Racial Discrimination Stress, School Belonging, and School Racial Composition on Academic Attitudes and Beliefs among Black Youth

Abstract

1. Theoretical Framework

2. Racial Discrimination Stress as a Risk Factor

3. School Belonging as a Protective Factor

4. Racial Discrimination, School Belonging, and School Racial Composition

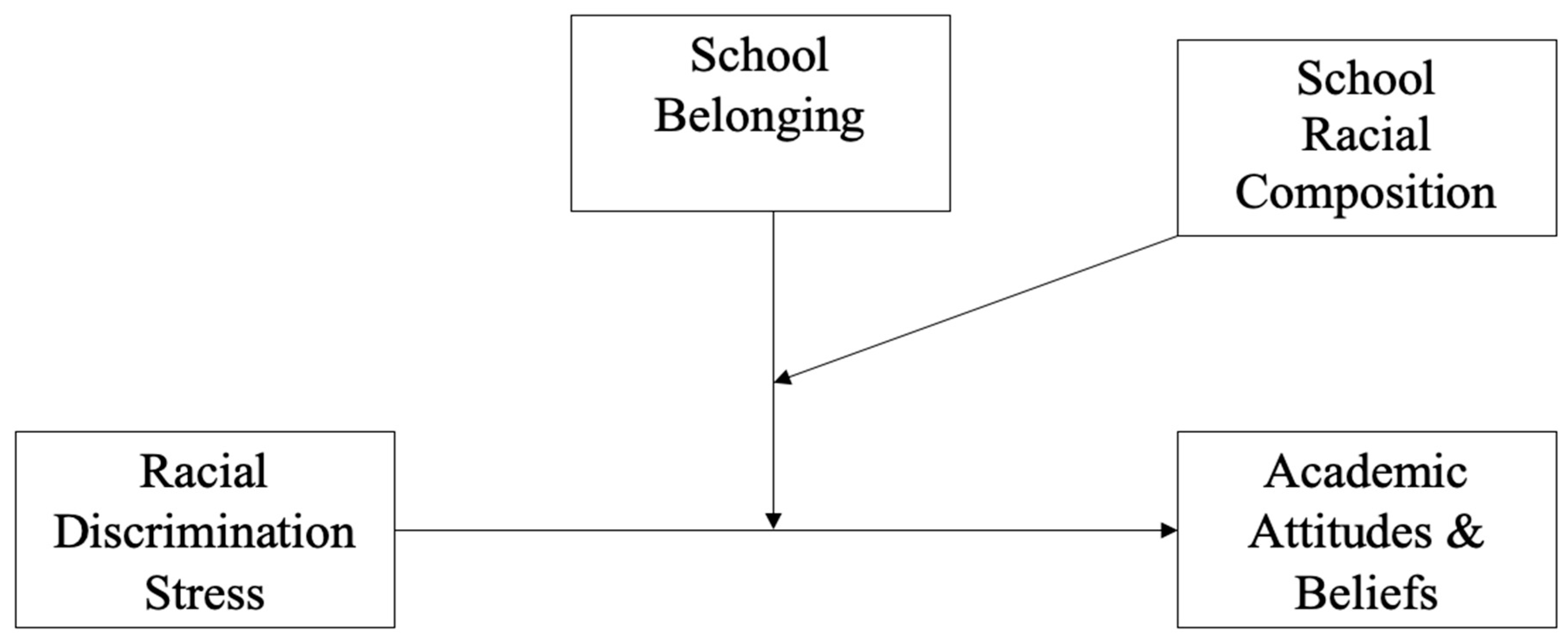

5. The Current Study

6. Method

6.1. Participants

6.2. Procedure

6.3. Measures

6.3.1. Demographic Information

6.3.2. Racial Discrimination Stress

6.3.3. School Belonging

6.3.4. School Racial Composition

6.3.5. Academic Competence

6.3.6. Academic Efficacy

6.3.7. Academic Skepticism

6.3.8. Covariates

6.4. Analytic Approach

7. Results

7.1. Descriptives and Correlations

7.2. Academic Competence

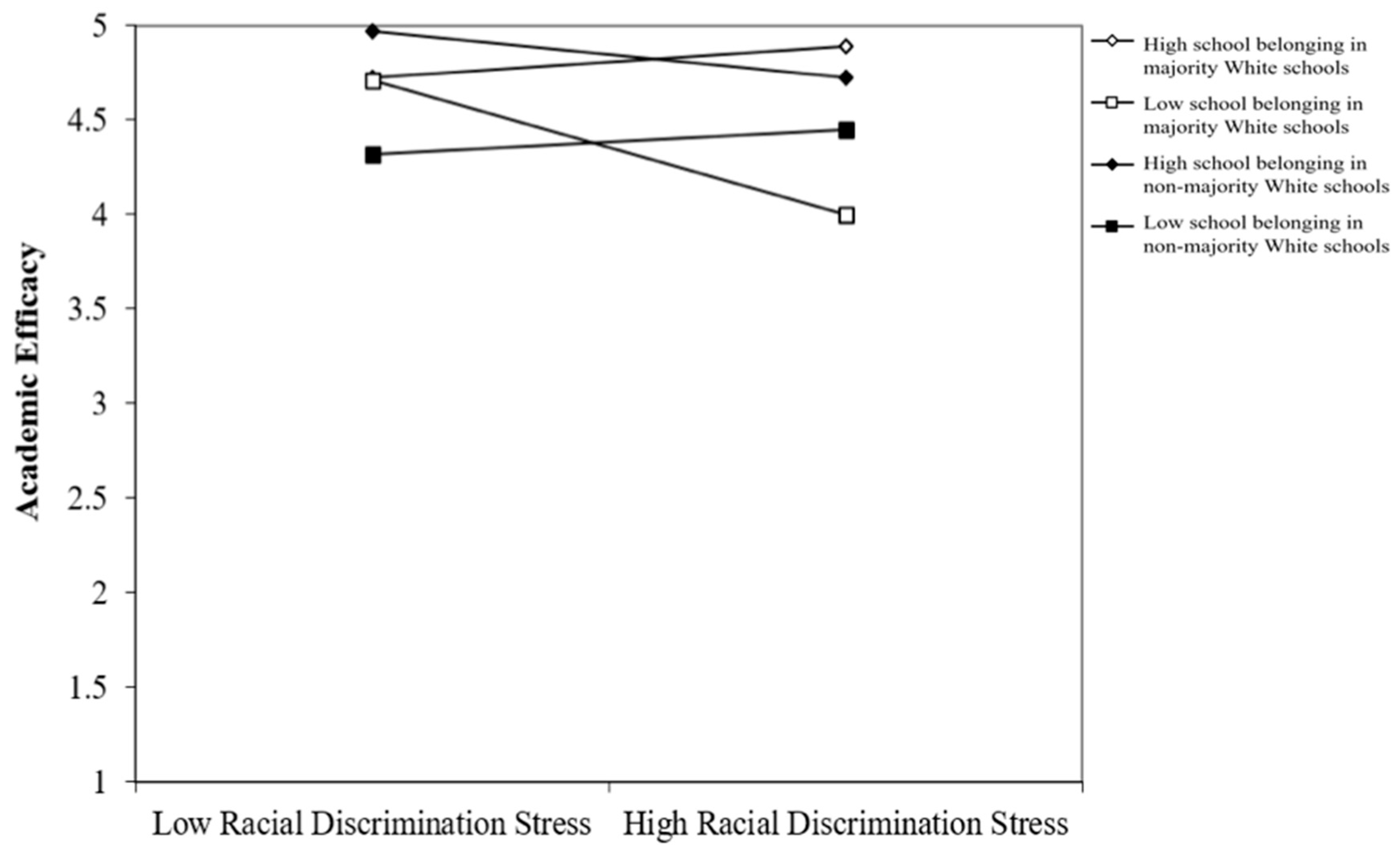

7.3. Academic Efficacy

7.4. Academic Skepticism

8. Discussion

8.1. Racial Discrimination Stress on Academic Attitudes and Beliefs

8.2. School Belonging Promotes Positive Academic Attitudes and Beliefs

8.3. School Belonging as a Buffer in Majority White Schools

8.4. Limitations and Future Directions

8.5. Theoretical Implications

8.6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Agyemang, Charles. 2005. Negro, Black, Black African, African Caribbean, African American or What? Labelling African Origin Populations in the Health Arena in the 21st Century. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health 59: 1014–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, Quaylan. 2013. ‘They Think Minority Means Lesser Than’: Black Middle-Class Sons and Fathers Resisting Microaggressions in the School. Urban Education 48: 171–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assari, Shervin, Ritesh Mistry, and Cleopatra Caldwell. 2018. Perceived Discrimination and Substance Use among Caribbean Black Youth; Gender Differences. Brain Sciences 8: 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, Meeta, Christy Byrd, and Stephanie Rowley. 2018. The Relationships of School-Based Discrimination and Ethnic-Racial Socialization to African American Adolescents’ Achievement Outcomes. Social Sciences 7: 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartneck, Christoph, Andreas Duenser, Elena Moltchanova, and Karolina Zawieska. 2015. Comparing the Similarity of Responses Received from Studies in Amazon’s Mechanical Turk to Studies Conducted Online and with Direct Recruitment.” Edited by Martin Voracek. PLoS ONE 10: e0121595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bondy, Jennifer M., Anthony A. Peguero, and Brent E. Johnson. 2017. The Children of Immigrants’ Academic Self-Efficacy: The Significance of Gender, Race, Ethnicity, and Segmented Assimilation. Education and Urban Society 49: 486–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booker, Keonya Charlyn. 2004. Exploring School Belonging and Academic Achievement in African American Adolescents. Curriculum & Teaching Dialogue 6: 131–43. Available online: https://web-b-ebscohost-com.ezproxy1.lib.asu.edu/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=1&sid=2792f441-f949-43cf-a4a5-23a45a8e9973%40sessionmgr101 (accessed on 16 April 2020).

- Booker, Keonya Charlyn. 2006. School Belonging and the African American Adolescent: What Do We Know and Where Should We Go? The High School Journal 89: 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottiani, Jessika H., Catherine P. Bradshaw, and Tamar Mendelson. 2017. A Multilevel Examination of Racial Disparities in High School Discipline: Black and White Adolescents’ Perceived Equity, School Belonging, and Adjustment Problems. Journal of Educational Psychology 109: 532–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bower, Kelly M., Roland J. Thorpe, Jr., Charles Rohde, and Darrell J. Gaskin. 2014. The Intersection of Neighborhood Racial Segregation, Poverty, and Urbanicity and its Impact on Food Store Availability in the United States. Preventive Medicine 58: 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, Barbara T., James P. Comer, and David J. Johns. 2018. Addressing the African American Achievement Gap: Three Leading Educators Issue a Call to Action. YC Young Children 73: 14–23. Available online: https://www.naeyc.org/resources/pubs/yc/may2018/positive-early-math-af-am-boys (accessed on 16 April 2020).

- Briley, Daniel A., Matthew Domiteaux, and Elliot M. Tucker-Drob. 2014. Achievement-Relevant Personality: Relations with the Big Five and Validation of an Efficient Instrument. Learning and Individual Differences 32: 26–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Tiffany L., Miriam R. Linver, Melanie Evans, and Donna DeGennaro. 2009. African–American Parents’ Racial and Ethnic Socialization and Adolescent Academic Grades: Teasing Out the Role of Gender. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 38: 214–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryan, Julia, Joseph M. Williams, Jungnam Kim, Stephaney S. Morrison, and Cleopatra H. Caldwell. 2018. Perceived Teacher Discrimination and Academic Achievement among Urban Caribbean Black and African American Youth: School Bonding and Family Support as Protective Factors. Urban Education 1: 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler-Barnes, Sheretta T., Lorena Estrada-Martinez, Rosa J. Colin, and Brittni D. Jones. 2015. School and Peer Influences on the Academic Outcomes of African American Adolescents. Journal of Adolescence 44: 168–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, Robert T. 2007. Racism and Psychological and Emotional Injury: Recognizing and Assessing Race-Based Traumatic Stress. The Counseling Psychologist 35: 13–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, Robert T., and Amy L. Reynolds. 2011. Race-Related Stress, Racial Identity Status Attitudes, and Emotional Reactions of Black Americans. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology 17: 156–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, Prudence L., Kevin Grant Welner, and Gloria Ladson-Billings, eds. 2013. Closing the Opportunity Gap: What America Must Do to Give Every Child an Even Chance. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cernkovich, Stephen A., and Peggy C. Giordano. 1992. School Bonding, Race, and Delinquency. Criminology 30: 261–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavous, Tabbye M., Debra Hilkene Bernat, Karen Schmeelk-Cone, Cleopatra H. Caldwell, Laura Kohn-Wood, and Marc A. Zimmerman. 2003. Racial Identity and Academic Attainment Among African American Adolescents. Child Development 74: 1076–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavous, Tabbye M., Deborah Rivas-Drake, Ciara Smalls, Tiffany Griffin, and Courtney Cogburn. 2008. Gender Matters, Too: The Influences of School Racial Discrimination and Racial Identity on Academic Engagement Outcomes among African American Adolescents. Developmental Psychology 44: 637–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, James S. 1966. Equality of Educational Opportunity [Summary Report]; Washington, DC: US Department of Health, Education, Welfare: Office of Education, vol. 2.

- Conway-Turner, Jameela, Joseph Williams, and Adam Winsler. 2020. Does Diversity Matter? School Racial Composition and Academic Achievement of Students in a Diverse Sample. Urban Education 0: 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crabtree, Lenora M., Sonyia C. Richardson, and Chance W. Lewis. 2019. The Gifted Gap, STEM Education, and Economic Immobility. Journal of Advanced Academics 30: 203–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, Michelle T. 2014. Social Connectedness and Self-Esteem: Predictors of Resilience in Mental Health among Maltreated Homeless Youth. Issues in Mental Health Nursing 35: 212–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danoff-Burg, Sharon, Hazel M. Prelow, and Rebecca R. Swenson. 2004. Hope and Life Satisfaction in Black College Students Coping with Race-Related Stress. Journal of Black Psychology 30: 208–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis-Kean, Pamela E. 2005. The Influence of Parent Education and Family Income on Child Achievement: The Indirect Role of Parental Expectations and the Home Environment. Journal of Family Psychology 19: 294–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doll, Jonathan Jacob, Zohreh Eslami, and Lynne Walters. 2013. Understanding why Students Drop Out of High School, According to Their Own Reports: Are They Pushed or Pulled, or do They Fall Out? A comparative analysis of seven nationally representative studies. Sage Open 3: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doménech-Betoret, Fernando, Laura Abellán-Roselló, and Amparo Gómez-Artiga. 2017. Self-Efficacy, Satisfaction, and Academic Achievement: The Mediator Role of Students’ Expectancy-Value Beliefs. Frontiers in Psychology 8: 1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dotterer, Aryn M., and Elizabeth Wehrspann. 2016. Parent Involvement and Academic Outcomes among Urban Adolescents: Examining the Role of School Engagement. Educational Psychology 36: 812–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fine, Michelle. 1986. Why Urban Adolescents Drop into and Out of Public High School. Teachers College Record 87: 393–409. Available online: https://www.karolinetrepper.com/s/Fine-Why-Students-Drop-Out-of-HS.pdf (accessed on 16 April 2020).

- Ford, Donna Y., Tarek C. Grantham, and Gilman W. Whiting. 2008. Another Look at the Achievement Gap: Learning from the Experiences of Gifted Black Students. Urban Education 43: 216–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillen-O’Neel, Cari, and Andrew Fuligni. 2013. A Longitudinal Study of School Belonging and Academic Motivation Across High School. Child Development 84: 678–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodenow, Carol, and Kathleen E. Grady. 1993. The Relationship of School Belonging and Friends’ Values to Academic Motivation Among Urban Adolescent Students. The Journal of Experimental Education 62: 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, DeLeon L., Elan C. Hope, and Jamaal S. Matthews. 2018. Black and Belonging at School: A Case for Interpersonal, Instructional, and Institutional Opportunity Structures. Educational Psychologist 53: 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, Anne, Russell J. Skiba, and Pedro A. Noguera. 2010. The Achievement Gap and the Discipline Gap: Two Sides of the Same Coin? Educational Researcher 39: 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutman, Leslie Morrison, and Carol Midgley. 2000. The Role of Protective Factors in Supporting the Academic Achievement of Poor African American Students During the Middle School Transition. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 29: 223–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrell, Shelly P. 1994. The Racism and Life Experience Scales. Unpublished Manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Harrell, Shelly P. 1997. Development and Validation of Scales to Measure Racism-Related Stress. Paper presented at the 6th Biennial Conference of the Society for Community Research and Action, Columbia, SC, USA, May 28–31. [Google Scholar]

- Harrell, Shelly P. 2000. A Multidimensional Conceptualization of Racism-Related Stress: Implications for the Well-Being of People of Color. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 70: 42–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris-Britt, April, Cecelia R. Valrie, Beth Kurtz-Costes, and Stephanie J. Rowley. 2007. Perceived Racial Discrimination and Self-Esteem in African American Youth: Racial Socialization as a Protective Factor: Perceived Racial Discrimination and Self-Esteem. Journal of Research on Adolescence 17: 669–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harter, Susan. 1982. The Perceived Competence Scale for Children. Child Development 53: 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honora, Detris. 2003. Urban African American Adolescents and School Identification. Urban Education 38: 58–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson-Ahorlu, Robin Nicole. 2013. Our Biggest Challenge Is Stereotypes’: Understanding Stereotype Threat and the Academic Experiences of African American Undergraduates. The Journal of Negro Education 82: 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jose, Paul E., Nicholas Ryan, and Jan Pryor. 2012. Does Social Connectedness Promote a Greater Sense of Well-Being in Adolescence Over Time? Journal of Research on Adolescence 22: 235–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, Hilary D., and Theresa J. Early. 2014. The Impact of School Connectedness and Teacher Support on Depressive Symptoms in Adolescents: A Multilevel Analysis. Children and Youth Services Review 39: 101–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keselman, Harvey Jay, Charles W. Miller, and Burt Holland. 2011. Many Tests of Significance: New Methods for Controlling Type I Errors. Psychological Methods 16: 420–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lanier, Yzette, Marilyn S. Sommers, Jason Fletcher, Madeline Y. Sutton, and Debra D. Roberts. 2017. Examining Racial Discrimination Frequency, Racial Discrimination Stress, and Psychological Well-Being Among Black Early Adolescents. Journal of Black Psychology 43: 219–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Talisha, Dewey Cornell, Anne Gregory, and Xitao Fan. 2011. High Suspension Schools and Dropout Rates for Black and White Students. Education and Treatment of Children 34: 167–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libbey, Heather P. 2004. Measuring Student Relationships to School: Attachment, Bonding, Connectedness, and Engagement. Journal of School Health 74: 274–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masten, Ann S., Janette E. Herbers, J. J. Cutuli, and Theresa L. Lafavor. 2008. Promoting Competence and Resilience in the School Context. Professional School Counseling 12: 2156759x0801200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, Jamaal Sharif. 2020. Formative Learning Experiences of Urban Mathematics Teachers’ and Their Role in Classroom Care Practices and Student Belonging. Urban Education 55: 507–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClain, Shannon, Samuel T. Beasley, Bianca Jones, Olufunke Awosogba, Stacey Jackson, and Kevin Cokley. 2016. An Examination of the Impact of Racial and Ethnic Identity, Impostor Feelings, and Minority Status Stress on the Mental Health of Black College Students. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development 44: 101–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, Susan D., Jamie Wernsman, and Dale S. Rose. 2009. The Relation of Classroom Environment and School Belonging to Academic Self-Efficacy among Urban Fourth- and Fifth-Grade Students. The Elementary School Journal 109: 267–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midgley, Carol, Martin L. Maehr, Ludmila Z. Hruda, Eric Anderman, Lynley Anderman, Kimberley E. Freeman, and T. Urdan. 2000. Manual for the Patterns of Adaptive Learning Scales. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan. [Google Scholar]

- Napoli, Maria, Flavio Francisco Marsiglia, and Stephen Kulis. 2003. Sense of Belonging in School as a Protective Factor Against Drug Abuse Among Native American Urban Adolescents. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions 3: 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Center for Education Statistics. 2019a. Degrees Awarded. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/programs/raceindicators/indicator_ree.asp (accessed on 5 October 2020).

- National Center for Education Statistics. 2019b. Mathematics Achievement. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/programs/raceindicators/indicator_RCB.asp (accessed on 20 October 2020).

- National Center for Education Statistics. 2019c. Reading Achievement. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/programs/raceindicators/indicator_RCA.asp (accessed on 20 October 2020).

- National Center for Education Statistics. 2019d. Retention, Suspension, and Expulsion. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/programs/raceindicators/indicator_RDA.asp (accessed on 5 October 2020).

- Neblett, Enrique W., Cheri L. Philip, Courtney D. Cogburn, and Robert M. Sellers. 2006. African American Adolescents’ Discrimination Experiences and Academic Achievement: Racial Socialization as a Cultural Compensatory and Protective Factor. Journal of Black Psychology 32: 199–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, Veronica A., and J. S. Onésimo Sandoval. 2015. Educational Expectations Among African American Suburban Low to Moderate Income Public High School Students. Journal of African American Studies 19: 135–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterman, Karen F. 2000. Students’ Need for Belonging in the School Community. Review of Educational Research 70: 323–67. Available online: http://www.jstor.com/stable/1170786 (accessed on 16 April 2020). [CrossRef]

- Parker, James D.A., Laura J. Summerfeldt, Marjorie J. Hogan, and Sarah A. Majeski. 2004. Emotional Intelligence and Academic Success: Examining the Transition from High School to University. Personality and Individual Differences 36: 163–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittman, Laura D., and Adeya Richmond. 2007. Academic and Psychological Functioning in Late Adolescence: The Importance of School Belonging. The Journal of Experimental Education 75: 270–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Respress, Brandon N., Eusebius Small, Shelley A. Francis, and David Cordova. 2013. The Role of Perceived Peer Prejudice and Teacher Discrimination on Adolescent Substance Use: A Social Determinants Approach. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse 12: 279–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, Amy L., Jacob N. Sneva, and Gregory P. Beehler. 2010. The Influence of Racism-Related Stress on the Academic Motivation of Black and Latino/a Students. Journal of College Student Development 51: 135–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, Chad A., Cynthia G. Simpson, and Aaron Moss. 2015. The Bullying Dynamic: Prevalence of Involvement among a Large-Scale Sample of Middle and High School Youth with and without Disabilities: The Bullying Dynamic. Psychology in the Schools 52: 515–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbloom, Susan Rakosi, and Niobe Way. 2004. Experiences of Discrimination among African American, Asian American, and Latino Adolescents in an Urban High School. Youth & Society 35: 420–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatine, Elaina, Melissa Lippold, and Kirsten Kainz. 2017. The Unique and Interactive Effects of Parent and School Bonds on Adolescent Delinquency. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology 53: 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Sánchez, Bernadette, Yarí Colón, and Patricia Esparza. 2005. The Role of Sense of School Belonging and Gender in the Academic Adjustment of Latino Adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 34: 619–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, Lionel D. 2004. Correlates of Coping with Perceived Discriminatory Experiences among African American Adolescents. Journal of Adolescence 27: 123–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seaton, Eleanor K. 2010. What the Achievement Gap Conversation Is Missing. The Review of Black Political Economy 37: 275–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seaton, Eleanor K., and Sara Douglass. 2014. School Diversity and Racial Discrimination among African-American Adolescents. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology 20: 156–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seaton, Eleanor K., and Masumi Iida. 2019. Racial Discrimination and Racial Identity: Daily Moderation among Black Youth. American Psychologist 74: 117–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seaton, Eleanor K., and Karolyn Tyson. 2019. The Intersection of Race and Gender Among Black American Adolescents. Child Development 90: 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seaton, Eleanor K., and Tiffany Yip. 2009. School and Neighborhood Contexts, Perceptions of Racial Discrimination, and Psychological Well-Being Among African American Adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 38: 153–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seaton, Eleanor K., Cleopatra H. Caldwell, Robert M. Sellers, and James S. Jackson. 2008. The Prevalence of Perceived Discrimination among African American and Caribbean Black Youth. Developmental Psychology 44: 1288–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seaton, Eleanor K., Enrique W. Neblett, Rachel D. Upton, Wizdom Powell Hammond, and Robert M. Sellers. 2011. The Moderating Capacity of Racial Identity Between Perceived Discrimination and Psychological Well-Being Over Time Among African American Youth: Discrimination and Well-Being. Child Development 82: 1850–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seaton, Eleanor K., Rachel Upton, Adrianne Gilbert, and Vanessa Volpe. 2014. A Moderated Mediation Model: Racial Discrimination, Coping Strategies, and Racial Identity Among Black Adolescents. Child Development 85: 882–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sikkink, David, and Michael O. Emerson. 2008. School Choice and Racial Segregation in US Schools: The Role of Parents’ Education. Ethnic and Racial Studies 31: 267–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, Kusum, Mido Chang, and Sandra Dika. 2010. Ethnicity, Self-Concept, and School Belonging: Effects on School Engagement. Educational Research for Policy and Practice 9: 159–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slaten, Christopher D., Jonathan K. Ferguson, Kelly-Ann Allen, Dianne-Vella Brodrick, and Lea Waters. 2016. School Belonging: A Review of the History, Current Trends, and Future Directions. The Educational and Developmental Psychologist 33: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solórzano, Daniel, Miguel Ceja, and Tara Yosso. 2000. Critical Race Theory, Racial Microaggressions, and Campus Racial Climate: The Experiences of African American College Students. Journal of Negro Education 69: 60–73. Available online: http://www.jstor.com/stable/2696265 (accessed on 16 April 2020).

- Spencer, Margaret Beale, Davido Dupree, and Tracey Hartmann. 1997. A Phenomenological Variant of Ecological Systems Theory (PVEST): A Self-Organization Perspective in Context. Development and Psychopathology 9: 817–33. Available online: http://repository.upenn.edu/gse_pubs/4 (accessed on 16 April 2020). [CrossRef]

- Spencer, Margaret Beale, Suzanne Fegley, Vinay Harpalani, and Gregory Seaton. 2004. Understanding Hypermasculinity in Context: A Theory-Driven Analysis of Urban Adolescent Males’ Coping Responses. Research in Human Development 1: 229–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens-Watkins, Danelle, Lynda Brown-Wright, and Kenneth Tyler. 2011. Brief Report: The Number of Sexual Partners and Race-Related Stress in African American Adolescents: Preliminary Findings. Journal of Adolescence 34: 191–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stroud, Molly, Steven. R. Asher, and Kristina. L. McDonald. 2009. Assessing School Belongingness and its Associations with Loneliness, Peer Acceptance, and Perceived Popularity. Paper presented at the Meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development, Denver, CO, USA, April 2–4. [Google Scholar]

- Swanson, Dena Phillips, Michael Cunningham, Joseph Youngblood, and Margaret Beale Spencer. 2009. Racial identity development during childhood. In Handbook of African American Psychology. Edited by Helen A. Neville, Brendesha M. Tynes and Shawn O. Utsey. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, pp. 269–81. [Google Scholar]

- Swim, Janet K., Lauri L. Hyers, Laurie L. Cohen, Davita C. Fitzgerald, and Wayne H. Bylsma. 2003. African American College Students’ Experiences with Everyday Racism: Characteristics of and Responses to These Incidents. Journal of Black Psychology 29: 38–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, Oseela N., Cleopatra Howard Caldwell, Nkesha Faison, and James S. Jackson. 2009. Promoting Academic Achievement: The Role of Racial Identity in Buffering Perceptions of Teacher Discrimination on Academic Achievement among African American and Caribbean Black Adolescents. Journal of Educational Psychology 101: 420–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, Aisha R., and Anne Gregory. 2011. Examining the Influence of Perceived Discrimination During African American Adolescents’ Early Years of High School. Education and Urban Society 43: 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tynes, Brendesha M., Eleanor K. Seaton, and Allana Zuckerman. 2015. Online Racial Discrimination: A Growing Problem for Adolescents. Psychological Science Agenda. Available online: http://www.apa.org/science/about/psa/2015/12/online-racial-discrimination.aspx (accessed on 16 April 2020).

- Ueno, Koji. 2009. Same-Race Friendships and School Attachment: Demonstrating the Interaction Between Personal Network and School Composition. Sociological Forum 24: 515–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uwah, Chinwé J., H. George McMahon, and Carolyn F. Furlow. 2008. School Belonging, Educational Aspirations, and Academic Self-Efficacy among African American Male High School Students: Implications for School Counselors. Professional School Counseling 11. Available online: http://www.academia.edu/download/35012274/Uwah_McM_Furlow_Ed_Aspirations.pdf (accessed on 16 April 2020). [CrossRef]

- Wang, Ming-Te, and James P. Huguley. 2012. Parental Racial Socialization as a Moderator of the Effects of Racial Discrimination on Educational Success Among African American Adolescents: Racial Socialization, Discrimination, and Education. Child Development 83: 1716–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Meifen, P. Paul Heppner, Tsun-Yao Ku, and Kelly Yu-Hsin Liao. 2010. Racial Discrimination Stress, Coping, and Depressive Symptoms among Asian Americans: A Moderation Analysis. Asian American Journal of Psychology 1: 136–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittrup, Audrey R., Saida B. Hussain, Jamie N. Albright, Noelle M. Hurd, Fatima A. Varner, and Jacqueline S. Mattis. 2019. Natural Mentors, Racial Pride, and Academic Engagement Among Black Adolescents: Resilience in the Context of Perceived Discrimination. Youth & Society 51: 463–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | Black is an inclusive term that refers to individuals that self-identify as Black, in addition to individuals from the Caribbean and African diaspora and their descendants who have immigrated to the United States (Agyemang 2005). |

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Racial Discrimination Stress | - | |||||

| 2. School Belonging | 0.04 | - | ||||

| 3. Majority White School | 0.01 | −0.09 | - | |||

| 4. Academic Competence | −0.15 * | 0.23 ** | −0.05 | - | ||

| 5. Academic Efficacy | 0.07 | 0.26 ** | −0.04 | 0.57 ** | - | |

| 6. Academic Skepticism | 0.11 | −0.23 ** | −0.04 | −0.34 ** | −0.33 ** | - |

| M | 1.20 | 3.55 | 0.21 | 3.27 | 4.27 | 1.78 |

| SD | 0.74 | 1.10 | 0.41 | 0.57 | 0.82 | 0.94 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | B | SE | β | p | FDR | B | SE | β | p | FDR | B | SE | β | p | FDR |

| Age | −0.00 | 0.03 | −0.01 | 0.89 | 0.89 | −0.00 | 0.02 | −0.00 | 0.96 | 0.96 | −0.00 | 0.03 | −0.01 | 0.92 | 0.92 |

| Gender | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.12 | 0.33 | 0.49 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.43 | 0.64 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.39 | 0.64 |

| Parent Education | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.09 | 0.02 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.09 | 0.02 | 0.10 |

| RDS | −0.07 | 0.05 | −0.09 | 0.12 | 0.24 | −0.10 | 0.05 | −0.13 | 0.05 | 0.15 | −0.10 | 0.05 | −0.12 | 0.06 | 0.20 |

| SB | 0.14 | 0.03 | 0.26 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.12 | 0.03 | 0.23 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.12 | 0.03 | 0.23 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| MWS | −0.03 | 0.08 | −0.06 | 0.70 | 0.84 | −0.02 | 0.09 | −0.03 | 0.82 | 0.92 | −0.03 | 0.09 | −0.05 | 0.76 | 0.84 |

| RDS × SB | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.27 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.26 | 0.52 | |||||

| RDS × MWS | 0.07 | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.55 | 0.70 | 0.07 | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.58 | 0.72 | |||||

| SB × MWS | 0.10 | 0.09 | −0.46 | 0.22 | 0.39 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.19 | 0.21 | 0.52 | |||||

| RDS × SB × MWS | 0.10 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.45 | 0.64 | ||||||||||

| R2 | 0.10 ** | 0.11 | 0.12 | ||||||||||||

| F for change in R2 | 4.51 ** | 3.51 ** | 3.21 ** | ||||||||||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | B | SE | β | p | FDR | B | SE | β | p | FDR | B | SE | β | p | FDR |

| Age | −0.04 | 0.034 | −0.04 | 0.35 | 0.50 | −0.04 | 0.04 | −0.04 | 0.34 | 0.64 | −0.04 | 0.04 | −0.05 | 0.26 | 0.48 |

| Gender | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.42 | 0.50 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.49 | 0.65 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.35 | 0.50 |

| Parent Education | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.20 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.45 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.23 |

| RDS | −0.10 | 0.06 | −0.09 | 0.10 | 0.20 | −0.08 | 0.07 | −0.08 | 0.22 | 0.64 | −0.07 | 0.07 | −0.07 | 0.29 | 0.48 |

| SB | 0.21 | 0.04 | 0.28 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.21 | 0.05 | 0.29 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.21 | 0.05 | 0.28 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| MWS | −0.02 | 0.12 | −0.02 | 0.87 | 0.87 | −0.01 | 0.12 | −0.02 | 0.90 | 0.90 | −0.04 | 0.12 | −0.05 | 0.72 | 0.81 |

| RDS × SB | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.51 | 0.65 | −0.02 | 0.07 | −0.03 | 0.73 | 0.81 | |||||

| RDS × MWS | −0.15 | 0.17 | −0.14 | 0.36 | 0.64 | −0.18 | 0.17 | −0.16 | 0.28 | 0.48 | |||||

| SB × MWS | −0.02 | 0.12 | −0.03 | 0.86 | 0.90 | −0.01 | 0.12 | −0.01 | 0.96 | 0.96 | |||||

| RDS × SB × MWS | 0.46 | 0.19 | 0.46 | 0.01 | 0.05 | ||||||||||

| R2 | 0.11 ** | 0.11 | 0.13 * | ||||||||||||

| F for change in R2 | 5.03 ** | 3.49 ** | 3.81 ** | ||||||||||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | B | SE | β | p | FDR | B | SE | β | p | FDR | B | SE | β | p | FDR |

| Age | −0.06 | 0.05 | −0.06 | 0.21 | 0.42 | −0.06 | 0.05 | −0.06 | 0.21 | 0.63 | −0.06 | 0.05 | −0.06 | 0.24 | 0.71 |

| Gender | −0.11 | 0.12 | −0.12 | 0.36 | 0.44 | −0.13 | 0.13 | −0.13 | 0.32 | 0.69 | −0.13 | 0.13 | −0.14 | 0.29 | 0.71 |

| Parent Education | −0.06 | 0.04 | −0.07 | 0.11 | 0.33 | −0.06 | 0.04 | −0.07 | 0.11 | 0.49 | −0.06 | 0.04 | −0.07 | 0.11 | 0.55 |

| RDS | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.43 | 0.44 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.54 | 0.69 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.57 | 0.71 |

| SB | −0.21 | 0.05 | −0.25 | <0.01 | <0.01 | −0.21 | 0.06 | −0.24 | <0.01 | <0.01 | −0.21 | 0.06 | −0.24 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| MWS | −0.11 | 0.14 | −0.12 | 0.44 | 0.44 | −0.11 | 0.145 | −0.12 | 0.45 | 0.69 | −0.10 | 0.15 | −0.11 | 0.49 | 0.71 |

| RDS × SB | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.54 | 0.69 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.41 | 0.71 | |||||

| RDS × MWS | −0.01 | 0.21 | −0.01 | 0.97 | 0.99 | 0.00 | 0.21 | 0.00 | 0.99 | 0.99 | |||||

| SB × MWS | 0.00 | 0.15 | −0.00 | 0.99 | 0.99 | −0.01 | 0.15 | −0.01 | 0.97 | 0.99 | |||||

| RDS × SB × MWS | −0.16 | 0.24 | −0.14 | 0.57 | 0.71 | ||||||||||

| R2 | 0.08 ** | 0.08 | 0.08 | ||||||||||||

| F for change in R2 | 3.42 ** | 2.30 * | 2.11 | ||||||||||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Morris, K.S.; Seaton, E.K.; Iida, M.; Lindstrom Johnson, S. Racial Discrimination Stress, School Belonging, and School Racial Composition on Academic Attitudes and Beliefs among Black Youth. Soc. Sci. 2020, 9, 191. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9110191

Morris KS, Seaton EK, Iida M, Lindstrom Johnson S. Racial Discrimination Stress, School Belonging, and School Racial Composition on Academic Attitudes and Beliefs among Black Youth. Social Sciences. 2020; 9(11):191. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9110191

Chicago/Turabian StyleMorris, Kamryn S., Eleanor K. Seaton, Masumi Iida, and Sarah Lindstrom Johnson. 2020. "Racial Discrimination Stress, School Belonging, and School Racial Composition on Academic Attitudes and Beliefs among Black Youth" Social Sciences 9, no. 11: 191. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9110191

APA StyleMorris, K. S., Seaton, E. K., Iida, M., & Lindstrom Johnson, S. (2020). Racial Discrimination Stress, School Belonging, and School Racial Composition on Academic Attitudes and Beliefs among Black Youth. Social Sciences, 9(11), 191. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9110191