How Do People Become Foster Carers in Portugal? The Process of Building the Motivation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Models of Social Welfare, Family Policy and Child Protection Systems

1.2. Portugal: The Foster Care Reality in a Comparative Perspective

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample

2.2. Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

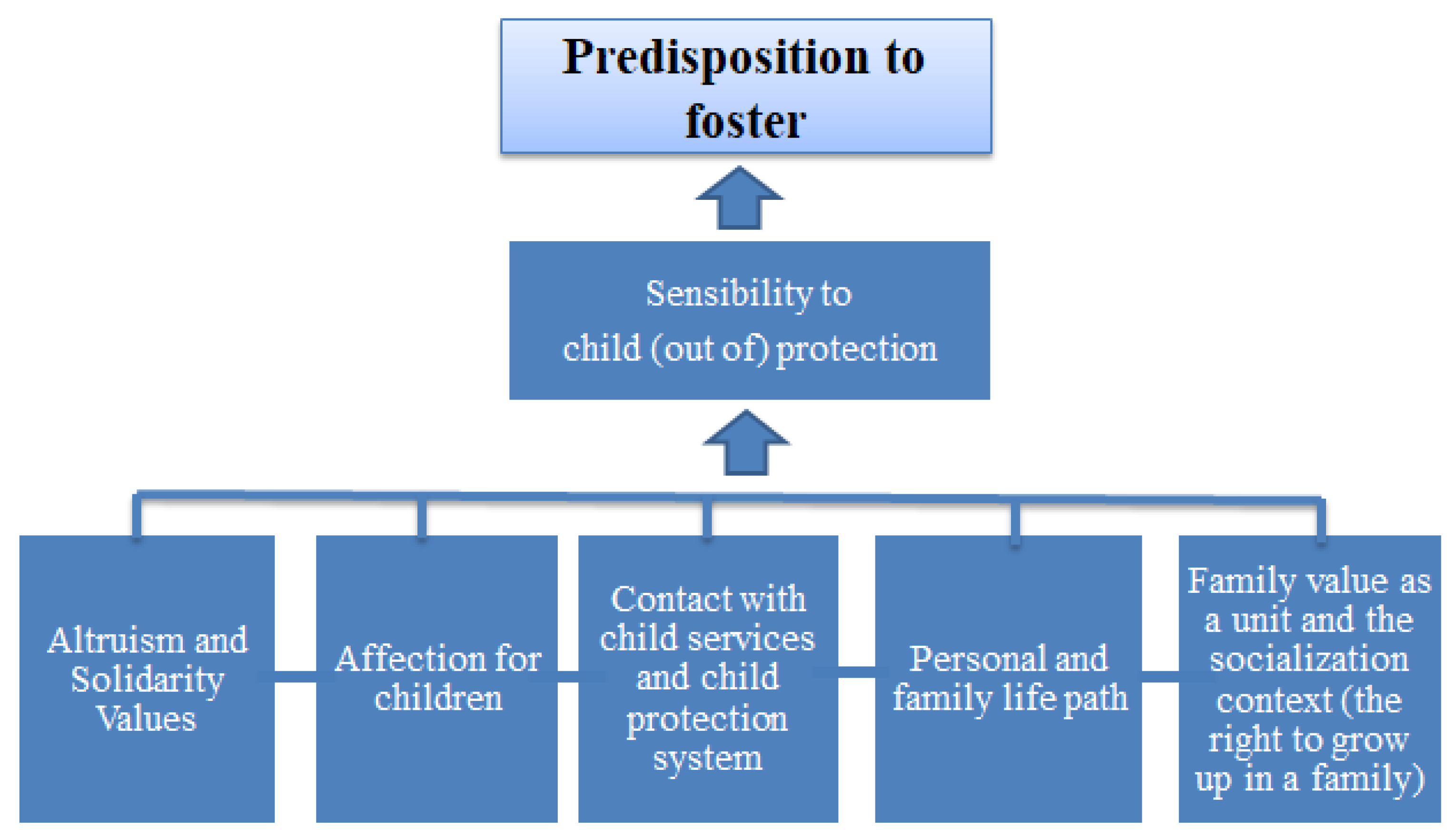

The Process of Motivation for Being a Foster Family

“He [a boy] was beaten by his mother’s mate. At the time the services said—He stays there tonight [at a neighbor’s home], do you mind? And then they became a foster family ... ”(Team A).

“They started to have foster kids coming from [municipality] Viana, hearing impairment, and they are located near that [specialized] school, they [foster kids] were there, but they were going home at the weekend, the parents were not bad parents!”(Team A).

“I think families have a rather romanticized and poetic view (...) they are not aware that this has many implications in fact: I have to go to court, receive in my house the father who beat John [fictitious name], and be able to tell John that your dad is getting better, he likes you, we’ll work with him, he’ll even have lunch with us, there are things that have already changed. This is demanding. [...] This is of a level of exigency and complexity that some families are not aware of.”(Team A).

“Even with a lot of training and information that the team may give to the candidates, the reality is that the families are not always available or are not always aware of the impact that foster care will create in their families, in their family dynamics, and in their children.”(Team B).

“Essentially because I really like children and I was used to having children at home.”(FCMV3—Foster Carer supported by Mundos de Vida team, caregiver, unemployed, 48 years old).

“I like children very much, I like to give affection, I like to help”.(FCMV5 caregiver, family helper, 42 years old).

“I think a child in a foster family is much better than in an institution, has more affection, more everything than in an institution. In an institution, there are many children and you cannot give the necessary attention to each one.”(FCMV2 caregiver, operational assistant in schools, 41 years old).

“We were told there was a great connection to each other [between the adopted child and her sister]. (...) -And now?! We were going to separate two sisters?”(Caregivers of FCMV3, unemployed, 41 years old and optometrist, 39 years old).

“We got on well with the social worker, so that A [foster child] did not move away from her brothers, it was a family ... We wanted A [foster child] to not disconnect from the [biological] family.”(ExFCCPCJ—Foster Carers supported by Child Protection Commission, who do not foster anymore, caregivers, teachers of cooking, 38 and 39 years old).

“My vocation [to be a foster family] comes from the fact that I have never had a mother. Never felt what mother’s love was.”(Caregiver of FCSS2, 62 years old, domestic worker).

“My son, who is eleven years old and in the fourth class, came home with a pamphlet “Need Hugs”, and told me: -The teacher said that all parents should consider fostering because the children need a family and to be happy. -Well, they do Y [her son], and your mother knows that, because your mother works with children and sees it in her daily life, unfortunately. That got me into the idea, so I called the Mundos de Vida”(FCMV2 caregiver, operational assistant in schools, 41 years old).

“I think in the institutions where they end up ... I’m sceptical, my father worked for a long time in an institution and told about situations that I recorded. Heavy situations and it was an institution of nuns. Things that no one would like. Those kids were going to get lost. A [foster child] could never grow up in an institution”(FCMV5 caregivers, family supporter, 42 years old and electrician, 45 years old).

“They [students] see me as a person who is there to help them. I have kids coming to me. I stopped training them, but they are my friends, I commit myself. The experience [foster] was good in that aspect, openness to the young people who need our support, I am not there to criticize them”(exFCCPCJ caregivers, cook teachers, 38 and 39 years old).

“The girl ... the girl I never had; I do not know if you understand me ... I have a boy, I never wanted to have more”(FAMV4 caregiver, domestic worker, 44 years old).

“It was through the poster with a girl. We have two boys, and that’s where the joke started -So having a girl would be funny!”(FAMV5 caregiver, family supporter, 42 years old).

“I have only one daughter, but the house at the weekend and on vacation was always full ... My husband loves children and my daughter too. (...) She wants to buy presents for them (foster children) with her allowance, but I do not allow it.”(FAMV3 caregiver, unemployed, 48 years old).

“They have essentially a solidary motivation, the feeling of helping and helping to a child (…) and also a temporary help (...) And also the pedagogical reason, they want to teach their biological children the values.”(Team B)

“My mother is eighty-two, and she loves the little one [foster baby]. My father, unfortunately, cannot see, but he likes to grab him on his lap, and then he starts to do things to him and he laughs. It makes my father happy, it was a self-esteem for my father, because he was going into depression for losing his view. The boy came to bring him joy despite not seeing him”(caregiver of FAMV1, hairdresser, 51 years old).

“When this economic crisis broke out a couple years ago, it was frequent at Social Security, it was common to see people signing up as a foster family or a nanny. The motivation was economic, they were in a situation of unemployment and this could be a [way of] life (...). Nannies who are going to be unemployed, asked. I suggested to talk to Mundos de Vida, but the motivation was economic.”(Team A)

“He [husband] said -Since you’re alone [husband working out of the country] at home, besides having a companion, having a job... it means working hard, we can see it by ours [biological children], I have a twenty-year-old son”(FAMV4 caregiver, domestic worker, 44 years old).

“I was such in a [bad] moment that I told my mother -I have to look for a part-time [job]. Because since my [child] left [died]... When my daughter was here [alive], I had a lot of work, a child with cerebral paralysis bedridden gives a lot of work. I was feeling very isolated, with nothing to do. When D [foster child] came to me it was like air, fresh air. I was saying—I have to leave home, because I am damaging my [children]. My children came home: -Mother, are you sick today?” You don’t look okay... ”(FAMV1 caregiver, hairdresser, 51 years old).

“[there is a need] to greatly improve the support system to the foster families, from the remuneration system, therefore the value that is paid, the tax system ...”(Team B).

“One of the important issues that will weigh, is the economic component, very little is paid, [...] we know that a child costs money.”(Team A).

4. Conclusions and Implications for Practice

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Amorós, Palacios, and Jesus Palacios. 2004. Acogimiento Familiar. Madrid: Alianza Editorial. [Google Scholar]

- Assembleia da República. 2005. Constitution of the Portuguese Republic VII Constituional Review. Available online: https://www.parlamento.pt/Legislacao/Documents/constpt2005.pdf (accessed on 3 July 2015).

- Branco, Francisco. 2009. The Sun and the Clouds: Meaning, Potential and Limits of the Primary Solidarity in Portugal in the context of Southern European welfare systems. Paper presented at 7th ESPAnet Conference 2009, Urbino, Italy, September 17–19. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, Katy. 2006. Constructing Grounded Theory—A Practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis. London: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Colton, Matthew, Susan Roberts, and Margaret Williams. 2008. The Recruitment and Retention of Family Foster-Carers: An International and Cross-Cultural Analysis. British Journal of Social Work 38: 865–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Valle, Jorge. 2008. El Acohimiento Familiar en España. Una evaluación de resultados. Madrid: Ministerio de Trabalho y Assuntos Sociales. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado, Paulo. 2007. Foster Care—Concepts, Practices and (Un)definitions (Acolhimento Familiar—Conceitos, práticas e (in)definições). Porto: Profedições, Lda. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado, Paulo. 2008. Children and Caregivers—Life Stories and Families (Crianças e Acolhedores—Histórias de Vida e Famílias). Porto: Profedições, Lda. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado, Paulo. 2011. Foster Care, An Ecological Perspective (O Acolhimento Familiar de Crianças, Uma perspetiva ecológica). Porto: Profedições, Lda. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado, Paulo, ed. 2013. Children’s Foster Care, Evidences of the Present, Challenges for the Future (Acolhimento Familiar de Crianças, Evidências do presente, desafios para o futuro). Porto: Mais Leituras Editora. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado, Paulo, ed. 2016. O Contacto no Acolhimento Familiar—O que pensam as crianças, as famílias e os profissionais. Porto: Mais Leitura. [Google Scholar]

- Department for Education. 2018. Children Looked after in England (Including Adoption), Year Ending 31 March 2018. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/757922/Children_looked_after_in_England_2018_Text_revised.pdf (accessed on 25 July 2019).

- Department of Health. 2018. Children’s Social Care Statistics for Northern Ireland 2017/18. Available online: https://www.health-ni.gov.uk/sites/default/files/publications/health/child-social-care-17-18.pdf (accessed on 25 July 2019).

- Doucet, Mélanie, Élodie Marion, and Nico Trocmé. 2018. Group Home and Residential Treatment Placements in Child Welfare: Analyzing the 2008 Canadian Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect. Canadian Child Welfare Research Portal. Available online: ccwrp.ca (accessed on 31 March 2018).

- Doyle, Jennifer, and Rose Melville. 2013. Good Caring and Vocabularies of Motive among Foster Carers. Journal of Comparative Research in Anthropology and Sociology 4: 71–90. [Google Scholar]

- Flick, Uwe. 2005. Qualitative Methods in Scientific Research (Métodos Qualitativos na Investigação Científica). Lisboa: Monitor—Projetos e Edições, Lda. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, Marisol, and Yuri Kazepov. 2002. Why some people are more likely to be on social assistance than others. In Social Assistance Dynamics in Europe. Edited by Chiara Saraceno. Bristol: The Policy Press, pp. 127–72. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, Neil, Nigel Parton, and Marit Skivenes. 2011. Child Protection Systems: International Trends and Orientations. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Guerreiro, Maria das Dores. 2011. Family Structures and Social Contexts (Estruturas Familiares e Contextos Sociais). In The Family in General and Family Medicine (A Família em Medicina Geral e Familiar). Edited by Luís Rebelo. Lisbon: Verlag Dashofer. [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero, Teresa, and Manuela Naldini. 1996. Is the South so Different? Italian and Spanish Families in Comparative Perspective. Mannheim: Mannheim Center of European Social Research. [Google Scholar]

- Howell-Moroney, Michel. 2014. The Empirical Ties between Religious Motivation and Altruism in Foster Parents: Implications for Faith-Based Initiatives. Religions 5: 720–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto de Segurança Social, I. P. 2018. Caracterização Anual das Situações de Acolhimento de Crianças 2017. Available online: http://www.seg-social.pt/documents/10152/16000247/Relatorio_CASA_2017/537a3a78-6992-4f9d-b7a7-5b71eb6c41d9 (accessed on 1 December 2018).

- Kalil, Ariel. 2003. Family Resilience and Good Child Outcomes—A Review of the Literature. Wellington: Centre for Social Research and Evaluation, New Zealand Ministry of Social Development. [Google Scholar]

- Lamont, Alister, Rhys Price-Robertson, and Leah Bromfield. 2010. Intake, investigation and assessment—Background Paper. Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Leber, Cristina, and Craig LeCroy. 2012. Public Perception of the Foster Care System: A National Study. Children and Youth Services Review 34: 1633–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacGregor, Tracey, Susan Rodger, Anne Cummings, and Alan Leschied. 2014. Rescuing a Critical Resource: A Review of the Foster Care Retention and Recruitment Literature and its Relevance in the Canadian Child Welfare Context. Ottawa: Canadian Foster Family Association, University of Western + University of Ottawa. [Google Scholar]

- Maeyer, Skrallan, Johan Vanderfaeillie, Femke Vanschoonlandt, Marijke Robberechts, and Frank Van Holen. 2014. Motivation for Foster Care. Children and Youth Services Review 36: 143–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad. 2017. Boletín de datos estadísticos de medidas de protección a la infância. Boletín número 18. Available online: http://www.observatoriodelainfancia.mscbs.gob.es/productos/pdf/Boletinproteccionalainfancia18accesible.pdf (accessed on 25 July 2019).

- Nutt, Linda. 2006. The Lives of Foster Carers, Private Sacrifices, Public Restrictions. London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- Octoman, Olivia, and Sara McLean. 2014. Challenging Behaviour in Foster Care: What Supports do Foster Carers Want? Adoption & Fostering 38: 149–58. [Google Scholar]

- Pais, Machado, ed. 1999. Traits and Risks of Life, A Qualitative Approach to Young People Lifestyles (Traços e Riscos de Vida, Uma abordagem qualitativa a modos de vida juvenis). Ambar: Coleção Trajetórias. [Google Scholar]

- Portugal, Sílvia. 2000. Rhetoric and Governance in the Policy Area of the Family since 1974 (“Retórica e Ação Governativa na Área das Políticas da Família desde 1974”). Revista Crítica de Ciências Sociais 56: 81–98. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes, Katrin, Marie Ellen Cox, John Orme, and Tanya Coakley. 2006. Foster Parents’ Reasons for Fostering and Foster Family Utilization. Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare 33: 105–25. [Google Scholar]

- Schofield, Gillina, Marie Beek, Kay Sargent, and June Thoburn. 2000. Growing Up in Foster Care. London: British Agencies for Adoption and Fostering. [Google Scholar]

- Sherbanov, Veliko. 2012. Evaluation of the Project Expansion of Foster Care Model in Bulgária—Evaluation Report. Sofia: Open Society Publishing House, Bulgária. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, Pedro. 2002. The Welfare Model of Southern Europe, Reflections on the Usefulness of the Concept (“O Modelo de Welfare da Europa do Sul, Reflexões sobre a utilidade do conceito”). Sociologia, Problemas e Práticas 38: 25–59. [Google Scholar]

- Unicef. n.d. Convention on the Rights of the Child. Available online: https://www.unicef.pt/media/1206/0-convencao_direitos_crianca2004.pdf (accessed on 25 July 2019).

- Wall, Karin, Sofia Aboim, Vanessa Cunha, and Pedro Vasconcelos. 2001. Families and Informal Support Networks in Portugal: The Reproduction of Inequality. Journal of European Social Policy 11: 213–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Diogo, E.; Branco, F. How Do People Become Foster Carers in Portugal? The Process of Building the Motivation. Soc. Sci. 2019, 8, 230. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8080230

Diogo E, Branco F. How Do People Become Foster Carers in Portugal? The Process of Building the Motivation. Social Sciences. 2019; 8(8):230. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8080230

Chicago/Turabian StyleDiogo, Elisete, and Francisco Branco. 2019. "How Do People Become Foster Carers in Portugal? The Process of Building the Motivation" Social Sciences 8, no. 8: 230. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8080230

APA StyleDiogo, E., & Branco, F. (2019). How Do People Become Foster Carers in Portugal? The Process of Building the Motivation. Social Sciences, 8(8), 230. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8080230