1. Introduction

In the UK, young people from disadvantaged socioeconomic family backgrounds still have considerably lower chances of studying at university than those from more favourable social backgrounds. The latest reports for the UK show it is still the case that by age 19, only 26% of students from low-income families access higher education (HE) (

Social Mobility Commission 2019). Thus, it is still a priority for policymakers in the UK to reduce inequalities in access to HE, and there continues to be a high need for knowledge about the processes that drive these inequalities. Recently, the Office for Students (OfS) has also asked providers of HE to focus on the opportunities for young people with the most disadvantaged backgrounds, by concentrating their outreach programmes on the geographical areas with the lowest rates of young people entering HE (

OfS 2019a).

Analyses of social inequality in access to HE generally focus on assessing differences between large groups of advantaged and disadvantaged students. For instance, rates of HE-enrolment or graduation are compared between students with free school meal status and students with no such status (e.g.,

Department for Education 2018), students with parents in working-class occupations and parents in the class-category of professional and managerial positions (e.g.,

Boliver 2013;

Reay et al. 2010), or students who are the first generation in their family to go to university and students who are from ‘traditional families’ (e.g.,

Spiegler and Bednarek 2013). Usually, there is little focus on the more fine-grained differentiation required to study groups at the extreme ends of the socioeconomic scale, i.e., groups with lowest income levels or living in the most deprived areas. However, as we argue in this paper, these extreme groups can be particularly interesting. This is especially true of the group of young people who are from the most disadvantaged backgrounds and who study at universities with high tariff, such as those in the Russell Group—sometimes referred to as the UK Ivy League. Among this group, school-leavers must have attained particularly highly in their secondary education, and at the prestigious institutions in question the representation of students from the most disadvantaged backgrounds is particularly low (e.g.,

Boliver 2013;

Hemsley-Brown 2015). By examining this group of students more closely, and by comparing them with students from more advantaged social backgrounds, we can learn about strategies, resources and circumstances that might help to overcome the most persistent barriers in access to HE.

Another characteristic of research on socioeconomic differentials in HE access is that it builds on a well-established theoretical foundation consisting mainly of two systems of thought. These are, firstly, cultural and social theories, and secondly, rational action theories. Cultural and social theories draw on capitals (social, cultural, economic) and the concept of ‘habitus’ introduced by the French sociologist

Bourdieu (

1973). This body of work reveals the reproductive tendencies of education; its hidden rules, curricula, and assumptions (

Reay et al. 2009) and its ability to create different senses of belonging and not belonging (

Araújo et al. 2014). Rational action theories (e.g.,

Breen and Goldthorpe 1997;

Breen et al. 2014), on the other hand, explain how bounded rational individual choices (

Simon 2000) create differential progressions and outcomes for individual students.

These two systems of thought have now been around for decades and have informed participation and outreach programme design and evaluation. Interventions conceived here tend to focus on confidence building, information giving, and creating new peer groups. These interventions have had some impact on participation in HE; however, as we have seen, parity of participation between social groups is still a long way off, and policymakers, practitioners, evaluators and researchers are thus keen to explore new concepts. A new theory has recently been put forward to explain inequalities in HE (

Harrison 2018;

Henderson et al. 2018a); it draws on the psychological research on possible selves by

Markus and Nurius (

1986). This model aims to take a ‘critical realist perspective, with its concern for a conceptual balance between structure and agency in understanding complex social fields and its focus on “middle-range” theory (

Merton 1968) that is meaningful for policymakers and practitioners’ (

Harrison 2018, p. 2). It provides a framework for understanding the student as an agent while considering social structure and developing practical recommendations for policy and widening participation activities at HE institutions (

Harrison 2018;

Henderson et al. 2018b).

In the present paper, we apply the theory of possible selves, as refined by

Harrison (

2018), to explore how students who study in their first year at an English Russell Group University, and are from the most disadvantaged backgrounds, formed their decision to go to university. We do so within a framework of proof-of-concept research, verifying the usability and practical potential of using this theoretical approach in HE transition research. Our study is of a small scale and does not claim to give insights that are generalisable to the entire university population. However, we can demonstrate the usefulness of using the possible selves approach and are able to suggest extensions to the model proposed by Harrison.

The possible selves theory has been used in quantitative data (

Oyserman et al. 2004), but we argue it lends itself to the analysis of detailed, individualised reflection and decision-making processes while considering structural circumstances. Moreover, as the theory is very precise, it allows the formulation of assumptions that can guide a deductive analysis of qualitative data. Against this background, the paper seeks to study the following key research question: Can the theory of possible selves explain differences and/or similarities in decision-making processes among advantaged and disadvantaged students at university?

We drew on qualitative data collected through semi-structured interviews with 12 students studying in Year 1 at a Russell Group University in England. We compared the decision-making of five students who are from lower socioeconomic backgrounds to seven students across middle and higher socioeconomic status. To facilitate and structure students’ reporting, we invited them to draw timelines that covered their childhood and teenage years; in these timelines, they indicated particularly positive or negative influences on their decision to go to university. Our analysis was guided by two further questions: (1) How did students from the most disadvantaged socioeconomic backgrounds, who are now studying in their first year at a Russell Group University, form their decision to go to university—what were the enablers and facilitators making this choice possible? (2) How did the decision-making of these disadvantaged students, and the mechanisms and barriers they encountered, differ from the experience of more advantaged students?

Our paper makes new contributions to research on educational inequalities through considering students at an extreme end of the socioeconomic scale, and testing

Harrison’s (

2018) adaptation of the possible selves theory, which he put forward as a basis for practical recommendations for widening participation in HE. Moreover, through letting students describe the development over time of their decision-formation, we gain insights into the early stages of this development, which is highly relevant to the creation of policies and programmes that can target the most disadvantaged groups at the

most relevant time. Finally, through using qualitative data, we can dissect the thinking and narratives about the planning of educational and occupational futures within a small and uncommon group of students, i.e., students from lower social backgrounds, who succeeded in attending a prestigious university.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Social Inequalities in the Formation of Aspirations, Expectations and Decisions

There is abundant research quantifying and exploring socioeconomic differences in young people’s wishes and choices relating to entering HE. In the following sections, we provide an overview of some recent UK studies that give insights into the processes that underlie young people’s decision-formation. We also present studies investigating aspirations and expectations, as these are two key concepts associated and overlapping with decision-making. These concepts also help differentiate between quantitative and qualitative/mixed-methods studies to highlight methodological aspects and how they are connected to certain results.

In recent years, the concept of aspiration has come under increasing criticism; it has been dismissed for being too vague, and for lacking sufficient stratification (in terms of student social background) to drive reform with regard to social inequalities in HE (

Department for Business, Innovation and Skills 2014;

Baker et al. 2014;

Cummings et al. 2012;

Harrison and Waller 2018;

St. Clair et al. 2013). Baker et al. found in 2014 that both disadvantaged and advantaged students had generally high aspirations, with no evidence of causal relationships between aspirations and outcomes; we are in line with these authors in questioning the value of aspiration as a gauge by which to resolve educational inequalities. This perspective is also supported by evidence from

Anders and Micklewright (

2015), who draw on the Longitudinal Study of Young People in England (LSYPE) to suggest that aspirations are not distinctively different between advantaged and disadvantaged students when it comes to enrolment at university.

Theories around the formation of decisions and expectations have started to receive more attention in this area, which is also reflected in the possible selves model: ‘possible selves embody an element of expectation about what might happen rather than simply what the individual wishes would happen’ (

Harrison 2018, p. 9). They follow-up on the evidence showing that while there are no stark differences in students’ aspirations (i.e., what a student hopes for) between socioeconomic groups, expectations (i.e., what a student thinks will happen and their plans) do vary importantly by social backgrounds (see literature review below). While we agree that aspirations may be less critical for understanding social stratification in HE participation than often argued, some of the literature on aspirations gives important insights into young people’s reflections about HE (

Baker 2017), and can therefore help explain their pathways and decision-making. Some longitudinal studies on the aspiration-, expectation- and decision-formation of young people in the UK are especially interesting as a background for our research.

2.1.1. Quantitative Research with the LSYPE

Using the LSYPE—a rich panel study, that began in 2004 and followed more than 20,000 young people then aged 13–14—a number of investigations of relationships between student socioeconomic background, aspirations, expectations, and enrolment in HE were undertaken. Overall, the findings of these investigations highlight the important role of previous attainment, e.g., Key Stage 3 and GCSE results. Some also provide evidence for the relatively minor relevance of aspirations, depending on their definitions of the term.

Croll and Attwood (

2013) show that when comparing one socioeconomic group with another, differences in student aspirations (how likely a student thinks it is that they will apply to go to university) at age 14–15 years are lower than the actual differences in attending HE when 20 to 21 years old. This socioeconomic difference is largely driven by attainment at age 16.

Khattab (

2015)—who terms Croll and Attwood’s aspiration variable ‘expectations’ and uses it as an aspiration measure to assess the degree to which a student wants to stay in full-time education after age 16—finds that a combination of high expectations, aspirations and attainment is a strong predictor of going to university. However, high aspirations ‘on their own’ also have important positive effects on HE attendance. Using similar variables,

Anders and Micklewright (

2015) further show that the association between a student’s social background (parental education) and their expectations increases with student age and, again, previous attainment predicts university applications. Recently,

Gutman and Schoon (

2018) included a variable that captures socially stratified personal beliefs and attitudes of students—student emotional engagement in school. They found that Year 9 student attitudes—such as finding schoolwork a waste of time, or enjoyment of being at school—were associated with student social background and predicted HE aspirations (planning post-16 full-time education) and attainment.

2.1.2. Qualitative and Mixed-Methods Research

Beyond the importance of attainment, qualitative and mixed-methods research reveals that economic resources, knowledge of how to increase attainment and realise one’s aspirations, a sense of agency, and significant others such as teachers, are critical for young people’s reflections and decision-making about HE.

St. Clair et al. (

2013) interviewed students, their parents and their teachers in schools in socially deprived areas where aspiration-emphasising policies had been implemented. Collecting data at two time points (13 and 15 years of age), they found that aspirations to go to university were very high among these students but that their levels of understanding and support, in terms of raising attainment, seemed insufficient for them to realise their ambitions. The study also revealed the importance of family members for modelling of occupational aspirations, and students’ perception of differential support from teachers.

Tett et al. (

2017) longitudinal qualitative study on ‘non-traditional’ students in a Scottish university provides further evidence for the important role of lecturers and peers in shaping self-esteem, building strategies to achieve educational goals and mastering important transitions in educational pathways. Additionally,

Lahelma’s (

2009) longitudinal study of young people’s reflections about their educational decisions and pathways (academic versus vocational routes), at different ages between 13 and 24 years, reveals the crucial role of significant others, and further highlights the tensions between agency and structural resources. Students’ agency, and how this can be limited by structural constraints such as limited economic resources, is also reflected in the narratives of English students in Further Education Colleges, in a study by

Baker (

2019). She analyses data from interviews, focus groups and diaries, using Archer’s reflexivity theory, and shows how young people, from social groups that are underrepresented in HE, are able to adjust their HE strategies and decision-making as contexts and constraints change. Similarly, in

Baker and Brown’s (

2007) analysis of ‘non-traditional’ students’ experiences at ancient prestigious universities, some participants had very individualised reflexive thinking and appeared to be ‘consciously, actively breaking away from their social backgrounds’ (

Baker and Brown 2007, p. 388).

This selection, of relatively recent evidence from the UK, highlights processes and factors that are related to student socioeconomic background and shape their aspirations and decisions regarding HE. As will be further shown below, many of these findings are in line with the core ideas of the possible selves model.

2.2. The Theory of Possible Selves

The possible selves model as proposed by

Harrison (

2018) draws heavily on the work of

Markus and Nurius (

1986), and on the idea of ‘self-concept’—people’s visions of themselves in a specific social context. Within the existing traditional theories, Harrison situates the model between

Boudon’s (

1974) ‘primary effects of social stratification’—i.e., social class differentials in school attainment—and Bourdieu’s concept of habitus. The possible selves theory assumes that we ‘form a future tense for the self-concept, representing our current perceptions about where our lives lead’ (

Harrison 2018, p. 4). Over time we develop and readjust ideas of the future identities that we can and want to imagine for ourselves, and those that we would like to avoid (

Markus and Nurius 1986).

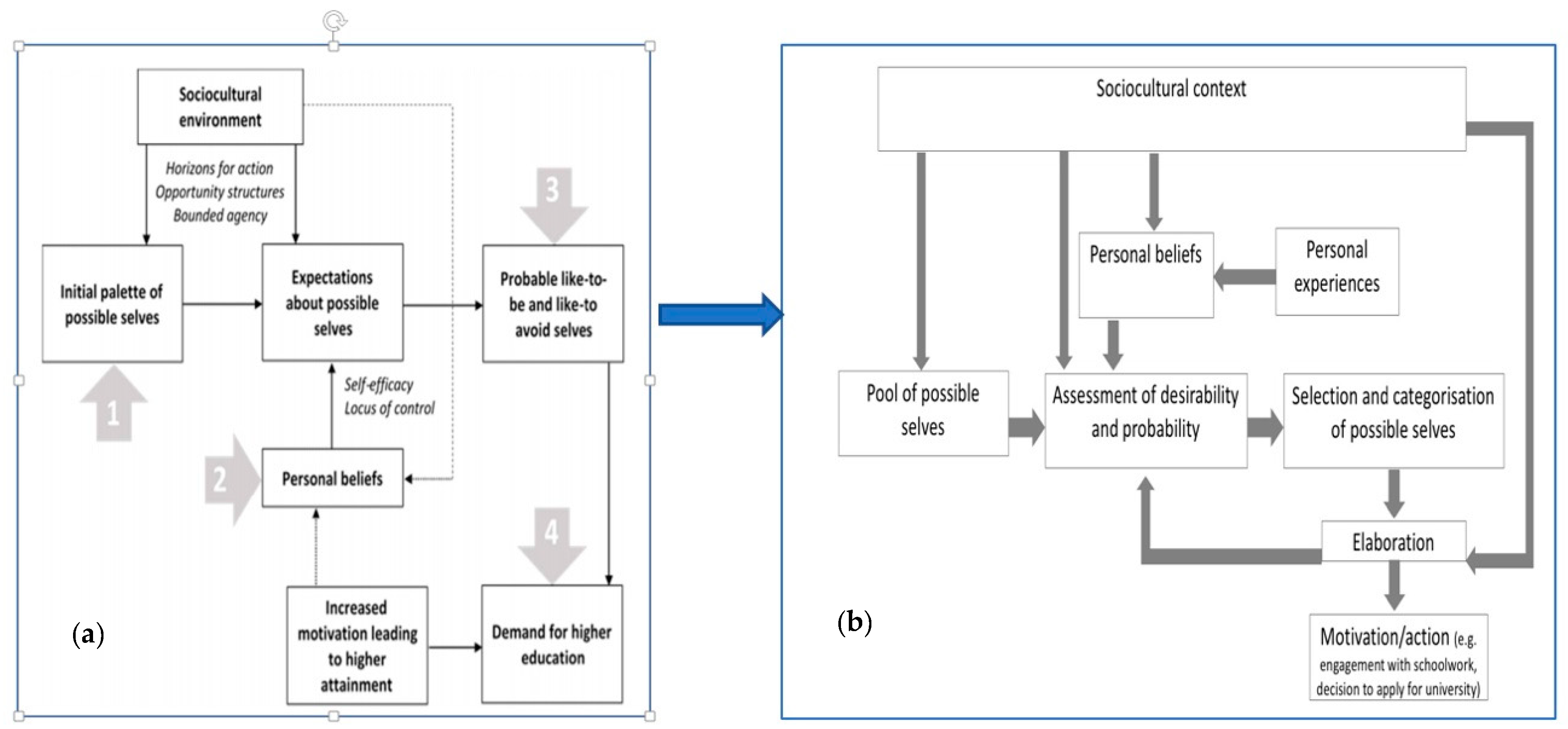

To explain students’ decisions to invest in their education, Harrison argues that young people’s decision-formation starts with the development of a pool of possible selves—a range of more or less clear visions of who they could be in the future. Harrison’s original diagram is displayed in

Figure 1a (

Harrison 2018, p. 11). We have extended his model for the purpose of the present paper (

Figure 1b), to emphasise a temporal sequence of concepts or steps (from left to right and downwards); and we have included some further details—for example, ‘assessment of desirability and probability’ and ‘elaboration’—to show how we see the derived Harrison model underpinning our research.

Figure 1b illustrates how the theory’s core concepts interact and lead from the pool of possible selves to a motivation or action, which—in the HE context—is the effort put into increasing school attainment in order to get access to university. The pool of possible selves is influenced by the sociocultural context students grow up in, which means that gender, ethnicity and social class can importantly contribute to its formation. The live situations and educational or occupational pathways of family members and other close associates are often models for these initial possible selves.

The sociocultural context, together with personal experiences, also shapes young people’s personal beliefs about themselves. Corresponding to concepts such as ‘locus of control’ (LoC) and ‘self-efficacy’ (SE), these beliefs represent young people’s assessments of whether they can achieve what they aim for (SE) and whether succeeding in what they do depends on their own abilities and will or those of others (internal versus external LoC). Personal beliefs and sociocultural context influence a core process in the model, which is young people’s assessment of (1) the desirability and (2) the probability of each of the different selves. On the basis of what they learned and experienced in their families, neighbourhoods and schools, and because of images in the media and social experiences, they form expectations about possible selves, and categorise them as ‘like-to-be’ and ‘like-to-avoid’. Again, this stage of decision-formation is highly influenced by cultural and structural circumstances associated with gender, ethnicity and social class.

Another critical assumption of the theory is that possible selves are more likely to lead to motivation and action if they are vivid and ‘easily accessible’ in a person’s mind, and if the person has a ‘roadmap’ (

Oyserman et al. 2004), i.e., a plan of the steps that need to be taken to achieve a certain possible self. Drawing on the psychological literature (

Markus and Nurius 1986;

Ruvolo and Markus 1992), Harrison argues that elaboration is ‘the extent to which possible selves are fully-formed and detailed, with a vivid vision of what that self would be like and the intermediate steps needed to get there’ (

Harrison 2018, p. 6). Possible selves are important drivers of motivation and action when they are well-elaborated because they are then compelling and easily evoked in everyday activities (

Bak 2015;

Hardgrove et al. 2015;

Erikson 2018). This holds to the same extent for both like-to-be and like-to-avoid selves. A high level of elaboration depends on the frequency and ease with which a possible self comes to a person’s mind; on whether it is supported and legitimised by significant others—such as parents, teachers, friends; and on whether it is in line with prevailing norms in the person’s context or wider society. If a young person regularly and intensely perceives ‘university graduate’ as a probable and desirable future identity, they will increase their engagement with schoolwork, resulting in higher school attainment, which in turn affects the assessment of the probability of the possible self.

As we understand the model, expectations are formed through a complex processing of perceptions of various factors. These may be objective (e.g., labour market opportunities), subjective (e.g., a feeling of being discriminated against), or personal (community ties). This processing leads to a less elaborated possible self as ‘university student’ for disadvantaged young people than for advantaged ones. Elaboration is a key mechanism through which inequalities emerge, because significant others and everyday experiences make a self present and vivid in a person’s mind. The everyday short-term actions (e.g., engaging in schoolwork) that one undertakes as a consequence of a high elaboration level feed into a reassessment and possible adjustment of the probability and desirability of a self. For instance, if school attainment rises, this indicates that the self ‘university student’ is more probable.

How do possible selves lead to social inequalities in educational attainment? Even though possible selves are highly individualised, they are ‘socially determined and constrained’ (

Markus and Nurius 1986, p. 954). Sociocultural context shapes (1) the pool of possible selves, (2) expectations (i.e., the assessment of the desirability and probability of different selves), (3) the level of elaboration, and importantly, (4) the availability of a strategy, plan or ‘roadmap’ to achieve a possible self. A young person growing up in a family with parents who have HE degrees is considerably more likely to use their parent’s attainment as a model for their own possible self. This vision will not only be part of the pool of possible selves; norms and values present in the family will cause it to be rated as highly desirable. Parents are likely to support this plan, and experiences at school and in other social contexts will have taught the young person that achieving an HE degree is realistic, given their background and abilities. Moreover, this self is likely to be highly elaborate; parents might be mentioning their HE experience regularly, teachers might often indicate that going to university is a suitable plan for the young person, and there is liable to be a good level of knowledge in the family and the family’s networks about how to access and master university studies.

In contrast, a student from a more disadvantaged background, e.g., a student with two parents who did not go to university, is likely to develop, assess and categorise possible selves in a very different way. The identity ‘university student’ might not be part of their pool of possible selves at all, because there are no family members who can act as role models, or teachers who propose this option. Even if this vision is present, it might not be valued as desirable or probable, because again, there are no models to follow and ‘young people from disadvantaged communities can become conditioned to expect failure through negative stereotyping, self-fulfilling prophecies, and an objective scarcity in opportunities (

Prince 2014)’ (

Harrison 2018, pp. 11–12).

2.3. Summary and Framework for Empirical Study

The aim of our proof-of-concept study is to see whether using the lens of possible selves is a useful theoretical framework for understanding how students from the most disadvantaged backgrounds, who study at prestigious universities, developed the decision to go to university; and whether (and if so, how) this contrasts with the decisions of more advantaged students. In our view, there are three main reasons why the possible selves theory provides a useful and interesting theoretical framework for our study. Firstly, it suits our qualitative approach because it allows for complex, interrelated processes of assessments, categorisations and decisions rather than assuming more uniform, specific and therefore quantifiable mechanisms. Secondly, this openness to complexity enables us to capture the very personal and individualised thoughts and decision-making (

Henderson 2018) of the ‘special’, less common cases that we partly focus on in this study—those students from the disadvantaged end of the socioeconomic background scale going, against all odds, to university. Thirdly, Harrison’s adaptation is at the same time specific and clear enough for the derivation of assumptions that can be used to direct a deductive analysis of qualitative data.

The possible selves model has a ‘micro-level’ component, as it perceives young people as agents who make conscious decisions about actions; and a ‘macro-level’ component, on structural and cultural circumstances influencing and framing young peoples’ thinking and consequent actions. The sociocultural context young people grow up in provides them with a palette of possible selves, which they categorise in terms of probability and desirability. This evaluation of different possible selves is influenced by factors, associated with sociocultural context, that have been addressed in previous studies: beliefs about themselves (

Baker 2019;

Tett et al. 2017); significant others (

St. Clair et al. 2013;

Lahelma 2009); personal experiences and prevailing norms (

Baker and Brown 2007). If a young person has a possible self with a well-elaborated meaning that is internalised with a clear and strong image including a roadmap of the steps necessary to produce that self (or to escape it, if it is a like-to-avoid self), then it can motivate and lead to action (

Tett et al. 2017;

St. Clair et al. 2013). An example of this would be increased effort in school with the aim of achieving high levels of attainment in order to access university. We applied this theory to the situation of young people from the lowest socioeconomic categories, who succeeded in going to a high-status university. We analysed their highly personalised and individualised accounts of whether and how young people imagined possible futures as university students, and their motivations to overcome strict barriers created through structural circumstances.

More specifically, we assume that the theory is supported by the data if the following empirical patterns emerge through our deductive analysis: firstly, the core constructs in Harrison’s adapted model—pool of possible selves, like-to-be and like-to-avoid selves, personal beliefs, personal experiences—are identifiable across the participants’ narratives; secondly, the core processes of the model—influence of social context including family, peers and teachers, assessment of desirability and probability, selection of selves and elaboration—are observed across the interviews; and thirdly, substantial differences in constructs and processes, between students of different social backgrounds, are uncovered.

4. Results

Our analysis of the interview transcripts revealed patterns of description and argumentation that can be organised under the model’s constructs—desirability and probability of possible selves, personal beliefs, elaboration and roadmaps. In the following, as we present each of these ‘themes’, we distinguish students with POLAR Q1 and Q2 backgrounds (‘most disadvantaged’) from students with POLAR Q3, Q4 or Q5 backgrounds (‘more advantaged’), in order to explore the mechanisms that generate social inequalities in decision-formation. We also indicate a respondent code (RC) so that more details on students’ characteristics and backgrounds can be looked up in

Table 1.

4.1. Desirability and Probability of Possible Selves

Across the interviews it became apparent that all POLAR Q1 and Q2 students clearly highlighted like-to-avoid selves, and saw going to university as a way of avoiding their disadvantaged backgrounds; and also as a way of avoiding reproducing that pattern of disadvantage in their own future lives. For instance, two students with POLAR Q2 backgrounds said

‘I’ve never really aspired to be anything. I’ve tried to move away from things that have annoyed me’ (RC4)

and

‘I […] wanted to get out of where I lived, because I could sense how horrible it was to stay in that environment and not get out’ (RC11),

and a student with a POLAR Q1 background (RC5) explained

‘I think I had everything to lose by not going to university… I think stuck in a 9:00 to 5:00 job and I would never have got out. I would be living in a council estate and I would be stuck’

and

‘[…] I’d had it quite difficult for a lot of my younger years in life, I was even more determined to get out of this lifestyle, to get out of not particularly having enough food or enough things in general.’

By contrast, the students who had grown up in POLAR Q3 to Q5 areas talked about their futures more vaguely. Some indicated that going to university had been the only path because, for instance, everyone in their school was going there (a student with a POLAR Q3 background, RC1) or because they knew early that the desired occupation (e.g., medical doctor) or working conditions (e.g., a good income) were only achievable through university studies. The striking difference between the advantaged and the disadvantaged students was that the arguments of the advantaged were articulated positively, in a way that could be interpreted as like-to-be selves.

Regarding student evaluations of the desirability of going to university, we found that across the backgrounds, going to university was attractive; not only because of career prospects in general but also because of positive expectations that had been associated with everyday life as a student. These were, for instance, living with room-mates, being ‘actually happy as mature young adults’, studying on a beautiful campus and in new buildings, making new friends and ‘lots of opportunities for sports which I love’. It was also mentioned that open days, with enthusiastic lectures by professors, and services for the promotion and assurance of student wellbeing, had fuelled interest in and desire for the possibility of going to that specific high-status university.

4.2. The Role of Information, Finances and Significant Others

Information about how to get into university and about financial support seemed critical for the assessments, by disadvantaged students, of the possibility of going to university. Moreover, as highlighted in these quotes, the role of the necessary monetary resources was linked to the desirability of going to university:

‘No, I didn’t think it [university] was achievable. I thought it was a place where people with more money went, and I still see that now. It’s quite hard to live at uni. I really struggle… We [student and his stepfather] really argue. It’s like hell, so I’ve sort of tried to get away from him, and doing that, I realised I needed money, and the best way to do that is to go to uni and get a job’ (POLAR Q2 student, RC3)

and

‘Up until Year 11, I didn’t actually think it was possible for me to go. That’s probably due to my own lack of information. I hadn’t checked that you can get loans, you can get all these things. I thought because of our financial situation there was absolutely no chance that I would ever go to university’ (POLAR Q1 student, RC5).

Again, students from advantaged backgrounds seemed more imprecise about how they had evaluated their individual likelihood of going to university. They mentioned that the school they attended had promoted academic attainment, or that everyone in the school had the same plan; but they did not describe as many specific influencing factors. As a quote from a POLAR Q5 student (RC4) shows, the young people are aware that their background plays an important part. ‘It’s just the way I think a lot of people I know see it, or see their life, if you just go up a chain, you do it, I guess that’s just where I’m from.’ The trajectories of advantaged students often followed the path of one or more of their family members, with their peers very much in the same situation, and it seems that for them, not going to university was improbable.

When it came to specific persons, events and conditions that had influenced the students’ perceptions that university studies were probable for them, the respondents with disadvantaged backgrounds mentioned teachers and counsellors as positive influences. These, however, only seemed to support them because they had good grades and showed an interest in learning. Students with advantaged backgrounds indicated their parents and teachers as influences as well.

‘my dad was like, you’ve got to go to uni, so it’s something I’ve always gravitated to. I didn’t think I had a choice’ (POLAR Q5 student, RC4)

and

‘especially my classics teacher, she gave me, when we had like a split class presentation, she gave me a piece of work twice the size because it was like “this is what you’ll do at university”. In her mind there was no question that I should go to university and shaped my mind to that’ (POLAR Q5 student, RC2).

4.3. Personal Beliefs

In line with the theory, there seems to be a high level of SE (i.e., belief that one can achieve what one aims for) and/or internal LoC (i.e., belief that one’s success is determined by oneself and not by external events and conditions), across both the advantaged and disadvantaged students we interviewed. The disadvantaged students were faced with barriers that could only be overcome if they strongly believed in their abilities. For instance, a POLAR Q2 student (RC3) seemed to demonstrate a high level of SE in recognising their own academic capabilities and an internal LoC in believing in their position to improve their academic circumstances:

‘When I moved back to my old primary school, which was where my dad lives, I was put on, like, the bottom table. That really annoyed me because I knew I was better than that, so I worked hard for that, and then I got to the top, well, I think it was one off the top, by the end of the year […] when somebody thinks I can’t do something I would much rather prove them wrong and show them I can do it.’

The following quote illustrates the critical importance of school attainment. The beliefs are worded in general terms, but in the specific situation they were about whether a student would be able to achieve high levels of attainment. The remark also highlights how the disadvantaged students need an ability to contextualise their attainment, and understand how their family life and background affects their performance, in order to overcome this potential barrier:

‘So I was quite... I was disappointed because I was hoping to do better at GCSEs, but at the same time I was like, the amount of pressure [helping out a lot at home] that had been on me, I did pretty well. […] I like to challenge myself with these things. […] If I can’t do something, then I’m always, like, well, I’ve got to’

(POLAR Q1 student, RC5)

In contrast, advantaged students seemed to place more stress on non-academic skills, such as social skills. Hence, their high levels of SE could be seen as being expressed in non-academic terms. They reflected on their ability to find friends at university, and attainment seemed a bit less of a concern:

‘I think it was knowing when I was intelligent in other places. So, I knew that I was quite witty, I can crack a joke, like I’m on Mock the Week or something and jump on something really quickly. And some things when I get to think about them and I’m interested in them, I can definitely hold a conversation on them’ (POLAR Q5 student, RC2)

or

‘Like, my family are all quite heavily introverted, and I’m definitely not’ (POLAR Q4 student, RC7).

This could indicate that for more advantaged students, their belief in their abilities to succeed academically (SE) and their power to influence their academic situation (internal LoC) is so self-evident that they would not talk about it without prompting. Instead, they focus on skills ‘beyond’ academic abilities and attainment.

4.4. Elaboration and Roadmaps

Since all of the interviewed students went to university in the end, they had all developed, at some point, a relatively highly elaborated self as ‘university student’. The differences between disadvantaged and advantaged students appear to lie in the areas of when and for how long the elaboration took place, and who and what influenced it. For advantaged students, as described above under the theme desirability and probability, the path to university was present in everyday life in school and in the family from early on. As a POLAR Q4 student (RC7) puts it:

‘We’ve always heard a lot of stories when we were growing up from my parents about what it was like when they were at university because they met there. People are still in contact from university. So, there was definitely a strong, kind of, we knew about the existence of university and what it was like to go there, and both the pros and cons. We had a realistic image of university in terms of it’s hard work, but you do get a lot out of it at the same time.’

In contrast, students from disadvantaged backgrounds tended more to indicate that one main teacher, friend, distant family member, or a widening participation initiative (e.g., AimHigher) had helped significantly in forming their vision of going to university. However, this had happened at a later, more specific and often shorter time period. More importantly, these students indicated a high level of elaboration (i.e., a vivid and clear vision of a future that they were being confronted with every day) for negative selves, i.e., like-to-avoid selves. Some of them had even initiated some form of negative elaboration-process for themselves in order to maintain high levels of motivation towards going to university:

‘I worked in the slaughterhouse for about six months, and that was really good. I’ve always worked in really rubbish jobs. I worked for [large chain of pubs] for three years. Don’t work for [large chain of pubs]. Working in these jobs keeps me on the straight and narrow in education because they’re just terrible jobs which you don’t want to work […] working these jobs, you realise it’s not the sort of life you want. Why would you want to work in a slaughterhouse? My dad is [older], and his back hurts, his arm hurts, because he’s having to try and pull skins off of 200 kilo rounds […]’

(RC3)

Advantaged students had similar thoughts when working in jobs when they were younger. However, these thoughts did not seem as impactful as they were for disadvantaged students; the influence of peer networks and family was emphasised more. A quote from one interview with a POLAR Q5 student (RC4) exemplifies this:

‘[I] worked in a pub for a year when I was in sixth form, for money, and I realised how unsafe work could be without a qualification, and a steady, serious job, so I thought, well, I’ve got to do that… think the school I went to, almost everyone went to university.’

Regarding the development of ‘roadmaps’ to possible selves, the answers from our respondents showed that—while students knew that getting a degree was important for many career choices—once they were made aware of university, there did not seem to be specific planning for going to university beyond getting the grades and going through the UCAS (Universities and Colleges Admissions Service) process. However, we also found that, with the help of their personal beliefs, disadvantaged students would follow this roadmap ‘to university’ even when they were advised to take another path. The following quote seems to exemplify these roadmaps, as well as high levels of SE and an internal LoC, in that they believed they could do better so they retook their A-levels:

‘I retook a year of A-levels. When I did my A-levels to start with, I got a B, two Es, and a U. I retook, and I got three As. They wanted me to do business studies and do a diploma, but I decided to retake my A-levels’

(POLAR Q2 student, RC3)

The information sources that were used for the ‘roadmaps’ varied and appeared to depend on the social background of the student. Older brothers and sisters and other family members, open days and career fairs provided the basis for the plans of students from more advantaged backgrounds, while specific teachers or initiatives like Teach First were an important information source for students with disadvantaged backgrounds.

5. Discussion

We applied the theory of possible selves to 12 interviews with first-year students from different social backgrounds, to investigate the explanatory power of the theory for understanding the decision-making that led to participation in HE at a selective, high-tariff university. The advantage of studying first-year students was that the experiences and thinking that had shaped their decision to go to university was relatively recent. A caveat to interpreting our findings is, however, that our study concerned only disadvantaged students who had succeeded in accessing HE. As we interviewed a small self-selected sample of their peers who are disadvantaged, we are unable to comment on the formation of possible selves for those disadvantaged students who did not pursue HE.

We found interesting differences, between our more and less advantaged respondents, in the way the possible selves were formed. In line with other studies, we found that those from less advantaged groups arrive at HE by means of a conscious choice and are very clear about what futures they do not want (

Baker 2019). It appears that ‘impossible selves’, i.e., futures the participants desperately wanted to avoid, motivated their actions and decisions. This contrasts with viewing HE as a ‘default’ option among more advantaged students. Having to make a choice and conscious decision is in itself a process that requires time and thinking resources—and often also external stimuli or conversations—and is thus a first barrier disadvantaged students have to overcome in order to start envisaging themselves as HE students and pursuing this future self. Our analysis further reveals, in line with existing evidence (

Lahelma 2009;

St. Clair et al. 2013;

Tett et al. 2017) and seminal theory (

Sewell et al. 1969), that significant others such as teachers and family members, or outreach initiatives, are critical for this stimulation, or—as the possible selves theory terms it—elaboration process. Importantly, we also showed that attainment and ‘enjoyment of learning’, demonstrated early in school, are crucial prerequisites for this support from others.

We also found differences by social background regarding the expected purpose and experience at university. Here, the more advantaged students tended to put more emphasis on social aspects and friends, whereas the less advantaged students found these issues important, too, but seemed to focus slightly more on the academic side. This focus has socially reproductive tendencies, as other studies highlight; the focus of privileged students on networking and extra-curricular experiences translates into advantageous labour-market outcomes, over and above a sole focus on academic attainment (

Armstrong and Hamilton 2013;

Bathmaker et al. 2013).

2Our respondents converged, however, regardless of background and gender, around a model of individual agency, high levels of self-efficacy and an internal LoC. This meant that academic success was viewed firmly as within reach depending on individual efforts. This focus on individual agency rather than structural constraints has also been found in other work on students at selective universities, highlighting the supremacy of individualised discourses of success for the deserving (

Warikoo and Fuhr 2013). This approach is, no doubt, empowering for those who succeed; but on the flipside, it raises concerns about the possible selves for those who do not. Moreover, it is only empowering as long as individuals ‘read’ the structural barriers correctly, and therefore draw on their resources (personal beliefs and abilities, familial and institutional support) adequately to overcome them. For a comprehensive picture, future research should study how personal beliefs shaped the possible selves of young people from disadvantaged backgrounds who did not go to (a high-tariff) university. It is probable that in these cases ‘structure “trumped” agency’ (

Baker 2019, p. 10;

Lahelma 2009) and like-to-avoid selves induced standstill and ‘learned helplessness’ (

Barnett et al. 2019, p. 2328).

Using the theory of possible selves has enabled this project to make sense of convergences and differences in the experiences of advantaged and disadvantaged students at a high-tariff university in the UK. The timelines we used as visual aids during semi-structured interviews supported students’ reflections on their decision-making and helped collect data that could be analysed against the background of this theory. We discovered that the process of envisaging a possible self was related to background, and that academic and extra-curricular considerations played different roles, in the envisaged university selves, for different student groups. We could thus demonstrate how aspects of social structure influence the highly individual construction of possible selves and thus the interaction point between sociological and psychological approaches to understanding HE participation. This association between social structure and students’ plans and projections is also what makes the possible selves theory more useful for explaining social inequalities in HE participation than the typical aspirations-approach of some of the recent policy and research. Personal beliefs, such as internal LoC, and attainment in school seemed to be important for all respondents regardless of circumstances. Although we cannot conclude that the students we interviewed thought their academic achievements were solely the result of their own abilities and hard work, they did believe that hard academic work would benefit them, and they were willing to try. In that sense, their narratives were broadly aligned to discourses of individualised success and failure (

Warikoo and Fuhr 2013).

A rational choice approach would have led us to map individuals’ decisions in relation to their starting points in life. While such starting points mattered in discourses, drawing on the discourse of ‘possible selves’ has enabled us to focus more on how images of the future have shaped journeys into HE, and how agency and structure interact. Moreover, the narrative of LoC and SE among respondents highlights that shaping of journeys, in contrast to social and cultural theories that emphasise structural barriers. Disadvantaged students have fewer resources, and are less orientated to leveraging those resources—for example resources within themselves, their families and institutions—that are available to overcome these barriers. Our participants exercised a high level of agency to succeed, despite and also because of their consciousness of such barriers. While

Harrison (

2018) argues that the possible selves theory has links to Boudon’s 1974 concept of primary effects, we see instead more convergence with the secondary effects (social stratification in educational decisions given same levels of attainment) and rational choice approaches. This is because attainment and the pleasure of learning play an important role in young people’s evaluation of the probability of possible selves. These things also affect their personal beliefs and are necessary to get support from significant others such as teachers. This support, in turn, promotes the probability evaluation and elaboration of possible selves. Possible selves lead to more than engagement in schoolwork; they lead to the decision to go to university, and engagement in schoolwork needs to be demonstrated through attainment early on before this possible self can affect any early motivation and action. As put forward in many previous studies (e.g.,

Chowdry et al. 2012), early attainment and associated support from school staff are key for guiding disadvantaged young people into HE.

As pointed out before, it must be kept in mind that our study is based on a very small sample, which cannot be representative of the whole of the student population. A further limitation is that our research design does not enable us to approximate the counterfactual situation, i.e., the educational trajectories of our respondents had they grown up under different (sociocultural) circumstances, had they had different personality traits or different previous attainment levels, for instance. We therefore cannot make suggestions such as certain personality traits (e.g., internal LoC and high levels of SE) enable students from disadvantaged backgrounds to enter prestigious universities. However, in addition to the theoretical contribution, using the lens of possible selves has the potential for enhancing practices to support students at the research university and other universities. The project was conceived against a policy background of increased participation from students from disadvantaged areas. However, there was at the same time a lack of appreciation of whether the trajectories into university and the aspirations at university, of these disadvantaged students, were the same as those of students from more advantaged backgrounds.

The findings show that once the students reach university, the institution can provide more support for the less advantaged by appreciating the importance of non-academic and informal opportunities, but also by supporting students in continuing to imagine positive future selves. Thereby it is important to carefully make the students aware of the socioeconomic barriers that they might face so that they are not surprised and discouraged when their individualist self-concept meets difficulties such as academic problems or discrimination. At the same time, such awareness should be created only while effectively protecting students’ optimism, expectations for social mobility and their vision of themselves as university students. This could be done, for instance, through helping them strengthen their university attainment early on as they themselves tend to turn their attention towards it only once they feel socially integrated (

Tinto and Goodsell 1994). Our findings also show that careers support focus not only on the ‘how to’ of getting jobs, but on enabling students to create new versions of their future selves, and then helping them fulfil those new versions. While not studied explicitly in the present project, there also seems to be a clear inverse of the positive future-selves success stories shared by our participants. The unprecedented demand on mental health and wellbeing support at universities (

Thorley 2017) might just be the flipside of the positive power of self-efficacy and the focus on individual possibilities; in cases where things do not progress according to plan, there may be little scope for failure in the successful imagined self.

To conclude, this proof-of-concept application of Harrison’s adaptation of the model of future selves, and the extension proposed in the present article, showed that the possible selves framework combined with a timeline approach resulted in rich data for aiding our understanding of the thinking processes that accompany decisions to study in HE. This suggests that the possible selves model is a useful theoretical tool that allows researchers new ways of researching, exploring, and explaining differences in HE access and experiences. The model also provides a useful framework that practitioners and policymakers could draw on to enhance practice. At the case study institution, the research from the present article is already informing changes to student support, advice, and guidance; and is thus impacting academic practice.

Further research is required to apply the possible selves framework to a larger sample of participants, to explore its usefulness in a comparative study of those who have chosen and those who have not chosen to participate in HE, and to explore intersections such as that between ethnicity and socioeconomic background. More evaluation is also required to ascertain the impact of policy interventions, based on possible selves framing, in achieving greater student support; and to judge whether and how such interventions enhance greater equity in access, progress and success in HE.