Abstract

High levels of vulnerability to climate change impacts are rendering some places uninhabitable. In Fiji, four communities have already initiated or completed the task of moving their homes and livelihoods to less exposed locations, with numerous more communities earmarked for future relocation. This paper documents people’s lived experiences in two relocated communities in Fiji—Denimanu and Vunidogoloa villages—and assesses the outcomes of the relocations on those directly affected. This study in particular seeks to identify to what extent livelihoods have been either positively or negatively affected by relocation, and whether these relocations have successfully reduced exposure to climate-related hazards. This study shows that planned climate-induced relocations have the potential to improve the livelihoods of affected communities, yet if these relocations are not managed and undertaken carefully, they can lead to unintended negative impacts, including exposure to other hazards. We find that inclusive community involvement in the planning process, regular and intentional monitoring and evaluation, and improving livelihoods through targeted livelihood planning should be accounted for in future relocations to ensure outcomes are beneficial and sustainable.

Keywords:

relocation; resettlement; livelihoods; Pacific Islands; migration; SIDS; vulnerability; exposure 1. Introduction

Despite high levels of internal resilience, Small Island Developing States (SIDS), as which all Pacific Island Countries (PICs) identify (Barnett and Campbell 2010), have been labelled as some of the most vulnerable places to climate change. This is largely due to a combination of high exposure to climate change impacts as well as a range of underlying social, historical, political, and economic vulnerabilities (Huq and Reid 2007; Jackson et al. 2017; Kelman 2014). Climate change impacts experienced in PICs are predominantly coastal and include rising sea levels, intensification of cyclones resulting in increased storm surge extent, coastal erosion, and changing rainfall patterns (Chand et al. 2016; IPCC 2014b; Keener et al. 2012). Exposure to such climate change impacts is exacerbated by the presence of people, livelihoods, services, and assets in places that can be adversely affected (IPCC 2014a). PICs have high coastline to land mass ratios and primarily coastal settlements (Barnett and Campbell 2010) leading to a significant percentage of the population at higher risk of exposure (Kumar and Taylor 2015). This is further exacerbated by a range of underlying vulnerabilities, such as exposed infrastructure, comparatively low incomes, declining traditional knowledge and practice, historical factors such as colonial legacies, and a dependence on climate-sensitive resources and industries, such as agriculture and fishing (Barnett and Campbell 2010; Connell 2015; Kelman 2014; Nunn 2009). For some communities, this confluence of factors has led to people being unable to sustain their everyday livelihoods in their current locations.

The vulnerability of PICs reveals the deeply inequitable nature of climate change, in that those contributing the least to climate change through their greenhouse gas emissions are also those that are currently most impacted (Althor et al. 2016). For example, SIDS combined contribute less than 1% of the total annual global output of carbon dioxide (Voccia 2011), with PICs contributing less than 0.3% (Weir et al. 2017). Layers of inequality also exist intra-nationally. The peripherality of a community can indicate higher exposure and vulnerability due to distance from core centers and associated resources (McNamara et al. 2017; Nunn and Kumar 2018). Further, certain groups of people within a community are more vulnerable than others (Arora-Jonsson 2011; Dodman and Mitlin 2013; Heltberg et al. 2009). Owing to traditional gender roles in patriarchal contexts, women often have less access than men to information as well as decision making power (George 2010, 2014), as is the case in many rural Pacific Island communities. Accounting for this, all women (as well as other groups within a community) are not equal with individual vulnerability dependent on a range of intersecting factors including class, education, employment, income, and status (Arora-Jonsson 2011). If these factors are not accounted for when planning adaptation responses, they can perpetuate such inequalities (Carr 2008) and subsequently reduce the legitimacy, equity, and sustainability of adaptation.

When adapting to coastal threats such as sea-level rise and associated impacts there are three typologies of adaptation measures employed: Accommodate, protect, and retreat (Williams et al. 2018). It is important to make the distinction between autonomous retreat (or relocation) of communities, as opposed to planned relocation, which usually involves the coordination and management of the process by an external entity. The causes and evolution that have led to the increase in the latter form of relocation are worth briefly exploring. First, it is important to recognise that internal migration within PICs has occurred throughout history and has been a vital aspect of island communities’ livelihoods, resilience, and survival (Barnett and McMichael 2018), with people and entire communities moving in response to changing environmental conditions, as well as in search of improved resources (Campbell 2014). The change towards a less mobile lifestyle, a consequence of colonisation and globalisation, has resulted in communities that have become increasingly permanently attached to place. As such, an inherent adaptation strategy of intentional impermanence common in oceanic island societies has been largely lost (Campbell and Bedford 2014; Gharbaoui and Blocher 2016; Janif et al. 2016).

Planned relocation refers to a “process in which persons or groups of persons move away from their homes or places of temporary residence, are settled in a new location, and provided with the conditions for rebuilding their lives” (UNHCR 2015, p. 9). Of note, within this definition is the explicit mention that relocation should include a focus on providing conditions through which relocated persons can rebuild their livelihoods. This is especially important to consider as research into other forms of resettlement (such as development-induced displacement and resettlement) shows that frequently relocations are unsuccessful in providing successful and holistic outcomes for affected communities because they fail to address such ancillary concerns (Donner 2015; Tadgell et al. 2018). Rather, detrimental outcomes of unemployment, landlessness, homelessness, increased morbidity, loss of access to common property resources, marginalisation, and food insecurity have ensued (Cernea 1997). From this emerges the need to ensure that forethought is built into relocation planning so that such deleterious livelihood outcomes are not replicated.

Communities are already undertaking the process of planned climate-induced relocation in PICs, including in the Solomon Islands (Albert et al. 2018), Papua New Guinea (Connell 2016; Lipset 2013), and Fiji (Barnett and McMichael 2018; Charan et al. 2017; Martin et al. 2018; McMichael et al. 2018). Climate change impacts are projected to be amplified in the future, affecting an increasing range and number of people (IPCC 2014b; Foresight 2011). As a result, it is likely that a greater proportion of people will have to relocate, with some estimates predicting millions may be affected (Ferris 2015), yet the exact numbers are extremely challenging and problematic to predict and quantify (Barnett and O’Neill 2011). The process of planned relocations from climate change has therefore emerged as a critical new field of research and policy debate. Viewing climate-induced relocation as not only an adaptation response, but a form of loss and damage has been argued (McNamara et al. 2018) and is being considered by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) through its work program on loss and damage. An international set of guidelines pertaining to climate-induced relocation was established by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) in conjunction with Georgetown University in 2015 (UNHCR 2015). Ferris (2015) argues the importance of further developing country-level policies and plans that can provide a framework and ensure that relocation facilitates positive outcomes. Fiji has recently released Relocation Guidelines (that were not publicly available at the time of this research) and is the first country in the world to have such a national framework (see Fiji Government 2018), while Vanuatu has recent guidelines on climate change and disaster-induced displacement (IOM 2018).

As climate-induced relocations are likely to increase, the importance of understanding and appropriately managing the process is evident. Within Fiji, four iTaukei (Indigenous) communities have already initiated or completed the relocation of their communities with over 80 further communities recognised by the Fijian Government as in need of future relocation (Barnett and McMichael 2018; Republic of Fiji 2014). Key to reducing the vulnerability of communities to current and anticipated climate change impacts is: Ensuring the process of planned climate change-induced relocation is undertaken in a manner that both reduces the exposure of affected communities to climate change impacts, a key driving force of relocation (Hino et al. 2017); and guaranteeing affected communities have a chance to successfully rebuild their livelihoods in the new location (de Sherbinin et al. 2011). With this context in mind, this research is driven by two key questions:

- (1)

- To what extent have livelihoods been either positively or negatively affected by relocation?

- (2)

- Have relocations reduced exposure to climate-related hazards?

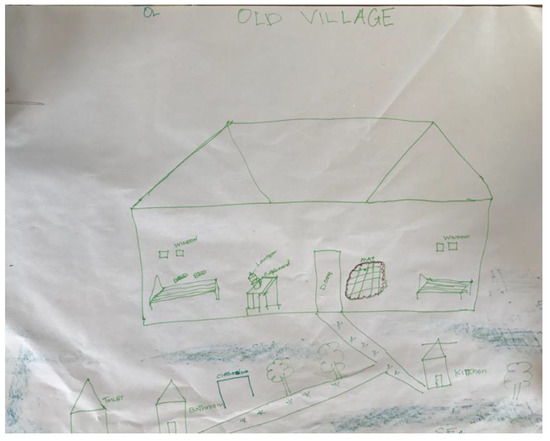

This analysis will be undertaken through an exploration of two recently relocated communities—Vunidogoloa and Denimanu—on Vanua Levu Island, Fiji. This will then provide the context through which to generate insights and lessons that can be applied to future relocation initiatives going forward.

2. Study Sites

Two case study sites are considered in this research, both of which are located on Vanua Levu Island in Fiji. There are 330 islands in Fiji, of which just over 100 are permanently inhabited. The two largest islands, Viti Levu and Vanua Levu, are home to a significant percent of the total population of just over 900,000. Vanua Levu, the second largest island, is where both case study sites in this research are located, although Denimanu is technically offshore. Across Fiji many people live in rural coastal areas, relying on a subsistence lifestyle involving both terrestrial and marine resources. Land in Fiji is an important part of the culture in terms of identity, spirituality, and subsistence (Campbell 2010). Among iTaukei (Indigenous) Fijians, land is codified as mataqali (family land ownership). Almost 90% of land in Fiji is customarily owned (Campbell 2010). For this reason, this also makes relocation a practical issue raising broader questions of land insecurity. Yet, in both case studies for this research, communities were able to move within or across closely-related mataqali lands. Figure 1 shows the location of Fiji in the Pacific Islands region, Vanua Levu island, and the two case study sites.

Figure 1.

Map of Fiji showing the two case study sites (Vunidogoloa and Denimanu villages).

It is noteworthy that these two case studies exhibit the common contrasts within the range of such relocations. First is the portion of the village relocated, with one case study having a complete village relocation and the other a partial village relocation. Second is the impacts that drove the relocation. The first case study describes how relocation was driven by slow-onset climate change impacts while the other study site is an example of sudden-onset impacts, in this case driven by cyclonic storm surge activity. While not uncritically attributable to anthropogenic climate change, the increased strength of cyclonic and storm activity has a level of climate change attribution (Walsh et al. 2016). Both of these planned relocations were supported by the Fiji Government through both its Ministry of Rural and Maritime Development and its National Disaster Management Office.

2.1. Vunidogoloa

Vunidogoloa is located approximately a two-hour bus ride from the nearest town of Savusavu on Vanua Levu Island. It has a population of 153. The people rely heavily on fishing and subsistence agriculture for their livelihoods, as well as cash from market sales of fish and crop surpluses and locally-made crafts. Vunidogoloa has been labeled as the first climate-induced relocation undertaken by the Fiji Government (Charan et al. 2017; Witschge 2018).

Vunidogoloa presents a case of an entire village relocation. The old village was originally situated on the coast. It is important to note that the village had only been in this coastal location for approximately 100 years. Prior to this, they were part of a larger inland village and had relocated to the coast autonomously to be closer to the sea and access its resources (pers. comm. Village Headman 2017). In its former location, the village was increasingly experiencing slow-onset climate impacts including tidal inundation, coastal erosion and saltwater intrusion. This impacted on infrastructure and made growing food crops increasingly difficult. In response, the village was relocated roughly 2 km inland, adjoining the main road (Figure 2). This relocation occurred on land belonging to the same mataqali. The relocation included with it housing, as well as livelihood provisions including fish ponds, pineapple plantations, and cattle. An in-depth recent review of the Vunidogoloa relocation is provided by Charan et al. (2017).

Figure 2.

The new village relocation site of Vunidogoloa.

2.2. Denimanu

Denimanu village is on Yadua Island, situated off the western extremity of Vanua Levu Island. The village is accessible only by boat. Denimanu is the only village today on Yadua Island with a total population of approximately 170 people. It is also worth noting that Denimanu village has previously independently relocated, prior to this planned relocation. The village has moved (at least) twice in search of better food and living conditions. They have been living in their current location for at least 100 years (pers. comm. Village Headman 2017). The village also relies heavily on subsistence fishing and crop agriculture with surplus sold for income.

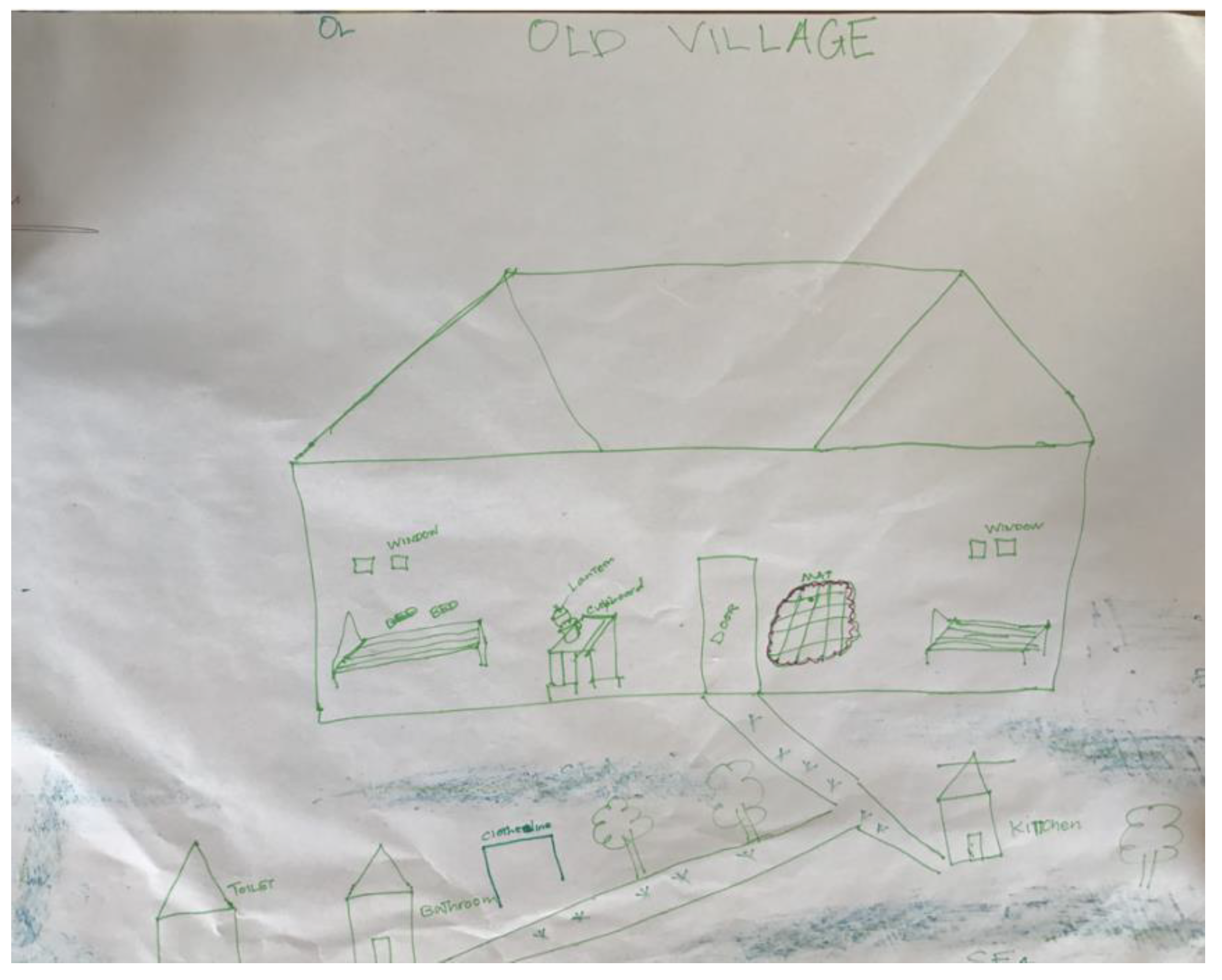

The planned relocation that took place in Denimanu was a partial relocation, with approximately half (19 households) of the village relocated. The houses of the affected people were destroyed by impacts from Cyclone Evan in December 2012. The 19 affected dwellings were located at the front of the village, closest to the coastline. New houses were built approximately 500 m away on a slope of the hill in rows (see Figure 3). The new houses were completed in mid–late 2013. This new location was chosen because the boundaries of the village and the encroaching shoreline made it impossible to rebuild the houses in the location they were previously as the land had been lost. There are two mataqali in Denimanu. A consultation was undertaken between the government and these mataqali to agree on the new location. A more detailed recent review of this relocation is provided by Martin et al. (2018).

Figure 3.

The new village relocation site of Denimanu.

3. Methods

This section will describe the methods undertaken during this field study. This has been broken into sections: Data collection and analysis, ethical procedures, and limitations.

3.1. Data Collection and Anlaysis

Fieldwork was undertaken in both villages in November and December 2017. A local government official acted as a protocol officer and was present throughout the duration of these visits to act as a liaison and entry point to the communities. Both the protocol officer and one of the researchers/authors (a Fijian national) were translators throughout the research.

The method of data collection included focus groups (FGs), interviews and participant observation. Initially two FGs were undertaken in Vunidogoloa (one men’s and one women’s), and three in Denimanu (two women’s groups and one men’s group). As Denimanu was a partial relocation, both groups (those that relocated and those that remain in the original village) were engaged in the research. A second visit to Vunidogoloa was undertaken three weeks after the initial fieldwork where a further two FG discussions were undertaken (one women’s and one men’s). This was done to both gather additional information and clarify findings to date. This resulted in a total of seven FGs involving 54 participants across both sites. The division of FGs by gender allowed both genders to talk freely, an integral aspect of this research. This is especially important in Fiji as women are often excluded from decision-making processes and do not always have opportunities to speak up in group settings (Singh-Peterson and Iranacolaivalu 2018). The FGs involved discussion about the relocation including participants’ experiences and involvement in the process of relocation, and the outcomes since it occurred. Group activities were undertaken that involved participants ranking their perspectives of life before and after relocation across a range of variables. These FGs were recorded, and later transcribed, with detailed notes taken.

Interviews were also undertaken with key members of the community, including leaders, church representatives, and teachers. Interview participants were identified largely from the FGs. From this, the snowball method was used to identify other participants. In this way, discussions with 15 people were undertaken across both sites. Notes were taken during these discussions. Participant observation was an added aspect of the research that gave context to discussions and deepened the research team’s understanding of everyday life in these communities.

The data were analysed through a livelihoods framing, owing to the often-detrimental impact relocating communities can have on the livelihoods of those affected. Livelihoods are understood as the resources through which people have access to live a sustainable and fulfilling life and can be measured through numerous avenues and framings (Mallick and Sultana 2017). The Sustainable Livelihood Approach (SLA) is one common lens to understand how people generate a livelihood and how interventions can be designed effectively and appropriately in light of these (Scoones 1998). The SLA considers assets across five capitals (natural, social, financial, human, physical) to be essential to how people can build a livelihood (Bebbington 1999; Morse and McNamara 2013). Owing to the impact of relocation on culture, as well as this being an often-understudied aspect of livelihoods, including the invisible assets of spirituality, connection to place, and ritual (Kingston and Marino 2010), the addition of cultural capital is included here. Assessing the outcomes of relocation using the livelihood assets from the SLA framework has similarly been employed by previous researchers (Mallick and Sultana 2017).

The data gathered from the seven focus groups and 15 interviews were compiled. This data were disaggregated according to the six livelihood asset groups employed in this research: Natural, social, financial, human, physical, and cultural capital. The livelihood analysis focussed on changes in livelihoods as experienced by community members since the relocation. Changes that were commonly identified within the data were coded as a positive, negative or no change. This allowed understanding and exploration of the impact from relocation across each asset group and formed the basis for the results.

3.2. Ethical Procedures

Ethical procedures under the guidelines of the University of Queensland were followed. This included gaining informed consent from participants to participate in this study, and undertake and record FGs and interviews. It is important to acknowledge that Vunidogoloa, known widely as the first climate change relocation site, has had many visitors. This was especially prominent as the research team visited while the recent Conference of the Parties (COP) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) was occurring. As Fiji was hosting this event (externally in Germany), there was high exposure of this site and numerous journalists had recently visited Vunidogoloa. As such, undertaking appropriate ethical procedures such as discussing the research, including aims, data collection, storage and analysis, expectations, confidentiality, outputs, and opportunities for feedback, prior to seeking participants’ informed consent was essential.

3.3. Study Limitations

There were a number of limitations experienced in this research. First, as the research used primarily qualitative methods, there is the assumption that the information provided by participants was true and honest as to their own experiences. Alternatively, there might have been a high level of positive response bias during FGs and interviews. This is especially relevant when considering how the large number of visitors in Vunidogoloa might influence participants’ responses. Second, the use of translators can cause issue with difficulty translating some words (Rudiak-Gould 2012). Third, not revisiting Denimanu for a follow-up visit to allow clarification is seen as another limitation. Finally, many questions involved asking the participants to retrospectively provide information on life prior to relocation for which there could be some issues related to memory.

4. Socio-Political Context of Relocations

The socio-political context in which these two relations sit varies significantly. In Vunidogoloa, it was the village headman who approached the government asking to be relocated (Charan et al. 2017). After initial discussions, the village was planned to be relocated in 2012, although this was eventually delayed until January/February 2014. The delays stemmed from a range of factors including concerns that the chosen site was not stable and unduly exposed to erosion, as well as delays in building the new houses (Tronquet 2015). Vunidogoloa is seen as the ‘poster child’ for climate change relocations, exemplified by the numerous publications and news articles about the relocation (Brill 2017; Charan et al. 2017; Meakins 2017; Rubeli 2015; Tronquet 2015; Witschge 2018). Since the most recent election (November 2018), Fijian Prime Minister Bainimarama has publicly referred to the people of Vunidogoloa as liumuri (backstabbers) as they stated they did not vote for him despite his government relocating the village (Rawalai 2018), possibly exemplifying a level of political expectation resulting from the relocation. On the contrary, the relocation in Denimanu sits within a different context, garnering little public and media attention with few articles that discuss it in detail (exceptions include Bukalidi 2013; Martin et al. 2018).

Within both villages, there was an expressed lack of involvement in decision-making processes by the village members themselves. Within Vunidogoloa while it has been posited that the process was based on “a consensual and participative decision-making process” (Tronquet 2015, p. 29) local residents stated that a lot of what was discussed did not come to fruition: “All the government agencies came in to the new site so we think that everything will be done … once it is about to finish and we find out that some things were wrong because we were never informed, we were just told. We believe [decisions] were just between the contractors and the government” (Vunidogoloa FG, Men). In Denimanu, village members stated that there was no real consultation with the community at all pertaining to what would be included in the relocation, but rather it was informed by the government that a relocation would happen: “They came to the village and notified us of the relocation in an information session and they gave us the reason why we have to relocate” (Denimanu FG, Men).

While there were concerns expressed about a lack of participatory consultation with the entire community, women felt that due to societal and cultural norms they were specifically unable to voice their opinions about the relocation. This sentiment is expressly voiced through the following comments by both villages: “The men agreed to relocate… we would like to say that the men don’t consult us. Only the men, the village headman, and the chief, they discuss… We are just told to listen. When the men say we have to go, we have to go. If they say we have to relocate, we relocate.” (Denimanu FG, Women); and “For us, the women, we just listen to whatever the men say and we just agree. They never consult us. The voice of the men is the only voice that is heard, so we just listen to that voice. So whatever the men has agreed we just consent to it” (Vunidogoloa FG, Women). These comments confirm that the gendered cultural and societal norms, which often exclude women from decision-making processes, were not adequately addressed through the process of these relocations, serving to perpetuate rather than alleviate such inequalities.

5. To What Extent Have Livelihoods Been Either Positively or Negatively Affected by Relocation?

The UNHCR climate change relocation guidelines state Relocated Persons should be supported to maintain their traditional or previous livelihoods, and, if not able to be done, the provision of new opportunities for livelihoods suitable to the resettlement site should be afforded. Owing to the importance of accounting for livelihoods both through a long history of deleterious outcomes arising from resettlements, as well as being an important aspect of vulnerability reduction, here a livelihood perspective is taken to understand the impacts on affected people from the relocation process. The outcomes of relocation as expressed by community members are shown in Table 1 across natural, social, financial, human, physical and cultural capital. Four sub-sections will be discussed below as they offer insights and contrasts between the two relocated communities: Housing and community infrastructure, social cohesion and cultural assets, health and education, and access to common property resources and food security.

Table 1.

Outcomes on community livelihoods from the village relocations in two communities, denoted as: Positive change (+), no change (0), negative change (−).

5.1. Housing and Community Infrastructure

In both villages, following relocation, there were improvements in housing and community infrastructure. Of note is the provision of facilities in the new village compared to the old village. Solar power was made available for all new households in both villages, and water tanks were provided in Denimanu. In the previous locations only a limited number of people had access to electricity. Further, flush toilets and showers were also installed in both new villages. While the relocation did provide numerous benefits to the villages as documented above, concerns surrounding appropriateness and sustainability of such were raised. In Vunidogoloa, the houses did not include a kitchen as promised, a potential outcome of the rush to finalise the relocation. This meant that villagers had to build kitchens themselves. In Denimanu, when the rain is strong the water leaks into the houses in the new village: “So when it rains heavily the whole house is wet… overall it is just poor because we have water seep through the door frames and go inside so it rusts and then you can’t open the door” (Denimanu FG, Women). This is a key concern considering Fiji is located in the tropics with heavy rainfall throughout much of the year. It was further explained that the showers and toilets blocked regularly. Further, drainage systems were not sufficiently implemented in either village, causing major erosion concerns. In Vunidogoloa, the government came back to address this aspect of the relocation, but it has still not been completed at the time of research with unused drain pipes scattered around the village.

5.2. Social Cohesion and Cultural Assets

Vunidogoloa residents were emphatic that they felt the sense of community had strengthened during and since the relocation. This was expressed because participants felt that the community had come together and made the decision to move themselves, representative of the fact that it was the village headman who approached the government to relocate. People also stated that they found strength in their Christian faith through coming together as a community and overcoming the struggle of moving: “A lot of our faith in relocating was placed in our belief. We did a lot of prayer sessions” (Vunidogoloa Interview). In Denimanu, while on average there was an overall improvement in social cohesion, when disaggregating this across men and women, women noted improvements while men experienced negative outcomes. The women’s group noted that the relocation has strengthened a sense of community because the process forced them to work together. The men discussed some challenges with working together on village projects. These findings pertaining to social cohesion can be largely explained by two factors: the size of the village and the type of relocation. Vunidogoloa being a small village and relocated as an entire unit meant that they were able to stay together and united throughout the process. Denimanu on the other hand is a larger village and was only partially relocated therefore disrupted aspects of daily life and activities for some residents. In terms of the cultural impact of the relocation on communities, the impacts were reduced due to both villages relocating within closely-related mataqali lands. Yet, the move away from the ocean in Vunidogoloa has impacted spiritual ties as the ocean is an important part of village culture.

5.3. Health and Education

Mixed outcomes across health and education were noted across villages. In Denimanu, challenges associated with septic tanks in the relocated village were noted regularly throughout village discussions. There were only two sewage septic tanks provided for the 19 houses. As a result of this, health concerns were noted by some women, as they were responsible for regularly cleaning out the septic tanks. These issues experienced by women pertaining to cleaning the septic tank are explained through the following comment: “We have to do it. So we put on our pants, cover our noses, cover our hair with plastic, and we wear gloves and we take turns bailing the septic tank. So all the women in the house have to help out, the men don’t and say wait for the government but we know the children will get sick” (Denimanu FG, Women). Further, the relocated village expressed that the health center was going to be moved in between the original and relocated villages yet remains at the opposite side of the original village, thus making access more challenging for them. As the relocated village only moved roughly 500 m this is not seen as a major detriment.

In Vunidogoloa, positive outcomes occurred in terms access to services, specifically schooling for children and medical services. This is due to the relocated village being close to the main road as these services are only available using road transport: “The relocation was good because it is [now] easy to go to school as you have been to the old village you know how hard it is to get to the main road to catch the bus to go to school” (Vunidogoloa FG, Women).

5.4. Access to Common Property Resources and Food Security

Access to common property resources has been maintained in both villages due to the short distance of the relocations. In Vunidogoloa the community moved within walking distance from the old site. This makes the old site and the resources that are there still available for people to use. Examples include the ocean where people still go down to fish regularly. Yet this has resulted in fishing becoming harder because of the extended distance to access the ocean, formerly their main livelihood source. People also go down to the old site to collect coconuts and pandanus leaves for weaving. As Denimanu moved only 500m there has been no disruption to access of common property resources. While food security has been unperturbed in Denimanu, in Vunidogoloa village members noted improvements since the village is now located on the land where previous agriculture and crop production was undertaken. Closeness to agricultural fields has resulted in reduced labour inputs due to reduced walking distances. Further, within Vunidogoloa there was provision of pineapple crops, cattle, and fish ponds, all of which are utilized by the village, although the residents expressed the quantity of each provided to the village were less than promised: “Just to give an example, the pineapple farm, the Ministry of Agriculture promised we would be given 48,000 tops but they only gave 5000. This is just an example, for the fish ponds they told us they were going to dig eight they only gave four” (Vunidogoloa FG, Men). These outcomes have also improved the financial security of village members in Vunidogoloa due to surplus food crops to sell at markets, especially since access to markets has improved from road access.

Overall, there have been numerous positive livelihood outcomes that have arisen as a result of the relocation. Yet, notably there have been some serious implications as well. We can see that the benefits of both villages in being able to move within close mataqali is clear as it has allowed spiritual connections to be maintained as well as access to common property resources which are important components of village livelihoods. Further, the positive outcomes associated from the whole community relocating, as was the case in Vunidogoloa, has allowed the community to maintain a strong sense of social cohesion and unity.

7. What Lessons Can Be Taken from These Case Studies Going Forward?

Relocations resulting from climate change and associated impacts are likely to significantly increase into the future (Ferris 2015). As early cases of planned relocation, these two examples provide an important avenue to take lessons that can be applied to future relocation efforts in order to move toward more effective, beneficial and sustainable outcomes for relocated communities. This is especially relevant in a Fijian context as at least 80 communities have been earmarked for relocation but can also apply to other comparable island communities.

Participatory decision-making process is the first theme that emerged from the case studies. Namely, the lack of involvement community members expressed they had in the decision-making pertaining to the relocation. The importance of such a participatory process has been outlined by researchers (Correa et al. 2011; de Sherbinin et al. 2011; Ferris 2015; Kingston and Marino 2010; McAdam and Ferris 2015; McNamara and Jacot des Combes 2015) as well as in the established international guidelines (UNHCR 2015) and the Fiji guidelines for relocations (Fiji Government 2018). Yet as we see from these case studies, communities expressed that transparency throughout the process was lacking, specifically in the case of Denimanu. The process employed can be seen as consultation rather than participation, of which a distinct difference exists (McAdam and Ferris 2015). While communities in both villages were consulted (in that they were instructed about the relocation), there was an expressed lack of comprehensive participation, through which communities felt they were not able to significantly contribute to decision-making processes. Including affected communities throughout the relocation process, to ensure the opportunity for self-identified priorities is essential if affected communities are to have the possibility to not only rebuild but also improve their livelihoods in the relocated site (Kingston and Marino 2010; McNamara et al. 2018). Building on top of this, through the planning stage of relocation critical concepts of human rights, dignity, equity, and sustainability should be closely considered and applied (Henly-Shepard et al. 2018). For example, while processes must aim to include local perspectives, they must further intentionally aim to include multiple and diverse groups within the process to ensure there is an equitable avenue for a range of perspectives to be expressed.

Long term monitoring and evaluation is the second theme that emerged. There have been numerous issues that have arisen since the relocation, expressed in both villages. These span issues with water leaking into homes, incomplete drainage systems, inadequate sewage, and safety concerns from erosion. Unforeseen outcomes, even with appropriate planning and forethought, would not be unexpected when implementing such large-scale adaptation interventions. As seen in these two cases, these issues that have arisen have not been rectified. Further, both villages expressed that contact with the government since the relocation has been limited with no formal avenue available to express ongoing concerns. Without a level of reflection and a willingness to rectify errors then there is a genuine concern that these unintended negative outcomes could lead to maladaptation, in that there is an increase in community vulnerability in the long term. As such, incorporating formal mechanisms through which village members can express such concerns and ensure a level of accountability is seen as essential going forward.

Targeted livelihood planning is the third theme that emerged. Vulnerability to climate change goes beyond solely a reduction of exposure to physical hazards and includes improving livelihood resilience (Jackson et al. 2017). The relocation of vulnerable communities should be used as an opportunity to not only reduce physical exposure to climate threats, but also build upon other social and economic vulnerabilities and processes (de Sherbinin et al. 2011). In Vunidogoloa, the provision of livelihood alternatives in the new sites (such as pineapple plantations, fish ponds, and cattle) improved outcomes across natural and financial capital, with further improvements of access to assets from moving closer to the main road. This is an example of how improving services, assets, and availability of resources is one avenue through which positive outcomes from relocation can be achieved. As such, a focus on this aspect of relocation, in not only reducing the physical threat of climate change hazards communities are facing but taking a holistic view of community vulnerability, and ensuring that relocation aims to improve upon the livelihood resilience of affected communities, should be considered as an essential part in achieving success during the relocation process.

8. Conclusions

This research documented the experiences of two communities that have been relocated as a consequence of climate change related impacts. The two case studies showcase differences in the contexts around relocation with Vunidogoloa, labeled as the first ‘climate-induced’ relocation, being a full village relocation resulting from slow-onset impacts. Garnering much less attention, the second case study, Denimanu, was a partial village relocation from sudden-onset impacts. The outcomes of the relocations have shown several positive outcomes, namely in relation to improved housing, and improved access to electricity and facilities. Yet for some residents, these have been somewhat overshadowed by many negative outcomes. For example, serious concerns were raised pertaining to the quality of housing in Denimanu with water leaking through walls. Further, impacts resultant from poor design of sewage septic tanks in Denimanu, and drainage systems in both villages are of concern. This is especially the case in Denimanu where these have led to increased levels of exposure to new threats surrounding mass movement of sediment. The results from this research further indicate wider implications across how women and men experience planned adaptation, both in terms of access to decision-making and on resultant outcomes on lives and livelihoods.

As planned climate-induced relocations will become more common in the future, key lessons from people’s experiences in these two case studies are presented that should be built into future planning going forward. These lessons include: Inclusive decision-making processes, as communities felt they did not have adequate input and agency in the process; long term monitoring and evaluation to ensure an avenue is provided for people to voice concerns and issues that have arisen from the process; and targeted livelihood planning to improve livelihoods with the aim of reducing overall vulnerability. Relocation of entire villages is a complex and significant undertaking, so it is imperative that governments and external parties involved in the process take appropriate steps to ensure the process serves to improve the livelihoods and lives of those directly affected.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.E.P.-M., K.E.M., and P.D.N.; Methodology, A.E.P.-M., K.E.M., P.D.N., and S.T.S.; Formal analysis, A.E.P.-M.; Investigation, A.E.P.-M. and S.T.S.; Writing—original draft preparation, A.E.P.-M.; Writing—review and editing, A.E.P.-M., K.E.M., and P.D.N.; Supervision, K.E.M. and P.D.N.; Project administration, P.D.N., S.T.S. and A.E.P.-M.; Funding acquisition, K.E.M. and P.D.N.

Funding

This research was funded through an Australian Research Council Linkage grant (number LP160100941).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to sincerely thank the residents of Vunidogoloa and Denimanu for welcoming the research team into their homes and sharing their story. This research would not be possible without them. Further, to Sekaia Malani who acted as a gatekeeper and aided the research team immensely with the organization and logistics of fieldwork. Finally, to Jacqueline Ryle and Jasmine Pearson who provided important contributions and insights during fieldwork.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Albert, Simon, Robin Bronen, Nixon Tooler, Javier Leon, Douglas Yee, Jillian Ash, and David Boseto. 2018. Heading for the Hills: Climate-driven Community Relocations in the Solomon Islands and Alaska Provide Insight for a 1.5 °C Future. Regional Environmental Change 18: 2261–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Althor, Glenn, James E. M. Watson, and Richard A. Fuller. 2016. Global Mismatch between Greenhouse Gas Emissions and the Burden of Climate Change. Scientific Reports 6: 20281. [Google Scholar]

- Arora-Jonsson, Seema. 2011. Virtue and Vulnerability: Discourses on Women, Gender and Climate Change. Global Environmental Change 21: 744–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, Jon, and John Campbell. 2010. Climate Change and Small Island States: Power, Knowledge, and the South Pacific. London and Sterling: Earthscan. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett, Jon, and Celia McMichael. 2018. The Effects of Climate Change on the Geography and Timing of Human Mobility. Population and Environment 39: 339–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, Jon, and Saffron J. O’Neill. 2011. Islands, resettlement and adaptation. Nature Climate Change 2: 8–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bebbington, Anthony. 1999. Capitals and Capabilities: A Framework for Analyzing Peasant Viability, Rural Livelihoods and Poverty. World Development 27: 2021–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brill, Barry. 2017. Fiji’s ‘Sinking’ Vunidogoloa Village—Victim of AGW or Opportunistic at #COP23? Available online: https://wattsupwiththat.com/2017/11/08/fijis-sinking-vunidogoloa-village-victim-of-agw-or-opportunistic-at-cop23/ (accessed on 10 December 2018).

- Bukalidi, Litia. 2013. Yadua Village Relocated. Available online: http://fijisun.com.fj/2013/04/13/yadua-village-relocated/ (accessed on 10 December 2018).

- Campbell, John. 2010. Climate-Induced Community Relocation in the Pacific: The Meaning and Importance of Land. In Climate Change and Displacement: Multidisciplinary Perspectives. Edited by Jane McAdam. London: Hart Publishing, pp. 58–59. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, John. 2014. Climate-Change Migration in the Pacific. The Contemporary Pacific 26: 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, John, and Richard Bedford. 2014. Migration and climate change in Oceania. In People on the Move in a Changing Climate: The Regional Impact of Environmental Change on Migration. Edited by Etienne Piguet and Frank Laczko. Global Migration Issues. Dordrecht: Springer, vol. 2, pp. 177–204. [Google Scholar]

- Carr, Edward R. 2008. Between Structure and Agency: Livelihoods and Adaptation in Ghana’s Central Region. Global Environmental Change 18: 689–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cernea, Michael. 1997. The risks and reconstruction model for resettling displaced populations. World Development 25: 1569–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chand, Savin S., Kevin J. Tory, Hua Ye, and Kevin J. E. Walsh. 2016. Projected Increase in El Niño-driven Tropical Cyclone Frequency in the Pacific. Nature Climate Change 7: 123–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charan, Drishna, Manpreet Kaur, and Priyatma Singh. 2017. Customary Land and Climate Change Induced Relocation—A Case Study of Vunidogoloa Village, Vanua Levu, Fiji. In Climate Change Adaptation in Pacific Countries: Fostering Resilience and Improving the Quality of Life. Edited by Walter Leal Filho. Cham: Springer, pp. 19–33. [Google Scholar]

- Connell, John. 2015. Vulnerable Islands: Climate Change, Tectonic Change, and Changing Livelihoods in the Western Pacific. The Contemporary Pacific 27: 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Connell, John. 2016. Last days in the Carteret Islands? Climate change, livelihoods and migration on coral atolls. Asia Pacific Viewpoint 57: 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa, Elena, Fernando Ramirez, and Haris Sanahuja. 2011. Populations at Risk of Disaster: A Resettlement Guide. Washington, DC: World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- De Sherbinin, Alex, Marcia Castro, Francois Gemenne, M. M. Cernea, Susana Adamo, P. M. Fearnside, Gary Krieger, S. Lahmani, A. Oliver-Smith, A. Pankhurst, T. Scudder, and et al. 2011. Preparing for Resettlement Associated with Climate Change. Science 334: 456–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodman, David, and Diana Mitlin. 2013. Challenges for Community-Based Adaptation: Discovering the Potential for Transformation. Journal of International Development 25: 640–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donner, Simon D. 2015. The legacy of migration in response to climate stress: Learning from the Gilbertese resettlement in the Solomon Islands. Natural Resources Forum 39: 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferris, Elizabeth. 2015. Climate-Induced Resettlement: Environmental Change and the Planned Relocation of Communities. The SAIS Review of International Affairs 35: 109–17. [Google Scholar]

- Fiji Government. 2018. Planned Relocation Guidelines: A Framework to Undertake Climate Change Related Relocation. Available online: https://www.refworld.org/docid/5c3c92204.html (accessed on 18 April 2019).

- Foresight. 2011. Migration and Global Environmental Change: Final Project Report; London: The Government Office for Science.

- George, Nicole. 2010. ‘Just like your Mother?’ The politics of feminism and maternity in the Pacific Islands. Australian Feminist Law Journal 32: 77–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, Nicole. 2014. Promoting women, peace and security in the Pacific Islands: Hot conflict/slow violence. Australian Journal of International Affairs 68: 314–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharbaoui, Dalila, and Julia Blocher. 2016. The reason land matters: Relocation as adaptation to climate change in Fiji Islands. In Migration, Risk Management and Climate Change: Evidence and Policy Responses. Edited by Andrea Milan, Benjamin Schraven, Koko Warner and Noemi Cascone. Cascone: Springer International Publishing Switzerland, pp. 149–73. [Google Scholar]

- Heltberg, Rasmus, Paul Bennett Siegel, and Steen Lau Jorgensen. 2009. Addressing human vulnerability to climate change: Toward a ‘no-regrets’ approach. Global Environmental Change 19: 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henly-Shepard, Sarah, Karen E. McNamara, and Robin Bronen. 2018. Stories of climate change and mobility from around the world: Institutional challenges and implications for community development. In The Routledge Handbook of Community Development Research. Edited by Shevellar Lynda and Peter Westoby. London: Routledge, pp. 197–209. [Google Scholar]

- Hino, Miyuki, Christopher B. Field, and Katharine J. Mach. 2017. Managed Retreat as a Response to Natural Hazard risk. Nature Climate Change 7: 364–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huq, Saleem, and Hannah Reid. 2007. Community-Based Adaptation: A Vital Approach to the Threat Climate Change Poses to the Poor. International Institute for Environment and Development Briefing. Available online: http://www.iied.org/pubs/pdfs/17005IIED.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2018).

- IOM. 2018. Vanuatu Launches National Policy on Climate Change and Disaster-Induced Displacement. Available online: https://www.iom.int/news/vanuatu-launches-national-policy-climate-change-and-disaster-induced-displacement (accessed on 15 January 2019).

- IPCC. 2014a. Annex II: Glossary [Mach, K.J., S. Planton and C. von Stechow (eds.)]. In Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Edited by Core Writing Team, R. K. Pachauri and L. A. Meyer. Geneva: IPCC, pp. 117–30. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC. 2014b. Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Edited by Core Writing Team, R. K. Pachauri and L. A. Meyer. Geneva: IPCC. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, Guy, Karen McNamara, and Bradd Witt. 2017. A Framework for Disaster Vulnerability in a Small Island in the Southwest Pacific: A Case Study of Emae Island, Vanuatu. International Journal of Disaster Risk Science 8: 358–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janif, Shaiza Z., Patrick D. Nunn, Paul Geraghty, William Aalbersberg, Frank R. Thomas, and Mereoni Camailakeba. 2016. Value of traditional oral narratives in building climate-change resilience: Insights from rural communities in Fiji. Ecology and Society 21: 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keener, Victoria. W., John J. Marra, Melissa L. Finucane, Deanna Spooner, and Margaret Smith. 2012. Climate Change and Pacific Islands: Indicators and Impacts. Report for the 2012 Pacific Islands Regional Climate Assessment (PIRCA). Washington, DC: Island Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kelman, Ilan. 2014. No change from climate change: Vulnerability and small island developing states. Geographical Journal 180: 120–29. [Google Scholar]

- Kingston, Deanna M., and Elizabeth Marino. 2010. Twice Removed: King Islanders’ Experience of “Community” through Two Relocations. Human Organisation 69: 119–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, Lalit, and Subhashni Taylor. 2015. Exposure of coastal built assets in the South Pacific to climate risks. Nature Climate Change 5: 992–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipset, David. 2013. The New State of Nature: Rising Sea-levels, Climate Justice, and Community-based Adaptation in Papua New Guinea. Conservation and Society 11: 144–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallick, Bishawjit, and Zakia Sultana. 2017. Livelihood after relocation-evidences of Guchchagram project in Bangladesh. Social Sciences 6: 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, Piérick C. M., Patrick D. Nunn, Javier Leon, and Neil Tindale. 2018. Responding to multiple climate-linked stressors in a remote island context: The example of Yadua Island, Fiji. Climate Risk Management 21: 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAdam, Jane, and Elizabeth Ferris. 2015. Planned relocations in the context of climate change: Unpacking the legal and conceptual issues. Cambridge Journal of International and Comparative Law 4: 137–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMichael, Celia, Carol Farbotko, and Karen E. McNamara. 2018. Climate-migration responses in the Pacific region. In The Oxford Handbook of Migration Crises. Edited by Cecilia Menjívar, Marie Ruiz and Immanuel Ness. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- McNamara, Karen E., and Helene Jacot des Combes. 2015. Planning for Community Relocations Due to Climate Change in Fiji. International Journal of Disaster Risk Science 6: 315–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNamara, Karen E., Rachel Clissold, Annah E. Piggott-Mckellar, Lisa Buggy, and Aishath Azfa. 2017. What is shaping vulnerability to climate change? The case of Laamu Atoll, Maldives. Island Studies Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNamara, Karen E., Robin Bronen, Nishara Fernando, and Silja Klepp. 2018. The complex decision-making of climate-induced relocation: Adaptation and loss and damage. Climate Policy 18: 111–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meakins, Brook. 2017. An Inside Look at the One of the First Villages Forced to Relocate Due to Climate Change. Available online: https://www.alternet.org/environment/inside-look-one-first-villages-forced-relocate-due-climate-change (accessed on 2 January 2019).

- Morse, Stephen, and Nora McNamara. 2013. Sustainable Livelihood Approach: A Critique of Theory and Practice. Dordrecht: Springer. ISBN 9789400762688. [Google Scholar]

- Nunn, Patrick D. 2009. Responding to the challenges of climate change in the Pacific Islands: Management and technological imperatives. Climate Research 40: 211–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunn, Patrick D., and Roselyn Kumar. 2018. Understanding climate-human interactions in Small Island Developing States (SIDS). International Journal of Climate Change Strategies and Management 10: 245–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawalai, Luke. 2018. Villagers Branded as ‘Liumuri’ after No One Voted for Party. Available online: https://www.fijitimes.com/villagers-branded-as-liumuri-after-no-one-voted-for-party/ (accessed on 20 January 2019).

- Republic of Fiji. 2014. Second National Communication to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Available online: https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/natc/fjinc2.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2018).

- Rubeli, Ella. 2015. Escaping the Waves: A Fijian Village Relocates. Available online: https://www.smh.com.au/lifestyle/escaping-the-waves-a-fijian-villages-forced-relocation-20150831-gjc0k1.html (accessed on 5 October 2018).

- Rudiak-Gould, Peter. 2012. Promiscuous corroboration and climate change translation: A case study from the Marshall Islands. Global Environmental Change-Human and Policy Dimensions 22: 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scoones, Ian. 1998. Sustainable Rural Livelihoods: A Framework for Analysis. IDS Working Paper 72. Brighton: IDS. [Google Scholar]

- Singh-Peterson, Lila, and Manoa Iranacolaivalu. 2018. Barriers to market for subsistence farmers in Fiji—A gendered perspective. Journal of Rural Studies 60: 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadgell, Anne, Brent Doberstein, and Linda Mortsch. 2018. Principles for climate-related resettlement of informal settlements in less developed nations: A review of resettlement literature and institutional guidelines. Climate and Development 10: 102–15. [Google Scholar]

- Tronquet, Clothilde. 2015. From Vunidogoloa to Kenani: An Insight into Successful Relocation. Available online: http://labos.ulg.ac.be/hugo/wp-content/uploads/sites/38/2017/11/The-State-of-Environmental-Migration-2015-121-142.pdf (accessed on 5 October 2018).

- UNHCR. 2015. Guidance on Protecting People from Disasters and Environmental Change through Planned Relocation. Available online: https://environmentalmigration.iom.int/sites/default/files/Guidance%20on%20Planned%20Relocations%20-%20Split%20PDF.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2018).

- Voccia, Alexander. 2011. Climate Change: What Future for Small, Vulnerable States? International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology 19: 101–15. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, Kevin J. E., John L. McBride, Philip J. Klotzbach, Sethurathinam Balachandran, Suzana J. Camargo, Greg Holland, Thomas R. Knutson, James P. Kossin, Tsz-cheung Lee, Adam Sobel, and et al. 2016. Tropical Cyclones and Climate Change. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change 7: 65–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weir, Tony, Liz Dovey, and Dan Orcherton. 2017. Social and Cultural Issues Raised by Climate Change in Pacific Island Countries: An Overview. Regional Environmental Change 17: 1017–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A. T., Nelson Rangel-Buitrago, Enzo Pranzini, and Giorgio Anfuso. 2018. The management of coastal erosion. Ocean & Coastal Management 156: 4–20. [Google Scholar]

- Witschge, Loes. 2018. In Fiji, Villages Need to Move Due to Climate Change. Available online: https://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/features/fiji-villages-move-due-climate-change-180213155519717.html (accessed on 10 October 2018).

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).