Abstract

This paper is an exploration of play in tourism. It is situated in an approach to play and toys informed by phenomenological perspectives and theoretical insights drawn from existential anthropology. It argues that tourism and play are intimately linked and outlines the ways in which connections between the two have been made. This paper focuses on a particular practice of play in travel—one that involves the use of a toy. Using the notion of ‘toy tourism’, I examine the ways in which touristic practices associated with play are brought into being in the moment of doing. The research is located in the resorts of Palmanova and Magaluf on the Mediterranean island of Mallorca. I conducted the research using a doll from the Barbie Fashionista range, who I named Mordaith. I outline how and why Mordaith became my travel companion and the experience and events associated with my time with her in the resorts. This paper recounts the story of what happened when I brought about the play of toy tourism in Mallorca. It is an experimental approach that unfolds in the writing as much as in the gathering of information during fieldwork. I argue that what play is, and what a toy is, are neither fixed nor graspable objectivities. Rather, both toy and play, and, thus, toy tourism, emerge in my embodied imaginative understanding of what touristic and toy tourism practices are, as well as the actual embodied and emotional movements of employing a toy in practice.

1. Introduction

- From time to time we take our pen in hand

- And scribble symbols on a blank white sheet,

- Their meaning is at everyone’s command;

- It is a game whose rules are nice and neat.

Josef Knecht1

In a land not so far away lives a doll called Mordaith. This is a story about Mordaith’s visit with me to a land of faraway—the Mediterranean island of Mallorca—and particularly our time in the tourist resorts of Palmanova and Magaluf. It tells the tale of how we came to venture to Mallorca and reflects on my experiences of travelling with a toy. Before I recount more of the story, I wish to provide some theoretical and methodological background.

My approach has an underpinning drawn from phenomenology, which places an emphasis on the Heideggerian concept of ‘being-in-the-world’ (Heidegger 1978; Jackson 1996; Palmer 2018). It is about experience as it is lived. From this perspective and in the context of a phenomenological approach to tourism and travel, neither is a given. They are brought into being as they are practiced. The same can be said for other key elements in this paper: play, toy, and toy tourism. As I shall set out in the proceeding discussion, a phenomenological approach does not see these things as outside of human life waiting to be encountered. Rather, play, toy, toy tourism, and tourism and travel are part of the living—the ‘active relationship’ (Jackson 1996, p. 11)—of being alive. This being alive is not fixed but ever malleable; it is made real as we go along, and in this going along, we are ever open to possibilities of ways of doing.

Bringing together phenomenological approaches to what is play, what is a toy, and what is tourism, this paper is about the experience of attempting to practice what has been termed Toy Tourism or Toyrism (e.g., Heljakka and Räikkönen 2021a). I became interested in the idea of toy tourism after listening to a conference presentation about research in this area by Katriina Heljakka and her work with Juulia Räikkönen (Heljakka and Räikkönen 2021b) about adult toy play during the COVID-19 pandemic.

As Heljakka and Räikkönen (2021a) note, an important element of the toy tourism practice is photoplay, which in turn is linked to social media. Photoplay is described by Heljakka ‘as one form of doll play’ (Heljakka 2018, p. 475); the act of photographing the dolls and sharing on social media extends the play and means that the toys being photographed become part of ‘an ecology of play formed by the player, the toy(s) and the play environment’ (ibid., p. 477). In the example of toyrism, the visual culture of tourism is manifest in the photoplay and sharing of images on social media, but this requires the presence of material culture, in this case a doll or teddy, for it to be operationalized. My interest in toy tourism developed into wanting to try it myself. The opportunity arose when I returned to the sites of my ethnographic research about British package-holidaymakers.

Set in the resorts of Palmanova and Magaluf on the Mediterranean island of Mallorca, the main focus of my research since the late 1990s (with visits first in 1997, followed in 1998, 1999, 2009, 2015, and 2018) has been the ways in which the touristic experience gives insight into the relationship between ideas of the self and other, primarily in relation to understandings of national identity (see Andrews 2011 for a full account). In 2023, accompanied by my husband2, I was able to visit Mallorca again. The primary focus was to see the changes in the resorts, my last visit in 2018 having been relatively brief. The visit in 2023 was also brief—one week—but I decided to use the opportunity to ‘test out’ toyrism as much as I could alongside my other fieldwork goals, having noted that the toy tourism literature does not discuss the phenomenon in party tourism destinations, such as Magaluf.

Like much anthropological fieldwork, I did not embark on the journey with the idea of answering a set number of questions (Okely 1994). Moreover, the analyses of material collected—observations, reflections, experiences—does not end neatly; it is ongoing during fieldwork and continues post fieldwork (ibid.). The ethnographic experience is open to an ongoing negotiation of the field. For me, taking a toy was an experiment. I was literally trying to understand what it was like as an adult to carry such an object on holiday and use it in a holiday setting. I was open to finding my way as I went along. As Ingold notes ‘the perceiver-producer is thus a wayfarer, and the mode of production is itself a trail blazed or a path followed’ (Ingold 2011, p. 12). I wanted to use the experience (necessarily restricted by the parameters in which I needed to work) not only to try to understand what it felt like to have a toy in the field with me but to reflect also on the very notions of what is ‘play’ and what is a ‘toy’. Taking Mordaith with me was also meant to be playful.

The link between ethnographic fieldwork and play was made by anthropologist Malcolm Crick (1985), who, commenting on increasingly reflexive understandings of fieldwork, drew attention to the ludic elements shaping the epistemological foundations of both data collection and output. Further, comparative media scholar T. L. Taylor argues that ethnography and play are closely related, highlighting the ‘embodiment, the affective qualities, and improvisations we so often find in ethnographic work’ (Taylor 2022, p. 36) Taylor draws on the work of anthropologist Clifford Geertz (1973) whose seminal writing on the Balinese cockfight pointed to the value of studying play to give insights into understanding aspects of cultural practice.

Locating the Field

Magaluf and Palmanova are located on the Bay of Palma, southwest of Mallorca’s capital, Palma. The resorts have long been associated with British3 package-holidaymakers, to the extent that they could almost be described as a British enclave. Although located very close together, in terms of atmosphere, they are quite different places. Magaluf has a reputation as a site of hedonistic, carnivalesque behaviour, much of which is aimed at a youth market. By contrast, Palmanova is more family-oriented. Both resorts have the appeal of sun, sea, and sand, and both cater to a British market looking for familiarity in terms of, for example, food and drink, along with the reassurance of widespread spoken English. The tourists derive from all parts of the UK and Northern Ireland and are predominately white, heterosexual, and working class. In recent years, the political economy of the resorts has changed, along with the introduction of measures to curb what has been described locally as ‘tourism of excesses’, with a move to encourage a more diverse range of tourists and particularly those with higher spending power (Andrews 2023). I first went to the resorts in 1997, and the changes to the profile of the tourists since then has been notable. Although the British currently still dominate, the presence of other nationalities from Europe is evident, and the profile of the British tourists represented a bit more of the ethnic and sexual diversity that, now more openly than before, characterises the homeworld. I have written extensively about the British on holiday in my efforts to understand relationships between self and other that are based on a form of effervescent Britishness that has been signalled, embodied, and practiced in the resorts by tourists (Andrews 2011). My visit in April 2023 was the first time that I had taken a toy with me. As the story I shall tell involves a toy, and toys are primarily associated with ideas of play, and because this is a tale that emerges primarily from touristic practice, in the next section I shall outline the relationship between tourism and play and briefly situate this discussion within a broader, more generalised debate about play. This will lead to the suggestion that a helpful lens through which to understand play is through a focus on the experience of playing rather than thinking of play as a category or an object of study.

2. Tourism and Play

There is a long-established link between tourism and play, from building a sandcastle on the beach with a bucket and spade to playing a variety of games. Such games might involve, for example, playing with bats and balls, buckets and spades, kites, and frisbees. Both adults and children play games, sometimes together and sometimes in respective peer groups, among families and friends, with the people they have gone on holiday with, and with others met as part of their vacation. In the context of the organised package tour destination that this research is situated within, game playing is often organised by those who attempt to mediate the tourist experience—package holiday company representatives, hotel entertainers, and bar and nightclub DJs (Andrews 2011, 2023).

In the case of the resorts of Magaluf and Palmanova, audience participation games might take place as part of night-time entertainment in hotels or as part of tour operator–organised bar crawls. The sorts of activities undertaken might include, for example, alcoholic drinking games—the rapid imbibing of three potent cocktails in a row without vomiting—sexual position games in which couples are asked to simulate different acts of copulation (sometimes with the use of a balloon as a prop for sexualised parts of the body), and other kinds of role playing. During the day, there might be organised competitions as part of hotel entertainment, such as table tennis or water volleyball. Further, both Palmanova and Magaluf have facilities dedicated to game playing, with air hockey tables, claw grabber games, whack-a-mole-type games, table football, and pool tables (also found in some bars). Palmanova was also home to two mini-golf courses—Mini Golf Tropico 18 and Golf Fantasia. Similar kinds of games and activities are found in the Katmandu theme park located in Magaluf. Doubtless, there are also things that I have missed. Opportunities to play, in a similar vein to those I have mentioned in relation to Magaluf and Palmanova, can be found in countless tourist destinations. Given this, it is demonstrably the case that tourism and play are intimately linked (Andrews 2011 and field notes Andrews 2023).

In the tourism studies literature, the connection between tourism and play is well-established. For example, Gyimóthy and Mykletun (2004) discuss the adventure tourism of Arctic trekking, arguing that components of its practice are a form of adult play. Kane and Tucker (2004, p. 217) also turn to adventure tourism identifying that tourists ‘play with the reality of their experience’ through the stories they weave around their practice. Writing in 2009, Duncan Light (Light 2009) discusses the idea of embodied play in relation to the performance by tourists of an imagined Transylvania based on the place-myth derived from the Dracula story. These examples acknowledge the role that play can have in tourism activity. In these examples, the play is with ideas of self and identity. The tourists are not playing with material culture, as in the case of toyrism, but rather with their performances that lead into narratives of adventure and related cultural capital. Godbey and Graefe (1991) argue, however, that tourism (and not just particular forms or aspects of it) is a form of play if it is viewed as a process rather than as a one-off activity or series of events. Thus, tourism as a whole is a form of play if it is viewed as marking a break from the serious, quotidian world of work and domesticity.

Writing in 1985, sociologist Erik Cohen used the idea of tourism as play to try to understand the nature of liminality and ritual processes in contemporary Western society. By arguing for an understanding of the role of play in tourism experiences, Cohen was in part providing a counter to MacCannell’s (1973) arguments regarding authenticity; the implication being that some tourists have a ‘playful acceptance of the make-believe presented by the attractions’ (1985, p. 295). Authenticity for this ‘type’4 of tourist is, therefore, a secondary concern. Cohen was endeavouring to explore Victor Turner’s distinction between liminality and liminoid, both of which can be characterised by elements of ludic behaviour. Turner placed liminality in pre-industrial societies in which ‘work and play are hardly distinguishable’ (Turner 1982, p. 34) and the liminoid in modern, industrialised societies in which there is, he attests, a ‘clear division between work and leisure’ (ibid., p. 35, emphasis in original). Such a simple dichotomy between work and leisure has long been the subject of debate—see, for example, Haywood et al. (1990). It is not my intention to revisit these arguments, other than to emphasise that generalisations oversimplify the complexities of social life that exist throughout its practice, whether that is labelled as leisure, work, or even whether it can be categorised as tourism or not. We might equally apply such a complexity of meaning to play.

3. What Is Play?

In his note on play, anthropologist Don Handelman (1974) argued that much attention had been given to play by animals and children, with less attention to the adult world of play. This was, he argued, because adult life was imbued with ideas of seriousness and, yet, ‘uninstitutionalized play among adults is widespread’ (Handelman 1974, p. 66). Drawing on his work among elderly men in a shelter in Jerusalem, Handelman argued that play allowed for expressions of dissatisfaction without threatening the existing social order because play was not treated seriously. For Handelman, the play he witnessed served a serious purpose, and he argued for the value of paying attention to play to illuminate issues of social organization.

While, as we have seen, leisure, work, and tourism do not lend themselves to simple definitions, neither does play. Indeed, anthropologist Brian Sutton-Smith has drawn attention to the ambiguity of play, arguing, ‘we all play occasionally, and we all know what playing feels like’ (Sutton-Smith 1997, p. 1). He goes on to opine that ‘play stands for a category of very diverse happenings’ (ibid., p. 3, emphasis in original). Sutton-Smith then proceeds to identify nine categories of play which exclude ‘informal’ play (ibid., p. 4). He acknowledges that the types of play he lists are not discrete categories and that further diversity occurs in the range of players, play agencies, and scenarios. In attempting to address the ambiguity of play that he identifies, Sutton-Smith argues for a ‘rhetorical solution.’ Highlighting seven types of rhetoric in the theorising of play, themselves not neatly bounded entities (ibid., pp. 7–17), he aims to identify whether the ambiguity of play is a result of the ideological rhetoric underpinning its theorising or whether it is the nature of play that gives rise to such uncertainty about what it is.

Although Sutton-Smith does not make a direct connection between play and Turner’s ideas of liminality, the ambiguity around play that he discusses does suggest elements of the ritual process that Turner (1969) developed. The liminal phase is tinged with uncertainty; it is a time of possibilities. To return to Cohen (1985), he argues that the recreational tourist is playing at reality, imbuing it with an ‘as if’ quality. So, when anthropologist Alma Gottlieb (1982) describes Americans’ vacations and the inversions she argues can occur during this time—being a Queen, King, or peasant for the day—she is arguing for a play at reality, a make-believe. The ‘as if’ attribute gives rise to a realm of possibilities, and it is this potentiality that links to ideas of liminality. As life is lived in flux and the now is always between the past and the future, the constant in-between-ness allows for possibilities of becoming.

As noted above, what play is has been the subject of academic enquiry for decades. Classic texts, including historian Johan Huizinga’s Homo Ludens (Huizinga 2016), first published in the 1930s, and Roger Caillois’s (1961) Man, Play, And Games have steered much of the debate and attempts to understand what play is and its role in the sociocultural world. Caillois argued that there are four types of play: competition (agôn), chance (alea), mimicry (simulation), and vertigo (ilinx). All of these have elements of what he termed ludus or paidia. The latter, he attests, was rulebound, and the former was playful. Like all attempts to classify aspects of the social world or behaviour, the problem here is that people and their various activities do not stay bound by categories. A game with rules might be approached as playful. Being playful may have rules. The examples of play in tourism given in the preceding discussion around adventure tourism and tourism in Transylvania might be described, in Caillois’s terms, as ludic, as they contain elements of competition and are goal-driven. However, there are also elements of creativity and open-endedness that speak to his category of paidia. I suggest that attempts to put parameters on any type of cultural activity in order to objectify and fit a model or schematic is limiting and unhelpful.

My foray into the world of toy tourism is playful, but at the same time it is governed by rules, or rather, proposals (Massie 2018, p. 145). They are proposals because what was guiding me was open to negotiation, primarily with myself but also in relation to other people I encountered during the visit. These proposals were derived from what I had read toy tourism players did: the doll needed to be posed, the posing needed to be in a tourism setting, and so on. In addition, my made-up rule was that the posing needed to be based on what I knew of the touristic practice at the destination and what I imagined the activities might be. I had other rules that I tried to introduce in terms of what type of doll I would take, but, as we shall see, I was unable to adhere to them. Given that I set out with a particular purpose in mind, the play could be understood as goal-driven (ludic), but at the same time, it required a degree of creativity on my part and was also open-ended (thus paidia). An approach that is informed by phenomenology (of which more below) sees play as more open because ‘players follow and respond to play as they are engulfed by it’ (Massie 2018, p. 144, emphasis in original). I was, perhaps, not engulfed, but I was ‘doing’ play and this play was of the moment.

It is not my intention, however, to outline all the theorisations of play, as others have done this and to do so would be beyond the remit of this paper. An observation that I would make is that an issue that appears to arise repeatedly in some ‘play scholarship’ is attempts to pin down what play is, what functions it has, what different elements of play there are (see for example Henricks 2015, 2016; Eberle 2014), and to treat it as if it were somehow external to us. By contrast, anthropologist Thomas M. Malaby argues—as I do—for a move away from categorisation and, especially, for a reduction of play to either nonwork or representation. He argues for an understanding of play that draws upon a pragmatic philosophy of the ‘world as irreducibly contingent’ (Malaby 2009, p. 206). Viewed thus, play can ‘encapsulate…the open-endedness of everyday life’ (ibid., p. 208).

In part, Malaby draws on Csikszentmihalyi and Bennett (1971), arguing that ‘we may usefully take from [their work] the principle that play as a disposition is intimately connected with a disordered world that, while of course largely reproduced from one moment to the next, always carries within it the possibility of incremental or even radical change’ (Malaby 2009, p. 210).

As Malaby points out, the idea of possibility or continency makes links to a phenomenological philosophy and an experiential anthropology. In terms of the theoretical path that I wish to take for Mordaith’s journey, I draw on Merleau-Ponty’s Phenomenology of Perception (Merleau-Ponty 1962). Merleau-Ponty argued that understanding emerges from experience and that this experience is embodied: ‘[t]he world is not what I think, but what I live through’ (Merleau-Ponty 1962, p. xviii). For Merleau-Ponty, the world is not pre-given but is created by people as they move through life. We do not, therefore, come into the world with prior knowledge but choose from the different potentialities at hand and bring the world into being; we make it as we go. I have argued elsewhere that the disruption to habitus that can occur as part of touristic practice invites latent potentialities to come to the fore. In other words, the experiential, embodied aspects of tourism allow possibilities of being to emerge (Andrews 2009a). These possibilities of being are not given. For example, in a critique of the term ‘tourism imaginaries’ (Salazar 2012; Salazar and Graburn 2014), I argue that the imagination of tourism is brought about in the doing of tourism activity and that what we imagine is embodied in practice (Andrews 2017) rather than simply being based on prior knowledge of an otherwise fixed imaginary.

One proponent of an experiential anthropology is anthropologist Michael Jackson, who notes, ‘[w]e are continually being changed as well as changing the experience of others’ (Jackson 1989, p. 3). He cites William James’s observations that ‘our fields of experience have no more definite boundaries than have our fields of view. Both are fringed forever by a more that continuously develops, and that continuously supersedes them as life proceeds’ (James 1976, p. 35, in Jackson 1989, p. 3, emphasis in original). Given this, Jackson argues that who and how we are derives from our engagements with others in a world that is forever changing: ‘the “self” … is a function of our involvement with others in a world of diverse and ever-altering interests and situations’ (Jackson 1989, p. 3). The emphasis moves away from a categorisation of things to lived experience. Rather than trying to understand play as a category, or a number of categories, of behaviour, emphasis should be on the lived experience of those engaging in activities that they might or might not identify as play. In other words, it is about ‘[t]hings as they are’ (Jackson 1996): the ‘immediacy’ (ibid., p. 2) of the experience of play.

The focus, then, is on the experiential: the beingness of play. In Heideggerian terms, it is asking the question: what it is it to dwell in play? For Heidegger, ‘dwelling is the manner in which mortals are on the earth’ (Heidegger 1971, p. 148) and is the fundamental basis of being for humans, meaning how we are in the world, how we shape and move through the world, in effect building it as we go. Our dwelling and being in the world derive from our ‘throwness’, meaning that we are ‘thrown’ into a pre-existing world which we actively engage with and shape; it is a world of possibilities that will outlast us as individuals and, regardless of what we do, will have been changed by our presence and the activities with which we engage. In terms of tourism, the idea of being and dwelling has been explored by anthropologist Catherine Palmer. Influenced not only by Heidegger, but also by Tim Ingold (e.g., Ingold 1993, 1995, 2011), Palmer argues that their phenomenological approaches are useful for tourism ‘because it enables tourism to be located within the totality of life and of living’ (Palmer 2018, p. 21). For Palmer, tourism is a particular way of being (dwelling) in the world. The possibilities that tourism experiences offer means that, as with any aspect of lived experience, individuals are constantly making the world and themselves as they move (both literally and figuratively) along. Thus, there is no tourism experience or toy tourism experience, but rather a multitude of possibilities that are part of the overall ‘being’ of being alive.

In this paper, I offer a tentative exploration of the experience of a particular activity, that which has been labelled ‘toy tourism’ (Heljakka and Ihamäki 2017). Before I reach the story of my travels with Mordaith, I wish to briefly explore what can be understood by the term ‘toy’ and situate the discussion within a phenomenological approach.

4. What Is a Toy?

As the term play has been debated, so too has the definition of toy. Thibault and Heljakka (2018) argue that what is a toy is not easy to define, but that they are cultural objects. Thibault and Heljakka (2018) cite several dictionary definitions of toy, some of which have in common the positioning of toys as belonging to the realm of children. When toys are linked with adults, the definition relates to technical objects. As Thibault and Heljakka observe, however, restricting toys to an association with children misses adult toy play, and they point to an increase in purchases of toys for adult play as part of their argument.5 Thiabault and Heljakka go on to attest that the increasing presence of toys in contemporary culture points towards a ‘toyification’ in an ever more ludicised world. Without giving a definition of a toy, but adopting a semiotic approach, Thibault and Heljakka argue that toys are a ‘complex set of signs’ that have no fixed meaning and that meaning arrives in context (ibid., p. 7). Interpreting a toy in semiotic terms is, doubtless, at times useful, but what would be less useful is to understand a toy as simply an object that can be read or interpreted for its meaning. What interests me is the openness to possibility, the situating within context, which allows for the emergence of meaning and meaningfulness through practice—how something is brought into being as a toy.

Alan Levinovitz notes that a distinction can be drawn regarding play when considering whether the thing of play is a direct or indirect object of the verb. The former, he argues, is associated with a game: ‘one plays chess’, for example. The latter he links with toys: ‘one plays with toys’ (Levinovitz 2017, p. 269, emphasis in original). According to Levinovitz, the difference is beyond the grammatical because it also arises in practice. This is because, he opines, toys allow greater agency for the player compared to playing a game. Although Levinovitz resists the notion that there is such a thing as ‘pure toy’ (ibid., p. 284), he attests they should not be understood simply as objects but as ‘a unique moment of interaction between subject, object, and context’ (ibid., p. 271). Levinovitz goes on to argue that no object is ‘intrinsically a toy’ (ibid., p. 278) but only becomes a toy by virtue of its relationship to a person playing with it. For Levinovitz, toys are a speech act, they are objects that invite play. In other words, it is up to the person engaging with an object to determine if it is a toy or not. This, then, opens up a world of becoming, of possibility, to shape the identity of an object and bring it into being as a toy. For these moments, the world is being shaped through a disposition to ‘play with.’

I have argued elsewhere (Andrews 2005, 2009a, 2017) for understanding touristic practice as an embodied experience and that this entails a focus on, and recognition of, how the experience is experienced, that is, how practices are brought into existence, felt, resisted, embraced, and so on. As such, touristic practice unfolds in the doing, with all the potentialities that being a tourist presents, moment by moment. Given this approach, tourism shares with play and toys possibilities of becoming.

From the foregoing discussion, it is evident that tourism involves play and can be thought of as play. What is often attached to this play are material objects—the ‘play with’ element of sand, a bucket and spade, a football, and so on. As such, tourism and toys are intimately linked. It seems an obvious point that the material objects of play themselves travel. Quite simply, and putting aside adult toy play for a moment, children take toys on journeys. These trips could be as seemingly banal as taking a teddy in the pushchair when going to the shops or packing a bucket and spade for a day or more at the beach. Indeed, as Heljakka and Ihamäki (2017) note, many toys are designed with the idea that they will be portable in mind. They point to the Star Wars pocket-sized figures manufactured by Kenner as an example and further note that toys are sometimes given backstories that involve characteristics related to travel and are often sold with travel accessories. Heljakka and Ihamäki (2017) give a miniature camera as an example of a travel accessory, but we could also add suitcases and other accoutrements associated with being on holiday—sunglasses, flipflops, beach towels, etc. What is less obvious is that taking a toy on one’s travels is not just the preserve of children. The ‘toyification’ as part of an increasingly ‘ludicised’ world that, as Thibault and Heljakka (2018) discuss, extends to adult play with toys and includes travel with toys.

5. Toys That Travel

Shanna Robinson (2014) argues that it is probably impossible to identify when the first person took a toy travelling with them. What has made toy travel more visible is the advent of social media. It is worth noting, however, that even before toy travel became noticeable because of online sharing of travel accounts, travelling toys were in the news media and appearing in films and television programmes. For example, the artist and filmmaker Derek Jarman’s diaries, written between 1989 and 1990 and published as Modern Nature in 1991 (Jarman 1991), are mainly about his garden in Dungeness, on the southern coast of England. One journal entry recounts a story about a garden gnome that occupies a space in the centre of a garden lawn, gazing at a pond in front of him in a garden in Somerset, southwest England. One night, the gnome disappears. A week later, the owners receive a postcard from Switzerland, detailing the snow and plans to ascend the Matterhorn. It is signed ‘the gnome’. More postcards follow, describing the sights and experiences of the gnome’s travels that saw him visit other parts of Europe and parts of Southeast Asia. Almost a year later, the gnome arrives back at his spot in the garden as silently and mysteriously as he had left; only now, he is tanned and wearing dark glasses.

Jarman’s example is not the first instance of a travelling gnome. The earliest record of gnome travel is from the 1970s, when Henry Sunderland photographed two of his gnomes whilst in Antarctica. The first report of a stolen gnome travelling came from Australia, in 1986. Since then, there have been numerous stories of gnomes being taken on holiday by their owners or stolen for travel purposes and then returned. In addition, the travelling gnome has become a feature of popular culture, appearing, for example, in the British TV soap opera Coronation Street, the 2001 film Amélie, and several video games.6

Gnomes are a very particular material form of toy. The type of toy travel that both Robinson (2014) and Heljakka and Ihamäki (2017) refer to is the more ‘conventional’ understanding of a toy in the form of a doll, soft toy, or travel bug7. For Heljakka and Ihamäki, all these forms relate to ‘toys that travel in the name of toy tourism’ (Heljakka and Ihamäki 2017, p. 184, emphasis in the original); this activity can take place when: (1) individuals take a toy/toys on holiday; (2) a toy(s) is sent to a host as part of a hosting programme, either privately or through a specialist travel agency; or (3) through geocaching8 activities. In Rebecca Williams’s (2019) research, she describes how fans take what she calls paratexts (that is, dolls, action figures, soft toys, or, in her case, a Hannibal Funko Pop! Vinyl, based on the Hannibal Lecter films and TV shows) to meaningful story locations that allow the player to extend the attendant narrative in a playful manner.

For Robinson, travelling with a toy is an example of vicarious travel which highlights the ‘importance of the performance of embodied experimental tourist encounters’ (Robinson 2014, p. 149). She also links the practice with the importance of the imagination in tourism, but argues that in discussions of ‘tourism imaginaries’ little attention has been paid to ‘what the process of imagination actually involves’ (Robinson 2014, p. 151, emphasis in the original). The mention of travel bugs, soft toys, and dolls, along with those toys identified by Williams, gives an insight into the range of toys that travel. Heljakka has, for example, conducted research with Blythe dolls (e.g., Heljakka 2023) and Uglydolls (e.g., Heljakka and Räikkönen 2021a), among others. Yildiz et al. (2023) focused on soft toys in organized tours of Berlin, in which a teddy or teddies (bears or other creatures) are sent independently of their owners to Berlin to be hosted by specialist guides. Yana Wengel (2020) has used both Lego and Serious Play to research tourism and hospitality, whereby the use of both is seen as a mechanism to understand host–guest relationships in volunteer tourism.

Overall, toy tourism is a niche activity in tourism and there is little academic literature on the topic. How widespread the practice is remains unclear. An anecdotal observation is that, whenever I recount my story, the listener invariably knows someone who travels with a toy. How many and how often are, however, not the issues; it is the fact that it happens at all that indicates that it has sociocultural value and is therefore worthy of investigation.

As noted above, my reasons for embarking on the toy tourism journey were to understand what it is like to practice. What it is like to practice is inevitably bound up with my embodied experience, my emotions and thoughts, the imagination around the playing, and the touristic activity that I evoked in my doing. It is embedded in an experiential and phenomenological perspective that interweaves with tourism as play and the bringing into being, by me, of a toy I have named Mordaith, who I shall now introduce. The play value of a toy is, according to Heljakka and Räikkönen, in part derived from ‘the relationship the player builds up with the toy’ (Heljakka and Räikkönen 2021a, p. 4). For me, this relationship began with the choices I made that led me to Mordaith, which is the subject of the next section.

6. Becoming Mordaith

Mordaith (Figure 1) retails as a Barbie Fashionista doll. The Fashionista line of Barbie dolls was launched in 2009: seven dolls with the names Glam, Cutie, Girly, Wild, Sassy, Artsy, and Hottie (the latter being a Ken doll). Prior to release to market, four of the female dolls had featured in a promotional music video. In subsequent years, more characters were released, with some being renamed (e.g., Girly was renamed Sweety in 2010). There were also related products, including an animated series, Barbie Life in the Dreamhouse, that gave names to new dolls in the series, games, more animation, and quizzes on the various Barbie related web pages. The Barbie Fashionistas Swappin’ Styles app was released in 2010 but discontinued in 2012. Another app was launched in 2016.9 The same year saw an expansion of the Fashionista range, with the addition of new body types that included varied sizes—tall, curvy, and petite—seven skin tones, twenty-two eye colours, twenty-four hairstyles, and a range of different clothes.

Figure 1.

Mordaith (photo author).

In her packaging of a pink and clear vinyl bag, Mordaith is dressed in a short-sleeved, short orange dress with a white flower pattern and ruffles. She has cream platform sandals and a goldy-orange hairband in her long, dark, wavy, thick, flowing hair.

Unlike some other dolls in the range, she has the original Barbie body type. According to the Mattel website it is ‘a super-trendy look.’10 Her arms and legs move, and it is possible to rotate her head. She has, however, no elbow or knee joints, and so she is not very manipulable. She is not supposed to be able to stand alone, but rotating her legs at the sockets with her body does make this possible. Mordaith has light brown eyes and a bright smile formed of two red lips parted by a solid white stripe representing a row of perfectly formed teeth. In her platform footwear, Mordaith is about 30.5 cm (12 inch) in length; she has a well-proportioned model body.

I must confess that when deciding to experiment with taking a doll with me on my fieldwork, Barbie—or a Barbie-related product, that is, a Fashionista—was not my first choice. I was making a conscious effort to not take such a doll. Although I had craved a Barbie doll as a young child, I was not able to have one. My reasons for not wanting a Barbie had nothing to do with my lack of bonding with Barbie as a child but more to do with practicalities and other sensibilities. In the case of the former, I was looking to buy something as cheap as possible with a view to having something very portable and poseable. Something pocket-sized would have been ideal. I wanted to avoid the ideal that Barbie represents—the blonde, perfectly proportioned woman with a great lifestyle of access to a variety of careers, a car, a home, endless amounts of fashionable clothing, and an idealised partner, in the form of Ken. Since Barbie’s beginnings, she has courted criticism and controversy11, and Mattel have responded by changing the doll or introducing new ranges12, as is the case with the Fashionistas. Regardless of these moves to reflect a more diverse world, a Barbie was not my first choice.

To keep costs down, I visited second-hand shops, locating the toy sections and sifting through the dolls. On my first day of looking, I thought I had found exactly what I wanted: a pocket-sized doll with articulated knee and elbow joints and a waist that could be turned. These features made her easily poseable. Like nearly every other doll in the pile, she was sold without clothes. I bought her for GBP 0.20, believing that I would be able to easily cloth her, but I could not.

Given that many toys are designed to travel, I started my search again, resigned to the idea that I would have to buy something new. Reviewing the various possibilities based on price and accessories, and mindful of my impending departure to Mallorca, I settled on a Barbie Fashionista. She was consciously chosen for her tanned skin and dark hair, to avoid the stereotypical Barbie of white and blonde.

When she arrived, I decided that I was going to move away from her Barbie credentials by renaming her and eventually giving her a new backstory. In fact, her makers had not given her a name, other than Barbie Fashionista Doll #182. Thus, the first stage of reducing the gap between me and the doll was to name her. Because I live in North Wales, and the purpose of my purchase was for reasons relating to travel, I wanted a name that reflected both something Welsh and travel. I played around in Google translate with words for tourist, traveller, and voyager (the latter inspired by the 1942 film Now Voyager, starring Bette Davis). The word, translated into Welsh, that seemed the most attractive and pronounceable to me was for voyager, which came up as mordaith. So, Barbie Fashionista #18213 became Mordaith. On closer inspection, the word mordaith actually translates as voyage or cruise; voyager is mordeithiwr.14 Given, however, my limited command of the Welsh language, especially in terms of pronunciation (I would later need to pronounce Mordaith’s name), I stuck to Mordaith. The link to cruises made it even more meaningful to me, as the experience of the cruise in Now Voyager is what brings Bette Davis’s character to life. An advantage to having a Barbie doll with the original body shape and size was that I could provide Mordaith with a couple of changes of outfit to take away with her for the different spaces in the resorts that we would visit.

Ivanov (2019) in (Heljakka and Räikkönen 2021a, p. 1) argues for a consideration of the non-human traveller in tourism. From this perspective, the views of both sentient beings (e.g., dogs) and inanimate objects (e.g., toys) should be explored. Tourism, however, is a human activity; it is derived from people. Any activity in the name of tourism, whether by people, dogs, or toys, is based in how people shape their experiences. Of course, the well-being of an animal that travels needs to be taken into consideration, but it is not possible to recount the experience from the perspective of a creature that has no concept of what tourism is. Similarly, a toy cannot express an understanding of what tourism is, cannot express emotions or thoughts, only those that we imagine and, thus, attribute to it. It might be the case that we externalize our inner thoughts and emotions in the Durkheimian (Durkheim 1912) sense by projecting them onto something else. In this respect, Mordaith’s tale is my tale. I did not relate to her as standing for me or as an avatar, as some toy tourism players have (Heljakka and Räikkönen 2021a). Rather, in a playful way, I imagined her primarily as a holidaymaker in the youth market and tried to insert her into situations that I knew from previous research had been this market’s activities. What follows is a recounting of what I did. In this account, what was not anticipated as part of this exploration was how some of the adults in the resorts responded to the presence of Mordaith and how, in turn, this proved to be a useful ethnographic tool.

7. The Tale Begins

I am packed and ready to go. Mordaith is in her carry-bag and will travel with me on the plane, in my rucksack. I make this decision because I do not want to lose her or be without her should my hold bag go missing en route. I do not really think about her during the journey, although I do have an awareness that she is with me in the bag. I arrive at the apartment in Palmanova. It is late. I suddenly think, ‘I’d better record her arrival’, so I sit her in one of the apartment chairs and take her photo (Figure 2). I return Mordaith to her carry bag.

Figure 2.

Mordaith in the apartment room on arrival (photo author).

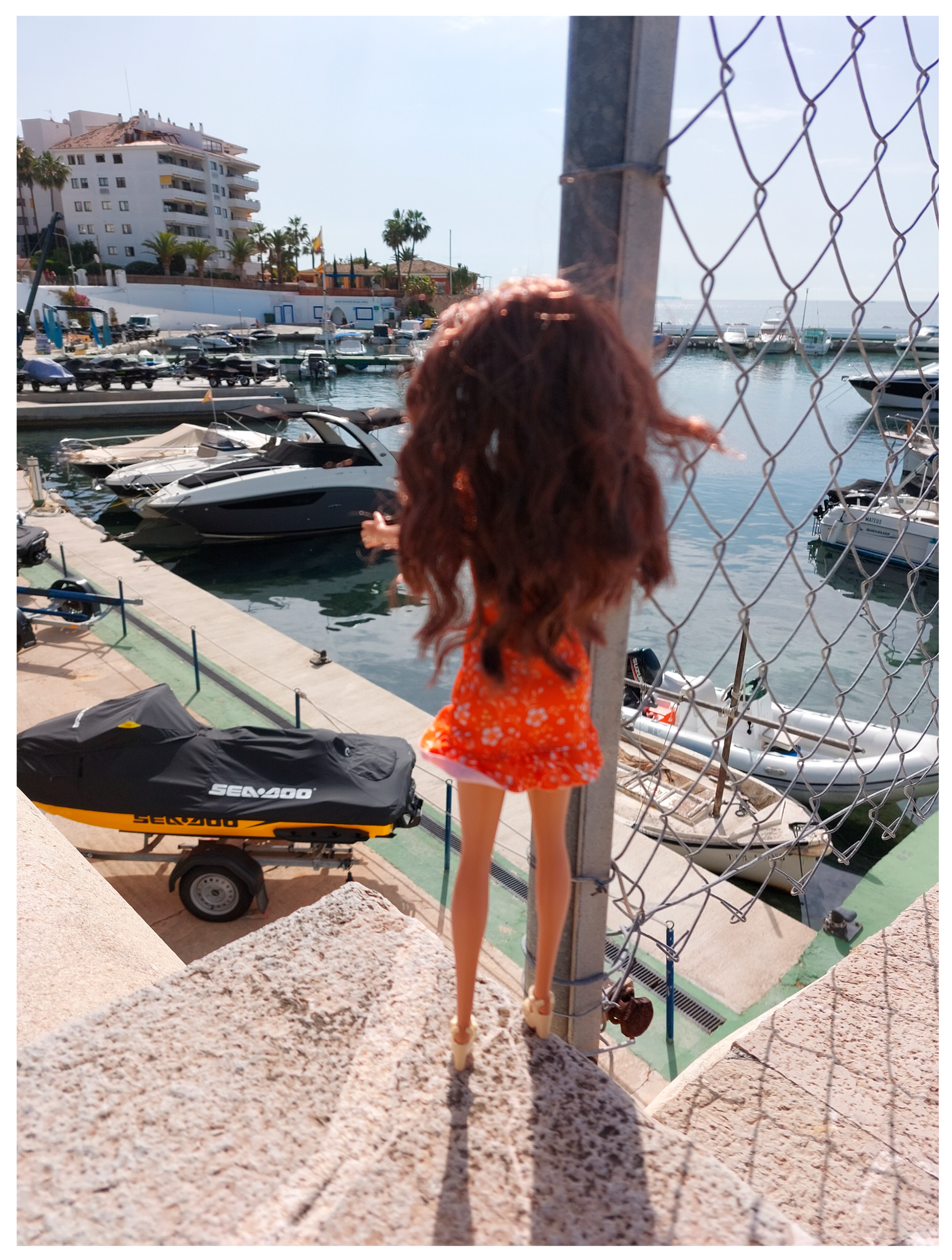

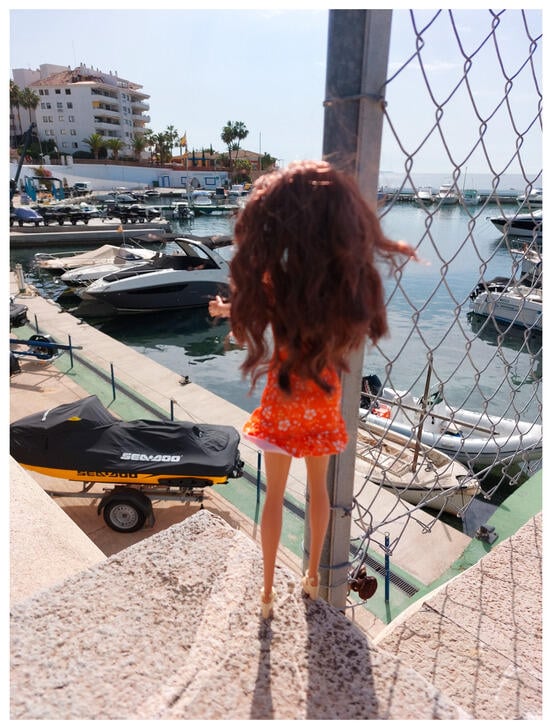

The next day, we go for breakfast. Mordaith is in the rucksack. I have finished eating and remember again that I have a doll with me, so I sit her on the table next to the virtually empty plate and a partially drunk glass of orange juice and take her photo. I feel quite self-conscious, so I quickly returned her to the rucksack. We head out. We are staying in an apartment at the most easterly point of Palmanova, on Passeig Mar. Across the road is the Bay of Palma. There is a small marina. I see other people stopping to look at the boats and decide that this is a good place to pose Mordaith—this is tourist activity. So, out of the rucksack she comes, and I take her photo as she looks at the boats (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Looking at the boats, Palmanova (photo author).

We continue our journey. I want to walk from Palmanova to Magaluf, retracing the journey I undertook as part of the first stages of my fieldwork in the resorts in the late 1990s. We periodically stop to look at the places that were once very familiar to me. I am keen to involve Mordaith in activities that I think would fit the kind of photos that people share on social media about their holidays.

However, as my fieldnotes indicate, ‘getting Mordaith out is a bit of a pain—get her out, pose her. It’s like having to keep changing between sunglasses and glasses all the time.’15 What makes this worse is that the getting out and putting back is accompanied by taking off and putting on my rucksack. This also contains my notepad and pen. To try to minimise my irritation and be more efficient, I decide to look for a small, casual bag that would accommodate my things and be more accessible than being carried on my back.

For it to be the right bag, Mordaith must fit inside. Despite looking in (what seems like) every bag shop in Palmanova and Magaluf, I cannot find a bag that I find suitable. Back at the apartment, I experiment with fitting Mordaith and the things I need to take out with me into my handbag, which can be worn cross-body, making it accessible without my having to take it off. Mordaith would fit if I bent her from the top of her legs and inserted her into the bag feet first. This is a workable solution for me, so on subsequent outings this is Mordaith’s mode of transport.

We stop at various points in both resorts, sometimes for refreshments (Figure 4), at other times just to rest. The weather is warm and sunny, so finding shade and having drinks is important.

Figure 4.

Mordaith taking a break (photo author).

It is April, and the 2023 tourism season is at its very beginning. Not all of the sunbeds and parasols have been set out on the beaches. Sunbeds are stacked on top of each other. I pose Mordaith on top of a stack of sunbeds and in the sand next to them. That is it for that day; Mordaith returns to the bag and stays there until we get back to the apartment.

The next day continues in much the same vein. We are still exploring the resorts, finding out what has changed, and engaging in participant observation of touristic practice. Although I have resolved the issue of the bag, I am still faintly irritated by Mordaith, as my fieldnotes indicate: ‘the thing about Mordaith is she is always smiling’. I think I was annoyed because, although Mordaith is a Barbie Fashionista, she is, nevertheless, an idealised representation of a woman, and Magaluf can be a problematic environment for women to navigate.

My previous periods of research in the resorts highlighted gendered inequalities based on the overt sexualisation and objectification of women for the benefit of men, stereotypical notions of the division of labour between the domestic and non-domestic spheres, and casual misogyny all in the guise of fun (see for example Andrews 2009b, 2014). Although some attitudes may have changed (there is evidence of men being sexualised and objectified in what is still an ostensibly heteronormative environment), it remains the case that women and men are represented differently, and the casual misogyny remains.

I find it irritating, therefore, that Mordaith smiles through it all, but then she is an inanimate object. Also, if, as Heljakka and Ihamäki contend, toys can be ‘avatarial extensions of players’ (Heljakka and Ihamäki 2017, p. 195), this is not working for me because I am not smiling. It is also the case that during my earlier periods of research not all women found the casual sexism displayed in the resorts worthy of a smile.

The story is not over, however. My attitude changed on our first foray into Magaluf for the resort’s nightlife.

We enter Punta Ballena, the infamous main strip of Magaluf, with its concentration of bars and nightclubs. It is not very busy owing to the time of year and the time of the evening; it is still early by Magaluf standards. We near the end of the road when two young women try to encourage us to go to the bar at which they are working with the offer of two free shots each. The offer of a free drink is a common ploy used by many of the bars in the resort to get punters into a bar or nightclub. Competition is high for custom, especially when tourist numbers are low. At first, we decline, but then change our minds, opting to sit outside the bar where we can watch the evening unfold. We have our shots and a couple of drinks. Mindful of the need to record what is happening to share it later, I pose Mordaith inside the bar, at one of the doors, sitting with a drink on the table. She is doing what a young woman holidaying in Magaluf might do—going into a bar or sitting outside and having a drink (Figure 5 and Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Outside a bar on Punta Balena (photo author).

Figure 6.

Inside a bar on Punta Balena (photo author).

As the evening proceeds, we are offered more shots, but this time to purchase. They are sold as 20 mL bottles and carried on a white tray by the shot seller. We are among a few people who are customers, and as time goes by the person selling shots spends time talking with us. Mindful of scale, the shot bottles are a more appropriate size for Mordaith than a glass, and I think that it would be a good idea to take her photo sitting on the tray with the shots. As good ethical practice dictates, I must get informed consent for what I would like to do. I explain to the shot seller what toy tourism is and immediately distance myself from the practice; it is not me who is a player, I am just experimenting: ‘I find it weird, so I wanted to give it a go’. My separation from the activity was because I felt rather stupid. Although adult toy play is increasingly recognised, I nevertheless felt some discomfort with carrying a toy.

We talk a bit about how a stuffed toy in primary school classes is taken home by each child in turn, and when they take it back into school the child tells the story of the toy’s time with them. We note the similarities, but I emphasise that, in my version, it is adults who are players. The shot seller responds by saying ‘it’s a new one on me’. I pose Mordaith in the tray and the shot seller also takes a photograph. I ask if I could get her photo with the male PR16. My thinking behind the request for a photo with the PR is that these workers are sometimes key figures in the landscape of Magaluf. Their often-flirtatious mannerisms when trying to appeal to prospective customers contributes to the sexualised atmosphere of the resort. It was the idea of a male PR engaging with a potential female punter that I was trying to capture. The PR agreed to having his photo taken with Mordaith and, in so doing, offered to kiss her or hold her in front of his genitals. I declined both.

It was this sexualisation of Mordaith that changed my relationship with her. Suddenly, she seemed vulnerable, in need of protection. Mordaith was not playing me in the images that I was capturing; for me, she was representing a young woman on holiday (later, I think about developing her backstory for the Instagram account that I will eventually set up, and I place her in her late teens). It seemed that many of the issues regarding the objectification and sexualisation of women that I identified from my previous fieldwork remained.

For the remainder of the fieldwork, I continued to pose Mordaith in various tourist settings: in cafes, on the beach, on the promenade, out in Magaluf, etc. It all seemed perfunctory and a mere visual chronical of my movements around Palmanova and Magaluf with a toy in tow. I did, however, feel less irritated by Mordaith and stopped noticing or being bothered by her constant smile. In any event, photos of holiday experiences generally show happy, smiley people, so Mordaith’s facial expression fitted with the activity. Putting the doll away at the end of the day and preparing her for trips out by changing her outfit for walking around, being on the beach, or going out in the evening, with the limited supplies of clothing that I had for her, became the routine. It would be dull for me to recount every instance of posing Mordaith. These were conscious efforts to enact what I thought might be typical touristic practices in beach resorts like Magaluf and Palmanova: looking at views, lying on the beach, and playing in the sea. A difference emerged with two breaks from the routine.

The first scenario was during the day in Magaluf. It was another day of exploring the resort, trying to get an understanding of the changes (and similarities) since previous visits. We walked past a tobacco shop and the entrance to a nightclub that looked both familiar and strange at the same time. The strangeness came because the tobacco shop was once a large bar, open both during the day and at night. The familiarity came from the entrance to a nightclub. I remembered there was a nightclub there and that it was one I had visited in the late 1990s. The name change, and the change in use of the adjoining bar, momentarily confuse me; am I in the location that my memory tells me I am? There is a young man outside the nightclub entrance, so I ask him if the establishment used to be called by another name. As I am speaking to him, we are joined by one of his co-workers—who I shall call Paul—and we chat for a bit about the name change and another adjoining premises. Paul notices Mordaith’s hair sticking out of my bag (I have not noticed that it is open) and asks:

‘What’s that you’re carrying around with you? Is it a wig?’

I take Mordaith out and explain, ‘there’s this thing called toy tourism.’

Paul asks, ‘what’s that?’

‘People take a toy on holiday or send a toy on holiday with a travel agent.’

Paul: ‘What do you mean?’

I explain that this is about adults taking a toy on holiday and posing it, instead of taking a selfie for social media purposes, but that in some instances, a toy gets sent to someone for a holiday. I explain that I am a researcher and that, because I find the phenomenon strange and interesting, ‘I thought I’d give it a go’.

Paul asks, ‘is she having a good time?’

‘She is. She’d like to have her photo taken with you; will you pose with her?’

Paul agrees, and he holds one of Mordaith’s hands while his co-worker (who appears less sure about what is happening) holds the other. I take the photo. Paul is clearly amused, and asks for a photo to be taken on his mobile phone. He then offers me free entry into the nightclub for the next night so that I can see the changes from when I was last there.

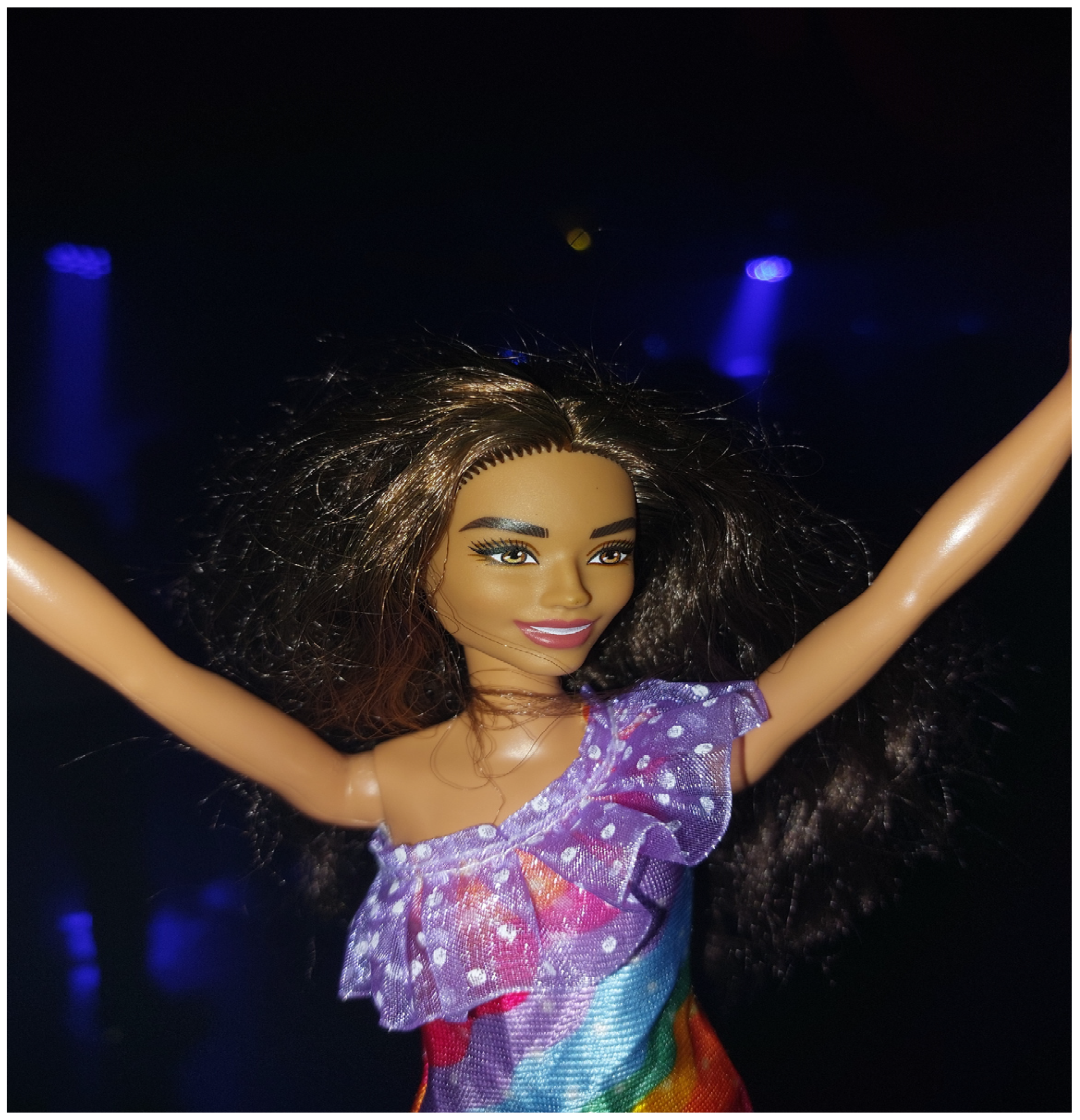

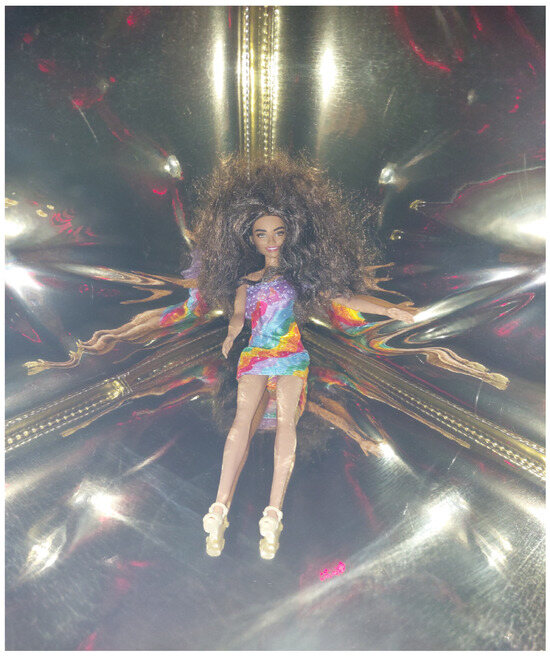

The next night, we go to the nightclub. The interior has changed; gone is the big-screen TV in the middle of the dancefloor, and the space is entirely open. Down one side of the room is the bar (the same as before), and on the opposite side, comfortable low chairs are arranged around small tables. The arrangement is booth-like in style and designed to accommodate small groups. At the far end of the room, before the access to the toilets, stands the DJ; at the end nearest to the entrance and exit, someone is playing a set of bongo drums. For a nightclub, it is still early (before midnight), so it is not very busy. We buy drinks and, at first, intend to sit on one of the low, comfortable chairs, but as these are designed for groups, we are asked to move. We go to stand near the bar, where there are some bar stools. As time goes by, the nightclub gets busier, and people are dancing (to music I do not recognise). This is Mordaith’s opportunity to experience clubbing; she has tried out the comfortable chairs (Figure 7), stood with a bottle of alcohol (Figure 8), and danced (Figure 9).

Figure 7.

Enjoying a nightclub on a comfortable chair (photo author).

Figure 8.

Enjoying a nightclub with a drink (photo author).

Figure 9.

Enjoying a nightclub dancing (photo author).

It is hard to photograph Mordaith dancing. I must hold her by both legs, with my arm stretched out, as I try to position my phone and keep everything steady. At this point, her smile is definitely no longer annoying. To me, she looks truly delighted, enjoying an atmosphere of shared exuberance for the lively music and the energy of groups of people dancing together. In fact, she is in a far better position to dance than me, for, as another punter asked me, ‘don’t you feel a bit out of place here?’ He is referring to the distance between my age and those of most of the other customers—including himself—to which, I might add, my lack of knowledge about the music being played. I could not dance to it, but I could play pretend dance with Mordaith.

It is 2 a.m., and we decide to leave. On our way out, I go to thank Paul for inviting me to visit the club. He seems surprised to see me: ‘oh, you’re still here. You’re the lady with the doll, right?’ I confirm that I am, and I thank him again before we make our way out and begin the walk back to the apartment.

The next incident happens earlier in the day of the visit to the nightclub. I have arranged to meet a colleague from the University of the Balearic Islands and join a tour in Palma with some students and another colleague visiting from Austria. My friend from Palma is speaking about the problems faced by the city that result from tourism. We visit key sites, including the building that was the first hotel, a public square, the walls of the cathedral (which allow a view over the bay), and La Lonja, which for us is the final stop before returning to the resorts.

Before departing, I am invited to tell the students about my experiment with Mordaith. She has been waiting patiently in my bag, having spent most of the day confined to it. I take her out and briefly explain what toy tourism is, who Mordaith is, and where her name comes from. I show pictures of her time in Magaluf and Palmanova. Of course, some students show more interest in what I am saying than others, but many crowd round to see the photos and are interested to know if she has an Instagram account. I am pleased by the interest that the students appear to show in what I am doing.

My visit to Mallorca ends. Once again, Mordaith is packed away in her carry-bag and stowed in my rucksack for the flight home. Once back, I create—with the help of my children—an Instagram account, at which point I start to think about a backstory. Mordaith sits on my desk, watching me, still smiling. My desk is cluttered, so after a few weeks I decide to return her to her carry-pack; added to that, she might get dusty if I leave her sitting out.

8. Playing at Being a Toy Tourist

I set out on this journey to try to understand what it feels like, as an adult, to take a toy on holiday. I had little idea of where it would lead me or what kind of narrative, if any, would unfold as a result. How my intention to play at toy tourism would manifest was not a given because, until I was practicing, I had no experience of it. As Massie argues, ‘play modifies the players’ behavior while simultaneously allowing them to change the rules and the meaning of the game constantly leaving open the possibility of taking it in another direction’ (Massie 2018, p. 145). Mordaith modified my fieldwork behaviour; she brought another dimension to it. I have already outlined the proposals that I set to shape my play; the rest was open to negotiation with the conditions I found in situ. I could not foresee what would happen because, for this type of play, ‘the outcome can never be predicted; in fact [it] may very well have no outcome’ (Massie 2018, p. 145).

Experience is of importance here because it is a word that has had increasing purchase on life. Many things, among them tourism, have been labelled ‘experiences’. As Clifford Geertz notes, ‘individuals no longer learn something or succeed at something but have a learning experience or a success experience’ (Geertz 1986, p. 374). To reduce the moments of our lives to an external, graspable, reified, and objectified reality, called an experience, misses the way in which humans live and dwell in the world as it is present at any given time. As Jackson, in reference to Satre (1968), argues, ‘our humanness is the outcome of a dynamic relationship between circumstances over which we have little control … and our capacity to live those circumstances in a variety of ways’ (Jackson 2005, p. xi, emphasis in original).

When I was wandering around Palmanova and Magaluf, I was simply doing that. I would often forget about my toy tourism project and had to make a conscious effort to take Mordaith out of the bag and pose her. It was as if my sense of flow, or simply being, was interrupted by a chore. At other times, I was very aware of Mordaith’s presence and it felt natural, or ‘normal’, for her to be part of what was going on. I had limited control over how the activity would work out. It is the case that I posed her, and I chose where, but I had no control over how others would react to her presence, and in one case (outside the nightclub), the encounter was purely serendipitous, but it opened a door to entry into a nightclub, one that, arguably, I would otherwise have found difficult to achieve.

Through my actions, regardless of whether consciously or not, I was bringing moments of play into being—I was playing, using Mordaith as a research tool. Unlike those players who engage in toy tourism as part of their touristic practice (see Heljakka and Ihamäki 2017 for examples), Mordaith was not a stand-in for me because I was researching, and that involved a double layer of play: firstly, the element of play that occurs in much fieldwork, as noted by Crick (1985) and Taylor (2022), and my role as a tourist, and secondly, the added layer of playing at being a toy tourist.

This move between forgetting and remembering Mordaith, the double play, and play as contingency, outlined by Malaby (2009), suggests that what the play is comes about through practice. Play is in the doing. It is not external, graspable, or fixed because it happens in the moment of doing: a moment that is immediately gone. What my toy tourism play was (or play in tourism in general, or tourism as play), and how I experienced the experience of playing became apparent in what Jackson and Piette describe as, ‘lived reality [which] makes its appearance in real time, in specific moments, in actual situations and in … continually shifting from certainty to uncertainty, fixity to fluidity, closure to openness, passivity to activity, body to mind, integration to fragmentation, feeling to thought, belief to doubt’ (Jackson and Piette 2015, pp. 3–4).

Both Mordaith and I were ‘thrown’ into the world of tourism that exists in Palmanova and Magaluf. I brought Mordaith into being in the role of tourist by using my imagination. Elsewhere, I have discussed the importance of conceptualising the imagination as embodied (Andrews 2017) and drew on the work of Tim Ingold to note that the imagination is not only ‘a capacity to construct images… but more fundamentally as a way of living creatively in a world that is itself crescent, always in formation. To imagine…[is]…to participate from within, through perception and action, in the very becoming of things’ (Ingold 2012, p. 3). Understanding imagination in this way responds to Shanna Robinson’s (earlier stated) argument that, on the whole, discussions of the imagination in tourism have tended not to consider the process of imagining. Instead, the idea of tourism imaginaries discussed by Salazar (2012) and Salazar and Graburn (2014), as previously noted, has tended to treat the imagination as external to the self, rather than thinking that what we imagine is embodied and practiced in the experience of doing and, thus, is not fixed before the encounter but is forever being conjured (Andrews 2017).

My experiment with toy tourism was an effort to illuminate the process involved. My understanding of toy tourism may not (if ever) be complete, but I have more understanding of it now because I have ‘lived through’ (Merleau-Ponty 1962) the doing of it. The doing took place in a package holiday setting with a reputation for party tourism, which is different from previous studies of toy tourism/toyrism. The aim of this research was not to comment directly on the role of toy tourism in relation to ideas such as photoplay or the functionality of the toy as avatar, co-creator, storyteller, or influencer (Heljakka and Räikkönen 2023). What the previous work by Heljakka (2018); Heljakka and Ihamäki (2017); Heljakka and Räikkönen (2021a, 2023); Williams (2019); and Yildiz et al. (2023) demonstrates is that adult toy play is good to think with. My contribution adds to this by emphasising the usefulness of a toy as a tool as part of an ethnographic inquiry in a tourist setting, as a means to engage with interlocuters and, thus, open the field in an even more unpredictable way than I might have imagined.

The play arose through my embodied imagination of playing, through the movement of Mordaith in and out of my bag, through the manipulation of her limbs as far as it was possible to pose her, through changing her outfits, through my emotional disposition towards her, and through the interest that others I encountered in the field expressed about what I was doing. These things were always in flux and being brought to the fore. There was no certainty of the play involved and, as such, no certainty that Mordaith, as a toy, would be present. As an object, Mordaith is moulded plastic; through my practice, I brought her into being as a toy dwelling in the experiment of my lived experience of playing at toy tourism, in which I was open to a world of possibilities that being with Mordaith brought about.

9. Is This an Ending?

Most stories have an ending. My story with Mordaith does not. To return to William James, ‘our fields of experience have no more definite boundaries than have our fields of view. Both are fringed forever by a more that continuously develops, and that continuously supersedes them as life proceeds’ (James 1976, p. 35, in Jackson 1989, p. 3, emphasis in original). Since the visit to Mallorca recounted here, Mordaith has returned for another visit, but that is another story to be told another time. In the meantime, Mordaith keeps smiling: @mordaith.voyager17.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The research was undertaken in accordance with Liverpool John Moores University’s policy on research ethics.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | From the poem Alphabets by Josef Knecht as recorded in The Glass Bead Game by Herman Hesse ([1946] 1969). |

| 2 | The ‘we’ referred to in the recounting of my experience with Mordaith refers to me and my husband. |

| 3 | I acknowledge British is a contested term. For more discussion on this see (Andrews 2011). I use British as a form of short-hand as opposed to using the individual ethnic descriptors from the UK and Northern Ireland—to avoid constantly stating Welsh, Scottish, English, Northern Irish. |

| 4 | Cohen had developed a typology of tourist in earlier work—notably his 1979 paper A Phenomenology of Tourist Experiences in which he argued for five modes of touristic experiences. As Cohen himself acknowledges at the end of his exegesis, his argument is ‘highly speculative’ (p. 198). It is also very generalised and lacking in engagement with what actual touristic practice is to understand what tourists are saying and doing and what they are saying about what they are doing. |

| 5 | In support of this, in 2023 the Guardian newspaper reported that world famous toy shop Hamleys in London targeted the £1.2bn trend in adult toys in its 2023 Christmas campaign. https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2023/sep/21/hamleys-kidults-top-10-toys-for-christmas-2023?CMP (accessed on 22 September 2023). |

| 6 | https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Travelling_gnome (accessed on 12 September 2023). |

| 7 | A travel bug is an item used in geocaching that has a unique tracking tag and can be attached to things and gives goals to others to attempt to finish (https://shop.geocaching.com/default/trackable-items/travel-bug.html (accessed on 13 September 2023)). |

| 8 | Geocaching is an outdoor leisure pursuit in which players use a combination of navigational devices to conceal and find geocaches in places marked by geo-coordinates (see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Geocaching for further details). |

| 9 | https://barbie.fandom.com/wiki/Fashionistas_(Doll_Line)#2009 (accessed on 10 July 2023). |

| 10 | https://shopping.mattel.com/en-gb/products/barbie-fashionistas-doll-182-hbv16-en-gb (accessed on 10 July 2023). |

| 11 | See for example Claudia Mitchell’s and Jacqueline Reid-Walsh’s paper in which they note Barbie has been situated as ‘the most problematic cultural icon of girlhood’ (Mitchell and Reid-Walsh 1995, p. 143). |

| 12 | https://www.britannica.com/topic/Barbie (accessed on 10 July 2023). |

| 13 | Although on some websites she is Barbie Fashionista Doll 6. |

| 14 | University of Wales Dictionary https://geiriadur.uwtsd.ac.uk/index.php?page=ateb&term=mordeithiwr+&direction=we&type=all&whichpart=exact&search=#ateb_top (accessed on 8 January 2024). |

| 15 | As someone who relies on glasses to see clearly, I need to change between sun and ordinary glasses as a move between inside and outside spaces. I find it can be irritating. |

| 16 | PR/PRs refers to the young men and women who stand outside bars and clubs in Magaluf with the sole purpose of trying to encourage customers into the premises. Their approach can be sexually flirtatious. |

| 17 | If you would like to connect with Mordaith on Instagram please contact the author direct. |

References

- Andrews, Hazel. 2005. Feeling at Home: Embodying Britishness in a Spanish Charter Tourist Resort. Tourist Studies 5: 247–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, Hazel. 2009a. Tourism as a ‘Moment of Being’. Suomen Antropologi 34: 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, Hazel. 2009b. “Tits Out for the Boys and No Back Chat”: Gendered Space on Holiday. Journal of Space and Culture 12: 166–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, Hazel. 2011. The British on Holiday: Charter Tourism, Identity and Consumption. Bristol: Channel View. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, Hazel, ed. 2014. The Enchantment of Violence: Tales from the Balearics. In Tourism and Violence. Farnham: Ashgate, pp. 49–67. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, Hazel. 2017. Becoming Through Tourism: Imagination in Practice. Suomen Antropologi 42: 31–44. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, Hazel. 2023. Tourists and the Carnivalesque: Partying in the Land of Cockaigne. Journal of Festive Studies 5: 167–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caillois, Roger. 1961. Man, Play and Games. London: Thames and Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Erik. 1985. Tourism as Play. Religion 15: 291–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crick, Malcolm. 1985. Tracing the Anthropological Self: Quizzical Reflections on Field Work, Tourism, and the Ludic. Social Analysis 17: 71–92. [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihalyi, Mihalyi, and Stith Bennett. 1971. An Exploratory Model of Play. American Anthropologist 73: 45–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durkheim, Émile. 1912. The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life. Translated by Joseph Ward Swain. London: George Allen & Unwin. [Google Scholar]

- Eberle, Scott G. 2014. The Elements of Play: Toward a Philosophy and a Definition of Play. Journal of Play 6: 214–33. [Google Scholar]

- Geertz, Clifford. 1973. The Interpretation of Cultures. New York: Basic Books Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Geertz, Clifford. 1986. Making Experience, Authoring Selves. In The Anthropology of Experience. Edited by Victor Witter Turner and Edward M. Bruner. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, pp. 373–80. [Google Scholar]

- Godbey, Geoffrey, and Alan Graefe. 1991. Repeat Tourism, Play and Monetary Spending. Annals of Tourism Research 18: 213–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottlieb, Alma. 1982. Americans’ Vacations. Annals of Tourism Research 9: 165–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyimóthy, Szilvia, and Reidar J. Mykletun. 2004. Play in adventure tourism: The Case of Arctic Trekking. Annals of Tourism Research 31: 855–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handelman, Don. 1974. A Note on Play. American Anthropologist New Series 76: 66–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haywood, Les, Francis Kew, Peter Bramham, John Spink, John Capenerhurst, and Ian Henry. 1990. Understanding Leisure, 2nd ed. Cheltenham: Stanley Thornes. [Google Scholar]

- Heidegger, Martin. 1971. Poetry, Language, Thought. Translated by Albert Hofstadter. New York: Harper & Row. [Google Scholar]

- Heidegger, Martin. 1978. Being and Time. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Heljakka, Katriina. 2018. Bel far niente? Photography as Productive Play in Creative Cultures of the 21st Century. In Fotografia e culture visuali del XXI secolo. Edited by Enrico Menduni and Lorenzo Marmo. Rome: Romatre Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heljakka, Katriina. 2023. Masked Belles and Beasts: Uncovering Toys as Extensions, Avatars and Activists in Human Identity Play. In Masks and Human Connections. Edited by Luísa Magalhães and Cândido Oliveira Martins. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heljakka, Katriina, and Juulia Räikkönen. 2021a. Puzzling out “Toyrism”: Conceptualizing value co-creation in toy tourism. Tourism Management Perspectives. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heljakka, Katriina, and Juulia Räikkönen. 2021b. Playing it safe: Toyrism (toy tourism) as revenge travel in pandemic times. Paper presented at the 29th Nordic Symposium in Tourism and Hospitality Research Shaping Mobile Futures: Challenges and Possibilities in Precarious Times Akureyri, Iceland/e-Conference, Akureyri, Iceland, September 21–23. [Google Scholar]

- Heljakka, Katriina, and Juulia Räikkönen. 2023. #Instadolls on staycation—Doll dramas narrating popular culture tourism and regional development. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heljakka, Katriina, and Pirita Ihamäki. 2017. Toy Tourism. From Travel Bugs to characters with wanderlust. In Locating Imagination in Popular Culture. Place, Tourism and Belonging. Edited by Nicky Van Es, Stijn Reijnders, Leonieke Bolderman and Abby Waysdorft. London: Routledge, pp. 183–99. [Google Scholar]

- Henricks, Thomas S. 2015. Play as Experience. American Journal of Play 8: 8–49. [Google Scholar]

- Henricks, Thomas S. 2016. Reason and Rationalization. A Theory of Modern Play. American Journal of Play 8: 287–324. [Google Scholar]

- Hesse, Herman. 1969. The Glass Bead Game. Translated by Richard Winston, and Clara Winston. London: Jonathan Cape. First published 1946. [Google Scholar]

- Huizinga, Johan. 2016. Homo Ludens. A Study of the Play-Element in Culture. Kettering: Angelico Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ingold, Tim. 1993. The Tempoarlity of the Landscape. World Archaeology 25: 152–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingold, Tim. 1995. Building, Dwelling, Living: How Animals and People Make Themselves at Home in the World. In Shifting Contexts: Transformations in Anthropological Knowledge. Edited by Marilyn Strathern. London: Routledge, pp. 57–80. [Google Scholar]

- Ingold, Tim. 2011. Being Alive. Essays on Movement, Knowledge and Description. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ingold, Tim. 2012. Introduction. In Imagining Landscapes: Past, Present and Future. Edited by Monica Janowski and Tim Ingold. Farnham: Ashgate, pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov, Stanislav Hristov. 2019. Tourism beyond humans—Robots, pets and Teddy bears. In Tourism and Intercultural Communication and Innovations. Edited by Genka Rafailova and Stoyan Marinov. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, pp. 12–30. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, Michael. 1989. Paths toward a Clearing. Radical Empiricism and Ethnographic Inquiry. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, Michael, ed. 1996. Things as They Are. New Directions in Phenomenological Anthropology. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, Michael. 2005. Existential Anthropology. Events, Exigencies and Effects. Oxford: Berghahn. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, Michael, and Albert Piette, eds. 2015. Anthropology and the Existential Turn. In What Is Existential Anthropology? Oxford: Berghahn, pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- James, William. 1976. Essays in Radical Empiricism. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jarman, Derek. 1991. Modern Nature. Harmondsworth: Vintage. [Google Scholar]

- Kane, Maurice J., and Hazel Tucker. 2004. Adventure tourism: The freedom to play with reality. Tourist Studies 4: 217–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levinovitz, Alan. 2017. Towards a Theory of Toys and Toy-Play. Human Studies 40: 267–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Light, Duncan. 2009. Performing Transylvania: Tourism, fantasy and play in a liminal place. Tourist Studies 9: 240–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCannell, Dean. 1973. Staged Authenticity: Arrangements of Social Space in Tourist Settings. American Journal of Sociology 79: 589–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malaby, Thomas M. 2009. Anthropology and Play: The Contours of Playful Experience. New Literary History 40: 205–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massie, Pascal. 2018. Masks and the Space of Play. Research in Phenomenology 48: 119–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. 1962. Phenomenology of Perception. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, Claudia, and Jacqueline Reid-Walsh. 1995. And I want to Thank you Barbie: Barbie as a Site for Cultural Interrogation. The Review of Education/Pedagogy/Cultural Studies 17: 143–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okely, Judith. 1994. Thinking through Fieldwork. In Analysing Qualitative Data. Edited by Alan Bryman and Robert G. Burgess. London: Routledge, pp. 18–34. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, Catherine. 2018. Being and Dwelling through Tourism. An Anthropological Perspective. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, Shanna. 2014. Toys on the Move: Vicarious Travel, Imagination and the Case of Travelling Toy Mascots. In Travel and Imagination. Edited by Garth Lean, Russell Staiff and Emma Waterton. Farnham: Ashgate, pp. 149–64. [Google Scholar]