Dorsal Practices—Towards a Back-Oriented Being-in-the-World

Abstract

1. Dorsal Practices: Towards a Dorsal Orientation

- -

- Within bodies: What emerges through a shift of attention from frontality, verticality, even visuality, towards an increased awareness of dorsality, diagonality, and listening? Rather than conceiving front/back as a binary relation, how might practising a sense of back-ness enrich a more holistic, proprioceptive, kinaesthetic sense of embodiment as the ground of one’s experience?

- -

- Within the intra-action of body/world: Rather than a mode of withdrawal, of turning one’s back, how might a back-leaning orientation support a more open, receptive ethics of relation? How might the passivity and vulnerability associated with a back-leaning orientation become reinvigorated as an active field of cooperation, a way of being-in-the-world that is radically dynamic, vibrant, and alive?

- -

- Within language and thought: What forms of writing and languaging can be developed in fidelity to the embodied experiences of dorsality? How are the experiences of listening, languaging, even thinking, shaped differently through this tilt of awareness and attention towards the back? What new ‘dorsal practices’ emerge in the intermingling of movement-based ways of feeling–thinking–knowing and language-based artistic research?

Ground. Sensation. Stillness. Formation. Arrive. Fall away. Drifting. Experience. Vibrant. Pressure. Navigate. Awareness, sinking. The mouth, the skin, the eyes—dropping, releasing, surrendering. Dorsal—forming. A dorsal voice—turning, bending, twisting … letting go […] Twisting, leading, letting another thing lead […] The floor is my horizontal plane, my point, my plane of reference. […] There is a sense of the hairs on the back of the neck … an image forms in my mind from a sensation, embryonic trace of forming. Tuning into the back softens the front, softens the front—allows the front to drop back. Expectation drops, time drops, the body drops into another sense of time. Thinking about the back through a kind of undoing—an undoing of uprightness […] All of this activation, relaxing and letting go, and releasing and loosening, and stopping holding and … and do I really know what it is to be upright? Am I even aware of this frontality that my experience is shaped by? […] This awareness of the forward-leaning and future-leaning sense of frontality … and a coming to the ground.

Straightforward—directly forward or right ahead. Of two adjectives—straight and forward. It is interesting—the nearby references. There is this word: tergiversation. Tergiversation—a noun meaning turning from a straightforward action or statement. Shifting, evasive, declining, refusing. From tergiversari—to turn one’s back on, or to evade, from tergum ‘the back’, and versare ‘to spin, turn’. The same origins as conversation, con- and versare, to turn together. Tergiversate—to be evasive, to turn one’s back, to turn one’s back […] To turn or bend one’s back. Turning from a straightforward direction, shifting or declining. Straightforward is straight and forward. Direct, undeviating—not crooked, not bent or curved. Of a person—properly stretched. Direct, unambiguous, unconvoluting or uncompromising. In a straight line—without swerving or deviating.

There being just enough pressure, just enough resistance, to want to try and bring it into formation. The stimulation to try and bring a thought into formation, or a word into formation, can just fall away into a kind of silence or the un- again. There’s this settling, dropping, sinking—you almost go so low that you start to float. It feels like by heavy, heavy, heavy—a lightness comes into the body. This sense of the soft eyes that activate this dorsal listening—letting the thoughts just come rather feeling this pressure to speak. This pressure to speak is to do with a preoccupation with what is coming next, the future, an orientation to what is going to come … there is something about tense. In both senses—being tense and the temporal sense of tense.

A different kind of gaze—almost like the liquid of the eye drops back into its orbit, into the actual socket somehow. We are dropping back into something that is not yet formed. Dropping into the back feels as if there is something much closer to experience. Exploring this relationship between doing and being—it feels as if the back is more a mode of being, and the front a zone of doing. But again, there is a risk that these are binaries that are being perpetuated.

2. Dorsal Practices—Methods of Enquiry

To try and be aware through the back of the body of this experience that we are having in the moment—what does it open? […] Feeling able to rest in the situation, reside in the situation. To lean back. Taking time … there is something about taking time. Like the frontal mode feels a bit urgent or a bit hurried or maybe even a bit uncertain. Transition. Efficiency. Curiosity continuum. Vulnerable. Discipline and curiosity. Forgetting. A kind of dreamy state. Halfway […] Slip into. Back/front. A vertical line. Gravity. Unsettle, unsettle this sense of the binary between the front and the back. What gets lost or what falls away in our capacity if we are not careful, out of habit, or ease, or sometimes inefficiency. Allowing the front and the back to cooperate more … (and) maybe the qualities of thinking connected with the front and the back to cooperate more, so rather than it being this either/or it has more possibility as cooperation. The body has to roll—to roll, it has to be asymmetrical […] Something has to move first—something has to drop first. There’s always a sort of curiosity about what will start the movement.

How do these various modes of experience and of thinking experience cooperate? This movement from the front to the back as a kind of conscious transition. It is very messy and murky … it just won’t crystallise […] Murky back thinking […] I can just collapse, I let go of everything and I fall to the ground. There is a dark spaciousness […] there are more shadows, you catch things in the corner of the eyes. The corner of the eye … shadowy spaces between physical things and imaginary things […] That zone is somehow concealed or hidden or not accessible or unknown in a way. […] It seems counterintuitive that somehow this leaning back into the unknown … enables a kind of relaxation or a resting in experience. […] The sense of the blur—looking through the gap of the eye, slight slant of the eye. How sight is often trying to direct, pinpoint, to name things, whereas this half-blurred vision … almost like the eye’s sight touching the surfaces of things … a different kind of possibility with the eyes […] There are qualities of thinking that have much more of a sense of back-ness.

This pleasure, a pleasure in moving backwards, a pleasure in being and moving, a very elemental pleasure … the pleasure of cooperation of the body and the ground and the environment. In the frontal mode, I seem to skate over the surface of the environment to get somewhere. This pleasure of participating […] Allowing—allowing certain movements to happen, not resisting, or maybe not even thinking […] Soft back and soft belly […] Breath and softness create a sense of spaciousness, if the body lets that happen. Something about the dropping back, not necessarily back, but letting go […] My eyes, softness, closing of the eyes … this blurred vision. This blur … the blurring, the dissolving of those differentiated categories. But as soon as you come to language that experience becomes squeezed into binary relationships. To try and take attention to the sides of language, to the grey areas of language. Not the up and the down, but to really activate this side space that is neither up nor down, nor front nor back … Falling. Behindness. Backness. Different kind of register. Forgetting. Allowing. Gravity.

Being willing. Pelvis, limbs. Counterintuitive, vulnerability. Clockwise, anti-clockwise […] The openness of the body—taking the attention to the back opens the front of the body in a way that feels quite vulnerable or exposed. […] Transformative possibility. Pattern of being, micro frequencies. Bracketed, less and less—tiny vibrations. Pressures of a certain way. Rhythms and pulses, fluid and loose. Sentience—a being that is alive […] A real sense of being alive, being alive that’s free of all those habits of life that accumulate over time […] In these practices, very alive in the sensations of exploration and unhindered by habits of identity […] We fall into talking through thinking through the process […] To follow what’s happening, and speak it as it happens … There are moments where the thinking and the speaking and the reflecting and the circling around are folding back, in and out.

3. Body-Based Somatic-Movement Practices

There are moments where … there is a glimpse … of this kind of pure being, joyful. Dwelling, lingering … swaying. […] This sense of having something in mind, lightly. Having the notion of dorsal practices lightly in mind, held in the background but not looked at too directly … so it informs but in an indirect way. Dropping into the present—it doesn’t need to resist, doesn’t need to have a sense of the retrograde, or pulling back […] Allowing in of the dorsal, let it seep in gently. Perhaps there are these other modes, allowing it to come in gently, because then it really does have this possibility to evolve, or change, yes, change things.

Wayfinding, finding the way. Having to go around the back of things or meander a little to find a way in or find a way back. These different systems of locating, navigating, orientating […] Orienting backwards, towards the back. This sense of facing to the back, or back-to-back. Way finding, to find the way. And finding a way, finding a way, rather than looking for the way. There are two different kinds of listening: through the ear, skin or nervous system, or just the sensitivity to everything that is vibrating. This idea of sensing vibrations of bodies, objects or anything really. Micro-frequencies … we are kind of sensing machines—you can pick up static, air circulating, tiny vibrations of many different things. This idea of lingering in it and being with the movement of the world in a different way. A sense of being among, being one of those vibrating things. There is another kind of located-ness through vibration and being present—more linked to listening. There are other kinds of listening or ways of understanding how one is orientating. How can it become less and less?

The path is not drawn like a straight line—it meanders and takes tangents. Straightforward-ness—what does this mean? What does it mean to be straightforward? And why is that a value? Such a strange value, this straightforward—so one-dimensional in a way. And how is a dorsal way of practising not straightforward? To activate these diagonal relationships, and the criss-crossings and the meanderings. The turn is … not straightforward […] It is constantly pulling you off the straight, the upright—pulling you a little this way and a little that way, swaying this way and that way, even as you are progressing forwards. Sway and to be swayed […] There is the sense of a diagonal orientation creating space where there appears to be none—this cut of the diagonal, the diagonal as a desire line. All these diagonal paths […] refusing to be one or the other but being both […] That is why we have to turn—to keep turning and to keep moving the spine to turn—to activate these diagonal relationships, and the criss-crossings and the meanderings […] Fluid, subtle, murky, dorsal.

4. Language-Based Practices

Delight. Cooperation. Anatomically. Light tread. Neural patterning. Super blurry. Unthinking and unthought … Releasing the seeing. Unthinking movements and the unthought … Releasing, releasing. Low orientation. Releasing, releasing the eyes. Releasing, releasing. Easiness in the eyes. Letting the eyes be released of orientation in a different way […] The delight, a kind of release to the front of the body. We are designed for walking forwards and yet operating in … this reversal brings such ease and relief. The re- of reflection and the testing […] Re-turn—as in go back to or do it again … to turn it over, to re-test it, or do it again, and then to notice anew. […] The turning over and over, the testing having a more circular or folding quality […] Re-establishing neurological pathways that might have got lost or forgotten through inaction or through not being used […] This dwelling with what’s been or where one’s been—not rushing towards something in the future, but just sort of letting in […] Regarding—having a regarding quality to what was being observed. This sense of spaciousness, this expansiveness—into the body, into the lungs, into the chest, into the shoulders … opening the arms … opening the chest. There’s a softening allowed—to fall into the back.

Score for the Practice of Conversation

- -

- Take a moment to tune into the chosen object or focus of exploration—this could involve a period of recollection, or looking back at notes, sketches, wordings that relate to the object/focus of exploration, or by noting/drawing/diagramming.

- -

- Connect and try to stay connected with your direct experience.

- -

- Feel free to speak before knowing what it is that you want to say—thinking through speaking.

- -

- Feel free to speak in single words, partial phrases, half sentences, and thought fragments.

- -

- Allow for vulnerability and embarrassment—for wrestling with, stumbling, and falling over one’s words.

- -

- Consider different speeds and rhythms. Allow for silence.

- -

- Approach listening to the other as a ‘dorsal practice’.

A more radial sense of space—my ears are scanning around me; I am listening to the shifting sounds. I am bringing attention to the immersive quality of being in the space—sounds close and far, and different volumes, frequencies … picking up or listening in a different way as well. Temperature and air are combining with different senses of listening—listening through touch and through the skin as well as through the ears. Almost like a choreographic score—the different combinations of turns and half-turns as a way of disorientating. How we orientate in relationship to a sense of direction […] So, there’s a kind of double focus […] Testing in a way, or exploring, testing again. What do I notice? What am I aware of? Is this my experience? Is this my experience? […] Before things become fully automatic there’s this interesting wrestling where it’s not quite familiar […] What does that awkwardness do?

5. Experimental Reading Practices

Score(s) for the Practice of Reading

- Reading (Noticing Attraction)—Each person has the transcript in hand, allowing one’s gaze to be soft, to glide or roam the pages. When a word draws your attention, speak it out loud. Allow for overlaps and also silences.

- Reading (Distillation)—Take time to tune into the transcript, noticing phrases and words that strike you or that resonate. As the practice begins, when the time feels right, read out loud single words, phrases, or a cluster of sentences. Once familiar with the practice, allow the act of distillation to happen spontaneously in the moment, speaking words and phrases live as they come to your attention. Attend to the emerging sense-making between the lines of two voices intermingling—letting one’s attention shift between listening and speaking.

The evolution of movement has this push towards uprightness and faciality and frontality, and yet moving to the back—whether physiologically or psychologically—brings such release and joy […] This sense of abandon, the joy of abandon. How can it not be part of the fabric of being human and having a human body? These brief interludes in a life which otherwise feels very frontally oriented […] The fatigue of frontality, the tiredness of it and these fluid, pleasurable, joyful pockets of exercising and of testing something out. And the sorrow that this is how it seems to be […] It doesn’t need to be a brief exercise—why could it not be more, why not live life more dorsally?

There is this temporal elasticity, but very present at the same time […] This disturbance of linear time in a way. To do with releasing, release of, permission to lose control. There is something to do with control, expectation, responsibility, the sense of ourselves or how we think to present ourselves in the world, to ourselves and to others. And that is allowed to shift—it is a psychological and emotional shift as well, a twist, and a turn and a drop […] Time released and opening into this atemporal timelessness, from this small shift of orientation. Such a transformative effect on how time and space and body and surroundings are experienced—very radical in a way […] Releasing (the eyes) from their role of orientation or searching or protection or route-finding […], the eyes being able to inhabit a different mode of being in a way. Just allowing the eyes to be. Just letting in the sky and the clouds, and yes […] there is this quality of expansion.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Ahmed highlights how the etymology of “direction” (from direct) is inextricably related to the notion of “‘being straight’ or getting ‘straight to the point’”, (Ahmed 2006, p. 16). |

| 2 | Whilst we do not conceive a dorsal orientation as synonymous with slowness or deceleration as such, we do recognise resonance with certain discourses on slowness and rest as modes of resistance. For example, philosopher Isabelle Stengers argues that “Slowing down means becoming capable of learning again, becoming acquainted with things again, reweaving the bounds of interdependency. It means thinking and imagining, and in the process creating relationships with others that are not those of capture”, in (Stengers 2018, pp. 82–83). Maggie Berg and Barbara K. Seeber describe and confront the hurried, instrumental, and efficiency-driven emphasis on productivity, competition, and continuous improvement experienced within the contemporary corporate university in (Berg and Seeber 2016). In their edited compendium, Felicity Callard, Kimberley Staines, and James Wilkes address both the presence and absence of rest within diverse contexts, including specific practices of both rest and restlessness. See (Callard et al. 2016). More broadly, we recognise potential affinities between a dorsal orientation and wider de-growth philosophies and critiques of progression-focused ideologies. See also (Berardi 2011). |

| 3 | We wonder if the dorsal orientation might better be understood as a mode of disorientation. For Ahmed, “Disorientation could be described here as the ‘becoming oblique’ of the world, a becoming that is at once interior and exterior, as that which is given, or as that which gives what is given its new angle”, (Ahmed 2006, p. 162). |

| 4 | Language-based artistic research is a new term for an emergent genre or field of artistic research which Emma Cocker, Cordula Daus, and Lena Séraphin coined for describing approaches to artistic research that work-with language as their material. Cocker, Daus, Séraphin, and Alexander Damianisch are co-founders of the Society for Artistic Research: Special Interest Group for Language-based Artistic Research, which was established in 2019 within the frame of the Research Pavilion #3, Venice. See https://www.researchcatalogue.net/view/835089/835129 (accessed on 27 March 2024) |

| 5 | Whilst influenced by the ‘deep listening’ practices of sound composer Pauline Oliveros (Oliveros 2005), the practice of ‘deep listening’ within Dorsal Practices is also informed by a method called Awareness Centred Deep Listening Training (ACDLT®), a programme founded in 2003 by Rosamund Oliver to develop meaningful and beneficial communication between people and in communities. Cocker is trained in Awareness Centred Deep Listening. We also find resonance in artist and sound theorist Brandon LaBelle’s ongoing enquiry around listening as an embodied research practice. LaBelle states, “If listening takes us somewhere it is into the ebbing and flowing of life, the deep pulse and resonant reach of becoming-with; it is towards intimacies and a world of touch”, in The Listening Biennial Reader, (LaBelle 2022, p. 7). |

| 6 | Di Paolo, Cuffari, and De Jaegher note how “Social interactions are vulnerable. And so are their participants. The latter are vulnerable insofar as they are embodied agents and […] their autonomy, both organic and sensorimotor, is an ongoing achievement under precarious conditions”, (Di Paolo et al. 2018, p. 71). They state that, “Precariousness and vulnerability are not ‘unfortunate’ empirical aspects of how autonomous systems (individuals and interactive patterns) are realized in the real world. They are constitutive of this autonomy and without them the concept of autonomy would be empty”, p. 72. |

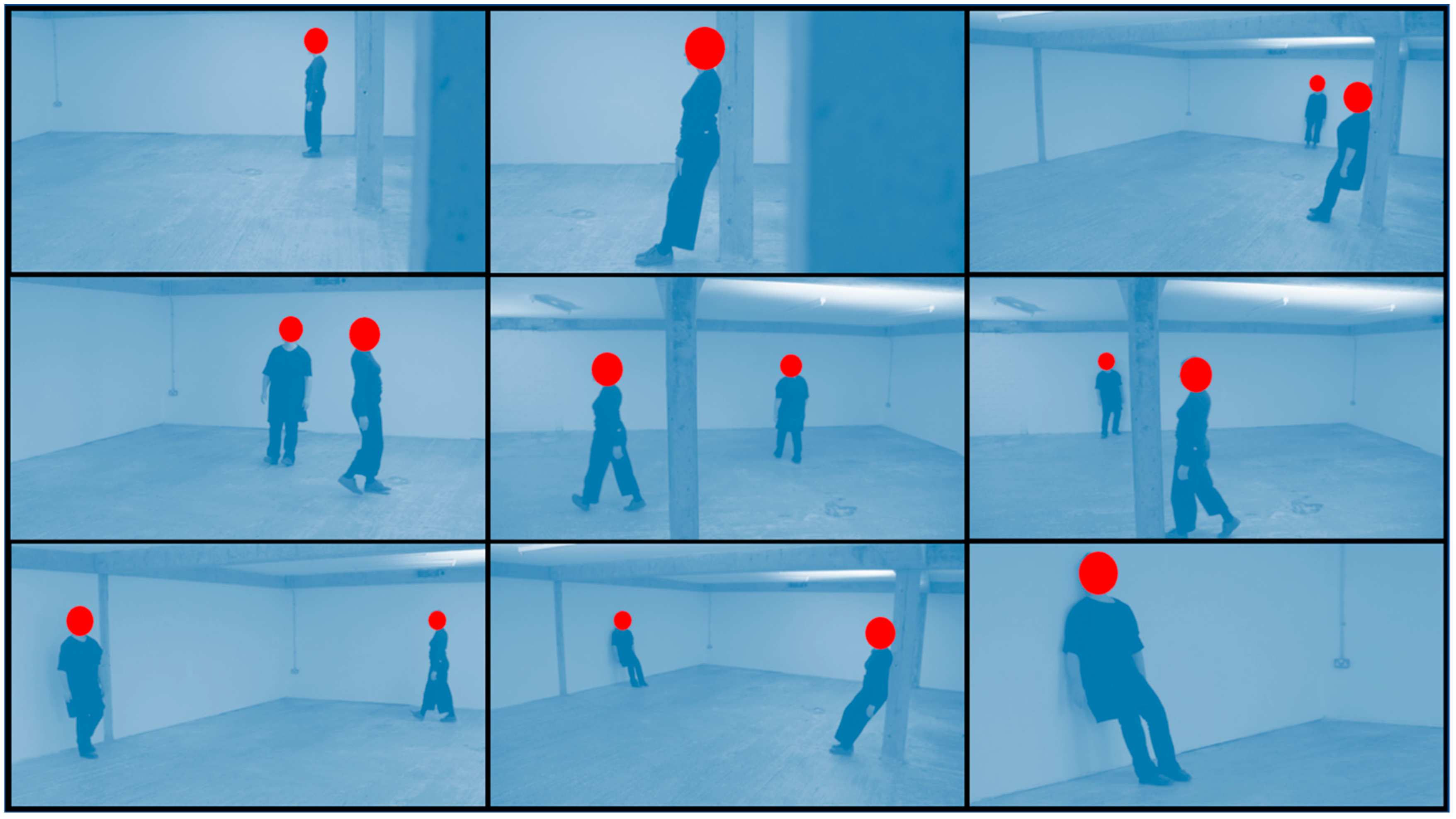

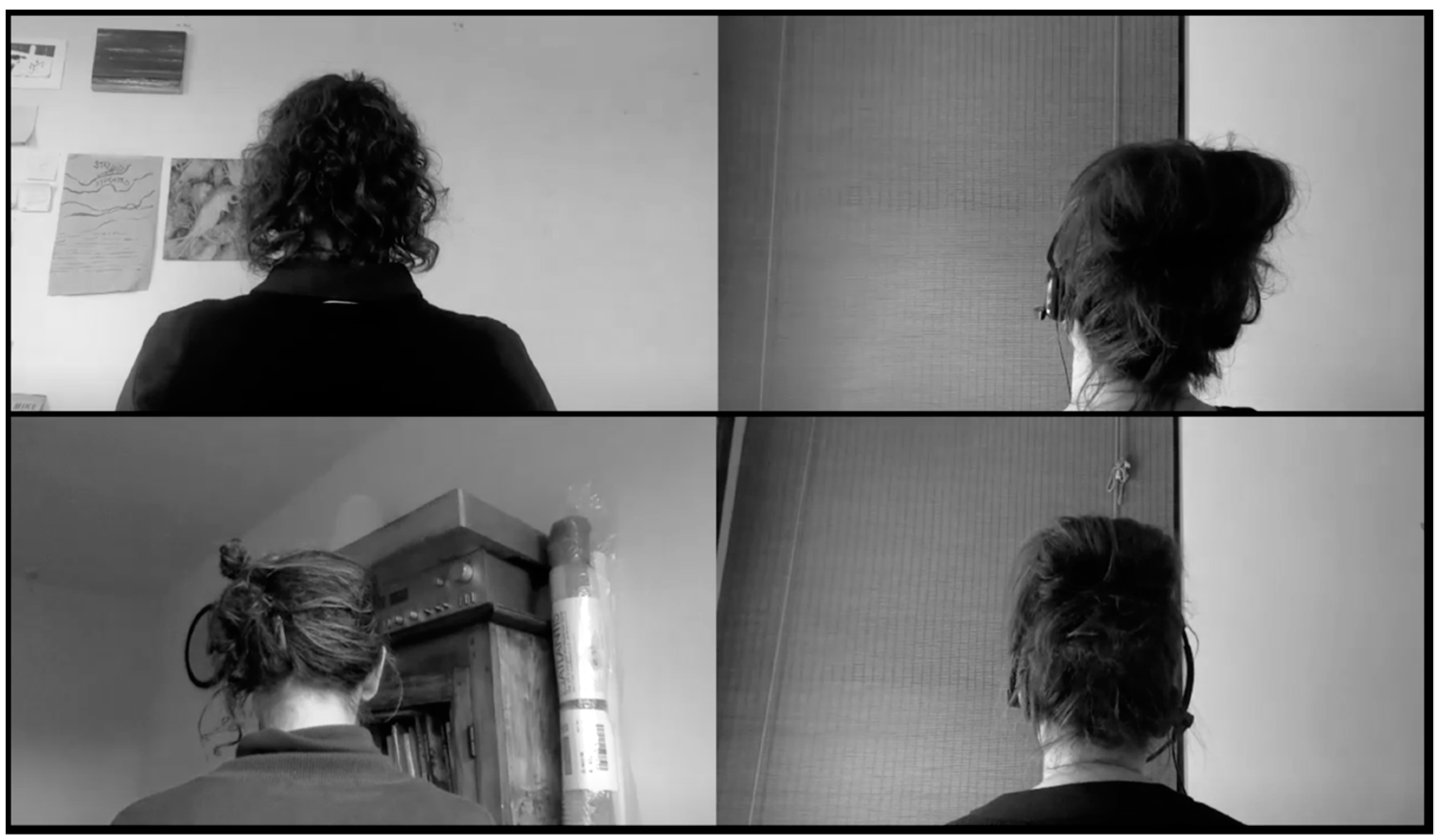

| 7 | See (Brown 2022, pp. 145–63) and https://katrinabrown.net/project/tilt-rhythm-back-dances-drawings (accessed on 27 March 2024). |

| 8 | With-nessing is a neologism of witnessing and being-with. The notion of ‘with-nessing’ as an artistic research approach was developed by (Cocker et al. 2017, pp. 164–66). |

| 9 | For example, see (Feldenkrais 1950; Hanna 2004). We recognise resonance with the score-based practices of choreographer Steve Paxton [e.g., Small Dance], dance-maker and improviser Lisa Nelson [e.g., Tuning Scores], and sound composer Pauline Oliveros [e.g., Deep Listening]. |

| 10 | We are grateful to the reviewers for drawing our attention to Annika Olofsdotter Bergström’s and Juliana Restrepo-Giraldo’s article (Olofsdotter Bergström and Restrepo-Giraldo 2023). |

| 11 | See (Rouhiainen et al. 2024). Vida L. Midgelow explores the “interplay between writing and improvisational dancing to describe a methodology for an embodied, sensual and experiential mode of writing/dancing in which the boundaries between these two disciplines are blurred”, in (Midgelow 2012, pp. 3–17). Jasmine B. Ulmer asks: “(W)hat if writing danced? What if words embodied movement? How might writing be inscribed as a material, kinaesthetic, visual process?”, in (Ulmer 2015, pp. 33–50, 34). More broadly, cultural theorist and political philosopher Erin Manning’s wider oeuvre might be conceived to operate at the interstices of movement, thought and language. See for example, (Manning and Massumi 2014). |

| 12 | The ‘turn taking’ without interruption is based on Nancy Kline’s ‘time to think’ model. See (Kline 1999). |

| 13 | Phenomenologist Max van Manen refers to the notion of ‘Vocative Writing’, where “the term voke derives from vocare: to call, and from the etymology of voice, sound, language, and tone; it also means to address, to bring to speech.” See (van Manen 2014, p. 240), especially the chapter ‘Philological Methods: The Vocative’, pp. 240–96. Van Manen outlines the vocative dimension of phenomenological writing by methods of the revocative (lived through-ness: bringing experience vividly into presence through anecdote and imagery); evocative (nearness: an in-touch-ness activated through poetic devices including alliteration and repetition); invocative (intensification: a calling forth by incantation); and convocative (pathic: expressing an emotive, non-cognitive sensibility). |

| 14 | Citton asks, “What can we do collectively about our individual attention, and how can we contribute individually to a redistribution of our collective attention?” (Citton 2017, p. 10). |

| 15 | For example, we have presented our enquiry through a performance reading and a workshop within the frame of the symposium, Sentient Performativities: Thinking Alongside the Human, (Dartington, June 2022) and as a performance reading at the Society of Artistic Research conference, Too Early/Too Late, in Trondheim, Norway, 9–21 April 2023. |

| 16 | Here, we recognise the need to question what might be conceived as ‘implicit knowledge’ or even ‘common sense’ drawing on the work of philosopher Alexis Shotwell, for whom ‘knowing otherwise’ involves an attempt to explore the possibilities for new kinds of ‘livability’, a ‘new common sense’ [new sensus communis] based upon relationality, interconnection, and freedom dreaming, arguing how [only] “this sort of socially situated, embodied knowledge can function as impetus, sustenance, and imaginative motor for individual and collective change,” in (Shotwell 2011, p. 70). See also (Shotwell 2014, pp. 315–24). |

References

- Ahmed, Sara. 2006. Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, Objects, Others. Durham and London: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Berardi, Franco ‘Bifo’. 2011. After the Future. Edinburgh, Oakland and Baltimore: AK Press. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, Maggie, and Barbara K. Seeber. 2016. The Slow Professor: Challenging the Culture of Speed in the Academy. Toronto, Buffalo and London: University of Toronto Press. [Google Scholar]

- Borgdorff, Henk. 2011. The Production of Knowledge in Artistic Research. In The Routledge Companion to Research in the Arts. Edited by Michael Biggs and Henrik Karlsson. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 44–63. [Google Scholar]

- Boulous Walker, Michelle. 2017. Slow Philosophy: Reading Against the Institution. Bloomsbury Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Katrina. 2022. circling, tumbling, dancing around: Back pieces. Choreographic Practices 13: 145–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callard, Felicity, Kimberley Staines, and James Wilkes, eds. 2016. The Restless Compendium: Interdisciplinary Investigations of Rest and its Opposites. Durham: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Carlisle, Clare. 2014. On Habit. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Cavarero, Adriana. 2016. Inclinations: A Critique of Rectitude. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Citton, Yves. 2017. The Ecology of Attention. Translated by Barnaby Norman. Cambridge: Polity. [Google Scholar]

- Cocker, Emma, Cordula Daus, and Lena Séraphin. 2020. Reading on Reading: Ecologies of Reading. Ruukku. Ecologies of Practice. Available online: https://www.researchcatalogue.net/view/618624/618625 (accessed on 27 March 2024).

- Cocker, Emma, Nikolaus Gansterer, and Mariella Greil. 2017. Choreo-Graphic Figures: Deviations from the Line. Berlin: de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Cocker, Emma. 2022. Conversation as Material. Phenomenology & Practice 17: 201–31. [Google Scholar]

- Di Paolo, Ezequiel A., Elena Clare Cuffari, and Hanne De Jaegher. 2018. Linguistic Bodies: The Continuity between Life and Language. Cambridge, Massachusetts and London: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Feldenkrais, Moshe. 1950. Body and Mature Behaviour: A Study of Anxiety, Sex, Gravitation and Learning. New York: International Universities Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hanna, Thomas. 2004. Somatics: Reawakening the Mind's Control of Movement, Flexibility, and Health. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press. [Google Scholar]

- Haseman, Brad. 2006. A Manifesto for Performative Research. Media International Australia 118: 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, Nancy. 1999. Time to Think: Listening to Ignite the Human Mind. London: Ward Lock. [Google Scholar]

- LaBelle, Brandon, ed. 2022. The L:sten:ng Biennial Reader. Berlin: Errant Bodies Press. [Google Scholar]

- Manning, Erin, and Brian Massumi. 2014. Thought in the Act: Passages in the Ecology of Experience. Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Michelkevičius, Vytautus. 2018. Mapping Artistic Research: Towards Diagrammatic Knowing. Vilnius: Vilnius Academy of the Arts Press. [Google Scholar]

- Midgelow, Vida L. 2012. Sensualities: Experiencing/Dancing/Writing. New Writing 10: 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveros, Pauline. 2005. Deep Listening: A Composers’ Sound Practice. New York and Lincoln: Deep Listening Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Olofsdotter Bergström, Annika, and Juliana Restrepo-Giraldo. 2023. Walking Backwards as a Radical Practice for Design. In Nordes 2023: This Space Intentionally Left Blank, Norrköping, Sweden, June 12–14. Edited by S. Holmlid, V. Rodrigues, C. Westin, P. G. Krogh, M. Mäkelä, D. Svanaes and Å. Wikberg-Nilsson. London: Design Research Society. [Google Scholar]

- Rouhiainen, Leena, Kirsi Heimonen, Rebecca Hilton, and Chrysa Parkinson, eds. 2024. Writing Choreography: Textualities of and beyond Dance. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Shotwell, Alexis. 2011. Knowing Otherwise: Race Gender and Implicit Understanding. Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania University State Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shotwell, Alexis. 2014. Implicit Knowledge: How it is Understood and Used in Feminist Theory. Philosophy Compass 9: 315–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stengers, Isabelle. 2018. Another Science is Possible: A Manifesto for Slow Science. Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Thanem, Torkild, and David Knights, eds. 2019. Embodied Research Methods. Los Angeles and London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Ulmer, Jasmine B. 2015. Embodied Writing: Choreographic Composition as Methodology. Research in Dance Education 16: 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Manen, Max. 2014. Phenomenology of Practice: Meaning-Giving Methods in Phenomenological Research and Writing. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Wills, David. 2008. Dorsality: Thinking Back Through Technology and Politics. Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Brown, K.; Cocker, E. Dorsal Practices—Towards a Back-Oriented Being-in-the-World. Humanities 2024, 13, 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/h13020063

Brown K, Cocker E. Dorsal Practices—Towards a Back-Oriented Being-in-the-World. Humanities. 2024; 13(2):63. https://doi.org/10.3390/h13020063

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrown, Katrina, and Emma Cocker. 2024. "Dorsal Practices—Towards a Back-Oriented Being-in-the-World" Humanities 13, no. 2: 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/h13020063

APA StyleBrown, K., & Cocker, E. (2024). Dorsal Practices—Towards a Back-Oriented Being-in-the-World. Humanities, 13(2), 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/h13020063