Rethinking Women’s Empowerment: Insights from the Russian Arctic

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Methods

2.1. Literature Review

2.2. Data Sources and Methods

3. Findings

3.1. Gender Disparities in Modern Russia’s Politics: The Higher the Stakes, the Deeper the Gap

“No Room for Women in Big Politics”

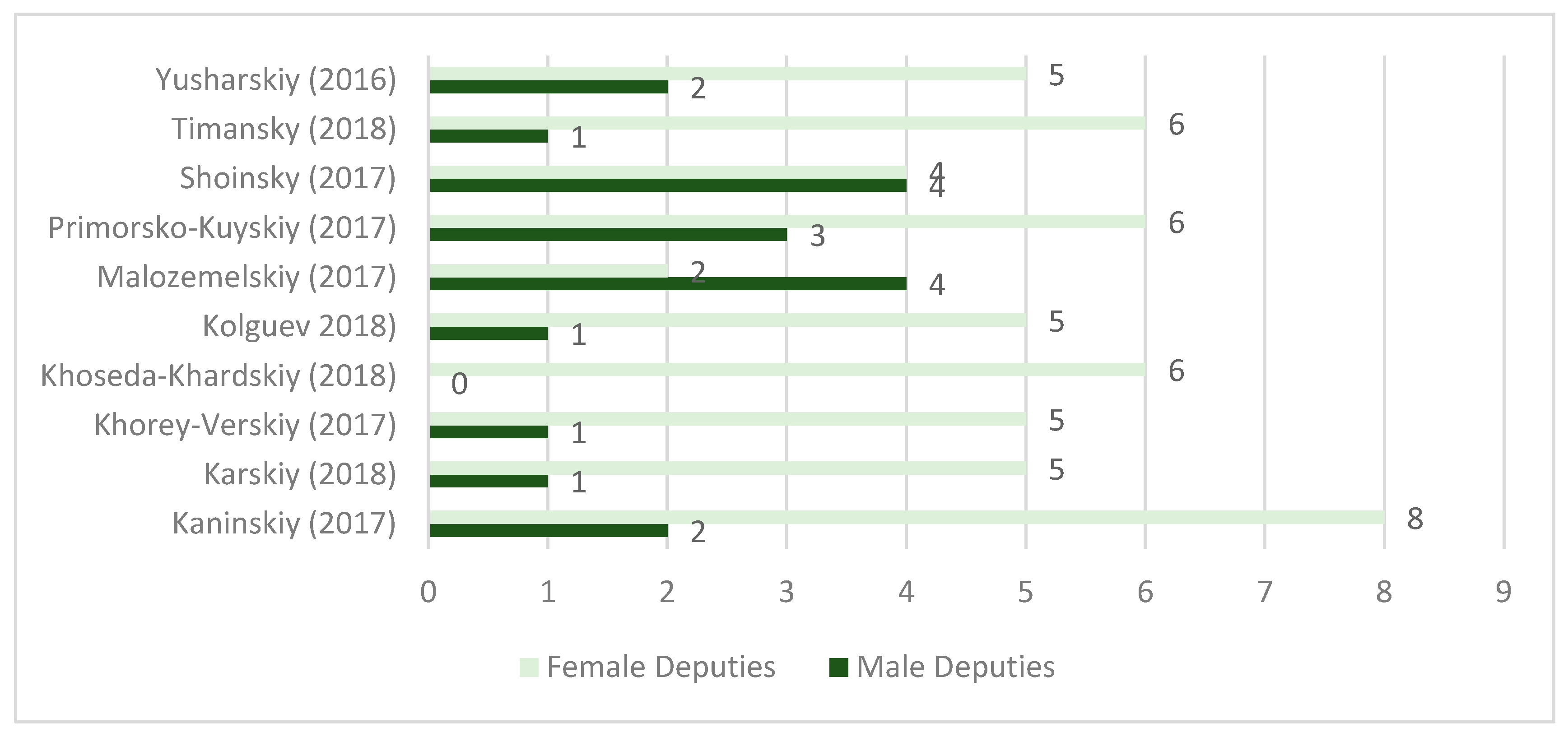

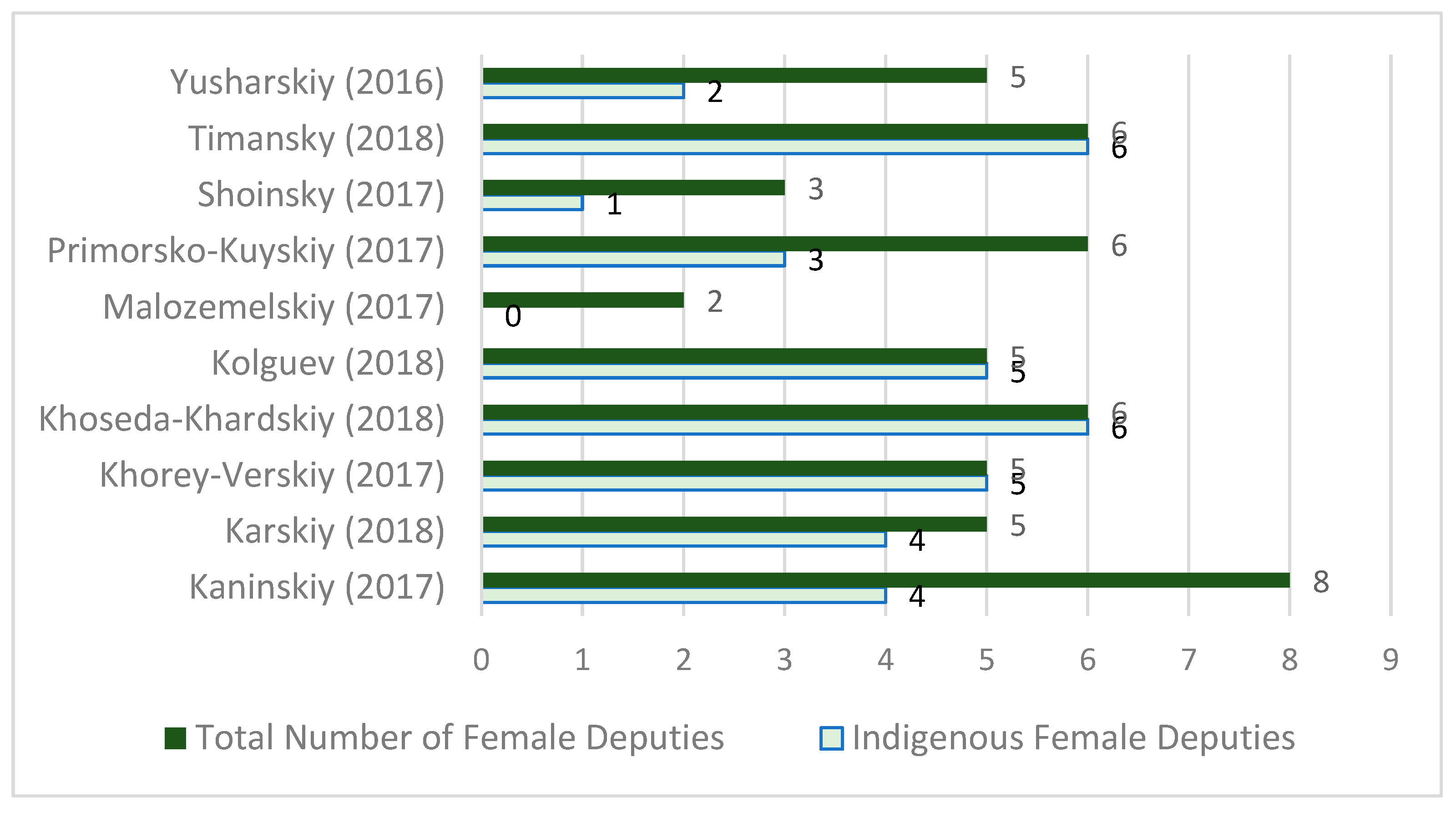

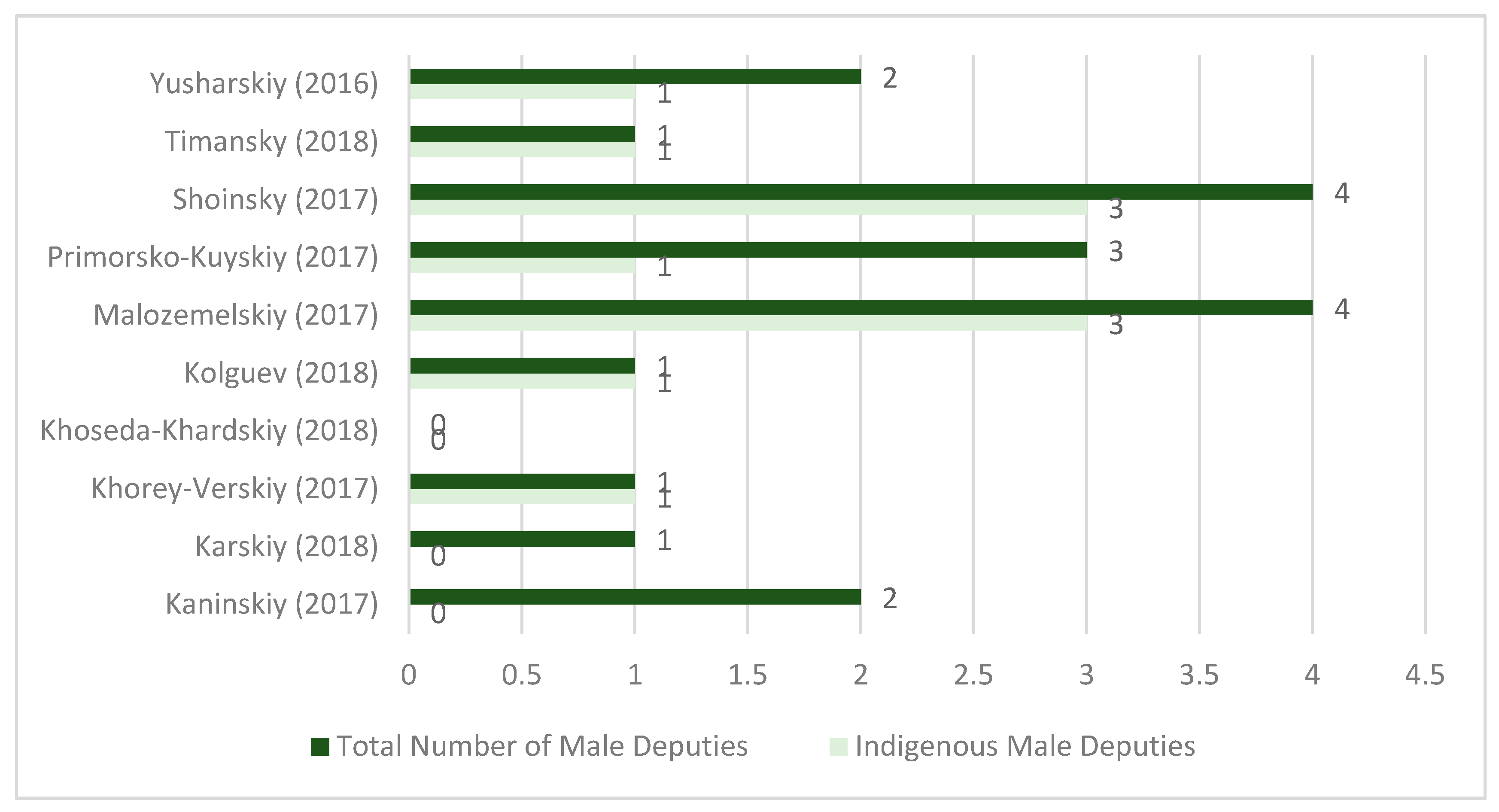

3.2. Female Rising in the Arctic Region of NAO

“If Not Us, Who?”

3.3. Historical and Institutional Roots of Indigenous Women’s Empowerment in the NAO

3.3.1. Top-Down Soviet De-Patriarchization

- Equalizing women’s and men’s legal and socio-economic statuses in the Soviet economy and statehood (Ayvazova 1998); limiting the concept of gender-specific jobs in favor of expanding of the list of unisex professions in the Soviet industrial complex.

- Transitioning from nomadism to a sedentary life accompanied by “social nomadism”, which offered a wide range of new social statuses and roles to explore (Kiselev and Moldanova 2018, p. 575).

- Enrolling women in primary and secondary schools and universities, as well as vocational training programs (as a result, within a few decades, there was a radical turn from the almost absolute illiteracy of indigenous women in the Arctic towards the formation of a female indigenous intelligentsia).

- Changing mothers’ roles in children’s upbringing (traditional child-rearing was interpreted as a hindrance on the path towards woman’s self-realization) by establishing a system of kindergartens and boarding schools starting in the 1930s.

- Encouraging indigenous female korenizastsiya (nativization) through participation in the formation of the regional and local government bodies, as well as in a growing economic (industrial) sector (Kiselev and Moldanova 2018, p. 575).

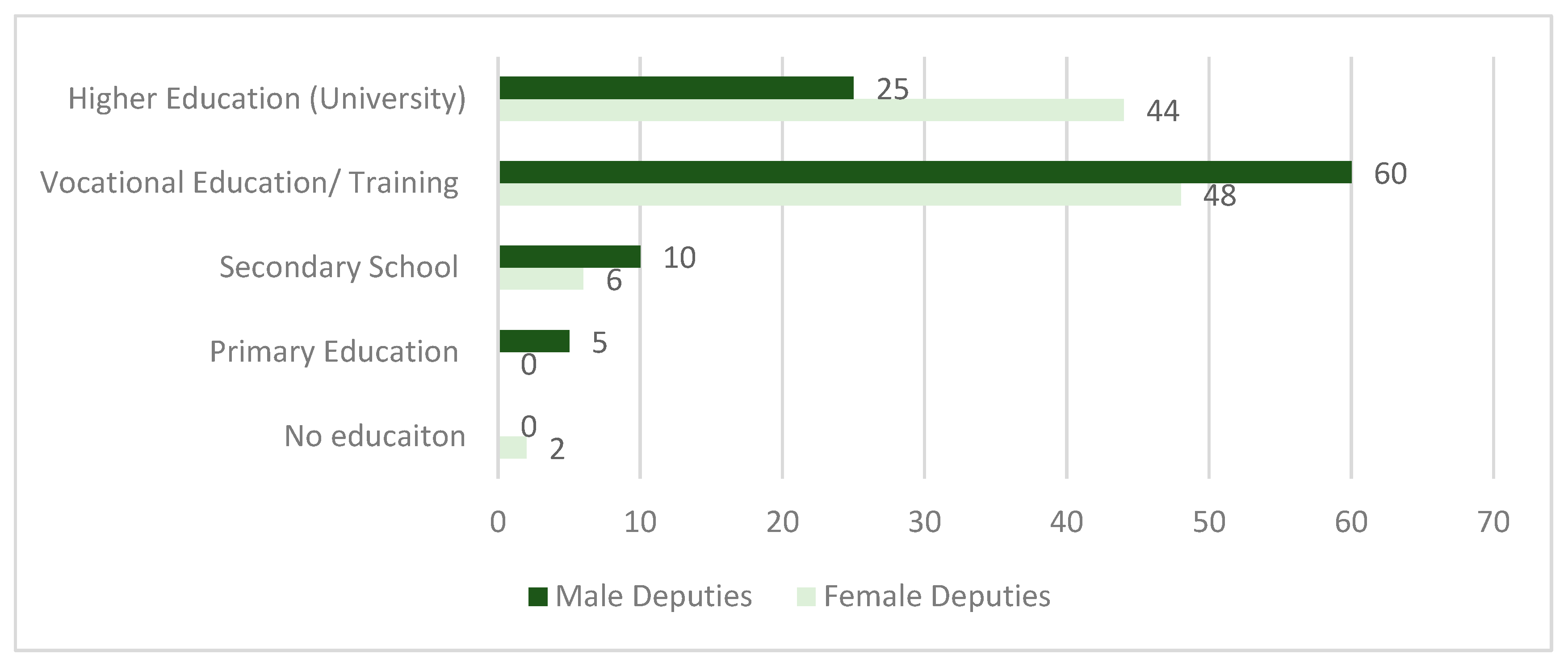

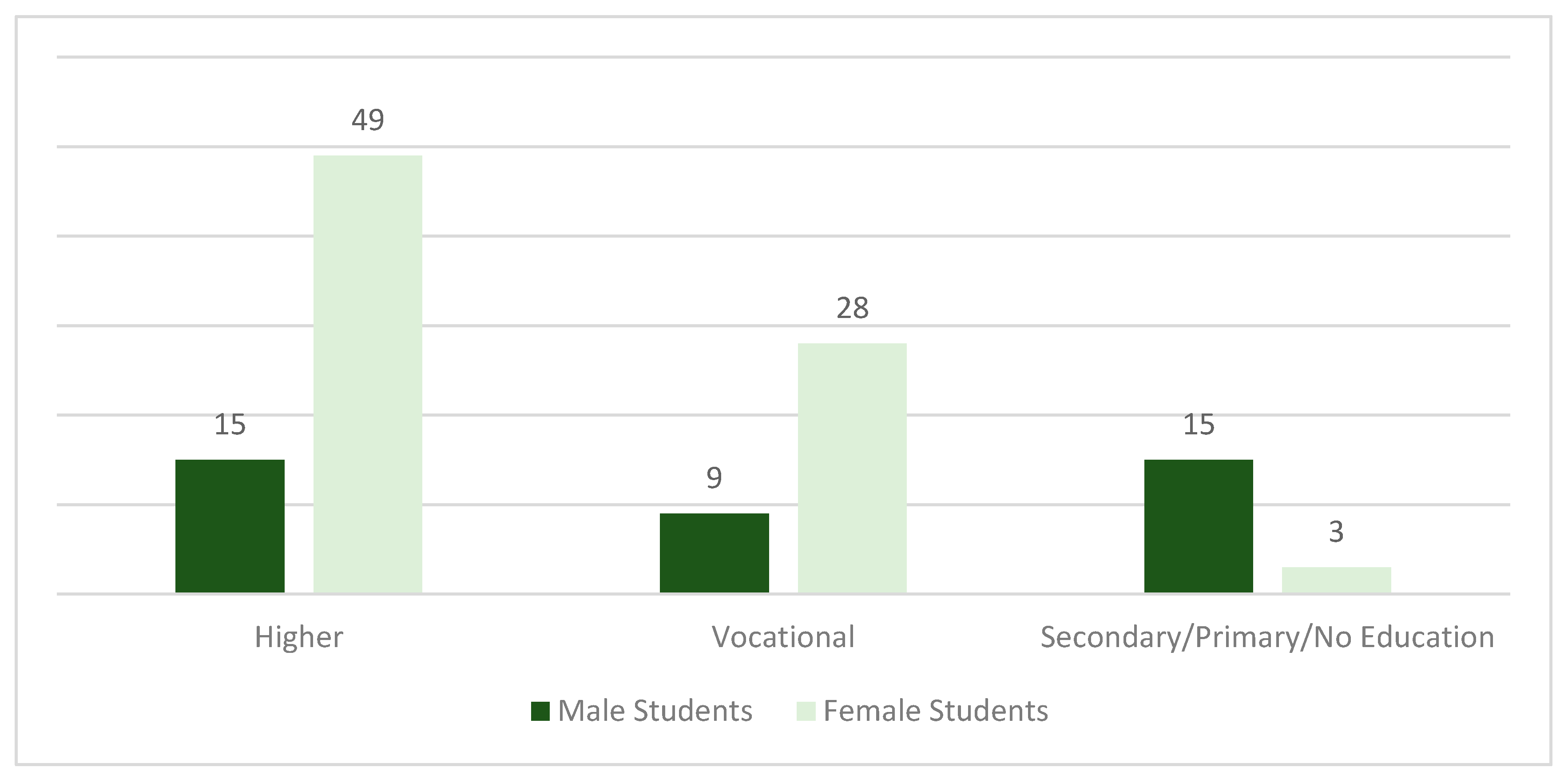

3.3.2. Gender Disparities in Education Strategies and Career Orientation

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References and Notes

- Alexander, Amy C., Catherine Bolzendahl, and Farida Jalalzai, eds. 2018. Measuring Women’s Political Empowerment across the Globe: Strategies, Challenges and Future Research. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Ayvazova, Svetlana. 1998. Russkie zhenshchiny v labirinte ravnopraviia (ocherki politicheskoi teorii i istorii). Moscow: RIK Rusanova. [Google Scholar]

- Ayvazova, Svetlana. 2014. Transformatsiia gendernogo poryadka v stranakh SNG: institutsional’nyye faktory i effekty massovoi politiki. Zhenshchina v rossiiskon obshchestve 4: 11–23. [Google Scholar]

- Ayvazova, Svetlana. 2016. Gendernyi rakurs massovoi politiki. Zhenshchina v rossiiskom obshchestve 1: 24–34. [Google Scholar]

- Ayvazova, Svetlana. 2017. Gendernyi diskurs v pole konservativnoi politiki. Zhenshchina v rossiiskom obshchestve 4: 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, Lynn. 2002. Using Empowerment and Social Inclusion for Pro-poor Growth: A Theory of Social Change. Working Draft of Background Paper for the Social Development Strategy Paper. Washington, DC: World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Blomberg, Eva, Yulia Gradskova, Ylva Waldemarson, and Alina Žvinklienė. 2017. Gender Equality on a Grand Tour: Politics and Institutions—The Nordic Council, Sweden, Lithuania and Russi. Leiden: BRILL. [Google Scholar]

- Bodenhorn, Barbara. 1990. “I’m not the great hunter, my wife is”: Inupiat and anthropological models of gender. Etudes/Inuit Studies 14: 55–74. [Google Scholar]

- Carson, Dean, Rasmus Ole Rasmussen, Prescott Ensign, Lee Huskey, and Andrew Taylor, eds. 2011. Demography at the Edge: Remote Human Populations in Developed Nations. Burlington: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Chandler, Andrea. 2013. Democracy, Gender and Social Policy in Russia. Basingstoke: Palgrave McMillan. [Google Scholar]

- Dahl, Jens. 2010. Identity, Urbanization and Political Demography in Greenland. Acta Borealia 27: 125–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decree of the Government of the Russian Federation of March 14, 2018 No. 420-R “National Strategy and Action Plan for Women for the Period 2017–2022.”

- Dorzheyeva, Viktoria. 2013. Izmeneniia v polozhenii zhenshchin korennykh malochislennykh narodov Severo-Vostoka Rossii (nachalo XX—konets XX v.). Ph.D. dissertation, Buryat State University, Ulan-Ude, Buryatia, Russia. [Google Scholar]

- Eikjok, Jorunn. 2007. Gender, essentialism and feminism in Samiland. In Making Space for Indigenous Feminism. Edited by Joyce Green. London: Zed Books, pp. 108–23. [Google Scholar]

- Einhorn, Barbara. 2006. Citizenship in Enlarged Europe: From Dream to Awakening. Basingstoke: Palgrave McMillan. [Google Scholar]

- Engel, Barbara Alpern, and Anastasia Posadskaya-Vanderbeck. 1998. A Revolution of Their Own. Boulder: Westview Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fogel-Chance, Nanacy. 1993. Living in Both Worlds: “Modernity” and “Tradition” among North Slope Iñupiaq Women in Anchorage. Arctic Anthropology 30: 94–108. [Google Scholar]

- Global Gender Gap Report. 2018. Cologny/Geneva: World Economic Forum. Available online: http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GGGR_2018.pdf (accessed on 27 October 2019).

- Hamilton, Lawrence. 2010. Footprints: Demographic Effects of Out-Migration. In Migration in the Circumpolar North: Issues and Contexts. Edited by Lee Huskey and Chris Southcott. Edmonton: Canadian Circumpolar Institute, pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, Lawrence, and Rasmos Ole Rasmussen. 2010. Population, Sex Ratios and Development in Greenland. Arctic 63: 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hamilton, Lawrence, and Carole L. Seyfrit. 1994. Female Flight? Gender Balance and Out-migration by Native Alaskan Villagers. Arctic Medical Research 53: 189–93. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, Lawrence, Rasmus Ole Rasmussen, Nicholas E. Flanders, and Carole L. Seyfrit. 1996. Outmigration and Gender Balance in Greenland. Arctic Anthropology 33: 89–97. [Google Scholar]

- Heitlinger, Alena. 1979. Women and State Socialism. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Heleniak, Timothy. 2019. Where did all the men go? The changing sex composition of the Russian North in the post-Soviet period, 1989–2010. Polar Record, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglehart, Ronald, and Pippa Norris. 2003. Rising Tide Gender Equality and Culture Change Around the World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Irlbacher-Fox, Stephanie. 2015. Political participation of women in the Northwest Territories (NWT), Canada. In Gender Equality in the Arctic: Current Realities, Future Challenges; Edited by Embla Eir Oddsdóttir, Atli Már Sigurðsson and Sólrún Svandal. Reykjavik: Ministry for Foreign Affairs. [Google Scholar]

- Janovicek, Nancy. 2003. “Assisting Our Own”: Urban Migration, Self-Governance, and Native Women’s Organizing in Thunder Bay, Ontario, 1972–1989. The American Indian Quarterly 27: 548–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, Lois, ed. 2019. The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2019. New York: United Nations Publications, Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2019/The-Sustainable-Development-Goals-Report-2019.pdf (accessed on 29 November 2019).

- Khakhovskaya, Lyudmila. 2016. Gendernyi aspekt urbanizatsii korennykh narodov Magadanskoi oblasti. Zhenshchina v rossiiskom obshchestve 3: 63–72. [Google Scholar]

- Kiselev, Aleksandr, and Nadezhda Moldanova. 2018. Obrazy zhenshchiny v traditsionnoi kul’ture severian i sovetskom ofitsioze vtoroi poloviny 30-kh godov. Vestnik ugrovedeniia 8: 568–84. [Google Scholar]

- Kochergina, Ekaterina. 2017. Uchastie zhenshchin v politike. Moscow: Levada-Center, Available online: https://www.levada.ru/2017/10/16/uchastie-zhenshhin-v-politike-2/ (accessed on 14 August 2019).

- Kochkina, Ekaterina. 2003. Predstavitel’stvo zhenshchin v strukturakh vlasti Rossii, 1917–2002 gg. In Gendernaia Rekonstruktsiia Politicheskikh System. Edited by Natalia Stepanova, Mikhail Kirichenko and Elena Kochkina. St. Petersburg: Aleteiia. [Google Scholar]

- Kulmala, Meri. 2010. Women rule this country: Women’s community organizing and care in rural Karelia. Anthropology of East Europe Review 28: 164–85. [Google Scholar]

- Kulmala, Meri. 2014. Karelian women’s network: A (feminist) women’s movement? In Women and Transformation in Russia. Edited by Aino Saarinen, Kirsti Ekonen and Valentina Uspenskaia. London: Routledge, pp. 163–88. [Google Scholar]

- Lapidus, Gail Warshofsky. 1978. Women in Soviet Society Equality, Development, and Social Change. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Larsen, Joan Nymand, and Gail Fondahl, eds. 2014. Arctic Human Development Report: Regional Processes and Global Linkages. Copenhagen: Norden. [Google Scholar]

- Larsen, Joan Nymand, Peter P. Schweitzer, and Andrey Petrov. 2015. Arctic Social Indicators. ASI II: Implementation. Copenhagen: Nordic Council of Ministers. [Google Scholar]

- Lyarskaya, Elena. 2004. Northern residential schools in contemporary Yamal Nenets culture. Sibirica 4: 74–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyarskaya, Elena. 2006. «U nikh zhe vse ne kak u liudei…»: Nekotorye stereotipnye predstavleniia pedagogov Iamalo-Nenetskogo okruga o tundrovikakh. Antropologicheskii forum 5: 242–58. [Google Scholar]

- Lyarskaya, Elena. 2010. Zhenshchiny i tundra. Gendernyi sdvig na Yamale? Antropologicheskii forum 13: 3–38. [Google Scholar]

- Nabok, Igor, and Stella Serpivo. 2017. Transformatsiia zhenskogo prostranstva traditsionnoi kul’tury nentsev k nachalu 20 v. Vestnik arkheologii, antropologii i etnografii 1: 110–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, Deepa, ed. 2002. Empowerment and Poverty Reduction: A Sourcebook. Washington, DC: World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Neftegaz.RU. 2018. “Budet neprosto.” Vlasti Nenetskogo avtonomnogo okruga khotiat snizit’ zavisimost’ regional’nogo biudzheta ot neftianykh tsen. Neftegaz.RU. July 25. Available online: https://neftegaz.ru/news/finance/199705-budet-neprosto-vlasti-nenetskogo-avtonomnogo-okruga-khotyat-snizit-zavisimost-regionalnogo-byudzheta/ (accessed on 17 November 2019).

- Norris, Pippa. 2004. Electoral Engineering. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Norris, Mary Jane, Stewart Clatworthy, and Evelyn Peters. 2013. The Urbanization of Aboriginal Populations in Canada: A Half Century in Review. In Indigenous in the City: Contemporary Identities and Cultural Innovation. Edited by Evelyn Peters and Chris Andersen. Vancouver: UBC Press Canada, pp. 29–45. [Google Scholar]

- Oddsdóttir, Embla Eir, Atli Már Sigurðsson, and Sólrún Svandal, eds. 2015. Gender Equality in the Arctic: Current Realities, Future Challenges; Reykjavik: Ministry for Foreign Affairs.

- Perevalova, Elena. 2015. Interv’iu s olenevodami Yamala o padezhe oleney i perspektivakh nenetskogo olenevodstva. Uralskiy istoricheskiy vestnik 2: 39–49. [Google Scholar]

- PIRE Indicators. 2019. Program for International Research and Education Project: Promoting Urban Sustainability in the Arctic. Available online: https://blogs.gwu.edu/arcticpire/ (accessed on 22 November 2019).

- Povoroznyuk, Olga, Joachim Otto Habeck, and Virginie Vaté. 2010. Povoroznyuk, Olga, Joachim Otto Habeck, and Virginie Vaté. 2010. On the definition, theory, and practice of gender shift in the North of Russia: Introduction. Anthropology of East Europe Review 28: 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Racioppi, Linda, and Katherine O’Sullivan See. 2009. Gender Politics in Post-Communist Eurasia. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen, Rasmus Ole. 2007. Polar Women Go South. Journal of Nordregio 7: 20–22. [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen, Rasmus Ole. 2015. Gender Perspectives on Path Dependency (Paper presentation). In Gender Equality in the Arctic: Current Realities, Future Challenges; Edited by Embla Eir Oddsdóttir, Atli Már Sigurðsson and Sólrún Svandal. Reykjavik: Ministry for Foreign Affairs. [Google Scholar]

- Rozanova, Marya. 2019. Indigenous Urbanization in Russia’s Arctic: The Case of Nenets Autonomous Region. Sibirica 18: 54–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saarinen, Aino, Kirsti Ekonen, and Valentina Uspenskaia, eds. 2014. Women and Transformation in Russia. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Sachs, Jeffrey, Guido Schmidt-Traub, Christian Kroll, Guillaume Lafortune, and Grayson Fuller. 2019. Sustainable Development Report 2019. New York: Bertelsmann Stiftung and Sustainable Development Solutions Network (SDSN). [Google Scholar]

- Segovia-Pérez, Mónica, Pilar Laguna-Sánchez, and Concepción de la Fuente-Cabrero. 2019. Education for Sustainable Leadership: Fostering Women’s Empowerment at the University Level. Sustainability 11: 5555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Serpivo, Stella. 2014. K voprosu o gendernom prostranstve v traditsionnoi kul’ture nentsev. In Sibirskiy sbornik—4: Grani sotsial’nogo: Antropologicheskiye perspektivy issledovaniya sotsial’nykh otnosheniy i kul’tury. Edited by Vladimir Davydov and Dmitriy Arzyutov. St. Petersburg: MAE RAN, pp. 442–48. [Google Scholar]

- Slezkine, Yuri. 1994. Arctic Mirrors: Russia and the Small Peoples of the North. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sobranie deputatov Official Website. 2019. Available online: www.sdnao.ru (accessed on 12 December 2019).

- Sokolovskiy, Sergey. 2008. Korennyye narody: mezhdu integratsiei i sokhraneniem kul’tur. In Etnicheskiye kategorii i statistika. Debaty v Rossii i vo Frantsii. Edited by Elena Filippova. Moscow: FGNU “Rosinformagrotekh”. [Google Scholar]

- Sovet Federatsii Official Website. 2019. Available online: council.gov.ru (accessed on 29 December 2019).

- Ssorin-Chaikov, Nikolai V. 2003. The Social Life of the State in Subarctic Siberia. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- State Duma Official Website. 2019. Available online: duma.gov.ru (accessed on 29 December 2019).

- Sumarokov, Yury, Tormod Brenn, Alexander V. Kudryavtsev, and Odd Nilssen. 2014. Suicides in the Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations in the Nenets Autonomous Okrug, Northwestern Russia, and associated socio-demographic characteristics. International Journal of Circumpolar Health 73: 24308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundström, Aksel, and Lena Wängnerud. 2018. Women’s Empowerment at the Local Level. In Measuring Women’s Political Empowerment across the Globe: Strategies, Challenges and Future Research. Edited by Amy C. Alexander, Catherine Bolzendahl and Farida Jalalzai. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 117–37. [Google Scholar]

- Tarmakhanov, Efrem, and Elizaveta Badmatsyrenova. 2010. Institutsional’nye aspekty gosudarstvennoi politiki po vovlecheniiu zhenshchin v obshchestvenno-politicheskuiu deiatel’nost’ v usloviiakh natsional’nogo regiona (na primere Buryat-Mongol’skoi ASSR). Gumanitarnyy vektor 3: 54–58. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, Andrew. 2011. Current evidence of ‘female flight’ from remote Northern Territory Aboriginal communities—Demographic and policy implications. Migration Letters 8: 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The 1918 Constitution of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic. 1918. Available online: http://constitution.garant.ru/science-work/modern/3988990/ (accessed on 2 September 2019).

- The 1936 Constitution of the Soviet Union. 1936. Available online: http://www.departments.bucknell.edu/russian/const/1936toc.html (accessed on 2 September 2019).

- The Law of the Nenets Autonomous District. 2008. “On State Support of Traditional Types of Management and Industries of the Indigenous Minorities of the North in the Nenets Autonomous Region” of January 28, 2008, No. 1-OZ; Federal Law of the Russian Federation “On Guarantees of the Rights of Indigenous Minorities of the Russian Federation” of April 30, 1999, No. 82-FZ; The Federal Law of the Russian Federation “On the Territories of Traditional Nature Use of the Indigenous Minorities of the North, Siberia and the Far East of the Russian Federation” of May 7, 2001, No. 49-FZ; Federal Law of the Russian Federation “On the General Principles of the Organization of Communities of Indigenous Minorities of the North, Siberia and the Far East of the Russian Federation” of July 20, 2000, No. 104-FZ; Federal Law of the Russian Federation “On Fisheries and the Conservation of Aquatic Biological Resources” of December 20, 2004, No. 166-FZ; Federal Law of the Russian Federation “On Hunting and on the Conservation of Hunting Resources and on Amendments to Certain Legislative Acts of the Russian Federation” of July 24, 2009, No. 209-FZ.

- The Russian Census of 2002. 2002. Federal State Statistics Service of Russia. Available online: http://www.perepis2002.ru/index.html?id=11 (accessed on 19 September 2019).

- The Russian Census of 2010. 2010. Federal State Statistics Service of Russia. Available online: https://gks.ru/free_doc/new_site/perepis2010/croc/perepis_itogi1612.htm (accessed on 19 September 2019).

- The Russian Orthodox Church. 2006. Orthodox Declaration on Human Rights and Dignity. Paper presented at The Tenth World Russian People’s Council, Moscow, Russia, April 6; Available online: http://www.pravoslavieto.com/docs/human_rights/declaration_ru_en.htm (accessed on 9 October 2019).

- Tuisku, Tuula. 2001. The displacement of Nenets women from reindeer herding and the tundra in the Nenets autonomous okrug, Northwestern Russia. Acta Borealia 18: 41–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN General Assembly. 2015. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; A/RES/70/1. New York: UN General Assembly. Available online: https://www.refworld.org/docid/57b6e3e44.html (accessed on 22 November 2019).

- UN Women. 2016. Progress of the World’s Women 2015–2016: Transforming Economies, Realizing Rights; New York: United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women. Available online: http://progress.unwomen.org/en/2015/pdf/UNW_progressreport.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2019).

- Upadhyay, Ushma D., Jessica D. Gipson, Mellissa Withers, Shayna Lewis, Erica J. Ciaraldi, Ashley Fraser, Megan J. Huchko, and Ndola Prata. 2014. Women’s empowerment and fertility: A review of the literature. Social Science & Medicine 115: 111–20. [Google Scholar]

- Ventsel, Aimar. 2018. Blurring masculinities in the Republic of Sakha, Russia. Polar Geography 41: 198–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinokurova, Liliya. 2017. Zhenshchiny korennykh narodov severa: Kochevnitsy Yakutii v meniaiushchemsia mire. In Cila slabykh: Gendernye aspekty vzaimopomoshchi i liderstva v proshlom i nastoyashchem. Edited by Natalya Pushkareva and Tatiana Troshina. Moscow: RAIZHI & IEA RAN, pp. 15–18. [Google Scholar]

- Vinokurova, Liliya, Alena Popova, Sardana Boyakova, and Elvira Myarikyanova. 2004. Zhenshchina Severa: Poisk novoi sotsial’noi identichnosti. Novosibirsk: Novosibirskoe otdelenie izdatel’stva “Nauka”. [Google Scholar]

- Vladimirova, Vladislava. 2018. Security strategies of Indigenous women in Nenets Autonomous Region, Russia. Polar Geography 411: 164–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vladimirova, Vladislava, and Otto J. Habeck. 2018. Introduction: Feminist Approaches and the Study of Gender in Arctic Social Sciences. Polar Geography 41: 145–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Committees | Total Number | Number of Female Elected Deputies | Female Elected Deputies, Percent (↓) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Issues of Family, Women, and Children | 9 | 8 | 89 |

| Culture | 11 | 6 | 55 |

| Education and Science | 18 | 7 | 39 |

| Health Protection | 21 | 5 | 24 |

| Defense | 12 | 1 | 8 |

| Natural Resources, Property, and Land | 20 | 1 | 5 |

| Energy | 28 | 1 | 4 |

| Economic Policy, Industry, Innovation, and Entrepreneurship | 30 | 1 | 3 |

| Financial Market | 12 | 0 | 0 |

| Committees | Total Number | Number of Female Senators | Female Senators, Percent (↓) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Science, Education, and Culture | 16 | 6 | 38 |

| Social Policy | 13 | 5 | 38 |

| Defense and Security | 15 | 2 | 13 |

| Federal Structure, Regional Policy, Local Government, and Northern Affairs | 21 | 2 | 10 |

| Economic Policy | 18 | 0 | 0 |

| Committees | Total Number | Number of Female Elected Deputies | Female Elected Deputies, Percent (↓) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Economic Policy and Budget | 8 | 4 | 50 |

| Nenets and Other Indigenous Peoples, Ecology, and Natural Resources | 7 | 3 | 43 |

| Government and Municipal Affairs | 7 | 3 | 43 |

| Social Policy | 10 | 4 | 40 |

| Education, Culture, and Sports | 8 | 2 | 25 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rozanova, M.S.; Mikheev, V.L. Rethinking Women’s Empowerment: Insights from the Russian Arctic. Soc. Sci. 2020, 9, 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9020014

Rozanova MS, Mikheev VL. Rethinking Women’s Empowerment: Insights from the Russian Arctic. Social Sciences. 2020; 9(2):14. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9020014

Chicago/Turabian StyleRozanova, Marya S., and Valeriy L. Mikheev. 2020. "Rethinking Women’s Empowerment: Insights from the Russian Arctic" Social Sciences 9, no. 2: 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9020014

APA StyleRozanova, M. S., & Mikheev, V. L. (2020). Rethinking Women’s Empowerment: Insights from the Russian Arctic. Social Sciences, 9(2), 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9020014