1. Introduction

This special issue considers the question of shifting bordering practices in a North American context, particularly British Columbia. The focus of this issue raises a number of initial questions for us. In the first instance, if bordering practices are ‘shifting’ then where to begin our critical engagement? Geographical referents like ‘North America,’ ‘Canada’ or—seemingly more precise locales like—‘British Columbia’ provide no simple answer to this question. Given the increasingly interconnected and diffuse ways in which moving bodies/objects/energies are managed (

Bigo 2010;

Bridge and Le Billon 2012;

Salter 2004), these referents hardly offer firm ground from which to enter conversation.

We approach British Columbia less as a fixed starting point and more as an invitation to probe and problematize (

Agnew 1994). As feminist geographers have long argued, when we begin our analysis from the level of the region (be it ‘the EU’ or ‘North America’) and take such constructs as ontologically given, we risk reifying them as a stable territorial fact. In so doing we fail to acknowledge the myriad ways in which regions are produced through ongoing displacement and dispossession. We risk “obscuring violence happening at other scales” that are part of this production (

Andrijasevic 2010;

Hyndman 2004). Moreover, we obscure dynamic struggles that exceed tidy containment.

Building on the work of feminist geographers we choose to critically interrogate ‘the region’ through an intimate scale: the partial story of a woman named Lucía Vega Jiménez (Ibid.,

Pratt and Rosner 2006). We explore her encounters with a hostile asylum regime, and particularly how this took shape in the city of Vancouver—the unceded territories of the Musqueam (xʷməθkʷəy̓əm), Tsleil-Wauthuth (Səl̓ílwətaʔ/Selilwitulh) and Squamish (Skwxwú7mesh Úxwumixw) nations. We will make the case that Lucía’s story, though unique, begins to unravel more widely (and unevenly) felt features of an asylum landscape in ways that expose how British Columbia is imagined, who it includes, excludes and how its colonial borders are actively being policed and challenged through the urban.

2. Lucía Vega Jiménez

Lucía Vega Jimenez lived and worked in Metro Vancouver, Coast Salish Territories. The 42-year old woman had fled her country of origin, Mexico, and applied for refugee status in Canada but her claim was refused in 2011. Afraid to return to Mexico, she continued to live in the city, undocumented and employed as a hotel cleaner. On 1 December 2013 Lucía was taking the city’s fast-speed transit, the Skytrain. During a ‘routine’ fare check the Transit Police, contracted out to a private security company, asked Lucía to provide her citizenship papers. When she did not supply these papers the Transit Police handed her over to Canadian Border Agency (CBSA). She was detained for three weeks, first at the Alouette Correctional Centre and then transferred to a CBSA holding cell—located below Vancouver International Airport, YVR.

In a shower stall located in her cell Lucía hung herself on 20 December 2013, days before her scheduled deportation to Mexico. She died eight days later at Mount St. Joseph Hospital in Vancouver. It was almost a full month before the news of her death was made public. When her sister came to pick up Lucía’s remains, she was reportedly asked by CBSA to sign a non-disclosure agreement.

What can be said of this loss? Being in contact with community and advocacy groups who knew Lucía; many insist that her story needs to be publicly examined and told (

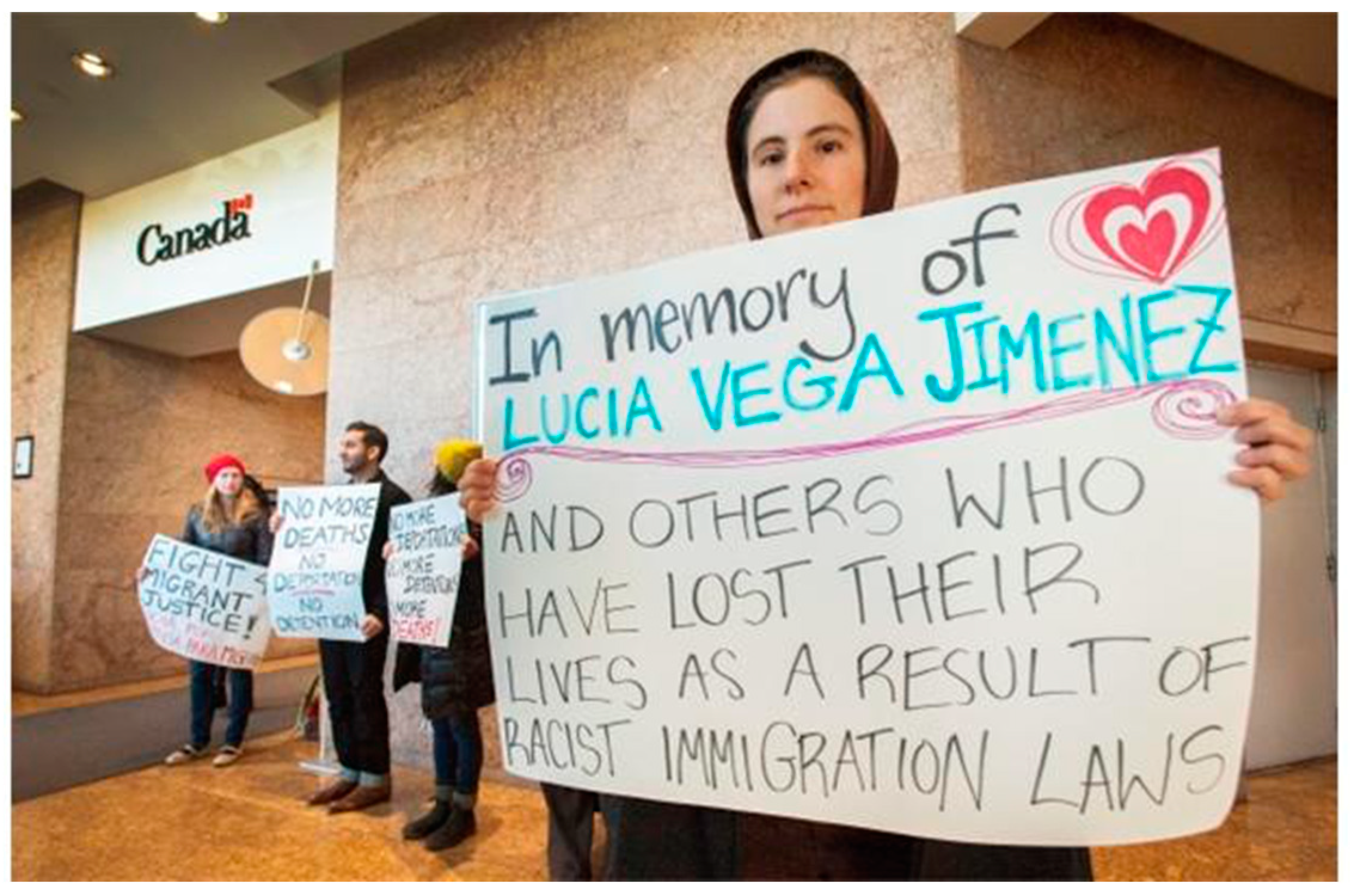

Walia 2014). The protesters who brought a box full of 7500 signatures to Vancouer’s CBSA Offices, as pictured below (see

Figure 1), demanding an inquiry into the death of Lucía clearly held this view.

Conversely, what cannot be said? (

Edkins 2013) The fact that Lucía’s death was unreported by CBSA, and her own family was silenced, reminds us how the asylum regime which failed this woman seeks to obscure its role in producing precarious life and death. Yet how Lucía’s story gets told, and by whom, for us is a question for which there are no easy answers. However difficult it may be, migrant justice organizations, such as No One is Illegal, who continue to be in touch with Lucía’s family argue that the task of rendering legible such stories and speaking truth to power (

Foucault 1980) remains important, collective work. This paper is an attempt, in part, to contribute to this political work. We draw insight from Judith Butler who contends that the affective power of loss can be productive, it may even be a “resource for the future” (2003). We also take guidance from Geraldine Pratt who, experimenting with different forms of testimony, states “we tell stories of loss—irreversible loss—with the hope of animating a different future” (

Pratt 2012).

With this in mind, we ask: what might this loss expose about the management of migration and asylum and how it might be otherwise?

Here, we will highlight four features, or traces. First, Lucia’s story points to the ways in which Canada’s determination process invisibilises certain forms of violence and, as such, serves as a highly restrictive and exclusionary mechanism. Those invisible violences of making migration irregular (

Johnson 2014), illegal (

De Genova 2013;

Dauvergne 2009), and precarious (

Goldring et al. 2009), all rely on particular—seemingly innocuous—urban logics (

Curtis 2016). Second, we show how this exclusionary mechanism extends (like ‘capillaries’) throughout urban space. In this context, city services (like transit) increasingly become privatized border checkpoints. Third, we show how these city checkpoints funnel people with precarious status into remote detention. Vitally, we argue that remoteness cannot be understood simply across the urban landscape, but also below. A more sophisticated vertical geographical analysis is required if we hope to critically understand and interrupt the proliferation of hostile—indeed deadly—bordering practices. Finally, we examine how these carceral dimensions are being politicized, agonistically, through sanctuary practices in and across cities.

3. Domesticating Violence

The first feature of the asylum landscape that Lucía’s story reveals is how Canada’s current determination process fails to recognize as legitimate gendered, and other intersecting forms of domestic violence (

Pain 2015). According to Claudia Franco Hijuelos, Consul-General of Mexico, Lucía “was fearful of going back to Mexico, not the country but specifically to some domestic situation she might face” (

Woo 2014). This was ultimately deemed an unreal fear in 2011 when her asylum claim was denied (despite the fact that she took her own life to prevent being returned to this situation).

Troublingly, Lucía is not alone in this. According to Vancouver-based organization, Battered Women’s Support Services, a vast number of Mexican women who seek refuge in Canada have been rejected because according to the Immigration and Refugee Board (IRB), “Mexico has a system of functioning democratic institutions.” Nevertheless, according to a UN report Mexico was ranked first globally in sexual violence against women, reporting 120,000 violations in 2010. The Ministry of Health estimates that in Mexico one woman every four minutes is raped; yet to date there is no comprehensive care for the victims. In Ciudad Juarez, Mexico, since 1990 women continue to be murdered and go missing. 2012 was one of the years with the highest femicides in that city.

Like Lucía, after failing an asylum claim many are forced to become undocumented—living in a precarious state where basic rights and access to services are denied. While media, especially in Canada, celebrates Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s response to ‘global’ displacement through the spectacular welcome of 25,000 Syrian refugees, Lucía’s story reminds us how Canada’s limited asylum regime is also actively producing vast irregularization. According to Byron Cruz, an organizer in Vancouver’s sanctuary movement, there are between 3000 and 5000 undocumented immigrants from Latin America living in Metro Vancouver. Such figures, by Cruz’s own account, are misleading for they cannot begin to address the growing number of Temporary Foreign Workers (notably those employed through Canada’s Caregiver Program and Seasonal Agricultural Worker program) and many others with precarious citizenship.

4. Urban Capillaries

Lucia’s story also reveals how barriers to asylum extend, insidiously, into urban space. Lucía’s detention resulted from an arrest while she attempted to move through the city on local transit. Border enforcement is thus not only exercised at the edge of the Canadian state, or what we might call an increasingly harmonized US-Canadian region; rather, securitization permeates, like capillaries, into everyday city life where the movement of certain migrant bodies are under intense control.

This point resonates with a growing body of academic work that claims, if we are to understand shifting asylum landscapes we need to pay better attention to urban processes and services which are entangled in border control (

Sanyal 2011;

Ramadan 2013;

Hyndman 2000). It is especially critical, many schoalrs have pointed out, that we pay attention to the urban given that millions of refugees and displaced people have been resettled in urban centres, whilst temporary camps begin to resemble cities.

1While a growing field of migration research has drawn attention to the urban as a site and process through which bordering is enacted (

Filipcevic Cordes 2017;

Bauder 2016), such scholarship must beware the risks of re-silencing undocumented peoples (

Varsanyi 2006). Too often the urban is approached as an abstract scale, without appropriate attention to the intimate experiences of urban residents—especially those with precarious status. In an attempt to resist such abstraction, which further invisibilises migrant lives and deaths, this paper attempts follow and make visible Lucia’s own encounters with violent urban bordering practices. Following the story of a particular migrant, Lucía, also exposes the way in which hostile bordering practices are shifting and taking on new geographies. In particular, the following sections explore how carceral geographies are moving underground. Finally, this paper seeks to understand the various forms of political solidarity that continue to challenge these violences.

5. Privatized ‘Caring’ Checkpoints

The fact that Lucía was asked to prove her citizenship to a fare inspector, hired by the security company Translink, during her daily commute indicates not only how everyday city services resemble borderzones, but how private companies become their border-guards. Vancouver’s Skytrain police budget has grown to

$31 million annually, and is expected to grow 25% over the next few years; this is suggestive of an urban bordering landscape increasingly governed through neoliberal forces (

Nail 2016).

Lucía’s encounter also reveals the racialised ways in which border enforcement is being enacted throughout the city (according to police reports, she was stopped because she had an accent). Many studies show that those stopped are disproportionality Indigenous and of colour (

Walia 2014). The targeted policing and removal of certain bodies render services (such as transit, health, education, housing) differentially accessible. This policing targets certain bodies, shrinks public space, and is a condition of possibility for ever-gentrifying processes which constitute Vancouver.

Following Lucía’s death, advocacy groups have identified health care as a particularly pernicious zone for those without full legal status. The Fraser Health Authority, with the largest catchment area operating 12 hospitals through Lower Mainland, has been specifically identified. Despite Fraser Health’s motto: “Better health. Best in health care,” health care in the region functions much more as a checkpoint which deters people rather than safe haven. Indeed, a recent (9 March 2016) Freedom of Information Act (FOI) request discovered that over a 22-month period (between 1 January 2014 and 7 October 2015) Fraser Health staff made 588 referrals to CBSA for which they were financially compensated.

Fraser Health is also compensated for its costly arrangements for air ambulance and airline medical escorts to assist with deportations. As revealed in FOI requests, Fraser Health policy dictates that physicians, nurses, and social workers should work with the financial department to arrange deportations. A spokesperson for the B.C. Ministry of Health indicated that the province does not have a policy on immigration referrals and leaves those decisions to each service provider. Policing is thus left to discretion of private companies, such as Fraser Health, who are financially biased towards collaborating with CBSA. Forthcoming research, entitled ‘Birthing at the Borders’, demonstrates how these policing activities asymmetrically bear down on women with precarious status. This study shows how many pregnant women employed as Caregivers are denied maternal care; how they actively avoid hospitals out of fear for deportation/costs and, as a result, are risking their own health as well as their babies’ chance of survival (Bagelman, forthcoming).

In this context see how the earlier fare inspector reappears in different forms within the health-care sector. Referrals and cooperation with the CBSA reveal how border checkpoints become a spatial fabric through which individuals are plotted and thereby governed. Here, municipal services become border checkpoints linked to national citizenship enforcement (

Salter 2004, pp. 81–82). Tracing Lucia’s journey uncovers a process wherein constant urban checkpoints serve to produce a surveillance effect, which channels certain bodies into out-of-sight detention.

6. Carceral Archipelago

Examining the geography and governance of the holding cell where Lucía was detained further illuminates the tragic effects of an increasingly privatized border enforcement. After being stopped in transit by Translink, Lucía was detained at the BC Immigration Holding Centre (BCIHC). At the time of writing, this is one of the four holding centres in Canada (the other three being in Kingston, Toronto, Laval).

While CBSA is in charge of the holding centre at YVR, in 2010 it contracted out its management to a private firm Genesis Security. Ignoring the coroner’s jury recommendation that CBSA use its own officers, on 7 July 2015 CBSA contracted out its duties to another private GardaWord until March 2017.

Because the “lowest bidder in a tender process by CBSA” wins, staff are often lacking training, for instance in suicide prevention (Buchanan). Guards with Vancouver-based Genesis Security testified that the company’s wages start at $15 an hour—after a $13 probationary period—and employees are expected to pay much of their own training costs. The only training related to suicide is a printed package that staff may not remove from the airport facility.

Investigations into Canada’s detention practices have raised other concerns over the conditions at facilities and the treatment of detainees. CBSA’s 2010 evaluation report, for example, revealed not only regional variations in accessing care for mental health issues but also that the CBSA often fails to track detainees’ health statistics. The CBSA’s 2010 report also highlighted staff requests for “better training on how to deal with persons with mental illness”.

That Lucía ended up in the CBSA cell reveals how migrants are not only being intercepted before and at the border but also actively detained within cities (many of whom were recruited through temporary work programs, and who constitute Vancouver’s growing precariat). This is echoed in the BCIHC’s mandate who was to “initially house only airport cases [it also] now includes detainees discovered in-land as well” (Committee Report: Parliament of Canada, 2011). This again speaks to the urban capillaries of migration management.

As removals creep deeper in-land, interceptions and detention simultaneously move outward: to more remote, even offshore locations (

Mountz 2015). The geography of BCIHC illustrates particular technologies used to isolate detainees in four inter-related ways (see

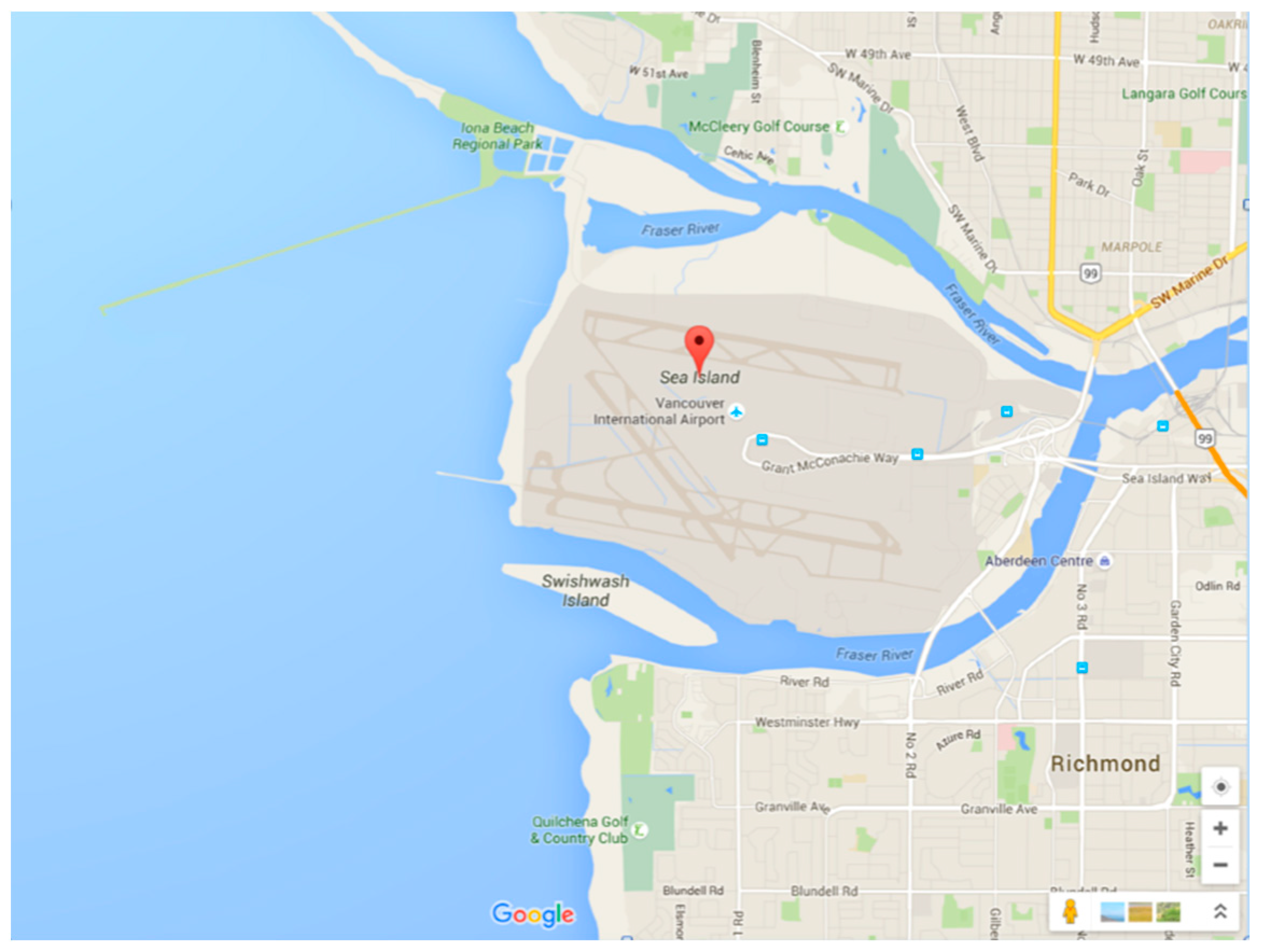

Figure 2).

First, the holding centre is geographically distanced, located on an island called “Sea Island.” Second, the site is also

underground, below the airport. Above this holding cell is a highly visible hub of transit, scripted as a site of welcome. This is certainly not the only subterranean space holding migrants in a suspended state. Day cells run by CBSA are also located below Vancouver’s public library ‘Library Square.’ This vertical dimension, we argue, is vital to Canada’s migration management. Given that this centre is both located on an island, and underground this site functions to socially and legally isolate detainees. Here there is no access to lawyers, family or community members. Finally, the fact that news of Lucía’s death reached her sister an entire month after her death speaks to not only the spatial but temporal distance that this centre produces. This centre functions as an insulated carceral space where essential services and grievability are denied. This evokes Butler’s set of critical questions “who counts as human? Whose lives count as countable lives? And finally, what makes for a grievable life? (

Butler 2003, p. 20).

These four features are hauntingly reminiscent of what Foucault referred to, and political geographers have elaborated as, the ‘carceral archipelago’ (

Foucault [1978] 1995;

Mountz 2014;

Gregory 2007). This system of surveillance and control, Foucault argues, functions partly through isolating, silencing or removing certain figures from the frame. As Derek Gregory has pointed out, this apparatus operates through processes of “silencing and disappearing” which involves the production of exceptional states and spaces through the law (2007). The proliferation of island detention sites also epitomize this form of control whereby “migrants are moved and contained farther offshore on remote islands in the enforcement archipelago” where they are both “geographically distanced and discursively othered” (

Mountz 2015).

7. Contained yet Connected

The holding cell at YVR where Lucía was detained demonstrates Vancouver’s layered carceral order: prison cells are directly below an airport duty-free shopping zone. Quartz tiles, expensive whiskeys and gaudy sports cars on display as raffle prizes conceal the violence below ones feet. This is not unique to YVR. For instance, detainees are currently held in the basement of the so-called ‘Public’ Vancouver Library. In both sites we see (or do not see) how such architectural striation enables connection (to the world/education) for some and containment for others. Here, the carceral field extends horizontally and vertically.

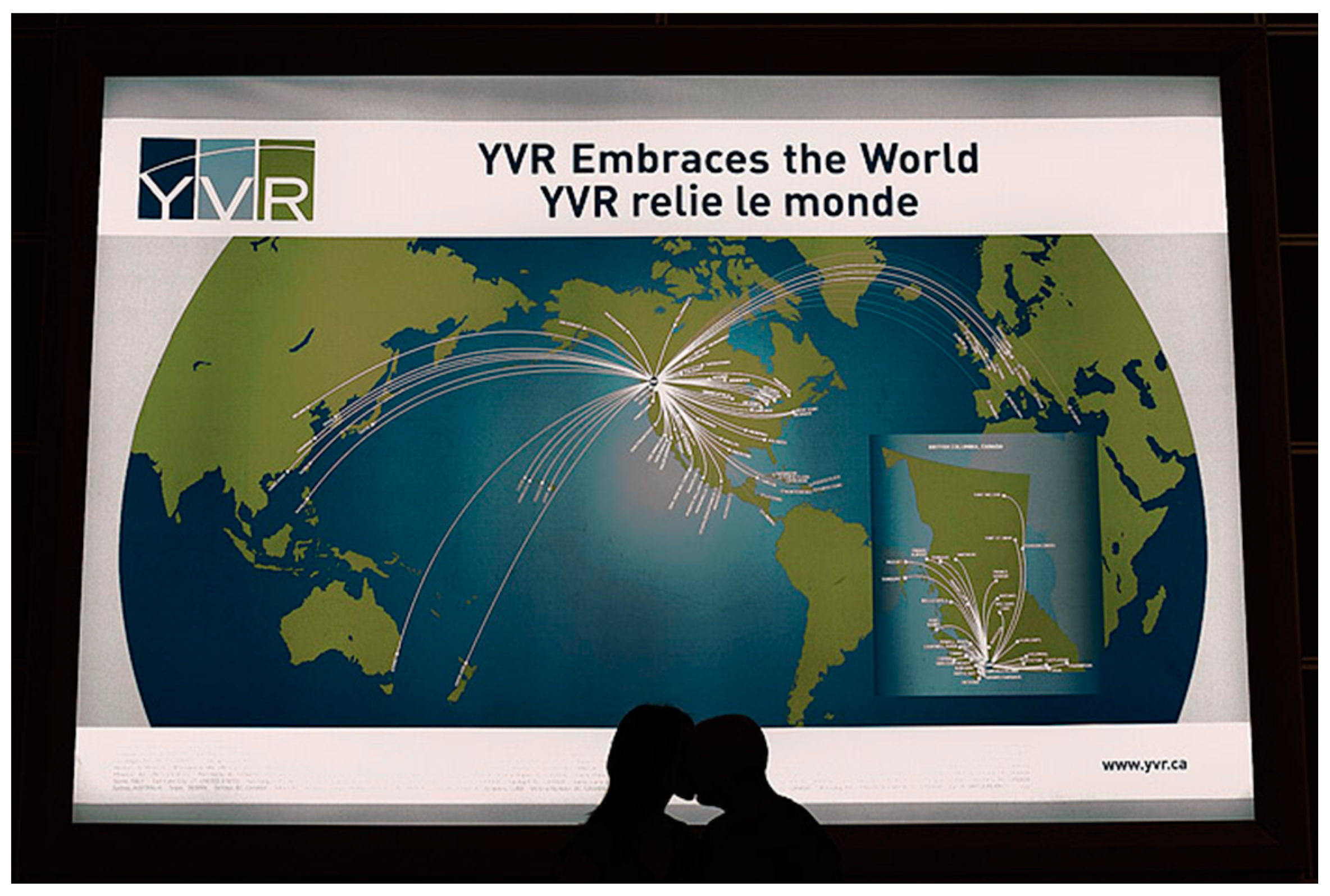

This hierarchical ordering is governed through strategic visibility. YVR, for instance, is publicly scripted as a site through which the world is connected and embraced (see

Figure 3) while those trapped in transit are out of sight. The violence imposed on Lucía’s body, what we might call the “dark side” of globalization, is concealed (

Lui 2002). Walking through YVR (by virtue of the fact of holding, for instance, a Canadian passport) one does not see the draconian face of deportation and detainment but lovey-dovey displays of airport engagement photography.

8. Sanctuary City

While hostile bordering practices take on new form, so too do the struggles. Resistance emerges,

Foucault (

1981) notes, through the challenging of governing logics and power relations (p. 254). Here, we demonstrate how the governmentalizing process of officials enacting border checkpoints through voluntary collaboration (whether within the transit system, hospitals, or schools) requires the inverse of collaboration, in the form of stubborn non-cooperation and non-compliance. In Vancouver, Lucía’s tragic story has catalyzed community to do the necessary anticolonial migrant justice work in loving, inventive, and powerful ways.

Let us return to the image of the protesters that introduces this article. This is an image of people protesting CBSA demanding an inquest into Lucía’s death—many of whom continue to build a ‘sanctuary city from below’ (

Walia 2014). Though this movement is diverse and belies simple slogans, it is guided by an overarching principle (reminiscent of Lefebvre) that all must have a ‘right to the city’—regardless of status. We now want to highlight a number of ways this search (or this insistence) for safe haven is morphing in city of Vancouver.

First, as of 23 March 2016 through grassroots mobilization on behalf of groups like No One Is Illegal, City of Vancouver councilors unanimously approved a “Access to City Services Without Fear” policy to provide “residents with Uncertain or No Immigration Status” access to services without fear that employees will share their information with public agencies that could deport them. This means that City staff will not ask for immigration status in the provision of City services nor will they pass information about immigration status to other orders of government unless required by law.

Second, the policy’s power rests in its principle of non-compliance or non-cooperation with CBSA enforcement (perhaps more robust than practices, i.e. the UK (

Bagelman 2015), where often the policy is a symbolic gesture) we can see how essential city services refuse to become border checkpoints.

Third, the organisers have taken a targeted multi-sectorial approach where health/transit/food/housing activism intersect and build solidarities between the growing number of people negatively impacted by the occupied, gentrified, carceral city. Focused campaigns such as “Transportation Not Deportation” were able to uncover a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) between transit police and the Canadian Border Services Agency—a document that transit police had previously said did not exist. The Freedom of Information Act request that revealed this document led to a cancellation of the MOU and a commitment to change policing procedures that will (hopefully) make transit a safer place for migrants.

Still, can this be considered a “safe” place? Grassroots organisers have urged the city to drop the term “sanctuary” from this policy because there exists substantial gaps. Though the policy states that city staff will not ask for immigration status, this does not prevent external groups from doing so (notably: Vancouver police department, nor transit police, park board, regional health authorities or library). The Mayor of Vancouver has agreed the term ‘sanctuary’ would be misleading. While the Mayor says the municipalities do not have the jurisdiction to control these groups neither is any commitment to push the policy with police. What we are seeing is not a politics, however, of waiting but—and this captures the fourth dimension—a generative politics of making and taking spaces (

Squire and Bagelman 2012). Alternative spaces of care, such as Pomegranate Community Midwives in Downtown East Side (DTES), are proliferating.

Finally, while creating alternative spaces this is done alongside a wider agenda that challenges border enforcement in cities. The movement is characterized by a variegated approach, responding to ‘variegated citizenship’ (

Ong 1999). This politics is grounded, imminent, resistive and generative and always nested in wider agenda that moves towards regularization.

One woman engaged in the sanctuary city, as a health-nurse, providing alternative care in a midwife clinic, describes these sanctuary politics as a ‘hustle.’ Reflecting on her work in a clinic that she describes as a place run by “radical queers with good politics,” the health-nurse states that: “providing sanctuary is sort of like jumping on those little sand bars, you know, at the beach…. You are always playing with the tides” (

Bagelman 2016).

This paper began by highlighting the proliferation of carceral islands and their capillaries: invisibilized and remote privatized detention sites that are literally buried underground, below glossy airport lobbies and ‘public’ libraries. The violent contours of these spaces, this paper has shown, are poignantly exposed when we trace aspects of Lucía’s story. Though we call for deepened attention to these hostile—especially subterranean—spaces, we do not wish to end by dwelling upon them. Instead, we conclude with the reflections offered above by a sanctuary health-nurse involved in challenging exclusionary migration practices. On the one hand, her words point to the fragility of sanctuary politics: they are always at risk of disappearing. Yet, on the other hand this reflection serves as a wider reminder: islands are contingent. Rather than approaching carceral spaces as inevitably fixed features of geopolitical landscapes, perhaps we are better advised to acknowledge their vulnerability. For tides do shift, islands fall into and out of visibility and—given the right conditions—those carceral archipelagos may indeed wash away.