Abstract

This article explores recent transformations in retail in Lisbon. We analyse a gentrified traditional retail market located in Campo de Ourique, Lisbon and study the relationship between this retail precinct and the surrounding commercial fabric. Through a set of enquiries on local retailers, our findings show an absence of relationship between the market and the remaining shopping district, insofar as Campo de Ourique market can be designed as a fortress. There is a social implication of this finding in the sense that the gentrification of the traditional retail market is severely detrimental to the local population quality of life. In terms of policy implication, this article demonstrates that this kind of project produces different results from some well-known retail-led urban regeneration projects and, as such, should not be used as a benchmarking for other areas.

1. Introduction

Looking at cities, one may find a surprising space that does not stop to amaze us. Since ancient times, urban spaces have been important elements in the development of societies (Davis 2005). This conception of something idyllic finds, quite often, expression in the forms and buildings of urban centres. This representation is not merely aesthetic. On the contrary, it is deeply rooted and represents societal characteristics and allows us to understand them (see Pacione 2005). To this purpose we can look at ancient Greek and Roman cities and apprehend some aspects of their society; for instance how public squares were used by citizens for political meanings, or how baroque architecture intended to highlight the relevance of individuals and institutions, as Versailles, in Paris, may enlighten us (Lamas 2004). In his XVI century book “Utopia”, Thomas More versed about this relationship between cities and societies (Mumford 2005). In this article we will analyse retail, a vibrant sector that so well embodies the urban environment. Despite a private sector, retail plays an activity of public interest, the supply of its population. It is this ambiguity that characterises the sector, orbiting between its private genesis and its function with public interest. Recent changes in some neighbourhoods and districts are, however, quickly changing the face of the retail fabric and the consumers they intend to supply. Some of these changes have been occurring within the boundaries of gentrification (Guimarães 2018), widely understood as the displacement of low-income residents by high-income residents (Ding et al. 2016).

Although change is a common feature of retail (Guimarães 2019), we have recently seen a rising scientific interest on the subject of retail gentrification (Mermet 2017). Nonetheless, existent literature on the subject is still rather scarce, most likely due to the belief that the change of the commercial fabric is due to previous changes in the social fabric of a given area (Hubbard 2017). Additionally, most studies on retail gentrification have been focusing on the transformations occurring at a neighbourhood scale, such as Zukin et al. (2009) study of Brooklyn and Harlem in New York, or on the gentrification of specific retail precincts, of which the work of Guimarães (2018) focused on the gentrification of a traditional retail market is an example. In this article we intend to go further from existent literature. Supported by a case study methodology, we will study Campo de Ourique market, one of the two intensely gentrified traditional retail markets in Lisbon, representative of the delegation of powers and responsibilities from the public to the private sphere (see Reyes-Menedez et al. 2018), and analyse the relationship it has with the shopping district in its surroundings. Campo de Ourique is an old neighbourhood of Lisbon, with a large commercial fabric, thus, any kind of impacts arising from the market are most likely to be uncovered, making this case study particularly interesting. Although the rehabilitation of this retail precinct did not share the same goals of some well-known retail-led urban regeneration projects, i.e., the rehabilitation or edification of a certain retail precinct aimed to produce direct and indirect multiplier effects in the broader shopping district (Glasson and Wood 2009; Guimarães 2017), it may also produce similar impacts. This article aims to produce novel knowledge on retail gentrification by studying the relationship and impacts that a certain gentrified retail precinct induces in the broader shopping district where it is located. This research is framed by the following research question: What is the relationship between gentrified Campo de Ourique traditional retail market and the commercial fabric of the respective neighbourhood? We argue that there is symbiotic relation through which the traditional neighbourhood retailers benefit from the increase of visitors that stems from the attractiveness of Campo de Ourique market but, at the same time, ends up withdrawing some of the regular customers who are now attending the gentrified retail precinct. The article is structured as follows: the next section is devoted to the theoretical analysis. Next, we will clarify the methodology that will be used in our empirical study. Finally, we will discuss our findings and draw some conclusions.

2. Exploring Retail Gentrification

Gentrification is not a recent concept. It was first coined by Ruth Glass in the 1960s to describe the transformation that was occurring in working-class neighbourhoods of London. Since then, “the extent and meaning of gentrification have changed remarkably” (Slater et al. 2004, p. 1143). Although there is no single hegemonic definition of gentrification and some even question its necessity (Bounds and Morris 2006), it can be broadly understood “as the transformation of inner-city working-class and other neighbourhoods to middle and upper-middle-class residential, recreational, and other uses […]” (Smith 1987, p. 462), provoking a change in the social composition of the area. However, gentrification is not easy to be proven because the underlying consequences of gentrification, namely the moving out of population, can be due to personal choices from those individuals and not because a broader process of gentrification may be occurring. In their study, Freeman and Braconi (2004) also stress that further evidences of causality between neighbourhood gentrification and displacement must be developed. Furthermore, this is enhanced by the fact that it is not easy to track displacees that prove otherwise. This is why, according to Atkinson (2000, p. 150), “it is much easier to research the more tangible manifestation of gentrification, given that it is an observable end-state predicated on the removal or voluntary migration of previous residents”. Associated with gentrification is the rent gap thesis. Smith (1987, p. 462) defined it as “the gap between the actual capitalized ground rent (land value) of a plot of land given its present use and the potential ground rent that might be gleaned under a ‘higher and better’ use”. In a residential neighbourhood in transition it means that the new upper-class residents will pressure the available housing stock, “placing pressure on prices and making it attractive for landlords to increase rents” (Meltzer and Ghorbani 2017, p. 53). However, as discussed by Smith (1987), the mere existence of a rent gap in a given area does not mean that a gentrification process is bound to occur. Still, areas with a significant rent gap are more susceptible to suffering from gentrification.

In recent times, gentrification has entered into the discourse of retail change. Until recently, retail was at best analysed as a secondary feature that reflected the overall condition of a given area but without being recognised that retail could lead the process of change (Hubbard 2017). The transposition of gentrification into the geographies of retail has had the objective to analyse the transformations of the commercial fabric, both in some commercial districts as in some residential neighbourhoods. In both, what is at stake is the ability of long-time and disadvantaged consumers to still be able to supply themselves in the new retail stores or as said by Martinez (2016, p. 52) upon his study of the transformation occurring in Guozijian, Beijing: “commercial gentrification shows just how contradictory the transformations under way are. It excludes the needs of the local population and caters only to those of visitors and new residents”. A study from Gotham (2005) analysed the transformation of the French Quarter in New Orleans, in which tourism-related stores replaced traditional working-class stores, which resembles with similar developments in different countries (see Gravari-Barbas and Guinand 2017). The change in the commercial fabric is often viewed positively by permanent residents and business owners (Zukin et al. 2009). By the former, because it gives them the feeling that their neighbourhood is more attractive, even if they are not able to buy in the new stores. By the latter, because there is an increase of the vitality in the area although new consumers move especially to the new stores that quite often are no more than pastiches of the really authentic and traditional stores. Ironically, coated under an aura of authenticity (see Zukin 2008, 2011), this new gentrifying stores contribute to the decline of the ones they somehow intend to copy.

Not always the private sector acts alone as a driving force of retail gentrification. Very often, public authorities plays an important role in the process, mainly through public urban regeneration initiatives that trigger gentrification, whose correlation has been demonstrated in studies such as Guzey (2009) that focusing on Ankara, Turkey, stated that “urban regeneration is a primary tool in the restructuring of cities […] so can be defined as a government-assisted gentrification project”, or Lim et al. (2013) that uncovered how an urban regeneration project in Seoul’s central business district led to an increase of prices and to retail gentrification. A similar conclusion was drawn by Ozdemir and Selçuk (2017) in their study of the impacts of pedestrianisation and other improvements performed in the district of Kadıköy, in Istanbul.

Alongside with the gentrification of the commercial fabric of some inner-city shopping districts, the recent rehabilitation of traditional retail markets that has been showing clear signs of retail gentrification have been a preferred target of study by researchers (see Gonzalez 2018). Geographically, the growing interest in the rehabilitation of markets is not confined to the European context. Some literature shows us that very similar developments of retail gentrification in traditional retail markets are taking place in different countries of Latin America (Argentina (Rosa 2017), Brazil (Pereira 2017; Vargas 2017) and México (Delgadillo 2017)) and other regions of the world (see Istanbul for example (Bearne 2017)). An old retail concept, endowed with a notable importance in the past, it enters in decline when, simultaneously, was subject to several years of divestment and new retail concepts emerged and spread. Because of this abandonment to which they were subjected, the necessary conditions were created so that there was a rent gap that encouraged the recent investment (Guimarães 2018), which fostered the rehabilitation of several of this kind of retail precinct (Cordero and Eneva 2017). This discourse is well explained in Gonzalez and Waley’s (2013, p. 965) study of Britain’s traditional retail markets, stating some concerns that recent rehabilitation of these retail precincts is

“… putting them beyond the reach of their predominantly working-class clientele and turning them into a new playground for those members of the middle classes who seek authenticity and alternative consumption possibilities.”

Although not all declined traditional retail markets may be subject of gentrification, the existence of a rent gap does seem to matter. In the recent study from Gonzalez and Dawson (2018), the three retail precincts used as case studies have been previously subject of divestment and this situation has been used to partially justify its rehabilitation. Similar conclusions were withdrawn by Guimarães (2018), in this author’s analysis of traditional retail markets in Lisbon. Part of this recent evolution relates with the growing numbers of tourists, in a process that is commonly named as touristification (Barata-Salgueiro et al. 2017) or tourism gentrification (see Gravari-Barbas and Guinand 2017, for further examples on the application of this concept). This process mainly affects traditional retail markets that are located in or near the main tourist attractions. Often, the spaces themselves turn out to be also a tourist attraction, such as La Boqueria and Santa Caterina markets in Barcelona (Frago 2017). The transformation of the retail fabric, becoming totally oriented to tourism, causes the resident population to stop having places where they can supply, deeply interfering with their quality of life (Cocola-Gant 2018). Besides, well located in the dense urban fabric, these retail precincts are also relevant because of the social bounds established inside these spaces, providing them with “vivid and inclusive public spaces” (Schappo and Melik 2017, p. 318). Thus, traditional retail markets must be seen not only as a retail precinct where transactions take place but also as spaces where social interaction happens (Gómez and Nicolas 2017), constituting themselves, as public spaces that help in the formation of social and community bonds.

A study from Gvion (2017) shows how the change in the social composition of the district where Carmel market (Israel) is located induced deep changes in the selling techniques and products sold to adjust to the new consumers: “The Carmel market in Tel Aviv is an excellent example of how public space is produced and transformed in reaction to processes that occur outside the space” (Gvion 2017, p. 362). This is in line with aforesaid traditional understandings of retail gentrification, in which retail assumes a reactive nature to changes induced by other sectors (Hubbard 2017). In this article we intend to change the perspective of analysis, i.e., to study how a gentrified retail precinct influences the retail fabric of the surrounding area. By doing so, our research finds some similarities to the approach followed in some retail-led urban regeneration studies, linking the latter with retail gentrification (see for instance Jayne 2006; Lee 2013; Tallon 2008). Within the evolutionary pattern of retail, older retail concepts, practices and techniques are affected. Some fall into disuse, lose viability and decline. Due to the strong connection between retail and the vitality of the spaces where the sector is more represented, the decline of the commercial fabric is usually accompanied by the decline of the respective urban space. When the innovative processes of retail became more intense, this relation of causality also began to be understood in the opposite direction, i.e., if retail can provoke and/or intensify the decline of a certain area, it can also contribute to its revitalisation (Barata-Salgueiro and Cachinho 2009). It is within this understanding that in the last decades several projects of retail-led urban regeneration took place. Focusing on the projects anchored in the implementation or rehabilitation of retail precincts one may enhance the studies of Lowe (2005a, 2005b, 2007) regarding the opening of West Quay shopping centre in Southampton as a part of a broader urban regeneration process, through which the city rose in the national ranking of best destinations for shopping (Lowe 2005b). Regarding the impact in the surroundings, the studies are not conclusive. The author points out that at “first glance … West Quay appears as a “fortress”” (Lowe 2005a, p. 661) because of the disconnection it apparently has with the outside of the shopping centre. As the author has assumed, the use of this term refers to Christopherson (1994, p. 410), who described the “fortress character of urban development” as a response to cities increasingly characterised by social and economic inequalities. Resuming the study of shopping centre West Quay, Lowe (2005a) also shows the results of a survey, in which 2/3 of consumers also intended to shop in the traditional shops outside the shopping centre and provoked changes in the footfall of the area. Although there was an overall increase of the vitality, it became circumscribed in a small number of streets that are closer to the new retail precinct, diminishing the vitality of streets further away. Furthermore, although there were some variations in the vacancy rate in streets near the West Quay, causality was not proven. This retail-led urban regeneration project fit the regeneration thesis as discussed by Whysall (1995), according to whom the development of a new retail precinct will attract consumers from further apart locations which will benefit not only the new development but also the already existing traditional retail fabric.

3. Research Methods

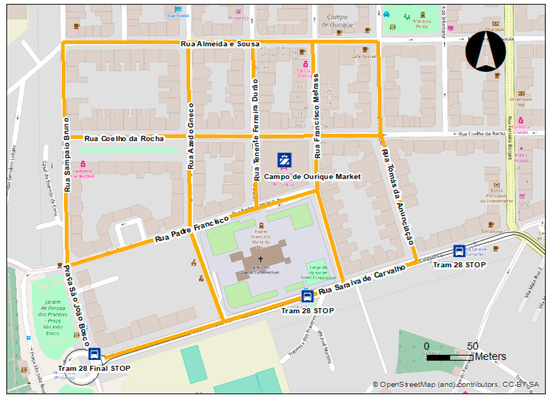

In this article we intend to analyse the impacts that a gentrified traditional retail market provoke in the surrounding area, thereby, establishing a link between retail gentrification and impacts of retail-led urban regeneration. We use a case study approach to capture the holistic complexity of the subject in analysis (see Tight 2017). Our case study is Campo de Ourique market (henceforth just called “market”), a traditional retail market located in an historic residential neighbourhood of Lisbon, target of a rehabilitation project in the new millennium that culminated in its gentrification. Interviews were performed on retailers operating in the analysed area. As stated by Mclafferty (2005), this is a valid and useful method to find people’s opinion on a specific subject that could not be obtained in another existent published source. In this research, the sampling was used to choose the streets that were analysed. To this purpose we have chosen ten streets that constitute the main surrounding of Campo de Ourique market (Figure 1). This option was made taking in consideration the work of Lowe (2005a). By using another study as a reference, the findings of this article will contribute to the identification of empirical regularities, identified by Tsang (2013) as one way of theorising from case studies.

Figure 1.

Streets where interviews were performed. Source: OpenStreetMap. Treatment performed by the author.

Regarding the number of performed interviews, considering that some retailers might not be willing to collaborate with our study, we chose not to sample but rather target all existent retailers. Also taking into consideration the results and discussion of Lowe (2005a) study, two different interviews were designed. One, targeted at retailers that were already operating before the rehabilitation of the market, composed of two questions: (i) Has the rehabilitation of the market had any impact on the neighbourhood or on your store? (ii) Does your business benefit in any way from the rehabilitated market? The second interview targeted retailers that opened their store after the market rehabilitation and also two questions were made: (i) Is the opening of business somehow due to the rehabilitation of the market and the consequent increase in the attractiveness of new pedestrians to the area? (ii) Does your business benefit in any way from the rehabilitated market? Questions were open-ended to “allow participants to craft their own responses” (Mclafferty 2005, p. 89). By allowing respondents to elaborate their answer we intended to obtain more meaningful information. A prior classification of possible answers entailed the risk of losing information that could be significant for the understanding of the subject under study. To be able to better withdraw this information potentially valuable and aware that it would be time consuming, we chose to perform all interviews in person, in a fieldwork that took place during May and June 2018. Although time consuming, this option was chosen to obtain more meaningful responses. In all interviews, the anonymity of the respondents was safeguarded. The data collected from interviews was classified into different categories using a quantitative approach (Kitchin and Tate 2000). Furthermore, due to the absence of updated secondary data regarding the tenant mix of the area, the fieldwork involved the collection of primary data about the composition of this area’s commercial fabric. This data was further treated and compared with a previous database from 2007 collected by the Lisbon municipality. Because of the limitation in terms of availability of data, information from the fieldwork was gathered by the author and synthesized in two tables (Table 1 and Table 2) and further discussed.

Table 1.

Evolution of the retail fabric of the area surrounding Campo de Ourique market.

Table 2.

Synthesis of interviews performed on retailers.

4. Case Study

4.1. Designing the Background in Lisbon

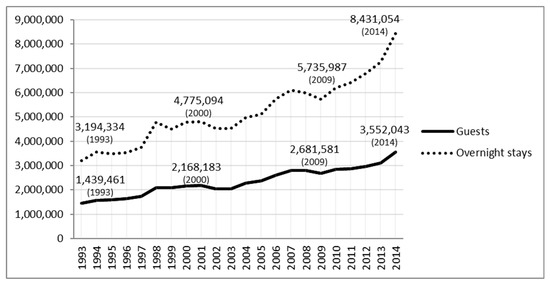

In recent decades, Lisbon has experienced deep changes. In the end of last century, the loss of population from Lisbon municipality was followed by the functional decline of its main historical centre. In the late 1990s, the Lisbon World Exposition led to the renovation of a former industrial site creating a new centrality in the city. Already during that decade and in the period that followed, simultaneously with the spread of shopping centres in peripheral areas, several retail-led urban regeneration projects were developed to revitalise the commercial fabric of the main city centre (Guimarães 2017). Following plans to reinforce Lisbon as a tourist destination, in the end of the 2000s some effects began to be felt (Barata-Salgueiro et al. 2017). As we can see in Figure 2, the evolution of guests and overnight stays in hotels in the municipality of Lisbon has had a stable evolution since the early 1990s. However, it is already in the 2000s that the numbers increased significantly. The exception is 2008 and 2009 due to the economic crisis.

Figure 2.

Evolution of guests and overnight stays in hotels in Lisbon. Source: Observatório de Lisboa (2015). Treatment performed by the author.

In addition to the stays in hotels, the growth of informal accommodation, mainly performed in expanding platforms such as Airbnb, made it evident that this growth in the volume of tourists has been even more significant. Although there is not complete information about the length of the offer available in these platforms, some studies (Barata-Salgueiro et al. 2017; Mendes 2018; Pavel 2015) revealed the significance of this offer. All of these changes, placed under the umbrella designation of touristification, have been crucial in triggering the gentrification seen in sectors such as housing and retail. Related to the latter, Barata-Salgueiro (2017) verified that relevant changes in the commercial fabric of the main historical centre of the city are occurring, adjusting to tourism-related activities and clients. Traditional retail markets are one retail concept where changes have been visible. The recent intervention in these retail precincts in Lisbon was influenced by the previous rehabilitation of similar retail precincts in other cities, mainly the ones located in Barcelona (see Frago 2017) but also the ones that were targeted for rehabilitation in Madrid, such as San Antón market in Chueca district (Câmara Municipal de Lisboa 2016). Similarities between the rehabilitation of traditional retail markets in Lisbon and the same process in Barcelona and Madrid can be found. As studied by Mateos (2017) in the case of San Antón, there is an elitization of the commercial fabric. Former stores were displaced to bring space for new shops, especially hostelry and gourmet stores oriented to new higher-income consumers. As verified by that author, the new clients only visit the market to attend new restaurants, cafes and similar stores. Regarding the traditional stores, new clients only go to them “to buy some whim, abounding the cases where they visit them only once, walk, photograph and do not consume anything” (Mateos 2017, p. 12 (author own translation)), in a development that finds similarity to what happens in some traditional retail markets in Lisbon. Deepening the analysis of this city, Guimarães (2018) verified that old retailers continued to operate in traditional retail markets. However, in some, the physical space they occupy is of lesser relevance. Thus, although they have not been formally or directly displaced, some conditions were created for them to lose viability and, with time, cease operations. The justification for the recent intervention in traditional retail markets in Lisbon is the same used in Barcelona, where public authorities used the discourse of physical decline of the retail precincts (Cordero 2017). Nonetheless, as in Barcelona, it was the public divestment that led to that decline (Guimarães 2018).

4.2. Campo de Ourique

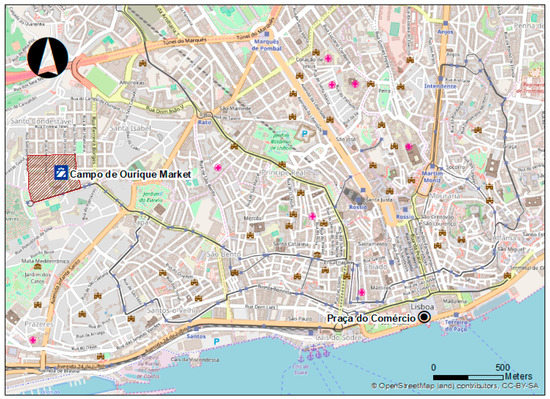

Campo de Ourique is a Lisbon traditional residential neighbourhood, located northwest of the traditional city centre (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Location of Campo de Ourique market in relation to the traditional city centre (Praça do Comércio). Source: OpenStreetMap. Treatment performed by the author.

Its inhabitants possess a strong sense of identity (Cachinho 2014) and the commercial fabric has traditionally been characterised for its diversity and density allowing the local population to be able to supply without having to go to out-of-neighbourhood shops (Guimarães et al. 2011). Campo de Ourique and Ribeira markets were the first two traditional retail markets to be rehabilitated within the wider process that is occurring in Lisbon, in 2013 and 2014, respectively. They are also the most emblematic because the intervention followed the same model already implemented in the aforementioned similar retail precincts of Barcelona and Madrid. Eventually, the impacts were the same as in their models, resulting in two gentrified retail precincts. Originally, Campo de Ourique market was inaugurated in 1934. After severe divestment that culminated in its physical and economic degradation, the building was targeted for rehabilitation in 1991 and 2010. In 2013, through benchmarking and using San Miguel market, in Madrid, for that purpose (Câmara Municipal de Lisboa 2016), the company MCO began to explore the retail precinct. This was done through a concession right given by the City Council to that company, being in accordance with the Lisbon model that defines the whole process of rehabilitation of traditional retail markets in Lisbon (Guimarães 2018). Although not being a central neighbourhood, Campo de Ourique is able to attract a noteworthy volume of tourists. This is due to the fact that the most well-known tram route of the city, the tram 28, finishes its route in one of the limits of the neighbourhood. So, in addition to passing through Campo de Ourique, being the final station, passengers, mostly tourists, are forced to leave the tram even if they want to do return path (see Figure 1). The market management company took advantage of this situation and produced a touristic guide exclusive for the tram 28 marketing Campo de Ourique market, thus, placing this retail precinct within one of the main touristic routes of the city.

4.3. Results of the Fieldwork

The commercial fabric of the analysed streets remained stable considering the tenant mix of 2007 and 2018 (Table 1). Overall, in terms of size, it went from 150 to 144 stores, respectively. This evolution cannot be considered as insightful to attest the vitality and viability of the area, if one considers that retail is characterised by its dynamism and the decrease of only six stores is not sufficient for such confirmation. Data related with the opening and closure of stores further demonstrates this. Of the 150 stores that were functioning in 2007, more than half (78) are not operating in 2018. On the other side, 72 stores are still functioning, at least, since 2007. Taking in consideration the data from the older database, in 2018 there are 72 new stores. Looking into detail to the evolution of the different retail typologies, one may see a diversified tenant mix and, to some extent, similar in both years. Major change concerns the gain of importance of stores related with services and opposite evolution relating retail, which is in accordance with contemporary changes in the tenant mix of main centres of commerce (Guimarães 2019).

During the fieldwork, 99 out of the possible 144 interviews were successfully conducted on retailers located in the streets surrounding Campo de Ourique market (Table 2). As initially foreseen and described in the methodology section, it was not possible to carry out interviews in all establishments for two reasons. First, because some retailers did not wish to cooperate with the study. Second, because in some stores only the manager was available and it was not possible to contact the owner. Moreover, in these cases, managers were not willing to collaborate without the prior permission of the owner. Still, interviews were performed on 68.8% of all existent businesses in the analysed streets with an unbiased distribution (48–51) between old (already existent before the rehabilitation of the market) and new businesses (not existent in 2007), respectively.

Regarding the new businesses, it is clear that their opening was not influenced by the intervention performed in the market. Only one respondent admitted that the existence of the rehabilitated market was taken in consideration in the decision making as to the location of its store. Regarding the benefits they obtain for being located close to the market, 15 business owners assume some gains, all of which related to the increase of vitality provoked by the market, generating some flow of passers-by that occasionally make some purchases in the establishments that are located in the route between the stop of tram 28 and the market. The majority of respondents answered that they do not obtain any kind of positive outcomes for being located in close proximity to Campo de Ourique market. Although sixteen respondents were unable to justify this answer, the remaining provided answers that fit in four major categories. The first relates to the fact that clients of the respective establishments are customers who go to the store on purpose and are not the potential passers-by. Thus, the increase of passers-by circulating in the vicinity is not relevant to the volume of sales. Secondly, it was stated that new clients of the market do not interact with the surrounding retail fabric. Third, Campo de Ourique market mainly attracts a high volume of people late in the afternoon or at night, in which most establishments are already closed. Finally, the majority of their clients are residents in the area, thus, the presence of the market and positive effects it may provoke regarding the vitality of the area (as a consequence of visitors from outside Campo de Ourique) do not contribute to the viability of those stores.

Regarding the answers obtained from entrepreneurs, whose retail stores were already operating in 2007, the majority (26 out of 48) stated that Campo de Ourique is not an inert structure, insofar as it produces both positive and/or negative impacts. However, only ten business owners assumed to benefit from the rehabilitation of that retail precinct. On the positive side, the increase of vitality was mentioned, by means of the people who came to attend the area because of the market. Nonetheless, of the 21 answers that stated this impact, 11 also said that the increase of passers-by was not followed by an increase of sales and turnover. On the negative side, it was stated that there was an overall increase of the price of the products sold by traditional retailers in the market. As in almost every dense urban space, parking is a key issue. The increase of clients that attend the market, not necessarily tourists but mainly the ones that are residents in the Lisbon region, added some more pressure on the parking availability. This is further reinforced because the entrance to the main underground parking space is located just a few meters from the market. Another mentioned aspect is the competition that new stores located in the market, mainly restaurants and bars, place on the existent retail fabric of the area.

5. Conclusions

Likewise in several other traditional retail markets in a growing array of countries, the one located in the neighbourhood of Campo de Ourique in Lisbon has become gentrified. The path to this current condition was very similar to the one that occurred in other markets as testified by the existent literature on retail gentrification. It starts with the divestment of local authorities, consequent decline of the retail precinct, and introduction of this decline into public discourse in order to favour and legitimise the privatisation of all or part of the retail precinct, which eventually culminates in deep transformations in the tenant mix and in the clients they intend to cater. Starting from this assumption and having Campo de Ourique market as a case study, in this article we aimed to study the relationship between this retail precinct and the commercial fabric in its surroundings.

To answer our initial research question “What is the relationship between gentrified Campo de Ourique traditional retail market and the commercial fabric of the respective neighbourhood?” our empirical study involved fieldwork developed in person by the author in ten streets chosen in accordance with literature review, namely the study of Lowe (2005a). The functional survey unveiled that a significant number of stores that were operating in 2007 were closed in 2018 but new businesses appeared since. Overall, observed changes in the tenant mix may be seen as readjustments of the area to, as a whole, maintain itself as a vital and viable centre of commerce. According to information retrieved from interviews, almost all new business did not open in the area due to that retail precinct, which allows us to conclude there is no increase in the attractiveness of the area for the opening of new businesses as a result of the existence of the rehabilitated market. With regard to the benefits that local commercial fabric derives from the rehabilitated market, only one quarter of respondents assumed to benefit from that intervention. The gains arise from the increase of passers-by that visit the area due to the market and eventually do some shopping in local stores. However, for the large majority of retailers, the existence of Campo de Ourique market does not benefit them in any way and some even call into question some negative outcomes. In the first case, the market is regarded with indifference, assuming there is a disconnection between the market and the commercial fabric of the neighbourhood. Some of the features described in Table 2 fit in this description of the market and are in line with Christopherson’s (1994) discussion of the fortress character that better describe some urban designs. Still, this finding shows that this kind of intervention is not aligned with the underlying logic of retail-led urban regeneration projects because of its not so clear connection with the commercial fabric of the urban district where it is located.

The traditional retail market is a public space in its origin and also possesses a public interest in what concerns the supply of the most disadvantaged fringes of the population, therefore means that main original key features are being discarded in detriment of a mere capitalist exploitation of the retail precinct seen as a place of leisure and consumption. Some other responses point to negative impacts of the market as it is. In this case, indirect consequences of the increase of vitality were mentioned, due to the rising demand for parking in a high-density residential neighbourhood, which has undermined the quality of life for residents by increasing the parking occupancy rate that, before the rehabilitation of the market, was already an obvious problem in the neighbourhood. Additionally, respondents stated that old retailers operating in the market have readjusted their products and increased the price of the products, thus favouring new clients and neglecting old ones. As one may find in several tourism destinations, products such as fruit are now sold already peeled and presented in small packages, ready to be consumed. This is in line with information from 2014, short after the rehabilitation of the market, according to which “old retailers are adapting, renewing their products” (Costa 2014 (author translation)), being expected that this process has deepened since then. In its essence, the rehabilitation of this traditional retail market was based on an idea of a retail precinct closed in itself, without any relation with the retail fabric of the surrounding area. Thus, the produced impacts are extremely narrow. Although it might improve the overall image of the area as a commercial destination, the people that visit the market do not consume in other stores rather than the ones located in the market.

The information presented in this article should also raise some questions as to the quality of life of residents. The adjustment performed by retailers operating in Campo de Ourique market clearly favours leisure-oriented clients and not long-term residents who search for products on a daily or somehow regular base and may not be willing or be able to purchase these products at higher prices. This is because the products sold in the market are no longer sold as daily purchase products and have become part of an entertainment package for tourists looking for some local experience, getting the rewarding feeling of buying something authentic, placing themselves in the role of local residents. In the future, the quality of life of local residents may suffer new and pronounced pressures. As for now, no evidence was found that the commercial fabric of Campo de Ourique neighbourhood has adjusted the products they sell to these higher-income visitors, keeping residents and those who go on purpose to their establishments as their main clients. However, because retail is a particularly fragile and volatile sector, the current situation does not mean that this will not happen in the near future, which will put even more pressure on traditional clients who may have difficulty or be unable to supply elsewhere. In terms of policy implications, this strategy of privatisation of this type of retail precincts was revealed to be twofold. On one side, increased overall attractiveness of the traditional retail market, visible in the attraction of new clients and in the opening of new businesses. However, on the other side, one should question the beneficiaries of the transformation, because private developers will only aim to capitalize the traditional retail market to the maximum, instead of trying to provide a diverse offer of retail products at different prices that may allow the supply needs of the population to be met in its diversity, wealthier, middle-class or disadvantaged consumers, a function of public interest that these retail precincts should be able to offer. The findings of this article add novel knowledge to existent literature on retail gentrification, mostly focused on the analysis on the wider gentrification of shopping districts. It also adds to literature on retail-led urban regeneration and is of interest for practitioners, as it was not proved that the rehabilitation and gentrification of a certain retail precinct provokes positive effects in the attractiveness of the surrounding commercial fabric.

As a final remark, one may claim for more studies focused on the analysis of the multiplier effects that gentrified precincts may introduce in the respective urban districts.

Funding

Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia: Project “PHOENIX—Retail-Led Urban Regeneration and the New Forms of Governance”—PTDC/GES-URB/31878/2017.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Atkinson, Rowland. 2000. Measuring Gentrification and Displacement in Greater London. Urban Studies 37: 149–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barata-Salgueiro, Teresa. 2017. Impactos de la gentrificación y el turismo urbano en el comercio minorista. In Ciudad, comercio urbano y consumo. Edited by José Zamora and Patricia Martínez. México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, pp. 361–82. [Google Scholar]

- Barata-Salgueiro, Teresa, and Herculano Cachinho. 2009. As relações cidade-comércio, dinâmicas de evolução e modelos interpretativos. In Cidade e comércio, a rua comercial na perspectiva internacional. Edited by Carles Carreras and Susana Pacheco. Rio de Janeiro: Armazéns das Letras, pp. 9–39. [Google Scholar]

- Barata-Salgueiro, Teresa, Luís Mendes, and Pedro Guimarães. 2017. Tourism and urban changes: Lessons from Lisbon. In Tourism and Gentrification in Contemporary Metropolises: International Perspectives. Edited by Maria Gravary-Barbas and Sandra Guinand. London: Routledge, pp. 255–75. [Google Scholar]

- Bearne, Suzanne. 2017. Istanbul: Former Tourist Hotspot Is Ghost Town for Small Businesses. The Guardian. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/small-business-network/2017/feb/09/istanbul-former-tourist-hotspot-ghost-town-small-businesses (accessed on 20 May 2019).

- Bounds, Michael, and Alan Morris. 2006. Second wave gentrification in inner-city Sydney. Cities 23: 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cachinho, Herculano. 2014. Consumerscapes and the resilience assessment of urban retail systems. Cities 36: 131–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Câmara Municipal de Lisboa. 2016. Plano municipal dos mercados de Lisboa 2016–2020. Lisboa: Câmara Municipal de Lisboa. [Google Scholar]

- Christopherson, Susan. 1994. The Fortress City: Privatized Spaces, Consumer Citizenship. In Post-Fordism—A Reader. Edited by Ash Amin. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, pp. 409–27. [Google Scholar]

- Cocola-Gant, Agustin. 2018. Tourism gentrification. In Handbook of Gentrification Studies. Edited by Loretta Lees and Martin Phillips. Cheltenham and Northampton: Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 281–93. [Google Scholar]

- Cordero, Adrián. 2017. Los mercados públicos: Viejos equipamientos, nuevos usos y disputas por la ciudad. Reflexiones a partir de Barcelona. In Ciudad, comercio urbano y consumo. Edited by José Zamora and Patricia Martínez. México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, pp. 397–412. [Google Scholar]

- Cordero, Adrián, and Stoyanka Eneva. 2017. Disputa por los mercados públicos abandonados. Ciudades 114: 25–31. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, Joana. 2014. Revolução em Campo de Ourique, Jornal Sol. Available online: https://sol.sapo.pt/artigo/96673/revolucao-em-campo-de-ourique (accessed on 20 May 2019).

- Davis, Kingsley. 2005. The Urbanization of the Human Population. In The City Reader, 5th ed. Edited by Richard Legates and Frederic Stout. Oxon: Routledge, pp. 20–30. [Google Scholar]

- Delgadillo, Victor. 2017. Patrimonialización de los mercados. Ciudades 114: 2–9. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, Lei, Jackelyn Hwang, and Eileen Divringi. 2016. Gentrification and residential mobility in Philadelphia. Regional Science and Urban Economics 61: 38–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frago, Lluís. 2017. Gentrificación y consumo: El papel de los mercados municipales. In Espacios del consumo y el comercio en la ciudad contemporánea. Edited by José Zamora. México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, pp. 137–56. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, Lance, and Frank Braconi. 2004. Gentrification and Displacement New York City in the 1990s. Journal of the American Planning Association 70: 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasson, John, and Graham Wood. 2009. Urban regeneration and impact assessment for social sustainability. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal 27: 283–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, Carmen, and Daniel Nicolas. 2017. Mercados queretanos: Entre tradición y modernidade. Ciudades 114: 17–24. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez, Sara, ed. 2018. Contested Markets, Contested Cities. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez, Sara, and Gloria Dawson. 2018. Resisting gentrification in traditional public markets: Lessons from London. In Contested Markets, Contested Cities—Gentrification and Urban Justice in Retail Spaces. Edited by Sara Gonzalez. Oxon: Routledge, pp. 54–71. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez, Sara, and Paul Waley. 2013. Traditional retail markets: The new gentrification frontier? Antipode 45: 965–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotham, Kevin. 2005. Tourism Gentrification: The case of New Orleans’ Vieux carre (French Quarter). Urban Studies 42: 1099–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravari-Barbas, Maria, and Sandra Guinand, eds. 2017. Tourism and Gentrification in Contemporary Metropolises—International Perspective. Devon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Guimarães, Pedro. 2017. An evaluation of urban regeneration: The effectiveness of a retail-led project in Lisbon. Urban Research & Practice 10: 350–66. [Google Scholar]

- Guimarães, Pedro. 2018. The Transformation of Retail Markets in Lisbon: An Analysis through the Lens of Retail Gentrification. European Planning Studies 26: 1450–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, Pedro. 2019. Shopping centres in decline: Analysis of demalling in Lisbon. Cities 87: 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, Pedro, Filipe Matos, and Teresa Barata-Salgueiro. 2011. Os comerciantes como actores da resiliência das áreas comerciais. In Retail Planning for the Resilient City. Edited by Teresa Barata-Salgueiro and Herculano Cachinho. Lisbon: Centro de Estudos Geográficos, pp. 105–24. [Google Scholar]

- Guzey, Ozlem. 2009. Urban regeneration and increased competitive power: Ankara in an era of globalization. Cities 26: 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gvion, Liora. 2017. Space, gentrification and traditional open-air markets: How do vendors in the Carmel market in Tel Aviv interpret changes? Community Work & Family 20: 346–65. [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard, Phil. 2017. The Battle for the High Street. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Jayne, Mark. 2006. Cities and Consumption. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kitchin, Rob, and Nicholas Tate. 2000. Conducting Research into Human Geography, Theory, Methodology and Practice. Essex: Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Lamas, José. 2004. Morfologia urbana e desenho da cidade, 3rd ed. Porto: Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Jae. 2013. Mega-Retail-Led Regeneration and Housing Price. disP The Planning Review 49: 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Heeji, Jeeyeop Kim, Cuz Potter, and Woongkyoo Bae. 2013. Urban regeneration and gentrification: Land use impacts of the Cheonggye Stream Restoration Project on the Seoul’s central business district. Habitat International 39: 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, Michelle. 2005a. Revitalizing inner city retail?: The impact of the West Quay development on Southampton. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management 33: 658–68. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe, Michelle. 2005b. The Regional Shopping Centre in the Inner City: A study of Retail-led Urban Regeneration. Urban Studies 42: 449–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, Michelle. 2007. Rethinking Southampton and town centre futures. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management 35: 639–46. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez, Plácido. 2016. Authenticity as a challenge in the transformation of Beijing’s urban heritage: The commercial gentrification of the Guozijian historic area. Cities 59: 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateos, Elvira. 2017. Transformación del comercio de proximidad: Legitimidad y disputas. Ciudades 114: 10–16. [Google Scholar]

- Mclafferty, Sara. 2005. Conducting Questionnaire Survey. In Key Methods in Geography, 3rd ed. Edited by Nicholas Clifford and Gill Valentine. London, Thousand Oaks and New Delhi: Sage Publications, pp. 87–100. [Google Scholar]

- Meltzer, Rachel, and Pooya Ghorbani. 2017. Does gentrification increase employment opportunities in low-income neighborhoods? Regional Science and Urban Economics 66: 52–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, Luís. 2018. Gentrificação turística em Lisboa: Impactos do alojamento local na resiliência e sustentabilidade social do centro histórico. Poder Local Revista de Administração Democrática 155: 58–73. [Google Scholar]

- Mermet, Anne-Cécile. 2017. Global retail capital and the city: Towards an intensification of gentrification. Urban Geography 38: 1158–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumford, Lewis. 2005. What is a City? In The City Reader, 5th ed. Edited by Richard Legates and Frederic Stout. Oxon: Routledge, pp. 91–95. [Google Scholar]

- Observatório de Lisboa. 2015. Hóspedes e dormidas—Lisboa cidade. Lisboa: Observatório do Turismo de Lisboa. [Google Scholar]

- Ozdemir, Dilek, and Irem Selçuk. 2017. From pedestrianisation to commercial gentrification: The case of Kadıköy in Istanbul. Cities 65: 10–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacione, Michael. 2005. Urban Geography, a Global Perspective, 2nd ed. Oxon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Pavel, Fabiana. 2015. Transformação urbana de uma área histórica: O Bairro Alto. Reabilitação, Identidade e Gentrificação. Ph.D. dissertation, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisbon, Portugal. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, Cláudio. 2017. Mercados públicos minucipales: Espacios de resistencia al neoliberalismo urbano. Ciudades 114: 39–46. [Google Scholar]

- Reyes-Menedez, Ana, José Saura, and Pedro Palos-Sanchéz. 2018. Crowdfunding y financiación 2.0. Un estudio exploratorio sobre el turismo cultural. International Journal of Information Systems and Tourism (IJIST) 3: 23–34. [Google Scholar]

- Rosa, Paula. 2017. Ferias y Mercados en una ciudad en transformación. Ciudades 114: 32–38. [Google Scholar]

- Schappo, Patrícia, and Rianne Melik. 2017. Meeting on the marketplace: On the integrative potential of The Hague Market. Journal of Urbanism 10: 318–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, Tom, Winifred Curran, and Loretta Lees. 2004. Guest Editorial. Environment and Planning A 36: 1141–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Neil. 1987. Gentrification and the Rent Gap. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 77: 462–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tallon, Andrew. 2008. Mega-Retail-Led Regeneration. Town and Country Planning 77: 131–37. [Google Scholar]

- Tight, Malcolm. 2017. Understanding Case Study Research. Croydon: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Tsang, Eric. 2013. Case study methodology: Causal explanation, contextualization, and theorizing. Journal of International Management 19: 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, Heliana. 2017. Mercados del siglo XIX: Génesis y permanência. Ciudades 114: 55–63. [Google Scholar]

- Whysall, Paul. 1995. Regenerating inner city shopping centres—The British experience. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 2: 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zukin, Sharon. 2008. Consuming Authenticity. Cultural Studies 22: 724–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zukin, Sharon. 2011. Reconstructing the authenticity of place. Theory and Society 40: 161–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zukin, Sharon, Valerie Trulillo, Peter Frase, Danielle Jackson, Tim Recuber, and Abraham Walker. 2009. New retail capital and neighborhood change: Boutiques and gentrification in New York city. City and Community 8: 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).