Far from being just ‘tonally moving forms’ (Hanslick qtd. in

Kivy 2002, p. 60), ‘music sets the psyche in motion’ (

Koopman 2001, p. 328, my translation), for what ‘approaches’ us when we listen to music are not tones, but a complex sequence of tiny air pressure variations, ‘the result of longitudinal waves caused by the sound body’ (p. 328, my translation). More than dwelling on a mood, the musical experience is an ebb and flow of highs and lows, calm and restlessness, intensification and relaxation, deeply involving corporeal embodiment. It is this bodily experience that gives us a seemingly direct ‘understanding’ of why notes can ascend and descend, create tension or give away to mixed feelings. A further tangible and material understanding of music can be perceived through its inscription; the musical score is to the general listener of music far less accessible than the corporeal phenomena mentioned but nevertheless represents the movements of music on a different plane. A complex and at the same time aesthetically evaluated notational system, it has been referred to in literature only on a few occasions, using various strategies and assigning to it numerous functions.

Literature can generally refer to music by thematizing its acoustic qualities and effects on the body, by evoking a specific performance or song while also being able to imitate certain sound patterns and rhythms using poetic stylistics. Of the many strategies through which music can be incorporated into literature, a basic level of engagement has been hitherto under-theorized: the function of musical notation in and for literary texts. This is surprising because it is here that music and literature share common semiotic properties; music can be coded and decoded within a system of written signifiers—i.e., the notes on a page—and thus can be said to have a ‘text’. But what happens when literary texts allude to the signifiers of this other notational system, this other musical text? What happens when characters in literature view the ‘notes on a page’? Which imaginary potentials does the musical score afford in the perception of the same by musicians and non-musicians alike? Which roles do these in turn play for modern literary texts that explore new narrative pathways, which, it may be argued, exposes a grappling with the limits of expression itself?

The following proposes to introduce the term

notational ekphrasis in order to fill this gap.

Notational ekphrasis means the visual representation of musical notation within literary texts. This is important, as it showcases a further experimental strand within the nature of Modern texts that themselves often grapple with the limits of expression at the turn of the 20th century. For, just as texts can relate to other media by using site-specific intermedial strategies, they can also refer to the visual properties of musical notation and thereby to its inherent signification processes. This article will focus on the (inter-)medial presence and potentialities of musical notation in paradigmatic Modern short stories, such as Katherine Mansfield’s “The Wind Blows” (

Mansfield 1921, originally published in Signature magazine in 1915), Virginia Woolf’s “The String Quartet” (1921) and Vladimir Nabokov’s “Music” (1932). In order to discuss these three examples, I will introduce and outline the term

notational ekphrasis, which will enable the following conclusions: (1) defining the hitherto uncertain status of the representational characteristics of ‘notes on a page’ in literary texts, (2) mining the creative explorations of these intersemiotic dynamics by differentiating how musical notation is mediated through characters that are both musicians and non-musicians and (3) furthering an understanding as to how musical notation—but also notational systems in general—function in their ways of encoding and decoding. For this, I will differentiate and argue for ‘overt’

notational ekphrasis in Mansfield and Nabokov and ‘covert’

notational ekphrasis in Woolf.

1. Towards an Idea of Notational Ekphrasis

My term,

notational ekphrasis, in part takes its cue from John

Hollander’s (

1988, p. 209)

notional ekphrasis, which he uses in order to describe imaginary works of music, such as Vinteuil’s composition in

Swann’s Way of

Marcel Proust’s (

1913, Vol. 1)

In Search of Lost Time. His observations can be easily transferred to later works such as the “Cloud Atlas Sextet by Robert Frobisher” in

David Mitchell’s (

2004, pp. 359, 407–8)

Cloud Atlas. However, in differentiation to Hollander’s term,

notational ekphrasis does not focus on imagined musical settings in literature but on the imagined visual potential of musical notation as described through literature, as—so far—scholarship tends to overlook notation as a semiotic and visual object when referenced in literary texts.

The presence of musical notation in literary texts is heavily undertheorized, given the large and rich field of intermediality. From early semiotic and typological approaches by

Calvin S. Brown (

[1948] 1987),

Steven Paul Scher (

1968) and

Nelson Goodman (

1969) to later contributions by

Werner Wolf (

1999),

Irina O. Rajewsky (

2002,

2005) and

Emily Petermann (

2014), the field of intermediality has brought forth three core strategies when differentiating between general musico-literary phenomena: (a)

thematization, (b)

evocation and (c)

imitation. Each focuses either on the semantic, referential or quasi-mimetic affordances that literary language can utilize with regard to music. (A)

Thematizing music in literature means mentioning it on a broad level (i.e., in the mode of ‘telling’) by relating the occurrence of music playing somewhere, its general characteristics and effects, the aesthetic beauty of a melody or phrase and/or emotions or memories connected to these. The literary text is thus ‘charged’ semantically with common musical notions and themes that can, in turn, be related to existing music, which appears as a lower-level actor.

1 (B)

Evoking music in a literary text means quoting an existing piece of music. This can be the case of a paratextual name-dropping (i.e., ‘Beethoven’s Ninth’) or by quoting from the lyrics of a specific song, which

Werner Wolf (

1999, p. 67) classifies as an evocation “qua associative quotation”.

2 (C)

Imitating music in literature creates intersemiotic tensions that necessarily ‘corrupt’ the traditional form of a text as it seems to ‘try’ to become music (i.e., in the mode of ‘showing’). The target medium of literature does not simply allude to musical notions or directly reference existing music as in the first two examples. Instead, music becomes a dominating actor within the literary medium that defamiliarizes the text to various extents. Literature here emphasizes the acoustic dimension it can share with music by using poetic stylistics such as rhymes, assonances, lexical and non-lexical onomatopoeia, repetitions, etc.

3But how do musical scores factor into these traditional observations and strategies? Surprisingly, these have hitherto been viewed as images rather than a further semiotic system within the semiotic system of literature. The reason these intersemiotic dynamics have been overlooked may be because the overpowering appeal of musical expression as a ‘language above language’—as the 19th century dogma of absolute music maintains—can be seen as having appealed to Modernist authors when incorporating music into their texts. It would be counterintuitive for most musicalized fiction to feature this ‘absolute’ medium in a constrained semiotic form, such as musical notation. This can be argued to in turn also have had repercussions for the field of intermediality and how musical notation is evaluated in literature.

Werner Wolf (

1999, p. 41), for example, maintains that “the occasional inclusion of musical notation in a work of fiction” represents a “type of overt intermediality with a dominant (here fiction)”. He refers to the insertion of parts of a musical score into a given text as not “the real thing” and as “being a conventional signifier of music” (

Wolf 2018, p. 244). To him, and other scholars in the field, this textual engagement with music is viewed as less complex, because music is mainly represented visually (i.e., the image of the musical score, consisting of staves, notes, etc.) rather than through one of the aforementioned strategies.

In

Emily Petermann’s (

2014)

The Musical Novel, the author concurs with Wolf that musical notation in literature is a “minor” phenomenon, but makes a noteworthy observation on its inclusion:

[I]n contrast to the graphic novel, which consists of both words and images, the typical signs of the foreign medium of music are not materially present, but are only imitated by the text. Though some musical novels include musical notation as epigraphs or other paratextual devices, often quoting from particular pieces, this physical inclusion of musical notation is at most a minor phenomenon.

As Petermann here already indicates, music does not directly appear as a further notation or writing system but more as a physical ‘image’ that in turn evokes the system of musical notation and therewith also that of music. It is my contention that this, too, must be seen as an

evocation as it references music in the medium of literature. A phenomenon that veers between what

Irina O. Rajewsky (

2002, pp. 87–94;

2005, pp. 52–53) refers to as

media combination and

media reference, the literary text is still the dominant medium but refers to the target medium of music by using a media combination (i.e., the insertion of the image of a musical score into a text). At the same time, this insertion can also be thought of as an intermedial reference (i.e., the score’s inclusion of a title or lyrics, especially including different fonts, handwriting, etc.) and therefore must already be seen as operating on multiple levels of signification. It here becomes clear that musical scores in literary texts have more potential than hitherto has been assumed.

While these occurrences are therefore generally referred to as border phenomena in word–music experimentation, Florian Trabert convincingly argues that similar strategies have a long tradition in the German literature of the 18th and 19th centuries. He cites the first version of

Goethe’s (

1795–1796)

Wilhelm Meisters Lehrjahre as a prime example, which included songs with complete musical notation before this practice became obsolete (

Trabert 2011, pp. 137–38).

4 Thus, far from ‘occasional’ occurrences of this type of intermediality, further examples range from 19th century author

George Egerton’s (

1893–1894) “Discords” (from

Keynotes and Discords) to the Modernist fiction of

Hope Mirrlees’s (

1919)

Paris. A Poem,

Arthur Schnitzler’s (

1924)

Fräulein Else or James Joyce’s Ulysses (1922/

Joyce 1986) and

Finnegans Wake (1939/

Joyce 1992b) to postmodern and contemporary fiction such as

Ingeborg Bachmann’s (

1971)

Malina,

Richard Powers’s (

1991)

Gold Bug Variations5 or

Hartmut Lange’s (

1996) “Die Postwurfsendung”.

The previous has not only established the historically common presence of musical notation in literature but has also situated this phenomenon within the theory of intermediality, which largely views it as an ‘image’ in literary texts that may work as a referential evocation of another medium, namely music. What remains hitherto unchartered are phenomena when characters in a specific text—musicians and non-musicians alike—comment in various ways on details of a musical score, i.e., by using textual strategies. It is here that notational ekphrasis must be situated, as a textual evocation of the system of music by describing its notational system with words. Or, put simply, ‘words on a page’ refer to ‘notes on a page’ with varying degrees of concreteness and imaginary content. But what is at stake when referring to this ‘other’ system? What dimensions do both writing and notation share, and what sets them apart? What effects is the literary medium endowed with when representing musical notation in such an ekphrastic manner?

2. Musical Notation and Ekphrasis

A score usually consists of various graphic and linguistic elements which can be

evoked in literary texts. Apart from a text that is set to music (i.e., a

Lied, aria or other vocal compositions), as well as its general paratext (i.e., the title of any composition), instructions that regard the instrumentation, the performance or its dynamics, such as

pianissimo or

mezzoforte, commonly abbreviated with ‘pp’ or ‘mf’, may be subsumed under this category (see also

Trabert 2011, pp. 135–36). There are also a variety of numbers (e.g., rhythm and time signatures), symbols (e.g., key signatures with sharp and flat accidentals) and ‘graphic’ elements present in musical scores. The graphic elements of modern musical notation include horizontal lines of a stave, clef, notes, ledger lines and repeat signs in addition to information about tempo, time signature, dynamics and instrumentation. The tones to be played are depicted in the form of notes that are conventionally read from left to right. The different note durations are represented by their varying note shapes or values (as e.g., crotchets or quavers), while their pitches are defined by their vertical position on the stave. These graphic elements make up the distinct visual appearance of musical notation and at the same time set it apart from the inscription of language. A discussion of the effects and practices of musical notation within literature make for a short excursion into the discourse of writing itself.

Writing is a cultural technique that consists of activities such as drafting and composition while also bearing witness to thought processes of scholarly and artistic work. As Sybille Krämer points out, any writing system—be it literature or music—opens a scope for creative exploration; we not only read the values inscribed therein but engage with the overall surface writing itself creates (

Krämer 2020, p. 72). This may, in turn, also explain the frequent

evocation of parts of musical scores in literature. During the 1960s, critical debates surrounding writing centered on the acoustic dimension of literature. This is not only true for literary philology but also for the then upcoming field of media theory. At the same time, new philosophic and semiotic approaches—such as those by Jacques Derrida and Nelson Goodman—entirely disavowed the Saussurean paradigm that writing is merely ‘phonographic’, namely inscribed language (see

Derrida [1967] 1997).

6 What the discourse on writing inherits from this

linguistic turn is a differentiated attention to the relationship between language and writing in the first place. In the confrontational coupling of

iconic and

linguistic turn, writing is characterized by a hybridization of the discursive and the iconic, which a priori undermines the supposed “disjointness” of the symbolic orders of the word and the image (see

Goodman 1969).

7 An important starting point for many theoretical approaches in this vein was

Nelson Goodman’s (

1969) fundamental semiotic study

Languages of Art: An Approach to a Theory of Symbols:

The symbol scheme of every notational system is notational, but not every symbol system with a notational scheme is a notational system. What distinguishes the notational systems from the others are certain features of the relationship obtaining between notational scheme and application. “Notation” is commonly used indifferently as short for either “notational scheme” or “notational system”, and for brevity I shall often take advantage of this convenient vacillation where the context precludes confusion.

Approaches such as Goodman’s show that the discourse on notational systems has profited from approaches to writing itself. As such, musical notation cannot be afforded for by viewing it as a mere byproduct of the inscription of a given cultural practice. Instead, its visual dimension and specific iconicity need to be accounted for. This discursive shift, in turn, not only sheds new light on the history of musical notation but also on the cultural technique of inscribing sound altogether while at the same time delimiting it from a former, singular, ‘phonographic’ function (

Celestini et al. 2020, p. 25). In the following, I wish to show that literary texts focus on many of the mentioned specific visual traits of musical notation and their specific semiotics. In referring to this other writing system by representational means, the affordances of both media and their respective systems of inscription are negotiated.

Notational ekphrasis is therefore not just an interesting phenomenon but highlights the potential of ekphrasis as a meta-medium, (a) overtly in the short stories by Katherine Mansfield and Vladimir Nabokov and (b) covertly in “String Quartet” by Virginia Woolf, as shall be showcased in the following.

3. Overt Notational Ekphrasis

A first, simple example of overt

notational ekphrasis can be found in Katherine Mansfield’s short story “The Wind Blows” (1915/1921). The story uses the setting of a music lesson to render seemingly ineffable and indeterminate feelings of the protagonist towards her piano teacher, Mr. Bullen. During the lesson, the score seems to move and morph in front of the protagonist’s eyes as the narrator describes “crotchets and quavers […] dancing up and down the stave like little black boys on a fence. Why is he so… She will not cry—she has nothing to cry about” (pp. 140–41, original ellipsis). The described “crotchets and quavers” clearly indicate a musical score that, however, remains unnamed and therefore does not constitute a referential but semantic rendering of musical notation, akin to

thematization.

8 The quarter notes and eighth notes located on the stave of the musical score are likened to “little black boys on a fence” and construct a simple visual analogy that is marginally racist.

9 So, what about these ekphrastic descriptions of the musical score? What understanding of music do they suggest?

In “Ekphrasis and Representation”, James Heffernan defines ekphrasis as “the verbal representation of graphic representation” (

Heffernan 1991, p. 299). The upshot of this albeit simple definition is that it excludes the possibility of the term being used to denote the representation of one text by another. Heffernan instead posits that ekphrasis “differs from both iconicity and pictorialism because it explicitly represents representation itself. What ekphrasis represents in words, therefore, must itself be representational” (

Heffernan 1991, p. 300). The examples of

notational ekphrasis discussed above highlight these representational aspects. Mansfield’s protagonist sees the musical notation as representative of human bodies (“black boys”) that seem to move (“dancing”) on an object (“fence”). The musical score here transcends its phonographic function and instead endows the notation system with a visual dimension that does not seem to directly correspond to the music (“Beethoven”) or its inscribed values (timbre, rhythm, key, etc.). The bodies, for instance, are not moving in one direction to denote an ascending or descending progression but indeterminately ‘dance’ “up and down the stave”. While the protagonist’s visual imagination can be justified as her being ‘playful’ or simply ‘Child-like’ (she also ‘hears’ “little drums” in the minor movement of the Beethoven piece she practices on piano), it nevertheless shows a dimension of musical notation that sets it apart from the inscribed sound it is supposed to encode; the protagonist knows what the notation means in a musically ‘sound’ sense but nevertheless endows it with a secondary, visual perception. This not only suggests a dormant, representational potential of the musical score but one which relies upon the individual reader or viewer to discover. The purely phonographic process of decoding/encoding of notation systems is hereby subverted, and the musical notation is subsequently expounded as a primarily visual spectacle. Moreover, the aspect of ‘characters’ as part of any system of inscription is here taken literally to represent human-like characters, playfully engaging with the writing process itself.

A second exemplary instance of

notational ekphrasis can be found in Vladimir Nabokov’s short story “Music” (1932/

Nabokov 2006). The story is set at an elaborate dinner party at which the pianist Wolf begins to play: “The entrance hall overflowed with coats of both sexes; from the drawing room came a rapid succession of piano notes” (p. 332). Ironically, the story’s protagonist cannot relate well to music:

To Victor any music he did not know—and all he knew was a dozen conventional tunes—could be likened to the patter of a conversation in a strange tongue: in vain you strive to define at least the limits of the words, but everything slips and merges, so that the laggard ear begins to feel boredom.

(pp. 332–33)

Nabokov here chooses a protagonist whose experience and appreciation of music is limited, especially when it comes to technically advanced musical pieces. This is reminiscent of James Joyce’s protagonist Gabriel Conroy in the short story “The Dead” from Dubliners (1916/

Joyce 1992a). Although he “liked music” he cannot listen to the “Academy Piece” being played on the piano, as it has “no melody” for him but instead boasts “runs and difficult passages” (p. 187). Victor’s similar position in “Music” is reaffirmed at the end of the story when he is confronted by Boke: “‘You know, you looked so bored I felt sorry for you. Is it possible that you are so completely indifferent to it?’ ‘Why, no. I wasn’t bored,’ Victor answered awkwardly. ‘It’s just that I have no ear for music, and that makes me a poor judge’” (pp. 336–37). Whether or not Boke has more expertise never becomes clear but his rather indeterminate sentiment regarding the actual title of the piece indicates at least a familiarity with ‘academy pieces’ in general. When asked by Victor what he thinks Wolf played, Boke answers sporadically: “‘A Maiden’s Prayer’, or the ‘Kreutzer Sonata’. Whatever you will” (p. 337). Although the story lacks a concrete

evocation of music, as the piece remains unidentified, some possibilities are mentioned in the text that refer to instrumental piano music which may be seen in the vein of the typical ‘academy piece’ as in Joyce’s “The Dead”.

What is made explicit is that the piano piece seems complex and in need of Wolf’s professional playing, with the described imagery of the score matching the fast-paced rendition, a fact which is also affirmed by the general appearance of the “performer’s wife” who follows the score concentratedly, “her mouth half open, her eyes blinking fast” (p. 332). As the narration announces the moment of turning the page in the present as “now she has turned it”, the temporal dimension of the music and its fast dynamics are overtly emphasized. In a similar manner, the speed of the performance and music is referred to in a passage earlier on: “At one point his wife got ahead of him; he arrested the page with an instant slap of his open left palm, then with incredible speed himself flipped it over, and already both hands were fiercely kneading the compliant keyboard again” (p. 333). During the performance of the imagined piece, Victor manages to get an ever so brief glance at the musical score: “A black forest of ascending notes, a slope, a gap, then a separate group of little trapezists in flight” (p. 332). It is impossible for Victor to get any indication of what piece of music this is by a fleeting glance, especially since he does not have an ear or other sense for it. At the same time, the visual analogies of the score bear resemblances to natural imagery, foregrounding a “black forest” and a “slope” before moving onto comparing the separate notes to humans as “little trapezists in flight”. The only other instance in the narrative when musical notes are compared to humans comes towards the end of the story when “people, looking against the snow like black quarter notes, were creeping out into the streets” in “different marching groups” (p. 457). But the former identification of the notes as “trapezists” necessarily points to them being bound by a beam into a group of eighth notes, indicating a rapid succession of tones. This is moreover foreshadowed in the fact that a notable multitude of notes “ascend” on a relatively small space of the page (“black forest of ascending notes”), creating a visually noticeable “gap”—in form of the “slope”—in between. The fact that this visual perception does not follow an internal logic, such as the dancing boys on a fence in Mansfield’s “Wind Blows”, highlights a further aspect of musical notation sketched above: Nelson Goodman’s notions of both semantic

disjointness and

discreteness of inscriptions, which

Sybille Krämer (

2020, pp. 67–86) recently made operable for a reevaluation of musical notation.

When characters appear in any notation system, they follow a discrete arrangement, meaning that a written single character (token) must be unambiguously identifiable as belonging to a certain class of characters (type). Moreover, between two single characters there is a gap, an intermediate space, in which no further character in the sense of gradual transitions can be found. Without spaces and gaps, fonts are not possible; this makes them literally ‘printable’ (

Krämer 2020, pp. 70–71). Following Goodman via Krämer, notation systems are organized not only spatially, but rather ‘interspatially’, which not only makes them prototypical versions of the digital but also distinguishes them from the analog image. For, in a painting, even a white patch of unpainted canvas is usually seen as part of an image, not as part of its background (

Krämer 2020, p. 71).

Transferring these observations onto Victor’s rendering of the musical score, it is noticeable that the two discrete ‘characters’—the “black forest” on the one, and the “little trapezists” on the other hand—do not belong to the same discrete type but are represented as disjointed tokens. This ‘disjointness’ is moreover emphasized visually as their appearance is marked by an intermediate space: “a slope, a gap”. Thus, he comes to view the gap within the score first as a representational image and only then as an interspatial feature of the notation system. Victor’s image-logic thus relays—if ever so brief—the representational potential of the score back to the internal logic of the notation system itself. He already leaves the realm of ekphrastic representation when referring to the “black forest [as consisting] of ascending notes”. However, the adverb “then” appears right after noting the “gap”, marking not only a succession of images but also referring to the act of reading the notation system from left to right, making it veer indeterminately between ekphrastic representation and phonographic inscription. While Victor may not be musical or indeed able to read a musical score, he is nevertheless capable of attempting to ‘read’ the score by the sheer acquired, acculturated logic of notation systems, noticing both disjointed and discrete characters of the score together with its interspatial quality that showcases its fleeting nature of encoding/decoding.

The two examples which have now been framed by a larger discussion of musical notation offer remarkable but also puzzling insights. Mansfield’s text expounds music primarily as a visual spectacle and thus emphasizes the dormant representational potential inherent in musical scores even for a trained musician. Nabokov’s Victor, on the other hand, is unable to penetrate the semiotics of the score but nevertheless ‘reads’ its latent iconicity as a system of inscription. In both cases, ‘characters’ as graphic elements and interspatial qualities of the score are highlighted, negotiating the fleeting nature of writing and reading processes. While it can be said that the score is present in both stories as overt intermediality, it must be maintained that it is thematized, as there is no direct referent to the score present while its characteristics are used to generally ‘charge’ the text with musical content. As the previous discussion has shown, larger intersemiotic dynamics are at play within these thematizations, revealing a meta-aesthetic potential of notational ekphrasis, which was here looked at as an overt intermedial phenomenon on the level of thematization. The following therefore will deal with an example of a covert ekphrastic imitation of the musical score.

4. Covert Notational Ekphrasis

Virginia

Woolf’s (

1921) “The String Quartet” presents a further interesting example of

notational ekphrasis, albeit in a covert form. In general, the setting of the story can be described as a visit to a concert in London probably around the year in which it was published. A narrator describes in both omniscient and stream-of-consciousness fashion the selected conversations, as well as sounds and sights, surrounding the concert, seemingly culminating in a verbal rendering of the music itself. The story has generated a mass of critical responses of which I will only focus on ones that suggest possible analogies for the described music or discuss its musical nature.

Alex Aronson (

1980, p. 30), in

Music and the Novel, contends that Woolf’s short story seeks to reproduce the effects of a Mozart Quintet upon the reader and is an early example in her oeuvre that “refers to the virtually unrestricted expressiveness of music as contrasted to the limiting syntactical speech patterns employed by writers attempting to render emotions which elude the dictionary meaning of words”. At the same time, Avrom Fleishman’s “Forms of the Woolfian Short Story” sees the story as unmistakably a formal game, suggesting possible structural analogies to music that are not wholly unproblematic (

Fleishman 1980, p. 67; see also

Wolf 1999, p. 154). Kuo Chia-chen mentions that “[s]ince as early as ‘Street Music’ (1905), ‘The Opera’ (1906), and ‘Impressions at Bayreuth’ (1909), Woolf’s writing has dealt with music” and that she saw her work intrinsically influenced by it. In one of her letters, she maintains that “‘[i]ts [sic] odd, for I’m not regularly musical, but I always think of my books as music before I write them’” (qtd. in

Kuo 2016). In addition, Emilé Crapoulet’s article on “Music in Virginia Woolf’s ‘String Quartet’” opens with Woolf’s own assertion from a diary entry that “‘its [sic] music I want; to stimulate & suggest’” (qtd. in

Crapoulet 2008). The links between Woolf’s writing and music are therefore manifold. But which music does she wish to “suggest” in her short story in the first place? This will be important to determine in order to make a case for

covert notational ekphrasis.

Apart from an obscure reference in the story to “that’s an early Mozart, of course” (

Woolf 1921, p. 29), the music is never clearly named or referenced. Werner Wolf discusses this problem at length, concluding that he is “unable to find a Mozart quartet obeying both this condition and fitting exactly into the textual suggestions of Woolf’s story, though there seem to be some remarkable parallels to the popular Divertimento K. 138 in F major” (

Wolf 1999, p. 152). Commentators, such as Peter Jacobs, however, see a diary entry of Woolf as pointing towards a possible musical source:

At least one short story deserves our attention in this context. In early March 1920 Virginia Woolf went to a concert at George Booth’s house (where among other pieces a Schubert quintet was played) “to take notes for [her] story” […]. The result probably was “The String Quartet,” the only short story in which the overall presence of music is thematically important.

Chia-chen affirms this and agrees that “her short story ‘The String Quartet’ was inspired by the Schubert piano quintet to which she listened in Campden Hill, on 9 March 1920” (Woolf, Diary v.2 24, qtd. in

Kuo 2016). Crapoulet goes even further by asserting that “no reader of this story would have been surprised or shocked if, for example, Schubert’s ‘Trout’ Quintet had been on the programme” because it “is in fact the real piece behind the story, the piece which obviously provided Woolf with the idea of the fish and the river narrative. […]. The references to ‘spotted fish’ can only have been suggested to Woolf by the title of the Schubert ‘Trout’ Quintet she heard in Campden Hill” (

Crapoulet 2008).

To offer a different reading of Woolf’s musico-literary narrative in the vein of covert

notational ekphrasis, it is necessary to quote the passages describing the beginning of the concert at length:

Flourish, spring, burgeon, burst! The pear tree on the top of the mountain. Fountains jet; drops descend. But the waters of the Rhone flow swift and deep, race under the arches, and sweep the trailing water leaves, washing shadows over the silver fish, the spotted fish rushed down by the swift waters, now swept into an eddy where—it’s difficult this—conglomeration of fish all in a pool; leaping, splashing, scraping sharp fins; and such a boil of current that the yellow pebbles are churned round and round, round and round—free now, rushing downwards, or even somehow ascending in exquisite spirals into the air; curled like thin shavings from under a plane; up and up… How lovely goodness is in those who, stepping lightly, go smiling through the world! Also in jolly old fishwives, squatted under arches, obscene old women, how deeply they laugh and shake and rollick, when they walk, from side to side, hum, hah!

“That’s an early Mozart, of course—”

A common observation of this passage would be that the effects created here by the text seem to be an

imitation of either music or its experiential content. This could be described along the lines of

Werner Wolf’s (

1999, pp. 57–67) term

imaginary content analogies. While the employment of natural imagery in order to describe musical perception exhibits a Romantic topos, it reaches a climax in Woolf’s text; the sheer magnitude of images create a dense web of possible interrelations. Overall, these content analogies highlight a spontaneous emergence (“burst”, “now”), while the instrumental music described seems to dynamically move and revolve around itself, ascending and descending in a flow of images (“leaping”, “round”, “rushing downstairs”, “ascending”, “up and up”). The emotive qualities of this perceptive process are at the same time positively connoted (“lovely goodness”, “go smiling through the world”, “jolly old fishwives […] laugh and shake and rollick”). The imagery stages musical experience as a dynamic, emergent action which seems akin to emotive processes at the moment of perception. Since the lexemes in use all constitute the isotopy of

nature, the imagery stems from a fixed order of semantic fields, stressing a general programmatic ‘expressiveness’ rather than actual perception.

While the described imaginary content analogies may explain most commentators’ link between this text and Schubert’s programmatic ‘Trout’ quintet, it does not account for many unexpected representations and statements being made therein. A few images remain outside of the semantic fields conjured by the trout-themed music; these entail “the pear tree on top of the mountain” or the repetition of “arches”, such as in the “jolly old fishwives, squatted under arches” who “deeply […] laugh and shake and rollick”. Moreover, there seem to be meta-aesthetic comments referring to an experience outside of purely aural perception, such as “it’s difficult this” or “rushing downwards, or even somehow ascending”. How can these be accounted for?

Taking into account James Heffernan’s simple differentiation between ekphrasis, iconicity and pictorialism (

Heffernan 1991, pp. 299–300), it can be argued that pictorialism may be useful when looking at texts aiming to represent purely graphic notation systems.

10 Iconicity, when understood in the sense of Charles Saunders Pierce, as a purely semiotic category, quickly loses traction for a discussion of musical notation or indeed

notational ekphrasis, as notes on a stave do not necessarily ‘point’ towards something in the traditional sense of iconicity. But when seen outside of the semiotic realm and understood within the visual arts as displaying an internal visual logic of its own, iconicity becomes a productive category for a discussion of musical scores as they too exhibit strategies that can be deemed genuinely iconic (

Celestini et al. 2020, p. 28). If there is indeed an inherent logic of images that goes beyond mere signification, then this is to be found in the

iconic turn, which Gottfried Boehm posited towards the

linguistic turn. As Boehm points out, the

iconic turn reinterprets iconicity to be defined as a peculiar way of producing meaning out of the image-logic itself, by way of ‘showing’. Showing is here not primarily considered a semiotic concept but rather designates what cannot be said through language (

Celestini et al. 2020, pp. 26–27).

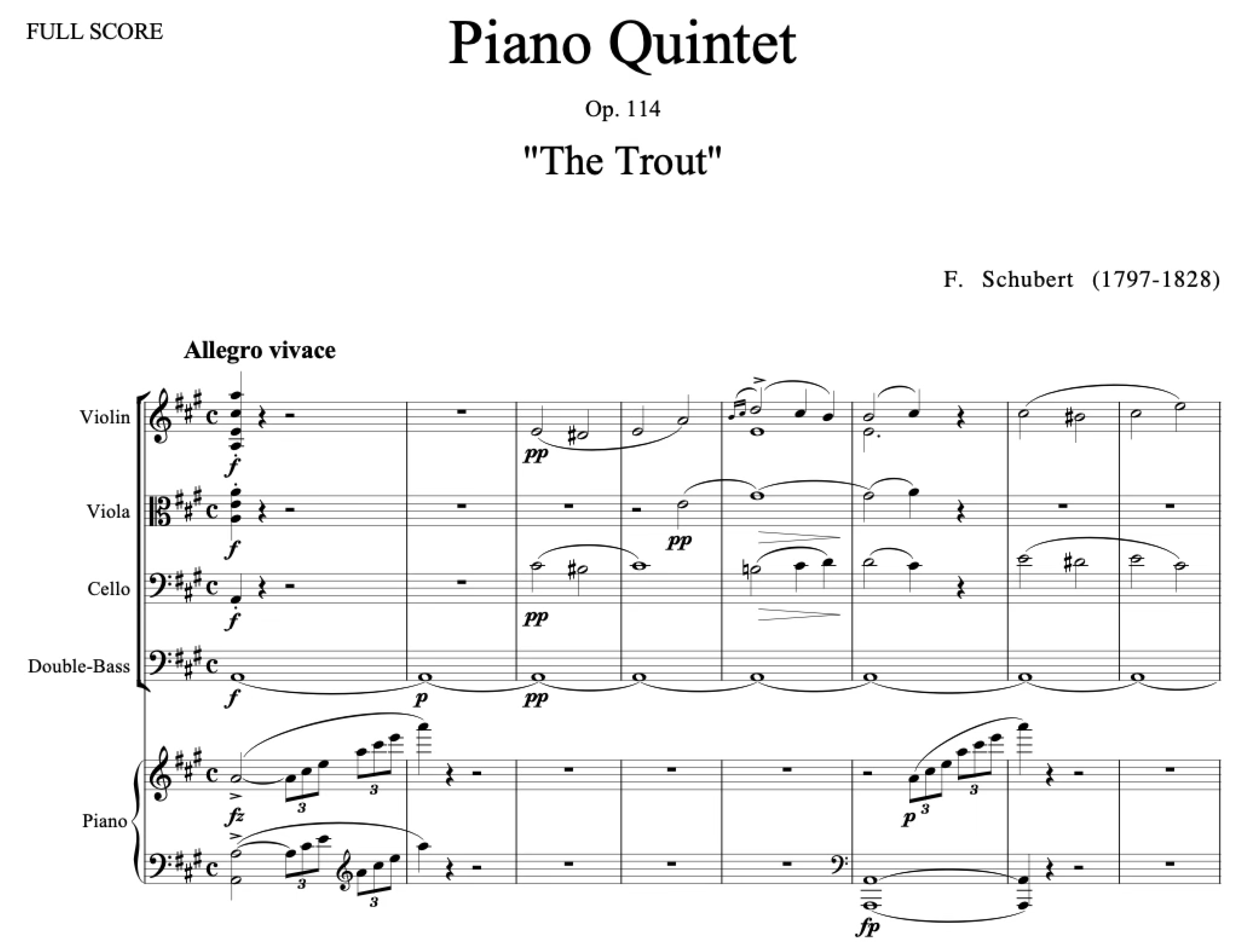

Looking at the score for Schubert’s

Piano Quintet Opus D667 (post. Op. 114) in A major suggests that “

Flourish, spring, burgeon, burst” may well refer to the simultaneous entry of Violin, Viola, Cello and Double Bass – all marked by “f” for

forte – while the “

pear tree on top of the mountain” points towards the iconicity of the separate piano roll in the lower part of the score – marked in the double bass with “p” for “piano” (see

Figure 1):

After an ascension of six notes in two eighth note triplets, the piano roll begun in the first measure culminates in a high A quarter note with a downward stem in measure two. This could be seen as an iconic representation of a ‘tree’ on top of a ‘mountain’—if the neck were seen as a trunk with the note as the crown ‘standing on top’ of an ascension of notes, which in turn could resemble a mountain (see

Figure 2):

Moreover, if Woolf had a chance to look at the score perhaps the many repetitions of “f” and “p” could explain the source for “flourish” and “pear”? The latter of which stem from the double bass section but are visually situated just above the ‘pear tree’ of the piano roll in measure two. This is furthermore reinforced in the repetition during measure six, when the dynamic for the piano roll is again marked as “p” (for “piano”) and when con-sidering that a note with a downward stem can also be seen to point towards the letter ‘p’ as in “pear” (see

Figure 3):

Seen from this vantage point as forming its own textual–visual language and logic, the text’s numerous mentioning of “arches” and the “jolly old fish wives, squatted under arches”, that “deeply […] laugh and shake and rollick”, could be seen as pointing to the bass chords of the piano in measures six to seven: The notes of the chords are vertically closer together with lines in between making them seem compressed or “squatted”. The two chords are furthermore tied from one bar to the next by what is also referred to as ‘arches’. This may also explain why the text refers to them as walking “from side to side, hum, hah!” (

Woolf 1921, p. 75).

These observations are of course only possibilities, but it seems odd to think of a writer such as Virginia Woolf, whose involvement with the arts—especially music—has been well documented in the past decades, to not also be interested in the notational sys-tem of music. If the idea to the story originated by witnessing a Schubert piece being played as part of a private event, there would have been ample occasions to peruse the musical score. Even a brief glance of the first two pages would have been sufficient to draw up simple textual parallels to the here proposed visual potential of the musical score. Following these arguments, then, it seems that Woolf’s text enables a twofold operation: It sets up analogies that stress a programmatic expressiveness like the supposed source of and inspiration for the story, Schubert’s ‘Trout’ quintet. At the same time, however, elements of its score appear as part of the imaginary content analogies in form of covert notational ekphrasis that endow both language and the notational system of music with an iconic logic of their own, signifying outside of their respective semiotic systems.