1. Introduction

This article contributes to my ongoing interest in an anthropologically derived philosophy of what it means to be human by focusing on virtually modified tourism worlds. My thinking in relation to the virtual is framed around the concept of dwelling as a way of being-in-the-world (

Heidegger 1962,

[1971] 2001a;

Ingold 2011a,

[2000] 2011b), having already found this a particularly useful approach for uncovering what the activity of tourism might reveal about human experience (see

Palmer 2018). Here, I focus on the encounter between self and world, of being a self in the world. My use of self is not that of a psychologically dissected self but the experience of being a socially active being in the world—‘no human being comes to a knowledge of himself or herself except through others’ (

Jackson 1995, p. 118). In this instance, the social encounter occurs through technologically modified experiences of tourism, virtually created experiences that expand and overlay the physical world with the digital.

Experience is increasingly mediated through forms of extended reality (XR) technologies such as virtual reality (VR), augmented reality (AR) and augmented virtuality (AV) that are themselves not always clearly and unambiguously defined. A useful starting point for understanding the human–digital interface is

Milgram and Kishino’s (

1994) highly influential ‘virtuality continuum’; here, the real and the virtual exist at opposite ends of a pole, along which AR and AV are located within an area they refer to as mixed reality (MR). The continuum draws attention to the extent of immersion that can be delivered by AR, AV, and VR as individuals interact with real and/or fictional objects, text, sound, light, colour and so on. The seeming simplicity of Milgram and Kishino’s continuum belies the fact that, over the years, the terms and acronyms used to describe human–digital interactions, what

Cook et al. (

2017) refer to as ‘digital reality’ technologies, often confuse rather than clarify the type of mediated experience provided (see

Speicher et al. 2019;

Rauschnabel et al. 2022). Furthermore, mediated experiences (AR, AV, and VR) are often delivered in ways where the technologies appear to be interchangeable. For example, VR headsets, AR/MR apps such as Pokémon Go or Microsoft’s HoloLens headset and what is referred to as the disruptive technology of the metaverse. A digital combination of the internet, VR and AR/MR provide 3D immersive experiences in both virtual and physical environments (

Catricalà and Eugeni 2020;

Rauschnabel et al. 2022;

Buhalis et al. 2023).

The term extended reality (XR) can be equally ambiguous. Some scholars define it as a generic umbrella term for all computer-mediated reality technologies (

Gong et al. 2021;

Silva and Teixeira 2022). While others, such as

Rauschnabel et al. (

2022), argue that defining XR as extended reality is misleading because some technologies, such as VR replace rather than extend reality. However, to my mind, XR is an overarching expression of all real-to-virtual technologies because reality is never replaced. Even virtual immersion through, for example, the Sony PlayStation VR2 headset does not physically remove an individual from the life sustaining environment of the ‘real’ physical world. So, despite the ever-changing and frequently ambiguous technological terrain, all forms of reality-mediating technology are designed to augment or replicate the physical tangible world by delivering a spectrum of experiences ranging from enhancement of this world to total immersion in and interaction with a digitally created experience of human–world relationships.

In terms of tourism, information and communication technologies have existed to varying levels of sophistication for a very long time. However, the decades since the 1980s witnessed the experiential growth in and use of reality-shifting technology associated with XR (

Frew 2000;

Loureiro et al. 2020;

Trunfio et al. 2022). Immersive 360 tours alter what it means to experience people and place. For example, Google provides numerous virtual tours visiting locations and attractions ranging from national parks, museums and galleries to the seven wonders of the world without the need to leave home (

Snow 2020). Virtual encounters create experiences that challenge existing notions of what being a tourist means and during the 2020 pandemic, several national tourist boards created virtual campaigns to keep travellers engaged and thereby encourage future trips (

Fanthorpe 2020). Environmental concerns have resulted in initiatives such as

heygo, a free travel specific live streaming platform that enables travellers to stay connected and to experience destinations and cultures again, without the need to leave the comforts of home behind.

The online travel agency, Virtual City Tours, offers live tours accompanied by professional tour guides presenting ‘history and stories in an enjoyable and lively way using video conferencing technology like Zoom. The tours are broadcast live from the street or moderated as a live presentation in real time on the screen’ (

Virtual City Tours n.d.). The online virtual game community, Second Life allows individuals to create avatars through which they can travel, buy consumer goods, visit virtual museums and book holidays through virtual travel agencies. A destination guide provides links to virtually created ‘vacation spots’ such as French Riviera Island, Bear Lake Mountain Resort, the Empire Hotel and the Niabi Resort (

Second Life n.d.).

Within the context of the above, I interrogate what the implications of a virtually derived experience of tourism might be for how we understand what experience means and by extension the experience of being human-in-the-world. The hyphenation highlights the inseparability of human and world in the sense that who I am, who we are, is constituted by the doing of experience. Experience that comes from engagement with and immersion in the everyday components of a particular world, ‘the compound expression ‘Being-in-the-world’ indicates in the very way we have coined it, that it stands for a

unitary phenomenon’ (

Heidegger 1962, p. 78, original emphasis). The unitary phenomenon, virtual-tourism-world, is experience as virtual dwelling.

2. Framing Lived Experience

At this point, it is important to say something about my use of the word reality and the word experience. I do not intend to discuss the metaphysics of either word as abstract concepts, and others are more qualified than I to do so (see for, e.g.,

Dewey 1958;

Janack 2010;

Correia and Schneider 2012); however, some parameters are necessary. References to there being a real world or to reality should not be taken to suggest that there is an unreal or false world in opposition. Indeed, questions concerning a real world versus an unreal, simulated world are not always helpful. All experiences are ‘real’ in the sense that they occur as life is lived, as illustrated by the plethora of ethnographic evidence as to the embeddedness of belief systems where animals and inanimate objects are considered persons; wisdom is to be found in water, rocks and mountains and spirits are embedded in the architectural fabric of an airport (

Basso 1996;

Willerslev 2007;

Ferguson 2014). Even virtual, digital simulations, whether intended to replicate, overlay or enhance the tangible concrete world of daily life are real. In the same way as going to the cinema, reading a book or using a computer are experiences of reality. Digital/VR games such as

Boneworks or

Warcraft maybe simulations but individuals do not move out of the physical world into an alternate world. There is no equivalent of what is portrayed in the

Matrix film franchise. XR technologies are real life because they are activities embedded in the doing of life:

To ask oneself whether the world is real is to fail to understand what one is asking, since the world is not a sum of things which might always be called into question, but the inexhaustible reservoir from which things are drawn.

Moving onto experience, despite its incalculable appearance in everyday life, experience in this instance is not rationally mechanistic behaviour or a source of entertainment. It is not something that can be provided, used to attract customers or to differentiate products and services. Experience is not an economically powerful commodity as

Pine and Gilmore (

1999) argued in their seminal book

The Experience Economy, where companies grow and survive through the provision of rich, memorable and compelling experiences. All these aspects are clearly what experience ‘means’ in the sense of a general understanding of the word together with the associated physical and emotional responses to how an experience is received. Nevertheless, there is a richer meaning to the word experience revealed by the interweaving threads of anthropology and philosophy illustrated by the existential anthropologist

Michael Jackson (

2017, p. ix, original emphasis) ‘it is one thing to

be alive; it is quite another thing to

feel alive and to

think that life is worth living’. Being, feeling and thinking are the

doing of life collectively expressed as experience and this is the sense in which I use the word experience. Although more precisely, we should talk of experiences since the nature of human experience is neither singular nor universal.

The form of experience I discuss is ‘human experiencing’, a co-constituted expression of person and world (

Pollio et al. 1997, p. 6). This is not an experience of experiences per se but rather experience that is with, through and in relation to the embeddedness of daily life. Experience as an expression of being human, part of ‘the ongoing process of

being alive in the world’ (

Ingold [2000] 2011b, p. 99, original emphasis), a phenomenological rather than psychological manifestation of the lived experience of being a being-in-the-world (

Bruner 1986;

Csordas 1994;

Hastrup 1995;

Desjarlais and Throop 2011). It is through lived experience that individuals locate, negotiate, challenge, protect and defend what makes me who I am, what makes us who we are in relation to the lifeworld of both human and nonhuman others.

The

Husserl (

[1936] 1970) concept of lifeworld denotes a world that is familiar, that is

lived in and experienced on a daily basis. In this sense, experience is an active rather than a passive activity. This is important because virtual technologies actively engage the physical and the tangible world with a simulated world designed to appear and to ‘feel’ tangible. The implications of this engagement for understanding experience as an expression of being human are of particular interest here.

In bringing together experience and lifeworld, I am highlighting the relationship between philosophy, phenomenology and anthropology, in particular the work of the anthropologists Michael Jackson and Tim Ingold and philosophers such as Martin Heidegger and Maurice Merleau-Ponty. From within this contextual framing, my thinking is influenced by what can broadly be defined as the anthropology of experience and that of digital anthropology (

Turner and Bruner 1986;

Boellstorff 2008;

Horst and Miller [2012] 2020;

Geismar and Knox 2021).

In general terms, phenomenology is the philosophical tradition concerned with what

Merleau-Ponty (

[1945] 2002) describes as essences, the conditions or circumstances through which lived experience unfolds. Circumstances are what shape and reshape the experience of being human in any given context; in effect, what Tim Ingold refers to as the experience of being alive. In this sense, my phenomenological interrogation of experience is rooted in the flesh and blood of

lived experience as revealed through the social context of tourism, rather than in narratives of abstract philosophising. Meaning, in the sense of the meaning of experience, ‘emerges not from isolated contemplation of the world but from active engagement in it’ (

Jackson 2007, p. xi). This is important because, as noted above, experience is an active, lived engagement with human and nonhuman worlds—an engagement that is primarily an embodied experience of a particular world as

habitus (

Bourdieu 1977;

Mauss 1979), experience that is filtered and (re)shaped by and through the culturally conditioned ways of behaving and thinking specific to a society. And, as I have argued elsewhere, the tourist habitus conditions individuals how to think, feel and behave like a tourist; in effect, to ‘know’ what it means to be a tourist, to understand what it is to ‘‘experience’ the ‘tourism experience’’ (

Andrews 2009, p. 18)—an understanding reinforced by the reactions of others, as tourists and as members of the resident population (

Palmer 2018).

As such, experience is an ever-expanding engagement process between persons, world and the spaces and places in which lives are lived, where world encompasses all that is encountered, sensed or imagined; for example, the natural world, plant and animal ecologies, technology, architecture, machines, life, death, relationships, work, play, and faith. The spaces, places and contexts of this encountering include those in which tourists and tourism converge; and, by focusing on tourism, I acknowledge the work of other scholars questioning the phenomenology of a lived tourism experience (

Andrews 2009;

Pernecky and Jamal 2010;

Ness 2020).

3. Virtual Dwelling

Interrogating the implications of what it means to ‘experience’ virtual tourism is inherently an anthropological endeavour given the discipline’s overarching aim to uncover what being human looks and feels like across and within different social and cultural contexts. Tourism, and its conjoined twin travel, are significant experiential human activities deeply embedded in the social economics of societies and cultures. Although tourism is not an activity open to everyone and not all cultures conceive of tourism and travel in the same way, within most societies, travelling, going on holiday, visiting museums and attractions are taken-for-granted activities capable of influencing the experience of being human—through, for example, work and leisure opportunities, travel as faith-based pilgrimage or the provision of what are frequently referred to as memorable experiences (

Aziz 2001;

Tung and Ritchie 2011;

Hosany et al. 2022).

The notion of experience as the human expression of an active, lived engagement with and through daily life has much in common with Heidegger’s concept of dwelling in the sense that dwelling is what experience looks and feels like. For

Heidegger (

1962,

[1971] 2001a), dwelling-in-the-world defines and describes a holistic relationship between person and world, a relationship that comes about through lived engagement with familiar everydayness. This is an engagement on the basis of encounters with things and activities that matter—in this instance, activities such as virtually modified experiences of tourism. This living with the components of everyday life is described by

Heidegger (

1962, p. 80) as ‘a sense of being absorbed in the world’ and this is a useful way to think about the relational experiencing that occurs when persons engage with, move through, dwell in a virtual tourism world.

Drawing from Heidegger,

Ingold (

1993,

[2000] 2011b) referred to this lived engagement as a dwelling perspective arguing that people make themselves at home in the world by engaging with, by dwelling in the surrounding landscape. However, landscape for

Ingold (

1993) does not refer to an environmental given such as land, nature or space, but rather landscape as environing world. The landscape is as it is understood and experienced by those who singly and together move along with it physically and through the imagination ‘within the currents of their involved activity, in the relational contexts of their practical engagement with their surroundings’ (

Ingold 2011a, p. 10). As with Heidegger,

Ingold (

2011a) describes engagement as akin to being absorbed in an activity. This opens up questions as what experience means if we are not just immersed in a virtual activity but actually absorbed by and within a virtual-tourism-world.

This begs the question as to what we mean by world in relation to the virtual and how does it mesh with, overlay the tangible world of tourism and by extension the nature of experience. Drawing from the German biologist

Jakob von Uexküll’s (

[1934] 1992, p. 319, original emphasis) conceptualisation of

Umwelt as ‘the

phenomenal world or the

self-world of the animal’, Ingold and Heidegger describe world in terms of environing or surrounding world. This is usefully explained as ‘the fundamental understanding within which individual things, people, history, texts, buildings, projects cohere together within a shared horizon of significances, purposes and connotations’ (

Clark 2002, p. 16). Commercial (and home) kitchens gather together a kitchen

Umwelt as environing world from the organisation of kitchen space and the location and use of specialised cooking equipment facilitating meaningful social relationships between chefs, waiting staff and customers (

Palmer et al. 2010).

Likewise, a meaningful tourism

Umwelt gathers together a world out of the places, people, activities and things that comprise what tourism is and how it works. As the concept of

Umwelt has been extended to immersive, interactive virtual technology (

Aguilera 2013;

Harris 2022;

Kozicki 2023), then a virtual tourism

Umwelt is an example of what

Kozicki (

2023, p. 83, original emphasis) refers to as an ‘umwelt within an umwelt… viewed as the

immersed umwelt’. The virtual-tourism-world is not an alternative to the physical world but one that merges and overlays the physical with simulated images of the physical. This illustrates the inseparability of the virtual from person and world since world as

Umwelt is not a specific place but an entanglement of social relations including those between humans and technology. As

Heidegger (

1993, p. 318) argued in his essay

The Question Concerning Technology, ‘technology is therefore no mere means. Technology is a way of revealing’. Technology’s significance does not lie in its instrumentality, its essence is not technological. Its significance comes from its capacity to un-conceal or reveal a ‘real’ world of relations and intentions through which humans take power over reality. Thus, we should not be enthralled or distracted by the spectacular possibilities of XR in the context of tourism but seek to reveal the ways in which it manipulates the relational experience between person and world, referred to earlier as virtual dwelling.

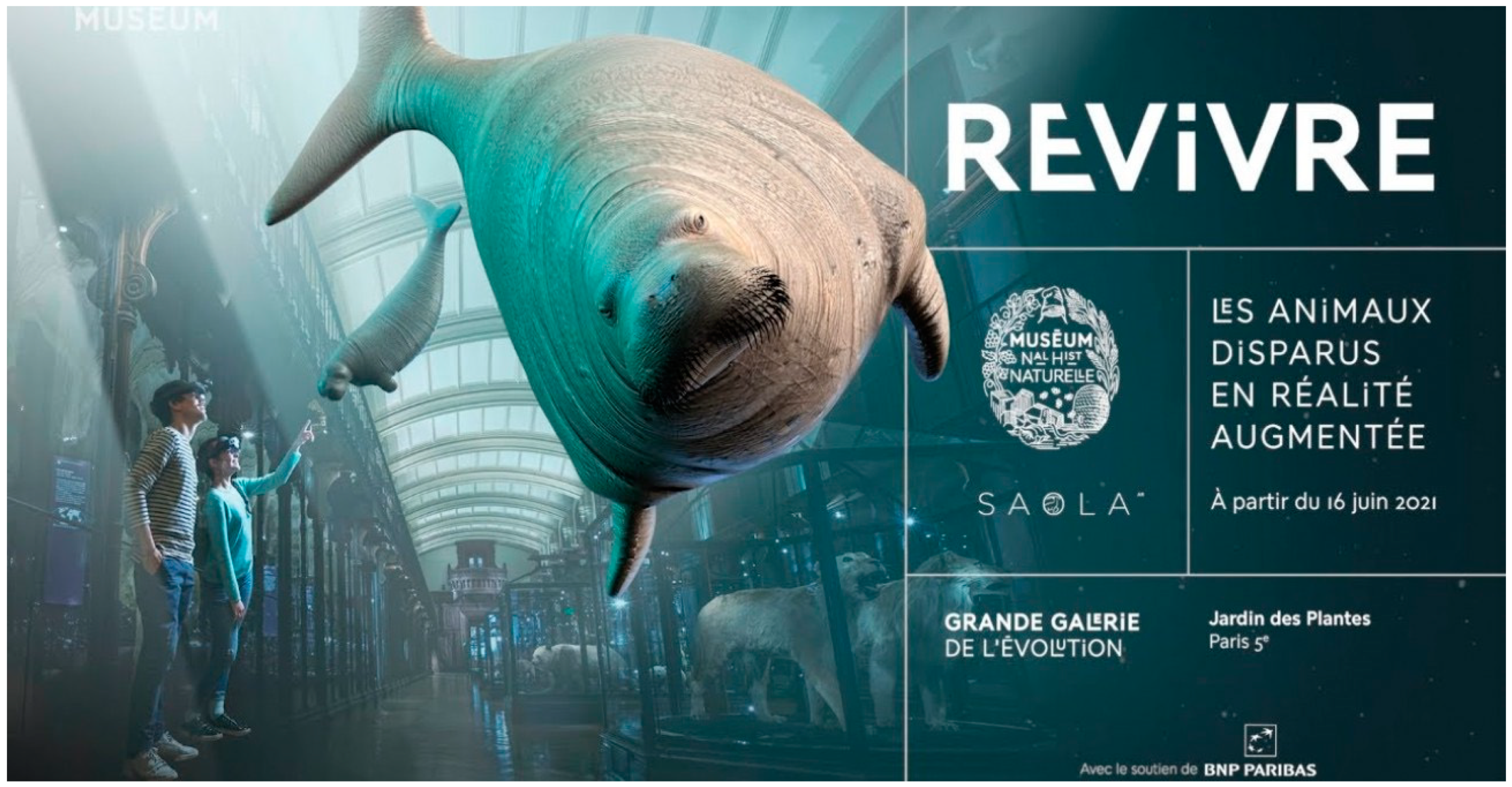

5. Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle

In 2021, the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle in Paris launched

REViVRE, meaning to live again, as an engagement strategy in the Grande Galerie de l’Évolution. Using Microsoft’s HoloLens, an experience in AR, visitors are brought face to face with extinct species such as the Dodo, the elephant-bird and the Tasmanian Tiger:

Who has never imagined walking alongside species that were once contemporary with humans, but are now extinct? … This experience also sheds light on current species suffering from anthropogenic pressure and tells us about the good practices of indigenous peoples from whom we can draw inspiration.

The website provides a video ‘taster’ of how VR breaths life back into nature. The video takes place in the static exhibits in the Grande Galerie de l’Évolution and shows two children encountering Dodo birds as if they were chickens roaming around a farmyard. The children try to touch a seal-like mammal seemingly floating in the sea above their heads and playfully avoid a very unthreatening sabre-toothed tiger (click on

Figure 1 to access YouTube ‘taster’ video from the museum’s website). Being face to face with and walking alongside extinct and endangered species provides a particularly intimate experience of person and world, enhanced by the allusion of being able to reach out and touch that which no longer exists.

Experience in this instance is a socially sanctioned message about the effect of humans on the natural world, one that illustrates and which cannot be separated from current reoccupations with the effect of human activity on the planet and its ecosystems, referred to as the Anthropocene. This is a constructed moment of geological time in the history of the earth where issues of climate change, sustainability, the degradation of forests, wildlife, natural resources, human and animal migration and so on appear, at times, almost overwhelming. Indeed, predictions about the death of the planet and the end of all life as we know it have played a significant part in driving public awareness and debate as well as forcing political change (see

Whyte 2018;

Hase et al. 2021;

Budziszewska and Jonsson 2021). In this sense,

REViVRE illustrates a point made by

Jackson (

2013, p. 45) in his ethnographic analysis of divination rites and storytelling among the Kuranko of Sierra Leone, where ‘people actively manipulate simulacra of the real world in order to grasp it more clearly and transform their experience of it’.

REViVRE is an experience of the consequences of human behaviour on the planet and ultimately the inevitability of death, of human mortality. However, it is also an experience of the possibility of redemption, that the situation is reversable—almost as if extinct species can be brought back to life, or at least there is hope for endangered species as long as the collective human ‘we’ changes course. The children in the video represent this possibility of redemption based upon educating the next generation about how they should live out their lives, educating them about the interrelatedness of human and world and what are appropriate attitudes to and behaviour in the world. This is experience as rebirth and renewal a reinforcing of the inseparability of Heidegger’s being-in-the-world.

Experiences and encounters that remind individuals about their own mortality based upon the death of the planet that sustains life are part of the established narrative of sustainability and the effects of climate change in public discourse. The merits or otherwise of these debates are not my focus here; what is of interest is the underlying technological revealing of the person world relationship, the vital, significant, reciprocal interweaving relationship between human subjects and the earth (

Jackson 2007). This is a relationship that has been referred to as earthy dwelling, one that ‘is inseparable from the non-human environment since being human is very much a being deeply embedded in a world shaped by such as animals, plants, and spirits…’ (

Palmer 2018, p. 107).

The natural world helps to sustain human life providing air to breath and water to drink. The sky reminds us of the importance of earthly atmosphere that protects the earth from the scorching rays of the sun. Animals, plants and also trees provide food to eat. The ground as land can be cultivated for food production. Oceans provide fish to eat and enable movement from one land to the next helping to establish and sustain meaningful relationships between humans—trade, migration, socio-cultural exchange and so on. Drawing on observations of hunter–gatherer peoples,

Ingold (

[2000] 2011b, p. 69) argues that recognition of the reasons why the environment must be conserved cannot be separated from the need to participate in conservation activities ‘caring for the environment is like caring for people: it requires a deep, personal and affectionate involvement… of one’s entire undivided being’. Interestingly, Ingold’s focus on ‘the wisdom’ of hunter–gatherer peoples illustrates the website comment quoted earlier about the need to draw inspiration from the good practices of indigenous peoples, practices that, above all else, are intended to care for the environment.

Experience in the context of

REViVE is, therefore, one intended to engender a caring attitude towards the earth and all that it supports. One of the ways this is achieved is by personalising the experience to encourage a sense of personal responsibility towards the world:

You find yourself transported into the daily lives and places of these animals from different continents, sometimes under the sea, in the heart of a Thai forest or in peaceful African grasslands. … these fascinating species come back to life before your eyes. … A voice tells you the story of these species and their interactions with humankind. Your guide? A passenger pigeon, which vanished at the beginning of the 20th century, with silvery pink wings, accompanies you from species to species. At the end of the journey, the animated species get together to give you a final wave goodbye…

VR experiences that bring humans face to face with what has been lost reminds people of the importance of caring on an individual basis. Caring for the environment is caring designed to maintain balance, to recognise and support the delicate but complex eco-systems that help to support human life. Care is a manifestation of what

Heidegger (

1962) refers to as a concernful being-in-the-world expressed as being-there, as being engaged with and in the world. Being-there is an understanding of being-with the presence of others in the world. This is a recognition of co-dependency on the basis of human beings belonging not only to and with each other but also belonging with what the world contains—plants, animals, air, water and so on. The revealing of VR technology that emerges through

REViVRE is a revealing of the co-dependent relationship between person and world and the need to protect, maintain and care for that relationship.

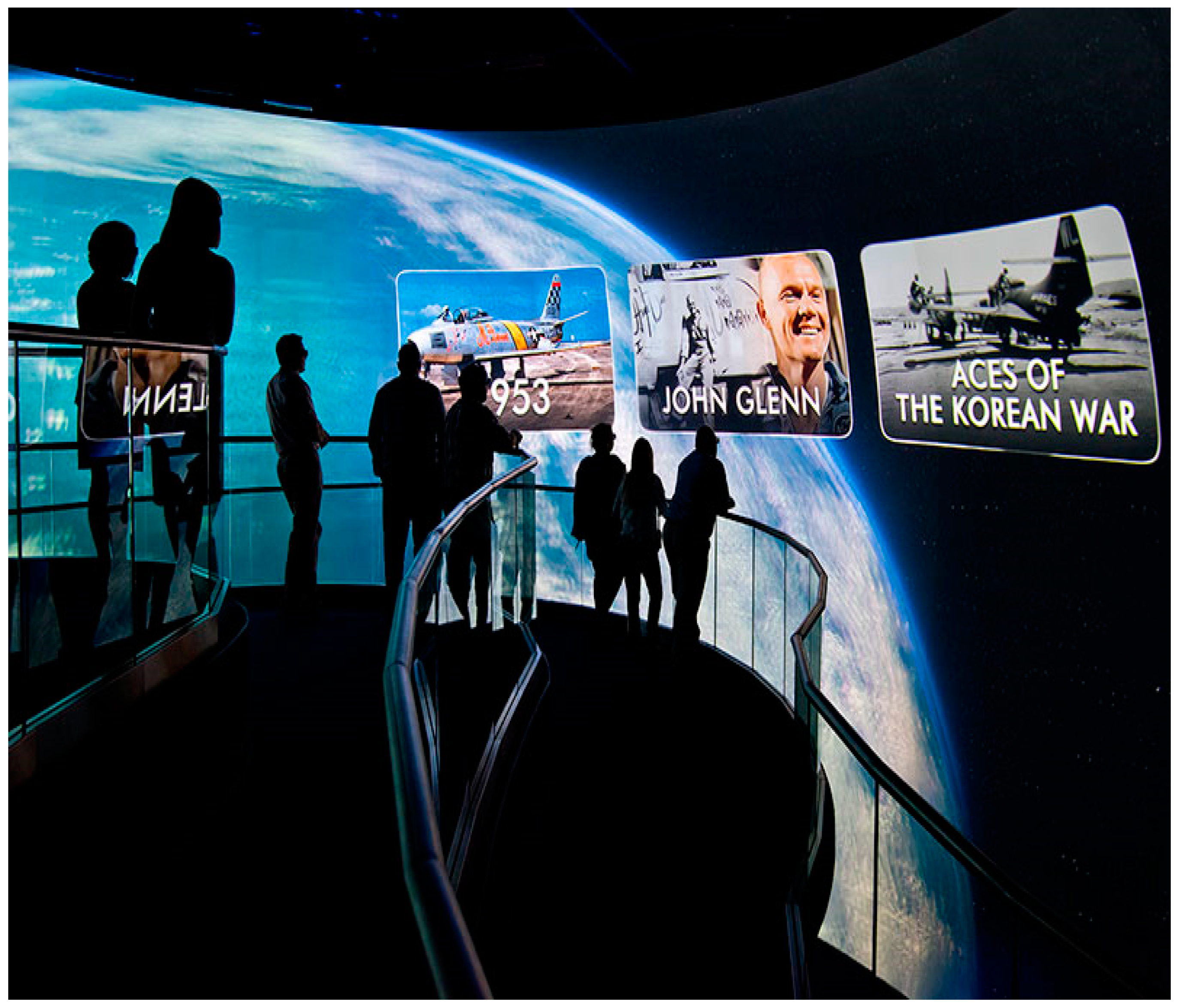

6. Kennedy Space Centre Visitor Complex

The AR example from the Kennedy Space Centre Visitor Complex in Florida is linked to the

Heroes and Legends exhibit focusing on a key moment in the history of the space programme in America. The exhibition focuses on three key missions in space exploration history, Mercury, Gemini and Apollo (see

Coates 2023):

Before humans walked on the Moon or lived on a space station for months at a time, brave space pioneers paved the way into the unknown and inspired a nation. … Heroes and Legends … tells the story of these heroes using personal stories and authentic artifacts from NASA’s early space programmes.

The immersive experience is created by AR holograms delivered through 3D glasses worn by visitors to the centre. Exhibition spaces are referred to as ‘theatres’ and include a media screen that wraps 220 degrees around the visitors. The 4D show places visitors on a floating platform, where they encounter holograms of ‘space-flown artifacts’ such as space capsules, iconic WW2 aeroplanes and contemporary fighter jets. The holograms are brought to life through sound, lighting, wind and smell effects. Interviews with astronaut heroes such as Buzz Aldren and Thomas Stafford provide first-hand accounts of their experiences (see

Figure 2 and

Figure 3).

The experience begins on the second floor of the centre, where visitors encounter the first theatre called What is a Hero? Then, it moves onto the second theatre called Through the Eyes of a Hero. The experience is personalised by bringing space heroes into the familiar realm of everyday relationships, as the Creative Director, Stephen Ricker explains in a video entitled

Behind the scenes of Heroes and Legends at Kennedy Space Centre Visitor Complex, ‘these people were just that, they were people, we really wanted to reflect that and have the audience start to ask that question to themselves, you know, who’s a hero to me’ (see

Coates 2023). Visitors are provided with the space centre’s response to this question as the space is organised into Pods, each of which is named with a specific heroic characteristic ‘Inspired, Passionate, Curious, Tenacious, Disciplined, Confident, Courageous, Principled and Selfless’ (

Kennedy Space Centre Visitor Complex 2021, n.p.)

However, the space centre encourages the idea of hero as being someone who is relatable, after all astronauts are exceptional people in the sense that not just anyone can become one. So, a rather eclectic range of other ‘heroes’ is provided ranging from a WW2 airline pilot and school children, to fictional heroes such as

Captain Kirk from the Star Trek TV/film franchise and the Disney Avatar

Katara from the film

The Last Airbender. As the Executive Producer, Jason Ambler explains in the same video, ‘we really wanted to make sure that all heroes are represented… to communicate the different layers of hero and how it became personal and how it became, kind of society’s heroes…’ (see

Coates 2023).

The combination of what is a hero and through the eyes of a hero cloaks a hero with the perception of ordinariness. A hero, it seems, could be a friend, neighbour, family member, even myself. This is important because the world revealed through technology is, in this instance, cosmological in the sense of being a world view that justifies and explains behaviour (

Wagner 1981;

Douglas 1996). So, the response to the question what is a hero is a culturally specific understanding of human exceptionalism based upon values such as courage and self-sacrifice. This is what it means to be an American hero. This is how a ‘good’ American behaves and, as such, the heroes at the space centre represent ‘what is known about the way the world is, the quality of the emotional life it supports, and the way one ought to behave while in it’ (

Geertz 1973, p. 127).

The space centre’s version of American hero as American exceptionalism is not one that is confined to national borders. Jason Ambler again, ‘Heroes and legends is ultimately an attraction celebrating the human spirit… certainly the astronauts that we are honouring… were on the side of society’s heroes and American heroes but ultimately, they were also world heroes’ (see

Coates 2023). The juxtaposition of space hero and everyday hero is a weaving together of what the anthropologist

Mircea Eliade (

1959) referred to as the sacred and the profane so that the lines between them become blurred, becoming an all-encompassing idea of the American hero as world hero, which is of course an illustration of American cultural hegemony.

Moreover, in being named the Kennedy Space Centre Visitor Complex, the centre is forever tied to an individual referred to by many people as an American hero, the 35th President of the United States, John (Jack) Fitzgerald Kennedy (JFK) who was assassinated in 1963. Kennedy’s heroic mantle originated with his role as a US naval reserve in WW2 turning him into a war hero for America’s war time generation (

Matthews 2011). As an assassinated President, JFK’s image, what

Roper (

2000) refers to as his heroic style of leadership and his legacy, were never tainted by a long term in office and the demands of re-election. There is not space here to interrogate JFK’s mythic status or to examine alternative understandings of the attribution of hero within American society (see for example

Goodman et al. 2002;

Wineburg and Monte-Sano 2008;

Kirsch 2021).

Nevertheless, his unfinished life solidified his image as an all-American hero in the public imagination (

Dallek 2003;

Wolfe 2013), illustrating

Balandier’s (

1972) concept of the charismatic chief who enjoys a special relationship with the people that authorise him to represent and ‘speak for’ the people. A similar argument has been made about the British Prime Minister, Winston Churchill (

Palmer 2003). JFK as a hero is important here because it reinforces the space hero-ordinary hero as world hero because this dynamic is legitimised by association with the ultimate hero, an American President. Experience as virtual dwelling in this example is one that reveals the universe of values defining America to itself and to others. A universe of American exceptionalism.

7. Louvre Museum

The final VR example is the Louvre Museum in Paris. In 2019, the Louvre launched its first VR project entitled

Mona Lisa: Beyond the Glass to celebrate the 500th anniversary of the death of Leonardo da Vinci. This project has since expanded into a range of ‘Louvre at Home’ VR experiences. The

Mona Lisa is one of the most famous, albeit very small, oil on wood Renaissance paintings in the world. Described as a cultural icon, the painting was stolen in 1911, recovered in 1913, and has been the catalyst for films and books and reproduced in a variety of cultural forms (

Bramly 1996;

Sassoon 2001;

Kemp and Pallanti 2017).

The VR experience was created to provide a more personal encounter with the

Mona Lisa (

Figure 4). This small painting is an extremely popular attraction for the museum, with numerous visitors crowding around the painting all trying to see it at the same time. ‘When a painting is as famous as the Mona Lisa, how can you engage with it on a personal level—get through the barrier of fame to discover its inner secrets?’ (

Louvre Museum 2021, n.p.). The eight-minute, immersive, interactive experience designed to provide this more personal experience is booked directly through the museum’s website (

https://www.louvre.fr/en, accessed on 25 June 2023) and accessed via the smartphone app VIVEPORT. This means that people do not have to visit Paris or the museum to ‘see’ the painting; they can be in a different location/country entirely, as the website states ‘the Mona Lisa in virtual reality in your own home’ (

Louvre Museum 2021, n.p.).

The VR experience encompasses sound and animated images to enable access to the painting, to allow a remote visitor to ‘get through the barrier of fame to discover its inner secrets’ (

Louvre Museum 2021, n.p.). As Dominque de Font-Réaulx, the Director of the Interpretation & Cultural Programming Department explains in a video about the project,

Beyond the Glass ‘offers visitors to go inside the painting not only to look at it from outside but to try to be within the universe of the painting’ (

Louvre Museum 2021, n.p.,

Figure 5). The virtual universe of the painting includes the life and times of da Vinci, details of the creative process, techniques and materials such as paint layering, the wood ‘canvas’ together with conservation, restoration and preservation challenges over time together with details of the sitter (

Vive Arts n.d.).

The experience begins by bringing the viewer face to face with the actual painting then moves the viewer back in time to an imagined setting to meet ‘the real woman’ painted by da Vinci. Frequently described as mysterious and by certain cultural conventions as being ‘neither beautiful, nor sexy’ (

Sassoon 2001, p. 3), she continues to enthral not just because people still debate who she was and how she lived but also because of her enigmatic smile (

Barolsky 2010;

Hales 2014). Within the virtual universe of the painting, personal details are provided—how her clothes and hair might have been styled and where she might have been painted; ‘we also find ourselves in the loggia where

Mona Lisa might have been sitting when she was painted’ (

Louvre Museum 2021, n.p.).

The VIVEPORT VR app delivers both on-site and remote visitors an immersive engagement with the painting akin to a conversation with the artist, the painting and the woman herself, an encounter that has been described as ‘a virtual “tête-à-tête”’ (

France 24 2019, n.p.). However, this encounter, this virtual

tête-à-tête, not only provides an experiential encounter with the universe of the painting, it also reveals the world or universe in which the painting is conserved, restored and displayed.

Experience as virtual dwelling in this example is one that reveals the universe or world of the

Mona Lisa as being about cultural wealth in terms of what a particular society considers ‘valuable’ at any given time. Something that has cultural value is worth keeping, protecting, maintaining, sharing or putting on displaying and in this sense the

Mona Lisa has much in common with

Weiner’s (

1985) concept of inalienable wealth. Inalienable wealth refers to the way in which objects legitimise groups right to exist, justifying their status as treasured possessions to be hand down through the generations. Although the

Mona Lisa is not precisely inalienable in the sense meant by Weiner, the underlying logic behind the concept is applicable to the painting. Indeed,

Clifford (

1988) discusses art-culture systems that reflect wider cultural rules of not just value but also gender and aesthetics. For Clifford, all collections embody hierarchies of value and given the Mona Lisa’s ‘celebrity’ status the painting is endowed with significant cultural value. Furthermore, in terms of the anthropology of art,

Morphy and Perkins (

2006, p. 10) argue that ‘exchange is one of the ways in which value is created, and material objects are both expressions of value and objects which in themselves gain in value through processes of exchange’. Exchange in the context of the

Mona Lisa is not related to the sale and purchase of the painting. It is extremely unlikely the French state, the owners of the painting, will ever sell it. Exchange in this instance is that which occurs between the viewer and the viewed, the painting ‘gives’ its mystery, its iconic status, cultural and commercial

value in exchange for the viewer’s response—admiration, awe, joy, a ‘must see’ attraction and so on. Even expressions of frustration at the queuing time, crowding and the 30 s limit in front of the painting reinforces the status of the painting as something worth the effort involved to see it (see

Henry 2000;

Willsher 2018).

There are some parallels here with the anthropological concept of exchange and that of reciprocity, whereby social relationships exist and are maintained by the giving or exchanging of, for example, goods, land, money, objects, and jewellery (

Mauss [1954] 2001;

Kesting et al. 2021). However, as with the concept of inalienable wealth, the

Mona Lisa does not illustrate the underlying premise of exchange and reciprocity, that of obligation. The obligation that is established to give, to receive and, more importantly, to reciprocate. For the

Mona Lisa, the exchange is one that reaffirms and justifies the paintings cultural value in terms of something that needs to be put on display so that it can be seen and looked at by people. This means that the obligation inherent in exchange and reciprocity is transferred onto the museum, which takes on the obligation to open up collections for public consumption. The need to grow museum visitor numbers is not merely an economic necessity to generate income or justify funding, it is a moral obligation—moral in the sense of being a social good—that works to sustain, reinforce and reaffirm the basis upon which value as cultural wealth is understood within a society at any given time.

The

Beyond the Glass virtual universe of the

Mona Lisa illustrates

Heidegger’s (

2001b) discussion of artwork, specifically his interpretation of Van Gogh’s 1886 painting, entitled

A Pair of Shoes in which he argues that art is less about beauty or aesthetics and more about truth. In particular, the disclosing or revealing of truth as it pertains to a society’s shared understanding of what matters in their world—a truth or mattering that is revealed by the

work of the shoes, by the wearing and using of the shoes in the world. As

Heidegger (

2001b, p. 35, original emphasis) argues, ‘Van Gogh’s painting is the disclosure of what… the pair of peasant shoes,

is in truth. … the truth of beings setting itself to work’.

Most museums, and specifically nationally significant ones such as the Louvre, are, therefore, highly visible manifestations of ‘truth’ in terms of what matters in and to the societies in which they are conceived and used, manifestations of the powerful economic and political forces (people, institutions, financial markets) driving what deserves to be seen as culturally significant and where objects of cultural value should be located. The use of XR in museums, particularly that which enables even more people to access the Mona Lisa, is yet another way in which these forces communicate and maintain their interpretation of cultural value at any given time. The revealing of XR technology, in the sense meant by Heidegger, is a revealing of the relations and intentions by which dominant forces are able to extend their reach, their interpretation of cultural value, beyond the confines of official repositories of cultural consumption.

8. Conclusions

XR in museums is telling a story of not only the relationship between humans and world but also of the values and beliefs underpinning that relationship. A virtual tourism experience reveals a range of stories. The story from the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle concerns the interrelatedness of human and world and of the appropriate attitude towards and behaviour in the world, namely caring.

The story from the Louvre is one that reveals the universe or world in which a particular understanding of cultural value and cultural wealth is determined. In other words, what a particular society considers ‘valuable’ at any given time. The attribution of value is important because it justifies decisions as to what is worth saving keeping, protecting, maintaining and sharing. It also, of course, legitimises funding decisions made for ‘the people’ by those individuals who hold the power to decide.

The story from the Kennedy Space Centre Visitor Complex is one that reveals the hero as an expression of American values, an aspirational story, whereby ordinary people can become heroes too if they behave in ways that align with the characteristics depicted in and represented by the astronaut heroes of space exploration. This story is one that travels beyond the borders of the nation to reinforce a message to the world outside about the importance of American exceptionalism.

While all these stories illustrate the revealing possibilities of technology, Heidegger’s argument does not explain why that which is revealed holds sway over the imagination; in effect, why it

works. Moreover, while I understand Heidegger’s argument about ignoring the mechanics of technology—something that is not easy to do with XR technologies because almost every discussion includes explanations of the specific VR/AR/mixed technology involved, how a particular experience was designed and constructed including the technological challenges and how these were resolved—Heidegger, alone does not help us to fully understand what it means to ‘experience’ the virtual-tourism-world experience. Here, we need to look to the work of the anthropologist,

Alfred Gell (

1992, p. 44), who argued that technology is a system of enchantment that casts ‘a spell over us so that we see the real world in an enchanted form’. However, we not only see the world but also hear it, touch it, feel it, smell it and imagine it as sensuous, embodied beings in the world (

Csordas 1994;

Palmer 2018). Although there is not scope to do so here, bringing the concept of enchantment and that of embodiment into a dialogue with what I have termed virtual dwelling has much to contribute to our understanding of what a digitally modified experience of self and world means—what it both looks and feels like to dwell, to be absorbed by and within a virtual-tourism-world. Ultimately, what technologically modified–manipulated experiences of a virtual-tourism-world reveal is experience as virtual dwelling, experience of the embeddedness of being human-in-the-world.