Abstract

Lord Byron’s life and poetic works have inspired musical compositions across genres even during his lifetime. The English author’s fictional characters and themes impressed nineteenth-century European composers, especially since his Byronic heroes were often conflated with their creators’ own melancholy and revolutionary personas. In contrast to Byron-inspired songs and operas, instrumental programme music has raised doubts towards a direct correlation with its poetic sources. While epigraphs help direct listeners to specific ideas, their absence has prompted dismissals of intermedial relationships, even those proposed by the composers themselves. This essay explores major connections between Hector Berlioz’s Harold in Italy, a Symphony in Four Parts with Viola Obbligato (premiered 1834), and Byron’s semi-autobiographical narrative poem Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage: A Romaunt (published 1812–1818). Although Berlioz’s titles and memoirs partially identify Byron’s Childe Harold as his inspiration, other references, including his visits to the Abruzzi mountains, his fascination with Italian folk music, his reuse of earlier material, and his reflections on brigands and solitude, have fuelled ongoing debates about the work’s programmatic content. Combining historical-biographical research, melopoetics, and musical semiotics, this essay clarifies how indefinite elements were transmitted from poetic source to musical target. Particular focus is placed on the “Harold theme”, which functions as a Byronic microcosm: a structural, thematic, and gestural condensation of Byron’s poem into music. Observing the interactions between microcosmic motifs and macrocosmic forms in Berlioz’s symphony and their poetic analogues, this study offers a new reading of how Byron’s legacy is encoded in musical terms.

1. Introduction: Byron’s Reception Among European Musicians

1.1. Intermediality and Context

Music production based on Lord Byron’s life and writing reached its peak between 1830 and 1890 in Europe. A significant factor was Byron’s passing away in 1824 during his support of the Hellenic War of Independence. European composers of the Age of Revolution found inspiration in Byron’s melancholy yet defiant figure. This essay offers the argument that Hector Berlioz’s Harold in Italy, a Symphony in Four Parts with Viola Obbligato (Berlioz 1900, heareafter HII), is more than a musical homage to Byron’s poem Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage: A Romaunt (Byron 1981–1993a, hereafter CHP). Despite the difference in medium, Berlioz’s work integrates Byronic themes of melancholy, wandering, revolutionary disillusionment, and cynicism at both structural and emotional levels. Byron’s narrative poem functioned as a major literary source and extra-musical programme for Berlioz’s work.

Unlike song lyrics or opera, programme music “purports to carry its narrative meaning within itself” (Scruton 2001). Extra-musical programmes, stories or ideas referenced in titles or programme notes often derive from literature, nature, or visual arts (Kregor 2015, p. 5). In instrumental music, such as programme music, a programme guides interpretation by linking the music to specific ideas or moods: “‘to the poetical idea of the whole or to a particular part of it’” (Scruton 2001). In the absence of explicit references to verse lines in epigraphs, however, composers’ claims of literary influence were often dismissed or reduced to general mood-setting, even when documented in advertisements, letters, or memoirs. As a result, scholarly discussions of HII tend to treat its poetic programme only superficially, often rejecting substantial intermedial links between the music and Byron’s text.

Byron’s CHP is a long narrative poem in four Cantos that fuses old and new forms. Written in Spenserian stanzas, nine lines written in iambic pentameter with an ABABBCBCC rhyme scheme, concluding in a twelve-syllable French alexandrine line, the poem follows the aimless travels of a Childe Harold, hinting at a knightly quest. His physical journey parallels an internal, introspective one, marked by shifts in mood and attitude. Harold explores the condition of self-imposed exile while expressing revolutionary ideals. His European travels become opportunities to reflect on political, economic, historical, and folkloric events and their effect on humanity. Despite abundant descriptions of beautiful landscapes, cultures, and historical sites, Harold remains detached and unimpressed. Canto III of CHP highlights the aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars, portraying the melancholy, solitary pilgrim as disenchanted but not without cynical commentary. Canto IV, set in Venice, observes cultural and artistic achievements alongside nature and freedom, contrasting them with the political climate. Byron’s contemporaries conflated the poet with his fictional protagonist, the archetype of the Byronic hero: a melancholy, love-stricken noble wanderer. Yet the character is distinct from its author; Harold isolates himself in nature, eschewing community, causes, and conventions. Unlike the classical hero engaged in strength-proving feats, the Byronic hero wanders in introspection. Byron, by contrast, engaged in public life.

1.2. The Byronic Hero and Childe Harold

The Byronic hero is a complex synthesis of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century prototypes: the Child of Nature, Hero of Sensibility, Noble Outlaw, Gothic Villain, Faust, and Prometheus (Thorslev, in Carpenter 2002, p. 46). Emerging from the Romantic hero, the Byronic character carries an added element of dangerous excess. Defined by a troubled conscience, ennui, cynicism, and world-weariness, the Byronic hero exemplifies the Romantic spirit while grappling with exterior and interior dilemmas (Cochran 2006, pp. 249–50). Following Waterloo, heroes of internal conflict replaced those of physical conquest (Liszt and zu Sayn-Wittgenstein 1950, p. 867), as emotions could cause “downfall” (Carpenter 2002, p. 45). Byron’s poetry thus valorises a Romantic hero marked by both bravery and moral ambiguity (Shears [2009] 2016, p. 123). Alienated, melancholy, and supercilious, the Byronic character blurs the boundaries between life and art while modelling resistance to oppression (Cochran 2006, p. 250). Mark Evan Bonds defines the “Romantic hero” with the Napoleonic model of victory:

Byron’s Childe Harold highlights the failure of the Napoleonic Wars to achieve their original ideals, attributing it to conflicting character traits that led to indecisive actions. The antithetical Byronic hero fluctuates among idealism, rebellion, and reform.In spite of the unmistakable reference to the Ninth, Harold does not end with a rousing set of variations, a triumphant march, or a chorale-like theme of triumph. Instead, the “hero” of this work is vanquished. Byron’s Harold is the essence of the Romantic hero: far from Napoleonic, he is withdrawn, contemplative, and isolated from society, a prototypical anti-hero. Harold en Italie is, in effect, Berlioz’s Sinfonia anti-eroica.(Bonds 1992, p. 424)

1.3. Critical Debate on Word-Music Relations

Although Byron’s poetry clearly influenced Berlioz, early critics struggled to identify direct links between the two artistic media. Donald Francis Tovey found it impossible to translate verse into musical terms, attributing this to “Berlioz’s encyclopaedic inattention”, while recognising the potential of extra-musical ideas to function as a “referential background” (Levine 1982, p. 183). Robert Pascall argued that “originality” trumped accuracy, reducing the grand themes of war, nature, and culture “to the picturesque and naïve” (Pascall 1988, p. 129). Byron’s ambivalence towards “nature poetry”, “variously picturesque, realistic, or comic” (Lovell 1966, p. 23), also shapes the musical narrative. Similarly, Bonds resisted identifying “specific parallels with Byron’s poem”, following Glyn Court’s judgement that the programme is not “straightforward [… but rather] tenuous” (Bonds 1992, p. 423). These interpretive challenges have led to diverse readings of Berlioz’s HII: as adaptation, interpretive response, imitation, translation, transmutation, illustration, association, filtered appropriation, fusion, “imaginative musical recreation” (Thomson 2016, p. 36), or even an unrelated autobiographical piece with suggestive headings. The broader debate concerns the programmatic nature of the work and the complexities of word-music relationships.

This essay proposes to expand the view of Byron’s influence on HII, arguing that it goes beyond an allusion in the title to emotional, structural, and symbolic influences. The reference to “Italy” suggests not only CHP but also Byron’s Italian period. Berlioz’s Byronic irony, mixing “conscious detachment” with “extremes of passion”, is compared by David Cairns to the emotional texture of Don Juan [Byron, DJ, 1819, 1858] (Cairns 1989, p. 458). This supports a reading of HII as a composite, direct engagement with Byron’s work.

Jacques Barzun criticised Tovey and others for misunderstanding literary influence in Berlioz, noting “how associations cluster” around “symbols at once sharp and ambiguous enough for infinite reference” (Levine 1982, p. 201, n10). Thomas Austenfeld likewise sees Berlioz’s HII as a “sentimental” “interpretation” of Byron’s text, shaped by Berlioz’s imagination rather than Byron’s cynicism (Austenfeld 1990, p. 94). Yet some scholars do detect cynicism in the music, a view this essay supports at the level of compositional devices and juxtaposition. The analysis in this essay explores to what extent elements of content and form in HII derive from Byron’s CHP and how this intermedial relationship expands the potential of the programme.

2. Intermedial Narrativity: A Methodological Approach

2.1. Intermediality

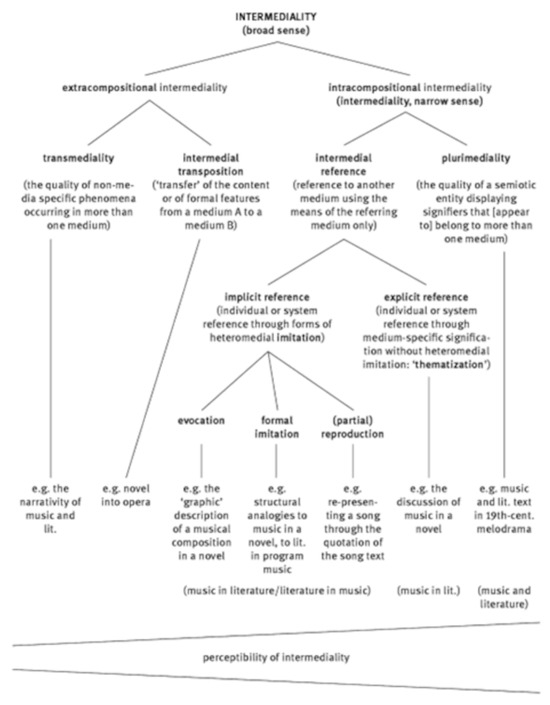

Studying the relationship between two media requires gauging the extent of their interaction, influence and comparability. Intermediality traces the transmission of constituent elements from one art form to another. While intertextuality involves mostly unconscious acts of borrowing, particularly within the same medium, intermediality, a term coined by Friedrich Aage Hansen-Löwe, encompasses both conscious and unconscious processes of transfer across media.

Werner Wolf’s typological diagram (Wolf 2015, pp. 461–74; see Appendix A) provides a framework for analysing programme music inspired by Byron’s poetry. Such works may fit into more than one intermedial category. For example, formal imitation occurs when one medium uses its own specific means to imitate forms from another, despite their differing semiotic codes (verbal or nonverbal). By contrast, transmediality, the least conspicuous form of intermediality, refers to the migration of non-medium-specific elements, such as inferred narratives, that transcend the boundaries of any single medium (Wolf 2015, p. 468).

This study draws on a range of Wolf’s intermedial concepts to investigate how instrumental music can convey the substance of poetry. The analytical method is threefold, incorporating melopoetics and musical semiotics, combined with historical-biographical context. A mixed, intermediate approach enables a nuanced comparison of compositional devices across Byron’s poetry and Berlioz’s music.

2.2. Melopoetics and Underlying Meaning

Because poetry and music share few compositional devices, comparing their sounds and rhythms is key. Ezra Pound defines “Melopoeia [as verse], wherein the words are charged, over and above their plain meaning, with some musical property, which directs the bearing or trend of that meaning” (Eliot 1968, p. 25). Lawrence Kramer extends this, asserting that “the music [of the text…] ‘reads’ a text with a deep structure that the text itself can be said to conceal or resist” (Kramer 1989, p. 167). Kramer’s concept of melopoetics, a musical-literary criticism, derives meaning from linguistic and prosodic patterns in verse. This involves phonetic transcription, rhythmic and phrasal scansion, and semantic analysis to identify patterns of recurrence, combination, and deviation. The scansions employed in this essay follow Derek Attridge’s system (see Appendix B).

Byron’s rhythmic contrasts create semantic and emotional layers that Berlioz may mirror musically. Bernard Beatty argues that Byron’s strategy, despite the seemingly experimental tone, is revealed through the language itself (Beatty 2019, pp. 265–66). Applying melopoetics to Byron’s poem extracts prosodic and phonetic elements and links them to the themes. Analysing melopoetic elements is, therefore, essential to this intermedial comparison with music.

2.3. Musical Semiotics and Narrative Structure

This essay also applies musical semiotics, which studies sign relations in music through topics, gestures, and compositional elements. Following Charles S. Peirce, signs consist of three components: “the object to which a sign refers; the representamen, i.e., the sign itself; and the interpretant”, a mental construct linking the two (Tarasti 2002, p. 10). Peircean terms, iconic, indexical, and symbolic sign functions, replace de Saussurean model of “likeness, causality, or convention” which “may activate an ongoing chain of interpretants” (Cumming 2001). In literary terminology, the relationship between a signifier and a signified, the components of a sign, is either denotative or connotative. In music, iconic signs are gestures that imitate extra-musical phenomena through perceived likeness, for example, ascending arpeggios to express elation or the sublime; indexical signs are conventional or contextual elements akin to rhetorical devices, functioning through cause and effect, such as the persistent use of certain rhythms or keys to signify psychological states; and symbolic signs are arbitrary or culturally specific associations, such as the use of the alla turca topic to evoke exoticism (Cumming 2001).

The musical semiotic approach allows analysis to move beyond harmonic and motivic structures to explore deeper intermedial relationships such as narrative metaphors and ironic tone. The significance of signs in music is often contingent on narrative sequence. Eero Tarasti’s musical semiotic theory provides a system for analysing coherence. Tarasti’s musical semiotic theory aims to identify not only the style markers but also their localisations, characterisations, and deviations. They can be labelled at distinct levels of modality (what they offer the music) and recognised at the level of musical gesture or effect, from the largest to the smallest functional components: “(1) isotopies; (2) spatial, temporal, and actorial categories and their engagement/disengagement; (3) modalities; and (4) semes/phemes” (Tarasti 2002, pp. 61, 194). From this existential approach, I mostly apply what is relevant to the intermediality: the use of thematic isotopies, the interaction among melodies, and the smallest units of meaning and sound, as applicable to the analysis; an example for the “I can” modality occurs when the solo viola plays an improvisation. Musical topics are elements of theme and form based on their formal function in earlier usages (Caplin 2005, p. 114). The combination or superimposition of musical topics is a complex isotopy, or longer semantic particle, meaning a musical narrative.

Moreover, a musical topic becomes a trope upon interacting with other topics and motives that are mismatched, creating semantic tension or transformation (Hatten 2014, p. 515). This interaction opens the possibility of metaphor and parody, among other interpretative layers. Kramer delineates tropes as fluid signs generating many interpretants, or meanings, depending on context, programme, discourse, and historical associations; musical signification becomes more than the sum of its topics (Kramer 2020, pp. 58, 59, 66). Motifs, or semes, as the smallest semantic units, appear within thematic classemes, i.e., contextual frameworks that give them narrative significance (Grabócz 1986, p. 100). Intermedial relationships can therefore be analysed on both microcosmic (motivic, gestural) and macrocosmic (structural, narrative) levels.

The present essay integrates contextual inferencing, melopoetics, musical semiotics, and structural musical analysis to enable a thorough comparison between Byron’s CHP and Berlioz’s HII. The essay will identify narrative gestures in both works and compare their function, allowing an examination of the direct and substantive influence of Byron’s poem over the music. As a result of this approach, intermedial relations can be examined on various structural levels, microcosmic and macrocosmic.

3. Berlioz’s Musical, Political, and Literary Influences

3.1. Musical and Byronic Mimesis

Since HII premiered on the 23 November 1834 in Paris, it commemorates the tenth anniversary of Byron’s death and Beethoven’s Ninth Choral Symphony. The supposition that the influence of the musical tradition, Beethoven in particular, on Berlioz’s HII is greater than that of the poetic programme is inferred from its unconventionality of genre, rather than from form or content. It is symphonically labelled music with a soloist along with an alienation of the soloist and theme (Bonds 1992, pp. 417–18). Within the symphonic tradition, composers were expected to surpass or “transcend” the frightening musical giant, as Berlioz calls Beethoven, “yet maintain the same degree of reflection that Beethoven had reached” in the symphony (Bonds 1992, p. 450). Symphony movements usually follow the prescribed order of movements: sonata—slow—scherzo or minuet—fast. On the other hand, in HII the order is only the surface, which this essay explains in alternative ways. Moreover, scholars question whether Berlioz’s HII is an example of artificially copying or imitating Beethoven’s works that overrode Berlioz’s creativity (Bonds 1992, p. 418). Mostly self-taught, Berlioz did learn musical composition by copying works of great composers, especially Carl von Weber, Christoph Willibald von Gluck, and Ludwig van Beethoven, at the Paris Conservatory library (Berlioz 2002, pp. 14–15; Bloom 1998, pp. 20, 24). Bonds argues, nevertheless, that Berlioz did not copy but heavily responded to Beethoven’s symphonies by alluding to most of them, Nos 1, 3, 5, 6, 7, 9 (Bonds 1992, pp. 420–24).

Berlioz’s compositional techniques were certainly influenced by Beethoven’s, whose late works were unconventional. Franz Liszt observes that Berlioz did not, however, imitate Beethoven per se but that he sought “the germs of artistic development”, considering Berlioz a “vocational” musical genius and his HII instructive in its unconventionality; indeed, Liszt opposes the idea of mere “imitation[…]” of musical forefathers, “the old masters”, and their “exhausted” “forms” (Liszt and zu Sayn-Wittgenstein 1950, p. 869). Danuta Mirka explains that the “affective power” of music is attributed to musical “motion” that is linked to “emotion” in “‘intervals’”, “rhythmic patterns”, and “qualities of keys”, as well as the listener’s “temperament” (Mirka 2014, pp. 11–12). Berlioz’s work in question goes beyond a mere copying, or reflection of conventional ideals, towards Byronic underpinnings. Mirka distinguishes between “imitation” in music and “mimesis” as a more profound variant: “while fine arts imitate the physical world, music should imitate the world of human passions” in onomatopoeic and more conventional means (Mirka 2014, p. 12). Mimesis is more than sound replication: it reflects the good and the beautiful, induces ethos of a culture, and focuses on “human life—character, passions, deeds”, all for metaphysical aims (Mathiesen 2001), hence not thrice removed from reality like imitation is. Exploiting the “affections” within “the poem” (Liszt and zu Sayn-Wittgenstein 1950, p. 865), the programme of the music inspires listeners to imagine a collaboration with the sources of inspiration because of the symbolically indefinite construction and “[t]he intersection of musical and poetic content” (Kregor 2015, p. 88). Berlioz recruits the Byron programme to overcome the Beethoven-related fear.

3.2. Historical and Political Sources

Berlioz, similar to Byron, rarely followed creative instruction or classical conventions. Whereas the circumstances behind the composition of HII are well known, the aims of a Byronic work remain elusive. Having enjoyed a performance of works by Berlioz, Niccolò Paganini, a famous violinist, offered the talented composer a job in 1833. He entrusted him to compose “the right music” for him to play on his Stradivarius grand viola for his London debut as a violist (Berlioz 2002, p. 215). At first, Berlioz presented his composition as a two-part concerto, “a work for chorus, orchestra, and solo viola, tentatively to be called The Last Moments of Mary Stuart” (Holoman 1989, p. 155), alluding to Friedrich Schiller’s Maria Stuart alongside other pieces from the Wallenstein drama series (Berlioz 2002, p. 290). An uncommon hero, the viola instrument, the cousin of the more primary violin, adequately represents the Queen of Scots with her exilic life and lonesome death for high treason against her captor and cousin, Queen Elizabeth I. The viola suitably represents a leader, such that the English term “viola” and the German term “Bratschgeige”, also “Bratsche” (of brotherhood), both derive from the Italian “viola da braccio”, meaning the violin of the arm (Boyden 2001). When Paganini abandoned the piece for lack of showmanship, Berlioz kept the idea of the viola, symbolic of an unconventional hero such as Mary and Byron’s Harold.

The political influence is multiplied with historical and fictional allusions. In one connection with Childe Harold, when she was leaving France for Scotland, Mary Stuart famously bade the French shores adieu, thinking she would never return, just like Harold (CHP, I, 13, l. 118). Her last moments would have been full of Byronic gloom and agony towards a sense of powerlessness and betrayal. Berlioz would have read that Byron was Scottish on his mother’s side in Thomas Moore’s biography in the Galignani edition, Life of Lord Byron (1830–1831) (Berlioz 1972–1975, 1, p. 293; Byron 1854).1 Moreover, because the “Harold theme” is a self-borrowed theme from the discarded Rob Roy Overture without significant alterations, the reference to Mary Stuart does not seem to be its origin but an association. The allusions link the English, French, Scottish, and Irish historical thrones with Harold and the solo viola in the context of folkloric custom and belief, wars of independence, monarchies, and republican thought.

In addition, the first edition of Berlioz’s HII omits the first movement heading due to a missing first page, which imitates the violent ripping of the Napoleon Buonaparte dedication from Beethoven’s Third “Eroica” Symphony, in E-flat major, as a political retraction. The connection to Napoleon lies in more than the coexistence of opposite sentiments and tendencies. A marching “Napoleon” melody in bb.177–180 is self-borrowed from another abandoned piece from Berlioz’s post-Italian experience, The Return of the Army from Italy H.62/2 (1832), a military symphony in two parts found in his Sketchbook of 1832–1836. Byron and Berlioz express disappointment with Napoleon as a derailed Promethean endeavour, and the torn title page of HII hints at a Beethovenian revocation of a Napoleon dedication. Nevertheless, not only are the characters Byronic, but also the retrieval of previously abandoned themes in HII hints at a Byronic revival of the ideal in a new form.

3.3. Personal Context and Intention

In addition to the symphonic, Berlioz kept the allusion to (illusion of) the concerto genre that Paganini had ordered using a leading soloist. Released from the commission, Berlioz was free to shift emphasis away from genre limitations. The oddities are that the viola is not usually perceived as a soloist but as a harmonic instrument; whereas the concerto is in three, Berlioz’s piece is in four movements, in a parallel way to Byron’s CHP. It is also speculated that the “merging of two forms, a symphony and a concerto” parallels Byron’s solution to the problem of voice in CHP (Carpenter 2002, pp. 41–42). Musicians only knew what it was not: neither a symphony, a concerto, a symphonie concertante, nor a sonata. The genre of Berlioz’s HII was, thus, misleading similar to that of Byron’s CHP. This essay adopts the argument against the application of the sonata form altogether. It helps postulate, instead, that the hybrid genre of concerto, symphony, and programme music constitutes a non-conventional genre closer to a dramatic symphonic poem, in several acts (movements) and scenes (motivic combinations), reconciling the genre, form, and style debates in the reviewed literature. Along with its play with unresolved recapitulations, a burgeoning format among the Romantics, HII presents itself as a complexity beyond genre.

The historical-biographical and literary contexts form multiple layers of the same Byronic heroism in Berlioz’s symphonic piece. Berlioz had been acquainted with Byron’s life and some of his works. Before composing this work, Berlioz had already composed on Byronic topics: Heroic Scene: The Greek Revolution (1826) and The Death of Sardanapalus (1830), the latter of which being his only victorious attempt at the Prix de Rome competitions in Paris, which entailed a two-year stay in Italy. Referring to the direct Byronic influence more conspicuously, Berlioz explains the final plan and title:

My idea was to write a series of orchestral scenes in which the solo viola would be involved, to a greater or lesser extent, like an actual person, retaining the same character throughout. I decided to give it as a setting the poetic impressions recollected from my wanderings in the Abruzzi [mountains, Italy,] and to make it a kind of melancholy dreamer in the style of Byron’s Childe Harold. Hence the title of the symphony, Harold in Italy.(Berlioz 2002, p. 216)

In addition to his explicit literary intentions behind the composition, Berlioz’s own Byronic character is compared to his Harold and Byron’s original protagonist as manifestations of a Romantic anti-hero, or Byronic hero. Aware of Byron’s own long Italian sojourn, Berlioz compares himself and his experiences in Italy with Byron’s and Harold’s. For instance, Sardinian sailors related their encounters with Byron sailing across the Adriatic to the Greek islands, his fancy attire, bacchanal activities, and braving a shipwrecking storm while playing cards; Berlioz unquestionably deemed the tales “in character with the author of Lara” and “Childe Harold” (Berlioz 2002, p. 124). Similar to Byron, Berlioz favoured both the Italian mountain and sea (Berlioz 2002, p. 123). Berlioz visited the church of St Peter in Rome for meditation or reading Byron, especially The Corsair: A Tale (1814), in the confessional; he imagined Byron visiting the church with Countess Guiccioli and gnashed his teeth (Berlioz 2002, p. 148). He lives Byron’s description of the same church that “expand[s]” the “mind” since we observers “dilate | Our spirits to the size of that they contemplate” (CHP, IV, 155, 158). Moreover, giving the viola a soloist role in HII implies a solitary existence like Harold’s. Experiencing isolation in Italy intensified Berlioz’s identification with Byron as it projects onto the character of the solo viola and converges with that of the Byronic hero and the poet.

Berlioz’s approach to the composition was poetically inclined despite autobiographical connections. In the setting of HII, Berlioz merges his own experience of Italy with Byron’s Italian sojourn, which produced Cantos III-IV. Indeed, the Italian stanzas start even before Canto IV: “Italia!” (CHP, III, 110). Berlioz alludes to Byron’s CHP with the name Harold in the title, and he provides programmatic movement headings to his HII to suggest scenes and motifs:

- (1)

- “Harold in the Mountains: Scenes of Melancholy, Happiness, and Joy”, Adagio—Allegro

- (2)

- “Procession of Pilgrims Singing the Evening Hymn”, Allegretto

- (3)

- “Serenade of an Abruzzi-mountaineer to his Sweetheart”, Allegro—Allegretto—Allegro

- (4)

- “The O*g* of Brigands: Reminiscences of the Preceding Scenes”, Allegro.

Although the headings relate to Berlioz’s travels, the analysis will qualify the Byronic associations and focus on the first movement, where the “Harold theme” first appears. Berlioz and his Harold’s experiences of Italian mountains, according to the first movement heading, are thematically connected to Byron’s experience of Swiss mountains, the setting of CHP Canto III and Byron’s location when he wrote it. Berlioz’s HII exhibits Byron’s means of approaching a transcendent experience: mountains, spiritual rites, and unconditional love. Representing the ideals and their pursuit similar to a musical exposition serves to flout their conventional significance and shatter their luring effect on the observer with unconventionally used compositional devices, in line with the romance elements in Byron’s poem.

Berlioz’s first-hand experience of similar scenery and events, including fluctuating mood and religious sentiment, presents added value, just as Byron’s did when writing CHP. The attitude in HII towards mountains changes, just as it does in CHP across the Cantos, from a sense of wonder and respectful awe in Canto I to defiance in Canto III. Of similar function to that of geographies and cultures in CHP, the musical scenes provide contexts or levels of consciousness for reminiscing on or influencing a development of the musical theme. The aspect related more to religion and meditation in HII is more conspicuous in the second movement.

Similar to Byron’s Harold, Berlioz’s Harold finds comfort and joy in contemplating mountains or the world from one throughout the Cantos. Harold gazes at the huge mountainous divides between nations and “pass[es] o’er many a mount sublime” (CHP, I, 32; II, 27, 42, 46; III, 109), compares mountain sizes (CHP, IV, 27, 73, 74), and “climb[s] the many-winding way” to “survey” beauty beneath (CHP, I, 19, 20, 23, 27; II, 25, 41; III, 91; IV, 175). The mountains in CHP, moreover, become metaphorical, such that “mountains are a feeling” and “a part | [o]f me” (CHP, III, 72, 75), and personified as “the joyous Alps” in “mountain-mirth” (CHP, III, 92, 93), hence a double pilgrimage.

Berlioz had planned but not completed writing a dramatic setting called Les Brigands (1833) after Schiller’s Die Räuber. In the French context, however, brigands were not defined as gangsters but as criminals, outlaws, or rebels. This complexity of influences—musical, political, and literary—creates a multidimensional creative space for Berlioz, where personal experience, historical context, and artistic tradition intersect.

4. Revolving Around Harold and Deviating

4.1. Genre Ambiguity and Juxtaposition

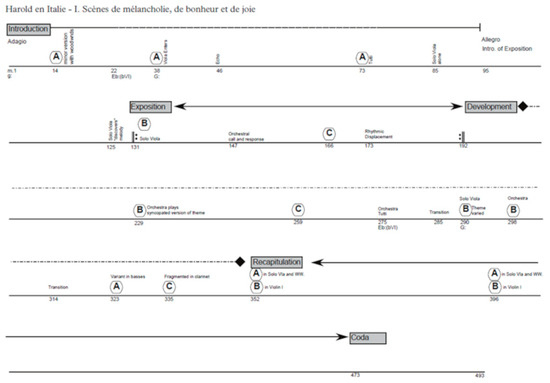

Berlioz’s first movement imitates not only the physical and metaphorical journey but also Byron’s reworking of classical narrative conventions. Musicologists have debated over whether the first movement is in sonata-Allegro form without any consensus over its division or subversive elements. Traditionally, the first movement of an eighteenth-century symphony is composed in binary form, with two main themes: an optional slow introduction, an Allegro exposition, a development, a recapitulation, and a coda (Webster 2001). Berlioz references the symphonic template only to subvert or reinterpret it as the movement unfolds. In this transgressive sonata structure, Berlioz incorporates a primary thematic complex in the Adagio, extends it in the Allegro, and then subjects it to thematic fragmentation, an essential Romantic and Byronic element.

Several scholars have proposed different interpretations of the first movement form. Jonathan Richard Girard divides the first movement of HII into Introduction, Exposition from b.131, Development from b.193, Recapitulation from b.352, and Coda from b.473 (see Appendix C). Girard identifies two introductions: first, an Adagio “double fugue” of two subjects, one of which is the “Harold theme” from b.14 and b.38; and second, a “more traditional” Adagio from b.94b, which “opens the true exposition” from b.131 (Girard 2012, pp. 50, 29, 30).

Cora Palfy proposes a slightly different “sonata schematic”, identifying the primary theme P0 as the Allegro that first appears from b.95 (or b.94b) in G major (see Appendix D). For Palfy, the Exposition (200 bars) consists of an Introduction (bb.1–127), a primary theme (bb.128–147), and a secondary theme (bb.167–200); the Recapitulation (209 bars) includes a primary theme (bb.291–320) and a secondary theme (bb.449–500) (Palfy 2016, p. 188). Nevertheless, Palfy asserts that the failure to resolve the sonata form, through repeating undeveloped themes, “provides an apt representation of the Byronic hero” who cannot resolve past problems (Palfy 2016, pp. 189–90). David Curran offers yet another schematic, locating the Exposition at b.132, with the primary theme as the first Allegro, and the secondary theme beginning in the F major at b.167 [b.166]. Curran treats the other melodic material as either an imposing “Fugue” and “idée fixe” (the unchanging “Harold theme”) or as “fragments” of the primary theme (Curran 2016, p. 63). The motivic or melodic differences among these interpretations may stem from Berlioz’s thematic ambiguity. In allusion to sonata-Allegro form, the so-called themes in the first movement can be understood as melodic variants with underlying unity.

4.2. The Fugato and the Byronic Hero

At the outset of the first movement, Berlioz inserts an imitative contrapuntal passage that alludes to the archaic genre of the fugue within the anomalous beginning of the programme symphony. The term fugato, derived from the fugue, refers to brief passages of fugal imitation (a contrapuntal style surviving from the mediaeval ages) and “to brief passages of fugal imitation within non-fugal movements” (Walker 2001). Unlike a fugue, a fugato features voices in imitation but lacks a full development with repeated modulations. This polyvocal texture symbolises the Byronic hero’s multifaceted pilgrimage. For its “conniving complexity” and “element of sensuousness”, Berlioz preferred the fugato over the classical fugue (Barricelli 1988, p. 260). Berlioz often deployed fugues as a “parody” of academic rigidity and “learnedness” (Walker 2001). Thus, the fugato functions as an apt musical index for the Spenserian stanza and the archaic language with which Byron begins his poem. Indeed, after the dedication and invocation of the muse, the main character is introduced in deliberately archaic diction: “Whilome in Albion’s isle there dwelt a youth” and “Childe Harold was he hight” (CHP, I, 2, 3). In addition, the Latin root of fugue, fuga, meaning to “flee” or “chase” (Walker 2001), reinforces the indexical signification of the fugato as representing flight. Byron’s Harold is a “sad losel” who has committed “evil deeds” and “a crime”, with no intention of glorifying his actions or clearing his name (CHP, I, 3). The musical introduction thus conveys both the literal flight of Harold and the psychological tension from conscience and society.

4.3. Sounding the Sublime: The Ombra and the Pianto

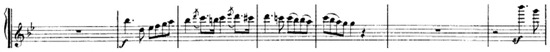

As in the prologue and introduction of the Childe, the music begins in Adagio, a slow tempo, setting an iconic background for the narrative. The lower strings play a tonally ambiguous brooding line in very soft dynamics (pp) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Harold in Italy, Movement 1, bb.1–4, lower strings.

The semiquavers pulsate with accents that imply simple triple metre (3|4) grouped to simulate march beats iconically, indexical of Harold’s physical journey. The slow pace of the fugal subject allows reflection, while the fugato chromatic motion and semitone inflections introduce the ombra topic (previously called Sturm), indexically signifying “a sense of shadowiness and approaching fear” (McClelland 2014, p. 279). Clive McClelland classifies the ombra and the learned style as elements of the sublime in music (McClelland 2014, p. 294). Here, the orchestral ombra line becomes an icon of the waves beneath Harold’s sail, an index of his ambiguous intention, and a symbol of the sublime encounter. Additionally, the rhythm iconically evokes the alexandrine lines of twelve syllables, where double meanings are often exposed, paralleling the poetic texture of Byron’s verse.

The expressive (espressivo) countersubject in tied phrasing (see Figure 2) allows the four bassoon sections, typically a background voice, to emerge as a soloistic commentator. Beginning on Bb3.

Figure 2.

Movement 1, bb.1–4, bassoons.

The descending chromatic motion in bb.3–4 serves as a lament or mourning gesture (Caplin 2005, p. 120), indexically conveying Harold’s melancholy. The falling minor second interval, the Pianto, or Seufzer, topic, iconically and indexically signifies an emotional sigh, first as an icon of weeping and later as “distress, sorrow, lament”, “grief, pain, regret, loss” and yearning (Monelle 2000, pp. 11, 17, 66–67). Employing the middle register of the bassoon (F#2–Bb3) in bb.3–4 iconically reveals the sonorous and expressive side of the Byronic hero. The syncopated notes in bb. 4–5 indexically signal defiance, agitation, and distress, exploiting the upper register, which is indexically associated with a “character” that is “painful, complaining, almost wretched” (Waterhouse 2001). The descending chromatic gesture in the ombra context further associates the bassoons with a cynical commentator. The juxtaposition establishes a narrative irony, aligning suffering with commentary.

The strings respond with the fugal answer, from b.4, on the dominant D major. A more complex division ensues with twelve semiquavers, six quavers, or sextuplets. This rhythmic complexity indexically conveys how Harold’s wandering “through Sin’s long labyrinth” (CHP, I, 5). As woodwind and brass join, a contrapuntal texture unfolds, complementing fear and melancholy. The ombra, the minor mode, the slow motion, and the lamenting chromaticism combine in the first Adagio to reflect, indexically and symbolically, Harold’s melancholy introspection and Romantic irony, resulting in a complex isotopy of cynicism.

4.4. Heroism Questioned, Fragmentation, and Sehnsucht

Similar to Byron’s CHP, Berlioz’s HII questions noble heroism through minor modes and sinister indexes. The second Adagio introduces the “Harold theme” in a Beethovenian heroic style, a full orchestral passage in G minor and a tension-filled atmosphere in bb.14–21 (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Movement 1, bb.15–19, flutes.

The dotted rhythm melody in the woodwind overlaps with the sinister semiquavers of the first Adagio, while the use of the tritone in b.19 suggests diabolical connotations. This A07/b5 chord, functioning as a half-diminished Cm6 (see Figure 3), indexically highlights the sinister undertones of heroism. Fanfares in E-flat, C minor, and A-flat major in woodwind (see Figure 4) alternate with relaxed triplet monotones in G minor, combining traditional heroism with Romantic irony.

Figure 4.

Movement 1, bb.20–24, clarinets, horns I-II (top to bottom).

Horns and trombones emphasise the double-dotted rhythm and new chords in an echo of those introduced in other sections. The French horn (corno), a brass instrument associated with fanfare, hunting, military, and/or pastoral settings, symbolises a non-barbaric battle but also carries associations of failed transcendence. The string tremolos and timpani crescendo roll at bb.35–36, iconic of a thunderclap effect, resolving in G minor in b.36, help transition to the harp and solo viola scene in G major.

The tonal progression suggests an emergence from the second Adagio, highlighting a Byronic revisionist reading. The sublime emerges indexically through extreme contrast or variation, unexpected chords or silence, and textural shifts (Meyer, Leonard B. 1989. In Allanbrook 2010, p. 266). The E-flat chord, in bb.21b–23, as a flattened submediant (bVI) of G major, symbolises a failed Romantic transcendence through the heroism of deeds. Additionally, flat keys are traditional indexes associated with gloom and weakness (Steblin, Rita. 1983. In McClelland 2014, p. 283), further tainting heroism with disappointment.

The abrupt dynamic contrasts in bb.23b–24, from very intensely loud (ff, or fortissimo) to softness (p, or piano), mock the heroic fanfare and return to G minor, reinforcing anti- heroism. The repetitive restarts of the fugato iconically signify Harold’s inability to move on, paralleling the narrative incoherence of Childe Harold. The Sehnsucht topic, or wistful longing, permeates the movement through remote tonalities, nostalgic allusions, the miniature, folkloric textures, and the exotic (Stewart 1984, pp. 139–41). In HII, the musical mountains become an index of Romantic longing for transcendence, echoing CHP.

5. Harold in Motivic Disguise: Isolation and Reflection

5.1. The Shifting Role of the Solo Viola from Soloist to Observer

In contrast to the classical sonata-Allegro norm—where introductions demand attention, establish the key, and present thematic material—the slow introduction of HII functions more like a dramatic symphonic poem. The first searching Adagio melody symbolises primordial chaos, the second in G minor presents the idealised hero, and the third in G major marks the sudden appearance of Harold, restoring order from b.38 onwards. The first two Adagio melodies build towards this third iteration, introduced after a short re-exposition. Berlioz describes this “recur[ring]” “motto (the viola’s first theme)”, or “Harold theme”, as one that “superimpose[s]” and “contrast[s]” with “the other orchestral voices […] in character and tempo without interrupting their development”, as though it exists apart from the symphony (Berlioz 2002, p. 216). Although Berlioz composed it quickly, he later “revis[ed]” it thoroughly and emphasised its “complex harmonic organization”.

The formal structure—two contrasting melodies plus an overriding third—fulfils the illusion of a viola concerto while representing Harold as a Byronic figure who merges several historical and literary rebels. The Romantic “outsider” thus exists both within and outside the formal order of the piece.

The solo viola first presents this G major “Harold theme” accompanied by harp, blending the concerto tradition with balladic lyricism. Berlioz’s stage directions intensify this effect: “The harp must be placed close to the solo-viola”, and “[t]he player must stand in the fore-ground, near to the public and isolated from the orchestra” (Berlioz 1900, p. 151). This staging enacts Harold’s emotional and narrative isolation, iconic to a remote mountainous setting.

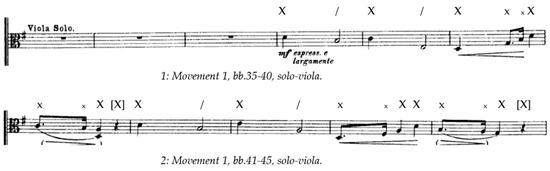

Musically, the harp strums ascending G minor and G major arpeggios in bb.36–37, dissipating the initial ombra (shadowy) atmosphere. It fades in pizzicato (plucked), leading to the solo viola’s entrance in b.38, in moderately loud dynamics, or mezzo forte (mf), indexically suggestive of tentative confidence (see Figure 5 and Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Movement 1, bb.35–40, harp, solo viola.

Figure 6.

Movement 1, bb.41–45, harp, solo viola.

The lack of harmonic support from the rest of the orchestra emphasises this isolation, positioning the viola as an external, distant observer rather than a participant. This orchestral distancing is a metaphor for Harold’s detached perspective as a wanderer.

Beyond harmonic support, the harp becomes a symbol of externalised inner beauty and poetic inspiration. In the Romantic view, the lyre provides supernatural insight (Abrams 1953, p. 51). In the Prologue “To Ianthe”, Byron’s speaker implores the addressee, Ianthe, to “[a]ttract thy fairy fingers near the lyre” and perform “the most my memory may desire” (CHP, I, “To Ianthe”, 5, ll. 42, 44). This resonates with Harold’s farewell, where “[h]e seiz’d his harp” “with untaught melody” to sing “his last ‘Good night’” (CHP, I, 13), his only attributable song (Beatty 2019, p. 270). The “Harold theme” does not fully integrate with the other melodies; it floats above the Allegro fleeting joy, like a melancholy shadow hovering over the brighter 6|8 sections from b.94b, anticipated in the preceding 3|4 Adagio (Berlioz 1900, p. 168). The tension echoes the Byronic hero’s grief and detachment amid pleasure and community.

5.2. Farewell to Convention and Iconicity of Rhythm and Form

Berlioz departs from both mediaeval and classical conventions. Byron’s balladic lyricism in CHP often juxtaposes beauty with violence and captivity. For example, Ianthe, the subject of idealised praise, is also metaphorically likened to a “matchless lily” in a conqueror’s “wreath” (CHP, I, “To Ianthe”, 4, l. 36), a metaphor that resonates with the viol root of the viola.

This ambivalence reappears in the Albanian folksong “Tambourgi”, a drummer’s ballad “half sang, half scream’d” (CHP, II, 72), where a maiden is asked to sing with “her many-ton’d lyre” of “the fall of her sire” (CHP, II, 72, “Tambourgi”, 7). The four-line stanzas, in iambic pentameter with hypercatalexis (an extra unstressed syllable), like “To Ianthe”, and the ABAB rhyme echo Byron’s flexible form.

Similar effects appear in Harold’s youthful songs of idle melancholy (CHP, III, 3), later replaced by the claim that “my heart and harp have lost a string” (CHP, III, 4). This turn toward exile for “[f]orgetfulness” evokes a poetic mode where song becomes an attempt, though unsuccessful, to

- […] wean me from the weary dream

- Of selfish grief or gladness.

(CHP, III, 4)

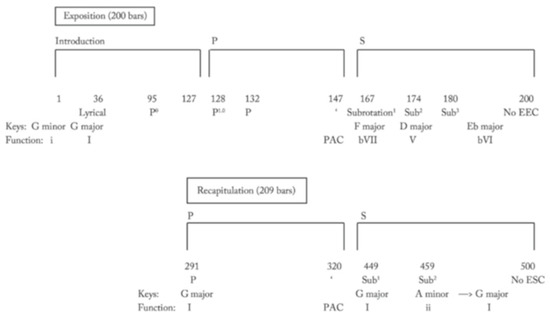

The third Adagio, “Harold theme” (see Figure 7; see Appendix B), furthermore, iconically reflects the peculiar metrical structure of Byron’s verse and mentions a lyre.

Figure 7.

The “Harold theme” with poetic stress in note-value analogy (my markings).

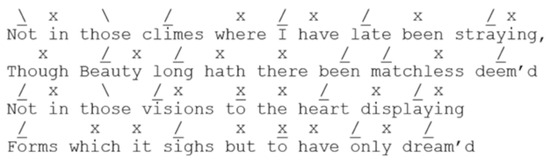

Its rhythm mostly links with Harold’s farewell. Its two phrases of eleven notes (bb.38–41 and 42–45) mirror the eleven-syllable lines in “To Ianthe” (ll. 1 and 2; see Figure 8; see Appendix B) and “Tambourgi”:

Figure 8.

Scansion of CHP, “To Ianthe”, 1, ll. 1–4.

Berlioz may not have consciously mapped French syllabic prosody onto Byron’s English accentual metre, including the occasional line-ending ellipsis. When voice-leading and passing notes are differentiated, with three sizes of unstressed syllable (x), in the scansion, the melody reveals a striking iconicity:

The excess, like the additional syllables in the verse, is reflected in the note-value to poetic stress analogy. It is also paralleled in number and beat in the first Adagio. The iambic feet off-balance the strongest first beat until the longer second note in 3|4. In reduced prosodic terms:X/ X/ XxxX xxX[x]X/ X/ xxXX xxX[x].(see Figure 7)

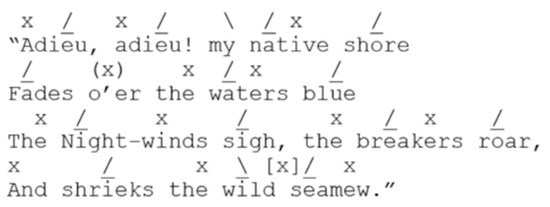

The rhythm approximates the scansion of the first two lines of Harold’s farewell ballad (CHP, I, 13, “‘Adieu’”; see Figure 9; see Appendix B).x/x//x/x/[X]x/x//x/x/[X].

Figure 9.

Scansion of CHP, “Adieu”, 1, ll. 1–4.

The eleven-note phrases also allude to Byron’s Beppo and DJ, written in ottava rima, where lines frequently alternate between ten and eleven syllables.

Through such melodic-poetic resonances, Berlioz’s music evokes thematic opposites: war and love, grief and joy, and song and silence. In the preface, Byron explicitly links Harold’s farewell to Sir Walter Scott’s historical ballad “Lord Maxwell’s Goodnight” (“Preface [to Cantos I-II]”, CHP, p. 4). Maxwell, fleeing accusations of murder and treason, utters:

Harold’s “Adieu” adapts this farewell into alternating iambic tetrameter and trimeter lines of eight and six syllables, respectively. Musical notations in Scott’s Minstrelsy, inserted between pp. 140–1, suggest flexible rhythms and accents, reinforcing the balladic influence.2 Other sources include J. Leyden’s romantic ballad “Scottish Music: An Ode”, addressing “Ianthe”, and “Introduction to the Tale of Tamlane: On the Fairies of Popular Superstition” (Scott 1861, pp. 249–53, 254–350), which further connect Byron’s poetry to folk and supernatural traditions, echoing in motifs like Peri fairies, to which Ianthe is compared (CHP, “To Ianthe”, 3, l. 19). Berlioz’s “Harold theme”, therefore, serves as an iconic reference to these balladic and historical sources via Byron’s revision.Adieu, madame, my mother dearBut and my sister three!(Scott 1861, p. 141, ll. 1–2).

5.3. Thematic Flux and Historical Allusions

Beyond rhythmic parallels, the harmonic progression of the “Harold theme” enacts transgression and reform. It alternates between classical symmetry and Romantic Sturm und Drang, reflecting the political tensions in CHP and Scott’s Rob Roy, about the social reformer Robert Roy McGregor. The latter text stages a “dialectic synthesis” of heroism and disillusionment, which “might bring about historical progress” (Burwick 1994, p. 93), akin to the Jacobite aspirations in 1715 for the restoration of the Stuart monarchy.

On the other hand, Berlioz’s tritone in b.56 (E-flat and A) invokes demonic associations similar to the second Adagio (b.19). This tonal instability, similar to Harold’s character, signals ideological struggle, a transition from idealist to sceptic. The final section (from b.81) reframes or reinterprets earlier material: the E-flat major chord becomes the flattened submediant to G major, rather than the submediant of G minor, hence a symbolic inversion of values. The “Harold theme” thus represents ideological flux, thesis and antithesis.

G.K. Chesterton remarks that Byron’s pessimism in content is often contradicted by the buoyancy of his metre: “all the time that Byron’s language is of horror and emptiness, his metre is a bounding pas de quatre”, rendering Byron an “unconscious optimist” (Chesterton [1902] 1970, pp. 484–5). Berlioz reflects this paradox through the bipartite “Harold theme” that moves from lyricism to irony, from pastoral calm to martial disruption, musically enacting the Faustian journey from idealism to disillusionment and Romantic irony. The theme, moving from a slow resonant part to a tense dotted rhythm, iconically displays a phonemic parallel to “To Ianthe” in CHP: the liquids, nasals, and diphthongs of the first line evoke open landscapes, while the fricatives and short vowels of the third line suggest inner conflict.

5.4. Faustian-Byronic Structural and Narrative Compression

Berlioz’s HII participates in a tradition of Faustian works, with four movements loosely corresponding to nature, prayer, serenade, and cynicism. Berlioz would later develop this trajectory further in The Damnation of Faust (1844), in which Euphorion—based on Byron—from Goethe’s Faust, Part Two (1832), attempts transcendence and falls tragically. Similarly, Berlioz’s Harold mixes tragedy, humour, and satire. Each movement of HII reinterprets CHP through a different lens: psychology, faith, love, and politics. Despite differing bar counts, all four movements recapitulate the poetic journey from distinct angles. The “Harold theme” becomes a microcosm of both the first movement and the work as a whole.

Berlioz’s innovation challenges both musical and critical conventions (Berlioz 1972–1975, 2, p. 188),3 just as Byron reworks poetic content and form. The composer’s stance aligns with Mellor’s reading of Byron’s “process of becoming” as an “open-ended, self-expanding awareness” that resists “reintegration” or closure (Mellor 1980, pp. 31–32). Similar to CHP and DJ, HII embraces multiplicity and ambiguity. Its structure, theme, and staging reflect the Byronic hero’s refusal to resolve his antitheses, mirroring a Romantic psyche fundamentally in conflict with itself.

6. Mourning, Revelling, Then Revolting

6.1. Cycles and Constructivism

A cycle of mourning, revelling, and revolt throughout HII, articulated in the succession of melodic fragments and transformations. Berlioz’s calculated spontaneity in the deployment of the fragments juxtaposes compositional constructivism with the semblance of inspirational inspiration. In bb.126–131, the solo viola reiterates and reconstructs the first Allegro melody in fragments, progressively accumulating its note sequence. This act, iconically reminiscent of a learning process, conveys staged happiness—an impromptu, yet deliberately constructed, moment of joyful discovery (see Figure 10). Girard describes this passage as the solo viola’s naïve discovery, alluding to Beethoven’s First Symphony (Girard 2012, pp. 29–30). Figure 10, bb.126–130, shows how the melody is broken into isolated pitches and small motifs, separated by rests. This fragmentation simulates a process of memory or recollection, consistent with the wanderer’s role in the narrative.

Figure 10.

Movement 1, bb.126–132, solo viola, violins I, with poetic beats (my markings).

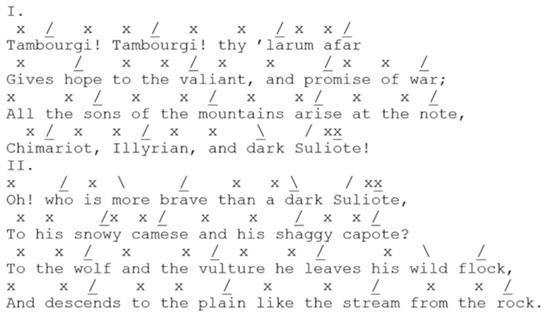

The scansion of the “Tambourgi” song (CHP, 72, “Tambourgi”, I, line 1; see Appendix B) most closely maps onto the first Allegro melody (see Figure 10 and Figure 11), bb.130b–131:

Figure 11.

Scansion of “Tambourgi”, stanzas I and II.

The scansion aligns with the music in an analogy between the four beats of a line (e.g., /) and the first beats in the musical bar of the first Allegro, with the feel of triplets.

Berlioz’s reception in France adds a bitter historical resonance to these passages. A notorious commentary in a Parisian magazine mocked the symphony with the chant: “Ha! ha! ha!—haro! haro! Harold!”; Berlioz interpreted this as a public denunciation and a personal attack, associating it with the mediaeval judicial ritual of the “Clameur de haro” [haro clamour], a cry used to accuse criminals in public and shame them into exile or worse (Berlioz 2002, p. 218; Toureille 2003, pp. 177–8). In this context, the journalist’s mockery frames Berlioz as a musical transgressor—a brigand violating artistic norms—using the very icon of the fragmented musical phrasing. The “Haro” thus symbolises ostracism, the opposite of suffrage or public endorsement, which Berlioz sought but rarely received in France (Berlioz 1972–1975, 1, p. 229).4 This mirrors Byron’s own experience of alienation and his reference to sea “pirates” (CHP, II, 72, “Tambourgi”, V).

Nevertheless, the fragmented pronouncement of the first Allegro (see Figure 12), a retelling of the “Harold theme”, by the solo viola, stages self-reflexive reclamation of the theme in a new rhythmic and rhetorical context.

Figure 12.

Movement 1, bb.93–101, solo viola, violins I.

After the “haro” protest obstruction of the sprightly Allegro, the solo viola adopts the theme from b.132 with subtle alterations in rhythm, tone, and articulation, meandering over light accompaniment. The tune is simplified into quavers and a few crotchets, suggesting an index of more lyrical, sauntering character. Ralph Bathurst notes that the viola either plays a solo melody or a “melody [that] is broken up” (Bathurst 2016, p. 29). This reflects the flexible leadership of the solo viola: it conducts and corrects the orchestra while sharing its role, completing and mirroring the orchestra’s phrases. Together, the musical and poetic narratives symbolise Harold’s shifting mindscape—a sequence of emotional states and reflections indexed by melodic transformation.

In the Allegro, speed alone does not signify a positive attitude; rather, it combines with harmonic and melodic gestures that evoke spiritual elevation. In bb.166–188, the second Allegro melody begins in F major—symbolically lowering the tonal centre from the G major to the third Adagio (see Figure 13).

Figure 13.

Movement 1, bb.162–170, trombones.

Since the F major key (one flat) is not closely related to G major (one sharp), the modulation is unexpected, even refreshing. According to sharp-flat symbolism, movement downward on the circle of fifths represents a shift towards melancholy or introspection, a spiritual darkness, while upward motion signifies “bright[ness]” and spiritual “elevat[ion]” to a “heavenly” realm; shifting to the submediant or flattened submediant, particularly, has been linked to a most sacred elevation or sublimation (McKee 2007, pp. 38–40, 49). The second phrase of the second Allegro, in bb.170–183, modulates in a sequence imitation (subrotation) to B-flat major (two flats), while the solo viola responds in D major (two sharps; four up the circle) from b.173, indexically reclaiming dominance over the G major tonal field. Alongside the modulated imitations, a syncopated canon and semitonal oscillations in the violins I, introduce tension, preventing a straightforward return to G major (D minor, G minor, and E-flat) and resulting in an anticlimactic resolution with sudden dynamic shifts (f-mf-pp) and pizzicato articulation.

The various iterations of the “Harold theme” and its motifs depict a landscape that veers toward a happier disposition, but not without irony or distortion. Byron’s ambivalent attitude towards transcendence in nature is thus musically rendered. The modulations mirror a descent down the circle of fifths: from G major, icon of the ground (French le sol as a G-note in solmisation), to F major from b.166, then briefly ascending to D major before descending to E-flat major. The latter, being the flattened submediant to G major, evokes the “Eroica” heroism while simultaneously subverting it into a Byronic anti-heroism that exists on the threshold between idealism and rebellion, as well as seeking unconventional ways to experience self-sublimation (McKee 2007, p. 32). The opening G minor of the first Adagio, associated with the ombra style, reappears as the mediant (iii) of E-flat major, suggesting that the piece begins not in a state of simplicity but in an elevated, sublime mode for which the protagonist is not yet prepared.

The second Allegro melody further distorts the jolly tune with syncopated tritones in the clarinets in bb.189–190 (see Figure 14).

Figure 14.

Movement 1, bb.183–190, clarinets, horns, bassoons.

Evolving from syncopated trochee-like notes in the bassoons and solo viola, triplet divisions in diminished seventh oscillations in bb.184–191 accentuate the syncopation in the woodwind and then strings, and they evoke pangs of fear, regret, or anxiety, emotional markers of the Byronic hero’s confrontation with human frailty.

The Allegro contrasts eudaimonic happiness, rooted in virtue and meaning, and hedonistic indulgence, a dichotomy further explored in the fourth movement. It parallels Harold’s multilayered quest. On his second journey, in Canto III, as opposed to escaping community, Byron’s Harold forfeits all pursuits of virtue or meaning for an “[e]xistence by enjoyment” (CHP, III, 34). Before the development, the reprise of the two Allegro melodies proper in bb.131–191, initiated by the solo viola, symbolically portrays prolonged happiness that ultimately collapses, echoing the cycles of idealism, corruption, and disillusionment. The alignment of soul and body (virtue and pleasure) required for self-actualisation proves fleeting; the Byronic cynicism expressed in the theme distortions tolerates but ultimately refutes the notion of perfect harmony.

These melodies represent varied approaches to joy, through nature, culture, or rebellion, each reflected in their chordal inversions and phrasal contours. While the third Adagio begins with a root-position G major (minus the tonic), the first Allegro with a second inversion, and the second Allegro with the first inversion, implying a sequence from melancholy to happiness to joy. Phrasal motion similarly alternates: the first Adagio, first Allegro, and second Allegro open with ascents followed by descents, while the second and third Adagio reverse this pattern. These structural differences symbolise shifting perspectives, from the mountain summit to the introspective valley, and the self-critical hindrances that accompany creativity and growth.

6.2. Recurrence and the Miniature

The Allegro phrases indexically mirror and develop the Adagio material. The second Allegro expands on the second part of the third Adagio. In this way, the first two Adagio melodies serve as foreshadowing fragments—building blocks not only for the third Adagio but also for the Allegro sections that follow. Jeffrey Langford identifies the third Adagio as the “cyclically” unifying element of the piece (Langford 1997, p. 204), revealing that Harold’s character and the form of the work are intertwined. The melodies, such as Byron’s poem and protagonist, are bipartite: a sentimental, lyrical phase subsiding to agitation and violence. The third Adagio, previously rejected, becomes the generative core of the piece, symbolising Romantic wistfulness and reflection.

The “Harold theme” functions as the mountainous source from which the rest of the music flows, echoing CHP, where Byron links a Spanish river to a Portuguese mountain (CHP, I, 14). The basic chordal sequence recurs in disguised forms throughout the work, in different tempi, rhythms, and topics. This approach parallels Beethoven’s use of repeated underlying progressions in piano concerti (McKee 2007, p. 38). The Romantic miniature aesthetic—“short, symmetrical harmonic sequences […] rescued by highly original figuration” (Winter 2001)—underscores these motivic transformations. Byron’s poetry serves as the seed for the cyclical and fragmentary growth of the music.

Despite contrasting characters and tempi, all melodies derive from the fundamental harmonic progression of the “Harold theme” (I-IV-I-V and II-V), revealing different guises of internal ambivalence. Each section subtly alters this pattern, creating a sub-narrative of variation and self-examination. The third Adagio consolidates these variants into a foundational structure, while the Allegro sections develop, embellish, and disrupt the progression through chromaticism, diminished chords, and cadential oscillations.

For example, the first Adagio, bb.1–9a, intensifies the sense of unresolved tension in the secondary dominant by substituting a minor dominant for the tonic; the second Adagio, bb.14–29, replaces the tonic with the submediant and introduces the flattened supertonic. The first segment of the third Adagio (bb.38–45) establishes the “ideal” version and harmonic format (I-IV-I-V; I-ii7-V-I); the second (bb.54–58) leaps to the secondary and then tertiary dominants, causing an oscillation (V-I); and the third (bb.81–89a) refurbishes the second Adagio.

The first Allegro forgoes the submediant in the pre-melody (bb.94b–109a) and the first part (bb.130b–138b). It recovers the submediant in the second part (bb.138c–146a) but inserts intruding diminished chords within the descending chromatics that symbolise emotional instability and creative striving. The second Allegro, bb.166–196′, traverses a similar path; it oscillates on the perfect cadence, visits the secondary dominant, and returns without resolving the tension. After the reprise, the fragmentary interaction of the Allegro melodies continues until b.322. The movement closes with the merger or alternation of elements from the third Adagio and both Allegro melodies.

The development section, bb.192–290, fragments the melodies further, symbolising individualism and rotating power structures, both musical and political. Instrumental turns mirror a meritocratic ideal, though their chaotic interplay reflects the divided self of Byron’s Harold—an internal struggle between unity and dissolution. As the “Harold theme” recedes, its significance amplifies, foreshadowing triumph through defiance, as in Byron’s Prometheus: “[t]riumphant where it dares defy” (Byron 1981–1993b, p. 33, l. 58). This theme becomes not merely a personal lament but an anthem of chaotic resistance.

6.3. Byronic Critique of Political and Religious Governance

In the fourth movement, Berlioz amplifies these ideas with religious and political allusions analogously to Byron’s poem. The first “brigand” Allegro melody introduces militaristic rhythms in a fragmented form (see Figure 15).

Figure 15.

HII, Movement 4, bb.1–6, violins I.

The strings play in bb.8–10 accentuated octave movements iconic of using unsheathed “sabres” and pillaging (CHP, II, 72, “Tambourgi”, 4, 6) (or drink-induced hiccups). Meanwhile, the fanfare and strings alternate with descending diminished arpeggios that index doom and death.

Interrupting the development of this melody, the orchestra recalls a series of previous melodies: (1) “A reminiscence of the introduction”, identified as the first Adagio, from b.12; (2) “A reminiscence of the pilgrim’s procession” from b.34 by the solo viola; (3) “A reminiscence of the mountaineer’s Serenade” from b.45b; (4) “A reminiscence of the first Allegro” from b.60; and (5) “A reminiscence of the Adagio”, identified as the “Harold theme”, from b.80, distributed among the orchestra. The sequence of nature, prayer, serenade, and cynicism, thus, reappears. The solo viola plays the latter in a distorted manner, without resolution; it betrays idealistic pursuits and embraces alienation.

The solo viola notably supplants another soloist, the cor anglais, or English horn, from the third movement, adopting the mountaineer’s serenade to his beloved from b.45b (see Figure 16).

Figure 16.

Movement 4, bb.46–54, solo viola.

The rhythmic incongruence between the 3|2 solo and 2|2 orchestra, although they are of “the same time-value” (Berlioz 1900, p. 261), symbolises courtship versus social order. The melody is deprived of the peasant celebration that engulfs it in the third movement with a very fast tempo, fast-paced 6|8 rhythm, and cheerful mood (Allegro assai) in the earthly C major key, as well as pifferari drones and pastoral folk song markers (see Figure 17).

Figure 17.

Movement 3, bb.8–15, piccolos, oboes I-II.

This absence echoes Byron’s mixed attitude towards dance, love, and cultural rituals. Whether for its indexical representation of antitheses, however, the serenade melody is not rejected with repeated notes. The folkloric rhythmic tune harmonically derives from the third Adagio with extra cadential oscillations: I-V7-(x7)-IV-I7-(x2)-IV-V; I-V7-(x5)-IV-I-V-I, which reinforces Harold’s omnipresence. When the first “brigand” Allegro melody, restarts in a chord blast (fortissimo) on E minor (the relative minor of G major), it paradoxically expresses joy through rebellion, blending martial and pastoral elements.

The contrasting second “brigand” melody, or the continuation of the first, introduced at b.140, is indexically more sentimental (see Figure 18).

Figure 18.

Movement 4, bb.142–148, violins I.

Reiterated in modulated imitation, the second “brigand” melody consists of a rising sequence of an arpeggio followed with a chromatic descending run, which exudes lament and alarm. It is described as “a sentimental rollocking burlesque, worthy of a light operetta, containing erotic and drunken imagery” and deemed of “autobiographical” and “artistic importance” (Thomson 2016, p. 46).5 The revelry elevation from b.149 is short-lived and resembles wailing tremolos, and a crash ensues from b.157.

The pattern of hedonistic merriment followed by a flurry of notes calling to battle is repeated across CHP, in the Ottoman (CHP, II, 72, “Tambourgi”, 1) and Waterloo contexts. The soldiers in “revelry” were ordered to “hush! hark! [since] a deep sound strikes like a rising knell!” and called to “Arm! arm! and out—it is—the cannon’s opening roar!” (CHP, III, 21, 22). The revellers’ “lusty life” is interrupted with a “midnight” call to battle in the “morn” (CHP, III, 28). Similarly, with “mountain-pipes”, the Scottish mountaineers show their “fierce native daring” in the Napoleonic Wars, as in the past Jacobite uprising (CHP, III, 26). Berlioz, therefore, layers wars iconically as “one burial blent” (CHP, III, 28).

6.4. Conflict, Disillusionment, and the Afterlife of Ideals

Berlioz adds another layer of political symbolism by introducing the “Napoleon” melody that takes prominence over the “brigand” melodies from b.177 (see Figure 19 and Figure 20).

Figure 19.

Movement 4, bb.169–175, violins I.

Figure 20.

Movement 4, bb.176–182, flutes.

Its harmonic progression is I-V-I-V-II and V-I-IV-I-V, where the perfect cadence of the second phrase replaces the interrupted cadence of the first. The B-flat major of the “Napoleon” melody functions, at first glance, as the major relative of the G minor key, the change indexically connoting hope and aspiration. Nonetheless, the initial key of HII that connotes the ground, G major, modulates down three circles of fifths (G-C-F-B-flat), which symbolises a dark, hellish existence.

The “Napoleon” melody is composed in the Turkish style (Locke, Ralph P. 2009, in Mayes 2014, pp. 214–15). Based on the military Janissary bands and the alla turca, the Turkish topic does not allude to the Ottoman Empire directly but to European perceptions of exoticism and barbarity (Mayes 2014, pp. 216–18, 223, passim). Byron held the belief that any figure, “[a] thousand images of one”, whose “heart […] which not forsakes” its reformative vision, keeps the ideal alive “in shattered guise” (CHP, III, 33). For Berlioz, emperors were often “glorified brigands”, and Berlioz equally cultivated a fascination towards Napoleon despite political and personal shortcomings (Berlioz 2002, p. 611). The Turkish topic embodies both attraction and repulsion, a symbol of imperial rise and fall.

As the “Napoleon” melody battles the brigand melody, the music stages a sonic war. Bass drones, tremolos, and triplet rhythms in the strings represent cannon fire and marching soldiers (see Figure 21 and Figure 22).

Figure 21.

Movement 4, bb.207–213, violins I-II.

Figure 22.

Movement 4, bb.214–219, clarinets, horns I-II.

With stomping staccato crotchet triplets “ponderously” from b.215 (Berlioz 1900, p. 280), iconic of trampling foot soldiers, woodwind and brass indexically counter the tremolo semiquavers in the strings, while the interspersed muffled timpani notes are iconically catapulted as cannonballs (see Figure 22). The ensemble arrives at a B-flat diminished seventh chord in b.231, symbolising instability and ceasefire.

A very soft, expressive violin melody (espressivo, pp) in B-flat minor follows (b.232), with descending semitones, marking disillusionment after conflict (see Figure 23).

Figure 23.

Movement 4, bb.232–240, violins II, violas.

This musical sigh, adopted by the rest of the orchestra, parallels Byron’s reflections on Napoleon, whom he compared to Prometheus, and links to the viola’s role as the violet—a symbol of remembrance and defiance. Through this chaotic yet cyclical structure, Berlioz composes an anthem of Haroldian rebellion, maintaining the Romantic ideal of defying mechanistic systems while accepting the inevitability of historical repetition.

In a later recalled melody, not labelled a reminiscence, a solo trio of violins and cello play the Pilgrims’ March from b.473 (see Figure 24 and Figure 25).

Figure 24.

Movement 4 bb.463–476, solo-violin I, solo-violin II, solo-cello.

Figure 25.

Movement 4 bb.477–490, solo-violins I-II, solo-cello, solo viola.

The trio plays the fourth Canto from the Pilgrims’ March (of the second movement) from bb.473 (see Figure 24) and, following distortions by the soloists themselves, the tenth Canto from b.483 (see Figure 25). It represents the procession marching away as another farewell. With the solo viola observing, this echoes Byron’s critique of religious institutions, where monastic life entails “making earth a Hell” (CHP, I, 20) and where faith and hope are fragile turn-taking constructs “built on reeds” (CHP, II, 3).

The soloists, in a chamber music format, resound “From the wings” of the theatre (Berlioz 1900, p. 310), or offstage. Politically, their election symbolises elite privilege and collaborative governance. It alludes to inequitable and unquestioned power structures. Their own alternating distortions, of four quavers and triplet quavers, in bb.480–482, indexically gesture towards political accusation and religious scepticism, suggesting the equivocation and fragility of a Lockean limited government.

The solo viola joins in minimally on its uppermost range using the treble clef with its own improvisatory statement. This includes a drone, a scale, and syncopated tritone slurs from b.493 (see Figure 25), defiance set in increasing dynamics. Its final statement in more intense dynamics and syncopated octaves in bb.501–505 reaches a perfect cadence in fortissimo (ff), accompanied with the orchestral strings in triplets and tremolos (see Figure 26).

Figure 26.

Movement 4, bb.501–506, solo -viola, violins I–II, violas.

During the battles, the solo viola, silenced from b.110, supposedly leads the viola section as outliers in a hands-on approach, akin to Napoleon’s, and then recedes, disgusted by the atrocities, thereby foregrounding the orchestral “brigand” music, which Bathurst calls “the leadership of everyone” (Bathurst 2016, p. 32). The solo viola, the idealised form of Napoleon, returns briefly since “quiet to quick bosoms is a hell”, rising again with an analogously short Hundred Days campaign of “high adventure” (CHP, III, 42). The fourth movement, accordingly, ends after one hundred bars, at b.583.

The last tremolo shift into a continual plagal “amen” cadence (I-IV-I) from b.577 (see Figure 27) iconically signifies the flux of the ocean waves beneath Harold (CHP, III, 2).

Figure 27.

Movement 4, bb.570–583, violins I–II.

This cadence symbolises how Harold is in “battle with the ocean” (CHP, IV, 105), experiencing a “pleasing fear” (CHP, IV, 184) as part of a mental journey. The cross-rhythmic majority rule becomes an icon of chaotic order in a political reading of the ocean image. The apostrophe to the ocean conjoins a religio-political reconciliation where “waters washed […] many a tyrant” (CHP, IV, 182), as well as a psychological one, where the “child” metaphorically reunites with its mother (CHP, IV, 184). The alternating chords serve as indexes of Harold’s oscillating faith and reason, ideal and real, condemnation and approval, all working together towards universal truths.

An isotopic reading of HII reveals layers of meaning that connect Berlioz’s music to Byron’s CHP while also reflecting Berlioz’s engagement with Beethoven and his broader historical context. Isotopies identified in HII include: (1) alienation and melancholy; (2) nature and sublimity; (3) religious reflection; (4) folk culture and love; (5) irony and heroic fragmentation; (6) political and historical resonance. These isotopies map not only the narrative dimensions of the music but also its intermedial dialogue with literary and historical contexts. Berlioz’s HII becomes a complex site where affective states, personal experience, and cultural critique converge.

7. Conclusions: Reflection, Reform, and Resonance

Since Byron’s poems were well received among nineteenth-century European composers, this essay has explored the degree to which they fuelled the production of their new musical works. In the case study, applying melopoetics and musical semiotics, it is deduced that several aspects of Byron’s narrative poem Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage are represented in Berlioz’s Harold in Italy. The thematic, structural, and gestural signs in the music can be compared to analogous devices on iconic, indexical, and symbolic levels. Berlioz’s choices of form, orchestration, melody, harmony, rhythm, and allusion function as musical analogues of Byronic devices, most notably in relation to the protagonist figure, whose pilgrimage is multilayered and symbolic.

More specifically, it is observed that the main theme is a structural and harmonic miniature of the whole composition. This “Harold theme” informs the overall structure and mood of the music, generating further melodic material and articulating its central ideas in various guises. The small-scale “Harold theme” is mirrored in the general structural progression, from classical and idealistic to more Romantic and revolutionary. Sonata form is suspended early in the first movement, where Berlioz introduces an obsessively repeated note—an interruption that marks a shift in aesthetic language. The rhythmic sequence of the “Harold theme” itself proceeds from longer to shorter and bouncier notes, indexically signifying a shift from relaxation to more heightened emotional agitation. This progression reflects the emotional sequence of the first movement, as the heading suggests, from melancholy to happiness and joy. Similarly, the first movement progresses from a slow Adagio to a fast Allegro, and the four movements as a whole progress from the ideals of nature and prayer to love serenade and finally to cynical breach.

Berlioz’s Harold, as a palimpsest manifestation of contrasting emotions, natural imagery, and historical events, mirrors Byron’s Harold most poignantly within the Romantic ideology of self-reflection and transformation. Harold is not merely an individual character but an idea—an embodiment of Romantic epistemology and a Faustian-Byronic spirit of reform, the resonance of which extends beyond its historical moment. Both the Faustian and the Byronic narratives follow parallel sequences of reflection and revolution, resulting in a structural overlap in Berlioz’s HII. Berlioz’s shifting use of musical topics further reinforces this reformative impulse. The musical hero’s quest is, therefore, religious and political as much as personal and relational. With its imitation of the germ of Byronic revolution, a reiteration of revelry and reform, Berlioz’s HII signifies the gradual farewell to conventional forms in the art of composition, analogous to those of Byron’s poetic innovations.