1. Introduction

Since the emergence and popularization of international non-governmental organizations (INGOs) in the post-World War 2 era, the sector has been largely characterized by a handful of large, ‘professionalized’ organizations that receive a combination of private donations and official development assistances (ODA) to carry out development projects in the global South. These INGOs have become the face of the sector receiving exclusive attention in both the academic literature and development circles. However, over the past two decades, there has been a significant spike in the creation of INGOs in the global North that carry out international development projects in the global South. Most of these INGOs remain small as grassroots organizations that rely exclusively on private donations and volunteers, with aspirations to remain that way. In addition to these two broad categories of INGOs, there is an emerging class of INGOs with aspirations to scale-up and join the ranks of ‘professionalized’ INGOs. This study focuses on these INGOs in transition to explore how they differ from the larger INGOs with government funding and their pathways to scale.

Globally, there are 10s of thousands of INGOs that manage billions of dollars and operate in nearly every sector (

Davies 2014). Given the extensive discussion and fear that governments may impose their political agendas through INGOs (

Barry-Shaw and Jay 2012;

Edwards and Hulme 1996;

Keck 2015), it might be assumed that governments are their primary source of funding. In Canada, this is not the case. In a typical year, Canadian INGOs generate over CAN

$3 billion in revenue. Less than 10% of that sum is provided by Canada’s government. A similar sum is provided by donors outside of Canada, largely from international donors to some of the largest Canadian INGOs (three INGOs account for 70% of revenue provided from outside of Canada: World Vision Canada, Plan International Canada and Care Canada). The vast majority of charitable giving to Canadian INGOs (~80% in an average year), is provided by individual Canadian citizens (

Davis 2019a). INGOs that secure government funding require a level of expertise that is demonstrated through engagement with and external vetting by development professionals, as well as revenue and operations large enough to win and manage federally funded grants. While an imperfect marker, we operationally define large INGOs as those that receive significant federal funding (over

$25,000 annually), the INGOs in ‘transition’ as those receiving minor federal funding (less than

$25,000 annually), and ‘grassroots INGOs’ to receive no federal funding. It is worth noting that there are exceptions in the Canadian sector. On the large side, the MasterCard Foundation generates the highest revenue of all INGOs, but does not receive any government funding, and several large evangelistic INGOs (e.g., Chalice and Gospel for Asia) do not receive government funding, yet they would otherwise demonstrate traits of large INGOs. Similarly, there are organizations that intentionally do not seek government funding based on organizational principles, such as Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch. However, Amnesty was not included in our database as less than 40% of its expenses were international. Human Rights Watch did pass that international expenditure threshold, but funding primarily went to Great Britain, and was excluded as we could not verify if these funds were used for humanitarian or development activities.

For decades, academic attention on the INGO sector has focused exclusively on the few large INGOs that attract significant government funding and, more recently, an emerging body of literature has explored the function and role of small-scale INGOs that are privately funded, and volunteer-based. Many of the largest INGOs run large and regular advertising campaigns and have a high level of brand recognition (as far as we are aware, no studies have been conducted on INGO brand recognition in Canada). However, there are more than 1300 registered Canadian charities with an international focus (

Davis forthcoming). Beyond research on accountability and funding (e.g.,

Lasby and Barr 2012;

Phillips 2012,

2013) as well as small-scale INGOs (

Davis forthcoming;

Davis and Swiss forthcoming), very little is known about these organizations and their pathways to scale. This study focuses on these overlooked ‘INGOs in transition’ to explore how they differ from large and small-scale INGOs as well as their pathways to scale. Drawing upon a unique dataset of registered charities in Canada, we explore the ‘scaling’ of the INGO and what, if anything, the pathways they experience tells us about how INGOs develop and expand. Specifically, we compare the effects of and comparative differences in overhead expenditures, organizational age, country coverage, full-time employees, funding sources, location, and religion to better understand what factors play a significant role for INGOs to scale up from small-scale to large organizations. Our results identify several patterns and strategies for INGOs to scale up, while also demonstrating the diversity of these among Canadian INGOs.

2. Context

INGOs founded in the global North have rapidly grown in number over the past two decades. Recent studies in the USA (

Schnable 2015), UK (

Banks and Brockington 2019;

Clifford 2016), Netherlands (

Kinsbergen et al. 2017), and Canada (

Davis 2019a;

Davis forthcoming) have demonstrated a near tripling in the number of INGOs from the late 1990s to mid-2010s, in all countries. The vast majority of these new INGOs are small-scale, privately-funded, and volunteer-based organizations operated by amateur development enthusiasts (although this is not always the case, exceptions include the expansion of established INGOs from other countries into new ones as new country branches as well as some INGOs that are relatively new but have significant financial support or previous development experience). This form of ‘citizen aid’ has been labelled as My Own NGOs (MONGOs) (

Haaland and Wallevik 2017), private development initiatives (PDIs) (

Kinsbergen et al. 2017), Grassroots International NGOs (GINGOs) (

Appe and Schnable 2019), and freelance altruists (

Swidler and Watkins 2017), among others. These small-scale development organizations have proliferated as our increasingly globalized world lowers entry barriers to engage in development work through relatively inexpensive international travel and instant electronic communication. The changes experienced in the last two decades have enabled more opportunities for direct connections between citizens in the global North and South. These organizations are typically motivated by embracing smallness, developing direct connections and interpersonal relations with beneficiaries, engaging in tangible development projects, and having substantial control over development projects (

Davis forthcoming;

Fechter 2019;

Fylkesnes 2019).

The increase in the number and diversity of INGOs is part and parcel of a broader trend in the decentralization of international aid, which represents one of the most significant changes to the sector (

De Haan 2009). While still in its infancy, the literature on citizen aid has characterized these agents of development as a double-edged sword. On the one hand, citizen aid might offer a complementary aid delivery mechanism with large INGOs and state agencies through direct people-to-people connections, enabling higher levels of altruism, and enacting more flexible and responsive approaches. Moreover, with exclusively privately-funded budgets, these organizations are not constrained by competitive funding cycles that reshape development projects to match donor funding criteria and put pressure to produce positive results to report back to donor agencies. On the other hand, small-scale citizen aid organizations are typically operated by volunteers and amateur development enthusiasts, which may result in high transaction costs for aid to reach communities, a narrow focus on ‘last mile’ solutions to address complex development problems, limited institutional knowledge about effective interventions, and the potential to cause harm, less oversight, and engagement with national governments (

Appe and Schnable 2019;

Kinsbergen 2019;

Schulpen and Kinsbergen 2012). However, citizen aid of this sort is not new nor do these organizations always remain small. One notable example of a small, volunteer-run INGO rooted in a value-based position in opposition to other INGOs is Medecins sans Frontiers (Doctors without Borders). When it was founded in 1971, this organization characterized a grassroots INGO, but over the last five decades has grown to become one of the largest INGOs in operation. With regard to funding and modality, Medecins sans Frontiers counters the trend of scaled, large INGOs in that it continues to rely almost exclusively on private donations and volunteers (in many cases refuses to accept government money on principle). It is not the case, therefore, that citizen aid remains small in size, nor that it does not grow and seek to overcome the challenges previously outlined. Understanding how organizations make that transition largely draws upon case studies, which is a gap in the literature we explore in this paper.

Despite an abundance of literature and policy analysis on development INGOs, scholars have only recently turned their attention to the growing importance of privately-funded citizen aid organizations. Indeed, the 1980s and 1990s were known as the ‘age of INGOs’ (

Bratton 1989) that brought about substantial increases in the number, scale, and public funding directed towards them. Subsequently, scholars produced detailed accounts of these ‘professionalized INGOs’ to characterize their features, roles, lifecycles, and relations to aid delivered through state agencies. Yet, with the significant growth in citizen aid during the 2000s, scholarly attention has lagged behind in offering descriptive information of these new actors in the development sector. The few available studies on citizen aid are based on qualitative analyzes using small sample sizes, which limits generalizability. This is understandable given the challenges involved in collecting quantitative data on a disparate collection of small-scale and privately-funded INGOs. Indeed, there is a shortage of rich empirical research on the structure, size, and operations of citizen aid, which has been a pressing knowledge gap to understand their place in international aid efforts (

Clifford 2016;

Kinsbergen et al. 2017). With the rapid expansion of citizen aid initiatives, there is a need for large-scale empirical data to understand how they fit within the INGO sector, which stands to inform the development community on the role and positioning of this disparate collection of development enthusiasts within the broader aid architecture.

As of 2018, there were 84,078 registered charities in Canada. Of these, 1371 Canadian charities had an international focus, based on their reporting of foreign expenditures in 2015. This means that approximately 1.6% of registered Canadian charities have an international focus, while the overwhelming majority (98.4%) are domestically oriented. This paper focuses on this small segment of INGOs that have an international focus. Of the 1371 Canadian INGOs, there are significant data limitation challenges. For example, available data from the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) makes available organizational reports on an annual basis but next to no option exists for accessing or assessing the data at an aggregate level. This poses several challenges for research. We are aware that many organizations have been founded and closed in decades past, however unless one searches for them specifically, they do not appear in recent annual listings, as they are no longer active. As a result, our database does not accurately reflect the INGO sector since its founding, only those organizations that have remained active. An example of this challenge is when we look at the average year of founding. As an example of this limitation, in the aggregate the average year of founding for all active INGOs that are registered charities in the CRA database as of 2015 is 2001. This figure, however, only reflects active organizations and does not reflect all the INGOs that have ceased operations. This average founding year would likely be much earlier, had we been able to take into account all the organizations that have closed. While important, our study focuses on INGOs that scale, not on those that have closed, making the impact of this limitation less significant. Additional limitations are outlined in the methods section. With limitations taken into account, there are some general descriptive characteristics we find about the Canadian INGO sector.

Of the registered charities with an international focus, 36.5% report being a religious organization, half of which are registered as a Christian organization with 18% registered as a more generic ‘Religious’ organization. Based upon population data for 2016 from Statistics Canada, the frequency of registration per province is generally in line with population distribution, although British Columbia and Quebec are underrepresented, and Ontario is overrepresented. Only a small minority of INGOs received funding from the federal government (discussed in more detail below). The average number of full-time employees was 6, however this ranged from 1159 employees to none. The average number of countries the INGOs worked in was 3, which ranged from 67 to 1. Notable amongst that range was that only 16.4% worked in 5 or more countries, meaning that the vast majority of Canadian INGOs with an international focus were much more concentrated geographically. In fact, a full 60% of Canadian INGOs worked in a single country. Of the INGOs working in only one country, the most common countries were (in order): India, Haiti, Kenya and Uganda. Based on CRA categories, the areas of work are extremely broad, yet education, health, population, and social services are predominate activities (more than 50% of INGOs report doing so), while water and sanitation, government and civil society, transportation, communications, energy, banking, business, agriculture, environment, food, industry, trade, and tourism are sectors engaged in far less frequently, or not at all. Older organizations appear to have an advantage in securing federal funding (of the 20 INGOs with the largest revenue streams in Canada, the average founding year is 1977, with only three being founded during the recent two decades; the overall average founding year is 2001). However, many organizations that were founded in the 1960s have small budgets, or have since closed (in other words, time alone does not result in greater funding).

This article critically analyzes the Canadian INGO landscape and presents findings regarding the development and expansion of INGOs. In so doing, we shine a light on segments of the INGO sector that receive less academic attention: the small and medium transitioning INGOs, potentially on the pathway to join the ranks of the largest, which attract significantly larger budgets and government funding. This is important because the vast majority of INGOs in Canada are relatively small and operate with little or no funding from the Government of Canada. Comparative research from other countries will be needed to assess if our findings are specific to Canada or if they reflect trends in other countries as well. This article contributes to an emerging literature analyzing Canadian INGOs and makes specific contributions by focusing upon those smaller and medium size organizations that receive no federal funding. In the following section, we offer a detailed presentation of the database that was created for this analysis as well as the methods utilized to analyze it. The findings are separated into subsections that describe the distinctive characteristics of INGOs that receive significant government funding, minor government funding, and no government funding. We follow that up with an exploration of the potential existing of a ‘pathway’ for the smaller and medium sized organizations that may be in transition to becoming larger INGOs that can attract government funding. The paper concludes with some implications of the findings as well as potential directions for future research.

3. Methods

An inventory of all Canadian INGOs was constructed by analyzing the Canada Revenue Agency’s (CRA) T3010 Registered Charity Information Return filings coupled with INGO organizational websites. As of 2018, the CRA’s database of all charity listings totaled 84,078 charities. With no explicit category designating ‘international development’, the following five-step procedure was used to construct an inventory of Canadian INGOs. First, following

Tomlinson’s (

2016) rationale, we isolated all charities with at least CAD

$1 in foreign expenditures in 2015 (the most recent year with accessible data), which signaled that a charity might be involved in international development, and produced a total of 5203 charities. Second, the ‘programs and activities’ section of the T3010 form was manually reviewed to discern if these charities engaged in international development activities. We operationally defined ‘international development activities’ to include at least one of the following foci: education, food security/nutrition, water/hygiene/sanitation, health care, childcare, economic development, environmental protection, human rights protection, strengthening governance, gender equality, refugee support, or war/disaster relief. This refined our inventory of potential international development charities to 1669 (charities that were excluded from the dataset were principally religious groups with no explicit description of development work overseas, international cultural and arts organizations, and research-based institutions.). Third, we eliminated charities that did not operate in at least one ODA-eligible country. ‘ODA-eligible countries’ were operationally defined as those found on the OECD DAC list of ODA recipients between 2011 and 2015 (

OECD 2018). This was done by analyzing the T3010 forms ‘operation outside of Canada’ section as well as the organizational websites of each charity (when available) to determine which countries they operate in. Fourth, we excluded charities that participate in international development as a peripheral activity for their organization. Charities with a primary focus on international development were operationally defined as having foreign expenditures account for at least 40% of total expenses. While this represents an arbitrary cut-off point, upon review of charities in the database, those with less than 40% foreign expenditures tended to implement diverse activities in Canada while international development projects were typically a secondary priority. Using the T3010 data, a five-year average (2011–2015) of total expenditures (line 5100) and total expenditures outside of Canada (line 200) was collected. A five-year average was collected to smooth data over several years to reduce noise due to annual aid flow volatility (

Michaelowa and Weber 2007;

Neumayer 2002;

Nunnenkamp et al. 2009). For organizations younger than five years, the total number of active years was averaged together. Taken together, this produced a list of 1371 Canadian INGOs with a focus on development and/or humanitarian activity.

For this paper, we categorized INGOs into three types: (1) organizations that receive significant federal government funding, (2) organizations that receive minor government supports, such as funding for summer interns, and (3) organizations without any government funding. Initially, we envisioned a two-part categorization of organizations (i.e., with and without federal government funding), yet when we analyzed the financial data it became clear that many organizations reported some government funding that was not project funding. For example, there were 10 organizations that reported an average of less than

$100 federal government funding over the period of study. This made us reflect on a two-part categorization and forced us to analyze what was indicative of federal project funding that would be supportive of programming and differentiate that from other forms of reported federal funding that appeared too small to be a federal grant for project support. In our experiences with donor agencies, federal funding in support of projects is rarely this small due to the grant administration costs involved in federal government granting processes. In order to better understand what forms of funding organizations were reporting as ‘federal funding’ in such small sums, we sought input from lawyers who work with charitable organizations in Canada. As we had also assumed, it was agreed that these small sums of funding were not in support of projects (e.g., funding from Global Affairs Canada in support of international projects). Four potential explanations for the small sums of reported federal funding were proposed: (1) Harmonized sales tax (HST)

1 rebates that were incorrectly filed as federal funding, (2) youth summer jobs program,

2 which subsidizes summer employment, (3) holdbacks or final payments after the submission of a final report from a grant outside of the years of study, and (4) partial funding based on partial completion of work with federal funding. The first two appeared to provide the strongest explanations for most INGOs in this group, however federal funding reports do not specify the type and therefore it is only our informed speculation.

The first category of organizations comprised those that received significant federal funding for programming, averaged over the study period, which we set as reporting federal funding greater than CAN

$25,000. This is the threshold that is used by the Government of Canada and the Treasury Board regarding grants and contributions (

GoC 2018). Of the 1371 organizations, 112 (8%) fell into this category. The second category, organizations reporting small sums of federal funding (less than CAN

$25,000 averaged over the study period) amounted to 67 (5%) organizations. The third category were registered charitable organizations with no reported federal funding in any of the years studied, which was by far the largest category, totaling 1192 (87%) of the organizations in the data set. However, a significant percentage of these organizations are defined as ‘effectively non-functional’ since they had little to no foreign expenditures (CAN

$20,000 or less). For the analysis of the third category, these ‘effectively non-functional’ organizations were removed to prevent distorting the data. Additional details on these organizations are outlined in the findings below. We adopted a minimum international funding threshold as a means to differentiate organizations that are ‘effectively operational’ and those that are registered and reporting, but not actively engaging in activities (‘non-functional’). We defined this as CAN

$20,000 in foreign expenditures. While this figure is an arbitrary cut-off marker, it has been used elsewhere as an indication of a minimum threshold of financial support to impact communities in recipient countries and, thus, our adoption follows the approach typically used for studies of this nature (

Davis 2019b;

Tafa 2018;

Tomlinson 2016).

One of the limitations of this study is that we have analyzed data from registered charities in Canada. A key part of our study aimed to highlight the large number of smaller organizations with little or no government funding. However, in the Canadian non-profit sector, an INGO can operate without being a registered charity. In these cases, incorporation may be granted at the provincial or federal level, allowing the organization to operate, but it is not able to issue official donation receipts that are used when filing taxes. Donations made to these organizations are not reported to the Government of Canada, and as a result do not appear in our data. We anticipate that there are more small, non-profit INGOs that have incorporated in this way than those that have become registered charities because of the requirements related to becoming a registered charity and maintaining that status. However, we only have data from registered charities as these INGOs are required to report financial data to the government annually, while the incorporated non-profit INGOs that are not registered charities do not. As far as we know, no systematic studies have been conducted on INGOs that are incorporated but are not registered charities, which is an area that could be a focus for future study. Another limitation of this study is that we analyze registered charities during a specific period of time. This affects the averaging process, as some organizations may obtain large grants in specific years. As this study analyzes the sector in aggregate, this limitation aligns with the objectives in that any selection of inclusion years would be subject to this limitation. However, as noted above, the dataset does not include data on registered charities that have closed. For example, we have analyzed the categories in a range of ways (e.g., year of registration), however, if INGOs had closed before the inclusion years or re-registered afterward, they would not appear in the data. This does not affect all analyses (e.g., total government funding during the years of study), yet it does present a blind spot about understanding the sector.

4. Results

In this section, we analyze the comparative traits of organizations that receive significant federal government funding, organizations that receive minor government supports (i.e., funding for summer interns), and, lastly, organizations without any government funding. In terms of the overall funding for Canadian INGOs, those receiving significant government funding are the largest and hold a large share of the funding (47% of all annual revenue of INGOs; CAN

$1.6 billion), despite being relatively few in number. Nonetheless, the fact that the organizations without any government funding had an aggregate annual revenue of CAN

$378 million (11%) demonstrates their significance. This also attests to the potential of the INGOs in transition as a category of INGOs that are moving from small- to large-scale, about which we draw insight from regarding pathways of scaling. As the categories are analyzed, we explore a series of questions that might explain the potential pathways for scaling-up (i.e., time of operation, number of full-time employees, country coverage, overhead expenditures, and religion; see

Table 1).

4.1. INGOs with Significant Federal Government Funding

Of the 1371 Canadian INGOs with an international focus, 112 had annual federal government revenue greater than CAN

$ 25,000 (averaged over a five-year period). Half of the organizations (61 of 112 (55%)) were based in one province, Ontario. The majority of these organizations were secular (79 of 112; 71%). Of the 33 organizations that reported a faith-based orientation, 30 (91%) were Christian and 3 were other faiths. While these 112 organizations only accounted for 8% of INGOs in the dataset, they accounted for 47% of the total revenue (CAN

$ 1.6 billion annually). On average, these organizations each received CAN

$ 2.9 million annually from the federal government, although this ranged from CAN

$ 26,437 to CAN

$ 30.9 million. As shown in

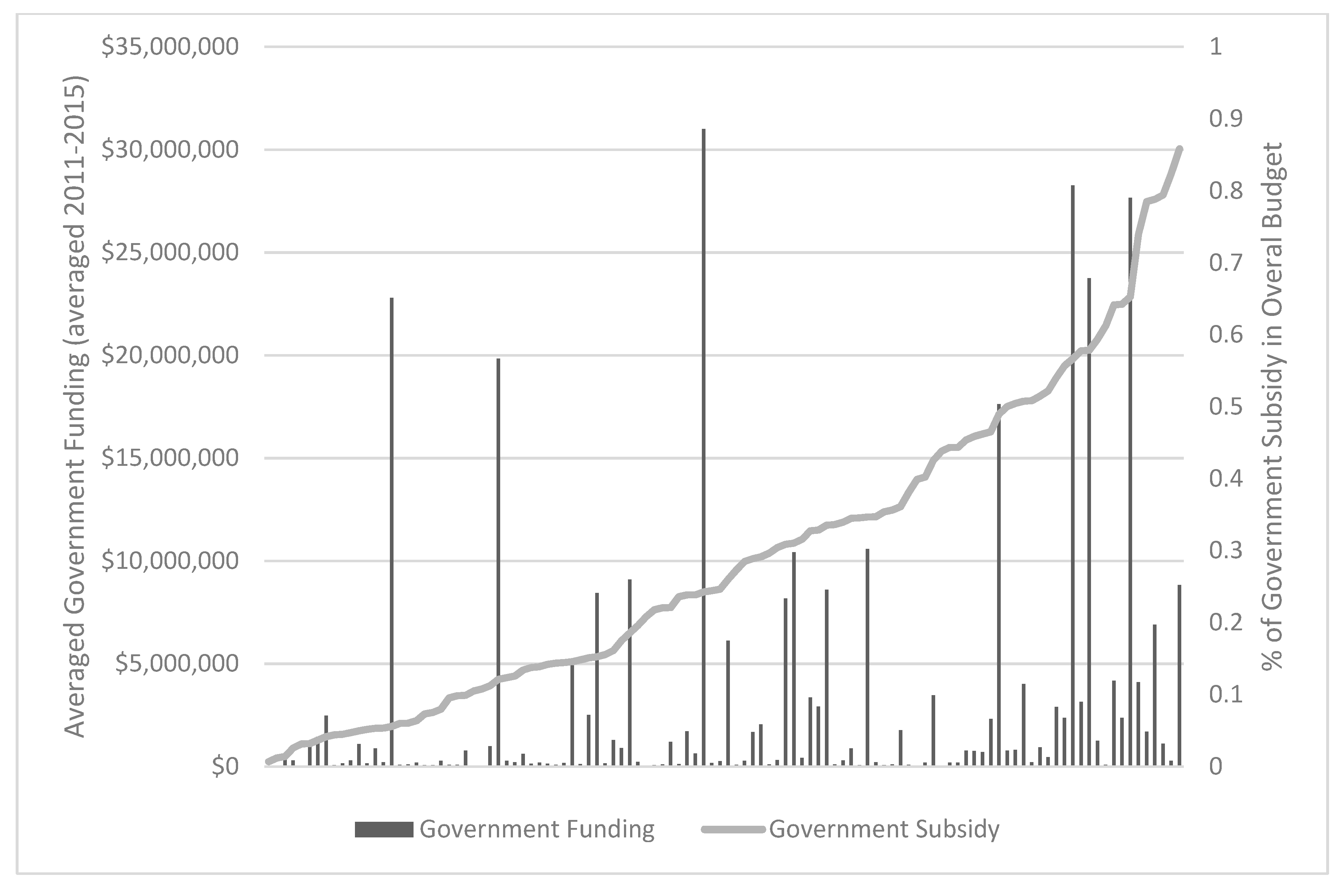

Figure 1, the majority (57 of 112; 51%) of these organizations received less than an annual average of CAN

$500,000, while a minority (9 of 112; 8%) received greater than CAN

$10 million as an annual average. The INGOs receiving the largest sums from the Government of Canada were (in order of largest first): Care Canada, Save the Children Canada, Canadian Foodgrains Band, Oxfam Quebec, World Vision Canada, Plan International Canada, Centre D’Etude et de Cooperation Internationale, Cuso International, and Organisation Catholique Canadienne pour le Development et la Paix). Examining the organizations that receive the highest government funding raises a question if high levels of federal government funding are related to organization size and scale. If we compare the amount of federal government funding to the percentage of government subsidy in the overall NGO budget, the correlation is weak (r = 0.219). Additionally, if we assess the federal government subsidy to the total revenue, the correlation is weak and slightly negative (r = −0.134). While this does not tell us about the origin of size and scale, it indicates that the largest INGOs are not sustained by federal government support.

In addition to correlations, if we analyze the organizations that receive significant funding from the Federal Government of Canada, in the aggregate, they are not reliant upon this as their primary source of funding. On average, Canadian government funding accounts for 29% of the aggregate revenue of these 112 INGOs. A similar sum (29%) of funding for these 112 organizations was obtained from foreign sources (as earlier noted: three INGOs account for 70% of foreign funding, which appears to be from other donors providing funding to Canadian INGOs to act as implementing organizations for their programming, however foreign funding sources is an area that requires more research). This presents two critical reflections for the literature. First, while much of the INGO literature has been concerned about government influence on INGOs (

Barry-Shaw and Jay 2012;

Edwards and Hulme 1996;

Keck 2015), perhaps there should be a greater concern for foreign interests influencing INGOs. Second, in the averaged aggregate, Canadian INGOs that obtained significant government funding were primarily funded by private donors (42% of aggregated average). However, on an organization-by-organization basis, some organizations are much more dependent upon the government. In total, 10 organizations obtained 60% or more of their budget during the study years from the government.

3 These organizations appear to be outliers in that they received large government grants but were either otherwise relatively small or a Canadian country office of a larger international NGO that leveraged its international network to obtain a large grant. It is only for this subset that the federal government plays a primary role in sustaining their scale of operations.

4.2. INGOs with Minor Federal Government Support—Organizations in Transition?

There were 67 organizations with government funding between CAN$1 and CAN$24,999 (5% of all organizations). These organizations were also most likely to be based in Ontario, with 28 of 67 (42%) based there. This category of organization was more religious than those receiving significant government support, with 32 of 67 (48%) professing a Christian mandate (no other faith-based organizations were represented). While these 67 INGOs had little Canadian government funding (average under CAN$5000), they received relatively more foreign funding (average CAN$108,475; a lower overall percentage than INGOs with significant government funding). However, foreign funding was concentrated amongst a subset of these organizations, as 34 of the 67 (51%) reported CAN$0 foreign funding. One organization (World Federation of Hemophilia) reported an average annual foreign income greater than CAN$5 million, distorting the overall average. When that organization is removed from this group, the average foreign revenue is CAN$26,892, which is on a scale relative to the government funding, as per the general trend.

We separated this group of INGOs as we felt it might provide insight into the transition from a relatively small, voluntary organization along the pathway to scale into a larger one. As organizations expand, we assumed they might seek smaller forms of governmental support, such as obtaining funding for student internships or acquiring smaller grants, which might later be used to justify their ability to manage larger grants. We had assumed this group might access entry-level forms of government support as their organization grows. However, there was a much greater range of total revenue in this category than anticipated. For example, despite having little government support, 25 INGOs in this category (37%) had total revenue greater than CAN$500,000, and four INGOs had total revenue greater than CAN$5 million. All of these organizations tended to spend a similar amount on management/administration, fundraising, and gifts when compared to the category of INGOs getting significant government funding; 15% of revenue for the second category of INGOs versus 16.6% for the first. This might indicate that additional funding is required to scale certain aspects of the INGO in order to obtain government funding, regardless of government support.

There is a strong correlation (r = 0.56) between total revenue with management and administrative expenditures. Spending more on management when there is more money is expected. A finding that was unexpected, however, was that the correlation between total revenue and number of countries operated in was only moderately correlated (r = 0.346). One of the potential pathways for INGO scaling proposed in the literature is expanding country coverage (

Cooley and Ron 2002), although this category, which we thought might show INGOs in transition, does not indicate that INGOs are generally broadening country coverage as a strategy for scaling. Looking at this question from a different perspective, we do see a correlation (r = 0.544) between federal government funding and total recipient countries, which is a stronger correlation than total revenue with total recipient countries (r = 0.346). In other words, organizations receiving federal government funding are more likely to have a greater country coverage than those not receiving federal government funding.

Analyzing the set of INGOs with little government support also raised another question about the pathway of scaling: time in operation. INGOs with minor government support had an average registration year of 1996, whereas those with significant government funding had an average registration year of 1985. Furthermore, the group of INGOs with no government support had an average registration date of 2002. As earlier noted, our ability to analyze date of registration is complicated by the fact that we only have data for active organizations; meaning the organizations that had closed at any point before the study years are excluded entirely. When we analyze total revenue with years of operation, there is a strong correlation (r = 0.663). However, this was not the case for federal government funding, which had a weak correlation (r = 0.258) with years of operation. In other words, it appears that one of the strongest factors of scale is years of operation (acknowledging the bias of excluding those that had closed) but this did not necessarily equate with obtaining government support. One potential explanation of this might be that religious organizations may not seek government funding, even if they grow, to stay true to their own mandate. However, there was no correlation between religious organizations and federal government funding (r = −0.011).

4.3. INGOs with No Federal Government Support

From an aggregate assessment of these three categories, it appears that organizations with no government support have a larger total revenue than the organizations with significant government support. This third category included 1192 organizations, which collectively had an average annual total revenue of CAN$1.7 billion (greater than the 112 INGOs with significant government support, having CAN$1.6 billion). However, one organization—the MasterCard Foundation—disproportionately accounts for the revenue in this category. In fact, the MasterCard Foundation has the largest total revenue of any registered charity in Canada (average annual revenue CAN$1.3 billion), which is more than triple the total revenue of the second largest, World Vision Canada (having an average annual revenue of CAN$408 million). In order to more accurately represent and analyze this category of INGOs, we removed the MasterCard Foundation from the analyses that follow, despite it not receiving any government funding during the study period. We also found a large number of organizations that had little to no foreign expenditures (CAN$20,000 or less), which we have classified as ‘effectively non-functional’ (see methods above), which were also removed from this category. There were 267 effectively non-functional registered charities, with average foreign expenditures less than CAN$20,000. After having made these adjustments to the category, the third group of INGOs, with no government funding, still remained the largest, having 924 INGOs.

Once these changes were made to the database, a clearer picture emerged of this large group of registered charities. As a group, these organizations were younger, with an average registration year of 2002 (compared to 1995 for category 2 and 1985 for category 1 INGOs). The organizations collectively held a total average revenue of CAN$378 million, with an average of CAN$409,910 each (ranging from CAN$21.9 million to CAN$1454). Despite comprising 67% of all the registered charities in Canada with an international focus, the collective total revenue held by these INGOs was only 11% of the total. As shown by these three categories, INGOs with significant government support (plus the MasterCard Foundation) are the largest organizations from a financial perspective. The 924 organizations in category three, despite being numerous, play a relatively small role in implementing the charitable giving for international purposes. Like the INGOs in the other two categories, INGOs in this group were also more likely to be based in Ontario (42%; the same percentage as category 2, while 55% of category 1 organizations were based there). These organizations were more likely to be secular than category 2 organizations (58% compared to 52%) but less likely to be secular than category 1 INGOs (58% compared to 71%). Compared to the other two categories, INGOs with no government funding were less likely to attract foreign funding (as a percentage of total revenue), with an average annual foreign funding of CAN$14,923. This average, however, is affected by a few organizations that received large flows of foreign funding (56% was obtained by only 5 organizations).

Analyzing the group of INGOs with no government funding raises a couple of questions, one from the literature and one from our data. First, do these organizations scale more slowly because they do not have or commit the resources that would enable them to do so? The average expenses made in management/administration, fundraising and gifts were lower than the other two categories, at 11% (as reported to CRA, in our dataset). This affirms some of the available literature or assumptions about smaller INGOs, in that their operational costs are lower and a higher percentage is spent on activities (

Appe and Telch 2019;

Appe and Schnable 2019;

Davis forthcoming;

Fylkesnes 2019). Indeed, the most common way small-scale INGOs distinguish themselves from other aid actors is their superior financial efficiency as they have few or no paid staff, no or low administration costs, and no or low office costs. This translates to low overheads and, thus, a higher percentage of donations allocated directly to development projects. Another rationale for maintaining a volunteer-based organization and low overheads is that it offers a means to stand in solidarity with community-based volunteer organizations in the global South (

Davis forthcoming). Second, do these organizations have fewer paid employees who might bring expertise and experience from the sector to better know how to obtain funding, including government grants. When we analyze the data of full-time employment, this appears (at first) to be the case. INGOs in category 3 have an average of 1.3 full time employees (range: 0 to 77), compared to 5.3 for category 2 (range: 0 to 12) and 41.7 for category 1 (range: 0 to 1159). These are paid employees of the Canadian organization, however there are some limitations in this data, such as their location not being reported (charities do report on part-time employees, however given the lack of data about these roles, such as the amount of hours and duration, we have not presented them). Given the average total revenue differences (category 1: CAN

$14.3 million; category 2: CAN

$1.8 million; category 3: CAN

$409,910), however, the ratio of overall funding to full time employees is not much different (per full time employee: category 1 CAN

$343,737; category 2 CAN

$345,718; category 3 CAN

$315,315). While overall administrative costs are lower, this does not result in significantly less emphasis on hiring full time staff. Additionally, as the literature has also belabored, lower operational costs do not equate with more effective, efficient, appropriate or suitable activities (

Gregory and Howard 2009). Assessing those factors is beyond the scope of this work.

4.4. Which INGOs Transition? Outlier Sampling

To further understand the potential scaling pathways, we examined some of the outliers in the data. We adopted this purposive sampling approach as not all organizations will become large and these outliers may show how the scaling transition takes place. For example, consider the outlier organization that has a much greater number of full-time employees (average 596) than would be expected given the total revenue (average CAN

$33.8 million): Right to Play International. Alternatively, consider an organization with a large total revenue (average CAN

$59.4 million) but relatively few full-time employees (i.e., 71): Samaritan’s Purse. Taking advantage of the time that has passed since the study period years (2011–2015), we can assess where these organizations were as of 2018 (which is the most recent tax year made available by Canada Revenue Agency as of Feb., 2020). As of 2018, Right to Play International had grown its total revenue to CAN

$46.3 million, while reducing its full-time staff to 428. Samaritan’s Purse total revenue declined to CAN

$53.0 million, while increasing its number of full-time employees to 85. Notably, both Right to Play International and Samaritan’s Purse employed 10 people (in 2018) who were paid more than CAN

$120,000. While far from conclusive, these qualitative insights from outliers suggest that investing in staffing may play an enabling role in the scaling of INGOs. This is counter-intuitive for private donors, who have often been directed to focus their giving on organizations with low administrative costs, particularly low in relation to other INGOs (

Cochrane and Thornton 2016). Initiatives that have focused attention on administrative percentages of overall budgets and high compensation packages such as Charity Watch and Charity Navigator, while justified in bringing this to light, may also have unintended consequences. A potential example of an unintended consequence is disincentivizing organizations from investing in highly skilled employees, who might enable organizations to grow in size and scale, as that would negatively impact donor perceptions of the organization. As has been noted in this paper, private donors are the largest contributor to Canadian INGOs with an international focus and thus the potential role that these metrics have could be significant, although additional research is required to assess the extent to which organizations are altering their hiring practices as a result of such initiatives. Following the limitations of the assessments that focus upon administrative costs, new criteria, such as effectiveness and impact, have emerged as ways to assess the charitable sector (GiveWell is an example of this). Our findings suggest that this shift offers valuable new perspectives, yet we are also cognizant of the limitations (and unintended consequences) of these new metrics, such as by offering simplistic, technocratic measures that often neglect questions of human rights, justice, and equity (

Cochrane and Thornton 2016).