Giving Guys Get the Girls: Men Appear More Desirable to the Opposite Sex When Displaying Costly Donations to the Homeless

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Showing Off Altruism to the Opposite Sex

1.2. Is Altruism a Signal That Is Attractive to the Opposite Sex?

1.3. Is Altruism an Honest Mate Signal?

1.4. What Mate Quality Is Altruism Signalling?

1.5. Giving to the Homeless as an Altruistic Mate Signal

2. Results

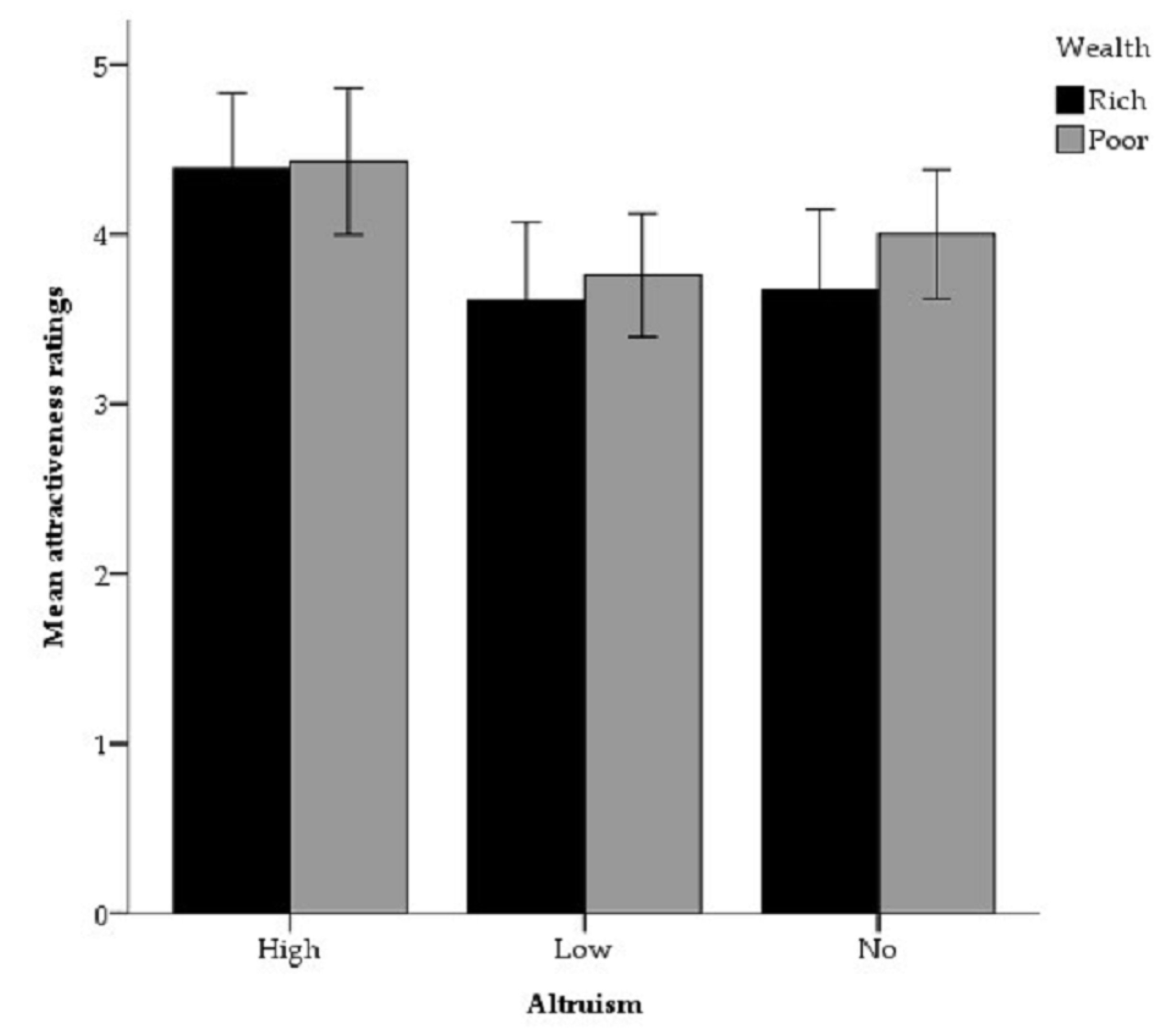

2.1. Hypotheses One and Two: Costly Displays of Altruism Are More Attractive Regardless of Wealth

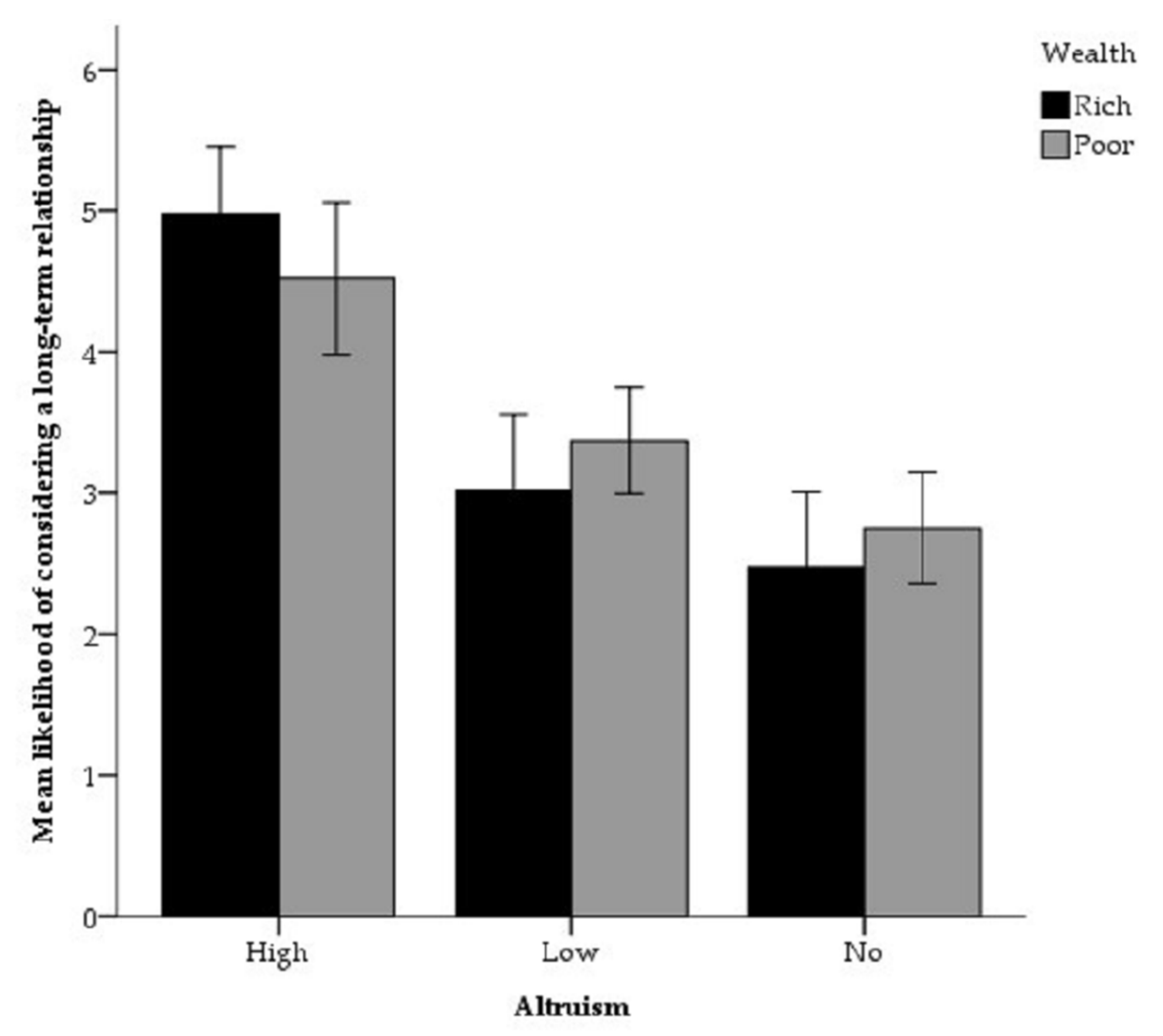

2.2. Hypothesis Three: Altruism Is a Signal of Long-Term but Not Short-Term Mate Quality

2.3. Hypothesis Four: Displays of Altruism Are Associated With Good Parenting Skills

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Participants

4.2. Design

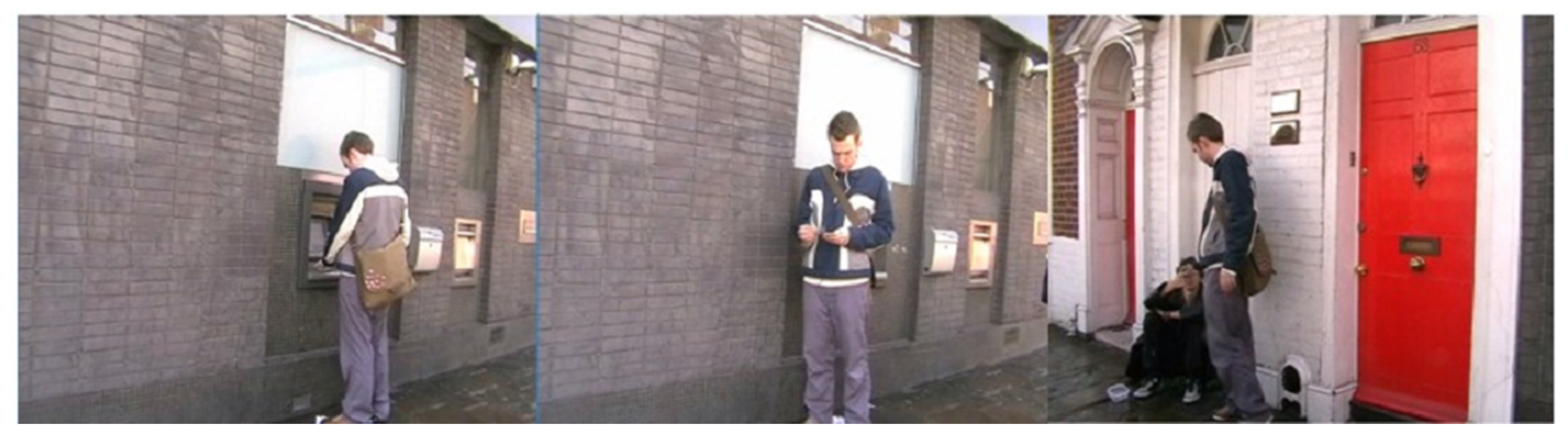

4.3. Materials, Procedureand Ethics

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Ethics

References

- Alexander, Richard D. 1987. The Biology of Moral Systems. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ambady, Nalini, and Robert Rosenthal. 1993. Half a minute: Predicting teacher evaluations from thin slices of nonverbal behavior and physical attractiveness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 64: 431–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambady, Nalini, Mark Hallahan, and Brett Conner. 1999. Accuracy of judgments of sexual orientation from thin slices of behaviour. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology 77: 538–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolou, Menelaos. 2007. Sexual selection under parental choice: The role of parents in the evolution of human mating. Evolution and Human Behavior 28: 403–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aries, Elizabeth J., and Fern L. Johnson. 1983. Close friendship in adulthood: Conversational content between same-sex friends. Sex Roles 9: 1183–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnocky, Steven, Tina Piché, Graham Albert, Danielle Ouellette, and Pat Barclay. 2017. Altruism predicts mating success in humans. British Journal of Psychology 108: 416–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barclay, Pat. 2010. Altruism as a courtship display: Some effects of third-party generosity on audience perceptions. British Journal of Psychology 101: 123–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barclay, Pat, and Rob Willer. 2007. Partner choice creates competitive altruism in humans. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London Series B 274: 749–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bateman, Angus J. 1948. Intra sexual selection in Drosophila. Heredity 2: 349–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhogal, Manpal S., Niall Galbraith, and Ken Manktelow. 2016. Sexual selection and the evolution of altruism: Males are more altruistic and cooperative towards attractive females. Letters on Evolutionary Behavioral Science 7: 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bhogal, Manpall S., Niall Galbraith, and Ken Manktelow. 2019. A research note on the influence of relationship length and sex on preferences for altruistic and cooperative mates. Psychological Reports 122: 550–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhogal, Manpal S., Daniel Farrelly, Niall Galbraith, Ken Manktelow, and Hannah Bradley. 2020. The role of altruistic costs in human mate choice. Personality and Individual Differences 160: 109939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bliege Bird, Rebecca, Eric Smith, and Douglas W. Bird. 2001. The hunting handicap: Costly signalling in human foraging strategies. Behavioural Ecology and Sociobiology 50: 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brase, Gary L. 2006. Cues of parental investment as a factor in attractiveness. Evolution and Human Behavior 27: 145–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Mitch, and Donald F. Sacco. 2019. Is pulling the lever sexy? Deontology as a downstream cue to long term mate quality. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 36: 957–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buss, David M. 1989. Sex differences in human mate preference: Evolutionary hypotheses tested in 37 cultures. Behavioural and Brain Sciences 12: 1–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buss, David M. 2004. Evolutionary Psychology. The New Science of the Mind. Boston: Allyn & Bacon. [Google Scholar]

- Buss, David M., and David P. Schmitt. 1993. Sexual strategies theory: An evolutionary perspective on human mating. Psychological Review 100: 204–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catania, Joseph A., Diane Binson, Jesse Canchola, Lance M. Pollack, Walter Hauck, and Thomas J. Coates. 1996. Effects of interviewer gender, interviewer choice, and item wording on responses to questions concerning sexual behavior. Public Opinion Quarterly 60: 345–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, Christopher H., Charles Ofria, and Ian Dworkin. 2013. Runaway sexual selection leads to good genes. Evolution: International Journal of Organic Evolution 67: 110–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charities Aid Foundation. 2019. CAF UK Giving 2019: An Overview of Charitable Giving in the UK. Available online: https://www.cafonline.org/docs/default-source/about-us-publications/caf-uk-giving-2019-report-an-overview-of-charitable-giving-in-the-uk.pdf?sfvrsn=c4a29a40_4 (accessed on 9 June 2020).

- Eagly, Alice H., and Maureen Crowley. 1986. Gender and helping behaviour: A meta-analytic review of the social psychological literature. Psychological Bulletin 100: 283–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehlebracht, Daniel, Olga Stavrova, Detlef Fetchenhauer, and Daniel Farrelly. 2018. The synergistic effect of prosociality and physical attractiveness on mate desirability. British Journal of Psychology 109: 517–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrelly, Daniel. 2011. Cooperation as a signal of genetic or phenotypic quality in female mate choice? Evidence from preferences across the menstrual cycle. British Journal of Psychology 102: 406–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrelly, Daniel. 2013. Altruism as an indicator of good parenting quality in long term relationships: Further investigations using the Mate Preferences towards Altruistic Traits scale. The Journal of Social Psychology 153: 395–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrelly, Daniel, and Laura King. 2019. Mutual mate choice drives the desirability of altruism in relationships. Current Psychology 38: 977–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrelly, Daniel, John Lazarus, and Gilbert Roberts. 2007. Altruists attract. Evolutionary Psychology 5: 313–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrelly, Daniel, Paul Clemson, and Melissa Guthrie. 2016. Are women’s mate preferences for altruism also influenced by physical attractiveness? Evolutionary Psychology 14: 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, Franz, Edgar Erdfelder, Albert-Georg Lang, and Axel Buchner. 2007. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods 39: 175–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldberg, Tony L. 1995. Altruism towards panhandlers: Who gives? Human Nature 6: 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grafen, Alan. 1990. Biological signals as handicaps. Journal of Theoretical Biology 144: 517–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, Peter B., Shelly L. Volsche, Justin R. Garcia, and Helen E. Fisher. 2015. The roles of pet dogs and cats in human courtship and dating. Anthrozoös 28: 673–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guéguen, Nicolas. 2014. Cues of men’s parental investment and attractiveness for women: A field experiment. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment 24: 296–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, William D. 1964. The genetic evolution of social behaviour I and II. Journal of Theoretical Biology 7: 1–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkes, Kristen. 1993. Why hunter-gatherers work—An ancient version of the problem of public goods. Current Anthropology 34: 341–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkes, Kristen, and Rebecca Bliege Bird. 2002. Showing off, handicap signalling, and the evolution of men’s work. Evolutionary Anthropology 11: 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, Judith A., Philip Blumstein, and Pepper Schwartz. 1987. Social or evolutionary theories? Some observations on preferences in human mate selection. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 53: 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iredale, Wendy, Mark Van Vugt, and Robin Dunbar. 2008. Showing off in humans: Male generosity as a mating signal. Evolutionary Psychology 6: 386–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen-Campbell, Lauri A., William G. Graziano, and Stephen G. West. 1995. Dominance, prosocial orientation, and female preferences: Do nice guys really finish last? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 68: 427–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Richard C. 1996. Attitudes of Carnegie medallists performing acts of heroism and of the recipients of these acts. Ethology and Sociobiology 17: 355–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, Susan, and Robin I. M. Dunbar. 2001. Who dares wins: Heroism versus altruism in women’s mate choice. Human Nature 12: 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kniffin, Kevin M., and David S. Wilson. 2004. The effect of nonphysical traits on the perception of physical attractiveness: Three naturalistic studies. Evolution and Human Behaviour 25: 88–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokko, Hanna. 1998. Good genes, old age and life-history trade-offs. Evolutionary Ecology 12: 739–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruger, Daniel J., Maryanne Fisher, and Ian Jobling. 2003. Proper and dark heroes as dads and cads: Alternative mating strategies in British Romantic literature. Human Nature 14: 305–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latané, Bibb. 1970. Field studies of altruistic compliance. Representative Research in Social Psychology 1: 49–61. [Google Scholar]

- Long, Melanie Li-Wen, and Anne Campbell. 2015. Female mate choice: A comparison between accept-the-best and reject-the-worst strategies in sequential decision making. Evolutionary Psychology 13: 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyle, Henry F., III, Eric Smith, and Roger J. Sullivan. 2009. Blood donations as costly signals of donor quality. Journal of Evolutionary Psychology 7: 263–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margana, Lacey, Manpal S. Bhogal, James E. Bartlett, and Daniel Farrelly. 2019. The roles of altruism, heroism, and physical attractiveness in female mate choice. Personality and Individual Differences 137: 126–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maynard Smith, John. 1964. Group selection and kin selection. Nature 201: 1145–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Jean B. 1976. Toward a New Psychology of Women. Boston: Beacon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Geoffrey. 2001. The Mating Mind. London: Vintage. [Google Scholar]

- Millet, Kobe, and Siegfried Dewitte. 2007. Altruistic behavior as a costly signal of general intelligence. Journal of Research in Personality 41: 316–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, Fhionna R., Clare Cassidy, Miriam J. L. Smith, and David I. Perrett. 2006. The effects of female control of resources on sex-differentiated mate preferences. Evolution and Human Behavior 27: 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, Erin, Samanta Warta, and Kristen Erichsen. 2014. College students’ volunteering: Factors related to current volunteering, volunteer settings, and motives for volunteering. College Student Journal 48: 386–96. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, Edward R., Lia Gralewski, Neill Campbell, and Ian S. Penton-Voak. 2007. Facial movement varies by sex and is related to attractiveness. Evolution and Human Behaviour 28: 186–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulcahy, Nick. 1999. Altruism Towards Beggars as a Human Mating Strategy. Master’s thesis, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Oda, Ryo, Akinori Shibata, Toko Kiyonari, Mia Takeda, and Akiko Matsumoto-Oda. 2013. Sexually dimorphic preference for altruism in the opposite sex according to recipient. British Journal of Psychology 104: 577–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oda, Ryo, Akari Okuda, Mia Takeda, and Kai Hiraishi. 2014. Provision or good genes? Menstrual cycle shifts in women’s preferences for short term and long-term mates’ altruistic behavior. Evolutionary Psychology 12: 888–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmer, Jack A., and Seth Tackett. 2018. An examination of the Dark Triad constructs with regard to prosocial behavior. Acta Psychopathologica 4: 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulhus, Delroy L. 1991. Measurement and control of response bias. In Measures of Personality and Social Psychological Attitudes. Edited by John. P. Robinson, Philip. R. Shaver and Lawrence Wrightsman. San Diego: Academic Press, pp. 17–59. [Google Scholar]

- Pawlowski, Boguslaw, and Robin I. M. Dunbar. 1999. Impact of market value on human mate choice decisions. Proceedings Royal Society London B 266: 281–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penton-Voak, Ian S., David I. Perrett, Duncan L. Castles, Takehito Kobayashi, D. Michael Burt, Laura K. Murray, and Renato Minamisawa. 1999. Menstrual cycle alters face preference. Nature 399: 741–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrie, Marion. 1994. Improved growth and survival of offspring of peacocks with more elaborate trains. Nature 317: 290–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, Tim, Chris Barnard, Eamonn Ferguson, and Tom Reader. 2008. Do humans prefer altruistic mates? Testing a link between sexual selection and altruism towards non-relatives. British Journal of Psychology 99: 555–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portmann, Adolf. 1990. A Zoologist Looks at Humankind. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Powell, Chantal, and Mark Van Vugt. 2003. Genuine giving or selfish sacrifice? The role of commitment and cost level upon willingness to sacrifice. European Journal of Social Psychology 33: 403–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raihani, Nichola J., and Sarah Smith. 2015. Competitive helping in online giving. Current Biology 25: 1183–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, Gilbert. 1998. Competitive altruism: From reciprocity to the handicap principle. Proceedings of the Royal Society Series B: Biological Sciences 265: 427–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, Gilbert. 2015. Human cooperation: The race to give. Current Biology 25: R425–R427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roney, James R., Katherine N. Hanson, Kristina M. Durante, and Dario Maestripieri. 2006. Reading men’s faces: Women’s mate attractiveness judgments track men’s testosterone and interest in infants. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 273: 2169–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rusch, Hannes, Joost M. Leunissen, and Mark Van Vugt. 2015. Historical and experimental evidence of sexual selection for war heroism. Evolution and Human Behavior 36: 367–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Searcy, William A., and Stephen Nowicki. 2005. The Evolution of Animal Communication: Reliability and Deception in Signalling Systems. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tessman, Irwin. 1995. Human altruism as a courtship display. Oikos 74: 157–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tognetti, Arnaud, Claire Berticat, Michel Raymond, and Charlotte Faurie. 2012. Sexual selection of human cooperative behaviour: An experimental study in rural Senegal. PLoS ONE 7: e44403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tognetti, Arnaud, Dimitri Dubois, Charlotte Faurie, and Marc Willinger. 2016. Men increase contributions to a public good when under sexual competition. Scientific Reports 6: 29819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivers, Robert L. 1971. The evolution of reciprocal altruism. Quarterly Review of Biology 46: 35–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivers, Robert L. 1972. Parental investment and sexual selection, 1871–1971. In Sexual Selection and the Descent of Man. Edited by Bernard G. Campbell. Chicago: Aldine, pp. 136–79. [Google Scholar]

- Van Vugt, Mark, and Wendy Iredale. 2013. Men behaving nicely: Public goods as peacock tails. British Journal of Psychology 104: 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Vugt, Mark, and Paul Van Lange. 2006. Psychological adaptations for prosocial behaviour: The altruism puzzle. In Evolution and Social Psychology. Edited by Mark Schaller, Douglas T. Kenrick and Jeffry A. Simpson. East Sussex: Psychology Press, pp. 237–61. [Google Scholar]

- Van Vugt, Mark, Gilbert Roberts, and Charlie Hardy. 2007. Competitive altruism: Development of reputation-based cooperation in groups. In Oxford Handbook of Evolutionary Psychology. Edited by Louise Barrett and Robin Dunbar. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 531–40. [Google Scholar]

- Zahavi, Amotz. 1975. Mate selection—A selection for a handicap. Journal of Theoretical Biolog 53: 205–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahavi, Amotz. 1977. The cost of honesty (further remarks on the handicap principle. Journal of Theoretical Biology 67: 603–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahavi, Amotz. 1995. Altruism as a handicap—The limitations of kin selection and reciprocity. Journal of Avian Biology 26: 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Factor 1 | Factor 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Parental Qualities | Rich and Powerful | |

| Kind | 0.855 | −0.185 |

| Good at bringing up children | 0.849 | −0.090 |

| Sympathetic | 0.844 | −0.190 |

| Loyal to partner | 0.767 | −0.255 |

| Brave | 0.681 | −0.017 |

| Intelligent | 0.675 | 0.388 |

| Rich | 0.234 | 0.846 |

| Powerful | 0.308 | 0.829 |

| Wealth of Man | Cost of Altruism | n |

|---|---|---|

| Rich | High | 45 |

| Rich | Low | 46 |

| Rich | No | 39 |

| Poor | High | 49 |

| Poor | Low | 54 |

| Poor | No | 52 |

| Total | 285 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Iredale, W.; Jenner, K.; Van Vugt, M.; Dempster, T. Giving Guys Get the Girls: Men Appear More Desirable to the Opposite Sex When Displaying Costly Donations to the Homeless. Soc. Sci. 2020, 9, 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9080141

Iredale W, Jenner K, Van Vugt M, Dempster T. Giving Guys Get the Girls: Men Appear More Desirable to the Opposite Sex When Displaying Costly Donations to the Homeless. Social Sciences. 2020; 9(8):141. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9080141

Chicago/Turabian StyleIredale, Wendy, Keli Jenner, Mark Van Vugt, and Tammy Dempster. 2020. "Giving Guys Get the Girls: Men Appear More Desirable to the Opposite Sex When Displaying Costly Donations to the Homeless" Social Sciences 9, no. 8: 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9080141

APA StyleIredale, W., Jenner, K., Van Vugt, M., & Dempster, T. (2020). Giving Guys Get the Girls: Men Appear More Desirable to the Opposite Sex When Displaying Costly Donations to the Homeless. Social Sciences, 9(8), 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9080141