Abstract

This article investigates Twitter replies to tweets concerning the Russia Investigation, published by the United States President, Donald J. Trump. Using a qualitative content analysis, we examine a sample of 200 tweet replies within the timeframe of the first 16 months of Trump’s presidency to explore the arguments made in favor or not in favor of Trump in the comment replies. The results show more anti-Trump than pro-Trump rhetoric in the Twitter replies; the ratio of comments displaying support for Trump or his innocence does not even reach 10%. This study concludes that Trump’s tweets do not inform his Twitter audience’s opinion on this matter, and that Trump’s repetition of catchphrases on the Russia Investigation did not have a measurable impact on his Twitter audience’s responses.

1. Introduction

Twitter as a social media platform “offers diverse means to share news [and discuss] from various sources, resulting in a stream of information, opinions, and emotions” (Maireder and Ausserhofer 2014, p. 305). The Twitter platform can use functions like the hashtag to spread and structure debates, campaigns, and larger discourse. Hashtag-driven political discourse is often constructed by Twitter ‘influencers’ like media and elite users (e.g., politicians). Unlike the mainstream media, Twitter’s trending topics and themes are promoted from within its own communities, which provides a unique opportunity for Twitter influencers (e.g., celebrities, journalists, and elite politicians) to direct the flow of conversation (Maireder and Ausserhofer 2014).

Twitter and the increased access to the web in the general public has reshaped the political landscape. Now politicians have a direct link through which to appeal to voters and the broader public (Graham et al. 2018). Twitter can provide a “platform for the media, political actors, and the public to communicate while also providing fodder for their communication” (McGregor et al. 2017, p. 156). Twitter influencers, like “political elites” and “journalists”, manipulate the Twitter narratives of conversation, which the public in turn shares its opinions about. In this way, politicians can also use Twitter as a tool to self-promote to the public (McGregor et al. 2017).

As testament to the rising prominence of Twitter’s role in political discussion, 87% of democratic countries’ leaders utilized Twitter by December 2012 (Graham et al. 2018). Twitter’s potential as a medium for elevating public debate between the political elites and their constituents is enormous. As for the type of discourse that the ‘digital politician’ broadcasts, the main uses of Twitter for politicians are: Self-promotion, information dissemination, negative campaigning, party mobilization, and impression management (Graham et al. 2018). Moreover, the public nature of Twitter allows politicians to broadcast messages not just to the voting public, but also to professional and traditional media outlets. This allows for public exchange between the upper tier of highly followed users like, for example, between the President, senators, athletes, and journalists (Graham et al. 2013). As a result of these unique advantages for influencers in the burgeoning age of Twitter, more and more politicians across western societies are taking advantage of the Twitter “toolkit of political communication” (Graham et al. 2013, p. 692).

This article explores the reactions to Trump’s tweets about the Russia Investigation. Before proceeding, it is important to clarify what audience is studied and how it has been defined. The concept of the Twitter ‘audience’ or ‘imagined audience’ is important to this study. The ‘imagined audience’ is the audience that Twitter writers imagine they are tweeting to (Marwick and boyd 2011). Similarly, the concept of the ‘personal public,’ refers to the ‘follower network’ that makes up the ‘meso layer’ of Twitter communication, where the ‘macro layer’ would be hashtag campaigns and the ‘micro layer’ would consist of @replies (Weller et al. 2014).

The actual audience of a tweet can extend much further than just the original ‘followers’ of the author. For example, the tweet can be shared through direct messages, retweeting, the public timeline, the search.twitter.com platform, etc. (Marwick and boyd 2011). As many accounts have privacy settings set to ‘public,’ anyone can go on the tweet sender’s page, showing how ‘indegree’ is not a reliable measure of audience (Marwick and boyd 2011). A Twitter user like Trump, for example, even has tweets republished by news media, which further extends the reach of his Twitter audience.

For the purpose of this study, we will use the term ‘audience,’ specifically to Trump’s followers who have commented on the tweets included in the sample. Trump’s imagined audience (those followers he could assume would see his tweet) include tens of millions of people, and his real audience can reach much larger figures thanks to retweets, news which republish his content, and the public nature of the Twitter platform. In this way, Trump’s personal public exceeds the meso-layer of micro-celebrity and overlaps into the macro layer of public communication. For this reason, this study will henceforth refer to Trump’s audience as those Twitter users we can confirm have seen the sample tweet, because they have commented on it using the @reply.

2. Literature Review

Donald Trump is one democratic leader who famously uses Twitter for the aforementioned purposes. Trump’s personal Twitter handle (@realDonaldTrump) “has been the main information resource chosen by the US President to generate opinion and sentiment on US civil society and has become the White House’s public diplomacy tool to have generated the most headlines in the media” (Sánchez-Giménez and Tchubykalo 2018, p. 1). The media headlines about Trump’s tweeting prove how Twitter can be a powerful tool for political communication.

As for pursuing an ongoing line of communication with the public, Trump tweeted thousands of times from his personal handle @realDonaldTrump during his first year of Presidency. In September, 2017, for example, Trump tweeted 143 times, or 9.5 times per day (Sánchez-Giménez and Tchubykalo 2018). Trump’s personal Twitter usage for diplomatic purposes is not only significant because of the personal and ongoing communication with the public, but also because it overturns “the traditional models of political communication in terms of the formality of language and the frequent use of negative sentiment” (Sánchez-Giménez and Tchubykalo 2018, p. 1). Further, of the main topics that Trump has tweeted most about as president, foreign policy counts for 20% of the total, within which the topic of Russia leads (Sánchez-Giménez and Tchubykalo 2018).

During his time as president, Donald Trump has frequently used Twitter as a platform for publicizing his stance on the Russia Investigation. Fifteen months from his presidential inauguration, Donald Trump had tweeted 150 times with the keywords ‘Russia’ or ‘Putin’ (Brown 2017). For example, on 8 May 2018, Trump tweeted, “it is the same Fake News Media that said there is ‘no path to victory for Trump’ that is now pushing the phony Russia story. A total scam!” (Trump 2017b). In April 2018, Trump tweeted about Russia 12 times.

Trump’s tweeting style has been described as “simple and repetitious,” “relying heavily on monosyllabic words,” and “overwhelmingly negative” (Ott 2017, p. 64). A critical discourse analysis on Trump’s Twitter feed from just the first month of his presidency, from 20 January 20 to 28 February 2017, revealed President Trump’s employment of Twitter as “a strategic instrument of power politics” (Kreis 2017, p. 607). It further demonstrated how President Trump propagates his political agenda and ideology by using “an informal, direct, and provoking communication style” and “positive self-presentation and negative other-presentation” on Twitter (Kreis 2017, p. 607). On the other hand, Trump’s political discourse has been characterized as populist (e.g., Lacatus 2020), with a strong affective connection with his core supporters (Rowland 2019).

Further investigations have examined the relationship between Trump’s tweeting and public opinion of him. Becker (2018) found that Trump responding via social media to Saturday Night Live (SNL) skits that poke fun at him actually helps more than hurts Trump’s public perception. According to Becker (2018), the audience who views Trump’s social media engagement in addition to the SNL skit are more likely to rate him as “authentic,” “experienced,” and “well informed” (Becker 2018). On the other hand, those same viewers rated Trump lower for the trait “honesty” (Becker 2018). Overall, Trump’s personal Twitter allows him to stick up for himself while providing his own, alternative narrative (Becker 2018). Acknowledging the power that Trump’s social media engagement can have on public opinion, our study chooses to further the research on Trump’s Twitter engagement with one of his favorite topics—the Russia Investigation.

The purpose of this study is to analyze the reaction to Trump’s repetitive tweeting about the Russia Investigation on his own public forum. We perform a qualitative content analysis of the Twitter comments made in reply to Trump’s tweets about the Russia Investigation and will be guided by the following research questions:

- RQ1: How does the Twitter community react in replies to Trump’s tweets about the Russia Investigation? Overwhelmingly positive or negative in support of Trump?

- RQ2: How has sentiment in comment replies to these tweets evolved over time?

- RQ3: What rhetoric, expressions, or ideas, if any, predominate in the comment replies?

3. Data and Method

There are more than a hundred tweets by Trump relating to the Russia Investigation. Many of those tweets contain more than 20,000 comment replies each. We employ qualitative content analysis (henceforth QCA) because it allows us to understand the range of ideas expressed in those comments. Assigning categories of pro and anti-Trump to the comments assists our content analysis, aiding us to identify trends of criticisms within the two categories of comments in the analysis. This process of coding the data and then analyzing the pattern of content and rhetoric within follows the QCA methodology.

QCA constitutes a systematic process for processing qualitative data by assigning categorical values and allows the researcher to maintain focus on the research questions by concentrating on pre-designated value categories of the data (Schreier 2012). Thus, QCA allows us to identify and understand sentiment from our sample.

To analyze the public discourse on Trump’s tweets about the Russia Investigation, this research sourced public comments made on Russia Investigation-related tweets published by the handle ‘@realDonalTrump’. Furthermore, in order to observe the evolution of comment sentiment over the duration of (1) Trump’s presidency and (2) the progress of the investigation, we have purposefully selected 4 tweets spanning the course of Trump’s first 15 months of presidency: 15 February 2017; 16 June 2017; 27 April 2018; and 7 May 2018. Each tweet must have received more than 20,000 Twitter comments, exhibiting high ‘mention’ influence. Furthermore, the sample size consists of the first 50 replies of each of the four tweets (the comment must reply @realDonaldTrump). Altogether, this makes a sum of 200 tweets, with the unit of analysis being a single tweet. This sample has been purposefully selected following a quota sampling strategy (Newbold et al. 2002). Table 1 summarizes the main dimensions of our QCA.

Table 1.

Dimensions of qualitative content analysis (QCA).

There already exists a database containing the entirety of the Twitter archive of @realDonaldTrump called ‘Trump Twitter Archive’ (Brown 2017). This database is backlogged and updated in real time, so every tweet Trump posts copies into the database within one minute of publishing. We used this database to save the archives of @reaDonaldTrump’s tweets using searches with keywords like ‘russia,’ ‘putin,’ ‘collusion,’ and ‘obstruction’. Using these keywords, we purposefully selected four tweets related to the Russia Investigation from February 2017 to May 2018.

Overall, the methodological process we have followed has involved, first, deciding on the guiding research questions and the sampling strategy. Then, we built a coding frame and performed a test-run on NVIVO. After modifying the coding frame and completing the coding process, we moved on to examining the results, and then interpreting and presenting them.

A prominent concern when using social media data for research is whether it should be considered public or private data (Townsend and Wallace 2016). Twitter is a social networking service in which users broadcast their opinions and commonly use a hashtag to associate their thoughts on a subject with users on the same subject; therefore, this data is generally referred to as ‘public data’ (Townsend and Wallace 2016). We did not collect tweets from private accounts or direct messages; therefore, ethics approval was not required, as the study only uses publicly available data.

4. Results

4.1. 15 February Comments

On 15 February, Trump tweeted “This Russian connection non-sense is merely an attempt to cover-up the many mistakes made in Hillary Clinton’s losing campaign” (Trump 2017a). By May 2018, this tweet contained more than 72,000 comment replies.

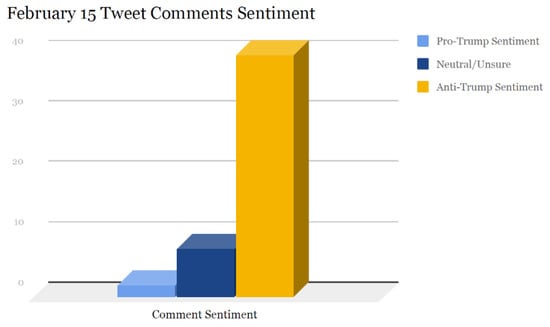

As mentioned above, we analyze a sample of the first 50 tweet comments, with each @realDonaldTrump reply counting as a single unit. Of those comments, 40 contained anti-Trump sentiment, either general or in the form of an insult. Another 8 units classified as neutral or unsure as to their meaning, and only 2 contained Pro-Trump sentiment (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

15 February tweet comments sentiment.

4.1.1. Pro-Trump Sentiment

Of the two comments coded for positive sentiment, one reflected common themes carrying over from the election: “Great job, Mr. President!! Please get a special prosecutor to get the Clinton Foundation as promised! #Lockherup #MAGA” (@allurephoto, 16 February 2017). The other comment conveyed a mixed message, where the user showed support for Trump, but expressed exasperation at a lack of action: “It’s time to do something about it! Enough talk! Find the guy/gal who has the guts to do it! Too much talk not enough action. I am 100% in POTUS corner but it’s time. Past time” (@lkw72258, 24 February 2017).

4.1.2. Anti-Trump Sentiment

Forty of the 50 comments, or 80%, in this sample coded for negative sentiment; 32 contained general criticisms, and 9 contained insults directed at President Trump. Five comments commanded or pleaded Trump to “stop”: “stop lying” (@Pvicenza, 15 February 2017; @jackschofield, 15 February 2017); “stop publicly shitting your pants via tweet” (@liberaluprising, February 17 2017); “stop deflecting” (@shewulf6, 15 February 2017); and stop corruption (@ericstwitertime, 16 February 2017). Another four comments contained references to ‘impeachment’, either in-text with messages like “you should be impeached” (@dmanteluk, 15 February 2017), or with hashtags like “#impeachmentcountdown” (@ToraWoloshin, 15 February 2017).

One of the highest frequency words in this batch was ‘truth,’ which appeared 7 times. In most contexts, users accused Trump of avoiding the truth, or warned that the truth would come to light. More than one commenter combined the previous topic of impeachment with the theme of ‘truth’: “Seriously? You are a joke and will be impeached when all the truth comes out! I will party on that day!” (@valerie2588, 20 February, 2017). Another Twitter commenter said, “and this Is an attempt by you donny to divert from the truth. You should be impeached” (@dmanteluk, 15 February 2017).

4.2. 16 June Comments

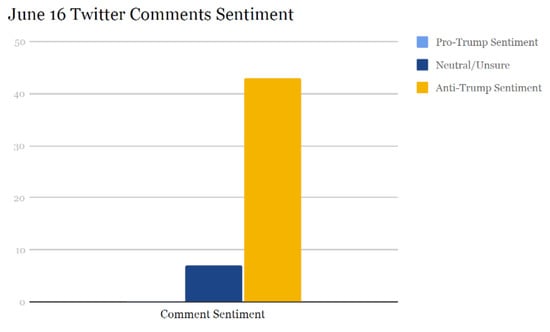

On 16 June 2017, @realDonaldTrump posted the following tweet about the ongoing Russia Investigation: “After 7 months of investigations and committee hearings about my ‘collusion with the Russians,’ nobody has been able to show any proof. Sad!” As of May 2018, this tweet received more than 30,000 replies on Twitter. Of the first 50 replies, 43 exhibited negative sentiment towards Trump, zero displayed positive sentiment, and 7 sorted as ‘Neutral’ or ‘Unsure’ (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

16 June tweet comments sentiment.

4.2.1. Pro-Trump Sentiment

Zero replies or comments qualified as positive sentiment within the ’16 June 2017 Comment’ sample subgroup.

4.2.2. Anti-Trump Sentiment

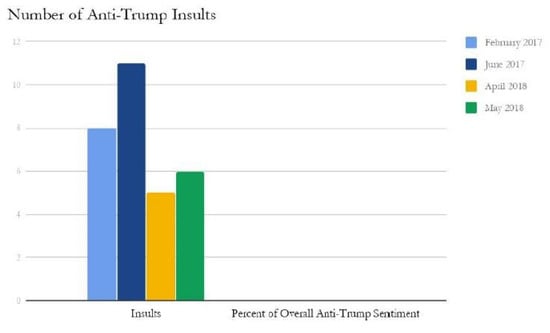

Eighty-six percent, or 43 of the 50 replies of the June sample subgroup contained Anti-Trump sentiment. Of these, 32 replies contained general criticism, and 11 contained offensive language targeting Trump himself. Of the four sample groups, this one contained the highest number of units labelled ‘insult’.

Out of the entire sample, the word ‘sad’ was recorded 7 times—6 of the 7 uses of the word ‘sad’ in the sample belonged to comments on the tweet from June 16. Significantly, @realDonaldTrump’s tweet on 16 June ends with Trump’s iconic one-word sentence: “Sad!” In the comments, Twitter users mock Trump’s use of the word. One user replies, “Another thing: It's an ONGOING INVESTIGATION you dolt. They can't talk about the evidence against you. SAD” (@meknowhu, 19 June 2017). Including the previous comment, four of the six ‘sad’ quotes are all in caps, imitating Trump’s writing style. Another user writes, “What's sad is .... America has a corrupt, moronic president. Satan himself is trying to run our country” (@suzinmill, 21 June 2017). Along with the slights ‘moronic’ and ‘dolt’ from the preceding example, the 16 June tweet comments contain many abuses. Other taunts include “stoopid” (@DeborahBogaert, 17 July 2017), “fool” (@AnnetteBridley, 17 July 2017), “Mr. Terrorist” (@MADAMPrezToYou, 19 June 2017), “Sr Clownstick” (@caschmitt, 11 July 2017), and “Liar in Chief” (@MyraDSirois1, 25 June 2017). The prevalence of offensive language in the 16 June sample demonstrates the highest levels of vitriol in the form of unconstructive criticism of the four sample subgroups.

Other words that ranked highly for this sample group include ‘proof’ and ‘evidence’. The word ‘proof’ appears 8 times in the whole sample, 7 of which occur in this subgroup. Similarly, ‘evidence’ repeats 4 times in the 16 June subgroup, but in no other subgroups of the sample. Commenters use these similar terms in reference not to the investigation lacking proof, but rather the investigation (a) providing plenty of proof or (b) doing a thorough job gathering evidence. The former can be seen in the comment, “The proof is under wraps you fool. It will come out when Mueller is ready for it to come out. You and cronies will be in handcuffs by then” (@AnnetteBridley, 17 July 2017), while the latter can be seen in the posting, “Don't worry, sir. Mueller will do a very thorough job. When all is said and done there will be plenty of proof. And you'll be in prison” (@jidk1187, 25 June 2017).

The aforementioned keywords also relate to the two most-often repeated themes of the subgroup—FBI investigator Mueller’s work in the Russia Investigation, and the then breaking news about Donald Jr.’s involvement in ‘Russiagate.’ Of the June sample subgroup, 7 comments contain references to FBI investigator Robert Mueller. The posting, “The proof is under wraps you fool. It will come out when Mueller is ready for it to come out. You and cronies will be in handcuffs by then” (@AnnetteBridley, 17 July 2017) exemplifies the general message comments that mention agent Mueller.

Donald Trump Jr., on the other hand, relates to the ‘proof’ theme in that Twitter users were alluding to Trump Jr. as a source of proof concerning the Russia Investigation. Three commenters refer to Trump Jr. as ‘Jr’, and another four allude to him as Trump’s ‘son,’ claiming that he presented evidence for the investigation. As one user replies, “Well, that problem is now solved. Your son just provided the proof. The exit door is that way Mr. President” (@mbergs12, 11 July 2017). Trump’s original tweet neither contained mentions of Mueller, nor his son Donald Jr. Combined, these two topics received 12 mentions within the June subgroup, which shows that Trump’s audience incorporates information about the Russia Investigation from other news sources in their comments.

4.3. 27 April Comments

Donald Trump’s Twitter handle, @realDonaldTrump, posted the following tweet on 27 April 2018, following the conclusion of the House Intelligence Committee investigation on the election collusion between Trump and Russia: “House Intelligence Committee rules that there was NO COLLUSION between the Trump Campaign and Russia. As I have been saying all along, it is all a big Hoax by the Democrats based on payments and lies. There should never have been a Special Counsel appointed. Witch Hunt!”

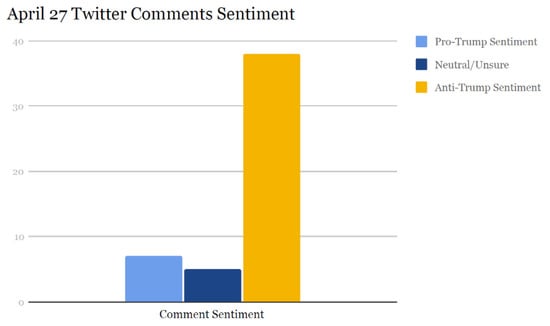

This subgroup showed a marked rise in positive sentiment, increasing to 7 pro-Trump replies from 0 in the previous sample subgroup. Anti-Trump sentiment remained most prevalent, but reduced to 38 from 43 in the previous subgroup, as represented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

27 April tweet comments sentiment.

4.3.1. Pro-Trump Sentiment

The April 27 subgroup contained the highest number of comments coded for positive sentiment, at a total of 7. Two of the comments were made by the same user, who claimed that “collusion” was a “smokescreen word,” and that the “phony DNC hack” never happened (@RealMichaelGuy, May 6 2018). Furthermore, @DebraMcCreery (29 April 2018) implied that Mueller’s “political drama” wasted taxpayers’ dollars. Yet another commenter expressed satisfaction with Trump by stating “...The cleanup from prior gov is long hard job, but needed. No wonder all the DNC is dragging feet. They know the real dirt. We are proud of you!!! Good job!!!” (@BrettPrice10, 29 April 2018). The final unique opinion expressed in the Pro-Trump sentiment node for this subgroup is that the entire investigation has been an effort “to unseat a DULY ELECTED, SITTING PRESIDENT, AKA a COUP D'ETAT. This is #TREASON” (@Trudginon1, 29 April 2018). The preceding arguments summarize the main rhetoric of comments in the April subgroup showing support for Trump or Trump’s standing in the Russia Investigation.

4.3.2. Anti-Trump Sentiment

While the April subgroup ranks highest for Pro-Trump Sentiment, it still counts 38 Anti-Trump replies (or 76%). April also contains the lowest number of comments (5) containing ‘insults’ aimed at Trump. Of the 33 general Anti-Trump replies, one-third (11) fall into one of three main categories.

Criticism in response to Trump’s tweet about the conclusion of the House investigation largely fell into three main frames: Ted Nunes and the Republicans are dishonest, the House investigation is not the only investigation, and the Mueller investigation (real investigation) will yield evidence of collusion. Correspondingly, some of the most significant keywords in the April ‘Anti-Trump node’ included ‘investigation’ (6 mentions), ‘committee’ (5 mentions), ‘Mueller’ (4 mentions), ‘collusion’ (4 mentions), Republican (4 mentions), GOP (3 mentions), and ‘Nunes’ (3 mentions). Many of the comments contain combinations of the three main argument frames (that Nunes and the GOP are untrustworthy, the House Committee investigation doesn’t count, and that the FBI investigation let by Mueller will provide ‘real’ results). For example, @Rise_and_Resis criticizes both Ted Nunes and the House Committee. Another user (@jtpillsbury, 29 April 2018) questions the validity of the House investigation and proposes the ‘real’ investigation is turning up lots of connections between Trump and Russia. Similarly, @Junerandolph (29 April 2018) calls the House investigation a ‘joke’ and declares Mueller’s investigation to be the ‘real’ one.

4.4. 7 May Comments

Finally, this study analyzed the first 50 comments listed for the tweet by @realDonaldTrump posted on 7 May 2018 insisting that Trump never colluded with Russia, nor obstructed the Russia Investigation. “The Russia Witch Hunt is rapidly losing credibility. House Intelligence Committee found No Collusion, Coordination or anything else with Russia. So now the Probe says OK, what else is there? How about Obstruction for a made up, phony crime. There is no O, it’s called Fighting Back” (Trump 2018b). In this tweet, ‘O’ signifies obstruction of justice. The tweet received more than 25,000 replies. Of the 50 coded comments, Figure 4 displays 43 replies classified as Anti-Trump sentiment, 4 as Pro-Trump sentiment, and 3 as Neutral/Unsure.

Figure 4.

7 May tweet comments sentiment.

4.4.1. Pro-Trump Sentiment

In this category, one Twitter user declares that, “No one in their right mind believes anything is real about the Russia investigation. It’s all fake” (@JTMYVA, 7 May 2018). Another user expresses the opinion that Trump is doing a great job and that “Everything is getting better FOR ALL AMERICANS !!!” (@FredLedison, 7 May 2018). @djbobbysmith (8 May 2018) loves it when Trump’s tweets anger liberals. The fourth and final user only writes “True story” in reply to Trump’s tweet about the ‘witch hunt’ (@_I_LikeTurtles, 7 May 2018).

4.4.2. Anti-Trump Sentiment

Forty-three of 50 replies were flagged for Anti-Trump sentiment in the May 2018 subgroup, including 6 tags for insults. The 7 May Anti-Trump node contained voluminous levels of unconstructive criticism. Examples of these general antagonisms include: “This is a parody account, right?” (@LauraLorio, 8 May 2018); “You have no credibility” (@marty_cusato, 7 May 2018); “As if you have a clue” (@Billthedolphin, 7 May 2018); and “Go back to golfing” (@williamjdelaney, 7 May 2018). Likewise, three commenters taunt Trump with sexual innuendos, due to Trump’s abbreviation of the word ‘obstruction’ to ‘O’. One example includes @Prof_Tweeper’s comment, “Yeah, I def believe there are “No O’s” in your life, Don. I’m sure #StormyDaniels would concur” (7 May 2018). As such, it was difficult to ascertain any thematic trends in this subgroup besides rising levels of vitriol and a number of demands for Trump’s resignation or impeachment.

Some of the keywords that appeared more times in the May subgroup than any other subgroup include ‘impeach,’ ‘guilty,’ and ‘resign’. ‘Resign’ appeared in this node four times and was used to call for Trump to step down as president, as for example: “Do Americans a big favor and RESIGN” (@animbecky, 8 May 2018). ‘Guilty’ also appears 4 times—twice alleging Trump’s guilt, and twice referring to guilty pleas already made by his members of staff. Finally, the term ‘impeach’ is twice coded in the form of a hashtag, i.e., #ImpeachTrump (@Realisticlook, 7 May 2018), and twice in-text. All four uses of the word ‘impeach’ appear not in the conditional, but in the command form or future tenses, i.e., “... WOW YOU ARE SUCH AN EMBARRASSMENT!! Looking forward to getting a smart, respectable American President, once you’ve been impeached and (fingers crossed) locked up ….” (@JulieAc45000452, 7 May 2018).

4.5. Overall

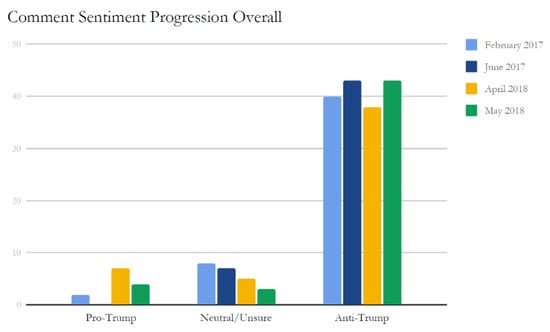

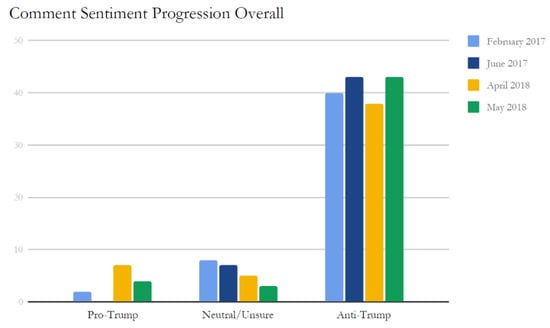

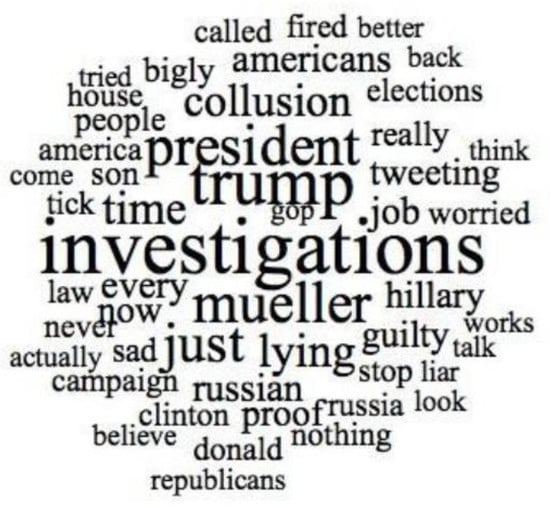

Figure 5 compares the progression of sentiment (pro-Trump, anti-Trump, and neutral/unknown) across the four subgroups, showing considerable consistency across categories. Figure 6 displays the number of Anti-Trump comments which contained insults across subgroups. Figure 7 contains a Word Cloud which illustrates the top 40 most-repeated terms across all of the subgroups and nodes. Table 2 is a table which displays the top 40 most-repeated words in table format, the terms ‘investigation’, ‘Trump’, ‘Mueller’, ‘lying’, ‘collusion’, and ‘Russian’ ranked in the top 10 most-repeated.

Figure 5.

Comment sentiment progression overall.

Figure 6.

Number of anti-Trump insults.

Figure 7.

Top 40 most-repeated terms.

Table 2.

Top 10 most-repeated terms.

Overall, it appears that Trump’s audience reacted with an overwhelmingly high Anti-Trump ratio concerning the Russia Investigation. From the period of February 2017 to May 2018, the Anti-Trump sentiment did not dip below 76%. The Anti-Trump sentiment ratio fluctuated between 76 and 86 percent, with a mode of 86% and a mean of 82%. On the other hand, the Pro-Trump sentiment within the same data set had a range between 0 and 14%, with a mean of 6%. The rest of the tweets either registered as neutral or unknown (e.g., irrelevant or bot-like content).

Some of the main themes within the anti-Trump sentiments had to do with warnings of the ‘truth’, ‘proof’, or ‘evidence’ that would jeopardize Trump’s career and position as President. In relation, the sample contained various and ample references to ‘prison,’ ‘jail,’ and other terms (e.g., ‘locked up’). These menacing tweets warned that Trump would be incarcerated and included some mentions of ‘impeachment’ (including hashtags like #ImpeachTrumpnow) for his involvement in the Russia Investigation. In fact, calls for President Trump to ‘resign’ reached an apex in the most recent of the comment subgroups.

On 18 April 2018, Trump tweeted that the Republican House Committee adjourned their investigation and did not find President Trump guilty of any wrongdoing. Not surprisingly, this subgroup displayed the highest proportion of Pro-Trump sentiment (14%). However, 76% of the subgroup comments still exhibited Anti-Trump sentiment. The comments’ themes illustrated profound distrust of the Republican party, Ted Nunes (leader of the investigation), and thus, the fairness of the investigation. Many of the audience’s comments suggested that FBI agent Mueller has enough evidence to charge Trump with ‘collusion,’ and that Mueller’s investigation is more legitimate than the House Committee’s.

In addition to the fact that the general trend did not illustrate a substantial increase in Pro-Trump sentiment, nor a stable decrease in Anti-Trump sentiment, it cannot be said that Trump’s consistent tweeting about the Russia Investigation has swayed his Twitter audience’s opinion about his participation in colluding with the Russian government. In fact, comments often included information about the ongoing investigation that was not revealed by Trump himself (e.g., updates about Mueller’s investigation and mentions of Trump Junior’s involvement). From this, we deduce that these aforementioned audience members’ opinions are more influenced by external sources (e.g., mass media) than the statements, claims, and arguments expressed in Trump’s ongoing tweets.

The high levels of negativity in the results correspond with the findings of Ott (2017), who suggests that “‘negative sentiment’ is the key to popularity on Twitter” and concludes that “Twitter breeds dark, degrading, and dehumanizing discourse; it breeds vitriol and violence; in short, it breeds Donald Trump” (Ott 2017, p. 62). Hence, our findings of overwhelming negativity and vitriol are consistent with Ott’s (2017) conclusions about the politics of Twitter and Trump.

5. Conclusions

The main purpose of this study was to gain insight into public opinion about the Russia Investigation through the lens of Trump’s Twitter audience. Our research shows that his audience responded with overwhelmingly Anti-Trump sentiment across all sample subgroups. There was not a significant increase or decrease in Anti-Trump rhetoric over the time period of the sample universe (February, 2017 to May 2018). Anti-Trump sentiment did not deviate more than 6% from the mean of 82% in any subgroup. These results are significant for several reasons. Firstly, they highlight the Russia Investigation as a blemish on Trump’s presidency. Furthermore, they shed light on the degree of mistrust and suspicion that the Twitter public displays about Trump’s involvement in the Russia scandal. Trump, who has faced interrogation about the Russia Investigation by the mass media, readily and frequently tweets about his own position on the Russia Investigation. Some examples of his favored themes include his insistence upon his own innocence, the caricature of the investigation as a Democrat-led witch-hunt, and the House Intelligence Committee’s dismissal of Trump’s involvement in any collusion with Russia. Despite Trump’s persistent tweeting about these issues, the sentiment in the responses examined in this study do not show any measure of movement in his favor. Therefore, this investigation reveals that Trump’s words (tweets) do not inform his Twitter audience’s opinion on this matter. Rather, his political discourse might be characterized as populist, and its main function seems to be to catch emotional attention and not to inform. Finally, this study concludes that Trump’s repetition of catchphrases and stock-themes on the Russia Investigation did not have a measurable impact on his Twitter audience’s responses over the sample.

Researchers have found Twitter promotes negative discourse concerning social and political issues, or what Ott (2017) describes as “public discourse that is simple, impetuous, and frequently denigrating and dehumanizing” (Ott 2017, p. 60). It is possible that public replies to Trump’s tweets could exhibit higher levels of negativity than would be reflected in the general public, depending on who his audience is and how politically active they are on the Twitter platform. Studies that have attempted to analyze Twitter data as a reflection of public opinion and in assessing ‘sentiment’ have been criticized for a lack of theoretical underpinning. (Jungherr et al. 2017; Margolin et al. 2016; McGregor et al. 2017). Because of these criticisms, our research does not intend to extrapolate results from Twitter data to the general public, but rather use the data to gain insight on which views and opinions are expressed by the politically active Twitter users of Trump’s audience and how they might have evolved as the Russia Investigation (and Trump’s tweeting) has progressed. Equally, it is important to keep in mind that the Twitter user base is not a perfect representation of the US population, or others, as a whole.

Researchers are hard at work trying to unravel the meaning and consequences of social media usage within politics. How politicians like Trump tweet, what message they broadcast, and how the public reacts is of great significance in our time. It is also true that the public engages and reacts within the same online social forums—but to what effect? Moving forward, we propose a broader study that evaluates the sentiment of a wider sample of President Trump’s Twitter audience, as well as compares comment replies across a spectrum of topics. Such data might provide noteworthy insights for the area of research which uses social media as a complementary tool for traditional public opinion polls. Moreover, such studies could add to the body of work which analyses the implications of social media like Twitter for the future of politics, elections, and voting.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.R.-C. and A.Y.; methodology, C.R.-C.; software, A.Y.; validation, A.Y.; formal analysis, C.R.-C. and A.Y.; investigation, C.R.-C.; resources, A.Y.; data curation, A.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, C.R.-C. and A.Y.; writing—review and editing, C.R.-C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Becker, Amy B. 2018. Live from New York, It’s Trump on Twitter! The Effect of Engaging With Saturday Night Live on Perceptions of Authenticity and the Salience of Trait Ratings. International Journal of Communication 12: 22. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Brendan. 2017. Trump Twitter Archive. Available online: http://www.trumptwitterarchive.com/ (accessed on 9 November 2020).

- Graham, Todd, Marcel Broersma, Karin Hazelhoff, and Guido vant Haar ’. 2013. Between broadcasting political messages and interacting with voters: The use of Twitter during the 2010 UK general election campaign. Information, Communication & Society 16: 692–716. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, Todd, Daniel Jackson, and Marcel Broersma. 2018. The Personal in the Political on Twitter: Towards a Typology of Politicians’ Personalized Tweeting Behaviours. In Managing Democracy in the Digital Age. Edited by Julia Schwanholz, Todd Graham and Peter-Tobias Stoll. Cham: Springer, pp. 137–57. [Google Scholar]

- Jungherr, Andreas, Harald Schoen, Oliver Posegga, and Pascal Jürgens. 2017. Digital trace data in the study of public opinion: An indicator of attention toward politics rather than political support. Social Science Computer Review 35: 336–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreis, Ramona. 2017. The “Tweet Politics” of President Trump. Journal of Language and Politics 16: 607–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacatus, Corina. 2020. Populism and President Trump’s approach to foreign policy: An analysis of tweets and rally speeches. Politics. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maireder, Axel, and Julian Ausserhofer. 2014. Political discourse on Twitter: Networking topics, objects and people". In Twitter and Society. Edited by Weller Katrin, Axel Bruns, Jean Burgess, Merja Mahrt and Cornelius Puschmann. New York: Peter Lang, pp. 291–341. [Google Scholar]

- Drew B. Margolin, Drew B., Sasha Goodman, Brian Keegan, Yu-Ru Lin, and David Lazer. 2016. Wiki-worthy: Collective judgment of candidate notability. Information, Communication & Society 19: 1029–45. [Google Scholar]

- Marwick, Alice E., and danah boyd. 2011. I tweet honestly, I tweet passionately: Twitter users, context collapse, and the imagined audience. New Media & Society 13: 114–33. [Google Scholar]

- McGregor, Shannon C., Rachel R. Mourão, and Logan Molyneux. 2017. Twitter as a tool for and object of political and electoral activity: Considering electoral context and variance among actors. Journal of Information Technology & Politics 14: 154–67. [Google Scholar]

- Newbold, Chris, Oliver Boyd-Barrett, and Hilde Van den Bulck. 2002. The Media Book. London: Arnold Hodder Headline. [Google Scholar]

- Ott, Brian L. 2017. The age of Twitter: Donald J. Trump and the politics of debasement. Critical Studies in Media Communication 34: 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowland, Robert C. 2019. The Populist and Nationalist Roots of Trump’s Rhetoric. Rhetoric and Public Affairs 22: 343–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Giménez, Juan A., and Evgueni Tchubykalo. 2018. Donald Trump’s Twitter Account: A Brief Content Analysis. Elcano Royal Institute. Available online: http://www.realinstitutoelcano.org/wps/portal/rielcano_en/contenido?WCM_GLOBAL_CONTEXT=/elcano/elcano_in/zonas_in/ari20-2018-sanchezgimenez-tchubykalo-realdonaldtrump-a-brie f-content-analysis (accessed on 9 November 2020).

- Schreier, Margrit. 2012. Qualitative Content Analysis in Practice. Los Angeles: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Townsend, Leanne, and Claire Wallace. 2016. Social Media Research: A Guide to Ethics. University of Aberdeen. Available online: www.gla.ac.uk/media/media_487729_en.pdf (accessed on 9 November 2020).

- Trump, Donald J. 2017a. [realDonaldTrump]. This Russian Connection Non-Sense Is Merely an Attempt to Cover-Up the Many Mistakes Made in Hillary Clinton’s Losing Campaign. [Tweet]. Available online: https://twitter.com/realdonaldtrump/status/831837514226921472 (accessed on 9 November 2020).

- Trump, Donald J. 2017b. [realDonaldTrump]. It Is the Same Fake News Media that Said There Is “No Path to Victory for Trump” That Is Now Pushing the Phony Russia Story. A Total Scam! [Tweet]. Available online: https://twitter.com/realdonaldtrump/status/848158641056362496 (accessed on 9 November 2020).

- Trump, Donald J. 2017c. [realDonaldTrump]. After 7 Months of Investigations & Committee Hearings about My “Collusion with the Russians”, Nobody Has Been able to Show Any Proof. Sad! [Tweet]. Available online: https://twitter.com/realdonaldtrump/status/875682853585129472 (accessed on 9 November 2020).

- Trump, Donald J. 2018a. [realDonaldTrump]. House Intelligence Committee Rules that There Was NO COLLUSION between the Trump Campaign and Russia. As I have been...[Tweet]. Available online: https://twitter.com/realdonaldtrump/status/990049088375836672 (accessed on 9 November 2020).

- Trump, Donald J. 2018b. [realDonaldTrump]. The Russia Witch Hunt is Rapidly Losing Credibility. House Intelligence Committee found No Collusion, Coordination…[Tweet]. Available online: https://twitter.com/realdonaldtrump/status/993452275648679938 (accessed on 9 November 2020).

- Weller, Katrin, Axel Bruns, Jean Burgess, Merja Mahrt, and Cornelius Puschmann. 2014. Twitter and Society. New York: Peter Lang Publishing Group. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).