Understanding Motivations for Volunteering in Food Insecurity and Food Upcycling Projects

Abstract

1. Introduction

Overview of the Literature on Social Enterprises and Volunteering

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

2.2. Survey Questionnaire

2.3. Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Profile and Recruitment of Volunteers

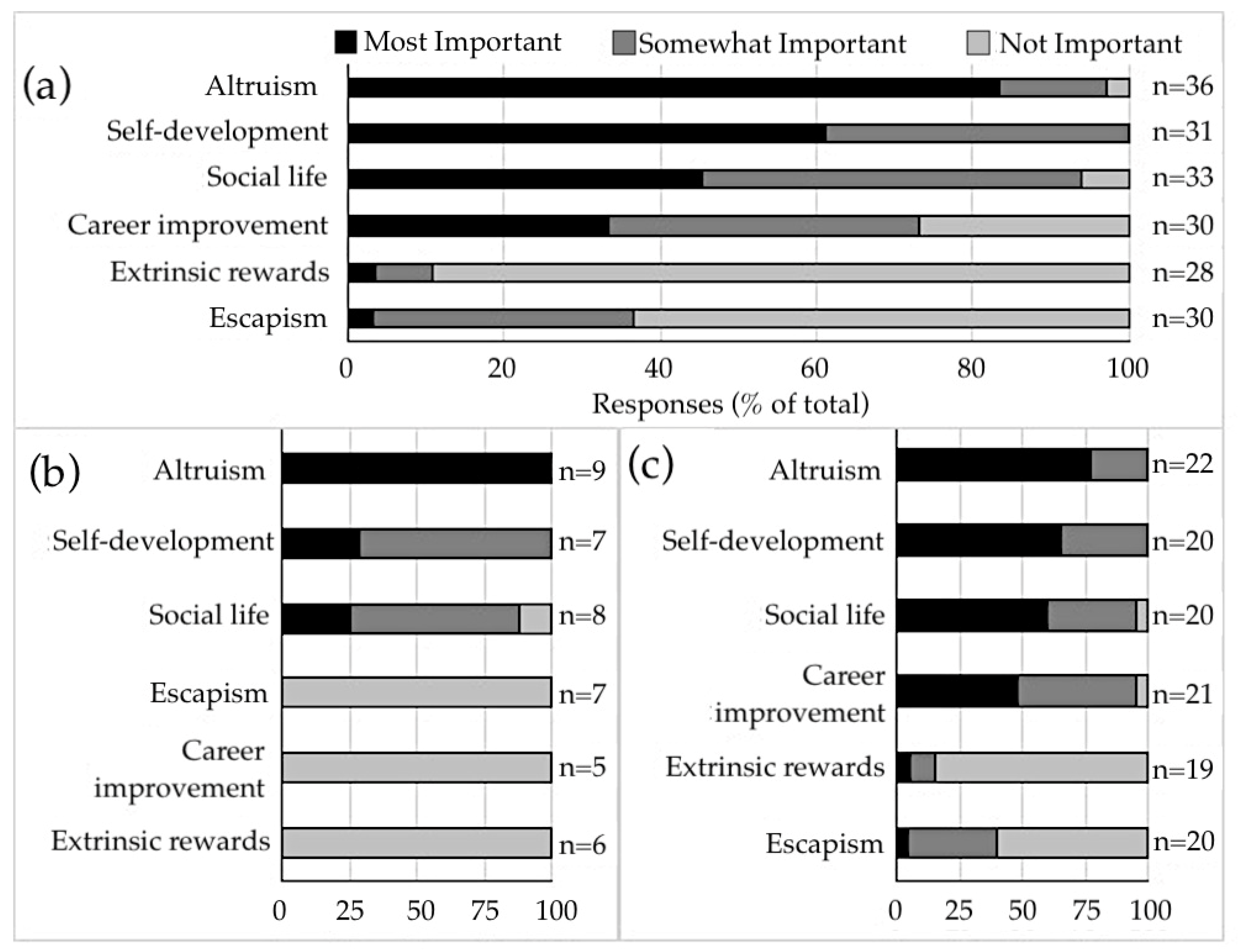

3.2. Motivations of Volunteers

- (1)

- Altruism: I wish to give my time to help other members of my community;

- (2)

- Self-development: Volunteering is a good way to learn through direct hands-on experience and develop my skills;

- (3)

- Social life: Volunteering benefits my social life (e.g., by meeting new people, being with my friends);

- (4)

- Career improvement: Volunteering can improve my career (e.g., get experience, make new contacts, improve my resume);

- (5)

- Escapism: Volunteering is a good escape from my problems;

- (6)

- Extrinsic rewards: I’m volunteering to fulfill obligation through school, a service requirement or to increase my chance to gain an award, certificate, scholarship or accreditation.

- Personal beliefs in the cause and shared values with the project (n = 7)

- A strong interest in food policy and/or combatting food insecurity (n = 5)

- Recognizing food insecurity as a major societal issue (n = 2)

- Good fit for the volunteers’ lifestyle (n = 1)

- Having personally observed food insecurity (n = 1)

3.3. Benefits for the Volunteers

- Teamwork and collaboration (n = 5)

- Communication (n = 4)

- Self-confidence (n = 3)

- Socialization (n = 3)

- Open-mindedness (n = 3)

- Awareness towards food insecurity issues (n = 2)

- Experience working with the public (n = 2)

- Leadership (n = 1)

- Organization and time management (n = 1)

“Interpersonal skills are something that you constantly are working on and improving. Volunteering with The SEED helped especially with communication as you had to explain what the company was doing many times.”

“My personal life and work life do not require a lot of collaboration. Volunteering with The SEED has been a good supplement to developing many skills related with working with other people to accomplish a common goal.”

“I needed to get back into the community and talk with people. Volunteering has helped me to become better socialized after a period of isolation.”

3.4. Interest of the Volunteers in a Future Project Related to Upcycled Food Products

“I think that is a fantastic way to help educate people on how to get the most value out of their food. Additionally, preservation methods can be pretty cheap and affordable, and extend the life of a lot of our food.”

“I see food waste as being a major problem within the community and would like to assist in ensuring that more of the food we produce is being consumed. If this can be done in a way that also enhances the livelihoods of youth then I am even more on board. I also love to cook and have some experience in canning, so the program fits my interests.”

“I have a history of working in a kitchen, and enjoy taking a ‘rescue’ vegetable home and seeing what can be done with it. I would enjoy the creative element of the upcycle kitchen to see what can be salvaged from donated produce, and how many recipes could be involved. Teamwork to enhance that creativity, and to show others who are less familiar with kitchen skills how to maximize a food item’s value, could be a self-confidence boost as well as an important collaboration to strengthen the work of the program.”

3.5. Retention of Volunteers

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions and Implications

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahn, SangNam, Karon L. Philips, Matthew Lee Smith, and Marcia G. Ory. 2011. Correlates of Volunteering among Aging Texans: The Roles of Health Indicators, Spirituality, and Social Engagement. Maturitas 69: 257–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, Joseph Andrew, and Stephanie L. Mueller. 2013. The Revolving Door: A Closer Look at Major Factors in Volunteers’ Intention to Quit. Journal of Community Psychology 41: 139–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvord, Sarah H., L. David Brown, and Christine W. Letts. 2004. Social Entrepreneurship and Societal Transformation: An Exploratory Study. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science 40: 260–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anseel, Frederik, Filip Lievens, Eveline Schollaert, and Beata Choragwicka. 2010. Response Rates in Organizational Science, 1995-2008: A Meta-analytic Review and Guidelines for Survey Researchers. Journal of Business and Psychology 25: 335–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, James, Howard Stevenson, and Jane Wei-Skillern. 2003. Social Entrepreneurship and Commercial Entrepreneurship: Same, Different, or Both? Working Paper Series, No. 04-029; Boston: Harvard Business School. [Google Scholar]

- Bacq, Sophie, and Frank Janssen. 2011. The Multiple Faces of Social Entrepreneurship: A Review of Definitional Issues Based on Geographical and Thematic Criteria. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 23: 373–403. [Google Scholar]

- Bane, K. Denise. 1999. Effects of Type of Voice on Perceptions of Fairness in Performance Evaluation. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality 14: 75–88. [Google Scholar]

- Bang, Hyejin, and Stephen D. Ross. 2009. Volunteer Motivation and Satisfaction. Journal of Venue and Event Management 1: 61–77. [Google Scholar]

- Bedore, Melanie. 2018. “I was purchasing it; it wasn’t given to me”: Food Project Patronage and the Geography of Dignity Work. Geographical Journal 184: 218–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berno, Tracy. 2017. Social Enterprise, Sustainability and Community in Post-Earthquake Christchurch: Exploring the Role of Local Food Systems in Building Resilience. Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy 11: 149–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, Siddharth, Jeonggyu Lee, Jonathan Deutsch, Hasan Ayaz, Benjamin Fulton, and Rajneesh Suri. 2018. From Food Waste to Value-Added Surplus Products (VASP): Consumer Acceptance of a Novel Food Product Category. Journal of Consumer Behaviour 17: 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bierma, Thomas J., Guang Jin Guang, and Christy N. Bazan. 2019. Food Donation and Food Safety: Challenges, Current Practices, and the Road Ahead. Journal of Environmental Health 81: 16–21. [Google Scholar]

- Booth, Sue, Christina Pollard, John Coveney, and Ian Goodwin-Smith. 2018. ‘Sustainable’ Rather Than ‘Subsistence’ Food Assistance Solutions to Food Insecurity: South Australian recipients’ perspectives on traditional and social enterprise models. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15: 2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brayley, Nadine, Patricia Obst, Katherine M. White, Ioni M. Lewis, Jeni Warburton, and Nancy M. Spencer. 2013. Exploring the Validity and Predictive Power of an Extended Volunteer Functions Inventory within the Context of Episodic Skilled Volunteering by Retirees. Journal of Community Psychology 42: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewis, Georgina, Jennifer Russell, and Clare Holdsworth. 2010. Bursting the Bubble: Students, Volunteering and the Community. Available online: https://www.publicengagement.ac.uk/sites/default/files/publication/bursting_the_bubble_summary_report.pdf (accessed on 14 January 2020).

- Bussell, Helen, and Deborah Forbes. 2006. Understanding the Volunteer Market: The What, Where, Who and Why of Volunteering. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing 7: 244–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caraher, Martin, and Sinéad Furey. 2017. Is it Appropriate to Use Surplus Food to Feed People in Hunger? Short-Term Band-aid to More Deep-Rooted Problems of Poverty. London: Food Research Collaboration, Centre for Food Policy. [Google Scholar]

- Chapnick, Melissa, Ellen Barnidge, Marjorie Sawicki, and Michael Elliott. 2019. Healthy Options in Food Pantries-A Qualitative Analysis of Factors Affecting the Provision of Healthy Food Items in St. Louis, Missouri. Journal of Hunger & Environmental Nutrition 14: 262–80. [Google Scholar]

- Clary, E. Gill, Mark Snyder, and Robert Ridge. 1992. Volunteers’ Motivations: A Functional Strategy for the Recruitment, Placement, and Retention of Volunteers. Nonprofit Management and Leadership 2: 333–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clary, E. Gill, Mark Snyder, Robert D. Ridge, John Copeland, Arthus A. Stukas, Julie Haugen, and Peter Miene. 1998. Understanding and Assessing the Motivations of Volunteers: A Functional Approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 74: 1516–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Community Literacy of Ontario. 2005. Literacy Volunteers Value Added Research Report. Available online: http://www.communityliteracyofontario.ca/wp/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/volnteer.pdf (accessed on 14 January 2020).

- Corporation for National & Community Service. 2012. Skills Based Volunteering. Available online: https://www.nationalservice.gov/resources/member-and-volunteer-development/sbv (accessed on 10 January 2020).

- de Cremer, David, Ilse Cornelis, and Alain Van Hiel. 2008. To Whom Does Voice in Groups Matter? Effects of Voice on Affect and Procedural Fairness Judgments as a Function of Social Dominance Orientation. The Journal of Social Psychology 148: 61–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dees, Gregory J. 1998. The Meaning of “Social Entrepreneurship”. Kansas City: Kauffman Foundation and Stanford University. Available online: https://community-wealth.org/content/meaning-social-entrepreneurship (accessed on 13 January 2020).

- Demir, Filiz Otay, Ayşe Nil Kireçci, and Şenay Yavuz Görkem. 2019. Deepening Knowledge on Volunteers Using a Marketing Perspective: Segmenting Turkish Volunteers According to Their Motivations. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 27: 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, Mary Kate, Edward T. Scanlon, and Alicia M. Sellon. 2017. It’s a Generosity Loop’: Religious and Spiritual Motivations of Volunteers Who Glean Produce to Reduce Food Insecurity. Journal of Religion & Spirituality in Social Work: Social Thought 36: 456–78. [Google Scholar]

- Dimitri, Carolyn, Lydia Oberholtzer, and Andy Pressman. 2016. Urban Agriculture: Connecting Producers with Consumers. British Food Journal 118: 603–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, David, Hugh Campbell, and Anne Murcott. 2012. A Brief Pre-History of Food Waste and the Social Sciences. Sociological Review 60: 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, Robert J., and David Ackerman. 1998. The Effect of Recognition and Group Need on Volunteerism: A Social Norm Perspective. Journal of Consumer Research 25: 262–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabbey, Amber Erickson. 2017. Tailor Recognition to Volunteer Needs. The Volunteer Management Report 22: 4. [Google Scholar]

- Gooch, Martin, Delia Bucknell, Dan LaPlain, Benjamin Dent, Peter Whitehead, Abdel Felfel, Lori Nikkel, and Madison Maguire. 2019. The Avoidable Crisis of Food Waste: Technical Report. Value Chain Management International and Second Harvest, Ontario, Canada. Available online: https://secondharvest.ca/research/the-avoidable-crisis-of-food-waste/ (accessed on 14 January 2020).

- Gordon, Katy, Juliett Wilson, Andrea Tonner, and Eleanor Shaw. 2018. How Can Social Enterprises Impact Health and Well-Being? International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior and Research 24: 697–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Ontario. 2013. Impact: A Social Enterprise Strategy for Ontario. Available online: https://www.ontario.ca/page/impact-social-enterprise-strategy-ontario (accessed on 10 January 2020).

- Hall, Michael, Alison Andrukow, Cathy Barr, Kathy Brock, Margaret de Wit, Don Embuldeniya, Louis Jolin, David Lasby, Benoît Lévesque, Eli Malinsky, and et al. 2003. The Capacity to Serve—A Qualitative Study of the Challenges Facing Canada’s Non-profit and Voluntary Organizations. Ottawa: Canadian Centre for Philanthropy (CCP). Available online: http://sectorsource.ca/sites/default/files/resources/files/capacity_to_serve_english.pdf (accessed on 17 February 2020).

- Hecht, Amelie, and Roni A. Neff. 2019. Food Rescue Intervention Evaluations: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 11: 6781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hibbert, Sally, Maria Piacentini, and Haya Al Dajani. 2003. Understanding Volunteer Motivation for Participation in a Community-based Food Cooperative. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing 8: 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, Stevan. 1989. Conservation of Resources. A New Attempt at Conceptualizing Stress. The American Psychologist 44: 513–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holweg, Christina, and Eva Lienbacher. 2011. Social Marketing Innovation: New Thinking in Retailing. Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing 23: 307–26. [Google Scholar]

- Hoyos, Angela, and Diego F. Angel-Urdinola. 2019. Assessing International Organizations’ Support to Social Enterprise. Development Policy Review 37: O213–O229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hustinx, Lesley, and Els de Waele. 2015. Managing Hybridity in a Changing Welfare Mix: Everyday Practices in an Entrepreneurial Nonprofit in Belgium. Voluntas 26: 1666–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laufenberg, Günther, Benno Kunz, and Marianne Nystroem. 2003. Transformation of Vegetable Waste into Value Added Products: (A) The Upgrading Concept; (B) Practical Implementation. Bioresource Technology 87: 167–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luke, Belinda G., and Vien Chu. 2013. Social Enterprise versus Social Entrepreneurship: An Examination of the ‘Why’ and ‘How’ in Pursuing Social Change. International Small Business Journal 31: 764–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lysaght, Rosemary, Klara Jakobsen, and Birgit Granhaug. 2012. Social Firms: A Means for Building Employment Skills and Community Integration. Work 41: 455–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, Fiona H., Kehla Lippi, Matthew Dunn, Bronte C. Haines, and Rebecca Lindberg. 2018. Food-Based Social Enterprises and Asylum Seekers: The Food Justice Truck. Nutrients 10: 756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirosa, Miranda, Louise Mainvil, Hayley Horne, and Ella Mangan-Walker. 2016. The Social Value of Rescuing Food, Nourishing Communities. British Food Journal 118: 3044–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrow-Howell, Nancy, and Ada C. Mui. 2008. Elderly Volunteers: Reasons for Initiating and Terminating Service. Journal of Gerontological Social Work 13: 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousa, Tamara Y., and Jeanne H. Freeland-Graves. 2017a. Motivations for Volunteers in Food Rescue Nutrition. Public Health 149: 113–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousa, Tamara Y., and Jeanne H. Freeland-Graves. 2017b. Organizations of Food Redistribution and Rescue. Public Health 152: 117–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoz, Sarah-Anne, Jane Farmer, Rachel Winterton, and Jo Barraket. 2015. The Social Enterprise as a Space of Well-Being: An Exploratory Case Study. Social Enterprise Journal 11: 281–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikkel, Lori, Madison Maguire, Martin Gooch, Delia Bucknell, Dan LaPlain, Benjamin Dent, Peter Whitehead, and Abdel Felfel. 2019. The Avoidable Crisis of Food Waste: Roadmap; Second Harvest and Value Chain Management International; Ontario, Canada. Available online: www.SecondHarvest.ca/Research (accessed on 13 February 2020).

- O’Donnell, Thomas H., Jonathan Deutsch, Cathy Yungmann, Alexandra Zeitz, and Soloman H. Katz. 2015. New Sustainable Market Opportunities for Surplus Food: A Food System-Sensitive Methodology (FSSM). Food and Nutrition Sciences 6: 883–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otten, Jennifer J., Sara Diedrich, Katherine Getts, and Christine Benson. 2018. Commercial and Anti-Hunger Sector Views on Local Government Strategies for Helping Manage Food Waste. Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development 8: 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paget, Ally. 2015. Community Supermarkets Could Offer a Sustainable Solution to Food Poverty…. London: British Aisles. Available online: https://www.demos.co.uk/files/476_1501_BA_body_web_2.pdf?1427295281 (accessed on 17 February 2020).

- Phillips, Laura C., and Mark. H. Phillips. 2010. Volunteer Motivation and Reward Preference: An Empirical Study of Volunteerism in a Large, Not-for-Profit Organization. SAM Advanced Management Journal 75: 12–39. [Google Scholar]

- Popielarski, Jo Anna, and Nancy Cotugna. 2010. Fighting Hunger through Innovation: Evaluation of a Food Bank’s Social Enterprise Venture. Journal of Hunger and Environmental Nutrition 5: 56–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. 2016. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.r-project.org/.R (accessed on 17 February 2020).

- ReFED. 2016. A Roadmap to Reduce U.S. Food Waste by 20 Percent. Available online: https://www.refed.com/downloads/ReFED_Report_2016.pdf (accessed on 17 February 2020).

- Reynolds, Christian, John Piantadosi, and John Boland. 2015. Rescuing Food from the Organics Waste Stream to Feed the Food Insecure: An Economic and Environmental Assessment of Australian Food Rescue Operations Using Environmentally Extended Waste Input-Output Analysis. Sustainability 7: 4707–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riches, Graham. 2018. Food Bank Nations: Poverty, Corporate Charity and the Right to Food. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, Michael J., Cam Donaldson, Rachel Baker, and Susan Kerr. 2014. The Potential of Social Enterprise to Enhance Health and Well-Being: A Model and Systematic Review. Social Science & Medicine 123: 182–93. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, Michael J., Rachel Baker, and Susan Kerr. 2017. Conceptualising the Public Health Role of Actors Operating Outside of Formal Health Systems: The Case of Social Enterprise. Social Science & Medicine 172: 144–52. [Google Scholar]

- Sagawa, Shirley, and Eli Segal. 2000. Common Interest, Common Good: Creating Value Through Business and Social Sector Partnership. California Management Review 42: 105–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedlmeier, Regina, Meike Rombach, and Vera Bitsch. 2019. Making Food Rescue Your Business: Case Studies in Germany. Sustainability 11: 5101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, Maire. 2015. Volunteering in Canada, 2004 to 2013. Statistics Canada. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/89-652-x/89-652-x2015003-eng.htm (accessed on 14 January 2020).

- Staicu, Daniela. 2018. Financial Sustainability of Social Enterprise in Central and Eastern Europe. Processings of the International Conference on Business Excellence 12: 907–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarasuk, Valerie, Andy Mitchell, and Naomi Dachner. 2016. Household Food Insecurity in Canada, 2014; Toronto: Research to Identify Policy Options to Reduce Food Insecurity (PROOF). Available online: https://proof.utoronto.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Household-Food-Insecurity-in-Canada-2014.pdf (accessed on 14 January 2020).

- Vecina, María L., and Daniela Marzana. 2019. Motivations for Volunteering: Do Motivation Questionnaires Measure What Actually Drives Volunteers? Testing, Psychometrics, Methodology in Applied Psychology 26: 573–87. [Google Scholar]

- Warburton, Jeni, and Rachel Winterton. 2017. A far greater sense of community: The impact of volunteer behaviour on the wellness of rural older Australians. Health & Place 48: 132–38. [Google Scholar]

- Warburton, Jeni, Melanie Oppenheimer, and Gianna Zappalà. 2004. Marginalizing Australia’s Volunteers: The Need for Socially Inclusive Practices in the Non-Profit Sector. Australian Journal on Volunteering 9: 33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Wills, Benjamin. 2017. Eating at the limits: Barriers to the Emergence of Social Enterprise Initiatives in the Australian Emergency Food Relief Sector. Food Policy 70: 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, John. 2012. Volunteerism Research: A Review Essay. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 41: 176–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Joseph T., Wing Lo, and Elaine S. C. Liu. 2009. Psychometric Properties of the Volunteer Functions Inventory with Chinese Students. Journal of Community Psychology 37: 769–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanagisawa, Hisayo, and Hisatak Sakakibara. 2008. Factors Affecting Satisfaction Levels of Japanese Volunteers in Meal Delivery Services for the Elderly. Public Health Nursing 25: 471–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeung, Anne Birgitte. 2004. The Octagon Model of Volunteer Motivation: Results of a Phenomenological Analysis. International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 15: 21–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zappalà, G. 2001. From ‘Charity’ to ‘Social Enterprise’: Managing Volunteers in Public-Serving Nonprofits. Australian Journal on Volunteering 6: 41–49. [Google Scholar]

| Variables | Number of Respondents n (%) |

|---|---|

| Main occupation | |

| College or university student | 12 (32.4) |

| Employed for wages or self-employed | 10 (27.0) |

| Retired | 9 (24.3) |

| Out of work | 2 (5.4) |

| Family caregiver or homemaker | 1 (2.7) |

| High school student | 0 (0.0) |

| Other | 3 (8.1) |

| Involvement status | |

| Current volunteer/regular basis | 21 (56.7) |

| Current volunteer/intermittent events | 11 (29.7) |

| Former volunteer | 5 (13.5) |

| Duration of involvement | |

| More than one year | 13 (35.1) |

| Six months to one year | 14 (37.8) |

| Less than 6 months | 10 (27.0) |

| Frequency of volunteering activities | |

| Once per week | 20 (54.1) |

| Once or twice per month | 6 (16.2) |

| Less than once per month | 11 (29.7) |

| Mode of recruitment | |

| Family of friends involved with The SEED | 12 (32.4) |

| Website or social media | 9 (24.3) |

| Through partnership with another organization | 12 (32.4) |

| Customer or recipient of the services offered by The SEED | 3 (8.1) |

| Flyers/info pamphlets | 1 (2.7) |

| Personal Skill and Experiences | Number of Respondents n (%) |

|---|---|

| Enjoying working with the public | 33 (89.2) |

| Ability to cook | 32 (86.5) |

| Good planning and time management skills | 30 (81.1) |

| Experience working in customer service | 30 (81.1) |

| Experience in employee training | 27 (73.0) |

| Enjoying working on their feet and staying active | 27 (73.0) |

| Strong leadership skills | 24 (64.9) |

| Have, or have had, a first aid certification | 19 (51.4) |

| Experience working in an industrial or commercial kitchen | 18 (48.6) |

| Have, or have had, a Safe Food Handler’s certificate | 18 (48.6) |

| Experience driving a truck | 6 (16.2) |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rondeau, S.; Stricker, S.M.; Kozachenko, C.; Parizeau, K. Understanding Motivations for Volunteering in Food Insecurity and Food Upcycling Projects. Soc. Sci. 2020, 9, 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9030027

Rondeau S, Stricker SM, Kozachenko C, Parizeau K. Understanding Motivations for Volunteering in Food Insecurity and Food Upcycling Projects. Social Sciences. 2020; 9(3):27. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9030027

Chicago/Turabian StyleRondeau, Sabrina, Sara M. Stricker, Chantel Kozachenko, and Kate Parizeau. 2020. "Understanding Motivations for Volunteering in Food Insecurity and Food Upcycling Projects" Social Sciences 9, no. 3: 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9030027

APA StyleRondeau, S., Stricker, S. M., Kozachenko, C., & Parizeau, K. (2020). Understanding Motivations for Volunteering in Food Insecurity and Food Upcycling Projects. Social Sciences, 9(3), 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9030027