Virtual Craft: Experiences and Aesthetics of Immersive Making Culture

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

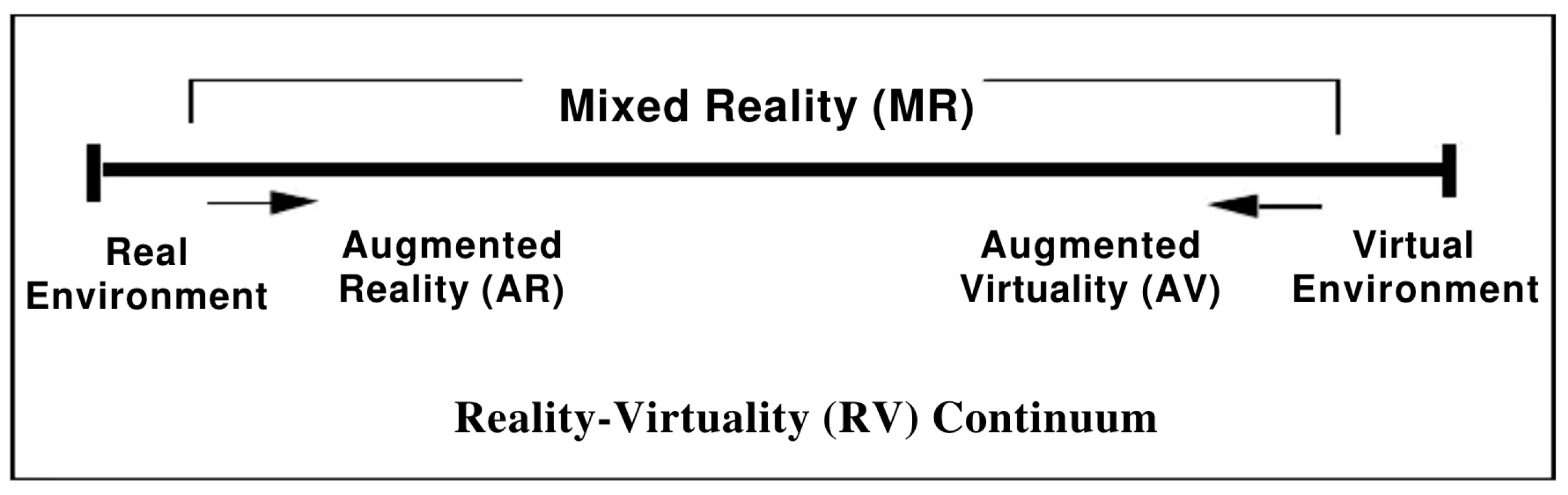

2.1. Immersive Media Studies

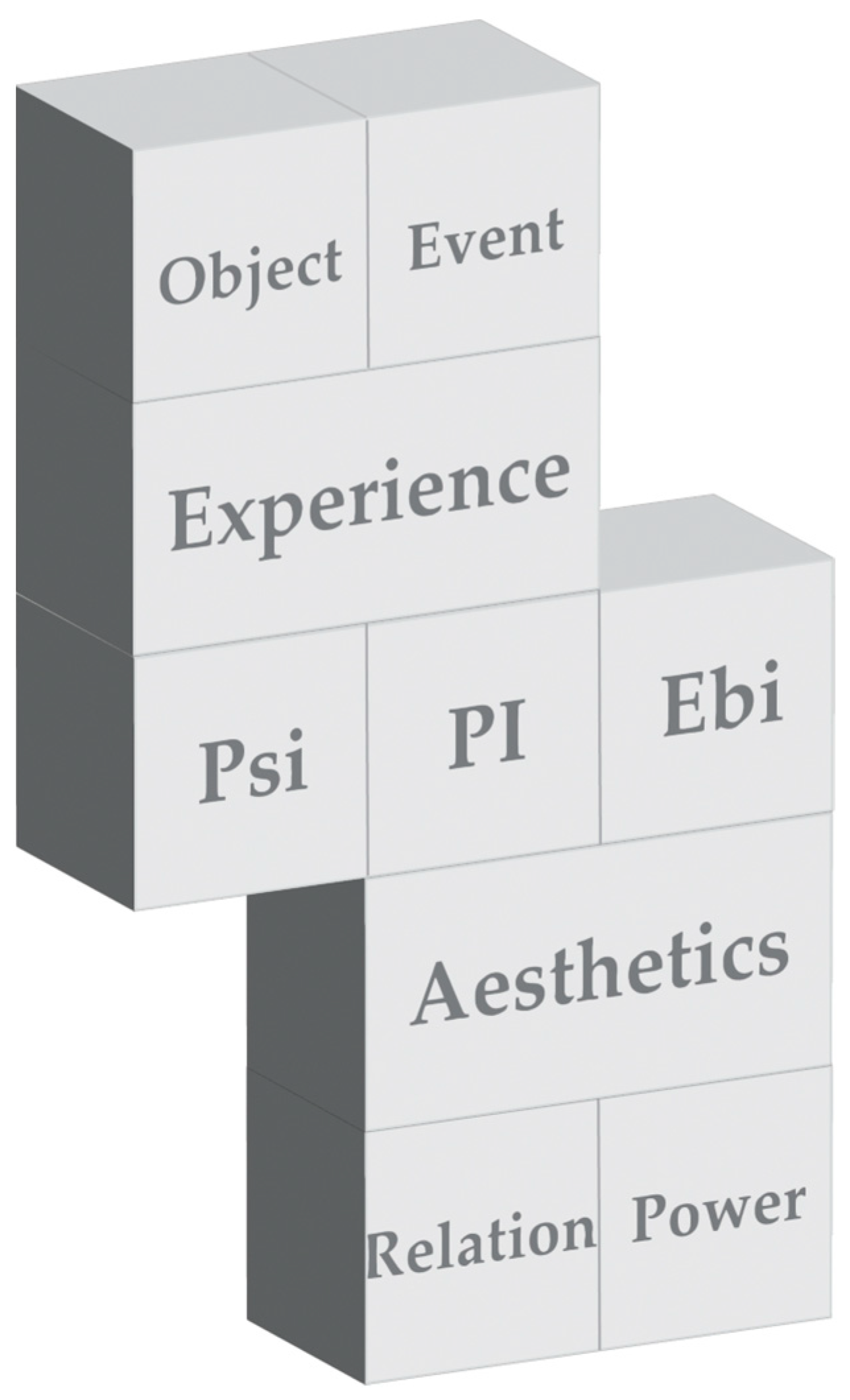

- Plausibility illusion (Psi): Within an optimal immersive media system, various sensory displays are typically coupled with a tracking system. Notably, the degree of immersion is largely determined by the system’s physical attributes, which are frequently associated with hypermediated technologies. The question, “what is happening?” raised by participants, can be addressed through the operation of the plausibility illusion.

- Place illusion (PI): The concept of presence, which refers to the sensation of being in a particular location, has its roots in teleoperator systems. In immersive media, participants experience a sense of existing within the depicted place and time through the use of immersive displays. The manifestation of place illusion is contingent upon participants probing the limits of immediacy. The more they inquire about “where is it?” and “when is it?”, the more the likelihood of interruptions in the illusion of being present increases.

- Embodiment illusion (Ebi): In immersive media, the human body serves as the nexus where the place illusion and plausibility illusion intersect. These media do more than just reshape our perception of place and reality; they also modify our bodily awareness. When a participant has a strong sense of presence (PI) and perceives the unfolding events as real (Psi), both their body and mind engage fully, reacting as though the experience is truly happening to them. Notably, the embodied cognition experienced during the actual perception of an object can be readily reactivated and relived, even when the object is absent (Lakoff 2012, p. 781). As such, the embodiment illusion underscores the integration of physical and cognitive processes, amplifying the overall immersive impact of the experience.

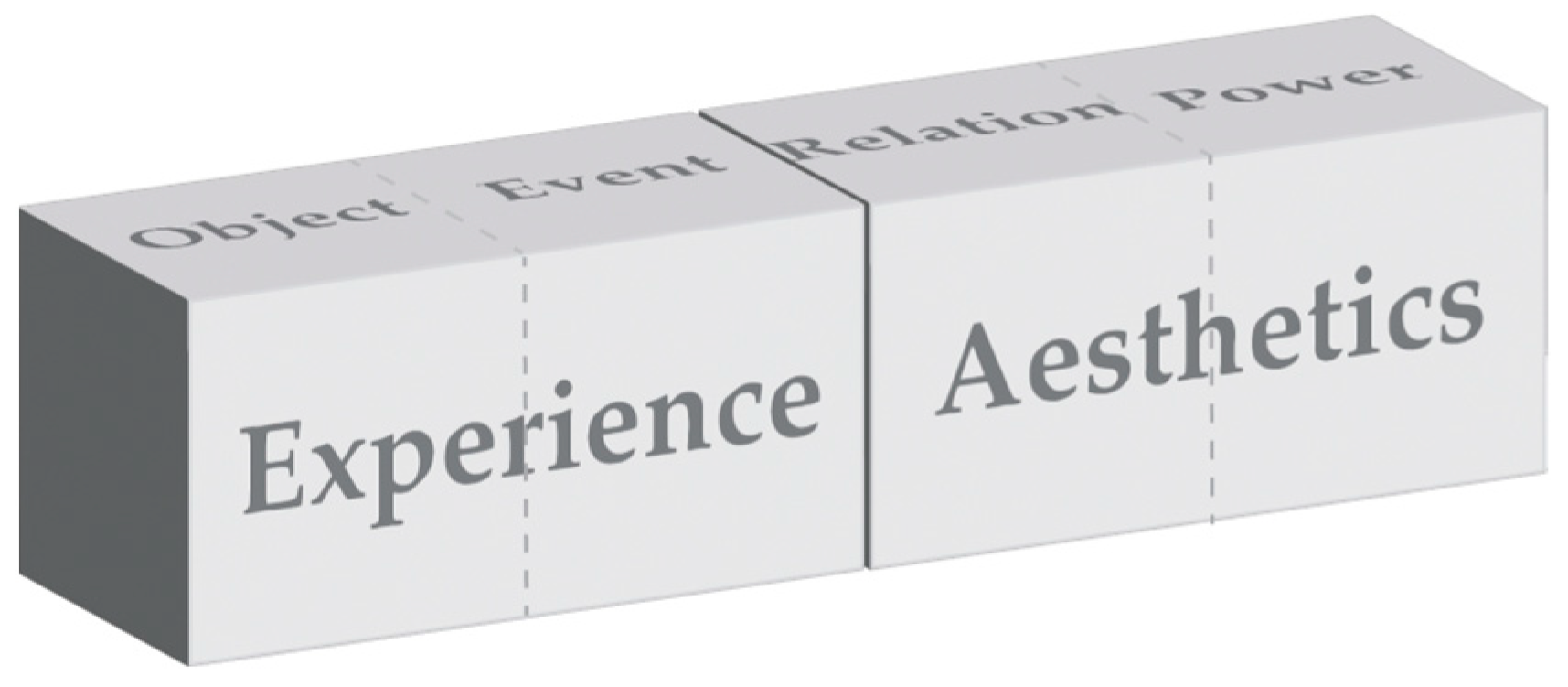

2.2. The Study of Materiality, Making Culture, and Crafting

- Experience: This facet of craft delves into the sensory, motoric, and emotional dimensions that collectively shape the holistic experience of crafting. It is segmented into two subcomponents—object and event.

- Object: Central to the crafting process, this subcomponent emphasizes the tangible materials and tools. Their involvement not only determines the final product but also amplifies the sensory connection of the maker.

- Event: Capturing the less tangible yet equally vital aspects of crafting, this subcomponent encompasses the maker’s motoric reactions and emotional resonances, the ambiance of the crafting environment, and the inherent temporal evolution of the crafting experience.

- Aesthetics: Craft, recognized as a fundamental facet of human existence, embodies both the appreciation of beauty in the crafted item and the profound expression of human dexterity and societal values. This dimension can be distilled into two subcomponents—relation and power.

- Relation: Rooted in the interconnected nature of crafting, this subcomponent accentuates the ties between the maker, the crafted item, and the broader crafting community. It signifies more than just shared values and a collective sense of belonging—it represents our innate dexterity and the fundamental human drive to create.

- Power: This subcomponent celebrates the capacity of craft to communicate powerful messages and values beyond mere visual appeal. Through its transformative potential, craft can evoke profound emotions, incite reflection, and even advocate for a more humane material existence.

2.3. Triadic Semiotics

2.4. The Integrated Conceptual Framework

3. Analysis

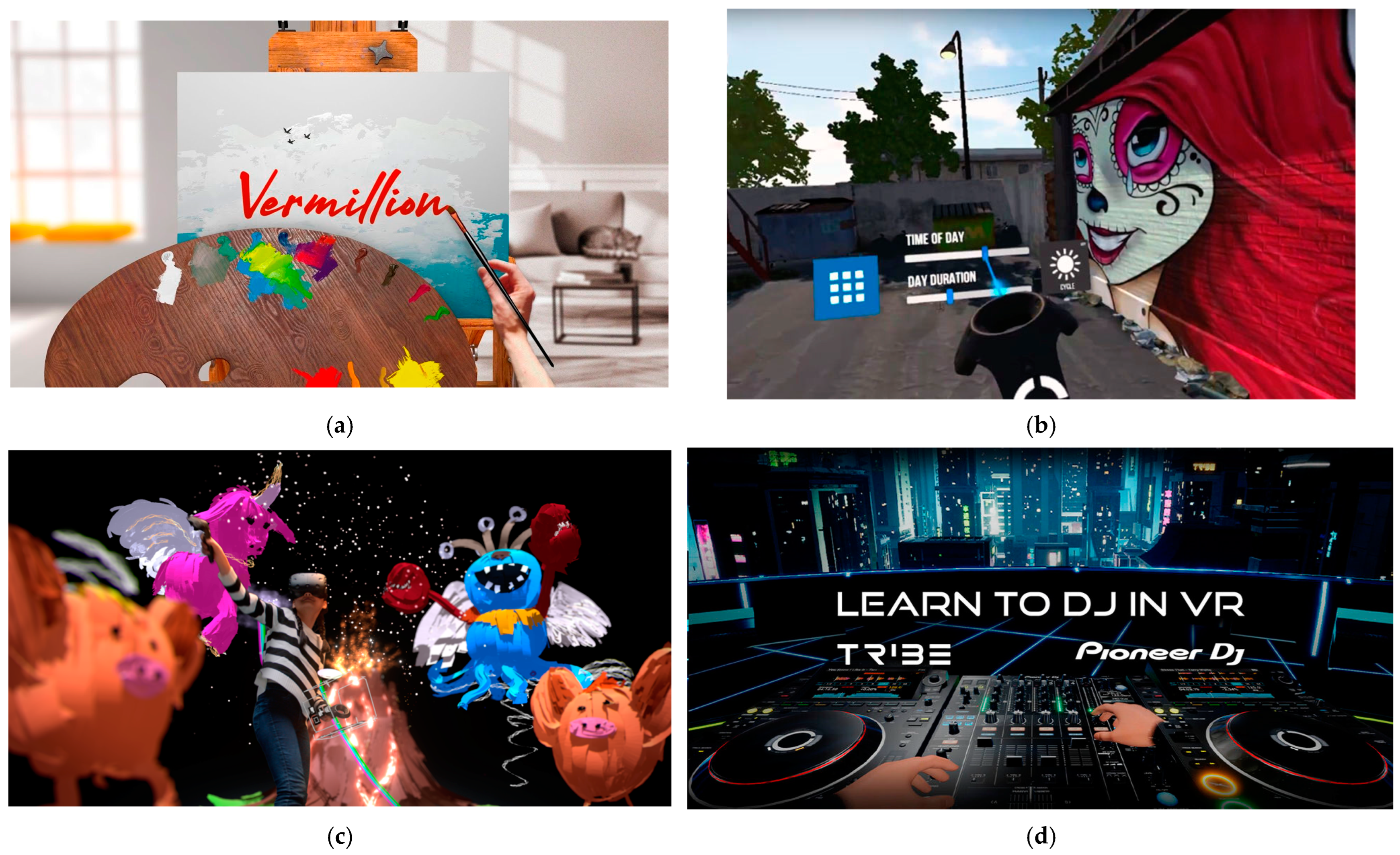

3.1. The Landscape of Immersive Making Culture

3.2. Experiences and Aesthetics of Virtual Craft: The Case of Tilt Brush

3.2.1. The Psi of Tilt Brush

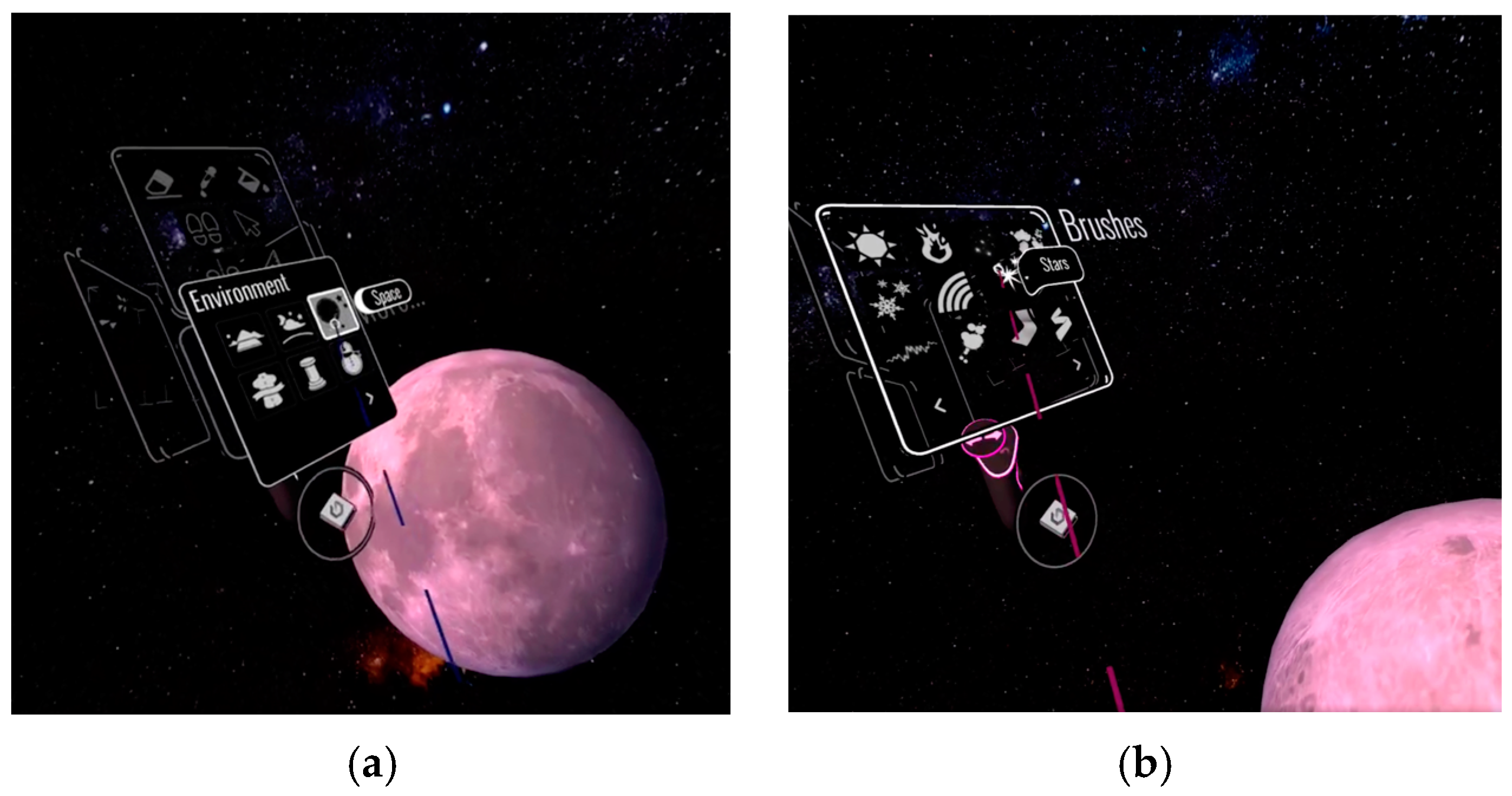

- Tilt Brush is a specialized three-dimensional painting program explicitly designed for head-mounted displays (HMDs), which serves as foundational instruments for delivering a robust virtual experience. Upon activating the application within the HMD, users are greeted with an extensive blank landscape complemented by an ambient soundscape. This object-focused setup provides an array of customization options for the virtual environment, including adjustments to lighting, background selection, and the prevailing atmospheric hue (refer to Figure 7). Moreover, the application boasts preset scenic alternatives, such as a starlit night or a snowy winter day. These preliminary configurations not only lay the groundwork for upcoming crafting endeavors but also ground users in the realm of “what is happening”, guiding them towards active engagement with the available tools and features. This preparatory phase is crucial for establishing the context before users venture into dynamic interactions, ensuring their sustained immersion in the designated virtual setting.

- Once users have configured their desired environment, which offers a vast open space in 360 degrees, they naturally begin to explore the tools for painting. Each hand holds a motion controller; one acts as the palette for painting work while the other represents the painting tools, such as brushes or their virtual substitutes. The painting palette is meticulously iconized to resemble real objects, including various brushstrokes, paint colors, and 3D shapes (see Figure 7). While these virtual devices may initially feel hypermediated, the interaction with painting icons that closely resemble real objects gradually immerses the user.

3.2.2. The PI of Tilt Brush

- As emphasized by its tagline, “Your room is your canvas” (see note 4 above), Tilt Brush enables users to freely explore and utilize the three-dimensional space in front of them without the constraints of a physical medium. By using hand controllers as brushes and palettes, users can create the experience of life-size paintings vividly and up close. What may have once felt hypermediated is now perceived as a graphically friendly and intimate interface.

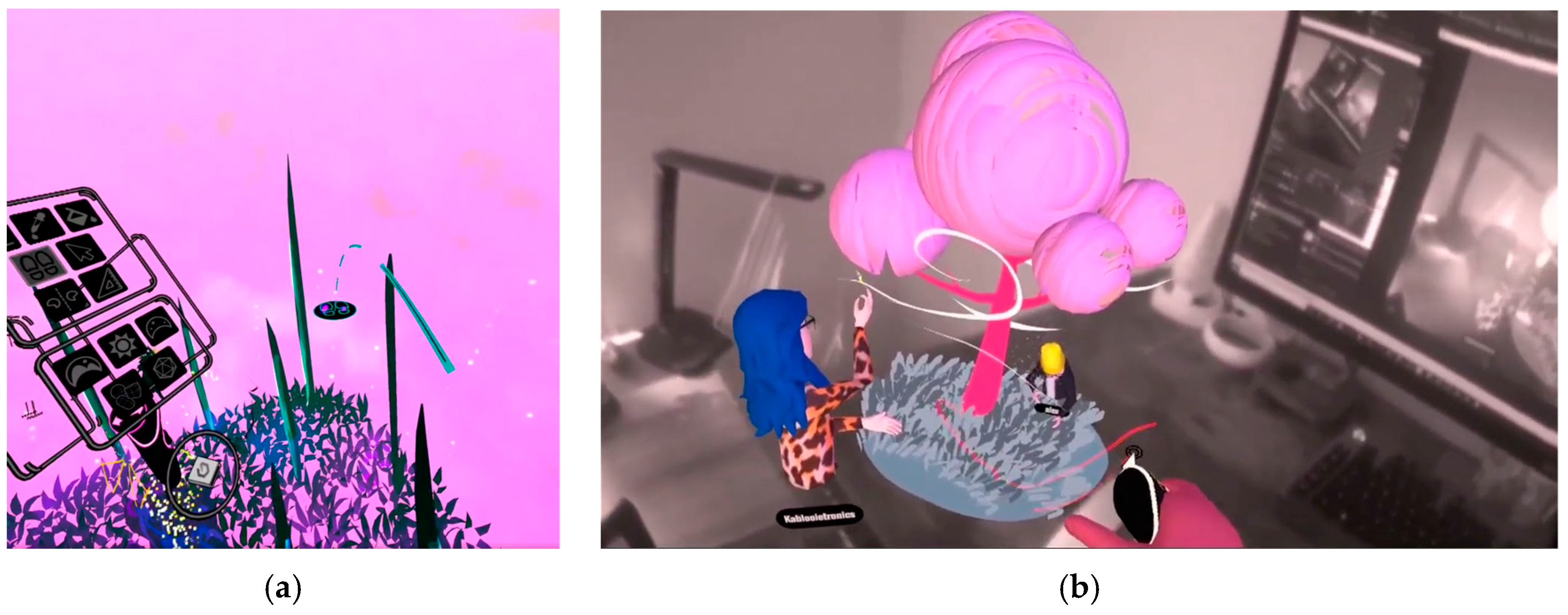

- The visual elements generated by Tilt Brush’s painting feature, such as points, lines, and planes, exist as 3D objects with their vector values. Users can intuitively manipulate these elements in terms of their shape, size, and position, just as they would interact with physical three-dimensional objects (see Figure 8). These indexical interactions, occurring causally between the users’ inputs and materialized outputs, further enhance the users’ sense of presence, making them feel here and now in their own created canvas.

- During the development of Tilt Brush, Google initiated The Tilt Brush Artist in Residence (AiR) program, which invited over 60 artists from various disciplines to participate6. The program welcomed painters, graphic designers, graffiti artists, cartoonists, dancers, and IT technicians, among others. One notable commentator on the project was McCloud (Google AR & VR 2017), who observed the shift from traditional two-dimensional painting practices to the new reality of painting in three-dimensional space. In the virtual three-dimensional environment created by Tilt Brush, the artists found themselves encircling their works, and in turn, being encircled by their own creations (see Figure 8). Many artists who took part in the AiR program expressed similar experiences, describing the sensation of walking directly into their workspace or “inhabiting” their artwork.

3.2.3. The Ebi of Tilt Brush

- Tilt Brush’s immersive making events blur the traditional boundaries between painting and sculpture, empowering users to engage with the world of “painted sculpture” and “sculpted painting” (Kim 2022, p. 28). By surpassing the limitations of 2D painting, it establishes new rationalities for three-dimensional expression and exploration, providing a unique way to interact with the virtual environment. One notable example is the teleport feature (see Figure 9) in Tilt Brush, which allows users to virtually hop to different spots within their environment, enabling them to determine their perspective and relation to the world as independent makers. This transformation in the maker–object relationship is also evident in the interaction between the artwork created in Tilt Brush and the user. The user actively engages with the 360-degree virtual space and is required to choose their narrative perspective at every moment. As a result, the power to shape the narrative of immersive content is largely transferred and decentralized to the users, who can now seek meaningful answers to fundamental questions, such as “why and how do I exist here?” and ultimately “who am I?” in this world.

- In addition to the diverse power structures inherent in their immersive making processes and outcomes, Tilt Brush makers are extensively involved in nested relationships with other makers and the networked transformation of the digital ecosystem. The example of Tilt Brush illustrates how many immersive makers import 3D objects from online open libraries into their programs to modify them (or vice versa), extract their work as graphic files to connect with other applications, and contribute to sharing platforms. This trend has accelerated since Google released Tilt Brush as open-source code in 2021. The open-source code for Tilt Brush is readily available on its GitHub page7, which is a key platform in the global development ecosystem that hosts source code and facilitates digital collaboration. Following the open-source release of Tilt Brush, a developer named Icosa8 created Open Brush9 on GitHub, which is essentially a free version of the original program. Icosa launched a beta version of a gallery to allow sharing of do-it-yourself creations and recently announced an XR version that integrates with real-world spaces. Another developer, Rendever (2022), utilized the Tilt Brush source code to create MultiBrush—a multiplayer version that lets multiple users connect simultaneously to collaborate on artwork (refer to Figure 9).

3.2.4. Summary of Tilt Brush Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- Virtual craft as an emerging trend in immersive making culture: This study identified a trend in immersive making culture that can be described as virtual craft. The scope of virtual craft appears to be gradually expanding beyond traditional art genres and forms of making, such as painting and composing music, toward more innovative directions, including spatial design, social networking, and world-building. This trend reflects the exploration of the new materiality in the media and opens up possibilities for future development.

- The current state of virtual craft: Through the construction and application of the immersive making culture model, significant characteristics of the current virtual craft were observed. One key aspect was its reliance on the iconic features of objects, emphasizing the plausibility illusion through hypermediated technologies, such as enhanced versions of HMDs. The narrative question of “what is happening?” took precedence over specific events or dynamic relations between various objects rooted in a specific time and space.

- Possibilities and limitations of virtual craft: The analysis of Tilt Brush, which was based on the integrated framework, revealed that this typical case of virtual craft enabled users to blur the boundaries between painting and sculpture, offering new rationalities for three-dimensional visual expression. The ability to freely navigate and manipulate virtual space using motion controllers enhanced the sense of presence and engagement, resulting in a transformative power relationship between the maker and the media. However, the case of Tilt Brush also highlighted the technical limitations of virtual craft in fully achieving its aesthetic goals, as there is an ongoing process of remediation between immersive media and traditional art forms.

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Meta Quest Store. Available online: https://www.oculus.com/experiences/quest/ (accessed on 7 July 2023). |

| 2 | Vermillion. Available online: https://vermillion-vr.com/ (accessed on 7 July 2023). |

| 3 | Kingspray Graffiti. Available online: http://infectiousape.com/ (accessed on 7 July 2023). |

| 4 | Tilt Brush. Available online: https://www.tiltbrush.com/ (accessed on 7 July 2023). |

| 5 | Tribe XR|As a DJ in Mixed Reality. Available online: https://www.tribexr.com/ (accessed on 7 July 2023). |

| 6 | Tilt Brush Artist in Residence. Available online: https://www.tiltbrush.com/air/ (accessed on 7 July 2023). |

| 7 | Tilt Brush GitHub Page. Available online: https://github.com/googlevr/tilt-brush (accessed on 7 July 2023). |

| 8 | Icosa Foundation GitHub Page. Available online: https://github.com/icosa-gallery (accessed on 7 July 2023). |

| 9 | Open Brush. Available online: https://openbrush.app/ (accessed on 7 July 2023). |

References

- Al-Thani, Latifa Khalid, and Divakaran Liginlal. 2018. A Study of Natural Interactions with Digital Heritage Artifacts. Paper presented at 3rd Digital Heritage International Congress (DigitalHERITAGE) Held Jointly with 24th International Conference on Virtual Systems & Multimedia (VSMM), San Francisco, CA, USA, October 26–30; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, Chris. 2012. Makers: The New Industrial Revolution. New York: Crown Business. [Google Scholar]

- Bansal, Gaurang, Karthik Rajgopal, Vinay Chamola, Zehui Xiong, and Dusit Niyato. 2022. Healthcare in Metaverse: A Survey on Current Metaverse Applications in Healthcare. IEEE Access 10: 119914–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benito, Victoria López, Tània Martínez Gil, and Irina Grevtsova. 2013. Restitution on site and virtual archeaology: Two lines for research. Paper presented at Digital Heritage International Congress (DigitalHeritage), Marseille, France, October 28–November 1; p. 755. [Google Scholar]

- Berners-Lee, Tim. 1996. Focus on Intercreativity Instead of Interactivity: Create Things Together. Paper presented at the 5th International World Wide Web Conference, Paris, France, May 6–10. [Google Scholar]

- Bolter, Jay David, and Richard Grusin. 1999. Remediation: Understanding New Media. Cambridge: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bolter, Jay David, Maria Engberg, and Blair MacIntyre. 2021. Reality Media: Augmented and Virtual Reality, Kindle ed. Cambridge: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bosworth, Melissa, and Lakshmi Sarah. 2018. Crafting Stories for Virtual Reality, 1st ed. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant, Levi R. 2014. Onto-Cartography: An Ontology of Machines and Media. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bucher, John. 2018. Storytelling for Virtual Reality: Methods and Principles for Crafting Immersive Narratives. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Charny, Daniel. 2011. Thinking of Making. In Power of Making: The Importance of Being Skilled. Edited by Daniel Charny. London: V&A Publishing, pp. 6–13. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Pearly, Mark Griswold, Hao Li, Sandra Lopez, Nahal Norouzi, Gregory Welch, and Yu Jingyi. 2022. Immersive Media Technologies: The Acceleration of Augmented and Virtual Reality in the Wake of COVID-19. World Economic Forum White Paper. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/reports/immersive-media-technologies-the-acceleration-of-augmented-and-virtual-reality-in-the-wake-of-covid-19 (accessed on 7 July 2023).

- Coole, Diana, and Samantha Frost. 2010. New Materialisms: Ontology, Agency, and Politics. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Crow, David. 2016. Visible Signs: An Introduction to Semiotics in the Visual Arts, 3rd ed. London: Bloomsbury. [Google Scholar]

- Dogramaci, Burcu, and Fabienne Liptay. 2016. Immersion in the Visual Arts and Media. In Immersion in the Visual Arts and Media. Edited by Fabienne Liptay and Burcu Dogramaci. Leiden: Brill Rodopi, pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Florez M., Juan Fernando. 2022. Immersive Virtual Classroom Model for a Synchronous Blended Learning Environment. Paper presented at Congreso de Tecnología, Aprendizaje y Enseñanza de la Electrónica (XV Technologies Applied to Electronics Teaching Conference), Teruel, Spain, June 29–July 1; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freyermuth, Gundolf S. 2016. From Analog to Digital Image Space: Toward a Historical Theory of Immersion. In Immersion in the Visual Arts and Media. Edited by Fabienne Liptay and Burcu Dogramaci. Leiden: Brill Rodopi, pp. 165–203. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs, Raymond W., Jr. 1994. The Poetics of Mind: Figurative Thought, Language, and Understanding. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Google AR & VR. 2017. Tilt Brush Artist in Residence. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LBJPIgNXUDI (accessed on 7 July 2023).

- Grant, Iain Hamilton. 2006. Philosophies of Nature after Schelling. New York: Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Grau, Oliver. 2003. Virtual Art: From Illusion to Immersion. Cambridge: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Greengard, Samuel. 2019. Virtual Reality, Kindle ed. Cambridge: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hatch, Mark. 2013. The Maker Movement Manifesto: Rules for Innovation in the New World of Crafters, Hackers, and Tinkerers. New York: McGraw Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Hollick, Matthew, Christian Acheampong, Mahdi Ahmed, Daphne Economou, and Jeffrey Ferguson. 2021. Work-in-Progress-360-Degree Immersive Storytelling Video to Create Empathetic Response. Paper presented at 7th International Conference of the Immersive Learning Research Network (iLRN), Eureka, CA, USA, May 17–June 10; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kachach, Redouane, Diego González Morín, Francisco Pereira, Pablo Perez, Ignacio Benito, Jaime Ruiz, Ester González, and Alvaro Villegas. 2021. A Multi-Peer, Low Cost Immersive Communication System for Pandemic Times. Paper presented at IEEE Conference on Virtual Reality and 3D User Interfaces Abstracts and Workshops (VRW), Lisbon, Portugal, March 27–April 1; pp. 691–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan-Rakowski, Regina, and Kay Meseberg. 2019. Immersive Media and Their Future. In Educational Media and Technology Yearbook. Edited by Robert Maribe Branch, Hyewon Lee and Sheng Shiang Tseng. Cham: Springer Nature, vol. 42, pp. 143–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Minhyoung. 2022. A Semiotic Adaptation of Materiality Studies: With a Focus of DIY Making Cultures. Semiotic Inquiry 72: 7–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Minju, Heejeong Ko, Jonghun Choi, and Jungjin Lee. 2023. FlumeRide: Interactive Space Where Artists and Fans Meet-and-Greet Using Video Calls. IEEE Access 11: 31594–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klippel, Alexander, Danielle Oprean, Jiayan Zhao, Jan Oliver Wallgrün, Peter LaFemina, Kathy Jackson, and Elise Gowen. 2019. Immersive Learning in the Wild: A Progress Report. In Immersive Learning Research Network: Communications in Computer and Information Science. Edited by Dennis Beck, Anasol Peña-Rios, Todd Ogle, Daphne Economou, Markos Mentzelopoulos, Leonel Morgado, Christian Eckhardt, Johanna Pirker, Roxane Koitz-Hristov, Jonathon Richter and et al. Cham: Springer Nature, vol. 1044, pp. 506–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuchera, Ben. 2020. Oculus Quest 2 Review: Smaller, Cheaper, Better. Polygon. Available online: https://www.polygon.com/reviews/2020/9/16/21437762/oculus-quest-2-review-virtual-reality-vr-facebook-oculus-power-resolution-tracking (accessed on 7 July 2023).

- Lakoff, George. 2012. Explaining Embodied Cognition Results. Topics in Cognitive Science 4: 773–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakoff, George, and Mark Johnson. 1980. Metaphors We Live By. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Langa, Sergi Fernández, Mario Montagud, Gianluca Cernigliaro, and David Rincón Rivera. 2022. Multiparty Holomeetings: Toward a New Era of Low-Cost Volumetric Holographic Meetings in Virtual Reality. IEEE Access 10: 81856–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latour, Bruno. 1999. On recalling ANT. In Actor Network Theory and After. Edited by John Law and John Hassard. Oxford: Blackwell, pp. 15–25. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Yunhee. 2017. Charles Sanders Peirce. Seoul: Communication Books. [Google Scholar]

- Lužnik, Nika, and Michael Klein. 2015. Interdisciplinary workflow for Virtual Archaeology. Paper presented at Digital Heritage 2015, Granada, Spain, September 28–October 2; pp. 177–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manovich, Lev. 2000. The Language of New Media. Cambridge: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Margetts, Martina. 2011. Action Not Words. In Power of Making: The Importance of Being Skilled. Edited by Daniel Charny. London: V&A Publishing, pp. 38–47. [Google Scholar]

- Meta Quest. 2023. Verified User Reviews on the Meta Quest Store. Available online: https://www.meta.com/kr/en/legal/quest/verified-user-reviews/?utm_source=www.oculus.com&utm_medium=dollyredirect (accessed on 7 July 2023).

- Milgram, Paul, and Fumio Kishino. 1994. A taxonomy of mixed reality visual displays. IEICE Transactions on Information Systems E77-D: 1321–29. [Google Scholar]

- Milgram, Paul, Haruo Takemura, Akira Utsumi, and Fumio Kishino. 1994. Augmented reality: A class of displays on the reality-virtuality continuum. Paper presented at Photonics for Industrial Applications, Boston, MA, USA, October 31–November 4; Proceedings vol. 2351. pp. 282–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mordor-Intelligence. 2023. Extended Reality (XR) Market Size & Share Analysis: Growth Trends & Forecasts (2023–2028). Available online: https://www.mordorintelligence.com/industry-reports/extended-reality-xr-market (accessed on 7 July 2023).

- Paradis, Marie-Anne, Théophane Nicolas, Ronan Gaugne, Jean-Baptiste Barreau, Réginald Auger, and Valérie Gouranton. 2019. Making Virtual Archeology Great Again (Without Scientific Compromise). The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences XLII-2/W15: 879–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peirce, Charles Sanders. 1931–1935. The Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce [CP]. Edited by Charles Hartshorne and Paul Weiss. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, vols. 1–6, Available online: https://colorysemiotica.files.wordpress.com/2014/08/peirce-collectedpapers.pdf (accessed on 7 July 2023).

- Powell, Michael O., Aviv Elor, Ash Robbins, Sri Kurniawan, and Mircea Teodorescu. 2022. Predictive Shoulder Kinematics of Rehabilitation Exercises Through Immersive Virtual Reality. IEEE Access 10: 25621–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rendever. 2022. MultiBrush Now Includes Oculus Avatars and AR Passthrough Support! Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7mnMfnsRc4k (accessed on 7 July 2023).

- Sanchez-Vives, Maria V., and Mel Slater. 2005. From presence to consciousness through virtual reality. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 6: 332–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sennett, Richard. 2008. The Craftsman, Kindle ed. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shales, Ezra. 2017. The Shape of Craft, Kindle ed. London: Reaktion Books. [Google Scholar]

- Shaviro, Steven. 2014. The Universe of Things: On Speculative Realism, Kindle ed. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sheriff, John K. 1989. The Fate of Meaning: Charles Peirce, Structuralism, and Literature. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Skarbez, Richard, Missie Smith, and Mary C. Whitton. 2021. Revisiting Milgram and Kishino’s Reality-Virtuality Continuum. Frontiers in Virtual Reality 2: 647997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, Mel. 2009. Place illusion and plausibility can lead to realistic behaviour in immersive virtual environments. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 364: 3549–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slater, Mel, and Sylvia Wilbur. 1997. A Framework for Immersive Virtual Environments (FIVE): Speculations on the Role of Presence in Virtual Environments. Presence: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments 6: 603–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, Mel, Martin Usoh, and Anthony Steed. 1994. Depth of Presence in Virtual Environments. Presence: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments 3: 130–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavroulia, Kalliopi Evangelia, Ignacio Aedo, Paloma Díaz, and Andreas Lanitis. 2021. Virtual-Reality Based Crisis Management Training for Teachers: An Overview of the VRTEACHER Project. Paper presented at International Symposium on Computers in Education (SIIE), Malaga, Spain, September 23–24; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiegler, Christian. 2021. The 360° Gaze: Immersions in Media, Society, and Culture, Kindle ed. Cambridge: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland, Ivan E. 1965. The Ultimate Display. Paper presented at the IFIP Congress, New York, NY, USA, May 24–29; pp. 506–8. [Google Scholar]

- Trichopoulos, Georgios, John Aliprantis, Markos Konstantakis, Konstantinos Michalakis, Phivos Mylonas, Yorghos Voutos, and George Caridakis. 2021. Augmented and personalized digital narratives for Cultural Heritage under a tangible interface. Paper presented at 16th International Workshop on Semantic and Social Media Adaptation & Personalization (SMAP), Corfu, Greece, November 4–5; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, Alfred North. 1967. Science and the Modern World. New York: The Free Press. First published 1925. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead, Alfred North. 1968. Modes of Thought. New York: The Free Press. First published 1938. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead, Alfred North. 1978. Process and Reality: An Essay in Cosmology. New York: The Free Press. First published 1929. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, Werner. 2013. Aesthetic Illusion. In Immersion and Distance: Aesthetic Illusion in Literature and Other Media. Edited by Werner Wolf, Walter Bernhart and Andreas Mahler. Amsterdam: Rodopi, pp. 1–63. [Google Scholar]

| Psi | PI | Ebi |

|---|---|---|

| Immersion | Presence | Engagement |

| Immediacy | Remediation | |

| Hypermediacy | ||

| What | Where When | Why How Who |

| Craft | Experience | Aesthetics | ||

| Object | Event | Relation | Power | |

| Firstness | Secondness | Thirdness |

|---|---|---|

| Possibility | Actuality | Rationality |

| Quality, sui generis | Facts, Events | General rules |

| Icon | Index | Symbol |

| App Title | Release Year | Total Number of Ratings | Average Rating out of 5 | Type of Making | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Vermillion | 2022 | 677 | 4.82 | Painting |

| 2 | PatchWorld–Multiplayer Music Maker | 2022 | 164 | 4.77 | Music creation |

| 3 | Kingspray Graffiti | 2019 | 2463 | 4.63 | Street art |

| 4 | StellarX | 2023 | 27 | 4.56 | Space creation |

| 5 | Tilt Brush | 2019 | 1013 | 4.5 | 3D painting |

| 6 | Tribe XR|DJ in Mixed Reality | 2019 | 845 | 4.49 | DJing |

| 7 | Mistika VR Connect | 2022 | 9 | 4.45 | VR stitching |

| 8 | First Touch for Meta Quest Touch Pro controllers | 2023 | 46 | 4.4 | Painting |

| 9 | Painting VR | 2022 | 425 | 4.38 | Painting |

| 10 | Color Space | 2020 | 511 | 4.37 | Coloring |

| 11 | SculptrVR | 2019 | 395 | 4.36 | Space building |

| 12 | ShapesXR | 2021 | 217 | 4.29 | 3D modeling |

| 13 | Virtuoso | 2022 | 255 | 4.27 | Music creation |

| 14 | MultiBrush | 2022 | 132 | 4.24 | 3D painting |

| 15 | VR Animation Player | 2019 | 426 | 4.24 | VR animation |

| 16 | Figmin XR | 2022 | 44 | 4.23 | MR creation |

| 17 | Zoe | 2022 | 48 | 4.12 | 3D scene creation |

| 18 | Gravity Sketch | 2019 | 1016 | 4.09 | 3D modeling |

| 19 | Flipside Studio | 2023 | 61 | 4.03 | VR animation |

| 20 | Arkio | 2022 | 147 | 3.94 | Space design |

| 21 | Electronauts | 2019 | 161 | 3.8 | Music creation |

| 22 | Let’s Create! Pottery VR | 2020 | 195 | 3.74 | Pottery making |

| 23 | Spatial | 2020 | 513 | 3.69 | World-building |

| 24 | Wooorld | 2022 | 173 | 3.56 | Trip-making |

| 25 | Home Design 3D VR | 2023 | 96 | 3.41 | Space design |

| 26 | YUR World | 2023 | 33 | 3.41 | Bodybuilding |

| 27 | Noda | 2021 | 162 | 3.38 | 3D ideation |

| 28 | Villa: Metaverse Terraforming Platform | 2021 | 1076 | 3.37 | World-building |

| 29 | RiBLA Studio | 2021 | 27 | 3.28 | 3D video |

| 30 | Prisms Math | 2023 | 56 | 3.12 | 3D learning |

| Object | Event | |

| HMD with sound background menu iconic tools | device control 360-degree exploration 3D objects manipulation | |

| Experience | ||

| Psi | PI | Ebi |

| Aesthetics | ||

| indexical interface life-size painting artwork inhabitation | general rules of 3D painting decentralizing narrative open-source network | |

| Relation | Power | |

| Categories | Subcategories | Content |

|---|---|---|

| Experience | Object |

|

| Event |

| |

| Aesthetics | Relation |

|

| Power |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, M. Virtual Craft: Experiences and Aesthetics of Immersive Making Culture. Humanities 2023, 12, 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/h12050100

Kim M. Virtual Craft: Experiences and Aesthetics of Immersive Making Culture. Humanities. 2023; 12(5):100. https://doi.org/10.3390/h12050100

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Minhyoung. 2023. "Virtual Craft: Experiences and Aesthetics of Immersive Making Culture" Humanities 12, no. 5: 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/h12050100

APA StyleKim, M. (2023). Virtual Craft: Experiences and Aesthetics of Immersive Making Culture. Humanities, 12(5), 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/h12050100