Abstract

This article explores a creative project entitled Performing Liberation which sought to empower communities with direct experience of incarceration to create and share creative work as part of transnational dialogue. One of the aims of the project was to facilitate creative dialogue and exchange between two incarcerated communities: prisoners at Auckland Prison and prisoners at San Quentin Prison in San Francisco. Written using autoethnographic methods, this co-authored article explores our recollections of key moments in a creative workshop at Auckland Prison in an attempt to explain its impact on stimulating the creativity of the participants. We begin by describing the context of incarceration in the US and New Zealand and suggest that these seemingly divergent locations are connected by mass incarceration. We also provide an overview of the creative contexts at San Quentin and Auckland Prison on which the Performing Liberation project developed. After describing key moments in the workshop, the article interrogates the creative space that it produced in relation to the notion of liberation, as a useful concept to interrogate various forms of oppression, and as a practice that is concerned with unshackling the body, mind, and spirit.

1. Introduction: Performing Liberation

In September 2019, incarcerated participants at Auckland Prison Paremoremo attended a short creative workshop that was offered over two afternoons. During the first session, Reginold Daniels, a formerly incarcerated Black educator and arts facilitator from the US, led the mainly Indigenous Māori participants through an exercise. The men were asked to stand in a circle and chant the word ‘dream’ repetitively. During the chanting, Daniels recited a poem entitled ‘Dream’ that he had previously written and performed as part of a theatre production exploring the experience of incarceration. The chanting and the recitation of this poem had a profound effect. Something happened within the confines of the prison meeting room where the participants gathered. A space was opened up that was personal, emotional, and moving. Daniels was moved to tears. Other participants held back tears while maintaining the chant and expressed their sincere gratitude to Daniels for sharing his words after the poem had been completed. Shortly after this, the participants were given a series of questions about liberation composed by Antwan ‘Banks’ Williams, who was an incarcerated individual of San Quentin prison. At the workshop session the next day, the incarcerated participants shared their responses to the questions on liberation. They reported that they had been inspired to stay up late the night before to write poems, songs, and stories. Months later, in reflecting on the efficacy of the workshops in helping to activate the creativity of the prisoners, we kept returning to that moment on the first day, when Daniel’s shared his poem to the communal chanting of the men. This essay attempts to make sense of this moment and explore its significance as an act of liberation.

The workshops offered by Daniels were part of Performing Liberation, a creative project that aimed to empower communities with direct experience of incarceration to create and share creative work as part of a transnational dialogue. A central politics informing this larger project was the need to centre the experiences of incarcerated communities themselves so that they are empowered to lead creative explorations without the reliance on outside artists or educators. The project aimed to facilitate creative dialogue and exchange between two incarcerated communities: prisoners at Auckland Prison and prisoners at San Quentin Prison in San Francisco. A central provocation for the project was the question: What does Liberation feel like? The project sought to test the human limits of reaching for understandings and creative explorations of liberation despite the constraints of confinement and distance.

The idea for the project emerged after Dr Rand Hazou met with members of the Artistic Ensemble at San Quentin Prison in July 2019. The Artistic Ensemble is a troupe of sixteen diverse men in prison working with five outside members who use creative collaboration with language, sound, and movement to explore social inequalities. Hazou brought to the ensemble some short image theatre exercises as well as a concern to explore how the experience of incarceration might colonise the self so that the segregation, isolation, and confinement that carcerality imposes can become internalised and normalised. This provoked a short discussion about general notions of liberation and how this might involve resisting or refusing the normalisation of behaviours and responses imposed by carcerality. As a result, a member of the Ensemble, Antwan ‘Banks’ Williams, supplied a list of questions and creative prompts on the theme of ‘liberation’ that he asked Dr Hazou to share with Prisoners at Auckland Prison. The questions shared by Banks included the following:

- Tell me what is liberation?

- Does it look like you or I?

- Tell me if it is worth what you did?

- Tell me if liberation goes by another name?

- Does it change, stay the same, live forever, or die in vain?

- Tell me please tell me?

- I want to know if your shackles and chains are visual?

- Tell me are they literal, biblical?

- Tell me if liberation starts within?

- If so, tell me you’ve freed your mind?

- Tell me time is a figment, tell me your cell’s dimensions?

- Tell me liberation can come from forgiveness?

- Tell me liberation is near?

- Tell me liberation is here?

- Tell me liberation can’t disappear?

- Do you find liberation in the faces of people you love?

- Does liberation look like movements of silence?

- If so, how often are you quiet?

This article will explore the sharing of these questions and the space for creative exploration that opened up during the workshop at Auckland Prison. Written using autoethnographic research methods, this co-authored article explores our recollections of key moments in the workshop to explain its efficacy in stimulating the creativity of the participants. In writing this article, rather than focusing on reporting the experiences of the workshop participants themselves, we focus on our own personal perspectives as the workshop facilitators and as educators and creative producers located ‘outside’ the prison complex yet nevertheless concerned with creating opportunities for those ‘inside’ to participate and learn through the arts. The focus on our own perspectives in this article is also an attempt to avoid professing to speak for and voice the experience of those inside and therefore circumvent engaging in cultural colonisation that either extracts the experiences of the prison participants for our own advancement or imposes our interpretation as outside facilitators on the incarcerated participants. Instead, in this article, we reflect on our own recollections of the key moments in the workshops that we think helped open up a space for creativity. We explore this creative stimulation in relation to the notion of liberation, as a concept that interrogates various forms of oppression, and as a practice that is concerned with unshackling the body, mind, and spirit. We begin by describing the context of incarceration in the US and New Zealand and suggest that a concern for mass incarceration connects our seemingly divergent geographical locations. After outlining the methods that have informed our approach to writing this article, we provide a short outline of the creative contexts at San Quentin and Auckland Prison that the Performing Liberation project builds on. The article then describes two key moments during the workshop at Auckland prison; the pōwhiri or Indigenous Māori cultural welcome that the men performed, and the exercise that was facilitated by Daniels involving the group chanting and the recitation of a poem. We interrogate the creative space that these two moments produced in relation to the concept and practice of liberation and conclude with some reflections on our own ‘blind spots’ in attempting to facilitate the workshops and the larger collaborative project.

2. Context: Global Incarceration

The Performing Liberation project aimed to facilitate creative dialogue and exchange between two incarcerated communities: prisoners at Auckland Prison and at San Quentin. While these two communities may seem geographically, historically, and culturally disparate, they are nevertheless connected by global mass incarceration and a carceral logic that disproportionately impacts racial minorities.

The United States has the highest incarceration rate globally with 639 per 100,000 of the US population. In comparison, New Zealand’s incarceration rate is 188 per 100,000. Both rates are higher than the world average rate of 155.3 per 100,000 (World Population Review 2021). As of 2020, almost 2.3 million people were incarcerated in the United States. At least one in four people who go to jail will be arrested again within the same year—often those dealing with poverty, mental illness, and substance use disorders, whose problems only worsen with incarceration (Sawyer and Wagner 2020). Significantly, this imprisonment rate is impacted by racial disparities, with Black Americans making up 40% of the incarcerated population despite representing only 13% of U.S residents.

In New Zealand, the racial disparities imposed by carceral logics are similarly stark. According to the Department of Corrections, in March 2020, New Zealand’s prison population stood at 9253 (Department of Corrections NZ 2020). This incarceration rate disproportionately impacts indigenous Māori. Māori constitutes more than half the prison population (Department of Corrections NZ 2020), despite being only 15 per cent of the overall population (Stats NZ 2015). The over-representation of Māori in corrections has been linked to the ongoing legacy of colonialism (Jackson 2017; McIntosh and Workman 2017).

Within the context of mass incarceration and surveillance, the interrogation of the origins of the carceral state and the imposition of a punitive and confining logic is a central concern. In Ruby Tapia’s definition, the carceral state encompasses:

The formal institutions and operations and economies of the criminal justice system proper, but it also encompasses logics, ideologies, practices, and structures, that invest in tangible and sometimes intangible ways in punitive orientations to difference, to poverty, to struggles to social justice and to the crossers of constructed borders of all kinds.(Tapia 2018)

Colonial legacies of disadvantage, over-policing, and over-incarceration continue to disproportionately affect Indigenous peoples in settler-colonial nations such as the US, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand (Cunneen and Tauri 2016). In the US, White supremacist attitudes and government policies underpinning these systems are described by Michelle Alexander (2010) as ‘the new Jim Crow’. Alexander describes the multifaceted, lifelong discrimination and disenfranchisement that affect people who are branded ‘felons’. Alexander explains how incarceration, once it is imposed upon financially disadvantaged people, creates a permanent underclass, and a subordinate status that cannot be worked out, lived out, or made amends for, but serves a specific purpose of keeping people of colour contained, mentally, physically, and spiritually.

In attempting to facilitate creative dialogue between two incarcerated communities, this project aimed to empower those with direct experience of incarceration, who despite their geographic distance, might be able to share creative work as part of a transnational dialogue. The project sought to test the human limits of reaching for understandings and creative explorations of liberation despite the constraints of confinement and distance.

3. Method: Our Approach to Writing This Article

This article is co-authored using autoethnographic and practice as research methods. As researchers/practitioners we were engaged participants of the Performing Liberation workshops at Auckland Prison and both of us possess knowledge of working in carceral spaces as creative facilitators. One of the authors also possesses personal experience of incarceration, having spent time inside. In situating ourselves in this way, we acknowledge that claims of subjective bias do not arise from the level of ‘immersion’ in a cultural setting, but rather from a researcher’s or scholar’s ambiguous placement in a field of inquiry (Coffey 1999). The motivating factor in writing this article was to try and understand our experience of the workshops facilitated at Auckland Prison. Since 2017, Hazou had been involved in a series of creative engagements at Auckland prison (see Section 4.2 below). He had invited both Dr Daniels and Dr Amie Dowling from the University of San Francisco to New Zealand to participate in an international symposium co-hosted by Massey, Auckland, and Griffith Universities entitled the ‘Performing Arts and Justice Symposium’. The symposium was attended by international and local researchers, activists, artists, and community educators to discuss and share knowledge about the role of the arts and culture in decolonising corrections. As part of their commitments in New Zealand, Daniels and Dowling offered to meet with incarcerated individuals at Auckland prison and to facilitate a workshop to help establish connections with the incarcerated community in San Francisco. The workshop was organised by Hazou working with Auckland prison staff and drew on his previous relationships with senior managers and prisoners. The twelve prison participants that took part in the workshops were from diverse cultural backgrounds, experiences, and ages. Five of the participants identified as Māori, four were of Pacific Island origin and the remaining were Pākehā or New Zealanders of European heritage.

The resulting workshops were short—conducted over two afternoons and conceived as a starting point that might develop into longer and more sustained creative collaborations in the future. Yet, while brief, the workshops nevertheless created a personal, emotional, and powerful moment that seemed to open up a creative space that helped catalyse the participants’ creativity. The participants reported that they stayed up late in their cells following the first workshop, writing and composing poems and song lyrics in response to the questions on liberation that were provided as a provocation. In attempting to make sense of the workshop and the creative responses, the authors have continued to return to the recitation of Daniels’ poem and the chanting as a critical moment that has held enduring meaning for us. The co-authoring of this paper has taken the form of a series of online discussions through which we have attempted to recreate and document this moment from the workshop. In this way, our writing is informed by autoethnographic research that draws on experience, emotion, and subjectivity for its material. As John Freeman states, autoethnographers ‘write their experience into narratives and are themselves key participants in the research, and often also its subject’, thus ‘the idea of research as a neutral process is abandoned in favour of a self-reflective form that explores the researcher’s perspective on the subject in question’ (Freeman 2015, p. 2). In the following sections, we first provide a brief sketch of the creative contexts at San Quentin and Auckland Prison on which the Performing Liberation project developed. We then describe key moments during the workshop session at Auckland Prison which we then analyse in relation to the notion of liberation and Bell Hooks’ (1994) conception of an ethic of love. Before analysing the workshops, the next sections attempt to provide a context for the creative interventions at both prison settings and to highlight the creative vocabularies and histories that persist at these locations which informed the workshops.

4. Creative Contexts: Theatre and Creativity in Prison

The resulting theatre workshops facilitated at Auckland Prison sit within a body of work most often referred to as ‘Prison Theatre’ (Thompson 1998b). Theatre in prison is most often defined in terms of participatory programs carried out by professionals who enter into criminal justice settings to carry out theatre workshops and projects with prisoners (Balfour et al. 2019). Prison Theatre is often framed in terms of prevention, rehabilitation, or reintegration and often comprises a wide range of practices (Hughes 2005, p. 8). These include theatre made by prisoners for prison communities, professional productions staged for prisoners, as well as productions with a mixed company of professional actors and prisoners which may be open to a public audience who are invited into prison (McAvinchey 2011, p. 55). Recent scholarship extends the discussion of Prison Theatre to consider ‘carcerality’ as a pervasive neoliberal strategy and the role theatre and performance can play in highlighting the rights of those experiencing state-sponsored control, confinement, and exclusion (Woodland and Hazou 2021). In this article, we also extend the discussion of Theatre in Prison to consider other forms of performance and creativity that emerge from and speak to the specific cultures of the incarcerated communities that the Performing Liberation project was engaging with. In both the US and New Zealand contexts and particularly among Black and Indigenous Māori communities, oral performance traditions such as storytelling, speaking, poetry, song, and rap are artforms that hold cultural currency. These have also been supported through creative endeavours that support dance and movement. The Performing Liberation project built on recent creative endeavours in both contexts to facilitate creative engagements that spoke directly to the cultural realities of the communities involved. The following sections provide a brief overview of the creative endeavours at San Quentin and Auckland Prison to better situate the Performing Liberation project. Notably, an exhaustive and definitive account of these creative contexts lies beyond the scope of this article. Rather, the brief sketch acknowledges the creative disciplines and histories on which the Performing Liberation project builds.

4.1. Creative Endeavours at San Quentin

One of the earliest recorded examples of Theatre in Prison at San Quentin was a visit by Sarah Bernhardt in 1913. The stage and screen star reportedly performed an extract from the production Une Nuit de Noël to around 2000 prisoners (McAvinchey 2011, pp. 61–62). Four decades later, in 1957, the Actors Workshop presented their famous production of Waiting for Godot directed by Herbert Blau. A year later, the prisoners created their own troupe, the San Quentin Drama Workshop, which ran from 1958 to 1965 (Dembin 2019). Famously, it was during this period that Johnny Cash played his first-ever prison concert which was staged at San Quentin on 1 January 1958. The following year, Johnny Cash’s live recording of the album At San Quentin (Cash 1969) reached number one on the country music charts, remaining there for twenty-two weeks (Geary 2013).

In 2013, artists and educators Amie Dowling and Freddy Gutierrez delivered a series of dance theatre workshops at San Quentin which led to the establishment of the Artistic Ensemble. Today the group comprising mainly prison performers who are supported by outside artists, create dance and physical theatre productions that are presented inside the prison to audiences comprised of currently incarcerated men and invited guests from the outside. Waterline (Artistic Ensemble 2014) combined contemporary dance and dramatic monologues written by the prison participants based on their life stories. The various stories were connected by the image of water ‘both stagnant and fast-paced’ which served as a figurative thread and a metaphor for life in all its forms (Winfrey 2014). Faultline (Artistic Ensemble 2015) explored the geological weight, time, and pressure of incarceration. In this piece, the collective 334 years served by the Artistic Ensemble members were explored as a series of daily prison rituals using physical theatre, movement, and dance (Dowling, n.d.). ‘What makes us visible?’ and ‘Is it possible not to disappear?’ were the opening questions that framed the production Ways To Disappear (Artistic Ensemble 2016). The production explored how the system of mass incarceration makes people’s names disappear under numbers, and makes people disappear behind walls that separate them from family and friends. Using poetic language and physical choreography, the production demanded that audiences ‘see’ the prison participants as ‘fathers’, ‘brothers’, and as ‘artists’ (Artistic Ensemble, n.d.). Most recently, Site Unseen (Artistic Ensemble 2018) used dance, song, rap, and spoken-word to explore how space is occupied and how it can be occupied in new ways (Haines 2018).

In recent years, the establishment of a digital media centre at San Quentin has also provided incarcerated individuals with opportunities to explore creative pursuits in other media such as music production and radio reporting and programming. This has led to the award-winning podcast Ear Hustle, which current and past inmates produce at San Quentin Prison, that broadcasts their everyday stories and experiences to a public audience (Cecil 2020).

4.2. Creative Endeavours at Auckland Prison

While the effort to facilitate transnational dialogue between two communities disproportionately impacted by incarceration is an innovative aspect of this project, there is precedent for this approach. In 1979, a Black theatre troupe from London called Keskidee toured the north island of Aotearoa New Zealand, visiting community centres, marae (traditional Māori meeting places), and prisons. Named after a small Guyanese bird renowned for its resilience, the Keskidee troupe consisted of Black British, African-Caribbean, African-American and African performers including a group of Rasta musicians. As Robbie Shilliam explains, the national tour, which was called Keskidee Aroha, was a project of cultural self-determination and an effort to ‘translate Black into Brown liberation on the colonial stage’(Shilliam 2011, p. 81).

While in New Zealand the troupe was hosted by Whakahou, a community group based in the South Auckland suburb of Ōtara, where members of the troupe workshopped with Maranga Mai—the first agitprop Māori theatre group (Shilliam 2015, p. 103). A particularly poignant performance was staged at the Arohata Women’s Prison and comprised a scene from Alex Baldwin’s If Beale Street Could Talk, in which a young woman describes breaking the news of her pregnancy to her incarcerated boyfriend (Shilliam 2015, p. 96). A documentary film of the tour also entitled Keskidee Aroha (1980), co-directed by Martyn Sanderson and Merata Mita, documents the group’s performance at Auckland prison, Paremoremo (Mita and Sanderson 1980).

Forty years after the Keskidee Aroha visit to Auckland Prison Paremoremo, the Performing Liberation project sought to again provide opportunities for two transnational communities most impacted by carcerality to be involved in creative dialogue. The workshops at Auckland prison followed a series of recent creative engagements. In May 2017, Rand Hazou and Derek Gordon delivered the Theatre Behind Bars programme which offered six introductory theatre workshops to participants including storytelling, physical theatre skills, and mask work. These workshops helped to generate interest within the prison for continued engagement in theatre projects. As a result, in June 2017, the Artistic and Managing Director of the Vancouver-based company Theatre for Living David Diamond was invited to Aotearoa to work on a Forum Theatre project at Auckland Prison. The project resulted in three short plays performed as an interactive forum theatre event to a small audience of invited guests made up of visitors and Auckland Prison staff. Forum Theatre involves a particular approach that presents plays that build toward a crisis and then stops. Audience members are then asked to intervene by literally stepping onto the stage to replace a character that they identify with and to improvise by role-playing a solution that will resolve the crisis in the play (Boal 1985). This method of working was about empowering the community to act and be involved in resolving the issues of dysfunction presented in performance (Hazou 2021).

In December, Puppet Antigone (Hazou and Gordon 2017) was co-directed by Rand Hazou and Derek Gordon and staged with a small cast of prison actors at Auckland Prison. The production enlisted Bunraku-style puppets and syncretic approaches in the staging that allowed the cast to reinscribe the Greek text with certain cultural readings to situate the play within a Māori world. By enlisting syncretic approaches in the staging, the production allowed the cast to reinscribe the text with cultural readings and a subaltern politics that might be understood by the cast and resonate with the wider prison community (Hazou 2020).

Most recently, Ngā Pātū Kōrero: Walls That Talk (Hazou 2019) was staged by incarcerated men at Unit 8 Te Piriti in Auckland Prison. The production was devised from verbatim responses to interviews conducted with members of the Unit. The verbatim responses and focus on spoken word were counterposed in production with the use of masks to enhance the physical skills and expressiveness of the performers under the guidance of mask practitioner Pedro Ilgenfritz. The final production was directed by Rand Hazou and presented to an audience of prison staff, incarcerated members of the prison community, and invited guests (Hazou et al. 2021).

4.3. Creative Endeavours and Interrogating Structural Oppression

In his early description of Prison Theatre, James Thompson argued for the need to put those people most affected by the criminal justice system at the centre of the work, and critiqued programmes that only provide a space for personal reflection arguing instead for work that can ‘turn an individual from introspection to exploration of the world outside’ (Thompson 1998a, p. 20). This aligns with the appeal made by Theatre in Prison practitioner Paul Heritage who argued for the potential of theatre to ‘begin a process that invokes the transformative powers of theatre in ways that concentrate not on the individual criminal but potentially on the society in which we all play a part...’ (Heritage 1998, p. 40). Recent scholarship exploring the benefits of theatre and creativity to incarcerated communities circumvents considerations of ‘use’ and the ‘aesthetics of redemption’ to highlight instead the importance of art as a ‘fundamental human right and a potent form of resistance’ (Woodland and Hazou 2021, p. 387). These understandings underscored the design and delivery of the Performing Liberation project which was informed by the idea that those most affected by incarceration should be placed at the centre of creative endeavours. We also focused on creative endeavours as a means to interrogate the broader structural issues contributing to carcerality. In this paper, our aim is to interrogate these structural issues as they intersect with creative endeavours by focusing on the notion of liberation as a way of unshackling the body, mind, and spirit.

5. Description of Key Moments in the Workshop

In this section, rather than provide a detailed account of all the exercises and facilitation of the creative workshops, we focus instead on describing two key moments that seemed to inform the creative responses of the participants. Our approach to facilitating the workshops was guided by an acknowledgement of Māori protocols which ‘privileges Māori knowledge and ways of being’ (Smith 2008, p. 120). As detailed below, the workshops were informed by a pōwhiri, or a traditional cultural welcoming ceremony performed by the Māori prisoners for the visiting artists from the US. The provision of this ritual welcome set the affective and intellectual register for the workshops which the facilitators responded to in genuine, emotive, and meaningful ways.

The pōwhiri is a unique customary welcome practised by Māori, which shares some similarities with other Indigenous welcome protocols such as the Australian Aboriginal ‘welcome to country’. The etymology of the word pōwhiri are the two words pō or ‘unknown’ and whiri or ‘plaiting’. A pōwhiri, therefore, is about the weaving of unknowns (Rameka et al. 2021, p. 5). The purpose of a pōwhiri is to provide a process of engagement between two parties and involves one group welcoming another into their place of belonging. The ritual is composed of a series of specific sequences of enacted events. Typically, a pōwhiri would be performed on a marae or the courtyard of a Māori meeting house, but the location and the sequence involved can often be adapted to suit the requirements of the situation. For the pōwhiri at Auckland Prison, the guests were welcomed into the space with a karanga (a ritual chant of welcome) performed by a transgender prisoner who held knowledge of language and tikanga (cultural protocols). According to McCallum, the karanga is a call that ‘reaches not only the physical ears of those who stand waiting, but also the ancestors who have passed to the spirit world’ (McCallum 2011, p. 95). Following the call and a whaikōrero (formal speech) by the hosts, the visitors and the prison participants sat facing each other for the duration of the ceremony, which involved further speeches and songs before the ritual concluded in a hongi, or the pressing of noses together signifying the sharing of breath. This entire ceremony is considered tapu (sacred) as the guests and hosts engage on both a physical and spiritual level. According to McCallum, for participants of the pōwhiri, ‘there is an efficacious shift in their state of being, which is emotional, ontological and psychological’ (McCallum 2011, p. 93). The final aspect of the ritual involves sharing of refreshments usually in the form of a biscuit and a cup of tea.

After the welcome and the sharing of some refreshments, Dowling led the first workshop which involved a physical warmup and some introductory movement work. Following this, Daniels started by sharing some of his personal story as a formerly incarcerated Black man. He explained that his ancestors were taken to the US as slaves and that he found through a DNA test that he was 74% Nigerian. He explained to the participants that he was interested in visiting his ancestral African homeland and reconnecting with his ancestral customs and culture.

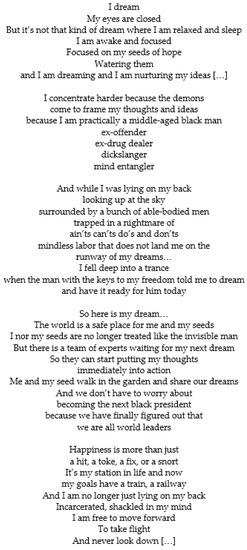

Following his personal introduction, Daniels asked the participants to get into a circle and shared his experiences as an actor in the production Man.Alive (Dowling et al. 2009). After more than ten years of incarceration, Daniels was invited to participate in a theatre production co-directed by Amie Dowling, Paul S. Flores, and Natalie Greene, and first staged at the Studio Theater of the University of San Francisco (Daniels 2021b). The play featured the stories and experiences of incarceration and involved highly choreographed sequences of repetitive actions that represented the regimented routines of prison. Daniels explained that the original production opened with his reciting of a poem he wrote that references the famous speech by Rev. Dr Martin Luther King and expresses hope and a vision for a new reality for people impacted by White supremacy, slavery, and incarceration (See Figure 1 Dream by Reggie Daniels).

Figure 1.

An abridged version of the poem ‘Dream’ by Reggie Daniels, originally published in Brigham and Conner (2018).

During the workshop at Auckland prison, and with the participants still arranged in a large circle, Daniels asked the attendees to chant ‘dream, dream, dream’ over and over as he shared his poem. As the group slowly began to chant, Daniels began reciting his poem. The chanting would occasionally subside throughout the recitation as Daniel’s delivery grew in tempo and volume, only to be taken up again in those brief moments of pause between the stanzas.

The recitation of the poem with the chanting was a palpably emotional and important moment that seemed to create a sense of unity in the workshop attendees. Daniels was moved to tears. The participants were also visibly affected, some holding back tears. It was a profound moment that was further confirmed by the sincere thanks expressed by the participants to Daniels for sharing his words.

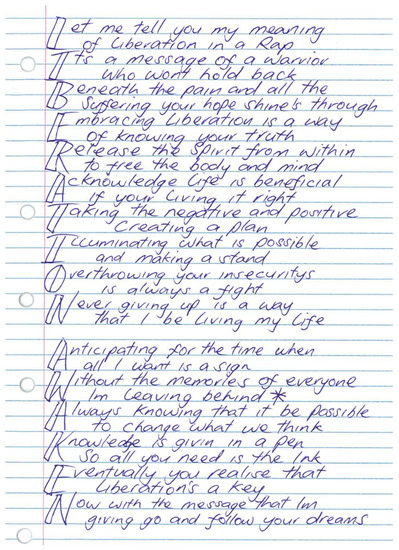

Following the recital, the participants were given the list of questions on liberation provided by Banks. These questions were printed on paper, handed out to the participants, and read out loud by Hazou. In response to the sharing of his personal story and the recitation of his poem, the participants appeared to have been galvanised and inspired to respond to these questions of liberation. The next day, participants shared what they had created. All the participants had been inspired to stay up late the night before to write stories, draw, and compose poems and songs. One of the participants shared his response which he composed as a rap (See Figure 2).

Figure 2.

A song written by one of the workshop participants at Auckland Prison responding to the questions about liberation provided by an incarcerated individual at San Quentin.

6. Analysis: Liberation and Creative Expression

This article explores our recollections of key moments in the workshop, the pōwhiri, the recitation, and chanting that we have documented above, in an attempt to explain the efficacy of the workshops in helping to activate the creativity of the prisoners. In this section, we attempt to make sense of these moments and to explore their significance as acts of liberation. We explore this creative stimulation in relation to the notion of liberation, as a useful concept to interrogate various forms of oppression, and as a practice that is concerned with unshackling the body, mind, and spirit.

In Prison Theatre and the Global Crisis of Incarceration (2020), Ashley Lucas argues that while theatre in prison might lift performers and audiences momentarily out of the prison setting and offer a different and shared experience, this does not free people from incarceration. Lucas argues that theatre in prison “can promote free thinking and empathy, but it is not, in fact, liberation” (Lucas 2020, p. 39). While we agree that the material conditions of carcerality are oppressive and require persistent efforts in order to challenge and transform them, we nevertheless take issue with this position as it defines liberation solely in terms of social mobility and uncritically associates being outside prison with freedom. Being free from prison does not necessarily mean freedom from exposure to ongoing surveillance, confinement, and control by the carceral system. We suggest that a more critical engagement with the theory and practice of liberation is required which deepens an understanding of the affordances of creative engagements for incarcerated communities. Moreover, our own conception of liberation is informed by the seemingly contradictory realisation that some might experience more emotional and spiritual freedom inside prison than on the outside. This is confirmed by co-author Daniels who spent more than ten years incarcerated. The prison regime can be a place in which incarcerated individuals can forge strong familial ties and find a sense of connection that they did not have on the outside. For Daniels, liberation is connected to an appreciation for humanity, love, and spirit, that can free us from thoughts that bind us. This can result in an emotional vulnerability that one might not experience in the world beyond the prison fence. Daniels explains that he sometimes yearned for the feeling of connection with his brothers on the inside—an understanding and brotherhood that he could not find on the outside.

We understand liberation as a useful tool to critique various forms of oppression and exclusion. As an aim of social justice and as articulated in various civil rights movements, social liberation is connected to the process of striving to achieve equal status and rights. At an individual level, liberation can also articulate the notion of personal freedom of expression, thought, or behaviour. In writing this article, we articulate liberation as a process of casting off the shackles of the mind, body, and spirit. In this way, liberation can be expressed in multiple ways and can be physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual.

6.1. Unshackling the Body

In the context of a prison where technologies of surveillance and control are mobilised to produce ‘obedient’ bodies, the pōwhiri and the creative workshops offered opportunities for the participants to transcend these restrictions and free up the body temporarily. Moreover, incarceration lives in the body in the sense that the institutional power of the prison works to habituate bodily behaviours and expressions. Elsewhere, research has documented how physical performance can facilitate a sense of “re-embodiment” for the men who were living within a system and space that routinely polices bodies (Hazou et al. 2021). The pōwhiri, the short movement exercises that followed, and the chanting and recitation, helped to create a space for participants to unshackle the body in the sense of temporarily transcending rigid and habituated physical behaviours and movements that are imposed within carceral spaces.

The pōwhiri or welcoming ceremony set the physical, affective, and intellectual registers for the creative workshops. In particular, the use of the hongi in which guests and hosts press noses together symbolising the ‘sharing of breath’, provided opportunities to break from the physical and relational distance that is often constituted by and enforced within prison settings. Reflecting on the impact of the pōwhiri and the sharing of breath, Daniels explained later: ‘It brought tears from my eyes. The hongi—the pressing of the noses and the sharing of breath. This was powerful because in the US prison system we are prohibited from touching’ (Daniels 2021a). At San Quintin, for example, it is not just touching that is prohibited, but any perceived transgression of interpersonal boundaries. The California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation policy prohibits ‘undue familiarity’. As Hatton explains, within American correctional institutions the incarcerated are warned against over-familiarity, correctional officers are cautioned to avoid it, and outside volunteers and contractors are advised not to inadvertently commit it. For Hatton, as a concept, overfamiliarity and its prohibition are ‘at the centre of the dehumanising culture of incarceration’ (Hatton 2021, p. 519). The pōwhiri at Auckland prison helped to set up a different kind of engagement between participants in the workshops which emphasised relationality and physical propinquity that also helped to challenge some of the dehumanising restrictions that carcerality often places on the body that can result in the loss of individuality and physical agency.

6.2. Unshackling the Mind

When prompted to explain why he began his workshop with a very personal and emotional sharing of his story, Daniels cited the emotional impact of the pōwhiri and explained:

I shared my former experiences with crime and my cycles of addiction. I shared how I was seen as the black sheep by my family. I wanted to make them know that I understood what it was like to be written off. I wanted to share so that we could be on an equal footing. People inside are often expected to bare their souls in front of observers. I was leading by example in terms of demonstrating vulnerability.(Daniels 2021a)

Daniels insists that his approach was to ensure that the participants did not feel judged for their mistakes and defined solely in terms of their criminality. This reductive and deficit approach underpins the corrections system, and Daniels wanted to ensure that the participants would be seen as whole human beings at least for the duration of the workshops. For us, this approach is informed by an understanding that oppression has done its darkest work when it has become internalised. In attempting to facilitate creativity in carceral spaces, the work of liberatory practice is to resist the internalisation of oppression created and reinforced by the carceral system which so often dehumanises the people that it confines.

Internalised oppression works when the dominant discourse becomes powerful to the extent that people internalise negative ideas about their group (Aguilar 2014, p. 14). Griffin defined internalised oppression as a phenomenon that involves a subordinate group adopting a dominant group’s ideology resulting in the “acceptance that their subordinate status is deserved, natural and inevitable” (Griffin 1997, p. 76). The focus for liberation should not only involve resisting mass incarceration and finding alternatives to punitive approaches to crime but also involve resisting the internalisation of carcerality and the normalisation of these processes. Reflecting on the impact of the recitation and the chanting, Daniels explained:

The chanting became a ritual evocation of hope. It humanised the space and gave participants an opportunity to show up in an authentic way and not have to be restricted by their crimes or the mistakes of their past. But that they could show up as human beings and be real and recognised without judgement.(Daniels 2021a)

While we acknowledge that the material reality of confinement and incarceration are important, far more important to tackle are the consequences of incarceration that lead, not only to the dehumanisation of incarcerated individuals but also to the internalisation of this carceral logic.

The recitation of the ‘Dream’ poem was a repudiation of the internalisation of carcerality and self-doubt. The first part of the poem features a man lying on his back who is surrounded by able-bodied men and is trapped in self-defeatist internal logic. The second half of the poem presents the narrator no longer lying on his back but instead giving himself permission to dream without excuses. In other words, the mental cycle of self-defeat is broken thereby providing hope for the poet and the audience to move freely towards liberation. These sentiments seem to be echoed in the song written by one of the workshop participants at Auckland Prison, who seems to explain liberation as “a message of a warrior who won’t hold back” For this poet, liberation is acknowledging the hope beneath the pain and the suffering, and “embracing liberation is a way of knowing your truth” (Figure 2). Both poems express sentiments about the unshackling of the mind which involves recognition and empowerment in which self-doubt is no longer the dominant or controlling voice. Daniels suggests that artistic engagement and expression within carceral settings is a productive way to challenge the self-doubt and the internalisation of carcerality produced by prisons. The prison works to impress on you the idea that you deserve to be punished and that you don’t deserve to be among society and that you have no real value. For Daniels, “artistic engagement can say that there is a part of us that is creative that always has value, even if we are incarcerated, even if we have made mistakes. Mental freedom here is about creative self” (Daniels 2021a).

6.3. Unshackling the Spirit

One of the ways to understand the impact of Daniels’ poem and the communal chanting is through bell hooks’ notion of love as a spiritual practice and as an act of liberation. For hooks, ‘the moment we choose to love we begin to move toward freedom, to act in ways that liberate ourselves and others’ (Hooks 1994, p. 298). hooks begins her chapter ‘Love as the Practice of Freedom’ by pointing to a problem arising from our ‘blind spots’ when we confront oppression and domination. hooks observes that many of us are ultimately motivated by ‘self-interest’ when fighting domination. Rather than being motivated by a desire to end politics of domination or collective transformation, often our confrontations of oppression express a desire ‘simply for an end to what we feel is hurting us’ (Hooks 1994, p. 290). As Monahan explains in his insightful reading of hooks, we tend to focus on one aspect of domination, the one that most directly impacts us, and either ‘ignore altogether, or offer only lip-service to the ways in which different kinds of domination are linked systematically to each other’ (emphasis in original, Monahan 2011, p. 104). For hooks, the ability to acknowledge blind spots can emerge only if we alter our motivation away from the alleviation of our own suffering and instead expand our capacity to care about the oppression and exploitation of others. For hooks a ‘love ethic makes this expansion possible’ (1994, p. 290). hooks cites M. Scott Peck’s working definition for love as ‘the will to extend one’s self for the purpose of nurturing one’s own or another’s spiritual growth’ (cited in Hooks 1994, p. 293).

Hooks’ conception of love is as a practice, a dynamic process, and not a static state of being. It is a spiritual practice that one manifests and must be nurtured for it to thrive and grow. In his explication of hook’s love ethic as a practice, Monahan explains that we must take up the challenge of coming to know those we love ‘both as they are now, and as they have it in them to become’ (Monahan 2011, p. 107). For Monahan, this involves an affirmation of nurturing and the facilitation of growth toward the possibility of a future flourishing.

Reflecting back on the workshops, we suggest that the cultural opening of the pōwhiri provided a space of nurturing and becoming which was further enhanced by the sharing of Daniel’s personal story, the recitation of the poem, and the communal chanting. We suggest that one way we might understand the workshops at Auckland prison is through hooks’ conceptions of love as a spiritual practice and as an act of liberation. The workshops utilised the affordances of creative expression within carceral spaces to shift the attention of the participants, from a narrow focus on their own interests and the alleviation of their own suffering to a concern for the care of others. This was a central inspiration informing the Performing Liberation project which sought to provide opportunities for two communities to engage in creative dialogues together as a means to acknowledge and potentially address the systemic issues of oppression that underscore global mass incarceration that disproportionality impacts Indigenous peoples and communities of colour. It was through artistic engagement and dialogue with each other that the project sought to facilitate an awareness of the systemic issues of oppression that these disparate communities faced.

7. Conclusions

A central provocation for the Performing Liberation project was the question, ‘What does Liberation Feel like?’ The workshops at Auckland Prison provided opportunities for the participants to share creative work that engaged with concepts of oppression, liberation and love in ways that are not necessarily grasped intellectually through words, but rather explored experientially through poetry, dance, ritual, and song. By utilising creative expression, the workshops highlighted the experiential and affective dimensions of liberation, as a practice that nurtures the intellect, heart, and spirit. In reflecting on the workshops, we have attempted in this article to analyse the creative workshops through hook’s notion of an ethic of love as an act of liberation. However, central to hook’s conception of love as a practice of freedom is self-awareness and the importance of acknowledging our blind spots. Thus, as we reflect on the workshops and their impact, we also take this opportunity of hindsight to reflect on our own blind spots entering into this project and the creative process.

For Hazou, the workshops were part of a larger project and an attempt to create agency and empowerment for two communities directly impacted by incarceration by facilitating sustained creative dialogue. Unfortunately, despite the initial creative responses from the workshop participants at Auckland prison, the ongoing dialogue did not eventuate. While the questions on liberation and Daniel’s workshop produced some very compelling responses from the participants at Auckland prison, unfortunately when these were shared through networks back to the incarcerated community at San Quentin, they did not provoke a follow-up response. The creative engagement did not result in the sustained and ongoing creative dialogue between these two incarcerated communities that was envisioned at the start of the project. In reflecting on why this engagement did not continue; we have to acknowledge that Banks got released from San Quentin and as such had more pressing and immediate concerns of life beyond incarceration such as the need to care for his family and secure employment. In hindsight, one blind spot that we have become aware of is that while artists or facilitators on the outside might have time and financial security to set up connections or opportunities for incarcerated communities to engage in arts practice and collaboration, it is difficult to expect someone who is incarcerated or who has just been released from prison to lead these initiatives. The practicalities involved in things like sending and following up on emails, or even getting permissions to visit prison, might be too challenging for incarcerated or previously incarcerated individuals to contend with. While connection is one of the main tools that we can use to break through the confinement and isolation imposed by carcereality, when we as outside artists create these opportunities, we need to be aware that those impacted most directly by incarceration might not have the will or the way to connect.

For Daniels, the workshops were an opportunity to explore a blind spot in relation to the cultural specificities of engaging with Māori culture. Daniel’s invitation to deliver the workshops at Auckland prison acknowledged his expertise as an educator and cultural facilitator which was informed by his experience as a previously incarcerated black man. Yet while this acknowledgement recognised certain commonalities among various marginalised communities impacted by global incarceration, Daniels also had to contend with the specificity of the Māori cultural context at Auckland prison. Previously Daniels had encountered and befriended a Māori prisoner during his time in jail in the US and had become aware of his own judgements regarding the practice of tribal facial tattoos or tā moko (See Nikora et al. 2007). In the US context, tattoos on the face are often regarded as part of anti-social behaviour. In approaching the workshops at Auckland prison, Daniels was aware of his own previous judgements when encountering aspects of Māori culture and had to approach his interactions with the participants with humility. In hindsight, this blind spot was about the need to register and acknowledge the specificity of cultural engagement within the assumed ‘universal’ experience of carcerality.

According to hooks, awareness is central to the process of love as the practice of freedom. According to hooks, “whenever those of us who are members of exploited and oppressed groups dare to critically interrogate our locations, the identities and allegiances that inform how we live our lives, we begin the process of decolonization” (Hooks 1994, p. 295). The workshops at Auckland Prison succeeded in providing a platform of creative engagement to allow an ethic of love to emerge that facilitated experiential engagements with notions of liberation. What might be required further are opportunities for additional self-awareness so that communities impacted by mass incarceration can interrogate further the locations, identities, and allegiances that inform the ongoing struggles against oppression and mass incarceration.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft, R.H. and R.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research and the creative workshops were funded by Auckland Prison, the Massey University Distinguished Visitors Fund (2019), and the Massey University Strategic Research Excellence Fund (SREF) under Project Title ‘Theatre, Creative Arts, and Justice’ [Project Code: 1000021569].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Research for this paper was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. The creative workshops developed out of the ‘Prison Voices’ project involving ongoing creative engagements and outputs at Auckland Prison was approved by the Massey University Human Research Ethics Committee (NOR 18/63, 17 April 2019).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the creative workshops.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank our colleges Krushil Watene (Ngāti Manu, Ngāti Whātua) and Sarah Woodland for reading and commenting on earlier drafts of this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Aguilar, Danielle Nicole. 2014. Oppression, Domination, Prison: The mass incarceration of Latino and African American men. The Vermont Connection 35: 13–20. Available online: https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/tvc/vol35/iss1/2 (accessed on 17 September 2021).

- Alexander, Michelle. 2010. The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness. New York: The New Press. [Google Scholar]

- Artistic Ensemble. 2014. Waterline. San Quentin: San Quentin Prison, November 5. [Google Scholar]

- Artistic Ensemble. 2015. Faultline. San Quentin: San Quentin Prison, November 20. [Google Scholar]

- Artistic Ensemble. 2016. Ways to Disappear. San Quentin: San Quentin Prison, November 18. [Google Scholar]

- Artistic Ensemble. 2018. Site Unseen. San Quentin: San Quentin Prison, January 24. [Google Scholar]

- The Artistic Ensemble. n.d. Ways to Disappear. Available online: http://www.aesq.info/performances/ways-to-disappear/ (accessed on 17 September 2021).

- Balfour, Michael, Brydie-Leigh Bartleet, Linda Davey, John Rynne, and Huib Schippers. 2019. Performing Arts in Prisons: Captive Audiences. Bristol: Intellect Books. [Google Scholar]

- Boal, Augusto. 1985. Theatre of the Oppressed. Translated by Charles McBride, and Maria-Odilia McBride. New York: Theatre Communications Group. [Google Scholar]

- Brigham, Erin, and Kimberly Rae Conner. 2018. Today I Gave Myself Permission to Dream: Race and Incarceration in America. San Francisco: University of San Francisco Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cash, Johnny. 1969. At San Quentin, Bob Johnston. Columbia. CS 9827. Vinyl.

- Cecil, Dawn K. 2020. Ear Hustling: Lessons from a Prison Podcast. In The Palgrave Handbook of Incarceration in Popular Culture. Edited by Marcus Harmes, Meredith Harmes and Barbara Harmes. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 51–65. [Google Scholar]

- Coffey, Amanda. 1999. The Ethnographic Self: Fieldwork and the Representation of Identity. London: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Cunneen, Chris, and Juan Tauri. 2016. Indigenous Criminology. Bristol: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Daniels, Reginold. 2021a. University of San Francisco, San Francisco, CA, USA. Personal communication, August 8.

- Daniels, Reginold. 2021b. Still alive: Reflections on carcerality, arts and culturally responsive teaching. Research in Drama Education: The Journal of Applied Theatre and Performance 26: 406–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dembin, Russell. 2019. Nothing But Time: When ‘Godot’ Came to San Quentin. Available online: https://www.americantheatre.org/2019/01/22/nothing-but-time-when-godot-came-to-san-quentin/ (accessed on 17 September 2021).

- Department of Corrections NZ. 2020. Prison Facts and Statistics—March 2020. Available online: https://www.corrections.govt.nz/resources/research_and_statistics/quarterly_prison_statistics/prison_stats_march_2020 (accessed on 10 August 2021).

- Dowling, Amie, Paul S. Flores, and Natalie Greene. 2009. Man.Alive. Stories from the Edge of Incarceration to the Flight of Imagination. San Francisco: Theatre Production. The University of San Francisco Studio. [Google Scholar]

- Dowling, Amie. n.d. Amie Dowling Website. Available online: http://www.amiedowling.com/a51naefsqds2js3ag8ruou30j2kqsh (accessed on 17 September 2021).

- Freeman, John. 2015. Remaking Memory: Autoethnography, Memoir and the Ethics of Self. Oxfordshire: Libri Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Geary, Daniel. 2013. The Way I Would Feel About San Quentin: Johnny Cash & the Politics of Country Music. Daedalus 142: 64–72. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin, Pat. 1997. Introductory module for the single issue courses. In Teaching for Diversity and Social Justice: A Sourcebook. Edited by Maurine Adams, Lee Anne Bell and Pat Griffin. New York: Routledge, pp. 61–81. [Google Scholar]

- Haines, Juan. 2018. Artistic Ensemble Showcases Its Talents. San Quentin News. March 19. Available online: https://sanquentinnews.com/artistic-ensemble-showcases-talents/ (accessed on 17 September 2021).

- Hatton, Oona. 2021. ‘If you are going to treat someone like a human’: White supremacy and performance programmes in Northern California’s correctional facilities. Research in Drama Education: The Journal of Applied Theatre and Performance 26: 511–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazou, Rand, and Derek Gordon. 2017. Puppet Antigone. Paremoremo: Theatre Production. Unit 9, Auckland Prison, December 8. [Google Scholar]

- Hazou, Rand, Sarah Woodland, and Pedro Ilgenfritz. 2021. Performing Te Whare Tapa Whā: Building on cultural rights to decolonise prison theatre practice. Research in Drama Education: The Journal of Applied Theatre and Performance 26: 494–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazou, Rand. 2019. Ngā Pātū Kōrero: Walls that Talk. Paremoremo: Unit 9, Auckland Prison, June 14. [Google Scholar]

- Hazou, Rand. 2020. Repairing the Evil: Staging Puppet Antigone (2017) at Auckland Prison. In The Routledge Companion to Applied Performance: Volume One–Mainland Europe, North and Latin America, Southern Africa, and Australia and New Zealand. Edited by Tim Prentiki and Ananda Breed. New York: Routledge, pp. 32–42. [Google Scholar]

- Hazou, Rand. 2021. Theatre, Incarceration and Citizenship. In Tūtira Mai: Making Change in Aotearoa New Zealand. Edited by David Belgrave and Giles Dodson. Auckland: Massey University Press, pp. 137–51. [Google Scholar]

- Heritage, Paul. 1998. Theatre, prisons and citizenship: A South American way. In Prison Theatre: Perspectives and Practices. Edited by James Thompson. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers, pp. 31–41. [Google Scholar]

- Hooks, Bell. 1994. Love as the practice of freedom. In Outlaw Culture: Resisting Representations. New York: Routledge, pp. 289–298. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, Jenny. 2005. Doing the Arts Justice: A review of Research Literature, Practice and Theory. Edited by Andrew McLewin and Angus Miles. London: The Unit for the Arts and Offenders. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, Moana. 2017. Prison should never be the only answer. E-Tangata. Available online: https://e-tangata.co.nz/comment-and-analysis/moana-jackson-prison-should-never-be-the-only-answer/ (accessed on 17 September 2021).

- Lucas, Ashley E. 2020. Prison Theatre and the Global Crisis of Incarceration. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- McAvinchey, Caoimhe. 2011. Theatre & Prison. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- McCallum, Rua. 2011. Maori performance: Marae Liminal space and transformation. Australasian Drama Studies 59: 88–103. [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh, Tracey, and Kim Workman. 2017. Māori and Prison. In Australian and New Zealand Handbook of Criminology, Crime and Justice. Edited by Antje Deckert and Rick Sarre. Melbourne: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 725–35. [Google Scholar]

- Mita, Merata, and Martyn Sanderson. 1980. Keskidee Aroha. Auckland: Scratch Pictures. [Google Scholar]

- Monahan, Michael J. 2011. Emancipatory Affect: Bell hooks on Love and Liberation. The CLR James Journal 17: 102–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikora, Linda Waimarie, Mohi Rua, and Ngahuia Te Awekotuku. 2007. Renewal and resistance: Moko in contemporary New Zealand. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology 17: 477–89. [Google Scholar]

- Rameka, Lesley, Ruth Ham, and Linda Mitchell. 2021. Pōwhiri: The ritual of encounter. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawyer, Wendy, and Peter Wagner. 2020. Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie 2020. Prison Policy Initiative. Available online: https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2020.html (accessed on 31 December 2021).

- Shilliam, Robbie. 2011. Keskidee Aroha: Translation on the colonial stage. Journal of Historical Sociology 24: 80–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shilliam, Robbie. 2015. The Black Pacific: Anti-Colonial Struggles and Oceanic Connections. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Linda Tuhiwai. 2008. On Tricky Ground: Researching the Native in the Age of Uncertainty. In The landscape of Qualitative Research. Edited by Norman K. Denzin and Yvonna S. Lincoln. Los Angeles and London: Sage, pp. 133–43. [Google Scholar]

- Stats NZ. 2015. How Is Our Māori Population Changing? 2017. Available online: http://www.stats.govt.nz/browse_for_stats/people_and_communities/maori/maori-population-article-2015.aspx (accessed on 27 June 2021).

- Tapia, Ruby. 2018. What Is the Carceral State? The Carceral State Project’s Symposium 2018–2019. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan, October 3. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, James, ed. 1998b. Prison Theatre: Perspectives and Practices. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, James. 1998a. Introduction. In Prison Theatre: Perspectives and Practices. Edited by James Thompson. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers, pp. 9–23. [Google Scholar]

- Winfrey, Tommy. 2014. Original Production of Waterline Calls Forth a Standing Ovation. San Quentin News. December 31. Available online: https://sanquentinnews.com/original-production-of-waterline-calls-forth-a-standing-ovation/ (accessed on 18 September 2021).

- Woodland, Sarah, and Rand Hazou. 2021. Carcerality, theatre, rights. Research in Drama Education: The Journal of Applied Theatre and Performance 26: 385–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Population Review. 2021. Incarceration Rates by Country 2021. Available online: https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/incarceration-rates-by-country (accessed on 17 September 2021).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).