Abstract

Gated communities, one of those originally Western developments, have suddenly been found in cities in the Global South. “Gated communities”, often defined on the basis of their physical form, have been criticized for disconnecting residents from their neighbors outside the gates and reducing social encounters between them. Focusing on cities in the Global South, a large body of research on social encounters between the residents of gated communities and others outside has used case studies of the middle class living in gated communities versus the poor living outside in slums, squats, or public housing. The assumption that gated communities are regarded as enclosed residential spaces exclusively for the middle class, while the poor are found solely in “informal” settlements, may have an effect of stigmatizing the poor and deepening class divisions. It is rare to find studies that take into account the possibility that there also exist gated communities in which the poor are residents. This article examines who the residents of gated communities are, and at the same time analyzes the extent to which people living in gated communities socialize with others living outside. Based on the results of qualitative research in Bangkok, Thailand, in particular, the article critically studies enclosed high-rise housing estates and shows the following: Walls and security measures have become standard features in new residential developments; not only the upper classes, but also the poor live in gated communities; the amenities which gated communities provide are available to outsiders as well; and residents living in gated communities do not isolate themselves inside the walls but seek contact and socialize with outsiders. This article argues that the Western concept of “gated communities” needs to be tested and contextualized in the study of cities in the Global South.

1. Introduction

Gated communities as enclaves of residential space have been in the spotlight of urban studies and housing and neighborhood studies since the 1970s. Gated communities in U.S. cities became a popular object of study in the 1980s–1990s (Blakely and Snyder 1997; Davis 1990; Low 1997). Later, studies were expanded to other cities in the Global North (Atkinson and Flint 2004; Grant 2005), as well as to cities in the Global South (Coy and Pöhler 2002; Falzon 2004; Hook and Vrdoljak 2002; Leisch 2002; Wissink and Hazelzet 2016). A large body of literature portrays gated communities as “affluent” residential enclaves, a type of residential area equipped with walls, gates, and security guards to restrict public access; a variety of services and amenities exclusively offered to residents, called “club services”; and legal frameworks serving as a private, micro-constitutional and self-organized body to control residents and govern the space (Atkinson and Blandy 2005; Blakely and Snyder 1997; Low 2001; Morange et al. 2012; Wissink et al. 2012).

Following Blakely and Snyder (1997), several studies have analyzed the social effects of gated communities and regard them as an answer to the demands for safety and security, lifestyle, or prestige living. Gated communities are criticized for disconnecting residents from neighbors outside the gates and reducing social encounters between them (Wissink and Hazelzet 2016). Resting on the notion that gated communities are developed for the rich, literature on gated communities, particularly those in cities in the Global South, often focuses on gated communities in which the upper and middle classes live. Aside from focusing on safety and security, lifestyle, or prestige living (Blakely and Snyder 1997), a small number of urban scholars have attempted to analyze other functions of gated communities. For example, Grant and Mittelsteadt (2004, p. 927) offer an in-depth analysis of gated communities by looking at the varying degrees of enclosure and club services provided in gated residences, resident types, and policy issues, and they point out that gated communities “respond to divergent local circumstances”. Nevertheless, it is rare to find studies demonstrating that people with varying incomes live in gated communities. A small number of studies analyze other types of gated communities, especially those found in cities in the Global South, based not on income but on race, ethnicity, or religion (see Durington 2006; Sanchez et al. 2005). Despite attempts to read gated communities beyond their physical form as “affluent” residential projects, studies on social encounters between the residents of gated communities and others outside of the gates in their research design often selected case studies with the middle class living in gated communities versus the poor living outside in “informal” settlements1, such as slums, squats, and self-built housing, or public housing.

The way in which several studies portray gated communities as privatized, privileged, and enclosed spaces of the middle class, while the poor only live in “informal” settlements or public housing, shows two implicit assumptions. The first assumption is that gated communities, as a middle-class residential space, promise a particular way of luxurious living to gain distance from—and security against—the poor. Seeing gated communities as fulfilling the housing preferences of privileged groups is perhaps misleading. Being influenced by a subconscious fear that “where you live affects your life chances” (see Gans 1968) can lead one to regard as natural that the middle class should want to take distance from “neighborhood effects” or “concentrated poverty”, and from public housing, which is believed to be a place of violence, poverty, and drugs (see Slater 2013, p. 386; van Ham et al. 2012). Based on the discourse of “informal” settlements as the spatial “concentration of poverty”, city authorities often tried to de-concentrate poverty by using an urban revitalization program (or a slum clearance program particularly in developing cities) or a mixed-income neighborhood policy which lead to displacement of the urban poor and reinforcing social polarization (Darcy and Gwyther 2012; Lees 2008). Thus, this stereotype-guiding research of the wealthy being inside and the poor outside could have an effect of stigmatizing the latter and deepening class divisions. Second, by conveniently placing the poor in “informal” settlements in their research design, scholars tend to ignore the agency of the poor and the complexities of housing projects which have been modified in response to local contexts.

In Bangkok, the city landscape is dominated by skyscrapers, “informal” settlements, and gated communities (Sintusingha 2011). The Bangkok city government promotes slum upgrading programs, while it seems to allow private developers unrestricted development. In their study of Bangkok’s gated communities, Wissink and Hazelzet (2016) claim that in Bangkok there is no residential segregation based on race, ethnicity, or religion (such as one finds in colonial cities); nonetheless, the city experiences segregation between the rich and the poor. Considering this Bangkok context, the focus on gated communities in this article is mainly based on income class.

Given segregation in the Thai context by income but not by race, ethnicity, or religion, as well as the history of the elite living inside the walls and the rest of the population in village communities, the arrival of Western enclosed housing that assumed to lock in the wealthy and exclude the poor raises the question of how this new and foreign type of housing is adapted to the local conditions. To answer this question, by using Bangkok as a case study, this article investigates why gated communities were built in the city; who lives in these gated communities; what the club services provided by the gated communities are and who has access to them; and whether, and the extent to which, people living in gated communities socialize with others living outside.

This article is aimed at offering an in-depth analysis of actual gated communities where people with varying incomes are the residents, specifically focusing on Bangkok, an understudied city in the Global South. It is expected that this study will contribute to the ongoing discussions in urban studies on gated communities and residential segregation in cities in the Global South.

This qualitative study uses multiple research methods, consisting of semi-structured interviews with representatives from property development firms and residents of gated communities; observations and field notes from staying in five high-rise, gated housing estates in the Bangkok Metropolitan Area (four to seven weeks at each studied gated residence); and a review of documentation.

2. Gated Communities as a Unitary Phenomenon?

The city is where strangers meet, as Louis Wirth (1938) observed. For Chicago urbanists Simmel and Baudelaire, as highlighted by Sennett (1990, p. 126), “the culture of the city was a matter of experiencing differences—differences of class, age, race, and taste outside the familiar territory of oneself, in a street”. Gated communities have become a concern among urban scholars because this type of urban development separates people into their own enclaves. Gated communities are viewed as “the revolt of the elites” (Lasch 1995, p. 25), “the retreat of the upper and middle classes” (Mycoo 2006, p. 131), “new forms of exclusion and residential segregation, exacerbating social cleavages that already exist” (Low 2001, p. 45), and jeopardizing freedom in the city (Davis 1990). Gated communities are seen “as a segregating tool as they contribute to a divide socially and spatially between the ‘have lots’ and the ‘have nots’” (Atkinson 2008, p. 7), separating social classes and thus undermining social integration and arousing a fear of experiencing otherness (Atkinson and Blandy 2005, p. 178; Hook and Vrdoljak 2002; Low 2001). A consequence of this type of “defended architecture” is “the disappearance of inter-class social encounter”, because the inside of gated communities is perceived as “where comfort and security reign”, whereas the outside is understood to be a “chaotic and insecure” space (Salcedo and Torres 2004, p. 28; see also Caldeira 2000). It is likely that those living outside are perceived to be “outsiders or marginal, and unworthy of being included” (Low 2003, p. 65). On the other hand, people who live outside may see gated communities as a “hostile, fortified environment” (Roberts 2007, p. 185). When the affluent opt out of civic responsibilities and isolate themselves inside their residential enclaves, the ability of the city to provide public services is endangered (Lemanski and Oldfield 2009; McKenzie 2005). Consequently, gated communities are not just a matter of individual choice; they affect others and the whole city.

The abundance of studies on gated communities around the world gives an impression that this housing trend is inevitable and universal. Research on the issue began in the United States and then spread to other cities in the Global North, as well as the Global South. A simple definition of gated communities is that they are “residential areas with restricted access in which normally public spaces are [now] privatized” (Blakely and Snyder 1997, p. 2). Later, Atkinson and Blandy (2005, p. 178) defined a gated community as “a walled or fenced housing development to which public access is restricted, characterized by legal agreements which tie the residents to a common code of conduct and (usually) collective responsibility for management”. Other scholars (for example, Dupont 2016) also include shared amenities or club services as another vital, key component of a gated community. Scholars tend to adopt this interpretation in their research based on the physical form of gated communities. Hence, many research studies have adopted Western assumptions and approaches concerning gated communities as simply a type of enclosed prestige housing without examining how this urban phenomenon has been locally adopted or “reworked” (Pow 2009, p. 7) in different settings, or how it has served specific demands of local people. The reason could be that ideas which have been extensively used in urban studies originated in the Global North. Other ideas from the Global South, on the other hand, are unworthy of attention; they “are ignored in these hegemonic accounts” (Mabin 2014, p. 23). Robinson and Roy (2016, p. 181) point to the need to “rethink the Euro-American legacy of urban studies” and think deliberately “the relational multiplicities, diverse histories and dynamic connectivities of global urbanisms”, particularly in studying urban transformations in cities of the South.

Gated communities in the Global South are not necessarily the same phenomenon as in the West, nor do they necessarily follow the Western model, as they may have been developed in response to conditions different from those in the West. Grant and Mittelsteadt (2004, p. 927) claim that “gating is not a unitary phenomenon”. Caldeira (2000) argues that the enclosed condominiums in São Paulo are typically apartment buildings. Although they serve the purpose of security, they are more urban than suburban, unlike gated communities in the United States. In a case study of Cape Town, Lemanski and Oldfield (2009, p. 638; see also Ballard 2004) point out that gating is “a form of semigration”, meaning that the residents of gated communities “separate themselves from its increasing ‘African-ness’ and instead create islands of modern Western culture … in the midst of an African nation, albeit within walls and gates … as in situ emigration to the dreamed-of ‘foreign paradise’”. Building gated communities in Lemanski and Oldfield (2009)’s essay means establishing a new type of community with shared cultural interests of the residents. This type of housing, thus, serves more than just the purposes of security and prestige lifestyle. In Israel, Rosen and Razin (2008) argue that when compared with those in other cities in the developing countries, Israel neighborhoods are considered to be relatively safe. Gated communities in many areas appear to be a “softer” version, particularly of the small housing projects; they “are less strictly guarded and enclosed” (Rosen and Razin 2008, pp. 2908–9). In the case of Indonesia, Leisch (2002) found out that the Chinese, a middle-class ethnic minority residing in gated communities. Living in gated communities in Indonesia, as argued by Leisch (2002), is a way to continue living in ethnically segregated residential neighborhoods, fenced into walled quarters, as imposed by Dutch colonialists. However, why this new form of housing meets the needs of a Chinese minority today is complex. It is based on not only a continuation of the former way of life, but also a mixture of lifestyle, prestige, and safety needs. In addition, Douglass and his colleagues (2012) found an affluent gated community in Guangzhou, China, which allows students from outside to attend its international school. This Chinese case study shows an unusual practice of “de-gating”, allowing outsiders to access the housing estate and use its facility. These cases demonstrate that some gated communities in the Global South cannot be understood simply by the overemphasis of unitary physical form of gates, walls, fences, and security guards, and club services, nor can they be fully explained by their functions of safety, lifestyle, or prestige living. Gated communities in cities the Global South have been “reworked” or “reshaped” in a variety of ways, responding to local contexts, or they have served specific demands of the locals based on historical, traditional, socio-spatial conditions, and the way of life. This is also true in the case of Bangkok, which this article shall discuss further.

Instead of focusing on the physical form and seeing gated communities as a unitary occurrence found in all parts of the world, Brunn and Frantz (2006, p. 3) point out that there is a need to contextualize and examine gated communities by identifying the following: The origins, functions, and morphology of gated communities; urban planning and the role of local government; the legal or regulatory framework; and who the residents of the gated communities are.

Drawing on Brunn and Frantz’s (2006, p. 3) aforementioned framework for analyzing gated communities, the following four sections center on an analysis of gated communities in Thailand, particularly in the city of Bangkok. In the first section, the discussion begins by examining the concept of “ban” or village community, the history of urban planning and Bangkok’s morphology, and relevant Thai legislation associated with enclosed housing construction. It then presents the functions and types of gated communities addressed in the previous literature. The second section discusses methodology and methods. The third section employs the qualitative data that the author collected in Bangkok while staying in five high-rise, gated housing estates, as well as interviews with residents and developers to investigate the average unit prices and their location; the club services and amenities provided; the reasons why developers chose to build gated housing projects; who lives in this type of private housing; and the social interactions between the residents and those living outside the gates. The last section offers conclusions.

3. The Emergence of Gated Communities in Thailand

Historically, while the king and royal family of Thailand resided in enclosed palaces surrounded by residences of noblemen in a walled city, ordinary people lived in “ban” or village communities on the banks of rivers and canals (Askew 2002). The Thai word “ban” (literally translated as “home”) possesses various meanings. It can refer to a place of residence, a cluster of houses or a village, or a settlement or populated place where people live (Tambiah 1970). Being a significant concept in Thai agrarian society, anthropologists (Potter 1976; Tambiah 1970) have considered “ban” to be a fundamental social structure, or “village community”. Being self-sufficient (Nartsupha [1984] 1999), villagers grew rice and crops, or they produced small commodities, living on land which was given by their ancestors to the community and “individuals did not occupy land directly but through their membership in the village which in reality controlled the land in that area” (Nartsupha [1984] 1999, pp. 26–27). With strong bonds existing among the villagers, there was no class differentiation. “Control of land was mediated by membership of the community … Members shared mutual sympathy and cooperation which gave them security and contentment” (Nartsupha [1984] 1999, pp. 73–74).

Thailand had never been politically colonized by the European colonial powers, and thus it escaped segregating town plans (unlike other Southeast Asian countries). However, the country itself did adopt a European version of the modern city (Sintusingha and Mirgholami 2013). In the 1850s, free-trade agreements with the European colonial powers, in particular the 1855 Bowring Treaty with Britain, turned the Thai kingdom into “a semi-colony, with its commercializing economy tied to the world trading system” (Anderson 1978, pp. 198–200). During this period, Western ideas of progress, technology, capital, and land-based culture were imported (Askew 2002; Baker and Phongpaichit 2009). Thai kings started utilizing “a western land code and claimed ownership of all ‘unoccupied’ land … and taxes were changed from head taxes to taxes based on land and usufruct rights” (Buch-Hansen 2001, pp. 17–80). The new taxing method put pressure on villagers to produce more rice and crops to sell in the market. Since technologies were not widely introduced, villagers produced rice at home and were self-subsistent (Nartsupha [1984] 1999).

The reign of King Chulalongkorn (1853–1910) witnessed the restructuring of the Bangkok urban landscape: City walls were torn down; an avenue was modelled on the Champs-Élysées in Paris and more roads and railways were built; shophouses replaced floating markets; and canals were filled for the construction of roads (Sintusingha and Mirgholami 2013). Bangkok became a land-based city. Significant reforms also included the land titling introduced in the 1890s. The monarch, the royal family, the nobility, and a group of Thai and Chinese commoners were given rights to land, either as owners or as tenants. These changes made the Bangkok urban landscape in the early twentieth century resemble that of European and colonial cities, with Western stores, hotels, an electric tram system, and a European-designed central railway station (Askew 2002). An increasing number of ordinary Thai people migrated from the hinterlands to live and work in the inner city. Filled-in canals turned into “soi” (alleys or small streets); while shophouses made of concrete lined the main roads, “soi” became settlements of wooden houses where urban dwellers lived and worked.

In 1932, following a coup led by a group of European-educated civilian and military bureaucrats, Thailand changed its regime to a constitutional monarchy. During the first civilian government, the role of the monarchy was sidelined (Baker and Phongpaichit 2009). Economic policies at the time tried to promote industrialization and the formal economy sector. However, there was no redistribution of wealth, and noblemen remained key landlords of urban real estate (Askew 2002). After World War II, Bangkok’s landscape changed from that of a European city to a U.S.-style one. U.S. foreign policy in the 1950s aimed to make Thailand a bastion of anti-communism in the region, and therefore a large amount of military subsidies and development funding was provided to the Thai government. During this period, the government followed the economic development prescriptions proposed by the World Bank, which promoted privatization and industrialization (Chaloemtiarana 2007). In 1960, the American consulting firm Litchfield, Whiting, Bowne, and Associates proposed the “Greater Bangkok Plan B.E. 2533”. This plan introduced zoning and, following the principles of modernist town planning, separated industrial, commercial, and residential land uses. However, the plan was never implemented. The City Planning division of the Bangkok government drew up its own master plan for the city in 1971; this plan was officially implemented only in 1992. Between the 1960s and 1990s, Bangkok had already become an “automobile city”, as canals were filled and major roads, highways, and mass transit infrastructure were built. The result was a metropolis created by international and economical forces; Bangkok is not a city designed for Bangkokians (Sintusingha and Mirgholami 2013). As Frey (1999, p. 2) describes, the characterization of the type of city which emerges through a style of planning that ignores collective values, “Such a city just happens”. Askew (2002) deplores how the functions of town planners “were restricted to ‘painting the colors’ … of the land uses they could not control” (Askew 2002, p. 55). By the late 2000s, similar to many capital cities in Southeast Asia, Bangkok became dominated by concrete, steel and glass high-rises, highways and elevated expressways, shopping malls, factories, and gated communities (Sintusingha 2011, pp. 142–44).

Today, there are two types of gated communities: The low-rise or “mubanchatsan” (a cluster of detached houses) and the high-rise or “aakanchut” (the so-called ‘condo’, derived from ‘condominium’, being a single high-rise residential building or cluster of them) (Moore 2015; Suwannasang 2015; Wissink and Hazelzet 2016). Both kinds of gated communities have become common forms of housing in Bangkok’s real estate market due to legislation which creates the conditions for lucrative development business.

The Land Code Act in 1954 set limitations on the amount of private landholdings. Five years later, the Proclamation of the Revolutionary Council No. 49 revoked these restrictions, allowing private developers to buy land and develop it without any hindrances. This was the beginning of speculative development in Bangkok. The early 1960s saw the development of low-rise gated communities, especially in suburban Bangkok, as an answer to the demand by the emerging middle classes for prestigious and safe housing (Askew 2002).

In 1972, the Proclamation of the Revolutionary Council No. 286 was passed in order to increase regulation of the size of development projects, the amount of allocated land plots, and the plan for shared amenities. Unintentionally, these rules benefitted big developers with robust financial capacities while driving “small developers out of business”, and they introduced the development of housing estates instead of land subdivided into low-rise housing (Bello et al. 1998, p. 107). In the 1970s, liberal bank lending increased the amount of money sunk into real estate. The Condominium Act in 1979 made possible multiple ownership of land, and it gave a condominium owner the title of the land, making high-rise residential buildings a popular type of development. Another reason for the development of high-rise condominiums was rising land prices; for developers as well as for buyers, vertical housing was understood as a solution. The Act also allowed expatriates to buy condominium units in Thailand. In addition, the Thai government permitted foreign investment in real estate (Askew 2002; Bello et al. 1998). For example, the Raimond Land Company, one of the largest Thai condominium developers, has a foreign asset management company as its largest shareholder2. Statistical data from 2015 shows that there were 1086 low-rise (Real Estate Information Center 2015) and 2427 high-rise gated housing estates (Department of Land 2015) in Bangkok that year.

Overall, Thai legislation since 1959 has created conditions for private land development to profit from the development of low-rise and high-rise gated communities in Bangkok. This explains the supply of gated communities. But what about the demand?

In Bangkok: Place, Practice and Representation (2002), Marc Askew offers detailed information about living in low-rise and high-rise gated housing estates. His study is supplemented by a recent study on gated communities by Wissink and Hazelzet (2016), which investigates social encounters between and within different income groups of residents in three types of neighborhoods: “Informal” settlements, low-rise gated communities, and high-rise gated communities. They found that the lower income group had maintained a higher degree of social contacts amongst group members, compared to the higher income group. Moreover, the poorer group seemed to know the richer well through the labor they provided in affluent neighborhoods, whereas the richer did not know the poorer and never-visited neighborhoods. The middle classes (lower, middle, and higher) lived in gated communities, while the urban poor lived in “informal” settlements. These results show that there were different degrees of social encounters between them and their neighbors outside. Household income and perceptions towards others are factors contributing to the degree of social encounters between different income groups. In its explanation of social encounters, this study apparently did not pay enough attention to the quality of infrastructure and club services provided in gated communities, nor to the social and spatial characteristics of the neighborhoods surrounding gated communities. These neighborhood characteristics and types of club services, however, matter. The next section shall present the research methodology and methods. The following section shall discuss Bangkok gated housing estates and who their residents are, and address how the location, the club services provided, and the “ban” or village community life have impacted on social encounters between the residents and others living outside.

4. Methodology and Methods

In an attempt to study gated communities beyond their physical form and security measures, this article examines who lives in gated communities and the extent to which they socialize with others living outside, what kind of club services provided and who has access to them, and the characteristics of neighborhood. Given the complexity of the issue and a necessity for the study to be conducted in the real-life settings, a qualitative research approach is used, and case studies are employed to provide insights into an under-researched area, in particular gated communities where their residents with varying levels of income live.

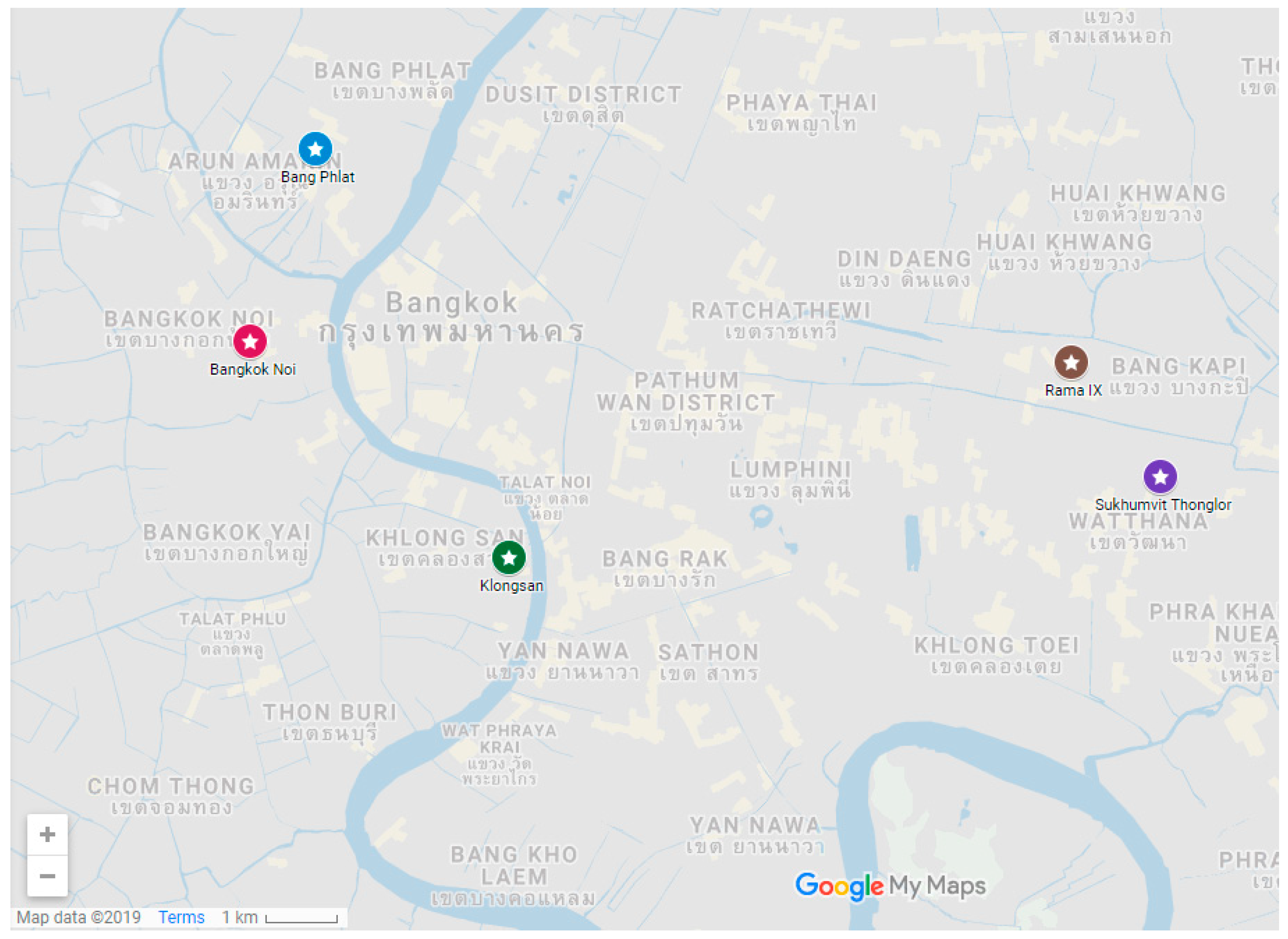

Unlike previous research on Bangkok’s gated communities which emphasizes primarily suburban enclosed housing developments, this article focuses on gated communities in the Bangkok Metropolitan Area. Since the article pays attention to the income class of residents and the neighborhood where gated communities are located, five gated housing estates in five neighborhoods—namely Sukhumvit Thonglor, Klongsan, Bang Phlat, Bangkok Noi, and Rama IX—were selected as case studies. The selection was based on difference of not only the unit prices, but also the neighborhood’s characteristics, since these may affect the social interaction between the residents of gated communities and others outside the gates.

Empirical data were collected between December 2015 and June 2019, from: Semi-structured interviews with the residents of gated housing estates and developers; field notes and observations of architecture and security measures, types of club services and amenities, and who can access to them; physical and social features of the neighborhood; and review of documentation including laws, policies, and relevant regulations.

Realizing that this type of enclosed housing is inaccessible to non-residents, while conducting this research the author stayed for four to seven weeks in each studied gated residence. Thirty-four residents were interviewed. They were recruited by the author via a face-to-face, direct approach in common space. Three representatives from property development firms were also invited to participate in the interviews. Interviews lasted 30 to 45 min. The participants’ names are not disclosed for anonymity and confidentiality purposes. Data were analyzed and categorized by themes. Table 1 shows the key findings.

Table 1.

Summary of key findings from the study of five high-rise housing estates in the Bangkok Metropolitan Area.

The analysis of the gated communities’ residents and their socializing habits takes into account the varying income levels, the history of private housing in Bangkok, the characteristics of the neighborhoods, and club services provided. This is to explain the complex dynamics of living in gated estates, sharing services with neighbors, and socializing with the non-residents.

5. The Bangkok Case Study

Regarding the study on gated communities in Bangkok and, in particular an analysis of who the residents of gated communities are, and the social encounters between the residents inside and the others outside, five high-rise gated housing estates situated in the Bangkok Metropolitan Area were selected:

- (1)

- (2)

- My Riverhouse: An 8-floor condominium by the Chao Praya River with two buildings and various unit types (studio, 1-bedroom, and 2-bedroom), with prices from 3 to 22 million baht (87,000–635,000 USD).

- (3)

- Tulip Tower: A 23-floor housing estate with 1-bedroom, 2-bedroom, and penthouse units, from 3 to 12 million baht (87,000–346,000 USD).

- (4)

- Botan House: A housing complex consisting of seven buildings, each with eight floors and studio, 1-bedroom, and 2-bedroom units, with prices ranging from 1.4 to 4 million baht (40,000–115,000 USD).

- (5)

- Khin I-Home: A 12-floor gated building of studio units, each with a selling price starting from 700,000 baht (20,000 USD).

These five high-rise gated housing estates were selected not only on the basis of various unit prices, but also the different characteristics of the neighborhoods. The five neighborhoods where the studied housing estates are located, as shown in Figure 1, include: Sukhumvit Thonglor, Klongsan, Bang Phlat, Bangkok Noi, and Rama IX. Narinn is situated in Sukhumvit Thonglor in Bangkok’s inner city. This area is popular for commercial activities, and it consists of old settlements of the middle class and expatriates. My Riverhouse is located in Klongsan, a neighborhood by the Chao Praya River. Klongsan has become popular for condominium development due to the recent extension of Skytrain, a public transport system, to the area. Tulip Tower is set in Bang Phlat where old shophouses, marketplaces, and several shopping malls are located. Several condo projects are being constructed in Bang Phlat after the extension of roads and a mass transit system to the west side of Bangkok. Botan House has its location in the Rama IX neighborhood, famous for its nightlife entertainment venue. Khin I-Home is in Bangkok Noi, Thonburi, an old, vibrant neighborhood with public hospitals, schools, traditional marketplaces, and shophouses.

Figure 1.

Map of five neighborhoods in the Bangkok Metropolitan Area in which the five studied high-rise housing estates are located. Source: Google My Maps.

Drawing on qualitative data gathered by document analysis, interviews with the residents and developers, and observations, as well as field notes from staying in these high-rise gated housing estates, Table 1 shows the key findings. To study the characteristics of selected gated housing estates, the following features were considered: Unit prices; location; security measures (walls, gates, and security guards); self-organized body and legal frameworks; club services and their accessibility; residents; and social interaction between the residents of high-rise housing estates and others living outside. The following sub-sections shall discuss the results of this research study in detail.

5.1. Gated Communities Where the Poor Live

The term “the poor” first needs to be defined. In June 2016, the Thai government launched a social welfare program providing benefits for the poor. Eligible citizens for the program are those of age 18 and older who earn less than 100,000 baht (2900 USD) a year. Citizens who earn less than 30,000 (865 USD) a year receive a one-time payment of 3000 baht (86.5 USD), while those who earn between 30,000 and 100,000 baht a year are paid 1500 baht (43.25 USD) (Government of Thailand 2018). This article acknowledges that there are other ways to define “the poor”. Specifically, the article, however, follows the official criterion and defines “the poor” as people who earn less than 100,000 baht (2900 USD) a year.

Khin I-Home is a high-rise housing estate situated in a small street amidst old settlements of one- or two-story self-built housing near two traditional marketplaces. Many of its residents are workers in the informal sector. They work as shop assistants or as laborers in nearby marketplaces. Most of them earn less than 100,000 baht a year. Hence, it is a high-rise residential building for the poor. Students and nurses working in nearby hospitals also live there. Khin I-Home has walls, gates, and two security guards. Residents are required to use key cards to enter the building. Parking is located on the first floor. In front of the parking floor, there is a vending machine for drinking water that both residents and non-residents living outside can use. On the second floor, there are a convenience store, a laundromat, two sets of tables and chairs for resting, and the office of the “nitibukkhon” (literally translated as “legal entity”) condominium administration, which is an autonomous body of the residents in charge of controlling the residents and governing the use of space. This second floor is where the residents encounter each other.

The residents seem to know their neighbors, as lots have lived in Khin I-Home for many years. Not all the residents are the owners of the units; some rent their flats. Aside from the proximity to their workplaces and study places, they chose to live in this condominium because it fulfils their needs for a mixture of safety, lifestyle, and privacy. A female resident in her forties told me:

“This is the best place in the area, although the building is quite old. There are actually other rental [self-built] houses offering a cheaper price in the “soi” [small street] but without a security guard and key card. You know? As a female seller [working in a nearby fresh marketplace], I have to go to the market at 3 o’clock so I have to live close by, in a safe place”.

Overall, Khin I-Home is walled and gated, as well as equipped with security guards, club services, and home rules for the residents.

Similar to Khin I-Home, Botan House has urban poor, as well as the lower middle class, living in it. This housing complex is set just behind the Royal City Avenue (so-called RCA), one of Bangkok’s largest entertainment venues with about 30 bars, pubs, dance clubs, and restaurants. Hence, it is not surprising that the majority of the residents of Botan House are people working in the service sector: Some own their units, some are renters.

One of the interviewed residents of Botan House who bought a studio unit fourteen years ago shared her experience that:

“I bought a unit here [in Botan House] in 2005 because it was affordable for me who at the time just started my first job [as an accountant]. Since then, I have paid mortgage installment around 6000 baht a month [174 USD] which is totally fine as I’m owning it, well, compared to the old place, before I moved in here, I paid 4000 baht [116 USD] monthly rent.”

Also renting a unit in this condominium are students, who like partying or who work part-time in the entertainment business. Similar to Khin I-Home, there is a convenience store, a laundromat, and a “nitibukkhon” office. Botan House also has a gym and garden between the buildings. The urban poor mostly live in 26 m2 studio units, which they share with another resident. Like the residents of Khin I-Home, those at Botan House chose this gated condominium because of safety and privacy reasons. Also, living in a high-rise gated housing estate fits their lifestyle as night-shift workers. A 21-year-old male resident expressed, “Compared with a detached house, a small unit in a condo does not require much cleaning and maintenance”. For female workers in particular, living nearby in a gated residence makes them feel safe when walking home in the middle of the night after finishing work.

Even though Botan House has walls, gates, and security guards, non-residents are allowed to enter the property to buy groceries or even wander in the garden. Data gathered by the author while staying in Botan House demonstrates that security guards never checked the ID cards of people entering this residential complex. Every evening, it was a group of children from a nearby low-income community by the railway coming to play in the garden. However, street vendors and cars without resident stickers are strictly prohibited inside the property.

This article aims to explore gated communities where people of varying income levels live. Based on their physical aspects, Khin I-Home and Botan House could be considered as “gated communities” in which the urban poor and the lower middle class live. However, these two residences also allow non-residents to use their amenities and facilities. In this respect, these condominiums differ from those gated communities covered in a large body of literature, which are understood to serve the rich and the middle class and prohibit non-residents from using their club amenities.

5.2. ‘Gating’ as a Standard Feature in High-Rise Housing Projects

Walls, gates, security guards, amenities, and home rules for residents have become a standard feature in all new high-rise private housing projects in Bangkok. The Thai Condominium Act (1979) encourages the construction of gated communities, as it requires developers to provide security and amenities to the residents, and it facilitates residents to set up a “nitibukkhon”. Ministerial Regulations No. 55 allows a maximum fence height of three meters. Developers told that nowadays every gated housing estate has walls, gates, and security guards; is equipped with amenities; and has a condominium “nitibukkhon”. The vice-president of a Bangkok-based property development firm added:

“‘Gating’ has become a standard component in all high-rise residential estate projects nowadays. It is like a swimming pool—you need to provide it. If you don’t, you are in trouble to market the property”.

Properties without gates are difficult to market, as the developer said. This has led to a situation in Bangkok where all new high-rise residential developments for all walks of life (low-income, middle-income, and high-income) are gated.

5.3. Social Encounters Between Gated Community Residents and Others Outside

Similar to other megacities, the majority of Bangkok residents were not born there. They came from other provinces to study or to work. Some decided to settle down permanently in Bangkok, while others planned to return to their hometown after saving money. For Thais, the “ban” (or village community) where they come from represents their roots and community. In their home villages, everybody not only knows everybody else but also their family and where they live. A male resident in his thirties living in Tulip Tower explained:

“In my home village, it was not just that you know Mr. B as ‘Mr. B’, but you can relate him to his family or the characteristic or location of his house. For example, when we refer to Mr. B, we say Mr. B who is a son of Mr. A, who has a big yellow house at the end of the road”.

Furthermore, people in villages also visit each other without any feeling of causing inconvenience. Some houses in the rural areas may be fenced (mainly to prevent animals from escaping), but they are not “gated”. Fences are never meant to prohibit people from entering. In light of this, all interviewees agreed that condominiums are different from “ban”; living in a condominium does not cause them to put down roots. However, they admitted that the physical form of gated housing estates does not prevent them from socializing with others living outside.

Most of the residents of Khin I-Home and Botan House interact daily with people living outside their condominiums, as well as with sellers and service providers in the neighborhoods. They do not see the amenities provided in their gated communities as any special advantage, because they can access cheaper and a greater variety of alternatives in the nearby marketplace, or buy goods from street vendors or in convenience stores. A female resident in her forties of Botan House reflected that the grocery shop inside her residence offers free-of-charge delivery service, but still she preferred going outside for more options of goods. In her words, she said:

“Even though, I can find essential goods, even cooked food, from the grocery shop in my building and I can also get free deliveries to my room, I usually buy things from vendors outside my condo. This is because there are many more choices of goods and services”.

For daily wage laborers, they prefer buying a small amount of groceries on a daily basis from convenience stores, some of which (like one near the Khin I-Home) even extend credit to customers, allowing them to take goods and pay later. By interacting with each other day after day, the social interaction between some residents of Khin I-Home and Botan House and the vendors in the neighborhoods has been developed from a vendor-client relationship into a meaningful friendship.

What is more, one of the most astonishing findings is that the landlords of two units in Khin I-Home are locals residing in self-built housing on the same street. This suggests that the relationships between the residents and outsiders are more complicated than those presented in the literature, and contradicts the categorical statements by Wissink and Hazelzet (2016) that the poor living outside of gated communities work as unskilled labor (such as maids, drivers, and cleaners) for the residents of gated communities.

Residents of My Riverhouse and Tulip Tower have less social interaction with the neighbors living outside their condominiums because they are not located in a vibrant residential area like Khin I-Home. The building next to My Riverhouse is a hotel, and Tulip Tower is set in-between other luxury condominiums. However, the residents of My Riverhouse and Tulip Tower like buying products and services from nearby marketplaces and on the street. They also enjoy chatting with vendors. Club services and amenities in their gated housing estates do not keep them inside their residences, nor do they fully satisfy their needs. Many residents often visit modern shopping malls to buy a variety of goods and to enjoy an air-conditioned space.

Narinn, located in Sukhumvit Thonglor, is equipped with a gym and swimming pool. There is also a convenience store inside this property. Sukhumvit Thonglor is a gentrified neighborhood in which old shophouses were demolished and replaced by high-rise housing estates, shopping malls, fancy restaurants, and bars. Mobile street vendors can be found in the neighborhood, but they are never allowed to enter the property. Hence, the degree of social interaction between the residents of Narinn and their neighbors outside are fewer than that found at the other condominiums.

The Bangkok case study shows that the amenities provided by gated communities do not lead residents to isolate themselves behind their gates, nor do they prevent them from seeking contacts, services, and goods outside. The reason for this is the continuation of “ban” or village community life. Another reason may be the landscape in Bangkok. With a density of 3631 denizens per square kilometer, the Bangkok Metropolitan Area is home to 5.5 million people (Bangkok Metropolitan Administration 2017). It is a metropolis characterized by spatial chaos: Hundreds of “soi”, smelly canals, traffic jams, busy streets, state-of-the-art shopping malls, tall office buildings, slums, condominiums, and highways (Vorng 2011). This chaos is a result of “unplanning”. Unrestricted development has produced commercial consumption space and mixed land use along the “soi”. Sukhumvit Soi 22, for example, is a place for “shop-house clusters, markets, apartments, compound houses, and several slum settlements” (Cohen 1985, as cited in Askew 2002, p. 245). On streets filled with citizens, residents, and consumers from all socioeconomic levels, Thais enjoy having street food or buying goods from street vendors as part of their urban life; as Sennett (1990, p. 123) puts it, the chaotic urbanscape can “turn people outward”. Given the cornucopia of attractions of this mixed landscape, it is no wonder that the residents of Bangkok’s gated communities in this study do not isolate themselves inside their gates. Thus, the Bangkok case study again reveals one of the shortfalls of the existing gated community literature, namely, neglect of the environment in which the gated community is embedded.

6. Conclusions

This article has investigated residential enclaves in Bangkok equipped with walls and gates, security guards, and club services. It began by tracing the history of enclosed residential space and the emergence of gated communities in Thailand. It then has considered Thai legislation governing the construction of gated communities and discussed urban planning and the city’s morphology. Drawing on qualitative data that the author collected in Bangkok, the article has discussed who lives in gated communities, as well as the social interaction between the residents of gated communities and others living outside the gates.

The historical view shows that enclaves of residential space in the form of enclosed royal residences is not new for Thailand. After WWII, Thailand followed the U.S. urban planning model, resulting in Bangkok becoming an automobile city. Gated communities emerged in the 1960s in the form of low-rise clusters of detached houses in suburban Bangkok. In the 1980s, gated communities in the form of high-rise condominiums or high-rise residential estates were developed. Today, the low-rise and the high-rise are the two types of gated communities found in Bangkok. This study focused on five high-rise gated housing estates located in different types of neighborhoods in the Bangkok Metropolitan Area. Amongst these five, the analysis of Khin I-Home and Botan House, in particular, reveals that the urban poor as well as the middle class live in these two gated condominiums; they socialize with others outside, and some are tenants of landlords who themselves live in self-built housing in the neighborhood.

Gated communities developed since the 1960s offer a new living experience to ordinary Thais, which is different from the earlier way of life. Traditional Thai settlements were village-based “ban” settlements, where people took care of each other and where the space was not exclusive. Hence, it may not be surprising that the residents of gated communities miss living in their home village and thus continue their “village way of life” by seeking contacts with people outside the gates. As this study shows, the services and amenities found inside the gates may tempt gated community residents to stay inside their walled housing estates and take distance from neighbors outside, but the socio-spatial conditions of neighborhoods around gated communities and memories of the communal village way of life exert a pull on residents to go outside and mingle with the people beyond the gates.

Urban processes in the Global South, whether they are regarding land, housing, planning or governance, cannot be simply explained as “a postscript to the urban transformations of the North Atlantic” (Robinson and Roy 2016, p. 181). Like some gated communities in the Global South, for example, China (Douglass et al. 2012) and Israel (Rosen and Razin 2008), Khin I-Home and Botan are less strictly enclosed and they allow outsiders to use their club services and amenities.

This Bangkok study, together with numerous previous studies of gated communities, show that enclosed private housing is rather ubiquitous. Three results of this study, however, question the conceptualization of “gated communities” in previous research. First, in Bangkok the poor also live in gated communities, which contradicts the assumption of previous studies that residents of gated communities are the affluent and the middle class. Second, Khin I-Home and Botan House, the two gated communities that allow non-residents to use their amenities, challenge the assumption of the exclusivity of club services and demonstrate that gated communities can offer welfare services to the public. Third, “gating” as a standard feature in new housing estates in Bangkok contradicts the whole idea of a gated community being a distinctive form of living.

These anomalies give cause to interrogate the usefulness of the whole concept of “gated communities”. Perhaps its usage should be limited. In social sciences, and specifically urban studies, recent debates on global urbanisms and urban theory have urged urban scholars and researchers to question the universalizing “claims of critical Anglophone urban theory” because this may be “an incipient monism” (Leitner and Sheppard 2016, p. 231). It is certain that “urbanization may indeed take a global form” and “capitalism is undeniably global”; nonetheless, “universality of such processes is another matter” (Roy 2016, p. 203). Therefore, the application of the concept of “gated communities” has its limits and an analysis of gated communities should pay attention to local and historical conditions.

Funding

This research was funded by the Academy of Finland.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Anne Haila, my supervisor, for her advice and suggestions; my colleagues at the Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Helsinki for their constructive comments; and, the anonymous reviewers for their valuable feedback in shaping this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Anderson, Benedict. 1978. Studies of the Thai State: The State of Thai Studies. In The Study of Thailand: Analyses of Knowledge, Approaches and Prospects in Anthropology, Art History, Economics, History, and Political Science. Edited by Eliezer B. Ayal. Southeast Asia Series; Athens: Ohio Centre for International Studies, No. 54. pp. 193–247. [Google Scholar]

- Askew, Marc. 2002. Bangkok: Place, Practice and Representation, 1st ed. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson, Rowland. 2008. The Politics of Gating (A Response to Private Security and Public Space by Manzi and Smith-Bowers. European Journal of Spatial Development. Available online: http:www.nordregio.se/ESJD/refereed22.pdf (accessed on 18 May 2019).

- Atkinson, Rowland, and Sarah Blandy. 2005. Introduction: International Perspectives on the New Enclavism and the Rise of Gated Communities. Housing Studies 20: 177–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, Rowland, and John Flint. 2004. Fortress UK? Gated Communities, the Spatial Revolt of the Elites and Time–Space Trajectories of Segregation. Housing Studies 19: 875–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, Chris, and Pasuk Phongpaichit. 2009. A History of Thailand, 2nd ed. Melbourne: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ballard, Richard. 2004. Assimilation, Emigration, Semigration and Integration: ‘White’ Peoples Strategies for Finding a Comfort Zone in Post-Apartheid South Africa. In Under Construction: ‘Race’ and Identity in South Africa Today. Edited by Natasha Distiller and Melissa E. Steyn. Heinemann: Johannesburg, pp. 51–60. [Google Scholar]

- Bangkok Metropolitan Administration (BMA). 2017. Population of BMA 2560. Available online: http://www.bangkok.go.th/upload/user/00000130/planing/pop%20bma%202560.pdf (accessed on 18 May 2019).

- Bello, Walden, Shea Cunningham, and Li Kheng Poh. 1998. A Siamese Tragedy: Development and Disintegration in Modern Thailand. London and New York: Zed Books Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Blakely, Edward J., and Mary Gail Snyder. 1997. Fortress America: Gated Communities in the United States. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brunn, Stanley D., and Klaus Frantz. 2006. Introduction [Special Issue: Gated Communities: An Emerging Global Urban Landscape]. GeoJournal 66: 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buch-Hansen, Mogens. 2001. Local Institutions and the Political Process of Controlling Land and Resources in Thailand. International Studies. Denmark: Roskilde University, Available online: http://www.niaslinc.dk/gateway_to_asia/nordic_webpublications/x483467005.pdf (accessed on 18 May 2019).

- Caldeira, Teresa P. R. 2000. City of Walls: Crime, Segregation, and Citizenship in São Paulo. Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chaloemtiarana, Thak. 2007. Thailand: The Politics of Despotic Paternalism. Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Erik. 1985. A Soi in Bangkok: The Dynamics of Lateral Urban Expansion. Journal of the Siam Society 73: 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Coy, Martin, and Martin Pöhler. 2002. Gated Communities in Latin American Megacities: Case Studies in Brazil and Argentina. Environment and Planning B: Urban Analytics and City Science 29: 355–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darcy, Michael, and Gabrielle Gwyther. 2012. Recasting research on ‘neighbourhood effects’: A collaborative, participatory, trans-national approach. In Neighbourhood Effects Research: New Perspectives. Edited by Maarten van Ham, David Manley, Nick Bailey, Ludi Simpson and Duncan Maclennanpp. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 249–66. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, Mike. 1990. City of Quartz: Excavating the Future in Los Angeles. London and New York: Verso. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Land. 2015. Condo Search. Information Support Center. Available online: http://condosearch.dol.go.th/Search/district.php (accessed on 7 January 2019).

- Douglass, Mike, Bart Wissink, and Ronald van Kempen. 2012. Enclave Urbanism in China: Consequences and Interpretations. Urban Geography 33: 167–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupont, Véronique. 2016. Secured Residential Enclaves in the Delhi Region: Impact of Indigenous and Transnational Models. City, Culture and Society 7: 227–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durington, Matthew. 2006. Race, Space and Place in Suburban Durban: An Ethnographic Assessment of Gated Community Environments and Residents. GeoJournal 66: 147–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falzon, Mark-Anthony. 2004. Paragons of Lifestyle: Gated Communities and the Politics of Space in Bombay. City & Society 16: 145–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, Hildebrand. 1999. Designing the City: Towards a More Sustainable Urban Form. London and New York: E & FN Spon. [Google Scholar]

- Gans, Herbert J. 1968. People and Plans: Essays on Urban Problems and Solutions. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Thailand. 2018. Matthakan Sawadikan Heangrath Nawattakam Poei Kaepanha Khuamyaakchon [A Measure of State Social Welfare: The Innovation to Eradicate Poverty]. Thai Khu Pha April–June: 6–11. Available online: https://spm.thaigov.go.th/FILEROOM/spm-thaigov/DRAWER004/GENERAL/DATA0000/00000438.PDF (accessed on 7 January 2019).

- Grant, Jill. 2005. Planning Responses to Gated Communities in Canada. Housing Studies 20: 273–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, Jill, and Lindsey Mittelsteadt. 2004. Types of Gated Communities. Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design 31: 913–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hook, Derek, and Michele Vrdoljak. 2002. Gated Communities, Heterotopia and A “Rights” of Privilege: A ‘Heterotopology’ of the South African Security-Park. Geoforum 33: 195–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasch, Christopher. 1995. The Revolt of the Elites and the Betrayal of Democracy. New York and London: W.W. Norton & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Lees, Loretta. 2008. Gentrification and Social Mixing: Towards an Inclusive Urban Renaissance? Urban Studies 45: 2449–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leisch, Harald. 2002. Gated Communities in Indonesia. Cities 19: 341–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitner, Helga, and Eric Sheppard. 2016. Provincializing Critical Urban Theory: Extending the Ecosystem of Possibilities. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 40: 228–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemanski, Charlotte, and Sophie Oldfield. 2009. The Parallel Claims of Gated Communities and Land Invasions in a Southern City: Polarised State Responses. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 41: 634–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, Setha M. 1997. Urban Fear: Building the Fortress City. City & Society 9: 53–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, Setha M. 2001. The Edge and the Center: Gated Communities and the Discourse of Urban Fear. American Anthropologist 103: 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, Setha. 2003. Behind the Gates: Life, Security, and the Pursuit of Happiness in Fortress America. New York and London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Mabin, Alan. 2014. Grounding Southern City Theory in Time and Place. In The Routledge Handbook on Cities of the Global South. Edited by Susan Parnell and Sophie Oldfield. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 21–36. [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie, Evan. 2005. Constructing the Pomerium in Las Vegas: A Case Study of Emerging Trends in American Gated Communities. Housing Studies 20: 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, Russell David. 2015. Gentrification and Displacement: The Impacts of Mass Transit in Bangkok. Urban Policy and Research 33: 472–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morange, Marianne, Fabrice Folio, Elisabeth Peyroux, and Jeanne Vivet. 2012. The Spread of a Transnational Model: ‘Gated Communities’ in Three Southern African Cities (Cape Town, Maputo and Windhoek). International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 36: 890–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mycoo, Michelle. 2006. The Retreat of the Upper and Middle Classes to Gated Communities in the Poststructural Adjustment Era: The Case of Trinidad. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 38: 131–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nartsupha, Chatthip. 1999. The Thai Village Economy in the Past. Translated by Chris Baker, and Pasuk Phongpaichit. Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books. First published 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Potter, Jack M. 1976. Thai Peasant Social Structure. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pow, Choon-Piew. 2009. Gated Communities in China: Class, Privilege and the Moral Politics of the Good Life. Oxon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Real Estate Information Center. 2015. Housing Statistics. Bangkok: The Government Housing Bank Thailand. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, Marion. 2007. Sharing Space: Urban Design and Social Mixing in Mixed Income New Communities. Planning Theory & Practice 8: 183–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, Jennifer, and Ananya Roy. 2016. Debate on Global Urbanisms and the Nature of Urban Theory. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 40: 181–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, Gillad, and Eran Razin. 2008. Enclosed Residential Neighborhoods in Israel: From Landscapes of Heritage and Frontier Enclaves to New Gated Communities. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 40: 2895–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, Ananya. 2016. Who’s Afraid of Postcolonial Theory? International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 40: 200–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salcedo, Rodrigo, and Alvaro Torres. 2004. Gated Communities in Santiago: Wall or Frontier? International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 28: 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, Thomas W., Robert E. Lang, and Dawn M. Dhavale. 2005. Security Versus Status? A First Look at the Census’s Gated Community Data. Journal of Planning Education and Research 24: 281–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sennett, Richard. 1990. The Conscience of the Eye: The Design and Social Life of Cities. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. [Google Scholar]

- Sintusingha, Sidh. 2011. Bangkok’s Urban Evolution: Challenges and Opportunities for Urban Sustainability. In Megacities: Urban Form, Governance, and Sustainability. Edited by André Sorensen and Junichiro Okata. Tokyo: Springer, pp. 133–62. [Google Scholar]

- Sintusingha, Sidh, and Morteza Mirgholami. 2013. Parallel Modernization and Self-Colonization: Urban Evolution and Practices in Bangkok and Tehran. Cities 30: 122–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, Tom. 2013. Expulsions from Public Housing: The Hidden Context of Concentrated Affluence. Cities 35: 384–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suwannasang, Veeramon. 2015. Urban Gating in Thailand: The New Debates. In Beyond Gated Communities. Edited by Samer Bagaeen and Ola Uduku. Oxon and New York: Routledge, pp. 90–113. [Google Scholar]

- Tambiah, Stanley Jeyaraja. 1970. Buddhism and the Spirit Cults in North-East Thailand. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- van Ham, Maarten, David Manley, Nick Bailey, Ludi Simpson, and Duncan Maclennanpp. 2012. Neighbourhood Effects Research: New Perspectives. Dordrecht: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Vorng, Sophorntavy. 2011. Bangkok’s Two Centers: Status, Space, and Consumption in a Millennial Southeast Asian City. City & Society 23: 66–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirth, Louis. 1938. Urbanism as a Way of Life. The American Journal of Sociology 44: 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wissink, Bart, and Arjan Hazelzet. 2016. Bangkok Living: Encountering Others in a Gated Urban Field. Cities 59: 164–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wissink, Bart, Ronald van Kempen, Yiping Fang, and Si-ming Li. 2012. Introduction—Living in Chinese Enclave Cities. Urban Geography 33: 161–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | The term “informal” settlement has been widely used to refer to a type of human settlement outside the “formal” control of authorities. The word “informal” is problematic, however, as the boundaries between “formal” and “informal” are unclear. Town planners and policymakers tend to see urban informalities as a threat to a planned city and attempt to remove them, leading to evictions and the displacement of the poor living in “informal” settlements. |

| 2 | http://investor.raimonland.com/shareholdings.html (accessed on 30 May 2019) |

| 3 | The names of the studied gated housing estates have been changed for the anonymity and confidentiality of the informants. Other information is accurate. |

| 4 | The data on unit prices were gathered from advertisements posted on bulletin boards at the studied gated housing estates. |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).