Resilience as a Public Object. A Longitudinal Press Analysis of the Press Representations of Resilience in Italy, Spain, and France

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. The Notion of Resilience

1.2. Resilience as a Public Object: EU Directives and Guidelines

1.3. Study Rationale and Context

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Dataset

2.2. Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Themes: Cluster Description

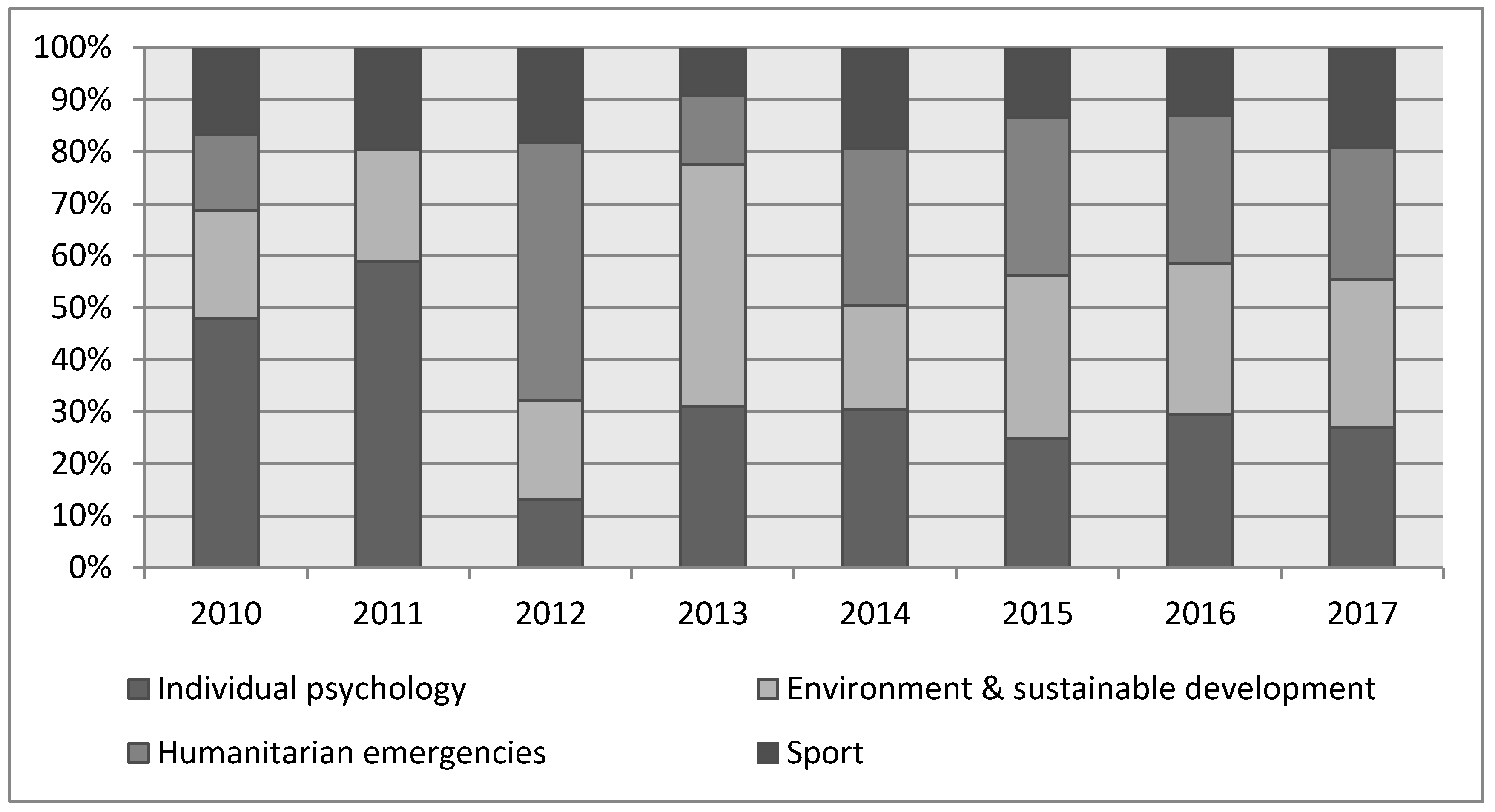

3.1.1. El Pais

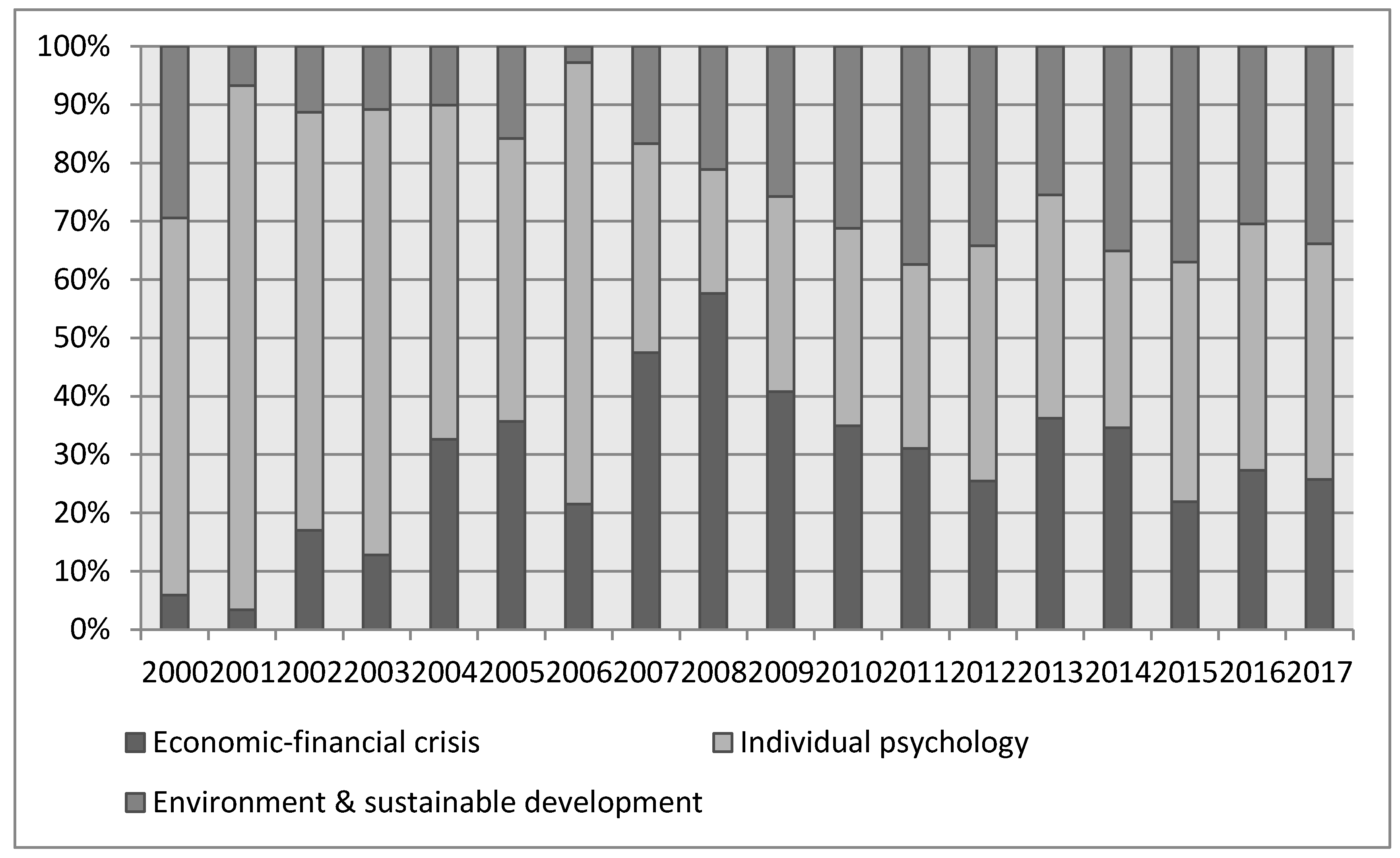

3.1.2. Le Monde

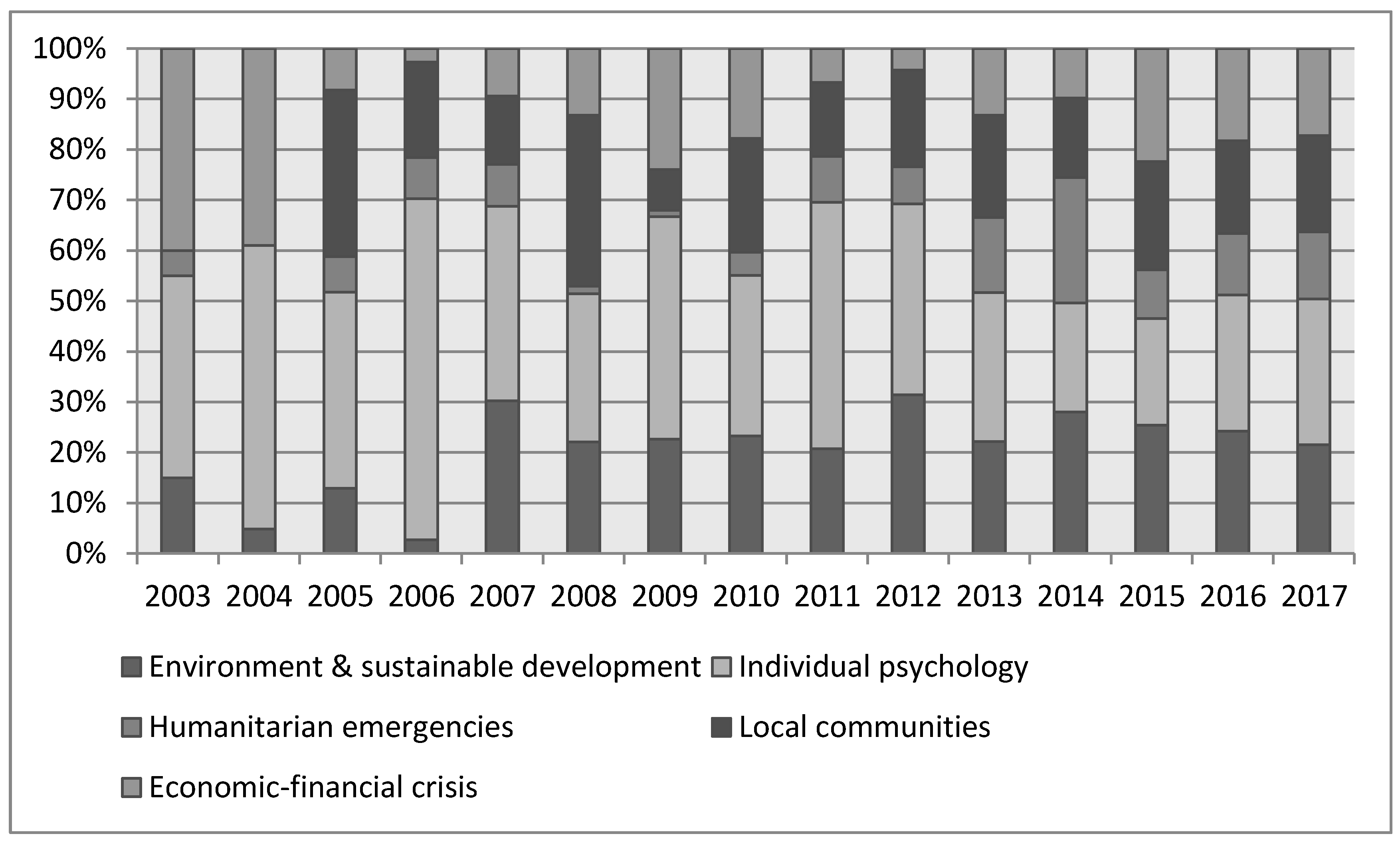

3.1.3. La Repubblica

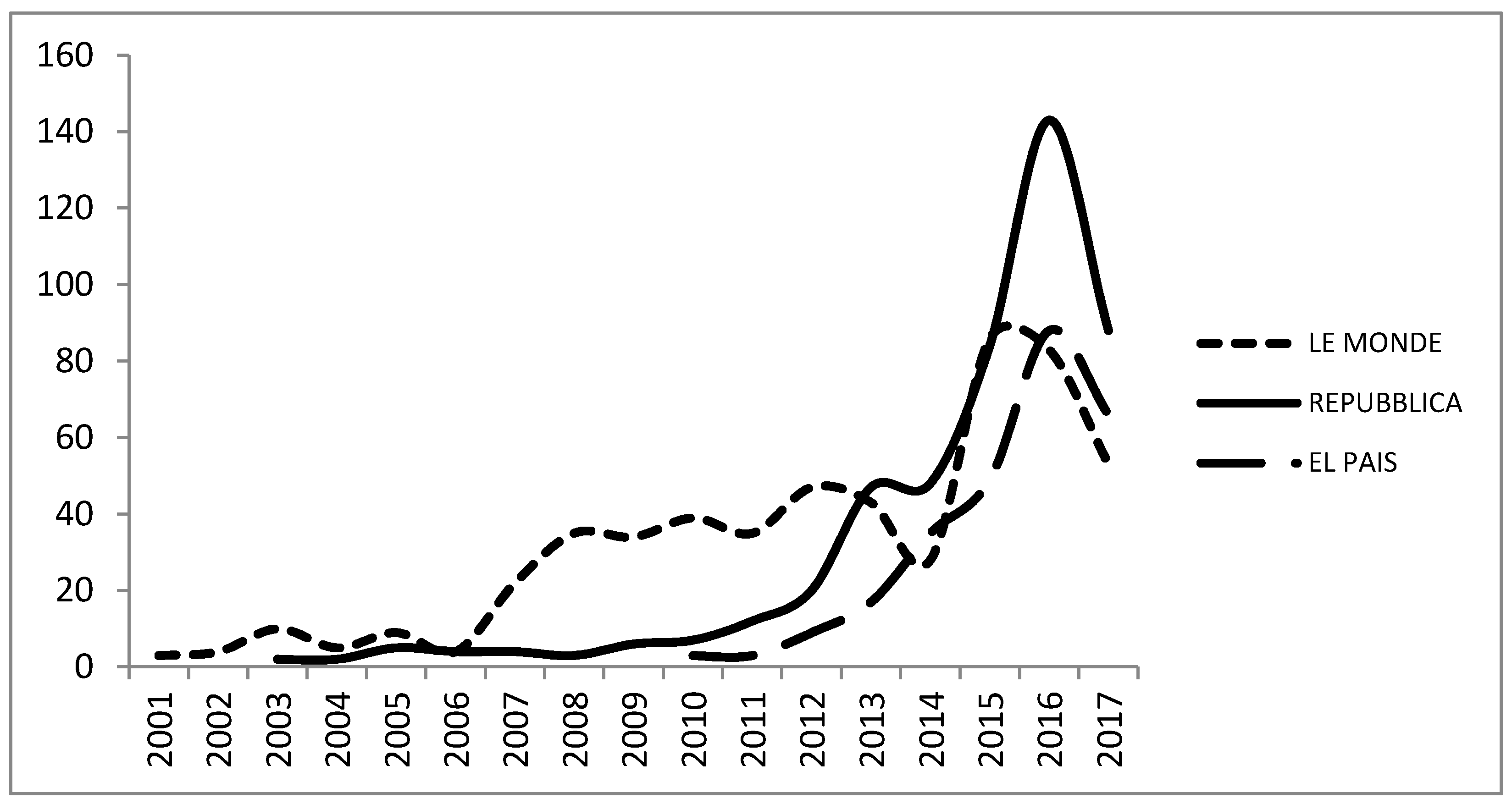

3.2. Distribution of Themes in Time

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adger, Wilkinson N. 2000. Social and ecological resilience: Are they related? Progress in Human Geography 24: 347–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artero, Juan P. 2015. Political Parallelism and Media Coalitions in Western Europe—Working Paper. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, University of Oxford, pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Baggio, Jacopo A., Katrina Brown, and Denis Hellebrandt. 2015. Boundary object or bridging object? A citation network analysis of resilience. Ecology and Society 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, Martin W. 2005. Public perceptions and mass media in the biotechnology controversy. International Journal of Public Opinion Research 17: 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, Martin W., and George Gaskell. 2002. Researching the public sphere of biotechnology. In Biotechnology—The Making of a Global Controversy. Edited by Martin W. Bauer and George Gaskell. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, Martin W., and George Gaskell. 2008. Social representations theory: A progressive research programme for social psychology. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour 38: 335–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentivegna, Sara, and Rita Marchetti. 2019. News Users on Facebook: Interaction Strategies on the Pages of El Paìs, la Repubblica, Le Monde, and The Guardian. Journalism Studies, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Katrina. 2016. Resilience, Development and Global Change. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Buikstra, Elizabeth, Helen C. Ross, Christine A. King, Peter G. Baker, Desley Hegney, Kathryn Mclachlan, and Cath Rogers-Clark. 2010. The components of resilience: Perceptions of an Australian rural community. Journal of Community Psychology 38: 975–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capano, Gilberto, and Jun J. Woo. 2017. Resilience and robustness in policy design: A critical appraisal. Policy Sciences 50: 399–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, Steve R., Brian H. Walker, John M. Anderies, and Nick Abel. 2001. From Metaphor to Measurement: Resilience of What to What? Ecosystems 4: 765–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, Paula, and Isabel Gomes. 2005. Genetically Modified Organisms in the Portuguese Press: thematization and anchoring. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour 35: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christidou, Vasilia, Kostas Dimopoulos, and Vasilis Koulaidis. 2004. Constructing social representations of science and technology: the role of metaphors in the press and the popular scientific magazines. Public Understanding of Science 13: 347–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Community and Regional Resilience Institute. 2013. Definitions of Community Resilience: An Analysis. Washington, DC: Community and Regional Resilience Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Davoudi, Simin, Keith Shaw, Jamilia L. Haider, Allison E. Quinlan, Garry D. Peterson, and Cathy Wilkin. 2012. Resilience: A Bridging Concept or a Dead End? Planning Theory and Practice 13: 299–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duit, Andreas, Victor Galaz, Katarina Eckerberg, and Jonas Ebbesson. 2010. Governance, complexity, and resilience. Global Environmental Change 20: 363–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folke, Carl. 2006. Resilience: The emergence of a perspective for social-ecological systems analyses. Global Environmental Change 16: 253–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folke, Carl, Stephen R. Carpenter, Brian Walker, Marten Scheffer, Terry Chapin, and Johan Rockström. 2010. Resilience thinking: Integrating resilience, adaptability and transformability. Ecology and Society 15: 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folke, Carl, Reinette Biggs, Albert V. Norström, Belinda Reyers, and Johan Rockström. 2016. Social-ecological resilience and biosphere-based sustainability science. Ecology and Society 21: 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garmezy, Norman. 1974. The study of competence in children at risk for severe psychopathology. In The Child in His Family: Children at Psychiatric Risk: III. Edited by E. James Anthony and Cyrille Koupernik. New York: Wiley, pp. 77–97. [Google Scholar]

- Gauthier, Elisabeth. 2010. Social Representations of Risk in the Food Irradiation Debate in Canada, 1986–2002. Science Communication 32: 295–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunderson, Lance H., and Crawford S. Holling. 2002. Panarchy: Understanding Transformations in Human and Natural Systems. Washington, DC: Island Press. [Google Scholar]

- Holling, Crawford S. 1973. Resilience and stability of ecological systems. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 4: 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, Howard B. 1999. Toward an Understanding of Resilience: A Critical Review of Definitions and Models. In Resilience and Development. Edited by Meyer D. Glantz and Jeanette L. Johnson. New York: Kluwer Academic, pp. 17–83. [Google Scholar]

- Keck, Markus, and Patrick Sakdapolrak. 2012. What is social resilience? Lessons learned and ways forward. Erdunke 67: 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendra, James M., and Tricia Wachtendorf. 2003. Elements of Resilience after the World Trade Center Disaster: Reconstituting New York City’s Emergency Operations Centre. Disasters 27: 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labra, Oscar. 2015. Social representations of HIV/AIDS in mass media: Some important lessons for caregivers. International Social Work 58: 238–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahlou, Saadi, and Jean-Claude Abric. 2011. What are the “elements” of a representation? Papers on Social Representations 20: 20.1–20.10. [Google Scholar]

- Lancia, Franco. 2004. Strumenti per l’Analisi dei Testi. Introduzione all’uso di T-LAB [Tools for text analysis. An introduction to T-lab]. Milano: Franco Angeli. [Google Scholar]

- Lauri, Mary Anne. 2009. Metaphors of organ donation, social representations of the body and the opt-out system. British Journal of Health Psychology 14: 647–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luthar, Suniya S., and Dante Cicchetti. 2000. The construct of resilience: Implications for interventions and social policies. Development and Psychopathology 12: 857–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthar, Suniya S., Dante Cicchetti, and Bronwyn Becker. 2000. The Construct of Resilience: A Critical Evaluation and Guidelines for Future Work. Child Development 71: 543–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manyena, Siambabala B. 2006. The concept of resilience revisited. Disaster 30: 433–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masten, Anne S. 2001. Ordinary Magic. Resilience Process in Development. American Psychologist 56: 227–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masten, Anne S., and Jelena Obradović. 2006. Competence and Resilience in Development. Annual New York Academy of Sciences 1021: 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matarrita-Cascante, David, Bernando Trejos, Hua Qin, Dongoh Joo, and Sigrid Debner. 2016. Conceptualizing community resilience: Revisiting conceptual distinctions. Community Development 48: 105–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscovici, Serge. 1981. On social representations. Perspectives on everyday understanding. In Social Cognition. Edited by Joseph P. Forgas. London: Academic Press, pp. 181–209. [Google Scholar]

- Norris, Fran H., Susan P. Stevens, Betty Pfefferbaum, Karen F. Wyche, and Rose L. Pfefferbaum. 2008. Community Resilience as a Metaphor, Theory, Set of Capacities, and Strategy for Disaster Readiness. American Journal of Community Psychology 41: 127–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfefferbaum, Rose L., Betty Pfefferbaum, Richard L. Van Horn, Richard Klomp, Fran H. Norris, and Dori Reissman. 2013. The Communities Advancing Resilience Toolkit (CART): An Intervention to Build Community Resilience to Disasters. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice 19: 250–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, Adam. 2007. Economic resilience to natural and man-made disasters: Multidisciplinary origins and contextual dimensions. Environmental Hazards 7: 383–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgado, Susan, and Heinz-Werner Nienstedt. 2016. Euro Crisis and plurality: Does the political orientation of newspapers determine the selection and spin of information? European Journal of Communication 31: 462–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonn, Christopher C., and Adrian T. Fisher. 1998. Sense of community: Community resilient responses to oppression and change. Journal of Community Psychology 26: 457–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzelgun, Mehmet A., and Paula Castro. 2015. Climate Change in the Mainstream Turkish Press: Coverage Trends and Meaning Dimensions in the First Attention Cycle. Mass Communication and Society 18: 730–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaneeckhaute, Lieselotte E., Tom Vanwing, Wolfgang Jacquet, Bieke Abelshausen, and Pieter Meurs. 2017. Community resilience 2.0: Toward a comprehensive conception of community-level resilience. Community Development. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veltri, Giuseppe A. 2012. Viva la Nano-Revolución! A Semantic Analysis of the Spanish National Press. Science Communication 35: 143–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, Froma. 2003. Family Resilience: A Framework for Clinical Practice. Family Process 42: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, Geoff A. 2012. Community resilience, globalization, and transitional pathways of decision-making. Geoforum 43: 1218–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cluster 1 27.5% of ECUs | Cluster 2 28.35% of ECUs | Cluster 3 15.44% of ECUs | Cluster 4 28.71% of ECUs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lemmas | Chi-Square | Lemmas | Chi-Square | Lemmas | Chi-Square | Lemmas | Chi-Square |

| Niño | 427,901 | Climático | 523,766 | Ciudad | 622,937 | Equipo | 255,118 |

| [child] | [climatic] | [city] | [team] | ||||

| Vida | 421,908 | Cambio | 469,267 | Millones | 397,662 | Madrid | 251,511 |

| [life] | [change] | [millions] | [Madrid] | ||||

| Mujer | 165,868 | Empresa | 223.25 | Urbano | 372,354 | Minuto | 235,508 |

| [woman] | [company] | [urban] | [minute] | ||||

| Persona | 161,013 | Economía | 212.9 | Población | 224,213 | Final | 232,344 |

| [person] | [economy] | [population] | [final] | ||||

| Felicidad | 150,296 | Sector | 210,922 | Humanitaria | 176,111 | Laso | 196,726 |

| [happiness] | [sector] | [humanitarian] | [Laso] | ||||

| Vivir | 135,147 | Emisión | 170,768 | Unido | 172,561 | Jugador | 161,387 |

| [to live] | [emission] | [united] | [player] | ||||

| Positivo | 131,683 | Banco | 148,986 | Mundial | 143,327 | Partir | 149,594 |

| [positive] | [banck] | [world adj.] | [to split] | ||||

| Padres | 131,023 | Acuerdo | 138,979 | Alimentaria | 131,156 | Llegar | 140,315 |

| [fathers] | [agreement] | [food adj.] | [to arrive] | ||||

| Psicólogo | 129,913 | París | 127,391 | Nación | 113.35 | Escribir | 129,429 |

| [psychologist] | [Paris] | [nation] | [to write] | ||||

| Emocional | 116,696 | Global | 122,915 | Alimento | 110,627 | Libro | 123,101 |

| [emotional] | [global] | [food] | [book] | ||||

| Aprender | 115,516 | Mercado | 119,094 | Zona | 101,495 | Asenjo | 120,558 |

| [to learn] | [market] | [zone] | [Asenjo] | ||||

| Estudio | 114,579 | Empleo | 112,748 | Habitante | 94,423 | Título | 114,234 |

| [study] | [job] | [inhabitant] | [title] | ||||

| Cerebro | 114.19 | España | 104.93 | Sostenible | 93,364 | Villarreal | 114,211 |

| [brain] | [Spain] | [sustainable] | [Villareal] | ||||

| Familia | 107.63 | Financiero | 102,777 | África | 91,258 | Portero | 106,315 |

| [family] | [financial] | [Africa] | [goalie] | ||||

| Emociones | 104,553 | Carbono | 98.84 | Espacio | 89,326 | Día | 104,704 |

| [emotions] | [coal] | [space] | [day] | ||||

| Cluster 1 29.81% of ECUs | Cluster 2 31.28% of ECUs | Cluster 3 38.91% of ECUs | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lemmas | Chi-Square | Lemmas | Chi-Square | Lemmas | Chi-Square |

| Américain | 607,267 | Enfant | 568,977 | Climatique | 639,615 |

| [American] | [child] | [climatic] | |||

| Européen | 524,312 | Vie | 550,071 | Développement | 536,704 |

| [European] | [life] | [development] | |||

| Crise | 514,732 | Mourir | 536,287 | Entreprise | 477,699 |

| [crisis] | [to die] | [company] | |||

| Politique | 497,395 | Mort | 403,665 | Entreprendre | 471,499 |

| [political] | [death] | [to undertake] | |||

| Etats-Unis | 342,724 | Vivre | 283,704 | Changement | 417,958 |

| [US] | [to live] | [change] | |||

| Financier | 251,375 | Femme | 246,023 | Afrique | 316,849 |

| [financial expert] | [woman] | [Africa] | |||

| État | 231,674 | Attentat | 229,555 | Milliard | 274,256 |

| [state] | [attack] | [billion] | |||

| Président | 216,567 | Famille | 224,042 | Niveau | 210.56 |

| [president] | [family] | [level] | |||

| Économie | 208,012 | Jeune | 223,779 | Million | 205,731 |

| [economy] | [young] | [million] | |||

| Russie | 205,188 | Homme | 222,737 | Mondial | 181,403 |

| [Russia] | [man] | [world adj.] | |||

| Monétaire | 186,264 | Histoire | 200,423 | Investissement | 175,717 |

| [mnetary] | [history] | [investment] | |||

| Militaire | 179,594 | Image | 196.77 | Secteur | 175.7 |

| [military] | [image] | [sector] | |||

| Banque | 178,103 | Mère | 187,421 | Système | 173,066 |

| [bank] | [mother] | [system] | |||

| Défense | 170,465 | Victime | 171,208 | Agriculture | 171,007 |

| [defence] | [victim] | [agriculture] | |||

| Chef | 165,789 | Scène | 161,598 | Climat | 167,865 |

| [chief] | [scene] | [climate] | |||

| Cluster 1 12.63% of ECUs | Cluster 2 23.92% of ECUs | Cluster 3 18.95% of ECUs | Cluster 4 16.38% of ECUs | CLUSTER 5 8.13% of ECUs | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lemmas | Chi-square | Lemmas | Chi-Square | Lemmas | Chi-Square | Lemmas | Chi-Square | Lemmas | Chi-Square |

| Cambiamento | 239,514 | Vita | 390,852 | Milioni | 1,108,434 | Città | 488,225 | Banca | 585,784 |

| [change] | [life] | [millions] | [city] | [bank] | |||||

| Settore | 171,805 | Bambino | 313,707 | WFP * | 1,077,526 | Partire | 306,115 | Europeo | 509,016 |

| [sector] | [child] | [WPF] | [to start] | [European] | |||||

| Sviluppo | 164,438 | Ragazzo | 312.65 | Alimentare | 853,659 | Sindaco | 255,083 | Euro | 479,542 |

| [development] | [kid] | [to feed] | [major] | [euro] | |||||

| Ricerca | 163.05 | Morire | 256.274 | Persone | 755,578 | Partito | 226,935 | Miliardo | 442.22 |

| [search] | [to die] | [people] | [party] | [billion] | |||||

| Sfida | 141,012 | Figli | 190,668 | Umanitario | 677,326 | Piazza | 167,844 | Crescita | 305,626 |

| [challenge] | [offspring] | [humanitarian] | [square] | [growth] | |||||

| Imprese | 135,322 | Casa | 160,502 | Assistenza | 625,646 | Teatro | 164,918 | BCE *** | 294,552 |

| [companies] | [home] | [aid] | [theater] | [BCE] | |||||

| Economico | 131,137 | Scuola | 159,711 | Sudan | 374,273 | Storia | 127,891 | Ripresa | 260,019 |

| [economic] | [school] | [Sudan] | [history] | [recovery] | |||||

| Sostenibile | 113,346 | Parlare | 159,049 | Emergenza | 334,681 | Scegliere | 117,348 | PIL | 216,486 |

| [sustainable] | [to talk] | [emergency] | [to choose] | [GDP] | |||||

| Nuovo | 110,571 | Morte | 140,748 | FAO ** | 330,667 | Festival | 113,597 | Monetario | 208,004 |

| [new] | [death] | [FAO] | [festival] | [monetary] | |||||

| Sistema | 108,986 | Donna | 139,492 | Cibo | 319,911 | Progetto | 97,737 | Prezzo | 204,566 |

| [system] | [woman] | [food] | [project] | [price] | |||||

| Produrre | 99,005 | Genitore | 138,606 | Popolazione | 313,606 | Assessore | 96,423 | Riprendere | 192,467 |

| [produce] | [parent] | [population] | [local administrator] | [restart] | |||||

| Azienda | 97,483 | Vivere | 131,584 | Fame | 95.37 | Scelta | 96,015 | Europa | 191,149 |

| [firm] | [to live] | [starvation] | [choice] | [Europe] | |||||

| Economia | 91.45 | Giovane | 126,391 | Agenzia | 290,661 | Obama | 86.31 | Tassi | 188,369 |

| [economy] | [young] | [agency] | [Obama] | [rates] | |||||

| Sociale | 90,728 | Sentire | 125,163 | Insicurezza | 289,553 | Napoli | 84,577 | Mercato | 179,459 |

| [social] | [to feel] | [unsafety] | [Naples] | [market] | |||||

| Globale | 88,497 | Padre | 119,166 | Nazioni Unite | 276.47 | PD | 77,256 | Anno | 174,584 |

| [global] | [father] | [United Nations] | [Democratic Party] | [year] | |||||

| Environment & Sustainable Development | Trauma & Individual Psychology | Economic-Financial Crisis | Humanitarian Emergencies | Local Communities | Sport | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| El Pais | λ | λ | λ | λ | ||

| Le Monde | λ | λ | λ | |||

| La Repubblica | λ | λ | λ | λ | λ |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rochira, A.; Mannarini, T.; De Simone, E.; Verbena, S.; Manfreda, A. Resilience as a Public Object. A Longitudinal Press Analysis of the Press Representations of Resilience in Italy, Spain, and France. Soc. Sci. 2019, 8, 189. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8060189

Rochira A, Mannarini T, De Simone E, Verbena S, Manfreda A. Resilience as a Public Object. A Longitudinal Press Analysis of the Press Representations of Resilience in Italy, Spain, and France. Social Sciences. 2019; 8(6):189. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8060189

Chicago/Turabian StyleRochira, Alessia, Terri Mannarini, Evelyn De Simone, Serena Verbena, and Alessandra Manfreda. 2019. "Resilience as a Public Object. A Longitudinal Press Analysis of the Press Representations of Resilience in Italy, Spain, and France" Social Sciences 8, no. 6: 189. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8060189

APA StyleRochira, A., Mannarini, T., De Simone, E., Verbena, S., & Manfreda, A. (2019). Resilience as a Public Object. A Longitudinal Press Analysis of the Press Representations of Resilience in Italy, Spain, and France. Social Sciences, 8(6), 189. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8060189