A Framework to Inform Protective Support and Supportive Protection in Child Protection and Welfare Practice and Supervision

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Setting the Scene

1.2. Introduction to Irish Child Protection and Welfare System

2. Results

2.1. Introduction

2.2. Summary of ‘Protective Support-Supportive Protection’ Framework

- Levels 2–4a: These levels relate to what we referred to as ‘families in the middle’ who make up the majority of users of child welfare services needing support and/or protection at a point in time or over a life-time. These are families with high levels of need and/or risk concerns.

- Level 4b: Families who need more formal civic and criminal legal intervention that requires an explicit socio-legal intervention in partnership with courts and police services. While the commitment to protective support and supportive protection is still present, it is overlaid with explicitly socio-legally mandated work. This includes working in contexts where the ‘potential subjectivity’ (See Philp 1979; Skehill 2004; Hyslop 2018) or possibility of change in the interests of the child is outweighed by objective harmful and/or illegal behavior that requires civil and criminal legal interventions.

- Levels 1a and 1b: These relate to universal services and the public, which are differentiated between formal universal services and informal natural networks and supports. We argued that more emphasis should be placed on strengthening both formal and informal aspects of these levels.

2.3. Knowledge Base Informing the Framework

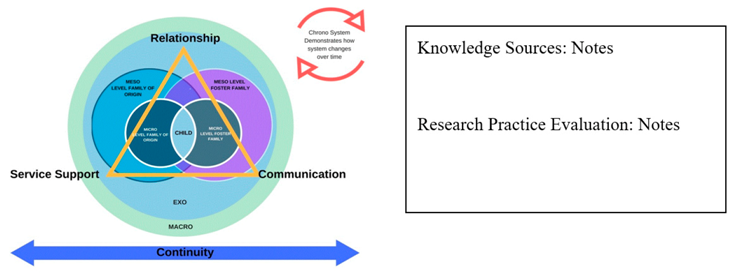

2.4. Using Bio-Ecological Model to Develop Further a Practice and Supervision Framework

2.4.1. Brief Overview

2.4.2. Person(s)

2.4.3. Process

2.4.4. Context

2.4.5. Time-Chrono

2.4.6. Reflections on the Bio-Ecological Framework

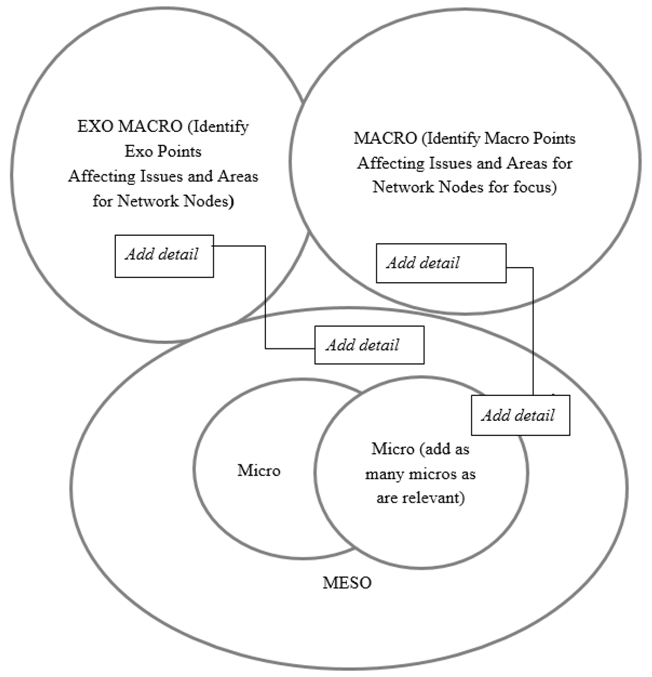

2.5. Networks and Networking in Child Protection

3. Discussion and Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Sample Discussion Tool for Practice Development and Supervision 1: Mapping Practice with the Bio-Ecological Framework

| Bio-eco Level | Issues for Specific Practice, e.g. | Issues for Own Professional Development | Skills/Values Comment | |

| Person | E.g., impact of abuse | E.g., empathy impact on self - self-care | Balancing therapeutic and socio-legal skills | |

| Process | What level of support and protection needed | Map own approach to protective support and supportive protection | Balancing assertiveness and supportive skills | |

| Context | Micro | Quality of own network | Mapping individual context with child/young person or parent | Empathy, observation, confidence to draw and use maps |

| Meso | Relationship with social worker | Awareness of power of interactions between meso-micro | Mediation skills | |

| Exo | Impact of lack of community place | What network node can you use, e.g., local Child and Family Support Networks (CFSN) | Confidence, knowledge, relationships | |

| Macro | Experience of inadequate housing | What resources has individual got, e.g., local politician. What network node, e.g., ask manager to engage with Children and Young People’s Services Committees (CYPSC)/local housing department | Critical awareness of issues of housing and link to welfare needs | |

| Time | Chrono | Impact of online bullying | Staff shortages and limited time | Ability to upskill to be aware of new trends and challenges |

| Moments | How does person experience your intervention at this moment? | Awareness that your moments of interaction can have great power | Ability to see and analyze power relations | |

Appendix B. Sample Discussion Tool for Practice Development and Supervision 2: Networking

Appendix C. Sample Networking Nodes to Target Networking Interactions

| Node | |

| Formal Structures for Networking | In Ireland, two types of network operate in relation to child and family services: Child and family support networks (CFSNs) support the provision of accessible and integrated supports for families by taking a localized, area based approach to coordinating services. A number of CFSNs can operate in any given geographical area depending on population density, levels of need, and service provision (exo level). Children and young people’s services committees (CYPSC’s) are responsible for securing better outcomes for children and young people in their area through more effective integration of existing services and interventions. Their age remit spans all children and young people aged from 0 to 24 years and there is one in every county in Ireland (exo level). |

| Children’s Participation Strategy | In line with the children’s participation strategy and training available relating to this, look for examples of where children and young people can work with individuals and teams to advocate and influence. |

| Organizational Data Sources | Tusla reports quarterly regional and national performance data. Keep up to date with trends in your region and use the data to support your networking practices. |

| Campaign Groups | Link in with relevant campaign groups to ask for assistance in raising issues like your observed impact of homelessness on families you work with, your evidence from practice regarding impact of poverty on school attendance; e.g. Children’s Rights Alliance, Barnardos, Irish Society for for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children (ISPCC). |

| Targeted Services | Find the most relevant organization that addresses the issues arising in your practice, such as local and national Traveller movements, Empowering People in Care (EPIC) relating to children in care and leaving care, Support groups in relation to asylum seekers and refugees |

| Interagency/multi-disciplinary training/learning opportunities. | Engage in any available opportunities to attend cross agency/multi-disciplinary learning or training events in your area. These can be face-to-face/online. Local third level institutions may provide open access seminars, conferences, and training events, and many national organizations (e.g. Barnardos) provide on-line training events. |

Appendix D. Guide for Practice Researchers Testing the Application of the Framework for Supervision and Practice Development (Adapted from Marthinsen E. and Julkunen, I, 2012 Practice Research in Nordic Social Work: Knowledge Production in Transition)

- “Practice research involves curiosity about practice” (Salisbury statement on practice research in Marthinsen and Julkunen (2012, p. 194)).

- Practice research is not a method in itself, it is an approach to research led by practitioners. It can involve a range of methods depending on the objective and planned outcome of the research.

- While a range of different methods of evaluation can be used, practice research tends to orient towards multi-methods, single case studies, analysis involving reflective and narrative interpretations, and ethnographies (see Julkunen 2012).

- Practice research can be through partnerships between universities and agencies; practitioner led research, and/or practitioner and service user partnership research.

- Practice research requires the same rigor as other forms of research but tends towards a more interactive and collaborative rather than a hierarchical model (see Julkunen 2012).

- The role of the researcher in practice research is similar to that of an academic researcher: As a change agent. The practice researcher tends towards reflections through evaluation and internal validation often involving peer learning and evaluation (see Julkunen 2012).

- Practice research lends itself well to service user involvement in the evaluation and testing of different approaches to practice.

- Practice research, according to Julkunen, 2012, brings forth a new conceptualization of evaluation which is interested in “recovering a sense of making and participating rather than just seeing and finding” (p. 112).

- A practice research approach can be built into supervision and practice development through agreeing a method of recording how the supervision tools are used (e.g., using a narrative method) and committing to evaluating the framework with regard to its applicability to practice skills development.

References

- Bartley, Allen, and Liz Beddoe. 2018. Transnational Social Work: Opportunities and Challenges of a Global Profession. Chicago: Chicago University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, Uri. 1992. Risk Society: Towards and New Modernity. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, Margaret. 1999. Working in Partnership in Child Protection: The Conflicts. The British Journal of Social Work 29: 437–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, Bernadine, Carmel Devaney, Rosemary Crosse, Leonor Rodriguez, and Charlotte Silke. 2020. The Strengths and Challenges of the YAP Community Based Advocate Model. Galway: UNESCO Child and Family Research Centre. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, Uri. 1979. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, Uri, and Stephen J. Ceci. 1994. Nature-Nuture Reconceptualized in Developmental Perspective: A Bioecological Model. Psychological Review 101: 568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, Uri, and Pamela A. Morris. 1998. The Ecology of Developmental Processes. In Handbook of Child Psychology, Vol. 1: Theoretical Models of Human Development, 5th ed. Edited by William Damon and Richard M. Lerner. New York: Wiley, pp. 993–1023. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, Uri, and Pamela A. Morris. 2006. The Bioecological Model of Human Development. In Handbook of Child Psychology, Vol. 1: Theoretical Models of Human Development, 6th ed. Edited by William Damon and Richard M. Lerner. New York: Wiley, pp. 793–828. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Kate. 2019. Vulnerability and Child Sexual Exploitation: Towards an Approach Grounded In Life Experiences. Critical Social Policy 39: 622–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, Helen. 2018. Editorial: Special Issue on Child Protection and Domestic Violence. Australian Social Work 71: 131–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, Helen, Nicola Carr, and Sadhbh Whelan. 2011. ‘Like walking on eggshells’: Service user views and expectations of the child protection system. Child and Family Social Work 16: 101–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, Sarah-Anne, and Caroline McGregor. 2019. Interrogating institutionalisation and child welfare: The Irish case, 1939–1991. European Journal of Social Work 22: 1062–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, Kenneth. 2011. ‘Career preference’, ‘transients’ and ‘converts’: A study of social workers’ retention in child protection and welfare’. British Journal of Social Work 41: 520–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, Kenneth, and McGregor Caroline. 2019. Child protection and welfare systems in Ireland: Continuities and discontinuities of the present. In National Systems of Child Protection: Understanding the International Variability and Context for Developing Policy and Practice. Edited by Lisa Merkel-Holguin, John D. Fluke and Richard Krugman. Dordrecht: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Bywaters, Paul, Geraldine Brady, Lisa Bunting, Brigid Daniel, Brid Featherstone, Chantel Jones, Kate Morris, John Scourfield, Tim Sparks, and Calum Webb. 2018. Inequalities in English child protection practice under austerity: A universal challenge? Child & Family Social Work 23: 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canavan, John, Carmel Devane, Caroline Mc Gregor, and Aileen Shaw. 2019. A Good Fit? Ireland’s Programme for Prevention, Partnership and Family Support as a Public Health Approach to Children Protection. In Re-Visioning Public Health Approaches for Protecting Children. Edited by Bob Lonne, Deb Scott, Daryl Higgins and Todd I. Herrenkohl. New York: Springer Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Connolly, Maria, and Ilan Katz. 2019. Typologies of Child Protection Systems: An International Approach. Child Abuse Review 28: 381–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, Nuala, and Carmel Devaney. 2018. Parenting Support: Policy and Practice in the Irish Context. Child Care in Practice 24: 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coogan, Declan. 2017. Child to Parent Violence and Abuse: Family Interventions with Non-Violent Resistance. London: Jessica Kingsley. [Google Scholar]

- Corby, Brian. 1998. Child Protection and Family Support. Tensions, Contradictions and Possibilities. Child and Family Social Work 3: 215–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulter, Carol. 2015. Final Report of the Child Care Law Reporting Project. Dublin: Child Care Law Reporting Project. [Google Scholar]

- Coulter, Carol. 2018. An Examination of Lengthy, Contested and Complex Child Protection Cases in the District Court. Dublin: Child Care Law Reporting Project. [Google Scholar]

- Daly, Mary, Rachel Bray, Zlata Bruckauf, Jasmina Byrne, Alice Margaria, Ninoslava Pećnik, and Maureen Samms-Vaughan. 2015. Family and Parenting Support: Policy and Provision in a Global Context. Florence: UNICEF Office of Research, Innocenti Insight. [Google Scholar]

- Daro, Deborah. 2016. Early Family Support Interventions: Creating Context for Success. Global Social Welfare 3: 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daro, Deborah. 2019. A Shift in Perspective: A Universal Approach to Child Protection. The Future of Children 29: 17–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devaney, Carmel. 2011. Family Support as an Approach to Working with Children and Families in Ireland. Germany: Lap Lambert Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Devaney, Carmel, and Pat Dolan. 2017. Voice and Meaning: The Wisdom of Family Support Veterans. Child & Family Social Work 22: 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devaney, Carmel. 2015. Enhancing Family Support in Practice through Postgraduate Education. Social Work Education 34: 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devaney, Carmel, and Caroline McGregor. 2017. Child protection and Family Support practice in Ireland: A contribution to present debates from a historical perspective. Child and Family Social Work 22: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devaney, Carmel. 2017. Promoting children’s welfare through Family Support. In The Routledge Handbook of Global Child Welfare. Edited by Pat Dolan and Frost Nick. London: Routledge, pp. 99–109. [Google Scholar]

- Devaney, Carmel, Caroline McGregor, and Lisa Moran. 2018. Outcomes for Permanence and Stability for Children in Care in Ireland: Implications for Practice. The British Journal of Social Work. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devaney, John. 2018. The Trouble with Thresholds: Rationing as A Rational Choice In Child And Family Social Work. Child and Family Social Work. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devaney, John, and Trevor Spratt. 2009. Child Abuse as a Complex and Wicked Problem: Reflecting on Policy Developments in the United Kingdom in Working with Children and Families with Multiple Problems. Children and Youth Services Review 31: 635–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolan, Pat, and Frost Nick, eds. 2017. The Routledge Handbook of Global Child Welfare. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Dolan, Pat, John Canavan, and John Pinkerton, eds. 2006. Family Support as Reflective Practice. London: Jessica Kingsley. [Google Scholar]

- Dolan, Pat, and McGregor Caroline. 2020. Social Support Empathy and Ecology: In J. Pearce Ed Child Sexual Exploitation Why Theory Matters. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Dunst, Carl J., Kimberly Boyd, Carol M. Trivette, and Deborah W. Hamby. 2002. Family-oriented program models and professional helpgiving practices. Family Relations 51: 221–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission Against Racism and Intolerance (ECRI). 2019. ECRI Report on Ireland: Fifth Monitoring Report. Strasbourg: Council of Europe. [Google Scholar]

- Fargion, Silvia. 2014. Synergies and Tensions in Child Protection and Parent Support: Policy lines and Practitioners Cultures. Child and Family Social Work 19: 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Featherstone, Brid, Anna Gupta, Kate Morris, and Sue White. 2018. Protecting Children: A Social Model. Bristol: Policy Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, Ian, Vasilios Ioakimidis, and Michael Lavlette. 2018. Global Social Work in a Political Context: Radical Perspectives. Bristol: Policy Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, Harry, Lisa Warwick, Tarsem Singh Cooner, Leigh Jadwiga, Liz Beddoe, Tom Disney, and Gillian Plumridge. 2020. The nature and culture of social work with children and families in long-term casework: Findings from a qualitative longitudinal study. Child and Family Social Work. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, Susan. 2020. Towards Parity in Protection: Barriers to Effective Child Protection and Welfare Assessment with Disabled Children in the Republic of Ireland. Child Care in Practice. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, Nick. 2017. “From “silo” to “network” profession—A multi-professional future for social work. Journal of Children’s Services 12: 174–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, Norah. 2010. Roscommon Child Care Case. Dublin: HSE. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, Neil, Nigel Parton, and Marit Skivenes. 2011. Child Protection Systems: International Trends and Orientations. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halton, Carmel, Gill Harold, Aileen Murphy, and Edel Walsh. 2018. A Social and Economic Analysis of the Use of Legal Services (SEALS) In the Child and Family Agency (Tusla). Cork: University College Cork. [Google Scholar]

- Hardiker, Pauline, Kenneth Exton, and Mary Barker. 1991. Policies and Practices in Preventive Child Care. Aldershot: Avebury. [Google Scholar]

- Harrikari, Timo, and Pirkko-Liisa Rauhala. 2019. Towards Glocal Social Work in the Era of Compressed Modernity. London & New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Herrera-Pastor, David, Juárez Jesús, and Cristóbal Ruiz-Román. 2019. Collaborative leadership to subvert marginalisation: The workings of a socio-educational network in Los Asperones, Spain. School Leadership & Management. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, Martyn. 2017. Child Protection Social Work in England: How Can It Be Reformed? The British Journal of Social Work 47: 293–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, Stephanie, Carolina Overlien, and John Devaney, eds. 2018. Responding to Domestic Violence Emerging Challenges for Policy, Practice and Research in Europe. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Houston, Stanley. 2019. Extending Bourdieu for Critical Social Work. In Routledge Handbook of Critical Social Work. Edited by Stephen Webb. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hyslop, Ian. 2018. Neoliberalism and social work identity. European Journal of Social Work 21: 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jack, Gordon. 2000. Ecological Influences of Parenting and Child Development. British Journal of Social Work 30: 703–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joy, Eileen, and Liz Beddoe. 2019. Aces, Cultural Considerations and ‘Common Sense’ In Aotearoa New Zealand. Social Policy and Society 18: 491–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julkunen, Ilse. 2012. Critical Elements in evaluating and developing practice in social work: An exploratory overview. In Practice Research in Nordic Social Work: Knowledge Production in Transition. Edited by Edgar Marthinsen and Isle Julkunen. London: Whiting and Birch, pp. 95–116. [Google Scholar]

- Kadushin, Charles. 2012. Understanding Social Networks: Theories, Concepts, and Findings. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Keddell, Emily. 2014. Theorising the signs of safety approach to child protection social work: Positioning, codes and power. Children and Youth Services Review 47: 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killion, Mary G. 2020. Family Focused Practices in Irish Mental Health. In Irish Social Worker. Dublin: Irish Association of Social Workers. [Google Scholar]

- Libesman, Terri. 2004. Child welfare approaches for Indigenous communities: International perspectives. Child Abuse Prevention Issues. Australian Institute of Family Studies 20: 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Liebenberg, Linda, and Daphne Hutt-Macleod. 2017. Community Development Programmes in Response to Neo-liberalism. In The Routledge Handbook of Global Child Welfare. Edited by Pat Dolan and Nick Frost. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Lonne, Bob, Deb Scott, Daryl Higgins, and Todd Herrenkoh, eds. 2019. Re-Visioning Public Health Approaches for Protecting Children. Cham: Springer International Publishing, Volume 9, ISBN 978-3-030-05857-9. [Google Scholar]

- Lotty, Maria, Audrey Dunn Galvin, and Eleanor Bantry White. 2020. Effectiveness of a trauma-informed care psychoeducational program for foster carers—Evaluation of the Fostering Connections Program. Child Abuse and Neglect. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mafile’o, Tracie. 2019. Social Work with Pacific Communities. In New Theories for Social Work Practice: Ethical Practices for Working with Individuals, Families and Communities. Edited by Robyn Munford and Kieran O’Donoghue. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers, pp. 212–30. [Google Scholar]

- Malone, Patrick, and John Canavan. 2018. Systems Change: Final Evaluation Report on Tusla’s Prevention, Partnership and Family Support Programme. Galway: UNESCO Child and Family Research Centre, National University of Ireland Galway. [Google Scholar]

- Malone, P., J. Canavan, C. Devaney, and C. Mc Gregor. 2018. Comparing areas of commonality and distinction between the national practice models of Meitheal and Signs of Safety. Galway: UNESCO Child and Family Research Centre. [Google Scholar]

- Marston, Greg, and Catherine McDonald. 2012. Getting Beyond ‘Heroic Agency’ in Conceptualising Social Workers as Policy Actors in the Twenty-First Century. The British Journal of Social Work 42: 1022–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marthinsen, Edgar. 2012. Social Work Practice and Social Science History. In Practice Research in Nordic Social Work: Knowledge Production in Transition. Edited by Edgar Marthinsen and Isle Julkunen. London: Whiting and Birch, pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Marthinsen, Edgar, and Isle Julkunen, eds. 2012. Practice Research in Nordic Social Work: Knowledge Production in Transition. London: Whiting and Birch. [Google Scholar]

- McCormack, Cheryl, Marie Gibbons, and McGregor Caroline. 2020. An Ecological Framework for Understanding and Improving Decision Making in Child Protection and Welfare Intake (Duty) Practices in the Republic of Ireland. Child Care in Practice. 26: 146–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGregor, Caroline. 2019. Paradigm Framework for social work in the 21st century. The British Journal of Social Work 49: 2112–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGregor, Caroline. 2016. Balancing Regulation and Support in Child Protection: Using Theories of Power to Develop Reflective Tools for Practice. In Irish Social Worker. Dublin: Irish Association of Social Workers, pp. 11–16. [Google Scholar]

- McGregor, Caroline, and Carmel Devaney. 2020. Protective support and supportive protection for families “in the middle”: Learning from the Irish context. Child & Family Social Work 25: 277–85. [Google Scholar]

- McGregor, Caroline, and Saoirse Nic Gabhainn. 2018. Public Awareness. Galway: UNESCO Child and Family Research Centre, National University of Ireland Galway. [Google Scholar]

- McGregor, Caroline, John Canavan, and Patricia O’Connor. 2018. Public Awareness Work Package Final Report: Tusla’s Programme for Prevention, Partnership and Family Support. Galway: UNESCO Child and Family Research Centre, National University of Ireland Galway. [Google Scholar]

- Mc Guinness, Catherine. 1993. Report of the Kilkenny Incest Investigation; Dublin: Government Publications Stationery Office.

- McAlinden, Anne-Marie. 2012. ‘Grooming’ and the Sexual Abuse of Children: Institutional, Internet, and Familial Dimensions. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- McCafferty, Paul, and Brian Taylor. 2020. Risk, Decision-making and Assessment in Child Welfare. Child Care in Practice 26: 107–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPherson, Lynn, and Noel MacNamara. 2017. Supervising Child Protection Practice: What Works? Cham: Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Merkel-Holguin, Lisa, John. D. Fluke, and Richard. D. Krugman, eds. 2019. National Systems of Child Protection: Understanding the International Variability and Context for Developing Policy and Practice. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Mooney, Joe. 2018. Adult Disclosures of Childhood Sexual Abuse and Section 3 of the Child Care Act 1991: Past Offences, Current Risk. Child Care in Practice 24: 245–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, Kate, Will Mason, Paul Bywaters, Brid Featherstone, Brigit Daniel, Geraldine Brady, and Calum Webb. 2018. Social Work, Poverty, and Child Welfare Interventions. Child & Family Social Work 23: 364–72. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, Tony. 2010. The Strategic Leadership of Complex Practice: Opportunities and Challenges. Child Abuse Review 19: 312–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munford, Robyn, and Kieran O’Donoghue. 2019. New Theories for Social Work Practice: Ethical Practices for Working with Individuals, Families and Communities. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers, pp. 212–30. [Google Scholar]

- Munro, Eileen. 2011. The Munro Review of Child Protection: Final Report. A Child-Centred System. London: Department of Education. [Google Scholar]

- Ní Raghallaigh, Muireann. 2018. The integration of asylum seeking and refugee children: Resilience in the face of adversity. In Research Handbook on Child Migration. Edited by Jacqueline Bhabha, Jyothi Kanics and Daniel Senovilla Hernández. Elgar: Cheltenham, pp. 351–87. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor, Patricia, Caroline McGregor, and Carmel Devaney. 2018. Newspaper Content Analysis: Print Media Coverage of Ireland’s Child and Family Agency (Tusla) 2014–2017. Galway: The UNESCO Child and Family Research Centre, National University of Ireland Galway. [Google Scholar]

- O’Donoghue, Kirean. 2019. Supervision and Evidence Informed Practice. In New Theories for Social Work Practice: Ethical Practices for Working with Individuals, Families and Communities. Edited by Robyn Munford and K. O’Donoghue. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers, pp. 271–88. [Google Scholar]

- Overlien, Carolina, and Stephanie Holt. 2019. Editorial: European Research on Children, Adolescents and Domestic Violence: Impact, Interventions and Innovations. Journal of Family Violence 34: 365–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parton, Nigel. 1991. Governing the Family. London: MacMillan. [Google Scholar]

- Parton, Nigel. 1997. Child protection and family support: Current debates and future prospects. In Child Protection and Family Support: Tensions, Contradictions and Possibilities. Edited by Nigel Parton. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Parton, Nigel. 2014. Social Work, Child Protection and Politics: Some Critical and Constructive Reflections. British Journal of Social Work 44: 2042–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parton, Nigel, ed. 2015a. Contemporary Developments in Child Protection. Vol 1 Policy Changes and Challenges. Basel: MDPI. [Google Scholar]

- Parton, Nigel, ed. 2015b. Contemporary Developments in Child Protection. Vol 2 Issues in Child Welfare. Basel: MDPI. [Google Scholar]

- Parton, Nigel, ed. 2015c. Contemporary Developments in Child Protection. Vol 3 Broadening Challenges in Child Protection. Basel: MDPI. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, Jenny. 2019. Child Sexual Exploitation: Why Theory Matters. Bristol: Policy Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pinkerton, John, Canavan John, and P. Dolan. 2019. Family Support and Social Work Practice. In New Theories for Social Work Practice: Ethical Practice for Working with Individuals, Families and Communities. Edited by R. Munford and K. O’Donoghue. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishing, pp. 44–62. [Google Scholar]

- Philp, Mark. 1979. Notes on the Forms of Knowledge in Social Work. Sociological Review 27: 83–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, Tove. 2012. Knowledge production and social work: Forming knowledge production. In Practice Research in Nordic Social Work: Knowledge Production in Transition. Edited by Edgar Marthinsen and Isle Julkunen. London: Whiting and Birch, pp. 43–66. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez, L., A. Cassidy, and C. Devaney. 2018. Meitheal Process and Outcomes Study. Galway: UNESCO Child and Family Research Centre, National University of Ireland Galway. [Google Scholar]

- Ruch, Gillian, Karen Winter, Viv Cree, Sophie Hallet, Fiona Morrisson, and Mark Hadfield. 2017. Making meaningful connections: Using insights from social pedagogy in statutory child and family social work practice. Child and Family Social Work 22: 1015–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapouna, Lydia. 2020. Service-user narratives in social work education; Co-production or co-option? Social Work Education. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satka, Mirja. 2020. Pragmatist knowledge production in practice research. In The Routledge Handbook of Social Work Practice Research. Edited by Lynette Joubert and Martin Webber. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Sharkey, Peter. 1989. Social Networks and Social Service Workers. The British Journal of Social Work 19: 387–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shemmings, David, and Yvonne Shemmings. 2011. Understanding Disorganized Attachment: Theory and Practice for Working with Children and Adults. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Slettebø, Tor. 2013. Partnership with Parents of Children in Care: A Study of Collective User Participation in Child Protection Services. The British Journal of Social Work 43: 579–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skehill, Caroline. 2004. History of the Present of Child Protection and Welfare Social Work in Ireland. Lapmeter: Edwin Mellen. [Google Scholar]

- Spratt, Trevor, John Devaney, and John Frederick. 2019. Adverse Childhood Experiences: Beyond Signs of Safety; Reimagining the Organisation and Practice of Social Work with Children and Families. British Journal of Social Work 49: 2042–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, Denise, Rosemary Littlechild, Joe Duffy, and David Hayes. 2017. ‘Making It Real’: Evaluating the Impact of Service User and Carer Involvement in Social Work Education. British Journal of Social Work 47: 467–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tierney, Edel, Danielle Kennan, Cormac Forkan, Bernadine Brady, and Rebecca Jackson. 2018. Children’s Participation Work Package Final Report: Tusla’s Programme for Prevention, Partnership and Family Support. Galway: UNESCO Child and Family Research Centre, National University of Ireland Galway. [Google Scholar]

- Timms, Elizabeth. 1990. Social Networks and Social Service Workers: A Comment on Sharkey. The British Journal of Social Work 20: 627–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tudge, Johnathan, Irina Mokrova, Bridget E. Hatfield, and Rachana B. Karnik. 2009. Uses and Misuses of Bronfenbrenner’s Bioecological Theory of Human Development. Journal of Family Theory & Review 1: 198–210. [Google Scholar]

- Turba, Hannu, Janne Paulsen Breimo, and Christian Lo. 2019. Professional and Organizational Power Intwined: Barriers to Networking? Children and Youth Services Review. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnell, Andrew, and Terry Murphy. 2017. Signs of Safety Comprehensive Briefing Paper, 4th ed. Perth: Resolutions Consultancy Pty Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Tusla. 2019. Third Quarterly Performance Data Report. Dublin: Tusla. [Google Scholar]

- Tusla. 2020. Available online: www.tusla.ie (accessed on 30 March 2020).

- Uggerhoj, Lars. 2012. Theorising practice research in social work. In Practice Research in Nordic Social Work: Knowledge Production in Transition. Edited by Edgar Marthinsen and Isle Julkunen. London: Whiting and Birch, pp. 67–94. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins, David. 2012. Disorganised attachment indicates child maltreatment: How is this link useful for child protection social workers? Journal of Social Work Practice 26: 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, David, and Donald Forrester. 2020. Predicting the Future in Child and Family Social Work: Theoretical, Ethical and Methodological Issues for a Proposed Research Programme. Child Care in Practice 26: 196–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, Karen, and Viviene E. Cree. 2016. Social Work Home Visits to Children and Families in the UK: A Foucaldian Perspective. British Journal of Social Work 46: 1175–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

McGregor, C.; Devaney, C. A Framework to Inform Protective Support and Supportive Protection in Child Protection and Welfare Practice and Supervision. Soc. Sci. 2020, 9, 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9040043

McGregor C, Devaney C. A Framework to Inform Protective Support and Supportive Protection in Child Protection and Welfare Practice and Supervision. Social Sciences. 2020; 9(4):43. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9040043

Chicago/Turabian StyleMcGregor, Caroline, and Carmel Devaney. 2020. "A Framework to Inform Protective Support and Supportive Protection in Child Protection and Welfare Practice and Supervision" Social Sciences 9, no. 4: 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9040043

APA StyleMcGregor, C., & Devaney, C. (2020). A Framework to Inform Protective Support and Supportive Protection in Child Protection and Welfare Practice and Supervision. Social Sciences, 9(4), 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9040043