Abstract

Australia’s brutal carceral-border regime is a colonial system of intertwining systems of oppression that combine the prison-industrial complex and the border-industrial complex. It is a violent and multidimensional regime that includes an expanding prison industry and onshore and offshore immigration detention centres; locations of cruelty, and violent sites for staging contemporary politics and coloniality. This article shares insights into the making of a radical intersectional dance theatre work titled Jurrungu Ngan-ga by Marrugeku, Australia’s leading Indigenous and intercultural dance theatre company. The production, created between 2019–2021, brings together collaborations through and across Indigenous Australian, Kurdish, Iranian, Palestinian, Filipino, Filipinx, and Anglo settler performance, activism and knowledge production. The artistic, political and intellectual dimensions of the show reinforce each other to interrogate Australia’s brutal carceral regime and the concept of the border itself. The article is presented in a polyphonic structure of expanded interviews with the cast and descriptions of the resulting live performance. It identifies radical ways that intersectional and trans-disciplinary performances can, as an ‘act of liberation’, be applied to make visible, embody, address, and help dismantle systems of oppression, control and subjugation.

Keywords:

intersectional; performance; contemporary dance; borders; incarceration; abolition; Marrugeku 1. Abolitionist Strategies through Performance and Polyphony

In April 2021, Australia’s leading Indigenous-intercultural dance theatre company, Marrugeku, presented a community preview of its latest work Jurrungu Ngan-ga to audiences in the small remote town of Broome, north Western Australia. The company is based on the lands of the Yawuru people, the custodians of the lands and waters of Rubibi. Jurrungu Ngan-ga responds to places and peoples that have been targeted by Australia’s long-standing neo-colonial appetite for incarceration—particularly addressing events over the past decade. Jurrungu Ngan-ga, meaning ‘straight talk’ in the language of the Yawuru People, examines the common thread that connects outrageous levels of Indigenous incarceration in Australia to the government’s indefinite detention of asylum seekers. The project’s creative team interrogate and stage this link as performed in the ‘prison of the mind of Australia’. Together they challenge its legitimacy through the lens of what Waanyi writer Alexis Wright explains as ‘the sovereignty of the mind’.1 (Wright 2019) That is, an Indigenous sovereignty that is outside the reach of the settler state and its mechanisms of policing. This is performed and staged in Jurrungu Ngan-ga through choreopolitical acts of resistance, survivance and straight talking.

To undertake this ‘act of liberation’ Marrugeku’s co-artistic directors: Yawuru/Bardi dancer and choreographer Dalisa Pigram and settler director Rachael Swain, together with the wider artistic and cultural team have applied Marrugeku’s improvisational dance theatre processes to investigate two key source texts. These were the documentary Australia’s Shame (Meldrum-Hanna and Worthington 2016), exposing the abuse of young Indigenous boys in the Don Dale Youth Detention Centre, and the novel No Friend but the Mountains—Writing from Manus Prison by Behrouz Boochani, translated by Omid Tofighian (Boochani 2018).2

The work is performed by a cast that reflects the intersectional character of the project and the driving ideas behind it: Indigenous Australian dancers from many Nations (both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander), and settler dancers of Palestinian, Filipino and Filipinx, and English/Irish heritage. Company members and their families have lived experience of displacement, exile, incarceration, and settler privilege, all of which have informed their improvisational responses to the source texts.

Jurrungu Ngan-ga is staged around a giant perforated mesh installation designed by Malaysian-Australian visual artist Abdul-Rahman Abdullah, which itself ‘performs’ the dichotomy and ambiguity of the ‘inside’ and the ‘outside’—of who is in prison and who is free. This gives material expression to responses by Abdullah to critical points identified by Boochani and Tofighian throughout No Friend but the Mountains. The construction of the perforated mesh enables it to be front or back lit in ways that can both reinforce its harsh immovable nature but can equally enable it to become translucent, revealing its own flimsy construction. This in turn can include or exclude, centre or dislocate those on either side of the divide. Abdullah thus reclaims the border and deconstructs it, repositioning it as a liminal space. This perspective is aligned with Australian Indigenous understandings of boundaries distinguishing Nations, which are conceived as wider sites of negotiation and mutual or interactive responsibility.

With its trans-disciplinary language of installation and real-time security camera footage; its costume design of ‘immigration basics’ and ‘corporation state’3 and choreography channeling fear, denial under pressure, brutality, and also theatricalised moments of listening and straight talking, Jurrungu Ngan-ga embodies and foregrounds the sites, bodies and voices of multiple marginalised communities. This trans-disciplinary and intersectional expressionism is key for exposing Australia’s carceral fetish and also creates visions and strategies for abolition.

The nine performers of Jurrungu Ngan-ga inhabit the prison of the mind of Australia as figments conjured by its own imagination. The audience witness scenes of detention brutality, culturally situated acts of resistance and freedom, direct and deeply personal addresses to the security camera and a ritual honouring of names of those who have died in custody on Australia’s watch. Each moment channels key events from recent years within Australia’s carceral-border regime. These scenes are interwoven within a fabric of Marrugeku’s unique intersectional gestural dance language, which seeks to embody the disputed and disrupted site of the border itself. As the production progresses this choreopolitical neo-expressionism shifts from a mechanical embodiment of denial to a more trance-like and receptive collectivity. At the same time, the dancers’ distinctly individual movements continue to be punctuated by retrograde actions and performed glitches that appear to momentarily revisit fragments of colonial imagery/contemporary persecution. Thus, the collective language of exchanged gestures does evolve into a new kind of mobilisation, yet one that continues to be ruptured by collapse, loss and regurgitated moments of violence.

Just as Jurrungu Ngan-ga is a polyphonic work, this article is a polyphonic document that foregrounds the voices and actions of the co-devising performers discussing their experience of the choreographic process and how their backgrounds contribute to the conception and realisation of the work. Excerpts from interviews with the cast conducted by Omid Tofighian4, in his role as one of the cultural dramaturgs of Jurrungu Ngan-ga5 are woven together with descriptions of key scenes in the work and script excerpts. In positioning the interviews with the cast alongside windows into the performance (as seen below in Box 1, Box 2 and Box 3) we aim to demonstrate an Indigenous-intersectional reclamation and re-mapping of the concept of ‘boundary’ as a site of care, responsibility, and negotiation.

Box 1. Performance Description 1. Prologue.

It is the end of April 2021 as Marrugeku, begin

performing their Broome community preview. A ‘super moon’ rising behind the

stage is causing equally super low tides in the mangrove swamps near the

outdoor theatre—meaning the sandflies are out in force. It’s the last days of

Marrul season bringing the cross over from humid to dry heat. The audience

drips sweat as fruit bats chirp and the sounds of locals and those who have

drifted in from out of town float through the theatre. A large boab tree can

be seen ghosting the perforated mesh wall that frames the performance space.

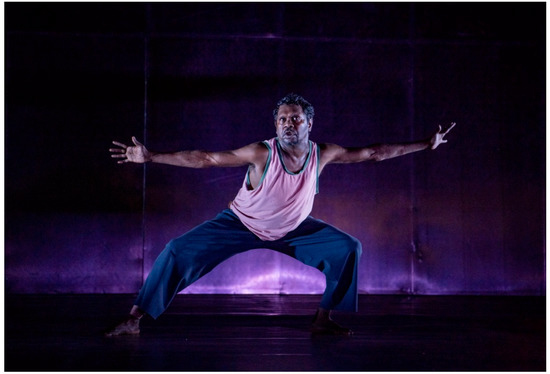

Emmanuel James Brown, (EJB) a

Bunuba/Walmajarri/Gooniyandi/Wangkatjungka dancer and actor from Fitzroy

Crossing in the central Kimberley region of Western Australia enters the

stage—treading lightly but with purpose. Each footfall appears to be engaged

in the act of lifting from the floor just as it touches down. His movements

could be mistaken for tentativeness but are in fact a response-ability. His

gaze darts in several directions. In the low light, his shoulders ripple,

arms reaching wide. His long expressive fingers seem to reach for connections

to other places, hinted at by the breeze that we hear in the soundtrack. He

is listening as if his limbs feel the implications of the sounds that are coming

to him from afar. Figure 1.

The audience hears the distant voice of Farhad

Bandesh singing in a Kurdish vocal tradition. The program tells the audience

this song was recorded while Farhad was incarcerated in Australia’s offshore

immigration detention centre on Manus Island in Papua New Guinea. His lament,

along with location recordings of dogs howling in the undergrowth at night

and sounds of protest—“don’t kill us, don’t kill us”, are perhaps filtered

more through corrosive government border protection policy and politician’s

power games than the physical distance between the two Indigenous men on the

two islands of Manus and Australia. As if collapsing that space between them—

or rather, foregrounding their connection—EJB reacts to the sounds,

alternately folding in on himself and reaching out, unravelling, and

reforming. He turns suddenly towards unseen events, memories, or voices and

with the deft flick and stamp of the traditional dance forms of the central

Kimberley, he seems to absorb the story behind the voices and continue his

path. Behind him the harsh glimmering wall of the set ghosts his every move,

framing both his solo dance but also highlighting the absence of those who

are not physically there. In the dim light, the wall looms yet is

translucent, glowing as if awake with its own knowing. The movements of EJB

and the voice of Farhad reach across that which separates Manus and

Australia, collapsing the border, or infiltrating it. Together they render it

impotent.

Figure 1.

Emmanuel James Brown in Jurrungu Ngan-ga. [Photo Abby Murray, Broome 2021].

Australia’s brutal carceral-border regime is a colonial system of intertwining systems of oppression that combine the prison-industrial complex and the border-industrial complex. It is a complex regime that includes an expanding prison industry and onshore and offshore immigration detention centres; locations of cruelty, and violent sites for staging contemporary politics and coloniality. This article identifies radical ways that intersectional and trans-disciplinary performance can, as an ‘act of liberation’, be applied to make visible, embody, address, and help dismantle systems of control, separation and subjugation. Through performance, music and design, Jurrungu Ngan-ga exposes and challenges state violence and helps imagine strategies for abolishing Australia’s carceral-border archipelago (Tofighian 2021; Galbraith et al. 2021).

Drawing on white settler Australia’s historical founding as a penal colony, the prison is both an instrument of white supremacy and a symbol of a national identity grounded in a colonial imaginary. The Indigenous subject, and their custodial relationship to place (Country), embodies and represents an internal threat to this symbolic and very real state system of dominance and control.6 At the same time, those seeking asylum and arriving by boat represent an external threat to the very same systems. The passage to Australia by boat of those seeking asylum between 2001–2013 led to their subsequent imprisonment in the offshore detention centres on small Pacific states—Manus Island in Papua New Guinea, the Republic of Nauru, and the Australian territory of Christmas Island.7 This policy was alarmingly named the ‘Pacific Solution’ by successive governments and renamed Operation Sovereign Borders in 2013.

2. Question: Embodied Expressions of Struggle?

Omid Tofighian: This project is dedicated to breaking down structures, exposing things, holding a mirror up to the nation and making it look at its ugly face. I am interested to know how you draw power from your culture and how you draw power from your experience living in Australia, and how you express that through your body. Dance is so central to your life, your personality and your future. One of the things that really had an impact on me while working on Jurrungu Ngan-ga was learning about everyone’s personal struggle. It made me reflect on the work I do with people in immigration detention centres. I realised the extent to which your lives are also constantly on a knife-edge. In immigration detention, people feel like they are on a tight rope, or they are living under an axe. At any moment the system could just attack. The context is very different but when you describe your personal struggles, I cannot help but be automatically taken back to thinking about the physical, psychological, and emotional dangers people face in detention. I am interested in how you live and resist in Australia, how that has informed your understanding of the situation of incarcerated people.

2.1. Bhenji Ra

Jurrungu Ngan-ga is a different type of activation or activist space, especially since it involves the body, collectives of bodies and creativity. When thinking about my own experience I think about the ways trans bodies are both overly politicised and criminalised in our society, so in that sense, we always had to take action as a community. We are always involved in a perpetual action, in both our daily and political lives. There is no separation especially when you think about how just our existence is political. That is not to say it’s not exhausting and these days, as I find myself in leadership roles, I’m actually looking outside of my community for resources. If I want to understand what leadership feels like I need to see how others keep communities together. Often when I attend an action or protest I find myself with a lot of questions about how we are protesting, how we are being together. Sometimes I think: this protest is too patriarchal. This protest needs feminine energy. Where are the matriarchs? Even things like ‘this action needs to be sexy’. It is missing something. Toni Cade Bambara says the role of the artist is to make the revolution irresistible. I always have to remember that, because if it does not awaken us to something else, we get stuck in mini-institutions and nothing gets disrupted. I think what transness does when introduced to a space characterised by binaries, is that it disrupts. It pulls everything apart, it does something without even needing to be critical, it brings up questions: Where does she belong? What is a woman? Why are we attached to these binaries when they are created by the system? It is beautiful when trans people enter spaces, especially abolitionist spaces. When there is so much complexity to welcome in you see how dangerous and limiting spaces become when built on binaries. There is no space that can hold trans people in that way. You think you can hold them like you think you can hold people in prisons or immigration detention. They do not fit in these walls; they do not belong in these cells. In fact, we make them obsolete.8

2.2. Chandler Connell

Since joining the creation period of Jurrungu Ngan-ga I have learnt more about the dark truths of Australia and its systematic ways. I have been surrounded by my Indigenous culture, especially over the last ten years, but then I started having conversations with people about this work we are creating and so much more became visible to me. The more I learn about First Nations people through culture I notice that so much is based on circles. That makes sense in my mind, I see it within circles and cycles. But then when it comes to these Western mob it is all squares. All colonial structures. Time is within a colonial structure, space is within a colonial structure, and energy is within a colonial structure. We are forced into squares so they can manipulate us more easily and they squeeze and try and mold us. That is when they put us in jails, they put us under surveillance. But we resist. People come into the creative process in Jurrungu Ngan-ga from different angles. Here you can develop your own creation process and stop allowing people to tell you how to think, how to move and how to do things.9

2.3. Emmanuel James Brown (aka EJB)

Dancing is like telling a story for Indigenous cultures throughout Australia. That is how the Gooniyandi, Bunuba, Walmajarri and Wangkatjungka people have been doing it in the Fitzroy Valley area and in their own homelands for generations. They still do it now when it comes to opening a sports carnival or a Kimberley Aboriginal Law and Culture (KALACC) meeting like the Yirriman project here recently. They show people their way of dancing. There are some songs and dances in the Aboriginal culture that require permission to perform because some of those dances are connected to Country. I was in a theatre play called Jandamarra (Bunuba Cultural Enterprises 2008). If you watch the show you’ll see how I dance. I wanted to do something similar but different in Jurrungu Ngan-ga. I can dance it in a different way but in my own style. I incorporate a song in Jurrungu Ngan-ga that I made up, its called Jalangurru Wiyi meaning: that’s my good looking woman.10

2.4. Feras Shaheen

Jurrungu Ngan-ga has made me think about my place here in Australia. During the development, a lot of the choreographic tasks that we were given involved reflecting on memories. Before I always used to say no, it did not feel like people were being racist. I always felt Australian, whatever that means. But now looking back on things I realise it was not the case. I now realise there have been many things that I was never aware of—they shaped me. So being a part of Jurrungu Ngan-ga has made me less accepting of discrimination. I understand the contemporary world better, the project has helped me understand the importance of these issues.11

2.4.1. Omid Tofighian

I noticed in your performances there is this kind of jittery, agitated physicality or response. What you were doing says so much about the critique of society, or of the modern condition, at the basis of this project. I was wondering if you could open up a bit about that, those movements and the thinking and feeling you express through your body?

2.4.2. Feras

I think my movement is quite like that naturally—like you said, stressed, agitated and anxious—because that is me personally. So I usually try to confront that when I dance, but this is a time when I do not have to hide it. This is the time when I can perform it.

2.4.3. Omid Tofighian

When I saw you performing your solo in the final scene of the show, I thought to myself that is a perfect artistic representation of people who have been ground down through the system, especially through bureaucracy. Most of the time in a detention centre a prisoner is not facing physically violent attacks in a direct conflict or fighting for something. A lot of the time the prisoners are just bored and sitting there, deep in thought and still trying to come to grips with something related to an application they have to fill out or waiting for some response from someone. Prisoners are just constantly waiting. And when I saw you performing the way that you did, I thought to myself that represents someone who is in the middle of this machine.

2.4.4. Feras

I feel like it is a visual translation of what is happening. And you see that in cultural dance, in Palestinian culture, but also in cultures of resistance. Most street dance that I have learned started from a situation. People went to clubs to express themselves because of something they were experiencing, and people were dancing on the street because of something that was going on. The stars that we know today are performing scenarios or periods of time, more than actual dance styles. The way I dance now comes from different dance styles like Hip Hop, house, popping and krump. And it was just my way of showing anxiety, but then Zach’s way or Benji’s way could be totally different because they have a lot of different tools within them. I definitely think the dance we do is a representation of the climate we are in.

2.5. Issa el Assaad

We were given a task during the development which was to make a confession. I brought up the fact that I am a Palestinian refugee who spent a lot of time trying to understand the meaning and constraints of this identity. I am also an architect. I have struggled with understanding what and where home is, but here I am designing the homes of others. So basically, I have an understanding of home, however, holding the title of a refugee has not allowed me to have a home. It hurts me when people question these things. If I am angry about the annexation of Palestinian land, I am angry about annexation because there is no justice in that. I am happy for Palestinians and Israelis to live together—we are all made of the same stuff after all. I want to share with everyone, but the situation is much larger than I can control alone. Growing up in a family of mostly women - actually, there are only two men in the family - taught me that the Palestinian woman’s role is to pass on the culture, they are the ones who pass on the traditions, they are the mothers, they are the educators, the dancers, the singers whilst the men in a Palestinian family are seen as the providers. The Palestinian woman becomes an important figure in the passing down of culture through generations. Except in a refugee camp, they do not have spaces to do that. In a refugee camp, there are no safe spaces for women. There are no safe spaces for children. There is no hub for them, no place to empower them and to create the future. I ended up visiting Lebanon and meeting with some women from a Palestinian refugee camp. Going back to your question, I am an architect that struggles with the meaning of home. And this is what translates into my scene speaking straight to the security camera in Jurrungu Ngan-ga, and this is why this project is really important to me. I never thought I would get a chance to share my experience in this way.12

2.6. Luke Currie-Richardson

I do not call myself a multidisciplinary artist or multi-dimensional artist, I call myself a storyteller. I think that refers back to my Indigenous heritage. We are the oldest living storytellers in the world. We have stories, we have song, and we have musicians, we have painters, telling stories is so ingrained in our DNA that I think what I am doing when practising my art is practising my traditional heritage through different media. I try and keep that practice alive as a storyteller.

You know during the development you said that being true to yourself is the biggest ‘fuck you’ to the system, the best thing you can do. And that is what I have tried to embody. It almost brought me to tears the other day during development, because identity is a huge thing and it came up in our talk with Behrouz. The identity issues associated with being a refugee and his connection to and knowing Country, even when he is displaced in whatever form the expression of that takes, that resonated with me a lot.

One of the things that brought me to where I am politically, or as an activist, is a memory, my favourite memory. I have this image of my mum and dad protesting back in the day. I framed it for Dad’s 60th recently.

My first memory of a protest with my brother in a pram. I was probably about three or four and I am walking amongst giants. For me, that is everything. A four-year-old looking up, cannot see anything but legs and asses. I was walking amongst giants. They are fighting the system. That image of me holding my mum’s hand. If I do write a book, I will call it Walking Amongst Giants.13

2.7. Miranda Wheen

This is my fourth project with Marrugeku but I feel there is something different with this one. Everything Marrugeku does is urgent, and this one is extremely urgent. All the projects feel like they are the right thing, right now. I think for the cast, the creatives, and everyone else involved, the work has real-time consequences. Even for me. White Australians also feel the consequences of this. Everyone involved in this project has skin in the game. It feels like we are on a knife-edge. Everyone involved is coming with a sense of urgency to contribute something, to change something. All of us are being changed by the project. What I see happening in the room is like a heightened state of bodily intelligence. It always upsets me when dancers or people involved in physical activity undercut their own knowledge because they articulate a huge amount by just moving and seeing our bodies move. So I think it is necessary to learn to appreciate that sort of knowledge, that physical knowledge. But the one thing I have realised after having worked with Marrugeku for a while is that in other dance contexts the emotional space or feeling is down on the list. But what we are creating is a space where feeling is considered to be a way of knowing, feeling becomes more important. What we rely on in the room is feeling and that should count as knowledge.14

2.8. Zachary Lopez

When I started training in contemporary dance I was learning contemporary Western techniques without any knowledge or any interest in learning about traditional Filipino dance or any other forms such as Indigenous dance. In dance school here you do not learn about yourself. I had a very particular idea of what dance and the beauty of dance was and how it could be performed in this body of mine. Then I started to realize that I was not getting leading jobs; of course, I was getting dance jobs and I was one of the lucky ones to be able to work in the leading white-dominated dance companies.

But I was getting the roles for predominantly shorter non-white men. I realised this early on and I thought that was what was available for me and I accepted it, I thought that is where I stand—I belong in the background, to be the fragile dancer that they require. That is what they wanted from this person, this body. So, throughout the last five years, I have been taking that role in multiple dance companies.

Then I started to ask myself questions. What is it about my skin colour? Similar questions brought back memories, trauma was coming back and I remembered being embarrassed about my skin colour and trying to scrub it off in the shower. It was about racism in Australia and acknowledging that I am a racist, as well. Structural racism, we are all complicit. I am part of that. And I am that myself because I do it to myself or I attack myself. I started to formulate ways to describe this in movement. I want to represent it in an innate way, using my own body language, not using a contemporary technique. As you have seen in the development for Jurrungu Ngan-ga we are all very different dancers. This is particular to Marrugeku, here I maintain Western techniques of contemporary dance and also develop my innate way of moving, which comes from my ancestors. I asked myself how can all that make a contribution in this context, to the ideas explored in this work? Things come back. Memories are going to come back. That is always part of Marrugeku’s work, they foster that history, which is completely different to anything I have ever done.15

2.9. Czack (Ses) Bero

The performance represents the system, the world we live in, how it manifests in us. You were explaining during the development about how the imprisoned refugees go to the doctor and then the information goes to the government. Well, for us that starts in school. Whatever the kids do at school gets written down in a kind of diary. Any little infringement gets written down in a program so that you build up a stat sheet. And then when they see signs of neglect or anything like that, maybe intergenerational trauma, the information builds and gets moved on to the next month. And then the next month. They grab it from there and go to the next moment, and the next moment. And that is how they take the children and move them to other families. When the missionaries came through the Torres Strait they came with a Bible and they came with alcohol and cigarettes; that is what they gave to my people. What do you want? Do you want the Bible? Do you want the alcohol and cigarettes? You can have them both at the same time. They set up the system from that.16

2.9.1. Omid Tofighian

One used to control the body, the other one used to control the mind. I found it compelling what you were saying about the actions in the school, the way they draw information from the children to then use against them. That for me ends up becoming like a bordering practice. It becomes like the creation of a border. The children are being prepared to end up in prison.

2.9.2. Ses

We have a failed system, Federal Parliament is failing and so is the school system. I do not know how we are going to fix it, we are just setting up our kids to fail at the moment. During our developments, I reflected on everything Behrouz said about Indigenous peoples and refugees and realised we are all connected. The violence in the refugee camps is about all of us. Indigenous people are still trying to write a treaty, still trying to get a voice in parliament, but we are not going to get that. Growing up in a city like Townsville [Far north Queensland] reveals so much, it is one of the most racist cities in Australia. You cannot say a thing, when you are walking around everybody is just watching you, all eyes are on you. Behrouz was saying that in detention even when he was sitting on the toilet there was someone outside waiting for him. I work in the primary school and all the non-Indigenous kids, whether they be Malaysian, Filipino, white Australian kids, they speak Aboriginal English with the Aboriginal students. But then when we go from Broome to Sydney, for instance, we see the realities of racism. And it is sad because the kids are heartbroken, they have never felt that way before.

Box 2. Performance Description 2. Scene 11: Say the Name.

Bhenji stands behind the wall, backlit, its

semi-transparent surface reveals her scantily clad limbs and the figures of

her fellow performers lingering behind the wall. Out the front on the stage,

a security camera scans the grey floor, its mechanical eye searching for the

source of her voice. The live feed from the camera is projected on the mesh

for the audience (as witnesses and voyeurs) into this space conceived as the

prison of the mind of Australia.

- [Bhenji bangs on the wall]

- Bhenji:

- Hello? Hello? Hey? Have you forgotten about me? She’s here! Helloooooo…What do you want with me? What do you want with my body? You’ve got me here right now! Have you forgotten about me? This is where you want me right? You are the one who put me in here [Camera still moving/looking].

- Is this all for me? This body. This trans-invisible body… Your big walls. Your big fucking walls?! How could you forget about her?It would be a shame if I just… [pushes at a secret portal in the wall] opened this thing! Come on girls.Thank you [To fellow ‘inmates’ Issa el Assaad, Chandler Connell and Emmanuel James Brown]. Thank you, Thank you.Is that all it was? Coming inside was easy! Are we done?.

- [Bhenji moving along the wall, the camera looking down on her and tracks her in the space while we the audience see the close up of her looking up projected on the wall above her head].

- Bhenji:

- Are you looking for me? You know I’ve always been here? But where are you? Are you on the inside now?

After posing for the camera and commanding the

imagined security guard to zoom into her suggestive positions, which are in

turn projected for the audience, she begins to tell the camera operator, and

by extension the audience, a story. She recounts the moments before a vogue

ball when she heard the news that Yolanda Jourdan, one of the trans icons of

the vogue movement had taken their own life. She remembers the ball beginning

and the moment one of the young trans-women took the stage to perform

Yolanda’s signature move… ‘paint your nails like Yolanda’. At this moment the

cast of eight performers take to the stage, ‘painting their nails’ like

Yolanda.

- Bhenji:

- When you say the name, don’t just say the name, hold the name, give it in the name…

- [The performers follow calling out the names of some of those who have died in custody on Australia’s watch till Bhenji turns to the security camera and calls out].

- Bhenji:

- Not a statistic, not another number,let me see my sister, my mother,feel her spirit and body in motion,sense her joy and sadness,hear her cries and laughterdon’t just say her namehold her namemark her namegive it in the namefrom the fingers to the chest,to her spins and then her dipsfrom the debke to the shake a legin the name, in the name, in the nameRIP Yolanda JourdanWho gave you your wings?I said Leiomy, Courtney, Sinia the list goes on and onSo many of those already gone and gone—Serve in peace Alloura, Angie, Venus, Octavia, cannot forget Crystal, Mother Labeija.You can take everything away from us but you can’t take away our joy. When you mix the resilience that comes from experience with joy, we are unstoppable.We, this family, this historyA never-ending ecology,A genealogy that cannot be forgottenNo rising seas or government policyCould take away from our mythologyLet me make this clear,we been here,never not leaving here,And in the words of Miss MajorI’m still fucking here.I’m still fucking here.I’m still fucking here.I’m still fucking here. (Ra 2021) Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Emmanuel James Brown, Zachary Lopez, Miranda Wheen, Bhenji Ra, Feras Shaheen, Chandler Connell, Issa el Assaad, Ses Bero & Luke Currie-Richardson in Jurrungu Ngan-ga. [Photo Abby Murray, Broome 2021].

3. Question: What Takes Place after Performance?

Omid Tofighian: Jurrungu Ngan-ga helps start urgent conversations and gets people to act on them and respond in practical ways. It really heightens the sense of responsibility. What needs to take place after the performance?

3.1. Bhenji

This is a rally because it engages bodies. Jurrungu Ngan-ga is a really important form of protest. The ideas and the energy, the vision, everything that bursts out. I think it has the potential to go on for years and years, and actually encourage other spaces to start to think about actions and the body. I think at the same time it also requires organizing. That is what we have to do after this project is over. And that is when we need to work together to make things happen. So it is not static. It actually keeps moving, it is dynamic as it is dance and there is no end to it. I have started to introduce myself as an abolitionist. I am an artist and abolitionist, there is no need for anything else. If you break it down abolition works, you are speaking to disability justice, to racism, to transness, to class division, to deep and real relationship building. It just all keeps flooding through.

3.1.1. Omid Tofighian

Okay, how did you get introduced to abolitionism? When did it first come into your atmosphere?

3.1.2. Bhenji

I would always see the word but I did not get what it means. It is such a strong word, as well. It always felt really powerful. I was probably an abolitionist without knowing, when I was in high school I went to the Philippines, during my last year. When I was there my auntie was doing work in the women’s prison in Mandaluyong, inner-city Manila. I offered to teach dance classes to the women. I built a relationship with the women. In that space I remember always being watched by the guards who were checking on what we were doing, and I remember I met some women from Africa, they had been there for about ten years—the prison system is so corrupt. I was asking questions, but I did not know why because I was not going to get answers. Who is her lawyer, does she even have a lawyer? Why is no one assisting, how long will she have to wait? When is her next court case? I discussed the histories of the dance form vogue with Rachael and then brought it up with the Jurrungu Ngan-ga team. I have a practice in voguing, a dance practice that started on Rikers Island, a prison just off Manhattan. I was told by my first teachers that voguing started in the jail system and with incarcerated gay and trans-Black folk. They would mimic magazines which would then become posing, and then that custom came back into the community, it cycled back into the community. It is so crazy how everything is linked. The jail system has been such a huge part of the LGBTQ+ community for so long, people in the community move between those spaces all the time.

3.2. Chandler

I am only 22 years old, and some people say I need to do this kind of work for the next generation so they can make the change. I am pretty sure my grandparents were saying that they want to change things for their own generation, as well. I keep asking myself, what do we do? We have to make the change because we are at a point now where they want us out. This show has really let me come in and take charge. I have to make change because I cannot wait for change anymore, especially with what is happening. I use every cultural lesson I have been taught because that is what we are given in our culture to help get us through things. Stories are vital, and we are taught humility. I have to use these stories just to get by every day, and then I bring them into my dance practice. Of course, I have to be careful how I share my culture because I am not here to give my culture away. I am here to say: we are taking it back. This is in our culture. In Jurrungu Ngan-ga, I am determined to tell the truth because our truth is denied constantly.

3.3. Omid

During the development, you explained the treatment of your people when they are incarcerated. Immediately I thought about how this kind of treatment, this kind of punishment, this kind of control does not end with prison. It is everywhere. It happens on the outside, as well. So I am interested in what you have to say about punishment and control both inside prison and outside prison, how they are the same and how they are connected

EJB

I was speaking about many people in our communities. We are put in prison for so many different things. When people are locked up especially in the chook pen, in solitary confinement, it is like a different world. This means getting permission from the screws, the prison guards, for everything. Like if someone wants to make a phone call. But when they come outside it is just the same thing. Our people find they have new issues with their family, they have trouble readjusting, and then there is the trauma. And also there are still things there from the past, from what they went through in life. These things that are controlling them stay with them and everyone can feel it. That is entrapment—our people are trapped, our people are still prisoners. When people are released from prison they are still in the system. They are not free. Behrouz talked to us during the development and it connected with the experiences of my people—it is the same deal. We are also branded like cattle. We are going in the direction where everyone will be watched using technology. This came to mind when Behrouz was talking and you were reading from the book. This is the way for many of my fellow Countrymen. They are still trapped. It is a cycle. When they take people to prison they do not change. People do not change there, children as well. The cycle never breaks.

3.4. Feras

This affects all of us. We may think we are not part of it, but we are always part of it. I was naive for a long time, I was not turning my back on it, but I guess I was looking for other things rather than looking at my own position and culture. And I am glad that now I have slowly started considering it in depth, both through dance and talking to family members more. I owe that to this project… the majority of it.

3.5. Issa

In a previous architecture project I came across a documentary (Kingdom of Women in Ein El Hilweh (2010) directed by Dahna Abourahme) that led me to work on a project in Ein El Hilweh, one of the biggest living Palestinian refugee camps in Lebanon which I mentioned earlier. The film documents the community and organising spirit of the women during an invasion, how they were able to rebuild the camp and provide for their families while their men were held captive. The spirit of the women as a collective is what keeps the viewer inspired. And you were talking about how people modify and modify over and over again. In spaces where people are oppressed, they are more inclined to modify, more adaptive to change because they have to, they have to recreate it. They are basically inventors. They have to reinvent how things work. And doing that is so exciting for them; yes, they are being oppressed but they resist, so they have to rethink things and recreate.

No Friend but the Mountains was one of the books I have read the fastest because it connected to so many themes and topics I experience in my own life. And then I came into the dance space only to see we were working on this book, it was exciting. I feel that as a Palestinian architect I need to challenge myself so much in order to make a mark in the world and to be acknowledged. But then I need to find ways to share the work and say what I want to say. If you are invisible and you are not heard it is so hard to get your message across. That is the direction I want to take things.

3.6. Luke

As a storyteller, I integrate all my diverse art practices because my main practice is the empowerment of my people, first and foremost. Empowerment, and documenting my culture within contemporary society. But I also want to be that positive representative of my people, which I did not get to see on stage or on TV, in magazines, or in the very limited social media back in the day. Consider the Black Lives Matter movement, stopping black deaths in custody. All that stuff happened 50 years ago. It is just that it is being filmed now. And now I am documenting it. I think it is really important for people in the arts to stay grounded and to stay true. The stories have been told before; I am just doing it in a different medium. I think my biggest life goal, or my purpose, is being the best ancestor that I can be in my time.

3.7. Miri

I see my role in Marrugeku at the moment as one of responsibility. For the last fifteen years, especially the last few years, I was like a sponge. I absorbed a lot of stuff. Now I have this responsibility to bring it out. I feel I have a responsibility that is why I am here to help produce this amalgamation and meeting of different physical practices. But of course, the physical practices are totally bound up in people, and life, and culture, and politics.

3.8. Zach

Now that I do have the platform to be able to showcase my culture, my voice, there is strength to that. I know that my face being shown on stage, or my face being shown on posters, would move people in the community and strengthen everyone. That is what keeps you doing it. This is probably the only contract that I have worked on that specifically talks about the experience of racialized people, incarceration, and similar issues. I make sure that I delve into mainstream works as well so people do not assume that all we can do is validate ourselves and our history, and experiences.

They put you into a box again. I just make sure I delve into other things that you would not normally see me as part of, like mainstream dance companies. I have to make sure that I am in that scene because it is so white-dominated. There is this elitism in dance, and it is associated with the style of dance.

This particular collaboration with you has been really amazing, I like to think about the longevity of this work in ways that I never have. Usually, once a performance is done it is in the past. It does not continue in any form if there is no substance to it, if it is just dance work. With Jurrungu Ngan-ga I am really excited to express this in multiple forms. Like you said, publications or discussions. It is always going to continue.

3.9. Ses

I think people who experience oppression need to collaborate—Jurrungu Ngan-ga reflects this need. We are all up against the same thing. We are all up against the system, the system that was built to divide and conquer all of us. Jurrungu Ngan-ga is a powerful story, everybody needs to see it. It is a story that we are telling. It is not just for Indigenous peoples, not just for refugees, it is for everyone. It is especially for people who feel suppressed, who are minoritised. We are the ones driving this. We are a force. Jurrungu Ngan-ga is education. We can perform this inside schools, it can talk to kids, to students inside the university, it can talk to many people, make students change their minds before they go out into the real world. Jurrungu Ngan-ga teaches you to accept other people’s differences because my story could be the same as the next person in a different country. We are trying to show what the system is doing to everyone, how it marginalizes people.

Box 3. Performance Description 3. Scene 13: Resistance of the Bodily Archive.

- Bhenji: I’m still fucking here. I’m still fucking here. I’m still fucking here.

As vogue music rises under Bhenji’s voice and

drowns her out she begins voguing atop the stage, her precise arms moving at

turbo speed. Soon she dips and rolls off the stage which is immediately taken

by Feras Shaheen and Issa el Assaad who perform a fusion of debke and house

dance, amidst the cheers of the other dancers who surge around the platform.

They too are soon replaced by Chandler Connell and EJB as they stamp their

feet into the mesh of the platform as if it were the dirt in their homelands.

Although coming from different parts of the country they share aspects of

their own cultural archive through movement that celebrates the fact that

they too are ‘still fucking here’. The scene we call ‘Resistance of the

Bodily Archive’ feeds on the emotional energy of the sudden culturally driven

dramaturgical pivot in the work as it swivels from intense sadness and anger

to joy and resilience, all to the pulsating vogue soundtrack. The security

camera continues to survey the scene which by now resembles an uprising in a

prison. Chandler and EJB perform an echo of a scene from a recent revolt in a

juvenile detention centre where young Indigenous inmates escaped to a roof

and danced their traditional dance as a form of protest to the media filming

from helicopters. The unmistakable rhythms of Torres Strait Island dance

performed by Ses Bero and Luke Currie-Richardson take over followed by Disco,

Martha Graeme slow-motion modern dance moves and a Filipino princess dance

led by Bhenji, all shared by the performers from their own ‘bodily archive’. Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Bhenji Ra, Emmanuel James Brown, Miranda Wheen, Zachary Lopez, Chandler Connell, Feras Shaheen, Issa el Assaad, Luke Currie-Richardson & Ses Bero in Jurrungu Ngan-ga. [Photo Abby Murray, Broome 2021].

4. The Collective Power of Performance—Abolitionist Futures

Jurrungu Ngan-ga is a radical space where Indigenous, refugee, migrant, trans-gender and settler bodies engage with each other and work towards abolition. Abolition is not only about abolishing prisons, it is about abolishing all forms of violence against life, all forms of oppression. The purpose of this project is not to continue bordering; in our critique, we do not isolate the prison-industrial complex or the border-industrial complex from other forms of bordering, other forms of division and abuse. Jurrungu Ngan-ga is a form of de-bordering that is dedicated to power, polyphony and processes of abolition.

Drawing on critical discussions across activist and performance contexts, this article amplifies the importance of intersectionality for political dance and art projects. We illustrate the generative, disruptive, and affective power of performance as resistance to colonial oppression and interlocking forms of violence. The performers in Jurrungu Ngan-ga embody, perform and define intersectionality in an Australian context. In the above interviews, the artists have proposed that activism can be more sexy and irresistible (Ra); new storytelling is critical for empowerment (Currie-Richardson); that displacement, exile and containment can generate hope and creativity, pride and power (el Assad and Shaheen); and —through his design—that structures reveal as well as conceal, and are just constructions that can be taken down (Abdullah). Together, the artists and cultural leaders of Jurrungu Ngan-ga share new ways of knowing. That is, seen through the lens of Indigenous understandings of Country, boundaries are sites that can be reclaimed and reimagined through cultural negotiation, and as such, are always and already understood as multi-vocal and multi-temporal.

Jurrungu Ngan-ga aims to address violence and cruelty in society; protests can do so much, politicians can do so much, policy changes can do so much. Through the production’s choreography, dramaturgical and intersectional construction, design and casting the work makes an important contribution to these debates by changing the narrative about who is actually in prison within Australian society.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: D.P., O.T. and R.S.; writing—original draft preparation: O.T. and R.S. with the interviewees: C.B., E.J.B., C.C., L.C.-R., I.E.A., Z.L., B.R., F.S. and M.W.; writing—review and editing: D.P., O.T. and R.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Edited by Dalisa Pigram. Interview excerpts: Czack (Ses) Bero, Emmanuel James Brown, Chandler Connell, Luke Currie-Richardson, Issa el Assaad, Zachary Lopez, Bhenji Ra, Feras Shaheen and Miranda Wheen.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Throughout this article, we have made every effort to acknowledge the language group or Indigenous Nation that each Indigenous speaker, writer, or artist uses to describe themselves. We have also respected their preferences in identifying the current orthography for each language group. |

| 2 | The research of Jurrungu Ngan-ga also engaged with Tofighian’s translator’s reflection essay from the book No Friend but the Mountains, which introduces the ‘two islands’ thought experiment. See (Tofighian 2018). |

| 3 | Settler costume designer Andrew Treloar’s design focuses on the ambiguity of those who are locked away and those who are free and responds also to former inmate of the juvenile justice system Dylan Voller and Behrouz Boochani’s descriptions of the clothing of those incarcerated and those working for corporations within carceral systems. |

| 4 | The interviews with the cast were conducted in person or via zoom in October 2020 during a rehearsal period undertaken ‘together/apart’ in both Sydney and Broome because of the closed state borders imposed in Australia due to the pandemic. The interview excerpts were later edited by each cast member. |

| 5 | Marrugeku has come to identify the role of the cultural dramaturg as a cultural expert working alongside the performance dramaturg in each of the company’s productions. This acknowledges the distinct expertise, logics as well as cultural, philosophical and practice-led understandings that intersect in the company’s intercultural and Indigenous performance making. In Jurrungu Ngan-ga the cultural dramaturgs include Yawuru leader Patrick Dodson, Behrouz Boochani and Omid Tofighian who work alongside Flemish dance dramaturg Hildegard De Vuyst. |

| 6 | Yawuru leader, Professor Mick Dodson, explains that in referring to Country, Indigenous Australians might mean ‘homeland’, or ‘tribal or clan area’ and that this might mean more than just a place on a map. according to Dodson, for Indigenous Australians: “Country is a word for all the values, places, resources, stories and cultural obligations associated with that area and its features. It describes the entirety of our ancestral domains” (Dodson 2009). |

| 7 | Pacific Solution 1: 2001–2008; Pacific Solution 2: 2012–2013 and Operation Sovereign Borders: 2013–present. |

| 8 | Bhenji Ra is a trans-gender Filipinx-Australian interdisciplinary artist whose practice combines dance, choreography, video and installation |

| 9 | Chandler Connell is a Wiradjuri/Ngunnawal man and a young emerging dance artist based in Sydney. |

| 10 | Emmanuel James Brown is a Bunuba/Walmajarri/Gooniyandi/Wangkatjungka actor and traditional dancer who lives in Fitzroy Crossing, in the Kimberley region of Western Australia. |

| 11 | Feras Shaheen’s art practice spans performance, semiotics, street dance, readymade art and digital media. Feras was born in Dubai (United Arab Emirates) to Palestinian parents and moved to Sydney at the age of 11. |

| 12 | Issa el Assaad is a graduate of architecture and a multi-disciplinary artist. Born as a Palestinian refugee in the United Arab Emirates, he is now based in Melbourne Australia. Originally trained within an Arabic folklore dance tradition, Issa only pursued professional dance specifically for Jurrungu Ngan-ga. |

| 13 | Luke Currie-Richardson is a descendant of the Kuku Yalanji and Djabugay peoples, the Mununjali Clan of South East Queensland, the Butchulla clan of Fraser Island and the Meriam people of the Eastern Torres Strait Islands. He is a dancer, photographer and social media influencer. |

| 14 | Miranda Wheen is a Sydney-based freelance dancer of English and Irish descent. She danced heavily pregnant with her second child during the development of Jurrungu Ngan-ga. |

| 15 | Zachary Lopez is a Filipino-Australian contemporary dancer, performer and emerging choreographer based in Sydney. |

| 16 | Czack (Ses) Bero is a proud Indigenous man from both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander background coming from the Kunjen people of Western Cape York and the Erub and Meriam people of the eastern part of the Torres Straits. His performance draws on both his traditional and contemporary dance trainings. |

References

- Boochani, Behrouz. 2018. No Friend but the Mountains: Writing from Manus Prison. Translated by Omid Tofighian. Sydney: Picador. [Google Scholar]

- Bunuba Cultural Enterprises. 2008. Perth International Arts Festival. Jandamarra. Perth: Black Swan State Theatre Company. [Google Scholar]

- Dodson, Mick. 2009. The Distinction between ‘country’ and ‘Country’. Speech to the National Press Club, Canberra. Reconciliation Australia. February 17. Available online: https://www.reconciliation.org.au/acknowledgement-of-country-and-welcome-to-country/ (accessed on 27 October 2021).

- Galbraith, Janet, Hani Abdile, Omid Tofighian, and Behrouz Boochani, eds. 2021. Writing through Fences: Archipelago of Letters. Special Issue of Southerly. Blackheath: Brandl & Schlesinger. [Google Scholar]

- Meldrum-Hanna, Caro, and Elise Worthington. 2016. Australia’s Shame. Sydney: Four Courners for ABC TV. [Google Scholar]

- Ra, Bhenji. 2021. Say the Name. In Marrugeku’s Jurrungu Ngan-ga. Choreographed by Dalisa. Pigram, Directed by Rachael Swain. Broome: Arts House. [Google Scholar]

- Tofighian, Omid. 2018. No Friend but the Mountains: Translator’s Reflections. In No Friend but the Mountains: Writing from Manus Prison. Translated by Omid Tofighian. Sydney: Picador, pp. 359–74. [Google Scholar]

- Tofighian, Omid. 2021. Horrific Surrealism: New Storytelling for Australia’s Carceral-Border Archipelago. In Marrugeku: Telling That Story—25 Years of Trans-Indigenous and Intercultural Performance. Edited by Helen Gilbert, Dalisa Pigram and Rachael Swain. Wales: Performance Research Books, pp. 306–25. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, Alexis. 2019. The Ancient Library and a Self-Governing Literature. Sydney Review of Books. Available online: https://sydneyreviewofbooks.com/essay/the-ancient-library-and-a-self-governing-literature/ (accessed on 22 June 2021).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).