Classical and Modern Prejudice toward Asylum Seekers: The Mediating Role of Intergroup Anxiety in a Sample of Italians

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Prejudice toward Asylum Seekers

1.2. Intergroup Anxiety

1.3. National Identification

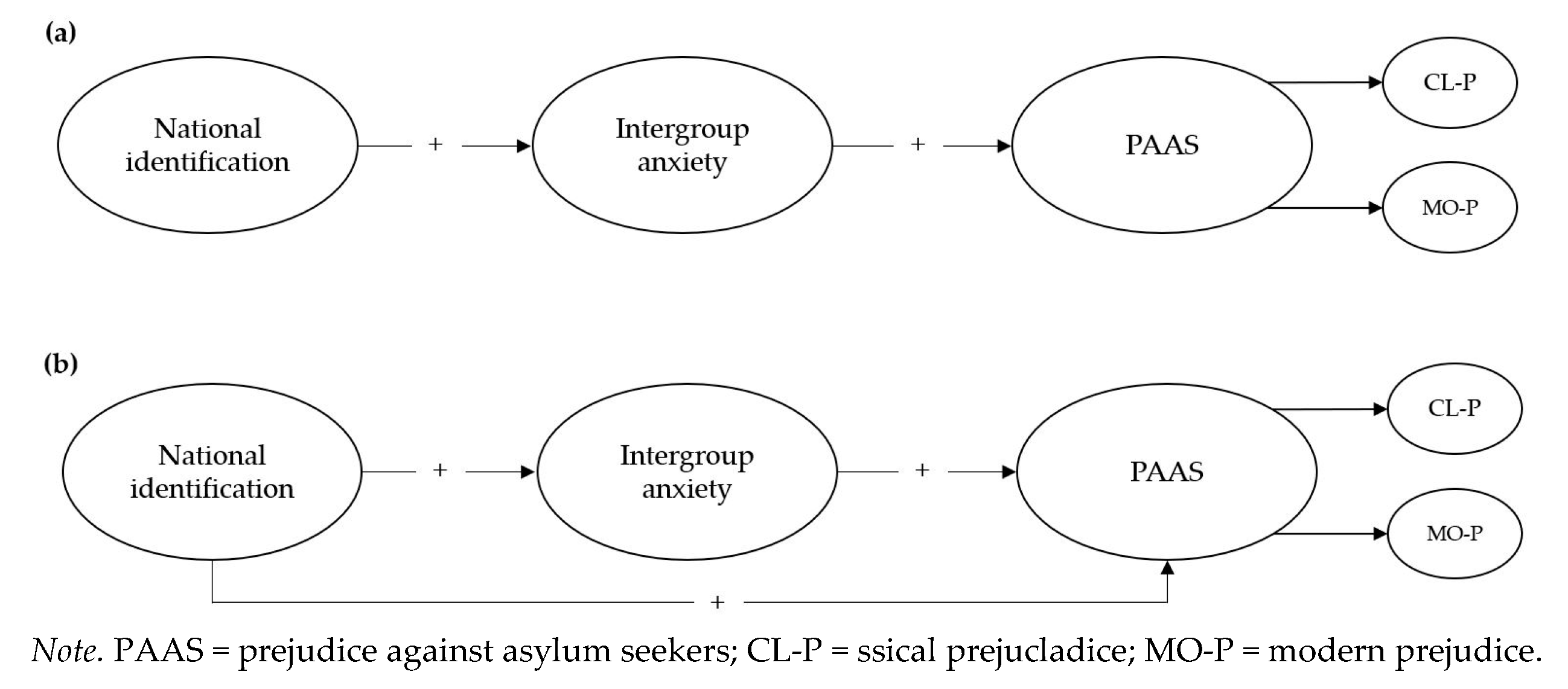

1.4. The Current Study

2. Method

2.1. Participants and Procedures

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. National Identification

2.2.2. Intergroup Anxiety

2.2.3. Prejudice against Asylum Seeker

2.2.4. Demographic Profile

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analyses

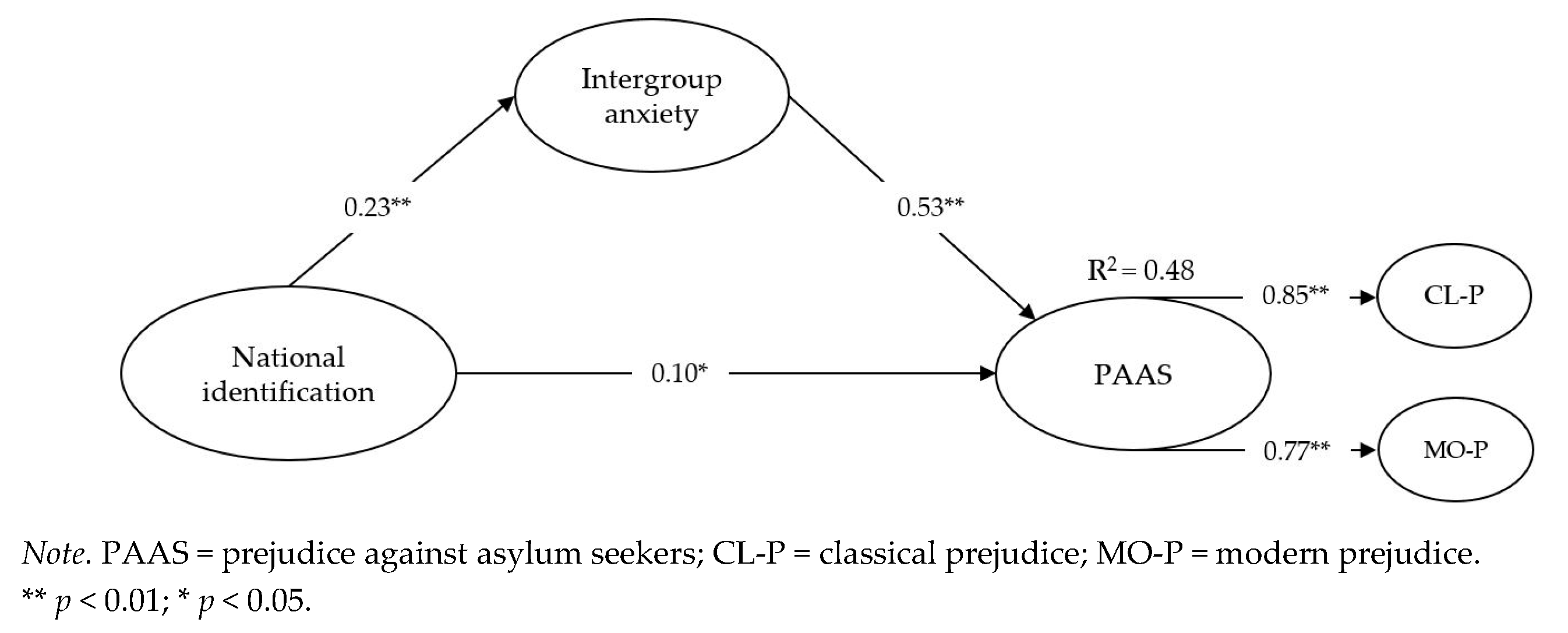

3.2. Mediation Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations and Future Research

4.2. Practical Implications

5. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Allport, Gordon W. 1954. The Nature of Prejudice. Reading: Addison-Wesley Pub. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, Joel R. 2018. The prejudice against asylum seekers scale: Presenting the psychometric properties of a new measure of classical and conditional attitudes. The Journal of Social Psychology 158: 694–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, Joel R. 2019. The moderating role of socially desirable responding in implicit-explicit attitudes toward asylum seekers: Attitudes towards asylum seekers. International Journal of Psychology 54: 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, Joel R., and Rose Ferguson. 2018. Demographic and ideological correlates of negative attitudes towards asylum seekers: A meta-analytic review: Attitudes towards asylum seekers: A meta-analysis. Australian Journal of Psychology 70: 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behling, Orlando, and Kenneth S. Law. 2000. Translating Questionnaires and Other Research Instruments: Problems and Solutions. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Bottura, Benedetta, and Tiziana Mancini. 2016. Psychosocial dynamics affecting health and social care of forced migrants: A narrative review. International Journal of Migration, Health and Social Care 12: 109–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Rupert. 2013. Psicologia Del Pregiudizio. Bologna: Il Mulino. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Rupert, and Miles Hewstone. 2005. An integrative theory of intergroup contact. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology 37: 255–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brylka, Asteria, Tuuli A. Mähönen, Fabian M. H. Schellhaas, and Inga Jasinskaja-Lahti. 2015. From Cultural Discordance to Support for Collective Action: The Roles of Intergroup Anxiety, Trust, and Group Status. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 46: 897–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caricati, Luca, Tiziana Mancini, and Giuseppe Marletta. 2017. The role of ingroup threat and conservative ideologies on prejudice against immigrants in two samples of Italian adults. The Journal of Social Psychology 157: 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Fang F. 2007. Sensitivity of Goodness of Fit Indexes to Lack of Measurement Invariance. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 14: 464–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowling, Misha M., Joel Anderson, and Rose Ferguson. 2019. Prejudice-Relevant Correlates of Attitudes Towards Refugees: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Refugee Studies. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danish Refugee Council. 2018. Mutual Trust Is Still Not Enough. Available online: https://www.refugeecouncil.ch/assets/herkunftslaender/dublin/italien/monitoreringsrapport-2018.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2020).

- Dimitrova, Radosveta, Athanasios Chasiotis, Michael Bender, and Fons J. R. van de Vijver. 2014. From a Collection of Identities to Collective Identity: Evidence From Mainstream and Minority Adolescents in Bulgaria. Cross-Cultural Research 48: 339–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Duckitt, John, and Chris G. Sibley. 2010. Personality, Ideology, Prejudice, and Politics: A Dual-Process Motivational Model: Dual-Process Motivational Model. Journal of Personality 78: 1861–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esses, Victoria M., Gordon Hodson, Scott Veenvliet, and Ljiljana Mihic. 2008. Justice, Morality, and the Dehumanization of Refugees. Social Justice Research 21: 4–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, Roberto, David Sirlopú, and Thomas Kessler. 2010. Prejudice among Peruvians and Chileans as a Function of Identity, Intergroup Contact, Acculturation Preferences, and Intergroup Emotions: Psychological Predictors of Prejudice toward Immigrants and Majority Members. Journal of Social Issues 66: 803–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartley, Lisa K., and Anne Pedersen. 2015. Asylum Seekers and Resettled Refugees in Australia: Predicting Social Policy Attitude from Prejudice Versus Emotion. Journal of Social and Political Psychology 3: 179–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Li-tze, and Peter M. Bentler. 1999. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 6: 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchison, Paul, Raluca Chihade, and Andrei A. Puiu. 2018. Predictors of “the last acceptable racism”: Group threats and public attitudes toward Gypsies and Travellers. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 48: 237–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, James S., Kendrick T. Brown, Tony N. Brown, and Bryant Marks. 2001. Contemporary Immigration Policy Orientations Among Dominant-Group Members in Western Europe. Journal of Social Issues 57: 431–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, Cheryl R., and Clara L. Wilkins. 2010. Group Identification and Prejudice: Theoretical and Empirical Advances and Implications: Group Identification and Prejudice. Journal of Social Issues 66: 461–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, Rex B. 2016. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 4th ed. New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Koc, Yasin, and Joel R. Anderson. 2018. Social Distance toward Syrian Refugees: The Role of Intergroup Anxiety in Facilitating Positive Relations. Journal of Social Issues 74: 790–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotzur, Patrick F., Sarina J. Schäfer, and Ulrich Wagner. 2019. Meeting a nice asylum seeker: Intergroup contact changes stereotype content perceptions and associated emotional prejudices, and encourages solidarity-based collective action intentions. British Journal of Social Psychology 58: 668–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, Winnifred R., Victoria M. Esses, and Richard N. Lalonde. 2013. National identification, perceived threat, and dehumanization as antecedents of negative attitudes toward immigrants in Australia and Canada. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 43: E156–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancini, Tiziana, Benedetta Bottura, and Luca Caricati. 2018. The Role of Perception of Threats, Conservative Beliefs and Prejudice on Prosocial Behavioural Intention in Favour of Asylum Seekers in a Sample of Italian Adults. Current Psychology 1: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardia, Kantital V. 1970. Measures of multivariate skewness and kurtosis with applications. Biometrika 57: 51–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConahay, John B., Betty B. Hardee, and Valerie Batts. 1981. Has Racism Declined in America?: It Depends on Who is Asking and What is Asked. Journal of Conflict Resolution 25: 563–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mckay, Fiona H., Samantha L. Thomas, and Susan Kneebone. 2012. ‘It Would be Okay If They Came through the Proper Channels’: Community Perceptions and Attitudes toward Asylum Seekers in Australia. Journal of Refugee Studies 25: 113–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, Gabrielle, and Yan B. Zhang. 2018. Intergroup Anxiety and Willingness to Accommodate: Exploring the Effects of Accent Stereotyping and Social Attraction. Journal of Language and Social Psychology 37: 330–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mummendey, Amélie, Andreas Klink, and Rupert Brown. 2001. Nationalism and patriotism: National identification and out-group rejection. British Journal of Social Psychology 40: 159–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, Kate E., and David M. Marx. 2013. Attitudes toward unauthorized immigrants, authorized immigrants, and refugees. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology 19: 332–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickerson, Angela M., and Winnifred R. Louis. 2008. Nationality Versus Humanity? Personality, Identity, and Norms in Relation to Attitudes Toward Asylum Seekers. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 38: 796–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Doherty, Kieran C., and Martha Augoustinos. 2008. Protecting the Nation: Nationalist rhetoric on asylum seekers and the Tampa. Journal of Community and Applied Social Psychology 18: 576–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paolini, Stefania, Nicholas C. Harris, and Andrea S. Griffin. 2016. Learning anxiety in interactions with the outgroup: Towards a learning model of anxiety and stress in intergroup contact. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations 19: 275–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paolini, Stefania, Jake Harwood, Miles Hewstone, and David L. Neumann. 2018. Seeking and avoiding intergroup contact: Future frontiers of research on building social integration. Social and Personality Psychology Compass 12: e12422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, Anne, and Emma F. Thomas. 2013. “There but for the grace of God go we”: Prejudice toward asylum seekers. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology 19: 253–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, Anne, and Iain Walker. 1997. Prejudice against Australian Aborigines: Old-fashioned and modern forms. European Journal of Social Psychology 2: 561–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, Anne, Jon Attwell, and Diana Heveli. 2005. Prediction of negative attitudes toward Australian asylum seekers: False beliefs, nationalism, and self-esteem. Australian Journal of Psychology 57: 148–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, Anne, Kevin Dunn, James Forrest, and Craig McGarty. 2012. Prejudice and Discrimination From Two Sides: How Do Middle-Eastern Australians Experience It and How Do Other Australians Explain It? Journal of Pacific Rim Psychology 6: 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettigrew, Thomas F., and Roel W. Meertens. 1995. Subtle and blatant prejudice in western Europe. European Journal of Social Psychology 25: 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettigrew, Thomas F., and Linda R. Tropp. 2008. How does intergroup contact reduce prejudice? Meta-analytic tests of three mediators. European Journal of Social Psychology 38: 922–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riek, Blake M., Eric W. Mania, and Samuel L. Gaertner. 2006. Intergroup Threat and Outgroup Attitudes: A Meta-Analytic Review. Personality and Social Psychology Review 10: 336–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sides, John, and Jack Citrin. 2007. European Opinion About Immigration: The Role of Identities, Interests and Information. British Journal of Political Science 37: 477–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinmayr, Andreas. 2016. Exposure to Refugees and Voting for the Far-Right. (Unexpected) Results from Austria. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/297375609_Exposure_to_Refugees_and_Voting_for_the_Far-Right_Unexpected_Results_from_Austria (accessed on 25 January 2020).

- Stephan, Walter G. 2014. Intergroup Anxiety: Theory, Research, and Practice. Personality and Social Psychology Review 18: 239–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, Walter G., and Cookie W. Stephan. 1985. Intergroup Anxiety. Journal of Social Issues 41: 157–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, Walter G., and Cookie W. Stephan. 2000. An integrated threat theory of prejudice. In The Claremont Symposium on Applied Social Psychology. Reducing Prejudice and Discrimination. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers, pp. 23–45. [Google Scholar]

- Stephan, Walter G., and Cookie W. Stephan. 2017. Intergroup Threats. In The Cambridge Handbook of the Psychology of Prejudice. Edited by C. G. Sibley and F. K. Barlow. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 131–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, Henri, and John Turner. 2001. An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In Key Readings in Social Psychology. Intergroup Relations: Essential Readings. New York: Psychology Press, pp. 94–109. [Google Scholar]

- Tessitore, Francesca, and Giorgia Margherita. 2017. A review of Asylum Seekers and Refugees in Italy: Where is the psychological research going? Mediterranean Journal of Clinical Psychology 5: 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, Rhiannon N., Miles Hewstone, and Alberto Voci. 2007. Reducing explicit and implicit outgroup prejudice via direct and extended contact: The mediating role of self-disclosure and intergroup anxiety. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 93: 369–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turoy-Smith, Katrine M., Robert Kane, and Anne Pedersen. 2013. The willingness of a society to act on behalf of Indigenous Australians and refugees: The role of contact, intergroup anxiety, prejudice, and support for legislative change: The path from experience to change. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 43: E179–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNHCR. 2019. Global Trends Report. Forced Displacement in 2018. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/5d08d7ee7.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2020).

- Van de Vijver, Fons, and Ronald K. Hambleton. 1996. Translating Tests. European Psychologist 1: 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visintin, Emilio P., Eva G. T. Green, Adrienne Pereira, and Polimira Miteva. 2017. How positive and negative contact relate to attitudes towards Roma: Comparing majority and high-status minority perspectives. Journal of Community and Applied Social Psychology 27: 240–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voci, Alberto, and Miles Hewstone. 2003. Intergroup Contact and Prejudice Toward Immigrants in Italy: The Mediational Role of Anxiety and the Moderational Role of Group Salience. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations 6: 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yitmen, Şenay, and Maykel Verkuyten. 2018. Positive and negative behavioural intentions towards refugees in Turkey: The roles of national identification, threat, and humanitarian concern. Journal of Community and Applied Social Psychology 28: 230–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| M | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. National identification | 3.98 | 0.67 | −0.51 | −0.15 | 1 | ||||||

| 2. Intergroup anxiety | 2.50 | 0.80 | 0.41 | 0.14 | 0.25 ** | 1 | |||||

| 3. CL-P | 2.85 | 1.16 | 0.64 | −0.04 | 0.23 ** | 0.52 ** | 1 | ||||

| 4. MO-P | 4.68 | 1.10 | −0.29 | −0.41 | 0.40 ** | 0.38 ** | 0.64 ** | 1 | |||

| 5. Gender a | - | - | - | - | −0.16 ** | 0.06 | −0.15 ** | −0.17 ** | 1 | ||

| 6. Age (years) | 30.21 | 12.56 | 1.32 | 0.54 | 0.23 ** | 0.04 | 0.23 ** | 0.23 ** | −0.27 ** | 1 | |

| 7. Political orientation | 4.81 | 1.36 | −0.36 | -0.05 | −0.25 ** | −0.18 ** | −0.24 ** | −0.17 ** | −0.04 | −0.05 | 1 |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Servidio, R. Classical and Modern Prejudice toward Asylum Seekers: The Mediating Role of Intergroup Anxiety in a Sample of Italians. Soc. Sci. 2020, 9, 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9020010

Servidio R. Classical and Modern Prejudice toward Asylum Seekers: The Mediating Role of Intergroup Anxiety in a Sample of Italians. Social Sciences. 2020; 9(2):10. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9020010

Chicago/Turabian StyleServidio, Rocco. 2020. "Classical and Modern Prejudice toward Asylum Seekers: The Mediating Role of Intergroup Anxiety in a Sample of Italians" Social Sciences 9, no. 2: 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9020010

APA StyleServidio, R. (2020). Classical and Modern Prejudice toward Asylum Seekers: The Mediating Role of Intergroup Anxiety in a Sample of Italians. Social Sciences, 9(2), 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9020010