1. Tensions Leading to Concerns

The issues of refugees and representation have preoccupied me for decades, especially in view of the difficulty of combining them: the problem of the conjunction “and”. This difficulty rests on other tough combinations and tensions, the primary one of which is time: the time of publishing. Ever since the social reality made it impossible to distinguish my academic work, which frequently focuses on historical texts and “old master” art, from the contemporary world, I began to bring the latter explicitly in contact with the former. Even though the social consequences of the artistic and formal aspects of artefacts have always been part of what I was examining, the temporality of historicity was more or less a background. However, when I selected more recent, even contemporary, topics, I became aware of the consequences of the durational process of publishing. Both books and journal articles take years to appear. When this finally happens, they are already “historical”, addressing situations that most likely have changed drastically since the time of writing. This makes research on the contemporary impossible or at least very challenging, even if some particular issues remain urgent and actual. The long and the short durations are always in tension. Yet, historical artefacts, now often termed objects of “cultural heritage”, continue to matter, for they remain with us and keep talking to us. Therefore, a drastic gearshift in relation to time does not seem a solution.

1And then there remains the tension between academic and non-academic concerns. This is not a problem for me, but for the reception of my work, it sometimes is. Then came the invitation to contribute to this Special Issue of Humanities. This is a journal title that foregrounds both aspects of that tension: the scholarly interest in cultural artefacts; in their social–historical framing, which it is the mission of “the humanities” in the academy to study; and the social need to involve myself in the contemporary, which requires an engagement with the “humanity” of other human beings. These two meanings of the title trigger my wish to integrate, in this case, the two terms of the title of the Special Issue, one social, one analytical. How can refugees and representation be brought together in reflection and analysis that will not betray one side of this duality in the journal’s title? Asking this question already assumes tension, which, indeed, I feel is an important aspect of the combination. In other words, representation is a problem when it comes to the disempowered people who have had to leave their homes in order to survive, without having a clear and welcoming place to go. At the same time, “representation” is an ambiguous word. It means not only speaking about but also speaking for, as in political situations. This form of representation remains acutely necessary. This tension underlies my reflections in this text. This is a problem that we cannot wish away. Representing—in artwork, documentation and literature—people and their situations imports both the lack of modesty and the distortions caused by the inevitable fictionality that is involved, for the makers of artwork and also of academic studies are bound to appeal to the imagination alongside the account of the social reality they seek to make visible for others. This produces tension as well as a fruitful domain of communication.

Five thoughts, or standpoints, opinions or convictions, summed up as

concerns, all quite simple and even banal, which I have had on my mind for a long time, will guide my reflections in this essay in which these tensions are pervasively present; not as sections but as red threads that meander through it. Moreover, when I say “essay”, I mean this quite literally. This is not a simple, traditional scholarly article, developing research and drawing conclusions

about something, which, in addition to the tensions sketched above, I cannot write because I do not know enough and have no experience of life as a refugee, but it is an essay in the literal sense of an

attempt: a noun, attempt, and a verb, attempting, which will recur frequently in this text, as its key. With a growing awareness of the tension between publication pace and the contemporary, I spent much time during the past two decades

attempting, indeed, to better understand in the moment, in the

now, the contemporary culture in which I live in several ways that challenged me to divert from, or expand, the classical academic discipline. This is difficult; in addition to the fact already mentioned that scholarly publications are always-already belated in relation to the people and events about whom and which they are written, it also produces tension between the single voice of the scholar undertaking the research and the plurality of the interlocutors—whom I decline to call “subjects” in the traditional, subordinating sense common in ethnography and sociology. This is why the essay, with its ongoing

attempting, seems a more appropriate genre than the monologic polished scholarly analysis or overview. Therefore, to borrow and inflect Donna Haraway’s title

Staying with the Trouble (

Haraway 2016), instead of overcoming or surpassing it to end with firm conclusions, I want to

stay with the attempt. The essay as form, as Adorno famously phrased it (

Adorno [1954–1958] 1991), precludes propositional conclusions, and so does the discrepancy between what I know and what other people experience. The essay, taken at its word, is therefore the only possible genre of writing that has the slimmest chance to at least soften the opposition between the impossibility and the necessity to write about—inevitably representing—refugees.

2I have tried other means as well. In addition to broadcast conversations and journalistic articles, the most different and difficult for an inveterate academic, one of these attempts I tried was video making—without formal training as a filmmaker. This just happened when, in my social environment, I witnessed an injustice against someone that I felt compelled to address, analyse and make known (

Bal 2022, chp. 3). Since this was accomplished in the name of European law, I could not disentangle myself from what happened to my neighbour, an immigrant from an Arabic country who was trying to evade poverty and the lack of education that comes with it. This became the first of a series of documentaries and installations on issues of migration, identity and the need to escape. In what follows, I will briefly invoke some of the resulting films. I chose this genre, or medium, mainly because the feature of video- and filmmaking, which is the collectivity-, interactivity- and contact-based mode, is what has glued me to that ongoing attempt. In this respect, it is opposed to the monologic tendency in academic writing. This has brought me not only a precious new experience but, most importantly, into close contact, friendships and contemporaneity with people I would probably never have met otherwise and to whom the events presented in the films were happening then-and-there.

As always when I try something new, there is an issue of terminology here, and terminology matters. To use a generalizing term, I have called the people I met migrants. This seemed the more generalizable term for people who escaped a situation that did not let them develop, flourish, even survive. In common parlance, people tend to distinguish refugees, who are running for their lives, from economic migrants, who “simply” want to improve their economic situation. I find that distinction reasonable, yet somewhat problematic, not to diminish the horror and fear of refugees but to acknowledge that no one would leave behind all that constitutes their life without having a good, life-saving reason to do so. In addition, such terms indicate others, leaving “us” out of sight. In my view, a better way to speak “about” as well as “with” the people I had the profound pleasure to get to know is the concept I have developed elsewhere of “migratory culture”. That term avoids the “us”/“them” divide that so perniciously rules the world. Instead, “migratory culture” is the culture in which migration is a normal situation, in which everybody lives and participates and which is of all times (

Bal 2015). Refugees are as much part of that culture as anyone else—that culture we all share. The primary starting point of these reflections is the simple but crucially important insight that the people we call “immigrants” or “newcomers” cannot but have serious reasons to uproot their lives, reasons that are much more profound and serious than the reasons inhabitants of the so-called “host countries” (think they) have to resist their arrival.

The concerns I cannot shed are all anchored in tensions. First, the news on television works against any (audio-visual) engagement with the fate and plight of people in hard times, such as refugees. It is too repetitive and each item is too short. Second, refugees live in long duration, without having the perspective of an end in sight. This enduringness, as well as for having to leave behind their entire lives and relations because where they are they are no longer safe, must be a traumatic experience. However, third, trauma cannot, indeed, must not, be represented. It cannot for reasons of psychic foreclosure, which is the defining aspect of trauma; it must not because trying to do so would entail being trapped in voyeurism, the lack of modesty, but neither can it be ignored. My political view is obvious: refugees have the same “human rights” as everyone on the planet has or ought to have. This all converges in the impossibility of what is necessary, and that is my fifth concern, a fundamental contradiction. The life and experiences of refugees must, even if they cannot, become known to us, if we are to be of any help whatsoever to our fellow humans. The conjunction “and” in the theme of this Special Issue, “Refugees and Representation”, confronts us as (essay) writers with the contradictory task of doing the necessary-impossible.

2. Trying, Failing and Thinking

I am beginning this writing during the Taliban take-over of Afghanistan; the attack on the airport of Kabul where people fearing for their lives, trying to become legitimate as refugees, were killed; the US revenge attacks; and images of desperate, anxious and deprived people in low-resolution, badly iPhone-filmed takes, repeated as soon as I open my television—and all this on an everyday basis, in the present. Just barely exiting the COVID-19 lockdown and knowing it will return, I keep having these five concerns whirling through my head. To sum these up succinctly, they are: the combinations and the resulting tensions the conjunction “and” entails. This includes the time of publishing and of history—that of refugee experience as well as that of cultural artifacts from the historical past; the academic reflection and the socio-political context; the question the journal’s title, Humanities, raises; and the lack of modesty paired with the distortions that fiction creates. In all this the now of writing participates. Instead of shedding them and escaping into the rationality that supposedly guides intellectual work, I will be trying (essaying) to do something that I know can only fail: making two artworks speak with each other in connection to the five concerns mentioned, even though they could not be more different.

In spite of their stark differences, they have two things in common: both are contemporary and have been made during difficult circumstances, away from “home”. One is anchored in refugee-reality, imprisonment, suffering and loneliness; the other, as the title of the ensemble of artwork of which it is apart puts it, in exile, dreams and longing. The former is a literary work, a novel of which the traumatic now of writing precludes the development of a narrative as we would expect in a novel. Instead, it has a strong autobiographical voice and is full of philosophical musings, written in an improbably difficult situation. The latter is a visual artwork, one or two of a series of 89 drawings made on a kitchen table by an artist who was exiled by the 2020–2021 lockdown. It is not autobiographical, although, in a sense I will explain, it is (at least a little). Bringing these two works together can only fail, but failure is perhaps also a useful, instructive performance of the impossible. Thus, the failure softens that tension, which, I speculate, is ultimately the goal of this Special Issue.

Let me briefly introduce the two

persons–artists–voices–speakers I will try to make speak to each other, although they have never met and probably do not know each other’s work. The Kurdish-Iranian journalist Behrouz Boochani fled his country, where he was in danger of persecution, as journalists so frequently are. He planned to seek asylum in Australia, a country we tend to take as a model for democracy and freedom. Alas, instead of being welcomed as a refugee, as he had rightfully expected, or at least hoped, he was imprisoned without any legal formalities on Manus Island, in the middle of the ocean. There was a detention centre that was so scandalously illegal that it ended up being closed by the government of Papua New Guinea, normally an ally of the government that had opened and used it. For Boochani, as a refugee-turned-prisoner, the traumatic situation of not knowing if and when his plight would end lasted a full five years. As readers, we do not receive that end as the happy ending, although the revolt of the prisoners in the last chapter suggests it might be coming. The interlocutor I will stage in relation to him is the Indian visual artist Nalini Malani. She was less than a year old when the division of British India into India and Pakistan took place and her family was displaced to India. To her life-long experience as exiled was recently added the year-and-a-half-long impossibility of returning home, due to the COVID-19 lockdown, after she had installed an exhibition in Barcelona at the occasion of the Miró Prize she had been awarded. She reached Amsterdam on the last flight. Of course, I am not comparing the respective situations in which these artists made their artworks; no comparison is possible in this respect. I will only try to deploy some aspects of each work to shed light on the other. Instead of comparing, I will address the two works, each speaking in their own “voice”, attempting to stage a potential (and of course, entirely fictional) dialogue that helps understand the “and” in the title of this Special Issue.

3Boochani wrote his gripping novel, if “writing” is even the appropriate verb and “novel” the right noun, in the shortest fragments. These he sent, one SMS message at a time, from his prison cell, hence, in fragments, after writing them on a hidden mobile phone. His title,

No Friend but the Mountains, speaks to the utter loneliness in which he was caught. That loneliness is the core of the situation. This is paradoxical in itself, given that much of the text describes the inhumane crowdedness of this prison, where sounds and smells of the other hundreds of prisoners physically assault him constantly. Malani drew her works on paper in much more fortunate circumstances. Prevented from going home, she nevertheless worked in comfort and was not alone. Still, as she titled the series she made in one year, she was full of

Exile—Dreams—Longing (

Malani 2021). In a very different, much more bearable situation, her working circumstances also left much to be desired, with her usual studio and materials lacking, and she had no choice but to work on paper. “No choice” is a phrase that will recur in this essay, although here, it is not at all tragic. The phrase also characterizes the involuntary decision of refugees to leave their homes. Malani, especially, worked under a certain psychic duress, not only because of her exilic situation but also because she took upon her and addresses in her work not only her own life but also that of others, in past and present. And whereas her autobiographical voice, which is very characteristic and unmistakably hers, shines through in certain works from the series, not only in the words and images but in the mode of making itself, those others are constantly present, and the violence against them hurts her, too. This is why I cannot see it as non-autobiographical.

4What both artworks have in common is a strong sense of the intricate intertwinement of artmaking and thinking, performing and acting, “on” or “around” the disempowerment that both exile and refugeedom entail (please pardon the neologism I use). This serves to indicate a state, without specifying why and how, where and how the people we call refugees are at any one time. In a dialogue with his translator, Boochani calls his SMS-based patchwork that ended up a novel something like a philosophical performance when he says in the essay that follows the novel in the publication I am citing that the book “is a playscript for a theatre performance that incorporates myth and folklore; religiosity and secularity; coloniality and militarism; torture and borders. […] we act out our ruminations, we embody our thinking… argument is narrative… theory is drama”. (p. 296)

This expression of the interdisciplinarity of the literary text as philosophical, performative and also “imaging”, to use a verb that takes the visuality from the word imagination, forcefully foregrounds thinking. Moreover, this expression “argues” that these aspects are best seen as integrated. In this sense, his novel is also an essay, as are Malani’s drawings. The “play” in the word “playscript” and the integrated elements that follow suggest that his novel also exceeds autobiography and that the imagination participates. This integrative nature, in all its aspects, is the primary common element between the two artworks—the ground that makes the dialogue between them possible and fruitful.

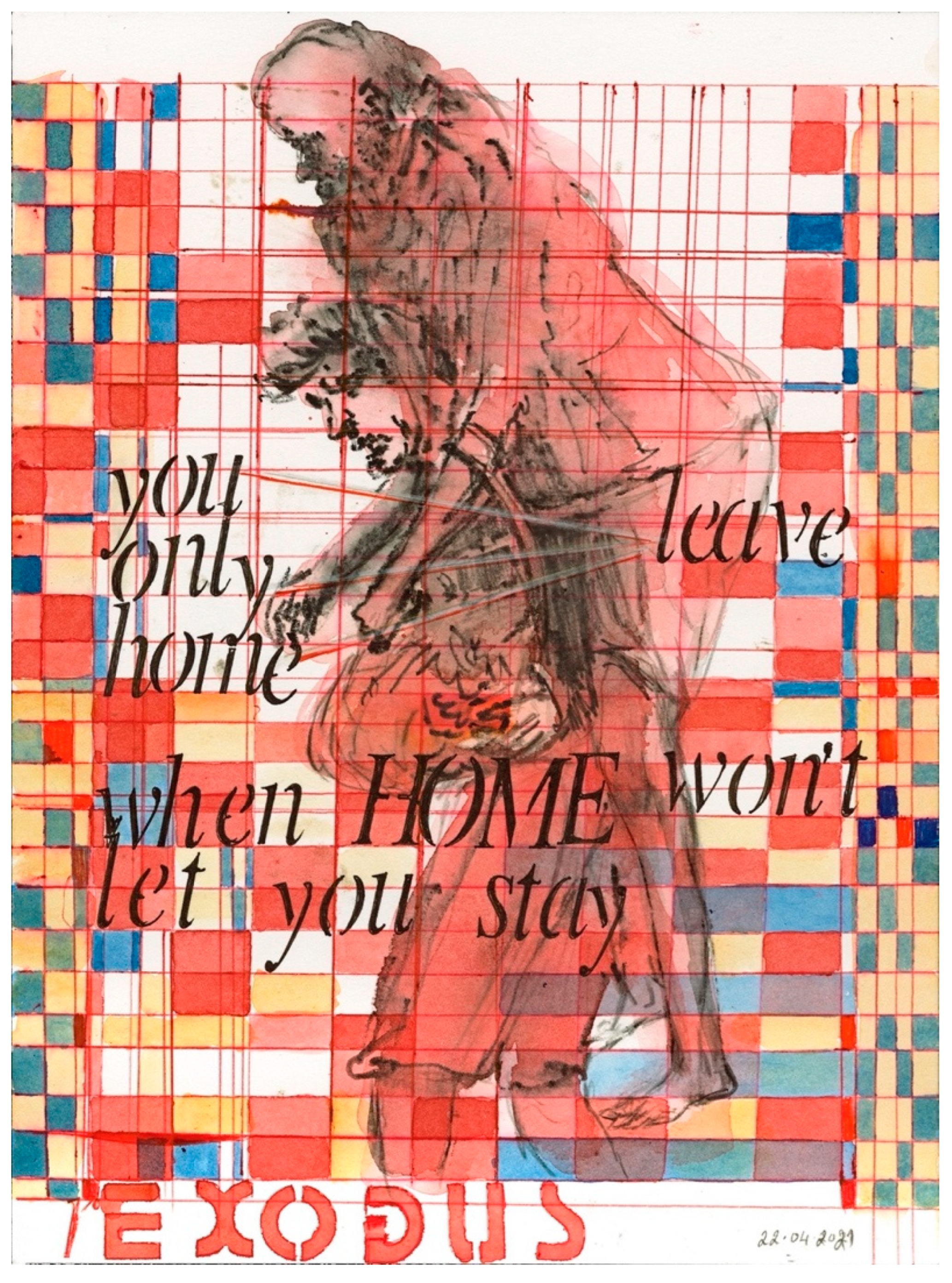

5Malani’s drawings frequently also contain texts, quoting poems by others, statements by herself, such as that in the drawing I bring in here (

Figure 1), strongly positioned-visually on the sheet in ways that make more of the words than just words: “You only leave home when HOME won’t let you stay”, with the multi-layered word EXODUS, in somewhat broken letters, at the bottom of the sheet. The two artworks are both essays in the sense of attempts, but we must not expect decisive answers. In spite of the difficulty of truly saying what is at stake in the lives of refugees, prisoners and exiles, the failure to manage doing so is their most crucial achievement. That may well be the most enriching thought—in the sense of Boochani’s statement about his novel I just quoted—that they both create and propose. Both are complicating their “primary” medium, and thereby they counter the routine-produced indifference that the everyday presentation of the horrors on the news cannot avoid conveying. In this way, they both address my first concern: art against television news, or fast consumption of information resisted by intermedial, entangled, slow engagement. Engagement, as distinct from consumption, can only occur when it is slow.

With the qualifier “slow”, I am alluding to an important book by one of the editors of this Special Issue,

Slow Philosophy (

Boulous Walker 2017). This Australian philosopher, Michelle Boulous Walker, explores and recommends essayistic reading as a strategy for slowing down reading. Slow reading is an activity that is under threat of disappearing due to internet culture, with zapping as its primary skill. The term “screenagers” for today’s young people says it all. Rereading Boulous Walker’s plea for essayistic reading as I am writing this essay, I can only share what I suppose she must have felt while slowly reading that SMS-based novel that came out of her country’s policies. This resonates with my own deep shame when confronted with the injustice committed against my neighbour. For, this was done in my name, as a European citizen who is not a refugee but has the ethical duty to encounter refugees in the migratory culture in which we live, and for which we are all responsible. Slowness is of crucial importance if art in our culture, our migratory culture, is to remain a fertile source for thought. Slow against fast, unique against routine inducing indifference, I join Boulous Walker’s plea, and with her, I believe this is the crucial change that our culture badly needs. We will see if it can also dissolve the tension between the necessary and impossible representation of refugeedom. That tension emerges primarily from the similar tension in the trauma that refugeedom produces.

But the tentative nature of the essay entails more. I keep returning to Adorno. The following passage characterizes the philosophical tone—a nuance that goes well with his use of “form” in the title:

The essay allows for the consciousness of nonidentity, without expressing it directly; it is radical in its non-radicalism, in refraining from any reduction to a principle, in its accentuation of the partial against the total, in its fragmentary character.

(1991, p. 9)

Along with the series that comprehends the rejection of reductionism, “partial”—mind the ambiguity of that word!—and “fragmentary”, in particular, seem to bring us closer to what an essay can be or do. Both words resist the idea of the total, of the encompassing whole and also, in its shadow, the totalitarianism that currently seems to rule in so many places of the world. In addition to the opposite of totality in the sense of wholeness, “partial” means several things. It also means subjective, as in acknowledging that what the essayist brings forward cannot pretend to be an objective, factual truth; passionate, in that the holder of the view developed in the essay cares about it—hence, is “partial” to it, as the productive ambiguities in English would have it—and rational, since partiality also encompasses the wish to persuade, which can only be accomplished through rational arguments. The latter meaning fits well with my attempt to ride the fine line between academic and non-academic work. As for “fragmentary”, an idea that will return below in Boochani’s novel, this accords well with the non-total(itarian). These two words, “partial” and “fragmentary”, foreground even more strongly that nothing can be whole, complete, objective. Boochani’s SMS messages and Malani’s eighty-nine artworks made on a daily basis, they could not be more “fragmentary”, hence, less “whole”.

In addition to being taxing and difficult, the word “essay” literally means trying, another fortunate ambiguity in English. Taking its toll on the peace of mind of the person trying, the latter is attempting to say something for which no ready-made (literary or artistic) genre exists as yet. Perhaps genre is not where we should look to understand the essay, then, but rather explore the word-name itself. The modesty, not only in the sense of the necessary discreteness and reticence but also of unpretentiousness, that the word “essay” includes is crucial. Trying, attempting, groping towards, fumbling, even floundering—that modesty itself acknowledges that nothing is perfect and also that no one does anything alone, that making something is not only enduring but also collective and social. This has been my attraction to video making, where even the illusion of such aloneness cannot hold. It also has a temporal consequence since it intimates the idea that “things”, such as artworks or films, are never finished; they are, as the saying has it, “in progress”, since “trying” is never over. They remain “in becoming”, to speak in Deleuzian, a concept tersely explained by

Archer (

2021). It is about process, not product, but it is important to realize that “essay” also includes “thought”. This is where the intellectual, to avoid the term academic, returns. One does not try something without, first, thinking about it. That thinking is necessary and cannot be performed alone. For this reason, I have myself experimented with this aspect of essaying in a particular film-cum-installation. One of my theoretical fictions or essay films,

Reasonable Doubt: Scenes from Two lives (2016), concerns precisely thought; the social, collective and performative aspects of the activity and the resulting ideas. The main character of that film is the philosopher known for his rationality, René Descartes—a reputation that my film attempts to complicate. According to the essayistic thrust of that film, thinking itself is tentative, and the philosopher demonstrates this, including in bouts of hysteria. Thinking, then, occurs in the essay mode. This makes the essay an important, indeed, crucial cultural phenomenon.

6 3. Intermediality

Let us try, then, to make fragments of the two artworks interact, in the sense of speaking to each other. To open this conversation, I return to antiquity. When the Trojan hero Aeneas fled from the burning city of Troy, he carried his ageing father Anchises on his back. This much we know from the millennia-old legend in the epic traditions. The flight turns them into refugees, and the long history from today to classical antiquity and back demonstrates that the idea that migration and refugeedom are specific to our time is “preposterous”, as I have called it, with an ambiguous qualifier that means both ludicrous and something else altogether. I came up with that word in a theory of historical time as reversible or “pre-posterous” (now with a hyphen), that is, two-way, a dialogue between times, or “inter-temporality” (

Bal et al. 1999). This is one reason I began to consider Malani’s series with its final image, which I read retrospectively. I immediately saw it as an allusion to the Aeneas–Anchises flight, so that the final image goes back to the oldest tradition. Although when I asked her, the artist said it referred to the Rohingya people chased out of Miramar in 2020, this seemed exactly right to me: to bind antiquity and our current time together. In Malani’s last, but not concluding, image of her series of 89 drawings, the strong young man carries his father; or at least I assume he does, knowing the legend. Drawing and painting, or staining, together already produce a hint of intermediality. Both figures are drawn in light black or grey ink, coloured in terracotta, the colour of burnt earth, in Malani’s typical watercolour-like staining technique. Terracotta is the predominant colour in the 89 drawings of

Exile—Dreams—Longing, a choice which, in my interpretation, hints at the artist’s commitment to respecting the earth, working with it, elaborating it, as the -cotta ending of the colour’s name suggests.

7Here and there, the colouring exceeds the lines, as would happen with watercolour, and has different layers, and both figures exceed the frame made up from hand-drawn rectangles in terracotta-red lines, filled in on the sides with different colours, mainly terracotta, yellow, blue and green, of different levels of opacity and semi-transparency. The middle part of the top half is left un-coloured, making space for the two superposed heads of the old man and the younger one, whom we take to be father and son. They do not fit the image neatly; a cropping is needed, which hints at the imperfection of the state of refugeedom as well as at the fundamental incompleteness of the essay. The father’s head exceeds the frame on the top; the son’s legs are cut off at the bottom. As an entrance into the issue of intermediality between the two artworks, it matters that, whereas Boochani’s prose is full of imagery, Malani tends to integrate words in her visual works. She does this in a visually significant manner. At the level of the young man/Aeneas’s breast, on the left side of the image, the words “you”, “only” and “home” are written in printed letters but disposed somewhat irregularly, one word beneath the other. All three are bound by double oblique lines, clearly drawn with a ruler, in terracotta and grey-green that cross over the figures to the right side of the sheet. There, these lines come together to (literally-visually) point at the word “leave”. That word stands on its own, on the other side of the words addressing the “you”, either the second person or a generalized subject. A bit below the younger man, on top of Aeneas’s waste but overruling the figure’s substance, we are given access to the connection between the three words and the one that is key to the refugee status: “leave”, as in leave behind, quit, abandon. Leaving is the act, what happens, but the isolation of that word on the right side of the sheet is telling. It visually embodies, figures, the separation that leaving entails. The three double lines forming a triangle and arrow foreground the word’s central importance.

The connection between the left side towards which the figures walk and the ominous words “you”, “only” and “home” there, on the one hand, and the single word “leave” on the right, only comes in once we have absorbed, slowly, these two sides of the words. This connection is the reason, the profound motivation, the lack of choice, which defines refugeedom: “When HOME won’t”, and on the next line, “let you stay”, “leave”, then, becomes an imperative: “Get out of here!” The separation figured in the isolation of the word “leave” resonates with the emphasis figured by the capital letters in “HOME”. Home, the basis of your existence, kicks you out by means of violence: either poverty or persecution. These explanatory words are written over the bodily tools for leaving, the legs, on the level of the old man/Anchises’s calves and the young man/Aeneas’s thighs.

The figures, glued together, walk in the direction of the left, on their way to the West. Their departure from the East is motivated without explaining it in political terms. “Home won’t let you stay” means that whatever the actual reason, you have “no choice”. In the legend of the destruction of Troy, the situation is war, and the city is burning. Both Homer and Virgil tell the story in their famous epics. These two figures are refugees. There can be other reasons than the burning city, such as censorship, hunger, fraud, violence or anything else that causes the strong fear that, according to Boochani’s childhood memories, “ran deep within our bones” (p. 264). The fear is what kicks you out, away from what you always assumed to be your safety ground. The lack of wholeness, of coherence, stays with him, as he writes in another visualizing passage: “… the images form into coherent islands, but they never lose that sense of fragmentation and dislocation.” (p. 265)

The direction east–west is, on the one hand, a traditional (in the West) but hardly adequate view of people’s movements when they flee. It connotes the division of the world in rich and poor, expressed in such bizarre numbers as “first” and “third” world (of “second” we hardly ever speak). Moreover, it matches both Aeneas’s escape from burning Troy to Greece and Malani’s own back-and-forth movement from India to Europe, in which she got stuck in 2020—and which sealed her solidarity with the Rohingya refugees. On the other hand, when we consider Boochani’s itinerary—and this is another moment where the two works speak to each other, in the mode of discussion—going-fleeing from Iran to Indonesia to Australia is a reversal of this habitual assumption, thereby undermining that belief’s semantic stability. This is one aspect of the shocking account that challenges so many of our assumptions about migrancy and refugeedom as well as about which countries are oppressive and which celebrate freedom and boast that beautiful value.

One example of an emphatic West–East movement is William Kentridge’s 1999 animation

Shadow Procession. There, an endless stream of shadow figures, cut-out profiles, some of them carrying household furniture on their backs, walking and walking, present an image of migration of people on the move, clearly refugees, from west to east. Kentridge is also a deeply politically engaged artist, and he has enough in common with Malani, in spite of enormous differences, to have compelled Andreas Huyssen, a brilliant German-American cultural critic, to write a book about both, centred on the shadow plays they both make to embody political memory (

Huyssen 2013). Using the technique of a Brecht-derived puppet theatre, Kentridge’s work shows one-directional, relentlessly eastward movement. Realistic representation is cast aside in favour of a mode of presentation that leaves to the viewer the option to flesh out in what mood to watch these relentlessly moving rows of displaced people, figures with their burdens and their stacks, including a miner dangling from the gallows, including workmen carrying entire neighbourhoods and cityscapes. This ambiguity of mood—“no choice” or, from an opposite perspective, freedom—accounts for, or rather is enhanced by, the visual and musical discourse of vaudeville that acoustically “colours” the seven-minutes long animation in black and white, hence having no colours of its own. This is a merry form of entertainment that hits the viewer with its sudden moments of a “cruel choreography of power relations”.

8Boochani’s SMS messages miraculously ended up as a novel—an award-winning novel, seen as a literary masterpiece, translated in many languages. Like Miguel de Cervantes, author of the world-famous novel

Don Quijote from 1605 with a second part added in 1615, the author of

No Friend was captured and imprisoned for five years. The Spanish author wrote the novel afterwards. In both cases, there is no motivation for the captivity, no legal ground for it and, for the captive, no sense of its ending. Cervantes’s captivity was part of the then-common slave trade in the Mediterranean region, an early instance of our contemporary hyper-capitalism. Boochani’s was part of the Australian protectionism of the country’s borders. Both are unthinking, cruel and, for their victims, traumatizing actions. In other words, Australia’s refusal to help refugees turned them into what the author persistently refers to as “prisoners”. In both cases, the cruel and traumatizing treatment remains unmotivated. The temporality, or rather the lack of it, already signifies the state of trauma. The text begins with Boochani’s flight from Indonesia, first in long truck rides and then on a ship that soon turns out to have a hole in it, is ultimately wrecked and ends up capsizing. The description of alternating between fear and hope is contagiously gripping. After a last-minute rescue, the country of freedom he has been longing to reach, however, captures him, like Cervantes’s slave traders, without providing any reason. The moods described teeter from total fear and anxiety to jubilant joy and then back to the worst again. This subtly raises the underlying question of what the worst is: death or timeless imprisonment?

9As an opening hint to the intermediality of the novel as a whole, on page one a visual image literally colours the mood. The visuality is enhanced by the use of the present tense, of which W.J.T. Mitchell has brilliantly analysed the visual–political collaboration (

Mitchell 2021): “we look up at the sky the colour of intense anxiety”. The present-tense visualization continues on the second page: “The looming shadow of fear sharpens our instincts.” When the first-person narrator is finally rescued, he describes what happens as “a series of distorted and broken images”. (p. 42) Just as Malani deploys different media while staying in the genre of what she names “drawing”, Boochani calls upon the cinematic to depict the scene, using the primary medium of language to do so:

Just like a scene from a film consisting of a few frames, separated from one another but interconnected: hands waving; men on the brink of exhaustion; the dark of the ocean; the presence of the motorboat; the dark ocean; bodies pulled up into the boat, completely debilitated; and finally the sound of the motorboat moving away, and the wake it produces.

(p. 42)

The audio-visual medium of cinema, itself a mixed or intermedial medium, is required to represent the scene the least bit adequately. This I see in the final mention of sound, but the broken quality of the images barely shows what we can nevertheless see and hear—in fragmentation only, like the first recipient of Boochani’s SMS messages. However, the same brokenness also imports temporality, which may well be the primary reason for this appeal to the cinema.

A film is not the news. This fragmented film contrasts with what German artist Monika Huber critiques as the systematic speed in her current project

Archive One Thirty, pointing at the one-and-a-half minutes which the television news devoted to worldwide political protests between 2011 and 2021. While the news always tries to save time to make items fit into the tiny, pre-established timeslots, Boochani, like Huber in a different way, searches for means to convey endlessness. Huber’s work consists of an archive of snapshots from television screens and press photographs that she has modified, mostly through over-painting them in ways that Malani would recognize as staining and Boulous Walker as slowing down. Huber has been doing this, intervening in “official” information, for a long time, and the result is very powerful, impacting the notion of information itself.

10The intermediality may be more eye-catching in Malani’s image than in Boochani’s novel because we see letters in her visual work, whereas the novel is “only” writing. However, the following passage demonstrates that intermediality can manifest itself within a single medium:

The prison is besieged by fences encircling its outer rim. Fences cordon off the bathrooms, and through their wires are tied numerous small pieces of cloth. These pieces of cloth look like ribbon and are remnants from the people who were held here before us. The ribbons of cloth are withering away due to the intense sun; each one represents a memory, the ribbons are a series of recollections, all of them hark back to another lamentable time.

(p. 111)

Already, the metaphor “besieged” turns the description of what is visible into a theory of what cannot be seen of imprisonment: the combination of hostility and surroundings. This makes the invisible visible. The triple repetition of that one descriptive element, the “pieces of cloth”, insists on the visual presence of the experienced past. What follows is a theory of memory as it is attached to, and dependent on, materiality, the visuality of the pieces as well as the relationship of memory to the past, where the remembered happened, and the present, where one performs an “act of memory”. In this short passage, Boochani brings visuality, literary rhetoric and thinking together.

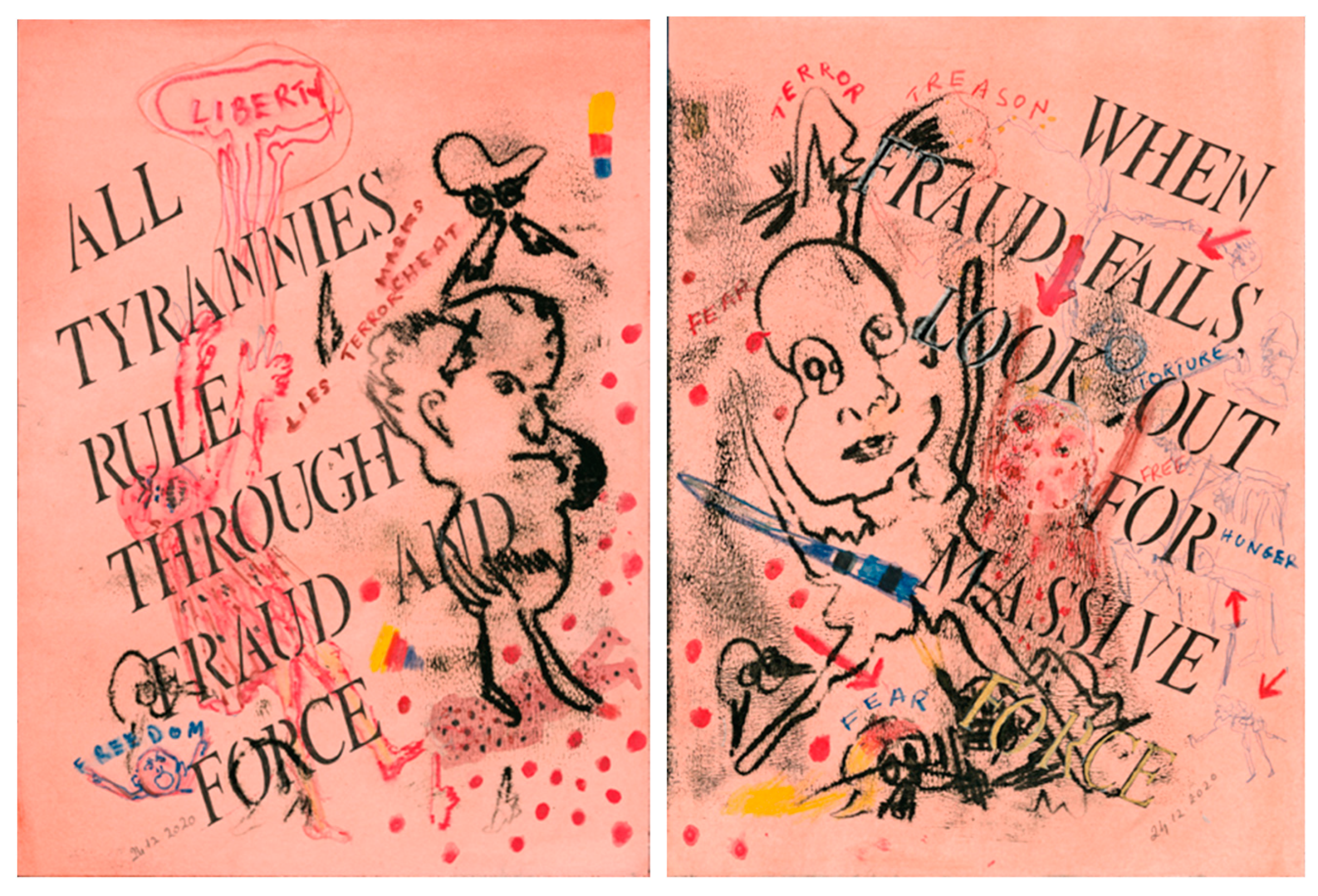

11For an intermission, and to give a sense of the continuity in Malani’s way of carrying the burden of her political commitment, I offer two other sheets of the collection (

Figure 2). On Christmas Eve, 2020, Malani drew this diptych. The two images ended up as the cover of the beautiful 2021 book in which the 89 drawings are reproduced in actual size and on the same paper on which they were made. I introduce them here in their numbered order, although on the book cover the nr. 42 is on the front, the nr. 41 on the back. I see this reversal as a well-deserved pushing back of the tyrant and a bringing forward of childhood fear quoted above, the terror-stricken child. Indeed, the figure on nr. 42 reminds me of Boochani’s expression.

On the image nr. 41, the figure of the same size looks more like a monster. Of course, the written words make it hard to see it otherwise. “All tyrannies rule through fraud and force” is a clear political statement, and the second image draws, or draws out, the consequences. Behind the statement of nr. 41 are some small figures, one of which is drawn in terracotta and looks like the young girl Malani frequently calls up in her worldwide autobiographical tenor, her version of herself and/as Alice. The thought bubble the girl releases to fly upwards like a gas-filled balloon cries out for the freedom that the monster is destroying through fraud and force. Her light-coloured shape cannot overrule the black-outlined monster, who is, in any case, looking the other way. The monster, looking away, is callously walking on a small, headless human figure. Underneath it, two hands, one drawn in red, one in black, point to it: the red one to the neck-without-head, the black one to the monster stepping on it.

The second image holds a warning, a piece of advice: “When fraud fails, look out for massive force”. The failure of fraud does not help. The drawing says this to the child who seems to be running away, as a prediction of refugeedom to come and motivated by the words in small letters: terror, treason, fear, torture, hunger and fear again. “Fear” is written twice, as the emotional consequence of the other nouns. “Force” is difficult to read, because it is written not in the black of the main words or the colours, red and blue, of the other nuances of states inflicted on the child and its people, but in the gold of the triumphant capitalism that is able to buy weapons to perform the other things mentioned. The arrows that pervade the image connote causality. A blue arrow-like shape, perhaps a knife or a missile, flies over the child-figure’s body. No Friend but the Mountains almost seems to comment, in support, on this powerful but terrifying image, when we read:

“A few people appeared who chanted in unison, ‘Freedom! Freedom!’ This encouraged the others to band with them and join in. However, it seemed from the very beginning that fear had seeped in”.

(p. 335)

Referencing nr. 89 once again, if I now seek to bring Malani’s and Boochani’s works in dialogue, I would say that the (audio) visual aspect in the writer’s evocation resonates with the work with lines in the visual artwork. The lines are both straight (drawn with a ruler) and somewhat irregular, in size as well as in colouring, and a tiny bit wonky. This is not negligence (“sloppy”) but, on the contrary, a carefully staged tension, through that so aptly named tool “ruler”, between the attempt at order and the inevitable irregularity of hand-made work, which is the artist’s signature and embodies her commitment. This in turn reverberates with the behaviour of Boochani’s fellow prisoners, who are obedient to the rules but nevertheless never perfectly orderly. The powerful visualization of words in the drawing somewhat irregularly placed and the letters of the final word broken helps Malani’s participant-viewers to an understanding that the traumatized Iranian writer cannot offer precisely because of the trauma; the traumatized cannot reach the violent event in their memories. Boochani needs Malani’s help. The millennia-old war story does not need unpacking; all we need to see/read is that the refugees have “no choice” in the wake of that imperative or kick, figured in the isolation of the word “leave” that the disposition on the sheet has turned into an imperative. This is what matters today for the political decisions through which refugees may or may not obtain a humane existence, after having endured the life-threatening, breath-stopping and heart-breaking plight of their flight.

And conversely, the harrowing evocation of the night when life and death were near-exchangeable—notice the repetition of “dark” (a colour) and “ocean” (the limitlessness of the space of danger) in the description—gives Malani’s succinct, crystal-clear and generalizable explanation that flesh and blood substances are needed to make it concrete a visual support, even expressed in language. However, concrete does not mean anecdotal. Instead, it is an issue of reversal. The old man sitting on the shoulders of the younger man—or is he walking beside him, standing or hanging over the young man’s shoulders?—amounts to a reversal of “ordinary”, normative roles, for, in normal sociality, parents are supposed to take care of their children, not the other way around. This reversal

figures the absurdity of the refugee situation, where, at least per Boochani, the “land of freedom” (p. 65) becomes the worst oppressor. This in turn figures the reversal of what humane duties would prescribe: to welcome and help those who had “no choice” so that their presence among “us” in migratory culture can work as an enrichment of that culture instead of a problem. Taking your aging parent on your shoulders is obvious, normal, in no-choice situations.

12How would our opinions be transformed if we began to see the incoming novelties as an enrichment indeed? Just think about it: how often are we not mesmerized by the originality that comes with films from far-away cultural settings, what is called “world music”, or artworks that exhibit images, figurations of situations we would not have seen otherwise, and different habits of dress and hairdo. One example is a “migrating phenomenon” I have studied and made a film and installation about to visually grasp it better: the simple, tiny habit of eating sunflower seeds in public space. This habit has been imported by newcomers from countries where it is the normal way of sharing public space. How do the older residents see this imported habit? It results in dropping the shells on the sidewalk, which some might consider dirty but others a nice addition, visual and auditive, to the streets of a city like Berlin, formerly too neat. It entails the smell of the roasting, the cracking of the shells under the shoes of walkers; in short, all five senses are involved. Most importantly, it offers occasions for people from the resident culture to speak with the “newcomers” about the meaning of this habit. Hence, in all sorts of ways, in small phenomena such as this eating habit and in larger issues, the social fabric and what Chantal

Mouffe (

2005) calls “the political”, meaning the domain where disagreement and discussion lead to better understanding instead of enmity, can be improved, be intensified and solicit discussion and changing one’s opinions. The political is not the politics of parties and tyrants, but the domain in which we all participate. In this domain, I propose, we must stretch out a helping hand to those who not only had “no choice” but also lost their ability to remember, to be aware and to live in time. This is why trauma cannot be represented yet nonetheless must be addressed.

13 4. Trauma and Representation, an Impossible Necessity

Indeed, the compulsion to make these two artworks speak to each other, instead of simply interpreting them separately, emerges from the predicament of trauma, which in my view is the inevitable consequence of the profound disturbances that develop “when HOME doesn’t let you stay”, in other words, when you have “no choice”. First of all, to obtain some clarity about that starkly and darkly confused issue of unfathomable distress, I propose we distinguish carefully between three aspects of trauma: its cause, the situation or state that cause produces and the state of near-powerlessness of bystanders who yet wish and hope for a possibility to help people suffering from it. I have formulated this distinction succinctly as follows:

violence—an event (that happens)

trauma—a state (that results)

empathy—an attitude (that enables)

The subjects of these three facets are different: the violence is performed by an agent (the culprit, the perpetrator); the traumatised subject is its direct object, the victim; and the subject of empathy, for the artworks, their “second person”, is the social interlocutor, who can potentially help them overcome it, at least partially. To avoid confusion between event and state and between perpetrator and victim, it is helpful to foreground the non-evenemential, enduring situation of captivity. This is what produces the timelessness, hence my choice of Boochani’s, as well as, earlier, of Cervantes’s novels. This avoidance is also important with respect to the role and attitude of witnesses, which activating art can encourage.

As I have argued elsewhere (most recently in my 2022 book), the term “trauma” has been terribly over-used in the aftermath of discussions of cultural memory in the 1990s, when Holocaust survivors and witnesses started to disappear. That end of the possibility of consulting eye-witnesses made a renewed examination of the issues the Holocaust had generated most urgent. However, as often happens when an issue becomes widespread, from that moment on, the term began to float around too frequently and easily to remain useful as a concept for analysis and understanding. As a consequence, I would say, it has practically lost its meaning. (

Bal 2022, chp. 6) The issue of refugeedom and the trauma I consider this state to entail induces a serious rethinking of trauma, for this flattening of the concept is unacceptable since it brings up a real and very grave issue of today’s cultural moment, in which refugeedom is such a burning issue. We are surrounded by, we live among, traumatised people.

The un-representability of trauma, serious as it is—a seriousness that in my view sits at the heart of this Special Issue—might threaten to relegate it also to incurability. We cannot let this happen. This would be in accordance with Freud’s view (more on this below), which is especially intolerable since it entails simply giving up on human beings. Therefore, I have been preoccupied with this in various video projects. Most recently, in my

Don Quijote project (2019), as well as in others, especially the earlier and co-made film and installation project

A Long History of Madness (2012), the attempt has been to

present, but not re-present trauma. We attempted to give it

figurations that do not infringe on the injunction of modesty, do not enforce an understanding of those who can only survive through their efforts to forget and cannot even reach the memory of what happened and caused their trauma. However, the attempt was to bring it to the awareness of those social interlocutors who might be able to stretch out a helping hand instead of turning their backs on the traumatized, considered “mad” and therefore frightening. Don Quijote’s alleged madness is legendary, but I speculated that he was not driven mad by his excessive reading, as the cliché reading of the novel has it, but by horrors in the real world, with the author’s and the character’s captivity at the heart. For this purpose, I have been thinking experimentally, in other words, attempting-essaying, how to deal with the contradictory aspects of the trauma-

and-art encounter. The two artworks discussed here, in their dialogue, help bring this predicament closer not to a solution but to an acceptance and endorsement of the contradiction of impossibility and necessity, respecting and following up on both.

14For this, Malani’s riveting and demanding image, which will hold the viewer’s attention for quite a long time, is compelling. It is precisely in the irregularities, the broken letters, the somewhat left-leaning lines, the technique of layering water-colouring or staining instead of a perfect opacity of colours and the paint spilling over the lines of the drawings that the time-consuming effect it generates lies. Both artworks demand slow engagement, enduring commitment to what they present, and in dialogue, they exchange between an intertemporal historical recall (Malani) and an a-temporal, because of trauma, fragmentation (Boochani). In the traumatic situation, time itself breaks down. The allegedly still image that halts the rapid flight from the burning city for viewers stopped in their tracks by the slight irregularities, the gripping drawing lines and the colours that remain subdued, joins, in this temporal aspect, the harrowing descriptions, repetitive and elongated, and the unbearably cruel practice of, for example, the “queuing as torture” of hundreds of prisoners under the burning sun. (pp. 189–221) Together, they can contribute to overcoming, or rather attempting to overcome, the contradictory nature of binding refugees to representation. Together, also, they can call upon the social interlocutors who are indispensable, as witnesses and participants, for the improvement of the social fabric of migratory culture within which refugees must be welcomed, to give them a second chance to the life they are entitled to, as per human rights.

In the case of my video installation projects, it is the visitor who is the primary addressee of the exhibition, its interlocutor and the interlocutor of the fictional figures brought to life. These exhibitions aim to activate visitors to become such empathetic subjects. The display is meant to have performativity in this specific sense by sharing the different aspects Boochani mentions in the statement quoted above. The two artworks I discuss in this essay each have, of course, their own performativity, embedded in their respective media, situation and temporality. The potentially helpful interlocutor is the viewer, for Malani, and the reader, for Boochani. Both are hooked by the artworks to

stay with the fear, to abduct Haraway’s title once again, but are these functions truly distinct? This is the reason why I try to bring these works together, not in an impossible comparison but in the way their distinct media reach out, speak to each other, enriching both while respecting their differences. What I am trying to suggest here is that they can also be made to perform in interaction, creating the beginning of a larger cultural ground on which to stand. Perhaps the way the feet of the figure of the old man/Anchises in Malani’s work appear to stand—not that they have anything to stand on—alludes, figuratively, to the need for such a ground. Between my interest in closely analysing artworks, the myopic detailing that I have often experienced as very productive, and my simultaneous wish to foreground migratory culture as a greater environment where the analysis spills over into society, my attempt to bring two artworks into dialogue is the first step, one that may, perhaps, become wider and wider, like the ripples of small waves in water after a stone has been thrown into it.

15A comparable small plot of ground can emerge from a dialogue which we have attempted to conduct before. When it comes to the contradictory relationship between the trauma that threatens in refugeedom and the subsequent need as well as impossibility to represent it, I have examined the predicament in relation to representation. Françoise Davoine’s book

Mère Folle from 1998 (

Davoine [1998] 2014) was the central source and resource. Michelle Williams Gamaker and I made the video project based on that book (

A Long History of Madness). In her book, this extraordinarily committed author, a psychoanalyst, deploys her special kind of “theoretical fiction” to argue with—not against—Freud, the inventor of the term “theoretical fiction”. Freud proposed this term to justify the obvious fictionality of his

Totem and Taboo. Davoine takes Freud to task, within his own invented genre, about the possibility to analytically treat psychotic patients, most significantly the traumatised. Freud considered this impossible because, he alleged, these patients cannot perform transference, which is indispensable for the psychoanalytic cure to work.

Reversing the burden of proof or the possibility of medical success, Davoine claims that psychosis, the madness resulting from trauma, is mainly inflicted by social agents or situations, the perpetrators of the violence. Therefore, society has the duty to help and cannot hide behind theoretical suppositions. If the method of psychoanalysis poses a problem for the treatment of traumatized people who need it so badly, then it is the method that must change, rather than locking people up in institutions or turning them into zombies by feeding them drugs. This fits well with my fourth and fifth background concerns. For this purpose, Davoine revised some tenets of the Freudian method, and with great success, both theoretically, and in the treatment of patients. In our video project we present these revisions. One revision matters most to me: instead of the analyst sitting behind the patient laying down, who cannot see the analyst, they sit opposite or next to each other.

16Cervantes had understood, as an “experience expert”, the core aspects of trauma at a time that the term, the theory and the attempts to remedy it were not at all available. One of these aspects is time. Not only is time stopped in its tracks, halted and stretched out; it is also frequently interrupted, but such interruptions do not restore the everyday experience of time. Instead, they impose a dramatic re-enactment on the disempowered subject. Another aspect of trauma related to time is the movement of the invoked images of actions. Traumatised persons, because they cannot even consciously recall the trauma-inducing violence, are, however, also locked up, alone within themselves. Boochani reverts to that experience several times. That loneliness makes the traumatized vulnerable to the assaults of the trauma, which they cannot master by the narrativity of memory. Instead, these assaults become a drama inflicted on them. In Boochani’s novel, the most striking, empathy-inducing emotional realm is where loneliness and crowdedness go hand in hand. This is also where the senses participate: the sound of others, the smell of their sweat, the inevitability of touch due to lack of space and the seeing of hostile eyes converge in the hunger that drives the prisoners to that disgusting queuing, which the narrator considers “as torture”.

This insight into trauma as a drama that imposes itself from the outside is the core of the work of French psychiatrist Pierre Janet, a colleague-intern of Freud’s at the Paris Hospital La Salpétrière. Janet’s work was neglected until the late nineteenth century in favour of his more famous fellow intern. In a very useful article,

van der Kolk and van der Hart (

1995) return a century later to Janet for a rethinking of trauma in the 1990s. They take issue with the standard conception of

repression as the motor of the creation of the unconscious. Instead, they draw attention to the difficulty of incorporating trauma into narrative memory, so lucidly explained by

van Alphen (

1999), who therefore characterizes trauma as “failed experience”. This makes repression impossible, for there is nothing to repress. Instead of the focus on repression, which was the crucial concept in the then-successful psychoanalytical theory of trauma, Janet, and in his wake Kolk and Hart, propose more attention for

dissociation. That concept already hints at the multiplicity involved in what is termed schizophrenia. In narratological terms, repression entails ellipsis, the omission of important elements in the narrative. Dissociation, instead, doubles the strand of the narrative series of events by splitting them off into a side-line, called paralepsis. Repression interrupts the flow of narratives that shape memory, whereas dissociation splits off material that cannot be integrated into the main narrative. The over-spilling of colour in Malani’s staining seems to hint at such doubling and the resulting multiplication.

Sparsely, Boochani explicitly mentions the concept of trauma a few times, but his novel mostly consists of representations of what can only produce trauma—the cause, not the state itself, if we follow my tripartite summary. The most terrifying one is the constant merging of absolute loneliness and suffocating crowdedness, both making life impossible. When he mentions the word, he is talking about the collective trauma of all those who made the horrific journey with him. He explains: “The collective trauma from the journey is in our veins—each of those boat odysseys founded a new imagined nation”. (

Boochani 2018, p. 124) He then proceeds to explain what the prison system does to rupture any attempt at community: “In this context, the prison’s greatest achievement might be the manipulation of feelings of hatred between one another” (p. 125) But when he talks about himself, the word “trauma” does not occur. Instead, it is the multiplicity of personalities that is most striking, a schizophrenia figured by colours: “I feel that I am being taken over by multiple personalities: sometimes blue thoughts parade through my head, and sometimes grey thoughts. Other times my thoughts are colourblind”. (p. 130)

These words do not constitute a representation. It is no coincidence that this traumatized author manages to express with such clarity what it is to be traumatized through the deployment of colours. Visuality plays a major part in writing, as, per Malani, vice versa. Hence the need to continue our efforts to understand what it means for a human being to be locked up in refugeedom, without resorting to representation, with its inherent problems. Figuring, or figuration, is a more adequate mode of saying the unsayable, and in the dialogue with Malani, colour is the primary tool.