Academic Causes of School Failure in Secondary Education in Spain: The Voice of the Protagonists

Abstract

1. Introduction

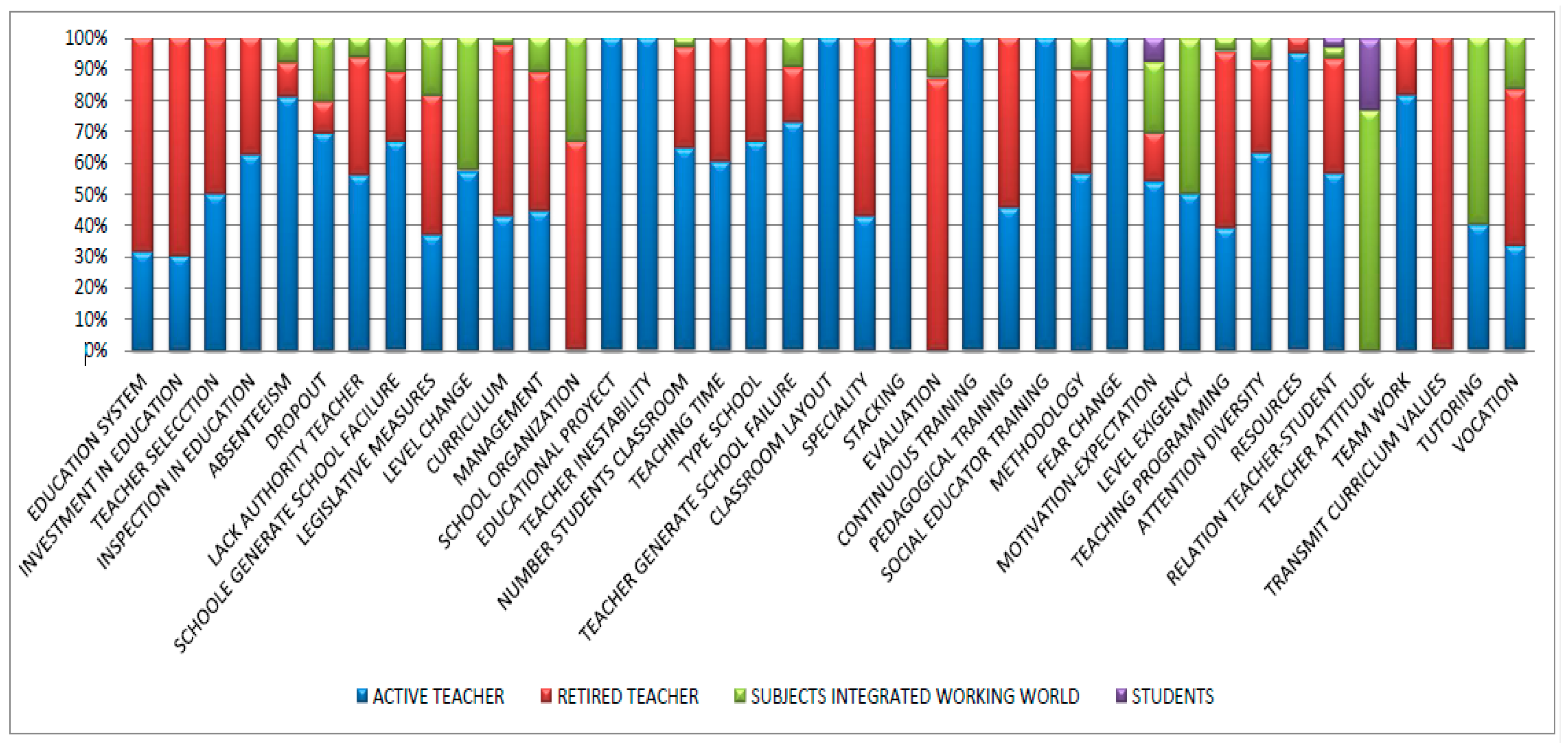

2. Materials and Methods

- At least 10–15 years of service.

- Teachers with at least 10 years of work experience in centers with a high percentage of school failure.

- Currently holding a teaching or management position.

- Teacher of subjects such as Spanish Language and Literature, Mathematics, Biology, Physics and Chemistry, Geography and History and first foreign language.

- Secondary Education teachers may give classes in some of the measures regulated in the legislation for attention to diversity.

- Teachers who have worked at least in the last 10 years in centers where there has been a high percentage of school failure.

- Have held a position in the last 10 years of your professional teaching or management career.

- Students with problems in obtaining the Secondary Education certificate and opt for Basic Professional Training.

- If possible, they have gone through other measures of attention to diversity governed by the legislation.

- Active workers in any trade between the ages of 20 and 36 without a Secondary Education certificate who are currently in Secondary Education for Adults.

- -

- Active teachers: (EPA. Ref )

- -

- Retired teachers: (EPJ. Ref )

- -

- Students with school failure: (EA.Ref )

- -

- Subjects integrated in the workplace: (EPE.Ref)

3. Results

3.1. Causes Relating to the Education System and Other Influential Elements

“How can it not fail? If it is an instability in teaching… This has contributed to the malaise of teachers because they have given us a lot of bureaucratic tasks… as if the important thing is to write more than to do”(EPJ. 6 Ref. 4).

“(…) I am talking about concerted centers, which do not have the preparation they should have or are often contracted because it is more of a company (…)”(EPA. 3 Ref. 1).

“Because these measures require more teachers, because they require more teaching hours (…) because it is what most affects”(EPA. 7 Ref. 2).

“(…) but now effective that they have helped me, that they have gone there to solve for the problems that know appears in the memories of end of course, in the evaluations of each year, nobody.”(EPJ. 3 Ref. 2).

“(…) I have a particular case of a student who has so little respect when it comes to speaking, and you have already had such a lack of respect that it is difficult for me to address her (…), it makes me feel bad”(EPA. 15 Ref. 1).

“In the first two, in the second two and in the third of the Secondary Education, then all of them. I started to miss…”(EA. 10 Ref. 1).

3.2. Causes Relating to the School

“I think both the teacher and the school have a very high percentage of responsibility for school failure. Not all, and in some cases more than in others”(EPA. 5 Ref. 1).

“A school that does not serve to eliminate the three great discriminations that the human being has, is useless, and these are: discrimination of social class (…) of sex or gender (…) and ethnic-cultural discrimination”(EPJ. 2 Ref. 1).

“I think it’s more the center, what zone it’s in (…). If the center is in an area where parents don’t care, then everything is bad.(EPA. 12 Ref. 1).

“We are talking about schools that had 35 students per class, where students with educational needs could have 2 or 3, there are 4 or 5 with a disruptive attitude and only one person to organize all the activity inside the classroom. So I’m sure that you can always do more, that you can articulate means…”(EPA. 17 Ref. 1).

“(…) repetition for me has been a very important handicap as far as student motivation is concerned, as the student who suspends promotes directly. For me, this has been one of the factors that could have influenced failure (…)”(EPJ. 4 Ref. 1).

“I was told by one of the flexible: “he who goes into flexible does not go out anymore”. That is true”(EPA. 6 Ref. 1).

“You don’t get any support teachers anymore, and everything’s different. Each subject with a different teacher… I had a teacher for all of them in primary school.”(EPE. 6 Ref. 1).

“The Secondary Education has contents so abstract and so removed from everyday life… when they should be much closer to the reality of personal circumstances”(EPJ. 10 Ref. 2).

“If we all do not follow the same line, we can create many conflicts”(EPA. 5 Ref. 1).

“A document is made and kept and taken out when necessary, but no systematic work is done”(EPJ. 9 Ref. 2).

“(…) the lack of stability of personnel, there is much interim that can work divinely, but continuity does a lot too”(EPA. 6 Ref. 1).

“(…) there are children who come from a village and have to get up at half past six, and even the four who arrive at their house… How are you going to ask 12 year old children to give up at the last minute on Fridays? If he’s not human.”(LFS. 14 ref. 1).

3.3. Causes Related to the Teacher

“(…) I think it can, but it depends on how the teachers give the class”(EPE. 2 Ref. 1).

“You are afraid of innovation, of the radical changes they propose”(EPA. 12 Ref. 1).

“Mr. teacher, how much percentage do you have of teacher and street educator? I 100% teacher and street educator 0%, go to the construction”(EPA. 4 Ref. 1).

“(…) We enter with a very serious problem that is at the origin of everything, which is the formation of teachers (…) they continue to form with a strong epistemological, theoretical (…) load”(EPJ. 3 Ref. 1).

“My subject… Mathematics, wow,” “then Physics, History…” (…), because that’s not what’s important.(EPJ. 3 Ref. 1).

“If you have a teacher who explains and explains…, there comes a time when you disconnect and get lost. Whether you like it or not this way of teaching makes you despair and pass”(EPE. 5 Ref. 1).

“The media, which unfortunately here despite being an ICT center we have very few computer resources that would be very good. The absence of planning activities related to this can cause school failure”(EPA. 12 Ref. 1).

“(…) he sent us for a week all the exercises of the topic, a lot of work, that’s how it was. And since I didn’t like it, I went by and the teacher said to me: ‘cheer up’, but what do you mean?”(EPE. 3 Ref. 1).

“We did not change the structure of the classes, the tables, six hours looking forward sitting on chairs and the teacher releasing the roll and the students collaborating little”(EPA. 14 Ref. 1).

“When you are younger you see a super-strict teacher, it is that you get bored and leave her, and you don’t need to be clapped to get bored, because if they don’t make it easy for you imagine”(EPE. 1 Ref. 1).

“I’ve met teachers who might sink you inside: “You’re a fool.” Who despise students”(EA. 3 Ref. 1).

“If the teacher comes with a bad face… I don’t know, you get the heavy class”(EA. 4 Ref. 1).

“There are others who have been for many years, are tired and give their class and fly”(EPE. 4 Ref. 2).

“The great coordination with your classmates is: how many topics we are going to give in the first trimester and how many exams we are going to do, without stopping to think about how to organize this specific learning and how I can make it more digestible”(EPJ. 10 Ref. 1).

“You’re doing me the best test, you’re not doing me the best…”(EPE. 4 Ref. 1).

“Maybe it’s also our fault for not teaching them more tools at other stages that they could use so in order to facilitate their study.”(EPA. 1 Ref. 1).

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abiétar-López, Míriam, Almudena A. Navas-Saurin, Fernando Marhuenda-Fluixá, and Francesca Salvà-Mut. 2017. La construcción de subjetividades en itinerario de fracaso escolar. Itinerarios de inserción sociolaboral para adolescentes en riesgo. Pychosocial Intervention 26: 39–45. [Google Scholar]

- Adame, María T., and Francesca Salvà. 2010. Abandono escolar prematuro y transición a la vida activa en una economía turística: El caso de Baleares. Revista de Educación 351: 185–210. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez, Emilio, and Ramón Pérez. 2010. Radiografías de la inspección educativa en la comunidad autónoma de Asturias. Revisión crítica con intención de mejora. Bordón 62: 9–28. [Google Scholar]

- Antelm, Ana Gil Alfonso, María Luz Cacheiro, and Eufrasio Pérez. 2018. Causas del fracaso escolar: Un análisis desde la perspectiva del profesorado y del alumnado. Enseñanza, and Teaching 36: 129–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aristimuño, Adriana, and Juan Pablo Parodi. 2017. Un Caso Real de Combate al Fracaso en la Educación Pública: Una Cuestión de Acompañamiento, Liderazgo y Cultura Organizacional. REICE. Revista Iberoamericana sobre Calidad, Eficacia y Cambio en Educación 15: 141–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abellán, Cecilia Azorín. 2019. Las transiciones educativas y su influencia en el alumnado. Edetania. Estudios y Propuestas Socioeducativas 55: 223–48. [Google Scholar]

- Bardin, Laurence. 2002. Análisis de Contenido. Madrid: Akal, pp. 1–94. [Google Scholar]

- Bolívar, Antonio. 2015. Un currículum común consensuado en torno al Marco Europeo de Competencias Clave. Un análisis comparativo con el caso francés. Avances en Supervisión Educativa 23: 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Bolívar, Antonio, and Miguel A. Pereyra. 2006. El Proyecto DeSeCo sobre la definición y selección de competencias clave. Introducción a la edición española. In Las Competencias Clave para el Bienestar Personal, Social y Económico. Edited by Dominique S. Rychen and Laura H. Salganik. Málaga: Ediciones Aljibe, colección Aula, pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Carbonell, Jaume. 2010. Desde la escuela: Alternativas al fracaso escolar. In En Busca del Éxito Educativo: Realidades y Soluciones. Edited by A. Canalda, J. Carbonell, M. J. Díaz-Aguado, M. Lejarza, F. López, J. A. Luengo and J. A. Marina. Madrid: Fundación Antena, vol. 3, pp. 87–98. [Google Scholar]

- Chaparro, Alicia, Coral González, and Joaquín Caso. 2016. Familia y rendimiento académico: Configuración de perfiles estudiantiles en secundaria. Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa 18: 53–68. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, Álvaro, and Jorge Calero. 2013. Determinantes del riesgo de fracaso escolar en España en PISA-2009 y propuestas de reforma. Revista de Educación 362: 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Da Silva, Tricia, and Arun Ravindran. 2016. Contribuyentes al fracaso académico en la educación postsecundaria: Una revisión y un contexto canadiense. International Journal Non-Commun Diseases 1: 9–17. [Google Scholar]

- De Castro, Rosa M., and Dora I. Fialho. 2019. Education and Attachment: Guidelines to Prevent School Failure. Multimodal Technologies and Interaction 3: 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drake, Sean. 2019. The Segregation of “Failures”: Unequal Schools and Disadvantaged Students in an Affluent Suburb. Journal of Education for Students Placed at Risk (JESPAR). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escudero, Juan M. 2016. Inclusión y Exclusión Educativa: Realidades, Miradas y Propuestas. Valencia: Nau Llibres, pp. 1–208. [Google Scholar]

- Escudero, Juan M., and Begoña Martínez. 2012. Las políticas de lucha contra el fracaso escolar: ¿programas especiales o cambios profundos del sistema y la educación? Revista Educación, Número Extraordinario, 174–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escudero, Juan M., María T. González, and Begoña Martínez. 2009. El fracaso escolar como exclusión educativa: Comprensión, políticas y prácticas. Revista Iberoamericana de Educación 50: 41–64. [Google Scholar]

- Feito, Rafael. 2015. La experiencia escolar del alumnado de la ESO de adultos. Un viaje de ida y vuelta. Revista de la Asociación de Sociología de la Educación 8: 44–56. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández, Mariano, Luis Mena, and Jaime Riviere. 2010. Fracaso y Abandono Escolar en España. Barcelona: Fundación La Caixa, pp. 1–232. [Google Scholar]

- Gázquez, José Jesús, and Jose Carlos Núñez. 2018. Students at Risk of School Failure. Lausanne: Frontiers Media. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, Ignacio, and Isabel López. 2010. Improving the quality of education for all o la concepción de la eficacia escolar desde la visión del profesorado. Revista Iberoamericana de Educación 54: 123–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, Rachel. 2016. We can’t let them fail for one more day’: School reform urgency and the politics of reformer-community alliances. Race Ethnicity and Education 19: 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibabe, Izaskun. 2016. Academic Failure and Child-to-Parent Violence: Family Protective Factors. Frontiers in Psychology 7: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurado, Pedro, and Jose Tejada. 2019. Disruption and School Failure. A Study in the Context of Secondary Compulsory Education in Catalonia. Estudios Sobre Educación 36: 135–55. [Google Scholar]

- Marina, José A., Carmen Pellicer, and Jesús Manso. 2015. Libro Blando de la Profesión Docente y su Entorno Escolar. Madrid: MEC, pp. 1–87. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Otero, Valentín. 2009. Diversos condicionantes del fracaso escolar en la educación secundaria. Revista Iberoamericana de Educación 51: 67–85. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Valdivia, Estefanía, Inmaculada García-Martínez, and Marilina Higueras-Rodríguez. 2018. El Liderazgo para la Mejora Escolar y la Justicia Social. Un Estudio de Caso sobre un Centro de Educación Secundaria Obligatoria. Revista Iberoamericana sobre Calidad, Eficacia y Cambio en Educación 16: 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, James H., and Sally Schumacher. 2012. Investigación Educativa. Una Introducción Conceptual, 5th ed. Madrid: Pearson Addison Wesley, pp. 1–664. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Education and Vocational Training. 2015. Panorama de la Educación. Indicadores de la OCDE 2015. Informe Español; Madrid: Secretaria General técnica.

- Ministry of Education and Vocational Training. 2019. Panorama de la Educación. Indicadores de la OCDE 2019. Informe español; Madrid: Secretaria General técnica.

- Mínguez, Ramon, Eduardo Romero, and Andrés Gregorio. 2019. School failure and vulnerable families.a qualitative study. Revista Boletín Redipe 8: 23–41. [Google Scholar]

- Moral, Cristina, Marilina Higueras-Rodríguez, Ana Martín-Romera, Estefanía Martínez-Valdivia, and Amelia. 2019. Effective practices in leadership for social justice. Evolution of successful secondary school principalship in disadvantaged contexts. International Journal of Leadership in Education. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, Tiburcio. 2010. La relación familia-escuela en Secundaria: Algunas razones del fracaso escolar. Profesorado. Revista de Currículo y Formación del Profesorado 14: 242–55. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. 2016. Low Performing Students: Why They Fall Behind and How To Help Them Succeed. Paris: OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. 2019. TALIS 2018 Results (Volume I): Teachers and School Leaders as Lifelong Learners. Paris: OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmos, Patricia, and Oscar Mas. 2013. Jóvenes, fracaso escolar y programas de segunda oportunidad. Revista Española de Orientación y Psicopedagogía 24: 78–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, Ángel I. 2010. Reinventar la profesión docente, un reto inaplazable. Revista Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado 68: 11–14. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez, Rubio Ana M. 2007. Los procesos de exclusión en el ámbito escolar: El fracaso escolar y sus actores. Revista Iberoamericana de Educación 43: 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez, Carmen N., and Moises Betancort. 2013. Influencia de la familia en el rendimiento académico. Un estudio en Canarias. Revista Internacional de Sociología 71: 169–87. [Google Scholar]

- Pulido, Federico, and Francisco Herrera. 2016. Miedo y rendimiento académico en el contexto pluricultural de Ceuta. Revista de Investigación Educativa 34: 185–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roca, Enrique. 2010. El abandono temprano en educación y la formación en España. Revista de Educación, Número Extraordinario 1: 31–62. [Google Scholar]

- Rujas, Javier. 2017. Dispositivos institucionales y gestión del fracaso escolar: Las paradojas de la atención a la diversidad en la ESO. Cuadernos de Relaciones Laborales 35: 327–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, Natalia Suárez, Ellián Tuero Herrero, Ana Belén Bernardo Gutiérrez, María Estrella Fernández Alba, Rebeca Cerezo Menéndez, Julio Antonio González-Pienda García, Pedro Rosário, and José Carlos Núñez Pérez. 2011. El fracaso escolar en educación secundaria: Análisis del papel de la implicación familiar. In Revista de Formación del Profesorado e Investigación Educativa. vol. 24, pp. 49–64. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. 2016. Educación 2030. Declaración de Incheon y Marco de Acción para la realización del Objetivo de Desarrollo Sostenible 4. Available online: http://www.unesco.org/new/es/santiago/education-2030/ (accessed on 5 January 2020).

- Vázquez, Rosa. 2018. Hacia una literacidad del fracaso escolar y del abandono temprano desde las voces de adolescents y jóvenes. Resistencias, «cicatrices» y destino. Cádiz: Universidad de Cádiz, pp. 1–186. [Google Scholar]

- Wennström, Johan. 2019. Marketized education: How regulatory failure undermined the Swedish school system. Journal of Education Policy. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Academics Factors | School G.F.E (School Generate School Failure) | Teacher G.F.E (Teacher Generate School Failure) |

|---|---|---|

| education system | level change | classroom layout |

| investment in education | curriculum | specialty |

| teacher selection | management | stacking |

| inspection in education | school organization | evaluation |

| lack of authority and respect for the teacher | school’s educational project | transmit. curriculum values |

| absenteeism | teaching time | pedagogical training |

| dropout | teacher instability | social educator training |

| legislative measures | continuing education | |

| number of students per classroom | methodology | |

| type of school | fear of change | |

| motivation and expectation | ||

| level of exigency | ||

| teaching program | ||

| attention to diversity | ||

| resources | ||

| teacher–student relationship | ||

| teacher attitude | ||

| teamwork | ||

| tutoring | ||

| vocation |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Martínez-Valdivia, E.; Burgos-Garcia, A. Academic Causes of School Failure in Secondary Education in Spain: The Voice of the Protagonists. Soc. Sci. 2020, 9, 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9020011

Martínez-Valdivia E, Burgos-Garcia A. Academic Causes of School Failure in Secondary Education in Spain: The Voice of the Protagonists. Social Sciences. 2020; 9(2):11. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9020011

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartínez-Valdivia, Estefanía, and Antonio Burgos-Garcia. 2020. "Academic Causes of School Failure in Secondary Education in Spain: The Voice of the Protagonists" Social Sciences 9, no. 2: 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9020011

APA StyleMartínez-Valdivia, E., & Burgos-Garcia, A. (2020). Academic Causes of School Failure in Secondary Education in Spain: The Voice of the Protagonists. Social Sciences, 9(2), 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9020011