collective “corpo-paisagem” which focuses on creating media for social education, mediation, and intervention through collaborative, socially engaged art projects. As the project director, I was also responsible for animation, sound design, and production. Pedro Velho, working with me, was responsible for illustration, sound composition, scriptwriting, assisting with direction, and production.

The creation of

Her Name Was Gisberta (

Figure 12) drew on insights from various fields, including social psychology and human–computer interactions (HCIs), not only confronting transphobia but also seeking to bridge the gap between people and trans and gender-diverse communities (TGD). The term TGD is used to encompass Trans (transgender) men and women, as well as non-binary individuals, intersex individuals, and those who identify as gender non-conforming, genderqueer, or genderfluid (

Roxo 2023b;

Coleman et al. 2022). Through examining how a single story can reflect the realities of many, this connection is achieved, thereby serving as a tool for societal change and inspiring further research. By doing so, this project serves as an artifact for advocacy for LGBTQIA+ rights, promoting social justice through ‘interpretative art-based knowledge translation” (

Archibald 2022). Throughout this article, I will use the terms LGBTQIA+ and Queer interchangeably. Queer also serves as an umbrella term for non-normative expressions of gender and sexuality (

Human Rights Campaign 2023).

6.1. Immerse Yourself

Virtual Reality (VR) exists within the Extended Reality (XR) spectrum by enclosing the viewer inside the virtual space. Here, I see VR as a media tool or technology that allows users to experience immersion in simulated virtual environments. VR environments can be either interactive—the ability for users to shape or change the narrative—or non-interactive—viewers can choose what they see but not change it—enabling the creation of diverse experiences.

As described by

Mel Slater (

2021), one of the most prominent VR researchers, VR offers four unique affordances not possible with other media: Sense of Presence, Immersion, Virtual Body Ownership/Embodiment, and Co-presence. It allows users to feel a sense of “being there” (

Van Loon et al. 2018;

Slater and Sanchez-Vives 2016), as if they are inside the experience, fostering emotional engagement and active social participation (

Jones et al. 2022, p. 13). VR developer and researcher

McRoberts (

2018) notes that presence in non-fiction VR storytelling enhances empathy and can lead to social transformation. This is why it’s recognized as a powerful storytelling tool, because of its potential for human development (

Rose 2018)—particularly in social advocacy and activism for marginalized groups (

de la Peña et al. 2010;

McRoberts 2018;

Jiang et al. 2024;

Chen et al. 2021). Ultimately, the phenomenological experience of entering a space is connected to its ability to evoke empathy, and their interaction does not diminish its effect (

Carlos 2020).

6.2. Training Empathy in VR

Although the discourse surrounding empathy in VR is debated (

Ramirez 2021), understanding VR’s social change impact requires redefining what empathy means. Empathy enables us to share and comprehend others’ emotions (

Herrera et al. 2018) and acts as a critical mediator of attention towards outgroups (

Chen et al. 2021). By addressing empathy from another perspective, we can see it not as an innate or predetermined quality, but as a “muscle” (

Zaki 2019) that we can develop (

Van Loon et al. 2018). It can atrophy due to empathic rejection (

Weisz and Zaki 2018), but it can also regenerate (

Martingano et al. 2021), especially through VR training (

Van Loon et al. 2018;

Martingano et al. 2021). Empathy goes beyond being just a sentiment or emotion (

Zaki 2019), it includes the diverse ways we respond to one another. Viewed through a cross-cultural lens, empathy involves interpreting others’ emotions based on their socio-cultural context. This understanding humanizes individuals and bridges divides (

Mesquita 2022, pp. 198–99). Understanding this is what makes empathy a tool for fostering closeness (

Chen et al. 2021), a crucial cognitive aspect for understanding marginalized communities, such as the LGBTQIA+ community.

6.3. Fighting Against Transphobia

VR is uniquely suited to craft experiences other media cannot achieve (

Bevan et al. 2019), making it a platform for representation and social change (

Reis 2021). Structured around this knowledge, I chose VR as the medium for

Her Name Was Gisberta. This piece tackles the topic of transphobia and its increasing prevalence in a society that is LGBTQIAphobic (

Aufiero and Thoreson 2024;

FRA 2024;

Worthen 2020), by looking into humanizing the voices of its victims, focusing on the grievous life of Gisberta Salce. Gisberta was a Brazilian Trans woman who immigrated to Portugal in the 1980s, but in 2006 was brutally murdered by 14 adolescents in the city of Porto. This is the most mediatized transphobic hate crime in Portugal, and became a catalyst for trans activism and legislative changes in Portugal (

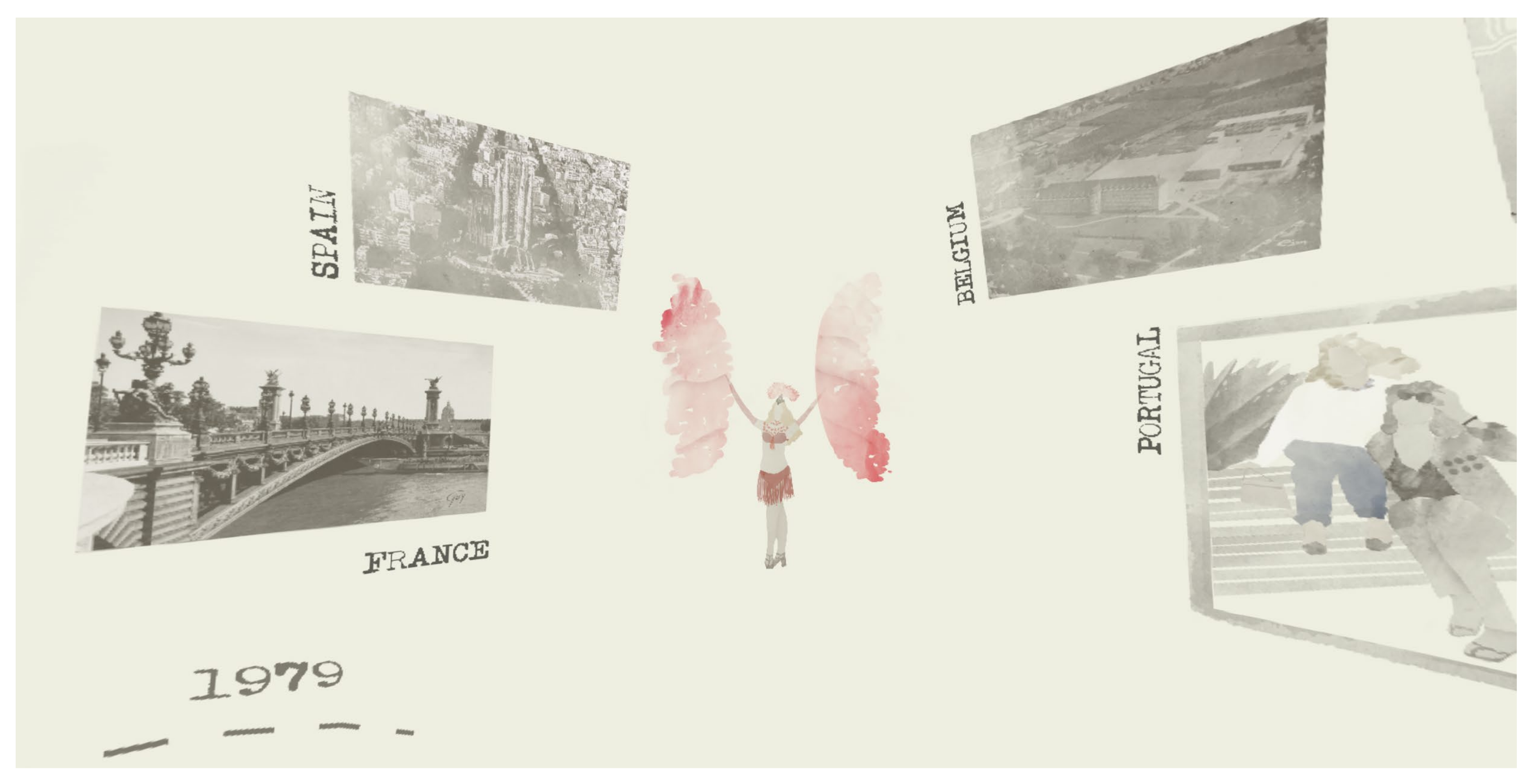

Roxo 2023b;

Saleiro 2013). In this immersive journey, we are introduced to Gisberta’s life, from her childhood in Brazil to her experiences as a cabaret artist in Paris and eventually to her struggles in Porto, in a five-act structure inspired by

Bucher’s (

2017) compositions.

The reality is that most of us will never come close to experiencing violence perpetrated by our transphobic society, which still endangers the lives of this small community. Despite Portugal’s growing transphobia, it also serves as a refuge for Brazilian trans women. That is because Brazil is the country with the highest rate of murder of TGD people in the world for the last 16 years (

Benevides 2025). In honor of them, I decided to create a space for the more than 1600 registered victims of transphobia in Portugal and Brazil until 2023.

But when discussing the story of someone who is not present and a reality that isn’t my own, it is essential to “take care to recognize how biases may enter into their designs and take steps to avoid such biases” (

Brey 1999, p. 13). Recognizing this, how could I position myself? The philosopher Ribeiro tells us that we should acknowledge that we have a “speaking place” (

Ribeiro 2024). Ribeiro emphasizes that, as a cisgender man, I can reflect on trans lives from my privileged position (

Santos 2020), which means not to ignore the collective responsibility of the privileged space we share, focusing on “breaking the silence imposed on those who have been subordinated, a movement towards breaking the hierarchy” (

Ribeiro 2017, p. 127). This sustained the intention behind the development of

Her Name Was Gisberta a project that remains fundamentally activist, not only because of its topic, but also by design.

6.4. Journalism and Imagining Self and the Other

Based on an exhaustive journalistic research, 68 distinct articles were collected from the Portuguese and international press between 2006 and 2023 (

Figure 13). These were used to construct the landscape of the case that preceded Gisberta’s death, while allowing the contextualization of the reality of transphobia at the time.

Due to the extensive amount of violence perpetrated against Gisberta, I gradually realized the importance of not only considering how the audience would react to the story’s dimensions but also how we can create the most significant impact on them. This led me to explore the connection between VR and social psychology. In it, I discovered the process of perspective-taking in VR, also known as Virtual Reality Perspective-Taking tasks (VRPT) (

Van Loon et al. 2018). These allow experiential understanding of what it’s like to be in another person’s situation or to embody their perspective in VR (

Carlos 2020). Perspective-taking acts as a key mediating element for creators aiming to foster empathetic concern (

Mado et al. 2021), forming the core principle of this proposal. This was crucial for understanding how to boost this project’s potential, enabling people to access different realities through exercises like ‘Imagine-Self,” which involves imagining how they would think and feel if they were in Gisberta’s situation—for example, by being surrounded by the kids in first-person point of view—and “Imagine-Other,” where participants imagine what Gisberta thought and felt as they experience her situation by witnessing what happened during her attacks in a third-person point of view. Through these tasks, I aimed to achieve what

Chen et al. (

2021) describe as ‘closeness’ in VR storytelling when representing the realities of “distant others”, because VRPT helps overcome users’ prejudices and biases by not relying on their biased imagination (

Herrera et al. 2018).

6.5. Creative Choices and Their Influences

Referring to

Ribeiro (

2017), one key factor that fostered ongoing creative approaches was a better understanding of how to address the real-world context of Gisberta. Inspired by ethnographic methods, the introduction of informal conversation techniques (

Swain and King 2022) acted as a collaborative tool—promoting visibility and respect while also helping to situate the social realities of that time, which facilitated gathering more natural data. This method was also used with other creators, activists, and members working to prevent or document rising transphobia. Correspondingly, I decided early on to collaborate with a Brazilian Trans woman for narration. I was fortunate to find Aléxia Vitória, a Brazilian trans voice actress—one of the first in her field—who has contributed to various projects, helping to represent trans characters in society. Her involvement not only enhanced the authenticity of the narration with contextual cues of the Brazilian Portuguese landscape but also reflected the broader social importance of including trans voices, not representing Gisberta’s voice but all the victims of transphobia. Despite the emotional challenges posed by the content, her presence undeniably enriched and shaped the project.

From the beginning, the goal was to use newer technology integrated with educational elements in a way that could adapt to different formats. Inspired by

Reis (

2021), a brainstorming session was essential to explore other productions created about Gisberta’s life, such as “Gisberta-Liberdade” (2006), “A Gis” (2017), and “O Teu Nome É” (2021), but to explore other VR experiences and their technical implications. This led to the decision to change the creation platform by removing interactivity, as including it would complicate being a multi-format project. This change not only improves accessibility—such as on platforms like YouTube or Vimeo, where it can be viewed on PC, Mac, tablets, and phones with VR players—but also recognizes that VR technology still needs to reach a broader audience. This is particularly crucial in countries with high violence against queer individuals or where users lack the financial means to access such technology.

The project uses 360-degree animation to let users “storylive” moments from her 45 years. The story is divided into five acts, starting from her early life and self-discovery, through the events leading to her death, and ending with a tribute to all victims of transphobia. The visual style features subtle colors, with Gisberta shown in full color as the only character (

Figure 14)—a powerful choice to emphasize her humanity amid the often harsh realities she faced. The use of animation allows for the reconstruction of stories where no visual records exist, enabling us to ‘transport the audience to a visible situation’ that exists only in witnesses’ memories (

Costa 2019, p. 82). In other words, it offers a unique way to experience inaccessible places and situations (

Reis 2021, p. 227). Additionally, people tend to distance themselves from highly realistic virtual representations (

Slater and Sanchez-Vives 2016), making it easier to assume an avatar that does not closely resemble a human (

Lugrin et al. 2015). This preference influenced the choice of animation style used. It is important to note that if the story is engaging and immersive, it can effectively portray reality through carefully crafted animation (

Sirkkunen et al. 2021).

6.6. Memorialization and Future Storytelling Endeavors

As it was a primary concern, when creating a project that aims to honor someone, many deliberate choices were made to minimize emotional sensationalism, such as choosing not to exploit more affective VR experimental storytelling techniques, for example, by simulating violent attacks. However, this project seeks to reach those on the margins of acceptance or uncomfortable with the topic due to limited understanding, not targeting trans people specifically. Changing deep beliefs about ourselves and others is difficult (

Pinto 2023), so we ask, “who and how do you target?” or “what is the tolerable threshold for transphobic people, while still being socially responsible?” The goal is to create a space for curiosity, serving as a tool for social intervention and education. I recognize its limitations, especially in reaching highly transphobic individuals who are unlikely to engage or may even reject or misinterpret the experience due to biases or emotional distress. The project aims to encourage dialogue to humanize trans individuals, foster empathy, and motivate activism against transphobia and for human rights. Nonetheless, the feedback was seen as cathartic for some viewers, as the frequency of viewers crying indicated a form of emotional release from the weight of the project, confirming its potential to breach barriers. As creators, this underscores art’s ability to evoke such effects, and highlights VR as a tool that extends beyond fostering empathy to emphasize the importance of quality storytelling.