Poems about marriage and women that Lorine Niedecker wrote, revised, and sometimes published in the 1940s and 1950s provide a collective commentary on print advertising’s marketing campaigns and strategies. Often, these poems signal their critique by imitating advertising’s characteristic visual motifs, narrative registers, and textual as well as formatting patterns. The kinds of ads engaged have no literary pretenses,

1 but Niedecker’s poetry recognizes in these ads a kind of lyric heritage in their handling of gender and predication on (especially unmarried) women’s dread of social and romantic indifference both poetry and ads equate with death or a meaningless life. More overtly than the poems about single women, the marriage poems refute ads’ co-option of romantic commitment and domesticity to promote the quality and durability of brand names. These wry, perspicacious poems scrutinize the power and happiness that ads promise, sometimes turning advertising messages against themselves rather than condemning them.

2 In various ways, Niedecker’s poetics convey advertising’s role in reforming consciousness in multiple, sometimes layered, sometimes alternating, and even competing states of self-awareness. Niedecker’s condensed lyrics evaluate the complexity of voluntary, performative, and coercive scripts composing and flowing through cultural materials and stories about the self. However, they are not merely showing that ads were scripting consciousness in ways that normalize consumerism as the primary expression of identity, but that ads were reconstituting identity, for women, at least, as the experience of watching, judging, and talking about others and anticipating the ways one is watched, judged, and talked about.

Niedecker’s marriage poems, while tonally ambivalent, see modern marriage as directed by advertising’s imperatives. These poems seem to admire the cleverness of advertising rhetoric while testifying to its unsettling effects. “I rose from marsh mud” (

Niedecker 2002) connects lyric signatures, romance, marriage, and advertising through a bizarre scenario, readable as both humorous and horrible:

I rose from marsh mud,

algae, equisetum, willows,

sweet green, noisy

birds and frogs

to see her wed in the rich

rich silence of the church,

the little white slave girl

in her diamond fronds.

In aisle and arch

the satin secret collects.

United for life to serve

silver. Possessed.

Beginning with the conspicuous lyric “I”, a perspective Niedecker avoided (

Niedecker 2002, p. 433), the speaker evolves up from the muck and flora of asexual reproduction, into the clamor of animals known by sound more than sight, to witness the spectacle at the height of the evolutionary process, the public vow “to have and to hold” respected brand name items before they leave the church. In the closing stanza, the enjambed penultimate line leading into the dramatic finality of “Possessed”, isolated by periods, references the still-common wedding gift of a silver service, punning on interchangeable terms for national loyalty and eternal conjugal union with the near-homophone for “United”, “Oneida”, a famous silver company (

DuPlessis 1992, p. 104). Niedecker wrote and revised “I rose” through the late 1940s when popular magazines, such as

McCall’s, ran “an ad for Oneida’s Community silver-plated flatware” featuring a giant close-up of a couple kissing with the headline reading “Make it for keeps” (

Reichert 2003, p. 115), an imperative targeting the groom-to-be, who is assured of securing all the pleasures of long-term commitment through the acquisition of long-lasting luxuries. Niedecker’s allusion to Oneida is also a synecdoche for the dense field of ad images conflating matrimony with modern domestic life in which happiness is recognized as acquiring new products together.

3In the context of other poems interacting with print advertising, “I rose from marsh mud” more obviously identifies seductive advertising narratives than marriage itself (or capitalism generally) as the perceptual trap enslaving couples.

The final lines end the poem with attention lingering on ad campaigns that orient marriage in consumerism and consumerism in romantic longevity. “The clothesline post is set”, another poem from the 1940s, similarly ends with a reference to the brand name “All”, a laundry detergent, to punctuate the social performance of national values through consumer display. The weighty placement of the brand name references in the last lines attests to advertising’s centrality to these poems, a focus submerged in critical approaches to Niedecker’s work that emphasizes anti-capitalism or anti-materialism. Such emphasis on visual pop culture positions Niedecker among modernist poets who found in “commercially cultivated reading practices … models, strategies, and resources for their own writing” (

Chasar 2012, p. 23). They also underline Niedecker’s poetics as cultural readings carrying out the objectivist ambition to make visible the production of perspective itself. Niedecker’s poem tells the “satin secret” that advertising has rewritten the love language away from mutual admiration and solemn vows, replacing words with objects advertising has imbued with emotional qualities.

While certainly, “I rose from marsh mud” strips away the pretentions of a big, expensive church wedding to show the materialist motives for marriage beneath, it also pities the couple convinced by equation of expensive tableware and marital permanence. Ellen Lupton’s

Mechanical Brides: Women and the Machine from Home to Office (

Lupton 1993, pp. 3, 5, 7), the National Museum of Design exhibit and its accompanying publication, offers abundant examples of the correlation of matrimony and shiny appliances in post-WWII advertising: one features a satiny bride in a strapless gown and long veil sitting behind a gleaming Proctor toaster with “Beautiful” in large script beside her; “and makes beautiful toast!” appears in tiny print just beneath. In another, a comically affectionate, lavishly dressed bride smooches the chin of her new husband, a clean-cut soldier in dress uniform, next to a toaster bearing bread slices, all three beneath the caption, “Love, Honor … And ‘

Crispier’ Toast!” Another ad depicting a pair of newlyweds’ first kitchen reads “The One You’ve Always Wanted!” above the couple; the groom is in a top hat carrying the bride, who is carrying an enormous bouquet, both admiring the new General Electric refrigerator they have come home to. These ads and many others like them compound the message that successful marriages are secured and consummated with modern appliances bought by financially successful bachelors. Beautiful women get beautiful wedding gifts from their husbands; prosperous men marry and keep the women they most want by providing modern domestic housewares (

Figure 1).

Niedecker’s poems delight in mocking preposterous claims that spending guarantees romantic security, but under the humor lies alertness to the more chilling aspects of these readily embraced practices as custom. The “little white slave girl” and her groom, like those in the ads, exalt the abdication of much more than their romantic freedom as they embrace a “modern” marriage of debt and, subsequently, commit themselves to a stressful lifetime of constant efforts to stay ahead of losing everything. A 1953 poem beginning, “So you’re married, young man” (

Niedecker 2002, pp. 165–66) extends mock congratulations to the addressed for committing himself “to a woman’s rich fads—” and not to another person or to adulthood, as the status of marriage often confirms. The voice of the poem sounds like an announcement heading an advertisement and appears to address a general audience of young men misled by ads, such as Oneida’s, that spin marriage as a condition of shining permanence as unchanging as the wedding gifts. The first stanza blames the young man’s abandonment of purposive character directly on “woman and those ‘buy! buy!”/technicolor ads”, which define marriage by its consumerist imperatives and wives as constantly expecting from their spouses more items to improve the appearances of self and home. Shifting from second to third person, the poem’s voice becomes urgently prophetic and commercially theatrical:

She needs washers and dryers

she needs bodice uplift

she needs deep-well cookers

she needs power shift.

Countering advertising directed at men to win and satisfy a wife with diamonds and sparkling gadgets, the poem concludes with the unsettling prediction that the groom will ultimately commit suicide to escape the treadmill of empty, dehumanizing labor endured to meet illimitable social standards:

She’ll sue for divorce

he’ll blow out his brains,

the old work-horse

free at last of his reins.

The earlier versions of “I rose from marsh mud” and “So your married…” admit to the poems’ greater disgust for the fad-crazy brides, who drive their husbands into the grave with chronic nagging for clothes, washers, and freezers, a double standard Niedecker attributes to the “St. Louis Blues stream[ing] through [her] head” while working on the poem (

Niedecker 2002, pp. 410–11, 414–15). Most famously performed by Bessie Smith, “St. Louis Blues” (

Handy 1914) blames a “St. Louis woman wid her diamond rings” for a poor woman’s abandonment: “Tweren’t for powder an’ her store-bought hair/De man she love wouldn’t gone nowhere, nowhere”. Niedecker’s explanation that a song inspired the poem’s harsh tone reflects her poetry’s orientation in sound and is a good reminder that Niedecker’s experimentation with pop cultural materials is not an endorsement of pop culture’s perspectives. The effort to explain the poem’s unusual bite also indicates her awareness that the song’s attitude about a tarted-up rival and a gold-digging, faithless man is another version of ads’ consumerist tableaux.

Both poems, however, blame advertising for normalizing women’s (apparent) greed through persistent messages that they need new and more things. What is judged as a woman’s special weakness for shopping has been relentlessly reinforced by the advertising casting successful lives and promising futures in images of sleek appliances that glamorize servitude. These acrimonious marriage poems may seem to blame the brides as more directly collusive with capitalism’s agents, but the poems temper the sexist stereotypes with their emphasis on the conversion of marriage into an endless cycle of spending and wanting for both spouses. Moreover, concluding that these poems contribute to sexist stereotypes seems like a retroactive, misdirected interpretation. The poems target the consumerist identity advertising was, at the time, deftly composing rather than condoning an essentialist view of shallow, materialistic women. The repetition of “She needs” sounds to twenty-first-century ears like an accusation that the woman is an insatiable gold digger, but according to the ads, a modern woman responsible for the home’s economy exhibited discriminating intelligence by obtaining more efficient ways to meet household needs, such as cooking, doing the laundry, and cleaning. Niedecker’s poetry parodies that message of chronic needs and predicts its consequences. Wives are “possessed” by and are “slaves” to the threat of inadequacy, as are their husbands, and as both poems portend, their marriages are defined and doomed before they even get started.

According to Niedecker’s poems, the single working girl and the wistful spinster, alternatives to the possessed brides and wives, seem far better off, despite their tragic roles in advertising narratives. Niedecker’s marriage poems know what oblivious couples featured in and influenced by the chirpy ads do not. Poems about single women gauge very different, fear-based advertising tactics. Although romantic intimacy promising, securing, and maintaining marriage stands as the primary goal of all purchasing conduct, the time of vulnerability to rejection is extended well beyond young womanhood—from early adolescence when social reputation is established to prime matrimonial age and reaching into years after marriage. A woman’s relationships with friends, suitors, and even children remain threatened by supposed lapses in self-awareness that guidance found in advertising can prevent.

In ways that expose the images of women under construction in the social mindset, Niedecker’s poems borrow advertising’s thumbnail images and spatial arrangements. These poems take up and send up ads’ stock scenarios while inspecting their repurposing of lyric compression, models of consciousness, and gender dynamics. These poems teeter on the paradox of women at once inscribed in and by advertising scripts, at once conscious of their performances, and losing awareness of a sense of self prior to them. These poems elaborate on what Bonnie Roy calls Niedecker’s “technologies of vision” (

Roy 2015, p. 478) that, in these poems, dramatize the way advertising instructs women to look at themselves and each other. The poems address the roles into which women are cast, but they also register the general public’s recruitment as an audience to enforce consumer habits.

An unpublished poem, revised into the mid-1950s

4, beginning “The elegant office girl” (

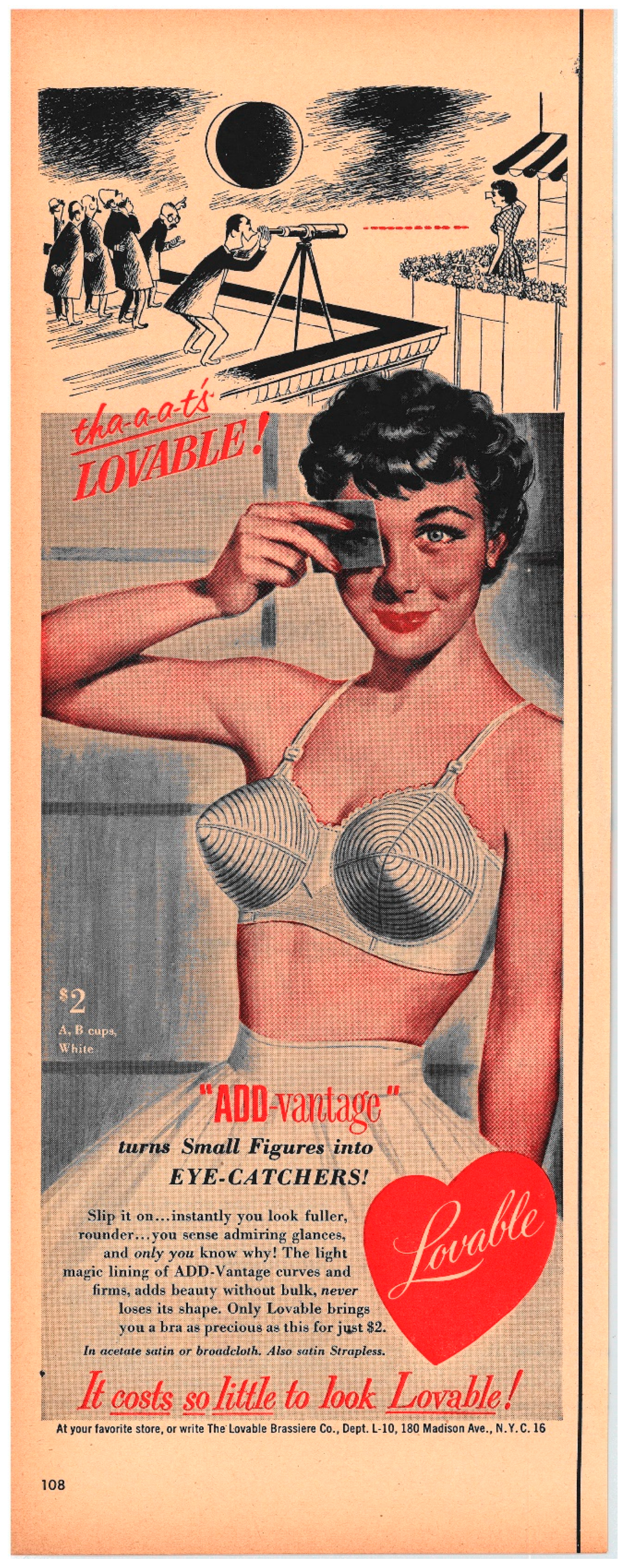

Niedecker 2002, p. 136), dramatizes the bind of young women encouraged to model modern independence by working for their own money and displaying smart consumerism. Establishing in the first two stanzas the office girl’s achievement of elegance in terms of underwear (“armature” in French versions, “shapewear” in American), the poem questions the legitimacy of social power sold to young working women and implies, instead, the degrading predicament they are lured into through fashion and the fashionably sexist office place. The “bodice uplift” demanded by the wife of Niedecker’s “married young man” was likely pitched as a way to maintain her husband’s interest as age and gravity gained influence. In this poem, “bodice” is replaced by the more explicit “breast” to reference ads guaranteeing transformation of even the “small-busted” into “eye-catching” sex symbols, which like shiny kitchen instruments, combine efficiency with ornamentation:

The elegant office girl

is power-rigged.

She carries her nylon hard-pointed

breast uplift

like parachutes

half-pulled.

The third-person perspective at first takes up the voice of advertising’s confidential advisor, who observes the subject for the erudition of ordinary working women striving to be elegant and to alert the office men who will enforce the standards. These opening stanzas borrow magazine ads’ stylized images of the young everywoman rising on stiletto heels and lifted by bullet-brassiered confidence, a strong, machine-like emblem of industry and sexuality. Roy’s discussion of Niedecker’s prose piece titled “The Evening’s Automobiles”, also about an office girl, notes similar confusion of “woman and machine” and its heightened gender implications: “The annexation of the human being into the object’s field allows the male boss to touch the woman as though she is his machine” (

Roy 2015, p. 484). As the poem’s pun implies, her modern appearance is rigged against her, part of a system extending male control. Almost certainly, the young woman typified was hired for her looks as much as for her typing and reception skills; she is an accessory for the men for whom she works, and the prettier and more fashionably dressed she is, the more compelling her boss’s appearance of success.

Lupton (

1993, p. 48) remarks on the function of machinery (such as rigging) to enable and naturalize “male decision-making and female service” in the modern business office: “[T]he very notion of ‘secretary’ is cloaked in sexual innuendo: the occupation has no absolute definition … but rather is identified tacitly by its gender (female) and its machines (typewriters or telephones)”. Niedecker’s “office girl” emphasizes the infantilization of the employee and the vagueness of the work. The economic ascension and social uplift her employment is supposed to grant are a ruse: her professional demeanor and her lingerie-manipulated body have been sold to her to attract discerning male attention that will bring social and financial security in courtship and marriage, a speciously safe landing anticipated by the “half-pulled” parachutes of nylon landing gear.

By mid-century, a working girl would not have to open a slick magazine to find illustrations of female desirability; she could find them on her boss’s desk or in the mail she sorted through at work. In

The Erotic History of Advertising (

Reichert 2003, pp. 107–8), Tom Reichert details the marketing practices popularized by the late thirties and continued for decades in the U.S., of distributing business calendars, magnets, and direct-mail postcards featuring nude or clothing-compromised pictures and drawings of women. These items, some so ribald as to make Victoria’s Secret ads seem tasteful by comparison, intended to create, in clients’ minds, the happy association of sexual gratification and products as unlikely as varnish, stainless steel, and bolts. Although some of these desk calendars and other keepsake ads pretended reverence for the beauty of the female body, many indulge in verbally or visually suggestive jokes at women having their bottoms exposed by errant vacuum cleaners or machinery—and the women enjoying it. As Reichert notes, the actual calendar portions were often tiny compared with the pictures, but this disproportion speaks to differences between men’s and women’s relationships to the calendar month. To the men of the office, the girly calendar represented their (presumed) common desires and domination of the business realm. For the women—the office girls—these tokens were reminders that they, too, should be happy to be looked at (

Figure 2), but the presence of those racy calendars also highlights the precarious status of the office girl, who must appear sexually desirable and accessible enough to draw interest from gainfully employed men, but who must also carry herself as modern and independent lest she come off as too eager for their attention. A woman’s mindfulness of the calendar itself is essential for either accomplishment, lest she embarrass herself by staining, smelling, or deflating unexpectedly, so the irony of images of sexual availability posted above the means by which women anticipate, avoid, and chart sexuality could not be lost on many of them. Should they endanger their social and romantic chances by forgetting their bodies’ constant need of supervision and maintenance, however, the magazines they read at home would be sure to set them straight.

Unlike the brides cheerfully colluding with their own enslavement in the marriage poems, Niedecker’s office girl, who “carries” the weight of expectations to appear exceptional, seems a weary, reluctant victim, swindled by consumerist portrayals of personal empowerment: the whole point of her “hard-pointed/breast” is difficult to bear. As

Roland Marchand (

1985, p. 215) concludes, advertising’s vision of modern life “inspired individuals to play roles or create traits that would distinguish them from the mass and make others think of them as ‘somebodies.’” This poem is more openly sympathetic to the office girl’s quandary than the marriage poems are to their brides’; the word “carries” implies the girl’s professional achievements and purchases merely add to her traditional burdens, such as childbearing, husbands’ surnames, and fetching coffee, rather than free her to pursue individuality in personally satisfying ways. The roles and traits of “somebodies” are consumerist expressions, such as tastes in clothes or laundry soap preferences

5, recognizable to the public eye.

The first stanzas imitate the ogling and assessment that ads promote, but at midpoint, the poem changes tone and message drastically. This shift in location and perspective parallels both ad design divided into foreground and background (as in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3) and the doubling address of love lyrics that similarly position the reader, speaker, and spoken of. The opening stanzas comment on the deceptive ways women are convinced they can achieve real power and importance by becoming what they see in ads, but the slang terms and crass remark about the girl’s breasts sound at first like the poem thinks the joke is on her. However, the poem’s miniature portrait of a young woman who thinks a bullet bra elevates her class status turns into a more sober, sympathetic look at the consequences of replacing personality with “lifestyle”. Along with the descent of disarmed breasts, “collapse occurs” in the final stanza, which makes up half the poem’s twelve lines and relocates the office girl (presumably) to her home, where she should be more comfortable, less of an object when the armor meeting social expectations has come off. Instead, half-pulled parachutes predict the girl’s own deflation among the detritus of merchandise:

At night collapse occurs

among new flowered rugs

replacing last year’s plain,

muskrat stole,

parakeets

and deep-freeze pie.

While “collapse” implies the dropping of pretenses or emotional guardedness, the office girl completely disappears among the items listed in these final lines without so much as a possessive pronoun to mark her ownership of or connection with her home. Trendy décor and fashionable accessories said to give home and owner “personality” not only distract the collapsible girl from workaday frustration but also replace her as the primary occupant, just as the new rug replaces last year’s outdated version. From the floors she stands on to the low-maintenance, colorful pet, whose cage within the house manifests its owner’s capture and display, to the frozen pie fraught with accusations of domestic inadequacy (or readiness for guests that never drop by)

6, her purchases testify to the elegant office girl’s adherence to public scripts of economic and social liberty through which modern individuality are produced. While her clothes and furnishings convey current understandings of elegance, they do not seem to have anything to do with her own taste or pleasure. What she wants, why she wants it, and who she is supposed to be are impressed upon her and the people judging her through the images saturating everyday routines and through the consumerist response to these pressures to dispose of, replace, or preserve for anticipated needs.

The vanishing of the girl who models socio-economic ascension and personal freedom by day converts the poem into a lament and a thwarted lyrical rescue. Her potential uplift is actually a myth energizing the sexist status quo, but the visual narratives circulating everywhere in advertising culture foreclose alternatives: young women can be vibrantly independent future brides, little white slave girls, or disappear into the furniture—and not only in the public, consumerist mind. Discussing Niedecker’s short story “Switchboard Girl”,

Martinez and Sanchez-Pardo (

2019, p. 45) posit that Niedecker is acutely aware of the “mental models of the self projected into storyworlds” like those mini-stories of personal happiness narrated and narrowed in advertising. As a visually disabled working woman herself, Martinez and Sanchez-Pardo argue, Niedecker “portray[s] … the grim social tribulations of post-war working women” in order to engage readers’ sympathy with them. “The elegant office girl” exploits the tricky territory of compressed experimental poetics in order to show not just the unglamorous working conditions women face, but also to expose the rendering of idealized visibility as an insidious excavation of selfhood. The impersonality of the office girl’s home is suggested by the withdrawal of direct references to her: “collapse occurs”, meaning the girls’ exhaustion and deflation of the simile’s parachutes, but signs of personhood, including the poem’s speaker and the girl’s body, are gone, as if crushed beneath the uplifted, then dropped, weight of imagery.

As the poem’s concluding list of replaceable objects indicates, the constantly reinforced sense of performing for a critical audience has replaced the girl’s interiority. Unless someone sees and admires her, she is not really there, even to herself. Unlike the wedding poems’ emphasis on personal relationships, this poem reveals the intrusion of advertising strategies on self-perception, “the mental models of the self, projected into storyworlds” (

Martinez and Sanchez-Pardo 2019, p. 45). The storyworlds of advertising, which were becoming more and more openly cautionary tales, extended to the shaping and narrating of consciousness. Advertising discourses heightening the experience of self as an observed social presence seeking to express personal specialness from an authentic, inner voice strangely resembles the lyric’s essential features, such as aesthetic and emotional sensitivity evinced in powerful but unspoken desires for a woman. Niedecker’s office girl poem begins as an imitation and correction of advertising messages conflating individuality and unique attractiveness, but ends as a recognition of the ways advertising has already adapted literary techniques of giving words to experiences of self and textual forms to private fears and desires. This recognition, however, is not that the gender rubrics of the lyric have been tainted by consumerist importation, but that they have been reproduced and irreversibly disseminated to the point of cultural saturation.

That her poems responding to advertising register the similarities between lyric operations and advertising’s forms of addressing (and thus constituting) consumers seems inevitable. Niedecker’s affinity with radio and her view of herself as a lifelong eavesdropper inform the sound-oriented, sonically attentive poetics she practiced. A 1946 letter to a friend asks that her poet identity “be kept mum—folks might put up a wall if they knew […] and I have to be among ‘em to hear ‘em talk so I can write some more” (

Knox 1987, p. 20). This request has often seemed to express Niedecker’s uneasiness about her differences from people in her community, who would think her peculiar if they found out about her vocation and connections with famous poet-critics. These ad-inspired poems about the intricate scripting of self-consciousness and concentric circles of social scrutiny recast the request as a broader concern about losing access to actual women talking about and to other women, including herself, as well as the expectation that, were her poems read, they would be disturbing, not mystifying.

Houglum (

2009, p. 222)

7 argues, “Niedecker’s writing participates in an early and mid-twentieth-century climate in which changing concepts of sound and voice in poetic texts resonate with and against modern media and technological shifts”. The advertising-conditioned general public (including citizens of Fort Atkinson) is part of the “modern media” responding to and reiterating “technological shifts”.

The simultaneity of self-consciousness and layers of public surveillance Niedecker’s lonely women poems convey were modeled, most obviously, in the many magazine ads presented as comic strips, a format frequently used in ads that targeted women consumers. These ads, like lyric poems, present moments in which the private thoughts of one woman or a conversation between two women about another are stated for an overhearing reader, sometimes with a mediating speaker who engages directly with the implicit reader/listener through captions above the comic frames and speech bubbles. As Rachel Blau DuPlessis has pointed out, conventions of the lyric present a similar scene, in which a knowing voice “speak[s] as if overheard in front of an unseen but postulated, loosely male ‘us’ about a (Beloved) ‘she’ “(

DuPlessis 1994, p. 71). In ads, though, the woman spoken about is not beloved, which is the problem, and the male affection she is missing is caused by a lack of self-awareness that only advertising (or poetry) can teach her. Marchand’s summary of modern advertising’s distinctive character likewise resembles modernist exclusivity that endorses only poetry disdainful of a large readership in favor of selective appreciation: “Thus in content and technique, American advertisements can be said to have become ‘modern’ precisely to the extent to which they transcended or denied their essential economic nature as mass communications and achieved subjective qualities and ‘personal’ tone” (

Marchand 1985, p. 9). Similarly, modernist discourses “demarcating cultural boundary lines between refined and mass/popular culture” (

Chasar 2012, p. 10) imagined an elite (elegant?) readership who stood out among the working masses unable to understand intellectual poetry, a “factually problematic” (ibid., p. 11) but still influential vision. The competing goals to attract and mold consciousness while denying any intention (or ability) to appeal to consumers seem to be characteristic properties of modern textuality.

Figure 3.

This (

Pictorial Review 1934, p. 29) Lux soap ad is one of many variations of comic-formatted narratives typical of products (Listerine is another) sold to cure bodily odors that ran in magazines for decades.

Figure 3.

This (

Pictorial Review 1934, p. 29) Lux soap ad is one of many variations of comic-formatted narratives typical of products (Listerine is another) sold to cure bodily odors that ran in magazines for decades.

Fascinating too, are the ad’s attendant instructions about what can and cannot be said aloud and to whom: “Men can’t talk about it”, the sub-heading to Jean’s story reads, but women apparently can talk about it with one another, just not to the woman with the problem. Importantly, this version of the advertising motif differs in permitting anyone else to name or to correct the lonely woman’s problem. More often, the voice of the product says through the various captions what the woman needs to know and, in diagnosing for the public’s education her easily preventable despair, consequently scares other women away from committing similar crimes of reprehensible fatuousness: “You never have it?” another ad asks rhetorically (“it” meaning “body odor”), then answers”,--

what colossal conceit!” (qtd. in

Reichert 2003, p. 123). Such ads sometimes conveyed kinder messages of democratic physicality, a “…secularized version of the traditional Christian assurances of ultimate human equality” (

Marchand 1985, p. 222). Disembodied, God-like voices, such as those of the floating, unattributed captions, speak about the bodies of others and demand humility from listeners in ways that “might be considered a secular translation of the idea that God ‘sends rain on the just and on the unjust’” (

Marchand 1985, p. 222). Niedecker’s poems featuring women or presumably female speakers

8 illustrate the heightened awareness and internal clamor the advertising-saturated environment cultivated that taught women to see themselves and others as characters in these marketing plays, whether radio scripts, comic strips, or annotated tableaux.

9Niedecker’s poems featuring older women or speakers tend to play on advertising’s appropriation of the lyric tradition’s darker side: the fear of mortality the physical body’s flaws foretell. Fear tactics spreading insecurity became advertising staples of what we would now call “health and hygiene” products. Marchand explains that copywriters worked to strike a golden mean between arousing insecurity and providing too much evidence that might “generate counter-reasons” through “dramatic episodes of social failures and accusing judgments” capable of “jolt[ing] the potential consumer into a new consciousness” (

Marchand 1985, pp. 13–14). According to such ad campaigns run through the 1930s and into the 1950s, an unmarried woman creeping “gradually toward that tragic thirty-mark” (qtd. in

Reichert 2003, p. 123) and beyond had reason to suspect she suffered from halitosis, body odor, or both. The “bridesmaid but never the bride [commercial] theme” often pictured young women weeping with resentment over attending yet another wedding or puzzling over a steady beau’s recent disappearance. Some ads pictured women “saved” from their solitary fate through fortuitous eavesdropping, a standard convention of melodramas, such as 1937’s

Stella Dallas. In ads by Listerine, Lux, and Lifebuoy, socially isolated women are depicted sometimes sympathetically, sometimes contemptuously, as in the Listerine ad headed, “ISN’T SHE DUMB?” Whatever emotional response invited from the reader, however, the featured women have failed, due to arrogance or ignorance, to attend scrupulously enough to their bodily emissions—the recurring implication throughout these iterations is that the women ought to know why they have no husband, boyfriend, or friends. They do not understand the cause of their loneliness, and the cause, really their failure of self-consciousness, puts them in such a friendless state that the smell-eliminating products and the informational ads describing them replace these sad women’s friends. The voices of these advertisements seem laughably direct, not because the messages are unfamiliar to us, but because they have been repackaged as subtext in our more sophisticated times. What is stated directly there, though, says what peers, male or female, can never say to the offending woman, as in the Lux ad showcasing the clever pun, “GAGGED—when a word could save their romance”. In this example, Jean secretly hears other girls worrying over Jean’s loss of Fred’s attention because of her inadequately laundered underthings, a very specific problem the other girls identify, presumably, by either having smelled Jean’s underthings themselves or having recognized preemptively similar “risks” lurking in their own underwear (

Figure 3).

One of Niedecker’s few titled poems, “Woman with Umbrella”, published in

Accent in 1953

10, opens up the cumulative vision of the unattached woman of any age that advertising discourses had scripted over several decades. Unlike the office girl eclipsed by the possessions collected to establish her individuality, this lonely woman is conscious of her public image as a walking cautionary tale among crowds of judgmental observers. Advertising “tableaux often suggested that external appearance was the best index of underlying character” (

Marchand 1985, p. 210), a message reiterating centuries of lyric poetry that dwells on physical beauty as the primary index of female lovability. Both traditional poetry and print ads enforced the expectation that women should be scrutinized by men and women alike and that women should strive to see themselves as ornaments in need of constant refinement to be worthy of others’ approval. One magazine caption asks, “Suppose you could follow yourself up the street…What would you see?” (qtd. in

Marchand 1985, p. 217), echoing, perhaps deliberately, the conclusion of Robert Burns’ “To a Louse” (

Burns 1786) in which the conceited well-dressed girl in church (who ignores the speaker) does not know she has lice. To see oneself as others see us (“Oh wad some Pow’r the giftie gie us/

To see oursels as other see us/It wad frae monie a blunder free us”) is a “gift” only the power of advertising could offer. In the vein of the lyric tradition, advertising provided the missing discourses for intimate, confidential matters, even menstruation (

Marchand 1985, p. 22), to solve the crisis of self-consciousness its admonishments generated.

Niedecker’s “Woman with Umbrella” (

Niedecker 2002, p. 115) presents an autonomous, practical woman experiencing herself as a narrative of failure: she hears herself being perceived as lonely because she fails to stand out in the crowd. Like the girls and women in ads whose inability to keep a boyfriend seems also to preempt friendships, she is marked by those who avoid running into her and hears the voiceover judgments in her mind as she walks efficiently to her destination:

Lonely woman, not prompted

by freshness from the sky

to run with friends and laugh it off,

arrives unsparkling but dry—

Packed into the first line is the basic logic outlined in the advertisements described above: the woman uninstructed or resistant to available carpe diem scripts (prompts) to help her act fun-loving is, by default, lonely. This assumption further suggests that any woman alone is alone involuntarily and that this condition must be reversed lest her singlehood advance to spinsterhood. Thus, the simple, commonsense decision to carry an umbrella can be interpreted by the consumer-conditioned public eye as evidence of her friendless state and her distance from her “natural” girlish mood of gaiety and spontaneity. The poem imitates the jingle-like rhyme scheme (sky/dry, street/meet) favored by advertising, but unusual for Niedecker, further signaling advertising’s scripts. The poem sides with the woman, however, in the admiring conclusion of the first quatrain where she “arrives” in dignified equanimity, “unsparkling but dry” and in the second stanza’s shift from a third-person description of her visible self to a lyric interiority of what she feels and knows.

Here, the poem resists the consuming narratives that swallow up the office girl while showing their dominance. The closing restores the self-awareness that consumer discourses deny an unaccompanied, serious woman by undermining the equation of female solitude with feeblemindedness and weakness:

she’s felt the prongs of her own advance

thru the crowded street

knows that lonely

she is dangerous to meet.

From six to sixty, girls and women are trained—not inaccurately—to see themselves as endangered any time they are alone, especially when they are alone on the street. When they are also lonely, they are vulnerable both to violence and to charming con-artists. This ostensibly lonely woman is the one who is dangerous because she seems to have defied consumerist bullying to improve and “advance” by behaving in ways to garner social connections. Niedecker’s stylistic drive to condense and revise every poem down to its essential words gives added importance to redundancy: “the prongs of her own advance” calls for meditation on its use of the intensifier “own”. What pokes the crowds around her is her self-possession, that she advances under her own power, keeping herself dry in the process and converting social rejection into a self-governing space. Although misperceived as starved for attention, the woman with the umbrella has created a roof of her own in a culture crowded with confusions of self-attenuation and self-control. This poem joins “Horse, hello” and “Woman in middle life” (

Niedecker 2002, pp. 162–63; see

Savage 2010) in affirming the social exile threatened by advertising culture as not a punishment but a liberating hermitage. That freedom from the suffocation of social relevance, however, was and continues to be perceived as womanly failings impinging on literary accomplishments.

“Woman with Umbrella” and other poems Niedecker wrote that inspect consumerist discourses intensifying traditional attitudes about women seem, to me, to be also a way of countering—and predicting—the contempt and pity descending on the few women poets recognized by American literary history. As a woman conspicuously unpartnered, living in ways easily categorized as eccentric, remote, and isolated compared with the urban-centric poets with whom she is foremost associated, Niedecker could not help but to anticipate the kinds of scripts she would be fitted to. Her rudimentary resemblances to Emily Dickinson had already been documented in William Carlos Williams’ laudatory description of her as “the Emily Dickinson of [her] time” (

Roub 1996, p. 79), and she would surely be aware of the dirty hand dealt Edna St. Vincent Millay, who died in 1950 still indicted for personal and literary immaturity. Although Millay lived more like a bachelor than an isolated poetess, she was, by mid-century, maligned by the then-nascent New Critics for her hyper-feminine, unseemly lifestyle, surely the result of deep loneliness and for her derivative and reactionary poetry said to court uneducated popular appetites. By the 1950s, Dickinson’s poetry was included in various anthologies and established a place in American literature, but the poet was treated in similarly infantilizing ways by powerful critics, such as Richard Chase and John Crowe Ransom. In Chase’s biography of Dickinson, published in 1951, he emphasizes Dickinson’s supposed peculiarities and ties the smallness of her poems to her career choice of “perpetual childhood” (qtd. in

Rich 1979, p. 166). Ransom, who famously said of Millay, “Miss Millay is rarely and barely very intellectual”, approached Dickinson with a similar mixture of patronizing contempt (qtd. in

Clark 1991, p. 144). Referring to Dickinson as “a little home-keeping person” (

Rich 1979, p. 166) whose poetic form reflected professional ignorance rather than purposeful intelligence, Ransom insisted that Dickinson’s poems required editorial standardization before publishing. Niedecker read voraciously and would have recognized in these instances of critical arrogance her own outward similarities to these other poets in the eyes of the American literary establishment. Niedecker’s lonely women testify to her alertness to the sexist assumptions of consumer culture, but they also predict the ways literary history would likely reduce her own lifelong commitment to poetry, her heroic efforts to remain independent, and her patient invention of a poetic simplicity capable of harnessing correspondences among disparate points of social meaning. Niedecker’s poems routinely expose the flexibility and stamina of bigotry, and I think these poems about women extend compassionate, knowing tributes to women poets who chose, like Niedecker chose, to live the way that best served their art. Like Niedecker, her predecessors did so suspecting that the dedication to their own genius would probably be rewritten into yet another script about a sad girl who could not get married, and so she turned to writing poems for company.