Abstract

The Xtabay is a legendary Mayan forest entity associated with the sacred ceiba tree. The prose-poem by native ethnologist Antonio Mediz Bolio, translated here, represents the version of her story that he knew a century ago, where she appears as a temptress who lures young men under the tree to become her slaves. Behind the romantic sensibility that pervades this poem may lurk the combined shadow of two avatars, an ancient goddess of the hunt and a hybrid bird-woman who regards as prey those who threaten her forest or the creatures that call it their home.

1. Introduction

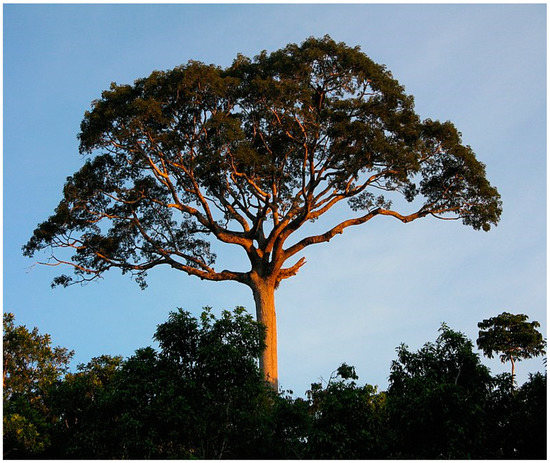

The Xtabay is an apparition in a pale gown that appears to those that enter the forest alone at night. Although she now takes multiple forms and has several functions, the Xtabay probably first emerged as a personification of the ceiba, the great kapok tree. She inhabits her tree much as the European dryad inhabits the oak whose name dryos she bears.1 The Xtabay’s ceiba (Ceiba pentandra), sacred to the Maya, is among the world’s tallest trees, rising above the forest canopy on a trunk with thorny spines that forbid climbers (see Figure 1). Its above-ground buttress roots can rise higher than a tall person’s head, inviting access within the tree like a portal to an underground dwelling. By association, the spirit of this sacred, thorny tree must likewise be mysterious and ambiguous. Sometimes part bird or other creature, whatever form she takes, in whatever context, the Xtabay’s chief characteristic is her alluring, dangerous female beauty.

Beware. When you walk alone along the road in the moonlight and under the stars, the east wind will breathe on you and make you feel as though you are flowering like a tree in the rain. Then you will be young as if you had youth three times over, and the Xtabay, who has been watching you, will show herself to you.(Mediz Bolio 1922, p. 189, translated)

Figure 1.

Photo by Klaus Schönitzer, “Ein Lupuna-Baum (Ceiba pentandra), das Wahrzeichen der Forschungsstation Panguana.” 2008. Available under a GNU Free Documentation License.

The word Xtabay (or Ixtabai, X’tabay) is pronounced “[i]Sh-tabai”, with the slight hint of an initial “i” and rhyming with “oh my”; the prefix ix- indicates female gender.2 The Xtabay is sometimes mistakenly associated with the more famous Llorona, the Weeping Woman who betokens death to those who hear her mourn for her children that she has drowned. But the Xtabay does not weep, she waits. She awaits the young man who must draw near before he notices her, enfolded by the above-ground roots of her tree and combing her long, glossy hair. Some say that she lures forest hunters to their death beneath the tree, much as the sirens of old lured sailors to their death in the sea. Today her victims tend to be husbands who go out alone at night, or drunkards; she is a nemesis punishing male infidelity and insobriety. Among the numerous versions of her legend, most fit into one of two basic types, a meeting and a backstory about the origin of the Xtabay. That derivative secondary tale, popular on the internet, is a moral fable about two women that has more to do with European fairytale and perhaps the effects of deforestation than with the original Xtabay, because in it she is not even a tree spirit.3 It is summarized in the commentary following the translation. This essay gives pride of place to Antonio Mediz Bolio’s haunting prose poem in the belief that his representation of the spirit-woman of the ceiba tree taps an earlier, hence more “authentic”, version of the Xtabay than other variants, but her eerie otherworld charm continues to inspire and renew her legend. Discussion of that legend’s ancient sources and modern expressions follows the poem.

Born in Mérida, Yucatán, in 1884 (d. 1957), the vastly talented poet, politician and educator Antonio Mediz Bolio was dedicated to preserving the culture of his people.4 A native speaker of Mayan, in 1922 he published his famous book of Mayan legends, La tierra del faisán y del venado (‘The Land of the Pheasant and the Deer’, i.e., Yucatán). The book fueled interest in indigenous cultures throughout Latin America as well as spurring further research into Mayan customs and tales. Mediz Bolio told Alfonso Reyes, the author of the book’s prologue, “I have thought the book in Mayan and I have written it in Spanish”, further explaining that he has attempted to evoke the voice of a native storyteller (Mediz Bolio 1922, p. iv).

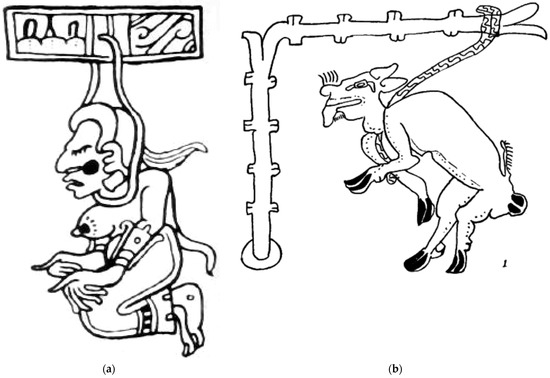

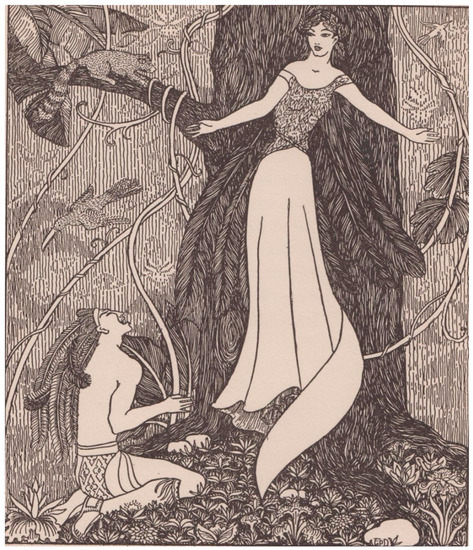

Part 1 of this essay translates his Xtabay legend from La tierra, with the original Spanish text following the translation (Mediz Bolio 1922, pp. 186–93). Along with the two-women story purporting to explain the origin of the Xtabay, Part 2 contains accounts of recent Xtabay sightings, some creative works, and scholarship about her possible more ancient origins. It concludes with two illustrations: a drawing from a Maya codex that some identify with a “goddess” entity named Ixtab (Figure 2), placing the story in a native context, and a modern illustration that presents the Xtabay as a “jungle witch” (Figure 3); the fairytale nature of this picture echoes Mediz Bolío’s inability to escape the influence of a European-styled education. Nevertheless, as he argues, his storyline and the rhythms of his tale are Mayan. This translation attempts to retain that chant-like quality.

Figure 2.

(a) Glyph from the Dresden Codex thought by many to represent Ixtab (Rope Woman) as a suicide goddess, reinterpreted here as Ixtab as a hunt goddess wearing a rope snare as a symbol of her method of entrapment. Redrawn by Melissa X. Stevens from an image by William Gates (de Landa and Gates [1937] 2011, p. 73) and used by permission; (b) Glyph, “Yucatan deer caught in a snare, Tro-Cortesianus 48b” (Tozzer and Allen 1910). In the Public Domain. (Tro-Cortesianus is now called the Madrid Codex.).

Figure 3.

Frances Purnell Dehlsen’s illustration of the “Jungle Witch” (the Xtabay) from Idella Purnell’s (1931, p. 29). In the Public Domain.

2. The Xtabay by Antonio Mediz Bolío, Translated

Listen, traveler of Mayab, and learn of ancient things …

If you are fresh and young, and your heart is keen and your face is happy, and you can stop a deer in its tracks with your bare arms …

If you have already known the sweet intoxication of the vanilla smell in a woman’s hair, and you know how to press her mouth between your lips to taste her juice, like that of a ripe plum …

If you do not know how to fasten your feet to the ground when a pretty woman pauses to look at you and smile; if you have the energy to fall in love seven times in a single day and don’t have what it takes to resist love even once.

Poor youth, alas for you, when the Xtabay discovers the road that you’re traveling on, returning from the fiesta, or from looking for her—for her who is deepest within your own soul—alas for you! The Xtabay is the woman you desire in all women, and whom you have found in no woman yet.

Alas for you, if she appears before you one night! You will discover, if you see her, that she is more beautiful than you ever imagined a woman could be. For you have imagined that she is like a ray of moonlight falling through leaves, but the Xtabay is more than this. You have thought of her as a flower opening at dawn, wet with the tears of night and fragrant as incense burned before the gods, but the Xtabay is more than this.

You have perhaps dreamed that she has eyes full of stars and that her face is radiant like a cloud reflecting the sun, but she is much more than this.

Alas for you, when you hear her call your name and you tremble, remembering the power of your sweetheart’s bewitching voice and her honey-sweet lips, for then your thoughts are hot as a burning coal, and you say to yourself, “It is she, who has come out ahead of me on the road.” But pray to your lucky star that she whom you fear and desire never places herself before your eyes, for the virgin who now consumes your nights and days with thoughts of love would then be less to you than a dry leaf that the wind of your memory blows to dust. You will never again want even to hear about her, for when you have seen the Xtabay, it will seem to you that you are knowing life for the first time. Alas for you!

Beware. When you walk alone along the road in the moonlight and under the stars, the east wind will breathe on you and make you feel as though you are flowering like a tree in the rain. Then you will be young as if you had youth three times over, and the Xtabay, who has been watching you, will show herself to you.

You will see her clad all in white and hovering above the ground. You will see her long, shining black hair, and you will see her hands braiding and combing her hair with a leaf of the breadnut tree, and you will see her feet like two little birds flying close to the earth.

Unlucky man! You will feel her eyes pierce you like two arrows that you cannot pluck loose. They will be like the spears for hunting monkeys, with backward-curving barbs that once sunk in can never come out—unlucky for you, because you’ll feel neither fear nor pain, but only a joyful madness, and this is because you have seen your desire and seeing it has torn open your heart!

She has shown herself to you in the air, perhaps alighting on a great boulder or balanced on a corn-yard fence post, and now she goes before you as if leading you onward.

Ah, how ready you are to run after her as she beckons you with her hand and smiles at you with her mouth, sinking her piercing eyes into your innermost being. What whispering comes from her lips, so soft that you are uncertain whether it is a voice or a kiss. What shining from her body, so that you do not know whether it is lit up from within or by a flash of flame.

She vanishes behind a tree, and when you pause to recover yourself, before your eyes she appears again, beside you. She flees like a breath and you pursue her like a sigh.

It is a mad course you follow, mad with lovesickness! But if you offer your life to touch her one time, seventy times you will give it for her. Alas for you!

She escapes from you like a hummingbird and you follow her like the thrust of a dart. Where is she leading you? Where are you going?

Ah, you need not take notice of where you are, for you are not coming back. Never has anyone returned who has followed the Xtabay! And all those who see her, follow her. Where are they now, that they do not return? Nobody knows.

There are those who have armed themselves with courage as with a cuirass of tanned leather, and have gone in the most silent hour of a night of full moon to the broad trunk of a ceiba tree where the Xtabay lives, and they cast spells to call her forth for questioning. But she does not come to those who call her thus, or in any other way. She crosses the path of the man who walks alone and is arrogant and thinks of love. Because of this, he is forced to follow her irredeemably. She does not call to someone she knows will not follow her.

In the depths of the earth, where the enchanted ceiba trees reach their roots, are hundreds of thousands of captive young men that have been taken by the Xtabay. If only they could remember that the world exists, perhaps they would return to tell us things that nobody knows. But no one will know, because those men will never return.

May you ever be free from the spells of the Xtabay, lovelorn happy youth, for you do not have the strength to resist her. If I could give you a talisman, I would do so, and indeed one exists, but I cannot give it to you.

For he alone has it who managed to reach the Xtabay and snatch out a lock of her hair. Then she followed him like a slave, and he became her master, needing only to command and she obeyed. Who is this man? Where is he?

Search for him, if you have faith, and find him if you have the strength.

But misfortune is yours if you happen to meet on your path her who will escape like smoke and whom you will pursue like the wind—the Xtabay who, when she takes you captive, seems to come out from the trunk of a ceiba tree, and who truly appears from nowhere but the depths of your own heart.

Original Text

Si tienes los años frescos y el corazón animoso y la cara alegre, y puedes detener un venado a la carrera entre tus brazos…

Si ya has conocido lo dulce de embriagarte con el olor de vainilla que hay en el cabello de las mujeres, y si sabes apretar su boca entre tus labios para gustar su jugo, como el de una ciruela madura…

Si no sabes atar tus pies a la tierra cuando pasa frente a tí una doncella que te mira y que sonríe; si tienes fuerza para amar siete veces en un día y no la tienes para resistir una vez el amor…

¡Pobre mancebo, pobre de tí, cuando la Xtabay conozca el camino que recorres cuando vuelves de la fiesta o cuando vas a buscar a la que está en lo más adentro de tu alma!

¡Pobre de tí! La Xtabay es la mujer que deseas en todas las mujeres y la que no has encontrado en ninguna todavía. ¡Ay de tí, si la ves aparecer una noche delante de tus pasos!

Verás, si la ves, que es bella como tú no has podido imaginar que una mujer sea bella. Porque tú has podido imaginar que es como un rayo de la luna que pasa por entre las hojas. Pero ella es más que eso.

Tú has podido pensar que es como una flor que se abre cuando amanece y que está mojada en el llanto de la noche, y perfuma como un incensario delante del dios; pero ella es más que eso.

Tú habrás podido soñar que tiene los ojos llenos de estrellas y que su frente es radiante como una nube en que se refleja el sol. Pero ella es mucho más que eso.

Tú, pobre de tí, cuando la oyes nombrar te estremeces y recuerdas el poder que tiene la voz hechicera de tu amada y la dulzura de su boca, que es para ti como cera con miel, y entonces es tu pensamiento todo ardiente como una brasa, y dices dentro de ti: “Ella es, que me saldrá al camino—” Pero ¡quiera tu suerte que la que temes y deseas no se ponga nunca delante de tus ojos! Porque la virgen que hoy consume de amor tus noches y tus días, ya para tí ha de ser menos que una hoja seca que se hace polvo en el viento de tu memoria, y de ella no querrás saber ya nunca más. Porque cuando hayas visto a la Xtabay, te parecerá que conoces la vida por primera vez. ¡Pobre de tí!

Pon cuidado. Cuando vayas solo por el camino a la luz de la luna y debajo de las estrellas, el viento del Oriente soplará sobre tí y te hará sentir que floreces como el árbol bajo la lluvia. Entonces serás joven como si tuvieras tres juventudes, y la Xtabay, que te ha espiado, se te aparecerá.

Has de verla, toda vestida de blanco, resplandecer sobre la tierra. Verás sus largos cabellos negros y brillantes, y verás sus manos entretejerlos y peinarlos con la hoja del ramón; y verás sus pies así como dos pequeños pájaros que vuelan junto al suelo.

¡Desdichado! Y sentirás sus ojos clavarse en tí como dos flechas que no te puedes arrancar. Así serán como las azagayas de cazar el mono, que tienen seis puntas del revés y penetran y ya no salen nunca. ¡Desventurado de tí, porque no sientes miedo ni dolor, sino locura de felicidad, y es que has visto al deseo y se te ha abierto, al mirarlo, el corazón!

Ella se mostró a tí en el aire, apenas posada sobre una gran piedra o resbalando sobre la cerca del maizal, y fué delante de tí, como arrastrándote.

¡Ah, cuán ligero tú para correr tras ella, que te llama con la mano y te sonríe con la boca y te hunde el filo de sus ojos hasta lo más adentro de tu raíz! ¡Qué susurro el de sus labios, que no se sabe si es voz o si es beso! ¡Qué deslumbrar el de su cuerpo, que no se sabe si es luz o llamarada!

Desaparece tras un árbol, y cuando te detienes y vas a reponerte, frotándote los ojos, ella aparece otra vez cerca de tí. Huye como un soplo, y tú la persigues como un suspiro.

Loca carrera es la que te arrebata, ¡loco de mal de amor! Pero si te pidieran la vida por tocarla una vez, setenta veces la darías. ¡Pobre de tí!

Ella escapa como un colibrí y tú vas tras ella, como la punta de un dardo. ¿A dónde te lleva y a dónde vas?

¡Ah, tú no lo contarás nunca, porque no has de volver! Jamás volvió nadie que a la Xtabay hubo seguido. Y todos los que la vieron la siguieron. ¿En dónde están, que no vuelven? Nadie lo sabe, dicen todos.

Hay algunos que se han armado con su valor, como con una coraza de cuero endurecido, y han llegado, en lo más silencioso de una noche clara, hasta el tronco de las ceibas, en donde vive la Xtabay, y han hecho sortilegio para hacerla salir y para interrogarla. Pero ella no ha venido a los que la llaman así, ni de otra manera.

Ella sale al camino del que va sólo y es arrogante y piensa en un amor. Porque ese ha de seguirla irremisiblemente. Ella no llama al que sabe que no la ha de seguir.

En el fondo de la tierra, en dónde las ceibas encantadas prenden sus raíces, están cautivos los cientos de miles de mozos que la Xtabay se llevó. Si ellos recordasen que el mundo existe, tal vez volvieran a contarnos lo que nadie sabe, y nadie sabrá, porque ellos no vuelven nunca.

¡Libre seas del maleficio de la Xtabay, joven amoroso y feliz, que no has de poder resístirle! Si yo pudiera darte un talismán, te lo daría. He aquí que lo hay, pero no puedo dártelo.

Porque lo tiene sólo aquel que ha podido llegar a la Xtabay y arrebatarle una hebra de su cabello, porque entonces ella le siguió a él como una esclava y él fue su dueño, y la mandó obedecer, y ella obedeció. ¿Quien es ese hombre? ¿En dónde está?

Búscale tú, si tienes fe; y encuéntrale si tienes fuerza.

Pero entretanto, desventurado de tí, si en el camino has de encontrar aquella que escapará como el humo y a quien tú seguirás como el viento; aquella, que cuando te haga su cautivo, te parecerá que sale del tronco de una ceiba y no sale sino del fondo de tu propio corazón!

3. Other Versions of the Xtabay Story

Ethnologists have long recognized the processual and relational character of oral tales, how they are shaped and reshaped by the physical and cultural context of their telling and by the genre expectations of both teller and audience. The two-women tale explaining the origin of the “evil” Xtabay, apparently created in the early twentieth century, provides a vivid example of this molding by genre as it locates the Xtabay within a moralizing European tale-type having little to do with Mediz Bolio’s tree-spirit version of the story. This tale tells of two beautiful women, Xkeban (the “sinner”), who wantonly enjoys casual sex but looks after abandoned creatures both human and animal, and Utz-Colel (the “virtuous”), who is admired for behaving correctly according to her society’s mores—but is cold and aloof and envies Xkeban’s greater beauty. After their death and burial, each woman’s true inner nature is revealed by the plant that springs up from her grave. Upon Xkeban’s grave blooms the sweet-scented white morning-glory called xtabentún, whereas Utz-Colel’s grave emits a foul odor, and in some versions a putrid-smelling cactus sprouts up there. This stark contrast between representative good and evil women is a recurring feature of European folktales, found, for example, in the Grimm Brothers’ two-sisters tale of “Mother Holle,”5 and many readers will recognize the symbolic plant as another commonplace. The plant motif appears in the most famous version of the traditional English folksong “Barbara Allen,” about a woman who is cruel to the man who loves her. After both die and are buried, “Out of sweet William’s heart there grew a rose/Out of Barbara Allen’s, a briar.”6 As for the morning-glory sprouting upon Xkeban’s grave, even a non-speaker of Mayan can recognize the similarity in sound between the names Xtabay and xtabentún, the Mayan name of that flower (Turbina corymbosa in botanical Latin). This white species of morning-glory with its psychedelic seeds7 is traditionally associated with the bewitching, mind-bending enchantress. But in this story, while the sweet flower is associated with Xkeban, it is prickly Utz-Colel who returns from the dead to become the evil Xtabay.

This is the version of the story repeated most often (for example, by Jesús Azcorra Alejos in his Diez Leyendas Mayas of 1998), but in it the nomenclature is skewed. The story’s association of the flower name xtabentún with good Xkeban and the name Xtabay with Utz-Colel makes no sense in terms of these echoing words, each beginning with xtab; obviously the xtabentún should be attached to the name Xtabay. Violeta H. Cantarell (2015) retells the story in a way that makes it cohere better. She substitutes “Xtabay” as the name of the good-hearted woman of the xtabentún, thereby erasing the allegorical name Xkeban (“sinner”). With this one move she reconfirms the Xtabay’s association with that sweet-smelling (psychedelic) morning-glory and dissociates her from evil, a disposition that some recent scholars argue was foisted upon her by Catholic colonialists as part of their exhaustive project aimed at suppressing native myths and legends (Avilés Rosado and Rosado Rosado 2001, n.p.; Baquedano 2009, pp. 77–84, especially p. 79; Reyes-Foster and Kangas 2016). In the revised story, when envious Utz-Colel comes back from the grave as a vindictive spirit, she is not the Xtabay; she merely imitates her seductive beauty to lure men astray in the forest. Sometimes she hides behind the trunk of a ceiba tree, but for the most part mention of that tree is erased from the story, presumably because an evil being could not be associated with a tree that is sacred (and a friend to indigenous people); so in place of that tree association, the story substitutes a foul smelling cactus.

Many other emanations of the Xtabay exist in folklore—or in the individual imaginations of those who comment upon her. The list that follows is not comprehensive. She may only be visible during a full moon, which associates her with the Mayan moon goddess Ix Chel (Ardren 2006; Preuss 2012, p. 4, without documentation); her mother was Ixtab the Mayan “suicide goddess” (Stavans 2020, p. 93, with no supporting evidence, perhaps intended allegorically); she is a protector of animals, or sometimes a goddess of the hunt (more about this below); she may be confused with the more famous Llorona, the Weeping Woman who steals unruly children and, like a banshee, can presage death to those who hear her howling (Miller 1973, p. 99; Bitto 2019, n.p.); she can turn herself into a tree or a snake (Taube 2003, p. 476, documentation unclear); she is a woman-snake in a black dress who may eat her victim after seducing him (!) (Stavans 2020, p. 93, without documentation; cp Bitto 2019, n.p.); and she may appear as a shape-shifter with a primary human form and a secondary bird form, a theme hinted at by Mediz Bolio. The artist Frances Dehlsen captures and extends this half-hidden raptor aspect of the alluring Xtabay by suggesting that her long hair is wings and giving her talons for feet in her illustration reproduced as Figure 3 below (Purnell 1931, p. 39). In “The Jungle Witch,” the tale for young children that goes with that picture, Idella Purnell tells essentially the same story as that told by Mediz Bolio, in whose book she may have found it, but she expands the tale with the moral message and fairytale ending expected at the time in books for children. In Purnell’s storybook version, several arrogant young hunters have disappeared from the village, having been captured and taken by the Xtabay into her lair under the roots of her tree. One who is less arrogant than the others enters the forest, sees the enchanting “witch” and advances toward her, mesmerized, but he perceives her raptor-feet just in time to leap forward and strangle her. The other hunters then reappear in the village, now subdued and better behaved, and when the villagers go into the jungle the next morning, they find an old turkey-buzzard lying beneath the tree with its neck broken (Purnell 1931, pp. 26–31). Whereas the underlying form of the Xtabay tale was probably a terrifying encounter with an apparition in the forest, in order to create a genre-determined “story,” both Mediz Bolio and Purnell attach a conclusion in which the human protagonist overcomes a monstrous Other. Mediz Bolio suggests using the fairy-tale lock of hair trick to turn the tables so that she, not he, becomes enslaved, whereas Purnell, turning the tale into a parable about pride and selfishness (1931, pp. 27, 31), goes farther to reduce that Other to a dead and mangled bird. Some might find it sad that the spirit of the sacred ceiba tree should come to such an inglorious end.

The beautiful Xtabay of legend is alive and flourishing, however, taking various forms both in the land of Mayab (Yucatán) and wherever else Mayans reside. Some versions have evolved so far from Mediz Bolio’s Xtabay of a century ago that only the woman’s name remains: In 1950 the celebrated singer Yma Sumac adopted the name Xtabay, moving the legend to her native Peru, and today in Portland, Oregon, the “Xtabay Vintage Clothing Boutique” sells clothing online.8 Both appropriations are based only on the legendary figure’s beauty. Or the name and a feature or two from the legend may link it to a newly adapted version of the Xtabay’s tale. Four videos provide examples of this. One is a song and dance show that presents the Xtabay as a pretty girl in a white Mayan dress who beckons and smiles at the men following her through a series of ruins. When the men, one by one, approach too closely to escape, she transforms into a lunging vampire with gaping toothy jaws (perhaps influenced by the film From Dusk Till Dawn—which notably ends on a Mayan theme). Another video’s voice-over softly narrates the two-woman version of the story, as images cycle through a succession of amateur artworks, with one picture showing a white-clad woman sitting in a ceiba tree. The tale in an educational video titled “The Xtabay Chased Us” appears to have been chosen as a typical example of current Mayan lore; it is recited by a young man living in Salinas, California, in Mayan with subtitles (Trilingual 2015).9 Masked as a turkey-vulture, Yamily Figueroa tells a version that neatly segues the two-women story into Mediz Bolio’s version, including the Xtabay’s trapping of men beneath the ceiba and the lock of hair to tame her, and giving her the feet of a fowl that he omits (Figueroa 2017). Of these videos, hers is the best. In the short story “Juan and Xtabay,” Miguel Angel May May tells how his protagonist Juan becomes the Xtabay’s victim because he is drunk (May May [1998] 2005). Currently, the Xtabay seems more interested in terrifying drunkards into abstinence than in trapping arrogant youths who invade her forest.

The forest-dwelling Xtabay has appeared recently in a more professional media form than the attempts listed above. The plot of Selva Trágica/Tragic Jungle (2020, Netflix) is loosely based on Mediz Bolio’s Xtabay poem, but includes elements reflecting urgent problems of our time.10 Film critic Jade Budowski praises Tragic Jungle as “a fascinating take on colonialism” in which woman and jungle join forces “to exact revenge on those who dare exploit them” (Budowski 2021). Although the film received some negative reviews, probably because it did not fulfill the reviewers’ fairytale expectations, it won in the Best Foreign Language Film category at the 2021 Venice Film Festival. The film’s presentation of the Xtabay as a forest guardian is closer to this author’s preferred understanding of her than to Mediz Bolio’s—he imagines her as a predisposition within the psyche. But she can prevail in both realms.

The Problem of Ixtab and Her Rope

Ixtab, a figure mentioned in early ethnological writings and interpreted as a minor Mayan goddess, is often associated with the Xtabay because of her similar name. This section explores that association, while reminding the reader that meaning in myth and legend is always contingent. The meaning of the name Ixtab itself is clear, however: ix is the female gender marker and tab means rope. On this basis, the “rope woman” of Dresden Codex glyph D53b (Figure 2a)11 has been interpreted as an illustration of Ixtab and the noose around her neck as a symbol of hanging, producing the idea of Ixtab as a “suicide goddess.” The source of this interpretation is a book of 1566, the Relaciónes de las cosas de Yucatán attributed to the Spanish friar Diego de Landa.12 After reporting the Mayans’ conceptions of a heaven and hell in the afterlife, the Landa text continues (in William Gate’s translation):

They also said, and held it quite certain, that those who had hung themselves went to this paradise; and there were many who in times of lesser troubles, labors or sickness, hung themselves to escape and to go that paradise, to which they were thought to be carried by the goddess of the scaffold whom they called Ixtab.(de Landa and Gates [1937] 2011, pp. 72–73)13

By placing the glyph of a woman with a rope around her neck (Figure 2a) in the margin next to this text, Gates silently associated this passage about Ixtab with that glyph from the Dresden Codex (de Landa and Gates [1937] 2011, p. 73). Alfred Tozzer, the next translator of Landa’s work into English, agreed with this association in a footnote, claiming that the figure was “undoubtedly Ix Tab” (Tozzer 1941, p. 132, n 619). That deity then quickly became known as a benevolent Mayan “suicide goddess,” especially when Sylvanus Griswold Morley supported Tozzer’s guess in his influential book The Ancient Maya, first published in 1946. He asserts that:

the ancient Maya believed that suicides went directly to Paradise. There was a special goddess who was the patroness of those who had taken their lives by hanging—Ixtab, Goddess of Suicide. She is shown in the Codex Dresdensis hanging from the sky by a halter which is looped around her neck; her eyes are closed in death, and a black circle, representing decomposition, appears on her cheek.(Morley [1946] 1956, pp. 202–203)

Morley’s firm identification became doctrine repeated without question by one ethnologist or archeologist after another (names cited by Reyes-Foster and Kangas 2016, p. 8), and in 2001 Cecilia Esperanza Avilés Rosado and Georgina Rosado Rosado adopted the “suicide goddess” concept upon which to build their argument that the transfer of Ixtab into the “evil” Xtabay was a colonialist appropriation of an archaic entity that occurred because a benevolent goddess who aided suicides to ascend to a better world could not coexist with the Catholic religion that regarded suicide as a sin (Avilés Rosado and Rosado Rosado 2001, n.p.). This idea of an indigenous “suicide goddess,” so plausibly expressed, has penetrated popular culture to the degree that some suicides in modern Yucatán have evoked tabloid headlines like “Ixtab took him!” (Reyes-Foster 2013, p. 256; cp. Reyes-Foster and Kangas 2016, pp. 5–6).14

But was there ever a suicide goddess? Questioning Landa’s authorship of the Relación, Beatriz M. Reyes-Foster and Rachael Kangas (2016) make a strong case that a “suicide goddess” named Ixtab who was the subject of the Dresden Codex glyph D53b never existed. Reyes-Foster had previously claimed, with some good supporting evidence, that Ixtab the suicide goddess had been inadvertently invented by early imaginative anthropologists (Reyes-Foster 2013), and three years later the two scholars joined forces to propose an alternative identification of Ixtab the "rope woman” as a goddess of hunting by trapping, rather than a “goddess of suicide.” (Compare the frequent portrayal of the Greek goddess Diana with a bow and arrow to represent hunting by shooting.) They then suggest that this reassessment links Ixtab, a forest hunter, directly to the Xtabay, a forest spirit (Reyes-Foster and Kangas 2016, pp. 10–20). The Dresden Codex picture can then be understood as a female figure shown with a rope snare around her neck, representing hunting in the forest15 and specifically indicating hunting by trapping. This suggestion is strengthened by the drawings of Mayan manuscript glyphs showing animals trapped in rope snares that William Gates scatters through his translation of Landa’s Relaciónes, usually alongside some mention of hunting (de Landa and Gates [1937] 2011, pp. 32, 86, 87, and 90).16 He inserts a glyph of an ensnared deer (see Figure 2b) next to this statement from Landa: “These tribes lived in such peace that they had no conflicts and used neither arms nor bows, even for the hunt, although now today they are excellent archers. They only used snares and traps, with which they took much game” (de Landa and Gates [1937] 2011, p. 32).

Interpreting Ixtab’s rope as a snare used to entrap animals offers a concept easily transferred to the Xtabay. Ixtab (as thus interpreted) and the tree spirit Xtabay share an association through themes of the forest, the hunt, and entrapment. This basis for the blending of aspects of Ixtab with a forest tree spirit is plausible because it captures the entrapment aspect of Ixtab with her identifying noose-as-snare and the Xtabay’s method of using herself as a lure in order to entrap men under her tree. As the myth evolves into modern legend, it is the method of hunting by luring and ensnaring shared by goddess and tree spirit that enables Ixtab’s name to be extended into “[i]Xtabay,” and perhaps gives the tree spirit some esoteric power along with the name.

The evolution of the Mayan story proposed here bears some similarity to that proposed for the far more famous Mexican Llorona. The first recorded encounter with this apparition, mainly a description of the sound of a weeping woman, “took place among Indigenous Mexicans in 1509 and was recalled in the 1550s” (Winick 2021, n.p.). To this weeping-woman encounter were added themes associated with the “weeping” Aztec goddess Cihuacoatl on the one hand, and a “white lady” narrative of European origin on the other (Kirtley 1960, p. 168). According to Américo Paredes, “[T]he legend of La Llorona struck deep roots in Mexican tradition because it was grafted on an Indian legend cycle about the supernatural woman who seduces men when they are out alone […] She is matlacihua or Woman of the Nets among Náhuatl speakers” (Paredes 1971, p. 103).17 Paredes’ idea of a thoroughly mestiza legend sounds very much like that of the Xtabay as proposed in this essay, even including the net, an implement of hunting by trapping similar to Ixtab’s rope snare.

The concept of the Guatemalan dog-spirit named cadejo may also have evolved much as did that of La Llorona and the Xtabay. A protective personal guardian or nahual with aspects of the ancient Aztec dog-headed god Xolotl may have existed within folk culture before being modernized into a perro-guardián de los borrachos (guard-dog of drunkards), a ghostly white Lazie (Lassie) who shepherds an inebriated man home, or may lose him in the forest if he has a mean heart (Catalán 2021, n.p.). But in many places this helpful spirit is divided into two cadejos appearing as angelic and demonic creatures, a white dog and a black one. According to Catalán this is “a consequence of the chromatic dualism dominant in Western Europe that was transplanted in America through Spanish Catholicism […]. Thus ‘the cadejo’ is a mixture [mestizo, i.e., a combination of indigenous and European themes] like ‘La llorona’ and many other beings that populate the popular imagination of Guatemalans, Central Americans, and Latino-Americans” (roughly translated from Catalán 2021, n.p.)

These factors suggest that when the Catholic conquerors intentionally revised the ancient gods into demons, they also tried to reimagine lesser beings like the Xtabay as purely “evil”, but they could not succeed entirely. Christian European culture has a strong tendency to perceive binaries where others might perceive wholeness or a spectrum, so that an original being having both beneficial and dangerous qualities might require re-embodiment in two clearly opposing figures. Such a bifurcation leads to the inherently ambivalent Xtabay of the thorny ceiba tree gaining an origin story about two morally contrasting women, and similarly to the cadejo splitting into black and white spirit dogs. In both cases the sharp dualism seems very European. Sylvia Marcos offers a sophisticated explanation of this indigenous worldview, so alien to that of the conquerors, in “A world constructed by fluid dual oppositions, beyond mutually exclusive categories,” Section 5 in her essay titled “Subversive Spiritualities” (Marcos 2017, pp. 118–21).

The mutually exclusive dualistic ethics of European fairytale, the preoccupations of high-culture Modernism, and the current popular media, all of which have had their effect upon the Xtabay or given her new forms, are alien to Mayan culture. Considering that alienness, even though Mayan men continue to encounter the beautiful apparition, some might dismiss the modern Xtabay as too diluted an entity to qualify as a Mayan legend at all. The eminent Mayanist Karl Taube might take issue with such a dismissal. Speaking of ancient myths that in modern times have emerged in combination with elements that “are not pre-Hispanic in origin,” he says, “these are not indications of a dying or decadent mythical tradition, but rather proof of a thriving oral legacy that continues to respond to a constantly changing world” (Taube 1993, p. 77).

4. Conclusions

Accepting the Reyes-Fostor and Kangas argument that the Rope Woman Ixtab is a goddess of the hunt rather than of the scaffold (that having perhaps been Landa’s misunderstanding of what his informant was trying to tell him), one can suggest a development of the Xtabay’s identity something like this: She may have originated through animism as a spirit of the sacred ceiba tree, taking occasional bird-form as denizen of that tall tree. She gained substantial form and a name by association with Ixtab, the Rope Woman. Then, in the early twentieth century the hybrid Ixtab-[i]Xtabay figure seems to have slipped into the hinterlands of Mayan culture, unavailable to folklorists; she does not appear in Frances Toor’s exhaustive collection of Mexican folktales (Toor and Mérida 1947). However, Antonio Mediz Bolio knew of her, retrieved her, and “civilized” her. From disguising herself as an available maiden alone in the woods (a potential rape victim), in order to lure lusty young men to their doom, in the hands of Mediz Bolio she became the less violent but still erotic dream of a young man’s lovelorn fantasy. Influenced by the vogue for spiritual distress in the Latin American modernist culture of his time, Mediz Bolio further modified the story by having the Xtabay lead her lovelorn victim not only under her tree and into the depths of the earth, but into the depths of despair. It may have been around the same time that the two-women story was invented to explain how she became an evil spirit, or to reconceive her as such. Today the Xtabay, still an alluring female in a moon-white gown, has once again slipped away from her form as a high-culture entity and into a folk culture realm where storytelling is led by practical social issues. Sometimes seen in the shadows of the sacred ceiba tree, today she is often identified with the terrifying night forest more generally (Taube 2003, p. 476), and she may appear as a ravenous shape-shifting demon whose prey is the man who not only trespasses upon her forest realm at night, but also crosses the line in terms of his own village culture—being married and unfaithful, or drunk. In her fluid identity the Xtabay is not an easily defined and contained being, but a process entangled with shifting cultural concerns: conceived in a moment of transcendent awe of a spectacular tree, the ceiba’s embodied spirit merges with the hunt-goddess Ixtab and adopts her name, goes into hiding for a while in the oral culture of the countryside, is discovered and redefined by a famous Mayan poet in his lovely poem, and finally mutates into a horror movie bogeywoman to keep young men and husbands in line. Whereas claims about legends of supernatural beings are by their nature speculative, one may nevertheless state this about the ephemeral shape-changing Xtabay: she may often wander far from the forest tree that gave her birth, but she remains alive and alluring in the modern Mayan world. However, one might wish to elaborate the legend, whether to turn it into a fiction with a conclusion, or theorize it through a feminist or colonialist lens, or by some other means,18 at heart the unadorned legend of the Xtabay is a cautionary tale: Beware, young man—

Do not go into the jungle alone.Ay, cuidado! Her nest of bone!

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

I thank my mother for introducing me to the Mayan tree-spirit called the Xtabay when I was a child, and I express my gratitude here also to my Research Assistant Melissa X. Stevens for her consistently engaged support of this project with her fine-tuned research and editorial skills.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1. | dry-, Gk., drys, gen. sg. dryos: the oak, sacred to Zeus. In A Grammatical Dictionary of Botanical Latin. Available online: http://www.mobot.org/mobot/latindict/keyDetail.aspx?keyWord=dry (accessed on 11 May 2022). [Dryos “oak” from PIE *dero “tree,” especially oak.] |

| 2. | It is difficult to describe the semi-sound that is pronounced before the s-h sound of the X. William Gates (de Landa and Gates [1937] 2011, p. 170) calls it by the technical term “glottal stop,” which is close. Simply separating the sh sound from the following t with the spelling X’tabay will achieve it pretty well, almost like ish-tabay but lighter on the i preceding the sh. The popular spelling Xtabay will be used here, with the acknowledgment that others spell the name more accurately as X’tabay. |

| 3. | The Llorona also acquired an origin tale to explain her weeping, but it has become integrated into her legend, whereas the Xtabay’s two-woman origin tale is incompatible with her botanical associations, as will be seen. Deforestation may have been a component in that story’s separation of the Xtabay from her original association with the ceiba tree. |

| 4. | Like many literary figures of Latin America, Mediz Bolio was also an educator and a politician, at one time serving as a senator of the Mexican Republic. As a widely published writer he produced poetry, essays and plays (including opera and movie scripts), but his literary and political influence transcended all of these individual professions and accomplishments. |

| 5. | According to the Aarne and Thompson ([1928] 2004) system of classifying international folk tales, “Mother Hulda” belongs to tale type AT 480 under the heading “The Kind and the Unkind Girls”. |

| 6. | This version of “Barbara Allen” was made famous by Joan Baez. There is no flower motif in the three versions that Francis James Child (1882) collected (“Barbara Allen” is Child #85), but the motif occurs in other traditional ballads in his collection (e.g., “Lord Loval,” Child #75), and it is attached to “Barbara Allen” in several of the twenty versions in (Bronson 1976). The motif may have been added in order to wrap up the harsh story in a pleasant, though not quite justified, manner. |

| 7. | The seeds of the xtabentún plant contain an ergoline alkaloid similar in structure to LSD. In the 1950s the CIA investigated the psychedelic properties of a number of plants including this one as part of its MKUltra Subproject 22, a covert search for chemicals facilitating mind-control. John Marks (1979) offers a popular account of this search for hallucinogenic plants like xtabatún (see especially pp. 106–107). |

| 8. | For the Xtabay Vintage Clothing Boutique (nothing to do with Mayan culture) see https://shopxtabay.com/collections/vendors?q=Xtabay%20Vintage%20Clothing%20Boutique (accessed on 22 July 2022). |

| 9. | Trilingual: Short Maya narrative about Xtabay, learn Yucatec Maya, Yucatan Mexico. YouTube video, posted by NP4Mayans, 9 January 2015. Available online: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mNZwoiY_n9s (accessed on 11 May 2022). On this educational language video the Mayan text is provided below the video, followed by translations into Spanish and English. |

| 10. | The IMDb (Internet Movie Database) lists the following films associated with Mediz Bolio: Judas; screenplay (Mediz Bolio 1936), Viaje al surest; screenplay (Sandoval 1936), Mi madrecita; screenplay (Elías 1940), El amor de los amores; director (Mediz Bolio 1944), La selva de fuego; screenplay (Davison 1945), and Tragic Jungle (Olaizola 2020). |

| 11. | The Dresden Codex, so named because it is archived in the Saxon State Library in Dresden, is one of the oldest Mayan manuscripts extant and the most complete, dating to early medieval times and referring to an even older text. (The burning of ancient Mayan codices in the name of the Church in the sixteenth century reduced a great wealth of these precious manuscripts to a pitiful few). The focus of the Dresden Codex upon astronomical data, and on eclipses in the section where the Rope Woman figure is found, suggests her association with the moon. |

| 12. | Although what Landa recorded in the Relaciones provides much of what we know about the ancient Maya, inestimately more was lost in the vast quantity of original Mayan manuscripts that Landa ordered to be burnt because of their “demonic” content. Moreover, his treatment of the Indians under his authority was so harsh and even illegal that he was sent to Spain for trial, and it was then that he wrote the Relaciones, mainly in order to exculpate himself. See William Gates’ introduction to Landa 2011 for an account of Landa’s crimes against the native Mayans, especially pp. 12–13, but also in footnotes on pp. 42 and 46 and passim (de Landa and Gates [1937] 2011). (Gates was criticized for including such attention to political acts in his translation.). |

| 13. | In his translation of 1937, William Gates silently associates identification of Ixbay with the Rope Woman glyph (Figure 2) by placing that glyph in the margin of the Relaciones text next to this passage about hunting with snares (de Landa and Gates [1937] 2011, p. 73). |

| 14. | This is an extraordinary example of what Mary Louise Pratt calls “autoethnography,” where a native culture adopts as its own a story or attribute imposed on them by non-native scholars. To express this in Pratt’s own words with more nuance: “Guaman Poma’s New Chronicle is an instance of what I have proposed to call an autoethnographic text, by which I mean a text in which people undertake to describe themselves in ways that engage with representations others have made of them. Thus if ethnographic texts are those in which European metropolitan subjects represent to themselves their others (usually their conquered others), autoethnographic texts are representations that the so-defined others construct in response to or in dialogue with those texts” (Pratt 1991, p. 35). This construct involves “a selective collaboration with and appropriation of idioms of the metropolis or the conqueror” (Pratt 1991, p. 35). |

| 15. | Because the forest was a designated male space, hunting was construed as a male province (see Taube 2003, p. 485). |

| 16. | Constructing a snare is simple with components readily available in nature, and it need not even involve a lure if the trap is set carefully in the prey’s accustomed path. “The Snare Shop” sells such equipment online. Snaring is an exceptionally cruel form of hunting that can trap an unintended form of prey (for example, a lost dog or cat). |

| 17. | Currently La Llorona reimagined serves as an inspirational figure in Chicana literature. According to Domino Renee Perez, “La Virgen, La Malinche, and La Llorona have become—whether through our acceptance, rejection, or reworking of their stories—central to the formation of Chicana feminist thought” (Perez 2008, p. 44). |

| 18. | For a theoretically informed discussion of the Xtabay, see (Manzanilla 2019). The abstract of his dissertation begins, “This study addresses aspects of monstrosity from a transdisciplinary and comprehensive perspective that combines postcolonial, postmodern, queer, and overall, postfeminist studies in a realm of Latin American Cultural Production.” His fourth chapter discusses the legend of the Xtabay and femicide, with a section introducing “The X’tabay” as a “palimpsest of female monstrosity,” and a later section arguing, with supportive reference to the theory of Ixtab as goddess of suicide and to IxChel as goddess of the moon (and more), that the Xtabay serves as a “foundational monster” (p. 183) and corresponds to the Great Mother archetype (p. 185). This interpretation of the Xtabay would work equally well if not better with Ixtab interpreted as goddess of the hunt together with IxChel as goddess of the moon (which would coincidentally match the two main identifiers of the equally multifaceted goddess Diana). The author’s incorporation of Bourdieu’s habitus theory as a way of being makes his argument especially interesting. His discussion has far more depth and nuance than is possible to convey in this brief note. |

References

- Aarne, Antti, and Stith Thompson. 2004. The Types of the Folktale: A Classification and Bibliography. Helsinki: Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia. First published 1928. [Google Scholar]

- Ardren, Traci. 2006. Mending the Past: Ix Chel and the Invention of the Modern Pop Goddess. Antiquity 80: 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Avilés Rosado, Cecilia Esperanza, and Georgina Rosado Rosado. 2001. De la Voz de la Escritura: La Figura Femenina en los Mitos. In Mujer Maya: Siglos Tejiendo una Identidad. Edited by Sergio Quezada and Georgina Rosado Rosado. Mérida: Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán, Mexico City: Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes: Fondo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes, Available online: http://www.mayas.uady.mx/articulos/escritura.html (accessed on 11 May 2022).

- Baquedano, Gaspar. 2009. Maya Religion and Traditions: Influencing Suicide Prevention in Contemporary Mexico. In Oxford Textbook of Suicidology and Suicide Prevention: A Global Perspective, 1st ed. Edited by Danuta Wasserman and Camilla Wasserman. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitto, Robert. 2019. Xtabay: Jungle Witch of the Maya. Mexico Unexplained. May 5 Podcast Audio and Transcript. Episode 144. Available online: https://mexicounexplained.com/xtabay-jungle-witch-of-the-maya/ (accessed on 11 May 2022).

- Bronson, Bertrand Harris. 1976. The Singing Tradition of Child’s Popular Ballads. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Budowski, Jade. 2021. ‘Tragic Jungle’ On Netflix: A Mesmerizing Mexican Allegory Where Revenge Takes Center Stage. Decider.com. Available online: https://decider.com/2021/06/10/tragic-jungle-netflix-review/ (accessed on 30 April 2022).

- Cantarell, Violeta H. 2015. Xtabay: Legend with Aroma. Yucatán Today 28: 60. Available online: https://issuu.com/yucatantoday/docs/yucatan_today_oct_15_-_nov_14__2015 (accessed on 5 June 2022).

- Catalán, Nestor Véliz. 2021. El Cadejo, perro-guardián de los borrachos en ciudad de Guatemala. Morelia: Celdas Literarias Colegio de Filosofía y Letras, Universidad Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz. [Google Scholar]

- Child, Francis James. 1882. The English and Scottish Popular Ballads. Cambridge: The Riverside Press, Available online: https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Child%27s_Ballads (accessed on 30 April 2022).

- Davison, Tito. 1945. La Selva de Fuego. Mexico: Producciónes Grovas, December 27. [Google Scholar]

- Elías, Francisco. 1940. Mi Madrecita. Mexico: Arzos & Gene, May 8. [Google Scholar]

- Figueroa, Yamily. 2017. La Xtabay: La Leyenda Maya Yucateca de Terror. YouTube Video, Posted by Yamily Figueroa, 29 October 2017. Available online: https://youtu.be/L80eUIRNtVQ (accessed on 23 June 2022).

- Kirtley, Bacil F. 1960. La Llorona and Related Themes. Western Folklore 19: 155–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Landa, Diego, and William Gates. 2011. Yucatan Before and After the Conquest. Translated by William Gates. New York: Zuubooks, Baltimore: Maya Society Publication 20. First published 1937. [Google Scholar]

- Manzanilla, Roberto de Jesus Ortiz. 2019. Monstruosidad y Aesthet(h)ical Encounters en la Producción Latinoamericana Contemporánea. Tres Posibilidades de Aproximación: Perú, Brasil y México. Ph.D. dissertation, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ, USA. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/2286/RI55699 (accessed on 22 July 2022).

- Marcos, Sylvia. 2017. Subversive Spirituality: Political Contributions of Ancestral Cosmologies Decolonizing Religious Beliefs. In Dynamics of Religion: Past and Present. Edited by Christoph Bochinger and Jörg Rüpke. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 109–30. [Google Scholar]

- Marks, John. 1979. The Search for the “Manchurian Candidate”: The CIA and Mind Control. New York: Times Books. [Google Scholar]

- May May, Miguel Angel. 2005. Juan and Xtabay. In Words without Borders. Translated by Earl Shorris, and Silvia Sasson Shorris. Lajump’éel maaya tzikbalo’ob in Diez relatos mayas. Mexico City: Instituto Nacional Indigenista. First published 1998. Available online: https://www.wordswithoutborders.org/article/juan-and-xtabay (accessed on 25 May 2022).

- Mediz Bolio, Antonio. 1922. La Xtabay. In La Tierra del Faisán y del Venado. Buenos Aires: Contreras y Sanz, pp. 186–93. Available online: https://archive.org/details/latierradelfaisa00medi/page/186/mode/2up?ref=ol&view=theater (accessed on 25 May 2022).

- Mediz Bolio, Antonio. 1936. Judas. Mexico: Remex, September 4. [Google Scholar]

- Mediz Bolio, Antonio. 1944. El Amor de los Amores. Mexico: Films Victoria, May 5. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Elaine K. 1973. Mexican Folk Narrative from the Los Angeles Area. Austin: American Folklore Society. [Google Scholar]

- Morley, Sylvanus Griswold. 1956. The Ancient Maya, 3rd ed. Revised by George W. Brainerd. California: Stanford University Press. First published 1946. [Google Scholar]

- Olaizola, Yulene. 2020. Tragic Jungle. Mexico City: Melacosa Cine, September 9. [Google Scholar]

- Paredes, Américo. 1971. Mexican Legendry and the Rise of the Mestizo: A Survey. In American Folk Legend: A Symposium. Edited by Wayland D. Hand. Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 97–107. [Google Scholar]

- Perez, Domino Renee. 2008. There Was a Woman, La Llorona from Folklore to Popular Culture. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pratt, Mary Louise. 1991. Arts of the Contact Zone. Profession. pp. 33–40. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25595469 (accessed on 29 July 2022).

- Preuss, Mary H. 2012. The lights dim but don’t go out on the stars of Yucatec Maya oral literature. In Parallel Worlds: Genre, Discourse, and Poetics in Contemporary, Colonial, and Classic Period Maya Literature. Boulder: University Press of Colorado, pp. 449–70. [Google Scholar]

- Purnell, Idella. 1931. The Wishing Owl: A Maya Story Book. Illustrated by Frances Purnell Dehlsen. New York: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Reyes-Foster, Beatriz. 2013. He Followed the Funereal Steps of Ixtab: The Pleasurable Aesthetics of Suicide in Newspaper Journalism in Yucatán, México. Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Anthropology 18: 251–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Foster, Beatriz M., and Rachael Kangas. 2016. Unraveling Ix Tab: Revisiting the “Suicide Goddess” in Maya Archaeology. Ethnohistory 63: 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval, Humberto Ruiz. 1936. Viaje al Surest. Mexico: Humberto Ruiz Sandoval, December 31. [Google Scholar]

- Stavans, Ilan. 2020. A Pre-Columbian Bestiary: Fantastic Creatures of Indigenous Latin America. Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Taube, Karl. 2003. Ancient and Modern Mayan Conceptions about Field and Forest. In The Lowland Maya Area: Three Millenia at the Human-Wildland Interface. Edited by Arturo Gómez-Pompa, Michael F. Allen, Scott L. Fedick and Juan J. Jiménez-Osornio. New York: Food Products Press. [Google Scholar]

- Taube, Karl. 1993. Aztec and Maya Myths. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Toor, Frances, and Carlos Mérida. 1947. A Treasury of Mexican Folkways: The Customs, Myths, Folklore, Traditions, Beliefs, Fiestas, Dances, and Songs of the Mexican People. New York: Bonanza Books. [Google Scholar]

- Tozzer, Alfred M. 1941. Landa’s Relación de las Cosas de Yucatan: A Translation. Cambridge: Peabody Museum of American Archeology and Ethnology, Harvard University. [Google Scholar]

- Tozzer, Alfred M., and Glover M. Allen. 1910. Yucatan deer, caught in a snare, Tro-Cortesianus 48b. In Animal Figures in the Maya Codices. Cambridge: Museum of American Archaeology and Ethnology, Available online: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/19042/19042-h/19042-h.htm (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- Trilingual: “The Xtabay Chased Us,” Short Maya Narrative about Xtabay, Learn Yucatec Maya, Yucatan Mexico. 2015. YouTube Video, Posted by NP4Mayans, 9 January 2015. Available online: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mNZwoiY_n9s (accessed on 21 May 2022).

- Winick, Stephen. 2021. La Llorona: Storytelling for Halloween and Día de Muertos. Blog. In Folklife Today: American Folklife Center & Veterans History Project; Library of Congress. Available online: https://blogs.loc.gov/folklife/2021/10/la-llorona-storytelling-for-halloween-and-da-de-muertos/ (accessed on 29 July 2022).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).